Abstract

Objective

To determine the utility of adding oral non-absorbable antibiotics to the bowel prep prior to elective colon surgery

Summary background data

Bowel preparation prior to colectomy remains controversial. We hypothesized that mechanical bowel preparation with oral antibiotics (compared to without) was associated with lower rates of SSI.

Methods

24 Michigan hospitals participated in the Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative - Colectomy Best Practices Project. Standard peri-operative data, bowel preparation process measures and C.difficile colitis outcomes were prospectively collected. Among patients receiving mechanical bowel preparation, a logistic regression model generated a propensity score that allowed us to match cases differing only in whether or not they had received oral antibiotics.

Results

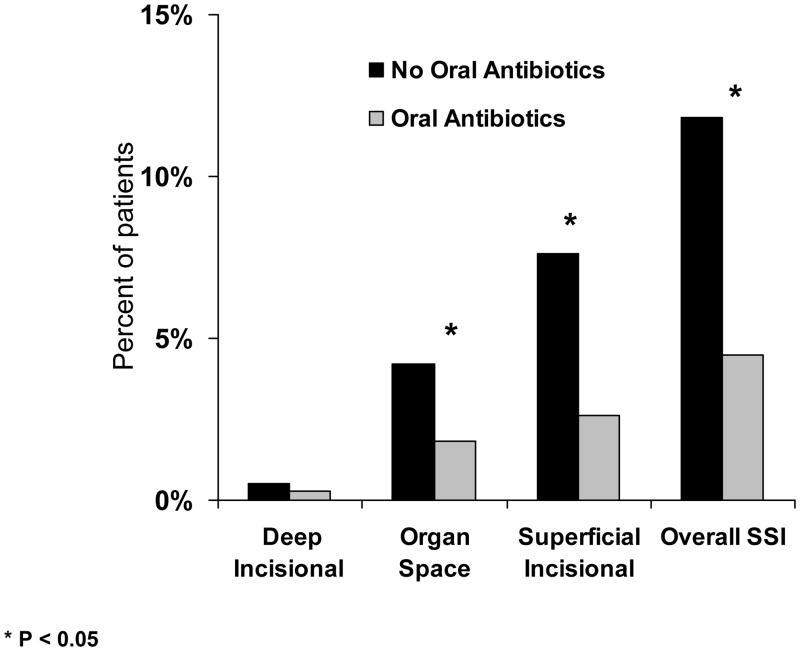

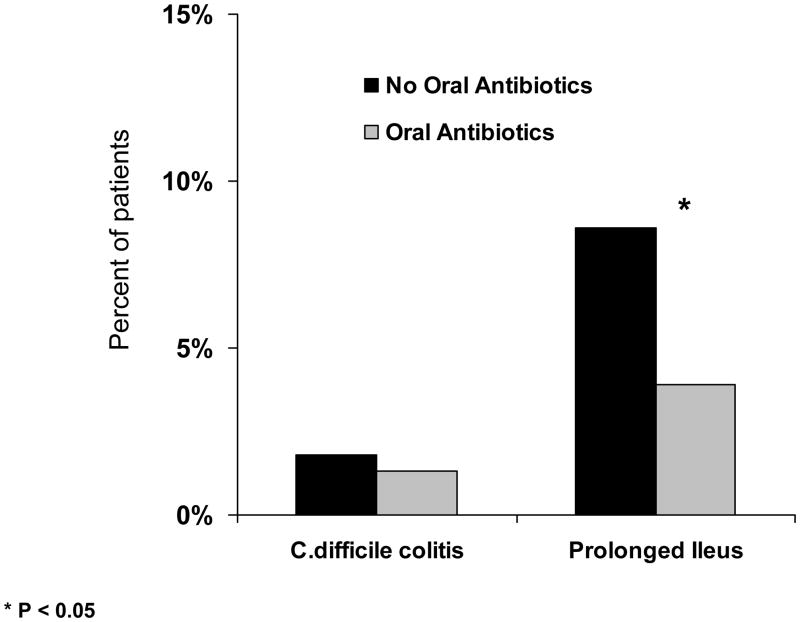

Overall, 2011 elective colectomies were performed over 16 months. Mechanical bowel prep without oral antibiotics was administered to 49.6% of patients, while 36.4% received a mechanical prep and oral antibiotics. Propensity analysis created 370 paired cases (differing only in receiving oral antibiotics). Patients receiving oral antibiotics were less likely to have any SSI (4.5% vs.11.8%, p = 0.0001), to have an organ space infection (1.8% vs. 4.2%, p = 0.044) and to have a superficial SSI (2.6% vs. 7.6%, p = 0.001). Patients receiving bowel prep with oral antibiotics were also less likely to have a prolonged ileus (3.9% vs. 8.6%, p = 0.011) and had similar rates of C. difficile colitis (1.3% vs. 1.8%, p = 0.58).

