Abstract

Complex I pumps protons across the membrane by using downhill redox energy. Here, to investigate the proton pumping mechanism by complex I, we focused on the largest transmembrane subunit NuoL (Escherichia coli ND5 homolog). NuoL/ND5 is believed to have H+ translocation site(s), because of a high sequence similarity to multi-subunit Na+/H+ antiporters. We mutated thirteen highly conserved residues between NuoL/ND5 and MrpA of Na+/H+ antiporters in the chromosomal nuoL gene. The dNADH oxidase activities in mutant membranes were mostly at the control level or modestly reduced, except mutants of Glu-144, Lys-229, and Lys-399. In contrast, the peripheral dNADH-K3Fe(CN)6 reductase activities basically remained unchanged in all the NuoL mutants, suggesting that the peripheral arm of complex I was not affected by point mutations in NuoL. The proton pumping efficiency (the ratio of H+/e−), however, was decreased in most NuoL mutants by 30–50%, while the IC50 values for asimicin (a potent complex I inhibitor) remained unchanged. This suggests that the H+/e− stoichiometry has changed from 4H+/2e− to 3H+ or 2H+/2e− without affecting the direct coupling site. Furthermore, 50 μm of 5-(N-ethyl-N-isopropyl)-amiloride (EIPA), a specific inhibitor for Na+/H+ antiporters, caused a 38 ± 5% decrease in the initial H+ pump activity in the wild type, while no change was observed in D178N, D303A, and D400A mutants where the H+ pumping efficiency had already been significantly decreased. The electron transfer activities were basically unaffected by EIPA in both control and mutants. Taken together, our data strongly indicate that the NuoL subunit is involved in the indirect coupling mechanism.

Keywords: Electron Transfer, Membrane Energetics, Membrane Proteins, Mitochondria, NADH, Proton Pumps, E. coli, Antiporters, Complex I

Introduction

NADH-ubiquinone oxidoreductase (complex I: EC 1.6.99.3) is the entry enzyme of the respiratory chain in mitochondria and bacteria. It conserves the energy from the electron transfer between NADH and ubiquinone (UQ),4 as a proton motive force across the inner membrane (1–3). Mitochondrial complex I is recognized as one of the most elaborate membrane-bound iron-sulfur proteins with a total mass close to 1,000 kDa, and it is composed of 45 different protein subunits (4), seven of which are encoded by mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) and all others by nuclear DNA (5, 6). Electron microscopic analyses indicated that complex I has an overall L-shaped structure of a hydrophilic promontary arm and an hydrophobic membrane arm. The peripheral arm contains all the redox prosthetic groups, one FMN and 8–9 iron-sulfur clusters (7, 8), while the membrane arm contains seven core subunits, ND1–6 and 4L encoded by mtDNA (5, 6), and contains at least one bound UQ (9). After the x-ray crystal structure of the peripheral part of Thermus thermophilus complex I was determined at 3.3 Å (10), the mechanisms of NADH oxidation and intramolecular electron transfer in the peripheral part have been considerably understood (11, 12). The proton pumping mechanism in complex I, however, remains largely unknown. The membrane subunits play roles in proton translocation (13–16) and quinone (Q)/inhibitor binding (17–20), and their alteration is linked to many human diseases (21).

Complex I has been known to have the highest proton pumping efficiency, a stoichiometry of 4H+/2e− (22, 23). In principle, two different coupling mechanism of electron transfer and H+ pump in complex I are now being discussed: direct (redox-driven) and indirect (conformation-driven) mechanisms. In the direct coupling mechanism, quinone-binding site(s) and proton-translocation machinery need to be located close to the peripheral arm with its redox centers to allow direct interaction. The x-ray crystallographic structure (10), photoaffinity labeling/cross-linking studies (24, 25), extensive mutagenesis studies of subunits 49 kDa and PSST in Y. lipolytica complex I (26, 27) and the NuoH subunit (a ND1 homologue in Escherichia coli complex I) (28) support that the primary Q-binding site is in the pocket surrounded by the 49 kDa, PSST, and ND1 subunits, and that H+ translocation is directly coupled to electron transfer from cluster N2 in PSST to UQ in membrane close to the interface region. In the indirect coupling mechanism, energy transduction takes place through long-range conformational changes, thus the electron transfer module can be away from the H+-pumping module. Disruption experiments of purified bovine complex I into subcomplexes (Iα, Iβ, Iγ, and Iλ) by detergent (29) and recent electron microscopy/single particle analyses (30, 31) have supported the distal locations for subunits ND4 and ND5. Both ND4 and ND5 subunits are believed to have H+ translocation sites based on a high sequence similarity to multi-subunit K+ or Na+/H+ antiporters (32). Thus, for subunits ND4 and ND5, an indirect coupling mechanism is favored. However, there were no experimental data to support the indirect coupling mechanism in complex I.

We previously reported that the ND5 subunit of bovine heart complex I was labeled exclusively with a novel photoaffinity analog of the potent complex I inhibitors, fenpyroximate (18) and more recently with an asimicin analog (20). The labeling was correlated with the inhibition of the enzyme activity. The labeling with a photoaffinity analog of fenpyroximate was completely prevented by the preincubation of various complex I inhibitors including not only common inhibitors such as rotenone and piericidin A, but also 5-(N-ethyl-N-isopropyl)-amiloride (EIPA), a specific inhibitor for Na+/H+ exchangers. This suggested that the ND5 subunit plays a role for linking between UQ-binding and H+ translocation. Therefore, in this study, we focused on the largest hydrophobic NuoL subunit (E. coli ND5 homolog) and investigated functional and structural roles of conserved amino acid residues between the NuoL/ND5 subunit of complex I and the Mrp (multiple resistance and pH adaptation) subunit A/Mnh (multisubunit Na+/H+ antiporter) subunit A of multi-subunit K+ or Na+/H+ antiporters.

