Abstract

OBJECTIVES

The objective of this study is to elucidate the mechanism of TGF-β1 over-expression in prostate cancer cells.

METHODS

Malignant (PC3, DU145) and benign (RWPE1, BPH1) prostate epithelial cells were used. Phosphatase activity was measured using a commercial kit. Recruitment of the regulatory subunit, Bα, of protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A-Bα) by TGF-β type I receptor (T RI) was monitored by co-immunoprecipitation. Blockade of TGF-β1 signaling in cells was accomplished either by using TGF-β neutralizing monoclonal antibody or by transduction of a dominant negative TGF-β type II receptor retroviral vector.

RESULTS

Basal levels of TGF-β1 in malignant cells were significantly higher than those in benign cells. Blockade of TGF-β signaling resulted in a significant decrease in TGF-β1 expression in malignant cells, but not in benign cells. Upon TGF-β1 treatment (10 ng/ml), TGF-β1 expression was increased in malignant cells, but not in benign cells. This differential TGF-β1 auto-induction between benign and malignant cells correlated with differential activation of extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK). Following TGF-β1 treatment, the activity of serine/threonine phosphatase and recruitment of PP2A-Bα by TβRI increased in benign cells, but not in malignant cells. Inhibition of PP2A in benign cells resulted in an increase in ERK activation and in TGF-β1 auto-induction following TGF-β1 (10 ng/ml) treatment.

CONCLUSIONS

These results suggest that TGF-β1 over-expression in malignant cells is caused, at least in part, by a runaway of TGF-β1 auto-induction through ERK activation due to a defective recruitment of PP2A-Bα by TβRI.

Keywords: malignant cell, benign cell, transforming growth factor-β, extracellular signal-regulated kinase, auto-induction, protein phosphatase 2A

Introduction

Many cancer cells, including prostate cancer, are able to over-express TGF-β1.1 Aside from the growth inhibitory effect, TGF-β1 can also stimulate extracellular matrix production, promote angiogenesis, facilitate invasion, and suppress the host immune system.2 Thus, cancer cells may circumvent the suppressive effects of TGF-β1, especially for aggressive cancer cells. Therefore, for these cancer cells, it is possible that approaches to disrupt the TGF-β1 over-expression may offer a strategy to suppress the aggressive phenotype. To achieve this goal, we must first understand the mechanism through which these tumor cells produce more TGF-β1 than their benign counterparts. Yet, little is known about the regulation of TGF-β1 over-expression. The most potent inducer of TGF-β1 is itself.3 It has been shown that TGF-β1 can induce its own mRNA transcription and protein synthesis in various cells.4–8

The exact mechanism of TGF-β1 auto-induction is still not clear. Previous investigations showed that extracellular signal-regulated kinase (ERK) and c-jun N-terminal kinase (JNK) are involved in TGF-β-induced AP-1complex, which contributes to TGF-β1 auto-induction.5 Further, Smad3/Smad4 takes part in the TGF-β1 mRNA transcription,9 while p38 pathway influences de novo synthesis of TGF-β1.9 Among these pathways, ERK activation by TGF-β1 has been shown to be essential for TGF-β1 auto-induction.10 However, the effect of TGF-β1 on ERK activation remains controversial and seems to be dependent on cellular context. Many studies described that TGF-β1 could activate ERK;11–15 while others reported that TGF-β1 inactivated or had no effect on ERK.16–20 Therefore it is reasonable to deduce that TGF-β1 auto-induction through ERK activation is also cellular context dependent. The aim of the present study is to elucidate whether there is a difference in TGF-β1 auto-induction between malignant and benign prostate epithelial cells and whether TGF-β1 auto-induction contributes to TGF-β1 over-expression in cancer cells.