Conclusions

Most patients in Michigan receive mechanical bowel preparation prior to elective colectomy. Oral antibiotics may reduce the incidence of SSI.

Introduction

For over 50 years surgeons have debated the optimal preparation of the patient for elective colon surgery. The primary focus of this debate has centered on the use of mechanical bowel preparation, and particularly whether or not oral non absorbable antibiotics should be a part of the standard bowel preparation regimen. 1–5 It seemed intuitive to surgeons that reducing the bacterial load of stool in the colon prior to surgery would reduce the incidence of infectious complications. But in later years, as the administration of parenteral antibiotics at the time of surgery became routine, some questioned whether oral antibiotics were necessary. More recently enthusiasm for bowel preparation itself has diminished, oral antibiotics or not. Randomized controlled trials isolating bowel preparation as a variable (bowel preparation yes or no) have failed to show benefit to the bowel preparation. 6–11

But the randomized controlled trials in this area, and the meta-analyses that have studied them, have failed to consider whether or not oral antibiotics were a part of the bowel preparation strategy.6, 9–13 This is an important omission; one relatively recent randomized controlled trial (RCT) demonstrated an important beneficial effect on wound infection rates if oral antibiotics had been administered with mechanical preparation, even in this modern era, in which all patients routinely receive potent parenteral antibiotics.14, 15 As was found in much earlier studies, administration of oral non absorbable antibiotics was associated with a reduced bacterial load in the stool, colonic mucosa, and subcutaneous fat at the site of incision, suggesting a cause and effect relationship with infectious complications.1, 2, 4, 5, 16–19 So far no RCT has compared a strategy of parenteral antibiotic only, without any kind of mechanical bowel prep, to one involving parenteral antibiotics and mechanical bowel prep followed by the administration of oral non absorbable antibiotics. In the absence of such a trial we have encouraged the surgical community to avoid a rush to judgement.20 There may still be an important place for a bowel preparation approach in modern colonic surgery.

In analyzing the practice of colonic surgery in Michigan, using the structure of the Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative (MSQC), we have come across what is a natural and empirical experiment regarding the question of oral antibiotics. While the vast majority of surgeons in our state routinely do prescribe mechanical preparation prior to surgery, approximately half do not add oral non-absorbable antibiotics to the preparation. To seize upon this opportunity for analysis, we used a propensity matching approach to adjust for potential differences in patient characteristics and selection bias, and we used a very narrowly defined case selection approach to minimize differences in case mix. We then analyzed the two groups with regard to a variety of post operative outcomes routinely measured by the ACS-NSQIP, and also with regard to several colon specific outcome variables which we developed locally, and which are not a part of the ACS-NSQIP. Because some surgeons have informally voiced a concern that the use of oral non absorbable antibiotics might predispose to post operative Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) colitis, we were particularly careful to define and measure this outcome in the two groups.21, 22

Methods

The MSQC Colectomy Best Practices Study

The MSQC represents a partnership between two entities: Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Michigan/The Blue Care Network (BCBSM/BCN) and 34 Michigan hospitals.23, 24 BCBSM/BCN has funded hospital participation in the American College of Surgeons-National Surgical Quality Improvement Program (ACS-NSQIP) for participating hospitals. The MSQC uses the basic data platform of the ACS-NSQIP to standardize data collection and outcomes and has also developed new process and outcome measures which pertain specifically to the colectomy procedure.

All MSQC hospitals (N=34) were offered the opportunity to participate, and 24 centers agreed. Cases selected for study were open segmental colectomy (44204), laparoscopic segmental colectomy (44140), ileocolic resection (44205), and laparoscopic ileocolic resection (44160). Participating centers captured defined colectomy cases when they fell within the ACS-NSQIP sampling framework, and were offered the option of adding all additional numbers of these same case types outside the ACS-NSQIP sampling methodology if work load allowed.25 All standard ACS-NSQIP pre-operative, operative, and post-operative variables were collected. Additional data was collected on the type of bowel preparation, diabetic management, venous thromboembolism prophylaxis, surgical site prevention practices (i.e. normothermia, and antibiotic dosing), operative techniques, the incidence of C.difficile colitis, anastomotic leak, ileus, ureteral injury, and need for splenectomy.

