Abstract

Immunoreactivity for both processed and unprocessed forms of chromogranin A (CGA) was examined, using an antibody recognizing the WE14 epitope, among terminal fields and cell bodies of anatomically defined GABAergic, glutamatergic, cholinergic, catecholaminergic, and peptidergic cell groups in the rodent central nervous system. CGA is ubiquitous within neuronal cell bodies, with no obvious anatomical or chemically-coded subdivision of the nervous system in which CGA is not expressed in most neurons. CGA expression is essentially absent from catecholaminergic terminal fields in the CNS, suggesting a relative paucity of large dense-core vesicles in CNS compared to peripheral catecholaminergic neurons. Extensive synaptic co-localization with classical transmitter markers is not observed even in areas such as amygdala, where CGA fibers are numerous, suggesting preferential segregation of CGA to peptidergic terminals in CNS. Localization of CGA in dendrites in some areas of CNS may indicate its involvement in regulation of dendritic release mechanisms. Finally, the ubiquitous presence of CGA in neuronal cell somata, especially pronounced in GABAergic neurons, suggests a second non-secretory vesicle-associated function for CGA in CNS. We propose that CGA may function in the CNS as a prohormone and granulogenic factor in some terminal fields, but also possesses as-yet unknown unique cellular functions within neuronal somata and dendrites.

Keywords: GABAergic, Glutamatergic, WE14, Neurosecretion, chemical coding, Neurotransmission

1. Introduction

CGA has multiple functions in neurons and neuroendocrine cells. CGA forms complexes with ATP and catecholamines believed to function in catecholamine storage in secretory granules [1–6]. CGA is the precursor for the bioactive peptides pancreastatin [7,8], the vasostatins [9], and catestatin [10–12]. CGA was demonstrated to be capable of inducing large dense-core vesicles when overexpressed in non-neuroendocrine cells, and to be involved in regulated sorting, secretion, and granulogenesis in neuroendocrine cells [13–15]. Although several granins may be involved in the generation of secretory vesicles in vivo [16], CGA-deficient mice lack physiologically appropriate diurnal regulation of catecholamine secretion from the adrenal medulla, demonstrating the importance of chromogranin A for generation of large dense-core vesicles (LDCVs) within the regulated secretory pathway in peripheral neuroendocrine cells [11,16].

Although much is known about CGA localization [17–24], function in LDCV granulogenesis [13–15], and prohormone function [7,12,25] in endocrine, neuroendocrine, and peripheral neuronal systems, its role in the CNS is less clear. The distribution of CGA was first described by Winkler et al. in the sheep and rodent brain [26,27] as not restricted to a specific type of neuronal cell or neural circuit. In situ hybridization histochemical methodology revealed the widespread presence of CGA and its mRNA in brain [28,29], leading to the demonstration that virtually all CNS neuronal cell groups throughout the brain and spinal cord expressed CGA, and the concept of CGA as a pan-neuronally expressed protein in the rat central and peripheral nervous systems [30]. Subsequently, Woulfe et al. confirmed the pan-neuronal expression of CGA mRNA in rat brain, and pointed out that differential distribution of CGA immunoreactivity is highly dependent on the antibody used to visualize the CGA protein and its processed peptides [31].

The role of CGA in sequestration of biogenic amines in LDCVs within the CNS, and indeed the subcellular localization of CGA within different types of chemically defined neuronal systems in the brain, has been relatively neglected given its importance peripherally. CGA’s role as a prohormone has also not been highly investigated in the CNS. This is of particular interest given recent evidence for the dominant role of cathepsin L in prohormone processing in the CNS [32] and in PC12 cells [33], rather than the classical prohormone convertase 1 that processes CGA in endocrine cells [34]. Despite its ubiquity in the CNS, chromogranin A levels are significantly lower than in peripheral endocrine tissues [18,27], and exist at a higher ratio of the proteogly-canated form of the protein [27]. Indeed other roles for CGA in CNS besides either prohormone or granulogenic ones have been proposed, including its function as a molecular chaperone for misfolded superoxide dismutase, important in prevention of spinal motor neuron degeneration as occurs in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis [35].

It was our intention in the present investigation, to employ an antibody directed towards the WE14 epitope of CGA, which recognizes this epitope in both processed peptide and intact CGA [36,37], to investigate the following questions about CGA chemical neuroanatomy in the brain. First, is CGA present in both fibers and cell bodies throughout the CNS? Second, is CGA in nerve terminals associated primarily with any of the classical neurotransmitter systems or with neuropeptide projections? Third, is CGA subcellular distribution in known neurotransmitter systems consistent with a role besides that of an LDCV-associated protein/peptide? These questions were examined initially in mouse brain, so that the chromogranin A-deficient brain could be used as a control for absolute specificity of CGA epitope staining using the WE14 antibody.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Animals

Adult male mice of the C57Bl/6 strain and CGA knock-out mice (knock-out allele of Mahapatra et al., 2005; back-crossed onto C57Bl/6 strain, N6–12) and adult male Wistar rats were terminally anesthetized, perfused transcardially with Bouin Hollande fixative or immersion-fixed, and the brain and other tissues removed. All tissues were postfixed in Bouin Hollande for up to 3 h. Bouin Hollande fixative contained 4% (w/v) picric acid, 2.5% (w/v) cupric acetate, 3.7% (v/v) formaldehyde, and 1% (v/v) glacial acetic acid. Following fixation, the tissues were extensively washed in 70% isopropanol, dehydrated, cleared with xylene, and embedded in paraffin. Seven micron thick sections were cut on a Leica microtome, mounted on gelatin-coated slides and stored until immunocytochemical staining was performed.

2.2. Single and double immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry (IHC) was carried out on deparaffinized sections using an antigen retrieval technique and visualized enzymatically with 3,3-diaminobenzidine (DAB; Sigma, Deisenhofen, Germany), enhanced by addition of ammonium nickel sulfate (Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland), or visualized by immunofluorescence, as previously described [38]. Tyramide signal amplification (TSA) was used to increase sensitivity for both single immunohistochemistry and for double immunofluorescence according to the manufacturer’s instructions (catalog no. SAT700; PerkinElmer Life and Analytical Sciences, Boston, MA).

2.3. Primary antibodies

CGA immunoreactivity was visualized with polyclonal rabbit WE14 antibody [30]. Cholinergic phenotypes were detected by our polyclonal rabbit (80259) and goat (1624) antibodies [39,40]. Monoaminergic traits were visualized with a rabbit polyclonal antibody (W1–2) that specifically detected mouse vesicular monoamine transporter 2 (VMAT2) and a sheep polyclonal antibody against tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) from Chemicon [38,41]. In addition, a polyclonal guinea-pig anti-VMAT2 antibody (Chemicon) was used that, however, did not recognize mouse VMAT2 but reacted with rat VMAT2. This antibody was used for double immunofluorescence analysis of CGA and VMAT2 in rat brain. Pituitary adenylate cyclase-activating polypeptide (PACAP) was stained with the rabbit anti-PACAP-38 (Progen, Heidelberg) [42]. Neuropeptide Y (NPY) was visualized with polyclonal sheep anti-NPY (Auspep, Parkville, Australia) [41]. Glutamatergic synapses were stained with polyclonal guinea-pig antibodies against the vesicular glutamate transporter isoforms VGluT1 and VGluT2 [43]. For the visualization of GABAergic synapses we used a rabbit polyclonal antibody against the vesicular inhibitory amino acid transporter (VIAAT) (W1–4) also referred to as the vesicular GABA transporter (VGAT) [44].

