Abstract

Hemes are prosthetic groups that participate in diverse biochemical pathways across phylogeny. Although heme can also regulate broad physiological processes by directly modulating gene expression in Metazoa, the regulatory pathways for sensing and responding to heme are not well defined. Caenorhabditis elegans is a heme auxotroph and relies solely on environmental heme for sustenance. Worms respond to heme availability by regulating heme-responsive genes such as hrg-1, an intestinal heme transporter that is up-regulated by >60-fold during heme depletion. To identify the mechanism for the heme-dependent regulation of hrg-1, we interrogated the hrg-1 promoter. Deletion and mutagenesis studies of the hrg-1 promoter revealed a 23-bp heme-responsive element that is both necessary and sufficient for heme-dependent regulation of hrg-1. Furthermore, our studies show that the heme regulation of hrg-1 is mediated by both activation and repression in conjunction with ELT-2 and ELT-4, transcription factors that specify intestinal expression.

Keywords: Caenorhabditis elegans, Gene Regulation, Heme, Iron, Metals

Introduction

Heme is an iron-containing tetrapyrrole that functions as both a catalyst for reduction-oxidation reactions and an electron carrier (1). Proteins that function in processes such as oxidative metabolism, signal transduction, cell differentiation, and gas sensing utilize heme as a prosthetic group (2–5). In mammals, two transcription factors have been characterized that are involved in heme-dependent gene regulation: Bach1 and Rev-erbα. The transcriptional repressor Bach1 regulates the α- and β-subunits of hemoglobin, the iron storage protein ferritin, and the heme-degrading enzyme heme oxygenase 1 (6–11). Bach1 binds to Maf recognition element sequences in conjunction with Maf class proteins to repress gene expression in heme-deficient conditions. Under heme-replete conditions, Bach1 binds heme and is exported from the nucleus for subsequent degradation, permitting derepression of Bach1 target genes (12). Rev-erbα, a nuclear hormone receptor, regulates several circadian clock-controlled genes. In the presence of heme, Rev-erbα recruits its co-repressor, NCoR-HDAC3. This complex represses circadian controlled gluconeogenic genes, likely through the transcription factor Bmal1 (13), a key component of the circadian rhythm feedback loop and a target of Rev-erbα (14, 15). Thus, Rev-erbα coordinates circadian rhythm with heme synthesis, glucose production, and oxidative metabolism (13).

In non-mammalian metazoans, heme regulates the expression of several genes, although the molecular mechanism for this regulation is poorly understood. In the roundworm Caenorhabditis elegans, heme regulates the expression of at least 288 genes, termed hrg for heme-responsive genes (16). Among free-living animals, C. elegans is unique because it lacks the enzymes for heme synthesis. Consequently, worms are natural heme auxotrophs and must acquire heme from the environment for incorporation into hemoproteins, many of which have homologs in eukaryotes (17). Because organismal heme levels can be externally manipulated in a controlled manner, C. elegans is an ideal genetic animal model to delineate the molecular basis of gene regulation by heme.

Using C. elegans as a model system, we identified HRG-1, a transmembrane permease that is essential for heme homeostasis (18). HRG-1 transports heme from the plasma membrane and the endolysosomal lumen into the cytoplasm. In C. elegans, hrg-1 is specifically expressed in the intestine and is highly up-regulated when heme concentrations are low (18). To elucidate the molecular determinants of hrg-1 regulation by heme, we analyzed the hrg-1 promoter. Here, we report that a 23-bp heme-responsive element (HERE)2 in the hrg-1 promoter directs the heme-dependent transcriptional regulation of hrg-1. We propose that the HERE works in concert with the GATA elements for enhanced expression of hrg-1 in response to heme in worm intestinal cells.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Generation of Transgenic Worm Lines

As described previously (18), strain IQ6011 was generated by integrating 3 kb of the hrg-1 promoter fused to a GFP vector (pPD95.67) that includes the unc-54 3′-UTR into the C. elegans wild-type N2 strain. Additional worm strains were generated by microinjection or microparticle bombardment. For microinjection, wild-type N2 worms in the young gravid stage were co-injected with 50 ng each of a reporter construct and a plasmid containing the rol-6 gene using the Eppendorf FemtoJet. After 48 h, F1 animals displaying a rolling phenotype were transferred to individual nematode growth medium-agar plates (19). F2 worms displaying a rolling phenotype were maintained as transformed strains. For microparticle bombardment, ∼5 × 106 unc-119(ed3) gravid hermaphrodite animals were co-bombarded with 10 μg of reporter construct and 5 μg of unc-119 rescue plasmid (pDM016B) using the PDS-1000 particle delivery system (Bio-Rad). Worms were washed from bombardment plates and transferred to plates seeded with a lawn of Escherichia coli JM109. After a 2-week incubation at 25 °C, wild-type F2 worms were removed from plates and maintained as transformed strains. Both injected and bombarded transformed strains were made axenic by picking individual transformed worms from nematode growth medium plates to 1 ml of mCeHR-2 liquid medium supplemented with tetracycline, naladixic acid, and 20 μm heme (20). Worms were subsequently bleached and maintained as axenic strains in mCeHR-2 medium. Strains used in this study are outlined in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Transgenic C. elegans strains used in this study