Study Population

Over the study period (Aug 2007 to April 2009) data was entered on 2011 colectomy operations (open or laparoscopic segmental or ileocolic resection). Emergent colectomy was completed on 263 patients, and these patients were eliminated from all analysis. This left 1748 patients who underwent an eligible colon operation over the study period. Further, 195 patients (11.3%) did not receive any bowel preparation prior to elective colon surgery. These patients were also eliminated from the adjusted and matched analysis.

Data Analysis

Overall, 1,553 patients received a bowel preparation prior to elective colon surgery. Differences among the demographic and clinical characteristics of the two study groups (no oral antibiotic and oral antibiotic at the time of bowel preparation) were assessed using simple univariate analysis. Significant differences were noted. To manage these differences and concerns regarding selection bias (patient selected to receive or not to receive oral antibiotics), we performed a propensity matched cohort analysis.

Multiple regression analysis was used to impute data for missing lab values for the analysis, as previously described.26 Regression models were developed to predict missing lab values from existing lab values. Equations were developed for each hospital and month to adjust for seasonality and differences in laboratory technique.

Propensity score matching was used to adjust for factors statistically associated with receiving pre-operative non-absorbable antibiotics as part of the bowel prep. The propensity score is the probability of receiving an oral antibiotic, conditional on both pre-operative and intra-operative factors. The propensity score was calculated using a standard multivariate logistic regression analysis, the primary outcome measure being the addition of oral antibiotics at the time of bowel preparation. Covariates in the logistic regression model included the following pre-operative variables: blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, bilirubin, SGOT, white blood cell count, alkaline phosphatase, platelet count, prothrombin time, PTT, albumin, race, age, sepsis, functional status, cancer diagnosis, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, hemiparesis, previous stroke, steroid use, recent weight loss, bleeding diathesis, coronary artery disease, alcohol use, peripheral vascular disease, pre-operative dyspnea, pre-operative smoking status, case RVU (measure of case complexity), gender, diabetes status, compliance with bowel preparation, and insurance status. In addition, the logistic regression model included the following peri-operative variables: pre-operative ureteral stents, postoperative wound left open, intra-operative fecal contamination, intra-operative ureteral injury, peri-operative glucose levels, pre-operative and intra-operative antibiotic administration, epidural catheter utilization, intra-operative transfusion, and operative duration. The c-statistic for the model was 0.71, and the Hesmer and Lemeshow p-value was 0.648.

Once the propensity score was derived, it was used to match patients (one patient receiving pre-operative oral non-absorbable antibiotics and one patient not receiving them at the time of bowel preparation). In short, these patients were matched based on their probability score of receiving an oral antibiotic prior to elective colon surgery. We used the SAS Greedy Matching algorithm to do the case matching yielding a case-controlled subset of the data. To test the success of the matching, we compared pre-operative and intra-operative factors using a chi-square exact analysis to determine if there were statistical differences between the bowel preps with and without an antibiotic before and after the propensity matching. (Table 1) The propensity matching was deemed successful if there was no longer any statistical difference among the clinical factors between the two groups.

Table 1.

| Unmatched Cases | Matched Cases | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Risk Factor | No Oral Antibiotic (N = 915) | Oral Antibiotic (N = 638) | p | No Oral Antibiotic (N = 370) | Oral Antibiotic (N = 370) | p |

| Black | 12.3%(113) | 9.6%(61) | 0.051 | 12.1%(45) | 10.5%(39) | 0.281 |

| Male | 48.2%(441) | 52.5%(335) | .0046 | 51.1%(189) | 51.6%(191) | 0.471 |

| Age (mean) | 65.9 | 65.0 | 0.204 | 66.1 | 66.0 | 0.969 |

| Public Insurance | 55.8%(511) | 53.1%(339) | 0.106 | 56.5%(209) | 57.0%(211) | 0.470 |