Bacterial complex I provide attractive systems for studies on the role of specific residues in the central subunits because of its structural simplicity and ease of gene manipulation. E. coli complex I consists of only 13 subunits (NuoC and NuoD are fused), encoded by nuo operon (nuoA-N), but all 13 subunits are homologous to their mitochondrial counterparts (14 core subunits), and share the main structural and enzymatic properties (33). This strategy has been very successful for characterizing membrane subunits mostly done by Vik's group (34) and Yagi's group (13–16, 28, 35). In this study, we constructed 27 mutants of highly conserved residues in NuoL by chromosomal DNA manipulation and examined characteristics of these mutants. Our data strongly indicated that NuoL/ND5 is involved in the indirect coupling of the H+-pumping mechanism.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Materials

The pCRScript cloning kit, QuikChange® II XL site-directed mutagenesis kit and Herculase®-enhanced DNA polymerase were obtained from Stratagene (Cedar Creek, TX). Materials for PCR product purification, gel extraction, and plasmid preparation were from Qiagen (Valencia, CA). The gene replacement vector, pKO3, was a generous gift from Dr. George M. Church (Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA). Asimicin was synthesized according to Ref. 36 by Subhash C. Sinha's group. The BCA protein assay kit and SuperSignal West Pico chemiluminescent substrate were from Pierce. All chemicals used were reagent grade.

Preparation of nuoL Knock-out and Mutant Cells

The E. coli MC4100 strain was used to generate knock-out and site-specific mutations of nuoL employing the pKO3 system with the modification described previously by Kao et al. (14). Oligonucleotides used in this study are listed in supplemental Table S1. A DNA fragment, which includes the nuoL gene with its upstream and downstream 1-kb DNA segments, was amplified from E. coli DH5α by PCR. E. coli nuoL knock-out (NuoL-KO mutant) was constructed by replacement of the nuoL gene in the nuo operon encoding E. coli complex I with the nuoL fragment disrupted spc (spectinomycin) gene with pKO3/nuoL(spc). In subsequent steps the pKO3/nuoL-mutant plasmids were used for construction of site-directed nuoL mutants. The correct introduction of point mutations in the chromosome was verified by direct DNA sequencing.

Bacterial Growth and Membrane Vesicles Preparation

The E. coli membranes were prepared according to (14). In brief, the cells were grown in 250 ml of Terrific Broth medium until A600 of 2 and were then harvested at 5,800 × g for 10 min. The cells were resuspended at 10% (w/v) in a buffer containing 10 mm MOPS (pH 7.0), 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm DTT, 1 mm PMSF, and 10% (w/v) glycerol. Lysozyme was added to the cell suspension at a final concentration of 0.1 mg/ml and incubated on ice for 30 min. Then, the cell suspensions were sonicated twice for 15 s, and passed twice in a French press at 25,000 p.s.i. and centrifuged at 23,400 × g for 10 min. The supernatant was ultracentrifuged at 256,600 × g for 45 min. The pellet was resuspended in the same buffer as described above. The resulting membrane suspension was either used immediately for enzyme assays or, frozen in liquid nitrogen and stored in small aliquots at −80 °C until use.

Gel Electrophoresis and Western Blot Analysis

20 μg of protein from each membrane suspension was subjected to SDS-PAGE using the discontinuous system of Laemmli (37). The expression of the E. coli complex I subunits was immunochemically determined by using antibodies specific to NuoB and NuoL. The assembly of E. coli complex I was evaluated by using Blue-Native (BN) PAGE according to ref (38, 39). In brief, E. coli membranes equivalent to 800 μg of protein were resuspended in 160 μl of 750 mm aminocaproic acid, 50 mm BisTris-HCl (pH 7.0), 0.1 mg/ml DNase, and 1% (w/v) dodecyl-β-maltoside. After the incubation and centrifugation, 10 μl of the samples were loaded on a 5.5% separating gel with a 4% stacking gel, and the electrophoresis was performed in the cold room. When the electrophoresis was finished the gel was washed two times in 2 mm Tris-HCl (pH 7.5) and subjected to NADH-p-nitroblue tetrazolium (NBT) dehydrogenase activity staining (13) and/or immunoblotting analysis, using the anti-NuoB antibody.

Activity Analyses

The dNADH oxidase assays were performed spectrophotometrically at 37 °C using a Shimadzu UV1800 spectrophotometer with 50 μg/ml of membrane samples in 10 mm potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.0) containing 1 mm EDTA. The reaction was started by the addition of 0.15 mm dNADH, and the measurements were followed at a wavelength of 340 nm as described previously (14). The dNADH-K3Fe(CN)6 reductase activities were performed in the same conditions, except that the reaction buffer contained 10 mm KCN and 1 mm K3Fe(CN)6 at 420 nm. ϵ340 = 6.22 mm−1 cm−1 for dNADH and ϵ420 = 1.00 mm−1 cm−1 for K3Fe(CN)6 were used for analyses. Proton pump activity was measured at 30 °C by acridine orange (AO, λex = 493 nm, λem = 530 nm) fluorescence quenching in 50 mm MOPS (pH 7.0), 10 mm MgCl2, 50 mm KCl, and 5 μm AO as described previously (40). The reaction was initiated by adding 0.2 mm dNADH. When necessary, 1 μm of the proton ionophore FCCP was added as an uncoupler. Also to try to observe proton-pumping activity of complex I alone, we measure the activity in the presence of exogenous quinone, decylubiquinone (DQ) as an electron acceptor and 5 mm KCN, which inhibits the bo3 oxidase that exists in the downstream of the E. coli respiratory chain.

Antibody Production

On the basis of facility of peptide syntheses and antigenicity, we selected three regions (His-357 to Ser-371, Ser-398 to His-411, and Gly-439 to Ser-454) to raise antibodies specific to E. coli NuoM. Three oligopeptides, HHEQNIFKMGGLRKSC (EcoNuoL-1), CSKDEILAGAMANGH (EcoNuoL-2), and CGKEQIHAHAVKGVTHS (EcoNuoL-3) were synthesized and conjugated to the maleimide-activated bovine serum albumin according to the manufacturer's protocol. The anti-EcoNuoL-1, anti-EcoNuoL-2, and anti-EcoNuoL-3 antibodies were affinity-purified by using the EcoNuoL-1, EcoNuoL-2 and EcoNuoL-3 peptides linked to the Sulfo-Link Coupling Gel (Pierce) according to the manufacturer's protocol. By using the wild-type and NuoL-KO mutant membranes, we found that the anti-EcoNuoL-1 antibody successfully recognize the NuoL subunit.

