Abstract

Polo-like kinase 3 (Plk3) plays an important role in the regulation of cell cycle progression and stress responses. Plk3 also has a tumor-suppressing activity as aging PLK3-null mice develop tumors in multiple organs. The growth of highly vascularized tumors in PLK3-null mice suggests a role for Plk3 in angiogenesis and cellular responses to hypoxia. By studying primary isogenic murine embryonic fibroblasts, we tested the hypothesis that Plk3 functions as a component in the hypoxia signaling pathway. PLK3−/− murine embryonic fibroblasts contained an enhanced level of HIF-1α under hypoxic conditions. Immunoprecipitation and pulldown analyses revealed that Plk3 physically interacted with HIF-1α under hypoxia. Purified recombinant Plk3, but not a kinase-defective mutant, phosphorylated HIF-1α in vitro, resulting in a major mobility shift. Mass spectrometry identified two unique serine residues that were phosphorylated by Plk3. Moreover, ectopic expression followed by cycloheximide or pulse-chase treatment demonstrated that phospho-mutants exhibited a much longer half-life than the wild-type counterpart, strongly suggesting that Plk3 directly regulates HIF-1α stability in vivo. Combined, our study identifies Plk3 as a new and essential player in the regulation of the hypoxia signaling pathway.

Keywords: Hypoxia, Protein Stability, Protein-serine/threonine Kinase, Signal Transduction, Ubiquitination, Cell Proliferation, Cell Survival, Polo-like Kinases, Stress Responses, Tumor Suppression

Introduction

The Polo-like kinase (Plk)3 family is composed of evolutionarily conserved proteins that play an important role in the regulation of cell survival and proliferation, cell cycle progression, and stress responses (1, 2). Mammalian cells contain four proteins (Plk1, Plk2, Plk3, and Plk4) that exhibit a marked sequence homology to Drosophila Polo, a gene product known to have multiple functions in mitosis (1, 2). Plk3, a member of the Polo-like kinase family, plays an important role in regulating cell cycle progression (3, 4) and cell cycle checkpoints in response to genotoxic stresses (5, 6). Plk3 is also strongly implicated in tumorigenesis. Aberrant expression of Plk3 is found in multiple tumors (2, 7). The human PLK3 gene (PLK3) is localized to the short arm of the chromosome 1 (1p32), a region that displays loss of heterozygosity or homozygous deletions in many types of cancer and has been proposed to harbor tumor susceptibility genes (8, 9). A recent mouse genetic study showed that PLK3−/− mice develop tumors in multiple organs at an enhanced rate (10). Many of the tumors developed in the PLK3 null mice are large in size and are highly vascularized (10), suggesting that this kinase may be involved in regulating the angiogenesis pathway.

Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 (HIF-1) is a transcription factor that consists of HIF-1α and HIF-1β subunits (11, 12). HIF-1α accumulates under hypoxic conditions whereas HIF-1β is constitutively expressed. In the presence of O2 (normoxia), HIF-1α is hydroxylated on prolines 402 and 564 by prolyl hydroxylases and on arginine 803 by factor-inhibiting HIF-1 (11, 12). Hydroxylated HIF-1α is recognized by the von Hippel Lindau protein, a ubiquitin E3 ligase, for polyubiquitination and subsequent degradation by the proteasome (12). Under hypoxic conditions, HIF-1α molecules are not hydroxylated, and consequently they accumulate, dimerize with HIF-1β, and translocate to the nucleus (11, 12). Nuclear HIF-1 binds to the hypoxia-responsive element and activates the transcription of a variety of target genes whose products in turn mediate hypoxic responses (11).

HIF-1α protein levels and its activity are also regulated by a signaling cascade that consists of a series of protein kinases and protein/lipid phosphatases. The PI3K/PTEN/PDK1/Akt/HIF-1α pathway is known to play a critical role in tumorigenesis and angiogenesis (13, 14). Loss of PTEN function and increased activity of phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K) and the Akt protein kinase are associated with enhanced expression of HIF-1α and its homologs during hypoxia (15–17). Fully activated Akt1 negatively regulates glycogen synthase kinase (GSK3β) activity by phosphorylation of serine 9 (p-GSK3β-Ser9) (18, 19). Several studies have shown that hypoxia down-regulates the activity of GSK3β due to Akt1 activation (14, 20), leading to a net increase in HIF-1α levels. GSK3β directly phosphorylates HIF-1α on a cluster of serine residues (Ser551, Ser555, and Ser589) in the oxygen-dependent degradation domain, and this phosphorylation enhances HIF-1α degradation by the proteasomal pathway (21).

