Abstract

It is now well demonstrated that cell adhesion to a foreign surface strongly influences prominent functions such as survival, proliferation, differentiation, migration or mediator release. Thus, a current challenge of major practical and theoretical interest is to understand how cells process and integrate environmental cues to determine future behaviour. The purpose of this review is to summarize some pieces of information that might serve this task. Three sequential points are discussed. First, selected examples are presented to illustrate the influence of substratum chemistry, topography and mechanical properties on nearly all aspects of cell behaviour observed during the days following adhesion. Second, we review reported evidence that long term cell behaviour is highly dependent on the alterations of cell shape and cytoskeletal organization that are often initiated during the minutes to hours following adhesion. Third, we review recently obtained information on cell membrane roughness and dynamics, as well as kinetics and mechanics of molecular interactions. This knowledge is required to understand the influence of substratum structure on cell signaling during the first minute following contact, before the appearance of detectable structural changes. It is suggested that unraveling the earliest phenomena following cell-to-substratum encounter might provide a tractable way of better understanding subsequent events.

Keywords: Adhesion, cell behaviour, substratum topography, substratum rigidity, signaling

Cell adhesion to foreign surfaces strongly influences nearly all functions, including proliferation, differentiation, migration or release of active mediators. These phenomena are of prominent importance for both practical and theoretical reasons. Indeed, a major challenge of tissue engineering consists of elaborating biomaterials inducing adequate response of surrounding tissues, with proper integration and inhibition of potentially harmful inflammatory or infectious processes. Also, the ultimate goal of cell biologists may well be to understand the rules followed by cells for behavioural choices. Studying the consequences of cell adhesion to well-defined controlled structures should bring major insights along this line.

During the last years, numerous investigators provided impressive information on the way cells respond to substrate properties such as molecular structure, lateral density and distribution of active sites, mechanical properties, micrometer- or nanometer-scale topography. Also, the involvement of some well-defined signalling cascades in these sensing events was convincingly demonstrated. The present challenge may well be to make sense from the huge amount of data that have been gathered. The complexity of this task may seem quite overwhelming in view of the number of molecules and genes involved in response to environmental cues. Indeed, since a limited perturbation of the cell environment may affect hundreds of important interrelated molecules, it is very difficult to obtain unambiguous proofs of an immediate relationship between a surface pattern and the triggering of a given signalling cascade in adherent cells.

The strategy we suggest to tackle with these difficulties is to analyze the phenomena occurring during the first few seconds following the encounter between a cell and a surface. Hopefully, this approach might allow us to identify surface properties liable to influence cell behaviour in a fairly immediate way. However, as will be discussed below, following this line will require to gather some insight on some cell molecular processes that remain incompletely understood at the present time. However, asking questions may be more appropriate than describing solved problems in an inaugural issue of a scientific journal.

This review will include three main parts. First, we shall describe some representative examples of cell response to substratum properties. Second, we shall review some evidence supporting the concept that cell shape and cytoskeletal organization may provide a link between environmental cues and cell behavioural choices. Third, we shall describe some recent results concerning cell membrane dynamics, as a basis for cell-substratum interaction.

SURFACE PROPERTIES KNOWN TO INFLUENCE ADHERENT CELL BEHAVIOUR

Our purpose is to illustrate basic principles with representative examples rather than presenting exhaustive reviews. Therefore, we apologize for the omission of much important work. We shall only list some surface parameters that are now recognized as important determinants of cell behaviour.

Surface chemistry

The best known example of the importance on surface chemistry on cell behaviour may well be the need to subject plastic (polystyrene) dishes to a specific treatment to make them suitable for cell culture. This emphasizes the important of nonspecific features such as hydroxyl groups that will decrease surface hydrophobicity1. Another example is the long-known capacity of phagocytic cells to ingest selectively hydrophobic particles2. More recently, a study made at the proteomic level resulted in the identification of 21 genes of Hela Cells whose expression was substantially altered by substratum hydrophobicity after 24h adhesion3.

Now, while the importance of surface charge or hydrophobicity was studied for decades, it is not obvious that cells are intrinsically sensitive to these nonspecific physical-chemical properties. As recently discussed4, most recent evidence supports the concept that cells essentially perceive foreign surfaces through membrane receptors that are specific for well defined molecular structures. Since biomaterials become coated with adsorbed molecules within seconds following their exposure to biological media, and the conformation of adsorbed biomolecules is dependent on the physical-chemical properties of underlying surfaces, cells may detect these properties in an indirect way, through exposure of specific binding sites linked to conformational changes. Thus, fibronectin was found to support cell growth much more efficiently when it was adsorbed on hydrophilic rather than hydrophobic surfaces5.

Nature, density and lateral distribution of specific ligands

The most general mechanism allowing cells to respond to surfaces they have just encountered is the generation of biochemical signalling cascades following the interaction between cell membrane receptors and their specific ligands when they are exposed on the surfaces. Multiple experiments supported the general concept that the cell response is dependent on the nature of stimulated receptors. As an example, different receptors may be involved in mediating cell attachment to and spreading on a surface6. Now, in addition to the ligand species, density and distribution of binding sites may strongly influence cell behaviour. Thus, the migration behaviour of fibroblasts deposited on surfaces coated with an integrin ligand (YRGDS peptide) was markedly influenced by the spatial distribution of binding sites at the nanoscale level7. More recently, it was reported that the spreading of rat fibroblasts on surfaces coated with RGD integrin ligands was markedly influenced by the spacing of binding sites: when the distance between binding sites was increased from 58 to 108 nm, spreading efficiency decreased with less regular progression of the cell leading edge and frequent occurrence of retraction events8.

