Abstract

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA) is among the most lethal human cancers, in part because it is insensitive to many chemotherapeutic drugs. Studying a mouse model of PDA that is refractory to the clinically used drug gemcitabine, we found that the tumors in this model were poorly perfused and poorly vascularized, properties that are shared with human PDA. We tested whether the delivery and efficacy of gemcitabine in the mice could be improved by co-administration of IPI-926, a drug that depletes tumor-associated stromal tissue by inhibiting the Hedgehog cellular signaling pathway. The combination therapy produced a transient increase in intratumoral vascular density and intratumoral concentration of gemcitabine, leading to transient stabilization of disease. Thus, inefficient drug delivery may be an important contributor to chemoresistance in pancreatic cancer.

Pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDA) is among the most intractable of human malignancies. Decades of effort have witnessed the failure of many chemotherapeutic regimens and the current standard-of-care therapy, gemcitabine, extends patient survival by only a few weeks (1–3). Oncology drug development relies heavily on mouse models bearing transplanted tumors for efficacy testing of novel agents. However, such models of PDA respond to numerous chemotherapeutic agents, including gemcitabine (4–9), suggesting that their predictive utility may be limited. Genetically engineered mouse (GEM) models of PDA offer an alternative to transplantation models for preclinical therapeutic evaluation. We have previously described KPC mice, which conditionally express endogenous mutant Kras and p53 alleles in pancreatic cells (10), and which develop pancreatic tumors whose pathophysiological and molecular features resemble those of human PDA (11). Here we have used the KPC mice to investigate why PDA is insensitive to chemotherapy.

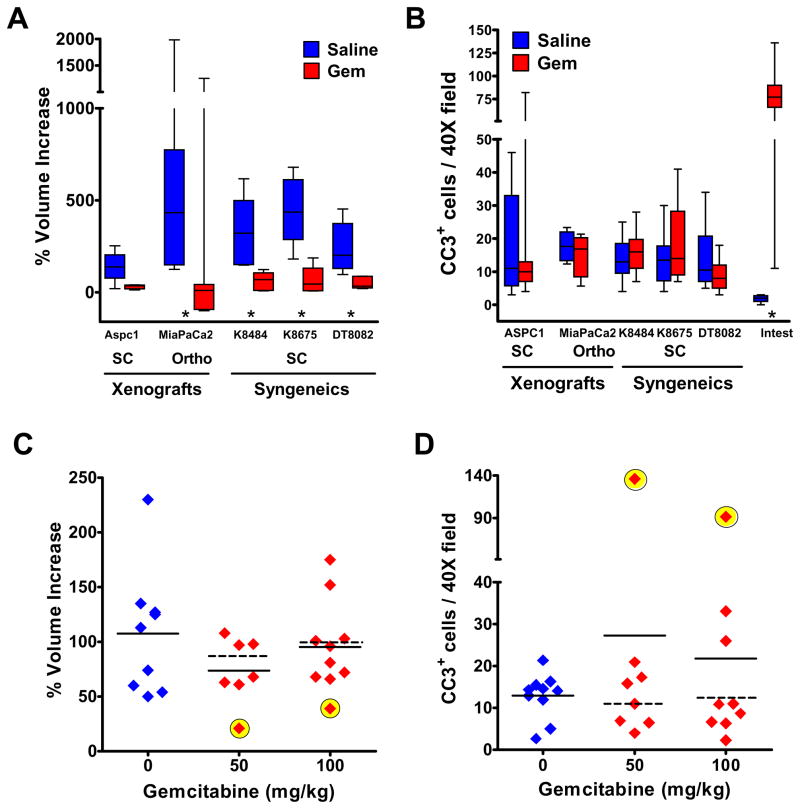

We first compared the effect of gemcitabine on the growth of pancreatic tumors in four mouse models: the KPC mice and three distinct tumor transplantation models (12)(13). Gemcitabine inhibited the growth of all transplanted tumors, irrespective of their human or mouse origin (Fig. 1A), but did not induce apoptosis (Fig. 1B). Rather, proliferation was substantially reduced in all transplanted tumors (fig. S1A). In contrast, most KPC tumors (15/17) in gemcitabine-treated mice showed the same growth rate as in saline-treated controls (Fig. 1C). This is consistent with clinical results wherein only 5–10% of patients treated with gemcitabine demonstrate an objective radiographic response at the primary tumor site (3). Two KPC tumors demonstrated a transient response by high resolution ultrasound (13), which correlated with high levels of apoptosis (Fig. 1D)(fig S1). Additionally, proliferation was diminished in gemcitabine-treated KPC tumors shortly after treatment, but to a lesser extent than in transplantation models (fig. S1).