Material and Methods

Cell lines, reagents, and retroviral vector transduction

Human prostate cancer cell lines, PC3, DU145, and the benign human prostate epithelial cell line, RWPE1, were obtained from American Type Culture Collection (Manassas VA). Another human benign prostate epithelial cell line, BPH1, was kindly provided by Dr. Simon Hayward of Vanderbilt University. All cells, unless otherwise specified, were routinely maintained in culture medium RPMI-1640 with 10% FBS and kept in a 37°C, 5% CO2 incubator. TGF-β1 was obtained from R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). The MEK1/2 inhibitor, UO126, was obtained from Cell Signaling (Danvers, MA). The TGF-β neutralizing monoclonal antibody (1D11) and the isotype control IgG Ab (13C4) were kindly provided by the Genzyme Corporation. (Framingham, MA).

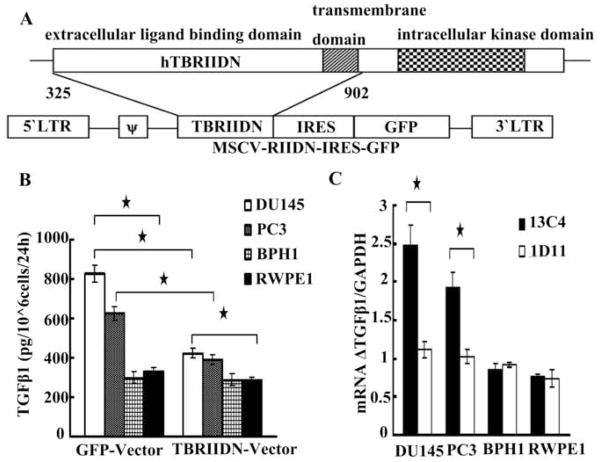

In indicated experiments, cells were transduced with TGF-β Receptor II dominant negative (TβRIIDN) retroviral vector or the GFP vector as previously described.21,22 Figure 1A is a schematic diagram of the murine stem cell virus (MSCV) retroviral construct containing a truncated sequence of the human T RIIDN, lacking the intracellular kinase signaling domain, which was cloned into the pMig-internal ribosomal entry sequence (IRES)-GFP vector. The control construct (not shown) contained the GFP vector only and without the TβRIIDN sequences (325–902 bp). The transduction efficiency was >90%.

Fig. 1.

Panel A, schematic diagram of the murine stem cell virus (MSCV) retroviral construction. A truncated sequence of the human T RIIDN, lacking the intracellular kinase signaling domain, was cloned into the pMig-internal ribosomal entry sequence (IRES)-GFP vector. The control construction (not shown) contained the GFP vector only and without the TβRIIDN sequences (325–902 bp). Panel B, cells infected with T RIIDN or GFP vector were routinely cultured to 50% confluence and then rinsed with PBS thoroughly, cultured in serum free medium for 24 more hours. TGF-β1 level in the culture medium was detected by using ELISA. Panel C, cells at 50% confluence were rinsed with PBS thoroughly and cultured in serum free medium for 24h and then 100ug/ml 13C4 or 1D11 was added. 12h later, total RNA was extracted and the ratio between TGF-β1 and GAPDH mRNA (mRNA ΔTGF-β1/GAPDH) was detected by qRT-PCR. Asterisks (*) denote that the p value is less than 0.05. Horizontal bars cover the groups that are being compared for statistical significance.

Enzyme-linked Immunosorbent Asssy (ELISA)

Culture medium was collected and centrifuged at 1000g for 10 min, and viable cells were counted. The concentration of TGF-β1 was detected by a human TGF-β1 ELISA kit (R&D Systems) following the manufacturer’s instructions as described previously22 and was expressed as pg/ml/106 cells/24h.

Immunoprecipitation

Pierce Crosslink Immunoprecipitation kit (Pierce, Rochford, IL) was used for protein immunoprecipitation following the manufacturer’s recommendations. Briefly, cells were harvested following the specified treatment with IP Lysis/Wash buffer plus 1% protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO). Protein concentration was assayed and adjusted to 1 mg/ml with the lysis/wash buffer. An aliquot of 600 ul of cell lysates was pre-cleared by using 20 ul Pierce Control Agarose Resin. TGF-β type I receptor (T RI) antibody (5 ug) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, CA) was bound to 20 ug of Pierce A/G Plus Agarose in a Pierce Spin Column. After incubation for 60 min in room temperature, the antibody and agarose was crosslinked by DSS supplied by the kit. Pre-cleared lysate was immunopreciptated by the crosslinked antibody and Agarose mixture for overnight on 4°C. Control agarose resin in the kit was used as a negative control when western-blot analysis was conducted.