Several well-demonstrated mechanisms might be responsible for these findings. First, ligand clustering may dramatically enhance cell attachment efficiency since binding strength may increase exponentially with respect to attachment valency9. Second, clustering of cell membrane molecules such as integrins may dramatically influence the triggering of signalling cascades as a consequence of interactions between intracellular molecules linked to the receptors. Thus, receptor clustering may influence signalling in a qualitative as well as a quantitative way10.

Surface topography

It has been well demonstrated for several decades that cells deposited on substrata bearing micrometric patterns adapted their shape and orientation to the topological features of the surface, a phenomenon called “contact guidance”. Thus, cells displayed marked alignment along grooves of micrometrical depth and width11. More recently, it was also shown that cells are sensitive to nanoscale topography. Thus, when fibroblasts were deposited on surfaces bearing islands of 13-nanometer height, they displayed marked enhancement of gene expression, as demonstrated with microarray technology12. Indeed, 584 responses were detected out of 1,718 tested genes. Also, nanoislands induced filopodium formation and cell spreading. Further work allowed the identification of molecules involved in force generation, such as myosin II, and focal contact development, such as focal adhesion kinase, in topography sensing71.

Additional information was obtained with different approaches. Thus, when nanoscale patterns were varied, it appeared that the adhesion of human fibroblasts was lower on ordered arrays of nanopits compared to flat surfaces or randomly distributed pits13. Another study might provide additional information on underlying phenomena. The activation of T lymphocytes by surfaces exposing complexes formed by cognate peptides and histocompatibility molecules (pMHC) is a process of prominent importance for the development of immune defence. When T lymphocytes were deposited on surfaces bearing pMHC freely diffusing in supported lipid layers, the addition to surfaces of nanobarriers impeding the lateral diffusion of complexes formed between T cell receptors (TCR) and pMHC resulted in marked increase of the lifetime of signal generation by peripheral TCR/pMHC clusters14. This work provided a formal proof that the presence of nanostructures on surfaces might strongly influence the development of signaling cascades.

While there is no doubt that cell behaviour is influenced by nanoscale topography, underlying mechanisms remain ill understood. The aforementioned finding that barriers as low as 50 nm might efficiently alter lateral diffusion of molecular complexes is certainly significant. Also, there is some evidence that local surface curvature might influence molecular interactions in the cell membrane15. Thus, substratum topography is likely to influence the in-plane movement and interactions of the proteins embedded in the cell membrane. This may drastically influence the generation of signaling cascades.

Surface stiffness

It is now well demonstrated that the behaviour of adherent cells is markedly altered by surface mechanical properties. Thus, when fibroblasts were deposited on collagen surfaces with local variations of rigidity, they were found to migrate towards stiffer regions, a phenomenon denominated by the authors as “durotaxis”16. More recently, when human mesenchymal stem cells were deposited on collagen-coated surfaces of varying rigidity, cell differentiation was dramatically affected by substratum stiffness. Indeed, cells deposited on softer matrices with a Young modulus of ~0.1 – 1 kPa differentiated into neurons. Stiffer surfaces (about 10 kPa) induced muscle cell generation. Finally, cells deposited on the stiffest surfaces (25–40 kPa) turned into osteoblasts17.

In addition to the formal demonstration that cells are highly sensitive to the substratum rigidity, important information was obtained on possibly involved mechanisms. First, it has long been found that adherent cells usually exert a pulling force on underlying substrata18. Second, the force exerted by cells is dependent on the substratum resistance. This phenomenon was cleverly demonstrated by applying controlled forces to fibronectin-coated microspheres deposited on cells and held with an optical trap19. Cells were indeed found to sense the restraining force exerted by the trap and locally increase pull. A possibly related finding is that forces were shown to stimulate focal contact development72. Third, using cell spread area determination to evidence rigidity sensing, Sheetz and collaborators demonstrated the involvement of some key molecules such as αVβ3 integrin and membrane-bound phosphatases in this process20.

Several points must be clarified for full interpretation of available data. First, it is not obvious to understand which precise substratum property is sensed by cells. Indeed, while the tension of cells adhering to a surface seems correlated to the Young modulus, other substratum properties must influence cell perception. Indeed, cells probably sense the kinetics of force increase when they pull on the substratum. This clearly depends on surface viscosity as well as elasticity. Also, it should be interesting to determine whether cells are equally sensitive to resistance to pushing as well as pulling forces. Although little information is available in this respect, it is interesting to note that a force as low as a few piconewtons per μm was reported to stall lamellipodia generated by fish epithelial keratocytes21.

CELL-SUBTRATUM SENSING: A COMMON MECHANISM?

While there is no doubt that the behaviour of adherent cells is deeply influenced by substratum properties, there is currently no theoretical framework available to achieve a general interpretation of experimental data. In this respect, it is interesting to review several reports suggesting that cell shape might provide a link between environment and fate.

