Summary of Recent Advances

Human regulatory T cells (Tregs) play a critical role in preventing autoimmunity, and their failure contributes to autoimmune diseases. In recent years, our understanding of human Tregs has been greatly enhanced by improvements in the definition and isolation of pure human Tregs, as well as by the discovery of phenotypically and functionally distinct human Treg subsets. This progress has also yielded a better understanding of the mechanisms of human Treg suppression and the role of human Tregs in autoimmune diseases. An unexpected discovery is that human Tregs have considerable plasticity that allows them to produce the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-17 under certain conditions. These recent advances highlight the importance of studying the roles of both mouse and human Tregs in autoimmunity.

Introduction

Human regulatory T cells (Tregs) were first isolated from peripheral blood and characterized as CD4+CD25high T cells by several groups in 2001 [1–6]. We now know that these cells play a critical role in preventing autoimmune diseases by suppressing self-reactive T cells – which are present in all healthy individuals – through incompletely understood mechanisms that involve cell-contact and secretion of inhibitory cytokines [7]. Tregs’ impressive suppressive ability extends not only to other CD4+ T cells, but also to suppression of proliferation, activation, and cytokine production by CD8+ T cells, B cells, antigen-presenting cells (APCs), and natural killer cells [8]. The transcription factor forkhead box P3 (FoxP3) is the canonical, specific marker for human Tregs and is thought to serve as the “master regulator” in charge of Treg development and function [8–10]. In fact, mutations in FoxP3 lead to an absence of Tregs, which in turn results in the severe, multi-organ autoimmunity syndrome IPEX (immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, X-linked syndrome) [11]. It should be noted that other types of suppressive regulatory T cells have been described, including peripherally induced Tregs, Tr1, Th3, natural killer T cells, and certain CD8+ cells. These cells gain their suppressive abilities in the periphery, in response to certain cytokines or stimulation conditions. In contrast, human FoxP3+ natural Tregs develop their specialized suppressive abilities centrally in the thymus [12]. These human natural Tregs will be the focus of this review.

In addition to rare Mendelian genetic diseases such as IPEX, it has become increasingly clear that Tregs are of tremendous importance to the pathogenesis of common human diseases. Defects in the in vitro suppressive function of Tregs occur in patients with numerous autoimmune diseases, including relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis (RRMS), type 1 diabetes (T1D), psoriasis, myasthenia gravis, and rheumatoid arthritis (RA) [7]. Moreover, Tregs play increasingly recognized roles in a wide variety of human diseases that involve inflammation, notably cancers and infectious diseases [13,14]. In addition, infusion and pharmacological modulation of Tregs have been proposed as immune therapies for autoimmune diseases, cancer, infectious diseases, and for achieving tolerance to transplanted organs [8].

Although Tregs are studied most extensively in mice, Tregs of mice and humans exhibit many fundamental differences. First, there are differences in FoxP3 expression, including alternatively spliced FoxP3 isoforms with distinct functions present in humans but not mice and the expression of low levels of FoxP3 in CD4+CD25− cells following T-cell receptor (TCR) activation in humans but not mice [9,10,15–18]. Second, mouse models of autoimmune diseases are well known to differ from their human counterparts. Third, whereas mouse Treg isolation typically utilizes FoxP3-GFP reporter mice to take advantage of the specificity of FoxP3 as a Treg marker, human Treg isolation from blood must rely on cell-surface characteristics of Tregs. Fourth, human Tregs exhibit greater heterogeneity of phenotype and suppressive function than mouse Tregs, such that human Tregs are now generally divided into phenotypically and functionally distinct subsets for experimentation [19–21]. These key differences dictate that future Treg and autoimmune disease research must be conducted in human systems as well as in mouse models.

In this review, we focus on recent advances in our understanding of how to define and isolate homogenous FoxP3+ human Tregs, phenotypically and functionally distinct Treg subsets, Treg plasticity, mechanisms of Treg suppression, the role of human Tregs in autoimmune diseases, and conclude with remarks about several promising avenues for future human Treg research.

Isolation of Homogenous FoxP3+ Suppressive Human Tregs

In mice, isolation of homogenous FoxP3+ Tregs can be achieved quite simply by using FoxP3-GFP reporter mice or by sorting CD4+CD25+ cells from immunologically naïve mice [8]. In humans, isolating a viable population of homogenous FoxP3+ Tregs from peripheral blood has been considerably more challenging for several reasons [7]. First, only cell surface markers can be used because of FoxP3’s intracellular location and the inability to use a GFP-tagged FoxP3. Second, the use of CD25 for Treg identification is inadequate because human peripheral blood comes from an outbred population with exposure to infectious pathogens. CD25 is upregulated following activation in human conventional CD4+ T cells, with the result that there is no clear boundary between Tregs and activated conventional CD4+ cells and only the cells with the highest 1–2% of CD25 expression can be confidently considered Tregs [2]. Third, the use of this strict CD25high criterion for Treg isolation would isolate only CD45RO+ Tregs and prohibit studying the recently identified CD25+CD127lowCD45RA+FoxP3+ Treg subset known as naïve Tregs (discussed below) [19].

An improvement in our ability to purify human FoxP3+ Tregs came with the discovery that FoxP3 expression and suppressive function are inversely correlated with CD127 expression [22,23]. Combined use of the markers CD25high and CD127low improves the purity of isolated human Tregs – with purify defined by % of FoxP3+ cells – to ~98%. Nevertheless, this method of isolation fails to achieve satisfactory discrimination of Tregs from activated conventional CD4+ T cells, which in response to activation upregulate CD25 and downregulate CD127 [9,19,24]. Moreover, the definition of human Treg purity as the % of FoxP3+ cells is imperfect because of contamination by non-suppressive, pro-inflammatory, FoxP3low cells in peripheral human blood that are probably activated conventional CD4+ cells [17–19].

