Abstract

Purpose

To understand how oncologists provide care at the end of life, the emotions they experience in the provision of this care, and how caring for dying patients may impact job satisfaction and burnout.

Participants and methods

A face-to-face survey and in-depth semistructured interview of 18 academic oncologists who were asked to describe the most recent inpatient death on the medical oncology service. Physicians were asked to describe the details of the patient death, their involvement with the care of the patient, the types and sequence of their emotional reactions, and their methods of coping. Grounded theory qualitative methods were utilized in the analysis of the transcripts.

Results

Physicians, who viewed their physician role as encompassing both biomedical and psychosocial aspects of care, reported a clear method of communication about end-of-life (EOL) care, and an ability to positively influence patient and family coping with and acceptance of the dying process. These physicians described communication as a process, made recommendations to the patient using an individualized approach, and viewed the provision of effective EOL care as very satisfying. In contrast, participants who described primarily a biomedical role reported a more distant relationship with the patient, a sense of failure at not being able to alter the course of the disease, and an absence of collegial support. In their descriptions of communication encounters with patients and families, these physicians did not seem to feel they could impact patients' coping with and acceptance of death and made few recommendations about EOL treatment options.

Conclusion

Physicians' who viewed EOL care as an important role described communicating with dying patients as a process and reported increased job satisfaction. Further research is necessary to determine if educational interventions to improve physician EOL communication skills could improve physician job satisfaction and decrease burnout.

Introduction

Although the care of dying patients is an integral part of clinical oncology, most oncologists do not feel well trained in the provision of end-of-life (EOL) care. A 1998 American Society of Clinical Oncology survey of over 6000 oncologists documented shortcomings in EOL care training for oncologists. Fewer than one third of oncologists reported that their formal training was “very helpful” in communicating with dying patients or transitioning goals of care, and over half reported using “trial and error” as one important source of learning about EOL care. Only 25% reported the care of dying patients to be highly satisfying.1

Burnout and decreased job satisfaction are prevalent in many cancer clinicians and lack of training in EOL skills has been identified as a major contributor.2–4 Whippen and Canellos5 studied burnout in oncologists and found that 56% of respondents reported frustration and a sense of personal failure in their work. The authors concluded that coping with the challenges of providing EOL care may be the single most important qualitative factor related to burnout.

Despite the evidence that oncologists feel unprepared to care for dying patients and that this may contribute to decreased job satisfaction and burnout, little is known about oncologists' perceptions of the care they provide to dying patients and how they experience and cope with these encounters. By examining oncologists' descriptions of their most recent patient death, we sought to answer two specific questions: how do oncologists understand and describe the psychosocial care (e.g., communication, emotional support) they deliver to patients at the EOL and how do oncologists describe their emotional reactions to and personal coping with these encounters? We undertook an exploratory study to assist us in the development of a conceptual model to better understand how oncologists provide care at the EOL and how provision of that care may impact job satisfaction and burnout.

Participants and Methods

Selection of participants

Our study of oncologists' descriptions of the most recent patient death was a secondary data analysis from a larger study of physicians' emotional reactions to deaths of their patients. Patients were randomly selected from deaths on the medical services at two highly specialized referral medical centers in Boston, Massachusetts, and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.6 Patient deaths were identified by reviewing the charts of all inpatients who died on the internal medicine services during the previous week. An eligible patient case was one in which at least two physicians could be identified who had cared for the patient at the time of death. Between June 1999 and September 2001, all 196 interns, residents, fellows, and attending physicians who agreed to participate were scheduled for a 90-minute semistructured in-person interview regarding their experiences caring for the most recent patient death and a past patient death that the participant identified as their most emotionally powerful. For the current analysis, we selected all attending oncologists (n = 18) who were participants in the larger study. These attending oncologists were serving as oncology teaching attending on general oncology and transplant oncology services at both institutions.

Both hospitals' Institutional Review Boards approved the study. To promote physicians' willingness to honestly relate their stories, we obtained a certificate of confidentiality from the National Institutes of Health to protect respondents from any potential liability associated with their disclosures.

Methods

We chose to use both quantitative and qualitative methods to allow for a deeper understanding of the physicians' experiences in the care of dying patients. The survey instrument was developed after a review of the existing literature and the analysis of focus groups of medical residents' experiences with patient deaths. The instrument included closed-ended questions (Likert scale 0–10), the Maslach burnout inventory, and open-ended questions with follow-up probes to assist physicians in relating the story of their most recent patient death. The Maslach burnout inventory has been used extensively in physicians and is both valid and reliable in this population.3 It is comprised of three subscales that assess emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and personal accomplishment.