Cell shape as an integrator of environmental signals

As recently reviewed22, cell spreading plays a key role in important functions such as proliferation or differentiation. Thus, human mesenchymal cells underwent osteogenic differentiation when they well spread, whereas round cells became adipocytes23. That cell shape rather than contact area and number of bound membrane receptors might be the important parameter is suggested by the finding that cell proliferation, that is often dependent on adhesion, was shown to be related to projected area, i.e. cell shape, rather than molecular adhesion area24.

More studies are needed to understand the link between cell shape and behaviour. As suggested above15, local curvature might influence interaction between membrane molecules. Another mechanism of potential importance is based on the formation of activity gradients of enzymes that might be activated by plasma membrane receptors and deactivated by cytosolic components, as supported by experimental data and theoretical modeling25,26. As another example, there is some evidence that the cytoskeleton organization might link cell shape to behaviour through a control of the small GTPase Rho27. More generally, while there is ample evidence that cell cytoskeletal organization is tightly related to cell shape, there is also strong support to the hypothesis that signaling cascades are markedly influenced by cytoskeletal organization. This point is discussed below.

Cell signaling and cytoskeletal organization

In addition to its capacity to propagate mechanical effects within cells and convert stresses into signals28,29, the cytoskeleton may strongly influence signaling30. Since signaling cascades are essentially made of sequential interactions between numerous enzymes, targets and adapters, the cytoskeleton might play a major role by promoting interactions between particular molecules28. A possible rationale for such a function was recently suggested on the basis of recent advances in proteomics31. Forgacs and colleagues performed a mathematical analysis of the set of molecular interactions (i.e. interactome) disclosed between proteins from Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Starting from a database of 4,480 interactions between 2,115 proteins32, they were able to show that cytoskeleton related proteins were endowed with a particularly high capacity to interact with molecules involved in signalling.

A FOCUS ON TRANSIENT DYNAMIC EVENTS

As illustrated by the selected examples described above, cells adhering to a foreign surface can perceive a number of features related to surface chemistry, topography or rigidity and integrate all information to select behavioural pathways. Since it is unlikely that cells view these parameters as we do, a major challenge is to understand the general mechanisms of data processing they use. A general problem is that a given cell perturbation will affect hundreds of different parameters, making it difficult to identify clearcut causal phenomena (provided they actually exist !). A possible strategy to achieve this goal might consist of identifying early phenomena determining long-term events, such as differentiation or proliferation monitored after a few days. As briefly sketched above, cell shape and cytoskeletal organization are good candidates since much evidence support the view that they are causally related to both long-term cell behaviour and substratum structure. Thus, it seems warranted to investigate the processes by which adherent substrata influence cell properties, with a special interest in shape and cytoskeletal organization. During the last years, much information was obtained on cell changes detected a few minutes or more after encounter with foreign surfaces. However, relatively little information is available on the cell response observed during the first seconds or tens of seconds following such encounters. We suggest that this study might prove rewarding, since causal relationships may be easier to detect when there is a short time interval between stimuli and responses.

A first question is to know how long it takes a cell encountering a surface to initiate a specific behavioural response. Previous studies done on cell adhesion suggest that metabolic events33 and cooperation between adhesion molecules34,35 are less important during the first tens of seconds after contact. Thus, it might be feasible to identify immediate consequences of cell-surface interaction by focussing on the first minutes following contact. For the sake of clarity, we shall discuss separately bulk membrane motion at interfaces, forces potentially generated by this motion, and lateral redistribution of membrane molecules at interfaces as a key determinant of signaling processes.

Bulk membrane motion at interfaces

Understanding how cells perceive foreign surfaces requires to know how the cell membrane will make contact with its environment. During the last decades, much information was obtained with at least three complementary techniques. Electron microscopy certainly provided the most accurate information. Unfortunately, the need to subject cells to fixation procedures precludes any real-time observation. Interference reflection microscopy (IRM)36 also denominated as reflection interference contrast microscopy (RICM)37 allows real-time observation of the distance between a cell and a planar surface with a few nanometer accuracy, while the lateral resolution is not better than several tenths of a micrometer. The interest of this method is that no staining procedure is required. Total internal reflection microscopy (TIRF) takes advantage of evanescent waves to illuminate a region of 100–200 nm thickness adjacent to a planar glass surface. After proper labelling of the extracellular medium38 or the cell membrane39, it is possible to achieve real-time determination of the motion of membrane along the surface.

Although different cell populations may display widely different behaviour, a general trend is as follows: several minutes to hours after sedimentation on a surface, a cell may begin extending membrane protrusions parallel to the surface. They may be sheet-like lamellipodia or thin filopodia (Fig. 1). It has long been reported that well defined mediators were involved in the choice between different shapes40: thus, the small GTPase Rac was reported to induce lamellipodium generation with a branched organization of actin microfilaments, while the small GTPase Cdc42 was found to initiate the extension of cylindrical filopodia shaped by a microfilament bundle. The choice between lamellipodium or filopodium formation may be influenced by substratum properties such as density of binding sites10, topography41 or rigidity17. A further point is that the cell margin was often reported to display fluctuations with periods of progress and retraction39. A typical period was several tens of seconds, and the reported velocity of the cell margin is of order of several tens of nanometers per second. Notably, when the density of adhesive points is high enough, this fluctuating behaviour may be replaced with a smooth progression.

Figure 1. Studying the morphology of cell-to-substratum contact extension with interference reflection microscopy.

