Abstract

We present a sixth order explicit compact finite difference scheme to solve the three dimensional (3D) convection diffusion equation. We first use multiscale multigrid method to solve the linear systems arising from a 19-point fourth order discretization scheme to compute the fourth order solutions on both the coarse grid and the fine grid. Then an operator based interpolation scheme combined with an extrapolation technique is used to approximate the sixth order accurate solution on the fine grid. Since the multigrid method using a standard point relaxation smoother may fail to achieve the optimal grid independent convergence rate for solving convection diffusion equation with a high Reynolds number, we implement the plane relaxation smoother in the multigrid solver to achieve better grid independency. Supporting numerical results are presented to demonstrate the efficiency and accuracy of the sixth order compact scheme (SOC), compared with the previously published fourth order compact scheme (FOC).

Keywords: convection diffusion equation, Reynolds number, multigrid method, Richardson extrapolation, sixth order compact scheme

1 Introduction

In this paper, we consider the three dimensional (3D) convection diffusion equation as

| (1) |

for a specified forcing function f in a continuous domain Ω of a 3D space with suitable boundary conditions prescribed on ∂Ω. Here Ω is assumed to be comprised of a union of rectangular solids. Functions p, q, r, f, and u are assumed to be continuously differentiable and have the required partial derivatives on Ω.

Eq. (1) is widely used to model the transport processes, including heat transfer and fluid flows [19, 24]. It describes the convection and diffusion of various physical quantities, e.g., momentum, heat, material concentrations, etc. The functions p, q, and r in Eq. (1) are convection coefficients, whose magnitude is usually referred to be the Reynolds number in literature. When the Reynolds number is bigger than one (large convection coefficients), Eq. (1) is considered as convection dominated and is difficult to solve numerically [35, 38].

Compared with lower dimensional problems, the numerical simulation of 3D problems tends to be computationally intensive because it requires much more memory space and CPU time to obtain solutions with desired accuracy. So the direct solution methods based on Gaussian elimination are not widely used because they scale poorly with the problem size when the memory space and computational cost become an issue [4]. Thus iterative solution methods are considered as the best choice in such situations. For the convection dominated problems, traditional iterative methods may fail to converge for solving the linear systems arising from the second order central difference scheme (CDS) and the CDS scheme may produce nonphysical oscillations for large Reynolds number. The upwind difference scheme is usually stable but it will reduce the order of accuracy to the first order.

One approach to reducing computational cost, keeping good numerical stability and yielding high accuracy approximations is to utilize the higher order discretization schemes. Although the higher order discretization schemes need more complex procedures to compute the coefficient matrix, they use relatively coarser mesh griddings to achieve approximate solutions of comparable accuracy, compare to the lower discretization schemes using finer mesh griddings. The higher order schemes are reported to be efficient [1, 11, 13] and some of them may have an additional advantage of suppressing nonphysical numerical oscillations [30]. For 3D convection diffusion equation and Poisson equation, there have been several reported papers on using higher order discretization schemes [3, 12, 25, 37].

However, sixth order compact approximation for the 3D convection diffusion equation is still an open question. Compared with implicit compact schemes, the high order explicit compact schemes are more complicated to develop in higher dimensions. As far as we know, there is no existing explicit compact scheme on a single scale grid that is higher than fourth order for the 3D convection diffusion equation. One possible approach is to use the multiscale grid computation combined with an extrapolation technique. For the two dimensional (2D) case, we have developed the sixth order accuracy compact scheme to solve the Poisson equation and convection diffusion equation [31, 32]. It was found that the sixth order scheme is computationally more efficient than the fourth order scheme. To obtain a computed solution of given accuracy, the sixth order scheme uses less memory and computational cost than the fourth order scheme does. Since there has been no such sixth order compact scheme for the 3D convection diffusion equation, the aim of this paper is to fill this gap.

This paper is organized as follows. In Section 2, we introduce the standard explicit fourth order compact finit difference scheme and our operator based interpolation scheme to approximate the sixth order fine grid solution. Section 3 contains the solution strategies for the resulting linear systems, including the multiscale multigrid method, plane relaxation smoother, and the residual scaling technique. Supporting numerical results are provided in Section 4. Conclusions remarks are given in Section 5.

2 Finite Difference Scheme

Our sixth order compact (SOC) finite difference scheme is based on the fourth order compact (FOC) discretization scheme. We first use multiscale multigrid method to compute the converged fourth order solutions on both the fine grid and the coarse grid. Then an operator based interpolation scheme combined with the Richardson extrapolation technique is used to approximate the sixth order fine grid solution. In this paper, we use the FOC scheme from Zhang’s paper [37].

