Abstract

The amyloid precursor protein (APP) has been mainly studied in its role in the production of amyloid β peptides (Aβ), because Aβ deposition is a hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease. Although several studies suggest APP has physiological functions, it is still controversial. We previously reported that APP increased glial differentiation of neural progenitor cells (NPCs). In the current study, NPCs transplanted into APP23 transgenic mice primarily differentiated into glial cells. In vitro treatment with secreted APP (sAPP) dose-dependently increased glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) immuno-positive cells in NPCs and over-expression of APP caused most NPCs to differentiate into GFAP immuno-positive cells. Treatment with sAPP also dose-dependently increased expression levels of GFAP in NT-2/D1 cells along with the generation of Notch intracellular domain (NICD) and expression of Hairy and enhancer of split 1 (Hes1). Treatment with γ-secretase inhibitor suppressed the generation of NICD and reduced Hes1 and GFAP expressions. Treatment with the N-terminal domain of APP (APP 1–205) was enough to induce up regulation of GFAP and Hes1 expressions, and application of 22C11 antibodies recognizing N-terminal APP suppressed these changes by sAPP. These results indicate APP induces glial differentiation of NPCs through Notch signaling.

Keywords: Alzheimer’s disease, amyloid precursor protein, Notch, glial differentiation, neural progenitor cells

1. Introduction

Amyloid precursor protein (APP) is a membrane-spanning glycoprotein consisting of 695- to 770-amino acids (Selkoe, 2001). Cytotoxicity of amyloid β peptides (Aβ), generated by subsequent cleavage of APP, has been extensively studied to understand the pathophysiology of Alzheimer’s disease (Haass and De Strooper, 1999; Price et al., 1998; Selkoe, 2001; Selkoe et al., 1996). Despite this, no consensus on physiological function(s) of APP exists (Reinhard et al., 2005). APP has been suggested as a ligand for receptors, such as a class A scavenger receptor (Santiago-Garcia et al., 2001). Since the crystal structure of the heparin-binding N-terminal domain of APP resembles a growth factor-like domain (Rossjohn et al., 1999; Schmitz et al., 2002; Small et al., 1994) N-terminal soluble APP may act as a growth factor. Previously, we found treatment of human neural progenitor cells (HNPCs) with secreted APP (sAPP) dose-dependently induced glial differentiation, which was inhibited by co-treatment with antibody recognizing APP (Kwak et al., 2006a). Additionally, APP plays a critical role in staurosporine-induced glial differentiation of NT-2/D1 cells (Kwak et al., 2006b). Bhan et al. showed NPCs isolated from Down’s Syndrome patients, who display Alzheimer’s disease-like pathology later in life, mainly differentiated into astrocytes while NPCs from healthy subjects produced both neurons and astrocytes (Bahn et al., 2002). Since Down’s syndrome patients have trisomy of chromosome 21, which contains the gene encoding APP, high levels of APP expression in Down’s Syndrome patients maybe responsible for the abnormal differentiation pattern of NPCs as well as Alzheimer’s disease pathology (Beyreuther et al., 1993; Engidawork and Lubec, 2001; Isacson et al., 2002; Teller et al., 1996). These findings suggest APP could be involved in glial differentiation of NPCs.

Notch signaling has been shown to control cell fate through local cell-to-cell interactions. During development, Notch suppresses neuronal differentiation in vivo and in vitro (Geling et al., 2004; Kabos et al., 2002). When ligands bind Notch, proteolytic cleavage of Notch receptors occurs by the γ-secretase/nicastrin complex to release the signal-transducing Notch intracellular domain (NICD) (Yu et al., 2000). Cleaved NICDs translocate into the nucleus and interact with a nuclear protein named CBF1/Su(H)/Lag-1 (CSL) (Schroeter et al., 1998). The CSL and NICD complex activates expression of primary target genes of Notch, such as Hairy and enhancer of split (Hes) gene families (Jarriault et al., 1998). Following activation, Hes suppresses expression of transcription factors involved in neuronal differentiation, such as Mash1 and NeuroD (Pleasure et al., 2000). Notch activation is reported to strengthen glial differentiation by crosstalk to IL-6 signaling pathways, which is a known central regulator of gliogenesis. IL-6 cytokine signaling activation induces subsequent phosphorylation of gp130, Janus kinases (JAKs), and signal transducer and activator of transcription 3 (STAT3) (Kamakura et al., 2004). Upon Notch activation, increased Hes is known to facilitate complex formation between JAK2 and STAT3, promoting STAT3 phosphorylation. This facilitates accessibility of STAT3 to the DNA binding element of the GFAP promoter. In the present study, we demonstrate APP may induce glial differentiation of NPCs through activation of the Notch signaling pathway.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1 Reagents and antibodies

The γ-secretase inhibitor, L-685,458 [(5S)-(t-Butoxycarbonylamino)-6-phenyl-(4R)hydroxy-(2R)benzylhexanoyl)-L-leu-L-phe-amide; Sigma], was dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide and stored at −80°C until use (Martys-Zage et al., 2000). Recombinant sAPPα protein (Sigma, Cat.#s S9564 and S8065) was dissolved in purified water and stored at −80°C until use.

2.2 Cell Culture

A method for the long-term growth of human neural precursor cells employed in this study was published by Svendsen et al. (Svendsen et al., 1998). Briefly, HNPCs (Brannen and Sugaya, 2000) proliferated in a defined media containing epidermal growth factor (EGF, 20 ng/ml R & D), fibroblast growth factor (FGF, 20 ng/ml R & D), B27 (1:50 Gibco), heparin (5 g/ml Sigma), antibiotic-antimycotic mixture (1:100 Gibco), minimum essential medium, Eagle’s Dulbecco’s modification, and Ham’s F-12 (DMEM/F12, Gibco). HNPCs were treated with sAPP for 5 days under serum-free conditions.

NT-2/D1 cells (Lee and Andrews, 1986) were seeded at a density of 5×106 cells per 150 mm petri dish in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM/F-12; Invitrogen) supplemented with 10% heat inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS; Novacell), 1% antibiotic-antimycotic mixture (Invitrogen), 4 mM glutamine (Invitrogen) and maintained in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2/95% air at 37 C (Sandhu et al., 2002). The cells were passed twice a week by short exposure to 0.25% trypsin/0.1% EDTA (Invitrogen). For all experiments, 106 NT-2/D1 cells were plated in 6-well cell culture plates. Subsequently, APP-induced differentiation of NT-2/D1 cells, under the treatment of condition media or various concentrations of recombinant APP, was evaluated for expression of astrocytic and neuronal markers by RT-PCR and Western blot analysis.

2.3 Construction of pGFAP-GFP-S65T stable transfectant

NT-2/D1 cells were transfected with pGFAP-GFP-S65T (provided by Dr. Albee Messing, University of Wisconsin-Madison) (Zhuo et al., 1997) using Lipofectamine™ 2000 (Invitrogen). After selection with 400g/ml geneticin, G418, (Invitrogen) for 15–20 days, single colonies were picked and tested for reporter assay. The pGFAP-GFP-S65T stably transfected cells were cultured in DMEM/F-12 supplemented with 10% heat inactivated FBS, 1% antibiotic-antimycotic, 4 mM glutamine and 200g/ml G418.