Fig. 1. Pancreatic tumors in KPC mice are largely resistant to gemcitabine.

Mice bearing pancreatic tumors were treated systemically with gemcitabine. * P< .05, Mann-Whitney U. Solid lines = mean; dashed lines = mean without responders. (A) Percent change in tumor volume in transplantation models (see Supplementary Online Material) treated with saline (blue) or 100mg/kg gemcitabine, Q3Dx4 (red). (B) Gemcitabine treatment did not induce tumor cell apoptosis in the transplantation models, as measured by immunohistochemistry (IHC) for cleaved caspase 3 (CC3). (C) Percent change in volume of tumors in KPC mice treated with saline (blue), 50mg/kg (green) or 100mg/kg of gemcitabine, Q3Dx4 (red). Two of seventeen KPC tumors responded transiently to gemcitabine, as assessed by ultrasonography (yellow). (D). Increased apoptosis was evident only in the KPC tumors that transiently responded to the drug (yellow).

Transplantation of low-passage cells derived from KPC tumors yielded subcutaneous tumors that were sensitive to gemcitabine treatment (see “Syngeneics”, Fig 1A), suggesting that innate cellular differences is unlikely to explain the chemoresistance of KPC tumors. We therefore assessed the metabolism of gemcitabine (2′,2′-difluorodeoxycytidine, dFdC) to its active, intracellular metabolite, gemcitabine triphosphate (2′,2′-difluorodeoxycytidine triphosphate, dFdCTP), by high pressure liquid chromatography (HPLC). Consistent with the results of clinical studies (14), circulating gemcitabine in wild-type mice was rapidly deaminated to its inactive metabolite, 2′2′-difluorodeoxyuridine (dFdU), resulting in a short half-life for gemcitabine (fig. S2A-B). dFdCTP was present in transplanted tumor tissues and control tissues, but was undetectable in KPC tumors (table S1). Thus, dFdCTP accumulation in pancreatic tumor tissue distinguished transplantation and KPC models of PDA and correlated with the responsiveness to gemcitabine. Changes in expression of genes involved in gemcitabine transport are unlikely to explain the difference in gemcitabine accumulation in transplanted and KPC pancreatic tumors (fig S2C-D).