Human T lymphocytes were deposited on glass surfaces coated with non-activating anti-HLA antibodies (A, C, E) or activating anti-CD3 antibodies (B, D, F). Cell morphology was monitored with standard microscopical observation (A, B) and interference reflection 15 minutes (C, D) or 30 minutes (E, F) after deposition. Clearly, contact extension was mediated by lamellipodia or filopodia depending of substratum structure. Bar length is 2 μm.

Now, a key point is to know how a cell can select the kind of motion it will display. At least two different mechanisms may be suggested: (i) cells might continuously form a low number of protrusions of varying morphology. Contact with the substratum might lead to reinforcement or inhibition trough a positive or negative feedback. (ii) Alternatively, the acquisition of a particular motile behaviour might be induced during an early phase of cell-substratum interaction as a consequence of some internal switch42.

Although it is not yet feasible to chose between aforementioned hypotheses, it seems reasonable to investigate the early phenomena following cell-to-surface encounter and preceding the morphological changes associated to spreading. Thus, it seems desirable to achieve a quantitative description of the motion and mechanical properties of the surface of an isolated cell in order to predict the consequences of interaction with a surface of known structure. While it has long been shown with electron microscopy that cell membranes are studded with numerous cylindrical or sheet-like protrusions appearing as folds of the plasma membrane, less information is available on the kinetic and mechanical properties of the membrane. The typical thickness of these protrusions or microvilli is about 0.1 μm, and length may range between a few tenths of micrometers and several micrometers. Since this value is far higher than the length of typical adhesion receptors, it is not surprising that the initial interaction between cells and surfaces involves the tip of microvilli43. Now, there remains to understand the dynamics of the cell surface immediately before adhesion.

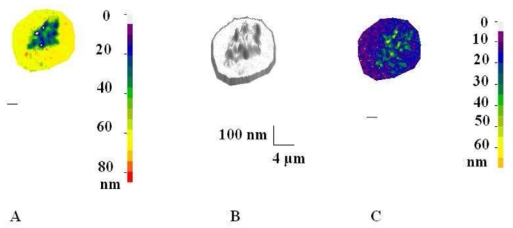

Recently, microscopic studies based on IRM/RICM suggested that the membranes of phagocytes approaching adhesive surfaces displayed fluctuations of higher than 1 Hz frequency and several nanometer amplitude44,45. A typical map of cell topography and dynamics near a surface is shown on Fig. 2. Unfortunately, the lateral resolution of IRM/RICM may be insufficient to yield accurate information on the motion of individual microvilli. Also, the mechanical properties of these surface protrusions remain poorly understood. In two sets of experiments based on micropipette and biomembrane force probe, it was shown46,47 that blood neutrophil microvilli could withstand a pulling force of about several tens of pN before separation between the membrane and underlying cytoskeleton and formation of a lipid tether. Clearly, more information is required to help us determine the kinetics of cell-to-substratum initial contacts together with the intensity of generated forces. This knowledge is important since local molecular organization and signal generation are expected to be strongly influenced by these parameters.

Figure 2. Three-dimensional reconstruction of cell surface morphology and dynamics near an adhesive surface.

Human monocytic THP-1 cells were deposited on fibronectin-coated surfaces and observed with interference-reflection microscopy. The shape of the cell membrane is shown as a coded-colour map (A) or a 3-D drawing (B) together with the amplitude of spontaneous membrane fluctuations. Bar length is 2 μm. See ref44 for more details.

Forces between cell and substratum

A basic question we must address is to know what force a cell membrane will perceive when approaching a foreign surface. While numerous nonspecific interactions such as electrodynamic or electrostatic forces are likely to occur, it seems acceptable to focus on two dominant phenomena: steric repulsion and specific ligand-receptor interactons4.

Steric repulsion

As previously reviewed48, it is well established that essentially all living cells are coated with a polysaccharide-rich layer of widely varying thickness, ranging between a few tenths of a micrometer and several micrometers. This is called the glycocalyx. This highly hydrophilic layer will impede close approach between the plasma membrane and a nearby surface. Therefore, it is usually considered as anti-adhesive, although in some cases the outermost carbohydrate group may bind to lectin-like receptors exposed on adjacent surfaces. The glycocalyx may involve huge polysaccharides or proteoglycans with a molecular weight higher than 1,000,000 dalton. Also, particularly on white blood cells, it includes large mucin-like molecules that have been well identify. The most important examples may be leukosialin (CD43) and CD45.

Clearly, it would be desirable to know the distance dependence of repulsion generated by the glycocalyx. This is difficult in view of the heterogeneity of glycocalyx components. However, a major point that emerged nearly a decade ago49,50 is that this repulsion exhibits a strong time-dependent decay that may be due (i) to an internal reorganization of repulsive chains (this has not been well demonstrated to-date) and (ii) to an egress of repulsive molecules from contact areas51,52. As will be discussed in the next section, this point is of paramount importance since it may strongly influence the outcome of cell-surface interaction.

Molecular attractive bonds

As recently reviewed53,54, the formation and dissociation of bonds between surface-attached molecules was subjected to considerable scrutiny during the last decade. A thorough description of these phenomena would not fall into the scope of the present paper and we shall only summarize essential conclusions.