2.4 RT-PCR Analysis

Total RNA was extracted from the cells with Trizol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. One μg of the total RNA was reverse-transcribed and amplified by the SuperScript™ ONE-STEP™ RT-PCR system (Invitrogen) with the following primers:

GFAP (+) 5′-AAGCAGTCTACCCACCTCAG-3′,

(−) 5′-ATCCCTCCCAGCACCTCATC-3′;

Delta1 (+) 5′-TGCTGGGCGTCGACTCCTTCAGT-3′,

(−) 5′-GCCTGGCTCGCGGATACACTCGTCACA-3′;

Jagged-1 (+) 5′-ACACACCTGAAGGGGTGCGGTATA-3′,

(−) 5′-AGGGCTGCAGTCATTGGTATTCTGA-3′;

Hes1 (+) 5′-CGGACATTCTGGAAATGACA-3′,

(−) 5′-CATTGATCTGGGTCATGCAG-3′;

hNotch1 (+) 5′-GATGCCAACATCCAGGACAACATGGG-3′,

hNotch1 (−) 5′-GGCAGGCGGTCCATATGATCCGTGAT-3′;

hNotch2 (+) 5′-ACATCATCACAGACTTGGTC-3′,

hNotch2 (−) 5′-CATTATTGACAGCAGCTGCC-3′;

EGFP (+) 5′-CAAGGACGACGGCAACTACAAGAC-3′,

(−) 5′-GCGGACTGGGTGCTCAGGTAGTGGT-3′;

β-actin (+) 5′-GACAGGATGCAGAAGGAGAT-3′,

(−) 5′-TTGCTGATCCACATCTGCTG-3′.

Ten μl of the reaction mixtures were then analyzed on a 2% E-gel (Invitrogen). Gel images were captured using a KODAK Image Station 2000MM (KODAK).

2.5 Immunoprecipitation and Western Blot Analysis

To prepare mice brain lysates, mice brains were removed, regionally dissected into hippocampus and cortex regions, and immediately placed on dry ice and then stored at −80 C until Western blotting experiments were performed.

Protein samples were prepared by lysing the cells with ice-cold lysis buffer consisting of 1% NP40, 150 mM NaCl, 50 mM Tris pH 8.0 and protease inhibitors mix (Boehringer). The protein concentration of each sample was measured by the Bio-Rad protein assay (Bio-Rad). Lysates were immunoprecipitated with antibodies against GFAP, STAT3 and NICD molecules using protein A-Sepharose (Amersham Bioscience). Following immunoprecipitation, the samples of immunoprecipitant or cell lysates were heated at 70 C for 10 min in LDS (Lithium Dodecyl Sulfate) sample loading buffer (Selkoe, 2001) and separated on NuPAGE™ 4–12% Bis-Tis Gel (Invitrogen) for 45 min at 200V and transferred to a PVDF membrane (30V, 60 min). Membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk in PBS for 1h at RT and probed at 4 C overnight with primary antibody in 5% skim milk. In the present studies, the following antibodies (Abs) were used: rabbit anti-GFAP Ab (Promega); mouse anti-APP Ab (22C11) (Chemicon); rabbit anti-human STAT3 Ab (Chemicon); mouse anti-phospho-STAT3 (Ser727) Ab (Chemicon); rabbit anti-phospho-STAT3 (Tyr705) Ab (Cell Signaling); rabbit anti-activated Notch Ab (Abchem); mouse anti-GFP Ab (Zymed); and rabbit anti--actin Ab (Cell Signaling); anti-mouse IgG and anti-rabbit IgG horseradish peroxidase-conjugated Abs (Jackson Immunoresearch Laboratory). The membranes were washed 3 times for 5 min each with PBS containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T, pH 7.4) and incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated secondary antibodies in 5% skim milk for 2h at RT. After 3 times washing with PBS-T, immunoreactive bands were visualized by using ECL plus (Amersham Bioscience) chemiluminescence reagent. Western blot images were captured with KODAK Image Station 2000 MM (KODAK).

2.6 Stereotactic injection of HNPCs into mice

All animal studies have been done according to the animal protocol approved by the IACUC at the University of Central Florida. Eight month-old male APP23 transgenic (Sturchler-Pierrat et al., 1997) and wild-type mice were deeply anesthetized with 50 mg/kg pentobarbital and mounted on to a stereotaxic apparatus (ASI Instrument, USA). Using bregma as a reference point, approximately 105 HNPCs were suspended in 10 μl PBS, and slowly injected into the right lateral ventricle (coordinates: anterior posterior (A/P)−0.6 mm; medial lateral (M/L) +1.0 mm; dorsal/ventral (D/V) +2.4 mm) of each mouse using a 25 μl Hamilton gastight micro syringe (Hamilton, Reno, NV, USA) attached with a 22-gauge beveled needle.

2.7 Immunohistochemistry

Detailed methods for immunohistochemistry have previously been described (Dong et al., 2003; Qu et al., 2001). Briefly, 6 weeks post-transplantation, animals (n=6–8) were transcardially perfused with PBS. The remaining group of mice with HNPC implants (n=6) was transcardially perfused with PBS and 4% paraformaldehyde (pH 7.4). Brains were removed and post-fixed for 8–12 h in 4% paraformaldehyde, and cryoprotected in 20% sucrose-PBS overnight. The brains were subsequently cut on a cryostat (20 μm coronal free floating sections) and kept in PBS at 4 C. For fluorescent immunohistochemical analysis, sections were washed three times and blocked with 3% donkey serum in PBS containing 0.25% Triton X-100 for 1h at RT. After serum blocking, sections were incubated with a combination of primary antibodies for mouse IgG2b anti-human βIII-Tubulin, clone SDL3D10 (1:1000, Sigma) and goat anti human-glial filament protein, GFAP (N’-terminal human affinity purified, 1:500, Research Diagnostics Inc., Flander, NJ) (Kim et al., 2002), or mouse monoclonal anti human-GFAP (1:250, Sternberger Monoclon SMI 21), mouse anti human Aβ antibody (4G8, 1: 300, Abcam) and Sheep anti bromodeoxyuridine (1:300, Sigma for detection of cells derived from transplanted HNPCs), diluted in PBS containing 0.25% Triton X-100 and with 3% normal donkey serum overnight at 4 C. After 3 washes in PBS-T, sections were incubated with corresponding secondary antibodies for anti-mouse, anti goat, anti-sheep (1:500) conjugated with fluorescein (FITC) or rhodamine (TRITC) (Jackson IR Laboratories, Inc.) for 2 h at RT. After a final wash in PBS-T, sections were mounted and cover slipped with Vectashield with DAPI (Vector Laboratories, Inc., Burlingame, CA) and observed using a Leica DMRB fluorescent microscope. Microscopic images were taken with an Axiocam digital camera (Carl Zeiss) mounted on the DMRB and processed using the QIMAGING with Q Capture software (Qimaging Corporation).

2.8 Immunocytochemistry

For fluorescent immunocytochemistry of the HNPCs, treatment of recombinant sAPP and transfection of APP expression vector was performed. Cells were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 20 min at RT, and then washed in PBS-T, and thereafter incubated in PBS-T containing 3% normal donkey serum. Next, the samples were incubated overnight at 4 C (up to 12 h) with the following primary antibodies: mouse anti human Aβ antibody, 4G8 (1:50, Senetek); mouse IgG1 6E10, (1:50, Senetek); mouse IgG anti-Alzheimer Precursor Protein A4, 22C11 (1:100, Chemicon); mouse IgG2b anti-human βIII-Tubulin, clone SDL3D10 (1:1000, Sigma) and goat anti human-glial filbrillary protein, GFAP (N-terminal human affinity purified, 1:400, Research Diagnostics Inc., Flander, NJ). After washing with PBS, samples were incubated with corresponding secondary antibodies coupled to FITC or TRITC for 1.5 h in a dark humidified chamber. Next, the samples were washed thoroughly in PBS and cover slipped with Vectashield mounting media with DAPI (Vector) for fluorescent microscopic observation.