Instead, it seems that a better way to define purity of suppressive human Tregs is long-term stability of FoxP3 expression, which is related to certain epigenetic modifications (discussed below). Transiently FoxP3-expressing activated conventional T cells are non-suppressive and produce pro-inflammatory cytokines, but forcing activated conventional T cells to sustain high levels of FoxP3 expression is sufficient to endow them with suppressive ability [10,18,25]. In addition, stabile FoxP3 expression appears to be necessary for suppressive function, since forcing Tregs to lose their stabile FoxP3 expression abrogates suppression [26,27].

Interestingly, recent studies of the epigenetic regulation of human FoxP3 expression have identified epigenetic marks that more specifically discriminate human Tregs from activated FoxP3low conventional T cells and FoxP3+ TGF-beta-induced Tregs than do FoxP3 mRNA or protein expression [28,29]. To date, the human FoxP3 locus has been found to contain four conserved, non-coding regions that are sites of epigenetic regulation of FoxP3 transcription [28,29]. Of these regions, a CpG-rich intronic enhancer region known as the Treg-specific demethylated region (TSDR) contains the most strikingly Treg-specific pattern of CpG methylation. In both mouse and human, the TSDR is completely demethylated in Tregs, but is fully methylated in resting conventional T cells, FoxP3low activated conventional T cells, and FoxP3+ TGF-beta-induced Tregs [27,30,31]. The current model is that the methylation status of the TSDR enhancer determines the long-term stability of FoxP3 transciption, whereas the other cis-acting elements at the FoxP3 locus are responsible for the instantaneous level of FoxP3 transcription [29,32,33]. Thus, the methylated state of the TSDR in activated conventional T cells and TGF-beta-induced Tregs allows these cells to transiently express FoxP3. In contrast, the demethylated state of the TSDR in human Tregs allows them to be the only cells that generally exhibit long-term stability of FoxP3 expression. Indeed, one study in the mouse showed that forced CpG demethylation using the DNA methyltransferase inhibitor 5-aza-2-deoxycytidine causes conventional T cells to gain stable FoxP3 expression and suppressive ability [34]. Testing the methylation status of the TSDR is the new gold standard for demonstrating stabile FoxP3 expression and should prove quite useful in future work aiming to define cell-surface markers to isolate pure, stabile FoxP3+ human Tregs.

Phenotypically and Functionally Distinct Human Treg Subsets

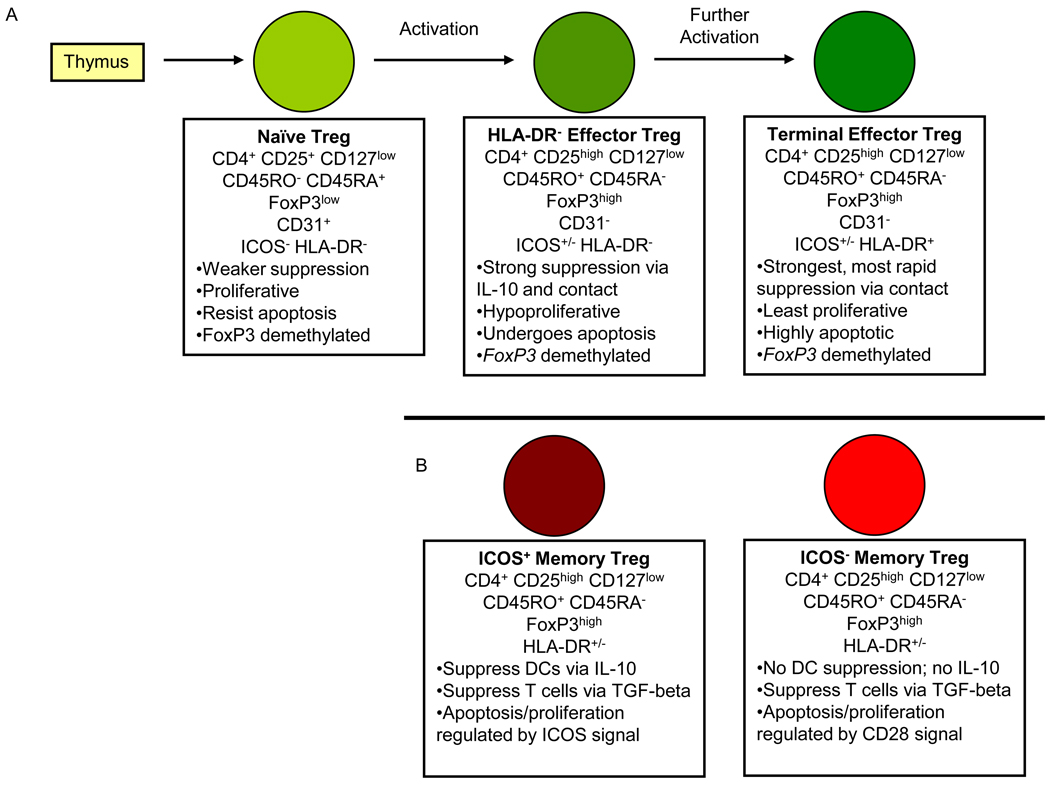

Human Tregs – even those that are pure on the basis on suppressive ability, stabile FoxP3 expression, and epigenetic marks – nevertheless exhibit phenotypic and functional heterogeneity that is not seen in mouse Tregs. Recent studies have succeeded in dividing human Tregs into more homogenous subsets on the basis of cell-surface marker expression (Figure 1). Dividing human Tregs into distinct subsets has been fruitful for improving our understanding of basic human Treg biology and will likely be critical to future studies of the role of human Tregs in autoimmune disease.

Figure 1. Human Treg subsets and differentiation.