2.4. Single immunohistochemistry

Sections were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated through a graded series of isopropanol. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked by incubation in methanol/0.3% H2O2 for 30 min and antigen retrieval achieved by incubation in 10 mM sodium citrate buffer (pH 6.0) at 92–95 °C for 15 min. Non-specific binding sites were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) in 50 mM phosphate buffered saline (PBS, pH 7.45) for 30 min, followed by an avidin–biotin blocking step (Avidin–Biotin Blocking Kit, Boehringer, Ingelheim, Germany) for 40 min. Primary antibodies were applied in 1% BSA/PBS and incubated at 16 °C overnight followed by 2 h at 37 °C. After several washes in distilled water followed by rinsing in PBS, the sections were incubated for 45 min at 37 °C with species-specific biotinylated secondary antibodies (Dianova, Hamburg, Germany), diluted 1:200 in 1% BSA/PBS, washed again several times and incubated for 30 min with avidin–biotin–peroxidase complex reagents (Vectastain Elite ABC kit; Vector Laboratories, Burlingame, CA). Immunoreactions were visualized by an 8 min incubation with 3,3-diaminobenzidine (DAB, Sigma Aldrich, Deisenhofen, Germany), enhanced by the addition of 0.08% ammonium nickel sulfate (Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland), which resulted in a dark blue staining. After three 5 min washes in distilled water, the sections were dehydrated through a graded series of isopropanol, cleared in xylene and finally mounted under coverslips. Digital bright-field pictures were taken with an Olympus AX70 microscope (Olympus Optical, Hamburg, Germany), equipped with a SPOT RT Slider Camera and SPOT Image Analyses software (Version 3.4; Diagnostic Instruments Inc., Seoul, Korea).

2.5. Double immunofluorescence

After deparaffinization and blocking procedures, appropriate combinations of two primary antibodies raised in different donor species were co-applied in 1% BSA/PBS and incubated overnight at 4 °C, followed by 2 h at 37 °C. After extensive washing in distilled water followed by PBS, immunoreactions for the first primary antibody were visualized with species-specific secondary antibodies labeled with Alexa Fluor 647 (MoBiTec, Göttingen, Germany), diluted 1:200 in 1% BSA/PBS. The second primary antibody was visualized by a two-step procedure including species-specific biotinylated secondary antisera (Dianova), diluted 1:200 in 1% BSA/PBS followed by streptavidin conjugated with Alexa Fluor 488, diluted 1:100 in 1% BSA/PBS. Incubation times were 45 min with biotinylated secondary antibodies, followed by a 2 h incubation with a mixture of fluorochrome-conjugated secondary antibody and streptavidin. Immunofluorescent signals were documented as digitized false color images (8-bit tiff format) with an Olympus BX50WI confocal laser scanning microscope (Olympus Optical, Hamburg, Germany) and Olympus Fluoview 2.1 software.

3. Results

3.1. Specificity and ubiquity of WE14 staining

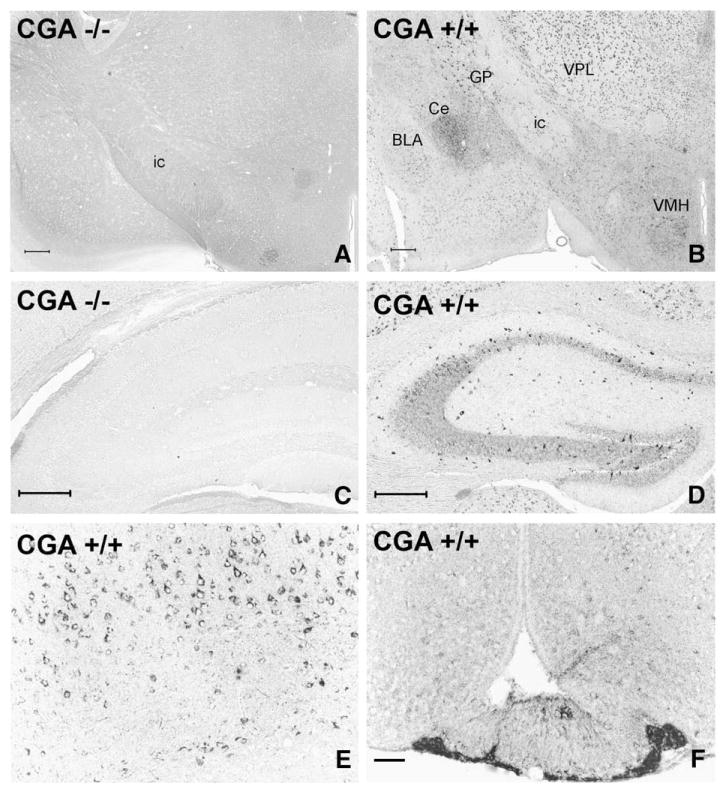

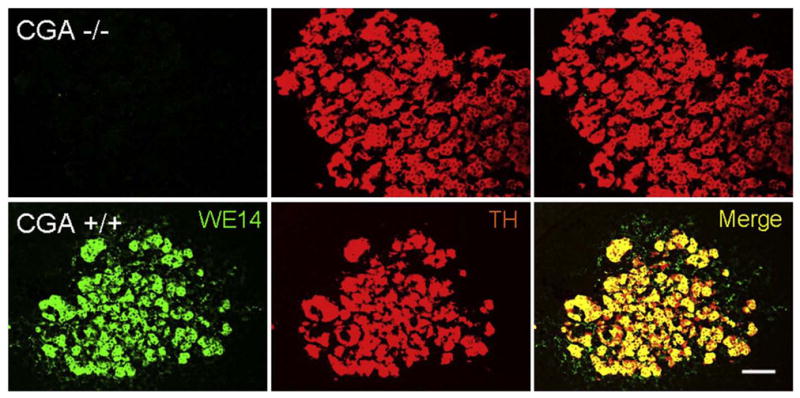

Chromogranin A (i.e. WE14) immunoreactivity is widespread but exhibits varied levels of expression throughout the mouse central nervous system (Fig. 1). Knock-out of both chromogranin alleles has been back-crossed onto C57Bl/6 mice, a strain in which genetic, endocrine and behavioral experiments are commonly performed. Fig. 1A and C demonstrate that in the mouse brain not expressing CGA transcripts, there is no signal using the WE14 antibody, indicating its absolute specificity for this CGA epitope. Staining for CGA using the WE14 antibody is also absent in the adrenal medulla of CGA-deficient mice (Fig. 2), indicating complete lack of cross-reactivity for the related granins CGB and SgII, expressed at high levels in chromaffin cells and reported to be elevated in CGA knock-out mice [11,16]. CNS regions with relatively dense WE14-positive fibers include the central nucleus of the amygdala (Fig. 1B) and hypothalamus (Fig. 1F). In cortex, thalamus and striatum, WE14-positive fibers are both sparse, and much less intensely stained, although in these three major areas WE14-positive cell bodies are ubiquitous (Fig. 1B). Hippocampus contains weakly WE14-stained fibers (e.g. in CA3 radial layer), and weak staining of both pyramidal and granular neuronal cell bodies in dentate gyrus. Of note, GABAergic interneurons in the hippocampus are strikingly intensely WE14-positive (Fig. 1D). At higher magnification, pyramidal cells (Fig. 1E) of cortical layer V are strongly and uniformly positive for CGA. In addition to prominent fiber staining of hypothalamus and central amygdala, the median eminence is positive for CGA fibers, with the internal layer of the median eminence more strongly stained than the external layer (Fig. 1F).