We used the survey instrument as the basis of the in-depth semi-structured face-to-face interview in which we explored aspects of each physician's most recent patient death including: the types and sequence of emotional reactions to the death, the coping response, disturbing and satisfying aspects of care, subsequent changes in behavior, physician expectation of patient death during the hospitalization, nature and extent of communication about death and dying, and any regrets with regard to the care of the patient. All interviews were audiotaped, transcribed, and stripped of identifying data.

Analyses

Univariate and bivariate analyses were completed using the Statistical Analysis System (SAS® Version 8.0, SAS Institute, Cary, NY) for all structured questions. Sample size precluded tests of significance.

We used a grounded theory approach and ATLAS-TI in the analysis of the qualitative transcripts. Grounded theory is a process of identifying analytical categories as they emerge from the data.7–9 We analyzed the transcripts using open coding (the process of breaking down, comparing, conceptualizing, and categorizing data), axial coding (the process of reassembling data into groupings) and selective coding (the process of developing a core theme in the data and relating it to other themes9). In addition to the coding, we developed narrative summaries for each transcript, and built matrices to analyze themes among subgroups of participants.

ATLAS-TI is a software program that provides a systematic approach to the analysis of unstructured qualitative data. It was used both for interpretive and auto-coding of each transcript.

Validity

We assembled a large, diverse group of analysts as a way of ensuring interpretive and theoretical validity and to attenuate any potential researcher bias. Analysts included one pediatric oncologist (J.M.), one palliative care physician (V.J.), one psychology doctoral student (R.M.), one Ph.D. research psychologist (A.S.), and one psychosocial research coordinator (M.L.). The themes derived from the open coding were compared with those themes derived from the ATLAS-TI computerized coding process to ensure capture of important themes. Through discussion at serial meetings, all readers contributed to the coding schema and agreed upon the coding of the transcripts.

In qualitative research, sample size is determined when none of the analysts recognize new or unique themes. This is known as thematic saturation. In our study thematic saturation was reached after the coding of 14 transcripts; however we coded the entire sub-sample of oncologist transcripts resulting in a final sample size of n = 18.

We used both quantitative data and qualitative data to obtain a richer understanding of the phenomena being studied. This is termed triangulation and it is a method of safeguarding validity by using data derived from multiple sources.7–9 We examined the qualitative and quantitative findings together to evaluate the extent of overlap and divergence in themes.

Results

Our study was part of a larger study in which 246 participants were eligible and 196 agreed to participate yielding a response rate of 80%. The demographics of participants and nonparticipants were similar.

The oncologists

Of the 196 physician participants, 18 were oncologists. In the subsample of 18 oncologists, 72% were male, 94% white, and the mean number of years in practice was 11 (Table 1). The oncologists cared for the patients either in the context of ward attending on the inpatient oncology service (56%) or as the primary outpatient oncologist (44%).

Table 1.

Demographics of Oncologist Sample n = 18

| Male n (%) | 13 (72%) |

| Age mean (SD) | 41 (SD 7.5) |

| White n (%) | 16 (94%) |

| Years in practice mean (SD) | 11 (SD 8) |

| Religion: n (%) | |

| Jewish | 11 (61%) |

| Catholic | 4 (22%) |

| Protestant | 1 (6%) |

| None | 2 (12%) |

| Married or in long term relationship n (%) | 13 (72%) |

SD, standard deviation.

The patients

The patients had a variety of cancer diagnoses and died as the result of either complications of treatment or the disease process. Over half of the patient deaths were expected on admission with 56% of the oncologists responding with certainty to the question, “On admission, how certain were you that the patient would die during the hospitalization?” Seven (38%) of the 18 transcripts were related to patients who had undergone either an autologous (4) or an allogenic (3) bone marrow transplantation (BMT).

Quantitative results

All physicians were queried about how emotionally powerful, disturbing, satisfying, and conflict-laden they found the patient death. Table 2 presents the mean responses for the sub-sample of 18 oncologists; responses from nononcology attending physicians in the original study are also presented for comparison. Although sample size precluded testing for significance, the oncologist subsample and the entire sample of nononcologist attending physicians responded similarly to closed-ended questions about the patient death (Table 2).

Table 2.

Characteristics of Most Recent Patient Deaths for Subsample of Oncologists and for Sample of Nononcologist Attending Physicians

| Characteristics of most recent patient deatha | Oncologist subsample n = 18 | Nononcologist attending physicians n = 55 |

|---|---|---|

| How emotionally powerful was this death? | 4.4 (2.6) | 4.5 (2.4) |

| How disturbing was this death? | 3.9 (2.6) | 3.5 (2.5) |

| How satisfying was participating in the care of this patient? | 6.7 (2.3) | 5.8 (2.8) |

| How close was your relationship with this patient? | 4.4 (3.0) | 2.9 (2.3) |

| How much conflict was present? | 2.9 (2.8) | 2.7 (3.0) |

| How much did the patient suffer in the 72 hours before death? | 3.9 (3.2) | 3.6 (2.3) |

| How much did you feel a need for help or support? | 1.2 (2.4) | 1.0 (1.4) |

| Did you receive the help or support you needed from colleagues? | 6.9 (3.6) | 5.9 (4.0) |

Likert scale with 0 representing least and 10 representing most.