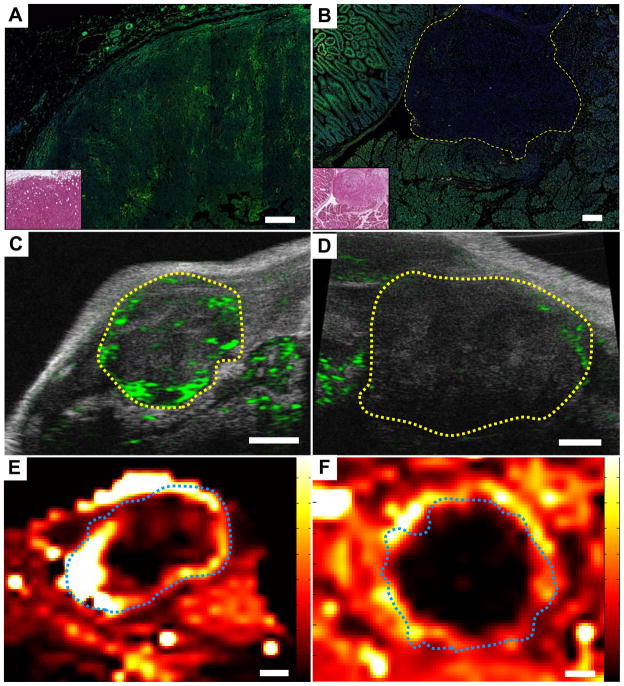

Impaired drug delivery is another possible mechanism of chemoresistance (15, 16). We investigated drug delivery by characterizing tumor perfusion in each model. First we delineated functional vasculature through the intravenous infusion of a plant lectin (L. esculentum) in anesthetized mice, followed by the coimmunofluorescent detection of blood vessels in harvested tissues with a CD31 antibody (fig. S3). We found that transplanted tumors demonstrated a patent vasculature, whereas KPC tumors had a dysfunctional vasculature. Indeed, only 32% of CD31+ blood vessels in KPC tumors were labeled with lectin, compared to 78% and 100% of vessels in transplanted tumors and normal pancreas, respectively. Second, to evaluate whether intravascular delivery and penetration of small molecule drugs is impeded in KPC tumors, we intravenously co-administered lectin with the autofluorescent drug doxorubicin (Figs. 2A-B)(fig. S4)(17). Confocal microscopy revealed a marked decrease in doxorubicin delivery to KPC pancreatic tumors compared to adjacent control tissues and transplanted tumors, confirming inefficient drug delivery over a short time-course. Third, using high resolution contrast ultrasound, we found that the delivery of 5μm gas-filled liposomes (microbubbles) was more efficient in transplanted tumors than KPC tumors (Figs. 2C-D)(fig. S5). Finally, we performed dynamic contrast enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (DCE-MRI) on transplanted and KPC tumors (Fig. 2E-F)(fig. S6). Following administration of gadolinium-diethyltriaminepentaacetic acid (Gd-DTPA), we observed significant enhancement (of what???) in the periphery of transplanted tumors, while the tumor cores exhibited a variable, heterogeneous pattern of enhancement, consistent with the central necrosis observed by histology (fig. S6C). In contrast, we observed efficient delivery of Gd-DTPA to the tissues surrounding KPC tumors, with little or no enhancement (of what??) within the tumor body, despite little necrosis in these tumors (fig S6D). Collectively, these results suggest that drug delivery is impaired in KPC pancreatic tumors.

Fig. 2. Pancreatic tumors in KPC mice are poorly perfused.

Direct immunofluorescent detection of plant lectin (red) and doxorubicin (green) infused into transplanted (A) and KPC (B) tumors, along with H&E stained adjacent sections (inset). Scale bar, 200μm. Doxorubicin was effectively delivered to transplanted tumors (N=5), but poorly delivery to KPC tumors (N=4), relative to surrounding tissue. Perfusion of microbubbles (green) into transplanted (C) and KPC (D) tumors visualized by contrast ultrasonography. Transplanted tumors were well perfused (N=6) compared to KPC tumors (N=8). Tumors outlined in yellow. Scale bars, 1mm. DCE-MRI demonstrated increased perfusion and extravasation of Gd-DTPA (high delivery = white/yellow) in transplanted tumors (E, N=6) compared to KPC tumors (F, N=6). Tumors outlined in blue. Scale bars, 2mm.

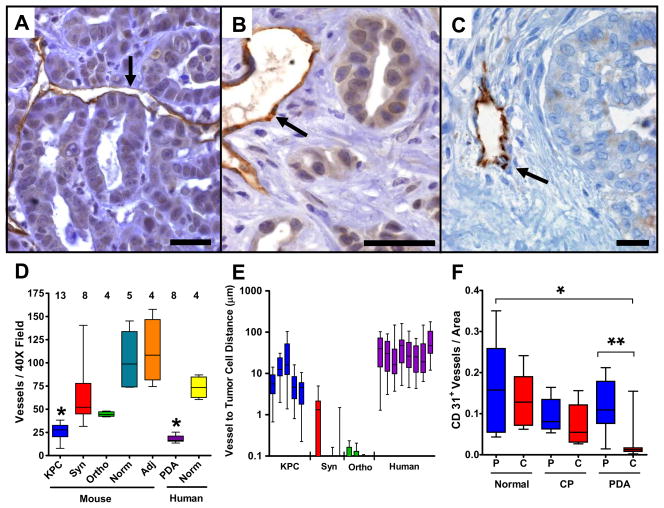

We next investigated the vascular content and tissue architecture in transplanted and KPC tumors. The viable (peripheral) portions of transplanted tumors were densely vascularized (fig. S7A) and neoplastic cells made direct contact with blood vessels (Fig. 3A). In contrast, within the parenchyma of KPC and human pancreatic tumors, blood vessel density was markedly decreased and vessels were embedded within the prominent stromal matrix that is characteristic of these tumors and of primary human ductal pancreatic cancer (Figs. 3B-D)(fig. S7)(fig. S8). Neoplastic cells in both KPC and human pancreatic tumors were widely spaced from blood vessels compared to those in transplanted tumors, reflecting these differences in stromal content (Fig. 3E). Using computer aided image analysis, we confirmed the paucity of vasculature in an independent cohort of 18 human PDA specimens, compared to normal pancreatic tissues and chronic pancreatitis (CP) samples (Fig. 3F)(fig S9). Our findings demonstrate that increased vascular content is not a prerequisite for ductal pancreatic cancer progression and suggest that the hypovascularity and vascular architecture of PDA tumors may impose an additional limitation to therapeutic delivery.