| Strain | Genotype |

|---|---|

| IQ6011 | ihIs01(hrg-1(3kb)::gfp rol-6+) |

| IQ6011-2 | unc-119(ed3) III; ihEx02(hrg-1(3kb)::gfp unc-119+) |

| IQ6011-3 | ihEx03(hrg-1::gfp,rol-6+) |

| IQ6011-4 | unc-119(ed3) III; ihEx04(hrg-1::gfp unc-119+) |

| IQ6011-5 | unc-119(ed3) III; ihEx05(hrg-1Δ(−254/−160)::gfp,unc-119+) |

| IQ6011-6 | ihEx06(hrg-1Δ(−254/−99)::gfp,rol-6+) |

| IQ6011-7 | unc-119(ed3) III; ihIs07(hrg-1Δ(−92/−16)::gfp,unc-119+) |

| IQ6011-8 | unc-119(ed3) III; ihEx08(hrg-1Δ-254/−160,−92/−16)::gfp,unc-119+) |

| IQ6011-9 | ihEx09(hrg-1m(−15/−137)::gfp,rol-6+) |

| IQ6011-10 | unc-119(ed3) III; ihEx010(hrg-1m(−15/−137)::gfp,unc-119+) |

| IQ6011-11 | unc-119(ed3) III; ihEx011(hrg-1m(−15/−155)::gfp,unc-119+) |

| IQ6011-12 | unc-119(ed3) III; ihEx12(hrg-1m(−15/−150)::gfp,unc-119+) |

| IQ6011-13 | unc-119(ed3) III; ihEx13(hrg-1m(−149/−145)::gfp,unc-119+) |

| IQ6011-14 | unc-119(ed3) III; ihEx14(hrg-1m(−144/−140)::gfp,unc-119+) |

| IQ6011-15 | unc-119(ed3) III; ihEx15(hrg-1m(−14/−137)::gfp,unc-119+) |

| IQ7081 | ihEx81(egl-18::gfp,rol-6+) |

| IQ7082 | unc-119(ed3) III; ihEx82(egl-18::gfp,unc-119+) |

| IQ7083 | ihEx83(egl-18(+23)::gfp,rol-6+) |

| IQ7084 | unc-119(ed3) III; ihIs84(egl-18(+23)::gfp,unc-119+) |

| IQ7021 | ihEx21(myo-2::gfp,rol-6+) |

| IQ7022 | ihEx22(myo-2(+23)::gfp,rol-6+) |

Nematode Growth Conditions

C. elegans strains were cultivated axenically in mCeHR-2 medium supplemented with 20 μm heme at 20 °C (20). Synchronization of C. elegans strains was performed as described previously (18). For heme response assays, synchronized L1 larvae were placed in mCeHR-2 medium with either 4 or 100 μm heme. After 72 h, worms carrying the transgene of interest were separated from non-transgenic worms and analyzed for GFP expression.

Generation of Reporter Constructs

The hrg-1(3kb)::gfp, hrg-1::gfp, hrg-1(254–160)::gfp, hrg-1(254–99)::gfp, hrg-1(92–16)::gfp, and hrg-1(254–160,92–16)::gfp plasmids were constructed using the Gateway cloning system (Invitrogen). The promoter of interest, the gfp gene, and the 3′-UTR of the unc-54 gene were cloned by recombination into the entry vectors pDONR-P4-P1R, pDONR-221, and pDONR-P2R-P3, respectively, using the Gateway BP Clonase kit. The three entry clones were then recombined into a single destination vector, pDEST-R4-R3, using the Gateway LR Clonase II Plus enzyme kit. Mutation of the 23-bp element in construct hrg-1m(159–137) was generated by mutating T to G, A to C, G to T, and C to A. The egl-18(+23)::gfp construct was created by restriction enzyme cloning. A 5′-SalI restriction site and 3′-XhoI restriction site were engineered at the ends of the 23-bp HERE by PCR. The PCR product was subsequently digested and ligated to form concatamers. The concatamers were cloned into the pKKMCS vector, which contains the basal egl-18 promoter fused to gfp (a kind gift from David Eisenmann). To create myo-2(+23)::gfp, the repeated 23-bp element was directly subcloned from the pKKMCS vector to Fire vector pPD107.97. Constructs mut1, mut2, mut3, mut4, and mut5 were synthesized in hrg-1::gfp by site-directed mutagenesis (22, 23). A summary of constructs and their response is provided in Table 2. All DNA constructs were sequenced at the University of Maryland Genomics Core Facility.

TABLE 2.

Summary of GFP expression in transgenic worms

GFP levels are represented as + or − based on results from fluorescence microscopy relative to the control IQ6011 hrg-1::gfp worm.

| Construct | 4 μm | 100 μm |

|---|---|---|

| hrg-1::gfp | ++++ | − |

| hrg-1(254–160)::gfp | +++ | − |

| hrg-1(254–99)::gfp | − | − |

| hrg-1(92–16)::gfp | + | − |

| hrg-1(254–160,92–16)::gfp | − | − |

| hrg-1m(159–137)::gfp | +/− | +/− |

| mut1 | +/− | +/− |

| mut2 | +/− | +/− |

| mut3 | +/− | +/− |

| mut4 | + | − |

| mut5 | + | − |

| egl-18(+23)::gfp | ++ | − |

Microscopy

GFP levels were analyzed by fluorescence microscopy with a Leica MZ16 FA stereomicroscope. Worms transformed with DNA were immobilized in 10 μl of 10 mm levamisole on a 2% agarose pad affixed to a slide. Differential interference contrast (DIC) and fluorescence images were taken with a Leica DMIRE2 inverted microscope attached to a CCD Retiga 1300 camera controlled by Simple PCI software (Hamamatsu, Bridgewater, NJ).

GFP Quantification

To quantify GFP levels in IQ6011, synchronized L1 larvae were grown in mCeHR-2 medium supplemented with varying concentrations of heme. After 72 h, GFP expression was quantified using the COPAS (complex object parametric analyzer and sorter) BIOSORT instrument (Union Biometrica, Hollister, MA). For each heme concentration, between 300 and 400 worms were analyzed. To quantify GFP expression in all other worm strains used in this study, synchronized L1 larvae were grown in mCeHR-2 medium supplemented with 2 or 40 μm heme and grown for two generations. F2 transgenic worms in the L4 stage were immobilized in 10 mm levamisole on a 2% agarose pad, and fluorescence microscopy images were quantified by Simple PCI software using the region of interest method. GFP was quantified in 20–30 worms for each strain at each heme concentration.

hrg-1 Expression in Embryos

To obtain images of GFP expression in embryos, gravid IQ6011 hermaphrodites maintained on nematode growth medium plates seeded with E. coli strain OP50 were transferred into small aliquots of egg buffer on coverslips. The worms were cut open with a scalpel, and the entire coverslip, including egg buffer and released embryos, was placed onto a 3% agarose pad on a microscope slide. Fluorescence and DIC images were captured at ×63 using a Zeiss Axiovert 200M microscope, a BD CARV II spinning disc confocal imager, and a Hamamatsu ORCA-ER camera. Images were collected at 5-min intervals and made into a movie using IPlab. To obtain embryos for still images, IQ6011 hermaphrodites maintained axenically in mCeHR-2 medium supplemented with 4 μm heme were bleached. Embryos were placed on a 2% agar pad. Images were captured at ×63 with a Zeiss LSM 710 confocal microscope using Zen 2009 software.