Fig. 1.

Analysis of the specificity and distribution of CGA/WE14 immunostaining in mouse forebrain employing CGA-deficient and wild-type mice. Note total absence of WE14 staining in a coronal brain section at the level of the diencephalon (A) and the hippocampus (C) of a CGA-deficient mouse demonstrating the specificity of WE14 immunostaining for CGA. WE14-immunostaining is present in perikarya of the thalamus, globus pallidus and ventromedial hypothalamus and in fibers of the limbic system of a CGA +/+ mouse (B). Note strong WE14 staining of perikarya of presumed GABAergic interneurons and of fibers in the radial layer of the CA2 and CA3 hippocampal region and in dentate gyrus of a CGA +/+ mouse, while pyramidal and granular cell layers are only weakly WE14-immunopositive (D). The perikarya of layer V pyramidal neurons of parietal neocortex of a CGA +/+ mouse are strongly immunoreactive for CGA (E). Note stronger WE-14 fiber immunostaining in the internal layer of the median eminence (ME) than in the external layer, and weakly WE14-stained neuronal perikarya and fibers in the arcuate nucleus. WE14 immunostaining is strong in the endocrine cells in the tuberal part of the anterior pituitary (F). ic, internal capsule; GP, globus pallidus; VPL, ventral posterolateral thalamic ncl.; Ce, central ncl. of amygdala, BLA, basolateral ncl. of amygdala; VMH, ventromedial hypothalamic ncl. Bars=200 μm (A, B), 100 μm (C, D), 50 μm (E, F).

Fig. 2.

CGA immunostaining in wild-type compared to CGA-deficient mouse adrenal gland. WE14 immunoreactivity is totally absent from adrenal medulla of CGA-deficient, compared to wild-type C57Bl/6 mouse. Number and staining intensity of TH (tyrosine hydroxylase)-positive cells are unchanged, consistent with findings in the original CGA-deficient mouse prior to back-crossing onto the C57Bl/6 background. Note WE14-ir fibers, especially notable in merged image from wild-type adrenal medulla, presumably from PACAPergic/cholinergic splanchnic nerve terminals innervating the gland. Bar=50 μm.

3.2. Distribution of WE14-ir in cholinergic and catecholaminergic projection systems

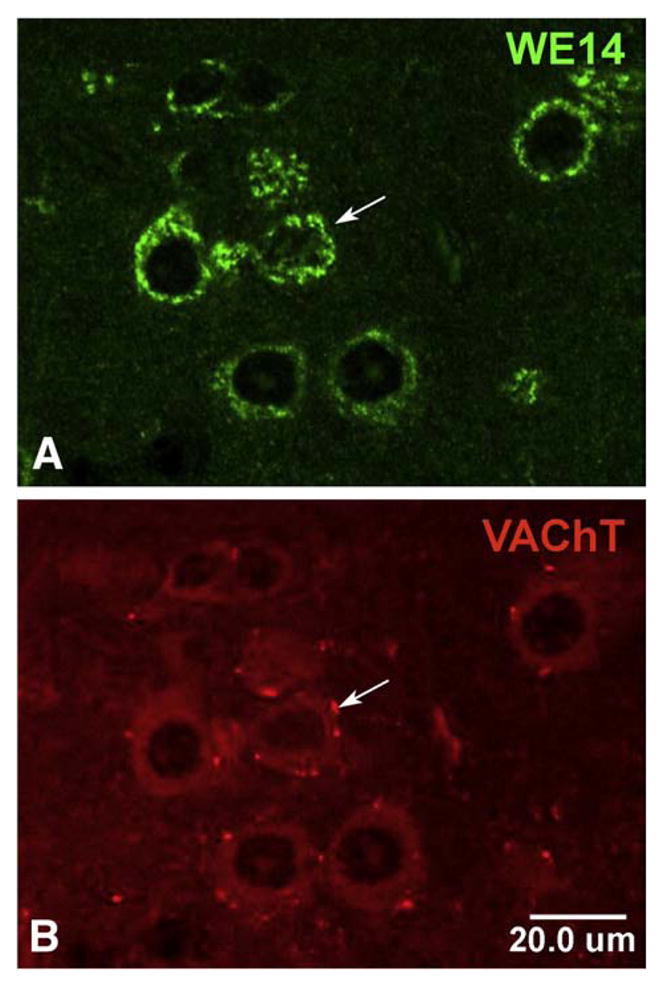

VAChT and CGA are co-localized to cell bodies of motoneuron terminals both in the spinal ventral horn and in cranial motor nuclei (Figs. 3 and 4). Autapses deriving from cholinergic motoneurons, however, are strongly VAChT-positive as in the rat [45], but lack WE14 staining (Figs 3 and 4).

Fig. 3.

CGA expression in cholinergic motoneurons in mouse spinal cord. Confocal microscopic analysis of motoneurons after double immunofluorescent staining of mouse spinal cord sections with WE14 and VAChT. Staining for WE14 (A) is concentrated in the perikarya of VAChT-positive cholinergic motoneurons (B) but appears to be absent from VAChT-positive cholinergic autapses (arrow). Bar=20 μm.

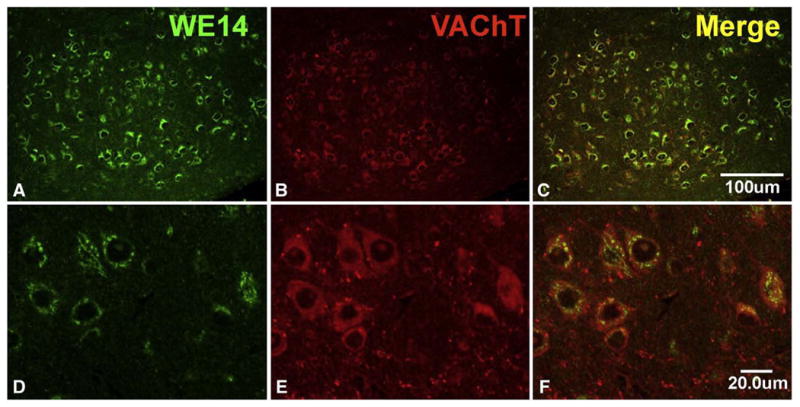

Fig. 4.

CGA expression in mouse brain stem motor nucleus of the trigeminal nerve. Note presence of WE14 immunoreactivity in the perikarya of virtually all VAChT-positive cholinergic motoneurons at low and high magnification and absence of WE14 staining from VAChT-positive cholinergic autapses (postnatal day 1). Bar=100 μm in upper panel and 20 μm in lower panel.