| Steroids | 4.0%(37) | 2.4%(15) | 0.046 | 2.4%(9) | 2.7%(10) | 0.500 |

| Weight Loss | 4.3%(39) | 2.5%(16) | 0.044 | 4.1%(15) | 3.2%(12) | 0.348 |

| COPD | 5.9%(54) | 6.0%(38) | 0.517 | 5.4%(20) | 5.1%(19) | 0.500 |

| Diabetes | 19.5%(178) | 16.5%(105) | 0.075 | 20.3%(75) | 19.7%(73) | 0.927 |

| Sepsis | 4.4%(40) | 2.4%(15) | 0.036 | 2.7%(10) | 2.2%(8) | 0.406 |

| Total Dependent | 0.3%(3) | 0.8%(5) | 0.189 | 0.8%(3) | 0.5%(2) | 0.500 |

| BMI (mean) | 28.0 | 29.1 | 0.005 | 28.8 | 28.6 | 0.666 |

| RVU’s (mean) | 23.2 | 23.6 | 0.000 | 23.4 | 23.5 | 0.746 |

| Open Time (min) | 126.4 | 134.2 | 0.008 | 129.0 | 130.3 | 0.749 |

| Na (mMol/L) (mean) | 139.0 | 139.4 | 0.006 | 139.1 | 139.4 | 0.127 |

| PTT (sec) (mean) | 29.9 | 30.7 | 0.001 | 30.4 | 30.3 | 0.863 |

| Creat (mg/dL) (mean) | 0.99 | 1.02 | 0.314 | 1.01 | 0.99 | 0.669 |

| Albumin (g/dL) (mean) | 3.73 | 3.77 | 0.137 | 3.78 | 3.79 | 0.885 |

Having balanced the covariates across two study groups, we then analyzed outcomes using this matched dataset. The outcome measures of interest included: deep incisional surgical site infection, organ space infection, superficial incisional surgical site infection, C. difficile colitis, and prolonged ileus. A prolonged ileus was defined as an ileus lasting greater than 7 days from the index operation. The remainder of these outcome measures are defined by the ACS-NSQIP.27 The exact chi-square test was also used to test for differences in outcomes between the two groups using our adjusted (matched) dataset. Except for the SAS (v9.1) matching algorithm, all analyses were performed with SPSS v17.0.

Results

85.7% of patients in Michigan received a mechanical bowel prep prior to elective colon surgery, 49.3% of patients received a mechanical bowel prep alone, while 36.4% of patients received mechanical bowel prep along with oral non-absorbable antibiotics. 11.3% of patients received no bowel preparation and in 3.0% of cases bowel preparation data was not available. (Figure 1) An unadjusted analysis of non emergent cases showed that the SSI rates among patients who did and did not receive any bowel prep was not significantly different (no bowel prep 10.6% vs. bowel prep 8.2%, p = 0.15). Among 15 cases that reported fecal contamination, the SSI rate was 63.6% in the 11 patients who did not receive oral antibiotics and 0% in the 4 cases that did receive oral antibiotics (p = 0.051).

Figure 1.

Bowel preparation clinical practices within Michigan prior to elective colon surgery. Interestingly, the vast majority of patients still receive a mechanical bowel prep prior to elective colon surgery.

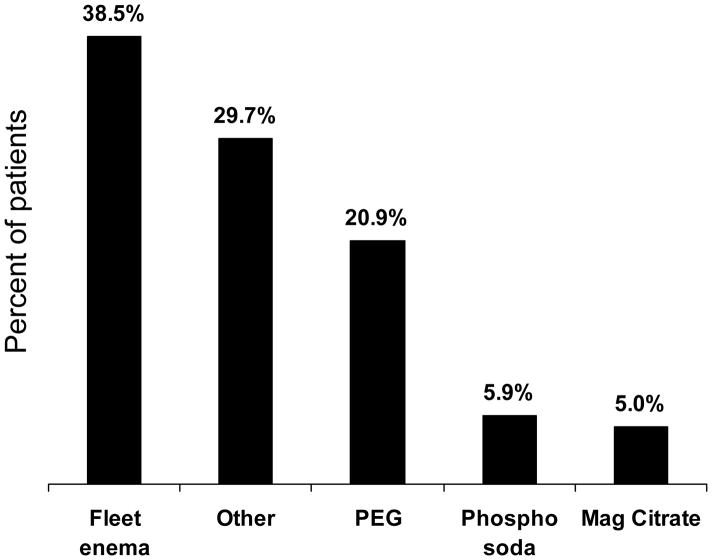

After excluding the 195 patients who did not receive any bowel preparation, the study group that remained included 1,553 patients who received a bowel preparation. Among these patients, 38.5% received only a Fleet™ Enema prior to elective colon surgery, 20.9% of patients received polyethylene glycol, 5.9% of patients received Phospho-Soda, 5% patients received magnesium citrate, and 29.7% of patients received another type of oral bowel preparation. (Figure 2) Among patients who received non-absorbable oral antibiotics, the following types of antibiotics were administered: neomycin and erythromycin 76.3%, neomycin alone 7.9%, erythromycin alone 2.6%, metronidazole alone 2.6%, clindamycin alone 2.6%, and other antibiotic 7.9%.