3. Results

3.1 Increased glial differentiation of HNPCs in APP23 transgenic mice

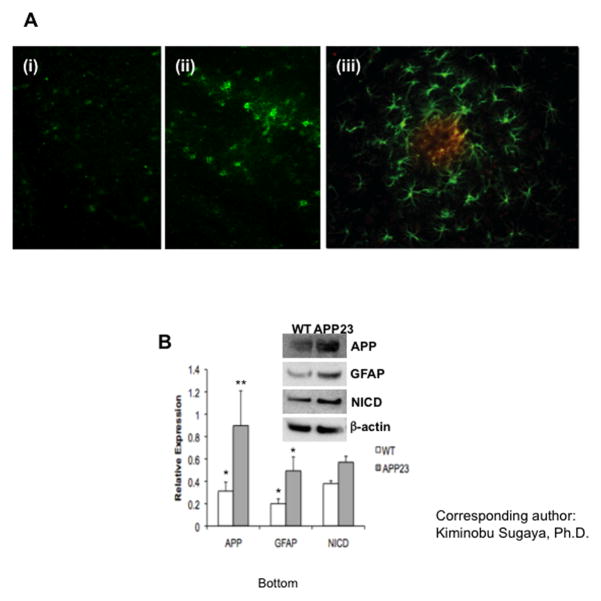

To examine whether APP has an effect on the differentiation of HNPCs in adult mice in vivo, we transplanted HNPCs into the cerebro lateral ventricle of APP23 transgenic and wild type (WT) mice at 8 and 12 months of age. To identify the transplanted HNPCs in the host brain, anti-human specific GFAP antibody was used for the fluorescent immunohistochemistry. The majority of the transplanted HNPCs were differentiated into GFAP-positive astrocytes in the cortex of APP23 transgenic mice 4 weeks after transplantation. While few GFAP-positive cells were found in the WT mice (Fig. 1A–i and ii), in 12 month old APP23 mice with progressed Aβ pathology, more activated astrocytes were found surrounding the area of Aβ deposits (Fig. 1A–iii). These results indicate that high levels of APP in the transgenic mice induce glial differentiation of HNPCs and Aβ deposits may attract and/or activate astrocytes. We compared the protein expression levels of APP, GFAP and NICD in the cerebral cortex of 8 month-old WT and APP23 mice using Western blot analysis (Fig. 1B). Both APP and GFAP were expressed at higher levels in APP23 mice compared to WT mice. APP23 transgenic mice also expressed higher levels of NICD, indicating activations of Notch signaling.

Fig. 1. Differentiation of HNPCs into astroglial cells in vivo.

(A) Representative fluorescent immunohistochemistry of wild type and APP23 mice brain 4–6 weeks after HNPCs transplantation. More human GFAP immunopositive cells were observed in the cortex of APP23 (ii) compare to wild type mice (i) at 8 months old. Human GFAP immnopositive cells showing active gliogenesis morphology were detected around plaque-like formations in the cortex of 12 month old APP23 transgenic mice (iii). Green and red stainings represent immunoreactivity for GFAP and Aβ recognized by 4G8, respectively. All the nuclei were counter stained by DAPI. (B) Western blot analysis of protein expression of APP, GFAP, and NICD in the brain of 8 months old WT and APP23 transgenic mice. Anti-APP and anti-NICD antibodies were used to recognize APP and NICD, respectively. One-factor ANOVA followed by post hoc analysis (Student-Newman-Keuls) was used to analyze the differences between experimental groups and control groups (*: p<0.05, **: p<0.01).

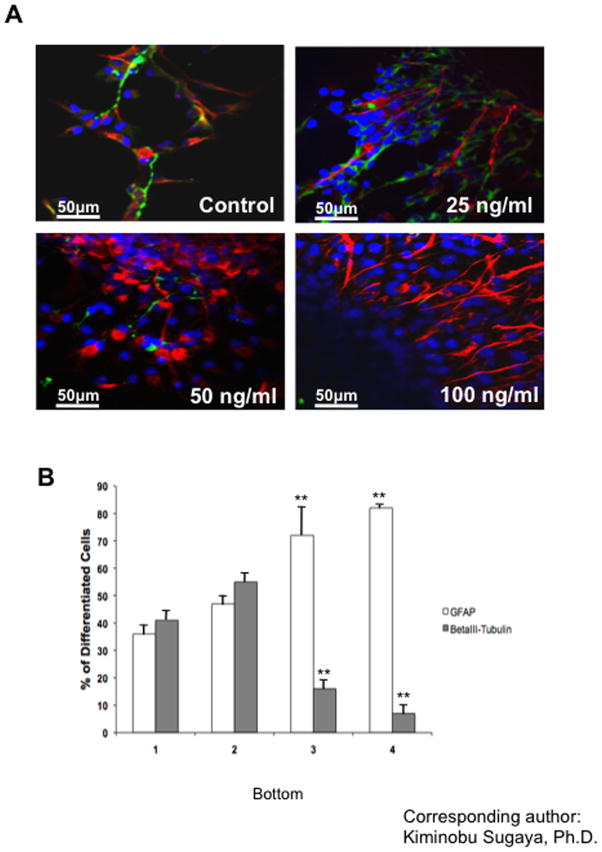

3.2 sAPP increases glial differentiation of HNPCs in vitro

To investigate the effect of APP on HNPC differentiation, we analyzed the cell population of differentiating HNPCs treated with sAPP (control, 25, 50, 100 ng/ml) for 5 days under serum-free conditions by double-immunofluorescent staining for GFAP and βIII-tubulin, markers for astrocytes and neurons respectively (Fig. 2A). Treatment with recombinant sAPP dose-dependently increased the population of GFAP-positive cells from 45% to 83% (Fig. 2B). Interestingly, a lower dose of sAPP treatment (25ng/ml) increased the population of both GFAP and βIII-tubulin-positive cells. However, higher doses of sAPP (50 and 100 ng/ml) dose-dependently decreased βIII-tubulin-positive cells from 51% to 13% of the total population of differentiated HNPCs (Fig. 2B). We counted 10 different fields of view in the microscope. Each view had a different number of total cells. If we give the data an absolute number, it will have high variations. Also, in low concentration, some of the cells are not differentiated into GFAP or βIII-tubulin positive cells. This is why the percentages do not add up to 100%. Where as in high APP conditions, most of the cells are differentiated into either GFAP or βIII-tubulin positive cells. These results suggest that sAPP increases both glial and neuronal differentiations at the lower dose, but in the higher dose sAPP suppresses neuronal and promotes glial differentiations. sAPP may be influencing the cell fate decision of HNPCs because sAPP treatment did not increase TUNEL (Terminal UDT Nucleotide End Labeling) signals, a marker for apoptosis, in the HNPCs culture thus selective death of pro neural progenitors in the neurospheres may be ruled out (data not shown).

Fig. 2. Effect of treatment with sAPP and overexpression of APP on differentiation of HNPCs.

(A) HNPCs treated with sAPP (control, 25, 50, 100 ng/ml) for 5 days under serum-free conditions by double-immunofluorescent staining for GFAP (red) and βIII-tubulin (green), markers for astrocytes and neurons respectively. All nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). (B) The cell population of HNPCs treated with sAPP (1; control, 2; 25 ng/ml, 3; 50 ng/ml and 4; 100 ng/ml) 5 days after differentiated under serum-free unsupplemented conditions. All data values are expressed as mean percentages (±S.E.M.). One-factor ANOVA followed by post hoc analysis (Student-Newman-Keuls) was used to analyze the differences between experimental groups and control groups (*: p<0.05, **: p<0.01).

