Abstract

To be the fittest is central to proliferation in evolutionary games. Individuals

thus adopt the strategies of better performing players in the hope of successful

reproduction. In structured populations the array of those that are eligible to

act as strategy sources is bounded to the immediate neighbors of each

individual. But which one of these strategy sources should potentially be

copied? Previous research dealt with this question either by selecting the

fittest or by selecting one player uniformly at random. Here we introduce a

parameter  that interpolates between these two extreme options.

Setting

that interpolates between these two extreme options.

Setting  equal to zero returns the random selection of the

opponent, while positive

equal to zero returns the random selection of the

opponent, while positive  favor the fitter

players. In addition, we divide the population into two groups. Players from

group

favor the fitter

players. In addition, we divide the population into two groups. Players from

group  select their opponents as dictated by the parameter

select their opponents as dictated by the parameter

, while players from group

, while players from group

do so randomly irrespective of

do so randomly irrespective of

. We denote the fraction of players contained in groups

. We denote the fraction of players contained in groups

and

and  by

by

and

and  , respectively. The

two parameters

, respectively. The

two parameters  and

and

allow us to analyze in detail how aspirations in the

context of the prisoner's dilemma game influence the evolution of

cooperation. We find that for sufficiently positive values of

allow us to analyze in detail how aspirations in the

context of the prisoner's dilemma game influence the evolution of

cooperation. We find that for sufficiently positive values of

there exist a robust intermediate

there exist a robust intermediate

for which cooperation thrives best. The robustness of

this observation is tested against different levels of uncertainty in the

strategy adoption process

for which cooperation thrives best. The robustness of

this observation is tested against different levels of uncertainty in the

strategy adoption process  and for different

interaction networks. We also provide complete phase diagrams depicting the

dependence of the impact of

and for different

interaction networks. We also provide complete phase diagrams depicting the

dependence of the impact of  and

and

for different values of

for different values of  , and contrast the

validity of our conclusions by means of an alternative model where individual

aspiration levels are subject to evolution as well. Our study indicates that

heterogeneity in aspirations may be key for the sustainability of cooperation in

structured populations.

, and contrast the

validity of our conclusions by means of an alternative model where individual

aspiration levels are subject to evolution as well. Our study indicates that

heterogeneity in aspirations may be key for the sustainability of cooperation in

structured populations.

Introduction

Understanding the evolution of cooperation among selfish individuals in human and animal societies remains a grand challenge across disciplines. Evolutionary games are employed frequently as the theoretical framework of choice in order to interpret the emergence and survival of cooperative behavior [1]–[6]. The prisoner's dilemma game, in particular, has attracted considerable interest [7]–[11] as the essential yet minimalist example of a social dilemma. In the original two-person one-shot game the two players have two strategies to choose from (cooperation and defection), and their payoffs depend on the simultaneous decision of both. If they choose to cooperate they will receive the highest collective payoff, which will be shared equally among them. Mutual defection, on the other hand, yields the lowest collective payoff. Yet to defect is tempting because it yields a higher individual payoff regardless of the opponent's decision. It is thus frequently so that both players choose not to cooperate, thus procreating the inevitable social dilemma. In reality, however, interactions may be repeated and the reputation of players compromised [12], [13]. Additionally, individuals may alter with whom they interact [14], and different behaviors may be expressed when participants in a social interaction occupy different roles [15]–[18]. Such and similar considerations have been very successful in elucidating why the unadorned scenario of total defection is often at odds with reality [19], where it is clear that both humans and animals cooperate to achieve what would be impossible by means of isolated efforts. Mechanisms supporting cooperation identified thus far include kin selection [20] as well as many others [6], [21]–[23], and there is progress in place aimed at unifying some of these approaches [24], [25].

Probably the most vibrant of all in recent years have been advances building on the

seminal paper by Nowak and May [26], who showed that spatial structure may sustain

cooperation without the aid of additional mechanisms or strategic complexity.

Although in part anticipated by Hamilton's comments on viscous populations

[20], it was

fascinating to discover that structured populations, including complex and social

networks [27]–[29], provide an optimal

playground for the pursuit of cooperation. Notably, a simple rule for the evolution

of cooperation on graphs and social networks is that natural selection favors

cooperation if  , where

, where  is the benefit of the

altruistic act,

is the benefit of the

altruistic act,  is its cost, while

is its cost, while  is the average number

of neighbors [30]. This is similar to Hamilton's rule stating that

is the average number

of neighbors [30]. This is similar to Hamilton's rule stating that

should be larger than the coefficient of genetic relatedness

between individuals [20]. In fact, on graphs and social networks the evolution of

altruism can thus be fully explained by the inclusive fitness theory since the

population is structured such that interactions are between genetic relatives on

average [25],

[31], [32].

should be larger than the coefficient of genetic relatedness

between individuals [20]. In fact, on graphs and social networks the evolution of

altruism can thus be fully explained by the inclusive fitness theory since the

population is structured such that interactions are between genetic relatives on

average [25],

[31], [32].

According to the “best takes all” rule [33], [34] players are allowed to adopt the

strategy of one of their neighbors, provided its payoff is higher than that from the

other neighbors as well as from the player aspiring to improve by changing its

strategy. Based on this relatively simple setup, it was shown that on a square

lattice cooperators form compact clusters and so protect themselves against being

exploited by defectors. The “best takes all” strategy adoption rule is,

however, just one of the many possible alternatives that were considered in the

past. Other examples include the birth-death and imitation rule [35], the

proportional imitation rule [36], the reinforcement learning adoption rule [37], or the

Fermi-function based strategy adoption rule [38]. The latter received substantial

attention, particularly in the physics community, for its compatibility with the

Monte Carlo simulation procedure and the straightforward adjustment of the level of

uncertainty governing the strategy adoptions  . However, with this

rule the potential donor of the new strategy is selected uniformly at random from

all the neighbors. This is somewhat untrue to what can be observed in reality, where

in fact individuals typically aspire to their most successful neighbors rather than

just somebody random. In this sense the “best takes all” rule seems more

appropriate, although it fails to account for errors in judgment, uncertainty,

external factors, and other disturbances that may vitally affect how we evaluate and

see our co-players. Here we therefore propose a simple tunable function that

interpolates between the “best takes all” and the random selection of a

neighbor in a smooth fashion by means of a single parameter

. However, with this

rule the potential donor of the new strategy is selected uniformly at random from

all the neighbors. This is somewhat untrue to what can be observed in reality, where

in fact individuals typically aspire to their most successful neighbors rather than

just somebody random. In this sense the “best takes all” rule seems more

appropriate, although it fails to account for errors in judgment, uncertainty,

external factors, and other disturbances that may vitally affect how we evaluate and

see our co-players. Here we therefore propose a simple tunable function that

interpolates between the “best takes all” and the random selection of a

neighbor in a smooth fashion by means of a single parameter

. In this sense the parameter

. In this sense the parameter  acts as an aspiration

parameter, determining to what degree neighbors with a higher payoff will be

considered more likely as potential strategy sources than other (randomly selected)

neighbors.

acts as an aspiration

parameter, determining to what degree neighbors with a higher payoff will be

considered more likely as potential strategy sources than other (randomly selected)

neighbors.