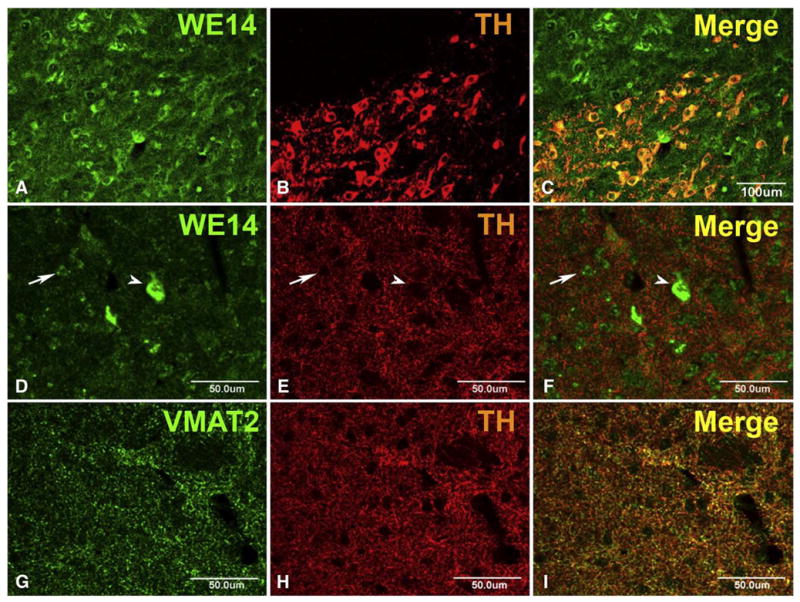

WE14 immunoreactivity is clearly associated with both noradrenergic cell bodies of locus coeruleus (Fig. 5) and dopaminergic cell bodies of substantia nigra pars compacta (Fig. 6), although WE14 staining is as intense in non-dopaminergic (TH-negative) cells of nearby nucleus ruber as in the TH-positive dopaminergic cell bodies of the zona compacta (Fig. 6). It is striking, however, that nerve terminals of noradrenergic neurons (in locus coeruleus itself, Fig. 5) and dopaminergic neurons (in striatum, Fig. 6D-I) do not show co-localization of WE14 with the biogenic amine transporter VMAT2. Insofar as CGA at nerve terminals is indeed a marker for LDCVs, these observations strengthen the conclusion from previous immunoelectronmicroscopical observations of VMAT2 localization that biogenic amine synaptic transmission in the central nervous system, unlike noradrenergic neuroeffector secretion in the peripheral nervous system, is largely from SSVs [46].

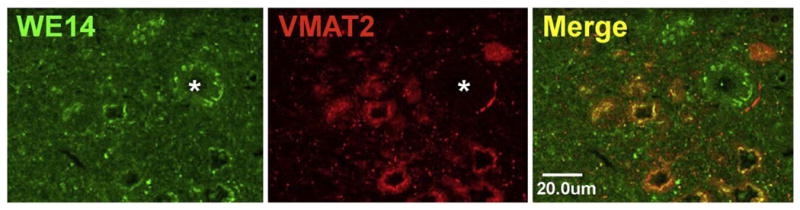

Fig. 5.

CGA expression in the locus coeruleus. WE14 immunostaining is present in perikarya of VMAT2-positive noradrenergic rat locus coeruleus neurons. Note that WE14 immunostaining is mostly absent from VMAT2 terminals and from a neuronal cell body (asterisk) of the sensory mesencephalic nucleus of the trigeminal nerve. Bar=20 μm.

Fig. 6.

CGA expression in mouse nigrostriatal system. Coronal brain sections through the midbrain (A–C) and the striatum (D–F) of an adult CGA +/+ mouse (C57Bl/6). Note preferential perikaryal localization, and similar abundance of WE14 immunoreactivity, in TH-positive neurons of the substantia nigra pars compacta and the adjacent TH-negative nucleus ruber (A–C). WE14 immunostaining is present at high abundance in presumed large cholinergic striatal interneurons (arrow head) and at low abundance in presumed small GABAergic striatal projection neurons (arrow) but virtually absent from TH-positive fibers and terminals in the striatum (D–F). Unlike WE14 staining, VMAT2 staining is present in, and mostly overlapping with, TH-positive varicose fibers in the striatum (G–I). Bar=100 μm (A–C), bar=50 μm (D–I).

