Abstract

Troponin is a pivotal regulatory protein that binds Ca2+ reversibly to act as the muscle contraction on-off switch. To understand troponin function, the dynamic behavior of the Ca2+-saturated cardiac troponin core domain was mapped in detail at 10 °C, using H/D exchange-mass spectrometry. The low temperature conditions of the present study greatly enhanced the dynamic map compared with previous work. Approximately 70% of assessable peptide bond hydrogens were protected from exchange sufficiently for dynamic measurement. This allowed the first characterization by this method of many regions of regulatory importance. Most of the TnI COOH terminus was protected from H/D exchange, implying an intrinsically folded structure. This region is critical to the troponin inhibitory function and has been implicated in thin filament activation. Other new findings include unprotected behavior, suggesting high mobility, for the residues linking the two domains of TnC, as well as for the inhibitory peptide residues preceding the TnI switch helix. These data indicate that, in solution, the regulatory subdomain of cardiac troponin is mobile relative to the remainder of troponin. Relatively dynamic properties were observed for the interacting TnI switch helix and TnC NH2-domain, contrasting with stable, highly protected properties for the interacting TnI helix 1 and TnC COOH-domain. Overall, exchange protection via protein folding was relatively weak or for a majority of peptide bond hydrogens. Several regions of TnT and TnI were unfolded even at low temperature, suggesting intrinsic disorder. Finally, change in temperature prominently altered local folding stability, suggesting that troponin is an unusually mobile protein under physiological conditions.

Keywords: Actin, Calcium-binding Proteins, Cardiac Muscle, Protein Folding, Protein Stability, H/D Exchange, Muscle, Protein Dynamics, Regulation, Troponin

Introduction

Cardiac and skeletal muscle contraction are reversibly activated and strictly controlled by Ca2+ binding to the thin filament protein troponin (reviewed in Refs. 1–4). Troponin works in concert with the coiled-coil protein tropomyosin to shut off muscle contraction via partially understood alterations of thin filament structure and function (5–12). Ca2+ binding to the troponin (Tn)2 subunit TnC abolishes this inhibition and allows muscle contraction to occur. Because troponin is the most direct site of a very profound regulatory mechanism, investigators have pursued detailed study of its properties. Recently, we reported the first application to this subject of an approach that provides a striking wealth of dynamic information: hydrogen/deuterium exchange-mass spectrometry (13–17).

Exposed peptide bond hydrogens exchange readily with solvent molecules (18). That is, the NH group hydrogens exchange with H if the solvent is water, and exchange with D if the solvent is D2O. This exchange is blocked, however, by the hydrogen bonds formed by most backbone amides in folded proteins. Consequently, amide hydrogens are protected from exchange (i.e. the exchange rates are slowed) to an extent generally determined by local folding stability and flexibility. By characterizing H to D exchange rates at multiple sites, either by NMR or by mass spectrometry, one can map the wide variation in local dynamics that occur across different regions of a native state protein. Furthermore, by measuring the effects on H/D exchange rates of local or thermodynamic perturbations, intramolecular signal transduction and other properties can be revealed in considerable detail.

In a recent study (19) H/D exchange rates at 25 °C were determined for cardiac troponin in the presence of either high or subsaturating Ca2+ concentrations. Portions of the TnT-TnI coiled-coil underwent limited H/D exchange despite 6 h in D2O, indicating high stability for this region of troponin. Partial de-saturation of the TnC regulatory Ca2+ binding site altered dynamic properties locally and also altered the dynamic properties of other parts of troponin that were remote from this Ca2+ site.

More generally, the results revealed troponin to be broadly dynamic, with 60% of amides exchanging within seconds. In fact, 50% of the amide hydrogens exchanged before the first, 5 s time point. It could not be determined if this indicated weak local folding or more marked disorder. An additional 10% of H exchanged with fast rates that were at the limits of detectability, so that transition sizes were difficult to measure. This allowed only rough delineation of regions where weak folding was detected by weak protection from exchange. As described below, many of these regions are of regulatory significance. Therefore, the failure of the previous study to determine their dynamic properties was a significant omission. Overall, characterization of more than half of the molecule was limited by fast rates of exchange.

In the present study, mass spectrometry was used to map amide hydrogen exchange in the human cardiac troponin core domain (TnC/TnI/TnT183–288), under lower temperature conditions. Protein exchange rates usually decrease with decreasing temperature, for two reasons. The intrinsic, unprotected exchange rate is lower. For example, it is 4.7-fold less at 10 °C compared with 25 °C (18). Also, both local and global folding are equilibrium processes affected by temperature. Protein folding thermodynamics, in other words, tend to cause a greater protection from H/D exchange at low temperature than at higher temperature (20, 21). For troponin, the present results show that decreasing the temperature to 10 °C greatly increased the ability to measure exchange rates. The dynamic properties of about 70% of troponin were measurable, yielding new insights into troponin structure and function. For example, the TnI COOH terminus was protected from H/D exchange, implying an intrinsically folded structure for this region that is central to muscle relaxation. Also, unprotected, apparently unfolded residues link the TnI switch helix-TnC N-domain region to the remainder of troponin. These and many other findings are detailed below.

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Protein Preparation, Protein Fragment Generation, and Protein Fragment Identification

Human cardiac troponin core domain was prepared as previously described (19). In brief, bacterially expressed TnI, TnC, and COOH-terminal TnT fragment 183–288 were mixed and then reconstituted into a ternary complex by serial dialysis. The complex was isolated by ion exchange chromatography and stored at −80 °C before use.