Aiming to further disentangle the role of aspirations, we also consider two types of

players, denoted by type  and

and

, respectively. While players of type

, respectively. While players of type

conform to the aspirations imposed by the value of the

aspiration parameter

conform to the aspirations imposed by the value of the

aspiration parameter  , type

, type

players choose whom to potentially copy uniformly at random

irrespective of

players choose whom to potentially copy uniformly at random

irrespective of  . We denote the fraction of type

. We denote the fraction of type

and

and  players by

players by

and

and  , respectively. This

additional division of players into two groups is motivated by the overwhelming

evidence indicating that heterogeneity, almost irrespective of its origin, promotes

cooperative actions. Most notably associated with this statement are complex

networks, including small-world networks [39]–[41], random regular graphs [5], [42], scale-free

networks [43]–[48], as well as adaptive and growing networks [49]–[56]. Furthermore, we

follow the work by McNamara et al. on the coevolution of choosiness

and cooperation [57], in particular by omitting the separation of the

population on two types of players and introducing the heterogeneity by means of

normally distributed individual aspiration levels that are then also subject to

evolution.

, respectively. This

additional division of players into two groups is motivated by the overwhelming

evidence indicating that heterogeneity, almost irrespective of its origin, promotes

cooperative actions. Most notably associated with this statement are complex

networks, including small-world networks [39]–[41], random regular graphs [5], [42], scale-free

networks [43]–[48], as well as adaptive and growing networks [49]–[56]. Furthermore, we

follow the work by McNamara et al. on the coevolution of choosiness

and cooperation [57], in particular by omitting the separation of the

population on two types of players and introducing the heterogeneity by means of

normally distributed individual aspiration levels that are then also subject to

evolution.

At present, we thus investigate how aspirations on an individual level affect the

evolution of cooperation. Having something to aspire to is crucial for progress and

betterment. But how high should we set our goals? Should our role models be only

overachievers and sports heroes, or is it perhaps better to aspire to achieving

somewhat more modest goals? Here we address these questions in the context of the

evolutionary prisoner's dilemma game and determine just how strong and how

widespread aspirations should be for cooperation to thrive best. As we will show, a

strong drive to excellence in the majority of the population may in fact act

detrimental on the evolution of cooperation, while on the other hand, properly

spread and heterogeneous aspirations may be just the key to fully eliminating the

defectors. We will show that this holds irrespective of the structure of the

underlying interaction network, as well as irrespective of the level of uncertainty

by strategy adoptions  . In addition, the

presented results will be contrasted with the output of a simple coevolutionary

model, where individual aspirations will also be subject to evolution by means of

natural selection. We will conclude that appropriately tuned aspirations may be seen

as a universally applicable promoter of cooperation, which will hopefully inspire

new studies along this line of research.

. In addition, the

presented results will be contrasted with the output of a simple coevolutionary

model, where individual aspirations will also be subject to evolution by means of

natural selection. We will conclude that appropriately tuned aspirations may be seen

as a universally applicable promoter of cooperation, which will hopefully inspire

new studies along this line of research.

Results

Depending on the interaction network, the strategy adoption rule and other simulation

details (see e.g.

[4], [6], [23], [58]), there always

exists a critical cost-to-benefit ratio  at which cooperators

in the prisoner's dilemma die out. This is directly related to Hamilton's

rule stating that natural selection favors cooperation if

at which cooperators

in the prisoner's dilemma die out. This is directly related to Hamilton's

rule stating that natural selection favors cooperation if

is larger than the coefficient of genetic relatedness

between individuals [20]. If the aspiration parameter

is larger than the coefficient of genetic relatedness

between individuals [20]. If the aspiration parameter

(note that then the division of players to those of type

(note that then the division of players to those of type

and those of type

and those of type  is irrelevant),

is irrelevant),

, and the interaction network is a square lattice, then, in

our case,

, and the interaction network is a square lattice, then, in

our case,  . In what follows, we will typically set

. In what follows, we will typically set

slightly below this threshold to

slightly below this threshold to

and examine how different values of

and examine how different values of

,

,  ,

,

, as well as different interaction networks influence the

outcome of the prisoner's dilemma game.

, as well as different interaction networks influence the

outcome of the prisoner's dilemma game.

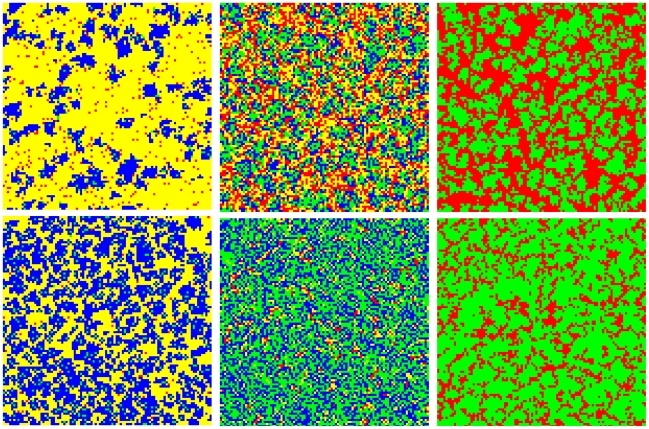

It is instructive to first examine characteristic snapshots of the square lattice for

different values of  and

and

. Results presented in Fig. 1 hint to the conclusion that heterogenous

aspiration to the fittest promotes cooperation, although the details of this claim

depend somewhat on the value of the aspiration parameter

. Results presented in Fig. 1 hint to the conclusion that heterogenous

aspiration to the fittest promotes cooperation, although the details of this claim

depend somewhat on the value of the aspiration parameter

. For small values of

. For small values of  it is best if all the

players, i.e.

it is best if all the

players, i.e.

, aspire to their slightly (note that

, aspire to their slightly (note that

is small) fitter neighbors and thus none actually choose the

potential strategy sources uniformly at random. This can be deduced from the top

three panels of Fig. 1 if

compared from left to right. For large

is small) fitter neighbors and thus none actually choose the

potential strategy sources uniformly at random. This can be deduced from the top

three panels of Fig. 1 if

compared from left to right. For large  , however, it is best

if only half of the players, i.e.

, however, it is best

if only half of the players, i.e.

, aspire to their most fittest neighbors, while the other

half chooses their role models randomly. This can be observed if one compares the

bottom three panels of Fig. 1

with one another, although the difference in the overall density of cooperators

(depicted green and blue) between the middle and the right panel is fairly small.

Finally, the role of the aspiration parameter is more clear cut since larger

, aspire to their most fittest neighbors, while the other

half chooses their role models randomly. This can be observed if one compares the

bottom three panels of Fig. 1

with one another, although the difference in the overall density of cooperators

(depicted green and blue) between the middle and the right panel is fairly small.

Finally, the role of the aspiration parameter is more clear cut since larger

clearly favor the cooperative strategy if compared to small

clearly favor the cooperative strategy if compared to small

. This can be observed if comparing the snapshots presented

in Fig. 1 vertically.

. This can be observed if comparing the snapshots presented

in Fig. 1 vertically.

Figure 1. Characteristic snapshots of strategy distributions on the square lattice.