Fig. 3. Pancreatic tumors in KPC mice and humans have diminished vascularity.

CD31 IHC from transplanted (A), KPC (B) and human (C) pancreatic tumors (scale bar, 20μm). Arrows denote blood vessels. Neoplastic cells from transplanted tumors made direct contact with blood vessels while those in KPC and human tumors were more distantly spaced due to prominent stroma. (D) Mean Vessel Density (MVD) was measured in KPC tumors (KPC), syngeneic autografts (Syn), orthotopic xenografts (Ortho), adjacent surrounding tissues in KPC tumors (Adj), human pancreatic tumors (PDA) and normal pancreas from mice and humans (Norm). KPC and human pancreatic tumors were poorly vascularized compared to transplanted tumors and normal tissues (* P<.004, Mann-Whitney U). (E) The distance separating blood vessels and neoplastic cells was significantly higher in KPC tumors and human PDA than in transplanted tumors. (F) Computer-aided image analysis of MVD found human pancreatic tumors (N=18) to be poorly vascularized compared to normal pancreas (N=5) and chronic pancreatitis (N=5) samples (* P<.0015, ** P<.0001, Mann-Whitney U). Peripheral (P) and central (C) regions of tissues were distinguished.

We hypothesized that disrupting the stroma of pancreatic tumors might alter the vascular network and thereby facilitate delivery of chemotherapeutic agents. We studied an inhibitor of the hedgehog (Hh) pathway because paracrine Hh signaling from neoplastic cells to stromal cells promotes stromal desmoplasia (18, 19). Binding of Hh ligands to the Patched1 receptor relieves repression of the 12-transmembrane protein Smoothened (Smo), resulting in activation of the Gli family of transcription factors. While Sonic Hedgehog (Shh) is overexpressed in the neoplastic cells of both human (20) and KPC (10) pancreatic tumors, Gli activity is restricted to the stromal compartment (21).

IPI-926 is a semisynthetic derivative of cyclopamine (chemical structure shown in fig. S10) that potently inhibits Smo (EC50= 7nM) with a long half life (10.5 hours, CD1 mice) and a high volume of distribution (11L/kg, CD1 mice). The detailed characterization of IPI-926 in cell-based and in vitro assays will be published separately. Daily oral administration of 40mg/kg IPI-926 to KPC mice resulted in a measurable accumulation of drug in PDA tissues (fig. S11A) and a significant decrease in the expression of Gli1, a transcriptional target of the Hh pathway (fig. S11B). The effects of Smo inhibition on tumor histopathology and perfusion were investigated in KPC mice after 8–12 days of treatment with IPI-926 or gemcitabine, alone or in combination (IPI-926/gem). In contrast to mice treated with vehicle or gemcitabine, which exhibited profuse desmoplastic tumor stroma, mice treated with IPI-926 or IPI-926/gem were depleted of desmoplastic stroma, resulting in densely packed ductal tumor cells (fig. S12A-D). The effect of Smo inhibition on the stroma was also evidenced by a decrease in Collagen I content (fig. S12E-H). Interestingly, these differences were not apparent in mice treated for only four days (fig. S13I-L). However, coimmunofluorescence performed on tumors treated for four days with vehicle or IPI-926 found reduced proliferation in α-smooth muscle actin (αSMA) positive stromal myofibroblasts (fig. S11C)(fig S13A-B). This decrease in proliferation was balanced by an increase in proliferation of αSMA negative cells (fig. S11D).