2.1 Fourth Order Discretization

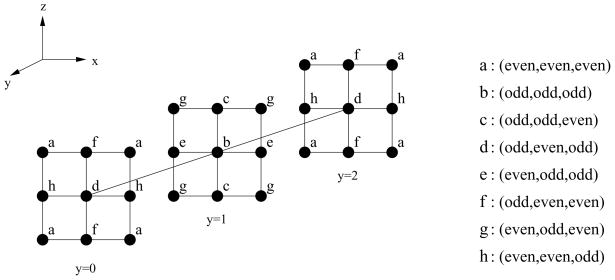

We assume the discretization is done on an uniform grid with meshsize h. We use u0 to denote the approximate value of u(x, y, z) at an internal mesh point (i, j, k). The approximate values of its immediate 18 neighboring points are denoted by ul, l = 1, 2, …, 18, as in Fig. 1. The 8 corner points, which are the white colored points in Fig. 1, are not used in the finite difference scheme. The discrete values of pl, ql, rl and fl for l = 0, 1, …, 6, are defined similarly.

Figure 1.

Labeling of the 3D grid points in a unit cube.

Zhang’s explicit fourth order compact scheme for Eq. (1) is derived from the general implicit formula by Ananthakrishnaiah et al. [3], which yields a 19-point formula as

| (2) |

where the coefficients αl and the right hand side F0 are given by

If we set the convection coefficients p = q = r ≡ 0, Eq. (1) will be reduced to 3D Poisson equation. The 19-point formula for the 3D Poisson equation can be reduced from the Zhang’s fourth order scheme. It has been developed by several authors like Kwon et al. [15], Spotz and Carey [25].

We call the FOC scheme “compact” because it only involves the 18 neighboring grid points nearest to the reference grid point in a unit cube. Eq. (2) can be used for every grid point in a rectangular domain with Dirichlet boundary condition, no special formulas are needed for approximations at grid points near the boundaries.

By using Eq. (2), for every discrete grid point, we obtain a system of linear equations

| (3) |

Generally, the coefficient matrix A is very large and sparse. It is nonsymmetric and non-positive definite if the convection coefficients are nonzero. When the convection diffusion equation is convection dominated, the matrix A loses its diagonal dominance. Even without the diagonal dominance, our previous work showed that there is no stability difficulty with the FOC scheme for both the 2D and 3D convection diffusion equations, and the multigrid method converges by using efficient smoothers and residual scaling techniques [11, 32, 34].

2.2 Operator Based Interpolation and Extrapolation

For 2D Poisson equation and convection diffusion equation, we proposed an operator based interpolation scheme combined with extrapolation technique to approximate the sixth order accurate fine grid solution [31, 32]. The numerical results show that our interpolation scheme is very efficient and accurate for the 2D problems.

The interpolation scheme for 2D problems is an iterative procedure combined with the Richardson extrapolation technique, which updates the solutions of grid points by groups in each iteration. For the 3D convection diffusion equation, the basic idea of the interpolation scheme is almost the same as for the 2D problems, but it needs more complicated grouping strategy. Like in Fig. 2, we divide the fine grid points into eight different groups by their odd or even indexing in the x, y and z-coordinate directions. Group a contains the (even, even, even) grid points on the Ωh grid, which are the corresponding grid points on the Ω2h coarse grid.

Figure 2.

Group information of 3D grid points in a unit cube.

By solving the system of linear equations arising from the FOC scheme, we can get the fourth order solutions and on Ωh and Ω2h, respectively. For the sixth order accurate solutions, it is easy to approximate the solution for the coarse grid Ω2h by using the Richardson extrapolation like [6, 21]

| (4) |

Here, m is the order of the computed solution accuracy from the FOC scheme. From [32], we know that the magnitude of the convection coefficients will affect the value of m. Generally, when the convection diffusion equation is diffusion dominated (small convection coefficients), we assume m = 4. If the convection diffusion equation is convection dominated (large convection coefficients), we need to compute the exact order of solution accuracy from the FOC scheme to use the Richardson extrapolation.

For the sixth order fine grid solution, we first directly interpolate the sixth order coarse grid solution to the corresponding grid points in group a. Then we use an iterative mesh refinement interpolation technique to approximate sixth order solutions for the fine grid points in other groups. The detail of one iteration (from step n to step n+1) is outlined in Algorithm 2.2.

Algorithm 2.2: Sixth order operator based interpolation scheme for 3D convection diffusion equation

Let .

If n = 0, goto Step 3, else goto Step 4.

-

Update every grid point in group a on Ωh.

From and , we first compute by Eq. (4). Then we use direct interpolation to obtain .

-

Update every grid point in groups c, d, and e on Ωh.

For group c: (odd, odd, even) grid point (xi, yj, zk).

The updated solution is approximated from Eq. (2) asHere, Fi,j,k represents the right-hand side part of Eq. (2). The sixth order solutions for grid points in groups d and e are approximated similarly like those in group c. Each grid point in these three groups has 4 neighboring fine grid points in group a.

-

Update every grid point in groups f, g, and h on Ωh.