Top row depicts results for the aspiration parameter

while the bottom row features results for

while the bottom row features results for

. In both rows the fraction of type

. In both rows the fraction of type

players

players  is

is

,

,  and

and

from left to right. Cooperators of type

from left to right. Cooperators of type

and

and  are colored

green and blue, respectively. Defectors of type

are colored

green and blue, respectively. Defectors of type

and

and  , on the other

hand, are colored red and yellow. If comparing the snapshots vertically, it

can be observed that larger values of

, on the other

hand, are colored red and yellow. If comparing the snapshots vertically, it

can be observed that larger values of  (top

(top

, bottom

, bottom  ) clearly

promote the evolution of cooperation. The scenario from left to right via

increasing the fraction of type

) clearly

promote the evolution of cooperation. The scenario from left to right via

increasing the fraction of type  players is not

so clear cut. For

players is not

so clear cut. For  (top row) we

can conclude that larger

(top row) we

can conclude that larger  favor

cooperative behavior, as clearly the cooperators flourish more and more from

the left toward the right panel. For

favor

cooperative behavior, as clearly the cooperators flourish more and more from

the left toward the right panel. For  (bottom row),

however, it seems that for

(bottom row),

however, it seems that for  (bottom

middle) cooperators actually fare better then for both

(bottom

middle) cooperators actually fare better then for both

(bottom left) and

(bottom left) and  (bottom

right). Hence, the conclusion imposes that for higher

(bottom

right). Hence, the conclusion imposes that for higher

values an intermediate (rather than the maximal, as

is the case for lower

values an intermediate (rather than the maximal, as

is the case for lower  ) fraction of

type

) fraction of

type  players (those that aspire to their most fittest

neighbors only) is optimal for the evolution of cooperation. Results in all

panels were obtained for

players (those that aspire to their most fittest

neighbors only) is optimal for the evolution of cooperation. Results in all

panels were obtained for  and

and

.

.

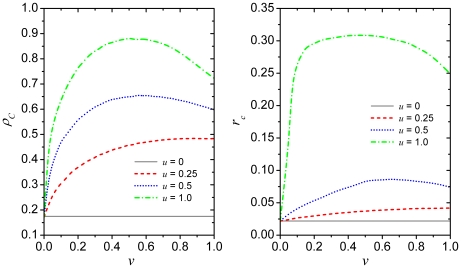

Since the snapshots presented in Fig.

1 can be used primarily for an initial qualitative assessment of the

impact of heterogeneous aspirations, we present in Fig. 2 the fraction of cooperators

(left) and the critical cost-to-benefit ratio

(left) and the critical cost-to-benefit ratio

(right) in dependence on

(right) in dependence on  for different values

of

for different values

of  . It can be observed that the promotion of cooperation for

the optimal combination of the two parameters, being

. It can be observed that the promotion of cooperation for

the optimal combination of the two parameters, being  and

and

, is really remarkable. The fraction of cooperators rises

from

, is really remarkable. The fraction of cooperators rises

from  to

to  , while the critical

cost-to-benefit ratio rises a full order of magnitude from

, while the critical

cost-to-benefit ratio rises a full order of magnitude from

to

to  . As tentatively

deduced from the lower three snapshots in Fig. 1, it can also be observed that for high

values of

. As tentatively

deduced from the lower three snapshots in Fig. 1, it can also be observed that for high

values of  an intermediate fraction of type

an intermediate fraction of type

players is optimal for the evolution of cooperation.

Conversely, for low

players is optimal for the evolution of cooperation.

Conversely, for low  the fraction of

cooperators

the fraction of

cooperators  and the critical cost-to-benefit ratio

and the critical cost-to-benefit ratio

both increase monotonously with increasing

both increase monotonously with increasing

. If, however, selecting a particular value of

. If, however, selecting a particular value of

, then the impact of the aspiration parameter

, then the impact of the aspiration parameter

is always such that cooperation is the more promoted the

larger the value of

is always such that cooperation is the more promoted the

larger the value of  . This can be observed

clearly from both panels, and indeed seems like the main driving force behind the

elevated levels of cooperation. Fine-tuning the fraction of players making use of

the aspiration to the fittest (from

. This can be observed

clearly from both panels, and indeed seems like the main driving force behind the

elevated levels of cooperation. Fine-tuning the fraction of players making use of

the aspiration to the fittest (from  downwards since the

downwards since the

limit trivially returns the random selection of potential

strategy sources) at high

limit trivially returns the random selection of potential

strategy sources) at high  can rise the

cooperation level further, but more in the sense of minor adjustments, similarly as

was observed in the past for the impact of uncertainty by strategy adoptions [42] or the impact of

noise [59].

can rise the

cooperation level further, but more in the sense of minor adjustments, similarly as

was observed in the past for the impact of uncertainty by strategy adoptions [42] or the impact of

noise [59].

Figure 2. Promotion of cooperation due to heterogenous aspirations on the square lattice.

Left panel depicts the density of cooperators  in dependence

on the fraction of type

in dependence

on the fraction of type  players

players

for different values of the aspiration parameter

for different values of the aspiration parameter

. Right panel depicts the critical cost-to-benefit

ratio

. Right panel depicts the critical cost-to-benefit

ratio  at which cooperators die out, i.e.

at which cooperators die out, i.e.

, in dependence on

, in dependence on  for different

values of

for different

values of  . Results in both panels convey the message that low

values of

. Results in both panels convey the message that low

values of  require a high fraction of type

require a high fraction of type

players for cooperation to flourish. Conversely,

higher values of

players for cooperation to flourish. Conversely,

higher values of  sustain

cooperation optimally if only half (

sustain

cooperation optimally if only half ( ) of the

players aspires to their most fittest neighbors while the rest chooses whom

to potentially imitate uniformly at random. Optimal conditions for the

evolution of cooperation thus require

) of the

players aspires to their most fittest neighbors while the rest chooses whom

to potentially imitate uniformly at random. Optimal conditions for the

evolution of cooperation thus require  and

and

to be fine-tuned jointly. Depicted results in both

panels were obtained for

to be fine-tuned jointly. Depicted results in both

panels were obtained for  and

and

.

.

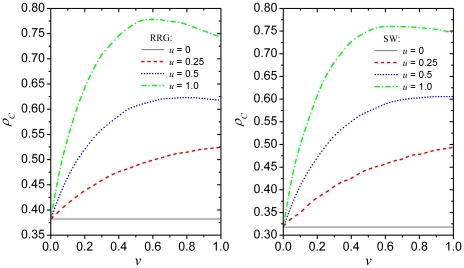

Aiming to generalize the validity of our results, we present in Fig. 3 the fraction of cooperators

in dependence on

in dependence on  for different values

of

for different values

of  as obtained on the random regular graph (left) and the

small-world network (right). The goal is to test to what extend above conclusions

hold also on interaction networks other than the square lattice, in particular such

that are more complex and spatially heterogenous. If comparing the obtained results

with those presented in the left panel of Fig. 2, it seems save to conclude that they are

to a very large degree qualitatively identical. Some differences nevertheless can be

observed. The first is that what constitutes a high

as obtained on the random regular graph (left) and the

small-world network (right). The goal is to test to what extend above conclusions

hold also on interaction networks other than the square lattice, in particular such

that are more complex and spatially heterogenous. If comparing the obtained results

with those presented in the left panel of Fig. 2, it seems save to conclude that they are

to a very large degree qualitatively identical. Some differences nevertheless can be

observed. The first is that what constitutes a high  limit is a bit higher

on complex networks than on the regular lattice. Note that for

limit is a bit higher

on complex networks than on the regular lattice. Note that for

the optimal fraction of type

the optimal fraction of type  players is practically

still

players is practically

still  . Even for

. Even for  the bell-shaped

dependence on

the bell-shaped

dependence on  is far less pronounced than on the square lattice, and the

optimal

is far less pronounced than on the square lattice, and the

optimal  (the peak of

(the peak of  ) is closer to

) is closer to

than

than  . The second difference

is, looking relatively to the starting point at

. The second difference

is, looking relatively to the starting point at  , that the promotion of

cooperation due to positive

, that the promotion of

cooperation due to positive  and

and

is somewhat less prolific. This is, however, not that

surprising since complex networks in general promote cooperation already on their

own [6], and thus

secondary promotive mechanisms may therefore become less expressed. Aside from these

fairly mild differences though, we can conclude that heterogenous aspirations do

promote cooperation irrespective of the underlying interaction network, and that the

details of the promotive effect are largely universal and predictable.

is somewhat less prolific. This is, however, not that

surprising since complex networks in general promote cooperation already on their

own [6], and thus

secondary promotive mechanisms may therefore become less expressed. Aside from these

fairly mild differences though, we can conclude that heterogenous aspirations do

promote cooperation irrespective of the underlying interaction network, and that the

details of the promotive effect are largely universal and predictable.