RNA-mediated Interference

RNAi was conducted by feeding dsRNA induced by isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside from plasmid L4440 propagated in E. coli strain HT115(DE3). elt-1 (W09C2.1), elt-2 (C33D3.1), and elt-6 (F52C12.5) vectors were obtained from the Ahringer Library (Geneservice Ltd., Cambridge, United Kingdom); the elt-7 (C18G1.2) vector was obtained from the Vidal ORFeome Library (Open Biosystems, Huntsville, AL); and the elt-4 (C39B10.6) ORF was cloned into the feeding vector L4440 by PCR amplification of C. elegans cDNA. Bacteria were grown in LB broth supplemented with 50 μg/ml carbenicillin, 12 μg/ml tetracycline, and 4 μm heme for 5.5 h (24). Two wells of a 12-well nematode growth medium-agar plate were spotted with bacteria transformed with each construct and allowed to induce for 24 h with 1 mm isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside. Forty IQ6011 L3 larvae, grown in mCeHR-2 medium supplemented with 10 μm heme, were transferred into each well. GFP expression in the worms was analyzed 72 h after RNAi feeding with a Leica MZ16 FA stereomicroscope. Images were acquired with a Leica DMIRE2 inverted microscope equipped with a CCD camera. GFP was quantified using the COPAS instrument.

Alignment of the hrg-1 Promoter

The nucleotide sequences of the C. elegans, Caenorhabditis briggsae, and Caenorhabditis remanei hrg-1 promoters were obtained from WormBase and then aligned using ClustalW 2.0. Identical nucleotides were highlighted with reverse-shaded boxes.

5′-Rapid Amplification of cDNA Ends (RACE)

The SMART RACE cDNA amplification kit (Clontech) was used to generate cDNA for RACE PCR analysis. All primers have a Tm between 62 and 65 °C. PCR amplification of cDNA was done using the Advantage 2 PCR enzyme system (Clontech). PCR products were cloned into the pCRII vector (TOPO TA cloning system, Invitrogen).

RESULTS

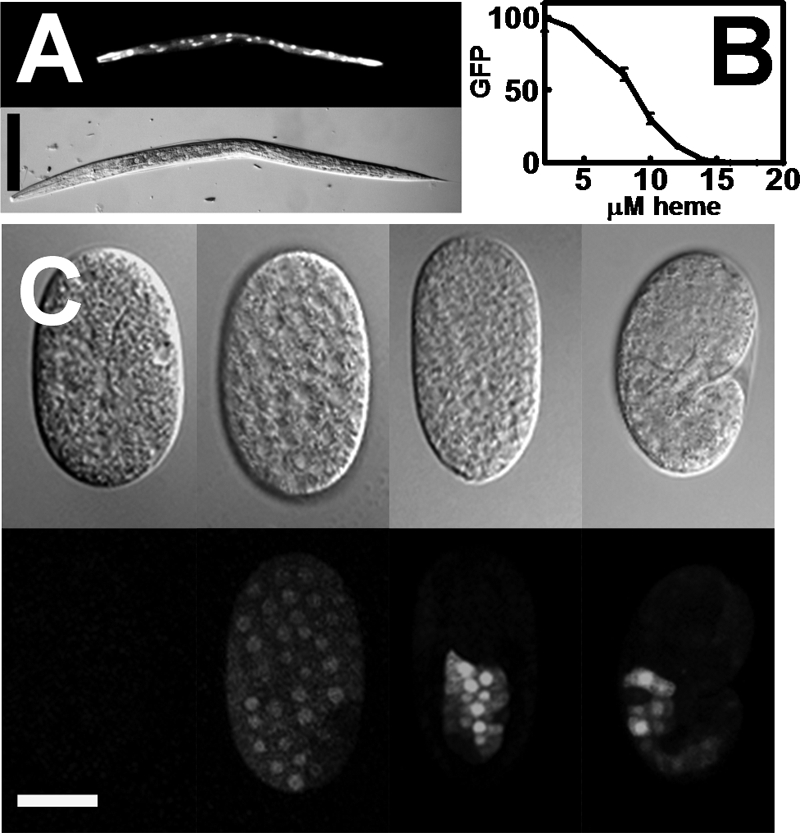

Developmental and Heme-dependent Regulation of hrg-1

To investigate the heme-dependent regulation of hrg-1 in C. elegans, we first analyzed the expression pattern of hrg-1 in transgenic worms that stably expressed the gfp reporter fused to 3 kb of the hrg-1 putative promoter and the unc-54 3′-UTR (strain IQ6011) (Table 1) (18). This hrg-1 reporter gene was highly and specifically expressed in the C. elegans intestine (Fig. 1A). We then analyzed the expression of hrg-1 as a function of heme concentrations by exposing a synchronized population of IQ6011 L1 larvae grown in axenic mCeHR-2 liquid medium to varying concentrations of heme (2–20 μm) and measuring the resulting GFP fluorescence using the COPAS BIOSORT flow cytometer. GFP fluorescence was greatest when worms were grown at 2 μm heme and decreased as heme concentration increased; GFP was undetectable in worms grown at ≥16 μm heme (Fig. 1B), consistent with previous quantitative RT-PCR studies of hrg-1 mRNA (18).

FIGURE 1.

hrg-1 is transcriptionally up-regulated in low heme. A, IQ6011 worms were grown in mCeHR-2 medium supplemented with 4 μm heme for 48 h and then analyzed for GFP by fluorescence microscopy. Upper panel, GFP; lower panel, DIC. Scale bar = 100 μm. B, synchronized IQ6011 L1 larvae were grown in varying heme concentrations for 72 h in mCeHR-2 medium. GFP (arbitrary units) was quantified using the COPAS BIOSORT instrument. C, IQ6011 worms were grown at 4 μm heme for 48 h and then bleached to obtain embryos. Embryos at varying developmental stages were analyzed for fluorescence (GFP; lower panels) and DIC (upper panels). Scale bar = 20 μm.