3.3 sAPP induced GFAP expression in NT-2/D1 cells

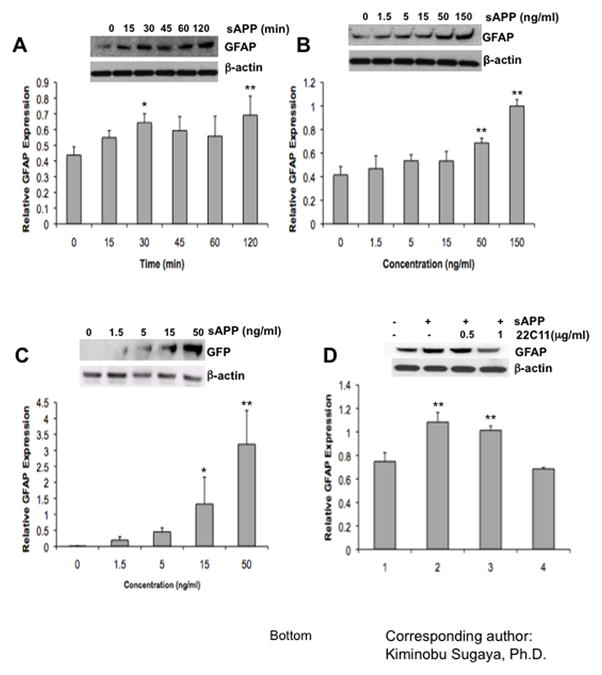

To analyze mechanisms of sAPP function that regulate the differentiation process of NPCs, we examined the effects of sAPP on differentiation of NT-2/D1 teratocarcinoma cells committed to differentiate into neural lineages. Expression of GFAP was increased in NT-2/D1 by treatment with recombinant sAPP in a time- (Fig. 3A) and dose-dependent manner (Fig. 3B). We also examined the effect of sAPP on GFAP promoter activity using NT-2/D1 cells stably transfected with a GFAP promoter-driven GFP expression vector (pGFAP-GFP-S65T) as a reporter system. Treatment of NT-2/D1 cells with sAPP and transfected with pGFAP-GFP-S65T, showed a dose-dependent increase of GFP protein expression, indicating that sAPP induces glial differentiation by activation of the GFAP promoter (Fig 3C). For further investigation, we applied 22C11 antibodies, which recognize the N-terminal domain of APP, to neutralize the effect of sAPP in glial differentiation of NT-2/D1 cells in culture. We observed that treatment with 22C11 antibodies effectively suppress GFAP expression in NT-2/D1 cells (Fig. 3D), indicating importance of the N-terminal domain of APP in sAPP induced glial differentiation.

Fig. 3. Induction of GFAP expression in sAPP treated NT-2/D1 cells.

(A) Western blot analysis for measuring GFAP expression. Cells were grown in 100ng/ml of recombinant sAPP containing media. Level of β-actin was used as a loading control. (B) Western blot analysis of GFAP expression, which is induced by various concentrations of recombinant sAPP. Level of β-actin used as a loading control. (C) Western blot analysis of GFP expression which is transcribed by GFAP promoter.

NT-2/D1 cells were transfected with pGFAP-GFP-S65T vectors as a reporter system. To investigate the function of sAPP on a GFAP promoter, cells were treated with a variety of concentrations (0, 1.5, 5, 15, and 50 ng/ml) of sAPP. (D) NT-2/D1 cells were treated with sAPP for 18 h in the presence of anti-APP neutralizing Ab (22C11) and observed the expression changes of GFAP by Western blot analysis. Experiments were repeated at least three times with similar results.

Western blot analyses for GFAP expression in NT-2/D1 cells (A) in 100 ng/ml of recombinant sAPP containing media, (B) induced by various concentrations of recombinant sAPP, (C) transcribed by GFAP promoter, and (D) treated with sAPP for 18hrs in the presence of anti-APP neutralizing Ab (22C11). Expression of β–actin served as a loading control. Experiments were repeated at least three times with similar results. One-factor ANOVA followed by post hoc analysis (Student-Newman-Keuls) was used to analyze the differences between experimental groups and control groups (*: p<0.05, **: p<0.01).

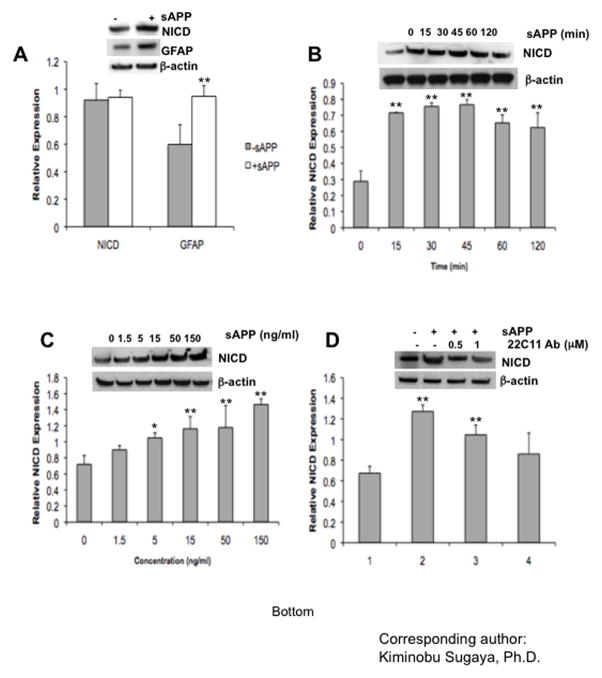

3.4 sAPP induces glial differentiation via the Notch signaling pathway

Treatment with sAPP increased NICD and GFAP protein expression in NT-2/D1 cells (Fig 4A), similar to our in vivo study showing increased NICD and GFAP expression in APP23 transgenic mice (Fig. 1B). These results indicate that over expression of sAPP may cause glial differentiation by stimulating Notch proteolysis. Next, we investigated both the time- and dose-dependent effects of sAPP on the generation of NICD. NICD generation was observed 15 min after treatment with sAPP (100 ng/ml). The effect lasted up to 60 min and then shows a slight reduction at 120 min, thus, indicating that sAPP may be directly activating the Notch signaling cascade (Fig. 4B). Following treatment with sAPP, dose-dependent increases of NICD were observed in NT-2/D1 cells (Fig. 4C). This sAPP-induced NICD generation was dose-dependently suppressed by 22C11 antibody, which recognize the N-terminal of APP (amino acids 66–82) (Fig. 4D).

Fig 4. sAPP stimulates the Notch signaling pathway during gliogenesis.

(A) Treatment of sAPP (100ng/ml) promoted GFAP expression as well as NICD generation. (B) and (C) sAPP induced generation of NICD in a time- and dose- dependent manner as indicated above. Generation of NICD was measured by Western blot analysis using anti-active Notch Ab. (D) sAPP induced NICD generation was suppressed by neutralizing antibody (22C11). One-factor ANOVA followed by post hoc analysis (Student-Newman-Keuls) was used to analyze the differences between experimental groups and control groups (*: p<0.05, **: p<0.01).