Figure 3. Promotion of cooperation due to heterogenous aspirations on the random regular graph (RRG) and the small-world (SW) network.

Left panel depicts the density of cooperators  in dependence

on the fraction of type

in dependence

on the fraction of type  players

players

for different values of the aspiration parameter

for different values of the aspiration parameter

for the RRG. Right panel depicts

for the RRG. Right panel depicts

in dependence on

in dependence on  for different

values of

for different

values of  for the Watts-Strogatz SW network with the fraction

of rewired links equalling

for the Watts-Strogatz SW network with the fraction

of rewired links equalling  . These results

are in agreement with those presented in Fig. 2, supporting the conclusion that

the impact of heterogenous aspirations on the evolution of cooperation is

robust against alterations of the interaction network. As on the square

lattice, low, but also intermediate, values of

. These results

are in agreement with those presented in Fig. 2, supporting the conclusion that

the impact of heterogenous aspirations on the evolution of cooperation is

robust against alterations of the interaction network. As on the square

lattice, low, but also intermediate, values of

require

require  for

cooperation to thrive, while higher values of

for

cooperation to thrive, while higher values of

sustain cooperation optimally only if

sustain cooperation optimally only if

. Depicted results in both panels were obtained for

. Depicted results in both panels were obtained for

and

and  .

.

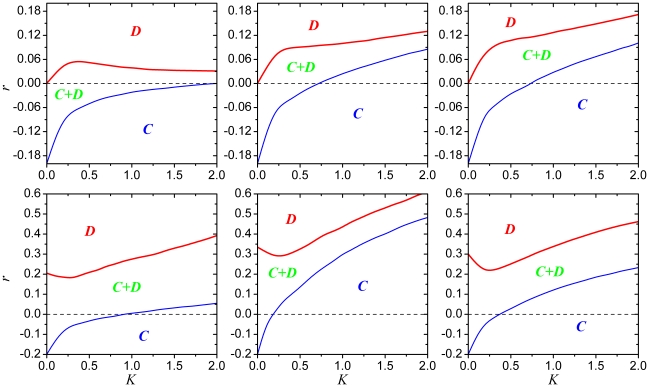

Next, we proceed with examining how positive values of

and

and  fare under different

levels of uncertainty by strategy adoptions. The latter can be tuned via

fare under different

levels of uncertainty by strategy adoptions. The latter can be tuned via

[see Eq. (3)], which acts as a temperature

parameter in the employed Fermi strategy adoption function [38]. Accordingly, when

[see Eq. (3)], which acts as a temperature

parameter in the employed Fermi strategy adoption function [38]. Accordingly, when

all information is lost and the strategies are adopted by

means of a coin toss. Note that this aspect has thus far not received any attention

here as

all information is lost and the strategies are adopted by

means of a coin toss. Note that this aspect has thus far not received any attention

here as  was fixed. The matter is not trivial to address because

uncertainty and noise can have a rather profound impact on the evolution of

cooperation [40],

[42], [59]–[62], and thus

care needs to be exercised. The safest and most accurate way to approach the problem

is by means of phase diagrams. Since we have two additional parameters

(

was fixed. The matter is not trivial to address because

uncertainty and noise can have a rather profound impact on the evolution of

cooperation [40],

[42], [59]–[62], and thus

care needs to be exercised. The safest and most accurate way to approach the problem

is by means of phase diagrams. Since we have two additional parameters

( and

and  ) against which we want

to test the impact of

) against which we want

to test the impact of  , we determined full

, we determined full

phase diagrams for six characteristic combinations of

phase diagrams for six characteristic combinations of

and

and  on the square lattice.

Obtained results are presented in Fig.

4. Notably, the phase diagram presented in the top left panel of Fig. 4 is well-known, implying the

existence of an optimal level of uncertainty for the evolution of cooperation, as

was previously reported in [42], [59]. In particular, note that the

on the square lattice.

Obtained results are presented in Fig.

4. Notably, the phase diagram presented in the top left panel of Fig. 4 is well-known, implying the

existence of an optimal level of uncertainty for the evolution of cooperation, as

was previously reported in [42], [59]. In particular, note that the

transition line is bell shaped, indicating that

transition line is bell shaped, indicating that

is the optimal temperature at which cooperators are able to

survive at the highest value of

is the optimal temperature at which cooperators are able to

survive at the highest value of  . Importantly though,

this phenomenon can only be observed on interaction topologies lacking overlapping

triangles [63],

[64].

Interestingly, increasing

. Importantly though,

this phenomenon can only be observed on interaction topologies lacking overlapping

triangles [63],

[64].

Interestingly, increasing  from

from

(top row) to

(top row) to  (bottom row)

completely eradicates (as do interaction networks incorporating overlapping

triangles) the existence of an optimal

(bottom row)

completely eradicates (as do interaction networks incorporating overlapping

triangles) the existence of an optimal  , and in fact

qualitatively reverses the dependence. The

, and in fact

qualitatively reverses the dependence. The  transition line has an

inverted bell-shaped outlay, indicating the existence of the worst rather than an

optimal temperature

transition line has an

inverted bell-shaped outlay, indicating the existence of the worst rather than an

optimal temperature  for the evolution of

cooperation. The qualitative changes are less profound if

for the evolution of

cooperation. The qualitative changes are less profound if

is kept constant at

is kept constant at  (top row) and

(top row) and

increases (from left to right). Still, however, the

bell-shaped outlay of the

increases (from left to right). Still, however, the

bell-shaped outlay of the  transition gives way

to a monotonically increasing curve, saturating only for high

transition gives way

to a monotonically increasing curve, saturating only for high

. These qualitative changes in the phase diagrams imply that

increasing the aspiration parameter

. These qualitative changes in the phase diagrams imply that

increasing the aspiration parameter  or the fraction of

players abiding to it (type

or the fraction of

players abiding to it (type  ) effectively alters

the interaction network. While the square lattice obviously lacks overlapping

triangles and thus enables the observation of an optimal

) effectively alters

the interaction network. While the square lattice obviously lacks overlapping

triangles and thus enables the observation of an optimal

for small enough values of

for small enough values of  and

and

(or a combination thereof, as is the case in the top left

panels), trimming the likelihood of who will act as a strategy source and how many

players will actually aspire to their fittest neighbors seems to effectively enhance

linkage among essentially disconnected triplets and thus precludes the same

observation. It is instructive to note that a similar phenomenon was observed

recently in public goods games, where the joint membership in large groups was also

found to alter the effective interaction network and thus the impact of uncertainly

on the evolution of cooperation [64].

(or a combination thereof, as is the case in the top left

panels), trimming the likelihood of who will act as a strategy source and how many

players will actually aspire to their fittest neighbors seems to effectively enhance

linkage among essentially disconnected triplets and thus precludes the same

observation. It is instructive to note that a similar phenomenon was observed

recently in public goods games, where the joint membership in large groups was also

found to alter the effective interaction network and thus the impact of uncertainly

on the evolution of cooperation [64].

Figure 4. Full  phase diagrams for the square lattice.

phase diagrams for the square lattice.