Mean values (SD) 0–10 scales.

SD, standard deviation.

Qualitative results

With repeated reading and coding of the transcripts, we noted several themes common to all transcripts: the oncologist's self-described role, relationship with patient/family, satisfaction with the care provided, descriptions of the emotions generated by the death, collegial support, and descriptions of communication with patient and family (Table 3).

Table 3.

Common Themes in Oncologists' Descriptions of their Most Recent Patient Deaths

| Common themes |

|---|

| Self-described role of the oncologist |

| Relationship with patient/family |

| Satisfaction with care provided |

| Emotions generated |

| Disturbing aspects of case/sense of failure associated with the death |

| Collegial support |

| Description of EOL communication with patient and family |

EOL, end-of-life.

For 16 of the 18 transcripts, our analysis group was able to easily code these themes with 100% interrater reliability. However, for two BMT-related death transcripts, the participants did not describe the patient death in a manner that made it possible for us to code the themes of role, relationship with the patient/family, satisfaction with care, collegial support, or method of communication with patient or family. One physician was very upset during his description of the patient death, crying throughout a substantial portion of the interview and unable to relate the details of the patient case, while the other physician did not speak about the most recent patient but rather discussed his concerns about the differences in philosophical approaches to patients undergoing aggressive treatment.

Role

Oncologists described their role in the care of the dying patient in a variety of ways. All participants viewed their role as including the provision of excellent biomedical care (e.g., treatment of cancer with appropriate therapies in hopes of cure or disease-free time.) Some oncologists viewed their role almost exclusively in these biomedical terms while other participants described providing excellent biomedical care and also described a clear psychosocial role; to help the patient and family to cope with and accept the dying process. These respondents identified the psychosocial role as a second core professional responsibility. The psychosocial role often included caring for both the patient and family through building relationships and communicating effectively. A male oncologist stated, “I felt more like a rabbi … that was more how I helped them as their oncologist. I did a lot of talking and preparing.” Another stated: “It was hard for his wife and hard for his kids, very hard for the kids. I was trying to spend some time with the kids as well. I just wanted to make sure that they were doing O.K. because they were more withdrawn and I wanted to make them feel good, you know, we were there for them as well. Ultimately, we ended up being the caretaker of the family as much as the patient.”

A number of oncologists, who described their role in terms of both biomedical and psychosocial care, made a point to describe their goal in terms of outcomes other than cure of the disease. One male oncologist stated: “If you think that you are curing people, in oncology you are going to be miserably disappointed and in 10 years you are worn out. If you are caring (emphasis) for them, you'll succeed all the time. People do well within the window of expectations you have.” In contrast an oncologist who identified himself as primarily biomedical stated, “the doctors are more in the curative mode and the nurses are more in the care mode … nurses are divorced from the responsibility of curing the patient so are much more willing to give up.”

Relationship with Patient/Family

Oncologists differed in how they developed relationships with patients and families. Some oncologists spoke of building rapport and relationships quickly, at times in only one visit. A close relationship appeared to be an expected part of the role. One male participant stated, “I do tend to get very attached to my patients. I don't try to put up a tremendous amount of distance.” Others described a relationship that was less close. A male oncologist described his views on the patient-physician relationship, “when I'm establishing my relationship with a patient, I try to make it professional rather than personal so I don't ask too much about their day-to-day life.”

Satisfaction with the Care Provided

We noted differences in oncologists' descriptions of their satisfaction with the EOL care they provided to patients. For some, it was hard to conceive of any death as satisfying. For example, one female oncologist stated, “No death is satisfying and even though you help people come around, that is the least you can do. It doesn't actually make it any better. I mean there's no good death, really.” Others perceived it differently, “I was proud. I think we did a great job of helping the family cope with the inevitable … I am comfortable with the fact that there are limits to what we can do for people.” Another oncologist agreed, “I think that helping the patients and families through this ordeal, if it's done well, is really satisfying.”

Emotions Generated

All oncologists described sadness and relief as the predominant emotions they experienced in response to patient deaths. However, they differed in what they perceived to be the most disturbing aspects of the patient death. Some described being disturbed by the loss of relationship with the patient. One participant stated, “not having that time was the most difficult, some preparation for family, for doctor, for patient-that was the most difficult aspect.”