Statistical Analyses

All measurements will be presented as mean ± S.D. (n = 3–6). CI Activity data were analyzed by Student's t test. The level of significance, indicating group differences, was p < 0.01. All calculations was performed using programs of the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS for Windows 6.1.2; SPSS, Chicago, IL).

Other Analytical Procedures

Protein concentrations were determined by the BCA protein assay kit (Pierce) using bovine serum albumin as the standard. Any variations from the procedures and other details are described in the figure legends.

RESULTS

Sequence Analysis of the NuoL Subunit and Generation of Site-specific Mutations

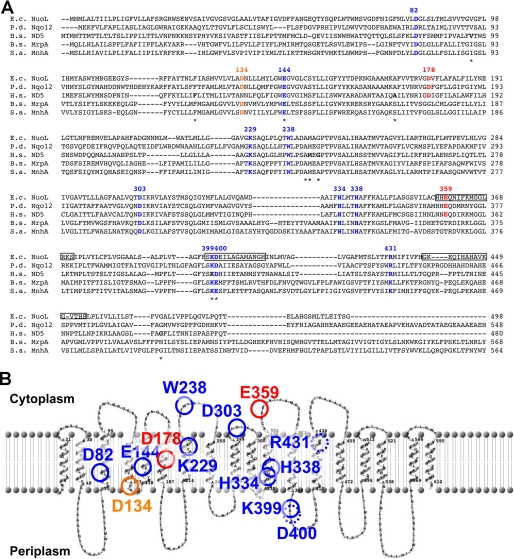

Sequence comparisons previously suggested that subunits ND2, ND4, and ND5 have evolved from a common ancestor related to K+ or Na+/H+ antiporters thus, they are believed to be a proton translocation module (32, 41). In fact, the various amiloride derivatives that specifically inhibit K+ or Na+/H+ antiportors, can also inhibit the complex I activities (42). We performed sequence alignment among NuoL/ND5 and, MrpA/MnhA of multisubunit secondary Na+/H+ antiporters (Fig. 1A). MrpA has been shown to have a role in Na+ resistance and Na+-dependent pH homeostasis in Bacillus subtilis (43), wheras MnhA from Staphylococcus aureus conferred Na+ resistance when expressed in E. coli. We mutated highly conserved 13 residues, Asp-82, Asp-134, Glu-144, Glu-178, Lys-229, Trp-238, Asp-303, His-334, His-338, Glu-359, Lys-399, Asp-400, and Arg-431 (E. coli numbering). Asp-178 and Glu-359 are found to be highly conserved only in complex I (Fig. 1A). Because a topology prediction of the E. coli NuoL subunit was varied depends on a composite of computer programs such as TopPredII, PHDhtm, TMHMM, SOSUI, Tmpred, and HMMTOP, putative locations of the mutated amino acids by using TMHMM and TopPred software were shown in Fig. 1B as an example. We constructed 27 site-directed NuoL point mutants by chromosomal homologous recombination. All mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing.

FIGURE 1.

A, multiple sequence alignments of the NuoL subunit (total 613 AA) of E. coli complex I and the MrpA subunit of multisubunit cation antiporter complexes, and their homologues from various organisms. The highlighted amino acids and their numbers (according to the E. coli sequences) were mutated in this study. Blue residues are almost perfectly conserved acidic residues in both NuoL/ND5 and MrpA/MnhA. The orange residue is conserved in NuoL from bacteria and plant, and MrpA/MnhA. Red residues are perfectly conserved in only NuoL/ND5. Gray boxes indicate the oligopeptides synthesized to raise E. coli NuoL specific antibodies. The disease-related mutations found in human complex I are marked by stars. E.c., E. coli (the GenBankTM Accession Number is AAC75343); P.d., Paracoccus denitrificans (AAA25587); H.s., Homo sapiens (P03915); B.s., B. subtilis (Q9K2S2); S.a., Staphylococcus aureus (BAA35095). B, transmembrane topology model of the E. coli NuoL subunit predicted by TMHMM and putative locations of the mutated amino acids in this study.

Subunit Assembly of E. coli Complex I in NuoL Mutant Strains

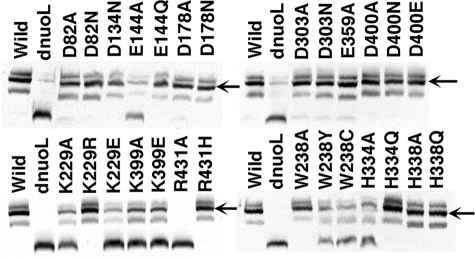

To investigate whether mutation in NuoL affects the subunit assembly of complex I, we analyzed mutant membranes on a BN-PAGE gel by immunoblotting using anti-NuoB subunit-specific antibody (Fig. 2) and NADH-NBT dehydrogenase activity staining (supplemental Fig. S1). As expected, in the NuoL-KO mutant (dnuoL) a fully assembled complex I was not detected. However, the partially assembled subcomplex appeared with a lower molecular weight, which was not stained by NADH-NBT dehydrogenase activity (supplemental Fig. S1). In fact, all peripheral subunits (NuoB, NuoCD, NuoE, NuoF, NuoG, and NuoI) and a membrane subunit NuoA existed in the membranes from the NuoL-KO mutant at similar levels as the wild type, judged by Western blot analyses on SDS gels (data not shown). As expected, there was no band reacted with NuoL specific antibody against EcoNuoL-1 in the NuoL-KO mutant membranes (supplemental Fig. S2). In mutants E144A, K229A, K229E, W238Y, W238C, H334A, K399A, K399E, and R431A, the amount of the assembled complex I was significantly reduced, while a partially assembled subcomplex with the same size as seen in NuoL-KO appeared (Fig. 2). In other mutants, there was no drastic difference in the amount of fully assembled complex I compared with the wild type.

FIGURE 2.