3.3. Distribution of CGA in somata and terminals of classical excitatory and inhibitory neuronal systems in CNS

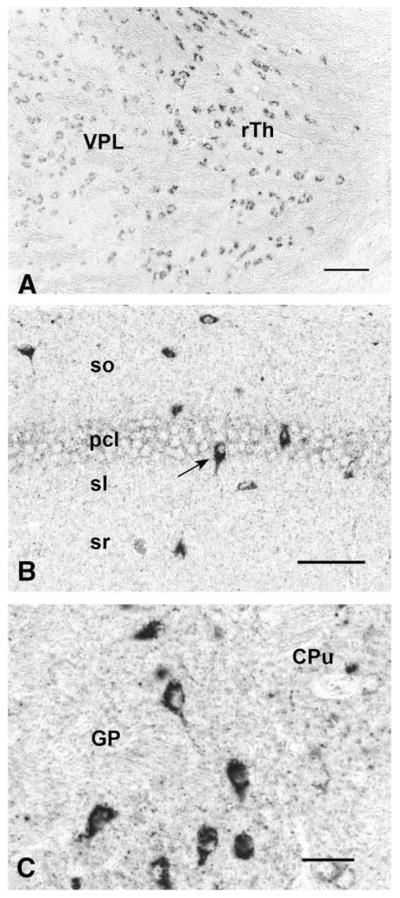

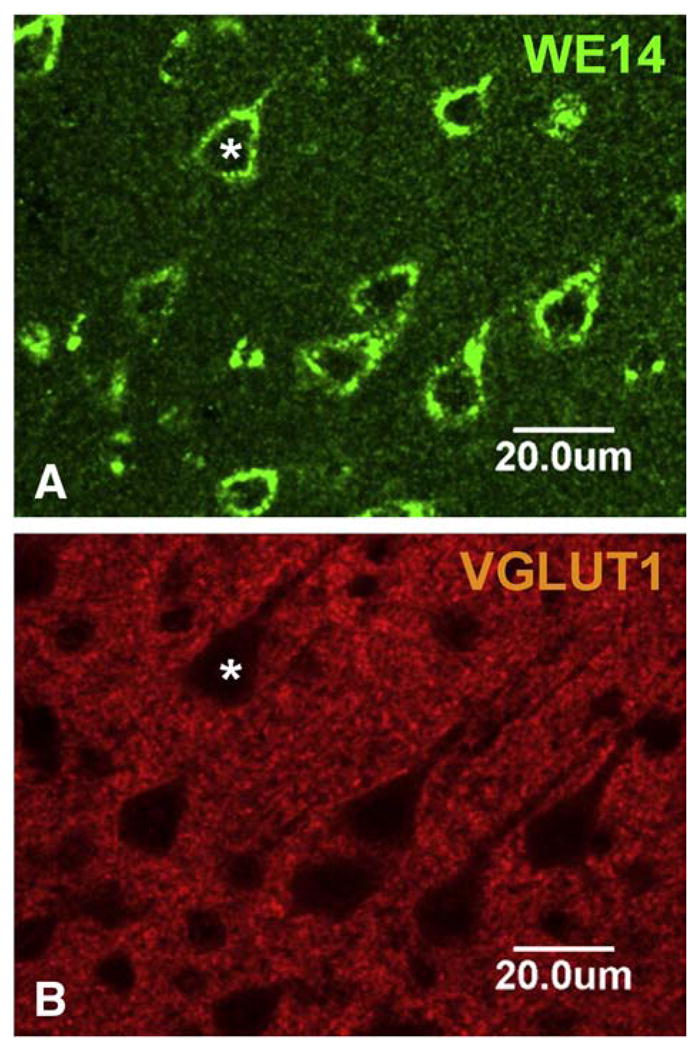

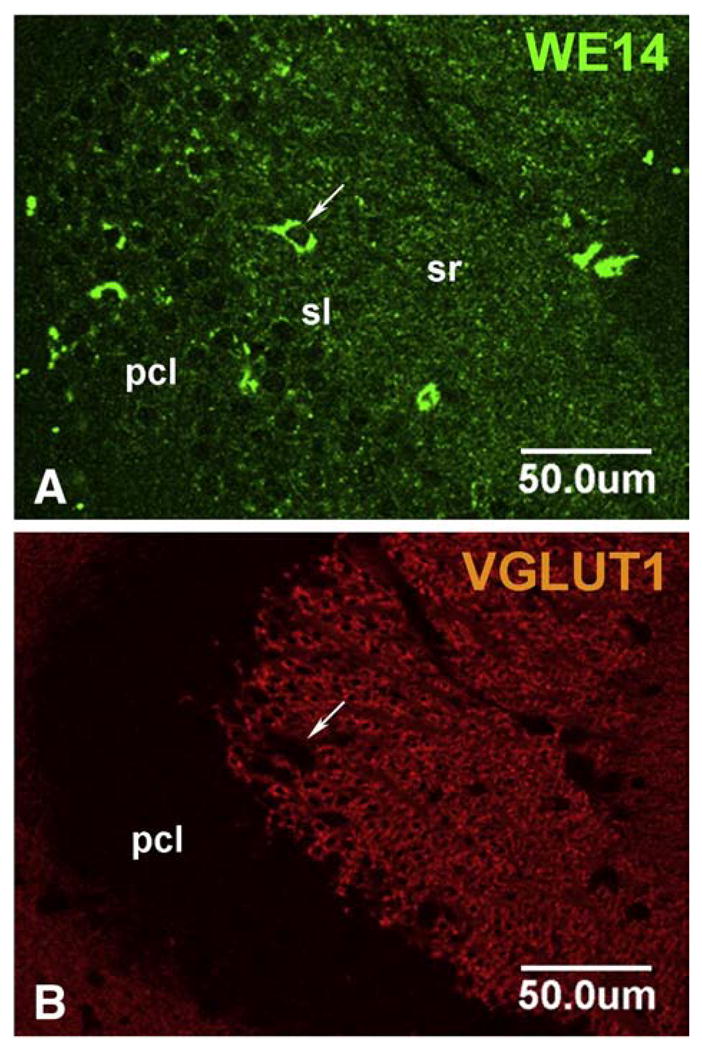

The presence of CGA in neuronal cell bodies, but not in terminals, of classical transmitter neurons of the CNS is seen also in excitatory (glutamatergic) and inhibitory (GABAergic) neurons. Thus, neocortical glutamatergic neurons show strong CGA immunoreactivity in cell bodies and proximal dendrites with CGA virtually absent from abundant VGluT1-positive (Fig. 7) or VGluT2-positive (data not shown) terminals. Faint CGA/WE14 staining of pyramidal cells in hippocampus, with very strong staining of scattered presumptive GABAergic interneurons, against a background of intense glutamatergic terminal staining in which CGA expression is virtually absent is shown in Fig. 8. Thus, it is a general observation in multiple classical neurotransmitter systems of the CNS that while CGA staining is ubiquitous and intense, it is largely confined to cell bodies including proximal dendrites and absent from nerve terminals. It is also striking that CGA immunoreactivity is highest in the cell bodies of inhibitory neurons, compared to excitatory and biogenic amine-coding neurons. A high-power view of the thalamus (Fig. 9) shows GABAergic neurons of reticular thalamic nucleus adjacent to excitatory neurons of ventral posterolateral thalamic nucleus, with intense CGA staining of the former compared to the latter. Likewise, pyramidal and granule cell bodies in the CA regions of hippocampus and dentate gyrus, respectively, are weakly CGA-immunoreactive (Fig. 9). Inhibitory basket cells in the pyramidal layer are intensely WE14-positive (Fig. 9). In contrast, CGA-ir has been reported in mossy fiber terminals from human dentate granule cells, and CA2 pyramidal cells, but without the intense staining of interneurons as observed in mouse [47]. Since the WE14 antibody was not used in the latter study, it is not yet clear if differences between mouse and human, or between antibodies that detect CGA proteins selectively with respect to post-translational modification, are responsible for this discrepancy.

Fig. 7.

CGA expression in the pyramidal cell layer of mouse neocortex. WE14 immunostaining is present in lamina V cell bodies and proximal dendrites of pyramidal, presumed glutamatergic neurons, but is mostly absent from VGluT1 stained glutamatergic synapses. Bar=20 μm.

Fig. 8.

CGA expression in the CA3 hippocampal region of the mouse. Weak WE14 immunostaining is present in glutamatergic pyramidal cells (A). Note scattered presumed GABAergic interneurons strongly stained for WE-14 (arrow). The stratum radiatum is heavily invested with WE14-negative VGluT1 synapses known to originate from the dentate gyrus. Pcl, pyramidal cell layer; sl, stratum lucidum; sr, stratum radiatum; Bar=50 μm.

Fig. 9.

CGA expression in GABAergic regions of mouse brain. GABAergic neurons of the reticular thalamic nucleus (rTh) show stronger immunostaining than the glutamatergic neurons of the ventral posterolateral thalamic nucleus (VPL) (A). Bar=50 μm. In the CA1 region of hippocampus, the glutamatergic neurons located in the pyramidal cell layer (pcl) exhibit only weak WE14 immunoreactivity (B). In contrast, presumed inhibitory (GABAergic) interneurons (arrow) scattered through all layers of CA1 show strong WE14 immunoreactivity. Bar=50 μm. In contrast to the caudate–putamen (CPu), the globus pallidus contains presumed GABAergic neurons with very strong WE14 immunoreactivity (C). Bar=25 μm. So, stratum oriens; pcl, pyramidal cell layer; sl, stratum lucidum; sr, stratum radiatum.

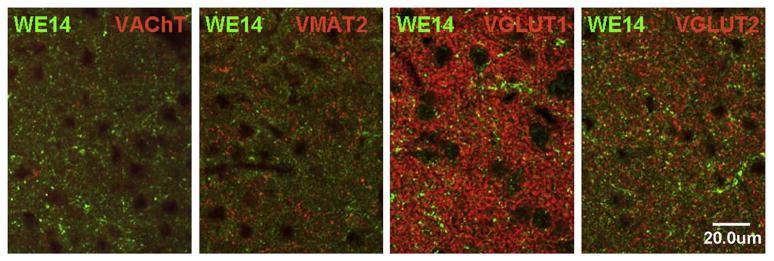

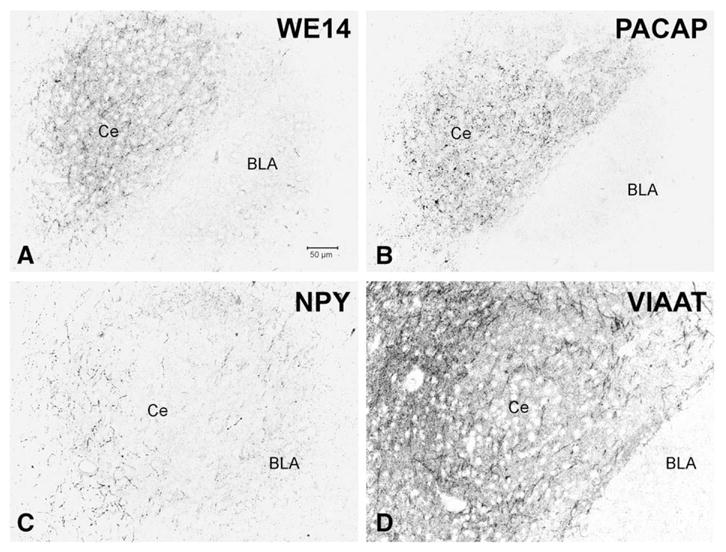

3.4. Expression of classical amine, peptidergic and CGA co-phenotypes in amygdala, an area with a strongly CGA-positive terminal field