A few years ago, it seemed reasonable to consider that the outcome of an interaction between two surfaces bearing cognate ligand and receptor molecules could be satisfactorily described by two parameters:

-

The rate of bond dissociation koff(F) as a function of force exerted on the bond. In many circumstances, it appeared that koff(F) followed so-called Bell’s law:

(1) Many experiments performed at the single molecule level with different tools such as laminar flow chambers, atomic force microscopes, biomembrane force probes or optical traps yielded for parameter F0 values usually ranging between several piconewtons and several tens of piconewtons. This is the order of magnitude of the force that can be exerted by a bond linking two surfaces subjected by a disruptive force.

The rate of bond formation kon when surfaces are at binding distance. This parameter proved much more difficult to measure, and even to define, than the rate of bond dissociation, and new methods might bring substantial progress in the near future55. A major problem is that the probability of bond formation between two surfaces bearing ligands and receptors is proportional to the number of receptor-ligand couples that are close enough to interact. Since the height of membrane asperities is often much larger than the length of typical adhesion receptors, the number of interacting molecules is strongly dependent on the details of membrane-to-surface alignment. Indeed, surface roughness was shown to change binding frequencies by nearly two orders of magnitude56.

Recently, another difficulty was recognized. Dissecting individual ligand-receptor couples made more and more obvious the concept that bond formation is a multiphasic process involving numerous intermediate binding states57,58,59. This means that bond formation may not be viewed as an all-or-none phenomenon, and the force that can be sustained by a newly formed bond is highly dependent on its history. Thus, it was recently found that adhesion molecules such as cadherins could form associations of widely different strength, with a spontaneous lifetime ranging between at least a few milliseconds and several seconds60.

Thus, when a cell membrane is close to a ligand-bearing surfaces, the frequency of bond formation and the force exerted by newly formed bonds on the membranes is dependent on complex binding properties that could be understood and measured only very recently. Clearly, this new information must be incorporated in a theoretical framework aimed at explaining how cell membranes perceive the presence of a potentially adhesive surface.

Signaling in contact zones: importance of lateral reorganization of membrane molecules

Clearly, the basic problem addressed in this review is to understand which signaling cascades will be generated by membrane-to-surface interactions.

In view of the above discussion, mechanical forces exerted on the cell membrane may generate signaling cascades through several mechanisms. Indeed, it has long been shown that membrane tension may activate calcium channels through direct interaction with lipid bilayers61. Also, it recently became clear that some adhesion molecules such as integrins are flexible machines liable to display large deformations resulting in exposition of new antigenic sites62. Clearly, this process might result in formation of docking sites for a variety of signaling molecules. Thus, it is not surprising that mechanical forces exerted on cells were often found to generate multiple biochemical processes such as calcium rise63 or phosphorylation64.

However, the main mechanism responsible for signal generation as a consequence of membrane-to-substratum interaction may well be the lateral segregation of membrane molecules. Indeed, due to the huge number of potential interactions between cell molecules32, generating encounters between enzymes and potential targets may be sufficient to initiate a biochemical cascade. Thus, integrin clustering is likely to play an important role in signal generation after integrin engagement65. Also, some evidence suggests that the mere passage of T lymphocyte receptors in a small phosphatase-free zone might increase phosphorylation of activating sites and recruitment of kinases66.

As a consequence, several different mechanisms might play a role in the perception of an adhesive substratum by a cell:

Clusters of binding sites for membrane receptors might result in receptor clustering.

The rearrangement of mobile repulsive molecules might result in phase separation and additional segregation of membrane molecules67.

Modulation of membrane molecule diffusion by topographic structures14 might further alter the formation of molecular complexes.

Thus, available evidence suggests potential mechanisms for signal generation during the earliest phase of interaction between a cell and a foreign surface.

CONCLUSION AND PERSPECTIVE

As summarized in the first part of this review, there is now ample evidence that cells adhering to a surface integrate several properties including chemistry, micrometer- and nanometer-scale topography, and mechanical properties to determine future behaviour. However, relating substratum properties to alterations of the expression of hundreds of genes as a consequence of the perturbation of a complex network of biochemical reactions seems a formidable task.

As indicated in the second part of this review, a possible way of simplifying this challenge may be provided by the frequent observation that important aspects of cell behaviour observed days or weeks after interaction with a surface are tightly related to modifications of cell shape and cytoskeletal organization that may be observed several minutes or days after adhesion. Since much progress was recently achieved in unraveling the mechanisms of cell spreading on a surface, it seems warranted to look for a better understanding of the relationship between substratum properties and cell shape. This is still a most difficult goal since even during the minutes an hours following cell adhesion a huge number of signaling cascades may be triggered.

As briefly sketched in the third part of this review, a possible way of progressing further might consist of investigating the earliest steps of cell-to-substratum interaction. Indeed, relating substratum structure to the phenomena occurring during the first seconds following contact might be conceptually easier than linking this structure to delayed events. The main question is to determine which parameters a cell is really probing. Thus, while it is well accepted that substratum rigidity strongly influences cell behaviour, the very stimulus responsible for cell response is not well understood. Indeed, if cells are sensitive to tension, there remains to understand how the tension generated by a cell is related to substrate resistance to force (is elasticity, or viscosity, or a combination of both the parameter to consider ?). Are the substratum resistance to pulling or pushing forces of similar importance? A logical way of addressing this problem is to try to relate substratum structure to signal generation, since the perception of a given environmental cue may be considered as equivalent to the signal it will generate. A requirement to approach this goal is to obtain a detailed figure of cell spontaneous motion in the vicinity of a potentially adhesive surface. Much progress was recently done in this domain.