A, Western blot analysis of BN-PAGE gels. E. coli membrane preparations from the wild type, NuoL knock-out (dnuoL), and NuoL mutants. The arrow shows the location of the fully assembled complex I band. BN gels were incubated with 2.5 mg/ml NBT and 150 μm NADH for 1 h at 37 °C. After BN-PAGE, membrane proteins were subsequently electrotransferred to nitrocellulose membranes, and were immunostained with the affinity-purified NuoB antibody.

Effects of NuoL Mutation on Electron Transfer Activities

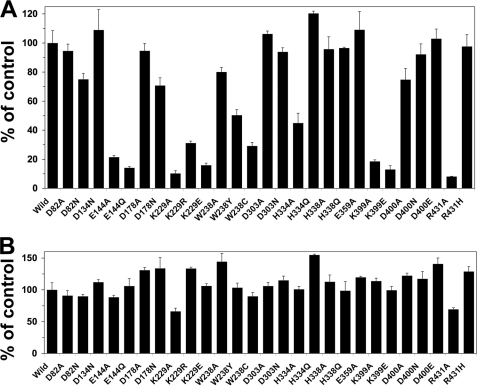

We measured electron transfer activities of complex I by using membrane vesicles prepared from wild type and NuoL mutants (Fig. 3). Because E. coli houses an alternative NADH-Q oxidoreductase (NDH-2) lacking an energy coupling site (44, 45), dNADH was used which serves as the substrate only for complex I (46). The dNADH oxidase activities of the membranes from NuoL mutant strains that contained only fully assembled complex I, mostly retained the control levels or at least 70% of the wild type, except E144Q and K229R, in which dNADH oxidase activities were drastically decreased to 15 and 30% of wild type, respectively. Glu-144 and Lys-229 are both expected in the transmembrane (Fig. 1B), and are perfectly conserved not only in NuoL/ND5 and MrpA/MnhA (Fig. 1A), but also in NuoN/ND2 and NuoM/ND4 (13, 40). The mutation at the equivalent residues Glu-144 and Lys-234 in NuoM were previously shown to cause almost total abolishment of complex I activities (13, 40). It is highly likely that Glu-144 and Lys-229 in NuoL as well as in NuoM are directly involved in proton translocation by complex I (35). We also found that the replacement of Arg-431 with histidine showed full dNADH oxidase activities, while the replacement of Arg-431 with the neutral alanine resulted in almost complete loss of dNADH oxidase activities, which was caused by complete loss of fully assembled complex I (Fig. 2). It suggests that the positive charge at Arg-431 is important for the assembly of the membrane arm of complex I. Interestingly, mutation at His-338 in the triad Q-binding sequence motif (L/A-X3-H-X2/3-L/T/S) (47) did not affect the dNADH oxidase activity. In contrast, the peripheral dNADH-K3Fe(CN)6 reductase activities remained unchanged in all the NuoL mutant membranes including E144Q, K229R, and other mutants that contain only partially assembled complex I, suggesting that point mutations in NuoL do not significantly affect the integrity of peripheral arm itself. This result is in good agreement with the recent data with NuoM by Euro et al. (40) and Torres-Bacete et al. (13) and well supported by the distal location of NuoM and NuoL (30).

FIGURE 3.

dNADH oxidase (A) and dNADH:ferricyanide (B) activities of E. coli complex I in the NuoL mutant membranes. 100% of dNADH oxidase and dNADH:ferricyanide activities were 852 and 1282 nmol/min/mg, respectively. Values are means ± S.D. (n = 3–5).

Effects of NuoL Mutation on Proton Transfer Activities

Because buried carboxyl groups have been proved to be a key factor in proton translocation in many proton translocating proteins including ATP synthase (48), NuoL mutants at conserved glutamate or aspartate residues were chosen for further studies on proton transfer activities.

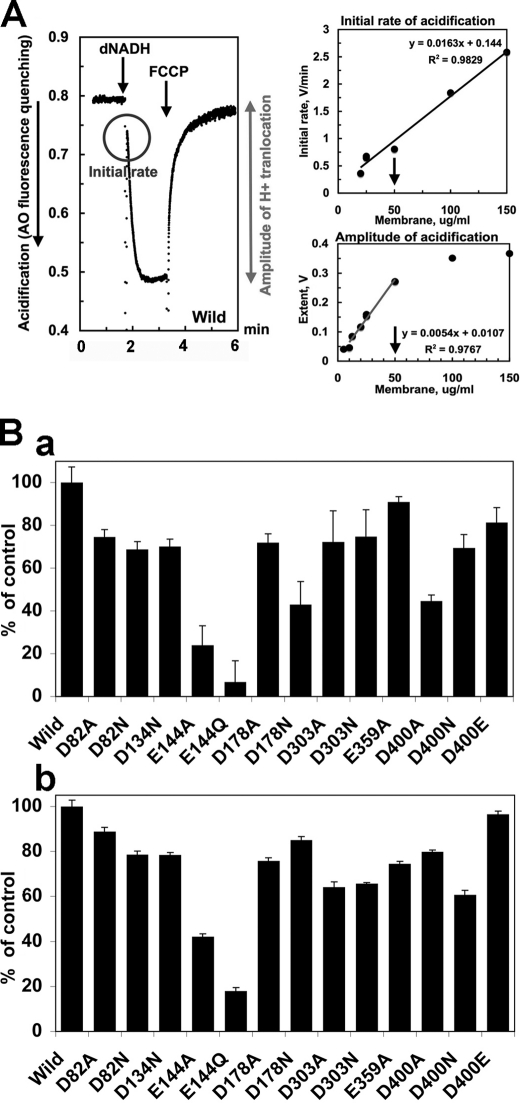

Proton translocation activities of E. coli complex I were measured by using membrane vesicles. As shown in Fig. 4A, by using acridine orange as a delta-pH indicator, the proton gradient is observed by the addition of dNADH, and this H+ gradient is reversed by uncoupler, FCCP. To compare proton pumping activities more quantitatively, we first checked the dose response of the initial acidification rate and the amplitude of acidification with the wild-type membrane vesicles. Then we set the concentration of membranes at 50 μg/ml for further analyses, where both parameters showed linear relations (Fig. 4A). The initial H+-pumping rate was significantly decreased in most NuoL mutants by about 30–50% of the control and severely reduced in Glu-144 mutants (Fig. 4Ba). In contrast, the amplitude of acidification was less affected by mutations (Fig. 4Bb). However, when succinate was used instead of dNADH, there was no significant difference in the initial rate and amplitude of acidification between the wild type and NuoL mutants (data not shown).