Figure 2.

Bowel preparation clinical practices within Michigan; the specific types of bowel preparation prescribed prior to elective colon surgery.

Upon comparing the two study groups (no oral antibiotic N = 915 and oral antibiotic at the time of bowel preparation N = 638), significant differences were noted among clinical and demographic characteristics. For example, the group that received no oral antibiotics was significantly more likely to be African-American, female, take steroids, and have pre-operative weight loss, diabetes, and sepsis. Further, this group had a lower BMI, have a lower case complexity (RVU), had a shorter operative duration, as well as differences in pre-operative lab values. (Table 1, unmatched cases) After propensity matching, there were 370 cases remaining in each group. In these matched cases there were no statistically significant differences between the demographic and clinical characteristics of the two groups (Table 1, matched cases). Other important clinical characteristics that were not noted to be significantly correlated with receiving pre-operative oral antibiotics included: cancer diagnosis, abdominal wound left open at the time of index operation, peri-operative parenteral antibiotic administration, and rates of laparoscopic colectomy.

Similarly, prophylactic antibiotics given 1hr before incision, intraoperative antibiotic redosing, and maintenance of normothermia were not statistically different between the unmatched and matched study groups. In the unmatched sample, the prophylactic antibiotic 1hr rates were 92.6% and 93.8% (p = 0.211); the redose rate were 3.0% and 2.7% (p=0.474); and the 36°C normothermia rates were 96.1% and 96.4% (p = 0.436). In the matched sample, the prophylactic antibiotic 1hr rates were 95.0% and 96.5% (p =0.201); the redose rate were 2.2% and 1.6% (p=0.497); and the 36°C normothermia rates were 94.6% and 96.3% (p = 0.184).

Using the propensity matched cohort, we then compared the incidence of surgical site infections between the two study groups. The group that received oral non-absorbable antibiotics had significantly lower rates of superficial surgical site infection (2.4% versus 8.6%, p < 0.001), organ space infections (1.6% versus 4.3%, p = 0.049) and overall SSI (4.6% versus 12.4%, p < 0.001). (Figures 3 and 4) There was no significant difference in the rate of deep incisional surgical site infections (0.80% versus 0.50%, p = 0.69). Further, the study group that received oral antibiotics had a lower rate of prolonged ileus, (3.8% versus 8.9%, p = 0.006). No significant difference in rates of C. difficile colitis were noted between the two groups (1.9% versus 3.0%, p = 0.24).

Figure 3.

Surgical site infection rates among propensity matched cohorts of patients who either did or did not receive oral non-absorbable antibiotics at the time of mechanical bowel preparation prior to elective colon surgery. Patients that received oral antibiotics were observed to have significantly lower rates of organ space infections, superficial surgical site infection, and overall surgical site infection rates.

Figure 4.

Surgical site infection rates among propensity matched cohorts of patients who either did or did not receive oral non-absorbable antibiotics at the time of mechanical bowel preparation prior to elective colon surgery. Patients that received oral antibiotics were observed to have significantly lower rates of prolonged ileus and overall surgical site infection. Importantly, patient to receive oral antibiotics did not have significantly higher rates of C. difficile colitis.

Discussion

More than 250,000 Americans undergo colectomy each year, and SSI rates following colectomy remain greater than 10%.27–30 Efforts to optimize the pre-operative preparation of patients prior to elective colectomy are critical. In this manuscript, we describe an effort to understand more deeply the practice of elective, standard colectomy in Michigan. We noted a strong association between the administration of oral non-absorbable antibiotics and low surgical site infection rates. We also noted that oral non-absorbable antibiotics were associated with lower rates of prolonged ileus, and did not seem to be associated with increased rates of C. difficile colitis.