To identify troponin fragments that could be examined for H/D exchange, troponin was digested with pepsin, and tandem mass spectrometry was performed using a Finnigan FT-ICRMS (Thermoelectron). Peptic fragments were identified using the search algorithm Bioworks 3.2 (Thermoelectron) and manual confirmation. The fragments are the same as those described previously (19), with the addition of TnC fragment 48–56.

H/D Exchange of Troponin

Exchange was performed as described previously (19), except for the selected temperature. That is, ∼5 μg of 10 °C troponin in 10 mm NaHPO4 (pH 7.1), 0.1 m NaCl was diluted to 6 μm by manual mixing with 9 parts by volume of 10 °C D2O buffer (10 mm NaDPO4 (pD read 7.1), 0.1 m NaCl, 1 mm CaCl2). Exchange was acid quenched after different time intervals at this temperature, beginning 5 s after mixing the protein with D2O. In a previous study, conducted at 25 °C, exchange was examined after as long as 6 h. Longer incubations were avoided, because precipitate appeared. In the present study, conducted at 10 °C, the troponin was more stable. Accordingly, exchange was examined after periods extending to 48 h. Regardless of time interval, acid-quenched samples were flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Samples were stored at −80 °C.

Analysis of H/D Exchange by HPLC-Electrospray Ionization FT-ICR MS

For analysis, quickly thawed samples were digested with pepsin and immediately injected into a micropeptide trap, which was attached to a C18 HPLC column, which was connected to the FT-MS (19). Peptide envelopes were easily recognizable by correspondence to the possible post-exchange m/z of pre-H/D-identified peptides. The centroid mass of each peptide was determined using MagTran (22).

Appropriate corrections for backward D/H exchange were measured as described (19) by analysis of troponin that was fully exchanged. Specifically, troponin was incubated for 2 h at 40 °C in 2 m deuterated urea, 100 mm NaDPO4 (pD 2.5). This sample was digested with pepsin, and peptide masses were measured. Compared with un-deuterated fragments, the masses increased by an average of 77% of the amount expected based on the number of exchangeable NH hydrogens. This corresponds to an average back exchange of 23%. Corrections were employed peptide by peptide, rather than by this average. The accuracy of this approach was assessed as described in the text.

Curve Fitting of Exchange Kinetic Data

Transition sizes and rate constants were determined by non-linear least squares curve-fitting of exponential peptide mass increases over time, using Scientist (Micromath). These parameter and error estimate determinations were performed either simply on individual peptide data, or globally on grouped data from peptides wherever there was peptide overlap (19). The globally fit groups of peptides were: TnC [28–57, 36–56, 48–56] and [118–132, 122–130, 122–132]; TnI [27–53, 29–49, 29–53], [54–66, 54–78, 62–85, 78–88], [97–109, 97–116], [125–134, 125–152], [156–169, 162–169], and [191–197, 191–210]; TnT [224–242/225–243 (which are effectively indistinguishable after exchange), 230–243, 237–243] and [243–263/244–263 (which are effectively indistinguishable after exchange), 244–250, 249–263, 251–263], where peptide groups are enclosed in brackets.

Primary Structure Mapping of H/D Exchange Rates

The curve fitting described above identified H/D exchange transitions of measured magnitudes. For many transitions, the rates as well as the magnitudes were measureable. They are listed in Table 1. Other transitions were simply categorized as faster than 5 s or slower than 48 h. Overall, transition magnitudes averaged 4.9 hydrogens (or 4.5 hydrogens if peptides comprising the long NH2 and COOH termini of the TnT construct were each excluded.)

TABLE 1.

H-D exchange rates and assignments

| Subunit | Peptide or group of peptides | Assignable region | Assignment | H-D exchange rate h −1 | Log (protection factor) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TnC | 1–12 | 2–12 | 5–6 | 2.5 ± 1.6 | 2.97 |