The current understanding of human Treg subsets and differentiation is illustrated, with key phenotypic and functional features listed below each type of Treg. A) The human thymus produces naïve Tregs that travel to the periphery where they are activated by antigenic stimulation. Following activation, naïve Tregs proliferate and differentiate into HLA-DR− effector Tregs, which have greater suppressive ability but are limited in proliferation ability and survival. Effector Tregs can further differentiate into HLA-DR+ terminal effector Tregs, which have the strongest, most rapid suppressive ability but also are highly apoptotic. B) In addition, human memory Tregs can be divided on the basis of ICOS expression into two subsets that differ in mechanism of suppression and signaling pathway involved in regulation of survival and proliferation. There does not appear to be any relationship between HLA-DR and ICOS expression in human Tregs. DC, dendritic cell; ICOS, inducible T cell co-stimulator; IL, interleukin; HLA-DR, human leukocyte antigen DR; TGF, transforming growth factor; CD, cluster of differentiation.

The most common approach to defining human Treg subsets is based on combining CD25 and CD127 expression with expression of the classic markers for memory (CD45RO) and naïve (CD45RA) conventional T cells [19,35]. This approach yields two suppressive FoxP3+ Treg populations that are distinct in phenotype and function: CD25highCD127lowCD45RO+FoxP3+ ‘memory Tregs’ and CD25+CD127lowCD45RA+FoxP3+ ‘naïve Tregs’ [19,35]. Memory Tregs are essentially a purified version of the human Tregs that have been studied since 2001. They express the highest CD25 and FoxP3 and other markers of activated T cells, exhibit the strongest suppression, and exhibit hyporesponsiveness and undergo apoptosis in response to TCR stimulation [1–6,19,36,37]. The term ‘memory’ may be somewhat misleading for memory Tregs because, in contrast to conventional memory T cells that are long-lived and allow the individual’s immune system to ‘remember’ previous pathogens upon re-exposure, it is not known if human memory Tregs are long-lived in vivo or if they display immunological memory.

Naïve Tregs, in contrast to memory Tregs, express CD25 and FoxP3 at lower levels, exhibit weaker suppression, exhibit substantial proliferation and resistance to apoptosis in response to TCR stimulation, and do not appear to be present in the mouse [19,35]. In further contrast to memory Tregs, naïve Tregs express CD31, the marker for recent thymic emigrant cells [19,20,38]. When human naïve Tregs were transferred into immunodeficient NOD/Shi-scid IL2rg−/− (NOG) mice, they became activated, proliferated, and differentiated into memory Tregs [19]. Combined with the observation that naïve Tregs are virtually the exclusive type of FoxP3+ cell type found in umbilical cord blood [19,38], these observations suggest that naïve Tregs are the predominant, perhaps the only, subset of Tregs produced by the human thymus and that only once they emigrate from the thymus and become activated in the periphery can naïve Tregs proliferate and convert into memory Tregs. Compared to naïve Tregs, human memory Tregs are more activated and more fully differentiated in their ability to perform strong suppression (Figure 1). A prospective study of Treg phenotype from human infants has provided considerable evidence in support of this model by demonstrating naïve Treg conversion into memory Tregs starting around age 18 months [39]. This study also identified an intriguing switch in human Treg homing receptor expression between infants (mostly gut homing receptor α4β7) and adults (mostly extra-intestinal homing receptor CCR4), which suggests that infant naïve Tregs may experience antigenic stimulation and differentiate into memory Tregs primarily based on the gut microbiome present in infancy [39].

Even within the human memory Treg subset there remains heterogeneity, since memory Tregs have been further subdivided into phenotypically and functionally distinct subpopulations on the basis of HLA-DR and ICOS expression (Figure 1) [20,21]. HLA-DR+ memory Tregs were shown to be a terminally differentiated derivative of HLA-DR− memory Tregs because in vitro activation of HLA-DR− memory Tregs converts them into HLA-DR+ memory Tregs and because HLA-DR+ memory Tregs exhibit more rapid and stronger suppression of responder T cell proliferation and cytokine secretion than HLA-DR− memory Tregs [21,36]. Because of these findings, we refer to the HLA-DR− and HLA-DR+ subsets as effector Tregs and terminal effector Tregs respectively (Figure 1A). ICOS+ memory Tregs were shown to suppress dendritic cell CD86 upregulation via IL-10 and responder T cells via TGF-beta; in contrast, ICOS− memory Tregs can only suppress responder T cells via TGF-beta [20]. In addition, ICOS+ and ICOS− memory Tregs exhibit differences in the roles of CD28 and ICOS signaling in regulation of proliferation and apoptosis [20] (Figure 1B). It is worth noting that ICOS and HLA-DR expression are not correlated in human memory Tregs.