In contrast, others were disturbed by issues related to the patient's disease process and reported a sense of failure. One male participant stated, “the most disturbing thing was that I wasn't able to give her a long period of nonintervention.” In the words of another, “I mean it's always sad when people die in transplant, but it's a more generic sort of it's too bad we couldn't have done more for them.”

Collegial Support

Oncologists varied in their tendency to seek out and receive support from colleagues. One female oncologist stated; “People are very supportive when someone has lost a patient … we recognize that it's sad for us too.” Others did not describe needing, asking for, or receiving support from colleagues. In response to the question of why he didn't ask for support from colleagues, one participant stated: “I guess I have become pretty good at keeping things compartmentalized.”

Descriptions of Communication with Patient and Family

We found differences in how physicians described the quality of communication in their encounters with patients and families. Approximately half of the participants could tell us what and how they communicated either by relating, in detail, an encounter or by describing a schema or method for discussing goals of care. For example, participants either stated: (1) “I usually do it this way …” or (2) clearly described an encounter with a patient in a manner that demonstrated a method of communication in which the patient was told they were dying in a manner that was clear yet sensitive to the patient's desire for information. For example, one male oncologist described his discussions with a dying patient on his ward service,

The first night, I said “you know how serious this is?” and he said, “yeah, I know how serious this is. I want to do everything I possibly can, but I know this is a bad situation.” And the family was taking it quite hard, but also recognized that we were doing everything humanly possible to help him. And then [I told him] at some point there would come a time when the technology would become his enemy rather than his friend, and “you know, we may be there now.” I think they came to that realization quite soon … I think that was part of the process of acceptance with them. It was realizing that we weren't somehow giving up on him, but that we were not going to hurt him more.

Other participants neither described a discernable method of communicating in a specific patient encounter nor related a usual approach to these types of discussions. For example, one participant, when asked about discussions about EOL issues with the patient, stated, “I believe that she knew that it was pretty serious.” It is possible that these oncologists did have a developed method of communication; however, this was not evident in their account of their most recent patient death.

Methods of Communication

The oncologists who described a clear method of communicating with patients and families about transitioning goals of care at the EOL had approaches that, although varied, shared some common features: (1) the belief that conversations are a process; (2) a sense of responsibility for making recommendations; (3) the use of an individualized approach that took into account the patient's and family's value system; and (4) the use of experimentation, reflection, and role models in the development of their communication method.

Conversations are a process: “The cat's on the roof”

One male oncologist used a joke called “the cat's on the roof” (Table 4) to illustrate the point that conversations about transitioning goals of care are a process. He stated,

Table 4.

“The Cat's on the Roof” Joke as Told by One Participant

| A man goes on a long trip and entrusts his brother with the care of his cat. When he returns, he calls his brother: “I am back, I had a great time. How are things?” And the brother says, “Your cat died.” And the other brother says “What kind of thing is that to say to me; the cat died? I mean, that's not the way you break bad news.” And the brother says, “How should I have told you?” And he says “Today, when I called you, you should have said ‘the cat is on the roof and I have to call the fire department to get the cat down.’ and the next day when I call you, you say ‘well, the fire department came, and they got the cat down, but the cat looked quite poorly, so I took the cat to the vet.” The next day when I call, you say ‘well, the vet actually says that the cat is very sick and I am not sure how things are going to turn out.” and the last day when I call you, you say ‘well, the vet did everything he could possibly do, but the cat died.” And the brother says, “Okay, now I understand better how to give bad news. I learned my lesson.” And then he says, “Now, tell me, how's mom?” And the brother says, “Well, mom is on the roof.” |

I don't hide anything, but for those people who don't necessarily want to get those kinds of details in their first visit … we sort of work through it … over the course of days, maybe weeks, talk about those things. I don't necessarily try to get everything across the first time that there is major change.

Another oncologist used this approach as well, “his wife and children had very little time to make peace and so it really took repeated conversations with them individually to try to explain.”

Make recommendations

Oncologists who described a developed method of communication made recommendations, informed by their own personal and professional experiences, to patients and families. One stated, “Never ask the family, ‘Do you want us to do everything for your loved one?’ It's a dumb question, you know. Everybody in their right mind would say ‘of course,’ but rather take back the medical ownership of this decision.” Another oncologist described his method of making a recommendation, “I tend not to make it a Chinese menu or give a lot of choice. I tell them: ‘It wouldn't be our plan to do that and do you agree?’ And try to help them along with it.”

Patient-based approach

These oncologists described attempts to understand the patient's value system and tailored their communication method to meet the needs of the patient and family. One female oncologist described her role in helping a family from a cultural background different from her own understand appropriate goals of care for their daughter who was brain-dead, “I don't assume their wishes would be the same as mine under those circumstances.” Another oncologist describes his dismay when his patient came to clinic appointments without her husband, “It's not the way I would have done it. I mean, I'd rather have my spouse there. But she is entitled to do it any way she wanted to.” In the words of another participant: “the same recipe doesn't work for every patient.”