Top row depicts results for the aspiration parameter

while the bottom row features results for

while the bottom row features results for

. In both rows the fraction of type

. In both rows the fraction of type

players

players  is

is

,

,  and

and

from left to right. The outline of panels thus

corresponds to the snapshots presented in Fig. 1. Thin blue and thick red lines

mark the border between stationary pure

from left to right. The outline of panels thus

corresponds to the snapshots presented in Fig. 1. Thin blue and thick red lines

mark the border between stationary pure  and

and

phases and the mixed

phases and the mixed  phase,

respectively. In agreement with previous works [42], [63], it can be observed that

for

phase,

respectively. In agreement with previous works [42], [63], it can be observed that

for  and

and  (top left)

there exists an intermediate uncertainty in the strategy adoption process

(an intermediate value of

(top left)

there exists an intermediate uncertainty in the strategy adoption process

(an intermediate value of  ) for which the

survivability of cooperators is optimal, i.e.

) for which the

survivability of cooperators is optimal, i.e.

is maximal. Conversely, while the borderline

separating the pure

is maximal. Conversely, while the borderline

separating the pure  and the mixed

and the mixed

phase for all the other combinations of

phase for all the other combinations of

and

and  exhibits a

qualitatively identical outlay as for the

exhibits a

qualitatively identical outlay as for the  and

and

case, the

case, the  transition is

qualitatively different and very much dependent on the particularities

players' aspirations. Note that in all the bottom panels there exist an

intermediate value of

transition is

qualitatively different and very much dependent on the particularities

players' aspirations. Note that in all the bottom panels there exist an

intermediate value of  for which

for which

is minimal rather than maximal, while towards the

large

is minimal rather than maximal, while towards the

large  limit

limit  increases,

saturating only for

increases,

saturating only for  (not shown).

In the top middle and right panel, on the other hand, the bell-shaped outlay

of the

(not shown).

In the top middle and right panel, on the other hand, the bell-shaped outlay

of the  transition gives way to a monotonically increasing

curve, again saturating only for

transition gives way to a monotonically increasing

curve, again saturating only for  . It can thus

be concluded that, while the aspiration based promotion of cooperation is

largely independent of

. It can thus

be concluded that, while the aspiration based promotion of cooperation is

largely independent of  , the details

of phase transition are very much affected, which can be attributed to an

effective alterations of the interaction network due to preferred strategy

sources (see also main text for details).

, the details

of phase transition are very much affected, which can be attributed to an

effective alterations of the interaction network due to preferred strategy

sources (see also main text for details).

In terms of the facilitation of cooperation, however, it can be concluded that the

promotive impact of positive values of  and

and

prevails irrespective of

prevails irrespective of  . By comparing the

extend of pure

. By comparing the

extend of pure  and mixed

and mixed  regions for different

pairs of the two parameters, we can observe that for small values of

regions for different

pairs of the two parameters, we can observe that for small values of

(top panels in Fig. 4) it is best if all the players, i.e.

(top panels in Fig. 4) it is best if all the players, i.e.

, aspire to their slightly (note that

, aspire to their slightly (note that

is small) fitter neighbors, while for large

is small) fitter neighbors, while for large

(bottom panels in Fig. 4) it is best if only approximately half of

the players, i.e.

(bottom panels in Fig. 4) it is best if only approximately half of

the players, i.e.

, aspire to their most fittest neighbors. The same

conclusions were stated already upon the inspection of results presented in Figs. 2 and 3, and with this we now affirm that not only is

the promotion of cooperation via heterogeneous aspirations robust against

differences in the interaction networks, but also against variations in the

uncertainty by strategy adoptions.

, aspire to their most fittest neighbors. The same

conclusions were stated already upon the inspection of results presented in Figs. 2 and 3, and with this we now affirm that not only is

the promotion of cooperation via heterogeneous aspirations robust against

differences in the interaction networks, but also against variations in the

uncertainty by strategy adoptions.

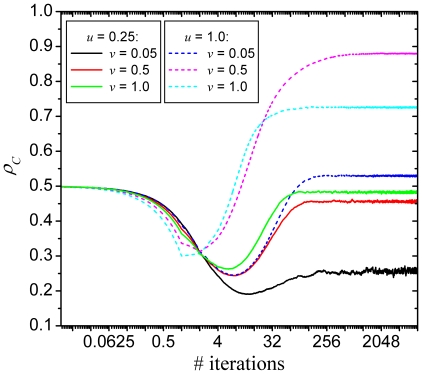

It remains of interest to elucidate why then cooperative behavior is in fact promoted

by positive values of  and

and

. To provide answers, we show in Fig. 5 time courses of

. To provide answers, we show in Fig. 5 time courses of

for different characteristic combination of the two main

parameters that we have used throughout this work. What should attract the attention

is the fact that in the most early stages of the evolutionary process (note that

values of

for different characteristic combination of the two main

parameters that we have used throughout this work. What should attract the attention

is the fact that in the most early stages of the evolutionary process (note that

values of  were recorded also in-between full iteration steps) it

appears as if defectors would actually fare better than cooperators. This is

actually what one would expect, given that defectors are, as individuals, more

successful than cooperators and will thus be chosen more likely as potential

strategy donors if

were recorded also in-between full iteration steps) it

appears as if defectors would actually fare better than cooperators. This is

actually what one would expect, given that defectors are, as individuals, more

successful than cooperators and will thus be chosen more likely as potential

strategy donors if  is positive. This

should in turn amplify their chances of spreading and ultimately result in the

decimation of cooperators (indeed, only between 20–30% survive). Quite

surprisingly though, the tide changes fairly fast, and as one can observe from the

presented time courses, frequently the more so the deeper the initial downfall of

cooperators. We argue that for positive values of

is positive. This

should in turn amplify their chances of spreading and ultimately result in the

decimation of cooperators (indeed, only between 20–30% survive). Quite

surprisingly though, the tide changes fairly fast, and as one can observe from the

presented time courses, frequently the more so the deeper the initial downfall of

cooperators. We argue that for positive values of  and

and

a negative feedback effect occurs, which halts and

eventually reverts what appears to be a march of defectors toward dominance. Namely,

in the very early stages of the game defectors are able to plunder very efficiently,

which quickly results in a state where there are hardly any cooperators left to

exploit. Consequently, the few remaining clusters of cooperators start recovering

lost ground against weakened defectors. Crucial thereby is the fact that the

clusters formed by cooperators are impervious to defector attacks even at high

values of

a negative feedback effect occurs, which halts and

eventually reverts what appears to be a march of defectors toward dominance. Namely,

in the very early stages of the game defectors are able to plunder very efficiently,

which quickly results in a state where there are hardly any cooperators left to

exploit. Consequently, the few remaining clusters of cooperators start recovering

lost ground against weakened defectors. Crucial thereby is the fact that the

clusters formed by cooperators are impervious to defector attacks even at high

values of  because of the positive selection towards the fittest

neighbors acting as strategy sources (occurring for

because of the positive selection towards the fittest

neighbors acting as strategy sources (occurring for  ). In a sea of

cooperators this is practically always another cooperator rather than a defector

trying to penetrate into the cluster. This newly identified mechanism ultimately

results in fairly widespread cooperation that goes beyond what can be warranted by

the spatial reciprocity alone (see e.g.

[6]), and this

irrespective of the underlying interaction network and uncertainty by strategy

adoptions.

). In a sea of

cooperators this is practically always another cooperator rather than a defector

trying to penetrate into the cluster. This newly identified mechanism ultimately

results in fairly widespread cooperation that goes beyond what can be warranted by

the spatial reciprocity alone (see e.g.

[6]), and this

irrespective of the underlying interaction network and uncertainty by strategy

adoptions.

Figure 5. Time courses of the density of cooperators on the square lattice.