Western Blot Analysis

Cell lysates were prepared by using cell lysis buffer (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA) supplemented with 1 mM PMSF and 1% protease inhibitor cocktail (Sigma-Aldrich) or eluted from the protein immunoprecipitation. Western blot analysis was performed as described previously.18 The following antibodies were used: p-ERK1/2 (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA), ERK1/2 (Cell Signaling), PP2A Bα antibody (Cell Signaling), Goat Anti-mouse HRP-labeled secondary antibody (Bio-Rad Laboratories Hercules, CA) and Goat anti rabbit HRP-labeled secondary antibody (Bio-Rad Laboratories).

Quantitative Reverse Transcriptase Polymerase Chain Reaction (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted by using TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) and digested with RNase free DNase I (Invitrogen) following the manufacturer’ recommendations. cDNA was synthesized by using Superscript™ first-stand synthesis system (Invitrogen). QRT-PCR was performed by using following primers specific for TGF-β1 (forward 5′-CCTTTCCTGCTTCTCATGGC-3′; reverse 5′-ACTTCCAGCCGAGGTCCTTG-3′), GAPDH (forward 5′-CAC CAC CAT GGA GAA GGC TGG-3′, reverse 5′-GAA GTC AGA GGA GAC CAC CTG-3′). The iQ SYBR Green Supermix (BioRad Laboratories) on iCycler iQ system was conducted according to the manufacturer’s protocol. All qRT-PCR reactions were performed in triplicate for each cDNA sample.

Phosphatase Activity Assay

Non-radioactive Serine/Threonine Phosphatase Assay System (Promega, Madison, WI) was used according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Cell lysates were prepared from 107 cells in 0.5 ml lysis buffer (10 mM Tris, pH 7.5; 0.1% Triton X-100; 140 mM NaCl; 1 mM PMSF; protease inhibitor cocktail) and passed through Sephadex G-25 columns to remove free phosphate. The protein concentration of the supernatant was determined (Pierce). The activity of the extract (corresponding to 2 μg protein) was measured in an enzyme-specific reaction buffer (250 mM imidazole pH 7.2; 1 mM EGTA, 0.1% β-mercaptoethanol; 0.5 mg/mL BSA) with 1 mM phosphopeptide and Molybdate Dye/Additive incubation. Results of colorimetric optical density (OD) were read at 620 nm. Calculations were performed from parallel measurements of standard free phosphate reactions. Similarly, protein tyrosine phosphatase activity was assayed by using the universal Tyrosine Phosphatase Assay Kit (Promega) according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Statistics

All experiments were repeated at least three times. Descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation) was applied for data analysis. Analysis of variance test (multi groups) or Student’s t test (two groups) was applied for evaluating significance. A p value equal to or greater than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Endogenous TGF-β1 and its auto-induction

As indicated in Figure 1B, the basal level of TGF-β1 in DU145 and PC3 was significantly higher than that in BPH1 and RWPE1. These results verified the well-documented phenomenon that prostate cancer cells secrete more TGF-β1 than that of benign cells.1 When cells were rendered insensitive to TGF-β1 by transduction with the T RIIDN retroviral vector, the difference in TGF-β1 level between malignant and benign cells, though still existed, was reduced when compared with that of the GFP vector controls. Following blockade of TGF-β1 signaling by T RIIDN, the endogenous TGF-β1 level deceased significantly in DU145 and PC3, while the level did not change significantly in BPH1 and RWPE1. To validate the above result, we inhibited endogenous TGF-β1 by a neutralizing monoclonal antibody to TGF-β (1D11) for 12h and we determined the level of TGF-β1 mRNA. As 1D11 is able to neutralize all three TGF-β isoforms (TGF-β1, 2, 3), Fig. 1C showed that treatment with 1D11 resulted in a significant reduction in the basal level of TGF-β1 mRNA in malignant cells but not in benign cells. These results suggest that TGF-β1 auto-induction contributed, at least in part, to the high level of TGF-β1 expression in malignant cells, but there was no TGF-β1 auto-induction in benign cells under the basal condition.