For group f: (odd, even, even) grid point (xi, yj, zk).

The updated solution is computed asThe sixth order solutions for grid points in groups g and h are approximated similarly like those in group f. Each grid point in these three groups has 2 neighboring fine grid points in group a.

-

Update every grid point in group b on Ωh.

For group b: (odd, odd, odd) grid point (xi, yj, zk).

The updated solution is computed asEach grid point in group b has no neighboring fine grid points in group a.

Compute the 2-norm . If R is bigger than a certain tolerance (10−10 in this paper), go back to Step 1.

In Algorithm 2.2, Ai,j,k(l), l = 0, 1, …, 18, are the pre-computed coefficients for grid point (xi, yj, zk). and denote the fourth order accurate solution space from the FOC schemes, and are the improved sixth order accurate solution space. ũh,n is the approximate solution for the fine grid after the n iterations. We update the fine grid points group by group based on the number of their neighboring grid points with sixth order solution (group a) from Step 2. Grid points in groups c, d and e have more qualified neighbors than those in other groups, so we update these three groups first. The iteration will continue until the 2-norm R of the correction vector is reduced to below a certain tolerance.

3 Solution Strategies

For solving the system of linear equations arising from the FOC scheme, it is well known that classical iterative methods like the Jacobi, Gauss-Seidel and SOR converge slowly for large linear systems. For the 2D convection diffusion equation, we proposed a multiscale multigrid method which has been shown to be very efficient and stable [32]. This method can also be used to solve the 3D convection diffusion equation.

3.1 Multiscale Multigrid Method

The multigrid method is among the fastest and most efficient iterative methods for solving linear system arising from the discretized PDEs. The multigrid method iterates on a hierarchy of successively coarser grids until the convergence is reached. For model problems, such as the idealized elliptic problems, the convergence rate of the multigrid method is independent of the grid size [5, 7, 33]. Various multigrid implementation strategies with the FOC scheme to solve the 2D and 3D convection diffusion equations are discussed in [11, 23, 34].

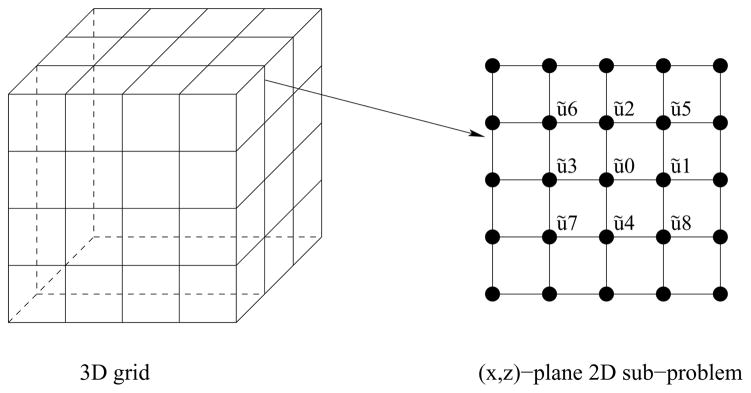

Our multiscale multigrid method is based on the standard multigrid V-Cycle [22]. The V-Cycle is the computational process that goes from the fine grid down to the coarsest grid and then comes back from the coarsest grid up to the fine grid. From Fig. 3, we can see that the multiscale multigrid method is similar to the full multigrid method, but we do not start from the coarsest grid level. We describe it in Algorithm 3.1 as below:

Figure 3.

Representation of multiscale multigrid method for 3D convection diffusion equation.

Algorithm 3.1: Multiscale multigrid method

Run the multigrid V-Cycle on 4h grid for one or two cycles to get an approximate solution u4h.

Use high order interpolation scheme to interpolate u4h to 2h grid as the initial guess.

Run the multigrid V-Cycle on 2h grid until it converges to get 4th order solution u2h.

Use high order interpolation scheme to interpolate u2h to h grid as the initial guess.

5: Run the multigrid V-Cycle on h grid until it converges to get 4th order solution uh.

3.2 Relaxation Strategies in Multigrid Method

Standard multigrid method with point Gauss-Seidel relaxation is known to be highly efficient in solving systems of elliptic partial differential equations, but it fails to achieve optimal grid independent convergence rate for some convection diffusion equations like the convection dominated problems with high Reynolds number and the Poisson equation that has anisotropic discrete operators [11, 16, 17, 34]. There are at least two strategies to treat linear systems arising from these equations. The first strategy is to use semicoarsening, ie., mesh coarsening is only performed along the dominated direction. The second strategy is to use alternating (x − y) line Gauss-Seidel relaxation in the multiscale multigrid method for solving these 2D problems [31, 32] and use alternating plane relaxation smoother for these 3D problems. In this paper, we prefer to use the second one.