Results are presented for the aspiration parameters

(solid lines) and

(solid lines) and  (dashed

lines), each for three different fractions of type

(dashed

lines), each for three different fractions of type

players

players  , as depicted

on the figure. The crucial feature of all time courses is the initial

temporary downfall of cooperators, which sets in for all depicted

combinations of

, as depicted

on the figure. The crucial feature of all time courses is the initial

temporary downfall of cooperators, which sets in for all depicted

combinations of  and

and

. Quite remarkably, what appears to become an ever

faster extinction eventually becomes a rise to, at least in some cases,

near-dominance. Note that the horizontal axis is logarithmic and that values

of

. Quite remarkably, what appears to become an ever

faster extinction eventually becomes a rise to, at least in some cases,

near-dominance. Note that the horizontal axis is logarithmic and that values

of  were recorded also in-between full iteration steps

to ensure a proper resolution. Depicted results were obtained for

were recorded also in-between full iteration steps

to ensure a proper resolution. Depicted results were obtained for

and

and  .

.

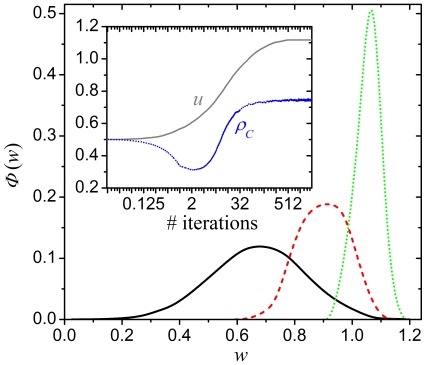

Finally, it is instructive to examine whether an optimal intermediate value of

, determining the aspiration level of player

, determining the aspiration level of player

, can emerge spontaneously from an initial array of normally

distributed values. This would imply that natural selection indeed favors

individuals with a specific aspiration level, which would in turn extend the

credibility of thus far presented results that were obtained primarily in a top-down

manner [by optimizing a population-level property (cooperation) by means of an

appropriate selection of parameters determining the aspiration level of

individuals]. For this purpose we omit the division of the population on

players of type

, can emerge spontaneously from an initial array of normally

distributed values. This would imply that natural selection indeed favors

individuals with a specific aspiration level, which would in turn extend the

credibility of thus far presented results that were obtained primarily in a top-down

manner [by optimizing a population-level property (cooperation) by means of an

appropriate selection of parameters determining the aspiration level of

individuals]. For this purpose we omit the division of the population on

players of type  and

and  , and initially assign

to every player a value

, and initially assign

to every player a value  that is drawn randomly

from a Gaussian distribution with a given mean

that is drawn randomly

from a Gaussian distribution with a given mean  and standard deviation

and standard deviation

. Then if player

. Then if player  adopts the strategy

from player

adopts the strategy

from player  also

also  becomes equal to

becomes equal to

(see Methods for

details). Results obtained with this alternative coevolutionary model are presented

in Fig. 6. It can be observed

that the initial Gaussian distribution sharpens fast around an intermediate value of

(see Methods for

details). Results obtained with this alternative coevolutionary model are presented

in Fig. 6. It can be observed

that the initial Gaussian distribution sharpens fast around an intermediate value of

, which then gradually becomes more and more frequent in the

population as the natural selection spontaneously eliminates the less favorable

values that warrant a lower individual fitness. The final state is a population

where virtually all players have an identical aspiration level

, which then gradually becomes more and more frequent in the

population as the natural selection spontaneously eliminates the less favorable

values that warrant a lower individual fitness. The final state is a population

where virtually all players have an identical aspiration level

, and accordingly, the outcome in terms of the stationary

density of cooperators is equal to that obtained with the original model having

, and accordingly, the outcome in terms of the stationary

density of cooperators is equal to that obtained with the original model having

and

and  . In this sense the

preceding results are validated and their generality extended by means of a

bottom-up approach entailing a spontaneous coevolution towards an intermediate

individually optimal aspiration level. We note, however, that with this simple

coevolutionary model the result that heterogeneous aspirations promote cooperation

is not exactly reproduced. Further studies on more sophisticated models

incorporating coevolving aspirations are required to arrive spontaneously at a

heterogeneous distribution of individual aspiration levels. Inspirations for this

can be found in the recent review on coevolutionary games [23], and we are looking forward to

further developments in this direction.

. In this sense the

preceding results are validated and their generality extended by means of a

bottom-up approach entailing a spontaneous coevolution towards an intermediate

individually optimal aspiration level. We note, however, that with this simple

coevolutionary model the result that heterogeneous aspirations promote cooperation

is not exactly reproduced. Further studies on more sophisticated models

incorporating coevolving aspirations are required to arrive spontaneously at a

heterogeneous distribution of individual aspiration levels. Inspirations for this

can be found in the recent review on coevolutionary games [23], and we are looking forward to

further developments in this direction.

Figure 6. Spontaneous fixation towards an intermediate aspiration level by means of natural selection.

Presented results were obtained with the alternative model where players are

not divided into two groups and initially every player is assigned a random

aspiration level  drawn from a

Gaussian distribution with the mean

drawn from a

Gaussian distribution with the mean  and standard

deviation

and standard

deviation  . The main panel depicts the distributions

. The main panel depicts the distributions

of individual aspiration levels as recorded at

of individual aspiration levels as recorded at

(solid black line),

(solid black line),  (dashed red

line) and

(dashed red

line) and  (dotted green line) full iteration steps. The

fixation towards a dominant average value

(dotted green line) full iteration steps. The

fixation towards a dominant average value  due to natural

selection is evident since the interval of

due to natural

selection is evident since the interval of  values still

present in the population becomes more and more narrow as time progresses.

The inset shows the convergence of

values still

present in the population becomes more and more narrow as time progresses.

The inset shows the convergence of  (solid gray

line) and

(solid gray

line) and  (dotted blue line). The initial temporary downfall

of cooperators, followed by the rise to near-dominance, is well-expressed

also in the coevolutionary setup, and the stationary density agrees well

with the results obtained by means of the original model with

(dotted blue line). The initial temporary downfall

of cooperators, followed by the rise to near-dominance, is well-expressed

also in the coevolutionary setup, and the stationary density agrees well

with the results obtained by means of the original model with

and

and  (compare with

the dashed cyan line in Fig.

5). Note that in the inset the horizontal axis is logarithmic and

that values of

(compare with

the dashed cyan line in Fig.

5). Note that in the inset the horizontal axis is logarithmic and

that values of  and

and

were recorded also in-between full iteration steps

to ensure a proper resolution. Depicted results were obtained for

were recorded also in-between full iteration steps

to ensure a proper resolution. Depicted results were obtained for

and

and  .

.

Discussion

We have shown that heterogenous aspiration to the fittest, i.e. the

propensity of designating the most successful neighbor as being the role model, may

be seen as a universally applicable promoter of cooperation that works on different

interaction networks and under different levels of stochasticity. For low and

moderate values of the aspiration parameter  cooperation thrives

best if the total population abides to aspiring to the fittest. For large values of

cooperation thrives

best if the total population abides to aspiring to the fittest. For large values of

, however, it is best if only approximately half of the

players persuasively attempt to copy their most successful neighbors while the rest

chooses their opponents uniformly at random. The optimal evolution of cooperation

thus requires fine-tuning of both, the density of players that are prone to aspiring

to the fittest, as well as the aspiration parameter that determines how fit a

neighbor actually must be in order to be considered as the potential source of the

new strategy. In addition, by studying an alternative model where individual

aspiration levels were also subject to evolution, we have shown that an intermediate

value of the aspiration level emerges spontaneously through natural selection, thus

supplementing the main results by means of a coevolutionary approach.