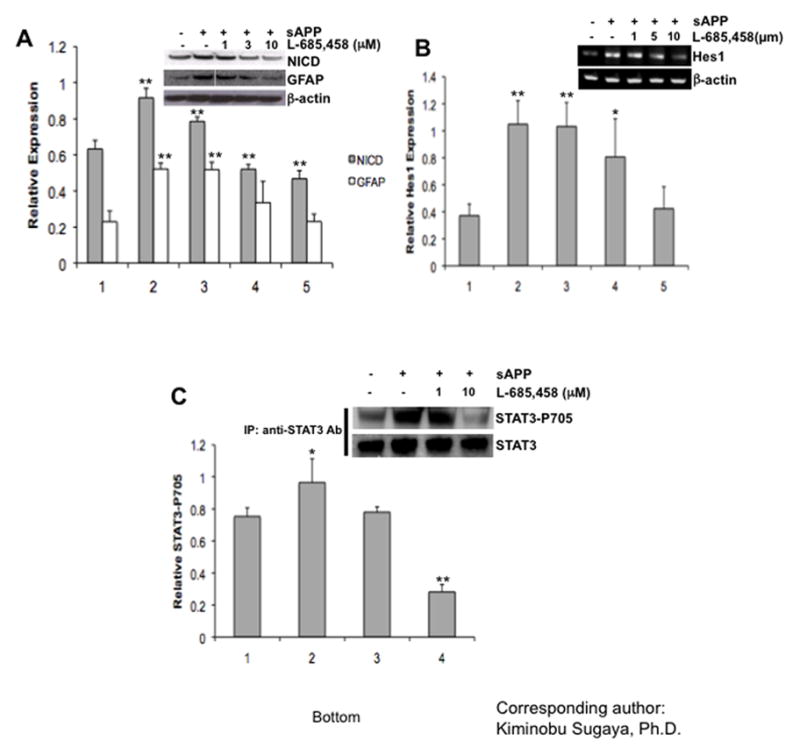

3.5 Stimulation of the Notch signaling pathway by sAPP requires γ-secretase activity

NICDs are generated by γ-secretase under the stimulation of Notch ligands, such as Delta and Jagged1. Treatment with L-685,458, γ-secretase inhibitors, dose-dependently (1, 3, and 10 μM) inhibited both NICD generation and GFAP expression increased by sAPP (Fig. 5A). Expression of Hes1, a target gene of Notch signaling, was also suppressed by treatment with L-685,458 (Fig. 5B). These results suggest that sAPP-induced glial differentiation is mediated through the γ-secretase dependent Notch signaling pathway.

Fig 5. Stimulation of Notch signaling pathway by sAPP require γ-secretase activity.

Western blot analyses showing (A) both sAPP-induced NICD generation and GFAP expression were mediated by stimulation of γ-secretases, (B) PCR showing Hes1 gene expression level before and after treatment with sAPP and the dose-dependent effect of the γ-secretases, (C) detection of STAT3-Tyr-705 phosphorylation after immunoprecipitation. Expression of β-actin was examined as a loading control for (A) and(B). Expression of STAT3 was examined as a loading control for (C). Experiments were repeated at least three times with similar results. One-factor ANOVA followed by post hoc analysis (Student-Newman-Keuls) was used to analyze the differences between experimental groups and control groups (*: p<0.05, **: p<0.01).

Recently, He et al. proposed that the Jak/STAT pathway is central to the gliogenic machinery and postulated a framework for understanding the control of gliogenesis during development (He et al., 2005). Treatment with sAPP increased phosphorylation of STAT3, which was suppressed when treated with L-685,458 (Fig 5C), indicating existence of crosstalk between the Notch and Jak/STAT pathway in APP-induced glial differentiation.

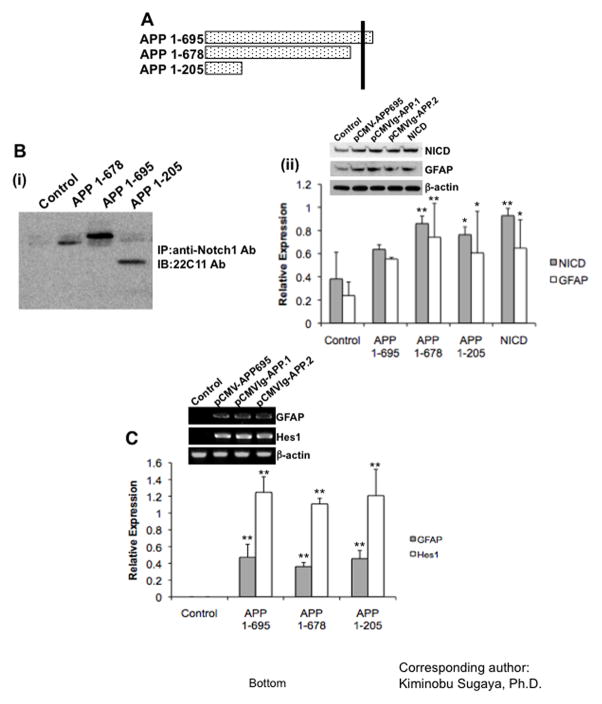

3.6 Interaction between sAPP and Notch is crucial for glial differentiation

There are two potential mechanisms associated with APP-induced Notch signaling activation. First, APP may indirectly stimulate Notch signaling by up regulating expression of Notch ligands, such as Delta or Jagged. Second, a potential direct activation through protein-protein interaction of APP to Notch, because several studies reported that APP could physically interact with Notch (Oh et al., 2005). We found that sAPP treatment of NT-2/D1 cells did not change the expression of Notch ligands (Delta1, Jagged1) or Notch receptors (hNotch1 and 2) while the expression of Hes1 was drastically increased (Fig 6), indicating that APP-induced Notch signaling activation does not involve up regulation of Notch ligands or Notch receptors expression. The Notch–APP protein interaction study using APP (1–695), sAPPα (1–678) and N-terminal domain of APP (1– 205) (Fig. 7A), revealed that the N-terminal domain of APP (1–205) was sufficient for the physical interaction with Notch (Fig. 7B–i). This result is in agreement with recent reports, which have showed a protein-protein interaction of APP and Notch. Here we not only confirm direct interaction of APP and Notch but also, for the first time, we demonstrate that APP activates a Notch signaling cascade and causes glial differentiation of NPCs.

Fig 6. Effect of APP on gene expressions of Notch ligands or Notch receptors.

The effect of APP on gene expressions related to the Notch signaling cascade was assessed through PCR. Increased expression of Hes1 was observed after sAPP treatment while most of Notch signaling related genes were not affected by treatment of sAPP. Expression of β-actin was examined as a loading control. One-factor ANOVA followed by post hoc analysis (Student-Newman-Keuls) was used to analyze the differences between experimental groups and control groups (*: p<0.05, **: p<0.01).

Fig 7. Physical interaction of APP and Notch is crucial for stimulation of gliogenesis.

(A) Schematic diagram of truncated mutants of APP clones. Several truncated N-terminal domains of APP (1–695, 1–678, and 1–205 a.a.) were used for functional analysis. (B) (i) Protein-protein interaction of APP and Notch was tested by using immunoprecipitation. Proteins were extracted from NT-2/D1 cells using NP40 lysis buffer. Then, protein complexes were precipitated by anti-Notch Abs and Western blot analyses were performed by using anti-22C11 Abs. (ii) The cells were transfected with truncated N-terminal domains of APP (1–695, 1–678, and 1–205 a.a.) and NICD, then the protein extracts were analyzed by Western blot with anti-active Notch Ab and anti-GFAP Ab. (C) PCR results showed the N-terminal domain of APP enhanced mRNA expression level of both GFAP and Hes1. Expression of β-actin was examined as a loading control. Experiments were repeated at least three times with similar results. One-factor ANOVA followed by post hoc analysis (Student-Newman-Keuls) was used to analyze the differences between experimental groups and control groups (*: p<0.05, **: p<0.01).

3.7 N-terminal domain of APP is sufficient for induction of glial differentiation

A variety of physiological functions of APP may associate with a variety of functional domains in its structure. Several reports demonstrated that the N-terminal of APP, containing a cysteine rich domain and a heparin binding site (Rossjohn et al., 1999) which are involved in protein-protein interaction with NGF receptors, has a growth factor like function (Caille et al., 2004). Thus we further investigated whether the N-terminal domain of APP is sufficient for glial differentiation. We transfected three different vectors containing truncated mutants of APP [pCMV-APP695 (APP 1–695), pCMVIg-APP.1 (APP 1–678), and pCMVIg-APP.2 (APP 1–205)] into NT-2/D1 cells and then analyzed GFAP, Hes1 gene expression and NICD generation (Fig. 7B–ii and C). As shown in Figure 7C, the N-terminal domain of APP was sufficient to induce GFAP and Hes1 gene expression and NICD generation. These results indicate that the N-terminal domain of APP causes glial differentiation of neural progenitor cells through the activation of Notch signaling by a direct protein-protein interaction.

4. Discussion

In terms of an amyloidogenic process, APP has been extensively studied as a precursor of Aβ, which is a main component of plaques and a pathological hallmark of Alzheimer’s disease. However, the physiological function of APP has not been fully established. Previously, we reported APP has a crucial role in altering expression of astrocytic markers such as GFAP, astrocyte-specific glutamate transporter-1 (GLT-1)/excitatory amino acid transporter-2 (EEAT-2), and aspartate transporter-2 (GLAST)/EEAT-1 associated with morphological changes in neural precursor NT-2/D1 cells (Kwak et al., 2006b). When NPCs were treated with sAPP, differentiation was induced but the differentiation pattern was shifted to produce more astrocytes, which was blocked by treatment with antibody recognizing APP (Kwak et al., 2006b). These results indicate the involvement of APP in glial differentiation of NPCs. We report APP induces glial differentiation of NPCs and a novel mechanism of APP function in regulation of cell fate through the Notch signaling cascade.

Glial differentiation of NPCs is induced by various factors during late embryonic stage (mouse E16–17) and postnatal period (Lee et al., 2000; Nakashima and Taga, 2002; Price, 1994). These factors include IL-6 cytokine families (Rajan and McKay, 1998; Taga and Fukuda, 2005), bone morphogenic factors (Fukuda and Taga, 2006), basic fibroblast growth factor (Song and Ghosh, 2004), and Notch ligands (Kageyama et al., 2005; Lundkvist and Lendahl, 2001). Western blot analysis revealed protein levels of APP, GFAP and NICD in the cortex were higher in APP23 transgenic mice compared to wild type mice (Fig. 1). As we discussed above, Down’s syndrome patients show Alzheimer’s disease-like pathology in the later stage of disease (Wisniewski et al., 1985) and express high levels of APP similar to Alzheimer’s disease (O’Hara et al., 1989; Querfurth et al., 1995). In the adult Down’s syndrome cortex, up regulations of Notch1 and Hes1 expressions were observed (Fischer et al., 2005). NPCs isolated from Down’s syndrome patients mainly differentiated into astrocytes in vitro (Bahn et al., 2002). Previously, we found wtAPP-transfected HNPCs behaved similar to Down’s syndrome patient’s NPCs, indicating over expression of the APP gene induced glial differentiation in NPCs (Kwak et al.). Here, treatment with recombinant sAPP dose-dependently increased glial differentiations and suppressed neuronal differentiations of HNPCs, indicating environmental APP may function as a ligand. These results led to a hypothesis that higher levels of extra cellular APP may cause glial differentiation of NPCs associated with activation of Notch signaling. Since we detected GFAP promoter activation in NPCs, NT-2/D1, after sAPP treatment, we used this model to further investigate mechanisms of APP function in regulation of GFAP expression through Notch signaling pathway.

We found increased NICD generation and Hes1 expression associated with GFAP expression after sAPP treatment in NT-2/D1, indicating APP increased GFAP expression by activation of the Notch signaling cascade. NICD secretion by γ-cleavage of Notch may be an important element of APP function since co-treatment with γ-secretase inhibitor, L-685,458, inhibited these responses to sAPP treatment. It is possible sAPP may increase glial differentiation of NPCs by inhibiting expression of neurogenic transcription factors such as NeuroD and Mash1 (Pleasure et al., 2000). However, we did not detect changes in gene expression of NeuroD or Mash1 with/without sAPP treatment in NT-2/D1 cells (data not shown) indicating treatment with sAPP may selectively force cell fate specification of neural precursors into glia cells by other downstream mechanisms of the Notch signaling cascade.

It is known GFAP gene expression is up regulated by phosphorylation of STAT3-Tyr705 through activation of the gp130/IL-6 signaling pathway (Bonni et al., 1997). Recently, cross talk of Notch and JAK/STAT pathways through physical interaction between Hes1 and JAK2 has been reported (Kamakura et al., 2004). The Hes1 and JAK2 complex, which facilitates phosphorylation of STAT3, may maximize accessibility of STAT3 to STAT3-binding elements found in the GFAP promoter. Thus, activation of the Notch signaling cascade may synergistically increase glial differentiation by positive-regulation of the gp130/IL-6 signaling pathway. Here, phosphorylation of STAT3 was increased by APP-induced Notch signaling activation. Since phosphorylation of STAT3 was reduced by inhibition of γ-cleavage of Notch, which consequently reduces Hes1 gene expression, APP-induced glial differentiation of NPCs may involve increasing GFAP expression level through the gp130/IL-6 signaling pathway. Although further studies are needed, these results suggest sAPP induces glial differentiation by phosphorylation of STAT3 through cross talk between Notch and gp130/IL-6 signaling pathways.

The structure of APP695 consists of several characteristic elements. The N-terminal of APP695 is composed of a signal peptide for trafficking, a cysteine-rich domain (CRD), a zinc-binding motif, and acidic sequences (Reinhard et al., 2005). The central APP domain (CAPPD) consists of a large domain, which does not contain cysteine residues, and a short linker sequence harboring α- and β-secretase cleavage sites (Reinhard et al., 2005). The C-terminal of APP harbors a transmembrane region and a cytoplasmic tail.

Since co-treatment with antibody recognizing the N-terminal of APP reduced glial differentiation of NPCs, we tested whether the N-terminal domain of APP is enough to induce glial differentiation of NPCs. To elucidate the functional properties of the N-terminal domain of sAPP in glial differentiation, we examined the expression of GFAP and Hes1, and the generation of NICDs after treatment with conditioned media, which are harboring full length APP695, APP1-678, and APP1-205. Treatment with APP and truncated mutants of APP promoted gene expression of GFAP and Hes1 as well as NICD generation. These findings suggest sAPP may function as a ligand for Notch in NPCs treated with APP.

While several groups reported sAPP promoted proliferation of NPCs (Caille et al., 2004; Ohsawa et al., 1999), it is in veil whether sAPP affects cell proliferation rather than differentiation. Callie et al. demonstrated the soluble form of APP can specifically bind and increase the number of epidermal growth factor-responsive progenitor cells in the adult subventricular zone of the lateral ventricle (Caille et al., 2004). Thus, their findings suggest sAPP may have different properties on different lines of neural cells. In our studies, treatment with sAPP slightly reduced proliferation of NT-2/D1 cells.

When sAPP was applied to NPCs, it potently generated NICDs in a time- and dose-dependent manner and eventually turned on gene transcription of Hes1, a neuronal repressor. Since these sequential events were usually executed by recruiting γ-secretase under stimulation of Notch ligands, we examined whether sAPP can also stimulate the Notch signaling pathway similarly with other Notch ligands such as Deltas or Jaggeds. To determine the specific mechanisms, a γ-secretase inhibitor, L-685,458, was used to suppress the function of the γ-secretase/nicastrin complex. L-685,458, inhibited generation of NICD and induction of Hes1 gene expression efficiently.