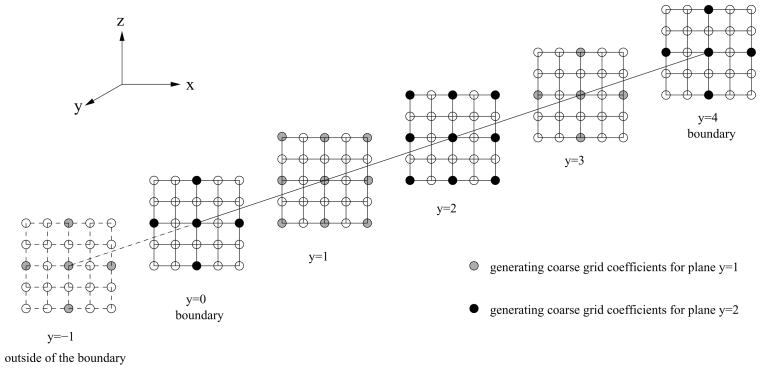

The alternating (x − y − z) plane Gauss-Seidel relaxation in lexicographic order performs one sweep of (y, z)-plane Gauss-Seidel relaxation along the x-coordinate direction first, followed by one sweep of (x, z)-plane Gauss-Seidel relaxation and (x, y)-plane Gauss-Seidel relaxation along the y-coordinate direction and z-coordinate direction, respectively. For each direction, we divide the 3D problem into N 2D sub-problems as in Fig. 4, where N is the number of intervals along that direction. Let us first consider the (x, z)-plane 2D sub-problem, its nine point computational stencil can be generated from the Eq. (2) as

Figure 4.

2D sub-problem in plane relaxation.

| (5) |

where the coefficients Al and the 2D solution ũl (l = 0, 1, …, 8) are set as

The nine point computational stencil for the (x, y) and (y, z)-planes can be generated like Eq. (5) similarly, but the index of the 3D grid points for those corresponding 2D grid points are different.

The plane relaxation is considered in the multigrid literature to have poor numerical and parallel properties because it needs to solve a large number of 2D sub-problems. However, it is shown in [16] that an exact solution of the 2D sub-problems for planes is not needed and that one multigrid cycle is sufficient if we use multigrid method as the inner 2D solver. This behavior has been also reported by other researchers in [18, 29].

We would like to mention here that if we use the geometric multigrid method as the inner 2D solver to solve the 3D convection diffusion equation with variable coefficients, for some 2D planes, we are not able to compute the full coefficient matrix for their coarse grids. For example in Fig. 5, we consider a 5 × 5 × 5 3D grid. The 19 black color grid points are the coarse grid points that are needed for plane y = 2 to compute its nine point computational stencil by Eq. (5). In comparison, the 19 gray color grid points are the coarse grid points needed for plane y = 1. We note that, plane y = 1 needs some coarse grid points from plane y = −1, which is not in the 3D cube, to generate its coarse grid coefficient matrix for solving the 2D sub-problem. Due to these drawbacks, we can only use the multigrid method as the inner 2D solver in plane relaxation for solving the 3D convection diffusion equation with constant coefficients. If we rewrite the Eq. (2) by using constant coefficients p, q, and r, the coefficients for each plane along the same direction are the same. For plane y = 1 in Fig. 5, we do not need the additional information from plane y = −1, because every plane along the y direction has the same coarse grid coefficients.

Figure 5.

coarse grid of the 2D sub-problem in plane relaxation.

In order to keep the optimal convergence rate, for the inner 2D multigrid solver, we use alternating line relaxation smoother in the 2D V-Cycle because the 2D sub-problem may still have the high convection operator or the anisotropy.

3.3 Residual Scaling

From [34, 36, 39], we also know that merely using line relaxation in standard multigrid method still cannot give us the fast convergence for convection dominated 2D problems with relatively large Reynolds number. One simple approach is to properly scale the residual before it is projected to the coarse grid. We believe this approach combined with the plane relaxation can build a more efficient and scalable solver for the 3D convection diffusion equation with large Reynolds number.

The residual scaling procedure at the grid point (xi, yj, zk) is like

Here, ri,j,k is the computed residual at the grid point (xi, yj, zk), r̃i,j,k is the residual after scaling, and β is a user input scaling factor to scale the residual. Readers are referred to [11, 39] for more details about how to choose the correct scaling factor. In this paper, we only list the optimal numerical results we got by testing different scaling factors.

4 Numerical Experiments

In our numerical experiments, we tested the sixth order scheme (SOC) and compared the results with the standard fourth order scheme (FOC). All computations were done on one processor of an IBM HS21 blade cluster at the University of Kentucky using Fortran 77 programming language. The processor has 2GB local memory and runs at 2.0GHZ.

The domain Ω for the two test problems we solved was chosen as the unit cube (0, 1)3. We tested two problems with both constant and variable coefficients. We chose Problem 1 with variable coefficients, so we could not use the plane relaxation with inner multigrid 2D solver. We verified that it was sufficient to use the standard point Gauss-Seidel relaxation smoother to solve the 3D convection diffusion equation efficiently with relatively small Reynolds number and its efficiency was degraded when the Reynolds number increased. For Problem 2 with constant coefficients, we tested the plane Gauss-Seidel relaxation smoother with some large Reynolds number and compared the results with the point relaxation smoother.