, however, it is best if only approximately half of the

players persuasively attempt to copy their most successful neighbors while the rest

chooses their opponents uniformly at random. The optimal evolution of cooperation

thus requires fine-tuning of both, the density of players that are prone to aspiring

to the fittest, as well as the aspiration parameter that determines how fit a

neighbor actually must be in order to be considered as the potential source of the

new strategy. In addition, by studying an alternative model where individual

aspiration levels were also subject to evolution, we have shown that an intermediate

value of the aspiration level emerges spontaneously through natural selection, thus

supplementing the main results by means of a coevolutionary approach.

Notably, the extensions of the prisoner's dilemma game we have considered here

seem very reasonable and are in fact easily justifiable with realistic examples. For

example, it is a fact that people will, in general, much more likely follow a

successful individual than somebody who is just struggling to get by. Under certain

adverse circumstances, like in a state of rebelion or in revolutionary times,

however, it is also possible that individuals will be inspired to copy their less

successful partners or those that seem to do more harm than good. In many ways it

seems that the ones who are satisfied with just picking somebody randomly to aspire

to are the ones that are most difficult to come by. In this sense the rather

frequently adopted random selection of a neighbor, retrieved in our case if

(or equivalently

(or equivalently  ), seems in many ways

like the least probable alternative. In this sense it is interesting to note that

our aspiring to the fittest becomes identical to the frequently adopted, especially

in the early seminal works on games on grids [26], [33], [34], “best takes all”

adoption rule if

), seems in many ways

like the least probable alternative. In this sense it is interesting to note that

our aspiring to the fittest becomes identical to the frequently adopted, especially

in the early seminal works on games on grids [26], [33], [34], “best takes all”

adoption rule if  ,

,  in Eq. (2), and

in Eq. (2), and

in Eq. (3). Although in our simulations we never quite reach

the “best takes all” limit, and thus a direct comparison with the

seminal works is somewhat circumstantial, we find here that the intermediate regions

of heterogenous aspirations offer fascinating new insights into the evolution of

cooperation, and we hope that this work will inspire future studies, especially in

terms of understanding the emergence of successful leaders in societies via a

coevolutionary process [23].

in Eq. (3). Although in our simulations we never quite reach

the “best takes all” limit, and thus a direct comparison with the

seminal works is somewhat circumstantial, we find here that the intermediate regions

of heterogenous aspirations offer fascinating new insights into the evolution of

cooperation, and we hope that this work will inspire future studies, especially in

terms of understanding the emergence of successful leaders in societies via a

coevolutionary process [23].

Methods

An evolutionary prisoner's dilemma game with the temptation to defect

(the highest payoff received by a defector if playing

against a cooperator), reward for mutual cooperation

(the highest payoff received by a defector if playing

against a cooperator), reward for mutual cooperation  , the punishment for

mutual defection

, the punishment for

mutual defection  , and the sucker's payoff

, and the sucker's payoff

(the lowest payoff received by a cooperator if playing

against a defector) is used as the basis for our simulations. Without loss of

generality the payoffs can be rescaled as

(the lowest payoff received by a cooperator if playing

against a defector) is used as the basis for our simulations. Without loss of

generality the payoffs can be rescaled as  ,

,

,

,  and

and

, where

, where  is the cost-to-benefit

ratio [5]. For

positive

is the cost-to-benefit

ratio [5]. For

positive  we have

we have  , thus strictly

satisfying the prisoner's dilemma payoff ranking.

, thus strictly

satisfying the prisoner's dilemma payoff ranking.

As the interaction network, we use either a regular  square lattice, the

random regular graph (RRG) constructed as described in [65], or the small-world (SW) topology

with an average degree of four generated via the Watts-Strogatz algorithm [66]. Each vertex

square lattice, the

random regular graph (RRG) constructed as described in [65], or the small-world (SW) topology

with an average degree of four generated via the Watts-Strogatz algorithm [66]. Each vertex

is initially designated as hosting either players of type

is initially designated as hosting either players of type

or

or  with the probability

with the probability

and

and  , respectively. This

division of players is performed uniformly at random irrespective of their initial

strategies and remains unchanged during the simulations. According to established

procedures, each player is initially also designated either as a cooperator

(

, respectively. This

division of players is performed uniformly at random irrespective of their initial

strategies and remains unchanged during the simulations. According to established

procedures, each player is initially also designated either as a cooperator

( ) or defector (

) or defector ( ) with equal

probability. The game is iterated forward in accordance with the sequential

simulation procedure comprising the following elementary steps. First, player

) with equal

probability. The game is iterated forward in accordance with the sequential

simulation procedure comprising the following elementary steps. First, player

acquires its payoff

acquires its payoff  by playing the game

with all its neighbors. Next, we evaluate in the same way the payoffs of all the

neighbors of player

by playing the game

with all its neighbors. Next, we evaluate in the same way the payoffs of all the

neighbors of player  and subsequently

select one neighbor

and subsequently

select one neighbor  via the

probability

via the

probability

| (1) |

where the sum runs over all the neighbors of player  . Importantly,

. Importantly,

is the so-called selection or aspiration parameter that

depends on the type of player

is the so-called selection or aspiration parameter that

depends on the type of player  according

to

according

to

| (2) |

Evidently, if the aspiration parameter  then irrespective of

then irrespective of

(density of type

(density of type  players) the most

frequently adopted situation is recovered where player

players) the most

frequently adopted situation is recovered where player

is chosen uniformly at random from all the neighbors of

player

is chosen uniformly at random from all the neighbors of

player  . For

. For  and

and

, however, Eqs. (1) and (2) introduce a preference in all

players of type

, however, Eqs. (1) and (2) introduce a preference in all

players of type  (but not in players of type

(but not in players of type  ) to copy the strategy

of those neighbors who have a high fitness, or equivalently, a high payoff

) to copy the strategy

of those neighbors who have a high fitness, or equivalently, a high payoff

. Lastly then, after the neighbor

. Lastly then, after the neighbor

that is aspired to by player

that is aspired to by player  is chosen, player

is chosen, player

adopts the strategy

adopts the strategy  from the selected

player

from the selected

player  with the probability

with the probability

| (3) |

where  denotes the amplitude of noise or its inverse

(

denotes the amplitude of noise or its inverse

( ) the so-called intensity of selection [38]. Irrespective of the values of

) the so-called intensity of selection [38]. Irrespective of the values of

and

and  one full iteration

step involves all players

one full iteration

step involves all players  having a chance to

adopt a strategy from one of their neighbors once.

having a chance to

adopt a strategy from one of their neighbors once.

An alternative model, allowing for individual  values to be subject

to evolution as well, entails omitting the division of the population on two types

of players and assigning to every individual an initial

values to be subject

to evolution as well, entails omitting the division of the population on two types

of players and assigning to every individual an initial

value that is drown randomly from a Gaussian distribution

having mean

value that is drown randomly from a Gaussian distribution

having mean  and standard deviation

and standard deviation  , as was done recently

in [57], for

example. Subsequently, if player

, as was done recently

in [57], for

example. Subsequently, if player  adopts the strategy

from player

adopts the strategy

from player  following the identical procedure as described above for the

original model, then the value of

following the identical procedure as described above for the

original model, then the value of  changes to that of

changes to that of

as well. The key question that we aim to answer with this

model is whether a specific aspiration level is indeed optimal for an individual to

prosper, and if yes, does the selection pressure favor it spontaneously.

Essentially, we are interested in the distribution of

as well. The key question that we aim to answer with this

model is whether a specific aspiration level is indeed optimal for an individual to

prosper, and if yes, does the selection pressure favor it spontaneously.