The central nucleus of the amygdala, along with hypothalamus, is one of the few regions of the brain that features a high density of CGA-positive nerve terminals (Fig. 1). Although glutamatergic, cholinergic, and monoaminergic as well as CGA fibers are dense in this region, there is remarkably little co-expression of CGA with VGluT1, VGluT2, VAChT, or VMAT2, shown here for rat (Fig. 10), to allow employment of a guinea-pig VMAT2 antibody, which is non-reactive in the mouse. This is in contrast to CGA expression in peripheral neurons that co-express classical neurotransmitters and neuropeptides (e.g. splanchnic nerve, see Fig. 2). Staining for the vesicular inhibitory amino acid transporter (vesicular GABA transporter; VIAAT) is likewise not in register with that of CGA in terminal fields within the central nucleus of the amygdala (Fig. 11D). Neuropeptide staining, on the other hand (albeit not directly co-localized due to absence of species-distinct antibodies for PACAP and CGA) demonstrates a very similar terminal field distribution, especially for PACAP, suggesting that WE14 staining of nerve terminals is shared by this neuropeptide (Fig. 11A–C).

Fig. 10.

Comparative distribution of WE14 immunoreactivity and classical neurotransmitter markers in the rat amygdala. High resolution confocal microscopy analysis of the central ncl. of amygdala after double immunofluorescent staining with WE14 and specific neurotransmitter synaptic markers Note mutual exclusion of WE14 and cholinergic (VAChT) as well as monoaminergic (VMAT2) immunostaining. There is a minor costaining of WE14 with glutamatergic synaptic markers VGluT1 or VGluT2. Bar=20 μm.

Fig. 11.

Comparative distribution of WE14 and neuropeptide-immunoreactive innervation of the mouse central nucleus of the amygdala in relation to GABAergic innervation. Adjacent sections alternately stained for WE14 (A), PACAP (B), NPY (C) and VIAAT (D). WE14-immunoreactive fibers and terminals are concentrated in the central ncl. of amygdala where they exhibit substantial overlap with PACAP- but not with NPY-immunoreactive varicose fibers. Note partial coincidence of WE14 immunostaining with VIAAT-positive GABAergic terminals. Ce, central ncl. of amygdala; BLA, basolateral ncl. of amygdala. Bar=50 μm.

4. Discussion

Previous studies in sheep and rat have indicated that CGA expression is ubiquitous throughout the central nervous system, but without an obvious preference for any single classical neurotransmitter system [26,27,30]. Specific antibodies for the glutamatergic, GABAergic, cholinergic and monoaminergic vesicular transporters can now be used to conveniently visualize multiple classical neurotransmitter-containing nerve terminal compartments to examine co-localization with CGA at the cellular and subcellular levels in the CNS. In addition, the use of an antibody that recognizes the highly conserved WE14 epitope of CGA allows unbiased examination of the cellular distribution of CGA immunoreactivity among these neuronal populations whether it exists in unprocessed, highly processed and/or glycanated forms [36]. Carrying out this chemical neuroanatomical study in the mouse affords the opportunity for future genetic dissection of the role of CGA in CNS function. In the present study, the availability of the CGA knock-out mouse also provided a crucial control for specificity of CNS neuronal staining with CGA-directed antibodies.

CGA expression in the mouse, as in the rat CNS, is ubiquitous. CGA is expressed in the cell bodies of most anatomically defined inhibitory, excitatory and aminergic cell groups of the brain and spinal cord. However there are distinct features of CGA cellular distribution and intensity of expression in the CNS, with CGA expression much less abundant in terminal fields than classically described in the peripheral nervous system [19]. The relative paucity of CGA expression in terminals of classical neurotransmitter systems in CNS, despite its substantial expression in cell bodies in these systems, is consistent with a greater population of large dense-core vesicles in peripheral compared to central biogenic amine neurons. CGA fibers are numerous in restricted brain areas, such as the hypothalamus and amygdala. In these CGA-positive terminal fields, e.g. in central amygdala, co-expression with nerve terminal cholinergic, catecholaminergic, GABAergic and glutamatergic vesicular transporter proteins is absent or minimal. Rather, the distribution of CGA in nerve terminals in amygdala is consistent with its restriction to terminals containing neuropeptides such as PACAP.

CGA is unambiguously associated with catecholaminergic large dense-core vesicles, but not small dense-core vesicles, in peripheral sympathetic nerve terminals [48]. CGA function in the periphery thus appears to correspond to the generation and maintenance of the regulated secretory compartment, as postulated upon the initial discovery of CGA as the major secreted protein, and large dense-core vesicle constituent, of chromaffin cells [49,50]. This appears to be the case for terminal fields of sympathetic neurons as well, as de Potter et al. demonstrated catecholamine release from sympathetic fibers coincident with neurosecretory protein/neuropeptide release from both spleen and vas deferens [50]. In the CNS however, CGA is largely absent from nerve terminals of catecholaminergic neurons, though present in cell bodies. This raises two related questions: why are biogenic amines of CNS not released from LDCVs, as in the periphery, and if CGA is neither a prohormone nor required for catecholamine storage and release, what is its function in these cells? The fact that a large fraction of unprocessed CGA exists as a proteoglycan in the CNS may provide a hint as to its non-granulogenic function. Urishitani et al. have suggested a chaperone role for CGA in the CNS related to the removal of misfolded proteins including superoxide dismutase [35]. CGA may perform a similar function in CNS catecholaminergic, as well as cholinergic, glutamatergic and GABAergic neurons. The clearly higher expression of CGA in GABAergic neuronal somata suggests that this role of CGA may be especially important in inhibitory neurons. Future microproteomic analysis of the CGA protein forms found in GABAergic neurons or neuronal cell lines could potentially provide clues about the ‘non-terminal’ neuronal function of CGA.

The hypothalamus and amygdala are prominent terminal field regions where CGA expression is most intense. These are areas of the brain in which neuropeptide levels are frequently quite high relative to other brain regions. It will be of considerable interest to determine if these regions have a higher concentration of processed versus intact CGA/WE14, or if CGA carries out in these neurons the vesiculogenic role ascribed to it in the peripheral nervous, neuroendocrine and endocrine systems [13–15]. In this regard it is of interest that CGA, VMAT2 and BDNF occupy a similar secretory compartment when co-expressed in primary hippocampal neurons, where neurotrophin dendritic release occurs [51]. Dendritic release is a feature of CNS catecholaminergic neurons as well as BDNF secretion from hippocampal dendrites [52]. Given its pronounced somatodendritic localization in hippocampus, a general role for CGA in the regulation of this unique neurosecretory compartment may be envisaged.