Auto-induction with exogenous TGF-β1

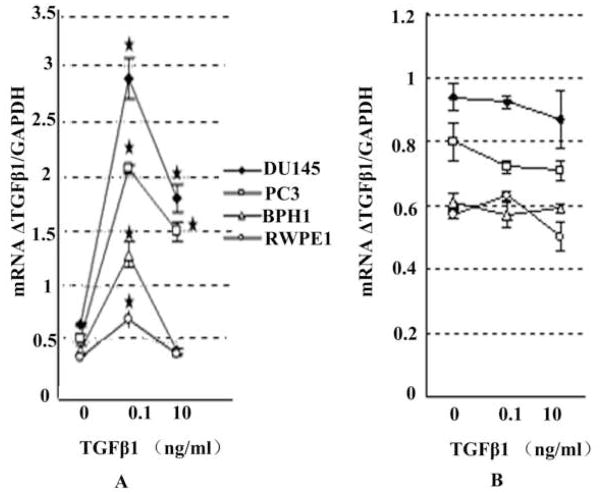

Reports in the literature have shown that the phenomenon of TGF-β auto-induction with exogenous TGF-β1 in many cell types.8 The results of the present study (Figure 2A) demonstrated that at a low dose (0.1ng/ml) of exogenous TGF-β1, it induced TGF-β1 mRNA in both benign and malignant prostate cells; however, at a high dose (10ng/ml), auto-induction occurred only in malignant cells. It was well documented that this increase in mRNA was consistent with an increase in de novo TGF-β1 synthesis.8, 9

Fig. 2.

TGF-β1 mRNA transcription induced by exogenous TGF-β1. Panel A, cells at 50% confluence were rinsed with PBS thoroughly and cultured in serum free medium for 12h with or without exogenous TGF-β1 and then TGF-β1 and GAPDH mRNA level was detected. Panel B, cells were treated as above, but 2 hours before TGF-β1 administration, 5 uM UO126 was added into the serum free medium. ERK activation was inhibited thoroughly by this dose of UO126 (not shown). Asterisks (*) denote that the p value is less than 0.05 compared with the control.

The impact of ERK activation on TGF-β1 auto-induction

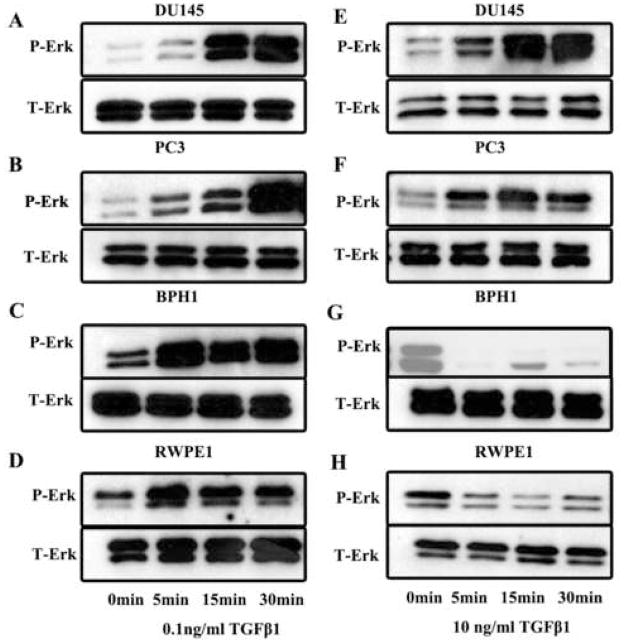

Following inhibition of ERK activation with UO126 (Figure 2B), auto-induction of TGF-β1 in these four cell lines were abrogated regardless the dosage of TGF-β1 used in the experiment. This observation was consistent with the study by Zhang and associates, who reported that ERK activation was linked to TGF-β1 auto-induction.10 Interestingly, although following a low dose of TGF-β1 stimulation, a rapid ERK activation (p-ERK) was observed in both malignant and benign cells (Figure 3A–3D), at a high dose of TGF-β1, a rapid inactivation of ERK occurred in benign cells (Figure 3G and 3H) but the rapid ERK activation continued in malignant cells (Figure 3E and 3F). This differential activation of ERK between benign and malignant prostate epithelial cells coincided with the differential auto-induction of TGF-β1.