To determine the developmental expression pattern of hrg-1, we examined GFP in developing embryos from IQ6011 by spinning disk confocal microscopy. Embryos isolated from adult worms grown on strain OP50 with no added heme expressed the hrg-1::gfp reporter in all somatic cells post-gastrulation (Fig. 1C, second panel; and supplemental Video 1). However, as the embryo entered the 100-cell stage, GFP was significantly enhanced in intestinal precursor cells (Fig. 1C, third panel) compared with the surrounding cell types. As the embryos matured, GFP expression was continually maintained in the presumptive intestinal cells but was undetectable in non-intestinal cells (Fig. 1C, right panels). Diminished GFP was observed when embryos were isolated from worms grown at 20 μm heme (data not shown). These results indicate that, although hrg-1 is initially expressed in all somatic cells of the C. elegans embryo, hrg-1 expression is greatly enhanced in early intestinal cells with either a concomitant loss of activation or active repression in non-intestinal cells.

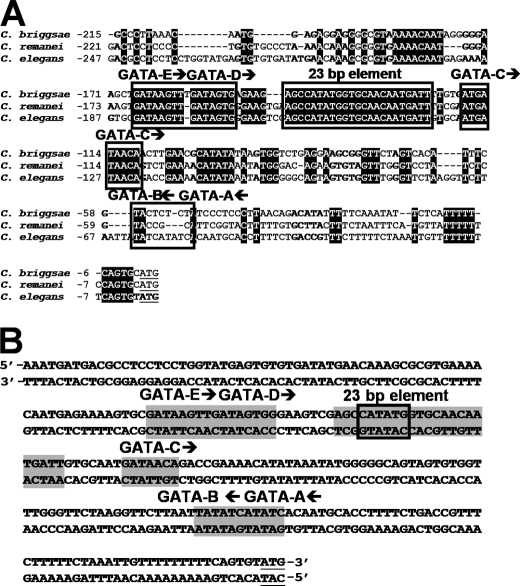

Analysis of the hrg-1 Promoter

Transcription of hrg-1 is initiated from three distinct transcriptional start sites, including a transcript that is trans-spliced to the SL1 leader sequence, as indicated by RACE (supplemental Fig. S1). This result is consistent with the modENCODE Database, which reveals that the shortest transcript, containing the SL1 splice site, is the most abundant. The open reading frame is identical in all three transcripts. To locate the elements that regulate transcription within the hrg-1 promoter, we aligned 3 kb of DNA sequence upstream of the ATG translation initiation codon of C. elegans hrg-1 with the corresponding sequences from C. briggsae and C. remanei (25). Significant sequence conservation was observed within 200 nucleotides immediately upstream of the ATG codon across all three Caenorhabditis species (Fig. 2A). Within the conserved nucleotides were five putative GATA sites, cis-acting DNA regulatory elements that interact with ELT-2, a transcription factor necessary for intestine-specific gene expression in C. elegans (26, 27). We designated these five sites as GATA-A to GATA-E, with GATA-A located closest to the ATG codon (Fig. 2B). GATA-A was absent in C. remanei; GATA-B was absent in both C. briggsae and C. remanei; and GATA-C, -D, and -E were conserved in other Caenorhabditis promoters (supplemental Fig. S2). In addition, an uninterrupted stretch of 23 nucleotides located between GATA-C and GATA-D was highly conserved in the hrg-1 promoters (Fig. 2, A and B). Within this 23 bp was a palindrome containing CATATG, a putative E-box sequence shown to bind the basic helix-loop-helix family of transcription factors (28). In agreement with the RACE data, an SL1 trans-splice region was also conserved across the Caenorhabditis species (29).

FIGURE 2.

The hrg-1 promoter contains conserved putative cis-acting DNA elements. A, ClustalW/Boxshade 3.2.1 alignment of the hrg-1 5′-flanking sequences of C. briggsae, C. remanei, and C. elegans. Reversed letters indicate conserved nucleotides. Boxes indicate putative regulatory elements. Arrows show the orientation of the GATA sites. The ATG start codon is underlined. B, diagram depicting the five putative GATA sites and the 23-bp element in the 5′-flanking region of hrg-1. Shaded letters indicate putative regulatory elements. The box indicates an E-box. Arrows show the orientation of the GATA sites. The ATG start codon is underlined.

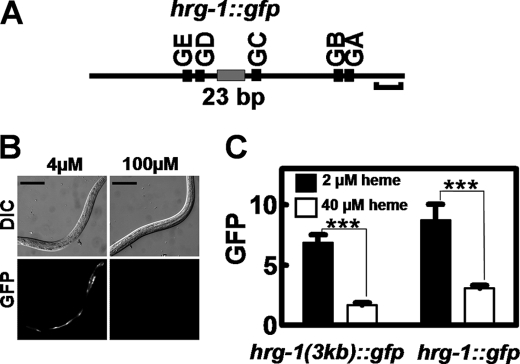

To investigate whether any of the conserved elements within the hrg-1 promoter responded to heme, we constructed a transcriptional GFP fusion with a 254-bp fragment that included all the GATA sites and the 23-bp element (Fig. 3A and Table 2). Transgenic worms transformed with hrg-1::gfp were placed in mCeHR-2 medium supplemented with either 4 or 100 μm heme. GFP was visible only in worms grown at 4 μm heme, indicating that the 254 bp of the hrg-1 promoter was sufficient for heme responsiveness (Fig. 3B). Quantification of GFP showed that the 254-bp DNA fragment responded to heme in a similar manner to the 3-kb fragment (Fig. 3C). Because both promoters displayed a robust heme response, we termed the 254-bp fragment the hrg-1 promoter.

FIGURE 3.