Therefore, it is hoped that the suggested research line might be rewarding. However, a point of caution may be useful: while most studies were done on cells deposited on a 2-dimensional surfaces, it must be kept in mind that in many cases a 3-dimensional environment should be more relevant physiologically68,69,70. Despite this restriction, the exquisitely accurate pieces of information that can be obtained on cells interactions with surfaces should strongly increase our understanding of the way cells perceive their environment in the near future.

References

- 1.Curtis ASG, Forrester JV, McInnes C, Lawrie F. Adhesion of cells to polystyrene surfaces. J Cell Biol. 1983;97:1500–1506. doi: 10.1083/jcb.97.5.1500. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Capo C, Bongrand P, Benoliel AM, Depieds R. Nonspecific recognition in phagocytosis: ingestion of aldehyde treated erythrocytes by rat peritoneal macrophages. Immunology. 1979;36:501–508. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Allen LT, Fox EJP, Blute I, Kelly ZD, Rochev Y, Keenan AK, Dawson KA, Gallagher WM. Interaction of soft condensed materials with living cells: phenotype/transcriptome correlations for the hydrophobic effect. Proc Natl Acad Sci (USA) 2003;100:6331–6336. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1031426100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Vitte J, Benoliel AM, Pierres A, Bongrand P. Is there a predictable relationship between surface physical-chemical properties and cell behaviour at the interface ? European Cells and Materials. 2004;7:52–63. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v007a06. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grinnell F, Feld MK. Fibronectin adsorption on hydrophilic and hydrophobic surfaces detected by antibody binding and analyzed during cell adhesion in serum-containing medium. J Biol Chem. 1982;257:4888–4893. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Runyan RB, Versakovic J, Shur BD. Functionally distinct laminin receptors mediate cell adhesion and spreading: the requirement for surface galactosyltransferase in cell spreading. J Cell Biol. 1988;107:1863–1871. doi: 10.1083/jcb.107.5.1863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Maheswari G, Brown G, Lauffenburger D, Wells A, Griffith LG. Cell adhesion and motility depend on nanoscale RGD clustering. J Cell Sci. 2000;113:1677–1686. doi: 10.1242/jcs.113.10.1677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Calvacanti-Adam EA, Volberg T, Micoulet A, Kessler H, Geiger B, Spatz JP. Cell spreading and focal adhesion dynamics are regulated by spacing of integrin ligands. Biophys J. 2007;92:2964–2974. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.106.089730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Seifert U. Rupture of multiple parallel molecular bonds under dynamic loading. Physical Review Letters. 2000;84:2750–2753. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.84.2750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jirouskova M, Jaiswal JK, Coller BS. Ligand density dramatically affects integrin αIIbβ-mediated platelet signaling and spreading. Blood. 2007;109:5260–5269. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-10-054015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Clark P, Connolly P, Curtis ASG, Dow JAT, Wilkinson CDW. Topographical control of cell behaviour: II. Multiple grooved substrata. Development. 1990;108:635–644. doi: 10.1242/dev.108.4.635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dalby MJ, Yarwood SJ, Riehle MO, Johnstone HJ, Affrossman S, Curtis AS. Increasing fibroblast response to materials using nanotopography: morphological and genetic measurements of cell response to 13-nm-high polymer demixed islands. Exp Cell Res. 2002;276:1–9. doi: 10.1006/excr.2002.5498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Curtis ASG, Gadegaard N, Dalby MJ, Riehle MO, Wilkinson CDW, Artchison G. Cells react to nanoscale order and symmetry in their surroundings. IEEE Trans Nanobiosciences. 2004;3:61. doi: 10.1109/tnb.2004.824276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mossman KD, Campi G, Groves JT, Dustin ML. Altered TCR signaling from geometrically repatterned immunological synapses. Science. 2005;310:1191–1193. doi: 10.1126/science.1119238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reynwar BJ, Illya G, Harmandaris VA, Muller MM, Kremer K, Deserno M. Aggregation and vesiculation of membrane proteins by curvature-mediated interactions. Nature. 2007;447:461–465. doi: 10.1038/nature05840. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lo CM, Wang HB, Dembo M, Wang YL. Cell movement is guided by the rigidity of the substrate. Biophys J. 2000;79:144–152. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(00)76279-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Engler AJ, Sen S, Sweeney HL, Discher DE. Matric elasticity directs stem cell lineage specification. Cell. 2006;126:677–689. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2006.06.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harris AK, Wild P, Stopak D. Silicone rubber substrata: a new wrinkle in the study of cell locomotion. Science. 1980;208:177–179. doi: 10.1126/science.6987736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Choquet D, Felsenfeld DP, Sheetz MP. Extracellular matrix rigidity causes strengthening of integrin-cytoskeleton linkages. Cell. 1997;88:39–48. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)81856-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kostic A, Sheetz MP. Fibronectin rigidity response through Fyn and p130 Cas recruitment to the leading edge. Mol Biol Cell. 2006;17:2684–2695. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-12-1161. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bohnet S, Ananthakrishnan R, Mogilner A, Meister JJ. Weak force stalls protrusion at the leading edge of the lamellipodium. Biophys J. 2006;90:1810–1820. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.064600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pierres A, Benoliel AM, Bongrand P. Cell fitting to adhesive surfaces: a prerequisite to firm attachment and subsequent events. Eur Cell Materials. 2002;3:31–45. doi: 10.22203/ecm.v003a04. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.McBeath R, Pirone DM, Nelson CM, Bhadriraju K, Chen CS. Cell shape, cytoskeletal tension, and RhoA regulate stem cell lineage commitment. Dev Cell. 2004;6:483–495. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(04)00075-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen CS, Mrksich M, Huang S, Whitesides GM, Ingber DE. Geometric control of cell life and death. Science. 