FIGURE 4.

A, generation of a pH gradient coupled with dNADH oxidation in E. coli membrane vesicles. Left, the initial rate and amplitude of proton translocation were measured by the quenching of the fluorescence of acridine orange (AO) at 30 °C with an excitation wavelength of 493 nm and an emission wavelength of 530 nm. At the time indicated by arrows, 0.2 mm dNADH, or 2 μm FCCP was added to the assay mixture containing 50 mm MOPS (pH7.0), 10 mm MgCl2, 50 mm KCl, 5 μm AO, and the wild-type E. coli membrane vesicles (50 μg of protein/ml). Right, the dose response of the initial rate and amplitude of acidification was measured. The concentration for membrane vesicles was set at 50 μg/ml for the following experiments to quantitatively compare the proton pumping activities among the mutants. B, initial rate (a) and amplitude (b) of acidification of E. coli complex I in the NuoL mutant membrane vesicles. 100% of the initial rate and amplitude were 0.958 V/min and 0.3 V (arbitral recording units), respectively. Values are means ± S.D. (n = 3–6).

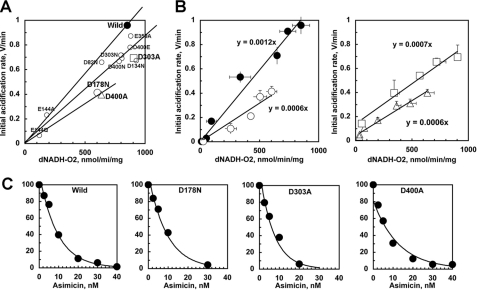

Then we analyzed the H+ pumping efficiency (the H+/e− ratio) in NuoL mutants, to see how tightly the H+ pumping activity is coupled with the redox activity. We re-plotted the initial acidification rate versus NADH oxidase activity as shown in Fig. 5A. The pumping efficiency as measured by the slope was significantly decreased in most NuoL mutants by up to 50% for D178N and D400A, while wild type showed the best efficiency of all. To confirm this point, we modified dNADH oxidase activity by adding the specific complex I inhibitor, asimicin from 2.5 to 40 nM, and the initial rate of acidification was also measured in parallel. As seen in Fig. 5B, the slope remained constant in the full range in wild type and mutants D178N, D303A, and D400A. Although the slope does not indicate the numerical H+/e− ratio, the slope directly reflects the pumping efficiency. Because this figure clearly showed that the slope for D178N and D400A is half compared with the wild type, the H+/e− ratio decreased to 2H+/2e− from 4H+/2e− in wild type. However, the sensitivity to asimicin remained unchanged in these mutants (Fig. 5C). It strongly suggests that the direct coupling site was intact in these mutants. Furthermore, it is also important to address that the value of the concentration of half-maximal inhibition (IC50) = 7.6 nm for asimicin was surprisingly low for E. coli complex I, since it is known that rotenone does not inhibit E. coli complex I at all, and the IC50 value for piericidin A is about 100 nm for E. coli complex I. To our knowledge, this is the first report that asimicin has the one of the best inhibitory potency against E. coli complex I.

FIGURE 5.

A, relationship between the electron transfer activity (dNADH-O2) and the H+ pumping activity (the initial rate of acidification) in the NuoL mutant membrane vesicles. Three lines with 100%, 75%, 50% of the slope for the wild type are shown for comparison. B, dependence of the initial rate of acidification on the dNADH oxidase activity. The data of the wild type (solid circles), D178N (open circles), D303A (open squares), and D400A (open triangle) are shown in A and B as indicated. C, inhibition of dNADH oxidase activity by a potent complex I inhibitor, asimicin in the wild type and D178N, D303A, and D400A membranes. The IC50 value was 7.6, 7.5, 6, and 7 nm in these membranes, respectively.

Effects of EIPA on Proton Transfer Activities

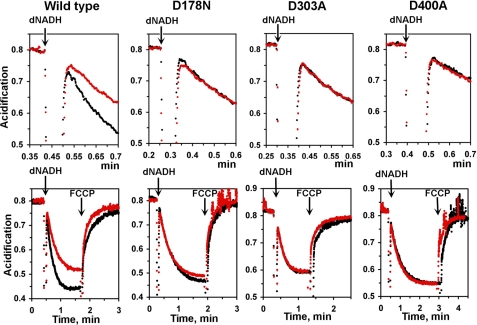

To reinforce the point that only the indirect coupling mechanism was affected in these NuoL mutants, we also studied the effect of EIPA, a specific inhibitor for Na+/H+ exchangers to this experiment, on the H+ pumping activities in NuoL mutants. Because ND5/NuoL exhibits high sequence similarity to a family of the Na+/H+ antiporters (32), and EIPA prevented the ND5 labeling by a fenpyroximate photoaffinity analog (18), it was expected that an EIPA-binding site might be located in NuoL. Thus, we predicted that EIPA might primarily inhibit the H+ transfer in NuoL. In the wild type, the initial rate of H+ pumping activity was significantly decreased to 62% (Fig. 6, upper panel; Table 1), and the amplitude of acidification also became significantly smaller in the presence of 50 μm EIPA (Fig. 6, lower panel). However, EIPA had little effect on the rate and amplitude in the mutants (Fig. 6 and Table 1). In fact, the traces for these mutants were almost exactly the same in the presence or absence of EIPA (Fig. 6, upper panel). Because the effect of EIPA on electron transfer activities was minimal, and only slightly decreased in the wild type as well as in NuoL mutants, D178N, D303A, and D400A (Table 1), the difference in rate and amplitude observed in the wild type can be interpreted as the contribution from the indirect coupling mechanism of complex I. These data strongly indicates that EIPA blocked only the indirect H+ transfer pathway, which exists in the wild type but not in these NuoL mutants where the H+ pumping efficiency have already decreased by ∼50%.