Human Treg Plasticity

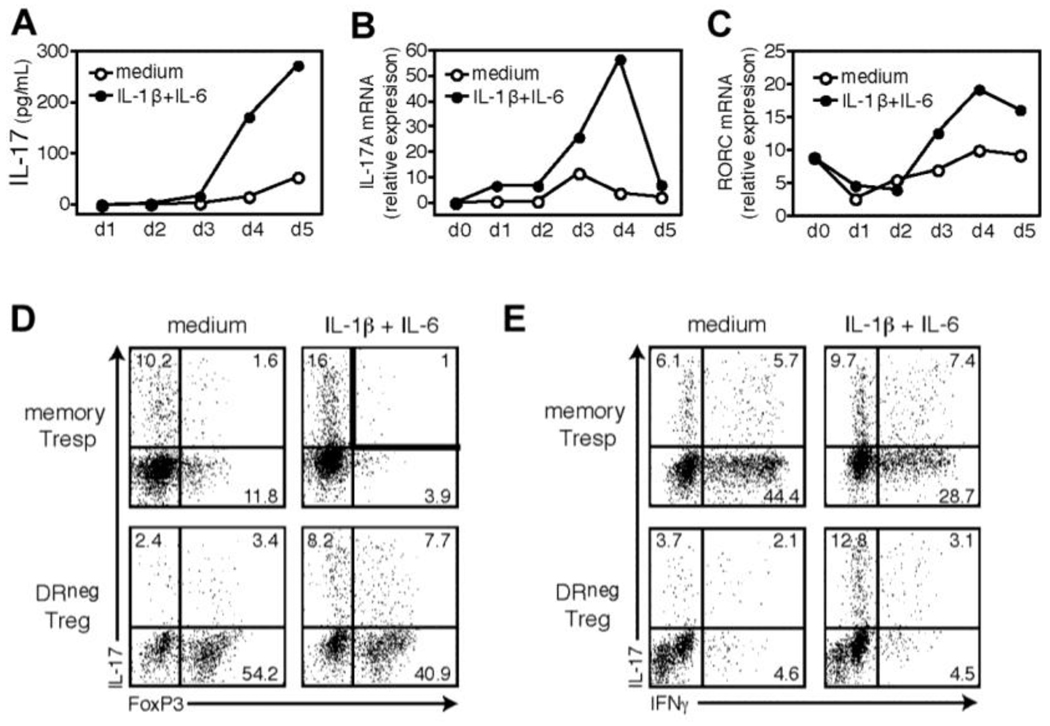

Given that in vitro expansion and clinical administration of human Tregs is progressing toward clinical applications [40], there is great interest in recent findings that human Tregs can exhibit functional plasticity beyond converting between various suppressive Treg subsets (discussed above). One type of functional plasticity that was observed in naïve and especially in memory human Tregs is the loss FoxP3 expression and suppressive ability following long-term in vitro TCR and CD28 stimulation of the sort that would be necessary to expand Tregs for clinical applications [27]. This loss of FoxP3 expression and suppressive ability is accompanied by increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines IL-2 and IFN-gamma [27]. Several other studies have shown that FoxP3+ human Tregs can produce the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-17 under certain conditions, typically when they are strongly activated in the presence of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1-beta and IL-6 (Figure 2) [19,41–43]. In addition to raising concern about the consequences of human Treg plasticity for clinical applications of in vitro expanded Tregs, human Treg plasticity may play roles in the dysfunction of Tregs in autoimmune diseases.

Figure 2. Human FoxP3+ HLA-DR− Effector Tregs have the plasticity to produce the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-17 in the presence of IL-1-beta and IL-6.

FACS-sorted human HLA-DR− effector Tregs (104 cells/well) were stimulated in serum-free X-Vivo medium for five days with plate-bound CD3, soluble CD28, and IL-2 in the presence of exogenous IL-1-beta and IL-6. Supernatants and cells were harvested at 24-hour intervals and analyzed for IL-17 by ELISA (A) or mRNA expression of IL-17A (B) and RORC (C) by real-time polymerase chain reaction. Data are representative of two independent experiments. At the end of five days of culture, cells were pulsed for four hours with PMA/ionomycin and GolgiStop, and stained for intracellular IL-17 versus FoxP3 (D) or IFN-gamma (E). Data are representative of four independent experiments. These HLA-DR− effector Tregs were also suppressive in a typical in vitro co-culture suppression assay (not shown). IL, interleukin; HLA-DR, human leukocyte antigen DR; CD, cluster of differentiation; FACS, fluorescence-activated cell sorting; ELISA, enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay; RORC, RAR-related orphan receptor C; PMA, phorbol myristate acetate; IFN, interferon. This research was originally published in Blood. Beriou G, Costantino CM, Ashley CW, Yang L, Kuchroo VK, Baecher-Allan C, Hafler DA: IL-17-producing human peripheral regulatory T cells retain suppressive function. Blood 2009, 113:4240–4249. © the American Society of Hematology.

Mechanisms of Human Treg Suppression

Human Treg suppression of conventional responder T cells is studied in vitro and occurs through multiple incompletely understood mechanisms that involve direct cell-contact and secretion of inhibitory cytokines [7]. Human Treg suppression requires TCR stimulation and costimulation (usually of CD28 or CD2), which can be performed in the presence of APCs or in an APC-free system [2,7]. The specific mechanisms of human Treg suppression – which are similar but not identical to mouse Treg suppressive mechanisms – include granzymes A and B [36,44], CD95–CD95L [45], IL-10 [20], and adenosine [46]. Interestingly, if TCR and co-stimulatory molecule stimulation is too strong or the suppression assay is supplemeted with pro-inflammatory cytokines, an abrogation of suppressive ability is observed, likely due to both decreased Treg suppressive function and increased responder T cell resistance to suppression [2,7,41]. It can be postulated that pro-inflammatory, strongly-activating conditions that are able to abrogate human Treg suppression would be appropriately present to allow conventional T cells to fight infections unimpeded by Treg suppression, but would also be inappropriately present in autoimmune diseases.

Impairment of Human Treg Suppression in Autoimmune Diseases

Defective in vitro suppressive function of human Tregs appears to be a common feature of autoimmune diseases [7,47–50]. Here we will briefly discuss studies of Tregs from RRMS patients. Initial studies demonstrated that there exists a CD25hi Treg suppression defect in RRMS patients and that this defect is the result of Treg dysfunction and not of responder T cell resistance to suppression [51,52]. In addition, RRMS patient CD25high Tregs might be functionally deficient due to decreased FoxP3 mRNA and protein expression [53]. Interestingly, responder T cell resistance to Treg suppression may be present in other autoimmune diseases such as T1D and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) [54–57].

Yet, most studies of Tregs from autoimmune disease patients have been conducted using impure and/or heterogenous human Treg populations defined only on the basis of CD25high expression. It is likely that studies with such a heterogenous Treg population have obscured findings that are only present in one subset of Tregs and have confused FoxP3-expressing activated conventional T cells with true Tregs. Thus, it is essential for future work to examine functionally distinct Treg subsets separately in autoimmune disease patient samples. Indeed, recent work has shown disease-specific changes in human Treg subsets. One study demonstrated that sarcoidosis patients with active disease have an increased ratio of memory to naïve Tregs compared to healthy controls, whereas patients with active SLE have a decreased ratio of memory to naïve Tregs [19]. Similarly, several groups have reported that RRMS peripheral blood contains a reduced frequency of naïve Tregs and that the suppressive ability of these naïve Tregs is impaired in RRMS [50,53,58]. In addition, we have found that effector Tregs and terminal effector Tregs from MS patients exhibit temporally distinct deficiencies in suppression that are obscured by examination of the bulk memory Treg population (CM Baecher-Allan et al., unpublished) [53,59]. Thus, Tregs exhibit multiple differences from healthy controls that are likely to play roles in the complex pathogenesis of RRMS; these include reduced thymic output of naïve Tregs, impaired naïve Treg suppression, and distinct impairments in at least two subsets of memory Tregs.