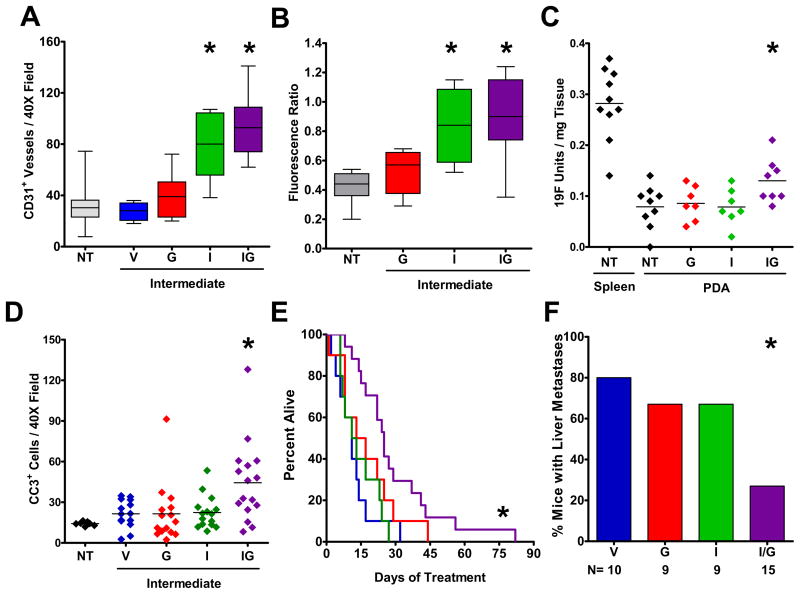

Smo inhibition also had a profound effect on the tumor vasculature, with a significantly higher mean vessel density (MVD) noted in the tumors from IPI-926 treated mice (Fig. 4A)(figs. S14A-D). This effect was most significant in IPI-926/gem treated mice, where the MVD approximated that of normal pancreatic tissue. An increased CD31 content was also present after four days of treatment (fig. S14E-H). At this early timepoint, numerous isolated CD31 positive cells were noted, consistent with the active formation of new endothelial precursors after Smo inhibition. Indeed, coimmunofluorescence for proliferation and endothelial markers confirmed a significant increase in proliferating endothelial cells following IPI-926 treatment (fig. S11E)(fig. S13C,D). The increased MVD observed in IPI-926 treated mice also correlated with more effective delivery of doxorubicin to tumor tissues (Fig. 4B)(fig. S14I-L). Importantly, we found that the concentration of gemcitabine metabolites in KPC tumors was elevated by 60% following 10 days pretreatment with IPI-926/gem (Fig. 4C)(P=.04, Mann-Whitney U). These data suggest that depletion of pancreatic tumor stroma stimulates angiogenesis and consequently augments drug delivery. Interestingly, whole tissue mRNA microarray analysis revealed no significant differences in proangiogenic VEGF expression between what and what????(table S2).

Fig. 4. Smoothened inhibition facilitates gemcitabine delivery and extends survival.

KPC mice were treated for 8–12 days with: no treatment (NT), vehicle (V), gemcitabine (G), IPI-926 (I), or IPI-926 + gemcitabine (IG). (A) MVD was elevated following IPI-926 or IPI-926/Gem treatment (P<.05, Mann-Whitney U). (B) Doxorubicin fluorescence was elevated following IPI-926 alone or IPI-926/Gem treatment (*P<.02, Mann-Whitney U). (C) Following treatment with the indicated regimens, all mice were administered a single dose of gemcitabine and the concentration of fluorine-bearing metabolites was determined in extracted samples by 19F NMR. Gemcitabine metabolite concentration was elevated in IPI-926/gem treated tumors (P=.04, Mann-Whitney U). (D) IHC for cleaved caspase 3 revealed increased apoptosis in IPI-926/gem treated tumors (P=.008, Mann-Whitney U). (E) IPI-926/gem treatment significantly extended survival in KPC mice (P=.001 Log-Rank Test, Hazard Ratio = 0.157 ± 0.458 95%CI 6.36). (F) Fewer liver metastases were observed in IPI-926/gem KPC mice (*P=.015, Fisher’s Exact).

We then investigated the effects of Smo inhibition on cell proliferation and apoptosis. Although IPI-926 alone specifically decreased the proliferation of stromal myofibroblasts, it had little effect on overall cellular proliferation, consistent with the finding that conditional Smo deletion in pancreatic cells does not alter the progression of mutant Kras-induced pancreatic tumors (23). Importantly, IPI-926/gem treated tumors harbored many dead and dying cells as evidenced by a significant increase in staining for the apoptotic marker Cleaved Caspase 3 (Fig. 4D).