| 1–12 | 2–12 | 8–12 | 24 ± 8 | 1.99 | |

| 13–24 | 14–24 | 16–17 | 3.0 ± 1.3 | 3.16 | |

| 13–24 | 14–24 | 18–22 | 0.024 ± 0.005 | 5.27 | |

| 28–57 | 29–36 | 29–31 | 82 ± 44 | 1.73 | |

| 28–57 | 29–36 | 32–36 | 0.14 ± 0.04 | 4.50 | |

| 28–57 | 37–48 | 40–44 | 317 ± 174 | 1.13 | |

| 28–57 | 49–56 | 50–56 | 0.61 ± 0.14 | 3.38 | |

| 64–74 | 65–74 | 70–71 | 29 ± 20 | 2.11 | |

| 64–74 | 65–74 | 72–74 | 0.012 ± 0.006 | 5.50 | |

| 82–97 | 83–97 | 90–95 | 105 ± 54 | 1.71 | |

| 118–132 | 119–122 | 119–122 | 0.60 ± 0.17 | 3.59 | |

| 118–132 | 123–130 | 128–130 | 30 ± 7 | 2.13 | |

| 136–150 | 137–150 | 146–150 | 0.013 ± 0.004 | 5.60 | |

| 154–161 | 155–161 | 158–159 | 0.81 ± 0.35 | 3.31 | |

| TnI | 27–53 | 30–49 | 38–44 | 62 ± 27 | 2.01 |

| 54–88 | 55–66 | 55–58 | 0.044 ± 0.012 | 4.80 | |

| 54–88 | 55–66 | 59–62 | 93 ± 25 | 1.47 | |

| 54–88 | 67–78 | 67–68 | 62 ± 31 | 1.96 | |

| 54–88 | 67–78 | 77–78 | 0.07 ± 0.03 | 4.88 | |

| 54–88 | 79–85 | 83–85 | 31 ± 10 | 2.15 | |

| 91–96 | 92–96 | 92–92 | 4.3 ± 1.5 | 2.66 | |

| 91–96 | 92–96 | 93–96 | 0.016 ± 0.001 | 5.09 | |

| 97–116 | 98–109 | 98–104 | 0.015 ± 0.004 | 5.46 | |

| 97–116 | 110–116 | 112–116 | 0.015 ± 0.007 | 5.16 | |

| 117–124 | 118–124 | 118–120 | 0.010 ± 0.004 | 5.58 | |

| 117–124 | 118–124 | 121–124 | 525 | 0.86 | |

| 125–152 | 126–134 | 126–131 | 0.004 ± 0.003 | 5.83 | |

| 125–152 | 126–134 | 132–134 | 0.90 ± 0.44 | 3.51 | |

| 125–152 | 135–152 | 135–137 | 0.05 ± 0.02 | 4.95 | |

| 125–152 | 135–152 | 148–152 | 70 ± 24 | 1.79 | |

| 156–169 | 157–162 | 157–158 | 72 ± 50 | 1.73 | |

| 156–169 | 157–162 | 159–160 | 3.3 ± 1.7 | 3.07 | |

| 170–190 | 171–190 | 171–176 | 0.037 ± 0.008 | 5.07 | |

| 170–190 | 171–190 | 177–185 | 150 ± 33 | 1.46 | |

| 191–210 | 192–197 | 196–197 | 306 ± 40 | 1.19 | |

| 191–210 | 198–210 | 198–207 | 306 ± 40 | 1.13 | |

| 191–210 | 198–210 | 208–210 | 0.038 ± 0.009 | 5.04 | |

| TnT | 188–224 | 189–224 | 209–214 | 55.46 ± 20.29 | 1.92 |

A principal value of H/D exchange studies is that they provide mapped local information within a protein. Transitions are located within spans of the peptides in which they are detected (or within subpeptide spans when overlapping peptides are studied). These spans represent assignable regions for the transitions, and are listed in Table 2. They averaged ∼10 or 9 hydrogens in length, depending upon inclusion or exclusion of the two TnT peptides mentioned above.

TABLE 2.

Assignable regions for exchange transitions

| Subunit | Peptide or group of peptides | Assignable region | No. NHs |

|---|---|---|---|

| TnC | 1–12 | 2–12 | 11 |

| TnC | 13–24 | 14–24 | 11 |

| TnC | 28–57 | 29–36 | 8 |

| TnC | 28–57 | 37–48 | 12 |

| TnC | 28–57 | 49–56 | 6 |

| TnC | 64–74 | 65–74 | 10 |

| TnC | 82–97 | 83–97 | 15 |

| TnC | 101–110 | 102–110 | 9 |

| TnC | 118–132 | 119–122 | 4 |

| TnC | 118–132 | 123–130 | 8 |

| TnC | 136–150 | 137–150 | 14 |

| TnC | 154–161 | 155–161 | 7 |

| Tnl | 27–53 | 28–29 | 2 |

| Tnl | 27–53 | 30–49 | 19 |

| Tnl | 27–53 | 50–53 | 4 |

| Tnl | 54–88 | 55–66 | 12 |

| Tnl | 54–88 | 67–78 | 12 |

| Tnl | 54–88 | 79–85 | 6 |

| Tnl | 54–88 | 86–88 | 3 |

| Tnl | 91–96 | 92–96 | 5 |

| Tnl | 97–116 | 98–109 | 10 |

| Tnl | 97–116 | 110–116 | 7 |

| Tnl | 117–124 | 118–124 | 7 |

| Tnl | 125–152 | 126–134 | 9 |

| Tnl | 125–152 | 135–152 | 17 |

| Tnl | 156–169 | 157–162 | 6 |

| Tnl | 156–169 | 163–169 | 7 |

| Tnl | 170–190 | 171–190 | 20 |

| Tnl | 191–210 | 192–197 | 6 |

| Tnl | 191–210 | 198–210 | 13 |

| TnT | 182–187 | 183–187 | 5 |

| TnT | 188–224 | 189–224 | 36 |

| TnT | 224–243 | 225–229 | 5 |

| TnT | 224–243 | 230–236 | 7 |

| TnT | 224–243 | 237–243 | 7 |

| TnT | 243–264 | 244–250 | 7 |

| TnT | 243–264 | 251–264 | 14 |

| TnT | 263–288 | 264–288 | 25 |

| No. NHs | Average | 10.2 | |

| Exclude two TnT outliers | Average | 9.0 | |

| Exclude two TnT outliers | Std dev | 4.4 | |

From the data above, transition magnitudes averaged half the length of the assignable regions in which they were detected. Correspondingly, most assignable regions contained more than one exchange transition. From H/D exchange data alone there was no way to determine the relative locations of one transition compared with another transition within an assignable region. This produced a roughly 5-residue uncertainty in localization of the observed dynamic behavior. However, this overstates the error in localization, because other data were available to create a rationalized model. The different transitions were ordered within an assignable region to correspond with the troponin high resolution structural data (23). Thus, faster exchange was assigned where crystallographic B-factors were higher, or where no structure was detected by crystallography. These criteria generally provided an unambiguous implication for the model. In a few cases, it was necessary to resort to lesser criteria: slower exchange toward the center of a helix, or assignments to match rates in immediately adjoining peptides.