Fig. 3.

Western blot analysis of the effect of 0.1ng/ml (left) or 10ng/ml (right) TGF-β1 on expression of phosphorylated Erk (p-Erk), total Erk (T-Erk) in DU145 (panel A and E), PC3 (panel B and F), BPH1 (panel C and G), and RWPE1 (panel D and H) over a period of 30 minutes. Cells at 50% confluence were starved with serum-free medium for overnight and then recovered with medium containing 10% fetal bovine serum for 2 hours prior to TGF-β1 treatment. Upon detection of p-Erk, the membrane was reprobed for T-Erk.

Mechanism for ERK activation change induced by TGF-β1

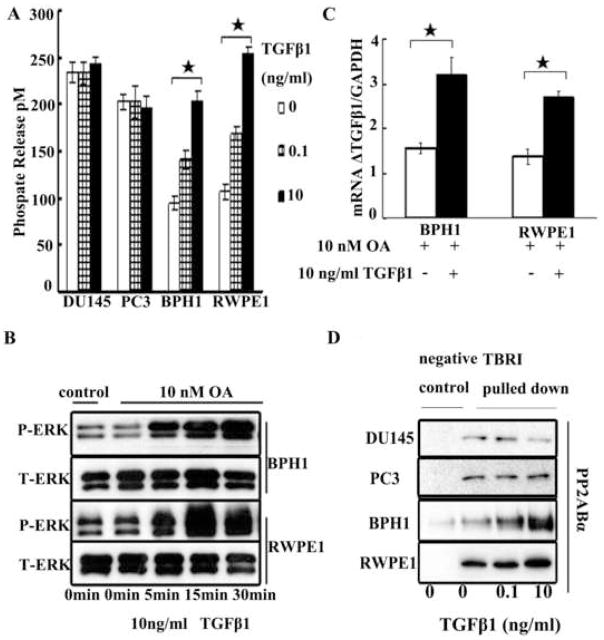

It is known that TGF-β1 activates ERK through a direct phosphorylation of ShcA, which sets off the well characterized ShcA-Grb2-Sos-Ras-raf-Mek-ERK signal cascade.11–14 Our results in benign cells suggested that, aside from the above positive pathway, there should also be a TGF-β1-mediated negative regulation of ERK activation. The possible candidate of this negative pathway is most likely protein phosphatase. There are mainly two classes of protein phosphatases: Serine/threonine protein phosphatases and protein tyrosine phosphatases (PTP). When PTP was measured, the enzymatic activity did not change significantly in these four cell lines with TGF-β1 treatment (data not shown). However, when the serine/threonine phosphatase was measured, although there was no significant change in enzymatic activity in malignant cells, the phosphatase activity increased significantly in benign cells following TGF-β1 treatment (Figure 4A). This increase was in a dose dependent manner. This finding coincided with previous study by Sebestyen and co-workers.20 Since PP2A is a main serine/threonine phosphatase and it is known that PP2A activity can be induced by TGF-β1, leading to the deactivation of ERK,23, 24 it is likely that PP2A may be the candidate phosphatase in the present system. Okadaic acid (OA) is an inhibitor of serine/threonine phosphatases, 10 nM of which will inhibit the PP2A but not sufficient to inhibit other phosphatases.25 In the present study, treatment of OA (10 nM) to benign cells elicited the TGF-β1 mediated ERK activation at the high dose (10 ng/ml) of TGF-β1 (Figure 4B). Interestingly, following ERK activation, TGF-β1 auto-induction was observed (Figure 4C). This finding validated the observation that, in benign cells, TGF-β1 enhanced the PP2A activity, as reflected by the observed increase in serine/threonine phosphatase activity, resulting in ERK inactivation.