We used standard V(1,1) cycle in the multiscale multigrid method. The initial guess for the V-Cycle on the 4h grid was the zero vector. The stopping criteria for the operator based interpolation and the V-Cycle on 2h and h grids were 10−10. The errors reported were the maximum absolute errors over the discrete grid of the finest level. For the SOC method, the number of iterations contains three parts. They are the number of V-Cycles for Ω2h, the number of V-Cycles for Ωh, and the number of iterations for the iterative interpolation combined with the Richardson extrapolation.

4.1 Test Problem 1

The first test problem is

This problem has variable coefficients and the constant Re represents the magnitude of the convection coefficients and simulates the Reynolds number in a flow simulation. The Dirichlet boundary conditions and the forcing term f are set to satisfy the exact solution.

We tested the first problem using point relaxation smoother for small to relatively large values of the Reynolds number (Re ≤ 105). The numerical results are listed from Table 1 to Table 3.

Table 1.

Maximum errors, CPU seconds and the number of iterations of the FOC and SOC schemes for Problem 1 with Re = 0.

| FOC Point | SOC Point | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| h | # iter | CPU | error | order | # iter | CPU | error | order |

| 1/8 | 11 | 0.004 | 2.04e-3 | 4.2 | (8,11),33 | 0.005 | 1.55e-3 | 5.0 |

| 1/16 | 12 | 0.031 | 1.09e-4 | 4.1 | (11,12),42 | 0.051 | 4.90e-5 | 5.4 |

| 1/32 | 12 | 0.281 | 6.29e-6 | 4.0 | (12,12),44 | 0.617 | 1.15e-6 | 5.8 |

| 1/64 | 12 | 2.412 | 3.76e-7 | 4.0 | (12,11),43 | 6.234 | 2.14e-8 | 5.8 |

Table 3.

Maximum errors, CPU seconds and the number of iterations of the FOC and SOC schemes for Problem 1 with Re = 105.

| FOC Point | SOC Point | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| h | # iter | CPU | error | order | # iter | CPU | error | order |

| 1/8 | 51 | 0.009 | 8.40e-2 | 2.0 | (18,53),67 | 0.014 | 7.24e-2 | 2.7 |

| 1/16 | 158 | 0.262 | 1.97e-2 | 2.1 | (53,149),139 | 0.232 | 1.18e-2 | 2.9 |

| 1/32 | 521 | 7.847 | 4.77e-3 | 2.0 | (150,505),276 | 7.463 | 1.57e-3 | 3.0 |

| 1/64 | not converge | – | – | – | not converge | – | – | – |

Table 1 contains the numerical results for Problem 1 when Re = 0, which reduces it to the 3D Poisson equation. Hereinafter, in all tables, the column titles #iter refers to the number of iterations; CPU refers to the CPU cost in seconds; error refers to the maximum absolute error; order refers to the order of accuracy for the computed solution.

We noted that, with the point relaxation smoother, both the SOC scheme and the FOC scheme solved the Problem 1 with optimal grid independent convergence rate. The order of the computed solution from the SOC scheme was close to 6 as we expected and was higher than that from the FOC scheme. In terms of computational cost with the same mesh size h, the FOC scheme was faster because it only ran a standard multigrid V-Cycle and the SOC scheme needed to run the multiscale multigrid method and the operator based interpolation scheme. For the computed solution accuracy, the SOC scheme was more accurate than the FOC scheme for every meshsize we tested, this can be seen from Table 1.

When we chose Re = 10, it was clear from Table 2 that our SOC scheme still yielded a sixth order solution accuracy for small Reynolds number though there was a slight increase in the number of iterations as Re was increased and our multiscale multigrid method still kept the grid independent convergence rate. Similar behavior was observed for the FOC scheme.

Table 2.

Maximum errors, CPU seconds and the number of iterations of the FOC and SOC schemes for Problem 1 with Re = 10.

| FOC Point | SOC Point | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| h | # iter | CPU | error | order | # iter | CPU | error | order |

| 1/8 | 12 | 0.004 | 2.55e-3 | 4.0 | (9,12),35 | 0.006 | 1.95e-3 | 5.0 |

| 1/16 | 13 | 0.032 | 1.41e-4 | 4.1 | (12,13),46 | 0.056 | 6.13e-5 | 5.5 |

| 1/32 | 13 | 0.291 | 8.18e-6 | 4.1 | (13,12),47 | 0.637 | 1.40e-6 | 5.8 |

| 1/64 | 12 | 2.397 | 4.90e-7 | 4.1 | (12,12),44 | 6.531 | 2.56e-8 | 5.7 |

The numerical results in Table 1 and Table 2 indicate that using point relaxation smoother was sufficient to solve the 3D convection diffusion equation with relatively small Reynolds numbers. However, the data in Table 3 shows that when the magnitude of the Reynolds number was large enough (Re = 105), the iterative convergence and the computed accuracy were severely degraded. The solution methods for both the FOC and the SOC schemes did not obtain the grid independent convergence. They took hundreds of multigrid cycles to converge when h ≤ 1/32 and did not converge within the maximum number of iterations (1000) we set when h = 1/64.