FIGURE 6.

Effect of EIPA on the proton pumping activities in the wild-type (A), D178N (B), D303A (C), and D400A (D) membranes. Black and red dotted lines are in the presence and absence of EIPA 50 μm.

TABLE 1.

Effect of EIPA on the initial rate of H+ transfer and dNADH-O2 activity of E. coli complex I

| Wild type | D178N | D303A | D400A | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EIPA (50 μm) | − | + | − | + | − | + | − | + |

| Initial ratea (V/min) | 0.964 ± 0.085 | 0.603b ± 0.05 | 0.458 ± 0.01 | 0.45 ± 0.09 | 0.665 ± 0.004 | 0.633 ± 0.041 | 0.411 ± 0.017 | 0.407 ± 0.02 |

| dNADH-O2a activity (nmol/min/mg) | 913 ± 24.5 | 863 ± 48.6 | 630 ± 51.8 | 568 ± 26.2 | 942 ± 68.7 | 781 ± 54 | 740 ± 41.4 | 725 ± 50 |

a Results were expressed in means ± S.D. of three to six independent measurements.

b The decrease in the initial rate of H+ transfer of the wild type by EIPA was statistically significant (p < 0.01).

DISCUSSION

It has been postulated that complex I operates an indirect conformation-driven coupling mechanism other than a direct redox-driven coupling mechanism to achieve high 4H+/2e− stoichiometry. To our knowledge, the present study provides the first experimental evidence for the indirect coupling mechanism in complex I. This was achieved by using novel NuoL mutants and two key compounds, asimicin and EIPA.

Asimicin and EIPA

Although there are many potent inhibitors for mitochondrial complex I, they are not very effective inhibitors for bacterial complex I. A common inhibitor rotenone does not inhibit E. coli complex I, while another common inhibitor piericidin A inhibits 90% of E. coli complex I activity at 1 μm and still leaves residual activity even at much higher concentrations (49, 50), where other quinone oxidoreductases such as bo3 oxidase can be inhibited by piericidin A (51). In fact, when we used piericidin A in the same experiment as shown in Fig. 5B, we could not obtain a liner relationship between the initial acidification rate and the electron transfer activity (data not shown). However, with asimicin, we finally succeeded in obtaining a good linear relationship in the full range and crossed the origin of ordinates (Fig. 5B). We also found that asimicin is one of the most potent inhibitors for E. coli complex I with IC50 = 7.6 nm. Asimicin is known as a potent anticancer agent (52), and it constitutes a class of Annonaceous acetogenins, the same chemical family of rolliniastatin, bullatacin, and annonin VI.

EIPA has been known as a specific inhibitor for Na+-related transporters such as Na+/H+ exchangers and Na+/K+ ATPase. We previously reported that EIPA is also an effective inhibitor for mitochondrial complex I with IC50 = 17 μm when SMP was used. But we noticed that EIPA does not efficiently inhibit E. coli complex I (IC50 > 100 μm) (42). With the reconstituted purified E. coli complex I, 500 μm EIPA was needed to completely inhibit NADH:UQ reductase (53). Interestingly, however, there is a report that EIPA inhibited the H+ pumping activity of complex I with IC50 of 27 μm without affecting electron transfer activities, when rat liver mitochondrial fractions were used, that is, respiration initiated by glutamate and malate in this case (54). This suggests that EIPA is primarily a specific H+ pump inhibitor for complex I.

NuoL Is Involved in the Indirect Coupling Mechanism

The H+ pumping efficiency was decreased for most NuoL mutants including D178N, D303A, and D400A by up to 50% relative to the wild type (Fig. 5, A and B). Moreover, in contrast to the wild type, EIPA had no effect on the initial rate amplitude of acidification in these mutants (Fig. 6 and Table 1). It is highly likely that the EIPA-sensitive indirect H+ transfer pathway is impaired in these NuoL mutants.

However, a question immediately arises: how are those conserved aspartate residues involved in the indirect coupling mechanism? In many membrane-bound enzymes involved in proton or cation translocation, it has been well documented that negatively charged residues in transmembrane helices are important for H+ or cation binding and translocation (55). Because the residue Asp-178 is conserved only among the complex I family and located within the putative transmembrane (Fig. 1B), Asp-178 might be involved in the H+ binding. However, according to the topological study of Rhodobacter NuoL (32) and various transmembrane prediction software, Asp-303 and Asp-400 are not located in the putative transmembrane regions but just outside of the transmembrane helices: Asp-303 is on the cytoplasmic side, and Asp-400 are on the periplasmic side. How is it possible that the carboxyl residues outside of the transmembrane helix participate in the H+ translocation? It can be speculated that large conformational changes induced by NADH binding bring these residues into the transmembrane regions and they can be localized at the entry or exit sites of H+-transfer route. There are some examples of ion transporters to support such a large conformational change from the x-ray crystallographic studies. 1) E. coli NhaA, the main Na+/H+ antiporters, has shown the large rearrangement of the transmembrane region elicited by a pH signal perceived at the entry to the cytoplasmic funnel, and this movement permits a rapid alternating-access mechanism in the middle of the membrane at the putative ion-binding site (56). 2) Ca2+-ATPase undergoes large scale up to 50 Å thermal rearrangements involving both transmembrane and cytoplasmic domains upon the Ca2+ binding (57). Especially, the movement of the transmembrane helix M1 is complex: the top part of M1 is largely bent at Asp-59 in a Ca2+-free state and Asp-59 is outside of the membrane, while the M1 helix becomes straight, and Asp-59 is inside the transmembrane in the Ca2+-bound state.

Alternatively, it can be speculated that Asp-303 and/or Asp-400 might be directly or indirectly involved in a UQ-binding domain, which exchanges Q or QH2 with the membrane ubiquinone pool. This speculation can be supported by the following facts. (i) ND5 was predominantly labeled with a quinone analog (a fenpyroximate delivative) in photoaffinity labeling experiments (18). (ii) The region around Asp-400 is highly conserved among various species and has noticeable similarity to one of the secondary structural regions of the Qi site of the bc1 complex (47). (iii) Asp-400 might be located in the transmembrane, because we failed to raise the antibody against EcoNuoL-3 (Fig. 1A) containing the Asp-400 region, indicating that this region is not exposed to the outside of the membranes. It will be interesting to find out the exact roles of Asp-303 and Asp-400 residues for H+ translocation, which are conserved not only in complex I but also in multisubunit Na+/H+ antiporters.