Figure 4.

Panel A, effect of varying dosages of TGF-β1 (0, 0.1 and 10 ng/ml) on activity of protein serine/threonine phosphatases at 15 minutes following the TGF-β1 treatment. Panel B: okadaic acid (OA) (10 nM) was added 2 hours before TGF-β1 stimulation and then TGF-β induced P-ERK change was detected in benign cells. To measure the impact of OA itself on PERK, cells without OA treatment were used as control. Panel C: effect of OA on the high dose of TGF-β1 auto-induction in benign cells. OA was added 2 hours before TGF-β1 treatment and then cells were cultured for another 12 hours. Panel D: Effect of varying dosages of TGF-β1 on immunoprecipitation with antibody against T RI. Reaction was stopped at 15 minutes after TGF-β1 treatment. PP2A-Bα was probed by western blot analysis in PC3, DU145, BPH1, and RWPE1 cells. Asterisks (*) denote that the p value is less than 0.05. Horizontal bars cover the groups that are being compared for statistical significance.

PP2A has three subunits: scaffold subunit A, regulatory subunit B, and catalytic subunit C. The PP2A core enzyme, consisting of A and C subunits, must interact with the regulatory subunit B to form a heterotrimeric holoenzyme to obtain the function of de-phoshorylation to the substrate. It is known that there is a physical interaction between the activated TβRI and PP2A-Bα, a WD-40 repeat regulatory subunit of PP2A and PP2A activity increases after this interaction.26 To investigate whether there was physical interaction between PP2A-Bα and TβRI in these four cell lines, we performed an immunoprecipitation experiment using antibody to TβRI and probed for PP2A Bα in the precipitates by western blot analysis. Indeed, there was an increase in PP2A-Bα with TβRI pull-down following TGF-β1 treatment in a dose dependent manner in BPH1 and RWPE1 cells (Figure 4D). However, TGF-β1 induced PP2A Bα recruitment by TβRI was not observed in DU145 or PC3 cells, suggesting a defect in recruitment of PP2A Bα by TβRI. The total level of PP2A Bα protein in the total lysate of these four cell lines, as determined by western-blot analysis, was abundant and was not significantly different with different doses of TGF-β1 treatment (data not shown).

Comment

TGF-β1 is a pleiotropic cytokine which can mediate a wide spectrum of cellular effects through a variety of signaling pathways.27 It is a well-known feature that sometimes different pathways cooperate to orchestrate a certain cellular effect. Here we demonstrate both ERK and PP2A play roles in TGF-β1 auto-induction in benign prostate cells, while in malignant prostate cells the TGF-β1 induced PP2A pathway was defective. Since the antibody used in this study detects the tyrosine phosphorylated site of ERK, therefore, ERK cannot be a direct substrate of PP2A here. Further studies are needed to investigate how PP2A exactly deactivates ERK.

Since the physical and functional interaction between TβRI and PP2A Bα depends on the integrity and activation of both TβRI and TβRII,26 while functional and somatic mutations of TβRI and TβRII in prostate cancer have been demonstrated before,1 further studies should be conducted to determine whether the defective PP2A recruitment by TβRI in prostate malignant cells is the result of mutations in these receptors.

Although several hypotheses have been proposed to justify the high level of TGF-β1 over-expression in malignant cells,2,28 a plausible mechanism remains elusive. In the present study, we observed a differential TGF-β1 signaling pathway between benign and malignant cells which leads to a differential auto-induction of TGF-β1 through a defective PP2A recruitment by TβRI in malignant cells. It should be pointed out that, under special conditions, such as low TGF-β1 microenvironment, benign cells can also mediate TGF-β1 auto-induction. Perhaps, this is a feedback mechanism in an effort to maintain homeostasis in benign cells. Once the level of TGF-β1 reaches a certain threshold in the benign environment, a sufficient level of PP2A will be recruited by TβRI, resulting in inactivation of ERK and termination of TGF-β1 auto-induction. However, in cancer cells, due to the defective recruitment of PP2A by TβRI, the auto-induction of TGF-β1 is runaway and constitutes a vicious cycle leading to over-expression of TGF-β1 and tumor progression. It is known that the average TGF-β1 in human serum 29 and semen 30 is higher than 10ng/ml. The high dose of TGF-β1 used in the present study that induced an auto-induction of TGF-β1 in malignant cells but not in benign cells may have physiological significance. Further studies should be conducted to determine whether this defective recruitment of PP2A by TβRI is a widespread phenomenon among most malignant cells rather than limited to the two cancer cell lines used in the present study. If this phenomenon is validated in other malignant cells, it may offer a novel approach to prevent tumor invasion and tumor progression.