A 254-bp region within the hrg-1 promoter is sufficient for heme responsiveness. A, schematic diagram showing 254 bp of the hrg-1 5′-flanking sequence. GA–GE, GATA sites. Horizontal bracket = 20 bp. B, transgenic C. elegans strains carrying hrg-1::gfp were made axenic and simultaneously synchronized. L1 larvae were placed in either 4 or 100 μm heme for 72 h. Scale bars = 100 μm. GFP in the worms was analyzed by microscopy. Upper panels, DIC; lower panels, GFP. C, GFP was quantified in C. elegans transformed with hrg-1::gfp and supplemented 2 or 40 μm heme. The y axis is the GFP level in arbitrary units. ***, p < 0.001.

GATA and HERE Elements Function in a Concerted Manner for hrg-1 Expression

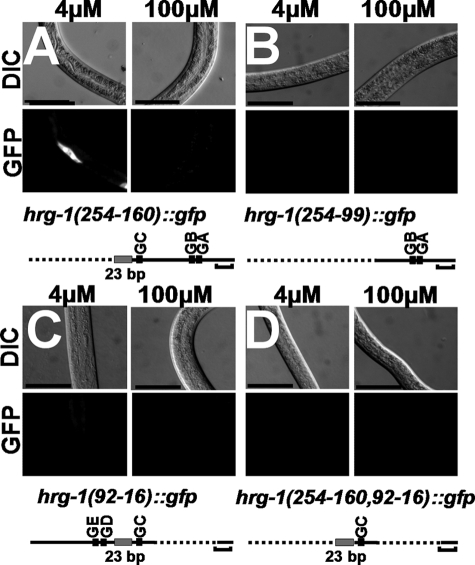

To further define the heme-responsive portion of the hrg-1 promoter, we constructed a series of mutants in which segments of the promoter had been systematically deleted (Table 2). The first deletion removed 95 nucleotides containing the GATA-D and GATA-E sites but retained the 23-bp element and the GATA-A, -B, and -C sites, which were proximal to the ATG codon. Transgenic worms transformed with the hrg-1(254–160)::gfp construct expressed GFP in a heme-dependent manner (Fig. 4A). The second deletion eliminated a highly conserved 60-bp portion of the promoter that included the 23-bp conserved sequence and GATA-C site. Worms transformed with the hrg-1(254–99)::gfp construct showed no detectable GFP expression at low and high heme (Fig. 4B), indicating that heme responsiveness was lost in this reporter.

FIGURE 4.

The HERE is within a 67-bp region. Deletion constructs (A–D) were synthesized to determine the specific region that contained the HERE. GATA sites (GA–GE) are shown by black boxes, and the 23-bp element is shown by a gray box. Horizontal brackets = 20 bp. For microscopy, GFP (lower panels) and DIC (upper panels) were analyzed in worms grown at 4 or 100 μm heme. Longer exposures of worms in C are shown in supplemental Fig. S3.

Because hrg-1(254–160)::gfp suggested that the sequence upstream of the 23-bp element was not essential for heme responsiveness (Fig. 4A), we investigated the region downstream of the 23-bp element. A third deletion construct, with sequence removed that included the GATA-A and GATA-B sites, was generated by deletion of a stretch of non-conserved bases between the 23-bp element and the ATG start codon (Fig. 4C). We retained the first 15 bp immediately upstream of the ATG codon because of the presence of a putative SL1 leader trans-splicing consensus sequence (supplemental Fig. S1) (30). Although transgenic worms transformed with the hrg-1(92–16)::gfp construct displayed heme responsiveness, the overall GFP level was severely reduced at 4 μm heme (Fig. 4C and supplemental Fig. S3). We next investigated whether the 23-bp element and its most proximal GATA-C site were responsible for the heme regulation by deleting the remaining GATA sites. Transgenic worms expressing the hrg-1(254–169,92–15)::gfp construct had no detectable GFP expression in the presence or absence of heme (Fig. 4D). Collectively, these results suggest that the 23-bp element located between −159 and −93 bp of the hrg-1 promoter is necessary for heme regulation and enhanced hrg-1 expression (Table 2). We therefore termed the 23-bp element the HERE. Furthermore, the HERE may have positional constraints within the promoter, and its relative proximity to specific GATA sites may direct the heme responsiveness of hrg-1.

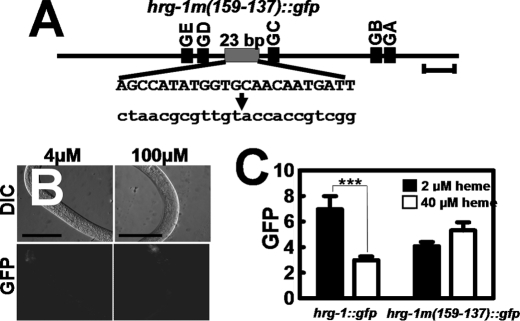

Characterization of the HERE of hrg-1

To corroborate the deletion analyses of the hrg-1 promoter, we performed site-directed mutagenesis to provide information about promoter functionality without altering the spatial constraints of cis-acting elements relative to each other. Worms transformed with hrg-1m(159–137)::gfp, in which the entire HERE was mutated, expressed low but discernable levels of GFP in the worm intestine irrespective of the heme concentrations (Fig. 5). This result implied that the HERE was necessary for directing the transcriptional regulation of hrg-1 by heme.

FIGURE 5.

Mutation of the 23-bp conserved element abolishes expression of hrg-1. A, schematic diagram of the wild-type 23-bp element and the corresponding mutation indicated in lowercase letters. GA–GE, GATA sites. B, transgenic C. elegans strains transformed with hrg-1m(159–137)::gfp were made axenic, and synchronized L1 larvae were placed in medium supplemented with either 4 or 100 μm heme for 72 h. GFP expression in the worms was analyzed by microscopy. Scale bars = 100 μm. C, quantification of GFP in C. elegans transformed with hrg-1m(159–137)::gfp and supplemented with 2 or 40 μm heme. The y axis is the GFP level in arbitrary units. ***, p < 0.001.