Calculation of Protection Factors

Measured exchange rates (kex) were converted to protection factors, which indicate the degree of H/D exchange slowing relative to rates expected if troponin were unfolded. These protection factors, Kcl, have conceptual value. They can be considered to represent local folding stability, measured in the context of the globally folded troponin molecule. Exchange rates were used to calculate protection factors via the expression Kcl = kchem/kex. In this equation, kchem is the unprotected H/D exchange rate determined from model peptide data (18) for the region within which the kinetic transition was detected. More specifically, kchem was calculated as the geometric mean of the model peptide unprotected H/D exchange rates (18) for each residue in the assignable region. Values for kchem ranged from 0.4 to 1.8 s−1. Because this is a narrow range relative to the much wider variation in kex, the maps in Figs. 5 and 6 would be altered little if exchange rate values were mapped instead of protection factors.

FIGURE 5.

Primary sequence map of troponin dynamics. Color-coded summary of all of the results in the present study, using a logarithmic scale to convey the wide range of dynamic behavior is shown. Unprotected regions are shown in red. Regions that took longer than 2 days to undergo H/D exchange are shown in violet. Green line segments indicate the assignable regions for the various transitions. See text.

FIGURE 6.

Troponin dynamic behavior mapped onto the troponin structure. The linear map from Fig. 5 was applied to the high resolution structure of troponin (23), using the molecular graphic program Pymol. Panels A and B show either cartoon-ribbon or dots representations of troponin, respectively. Their orientation is the same as shown in Fig. 1. Panel C shows a different orientation, and is zoomed-in relative to the other panels. TnC is shown in dots format, and the other subunits are shown in cartoon-ribbon format.

RESULTS

Kinetics of H/D Exchange in TnC

H/D exchange kinetic data were acquired for 13 TnC peptides, obtained following exposure of the ternary troponin complex to D2O at 10 °C. Data points and best fit kinetic curves for most of these peptides are shown in Fig. 1. The figure also includes thumbnail representations of the troponin structure, with the different locations of the peptides indicated in black space-filling mode. Dashed lines indicate 100% exchange.

FIGURE 1.

Kinetics of H/D exchange in troponin. TnC peptides are shown. TnC peptide mass increases were determined after exposure of troponin to D2O at 10 °C for times between 5 s and 48 h. Data points are shown, as well as best fit kinetic curves. Dashed lines indicate 100% exchange. Thin lines show representative, previously published patterns for several peptides at 25 °C. In the thumbnail images of troponin, the locations of graphed peptides are indicated as black space-filling sections.

In general, exchange was both slower and less complete at 10 °C (thick lines and data points) than previously reported at 25 °C (thin lines with data points omitted). To some extent this is because the lower temperature decreased the intrinsic exchange rate in the absence of protection (kchem) by 4.6-fold. This corresponds to about 2/3 of a unit shift on the semi-log graph abscissas. The observed changes in most transitions were greater than a 4.6-fold shift, however. Thus, temperature affected the troponin. A beneficial consequence of these dual effects was that many transitions that were too early to fully measure at 25 °C were much more effectively assessed at 10 °C. For example, Fig. 1 shows that the lower temperature was necessary for proper measurement of both transition sizes and transition rates for the N-helix (peptide 1–12), Ca2+ site II (peptide 64–74), and the D/E helix (peptide 82–97).

Unprotected H/D exchange rates (kchem) under Fig. 1 conditions are about 1 s−1, which would produce complete exchange for unprotected hydrogens by the first, 5 s time point. Regions exchanging in less than 5 s have undetectable levels of protection. This includes sites that are completely unprotected and exchange at ∼1 s−1, as well as sites with minimal local folding (protection factors less than about 8). No protection was detected for about one third of the exchangeable hydrogens for each troponin subunit, under 10 °C conditions (Table 3). Within TnC, regions with this highly dynamic behavior were found widely: within the NH2-domain, the COOH-domain, and residues between. For the most part, such regions are likely to be unfolded at physiological temperature, unless stabilized by some other target protein of the thin filament.

TABLE 3.

H-D exchange summary statistics

| TnC | Tnl | TnT | All | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. Peptide NH in troponin construct | 158 | 202 | 106 | 466 |

| No. Peptide NH in assessed peptides | 115 | 167 | 105 | 387 |

| Fractional assessment of troponin core domain | 0.73 | 0.83 | 0.99 | 0.83 |

| Unassessed fraction of troponin core domain | 0.27 | 0.17 | 0.01 | 0.17 |

| No. NH assessed as unprotected | 41 | 45 | 41 | 127 |

| Unprotected fraction of assessed NHS | 0.36 | 0.27 | 0.39 | 0.33 |

| Unprotected fraction in previous study at 25 ° C | 0.50 | 0.52 | 0.45 | 0.50 |

| No. NH with measured HDX rates | 55 | 97 | 16 | 168 |

| Fraction of assessed NHs with measured rates | 0.48 | 0.58 | 0.15 | 0.43 |

| Fraction with measured rates in previous study at 25 °C | 0.46 | 0.41 | 0.33 | 0.40 |

| No. NH assessed as highly protected | 19 | 25 | 48 | 92 |

| Highly protected fraction of assessed NHs | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.46 | 0.24 |

| Highly protected fraction in previous study at 25 °C | 0.04 | 0.08 | 0.22 | 0.10 |