Essentially, we are interested in the distribution of

values after the stationary fraction of strategies in the

population is reached. A link with the original model can be established by

considering in this case

values after the stationary fraction of strategies in the

population is reached. A link with the original model can be established by

considering in this case  to equal one and

to equal one and

.

.

Results of computer simulations were obtained on populations comprising

to

to  individuals, whereby

the fraction of cooperators

individuals, whereby

the fraction of cooperators  was determined within

was determined within

full iteration steps after sufficiently long transients were

discarded. Moreover, since the heterogeneous preferential selection of neighbors may

introduce additional disturbances, final results were averaged over up to

full iteration steps after sufficiently long transients were

discarded. Moreover, since the heterogeneous preferential selection of neighbors may

introduce additional disturbances, final results were averaged over up to

independent runs for each set of parameter values in order

to assure suitable accuracy.

independent runs for each set of parameter values in order

to assure suitable accuracy.

Acknowledgments

We have benefited substantially from the insightful comments of the Editor James Arthur Robert Marshall and an anonymous referee, which were instrumental for elevating the quality of this work. Helpful discussions with Professor Lianzhong Zhang are gratefully acknowledged as well.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Funding: MP acknowledges support from the Slovenian Research Agency (Grant No. Z1-2032). ZW acknowledges support from the Center for Asia Studies of Nankai University (Grant No. 2010-5) and from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 10672081). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Hofbauer J, Sigmund K. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1998. Evolutionary Games and Population Dynamics. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nowak MA. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 2006. Evolutionary Dynamics. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maynard Smith J. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press; 1982. Evolution and the Theory of Games. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Roca CP, Cuesta JA, Sánchez A. Evolutionary game theory: Temporal and spatial effects beyond replicator dynamics. Phys Life Rev. 2009;6:208–249. doi: 10.1016/j.plrev.2009.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hauert C, Szabó G. Game theory and physics. Am J Phys. 2005;73:405–414. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Szabó G, Fáth G. Evolutionary games on graphs. Phys Rep. 2007;446:97–216. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nowak M, Sigmund K. Game-dynamical aspects of the prisoner's dilemma. Appl Math Comp. 1989;30:191–213. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Moyano LG, Sánchez A. Evolving learning rules and emergence of cooperation in spatial prisoner's dilemma. J Theor Biol. 2009;259:84–95. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2009.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Doebeli M, Hauert C. Models of cooperation based on prisoner's dilemma and snowdrift game. Ecol Lett. 2005;8:748–766. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Szabó G, Szolnoki A, Sznaider GA. Segregation process and phase transition in cyclic predator-prey models with even number of species. Phys Rev E. 2007;76:051921. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.76.051921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Szolnoki A, Perc M, Szabó G, Stark HU. Impact of aging on the evolution of cooperation in the spatial prisoner's dilemma game. Phys Rev E. 2009;80:021901. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.80.021901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Milinski M, Semmann D, Krambeck HJ. Reputation helps to solve the ‘tragedy of the commons’. Nature. 2002;415:424–426. doi: 10.1038/415424a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fehr E. Don't lose your reputation. Nature. 2004;432:449–450. doi: 10.1038/432449a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Van Segbroeck S, Santos FC, Lenaerts T, Pacheco JM. Reacting differently to adverse ties promotes cooperation in social networks. Phys Rev Lett. 2009;102:058105. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.102.058105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maynard Smith J, Parker GA. The logic of asymmetric contests. Anim Behav. 1976;24:159–175. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Selten R. A note on evolutionary stable strategies in asymmetric animal conflicts. J Theor Biol. 1980;84:93–101. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5193(80)81038-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hammerstein P. The role of asymmetries in animal contests. Anim Behav. 1981;29:193–205. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marshall JAR. The donation game with roles played between relatives. J Theor Biol. 2009;260:386–391. doi: 10.1016/j.jtbi.2009.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Milinski M. TIT FOR TAT in sticklebacks and the evolution of cooperation. Nature. 1987;325:533–535. doi: 10.1038/325433a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Hamilton WD. Genetical evolution of social behavior I & II. J Theor Biol. 1964;7:1–52. doi: 10.1016/0022-5193(64)90038-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nowak MA. Five rules for the evolution of cooperation. Science. 2006;314:1560–1563. doi: 10.1126/science.1133755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Schuster S, Kreft JU, Schroeter A, Pfeiffer T. Use of game-theoretical methods in biochemistry and biophysics. J Biol Phys. 2008;34:1–17. doi: 10.1007/s10867-008-9101-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Perc M, Szolnoki A. Coevolutionary games – a mini review. BioSystems. 2010;99:109–125. doi: 10.1016/j.biosystems.2009.10.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lehmann L, Keller L. The evolution of cooperation and altruism - a general framework and a classification of models. J Evol Biol. 2006;19:1365–1376. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2006.01119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Marshall JAR. Ultimate causes and the evolution of altruism. Behav Ecol Sociobiol: in press. 2010.

- 26.Nowak MA, May RM. Evolutionary games and spatial chaos. Nature. 1992;359:826–829. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Albert R, Barabási AL. Statistical mechanics of complex networks. Rev Mod Phys. 2002;74:47–97. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Newman MEJ. The structure and function of complex networks. SIAM Review. 2003;45:167–256. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Boccaletti S, Latora V, Moreno Y, Chavez M, Hwang D. Complex networks: Structure and dynamics. Phys Rep. 2006;424:175–308. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ohtsuki H, Hauert C, Lieberman E, Nowak MA. A simple rule for the evolution of cooperation on graphs and social networks. Nature. 2006;441:502–505. doi: 10.1038/nature04605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lehmann L, Keller L, Sumpter D. The evolution of helping and harming on graphs: the return of the inclusive fitness effect. J Evol Biol. 2007;20:2284–2295. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2007.01414.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Grafen A. An inclusive fitness analysis of altruism on a cyclical network. J Evol Biol. 2007;20:2278–2283. doi: 10.1111/j.1420-9101.2007.01413.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nowak MA, May RM. The spatial dilemmas of evolution. Int J Bifurcat Chaos. 1993;3:35–78. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nowak MA, Bonhoeffer S, May RM. More spatial games. Int J Bifurcat Chaos. 1994;4:33–56. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ohtsuki H, Nowak MA. Evolutionary games on cycles. Proc R Soc Lond B. 2006;273:2249–2256. doi: 10.1098/rspb.2006.3576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Schlag KH. Why imitate, and if so, how? a bounded rational approach to multi-armed bandits. J Econ Theory. 1998;78:130–156. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wang S, Szalay MS, Zhang C, Csermely P. Learning and innovative elements of strategy adoption rules expand cooperative network topologies. PLoS ONE. 2008;3:e1917. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001917. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Szabó G, Tőke C. Evolutionary prisoner's dilemma game on a square lattice. Phys Rev E. 1998;58:69–73. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abramson G, Kuperman M. Social games in a social network. Phys Rev E. 2001;63:030901(R). doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.63.030901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ren J, Wang WX, Qi F. Randomness enhances cooperation: coherence resonance in evolutionary game. Phys Rev E. 2007;75:045101(R). doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.75.045101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chen XJ, Wang L. Promotion of cooperation induced by appropriate payoff aspirations in a small-world networked game. Phys Rev E. 2008;77:017103. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.77.017103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vukov J, Szabó G, Szolnoki A. Cooperation in the noisy case: Prisoner's dilemma game on two types of regular random graphs. Phys Rev E. 2006;73:067103. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.73.067103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Santos FC, Pacheco JM. Scale-free networks provide a unifying framework for the emergence of cooperation. Phys Rev Lett. 2005;95:098104. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.95.098104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]