To elucidate the molecular mechanism by which Plk3 regulates the angiogenesis pathway, we examined the expression of HIF-1α in paired primary isogenic murine embryonic fibroblasts. We observed that PLK3−/− murine embryonic fibroblasts (MEFs) contained an enhanced level of HIF-1α under hypoxic conditions. A series of biochemical studies revealed that purified recombinant Plk3 phosphorylated HIF-1α on Ser576 and Ser657, two conserved residues. Our subsequent molecular analyses confirmed that Plk3-mediated phosphorylation of HIF-1α was important for regulating its stability.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Cell Lines and Antibodies

A549 and HEK293T cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection. Cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) and antibiotics (100 μg of penicillin and 50 μg of streptomycin sulfate per ml) under 5% CO2. Primary wild-type and PLK3−/− MEFs were derived from embryonic day 14.5 embryos of the respective genotype, produced from the crossing of PLK3+/− mice. Primary MEF cells were cultured in DMEM supplemented with 15% FBS and antibiotics (as above) under 5% CO2. In all experiments that involved the use of MEFs, only primary MEFs of third to fifth passages were used for various studies. Antibody for HIF-1α was purchased from Bethyl Laboratories. Plk3 antibody was obtained from BD Biosciences. β-Actin antibody was purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. Antibody for GFP was purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology.

Recombinant Proteins and Other Reagents

Recombinant His6-tagged Plk3 proteins were expressed using the baculoviral expression system and purified from Sf9 insect cells as described previously (22). Briefly, Sf9 cells (ATCC) cultured in Grace's insect cell culture medium were infected with Plk3 baculovirus. Three days after infection, cells were collected and lysed in a lysis buffer (50 mm NaH2PO4, 300 mm NaCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 20 mm imidazole, 1 mm PMSF, 2 μm pepstatin A, 10 units/ml aprotinin). Cell lysates were cleared by centrifugation and then incubated with Ni-NTA-agarose resins for 3 h at 4 °C. Plk3 protein was then eluted from Ni-NTA resins with lysis buffer containing 200 mm imidazole after extensive wash of the resins with the lysis buffer. The eluted protein was dialyzed into the storage buffer (25 mm Tris, pH 7.4, 5 mm EGTA, 2 mm DTT, 0.1% Triton X-100, and 50% glycerol) and stored at −80 °C for subsequent use.

Recombinant proteins for full-length (catalog no. 7436) and partial GSK3β (catalog no. 9237) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. HIF-1α protein was obtained from Abcam (catalog no. Ab73661). Casein and wortmannin were purchased from Sigma.

Plasmids, Mutagenesis, and Transfection

Human plasmids for HIF-1α (wild type and HIF-1α-P402A/P564A mutant) were obtained from Adgene. HIF-1α mutagenesis on Ser576 and/or Ser657 was carried out using the QuikChange Lightning Multi Site-directed Mutagenesis kit from Stratagene according to the instructions provided by the supplier. Individual mutations were confirmed by DNA sequencing. Plasmid transfection was performed using Lipofectamine reagents from Invitrogen according to the protocol provided by the manufacturer.

Plk3 Kinase Assays

Plk3 kinase assays were carried out essentially using the protocol described (5). Briefly, the indicated amounts of recombinant His6-Plk3 protein were added to kinase assay buffer (20 mm HEPES, pH 7.4, 2 mm EGTA, 10 mm MgCl2, 5 mm MnCl2, 1 mm DTT). Substrates (0.5 μg) were then added to achieve a total volume of 20 μl. Kinase reactions were initiated by the addition of 5 μl of either the radioactive ATP mix (50 mm MgCl2, 0.1 mm ATP, 5 μCi of [γ-32P]ATP) or the cold ATP mix (50 mm MgCl2, 5 mm ATP). After incubation for 30 min at 30 °C, SDS sample buffer was supplemented to each reaction. Proteins fractionated on SDS-denaturing gels were transferred to PVDF membranes followed by autoradiography or immunoblotting.

Western Blotting

Standard Western blotting procedure was using throughout the study. SDS-PAGE was carried out using the mini gel system from Bio-Rad. Proteins were transferred to PVDF membranes which were blocked with PBS + 0.1% Tween 20 containing 5% nonfat dry milk. The membranes were then incubated overnight with primary antibodies using dilutions suggested by the manufacturers. The membranes were then incubated with secondary antibodies for 1 h at room temperature. After thorough washing with PBST buffer, signals on membranes were developed with an ECL system (Pierce).

Immunoprecipitation and Pulldown Assays

For immunoprecipitation, cells were lysed in the lysis buffer (20 mm HEPES, pH7.6, 400 mm NaCl, 0.1% Nonidet P-40, 1 mm DTT, 1 mm EDTA, 1 mm NaF, 1 mm sodium orthovanadate, 500 μm PMSF, 2 μm pepstatin A, 10 units/ml aprotinin) and cleared by centrifugation. One μg of antibody and 40 μl of protein G-agarose resin (50/50; Upstate Biotechnology) were then added to 1–3 mg of cell lysates and incubated at 4 °C for 3 h to overnight followed by extensively washing with the lysis buffer. Proteins on the resins were eluted with SDS sample buffer and then subjected to analysis by SDS-PAGE followed by Western blotting with appropriate antibodies.