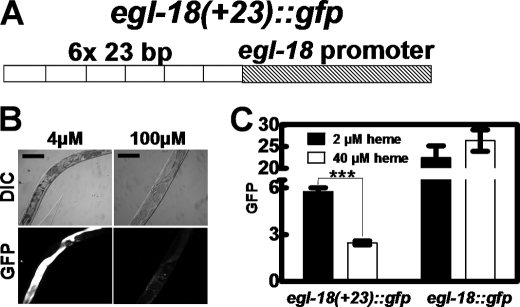

To determine whether the HERE was solely responsible for the heme responsiveness, we synthesized a construct in which the expression of GFP was driven by six tandem HEREs positioned upstream of the egl-18 basal promoter (Fig. 6A). Worms expressing the egl-18(+23)::gfp construct were transferred to mCeHR-2 liquid medium supplemented with either 2 or 40 μm heme. Only worms grown in 2 μm heme had detectable GFP expression, indicating that the HERE is sufficient to confer heme responsiveness to an ectopic promoter (Fig. 6B). Although control worms that expressed gfp from the egl-18 basal promoter showed significantly elevated GFP at both 2 and 40 μm heme, the presence of the concatamerized HEREs resulted in complete repression of GFP at 40 μm heme (Fig. 6C). To assess whether the concatamerized HEREs could recruit activators, we also used the myo-2 basal promoter. Transgenic worms generated by microinjection of the myo-2(+23)::gfp construct showed no GFP expression even though worms were maintained in low heme for two generations and for >120 h (supplemental Fig. S4). Together, these results strongly indicate that the HERE is both necessary and sufficient for the heme responsiveness of hrg-1 and may function as a repressor element (Figs. 5 and 6).

FIGURE 6.

The 23-bp element is sufficient for heme response. A, schematic diagram of a concatamer of six direct repeats of the 23-bp element fused to the egl-18 basal promoter. This chimeric promoter was placed upstream of gfp and the unc-54 3′ UTR. B, transgenic C. elegans strains expressing either egl-18::gfp or egl-18(+23)::gfp were placed in medium supplemented with either 4 or 100 μm heme for 120 h, and GFP expression in the worms was analyzed by microscopy. Scale bars = 100 μm. C, GFP was quantified in C. elegans transformed with egl-18::gfp or egl-18(+23)::gfp and supplemented with 2 or 40 μm heme. The y axis is the GFP level in arbitrary units. ***, p < 0.001.

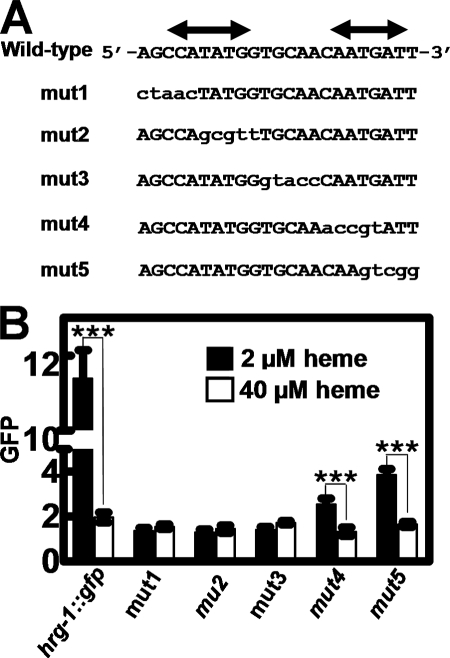

Our results with the developmental expression of hrg-1 and the HERE placed upstream of the egl-18 basal promoter implied that hrg-1 may be regulated by both activation and repression (Fig. 1C). Consistent with these possibilities, we found two inverted repeats within the HERE, reminiscent of a cis-element that may bind multiple trans-acting factors. To identify the specific nucleotides within the HERE that were required for function, we systematically mutated the 23 bases in blocks of five-nucleotide segments and termed these constructs mut1 through mut5 (Fig. 7A). Worms expressing mut1, mut2, and mut3 showed no GFP expression in either 2 or 40 μm heme, suggesting that these nucleotides were essential for the heme responsiveness of hrg-1. Transgenic worms expressing the mut4 and mut5 constructs showed significant heme responsiveness of GFP expression, albeit the overall magnitude of GFP expression was significantly lower compared with strains expressing the 254-bp hrg-1::gfp construct (Fig. 7 versus Fig. 3 and Table 2). These results indicate that, although the nucleotides mutated in mut4 and mut5 may not be necessary for the heme response of hrg-1, they are essential to maintain maximal hrg-1 expression under low heme conditions.

FIGURE 7.

Heme responsiveness in the hrg-1 promoter is mediated by a 15-bp region containing an E-box. A, schematics for the synthesis of mut1 to mut5 by mutating five consecutive nucleotides at a time within the 23-bp HERE. Double-headed arrows indicate the location of inverse repeats. B, GFP was quantified in C. elegans transformed with mut1, mut2, mut3, mut4, or mut5 and supplemented with 2 or 40 μm heme. The y axis is the GFP level in arbitrary units. ***, p < 0.001.