The debate regarding optimal preparation of the patient for elective colon surgery spans numerous surgical generations. The first reports of bowel preparation prior to intestinal surgery appeared in the early 1950s. Following the seminal work of Nichols, Condon and Polk, mechanical bowel preparation with the addition of oral non-absorbable antibiotics became standard of care prior to elective colon surgery 1–5, 16–18 More recently, well-designed clinical trials have questioned the need for any kind of mechanical bowel preparation.6, 8–13, 21 Investigators have suggested that mechanical bowel preparation may be associated with increased rates of anastomotic leak, bacterial translocation, and electrolyte disturbances.10, 11 In addition, patients dislike the pre-operative bowel preparation.10, 13 As a result, current literature advises that pre-operative mechanical bowel preparation is unnecessary.6, 8–10, 12

We used the data collection infrastructure of the MSQC to get a new perspective on the need for bowel preparation prior to colonic surgery. Here we make a distinction between treatment “efficacy”, meaning what is shown to be useful within the academic confines of a randomized controlled trial, and “effectiveness”, meaning what actually works in a real world environment. The MSQC, consisting of 34 mostly community based hospitals in Michigan, provides insight about the latter. We found that, despite recent admonitions from the literature, almost 90% of surgeons in Michigan regularly prescribe a bowel preparation of some kind prior to colon surgery. When we looked deeper into the type of bowel prep used, we were surprised to learn that many surgeons had stopped adding oral antibiotics to the bowel prep regimen. Certainly there is no literature which would direct this change in practice. Possibly factors such as patient dislike for the side effects of oral antibiotics or a concern about predisposition to C. difficile colitis infection could have influenced surgeons to stop using the traditional Nichols (mechanical prep with oral antibiotics) prep. Whatever the reason, this evolving change in practice presented us with two large groups of roughly equal size to study the importance of oral antibiotics.

In order to study the two groups, we used a statistical approach known as propensity matching. This approach attempts to mitigate the selection bias that often plagues observational studies. Propensity matching allows for the creation of groups that are closely matched for all the important and known variables which could influence outcomes in colon surgery, except for the variable in question: oral antibiotics as part of the bowel prep. We further strengthened our study by prospectively defining and measuring variables which are usually not a part of studies of this type, including; the presence of ureteral stents, the occurrence of gross fecal spillage during surgery, whether or not a ureteral injury occurred, whether or not an epidural catheter was used, whether or not blood transfusions were administered during surgery, the duration of the operation itself, peri-operative glucose levels, and whether or not the wound was left open at the completion of the procedure. This was possible because prior to the study, the MSQC defined and added these variables to the standard ACS-NSQIP data set, and made them a routine part of the data collection process. We believe that including important variables of this type strengthens the conclusions reached from the propensity matching approach.

It is intuitive that a mechanical bowel preparation with oral non-absorbable antibiotics may reduce infectious complications following colon surgery. A mechanical bowel preparation alone does not reduce mucosa-associated flora.31 Conversely, a combination of oral non-absorbable antibiotics and intravenous antibiotics provides the greatest mucosa associated reduction in colony-forming units (1.8 × 102 compared to 3.4 × 107).31 Previous work has indicated the importance of both oral and intravenous antibiotics prior to elective colon surgery.32–34 Lewis, using an RCT design, evaluated the importance of oral metronidazole and neomycin as an addition to mechanical bowel preparation.14 In this study the single most important determinant of post operative wound infection was the presence of bacterial growth from the subcutaneous fat at the completion of the case. Patients having received oral antibiotics demonstrated one half the incidence of positive fat cultures when compared to those not having received oral antibiotics, and the former experienced significantly fewer wound infections as well, suggesting a cause and effect relationship.14 Although no such measurement was done in this observational study, we did carefully identify cases in which gross spillage of residual stool had occurred during the course of surgery. In these cases there were fewer post operative infections if the patients had received oral antibiotics as a part of the bowel prep. We suggest that this is because the bacterial load of the spilled material was significantly reduced when the patient had been treated with oral antibiotics. Along these same lines we noted a significantly reduced incidence of intra-abdominal abscess in patients treated with oral antibiotics. Again, it seems logical to conclude that some small amount of fecal spillage during anastomosis, which could evolve into an intra-abdominal abscess, was less likely to do so if the patient had been treated with oral antibiotics as part of the bowel preparation.

Our study is not a randomized trial, but we believe there is an important role for carefully done observational studies, which provide insight into “what actually works” in a community hospital setting as well. A randomized controlled trial remains the benchmark for efficacy studies for reasons familiar to all, but the design of the trial itself may lead to conclusions which are not exactly applicable to the local hospital setting. An RCT, for example, might be carried out in hospitals with a strong academic interest involving trainees, or larger more financially viable hospitals, or hospitals primarily located in affluent/poor environments, with relatively well/sick study subjects. These and many other factors could conceivably influence results. Our point is not that the RCT process is flawed, but only that results from the RCT should be complemented with observational studies, which we believe should be propensity matched, and which take place in a variety of hospital types and patient environments. This approach then provides for a different and possibly more representative population base on which to draw conclusions. The observational approach also takes into account practical problems associated with implementation. The most significant and effective antibiotic, identified as such during the course of an RCT, may not be effective if patients don’t like it’s taste, and wont reliably follow the physicians prescription. The collective information, including conclusions about efficacy, can then be blended with conclusions about effectiveness, in order to get a more complete view of the importance of any given intervention. In the specific case involving the importance of oral antibiotics, there have been several RCTs supporting the importance of oral antibiotics as part of the bowel prep in reducing post colectomy infectious complications, and we now provide a large community based observational study which supports these conclusions.3, 14–16, 32