For the HIF-1α pulldown assay, recombinant His6-Plk3 was affinity-purified and subsequently conjugated to Ni-NTA resin (Qiagen). Plk3-conjugated Ni-NTA resin or the resin alone was incubated for 3 h at 4 °C with A549 cells exposed to hypoxia. The resin was extensively washed, and proteins that were bound to either His6-Plk3 or the control resin were eluted in the SDS sample buffer and subjected to SDS-PAGE analysis followed by Western blotting with HIF-1α antibody.

Half-life Study

Equal amounts (0.2 μg/well of 6-well plates) of HA-tagged wild-type or mutant HIF-1α plasmid constructs were individually transfected into HEK293 cells. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cycloheximide was added at a final concentration of 50 μg/ml to block new protein synthesis. Cells were then harvested at the indicated time points for Western blot analysis using an anti-HA antibody to detect ectopically expressed HIF-1α or the mutant counterparts. Signals detected on blots were quantified by densitometry, and the data were plotted. Half-lives from each were determined.

Pause and Chase Procedure

To determine the half-life of HIF-1α, we also employed the pulse-chase procedure in cells ectopically expressing transfected with HIF-1α and its phospho-mutant. Briefly, three 10-cm dishes of HEK293T cells were transfected with HA-tagged HIF-1α constructs (4 μg of DNA/dish). Transfected cells were split into seven 10-cm cultural dishes 1 day after transfection. Twenty-four hours later, cells were starved in methionine/cysteine-free DMEM containing 10% FBS for 1 h at 37 °C. The cells were then pulsed with [35S]methionine/cysteine (200 μCi/ml Express-35S protein-labeling mix; PerkinElmer Life Sciences) in the methionine/cysteine-free DMEM for 30 min at 37 °C. After pulse, cells were cultured in the complete DMEM containing 10% FBS. The treated cells were harvested at the indicated time points and lysed in the radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer. HA-HIF-1α or HA-HIF-1α-S576A/S657A was immunoprecipitated with the anti-HA antibody (Cell Signaling), and the immunoprecipitates were subjected to SDS-PAGE followed by autoradiography. HIF-1α-specific signals were quantified by densitometry scanning.

Detection of Phosphorylation Sites by Mass Spectrometry

HIF-1α recombinant protein phosphorylated by His6-Plk3 using the cold kinase assay protocol as described above was fractionated on an SDS-denaturing gel. After Coomassie Brilliant Blue staining, gels were sliced and subjected to mass spectrometric analysis at the Center for Functional Genomics, the Research Foundation of SUNY at Albany. The phosphorylation status was confirmed either by companion kinase reactions using the hot kinase assay protocol or by the appearance of a mobility shift.

RESULTS

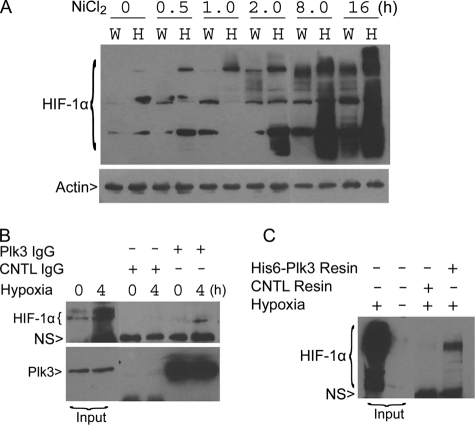

To elucidate the potential role of Plk3 in regulating the hypoxia response pathway, we first examined expression of HIF-1α in paired (wild-type and PLK3−/−) primary MEFs treated with NiCl2, a hypoxia mimetic. HIF-1α levels were constitutively higher in PLK3−/− MEFs than those in wild-type MEFs; the hypoxic condition greatly stabilized HIF-1α in both types of MEFs (Fig. 1A). However, the native, as well as the ubiquitinated, HIF-1α was accumulated at a much greater extent in PLK3-null MEFs (Fig. 1A). To examine the direct regulatory relationship between Plk3 and HIF-1α, we examined their physical interaction during normoxic and hypoxic conditions. Co-immunoprecipitation experiments revealed that the Plk3 antibody, but not a control IgG, pulls down HIF-1α in cells treated with hypoxia for 4 h (Fig. 1B). Subsequent pulldown experiments showed that His6-Plk3 resin, but not the control resin, precipitated HIF-1α-immunoreactive signals in cells treated with hypoxia (Fig. 1C). Therefore, these studies suggest that Plk3 interacts with HIF-1α during hypoxia.

FIGURE 1.