The measurable transitions quantify wide variation in local dynamics. From peptide to peptide across the three troponin subunits, the measured rates varied by 5 orders of magnitude (Table 1). TnC helix A (in peptide 13–24), residues between helices B and C (in peptide 48–56), helix F (residues 119–122 within overlapping peptides), and helix H (in peptide 154–161) all underwent slow exchange requiring many hours, or much longer. These regions have high local stability. In contrast, the N-helix (1–12) is much more dynamic, as are most of the residues in peptides 64–74 and 136–150. Overall, the results show that both NH2- and COOH-domains of TnC have many mobile components, but they also include components that are highly stabilizing. As shown below, some of the relatively stable portions of the TnC COOH-domain interact with the other subunits.

Finally, one of the peptides shown in Fig. 1 merits particular mention. Of the 15 exchangeable hydrogens in the TnC peptide 82–97 that links TnC two domains, 8 exchanged by 5 s, and 4 others were weakly protected so that exchange occurred within 2 min. Thus, the D/E linker region between the domains of TnC is not a continuous helix. Rather, it is a highly mobile region, even at 10 °C. This has significance for the Ca2+-mediated regulatory mechanism (see “Discussion”).

Identification of Highly Protected Regions that Required Longer Than 48 h to Undergo H/D Exchange

None of the peptides in Fig. 1 reached the dashed line 100% exchange level after 48 h, including those peptides (e.g. 28–57) for which exchange had reached a plateau. This pattern contrasts with results at 25 °C, where exchange reached the dashed line in most cases. This aspect of the 10 °C data suggests that some hydrogens in many of the peptides were very highly protected, and exchanged on even longer time scales. However, this conclusion depends on the precision of a particular correction. The mass change values were corrected by estimates, made for each peptide, of the extent of back-exchange (D to H) occurring during processing and mass spectrometry. Corrections averaged 23%, and were obtained by performing complete H/D exchange in the presence of urea (19). The graphed mass change values, and therefore the deviations of these values at late time points from the dashed lines, depend on the validity of these back exchange corrections.

To assess this, observed plateaus were compared with 100% exchange values for measurements obtained at both lower and higher temperature (Fig. 2). The dashed line is that of identity. With a few exceptions, most of the 25 °C measurements (open squares) were narrowly scattered above and below this line. Excluding outliers, these 25 °C data from our previous study (19) fell along the dashed line, ± 0.95 Da S.D. In contrast, results obtained at 10 °C (filled circles) tended to fall below the line, consistent with qualitative examination of Fig. 1. Thus, at 10 °C more hydrogens appeared to be un-exchanged at the end of the experiment. In fact, many of the 10 °C plateaus fell short of the dashed line by more than 1.9 Da (i.e. more than 2 S.D.).

FIGURE 2.

Patterns of H/D exchange completion after long time intervals. Maximum H/D exchange values are shown for those TnC, TnI, or TnT peptides that reached a mass increase plateau by the time of the last measured time point. Open squares, 25 °C data. Filled circles, 10 °C data. The lower temperature data tended to fall short of 100% exchange. Most of the 25 °C results reached 100% exchange. Deviations of the open squares from the line of identity indicate the effect of the imprecision in back exchange corrections: ± 0.95 Da. See text.

Kinetics of H/D Exchange in TnI

H/D exchange kinetic data were acquired for 18 TnI peptides, following exposure of the ternary troponin complex to D2O at 10 °C, in the same experiments described above for TnC. Data and curve-fitting analyses for most of these peptides are illustrated in Fig. 3.

FIGURE 3.

Kinetics of H/D exchange in troponin. TnI peptides are shown. TnI peptide mass increases were determined after exposure of troponin to D2O at 10 °C for times between 5 s and 48 h. In the thumbnail images, the locations of graphed peptides are indicated as black space-filling sections, and/or by gray circles for regions not identified by x-ray crystallography.

The dynamic properties of TnI helix 1 were characterized by H/D exchange data for four overlapping peptides: 54–66, 54–78, 62–85, and 78–88. The peptides included hydrogens that were strikingly unprotected, as well as hydrogens that were very stable and highly protected. For example, Fig. 3 shows exchange occurred before 5 s for ∼9 hydrogens within peptides 54–78 and 62–85. Thus, part of TnI helix 1 is highly flexible, even at 10 °C. On the other hand, the helix 1 peptides also contained hydrogens that required many hours or days to exchange H for D. In particular, there was little exchange by 105 s for TnI 54–66, which binds to the TnC COOH-domain. This suggests that the helix 1-TnC interaction is quite stable.

Fig. 3 also shows data for peptides 91–96, 97–109, 97–116, 117–124, and 125–134, which together span the length of the TnI strand of the TnI-TnT coiled coil. For the most part, these were highly stable regions, taking days or longer to undergo H/D exchange, and implying protection factors of 105 or greater. Interestingly, most of the hydrogens within peptide TnI 117–124 underwent much more rapid exchange, suggesting that this portion of the helix is much more dynamic than the rest.