4.2 Test Problem 2

For test problem 2, we chose the constant coefficients with large Reynolds number as

We used both the point and the plane relaxation smoothers in the multiscale multigrid method to solve this problem.

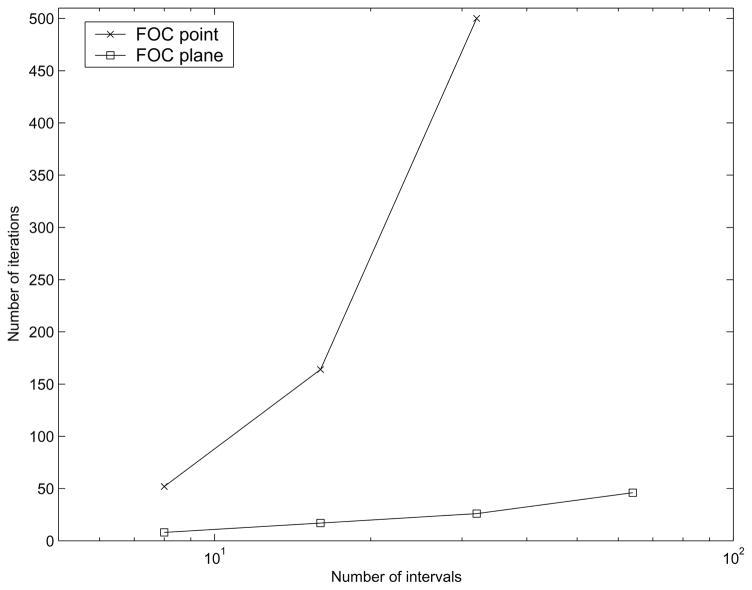

We tested this problem with a very large Reynolds number (Re = 107) and the reported numerical results were listed in Table 4. We noted that the accuracy of the solutions computed by the multigrid method using plane relaxation smoother and point relaxation smoother was comparable. For the CPU cost with the same meshsize, the point relaxation method was faster than the plane relaxation method when h ≤ 1/16, that was because the plane relaxation needed to run a large number of 2D V-Cycles. When the mesh became finer, the number of iterations of the point relaxation method increased very quickly and it did not converge when h = 1/64. On the other hand, the number of iterations of the plane relaxation method was almost stable with respect to the meshsize. For better understanding, we listed the graphic comparison of the number of iterations for different relaxation smoothers in Fig. 6. It was clear that the multigrid method using the plane relaxation smoother took much less iterations than that from point relaxation smoother and the grid independent convergence was kept when the mesh became finer.

Table 4.

Maximum errors, CPU seconds and the number of iterations of Problem 2 using plane relaxation and point relaxation smoothers with Re = 107.

| Point relaxation | Plane relaxation | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| h | strategy | # iter | CPU | error | order | # iter | CPU | error | order |

| 1/8 | FOC | 52 | 0.009 | 6.10e-2 | 2.1 | 8 | 0.017 | 6.10e-2 | 2.1 |

| SOC | (16,51),55 | 0.010 | 5.18e-2 | 2.7 | (4,8),55 | 0.019 | 5.18e-2 | 2.7 | |

| 1/16 | FOC | 164 | 0.262 | 1.41e-2 | 2.1 | 17 | 0.320 | 1.41e-2 | 2.1 |

| SOC | (51,164),74 | 0.294 | 7.96e-3 | 3.0 | (10,16),74 | 0.389 | 7.96e-3 | 3.0 | |

| 1/32 | FOC | 500 | 7.621 | 3.36e-3 | 2.0 | 26 | 4.852 | 3.36e-3 | 2.0 |

| SOC | (164,472),79 | 7.808 | 1.01e-3 | 3.3 | (16,26),79 | 3.247 | 1.01e-3 | 3.3 | |

| 1/64 | FOC | not converge | – | – | – | 46 | 70.073 | 8.21e-4 | 2.0 |

| SOC | not converge | – | – | – | (26,45),81 | 80.787 | 1.06e-4 | 3.2 | |

Figure 6.

Comparison of the number of iterations of the FOC scheme for solving Problem 2 using plane relaxation and point relaxation(Re = 107). Each symbol corresponds to an increasing fine grid: 8, 16, 32, and 64 intervals.