Plk3 functionally and physically interacts with HIF-1α. A, paired wild-type (W) and PLK3 homozygously disrupted (H) MEFs were treated with NiCl2, a hypoxia mimetic, for various times. Equal amounts of protein lysates were blotted for HIF-1α and β-actin. HIF-1α polyubiquitinated forms are indicated. B, A549 cells were treated with or without hypoxic stress for 4 h. An equal amount of cell lysates was immunoprecipitated with Plk3 IgG or with control IgG. After washing, the immunoprecipitates, along with the lysate inputs, were blotted for HIF-1α and Plk3. NS denotes a nonspecific band. C, recombinant His6-Plk3 was immobilized to Ni-NTA resin. His6-Plk3 resin, as well as control (CNTL) resin, was incubated with an equal amount of lysates from A549 cells exposed to the hypoxic stress. After thorough washing, proteins bound to either resin, along with lysate inputs, were blotted for HIF-1α. NS denotes a nonspecific band.

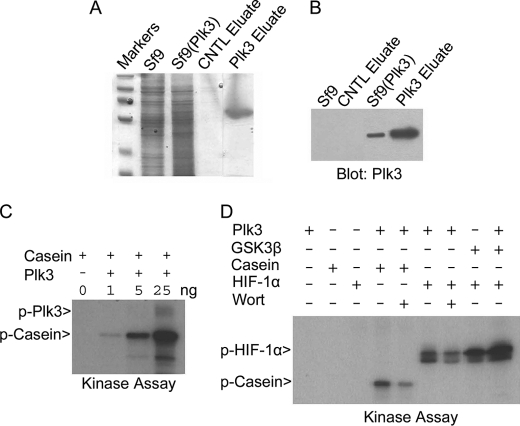

We next tested the possibility that HIF-1α might be a substrate of Plk3. Recombinant His6-Plk3 was expressed in Sf9 cells, purified using the Ni-NTA affinity approach (22). Purity and specificity of recombinant His6-Plk3 were confirmed by Coomassie Blue staining and immunoblotting, respectively (Fig. 2, A and B). Purified His6-Plk3 was first tested for its activity toward casein, a known in vitro substrate of Polo-like kinases (6). In vitro kinase assays using [γ-32P]ATP confirmed that His6-Plk3 was highly active toward casein (Fig. 2C). Subsequent kinase assays revealed that His6-Plk3 efficiently phosphorylated recombinant HIF-1α in vitro and that the phosphorylation was partially inhibited by wortmannin (Fig. 2D), which is known to inhibit Polo-like kinases at nanomolar concentrations (23). Consistent with previously reported data (21), recombinant GSK3β phosphorylated HIF-1α, and we extended this finding to show that the phosphorylation was enhanced by the presence of His6-Plk3 (Fig. 2D). This suggests that there is an additive effect between GSK3β and Plk3 kinases on the phosphorylation of HIF-1α.

FIGURE 2.

Plk3 phosphorylates HIF-1α in vitro. A, recombinant His6-Plk3 was expressed in Sf9 cells and purified using the Ni-NTA affinity approach as described under “Experimental Procedures.” Mock purification was carried out using Sf9 control cell lysates. Purified His6-Plk3 was confirmed by Coomassie Blue staining. B, Sf9 cell lysates infected with or without His6-Plk3 baculovirus, along with eluted proteins, were blotted with Plk3 antibody. C, different amounts of Plk3 were assayed for kinase activity toward casein in the kinase reaction supplemented with [γ-32P]ATP. A representative autoradiogram is shown. D, in vitro kinase assays were carried out in the presence of [γ-32P]ATP, as well as the various components, as indicated. Wort stands for wortmannin. A representative autoradiogram is shown.

To further confirm the phosphorylation by Plk3, we made a Plk3 kinase-dead mutant by replacing lysine 91 with arginine. The resulting mutant was expressed as a His6-tagged protein using baculoviral expression approach and purified in a manner similar to wild-type Plk3. In vitro protein kinase assays show that Plk3 but not Plk3-K91R efficiently phosphorylated HIF-1α (Fig. 3A). Immnoblotting confirmed that a similar amount of Plk3 or Plk3-K91R protein was used in the kinase assays. This series of experiments thus indicates that it is Plk3 but not a contaminating kinase that phosphorylates HIF-1α in vitro.

FIGURE 3.