Evidence of experimentation

Physicians did describe using experimentation, both positive and negative role models, and self-reflection in the process of developing their method of communication. One senior male oncologist describes his process of learning communication, “[I used] Trial and error. Use of … a few models of whom I thought did well. Many more models who I thought had done terribly and realizing how not to do it.” Another senior male oncologist reflected on how his method has evolved, “I've changed my approach. Years ago … [I used to say] ‘You know, these are the things that could happen, what would you like to do?’ And I found that I rarely got a straight answer from patients…. I think you confuse them, it's sort of a terrifying way to present that way to them … it sort of evolved to saying to them these are the issues, you are sick and … it is important that we discuss it so that things are not done that you don't want done.”

No Description of a Clear Method of Communication

A number of the oncologists in our sample did not describe a clear method of discussing transitioning goals of care. These oncologists did not seem to feel they could impact patients' and families' coping with and acceptance of death and made few recommendations. One oncologist described his discussions with a patient whose disease was not responding to chemotherapy, “He talked about it more than I did. He asked me ‘what are we going to do if this doesn't work?’ And after we got to the third or fourth choice, I just sort of didn't answer him. So he sort of knew. We didn't talk about it terrifically well.” Another oncologist stated, “We did not have frequent discussions, but based on the sub-context of what our discussions were, I mean, she knew.” In the words of another, “Toward the end of his life, I think it became obvious to the family that he was going to pass away.”

Inability to effect change

Oncologists who did not describe a clear method of communication spoke of the frustration and helplessness of not being able to influence the outcome in difficult situations despite an intense desire to do so. One oncologist describes his attempts to have a patient referred to hospice although there was no mention of his discussing this with the patient, family, or inpatient care team, “I felt as if I was fighting a tide as a far as I kept writing in my notes we really should just consider hospice. I really didn't want to do very much because I knew it didn't really matter.”

Few recommendations

Oncologists without a clear method of communication made few recommendations to patients and families. An oncologist described the difficult time a family member was having coping with the illness of her parent, “I think she was being asked to make too many decisions.” Another oncologist stated, “[the family] were really the ones who initiated the withdrawal of care discussion and made that decision in the end.”

Role, Relationship, Collegial Support, Satisfaction, and Communication Style

Through repeated reading and coding of the transcripts, we noted that the above themes appeared to track together. For example, we observed that those oncologists who conceptualized their role to include both psychosocial and biomedical care also described close relationships with patients, satisfaction with the EOL care that they provided, and asking for and/or receiving collegial support. Furthermore, we noted that these oncologists, who represented roughly half of the sample, focused on the communication process as a central aspect of care. Unlike their counterparts, they spontaneously provided explicit descriptions of their methods of communication with patients and families.

The groups of physicians who did and did not describe a method of communication were roughly equal in terms of the number of deaths that were expected, the number of oncologists who served in the capacity of ward attending for the patient, and the number of women. Those with a clear method of communication, however, did contain fewer descriptions of BMT-related deaths (1 versus 4) and did contain oncologists with a greater mean number of years in practice (14 versus 9). Physicians who described explicit communication responded to the Maslach burnout instrument in a pattern that suggests lower burnout (e.g., lower on emotional exhaustion and depersonalization, and higher on personal accomplishment) than did oncologists with less explicit communication.

Discussion

In our study of a random sample of oncologists, we found that physicians who embraced a broader perspective on the physician role, encompassing both biomedical as well as psychosocial aspects of care, tended to describe a clearer method of communication about EOL care, and reported a sense of empowerment to positively influence patient and family coping with and acceptance of the dying process. The method of communication used by these oncologists was based on an understanding that patients and their families benefit from approaching EOL decisions as a process involving multiple conversations over time, rather than expecting them to be emotionally prepared to confront and come to closure on these difficult decisions in one visit. During communication about EOL care, these oncologists made recommendations using an individualized approach that was derived from an understanding of the characteristics and values unique to the patient and family even when these were different from their own. Participants with a broad view of their role and a clear method of communication did not view progression of the disease as a personal failure and did view the provision of effective EOL care as very satisfying.

In contrast, participants who described primarily a biomedical role reported a more distant relationship with the patient and family, a sense of failure at not being able to alter the course of the disease, an absence of collegial support, and they did not describe a clear method of communication. In their descriptions of communication encounters with patients and families, these physicians did not believe that they could effect change in the psychosocial situation, and made few recommendations about treatment options.