Intestinal Expression of hrg-1 Is Specified by ELT-2 and ELT-4

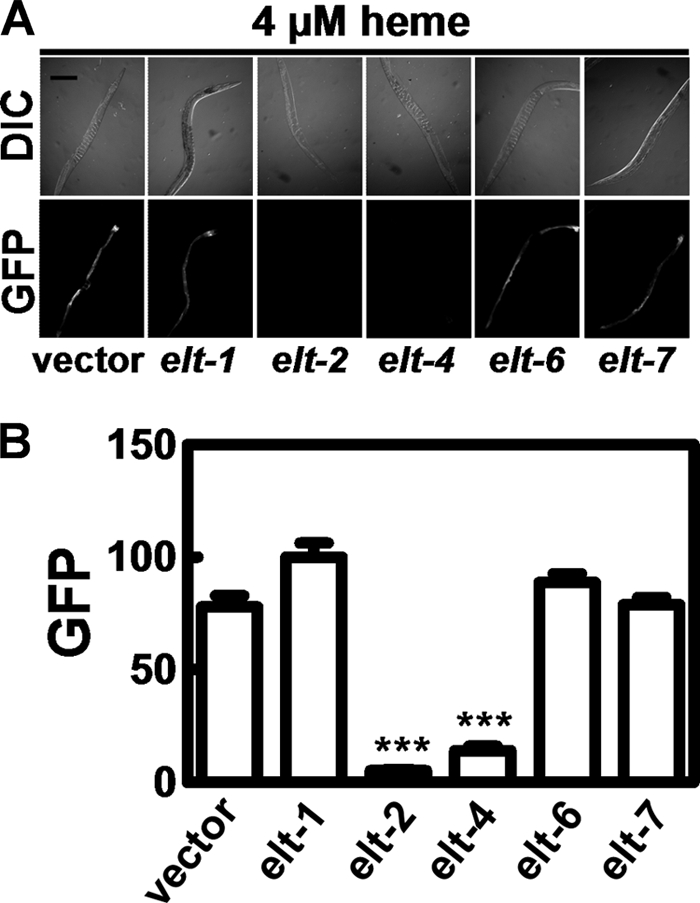

Because hrg-1 is specifically expressed in the C. elegans intestine and the promoter contains five putative GATA sites, we postulated that hrg-1 may be regulated by the GATA-binding transcription factors (27). To test this prediction, IQ6011 worms were exposed to RNA interference by feeding dsRNA produced in E. coli strain HT115(DE3) grown in 4 μm heme. Depletion of elt-2 and elt-4 resulted in loss of GFP expression (Fig. 8). However, knockdown of elt-1, elt-6, or elt-7, other GATA family transcription factors, did not diminish GFP expression at low heme (31, 32). These results indicate that the intestine-specific ELT-2 and ELT-4 transcription factors also determine the tissue-specific expression of hrg-1.

FIGURE 8.

ELT-2 and ELT-4 are essential for the heme regulation of hrg-1. A, synchronized IQ6011 L3 larvae were fed HT115(DE3) bacteria grown in 4 μm heme and induced to produce double-stranded RNA against elt-1, elt-2, elt-4, elt-6, or elt-7, and GFP was analyzed by microscopy. B, quantification of the GFP expression in A. The y axis is the GFP level in arbitrary units. ***, p < 0.001.

DISCUSSION

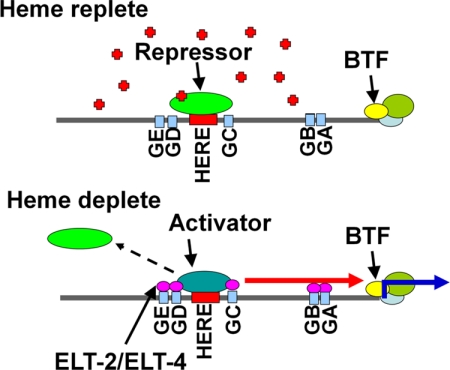

We have previously reported that heme transcriptionally regulates hrg-1 (18). However, the cis-acting target sequences responsible for this regulation have not been identified. Our results show that the 23 nucleotides that compose the HERE and multiple GATA sites work in concert to regulate the heme-dependent expression of hrg-1 in the C. elegans intestine (Fig. 9). We propose a model in which a repressor(s) binds the HERE in the presence of high heme to down-regulate hrg-1 expression. When heme levels are low, hrg-1 is derepressed due to either dissociation of the repressor from the HERE or displacement of the repressor by an enhancer or activator protein.

FIGURE 9.

Proposed model of hrg-1 regulation by heme. Under heme-replete conditions, a repressor binds the 23-bp HERE, and hrg-1 expression is suppressed. In heme-depleted conditions, an enhancer may compete with the repressor for binding the HERE, resulting in the recruitment of ELT-2 and/or ELT-4 to activate transcription of hrg-1. BTF, basal transcription factors; GA–GE, GATA elements; red arrow, enhancement and possible interaction with GATA-binding factors; blue arrow, transcription; red plus signs, heme.

We speculate that the heme regulation of hrg-1 is synergistic with the binding of the intestine-specific transcription factor ELT-2 and/or ELT-4 to GATA sites. A regulatory pathway in which GATA sites work cooperatively with other factors appears to be a general form of regulation in C. elegans. In C. elegans, ELT-2, ELT-4, and ELT-7 are all intestine-specific. However, elt-4 and elt-7 deletion mutants in C. elegans show a wild-type phenotype, indicating that ELT-2 is the major GATA factor in the intestine (27, 33). ELT-2 controls expression of numerous intestinal genes. However, specific control of intestinal gene expression under different developmental or environmental conditions could be achieved through the orchestrated recruitment and interaction with distinct enhancers, repressors, or modifiers (34). For example, the C. elegans ferritin (ftn-1) promoter is up-regulated in the intestine under high iron conditions by ELT-2 and an unidentified enhancer (35).

Although there are five putative GATA-binding elements in the hrg-1 promoter, they may not all be functionally equivalent in hrg-1 regulation. Other genes, such as pho-1 and ges-1, also have multiple GATA sites, but only one particular GATA site, with the sequence ACTGATAA, is important for the expression of either gene (36). In the hrg-1 promoter, the closest resemblance to the pho-1/ges-1 GATA site is GATA-C (AATGATAA). The lack of a perfect GATA site may explain why hrg-1 is not expressed at high levels when the 23-bp element is mutated. The imperfect GATA sites in the hrg-1 promoter may permit another tier of hrg-1 regulation by requiring additional trans-acting factors, possibly ELT-2/ELT-4-binding partners.

The regulatory elements of the hrg-1 promoter are conserved in Caenorhabditis species (supplemental Fig. S2). These species are bacteriovorous heme auxotrophs that reside in the soil, where bioavailable heme may be limiting. Because heme is critical for larval survival and embryonic development, it is not surprising that the regulatory pathways necessary for heme utilization are also conserved. Many parasitic nematodes are also heme auxotrophs, raising the possibility that helminths may share similar heme regulatory mechanisms with free-living nematodes (17). If hrg homologs in parasitic helminths are regulated in a similar manner to hrg genes in C. elegans, our studies in C. elegans could be used to establish a conceptual framework for how nematodes forage and ingest dietary heme for growth and reproduction, aiding in the development of anthelminthics to combat worm infections.