Plk3 phosphorylates HIF-1α on Ser576 and Ser657. A, both Plk3 and Plk3-K91R were expressed in Sf9 cells and purified using NTA-Ni resin. Purified Plk3 and Plk3-K91R were assayed for their kinase activities toward HIF-1α in vitro in a kinase buffer containing [γ-32P]ATP. A representative autoradiogram is shown. B, kinase assays were carried out in the presence of various components as indicated. After the reaction, the samples were analyzed on SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie Blue staining. A lane of “hot” sample (autoradiogram on the left) that ran on the same gel is also shown. C, HIF-1α sequence representation shows the relative positions of serine phosphorylation sites Ser576 (upper panel) and Ser657 (lower panel) to HIF-1α domains. ODDD, oxygen-dependent degradation domain; N-TAD, N-terminal transactivation domain; NES, nuclear export signal; NLS, nuclear localization signal; C-TAD, C-terminal transactivation domain. The nuclear export signal in the lower panel is highlighted by underlining. Ser641 and Ser643 are known to be phosphorylated by ERKs. D, amino acid alignment is shown of HIF-1α molecules from different species in the region that were targeted by Plk3. The conserved serine residues are highlighted.

To determine whether phosphorylation of HIF-1α by Plk3 could cause a mobility shift, kinase assays were carried out in buffer supplemented with or without ATP (either cold or 32P-labeled). After reaction, the samples were fractionated on SDS-PAGE followed by Coomassie Blue staining. A new band with a slower mobility appeared in the reaction containing ATP and Plk3, which coincided with the position at which the major 32P-HIF-1α migrated (Fig. 3B). Combined, these studies indicate that Plk3 directly phosphorylates HIF-1α in vitro.

Mass spectrometric analyses revealed that HIF-1α was phosphorylated on serines 576 and 657 by Plk3 (data not shown). The phosphorylation sites relative to other domain structures of HIF-1α are summarized in Fig. 3C. Ser576 is localized within the oxygen-dependent degradation domain, and Ser657 is near the nuclear export signal (24, 25). These sites are evolutionarily conserved among higher animals that express HIF-1α. Ser657 is downstream of a nuclear export signal and two serine residues (Ser641 and Ser643) (Fig. 3C, lower panel) that are known to be phosphorylated by mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs) (25). Although S657 is followed by a proline residue in human HIF-1α, this proline is not very conserved (Fig. 3D), suggesting that proline-directed kinase families are not involved in phosphorylating S657. Supporting this notion, to date no other known kinases, including MAPKs, are reported to phosphorylate the newly identified Plk3 phosphorylation sites.

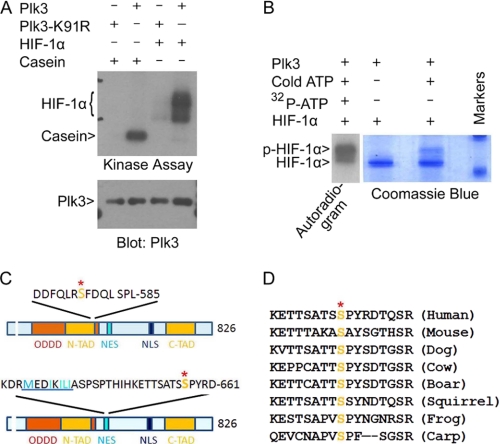

To determine whether Plk3-catalyzed phosphorylation of HIF-1α regulates its stability in vivo, we made a series of HIF-1α mutants by replacing serines 576 and/or 657 with alanines (Fig. 4A). Because HIF-1α is greatly destabilized after hydroxylation on prolines 402 and 564 due to the recognition by and subsequent interaction with VHL (12), we also made these phospho-mutants in the HIF-1α cDNA with these two proline residues replaced with alanines (Fig. 4A). Various HIF-1α mutants, as well as the wild type, of HIF-1α were transfected into HEK293 cells. A GFP expression construct was used in co-transfection for normalizing the transfection efficiency. Ectopically expressed wild-type HIF-1α was unstable, leading to a very low steady-state level (Fig. 4, B and C). Mutation of either Ser576 or Ser657 (HIF-1αS576A or HIF-1αS657A) greatly stabilized the transfected HIF-1α; replacing both serine residues with alanines further boosted the steady-state level of the HIF-1α mutant protein (HIF-1αS576A/S657A; Fig. 4, B and C). Consistent with the role of prolyl hydroxylation in destabilizing HIF-1α, the prolyl mutant (HIF-1αP402A/P564A) was expressed at a greatly enhanced rate compared with the wild-type HIF-1α (Fig. 4, B and 4C). Furthermore, compound mutations at both prolyl sites and Plk3-targeting phosphorylation site(s) further increased the steady-state levels of HIF-1α (Fig. 4, B and C), strongly suggesting that Plk3 regulates HIF-1α stability in vivo by phosphorylation. As a control, we also examined the levels of Akt1 and GSK3β. Ectopic expression of HIF-1α mutants did not significantly alter their expression (Fig. 4B).

FIGURE 4.

Phosphorylation of HIF-1α by Plk3 leads to its destabilization. A, schematic representation of HIF-1α and its mutants (phospho- and/or hydroxylation mutants) used for transfection analyses is shown. B, HEK293 cells were co-transfected with various expression constructs as shown in C, and a GFP expression construct for normalization of transfection efficiency for 1 day is presented. Equal amounts of cell lysates were Western blotted for HIF-1α, Akt1, GSK3β, GFP, and β-actin. C, the signals shown in B were quantified by densitometry.