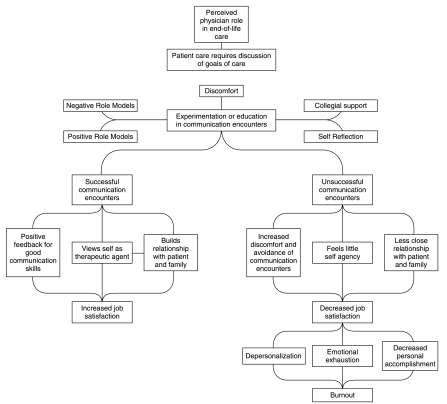

Conceptual Model: Communication is not “See One, Do One, Teach One”

Our results suggest to us a potential conceptual model to describe the relationship between communication competence to job satisfaction and physician burnout (Fig. 1).

FIG. 1.

Conceptual model of the relationship between perceived physician role and the development of skills in end-of-life communication.

The professional role of an oncologist requires communicating with patients and families about treatment preferences and goals of care from the time of diagnosis until death. Physicians often experience tremendous discomfort in first attempts to communicate with dying patients. Unlike other skills in medicine in which the old adage “see one, do one, teach one” may apply, communication often requires multiple attempts and frequent failures until the skill is honed to the point where it is both effective and compassionate. We hypothesize that this experimentation is made both easier and more fruitful for the physician if supportive colleagues, role models, and times for reflection are available. If attempts at communication continue to be unsuccessful, such failures may lead to increased discomfort and avoidance of explicit communication with patients and families, resulting in decreased investment in the physician-patient relationship, an increased emphasis on the importance of cure, and decreased job satisfaction, possibly leading to burnout. In contrast, achieving success in these challenging communication tasks may allow the physician to begin to view him or herself as a therapeutic agent who has the ability to positively impact the psychosocial care of the patient and family, regardless of the medical outcome. Through effective communication with patients and families, physicians are likely to build closer relationships. Supportive colleagues, viewing oneself as a therapeutic agent, and a closer relationship with patients and families could all contribute to increased job satisfaction and decreased burnout.10–12

Our conceptual model of the development of communication skills and their relationship to job satisfaction and burnout has features in common with models used by adult learning theorists such as Schon, Meizrow, and others to explain the processes of professional growth and development in adult-hood.13–16 These theorists suggest that a learner's ability to identify, conceptualize, and describe a complex task like communication allows the learner to experiment in an intentional way that supports continued skill development, resulting in increased satisfaction with work tasks. It is interesting that none of the oncologists in our study described learning communication in any formalized educational venue, despite the availability of useful educational programs and tools.18,19

Our qualitative results also suggest a potential relationship between an oncologist's methods of communication with dying patients and job satisfaction and burnout. Oncologists with a clear method of communication appeared to be more satisfied with the care they provided to dying patients and less burned out. However, oncologists with an explicit method of communication had been in practice a greater number of years. While it would be inappropriate to generalize from this sample size, we found this clustering of themes intriguing; if confirmed, these observations suggest several interesting hypotheses about factors that could influence a physician's job satisfaction and burnout.

We hypothesize that with more experience oncologists may develop more effective methods of communication that contribute to increased satisfaction. It could also be that oncologists who do not develop effective methods of communication either stop communicating, constrict their role only to the biomedical, or leave clinical oncology entirely at an early stage in their careers.

Limitations

Our study is limited in several ways. First, it is possible that oncologists did not accurately recall elements of the patient experience or their own responses; however, the reality of the clinical scenario appears to be less important than the perceived events and their actual emotional impact on the physician which was well-elucidated from the in-depth interview. Second, this study was conducted at two highly specialized referral institutions, which may limit generalizability to physicians practicing in other settings. Third, physicians' descriptions of care may not be the same as the care that was actually delivered, and the case analyzed in this study may not be representative of the physician's usual pattern of care. Fourth, we have no data about patient satisfaction with those physicians who described a clear method of communication. Recent studies of patient preferences about communication in the context of cancer treatment and during the terminal phase of the illness, however, suggest that patients value an approach that is clear and that includes recommendations by the physician.21,22 Finally, although appropriate for a qualitative study, a sample of 18 participants limits our ability to make statistical comparisons between groups. It does, however, provide clear suggestions for future well-designed quantitative research.

Implications

The next step in our work will be to assess the conceptual relationships described in the proposed model in a larger group of oncologists. Further work is needed to develop quantitative measures of physician role, which can be used, in conjunction with systematic methods of assessing communication,23 to explore whether and how these factors are related to physician outcomes (e.g., job satisfaction and retention and burnout) and patient outcomes (e.g., satisfaction, referral to hospice).

The results of this study may also be useful in crafting educational interventions for oncologists and other physicians who often manage complex EOL communication encounters with patients. If physicians who use a process-oriented approach to communication are found to have decreased burnout and increased job satisfaction and retention, a communication intervention targeting physicians early in their careers may be beneficial.24,25 It is possible that providing communication training to physicians early in training (e.g., oncology fellows) may not only improve patient care, but also may improve job satisfaction and job retention among oncology junior faculty.