There are important limitations of this work. Due to the observational nature of this study, we are unable to attribute causality between the administration of oral non-absorbable antibiotics and post-operative outcomes. A second important limitation is the potential for selection bias within the two study groups. The purpose of propensity matching is to address this bias; nonetheless the potential still exists for unmeasured confounders that could significantly influence the outcomes of this analysis. And finally, in an attempt to minimize the effect of case mix differences in our analysis, we have by design limited our study to a group of standard colectomy procedures, but not including rectal resection. How our findings might apply if rectal cases were included is not known. One might conjecture, however, that given the increased bacterial load in the rectal area, oral antibiotics might be even more effective in these circumstances.4, 16, 18, 22

In summary, this observational study, conducted at a state-wide level supports the effectiveness of adding oral antibiotics to a bowel preparation at the time of elective colectomy. The use of these antibiotics should reduce surgical site infection, prolonged ileus, and do not seem to be associated with increased risk of C. difficile colitis. Further studies must examine the efficacy of a strategy which does not include a bowel preparation at all, but when such studies are conducted they should pit the no preparation strategy itself to the gold standard existing now, which is mechanical preparation with the addition of oral antibiotics.

Acknowledgments

Support: MJE was supported by NIH – NIDDK (K08 DK0827508) and the American Surgical Association Foundation. DAC was supported by a grant from Blue Cross and Blue Shield of Michigan