Table 5 contains the test results with various Re and fixed meshsize h = 1/32. Computations were reported for the FOC and the SOC schemes using the plane relaxation smoother. We note that the magnitude of the Reynolds number (Re) affected the convergence and the computed solution accuracy of both schemes inversely. The SOC scheme yielded better solution accuracy than the FOC scheme with every Re value we tested. When Re > 104, there was only a little change for the solution accuracy and the number of iterations for both the FOC and the SOC schemes. We believed that the convergence rate and the number of iterations approached some limits and did not deteriorate any more when Re was beyond certain large values.

Table 5.

Maximum errors, CPU seconds and the number of iterations of Problem 2 using plane smoother with different Re.

| FOC plane relaxation | SOC plane relaxation | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Re(h = 1/32) | # iter | CPU | error | # iter | CPU | error |

| 0 | 6 | 1.062 | 6.29e-6 | (6,6),45 | 1.482 | 1.15e-6 |

| 1 | 7 | 1.234 | 3.48e-5 | (6,6),45 | 1.693 | 1.24e-6 |

| 102 | 12 | 2.109 | 4.84e-4 | (10,12),48 | 2.925 | 2.87e-4 |

| 104 | 28 | 4.854 | 3.36e-3 | (16,26),79 | 5.337 | 1.01e-3 |

| 105 | 26 | 4.518 | 3.36e-3 | (16,26),79 | 5.349 | 1.01e-3 |

| 106 | 26 | 4.489 | 3.36e-3 | (16,26),79 | 5.335 | 1.01e-3 |

| 107 | 26 | 4.455 | 3.36e-3 | (16,26),79 | 5.367 | 1.01e-3 |

| 1010 | 26 | 4.492 | 3.36e-3 | (16,26),79 | 5.402 | 1.01e-3 |

5 Concluding Remarks

We extended the sixth order compact finite difference scheme for solving the 2D convection diffusion equations [32] to 3D problems. Our numerical results indicated that the SOC scheme is more cost-effective than the FOC scheme to produce solution with comparable accuracy and the order of solution accuracy from the SOC scheme is higher than that from the FOC scheme.

It is worthy pointing out that our solution method can be applied to solve the gerenal 3D convection diffusion equations with Dirichlet boundary conditions, but there are still a lot of work need to be done to develop a useful method that can be applied to real-world problems. For example, if a problem involves a derivative boundary conditions such as Neumann boundary conditions, one-sided finite difference approximation for the derivative can be used [20]. For the PDEs with nonsmooth coefficients problems, the multigrid method converges slowly when the coefficients exhibit large jumps in discontinuity [2, 5, 8] or large oscillations [10, 27], and the benefits of employing high order compact schemes and Richardson extrapolation are most or completely lost. Special techniques like semicoarsening, algebraic multigrid method, and frequency decomposition [9, 14], can be used to solve these types of PDEs. For the PDEs with irregular domains, finite element methods may be more suitable to handle these cases. Special finite difference discretization method can also be used, like Sun’s fourth order scheme on face centered cubic grids [26]. We are also concerned with some problems in the field of computational fluid dynamics exhibiting local solution behaviors that require higher level resolution in one area of the domain than in others. Higher level resolution may be computed by using local mesh refinement techniques [28, 40].

Acknowledgments

This author’s research work was supported in part by NSF under grants CCF-0727600, in part by the Kentucky Science and Engineering Foundation under grant KSEF-148-502-06-186, and in part by NIH under grant 1 R01 HL086644-01.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Contributor Information

Yin Wang, Email: ywangf@csr.uky.edu.

Jun Zhang, Email: jzhang@cs.uky.edu.