Concluding Remarks

Since the first identification of human Tregs in 2001, there has been considerable progress in our understanding of human Tregs and their role in autoimmune disease pathogenesis. Our ability to define and isolate pure Tregs has dramatically improved, as has our aptitude at addressing the heterogeneity of human Tregs by dividing Tregs into phenotypically and functionally distinct subsets. Enabled by the progress in purifying and subdividing Tregs, there has also been progress in defining the mechanisms of human Treg suppression and the role of human Tregs in autoimmune diseases. A surprise along the way has been the discovery of Treg plasticity and the ability of Tregs to produce the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-17 under certain conditions.

Clinical trials of cellular therapy with in vitro expanded Tregs are already underway in patients with severe graft-versus-host disease [60]. But, in order for pharmacological modulation or infusion of in vitro expanded human Tregs to achieve its therapeutic promise for human autoimmune diseases, a critical area of future research must be further characterization of Treg subsets in order to determine which should be used for cellular therapy and how their poorly-understood suppressive abilities can be targeted pharmacologically. Additionally, future research must achieve a clear understanding of human Treg plasticity in order to avoid loss of suppression and conversion to a pro-inflammatory phenotype after Tregs are infused into autoimmune disease patients. Other important topics for future investigation include investigations of a more specific human Treg cell-surface marker, elucidation of the mechanisms of suppression and the distinct in vivo roles of various human Treg subsets, and addressing the relevance of in vitro suppression assays to in vivo function of human Tregs using mouse models with humanized immune systems.

Future research also must clarify the roles of human Treg dysfunction in autoimmune disease pathogenesis. A promising area of future research in this regard is based on the observation that many single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) genetically associated with human autoimmune diseases by genome-wide association studies (GWAS) are known to be involved in Treg function. These include CTLA-4, PTPN22, IL-2, CD25, CD127, IL-10, and CD58 [61,62]. In fact, several recent studies have already linked autoimmune-associated SNPs to phenotypic and functional human Treg data [63–65]. With the recent identification of the genome-wide target genes of human FoxP3 [66], future research should also address the hypothesis that autoimmune disease associated SNPs may disrupt FoxP3-regulated genes and thereby contribute to the Treg dysfunction observed in autoimmune diseases.

Acknowledgements

DAH is supported by National Institutes of Health Grants P01 AI045757, U19 AI046130, U19 AI070352, and P01 AI039671. D.A.H. is also supported by Jacob Javits Merit Award NS2427 from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. GLC is supported by a Howard Hughes Medical Institute Research Training Fellowship for Medical Students.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Gregory L. Cvetanovich, Harvard Medical School, 170 Brookline Ave. #919, Boston, MA 02215, Gregory_cvetanovich@hms.harvard.edu

David A. Hafler, Dept of Neurology, PO Box 208018. 15 York St, New Haven, CT 06520-8018, David.hafler@yale.edu

References

- 1.Stephens LA, Mottet C, Mason D, Powrie F. Human CD4(+)CD25(+) thymocytes and peripheral T cells have immune suppressive activity in vitro. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:1247–1254. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200104)31:4<1247::aid-immu1247>3.0.co;2-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baecher-Allan C, Brown JA, Freeman GJ, Hafler DA. CD4+CD25high regulatory cells in human peripheral blood. J Immunol. 2001;167:1245–1253. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.167.3.1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Dieckmann D, Plottner H, Berchtold S, Berger T, Schuler G. Ex vivo isolation and characterization of CD4(+)CD25(+) T cells with regulatory properties from human blood. J Exp Med. 2001;193:1303–1310. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.11.1303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taams LS, Smith J, Rustin MH, Salmon M, Poulter LW, Akbar AN. Human anergic/suppressive CD4(+)CD25(+) T cells: a highly differentiated and apoptosis-prone population. Eur J Immunol. 2001;31:1122–1131. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200104)31:4<1122::aid-immu1122>3.0.co;2-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jonuleit H, Schmitt E, Stassen M, Tuettenberg A, Knop J, Enk AH. Identification and functional characterization of human CD4(+)CD25(+) T cells with regulatory properties isolated from peripheral blood. J Exp Med. 2001;193:1285–1294. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.11.1285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Levings MK, Sangregorio R, Roncarolo MG. Human cd25(+)cd4(+) t regulatory cells suppress naive and memory T cell proliferation and can be expanded in vitro without loss of function. J Exp Med. 2001;193:1295–1302. doi: 10.1084/jem.193.11.1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Costantino CM, Baecher-Allan CM, Hafler DA. Human regulatory T cells and autoimmunity. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:921–924. doi: 10.1002/eji.200738104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sakaguchi S, Yamaguchi T, Nomura T, Ono M. Regulatory T cells and immune tolerance. Cell. 2008;133:775–787. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yagi H, Nomura T, Nakamura K, Yamazaki S, Kitawaki T, Hori S, Maeda M, Onodera M, Uchiyama T, Fujii S, et al. Crucial role of FOXP3 in the development and function of human CD25+CD4+ regulatory T cells. Int Immunol. 2004;16:1643–1656. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxh165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aarts-Riemens T, Emmelot ME, Verdonck LF, Mutis T. Forced overexpression of either of the two common human Foxp3 isoforms can induce regulatory T cells from CD4(+)CD25(−) cells. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:1381–1390. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gambineri E, Torgerson TR, Ochs HD. Immune dysregulation, polyendocrinopathy, enteropathy, and X-linked inheritance (IPEX), a syndrome of systemic autoimmunity caused by mutations of FOXP3, a critical regulator of T-cell homeostasis. Curr Opin Rheumatol. 2003;15:430–435. doi: 10.1097/00002281-200307000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sakaguchi S, Miyara M, Costantino CM, Hafler DA. FOXP3(+) regulatory T cells in the human immune system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2010 doi: 10.1038/nri2785. advance online publication. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Belkaid Y, Rouse BT. Natural regulatory T cells in infectious disease. Nat Immunol. 2005;6:353–360. doi: 10.1038/ni1181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Curiel TJ. Tregs and rethinking cancer immunotherapy. J Clin Invest. 2007;117:1167–1174. doi: 10.1172/JCI31202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buckner JH, Ziegler SF. Functional analysis of FOXP3. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2008;1143:151–169. doi: 10.1196/annals.1443.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Du J, Huang C, Zhou B, Ziegler SF. Isoform-specific inhibition of ROR alpha-mediated transcriptional activation by human FOXP3. J Immunol. 2008;180:4785–4792. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.7.4785. This paper demonstrated that human FoxP3 isoforms have at least one functional difference, namely that full-length FoxP3 interacts with and inhibits ROR-alpha mediated transcriptional activation but that the FoxP3 isoform lacking exon 2 does not have these abilities. Since ROR-alpha plays a role in Th17 cells, these findings highlight the close relationship that exists between Tregs and Th17 cells.