References

- 1.Andina F, Allemann O. Disinfection of the colon in preparation for colonic and rectal surgery, following the principle of limited disinfection. Schweiz Med Wochenschr. 1950;80(45):1201–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Poth EJ. Intestinal antisepsis in surgery. J Am Med Assoc. 1953;153(17):1516–21. doi: 10.1001/jama.1953.02940340018007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohn I, Jr, Longacre AB. Ristocetin and ristocetin-neomycin for preoperative preparation of the colon. AMA Arch Surg. 1958;77(2):224–9. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.1958.01290020074014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Nichols RL, Broido P, Condon RE, et al. Effect of preoperative neomycin-erythromycin intestinal preparation on the incidence of infectious complications following colon surgery. Ann Surg. 1973;178(4):453–62. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197310000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Polk HC, Jr, Lopez-Mayor JF. Postoperative wound infection: a prospective study of determinant factors and prevention. Surgery. 1969;66(1):97–103. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Santos JC, Jr, Batista J, Sirimarco MT, et al. Prospective randomized trial of mechanical bowel preparation in patients undergoing elective colorectal surgery. Br J Surg. 1994;81(11):1673–6. doi: 10.1002/bjs.1800811139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Slim K, Flamein R, Brugere C. Preoperative bowel preparation--is it useful? J Chir (Paris) 2004;141(5):285–92. doi: 10.1016/s0021-7697(04)95335-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ram E, Sherman Y, Weil R, et al. Is mechanical bowel preparation mandatory for elective colon surgery? A prospective randomized study. Arch Surg. 2005;140(3):285–8. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.140.3.285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Contant CM, Hop WC, van’t Sant HP, et al. Mechanical bowel preparation for elective colorectal surgery: a multicentre randomised trial. Lancet. 2007;370(9605):2112–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(07)61905-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jung B, Pahlman L, Nystrom PO, Nilsson E. Multicentre randomized clinical trial of mechanical bowel preparation in elective colonic resection. Br J Surg. 2007;94(6):689–95. doi: 10.1002/bjs.5816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Slim K, Vicaut E, Launay-Savary MV, et al. Updated systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials on the role of mechanical bowel preparation before colorectal surgery. Ann Surg. 2009;249(2):203–9. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318193425a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valantas MR, Beck DE, Di Palma JA. Mechanical bowel preparation in the older surgical patient. Curr Surg. 2004;61(3):320–4. doi: 10.1016/j.cursur.2003.12.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jung B, Lannerstad O, Pahlman L, et al. Preoperative mechanical preparation of the colon: the patient’s experience. BMC Surg. 2007;7:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2482-7-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lewis RT. Oral versus systemic antibiotic prophylaxis in elective colon surgery: a randomized study and meta-analysis send a message from the 1990s. Can J Surg. 2002;45(3):173–80. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lewis RT, Goodall RG, Marien B, et al. Is neomycin necessary for bowel preparation in surgery of the colon? Oral neomycin plus erythromycin versus erythromycin-metronidazole. Can J Surg. 1989;32(4):265–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bartlett JG, Condon RE, Gorbach SL, et al. Veterans Administration Cooperative Study on Bowel Preparation for Elective Colorectal Operations: impact of oral antibiotic regimen on colonic flora, wound irrigation cultures and bacteriology of septic complications. Ann Surg. 1978;188(2):249–54. doi: 10.1097/00000658-197808000-00020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nichols RL, Condon RE. Antibiotic preparation of the colon: failure of commonly used regimens. Surg Clin North Am. 1971;51(1):223–31. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)39343-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nichols RL, Condon RE. Preoperative preparation of the colon. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1971;132(2):323–37. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nichols RL, Holmes JW. Prophylaxis in bowel surgery. Curr Clin Top Infect Dis. 1995;15:76–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Campbell D, Englesbe M. Don’t Give up on Bowel Preps Yet. Annals of Surgery. 2010 doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181e48d2f. In Press. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wren SM, Ahmed N, Jamal A, Safadi BY. Preoperative oral antibiotics in colorectal surgery increase the rate of Clostridium difficile colitis. Arch Surg. 2005;140(8):752–6. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.140.8.752. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hayashi MS, Wilson SE. Is there a current role for preoperative non-absorbable oral antimicrobial agents for prophylaxis of infection after colorectal surgery? Surg Infect (Larchmt) 2009;10(3):285–8. doi: 10.1089/sur.2008.9958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Campbell DA, Jr, Kubus JJ, Henke PK, et al. The Michigan Surgical Quality Collaborative: a legacy of Shukri Khuri. Am J Surg. 2009;198(5 Suppl):S49–55. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2009.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Campbell DA, Englesbe MJ, Kubus JJ, et al. Accelerating the Pace of Surgical Quality Improvement: The Power of Hospital Collaboration. Archives of Surgery. 2009 doi: 10.1001/archsurg.2010.220. In review. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.American College of Surgeons. National Surgical Quality Improvement Program. 2006 July 19; website ( www.acsnsqip). Data collection form.

- 26.Hamilton BH, Ko CY, Richards K, Hall BL. Missing data in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program are not missing at random: implications and potential impact on quality assessments. J Am Coll Surg. 210(2):125–139. e2. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2009.10.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.American College of Surgeons. National Surgical Quality Improvement Program Semi-annual report. 2009 https://acsnsqip.org/login/default.aspx.

- 28.Arriaga AF, Lancaster RT, Berry WR, et al. The Better Colectomy Project: Association of Evidence-Based Best-Practice Adherence Rates to Outcomes in Colorectal Surgery. Ann Surg. 2009 doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3181b672bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Csikesz NG, Nguyen LN, Tseng JF, Shah SA. Nationwide volume and mortality after elective surgery in cirrhotic patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2009;208(1):96–103. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2008.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Finlayson EV, Goodney PP, Birkmeyer JD. Hospital volume and operative mortality in cancer surgery: a national study. Arch Surg. 2003;138(7):721–5. doi: 10.1001/archsurg.138.7.721. discussion 726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Smith MB, Goradia VK, Holmes JW, et al. Suppression of the human mucosal-related colonic microflora with prophylactic parenteral and/or oral antibiotics. World J Surg. 1990;14(5):636–41. doi: 10.1007/BF01658812. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Coppa GF, Eng K. Factors involved in antibiotic selection in elective colon and rectal surgery. Surgery. 1988;104(5):853–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Coppa GF, Eng K, Gouge TH, et al. Parenteral and oral antibiotics in elective colon and rectal surgery. A prospective, randomized trial. Am J Surg. 1983;145(1):62–5. doi: 10.1016/0002-9610(83)90167-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Schoetz DJ, Jr, Roberts PL, Murray JJ, et al. Addition of parenteral cefoxitin to regimen of oral antibiotics for elective colorectal operations. A randomized prospective study. Ann Surg. 1990;212(2):209–12. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199008000-00016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]