References

- 1.Adam Y. Highly accurate compact implicit methods and boundary conditions. J Comput Phys. 1977;24(1):10–22. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alcouffe RE, Brandt A, Dendy JE, Jr, Painter JW. The multi-grid method for the diffusion equations with strongly discontinuous coefficients. SIAM J Sci Statist Comput. 1981;2(4):430–454. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ananthakrishnaiah U, Monahar R, Stephenson JW. Fourth-order finite difference methods for three-dimensional general linear elliptic problems with variable coefficients. Numer Methods Partial Differential Equations. 1987;3:229–240. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Axelsson O. Iterative Solution Methods. Cambridge Univ. Press; Cambridge: 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brandt A. Multi-level adaptive solutions to boundary-value problems. Math Comput. 1977;31(138):333–390. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brezinski C, Zaglia MR. Theory and Practice. North-Holland, Berlin: 1991. Extrapolation Method. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Briggs WL, Henson VE, McCormick SF. A Multigrid Tutorial. 2. SIAM; Philadelphia, PA: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dendy JE., Jr Black box multigrid for nonsymmetric problems. Appl Math Comput. 1983;13:261–283. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dendy JE, Jr, Tazartes CC. Grandchild of the frequency decomposition multi-grid method. SIAM J Sci Comput. 1994;16(2):307–319. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Engquist B, Luo E. Convergence of a multigrid method for elliptic equations with highly oscillatory coefficients. SIAM J Numer Anal. 1997;34:2254–2273. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta MM, Zhang J. High accuracy multigrid solutions of the 3D convection-diffusion equation. Appl Math Comput. 2000;113(2–3):249–274. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gupta MM, Kouatchou J. Symbolic derivation of finite difference approximations for the three dimensional Poisson equation. Numer Methods Partial Differential Equations. 1998;18(5):593–606. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gupta MM, Kouatchou J, Zhang J. Comparison of second and fourth order discretization for multigrid Poisson solver. J Comput Phys. 1997;132:226–232. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hackbusch W, Sauter S. The frequency decomposition multigrid method, Part I: application to anisotropic equations. Numer Math. 1989;56:229–245. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kwon Y, Manohar R, Stephenson JW. A single cell finite difference approximations for Poisson’s equation in three variables. Appl Math Notes. 1982;2:13–20. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Llorente IM, Melson ND. Behavior of plane relaxation methods as multigrid smoothers. Electron T Numer Ana. 2000;10:92–114. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Llorente IM, Prieto M, Diskin B. A parallel multigrid solver for 3D convection and convection-diffusion problems. Parallel Comput. 2001;27(13):1715–1741. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oosterlee CW. A GMRES-based plane smoother in multigrid to solver 3-D anisotropic fluid flow problems. J Comput Phys. 1997;130:41–53. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pakantar SV. Numerical Heat Transfer and Fluid Flow. McGraw-Hill; New York: 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rahul K, Bhattacharyya SN. One-sided finite-difference approximations suitable for use with Richardson extrapolation. J Comput Phys. 2006;219:13–20. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Richardson LF. The approximate arithmetical solution by finite differences of physical problems including differential equations, with an application to the stresses in a masonry dam. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London, Series A. 1910;210:307–357. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Saad Y. Iterative Methods for Sparse Linear Systems. 2. SIAM; Philadelphia, PA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schaffer S. High order multigrid method. Math Comput. 1984;43(167):89–115. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Shih TM. Numerical Heat Transfer. Hemisphere; Washington, DC: 1984. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Spotz WF, Carey GF. A high-order compact formulation for the 3D Poisson equation. Number Methods Partial Difference Equations. 1996;12:235–243. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sun H, Kang N, Zhang J, Carlson ES. A fourth-order compact difference scheme on face centered cubic grids with multigrid method for solving 2D convection diffusion equation. Poisson equation. Comput Meth Appl Mech Eng. 2002;191:4661–4674. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ta’asan S. PhD Thesis. Weizmann Institute of Science; Rehovat, Israel: 1984. Multigrid methods for highly oscillatory problems. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Teigland R, Eliassen IK. A multiblock/multilevel mesh refinement procedure for CFD computations. Int J Number Meth Fluids. 2001;36(5):519–538. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thole C, Trottenberg U. Basic smoothing procedures for the multigrid treatment of elliptic 3D operators. Appl Math Comput. 1986;19:333–345. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tzanos CP. Higher-order difference method with a multigrid approach for the solution of the incompressible flow equations at high Reynolds numbers. Numer Heat Transfer: Part B. 1992;22:179–198. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang Y, Zhang J. Sixth order compact scheme combined with multigrid method and extrapolation technique for 2D Poisson equation. J Comput Phys. 2009;228:137–146. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wang Y, Zhang J. Technical Report CMIDA-HiPSCCS 015-09. Department of Computer Science, University of Kentucky; Lexington, KY: 2009. Integrated Fast and High Accuracy Computation of Convection Diffusion Equations Using Multiscale Multigrid Method. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wesseling P. An Introduction to Multigrid Methods. Wiley; Chichester, England: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang J. Accelerated multigrid high accuracy solution of the convection-diffusion equation with high Reynolds number. Numer Methods Partial Differential Eq. 1997;13:77–92. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zhang J. PhD thesis. The George Washington University; Washington, DC: 1997. Multigrid Acceleration Techniques and Applications to the Numerical Solution of Partial Differential Equations. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Zhang J. Residual scaling techniques in multigrid, I: equivalence proof. Appl Math Comp. 1997;86:283–303. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang J. An explicit fourth-order compact finite difference scheme for three dimensional convection-diffusion equation. Commun Numer Methods Engrg. 1998;14:209–218. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhang J. Preconditioned iterative methods and finite difference schemes for convection-diffusion. Appl Math Comput. 2000;109:11–30. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Zhang J. A note on accelerated high accuracy multigrid solution of convection-diffusion equation with high Reynolds number. Numer Methods Partial Differential Eq. 2000;16(1):1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zhang J, Sun H, Zhao JJ. High order compact scheme with multigrid local mesh refinement procedure for convection diffusion problems. Math Comput Simult. 2003;63(6):651–661. [Google Scholar]