- 17.Gavin MA, Torgerson TR, Houston E, DeRoos P, Ho WY, Stray-Pedersen A, Ocheltree EL, Greenberg PD, Ochs HD, Rudensky AY. Single-cell analysis of normal and FOXP3− mutant human T cells: FOXP3 expression without regulatory T cell development. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:6659–6664. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0509484103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Walker MR, Kasprowicz DJ, Gersuk VH, Benard A, Van Landeghen M, Buckner JH, Ziegler SF. Induction of FoxP3 and acquisition of T regulatory activity by stimulated human CD4+CD25− T cells. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1437–1443. doi: 10.1172/JCI19441. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Miyara M, Yoshioka Y, Kitoh A, Shima T, Wing K, Niwa A, Parizot C, Taflin C, Heike T, Valeyre D, et al. Functional delineation and differentiation dynamics of human CD4+ T cells expressing the FoxP3 transcription factor. Immunity. 2009;30:899–911. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.03.019. This paper extensively characterizes the phenotype and function of the naïve and memory human FoxP3+ Treg subsets. It also conclusively demonstrates the differentiation of naïve Tregs into memory Tregs.

- 20. Ito T, Hanabuchi S, Wang YH, Park WR, Arima K, Bover L, Qin FX, Gilliet M, Liu YJ. Two functional subsets of FOXP3+ regulatory T cells in human thymus and periphery. Immunity. 2008;28:870–880. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2008.03.018. Similarly to Ref. [21], this paper demonstrates that human memory Tregs can be divided into phenotypically and functionally distinct subsets. In this case, memory Treg subsets are defined on the basis of ICOS expression and shown to differ in mechanism of suppression.

- 21.Baecher-Allan C, Wolf E, Hafler DA. MHC class II expression identifies functionally distinct human regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2006;176:4622–4631. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.176.8.4622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Liu W, Putnam AL, Xu-Yu Z, Szot GL, Lee MR, Zhu S, Gottlieb PA, Kapranov P, Gingeras TR, Fazekas de St Groth B, et al. CD127 expression inversely correlates with FoxP3 and suppressive function of human CD4+ T reg cells. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1701–1711. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Seddiki N, Santner-Nanan B, Martinson J, Zaunders J, Sasson S, Landay A, Solomon M, Selby W, Alexander SI, Nanan R, et al. Expression of interleukin (IL)-2 and IL-7 receptors discriminates between human regulatory and activated T cells. J Exp Med. 2006;203:1693–1700. doi: 10.1084/jem.20060468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Aerts NE, Dombrecht EJ, Ebo DG, Bridts CH, Stevens WJ, De Clerck LS. Activated T cells complicate the identification of regulatory T cells in rheumatoid arthritis. Cell Immunol. 2008;251:109–115. doi: 10.1016/j.cellimm.2008.04.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Allan SE, Alstad AN, Merindol N, Crellin NK, Amendola M, Bacchetta R, Naldini L, Roncarolo MG, Soudeyns H, Levings MK. Generation of potent and stable human CD4+ T regulatory cells by activation-independent expression of FOXP3. Mol Ther. 2008;16:194–202. doi: 10.1038/sj.mt.6300341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Allan SE, Song-Zhao GX, Abraham T, McMurchy AN, Levings MK. Inducible reprogramming of human T cells into Treg cells by a conditionally active form of FOXP3. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:3282–3289. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Hoffmann P, Boeld TJ, Eder R, Huehn J, Floess S, Wieczorek G, Olek S, Dietmaier W, Andreesen R, Edinger M. Loss of FOXP3 expression in natural human CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells upon repetitive in vitro stimulation. Eur J Immunol. 2009;39:1088–1097. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838904. This study highlights the plasticity of human Tregs by demonstrating that FoxP3 expression and suppressive ability is lost by naïve and especially memory Tregs following long-term in vitro stimulation of the sort that would be required for Treg expansion for clinical applications. The authors also showed that Treg plasticity following this stimulation includes production of pro-inflammatory cytokines.