5. Conclusions

The cellular distribution of CGA immunoreactivity is restricted, in defined chemically-coded populations of CNS neurons, mainly to cell bodies and proximal dendrites. CGA immunoreactivity is found most abundantly in terminal fields, on the other hand, in select locations at which peptidergic expression is also high. These observations suggest that CGA functions within some CNS neurons, as in the periphery, as a prohormone and large dense-core granulogenic factor. However, its distinct cellular localization and marked absence from classical catecholaminergic nerve terminals in the CNS argues for unique cellular functions of CGA within somatodendritic compartments in neurons of the brain.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by NIMH-IRP Project Z01-MH002386-23 (LEE), NIH grant R01DA011311-10 (SM), University Clinics Giessen Marburg (UKGM) grant (MKHS) and a grant from the Volkswagen-Stiftung (LEE, EW). The technical assistance of Heidemarie Schneider, Michael Schneider, Barbara Wiegand, Marion Zibuschka, and David Huddleston is gratefully acknowledged.

References

- 1.Uvnäs B, Aborg C-H. The ability of ATP-free granule material from bovine adrenal medulla to bind inorganic cations and biogenic amines. Acta Physiol Scand. 1977;99:476–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1977.tb10401.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Helle KB, Reed RK, Pihl KE, Serck-Hanssen G. Osmotic properties of the chromogranins and relation to osmotic pressure in catecholamine storage granules. Acta Physiol Scand. 1985;123:21–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1985.tb07556.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoo SH, Albanesi JP, Jameson DM. Fluorescence studies of nucleotide interactions with bovine adrenal chromogranin A. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1990;1040:66–70. doi: 10.1016/0167-4838(90)90146-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yoo SH, Albanesi JP. High capacity, low affinity Ca2+ binding of chromogranin A. J Biol Chem. 1991;266:7740–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Videen JS, Mezger MS, Chang YM, O’Connor DT. Calcium and catecholamine interactions with adrenal chromogranins. Comparison of driving forces in binding and aggregation. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:3066–73. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Montesinos MS, Machado JD, Camacho M, Diaz J, Morales YG, Alvarez de la Rosa D, Carmona E, Castaneyra A, Viveros OH, O’Connor DT, Mahata SK, Borges R. The crucial role of chromogranins in storage and exocytosis revealed using chromaffin cells from chromogranin A null mouse. J Neurosci. 2008;28:3350–8. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5292-07.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eiden LE. Is chromogranin a prohormone? Nature. 1987;325:301. doi: 10.1038/325301a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tatemoto K, Efendic S, Mutt V, Makk G, Feistner GJ, Barchas JD. Pancreastatin, a novel pancreatic peptide that inhibits insulin secretion. Nature. 1986;324:476–8. doi: 10.1038/324476a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Helle KB, Metz-Boutigue M-H, Aunis D. Chromogranin A as a calcium-binding precursor for a multitude of regulatory peptides for the immune, endocrine and metabolic systems. Curr Med Chem-Imm, Endoc Metab Agents. 2001;1:119–40. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mahata SK, Mahata M, Wakade AR, O’Connor DT. Primary structure and function of the catecholamine release inhibitory peptide catestatin (chromogranin A344–364): identification of amino acid residues crucial for activity. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14:1525–35. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.10.0531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mahapatra NR, O’Connor DT, Vaingankar SM, Hikim AP, Mahata M, Ray S, Staite E, Wu H, Gu Y, Dalton N, Kennedy BP, Ziegler MG, Ross J, Mahata SK. Hypertension from targeted ablation of chromogranin A can be rescued by the human ortholog. J Clin Invest. 2005;115:1942–52. doi: 10.1172/JCI24354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mahata SK, O’Connor DT, Mahata M, Yoo SY, Taupenot L, Wu H, Gill BM, Parmer RJ. Novel autocrine feedback control of catechoamine release. A discrete chromogranin A fragment is a noncompetitive nicotinic cholinergic antagonist. J Clin Invest. 1997;100:1623–33. doi: 10.1172/JCI119686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim T, Tao-Cheng J-H, Eiden LE, Loh YP. Chromogranin A, an “on/off” switch controlling dense-core secretory granule biogenesis. Cell. 2001;106:499–509. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00459-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Montero-Hadjadje M, Elias S, Chevalier L, Benard M, Tanguy Y, Turquier V, Galas L, Yon L, Malagon MM, Driouich A, Gasman S, Anouar Y. Chromogranin A promotes peptide hormone sorting to mobile granules in constitutively and regulated secreting cells: role of conserved N- and C-terminal peptides. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:12420–31. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M805607200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Courel M, Rodemer C, Nguyen ST, Pance A, Jackson AP, O’Connor DT, Taupenot L. Secretory granule biogenesis in sympathoadrenal cells: identification of a granulogenic determinant in the secretory prohormone chromogranin A. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:38038–51. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M604037200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hendy GN, Li T, Girard M, Feldstein RC, Mulay S, Desjardins R, Day R, Karaplis AC, Tremblay ML, Canaff L. Targeted ablation of the chromogranin a (Chga) gene: normal neuroendocrine dense-core secretory granules and increased expression of other granins. Mol Endocrinol. 2006;20:1935–47. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cohn DV, Zangerle R, Fischer-Colbrie R, Chu LLH, Elting JJ, Hamilton JW, Winkler H. Similarity of secretory protein I from parathyroid gland to chromogranin A from adrenal medulla. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1982;79:6056–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.19.6056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Connor DT. Chromogranin: widespread immunoreactivity in polypeptide hormone producing tissues and in serum. Regul Pept. 1983;6:263–80. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(83)90145-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fischer-Colbrie R, Lassmann H, Hagn C, Winkler H. Immunological studies on the distribution of chromogranin A and B in endocrine and nervous tissues. Neuroscience. 1985;16:547–55. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(85)90191-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lassman H, Hagn C, Fischer-Colbrie R, Winkler H. Presence of chromogranin A, B and C in bovine endocrine and nervous tissues: a comparative immunohistochemical study. Histochem J. 1986;18:380–6. doi: 10.1007/BF01675219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Horsch D, Fink T, Goke B, Arnold R, Buchler M, Weihe E. Distribution and chemical phenotypes of neuroendocrine cells in the human anal canal. Regul Pept. 1994;54:527–42. doi: 10.1016/0167-0115(94)90550-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nolan JA, Trojanowski JQ, Hogue-Angeletti R. Neurons and neuroendocrine cells contain chromogranin: detection of the molecule in normal bovine tissues by immunochemical and immunohistochemical methods. J Histochem Cytochem. 1985;33:791–8. doi: 10.1177/33.8.3894497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iacangelo A, Affolter HU, Eiden LE, Herbert E, Grimes M. Bovine chromogranin A sequence and distribution of its messenger RNA in endocrine tissues. Nature. 1986;323:82–6. doi: 10.1038/323082a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lloyd RV, Wilson BS. Specific endocrine tissue marker defined by a monoclonal antibody. Science. 1983;222:628–30. doi: 10.1126/science.6635661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Helle KB, Angeletti RH. Chromogranin A: a multipurpose prohormone? Acta Physiol Scand. 1994;152:1–10. doi: 10.1111/j.1748-1716.1994.tb09779.