TnI peptide 125–152 includes the so-called inhibitory peptide region, 137–147 (24–26). In the TnI sequence this region intervenes between the end of the coiled-coil strand and the Ca2+-regulated TnI switch helix. In the Fig. 3 panel for peptide 125–152, this un-visualized segment links together the two regions indicated in black space filling mode. (The inhibitory region is absent in this thumbnail cartoon, because it was not identified in the cardiac troponin high resolution structure (23).) In contrast to the highly protected 125–134 at the end of the coiled-coil, 11 hydrogens of 125–152 exchanged before 5 s. Thus, all or most of the inhibitory region was unprotected in Ca2+-saturated cardiac troponin, even at 10 °C. This is supported not only by the crystallography result, but also by EPR studies indicating uniform dynamics across the cardiac TnI inhibitory peptide region (27). However, it differs from the high resolution structure of skeletal muscle troponin (28).

The amphipathic TnI switch helix has a critical role in the regulation of muscle contraction. It binds to the TnC NH2-domain in a Ca2+-dependent manner (28, 29), which relieves inhibitory actions of troponin and tropomyosin (30). Parts of the switch helix are present in peptides 125–152 and 156–169. The transitions for these peptides were complex, but the H/D exchange data are consistent with 60-fold protection from exchange for the switch helix region.

Finally, Fig. 3 shows data for TnI 162–169, 170–190, 191–197, and 197–210 in the TnI COOH-terminal region. The corresponding, conserved (31) region of skeletal muscle troponin is poorly folded according to NMR analyses (32, 33). Correspondingly, many of the hydrogens exchange quickly, especially in peptides 162–169 and 191–197. Notably, however, the majority of the hydrogens in this COOH-terminal region show detectable, measureable protection form H/D exchange. In other words, they exhibit some degree of protein folding.

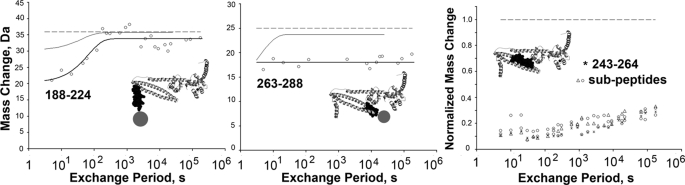

Kinetics of H/D Exchange in TnT

H/D exchange kinetic data were acquired for 11 TnT peptides, obtained in the same experiments described above for the other subunits. TnT 188–224 had a well defined H/D exchange transition occurring at ∼1 min (Fig. 4). This transition indicated a mobile, modestly folded region. It reasonably can be assigned to TnT helix 1 (black space-filling representation) within the larger 188–224 peptide. Phosphorylation of Thr-203 near the start of this helix alters troponin function, by an unknown mechanism (34). Those hydrogens exchanging before 5 s largely were assigned to the NH2-terminal portions of peptide 188–224, which were disordered in the crystallography data (schematic gray circle in the thumbnail inset of the same graph).

FIGURE 4.

Kinetics of H/D exchange in troponin. TnT peptides are shown. TnT peptide mass increases were determined after exposure of troponin to D2O at 10 °C for times between 5 s and 48 h. Note that the rightmost panel shows fractional exchange, rather than mass increase. In the thumbnail images, the locations of graphed peptides are indicated as black space-filling sections, and/or by gray circles for regions not identified by x-ray crystallography.

The TnT COOH-terminal peptide 263–288 includes the last 8 residues of the TnT-TnI coiled-coil, followed by a loosely conserved, positively charged region (gray circle in inset). At 10 °C, the end of the coiled-coil was very tightly folded and highly protected. The loosely conserved region exchanged immediately, but after that, there was no additional exchange detectable in peptide 263–288 over 48 h in D2O. This represents a striking effect of temperature on the end of the coiled-coil, because at 25 °C H/D exchange was complete within the first 10–20 s (thin line).

Finally, the data show that the TnT strand of the TnI-TnT coiled-coil was particularly stable, evidenced by high protection from exchange. For example, Fig. 4 shows the normalized mass changes for a group of overlapping peptides spanning TnT residues 243–263. The data showed no clear transition anywhere across the region. Peptide masses increased very little between 5 s and 2 days. Only 25–30% of hydrogens exchanged in total after 48 h.

Primary Sequence Map of Troponin Dynamics

Fig. 5 provides a pictorial summary of the present results for all three troponin subunits. Fine mapping was governed by crystallographic results (see “Experimental Procedures”). Fig. 5 illustrates an extremely wide variation in dynamics within troponin. Using a logarithmic scale, the most unprotected, mobile regions are shown in red and the most protected, stably folded regions in violet.

One value of this representation is that it conveys the properties not only of regions that were detectable by x-ray crystallography but also of regions that were undetectable (black boxes in Fig. 5). Many of the regions not detected in the troponin x-ray structure lacked H/D exchange protection, and are correspondingly colored red in the figure. Thus, they are disordered in solution, despite reasons to consider otherwise in some cases (see “Discussion”). Other regions exhibited some protection indicating folding. In particular, the TnI COOH terminus exhibited significant protection from exchange.

Fig. 5 also facilitates, at a glance, the identification of regions that were highly dynamic and unprotected. Unfolded or minimally folded regions included both termini of the TnT construct, part of TnI helix 1, scattered residues in TnC, and a studied part of the TnI NH2 terminus.

Finally, the figure shows that the most stable parts of troponin were the TnI-TnT coiled-coil, part of TnI helix 1, and scattered residues in TnC. The coiled-coil particularly stands out in this representation as highly protected from HDX. A local dynamic region (coded orange) near TnI120 was a notable exception to this pattern within the coiled-coil. The structural basis and possible importance of this exception are unclear.