Measurements of Proton Pumping Activities

In this study, we monitored proton pumping activities by adding only the substrate dNADH in the absence of hydrophilic quinones. We carefully analyzed the H+ pumping activity data by considering the contribution from cytochrome bo3 oxidase activity (a main terminal oxidase in the aerobically grown E. coli cells). The reasons why we did the experiments this way are: 1) With our preparations, we failed to observe H+ pumping activity of complex I alone by adding dNADH in the presence of 50 μm DQ (or Q1) and 5 mm KCN, which was the same condition previously published by Euro et al. (40), because of the strong product inhibition of DQH2 (or Q1H2) (58). Thus, our membrane vesicle preparations were seemingly more intact than the spheroplast preparation by Euro et al. (40). 2) Because the specific activity of bo3 oxidase is 30–40 times higher than that of complex I (59), it is reasonable to think that the initial acidification rate started by dNADH directly corresponds to the H+ pumping activity by complex I. 3) Hydrophilic ubiquinones such as UQ1 can be reduced by a non-energy-transducing reaction. This gives a lower H+/e− stoichiometry. In fact, our data on the relationship between the initial rate of acidification versus dNADH oxidase activity were linear in the full range and crossed the origin of ordinates (Fig. 5B), while their data were linear in the range from 30 to 70% and did not cross the origin (40), indicating that dNADH-DQ reductase activity was only partially coupled with the H+ translocation.

Does NuoL Contain an EIPA Binding Site?

It has been hypothesized that the VFF amino acid motif in transmembrane region 4 (TM4) and TM9 are involved in Na+ binding and/or amiloride binding in the ubiquitous Na+/H+ exchanger, NHE1 (60). Recent study by Pedersen et al. (61) showed that TM10–11 also contributes to the amiloride sensitivity in NHE1. Although there is no VFF motif in NuoL, there are two FF motifs (116RFF and 333AFF). Of the two, 333AFF is highly conserved among the NuoL/ND5 subunit and its homologues in various organisms. 333AFF is located immediately downstream of the predicted Q-binding site (L/A-X3-H-X2/3-L/T/S) (47). Based on the topology model of the R. capsulatus NuoL subunit using the alkaline phosphatase fusion protein technique (32), 333AFF is located in the putative TM11. Thus it is likely that 333AFF in NuoL could be an EIPA binding site.

This assumption can well be supported by previous reports: (i) the photoaffinity labeling of the bovine ND5 subunit by the fenpyroximate analog was almost completely blocked by EIPA (18); (ii) reconstituted C-terminally truncated E. coli NuoL subunit (NuoL(N)) facilitated the uptake of Na+ into the proteoliposomes, and this Na+ uptake was inhibited by EIPA (62); (iii) the Na+ uptake by membrane vesicles containing overexpressed Protein A fused NuoL(N) from the yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae endoplasmic reticulum was inhibited by EIPA (63).

However, here is a problem. Although our data clearly showed that NuoL mutants D178N, D303A, and D400A lost the EIPA sensitivity in a similar way, these amino acid residues are not close to the TM11 region. It seems that each point mutation in NuoL affected the overall structure of NuoL, resulting in the perturbation of the EIPA binding site in NuoL. Because no drastic change in the assembly and electron transfer activities were observed in these mutants, the amino acid replacements may cause subtle conformational changes in NuoL that inhibit long-range conformational coupling. Further detailed study is on the way in our laboratory.

Very recently, x-ray crystal structures of whole complex I from T. thermophilus and the membrane domain of E. coli complex I were determined, revealing that NuoL contains an unusually long conserved amphipathic helix that extends ∼110 Å to a position near the UQ-binding site (64). This structural information, together with our current study, supports that NuoL/ND5 is the key player in the indirect conformation-driven coupling mechanism in complex I.

Supplementary Material

This work was supported in part by United States Public Health Service Grants R01GM33712 (to T. Y.) and R01GM030736 (to T. O.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Table S1 and Figs. S1 and S2.

- UQ

- ubiquinone

- BN-PAGE

- blue native gel electrophoresis

- EIPA

- 5-(N-ethyl-N-isopropyl)amiloride

- Q

- quinone

- SMP

- submitochondrial particles

- SQ

- semiquinone.