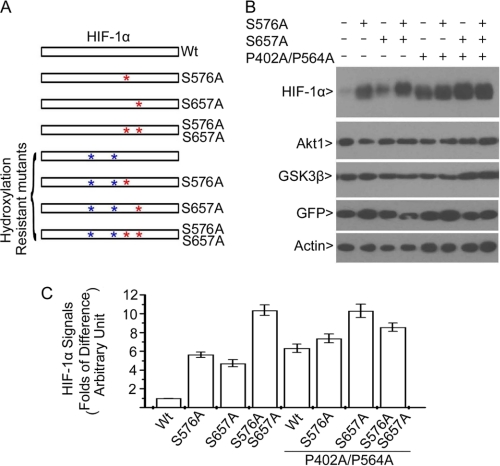

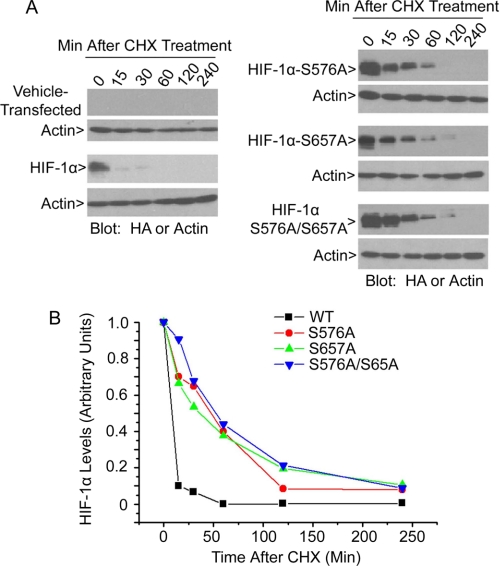

To confirm that increased steady-state levels of phospho-mutants of HIF-1α were primarily due to the inhibition of protein degradation, we transfected HEK293 cells with various HA-tagged phospho-mutant constructs as well as the wild-type HIF-1α followed by treatment with cycloheximide for various times. Western blotting confirmed that mutant HIF-1α proteins either with a single-site mutation or with double-site mutations were expressed at a much higher level than the wild-type HIF-1α (Fig. 5, A and B). More importantly, whereas the half-life of wild-type HIF-1α was less than 10 min, half-lives of HIF-1α-S576A, HIF-1α-S657A, and HIF-1α-S576A/S657A were about 37, 49, and 51 min, respectively (Fig. 5B). These studies again support the notion that Plk3-mediated phosphorylation destabilizes HIF-1α.

FIGURE 5.

Plk3 phosphorylation-resistant mutants have longer half-lives than the wild-type HIF-1α. A, HEK293 cells were transfected with an HA-tagged HIF-1α expression construct or a construct expressing Plk3 phosphorylation-resistant mutant (HA-HIF-1α-S576A, HA-HIF-1α-S657A, or HA-HIF-1α-S576A/S657A) or vehicle for 1 day. Transfected cells were then treated with cycloheximide (CHX) for various times as indicated. Equal amounts of cell lysates from each treatment point were blotted for ectopically expressed HIF-1α protein using the anti-HA tag antibody. B, HIF-1α and its mutant protein signals shown in A were quantified by densitometry scanning, and the data were summarized from three independent experiments.

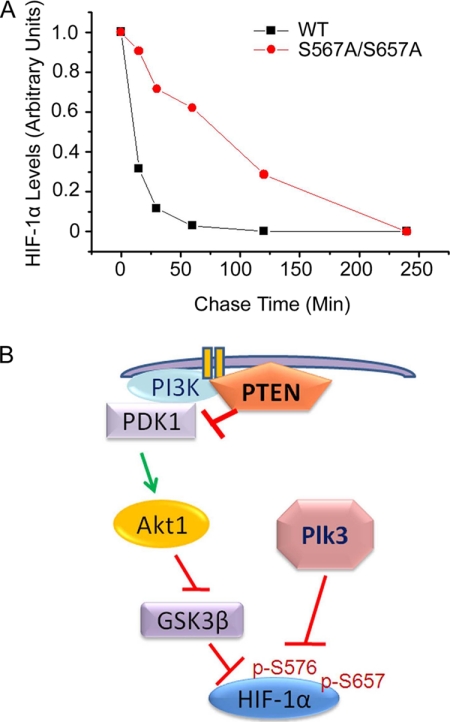

As a complementary approach to confirming that Plk3-mediated phosphorylation could destabilize HIF-1α, we carried out pulse-chase experiments in cells ectopically expressing transfected HA-HIF-1α or HA-HIF-1α-S576A/S657A. HEK293 cells transfected with HA-HIF-1α or the mutant expression construct for 24 h were pulsed with [35S]methionine/cysteine followed by chase in an isotope-free medium. At various times of chase, HEK293 cells were collected for lysate preparation. Equal amounts of cell lysates were then immunoprecipitated with the anti-HA antibody, and immune precipitates were fractionated on SDS-denaturing gels followed by autoradiography. HIF-1α-specific signals were qualified, and the data are summarized in Fig. 6A. HIF-1α had a half-life of <10 min whereas HIF-1α-S576A/S657A mutant protein had a half-life of approximately 60 min, which is consistent with the data from the cycloheximide experiment.