1997;276:1425–1428. doi: 10.1126/science.276.5317.1425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meyers J, Craig J, Odde DJ. Potential for control of signaling pathways via cell size and shape. Current Biol. 2006;16:1685–1693. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2006.07.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Haugh JM. Membrane-binding/modification model of signaling protein activation and analysis of its control by cell morphology. Biophys J. 2007;107:L93–L95. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.105213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mammoto A, Huang S, Ingber DE. Filamin links cell shape and cytoskeletal structure to Rho regulation by controlling accumulation of p190RhoGAP in lipid rafts. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:456–467. doi: 10.1242/jcs.03353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Janmey PA. The cytoskeleton and cell signalling: component localization and mechanical coupling. Physiol Rev. 78:763–781. doi: 10.1152/physrev.1998.78.3.763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhao XH, Lashinger C, Arora P, Szaszi K, Kapus A, McCulloch CA. Force activates smooth muscle α-actin promoter activity through the Rho signaling pathway. J Cell Sci. 2007;120:1801–1809. doi: 10.1242/jcs.001586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pennington SR, Foster BJ, Hawley SR, Jenkins RE, Zolle O, White MRH, McNamee CJ, Sheterline P, Simpson AWM. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:32112–32120. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705067200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Forgacs G, Yook SH, Janmey PA, Jeong H, Burd CG. Role of the cytoskeleton in signaling networks. J Cell Sci. 117:2769–2775. doi: 10.1242/jcs.01122. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Uetz P, Giot L, Cagney G, Mansfield TA, Judson RS, Knight JR, Lockshon D, Narayan V, Srinivasan M, Pochart P, Qureshi-Emili A, Li Y, Godwin B, Conover D, Kalbfleisch T, Vijayadamovar G, Yang M, Johnston M, Fields S, Rothberg JM. A comprehensive analysis of protein-protein interactions in Saccharomyces cerevisia. Nature. 2000;403:623–627. doi: 10.1038/35001009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pierres A, Tissot O, Malissen B, Bongrand P. Dynamic adhesion of CD8- positive cells to antibody-coated surfaces the initial step is independent of microfilaments and intracellular domains of cell-binding molecules. J Cell Biol. 1994;125:945–953. doi: 10.1083/jcb.125.4.945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Garcia AJ, Boettiger D. Integrinfibronectin interactions at the cell-material interface: initial integrin binding and signaling. Biomaterials. 1999;20:2427–2333. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(99)00170-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Taubenberger A, Cisneros DA, Friedrichs J, Puech PH, Muller DJ, Franz CM. Revealing early steps of α2β1 integrin-mediated adhesion to collagen type I by using single-cell force spectroscopy. Mol Biol Cell. 2007;18:1634–1644. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E06-09-0777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Curtis ASG. The mechanism of adhesion of cells to glass. J Cell Biol. 1964;20:199–215. doi: 10.1083/jcb.20.2.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Simson R, Wallraff E, Faix J, Niewöhner J, Gerish G, Sackmann E. Membrane bending modulus and adhesion energy of wild-type and mutant cells of Dictyostelium lacking talin or cortexillins. Biophys J. 1998;74:514–522. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(98)77808-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gingell D, Todd I, Bailey J. Topography of cell-glass apposition revealed by total internal reflection fluorescence of volume markers. J Cell Biol. 1985;100:1334–1338. doi: 10.1083/jcb.100.4.1334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Döbereiner HG, Dubin-Thaler B, Giannone G, Xenias HS, Sheetz MP. Dynamic phase transitions in cell spreading. Phys Rev Letters. 2004;93:108105. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.93.108105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ridley AJ, Schwartz MA, Burridge K, Firtel RA, Ginsberg MH, Borisy G, Parsons JT, Horwitz AR. Cell migration: integrating signals from front to back. Science. 2003;302:1704–1709. doi: 10.1126/science.1092053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Dalby MJ, Childs S, Riehle MO, HJ, Johnstone H, Affrossman S, Curtis ASG. Fibroblast reaction to island topography: changes in cytoskeleton and morphology with time. Biomaterials. 2003;24:927–935. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(02)00427-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pankov R, Endo Y, Even-Ram S, Araki M, Clark K, Cukierman E, Matsumoto K, Yamada KM. A Rac switch regulates random versus directionally persistent cell migration. J Cell Biol. 2005;170:793–802. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200503152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jones GE, Gillett R, Partridge T. Rapid modification of the morphology of cell contact sites during the aggregation of limpet haemocytes. J Cell Sci. 1976;22:21–33. doi: 10.1242/jcs.22.1.21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zidovska A, Sackmann E. Brownian motion of nucleated cell envelopes impedes adhesion. Phys Rev Letters. 2006;96:048103. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.96.048103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Pierres A, Benoliel AM, Touchard D, Bongrand P. How cells tiptoe on adhesive surfaces before sticking. Biophys J. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.125278. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Shao JY, Ting-Beall HP, Hochmuth RM. Static and dynamic lengths of neutrophil microvilli. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:6797–6802. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.12.6797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Evans E, Heinrich V, Leung A, Kinoshita K. Nano- to Microscale dynamics of P-selectin detachment from leukocyte interfaces. I. Membrane separation from the cytoskeleton. Biophys J. 2005;88:2288–2298. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.051698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Robert P, Limozin L, Benoliel AM, Pierres A, Bongrand P. Glycocalyx Regulation of Cell Adhesion. In: King MR, editor. Principles of Cellular Engineering. Amsterdam: Elsevier. Academic Press; 2006. pp. 143–169. [Google Scholar]