Appendix A

Survey Instrument for Most Recent Patient Death Read to Respondent:

This study is an effort to learn about physicians' emotional reactions to patients' deaths. Please take a few minutes to read over the consent form. It explains in more detail what this study is about. Feel free to ask about anything that concerns you.

Subject reads consent and signs it.

There are three parts to this interview. First, I'm going to ask you some questions about ________ 's death. In the second part I'd like you to fill out a brief survey, and then I'm going to ask you some questions about the most emotionally powerful patient's death that you've experienced.

Please feel free to ask for clarifications as we move along.

Before I begin, have any of your patients died since the death of ______ ?

Do you have any questions before I start?

A. Contextual and Background Information: Open-Ended Questions

FOR RESIDENTS ONLY

“Did you consider assigning a medical student to this patient? How did you decide to assign [or not assign] this case/pt to the medical student?

In this study, we're interested in understanding the experiences, perceptions, and observations of physicians as they go through a terminal illness and death with a patient for whom they are caring. In particular, we would like to learn more about your experience with the death of ______.

- A1. Please start by telling me the story of ______'s illness and death:

Explore: Circumstances surrounding patient's death Physician–patient relationship Goals of treatment during terminal hospitalization: how did they change over time? Level of involvement with patient's dying process and death Closeness and identification with the patient Nature and extent of communication with patient about death and dying Nature and extent of communication with patient's family about death and dying Issues with patient's family A2. What was the patient's cause of death?

- A3. Now, I'd like to hear about how ______'s death affected you. Please take me through the sequence of your own reactions to ______'s death:

Explore: Emotions generated Persistence of emotional response Coping response Need for support a) if the respondent speaks about having spoken to colleagues, probe where and the topic b) ask if they spoke to attending rounds about the pt after their death c) ask what did you learn from the attending about caring for dying pts Subsequent changes in behavior with patients (in general ; & in the week following pt's death) Impact on thoughts/attitudes about death as it relates to care of dying patients. - A4. Looking back on your care of ______, is there anything that you would have done differently?

- Probes:

- Diagnosing/evaluation

- Prescribing

- Communication

- Procedures carried out

- Persistence of regrets, second thoughts

- A5. “Were there things about ______ that enhanced your relationship?”

Codes:

- □ PATIENT DISEASE WAS INTERESTING

- □ PATIENT'S PERSONALITY

- □ PATIENT'S AGE

- □ PATIENT REMINDED ME OF SOMEONE I CARE ABOUT

- □ PATIENT'S MODE OF COPING WITH DEATH

- □ PATIENT ABLE TO COMMUNICATE HIS/HER FEELINGS

- □ PT HAD GOOD SENSE OF HUMOR

- □ PATIENT WAS COURAGEOUS

- □ PATIENT'S SPIRITUAL/RELIGIOUS BELIEFS

- □ I HAD A LONG TERM RELATIONSHIP WITH THE PATIENT.

- □ PATIENT HAD A SIMILAR SOCIO-ECONOMIC STATUS

- □ I HAD A LONG TERM RELATIONSHIP WITH THE PATIENT'S FAMILY.

- □ NONE

- □ OTHER (PLEASE DESCRIBE) __________________

- A6. “Were there things about ________ that created barriers to your relationship?”

Codes:

- □ TOO MUCH LIKE ME

- □ PATIENT NOT ABLE TO COMMUNICATE

- □ TOO SHORT A RELATIONSHIP

- □ PERSONALITY PROBLEMS IN THE PATIENT

- □ PT HAD UNREASONABLE EXPECTATIONS

- □ BEHAVIOR HARMFUL TO HEALTH

- □ SPIRITUAL/RELIGIOUS BELIEFS

- □ TREATMENT NONADHERENCE/NONCOMPLIANCE

- □ TOO DIFFERENT FROM ME

- □ NOT ENOUGH TIME

- □ STAFF CONFLICT

- □ AGE

- □ CONFLICT WITH FAMILY

- □ NONE

- □ OTHER (PLEASE DESCRIBE) ______

A7. “What aspect(s) of this experience was/were most disturbing for you?”

A8. “What aspect(s) of this experience was/were most satisfying for you?”

A9. In what ways was this an emotionally powerful death for you?

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by a grant from the Nathan Cummings Foundation. During the preparation of this manuscript, Dr. Jackson was supported by a National Cancer Institute research-training grant. Dr. Mack was supported by an AHRQ research training grant. Dr. Arnold was a Faculty Scholar of the Open Society Institute's Project on Death in America and is supported by the LHAS Trust.