DISCUSSION

In the present study, H/D exchange-mass spectrometry was used to obtain a detailed, extensive map of troponin dynamics properties. The results provide a number of insights. Troponin is a very mobile protein, and its dynamics are sensitive to temperature. The ternary troponin complex appears dependent for stability on a few regions that, in contrast to the remainder of the protein, are tightly folded. These regions are the TnI-TnT coiled-coil, as well as the interaction between the TnI helix 1 and the TnC COOH-domain. The results also show that the direct regulatory region, comprised of the TnC NH2-domain and the TnI switch helix, is relatively mobile. Further, they show that this region is connected only loosely to the rest of troponin by highly mobile regions. Another notable finding is that most of the TnI COOH terminus exhibits H/D protection, suggesting it adopts an ordered structure under appropriate conditions.

These and other results are illustrated in Fig. 6, in which the Fig. 5 results are mapped onto the high resolution structure of troponin. Panel A conveys the detailed map in cartoon-ribbon format, in the same orientation as in Fig. 1. The corresponding dots-mode representation in panel B conveys a more qualitative idea of the relative dynamics of different parts of troponin. The dynamics are highly contrasting within the protein, including a few very stable regions that are critical for formation of this ternary complex, and many other parts of the molecule that are only weakly folded or unfolded.

In Fig. 6C, the different subunits are shown in different formats, to visualize important properties of TnC, including its interactions with TnI. The TnC COOH-domain wraps partially around TnI helix 1. The stability of this interaction is suggested by the very great protection from H/D exchange of the TnI helix and its contact region within TnC. In contrast, the regulatory NH2-domain of TnC is more dynamic, as is the TnI switch helix to which it attaches. Thus, there is a stark contrast between the two interactions. This may correspond to their very contrasting roles in either troponin structure or in troponin regulatory switching. However, alterations in TnI helix 1 also affect troponin function (35–37).

Two high resolution x-ray studies of troponin have been reported, one for cardiac troponin and one for skeletal muscle troponin. Among other findings, the present report addresses the significance of a major difference between the two Ca2+-saturated structures. Cardiac troponin contained a discontinuity between TnC helix D and helix E. Also, the position of the TnC NH2 domain was variable, and TnI residues preceding the switch helix were disordered. The present report supports these findings by demonstrating corresponding, very dynamic solution properties for cardiac troponin. The relevant portions of cardiac TnC and TnI are unprotected. Since they are unprotected at 10 °C, they would also be substantially unfolded at higher temperature. (We erred in suggesting otherwise in our previous report, based on extrapolation, to before 5 s, of data here shown as the thin line for TnI 125–152 in Fig. 3).

This finding is indicated in Fig. 6C by the red-colored TnC D/E connector. The result suggests that the on-off mechanism of cardiac troponin differs from that of skeletal muscle troponin. In both, the TnI switch helix attaches to the TnC NH2-domain upon Ca2+ binding. For skeletal muscle but not cardiac troponin, the switch also includes Ca2+-dependent interactions of TnI with a continuous TnC D/E helix. A long D/E helix is also present in calmodulin (38) and in isolated TnC (3). Therefore, it was reasonable to question whether the contrary aspect of cardiac troponin structure was a consequence of crystallization, or rather was a true reflection of solution behavior. Our results strongly support the latter of these two possibilities.

H/D protection of residues toward the COOH terminus of TnI was unexpected based on NMR results (33), which showed absent secondary structure for this region within skeletal muscle troponin. It is unclear whether differences between these results and the present study are attributable to troponin isoforms, or are attributable to different conditions such as temperature. In any case, protection was found consistently in the present work, in peptides 162–169, 170–190, and 191–210. The extent of protection was not different from many other areas of troponin, so it is likely that the protection indicates structure formation under these low temperature conditions. This has functional significance. In the thin filament context, this part of troponin is believed to help effect the inhibition of muscle contraction under low Ca2+ conditions, via interactions with actin and tropomyosin (39–42). Mutations in this region cause inherited cardiomyopathy and alter function (43–45). Truncation studies indicate it has effects on sarcomere function in the presence of Ca2+ (46) as well, and has an activating effect on tropomyosin position when Ca2+ binds to troponin (47). Based on the present H/D exchange findings, the region is likely to have a specific, ordered structure(s) and interaction with actin and tropomyosin, rather than to act as an intrinsically disordered region. Further, we suggest that its structure is nascent, and can be evoked either by low, non-physiological temperature, or by binding to the thin filament.

In the present work, H/D exchange was used to acquire detailed insights regarding the dynamic properties of Ca2+-saturated troponin. In addition to present worth, these data should prove valuable for future studies. For example, we plan to determine the quantitative effects of Ca2+ binding to site II on troponin dynamics, by comparing the present results to experiments using a troponin with site II mutations that prevent Ca2+ binding.

This work was supported, in whole or in part, by National Institutes of Health Grants HL063774 and HL038834, and also by the CBC/UIC Proteomics and Informatics Facility, established by a grant from The Searle Funds at the Chicago Community Trust to the Chicago Biomedical Consortium.

- Tn

- troponin.