- 28.Lal G, Bromberg JS. Epigenetic mechanisms of regulation of Foxp3 expression. Blood. 2009;114:3727–3735. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-05-219584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Huehn J, Polansky JK, Hamann A. Epigenetic control of FOXP3 expression: the key to a stable regulatory T-cell lineage? Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9:83–89. doi: 10.1038/nri2474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Floess S, Freyer J, Siewert C, Baron U, Olek S, Polansky J, Schlawe K, Chang HD, Bopp T, Schmitt E, et al. Epigenetic control of the foxp3 locus in regulatory T cells. PLoS Biol. 2007;5:e38. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0050038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baron U, Floess S, Wieczorek G, Baumann K, Grutzkau A, Dong J, Thiel A, Boeld TJ, Hoffmann P, Edinger M, et al. DNA demethylation in the human FOXP3 locus discriminates regulatory T cells from activated FOXP3(+) conventional T cells. Eur J Immunol. 2007;37:2378–2389. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737594. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Polansky JK, Kretschmer K, Freyer J, Floess S, Garbe A, Baron U, Olek S, Hamann A, von Boehmer H, Huehn J. DNA methylation controls Foxp3 gene expression. Eur J Immunol. 2008;38:1654–1663. doi: 10.1002/eji.200838105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nagar M, Vernitsky H, Cohen Y, Dominissini D, Berkun Y, Rechavi G, Amariglio N, Goldstein I. Epigenetic inheritance of DNA methylation limits activation-induced expression of FOXP3 in conventional human CD25−CD4+ T cells. Int Immunol. 2008;20:1041–1055. doi: 10.1093/intimm/dxn062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Lal G, Zhang N, van der Touw W, Ding Y, Ju W, Bottinger EP, Reid SP, Levy DE, Bromberg JS. Epigenetic regulation of Foxp3 expression in regulatory T cells by DNA methylation. J Immunol. 2009;182:259–273. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Valmori D, Merlo A, Souleimanian NE, Hesdorffer CS, Ayyoub M. A peripheral circulating compartment of natural naive CD4 Tregs. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1953–1962. doi: 10.1172/JCI23963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ashley CW, Baecher-Allan C. Cutting Edge: Responder T cells regulate human DR+ effector regulatory T cell activity via granzyme B. J Immunol. 2009;183:4843–4847. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0900845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Vukmanovic-Stejic M, Zhang Y, Cook JE, Fletcher JM, McQuaid A, Masters JE, Rustin MH, Taams LS, Beverley PC, Macallan DC, et al. Human CD4+ CD25hi Foxp3+ regulatory T cells are derived by rapid turnover of memory populations in vivo. J Clin Invest. 2006;116:2423–2433. doi: 10.1172/JCI28941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fritzsching B, Oberle N, Pauly E, Geffers R, Buer J, Poschl J, Krammer P, Linderkamp O, Suri-Payer E. Naive regulatory T cells: a novel subpopulation defined by resistance toward CD95L-mediated cell death. Blood. 2006;108:3371–3378. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-02-005660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Grindebacke H, Stenstad H, Quiding-Jarbrink M, Waldenstrom J, Adlerberth I, Wold AE, Rudin A. Dynamic development of homing receptor expression and memory cell differentiation of infant CD4+CD25high regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2009;183:4360–4370. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0901091. This study demonstrated that human infants have predominantly naïve Tregs at birth but that these naïve Tregs convert to memory Tregs starting at age 18 months. The authors also reported a switch in human Treg homing receptor expression between infants and adults that suggests infant naïve Tregs may preferentially migrate to the gut and differentiate into memory Tregs based on the gut antigens they encounter.

- 40.Riley JL, June CH, Blazar BR. Human T regulatory cell therapy: take a billion or so and call me in the morning. Immunity. 2009;30:656–665. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2009.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Beriou G, Costantino CM, Ashley CW, Yang L, Kuchroo VK, Baecher-Allan C, Hafler DA. IL-17-producing human peripheral regulatory T cells retain suppressive function. Blood. 2009;113:4240–4249. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-10-183251. See annotation to Ref. [43].

- 42. Koenen HJ, Smeets RL, Vink PM, van Rijssen E, Boots AM, Joosten I. Human CD25highFoxp3pos regulatory T cells differentiate into IL-17-producing cells. Blood. 2008;112:2340–2352. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-01-133967. See annotation to Ref. [43].

- 43. Ayyoub M, Deknuydt F, Raimbaud I, Dousset C, Leveque L, Bioley G, Valmori D. Human memory FOXP3+ Tregs secrete IL-17 ex vivo and constitutively express the T(H)17 lineage-specific transcription factor RORgamma t. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:8635–8640. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0900621106. Along with Ref. [41] and Ref. [42], this paper demonstrates that human Treg plasticity includes the ability to produce the pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-17 under certain conditions. These studies raise serious questions about whether such plasticity contributes to the dysfunciton of Tregs in autoimmune diseases and about how to promote Treg stability for clinical applications in which Tregs are expanded in vitro and infused into patients.

- 44.Grossman WJ, Verbsky JW, Tollefsen BL, Kemper C, Atkinson JP, Ley TJ. Differential expression of granzymes A and B in human cytotoxic lymphocyte subsets and T regulatory cells. Blood. 2004;104:2840–2848. doi: 10.1182/blood-2004-03-0859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Strauss L, Bergmann C, Whiteside TL. Human circulating CD4+CD25highFoxp3+ regulatory T cells kill autologous CD8+ but not CD4+ responder cells by Fas-mediated apoptosis. J Immunol. 2009;182:1469–1480. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.3.1469. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mandapathil M, Hilldorfer B, Szczepanski MJ, Czystowska M, Szajnik M, Ren J, Lang S, Jackson EK, Gorelik E, Whiteside TL. Generation and accumulation of immunosuppressive adenosine by human CD4+CD25highFOXP3+ regulatory T cells. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:7176–7186. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.047423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Costantino CM, Baecher-Allan C, Hafler DA. Multiple sclerosis and regulatory T cells. J Clin Immunol. 2008;28:697–706. doi: 10.1007/s10875-008-9236-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Oh S, Rankin AL, Caton AJ. CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in autoimmune arthritis. Immunol Rev. 2010;233:97–111. doi: 10.1111/j.0105-2896.2009.00848.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kuhn A, Beissert S, Krammer PH. CD4(+)CD25 (+) regulatory T cells in human lupus erythematosus. Arch Dermatol Res. 2009;301:71–81. doi: 10.1007/s00403-008-0891-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Venken K, Hellings N, Liblau R, Stinissen P. Disturbed regulatory T cell homeostasis in multiple sclerosis. Trends Mol Med. 2010;16:58–68. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2009.12.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Viglietta V, Baecher-Allan C, Weiner HL, Hafler DA. Loss of functional suppression by CD4+CD25+ regulatory T cells in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Exp Med. 2004;199:971–979. doi: 10.1084/jem.20031579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Haas J, Hug A, Viehover A, Fritzsching B, Falk CS, Filser A, Vetter T, Milkova L, Korporal M, Fritz B, et al. Reduced suppressive effect of CD4+CD25high regulatory T cells on the T cell immune response against myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein in patients with multiple sclerosis. Eur J Immunol. 2005;35:3343–3352. doi: 10.1002/eji.200526065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Venken K, Hellings N, Thewissen M, Somers V, Hensen K, Rummens JL, Medaer R, Hupperts R, Stinissen P. Compromised CD4+ CD25(high) regulatory T-cell function in patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis is correlated with a reduced frequency of FOXP3-positive cells and reduced FOXP3 expression at the single-cell level. Immunology. 2008;123:79–89. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2567.2007.02690.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Lawson JM, Tremble J, Dayan C, Beyan H, Leslie RD, Peakman M, Tree TI. Increased resistance to CD4+CD25hi regulatory T cell-mediated suppression in patients with type 1 diabetes. Clin Exp Immunol. 2008;154:353–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2008.03810.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Schneider A, Rieck M, Sanda S, Pihoker C, Greenbaum C, Buckner JH. The effector T cells of diabetic subjects are resistant to regulation via CD4+ FOXP3+ regulatory T cells. J Immunol. 2008;181:7350–7355. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.10.7350. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Venigalla RK, Tretter T, Krienke S, Max R, Eckstein V, Blank N, Fiehn C, Ho AD, Lorenz HM. Reduced CD4+,CD25− T cell sensitivity to the suppressive function of CD4+,CD25high,CD127 −/low regulatory T cells in patients with active systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Rheum. 2008;58:2120–2130. doi: 10.1002/art.23556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vargas-Rojas MI, Crispin JC, Richaud-Patin Y, Alcocer-Varela J. Quantitative and qualitative normal regulatory T cells are not capable of inducing suppression in SLE patients due to T-cell resistance. Lupus. 2008;17:289–294. doi: 10.1177/0961203307088307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Haas J, Fritzsching B, Trubswetter P, Korporal M, Milkova L, Fritz B, Vobis D, Krammer PH, Suri-Payer E, Wildemann B. Prevalence of newly generated naive regulatory T cells (Treg) is critical for Treg suppressive function and determines Treg dysfunction in multiple sclerosis. J Immunol. 2007;179:1322–1330. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.2.1322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Michel L, Berthelot L, Pettre S, Wiertlewski S, Lefrere F, Braudeau C, Brouard S, Soulillou JP, Laplaud DA. Patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis have normal Treg function when cells expressing IL-7 receptor alpha-chain are excluded from the analysis. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:3411–3419. doi: 10.1172/JCI35365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Trzonkowski P, Bieniaszewska M, Juscinska J, Dobyszuk A, Krzystyniak A, Marek N, Mysliwska J, Hellmann A. First-in-man clinical results of the treatment of patients with graft versus host disease with human ex vivo expanded CD4+CD25+CD127− T regulatory cells. Clin Immunol. 2009;133:22–26. doi: 10.1016/j.clim.2009.06.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zenewicz LA, Abraham C, Flavell RA, Cho JH. Unraveling the genetics of autoimmunity. Cell. 2010;140:791–797. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Baranzini SE. The genetics of autoimmune diseases: a networked perspective. Curr Opin Immunol. 2009;21:596–605. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2009.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. De Jager PL, Baecher-Allan C, Maier LM, Arthur AT, Ottoboni L, Barcellos L, McCauley JL, Sawcer S, Goris A, Saarela J, et al. The role of the CD58 locus in multiple sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:5264–5269. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0813310106. See annotation to Ref. [65].

- 64. Broux B, Hellings N, Venken K, Rummens JL, Hensen K, Van Wijmeersch B, Stinissen P. Haplotype 4 of the multiple sclerosis-associated interleukin-7 receptor alpha gene influences the frequency of recent thymic emigrants. Genes Immun. 2010;11:326–333. doi: 10.1038/gene.2009.106. See annotation to Ref. [65].

- 65. Swainson LA, Mold JE, Bajpai UD, McCune JM. Expression of the autoimmune susceptibility gene FcRL3 on human regulatory T cells is associated with dysfunction and high levels of programmed cell death-1. J Immunol. 2010;184:3639–3647. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.0903943. Along with Ref. [63] and Ref. [64], this paper provides evidence that SNPs associated with human autoimmune diseases have phenotypic and functional consequences for human Tregs. These studies suggest that genetic risk factors for autoimmune diseases may promote Treg dysfunction and thereby contribute to the pathogenesis of human autoimmune diseases.

- 66. Sadlon TJ, Wilkinson BG, Pederson S, Brown CY, Bresatz S, Gargett T, Melville EL, Peng K, D'Andrea RJ, Glonek GG, et al. Genome-Wide Identification of Human FOXP3 Target Genes in Natural Regulatory T Cells. J Immunol. 2010 doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1000082. This study identified the genome-wide binding targets of FoxP3 in human Tregs. This provides a wealth of data that has the potential to yield answers about the function of FoxP3 in human Treg biology, to identify more specific human Treg surface markers, and to yield hypotheses about the mechanisms of human Treg dysfunction in autoimmune diseases.