Conclusions

The present results indicate that a low level of TGF-β1 can auto-induce itself in both benign and malignant prostate epithelial cells. However, in benign cells, recruitment of PP2A by T RI provides a mechanism to terminate the auto-induction at high dose of TGF-β1, while in malignant cells, due to a defective recruitment of PP2A by TβRI, TGF-β1 auto-induction is runaway, which contributes to the TGF-β1 over-expression in these cells.

Acknowledgments

Grant sponsor: This study was supported, in part, bya State Scholarship Fund (file No. 2008658002) from the China Scholarship Council, a gift from Mr. Fred Turner, The Prostate Cancer Research Fund of the NorthShore University HealthSystem, NIH P50CA90386, and DOD PC080262.

We thank Dr. Simon Hayward of the Vanderbilt University for kindly providing the BPH1 cell line. Neutralizing monoclonal antibody against TGF-β (1D11) and the isotype control IgG (13C4) were kindly provided by the Genzyme Corporation.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest: The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Lee C, Sintich SM, Mathews EP, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta in benign and malignant prostate. Prostate. 1999;39:285–290. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0045(19990601)39:4<285::aid-pros9>3.0.co;2-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Massague J. TGFbeta in Cancer. Cell. 2008;134:215–230. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.07.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pardoux C, Derynck R. JNK regulates expression and autocrine signaling of TGF-beta1. Mol Cell. 2004;15:170–171. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2004.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kelley J, Shull S, Walsh JJ, et al. Auto-induction of transforming growth factor-beta in human lung fibroblasts. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 1993;8:417–424. doi: 10.1165/ajrcmb/8.4.417. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim SJ, Angel P, Lafyatis R, et al. Autoinduction of transforming growth factor beta 1 is mediated by the AP-1 complex. Mol Cell Biol. 1990;10:1492–1497. doi: 10.1128/mcb.10.4.1492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Li J, Tripathi BJ, Chalam KV, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta 1 and -beta 2 positively regulate TGF-beta 1 mRNA expression in trabecular cells. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1996;37:2778–2782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin RY, Sullivan KM, Argenta PA, et al. Exogenous transforming growth factor-beta amplifies its own expression and induces scar formation in a model of human fetal skin repair. Ann Surg. 1995;222:146–154. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199508000-00006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van Obberghen-Schilling E, Roche NS, Flanders KC, et al. Transforming growth factor beta 1 positively regulates its own expression in normal and transformed cells. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:7741–7746. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Annes J, Vassallo M, Munger JS, et al. A genetic screen to identify latent transforming growth factor beta activators. Anal Biochem. 2004;327:45–54. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2003.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang M, Fraser D, Phillips A. ERK, p38, and Smad signaling pathways differentially regulate transforming growth factor-beta1 autoinduction in proximal tubular epithelial cells. Am J Pathol. 2006;169:1282–1293. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2006.050921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aoki H, Ohnishi H, Hama K, et al. Autocrine loop between TGF-beta1 and IL-1beta through Smad3- and ERK-dependent pathways in rat pancreatic stellate cells. Am J Physiol Cell Physiol. 2006;290:C1100–1108. doi: 10.1152/ajpcell.00465.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen G, Khalil N. TGF-beta1 increases proliferation of airway smooth muscle cells by phosphorylation of map kinases. Respir Res. 2006;7:2. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-7-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo B, Inoki K, Isono M, et al. MAPK/AP-1-dependent regulation of PAI-1 gene expression by TGF-beta in rat mesangial cells. Kidney Int. 2005;68:972–984. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1755.2005.00491.