Expression of GFAP protein and phosphorylation of STAT3 were also diminished by L-685,458. In agreement with our findings, a recent study reported the Notch signaling pathway can cross talk with the JAK/STAT3 signaling pathway through interaction of Hes1 and JAK2 (Kamakura et al., 2004). These complexes enhance the accessibility of STAT3 homodimers to promoter sites and potentiate gene expression of target genes. These findings suggested treatment with sAPP might induce glial differentiation by enhancing GFAP expression via the Notch signaling pathway. To date, it has been in veil how sAPP stimulates these signaling cascades. We hypothesized there may be two possible ways to stimulate glial differentiation by treatment with sAPP. First, treatment with sAPP may promote expression of various ligands or receptors, associated with Notch receptors, such as Delta and Jagged. However, in our previous paper, longer treatment with sAPP (24hrs) up regulated expression of Notch ligands. These discrepancies may be caused by commitment of neuroprecursor NT-2 cells to glial cells. The other possibility is sAPP may directly interact with Notch molecules to induce signals for glial differentiation, similar to Notch ligands. If our first hypothesis was correct, treatment with sAPP would increased expression of ligands associated with the Notch signaling pathway and sequentially stimulate a downstream signaling cascade. However, our findings indicate this is not true since there were no significant changes in Notch related gene expression except for the Hes1 gene, a target of NICD (Fig. 5A). To examine physiological interaction of APP to Notch, we performed immunoprecipitation and found sAPP and Notch were co-precipitated, indicating direct interaction of these proteins (Fig. 5C). Although further protein-protein interaction studies are needed, interaction of sAPP with Notch could be a candidate for inducing glial differentiation of NPCs. In support of our findings, several recent studies have demonstrated protein-protein interaction between sAPP and Notch (Fassa et al., 2005; Fischer et al., 2005; Oh et al., 2005). Our present findings address a novel APP function in glial differentiation mechanisms, which may aid in the development of novel therapeutic strategies for Alzheimer’s disease. Also, these indicate a limitation for the clinical use of stem cell therapy in Alzheimer’s disease, which is the low efficacy of neuronal differentiation of transplanted stem cells. Even if stem cells were transplanted into Alzheimer’s disease patient’s brains, these implanted cells may differentiate into glia due to the pathological environment of Alzheimer’s disease. However, if glial differentiation related signaling pathways are regulated, we may improve the success rate of stem cell therapy for Alzheimer’s disease.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate Dr. Thomas Sudhof and Dr. Gerry Weinmaster for the generous provision of the plasmids. We would like to thank Stephanie Merchant for editing. This work is supported by NIH (R01 AG23472) and Alzheimer’s Association (IIRG-03-5577) to Dr. Kiminobu Sugaya. Young-Don Kwak is a recipient of the 2004 Sigma Xi Grant aid program.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Bahn S, Mimmack M, Ryan M, Caldwell MA, Jauniaux E, Starkey M, Svendsen CN, Emson P. Neuronal target genes of the neuron-restrictive silencer factor in neurospheres derived from fetuses with Down’s syndrome: a gene expression study. Lancet. 2002;359:310–315. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07497-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyreuther K, Pollwein P, Multhaup G, Monning U, Konig G, Dyrks T, Schubert W, Masters CL. Regulation and expression of the Alzheimer’s beta/A4 amyloid protein precursor in health, disease, and Down’s syndrome. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1993;695:91–102. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1993.tb23035.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonni A, Sun Y, Nadal-Vicens M, Bhatt A, Frank DA, Rozovsky I, Stahl N, Yancopoulos GD, Greenberg ME. Regulation of gliogenesis in the central nervous system by the JAK-STAT signaling pathway. Science. 1997;278:477–483. doi: 10.1126/science.278.5337.477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brannen CL, Sugaya K. In vitro differentiation of multipotent human neural progenitors in serum-free medium. Neuroreport. 2000;11:1123–1128. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200004070-00042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caille I, Allinquant B, Dupont E, Bouillot C, Langer A, Muller U, Prochiantz A. Soluble form of amyloid precursor protein regulates proliferation of progenitors in the adult subventricular zone. Development. 2004;131:2173–2181. doi: 10.1242/dev.01103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong X, Pulido JS, Qu T, Sugaya K. Differentiation of human neural stem cells into retinal cells. Neuroreport. 2003;14:143–146. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200301200-00026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Engidawork E, Lubec G. Protein expression in Down syndrome brain. Amino Acids. 2001;21:331–361. doi: 10.1007/s007260170001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fassa A, Mehta P, Efthimiopoulos S. Notch 1 interacts with the amyloid precursor protein in a Numb-independent manner. J Neurosci Res. 2005;82:214–224. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20642. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fischer DF, van Dijk R, Sluijs JA, Nair SM, Racchi M, Levelt CN, van Leeuwen FW, Hol EM. Activation of the Notch pathway in Down syndrome: cross-talk of Notch and APP. Faseb J. 2005;19:1451–1458. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-3395.com. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fukuda S, Taga T. Roles of BMP in the development of the central nervous system. Clin Calcium. 2006;16:781–785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geling A, Plessy C, Rastegar S, Strahle U, Bally-Cuif L. Her5 acts as a prepattern factor that blocks neurogenin1 and coe2 expression upstream of Notch to inhibit neurogenesis at the midbrain-hindbrain boundary. Development. 2004;131:1993–2006. doi: 10.1242/dev.01093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haass C, De Strooper B. The presenilins in Alzheimer’s disease--proteolysis holds the key. Science. 1999;286:916–919. doi: 10.1126/science.286.5441.916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He F, Ge W, Martinowich K, Becker-Catania S, Coskun V, Zhu W, Wu H, Castro D, Guillemot F, Fan G, de Vellis J, Sun YE. A positive autoregulatory loop of Jak-STAT signaling controls the onset of astrogliogenesis. Nat Neurosci. 2005;8:616–625. doi: 10.1038/nn1440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isacson O, Seo H, Lin L, Albeck D, Granholm AC. Alzheimer’s disease and Down’s syndrome: roles of APP, trophic factors and ACh. Trends Neurosci. 2002;25:79–84. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(02)02037-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarriault S, Le Bail O, Hirsinger E, Pourquie O, Logeat F, Strong CF, Brou C, Seidah NG, Isral A. Delta-1 activation of notch-1 signaling results in HES-1 transactivation. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:7423–7431. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.12.7423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kabos P, Kabosova A, Neuman T. Blocking HES1 expression initiates GABAergic differentiation and induces the expression of p21(CIP1/WAF1) in human neural stem cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:8763–8766. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100758200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kageyama R, Ohtsuka T, Hatakeyama J, Ohsawa R. Roles of bHLH genes in neural stem cell differentiation. Exp Cell Res. 2005;306:343–348. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2005.03.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamakura S, Oishi K, Yoshimatsu T, Nakafuku M, Masuyama N, Gotoh Y. Hes binding to STAT3 mediates crosstalk between Notch and JAK-STAT signalling. Nat Cell Biol. 2004;6:547–554. doi: 10.1038/ncb1138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim HM, Qu T, Kriho V, Lacor P, Smalheiser N, Pappas GD, Guidotti A, Costa E, Sugaya K. Reelin function in neural stem cell biology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:4020–4025. doi: 10.1073/pnas.062698299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak YD, Brannen CL, Qu T, Kim HM, Dong X, Soba P, Majumdar A, Kaplan A, Beyreuther K, Sugaya K. Amyloid precursor protein regulates differentiation of human neural stem cells. Stem Cells Dev. 2006a;15:381–389. doi: 10.1089/scd.2006.15.381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak YD, Choumkina E, Sugaya K. Amyloid precursor protein is involved in staurosporine induced glial differentiation of neural progenitor cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2006b;344:431–437. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2006.03.054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwak YD, Dantuma E, Merchant S, Bushnev S, Sugaya K. Amyloid-beta Precursor Protein Induces Glial Differentiation of Neural Progenitor Cells by Activation of the IL-6/gp130 Signaling Pathway. Neurotox Res. doi: 10.1007/s12640-010-9170-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee JC, Mayer-Proschel M, Rao MS. Gliogenesis in the central nervous system. Glia. 2000;30:105–121. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1098-1136(200004)30:2<105::aid-glia1>3.0.co;2-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee VM, Andrews PW. Differentiation of NTERA-2 clonal human embryonal carcinoma cells into neurons involves the induction of all three neurofilament proteins. J Neurosci. 1986;6:514–521. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.06-02-00514.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lundkvist J, Lendahl U. Notch and the birth of glial cells. Trends Neurosci. 2001;24:492–494. doi: 10.1016/s0166-2236(00)01888-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martys-Zage JL, Kim SH, Berechid B, Bingham SJ, Chu S, Sklar J, Nye J, Sisodia SS. Requirement for presenilin 1 in facilitating lagged 2-mediated endoproteolysis and signaling of notch 1. J Mol Neurosci. 2000;15:189–204. doi: 10.1385/jmn:15:3:189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakashima K, Taga T. Mechanisms underlying cytokine-mediated cell-fate regulation in the nervous system. Mol Neurobiol. 2002;25:233–244. doi: 10.1385/MN:25:3:233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Hara BF, Fisher S, Oster-Granite ML, Gearhart JD, Reeves RH. Developmental expression of the amyloid precursor protein, growth-associated protein 43, and somatostatin in normal and trisomy 16 mice. Brain Res Dev Brain Res. 1989;49:300–304. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(89)90031-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oh SY, Ellenstein A, Chen CD, Hinman JD, Berg EA, Costello CE, Yamin R, Neve RL, Abraham CR. Amyloid precursor protein interacts with notch receptors. J Neurosci Res. 2005;82:32–42. doi: 10.1002/jnr.20625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohsawa I, Takamura C, Morimoto T, Ishiguro M, Kohsaka S. Amino-terminal region of secreted form of amyloid precursor protein stimulates proliferation of neural stem cells. Eur J Neurosci. 1999;11:1907–1913. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.1999.00601.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pleasure SJ, Collins AE, Lowenstein DH. Unique expression patterns of cell fate molecules delineate sequential stages of dentate gyrus development. J Neurosci. 2000;20:6095–6105. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.20-16-06095.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price DL, Sisodia SS, Borchelt DR. Alzheimer disease--when and why? Nat Genet. 1998;19:314–316. doi: 10.1038/1196. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price J. Glial cell lineage and development. Curr Opin Neurobiol. 1994;4:680–686. doi: 10.1016/0959-4388(94)90009-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qu T, Brannen CL, Kim HM, Sugaya K. Human neural stem cells improve cognitive function of aged brain. Neuroreport. 2001;12:1127–1132. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200105080-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Querfurth HW, Wijsman EM, St George-Hyslop PH, Selkoe DJ. Beta APP mRNA transcription is increased in cultured fibroblasts from the familial Alzheimer’s disease-1 family. Brain Res Mol Brain Res. 1995;28:319–337. doi: 10.1016/0169-328x(94)00224-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajan P, McKay RD. Multiple routes to astrocytic differentiation in the CNS. J Neurosci. 1998;18:3620–3629. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.18-10-03620.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhard C, Hebert SS, De Strooper B. The amyloid-beta precursor protein: integrating structure with biological function. Embo J. 2005;24:3996–4006. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossjohn J, Cappai R, Feil SC, Henry A, McKinstry WJ, Galatis D, Hesse L, Multhaup G, Beyreuther K, Masters CL, Parker MW. Crystal structure of the N-terminal, growth factor-like domain of Alzheimer amyloid precursor protein. Nat Struct Biol. 1999;6:327–331. doi: 10.1038/7562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandhu JK, Sikorska M, Walker PR. Characterization of astrocytes derived from human NTera-2/D1 embryonal carcinoma cells. J Neurosci Res. 2002;68:604–614. doi: 10.1002/jnr.10236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago-Garcia J, Mas-Oliva J, Innerarity TL, Pitas RE. Secreted forms of the amyloid-beta precursor protein are ligands for the class A scavenger receptor. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:30655–30661. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M102879200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitz A, Tikkanen R, Kirfel G, Herzog V. The biological role of the Alzheimer amyloid precursor protein in epithelial cells. Histochem Cell Biol. 2002;117:171–180. doi: 10.1007/s00418-001-0351-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schroeter EH, Kisslinger JA, Kopan R. Notch-1 signalling requires ligand-induced proteolytic release of intracellular domain. Nature. 1998;393:382–386. doi: 10.1038/30756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe DJ. Alzheimer’s disease: genes, proteins, and therapy. Physiol Rev. 2001;81:741–766. doi: 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.2.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selkoe DJ, Yamazaki T, Citron M, Podlisny MB, Koo EH, Teplow DB, Haass C. The role of APP processing and trafficking pathways in the formation of amyloid beta-protein. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1996;777:57–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1996.tb34401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Small DH, Nurcombe V, Reed G, Clarris H, Moir R, Beyreuther K, Masters CL. A heparin-binding domain in the amyloid protein precursor of Alzheimer’s disease is involved in the regulation of neurite outgrowth. J Neurosci. 1994;14:2117–2127. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.14-04-02117.1994. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song MR, Ghosh A. FGF2-induced chromatin remodeling regulates CNTF-mediated gene expression and astrocyte differentiation. Nat Neurosci. 2004;7:229–235. doi: 10.1038/nn1192. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sturchler-Pierrat C, Abramowski D, Duke M, Wiederhold KH, Mistl C, Rothacher S, Ledermann B, Burki K, Frey P, Paganetti PA, Waridel C, Calhoun ME, Jucker M, Probst A, Staufenbiel M, Sommer B. Two amyloid precursor protein transgenic mouse models with Alzheimer disease-like pathology. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:13287–13292. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.24.13287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svendsen CN, ter Borg MG, Armstrong RJ, Rosser AE, Chandran S, Ostenfeld T, Caldwell MA. A new method for the rapid and long term growth of human neural precursor cells. J Neurosci Methods. 1998;85:141–152. doi: 10.1016/s0165-0270(98)00126-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taga T, Fukuda S. Role of IL-6 in the neural stem cell differentiation. Clin Rev Allergy Immunol. 2005;28:249–256. doi: 10.1385/CRIAI:28:3:249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Teller JK, Russo C, DeBusk LM, Angelini G, Zaccheo D, Dagna-Bricarelli F, Scartezzini P, Bertolini S, Mann DM, Tabaton M, Gambetti P. Presence of soluble amyloid beta-peptide precedes amyloid plaque formation in Down’s syndrome. Nat Med. 1996;2:93–95. doi: 10.1038/nm0196-93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wisniewski KE, Dalton AJ, McLachlan C, Wen GY, Wisniewski HM. Alzheimer’s disease in Down’s syndrome: clinicopathologic studies. Neurology. 1985;35:957–961. doi: 10.1212/wnl.35.7.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu G, Nishimura M, Arawaka S, Levitan D, Zhang L, Tandon A, Song YQ, Rogaeva E, Chen F, Kawarai T, Supala A, Levesque L, Yu H, Yang DS, Holmes E, Milman P, Liang Y, Zhang DM, Xu DH, Sato C, Rogaev E, Smith M, Janus C, Zhang Y, Aebersold R, Farrer LS, Sorbi S, Bruni A, Fraser P, St George-Hyslop P. Nicastrin modulates presenilin-mediated notch/glp-1 signal transduction and betaAPP processing. Nature. 2000;407:48–54. doi: 10.1038/35024009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhuo L, Sun B, Zhang CL, Fine A, Chiu SY, Messing A. Live astrocytes visualized by green fluorescent protein in transgenic mice. Dev Biol. 1997;187:36–42. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1997.8601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]