Finally, we performed an intervention survival study on KPC mice, monitoring tumor volume bi-weekly by 3D-ultrasonography. KPC mice treated with gemcitabine alone or IPI-926 alone showed no survival benefit in comparison with vehicle-treated controls. In contrast, combination treatment with IPI-926/gem extended the median survival of KPC mice from 11 days to 25 days (P= .001, Log Rank Test), yielding a hazard ratio of 0.157 ±0.458 95%CI (Fig. 4E). Most IPI-926/gem-treated tumors (14/17) exhibited a transient decrease in size within 1–2 weeks of treatment (fig. S15). In contrast, only a minority of gemcitabine (2/10) and IPI-926 (2/10) treated mice demonstrated objective ultrasonographic responses to treatment. Interestingly, IPI-926/gem treatment resulted in a significant decrease in metastases to the liver (Fig. 4F, P=.015, Fisher’s Exact). Investigating the biology of tumors at endpoint, we found no differences in the expression of genes associated with gemcitabine resistance in IPI-926/gem treated tumors (fig. S11G). However, the hypovascularity of IPI-926/gem treated tumors was restored at endpoint as the MVD in IPI-926 was similar to controls (fig. S11H).

The general resistance of pancreatic cancer to systemic therapies is unusual among common carcinomas and was not predicted by preclinical models (24). Chemotherapeutic agents share two properties: a short half-life and small therapeutic index (the range of concentration between efficacy and toxicity). Poor tissue perfusion will necessarily produce a substantial decrease in total exposure to drugs with a short half-life. We hypothesize that pancreatic tumors are poorly perfused relative to normal tissues and other tumors and that this is due to aspects of tumor architecture unique to the KPC model and to human PDA. Indeed, two groups have recently reported that human pancreatic ductal adenocarcinomas are poorly perfused using contrast-enhanced endoscopic ultrasound and that this feature distinguishes PDA from endocrine tumors and inflammatory diseases of the pancreas (25, 26). A deficient, non-angiogenic vasculature that limits drug delivery may also help explain why patients with pancreatic cancer show a poor response to anti-VEGF therapy (27).

To counteract this barrier to drug delivery, we propose that agents with a long half-life and a high therapeutic index should be the focus of preclinical investigations in pancreatic cancer. We have provided a proof-of-principle that a drug that disrupts a proposed determinant of poor perfusion in PDA, the desmoplastic stroma, can facilitate the delivery and enhance the efficacy of gemcitabine. Unexpectedly, this drug – which inhibits the Hh signaling pathway through effects on Smo -- also increased tumor vascular density, contrasting with earlier work demonstrating a pro-angiogenic role for Hh signaling during development and in adults (28, 29). Ultimately, the vascular content of KPC tumors returned to lower levels, suggesting that the tumors can adapt to continued Smo inhibition. Although most of the tumors in KPC mice likewise resumed growth after a transient response, our results nonetheless may open new avenues for improving the delivery and efficacy of therapeutics in patients with pancreatic cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the animal care staffs of the CRI, UPENN TRL, FHCRC and University Hospital Dresden as well as the histology core at CRI. This research was funded by the Lustgarten Foundation, the University of Cambridge and Cancer Research UK, The Li Ka Shing Foundation and Hutchison Whampoa, and the NIH (CA101973, CA111292, CA084291, and CA105490) to DAT; and, CA15704 to SRH. SRH was supported by a grant from the Mead Foundation. Preliminary studies were supported by a grant from the UPenn/GSK ADDI. KPO and KF were supported by the NIH under Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award F32CA123939-02 (KPO) and F32CA123887-01 (KF).

References and Notes

- 1.Li D, Xie K, Wolff R, Abbruzzese JL. Lancet. 2004 Mar 27;363:1049. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)15841-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Burris HA, 3rd, et al. J Clin Oncol. 1997 Jun;15:2403. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1997.15.6.2403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tempero M, et al. J Clin Oncol. 2003 Sep 15;21:3402. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.09.140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bruns CJ, et al. Int J Cancer. 2002 Nov 10;102:101. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shimamura T, et al. Cancer Res. 2007 Oct 15;67:9903. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-4558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Verma A, et al. Clin Cancer Res. 2008 Apr 15;14:2476. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duan JX, et al. J Med Chem. 2008 Apr 24;51:2412. doi: 10.1021/jm701028q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Melisi D, et al. