Abstract

The PI 3-K/Akt pathway is responsible for key aspects of tumor progression, and is frequently hyperactivated in cancer. We have recently identified palladin, an actin-bundling protein that functions to control the actin cytoskeleton, as an Akt1-specific substrate that inhibits breast cancer cell migration. Here we have identified a role for Akt isoforms in the regulation of palladin expression. Akt2, but not Akt1, enhances palladin expression by maintaining protein stability and upregulating transcription. These data reveal that Akt signaling regulates the stability of palladin, and further supports the notion that Akt isoforms have distinct and specific roles in tumorigenesis.

Keywords: Akt isoform, palladin, protein stability, breast cancer

1. Introduction

Palladin is an actin-bundling protein and plays an important role in organization of the actin cytoskeleton [1]. It also acts as a molecular scaffold by linking actin to a number of anchor proteins including α-actinin [2], Eps8 [3], ezrin [4], profilin [5] and VASP [6]. Short hairpin RNA (shRNA) silencing and knockout mouse studies have demonstrated a critical role for palladin in stabilizing actin stress fibers [7-9]. Accordingly, palladin has been shown to enhance migration of smooth muscle cells [10] and fibroblasts [8]. On the other hand, our recent studies have shown that palladin has anti-migratory and anti-invasive functions in breast carcinoma cells [9]. Given that palladin is a key regulator in the establishment of cell morphology and motility, it is important to dissect regulatory mechanisms for palladin.

Palladin is widely expressed in both epithelial and mesenchymal cells [2,7]. Its expression is tightly regulated in various physiological settings. For example, palladin is upregulated during differentiation of myofibroblasts [11] and dendritic cells [4]. Palladin expression is also increased in response to signals induced by vascular injury and smooth muscle cell hypertrophy [10]. In addition to these physiological functions, recent studies have indicated a role for palladin in human carcinomas. Overexpression of palladin is observed in breast carcinoma tissues [12] as well as tumor-associated fibroblasts of pancreatic adenocarinomas [13]. Indeed, palladin has been proposed as a prognostic biomarker in solid tumors. However, the molecular mechanisms that regulate the expression and activity of palladin have remained elusive. Palladin is phosphorylated on tyrosine residues in cells expressing active Src, but the kinase that is responsible for the phosphorylation and the functional significance of tyrosine phosphorylation remain to be determined [14].

The expression of Akt isoforms is also frequently deregulated in breast carcinomas [15,16]. Hyperactivation of the phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI 3-K)/Akt pathway enhances tumor growth and survival, thereby making Akt an attractive target for the development of anti-cancer therapeutics [17,18]. Recent studies have demonstrated that Akt1 and Akt2 have opposing functions in breast cancer cell migration and metastasis [19-24]. There is little information, however, on the isoform-specific downstream substrates of Akt. We have recently identified palladin as an Akt1-specific substrate that inhibits breast cancer cell migration [9]. Phosphorylation of palladin at Ser507 by Akt1 promotes the formation of actin bundles and in turn reduces both random and directional migration. These studies provide a link between Akt isoform-specific signaling and cytoskeleton rearrangement. Given the diagnostic and therapeutic implications of palladin and Akt in cancer progression, the present study was undertaken to investigate if Akt isoforms differentially regulate the expression and stability of palladin in breast tumor cells. Here we show that Akt2, but not Akt1, regulates palladin expression by promoting protein stability and upregulation of mRNA levels.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Cell lines and reagents

HEK293T, HeLa, MCF7 and MDA-MB-231 cells were maintained in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM) (Cellgro; Manassas, VA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (HyClone; Waltham, MA). MCF10A were grown in DMEM/Ham's F12 medium supplemented with 5% equine serum (Gibco-brl; Carlsbad, CA), 10 μg/ml insulin (Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, MO), 500 ng/ml hydrocortisone (Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, MO), 20 ng/ml EGF (R&D systems; Minneapolis, MN) and 100 ng/ml cholera toxin (List Biological Labs; Campbell, CA). LY294002 (Alexis Biochemicals; Farmingdale, NY) and SN30978 (referred to Akti-1/2 in [25]; gift from Dr. Peter Shepherd (Symansis and University of Auckland, New Zealand)) were added to cells at final concentrations of 10 μM and 5 μM, respectively. MG132 (Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, MO) and cycloheximide (Sigma-Aldrich; St. Louis, MO) were added to cells at 10 μM and 20 μg/ml, respectively. Anti-Akt1 monoclonal antibody, anti-Akt2 polyclonal antibody and anti-phospho-Akt S473 (pAkt) monoclonal antibody were obtained from Cell Signaling Technology (Danvers, MA). Anti-Akt polyclonal antibody was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology (Santa Cruz, CA). Anti-palladin polyclonal antibody was from ProteinTech Group (Chicago, IL). Anti-ERK monoclonal antibody was from BD Transduction (Lexington, KY). Horseradish peroxidase-conjugated anti-mouse and anti-rabbit immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody were purchased from Chemicon (Billerica, MA). Anti-β-actin monoclonal antibody was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO). Anti-Akt1 polyclonal antibody was raised against a synthetic peptide (VDSERRPHFPQFSYSASGTA) and generated in house. Anti-HA monoclonal antibody was purified from the 12CA5 hybridoma.

2.2 Plasmids

HA-Palladin plasmid was a gift from Dr. Mikko Ronty [14] (University of Helsinki, Finland). HA-Palladin S507A has been described previously [9]. HA-Palladin S507D was constructed by site-directed mutagenesis with the following primers: sense, 5′-CTCATGTCAGAAGGCCTCGTTCTAGAGATAGGGACAGTGGAGAC-3′; anti-sense, 5′-GTCTCCACTGTCCCTATCTCTAGAACGAGGCCTTCTGACATGAG-3′. HA-Palladin S507E was constructed by site-directed mutagenesis with the following primers: sense, 5′-CTCATGTCAGAAGGCCTCGTTCTAGAGAGAGGGACAGTGGAGAC-3′; anti-sense, 5′-GTCTCCACTGTCCCTCTCTCTAGAACGAGGCCTTCTGACATGAG-3′. All sequences were verified by DNA sequencing.

2.3 RNA interference

Akt1 shRNA sequence 1 and Akt2 shRNA sequence 1 have been described previously [9]. Akt1 shRNA sequence 2 and Akt2 shRNA sequence 2 were cloned into the pLKO lentiviral expression system as previously described [9]. Akt1 shRNA sequence 2: sense, 5′-CCGGgctacttcctcctcaagaatgCTCGAGcattcttgaggaggaagtagcTTTTTG-3′; anti-sense, 5′ -AATTCAAAAAgctacttcctcctcaagaatgCTCGAGcattcttgaggaggaagtagc-3′. Akt2 shRNA sequence 2: sense, 5′ - CCGGcttcgactatctcaaactcctCTCGAGaggagtttgagatagtcgaagTTTTTG – 3′; anti-sense, 5′ – AATTCAAAAActtcgactatctcaaactcctCTCGAGaggagtttgagatagtcgaag-3′.

2.4 Immunoblots and quantitative real-time RT-PCR

Immunoblotting was performed as described previously [9]. Protein levels were quantified with ImageJ from NIH software. Total RNA was isolated with Trizol (Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA) according to the manufacturer's protocols. Reverse transcription was performed using random hexamers and multiscribe reverse transcriptase (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA). Quantitative real-time PCR was performed using an ABI Prism 7700 sequence detector (Foster City, CA). Palladin primers [13]: sense, 5′ – AACCGAGCAGGACAGAAC-3′; anti-sense, 5′ – TGGTGGCACTCCCAATAC-3′. PCR reactions were carried out in triplicates. Quantification of palladin expression was calculated by the dCT method with GAPDH as the reference gene.

3. Results

3.1 Akt isoforms differentially regulate the expression levels of palladin

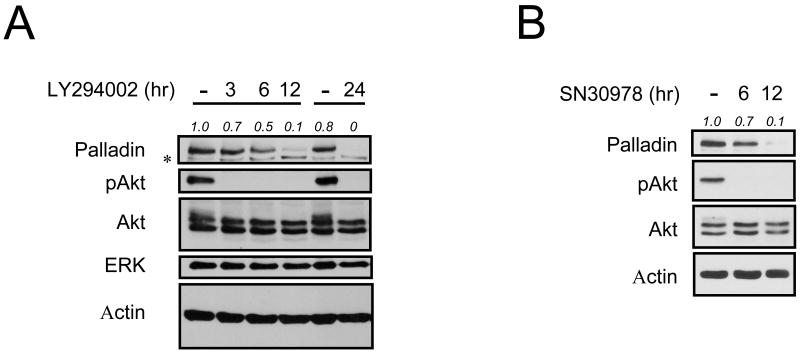

To investigate whether the Akt signaling pathway regulates palladin protein levels, HeLa cells were treated with the PI 3-K inhibitor LY294002. LY294002 efficiently inhibits phosphorylation of Akt (Fig. 1A). Notably, expression of palladin is decreased by LY294002 treatment in a time-dependent manner. On the other hand, expression of an unrelated protein ERK is not affected. Palladin expression is also reduced in cells treated with the Akt inhibitor SN30978 [25] (Fig. 1B). The specificity of the palladin antibody has been tested in different cell lines using palladin shRNA (Fig. S1 [9]). These findings indicate that Akt selectively modulates the expression levels of palladin.

Fig. 1.

Akt signaling pathway regulates palladin expression. HeLa cells were treated with LY294002 (10 μM) (A) or SN30978 (5 μM) (B) for the indicated times. Protein levels of palladin were analyzed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. Palladin expression levels were quantified and shown as a ratio compared to control. Asterisk (*) indicates a non-specific band.

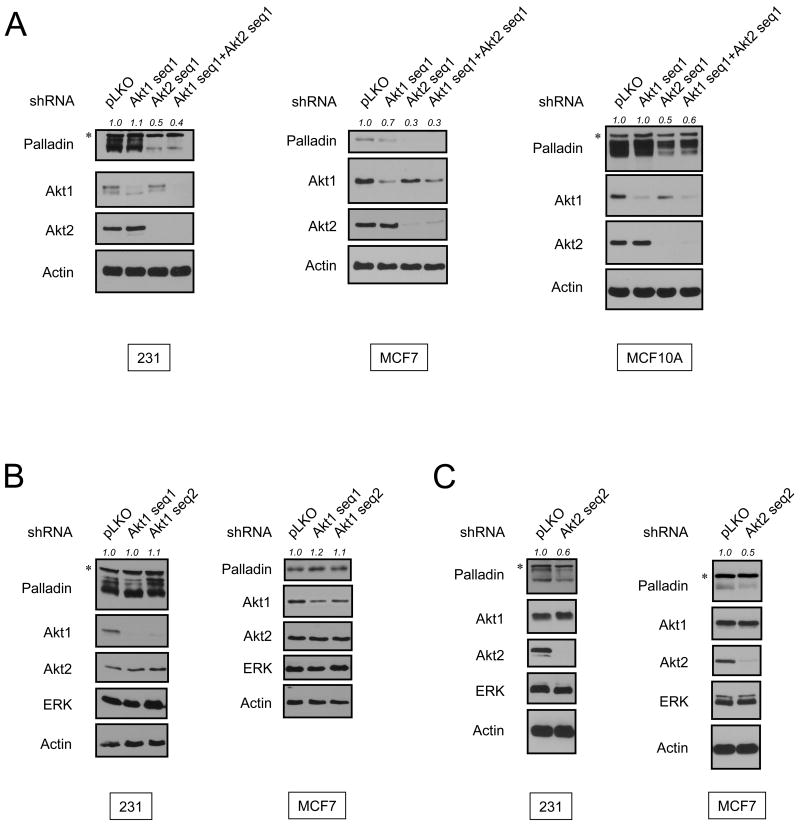

We next determined if Akt isoforms have differential roles in the regulation of palladin expression, and used shRNA targeting Akt1 or Akt2. In MDA-MB-231 and MCF7 breast cancer cell lines as well as immortalized nontumorigenic MCF10A breast epithelial cells, knockdown of Akt2 reduces palladin expression by more than 50% (Fig. 2A). Conversely, depletion of Akt1 has no effect. Knockdown of Akt isoforms by a second, unrelated shRNA yields similar results (Fig. 2B and 2C). These results demonstrate that palladin expression is regulated by Akt2, but not Akt1.

Fig. 2.

Expression levels of palladin are differentially regulated by Akt isoforms. (A) MDA-MB-231, MCF7 and MCF10A cells were infected with Akt1 shRNA sequence 1 and/or Akt2 shRNA sequence 1, or empty vector for 48 hr. Lysates were subjected to immunoblot analysis. (B) MDA-MB-231 and MCF7 cells were infected with Akt1 shRNA sequence 1 or sequence 2, or empty vector for 72 h. Cell extracts were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (C) MDA-MB-231 and MCF7 cells were infected with Akt2 shRNA sequence 2 or empty vector for 72 h. Protein levels of palladin were detected as described in (B). Palladin expression levels were quantified and shown as a ratio compared to control. Asterisk (*) indicates a non-specific band. The multiple bands of palladin are fully consistent with different posttranslational modification patterns of palladin, as observed previously [3].

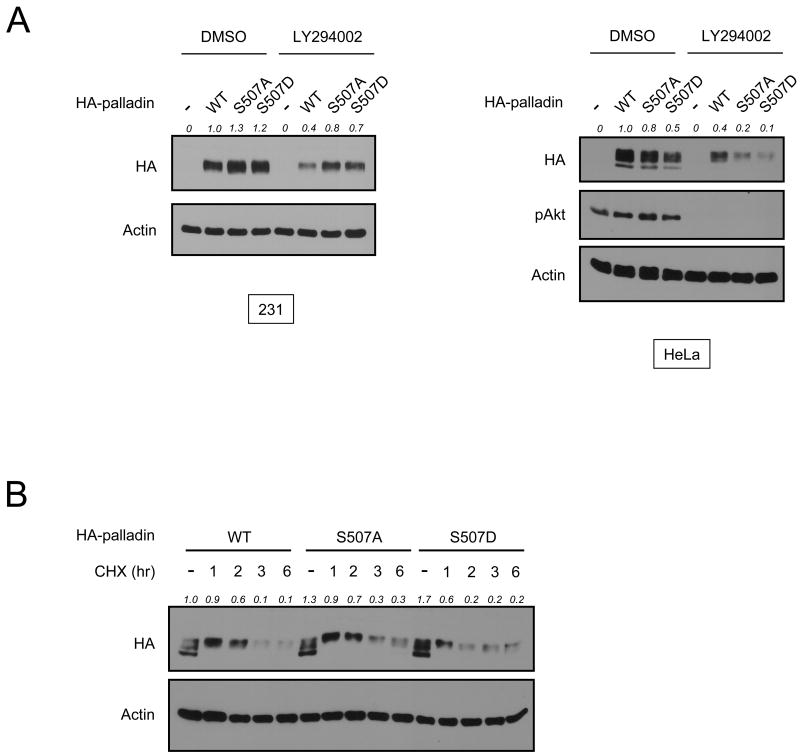

3.2 Palladin expression is not regulated by phosphorylation at Ser507

We have recently shown that palladin is an Akt1-specific substrate [9]. Since the expression levels of palladin are not affected by Akt1, we hypothesized that phosphorylation of palladin at Ser507 does not play a role in its expression or stability. To test this, MDA-MB-231 and HeLa cells were transfected with wild-type (WT) palladin, a non-phosphorylatable Ser507Ala mutant, or a phosphomimetic Ser507Asp mutant, followed by LY294002 treatment. As predicted, LY294002 attenuates the expression of WT and mutant palladin alleles to a similar extent (Fig. 3A). In addition to the Ser507Asp mutant, a Ser507Glu phosphomimetic mutant of palladin was also generated. The effect of LY294002 on the Ser507Glu allele is very similar to that of WT palladin (data not shown), indicating that palladin expression is not modulated by its phosphorylation status. To further investigate the role of palladin phosphorylation in protein stability, de novo protein synthesis was inhibited by treating cells with cycloheximide. The degradation rates of WT palladin and the mutants are similar (Fig. 3B), again indicating that palladin phosphorylation at Ser507 does not regulate stability. These data are in agreement with the model that Akt isoforms differentially regulate the function and expression of palladin: Akt1 modulates the activity of palladin by phosphorylating it at Ser507, whereas Akt2 regulates palladin protein expression and stability.

Fig. 3.

Phosphorylation of palladin at Ser507 does not regulate its expression levels. (A) MDA-MB-231 and HeLa cells were transfected with wild-type (WT) HA-palladin, HA-palladin Ser507Ala (S507A), HA-palladin Ser507Asp (S507D) or control vector for 24 hr. Cells were then treated with LY294002 (10 μM) or DMSO for 24 hr before harvesting and immunoblotting. (B) HeLa cells transfected with HA-palladin WT, S507A or S507D mutants were treated with cycloheximide (CHX; 20 μg/ml) for the indicated times. Protein levels of palladin were analyzed by immunoblotting with anti-HA antibody. Palladin expression levels were quantified and shown as a ratio compared to control.

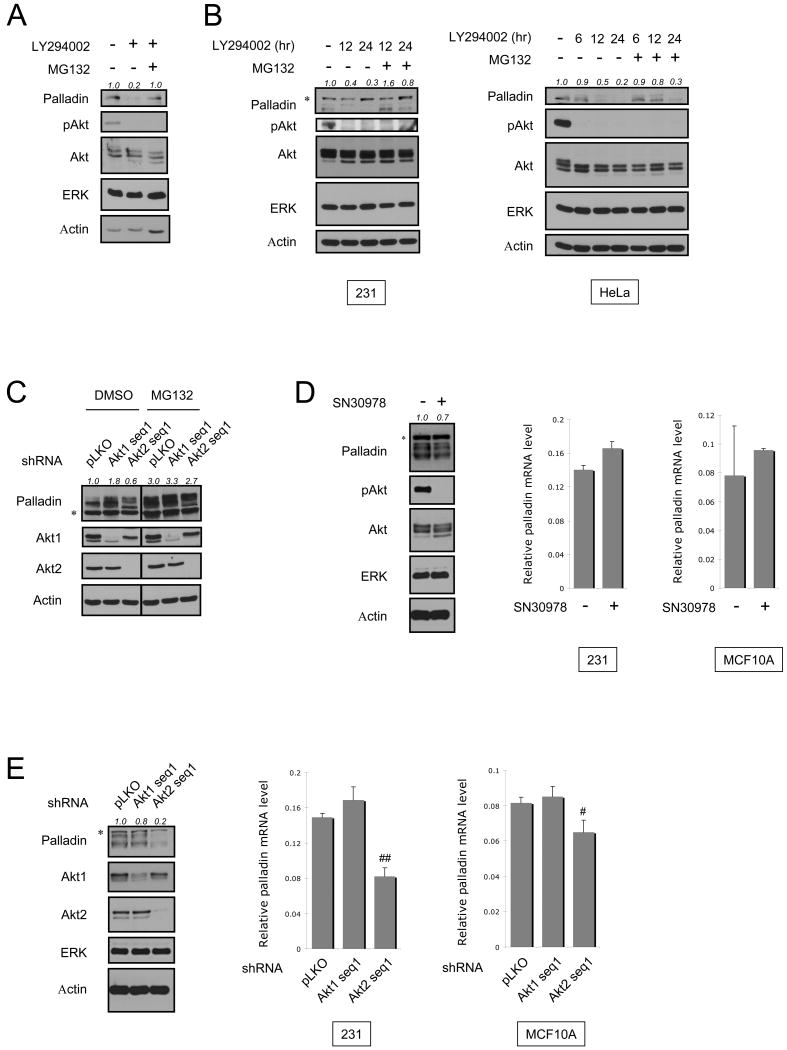

3.3 Akt2 promotes the stability of palladin and enhances its mRNA expression

Akt2 could modulate palladin levels by regulating its synthesis and/or degradation. To test these possibilities, we first determined if Akt signaling stabilizes palladin protein, by treating cells with the proteasome inhibitor MG132. As shown in Fig. 4A, MG132 efficiently protects palladin from LY294002-induced degradation. We then performed a time-course assay, in which MDA-MB-231 and HeLa cells were incubated with LY294002 for various times, followed by treatment with MG132. At all time points examined, stabilization of palladin was observed in the presence of MG132 (Fig. 4B). Using an shRNA approach, our results show that in DMSO-treated cells, palladin expression levels are decreased by 40% in the presence of Akt2 shRNA (pLKO: 1.0; Akt2 shRNA: 0.6) (Fig. 4C). In contrast, in MG132-treated cells, Akt2 knockdown only decreases palladin expression levels by 10% (pLKO: 3.0; Akt2 shRNA: 2.7). These data demonstrate that the reduction of palladin expression in Akt2 shRNA-expressing cells is at least partially reversed by MG132 treatment. Real-time RT-PCR analysis shows that whereas treatment of cells with Akt inhibitor SN30978 reduces palladin protein levels, there is no detectable effect on mRNA levels (Fig. 4D). Thus, Akt2 regulates palladin expression, at least in part, by promoting its stability. Interestingly, when cells are depleted with Akt2 for more than 24 hr, both the protein and mRNA levels of palladin are significantly reduced (Fig. 4E). Taken together, these results suggest that Akt2 regulates palladin expression by maintaining protein stability as well as enhancing transcription.

Fig. 4.

Akt2 regulates the stability as well as mRNA expression levels of palladin. (A) HeLa cells were treated with LY294002 (10 μM) or DMSO for 12 hr. Six hours before harvesting, cells were treated with MG132 (10μM) or DMSO. Lysates were subjected to immunoblotting. (B) MDA-MB-231 and HeLa cells were treated with LY294002 (10 μM) or DMSO for the indicated times. MG132 (10μM) or DMSO was added to cells for 6 hr before harvesting. Levels of palladin expression were analyzed by immunoblotting. (C) HeLa cells transfected with HA-palladin were infected with Akt1 shRNA sequence 1 or Akt2 shRNA sequence 1, or empty vector for 72 hr. Sixteen hours before harvesting, cells were treated with MG132 (10μM) or DMSO. Lysates were immunoblotted. (D) MDA-MB-231 and MCF10A cells were treated with SN30978 (5 μM) or DMSO for 12 hr. mRNA levels of palladin were analyzed by quantitative real-time RT-PCR. The levels of palladin mRNA are expressed as a ratio relative to the GAPDH mRNA in each sample. Protein expressions were analyzed by immunoblotting. (E) MDA-MB-231 and MCF10A cells were infected with Akt1 shRNA sequence 1, Akt2 shRNA sequence 1, or empty vector for 48 hr. mRNA and protein levels of palladin were analyzed as described in (D). Palladin expression levels were quantified and shown as a ratio compared to control. Asterisk (*) indicates a non-specific band. # and ## indicate a P-value of <0.05 and <0.01, respectively.

4. Discussion

Although the key role of Akt in tumor initiation and progression is well established, isoform-specific signaling of Akt has remained less well studied. The present study shows that expression of palladin in breast cancer cells is regulated by an Akt2, but not Akt1, pathway. We further show that Akt2 enhances palladin expression by maintaining its stability as well as upregulating mRNA expression. Since phosphorylation of proteins is commonly involved in the modulation of protein stability [26], we tested if Akt1-mediated phosphorylation of palladin regulates its stability. Our finding that neither the phosphomimetic nor non-phosphorylatable mutants of palladin have altered degradation rates compared to the wild-type protein indicates that phosphorylation of palladin does not play a role in its stability. Together with our previous observations, our results suggest that the activity and expression of palladin are regulated by distinct Akt isoforms; whereas Akt1 plays a critical role in the inhibition of breast cancer cell migration by phosphorylating palladin, Akt2 upregulates the expression of palladin.

The mechanism by which Akt2 enhances the mRNA expression of palladin is not known at the present time. Akt has been shown to directly phosphorylate transcription factors such as FOXO, as well as proteins that play critical roles in the transcription process such as glycogen synthase kinase-3β [26]. However, to date none of these have been demonstrated to be isoform-specific. MDM2, an E3 ubiquitin-protein ligase which mediates degradation of the transcription factor p53, is phosphorylated specifically by Akt2 [27]. It will be interesting to examine if this Akt2 substrate plays a role in palladin transcription. Our results which reveal that Akt2 promotes palladin stability are somewhat surprising, since our previous studies showed that palladin associates with Akt1, but not Akt2 [9]. It is possible that the interaction between palladin and Akt2 is too weak to be detected in our experimental system. Alternatively, Akt2 may modulate a downstream protein, which in turn protects palladin from degradation.

It is known that in human carcinoma cells, both the stimulatory and inhibitory proteins of the actin cytoskeleton are coordinately upregulated [28]. Indeed, increased expression of palladin is observed in human breast tumor samples [12] and rat invasive mammary carcinoma cells [28]. Given its molecular scaffolding role, overexpression of palladin may cause an imbalance of its interacting proteins that remodel the cellular architecture. Alternatively, nuclear expression of palladin is observed in multiple cell types [13,29], rising the possibility that palladin has a function in the regulation of gene expression. The clinical relevance of palladin and Akt deregulation in carcinoma cells is highlighted by the fact that increased Akt1 expression is found in both estrogen receptor (ER)-positive and ER-negative breast tumors. In contrast, overexpression of Akt2 is more frequently observed in ER-negative breast tumors [30]. Whether there is a correlation between Akt2, palladin and ER expression in breast cancer patients remains to be determined. Currently, seven palladin isoforms, which arise from alternative start sites or splicing, have been identified in humans [13]. Our study focuses on the regulation of the most widely-expressed isoform (90 kDa) of palladin by the Akt pathway. Our results also indicate that Akt2 regulates the expression of another major isoform (140 kDa) of palladin (data not shown). It would be interesting to test if Akt signaling modulates the expression levels of other palladin isoforms.

Taken together, we present evidence on a signaling pathway that regulates the stability of palladin. This study further highlights the importance of Akt isoform-specific signaling in breast cancer, which is predicted to have important ramifications for the development of anti-cancer drugs targeting the Akt pathway.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Mikko Ronty, Peter Shepherd and Symansis for providing reagents, and members of the Toker laboratory for discussions. This study was supported in part by grants from the National Institutes of Health (A.T., CA122099; Y. R. C., T32 CA081156-09), Italian CNR short-term mobility 2009 (A.T.) and the Susan G. Komen Breast Cancer Foundation (Y.R.C., PDF0706963).