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee MK, Pardoux C, Hall MC, et al. TGF-beta activates Erk MAP kinase signalling through direct phosphorylation of ShcA. EMBO J. 2007;26:3957–3967. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601818. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nickl-Jockschat T, Arslan F, Doerfelt A, et al. An imbalance between Smad and MAPK pathways is responsible for TGF-beta tumor promoting effects in high-grade gliomas. Int J Oncol. 2007;30:499–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dixon M, Agius L, Yeaman SJ, et al. Inhibition of rat hepatocyte proliferation by transforming growth factor beta and glucagon is associated with inhibition of ERK2 and p70 S6 kinase. Hepatology. 1999;29:1418–1424. doi: 10.1002/hep.510290516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giehl K, Seidel B, Gierschik P, et al. TGFbeta1 represses proliferation of pancreatic carcinoma cells which correlates with Smad4-independent inhibition of ERK activation. Oncogene. 2000;19:4531–4541. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1203806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luo X, Zhang Q, Liu V, et al. Cutting edge: TGF-beta-induced expression of Foxp3 in T cells is mediated through inactivation of ERK. J Immunol. 2008;180:2757–2761. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.180.5.2757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramesh S, Qi XJ, Wildey GM, et al. TGF beta-mediated BIM expression and apoptosis are regulated through SMAD3-dependent expression of the MAPK phosphatase MKP2. EMBO Rep. 2008;9:990–997. doi: 10.1038/embor.2008.158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sebestyen A, Hajdu M, Kis L, et al. Smad4-independent, PP2A-dependent apoptotic effect of exogenous transforming growth factor beta 1 in lymphoma cells. Exp Cell Res. 2007;313:3167–3174. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2007.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shah AH, Tabayoyong WB, Kimm SY, et al. Reconstitution of lethally irradiated adult mice with dominant negative TGF-beta type II receptor-transduced bone marrow leads to myeloid expansion and inflammatory disease. J Immunol. 2002;169:3485–3491. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.169.7.3485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Q, Helfand BT, Jang TL, et al. Nuclear factor-kappaB-mediated transforming growth factor-beta-induced expression of vimentin is an independent predictor of biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:3557–3567. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Dent P, Jelinek T, Morrison DK, et al. Reversal of Raf-1 activation by purified and membrane-associated protein phosphatases. Science. 1995;268:1902–1906. doi: 10.1126/science.7604263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Junttila MR, Li SP, Westermarck J. Phosphatase-mediated crosstalk between MAPK signaling pathways in the regulation of cell survival. FASEB J. 2008;22:954–965. doi: 10.1096/fj.06-7859rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.MacKintosh C, Beattie KA, Klumpp S, et al. Cyanobacterial microcystin-LR is a potent and specific inhibitor of protein phosphatases 1 and 2A from both mammals and higher plants. FEBS Lett. 1990;264:187–192. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(90)80245-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Griswold-Prenner I, Kamibayashi C, Maruoka EM, et al. Physical and functional interactions between type I transforming growth factor beta receptors and Balpha, a WD-40 repeat subunit of phosphatase 2A. Mol Cell Biol. 1998;18:6595–6604. doi: 10.1128/mcb.18.11.6595. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Derynck R, Zhang YE. Smad-dependent and Smad-independent pathways in TGF-beta family signalling. Nature. 2003;425:577–584. doi: 10.1038/nature02006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hata A. TGFbeta signaling and cancer. Exp Cell Res. 2001;264:111–116. doi: 10.1006/excr.2000.5140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wolff JM, Fandel T, Borchers H, et al. Transforming growth factor-beta1 serum concentration in patients with prostatic cancer and benign prostatic hyperplasia. Br J Urol. 1998;81:403–405. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robertson SA. Seminal plasma and male factor signalling in the female reproductive tract. Cell Tissue Res. 2005;322:43–52. doi: 10.1007/s00441-005-1127-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]