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Somogyi P, Hodgson AJ, DePotter RW, Fischer-Colbrie R, Schober M, Winkler H, Chubb IW. Chromogranin immunoreactivity in the central nervous system. Immunochemical characterisation, distribution and relationship to catecholamine and enkephalin pathways. Brain Res Rev. 1984;8:193–230. doi: 10.1016/0165-0173(84)90007-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Weiler R, Marksteiner J, Bellman R, Wohlfarter T, Schober M, Fischer-Colbrie R, Sperk G, Winkler H. Chromogranins in rat brain: characterization, topographical distribution and regulation of synthesis. Brain Res. 1990;532:87–94. doi: 10.1016/0006-8993(90)91746-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mahata M, Mahata SK, Fischer-Colbrie R, Winkler H. Ontogenic development and distribution of mRNAs of chromogranin A and B, secretogranin II, p65 and synaptin/synaptophysin in rat brain. Dev Brain Res. 1993;76:43–58. doi: 10.1016/0165-3806(93)90121-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Mahata SK, Mahata M, Marksteiner J, Sperk G, Fischer-Colbrie R, Winkler H. Distribution of mRNAs for chromogranins A and B and secretogranin II in rat brain. Eur J Neurosci. 1991;3:895–904. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.1991.tb00101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schäfer MK-H, Nohr D, Romeo H, Eiden LE, Weihe E. Pan-neuronal expression of chromogranin A in rat nervous system. Peptides. 1994;15:263–79. doi: 10.1016/0196-9781(94)90012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Woulfe J, Deng D, Munoz D. Chromogranin A in the central nervous system of the rat: pan-neuronal expression of its mRNA and selective expression of the protein. Neuropeptides. 1999;33:285–300. doi: 10.1054/npep.1999.0043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Beinfeld MC, Funkelstein L, Foulon T, Cadel S, Kitagawa K, Toneff T, Reinheckel T, Peters C, Hook V. Cathepsin L plays a major role in cholecystokinin production in mouse brain cortex and in pituitary AtT-20 cells: protease gene knockout and inhibitor studies. Peptides. 2009;30:1882–91. doi: 10.1016/j.peptides.2009.06.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Biswas N, Rodriguez-Flores JL, Courel M, Gayen JR, Vaingankar SM, Mahata M, Torpey JW, Taupenot L, O’Connor DT, Mahata SK. Cathepsin L colocalizes with chromogranin a in chromaffin vesicles to generate active peptides. Endocrinology. 2009;150:3547–57. doi: 10.1210/en.2008-1613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Eskeland NL, Zhou A, Dinh TQ, Wu H, Parmer RJ, Mains RE, O’Connor DT. Chromogranin A processing and secretion: specific role of endogenous and exogenous prohormone convertases in the regulated secretory pathway. J Clin Invest. 1996;98:148–56. doi: 10.1172/JCI118760. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Urushitani M, Sik A, Sakurai T, Nukina N, Takahashi R, Julien JP. Chromogranin-mediated secretion of mutant superoxide dismutase proteins linked to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. Nat Neurosci. 2006;9:108–18. doi: 10.1038/nn1603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Rieker S, Fischer-Colbrie R, Eiden L, Winkler H. Phylogenetic distribution of peptides related to chromogranins A and B. J Neurochem. 1988;50:1066–73. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.1988.tb10574.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wohlfarter T, Fischer-Colbrie R, Hogue-Angeletti R, Eiden LE, Winkler H. Processing of chromogranin A within chromaffin granules starts at C- and N-terminal cleavage sites. FEBS Lett. 1988;231:67–70. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(88)80704-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Weihe E, Depboylu C, Schutz B, Schafer MK, Eiden LE. Three types of tyrosine hydroxylase-positive CNS neurons distinguished by dopa decarboxylase and VMAT2 co-expression. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2006;26:659–78. doi: 10.1007/s10571-006-9053-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schäfer MK-H, Eiden LE, Weihe E. Cholinergic neurons and terminal fields revealed by immunohistochemistry for VAChT, the vesicular acetylcholine transporter I. Central nervous system. Neuroscience. 1998;84:331–59. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)00516-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Weihe E, Tao-Cheng J-H, Schäfer MK-H, Erickson JD, Eiden LE. Visualization of the vesicular acetylcholine transporter in cholinergic nerve terminals and its targeting to a specific population of small synaptic vesicles. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996;93:3547–52. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Schutz B, von Engelhardt J, Gordes M, Schafer MK, Eiden LE, Monyer H, Weihe E. Sweat gland innervation is pioneered by sympathetic neurons expressing a cholinergic/noradrenergic co-phenotype in the mouse. Neuroscience. 2008;156:310–8. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.06.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Hamelink C, Tjurmina O, Damadzic R, Young WS, Weihe E, Lee H-W, Eiden LE. Pituitary adenylate cyclase activating polypeptide is a sympathoadrenal neurotransmitter involved in catecholamine regulation and glucohomeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:461–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.012608999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.De Gois S, Schafer MK, Defamie N, Chen C, Ricci A, Weihe E, Varoqui H, Erickson JD. Homeostatic scaling of vesicular glutamate and GABA transporter expression in rat neocortical circuits. J Neurosci. 2005;25:7121–33. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5221-04.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Weihe E, Eiden LE. Chemical neuroanatomy of the vesicular amine transporters. FASEB J. 2000;14:2435–49. doi: 10.1096/fj.00-0202rev. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Schäfer MK-H, Eiden LE, Weihe E. Cholinergic neurons and terminal fields revealed by immunohistochemistry for VAChT, the vesicular acetylcholine transporter II. Peripheral nervous system. Neuroscience. 1998;84:361–76. doi: 10.1016/s0306-4522(97)80196-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Pickel VM, Nirenberg MJ, Milner TA. Ultrastructural view of central catecholaminergic transmission: immunocytochemical localization of synthesiznng enzymes, transporters and receptors. J Neurocytol. 1996;25:843–56. doi: 10.1007/BF02284846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Munoz DG. The distribution of chromogranin A like immunoreactivity in the human hippocampus coincides with the pattern of resistance to epilepsy-induced neuronal damage. Ann Neurol. 1990;27:266–75. doi: 10.1002/ana.410270308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hagn C, Klein RL, Fischer-Colbrie R, Douglas BH, II, Winkler H. An immunological characterization of five common antigens of chromaffin granules and of large dense-cored vesicles of sympathetic nerve. Neurosci Lett. 1986;67:295–300. doi: 10.1016/0304-3940(86)90325-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Winkler H, Sietzen M, Schober M. The life cycle of catecholamine-storing vesicles. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 1987;493:3–19. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb27176.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.De Potter WP, Partoens P, Schoups A, Llona I, Coen EP. Noradrenergic neurons release both noradrenaline and neuropeptide Y from a single pool: the large dense cored vesicles. Synapse. 1997;25:44–55. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2396(199701)25:1<44::AID-SYN6>3.0.CO;2-F. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Li H, Waites CL, Staal RG, Dobryy Y, Park J, Sulzer DL, Edwards RH. Sorting of vesicular monoamine transporter 2 to the regulated secretory pathway confers the somatodendritic exocytosis of monoamines. Neuron. 2005;48:619–33. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2005.09.033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nirenberg MJ, Chan J, Liu Y, Edwards RH, Pickel VM. Ultrastructural localization of the vesicular monoamine transporter-2 in midbrain dopaminergic neurons: potential sites for somatodendritic storage and release of dopamine. J Neurosci. 1996;16:4135–45. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-13-04135.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]