In this study, we have shown that the 23-bp HERE controls heme response in the hrg-1 promoter. Within these 23 bp is a canonical E-box (CATATG), an element to which basic helix-loop-helix transcription factors bind. In silico analysis of the C. elegans databases identified two additional heme-responsive genes, mrp-5 and C15C8.3, which share an identical conserved E-box to hrg-1 in the 5′-flanking region (supplemental Fig. S5). Additionally, in all three genes, the E-box is flanked by a GATA site, supporting our hypothesis that the HERE and GATA sites function cooperatively in the C. elegans intestine. Plausibly, variations in the HERE outside the E-box may permit the selective recruitment of gene-specific trans-acting complexes to control the magnitude of heme-dependent transcriptional response in these genes. Identification of the transcription factors that regulate heme-responsive genes may provide a more comprehensive analysis of how nutrients regulate gene expression, a well established model in Saccharomyces cerevisiae (21, 37).

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Abbhi Rajagopal for the RACE experiments, Kevin O'Connell for help with the spinning disk confocal microscopy, and Mike Krause for critical reading of the manuscript.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grant R01 DK74797 (to I. H.).

The on-line version of this article (available at http://www.jbc.org) contains supplemental Figs. S1–S5 and Video 1.

- HERE

- heme-responsive element

- DIC

- differential interference contrast

- RACE

- 5′-rapid amplification of cDNA ends.

REFERENCES

- 1.Ajioka R. S., Phillips J. D., Kushner J. P. (2006) Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1763, 723–736 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Nakajima O., Takahashi S., Harigae H., Furuyama K., Hayashi N., Sassa S., Yamamoto M. (1999) EMBO J. 18, 6282–6289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rodgers K. R. (1999) Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 3, 158–167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wenger R. H. (2000) J. Exp. Biol. 203, 1253–1263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gilles-Gonzalez M. A., Gonzalez G. (2004) J. Appl. Physiol. 96, 774–783 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oyake T., Itoh K., Motohashi H., Hayashi N., Hoshino H., Nishizawa M., Yamamoto M., Igarashi K. (1996) Mol. Cell. Biol. 16, 6083–6095 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hintze K. J., Katoh Y., Igarashi K., Theil E. C. (2007) J. Biol. Chem. 282, 34365–34371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sun J., Hoshino H., Takaku K., Nakajima O., Muto A., Suzuki H., Tashiro S., Takahashi S., Shibahara S., Alam J., Taketo M. M., Yamamoto M., Igarashi K. (2002) EMBO J. 21, 5216–5224 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tahara T., Sun J., Igarashi K., Taketani S. (2004) Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 324, 77–85 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tahara T., Sun J., Nakanishi K., Yamamoto M., Mori H., Saito T., Fujita H., Igarashi K., Taketani S. (2004) J. Biol. Chem. 279, 5480–5487 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Severance S., Hamza I. (2009) Chem. Rev. 109, 4596–4616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zenke-Kawasaki Y., Dohi Y., Katoh Y., Ikura T., Ikura M., Asahara T., Tokunaga F., Iwai K., Igarashi K. (2007) Mol. Cell. Biol. 27, 6962–6971 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yin L., Wu N., Curtin J. C., Qatanani M., Szwergold N. R., Reid R. A., Waitt G. M., Parks D. J., Pearce K. H., Wisely G. B., Lazar M. A. (2007) Science 318, 1786–1789 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kaasik K., Lee C. C. (2004) Nature 430, 467–471 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rudic R. D., McNamara P., Curtis A. M., Boston R. C., Panda S., Hogenesch J. B., Fitzgerald G. A. (2004) PLoS Biol. 2, e377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Severance S., Rajagopal A., Rao A. U., Cerqueira G. C., Mitreva M., El-Sayed N. M., Krause M., Hamza I. (2010) PLoS Genet. 6, e1001044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rao A. U., Carta L. K., Lesuisse E., Hamza I. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 4270–4275 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rajagopal A., Rao A. U., Amigo J., Tian M., Upadhyay S. K., Hall C., Uhm S., Mathew M. K., Fleming M. D., Paw B. H., Krause M., Hamza I. (2008) Nature 453, 1127–1131 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brenner S. (1974) Genetics 77, 71–94 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nass R., Hamza I. (2007) Curr. Protoc. Toxicol. Unit 1.9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Philpott C. C., Protchenko O. (2008) Eukaryot. Cell 7, 20–27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aiyar A., Xiang Y., Leis J. (1996) Methods Mol. Biol. 57, 177–191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ishii T. M., Zerr P., Xia X. M., Bond C. T., Maylie J., Adelman J. P. (1998) Methods Enzymol. 293, 53–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kamath R. S., Ahringer J. (2003) Methods 30, 313–321 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Larkin M. A., Blackshields G., Brown N. P., Chenna R., McGettigan P. A., McWilliam H., Valentin F., Wallace I. M., Wilm A., Lopez R., Thompson J. D., Gibson T. J., Higgins D. G. (2007) Bioinformatics 23, 2947–2948 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hawkins M. G., McGhee J. D. (1995) J. Biol. Chem. 270, 14666–14671 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McGhee J. D., Sleumer M. C., Bilenky M., Wong K., McKay S. J., Goszczynski B., Tian H., Krich N. D., Khattra J., Holt R. A., Baillie D. L., Kohara Y., Marra M. A., Jones S. J., Moerman D. G., Robertson A. G. (2007) Dev. Biol. 302, 627–645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Metz R., Ziff E. (1991) Oncogene 6, 2165–2178 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Williams C., Xu L., Blumenthal T. (1999) Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 376–383 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Blumenthal T. (2005) WormBook, 1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spieth J., Shim Y. H., Lea K., Conrad R., Blumenthal T. (1991) Mol. Cell. Biol. 11, 4651–4659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Koh K., Rothman J. H. (2001) Development 128, 2867–2880 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fukushige T., Goszczynski B., Tian H., McGhee J. D. (2003) Genetics 165, 575–588 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McGhee J. D. (2007) WormBook, 1–36 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Romney S. J., Thacker C., Leibold E. A. (2008) J. Biol. Chem. 283, 716–725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Fukushige T., Goszczynski B., Yan J., McGhee J. D. (2005) Dev. Biol. 279, 446–461 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Rees E. M., Thiele D. J. (2004) Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 7, 175–184 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.