References

- 1.Institute of Medicine. Improving Palliative Care for Cancer. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press; 2001. pp. 36–36. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ramirez AJ. Richards MA. Cull A. Gregory WM. Leaning MS Snashall DC. Timothy AR. Burnout and psychiatric disorder among cancer clinicians. Br J Cancer. 1995;71:1263–1269. doi: 10.1038/bjc.1995.244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kash KM. Holland JC. Breitbart W. Berenson S. Dougherty J. Ouellette-Kobasa S. Lesko L. Stress and burnout in oncology. Oncology. 2000;14:1621–1637. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Grunfeld E. Whelan TJ. Zitzelsberger L. Willan AR. Montesanto B. Evans WK. Cancer care workers in Ontario: Prevalence of burnout, job stress and job satisfaction. CMAJ. 2000;163:166–169. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Whippen D. Canellos G. Burnout syndrome in the practice of oncology: Results of a random survey of 1,000 oncologists. J Clin Oncol. 1991;9:1916–1920. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1991.9.10.1916. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Redinbaugh EM. Sullivan AM. Block SD. Gadmer NM. Lakoma M. Mitchell AM. Seltzer D. Wolford J. Arnold RM. Doctors' emotional reactions to recent death of a patient: Cross sectional study of hospital doctors. BMJ. 2003;327:185–191. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7408.185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pope C. Ziebland S. Mays N. Qualitative research in health care. Analysing qualitative data. BMJ. 2000;320:114–116. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mays N. Pope C. Qualitative research in health care. Assessing quality in qualitative research. BMJ. 2000;320:50–52. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7226.50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Strauss A. Corbin J. Basics of Qualitative Research: Grounded Theory Procedures Techniques. Newbury Park: Sage Publications; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peteet JR. Murray-Ross D. Medeiros C. Walsh-Burke K. Rieker P. Finkelstein D. Job stress and satisfaction among the staff members at a cancer center. Cancer. 1989;64:975–982. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(19890815)64:4<975::aid-cncr2820640434>3.0.co;2-w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Shanafelt TD. Sloan JA. Habermann TM. The well-being of physicians. Am J Med. 2003;114:513–519. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(03)00117-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Meier DE. Back AL. Morrison RS. The inner life of physicians and care of the seriously ill. JAMA. 2001;286:3007–3014. doi: 10.1001/jama.286.23.3007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Schon DA. New York: Basic Books; 1983. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Knowles M. Holton E. Swanson R. Human Resource Development. Woburn, MA: Butterworth-Heinemann; 1998. The Adult Learner: The Definitive Classic in Adult Education. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meizrow J. Fostering Critical Reflection in Adulthood: A Guide to Transformative and Emancipatory Learning. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kegan R. Lahey L. How the Way We Talk Can Change the Way We Work: Seven Languages for Transformation. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Baile W. Buckman R. Lenzi R. Glober G. Beale E. Kudelka A. SPIKES—A six-step protocol for delivering bad news: Application to the patient with cancer. Oncologist. 2000;5:302–311. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.5-4-302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Baile W. Lenzi R. Parker P. Buckman R. Cohen L. Oncologists' attitudes toward and practices in giving bad news: An exploratory study. J Clin Oncol. 2002;20:2189–2196. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2002.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Back AL. Arnold RM. Tulsky JA. Baile WF. Fryer-Edwards KA. Teaching communication skills to medical oncology fellows. J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:2433–2436. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.09.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Program in Palliative Care Education and Practice. The Harvard Medical School Center for Palliative Care. www.hms.harvard.edu/cdi/pallcare/ [Jun 30;2008 ]. www.hms.harvard.edu/cdi/pallcare/

- 21.Wenrich MD. Curtis JR. Shannon SE. Carline JD. Ambrozy DM. Ramsey PG. Communicating with dying patients within the spectrum of medical care from terminal diagnosis to death. Arch Intern Med. 2001;6:868–874. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.6.868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wright EB. Holcombe C. Salmon P. Doctors' communication of trust, care, and respect in breast cancer: Qualitative study. BMJ. 2004;328:864–867. doi: 10.1136/bmj.38046.771308.7C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Roter DL. Larson S. Fischer GS. Arnold RM. Tulsky JA. Experts practice what they preach: A descriptive study of best and normative practices in end-of-life discussions. Arch Intern Med. 2000;160:3477–3485. doi: 10.1001/archinte.160.22.3477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Fallowfield L. Jenkins V. Farewell V. Saul J. Duffy A. Eves R. Efficacy of a cancer research UK communication skills training model for oncologists: A randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2002;359:650–656. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)07810-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fallowfield L. Jenkins V. Farewell V. Solis-Trapala I. Enduring impact of communication skills training: Results of a 12-month follow up. Br J Cancer. 2003;89:1445–1449. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]