REFERENCES

- 1.Tobacman L. S. (1996) Annu. Rev. Physiol. 58, 447–481 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kobayashi T., Solaro R. J. (2005) Annu. Rev. Physiol. 67, 39–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gordon A. M., Homsher E., Regnier M. (2000) Physiol. Rev. 80, 853–924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zot A. S., Potter J. D. (1987) Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biophys. Chem. 16, 535–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vibert P., Craig R., Lehman W. (1997) J. Mol. Biol. 266, 8–14 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pirani A., Vinogradova M. V., Curmi P. M., King W. A., Fletterick R. J., Craig R., Tobacman L. S., Xu C., Hatch V., Lehman W. (2006) J. Mol. Biol. 357, 707–717 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Heeley D. H., Belknap B., White H. D. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 16731–16736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Poole K. J., Lorenz M., Evans G., Rosenbaum G., Pirani A., Craig R., Tobacman L. S., Lehman W., Holmes K. C. (2006) J. Struct. Biol. 155, 273–284 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Robinson J. M., Dong W. J., Xing J., Cheung H. C. (2004) J. Mol. Biol. 340, 295–305 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mudalige W. A., Tao T. C., Lehrer S. S. (2009) J. Mol. Biol. 389, 575–583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Maytum R., Lehrer S. S., Geeves M. A. (1999) Biochemistry 38, 1102–1110 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tobacman L. S., Butters C. A. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 27587–27593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Englander S. W. (2000) Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 29, 213–238 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smith D. L., Deng Y., Zhang Z. (1997) J. Mass Spectrom. 32, 135–146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Arrington C. B., Robertson A. D. (2000) Methods Enzymol. 323, 104–124 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim K. S., Fuchs J. A., Woodward C. K. (1993) Biochemistry 32, 9600–9608 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huyghues-Despointes B. M., Scholtz J. M., Pace C. N. (1999) Nat. Struct. Biol. 6, 910–912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bai Y., Milne J. S., Mayne L., Englander S. W. (1993) Proteins 17, 75–86 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kowlessur D., Tobacman L. S. (2010) J. Biol. Chem. 285, 2686–2694 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Swint L., Robertson A. D. (1993) Protein Sci. 2, 2037–2049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Milne J. S., Xu Y., Mayne L. C., Englander S. W. (1999) J. Mol. Biol. 290, 811–822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang Z., Marshall A. G. (1998) J. Am. Soc. Mass Spectrom. 9, 225–233 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takeda S., Yamashita A., Maeda K., Maéda Y. (2003) Nature 424, 35–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Talbot J. A., Hodges R. S. (1981) J. Biol. Chem. 256, 12374–12378 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Syska H., Wilkinson J. M., Grand R. J., Perry S. V. (1976) Biochem. J. 153, 375–387 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Van Eyk J. E., Hodges R. S. (1988) J. Biol. Chem. 263, 1726–1732 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brown L. J., Sale K. L., Hills R., Rouviere C., Song L., Zhang X., Fajer P. G. (2002) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 99, 12765–12770 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Vinogradova M. V., Stone D. B., Malanina G. G., Karatzaferi C., Cooke R., Mendelson R. A., Fletterick R. J. (2005) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 5038–5043 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li M. X., Spyracopoulos L., Sykes B. D. (1999) Biochemistry 38, 8289–8298 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Galińska-Rakoczy A., Engel P., Xu C., Jung H., Craig R., Tobacman L. S., Lehman W. (2008) J. Mol. Biol. 379, 929–935 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jin J. P., Yang F. W., Yu Z. B., Ruse C. I., Bond M., Chen A. (2001) Biochemistry 40, 2623–2631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hoffman R. M., Blumenschein T. M., Sykes B. D. (2006) J. Mol. Biol. 361, 625–633 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Blumenschein T. M., Stone D. B., Fletterick R. J., Mendelson R. A., Sykes B. D. (2006) Biophys. J. 90, 2436–2444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sumandea M. P., Pyle W. G., Kobayashi T., de Tombe P. P., Solaro R. J. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 35135–35144 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kronert W. A., Acebes A., Ferrús A., Bernstein S. I. (1999) J. Cell. Biol. 144, 989–1000 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Burkart E. M., Sumandea M. P., Kobayashi T., Nili M., Martin A. F., Homsher E., Solaro R. J. (2003) J. Biol. Chem. 278, 11265–11272 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mathur M. C., Kobayashi T., Chalovich J. M. (2008) Biophys. J. 94, 542–549 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Babu Y. S., Sack J. S., Greenhough T. J., Bugg C. E., Means A. R., Cook W. J. (1985) Nature 315, 37–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Rarick H. M., Tu X. H., Solaro R. J., Martin A. F. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 26887–26892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tripet B., Van Eyk J. E., Hodges R. S. (1997) J. Mol. Biol. 271, 728–750 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ramos C. H. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 18189–18195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Luo Y., Wu J. L., Li B., Langsetmo K., Gergely J., Tao T. (2000) J. Mol. Biol. 296, 899–910 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kobayashi T., Solaro R. J. (2006) J. Biol. Chem. 281, 13471–13477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Gomes A. V., Liang J., Potter J. D. (2005) J. Biol. Chem. 280, 30909–30915 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mathur M. C., Kobayashi T., Chalovich J. M. (2009) Biophys. J. 96, 2237–2244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Foster D. B., Noguchi T., VanBuren P., Murphy A. M., Van Eyk J. E. (2003) Circ. Res. 93, 917–924 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Galińska A., Hatch V., Craig R., Murphy A. M., Van Eyk J. E., Wang C. L., Lehman W., Foster D. B. (2010) Circ. Res. 106, 705–711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]