Abbreviations

- shRNA

short hairpin RNA

- PI 3-K

phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase

- DMEM

Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium

- FBS

fetal bovine serum

- WT

wild-type

- ER

estrogen-receptor

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Dixon RD, Arneman DK, Rachlin AS, Sundaresan NR, Costello MJ, Campbell SL, Otey CA. Palladin is an actin cross-linking protein that uses immunoglobulin-like domains to bind filamentous actin. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:6222–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M707694200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ronty M, Taivainen A, Moza M, Otey CA, Carpen O. Molecular analysis of the interaction between palladin and alpha-actinin. FEBS Lett. 2004;566:30–4. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Goicoechea S, Arneman D, Disanza A, Garcia-Mata R, Scita G, Otey CA. Palladin binds to Eps8 and enhances the formation of dorsal ruffles and podosomes in vascular smooth muscle cells. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:3316–24. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mykkanen OM, Gronholm M, Ronty M, Lalowski M, Salmikangas P, Suila H, Carpen O. Characterization of human palladin, a microfilament-associated protein. Mol Biol Cell. 2001;12:3060–73. doi: 10.1091/mbc.12.10.3060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Boukhelifa M, et al. The proline-rich protein palladin is a binding partner for profilin. Febs J. 2006;273:26–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2005.05036.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Boukhelifa M, Parast MM, Bear JE, Gertler FB, Otey CA. Palladin is a novel binding partner for Ena/VASP family members. Cell Motil Cytoskeleton. 2004;58:17–29. doi: 10.1002/cm.10173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Parast MM, Otey CA. Characterization of palladin, a novel protein localized to stress fibers and cell adhesions. J Cell Biol. 2000;150:643–56. doi: 10.1083/jcb.150.3.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luo H, et al. Disruption of palladin results in neural tube closure defects in mice. Mol Cell Neurosci. 2005;29:507–15. doi: 10.1016/j.mcn.2004.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chin YR, Toker A. The actin-bundling protein palladin is an Akt1-specific substrate that regulates breast cancer cell migration. Mol Cell. 2010;38:333–44. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.02.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jin L, Kern MJ, Otey CA, Wamhoff BR, Somlyo AV. Angiotensin II, focal adhesion kinase, and PRX1 enhance smooth muscle expression of lipoma preferred partner and its newly identified binding partner palladin to promote cell migration. Circ Res. 2007;100:817–25. doi: 10.1161/01.RES.0000261351.54147.de. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ronty MJ, Leivonen SK, Hinz B, Rachlin A, Otey CA, Kahari VM, Carpen OM. Isoform-specific regulation of the actin-organizing protein palladin during TGF-beta1-induced myofibroblast differentiation. J Invest Dermatol. 2006;126:2387–96. doi: 10.1038/sj.jid.5700427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Goicoechea SM, Bednarski B, Garcia-Mata R, Prentice-Dunn H, Kim HJ, Otey CA. Palladin contributes to invasive motility in human breast cancer cells. Oncogene. 2009;28:587–98. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Goicoechea SM, et al. Isoform-specific upregulation of palladin in human and murine pancreas tumors. PLoS One. 2010;5:e10347. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ronty M, Taivainen A, Heiska L, Otey C, Ehler E, Song WK, Carpen O. Palladin interacts with SH3 domains of SPIN90 and Src and is required for Src-induced cytoskeletal remodeling. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:2575–85. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.04.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Altomare DA, Testa JR. Perturbations of the AKT signaling pathway in human cancer. Oncogene. 2005;24:7455–7464. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1209085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Engelman JA, Luo J, Cantley LC. The evolution of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases as regulators of growth and metabolism. Nat Rev Genet. 2006;7:606–619. doi: 10.1038/nrg1879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Woodgett JR. Recent advances in the protein kinase B signaling pathway. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 2005;17:150–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chin YR, Toker A. Function of Akt/PKB signaling to cell motility, invasion and the tumor stroma in cancer. Cell Signal. 2009;21:470–6. doi: 10.1016/j.cellsig.2008.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Irie HY, Pearline RV, Grueneberg D, Hsia M, Ravichandran P, Kothari N, Natesan S, Brugge JS. Distinct roles of Akt1 and Akt2 in regulating cell migration and epithelial-mesenchymal transition. J Cell Biol. 2005;171:1023–34. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200505087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yoeli-Lerner M, Yiu GK, Rabinovitz I, Erhardt P, Jauliac S, Toker A. Akt blocks breast cancer cell motility and invasion through the transcription factor NFAT. Mol Cell. 2005;20:539–50. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.10.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu H, Radisky DC, Nelson CM, Zhang H, Fata JE, Roth RA, Bissell MJ. Mechanism of Akt1 inhibition of breast cancer cell invasion reveals a protumorigenic role for TSC2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:4134–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0511342103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hutchinson JN, Jin J, Cardiff RD, Woodgett JR, Muller WJ. Activation of Akt-1 (PKB-alpha) can accelerate ErbB-2-mediated mammary tumorigenesis but suppresses tumor invasion. Cancer Res. 2004;64:3171–8. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-3465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Maroulakou IG, Oemler W, Naber SP, Tsichlis PN. Akt1 ablation inhibits, whereas Akt2 ablation accelerates, the development of mammary adenocarcinomas in mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV)-ErbB2/neu and MMTV-polyoma middle T transgenic mice. Cancer Res. 2007;67:167–177. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arboleda MJ, et al. Overexpression of AKT2/protein kinase Bbeta leads to up-regulation of beta1 integrins, increased invasion, and metastasis of human breast and ovarian cancer cells. Cancer Res. 2003;63:196–206. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Defeo-Jones D, et al. Tumor cell sensitization to apoptotic stimuli by selective inhibition of specific Akt/PKB family members. Mol Cancer Ther. 2005;4:271–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Manning BD, Cantley LC. AKT/PKB signaling: navigating downstream. Cell. 2007;129:1261–74. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2007.06.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brognard J, Sierecki E, Gao T, Newton AC. PHLPP and a second isoform, PHLPP2, differentially attenuate the amplitude of Akt signaling by regulating distinct Akt isoforms. Mol Cell. 2007;25:917–31. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.02.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang W, et al. Identification and testing of a gene expression signature of invasive carcinoma cells within primary mammary tumors. Cancer Res. 2004;64:8585–94. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Endlich N, et al. Palladin is a dynamic actin-associated protein in podocytes. Kidney Int. 2009;75:214–26. doi: 10.1038/ki.2008.486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Stal O, Perez-Tenorio G, Akerberg L, Olsson B, Nordenskjold B, Skoog L, Rutqvist LE. Akt kinases in breast cancer and the results of adjuvant therapy. Breast Cancer Res. 2003;5:R37–44. doi: 10.1186/bcr569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.