FIGURE 6.

Plk3 functions as part of HIF-1α regulatory network. A, HEK293 cells transfected with HA-HIF-1α or with HA-HIF-1α-S576A/S657A for 48 h were pulsed with [35S]methionine/cysteine for 0.5 h followed by chase in an isotope-free medium for various periods of time. HEK293 cells were collected for lysate preparation. Equal amounts of lysates from various treatments were immunoprecipitated with the anti-HIF-1α antibody. The immunoprecipitates were fractionated on SDS-denaturing gels followed by autoradiography. HIF-1α-specific signals were qualified via densitometry, and the data are summarized. B, model is proposed illustrating how Plk3 regulates the hypoxia response network. Green arrows denote positive regulation; red bars denote negative regulation.

Given the series of new biochemical, molecular, and genetic data obtained, we propose the following model to explain the molecular mode of action of Plk3 in the hypoxic response (Fig. 6B). It is well known that the PI3K/PTEN/PDK1/Akt signaling axis regulates hypoxia responses. Active Akt1 phosphorylates GSK3β on Ser9. Phosphorylated GSK3β-Ser9 is inactive and thus is incapable of phosphorylating and destabilizing HIF-1α, leading to an increase of this protein under hypoxia. Plk3 has at least one primary target in the hypoxic response network, which is HIF-1α. Plk3 phosphorylates HIF-1α on Ser576 and Ser657, leading to its destabilization in a manner similar to that regulated by GSK3β.

DISCUSSION

Tumor development and progression are frequently the result of deregulated protein kinases that control cell proliferation. Extensive research in the past has revealed that Plks, a family of evolutionarily conserved proteins, are targeted for deregulation in cancer cells (26). We have previously shown that Plk3 functions as an important regulator for cell proliferation in vitro and that it suppresses tumorigenesis in vivo (10, 27). Through a series of biochemical, molecular, and genetic analyses, we now demonstrate for the first time that Plk3 is a negative regulator of HIF-1α stability. Specifically, PLK3−/− MEFs are hypersensitive to the induction of HIF-1α under hypoxic conditions. In vitro biochemical studies reveal that Plk3 physically interacts with HIF-1α and directly phosphorylates this transcription factor. We have also demonstrated that HIF-1α is a phospho-protein in vivo. Therefore, our current study identifies Plk3 as an essential component in the regulatory network of cell survival, angiogenesis, and hypoxic responses.

Extensive studies in the past have shown that HIF-1α is regulated primarily at the protein stability level (12). The fact that an entire array of cellular machinery is involved in constant transcription of the HIF-1α gene and its translation, and in its degradation, underscores the importance of this transcription factor in mounting a rapid, but regulated response during hypoxic stress. Given that the activities of protein kinases can be rapidly modulated in response to external or internal stimuli, it is not surprising that HIF-1α is regulated by a variety of post-translational mechanisms, including phosphorylation. Our current study adds Plk3 as a new and significant player to the HIF-1α regulatory network. Plk3 physically interacts with HIF-1α and phosphorylates it on Ser576 and Ser657. The Ser576 residue lies within the oxygen-dependent degradation domain of HIF-1α (21), and the Ser657 residue is situated near the nuclear export signal that MAPKs are also known to phosphorylate (24, 25). The consequences of the phosphorylation by Plk3 and MAPKs, however, are very different. Whereas MAPK phosphorylation increases HIF-1α nuclear accumulation and its activity (24, 25), Plk3 destabilizes this transcription factor.

Tumor tissues are highly hypoxic due to an insufficient and defective vasculature present in a highly proliferative tumor mass. In this context, active HIF-1 binds to and transactivates a panel of genes whose products are important to the modulation of a vast range of cellular functions, allowing tumor cells not only to survive but also to continue to proliferate. High levels of HIF-1α are tightly associated with poor prognosis in many human malignancies. Molecular responses to the hypoxic conditions are primarily mediated through the rapid accumulation of HIF-α. HIF-1α is stabilized through the inhibition of several oxygen-dependent hydroxylases, including prolyl hydroxylases. However, it remains unclear whether and how protein phosphorylation plays an essential role in the modulation of HIF-1α stability/expression. Although PI3K, Akt1, ERKs, and Plk3 are differentially regulated in response to various stresses or physiological conditions, growing evidence suggests that these signaling components function in a coordinated and integrated manner, regulating each other and downstream components, including HIF-1α that play a major role in cell survival, malignant transformation, and tumor development, as well as progression. A detailed understanding of molecular regulation of HIF-1α will add significantly to the existing knowledge of hypoxic, as well as oxidative stress, responses in both normal and neoplastic cells and will provide novel insights into the mechanism of cancer drug resistance. Therefore, the signaling network controlled by PI3K, Akt1, and GSK3, as well as Plk3, is crucial not only for homeostasis of HIF-1α but also for the survival and proliferation of malignant cells.