- 49.Patel KD, Nollert MU, McEver RP. P-selectin must extend a sufficient length from the plasma membrane to mediate rolling of neutrophils. J Cell Biol. 1995;131:1893–1902. doi: 10.1083/jcb.131.6.1893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Sabri S, Pierres A, Benoliel AM, Bongrand P. Influence of surface charges on cell adhesion: difference between static and dynamic conditions. Biochem Cell Biol. 1995;73:411–420. doi: 10.1139/o95-048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Soler M, Merant C, Servant C, Fraterno M, Allasia C, Lissitzky JC, Bongrand P, Foa C. Leukosialin (CD43) behavior during adhesion of human monocytic THP-1 cells to red blood cells. J Leukocyte Biol. 1997;61:609–618. doi: 10.1002/jlb.61.5.609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Leupin O, Zaru R, Laroche T, Müller S, Valitutti S. Exclusion of CD45 from the T-cell receptor signaling area in antigen-stimulated T lymphocytes. Current Biology. 2000;10:277–280. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(00)00362-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pierres A, Vitte J, Benoliel AM, Bongrand P. Dissecting individual ligand-receptor bonds with a laminar flow chamber. Biophys Rev Letters. 2006;1:231–257. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Robert P, Benoliel AM, Pierres A, Bongrand P. What is the biological relevance of the specific bond properties revealed by single molecule studies ? J Mol Recognition. 2007;20:432–447. doi: 10.1002/jmr.827. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Chen W, Evans EA, McEver RP, Zhu C. Monitoring receptor-ligand interactions between surfaces by thermal fluctuations. Biophys J. 2008;94:694–701. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.107.117895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Williams TE, Nagarajan S, Selvaraj P, Zhu C. Quantifying the impact of membrane microtopology on effective twodimensional affinity. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:13283–13288. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010427200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Pierres A, Touchard D, Benoliel AM, Bongrand P. Dissecting streptavidinbiotin interaction with a laminar flow chamber. Biophys J. 2002;82:3214–3223. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75664-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Pincet F, Husson J. The solution to the streptavidin-biotin paradox: the influence of history on the strength of single molecular bonds. Biophys J. 2005;89:4374–4381. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.067769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Marshall BT, Sarangapani KK, Lou J, McEver RP, Zhu C. Force history dependence of receptor-ligand dissociation. Biophys J. 2005;88:1458–1466. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.104.050567. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pierres A, Prakasam A, Touchard D, Benoliel AM, Bongrand P, Leckband D. Dissecting subsecond cadherin bound states reveals an efficient way for cells to achieve ultrafast probing of their environment. FEBS Lett. 2007;581:1841–1846. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2007.03.077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kung C. A possible unifying principle for mechanosensation. Nature. 2005;436:647–654. doi: 10.1038/nature03896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Luo BH, Carman CV, Springer TA. Structural basis of integrin regulation and signaling. Ann Rev Immunol. 2007;25:619–647. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.25.022106.141618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Horoyan M, Benoliel AM, Capo C, Bongrand P. Localization of calcium and microfilament changes in mechanically stressed cells. Cell Biophys. 1990;17:243–256. doi: 10.1007/BF02990720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Matthews BD, Overby DR, Mannix R, Ingber DE. Cellular adaptation to mechanical stress: role of integrins, rho, cytoskeletal tension and mechanosensitive ion channes. J Cell Sci. 2006;119:508–518. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02760. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Giancotti FG, Ruoslahti E. Integrin signaling. Science. 1999;285:1028–1032. doi: 10.1126/science.285.5430.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Burroughs NG, Lazic Z, van der Merwe PA. Ligand detection and discrimination by spatial relocalization: a kinase-phosphatase segregation model of TCR activation. Biophys J. 2006;91:1619–1629. doi: 10.1529/biophysj.105.080044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Bruinsma R, Behrisch A, Sackmann E. Adhesive switching of membranes: experiment and theory. Phys Rev E. 2000;61:4253–4267. doi: 10.1103/physreve.61.4253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Cukierman E, Pankov R, Stevens DR, Yamada KM. Taking cell-matrix adhesions to the third dimension. Science. 2001;294:1708–1712. doi: 10.1126/science.1064829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Mao Y, Schwarzbauer JE. Stimulatory effects of a three-dimensional microenvironment on cell-mediated fibronectin fibrillogenesis. J Cell Sci. 2005;118:4427–4436. doi: 10.1242/jcs.02566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jiang H, Grinnell F. Cell-matrix entanglement and mechanical anchorage of fibroblasts in three-dimensional collagen matrices. Mol Biol Cell. 2005;16:5070–5076. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05-01-0007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]