REFERENCES

- 1.Yagi T., Matsuno-Yagi A. (2003) Biochemistry 42, 2266–2274 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sazanov L. A. (2007) Biochemistry 46, 2275–2288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Brandt U. (2006) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 75, 69–92 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carroll J., Fearnley I. M., Skehel J. M., Shannon R. J., Hirst J., Walker J. E. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 32724–32727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chomyn A., Cleeter M. W., Ragan C. I., Riley M., Doolittle R. F., Attardi G. (1986) Science 234, 614–618 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chomyn A., Mariottini P., Cleeter M. W., Ragan C. I., Matsuno-Yagi A., Hatefi Y., Doolittle R. F., Attardi G. (1985) Nature 314, 592–597 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohnishi T. (1998) Biochim Biophys Acta 1364, 186–206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ohnishi T., Nakamaru-Ogiso E. (2008) Biochim Biophys Acta 1777, 703–710 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shinzawa-Itoh K., Seiyama J., Terada H., Nakatsubo R., Naoki K., Nakashima Y., Yoshikawa S. (2009) Biochemistry 49, 487–492 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Sazanov L. A., Hinchliffe P. (2006) Science 311, 1430–1436 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Verkhovskaya M. L., Belevich N., Euro L., Wikström M., Verkhovsky M. I. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 3763–3767 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moser C. C., Farid T. A., Chobot S. E., Dutton P. L. (2006) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1757, 1096–1109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Torres-Bacete J., Nakamaru-Ogiso E., Matsuno-Yagi A., Yagi T. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 36914–36922 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kao M. C., Di Bernardo S., Perego M., Nakamaru-Ogiso E., Matsuno-Yagi A., Yagi T. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 32360–32366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kao M. C., Nakamaru-Ogiso E., Matsuno-Yagi A., Yagi T. (2005) Biochemistry 44, 9545–9554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kao M. C., Di Bernardo S., Nakamaru-Ogiso E., Miyoshi H., Matsuno-Yagi A., Yagi T. (2005) Biochemistry 44, 3562–3571 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Murai M., Ishihara A., Nishioka T., Yagi T., Miyoshi H. (2007) Biochemistry 46, 6409–6416 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakamaru-Ogiso E., Sakamoto K., Matsuno-Yagi A., Miyoshi H., Yagi T. (2003) Biochemistry 42, 746–754 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yagi T., Hatefi Y. (1988) J. Biol. Chem. 263, 16150–16155 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nakamaru-Ogiso E., Han H., Matsuno-Yagi A., Keinan E., Sinha S. C., Yagi T., Ohnishi T. (2010) FEBS Lett. 584, 883–888 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Mitchell A. L., Elson J. L., Howell N., Taylor R. W., Turnbull D. M. (2006) J Med Genet 43, 175–179 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wikström M. (1984) FEBS Lett. 169, 300–304 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Galkin A. S., Grivennikova V. G., Vinogradov A. D. (1999) FEBS Lett. 451, 157–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murai M., Sekiguchi K., Nishioka T., Miyoshi H. (2009) Biochemistry 48, 688–698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Berrisford J. M., Thompson C. J., Sazanov L. A. (2008) Biochemistry 47, 10262–10270 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fendel U., Tocilescu M. A., Kerscher S., Brandt U. (2008) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1777, 660–665 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tocilescu M. A., Fendel U., Zwicker K., Kerscher S., Brandt U. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 29514–29520 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sinha P. K., Torres-Bacete J., Nakamaru-Ogiso E., Castro-Guerrero N., Matsuno-Yagi A., Yagi T. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 9814–9823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sazanov L. A., Peak-Chew S. Y., Fearnley I. M., Walker J. E. (2000) Biochemistry 39, 7229–7235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Baranova E. A., Morgan D. J., Sazanov L. A. (2007) J Struct Biol 159, 238–242 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Baranova E. A., Holt P. J., Sazanov L. A. (2007) J. Mol. Biol. 366, 140–154 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mathiesen C., Hägerhäll C. (2002) Biochim Biophys Acta 1556, 121–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yagi T., Yano T., Di Bernardo S., Matsuno-Yagi A. (1998) Biochim Biophys Acta 1364, 125–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Amarneh B., Vik S. B. (2003) Biochemistry 42, 4800–4808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Torres-Bacete J., Sinha P. K., Castro-Guerrero N., Matsuno-Yagi A., Yagi T. (2009) J. Biol. Chem. 284, 33062–33069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Han H., Sinha M. K., D'Souza L. J., Keinan E., Sinha S. C. (2004) Chemistry 10, 2149–2158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Laemmli U. K. (1970) Nature 227, 680–685 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wittig I., Braun H. P., Schägger H. (2006) Nat Protoc 1, 418–428 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schägger H., von Jagow G. (1991) Anal. Biochem. 199, 223–231 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Euro L., Belevich G., Verkhovsky M. I., Wikström M., Verkhovskaya M. (2008) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1777, 1166–1172 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hamamoto T., Hashimoto M., Hino M., Kitada M., Seto Y., Kudo T., Horikoshi K. (1994) Mol. Microbiol. 14, 939–946 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nakamaru-Ogiso E., Seo B. B., Yagi T., Matsuno-Yagi A. (2003) FEBS Lett. 549, 43–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ito M., Guffanti A. A., Wang W., Krulwich T. A. (2000) J. Bacteriol. 182, 5663–5670 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Melo A. M., Bandeiras T. M., Teixeira M. (2004) Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 68, 603–616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Zannoni D. (2004) Respiration in Archaea and Bacteria, Kluwer Academic Publishers, Dordrecht; Boston [Google Scholar]

- 46.Matsushita K., Ohnishi T., Kaback H. R. (1987) Biochemistry 26, 7732–7737 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fisher N., Rich P. R. (2000) J. Mol. Biol. 296, 1153–1162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Fillingame R. H. (1997) J. Exp. Biol. 200, 217–224 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Leif H., Sled V. D., Ohnishi T., Weiss H., Friedrich T. (1995) Eur. J. Biochem. 230, 538–548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Friedrich T., van Heek P., Leif H., Ohnishi T., Forche E., Kunze B., Jansen R., Trowitzsch-Kienast W., Höfle G., Reichenbach H. (1994) Eur. J. Biochem. 219, 691–698 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sato-Watanabe M., Mogi T., Ogura T., Kitagawa T., Miyoshi H., Iwamura H., Anraku Y. (1994) J. Biol. Chem. 269, 28908–28912 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Oberlies N. H., Chang C. J., McLaughlin J. L. (1997) J. Med. Chem. 40, 2102–2106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stolpe S., Friedrich T. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 18377–18383 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Dlasková A., Hlavatá L., Jezek J., Jezek P. (2008) Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 40, 2098–2109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dibrov P., Fliegel L. (1998) FEBS Lett. 424, 1–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Padan E., Kozachkov L., Herz K., Rimon A. (2009) J. Exp. Biol. 212, 1593–1603 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Toyoshima C., Nomura H. (2002) Nature 418, 605–611 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bénit P., Slama A., Rustin P. (2008) Mol. Cell Biochem. 314, 45–50 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kita K., Konishi K., Anraku Y. (1984) J. Biol. Chem. 259, 3375–3381 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Khadilkar A., Iannuzzi P., Orlowski J. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 43792–43800 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pedersen S. F., King S. A., Nygaard E. B., Rigor R. R., Cala P. M. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 19716–19727 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Steuber J. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 26817–26822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Gemperli A. C., Schaffitzel C., Jakob C., Steuber J. (2007) Arch Microbiol 188, 509–521 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Efremov R. G., Baradaran R., Sazanov L. A. (2010) Nature 465, 441–445 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.