Acknowledgments

We thank Qishan Lin at the Center for Functional Genomics, the University at Albany, for assistance in the mass spectrometric study and Nedda Tichi for administrative assistance.

- Plk

- Polo-like kinase

- GSK3β

- glycogen synthase kinase 3β

- HIF

- hypoxia-inducible factor

- MEF

- murine embryonic fibroblast

- Ni-NTA

- nickel-nitrilotriacetic acid.

REFERENCES

- 1.Barr F. A., Silljé H. H., Nigg E. A. (2004) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 5, 429–440 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dai W. (2005) Oncogene 24, 214–216 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zimmerman W. C., Erikson R. L. (2007) Cell Cycle 6, 1314–1318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zimmerman W. C., Erikson R. L. (2007) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 1847–1852 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xie S., Wang Q., Wu H., Cogswell J., Lu L., Jhanwar-Uniyal M., Dai W. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 36194–36199 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Xie S., Wu H., Wang Q., Cogswell J. P., Husain I., Conn C., Stambrook P., Jhanwar-Uniyal M., Dai W. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 43305–43312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Li B., Ouyang B., Pan H., Reissmann P. T., Slamon D. J., Arceci R., Lu L., Dai W. (1996) J. Biol. Chem. 271, 19402–19408 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chizhikov V., Zborovskaya I., Laktionov K., Delektorskaya V., Polotskii B., Tatosyan A., Gasparian A. (2001) Mol. Carcinog. 30, 151–158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Perotti D., Pettenella F., Luksch R., Giardini R., Gambirasio F., Ferrari D., Fossati-Bellani F., Biondi A. (1999) Haematologica 84, 110–113 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang Y., Bai J., Shen R., Brown S. A., Komissarova E., Huang Y., Jiang N., Alberts G. F., Costa M., Lu L., Winkles J. A., Dai W. (2008) Cancer Res. 68, 4077–4085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brahimi-Horn M. C., Pouysségur J. (2009) J. Cell Sci. 122, 1055–1057 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ke Q., Costa M. (2006) Mol. Pharmacol. 70, 1469–1480 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mottet D., Dumont V., Deccache Y., Demazy C., Ninane N., Raes M., Michiels C. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 31277–31285 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schnitzer S. E., Schmid T., Zhou J., Eisenbrand G., Brüne B. (2005) FEBS Lett. 579, 529–533 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Emerling B. M., Weinberg F., Liu J. L., Mak T. W., Chandel N. S. (2008) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 105, 2622–2627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Phillips R. J., Mestas J., Gharaee-Kermani M., Burdick M. D., Sica A., Belperio J. A., Keane M. P., Strieter R. M. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 22473–22481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhong H., Chiles K., Feldser D., Laughner E., Hanrahan C., Georgescu M. M., Simons J. W., Semenza G. L. (2000) Cancer Res. 60, 1541–1545 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gong R., Rifai A., Dworkin L. D. (2005) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 330, 27–33 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Huang J., Manning B. D. (2009) Biochem. Soc Trans. 37, 217–222 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jiang B. H., Jiang G., Zheng J. Z., Lu Z., Hunter T., Vogt P. K. (2001) Cell. Growth Differ. 12, 363–369 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Flügel D., Görlach A., Michiels C., Kietzmann T. (2007) Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 3253–3265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ouyang B., Li W., Pan H., Meadows J., Hoffmann I., Dai W. (1999) Oncogene 18, 6029–6036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liu Y., Shreder K. R., Gai W., Corral S., Ferris D. K., Rosenblum J. S. (2005) Chem Biol 12, 99–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mylonis I., Chachami G., Paraskeva E., Simos G. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 27620–27627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mylonis I., Chachami G., Samiotaki M., Panayotou G., Paraskeva E., Kalousi A., Georgatsou E., Bonanou S., Simos G. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 33095–33106 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Strebhardt K., Ullrich A. (2006) Nat. Rev. Cancer. 6, 321–330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang Q., Xie S., Chen J., Fukasawa K., Naik U., Traganos F., Darzynkiewicz Z., Jhanwar-Uniyal M., Dai W. (2002) Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 3450–3459 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]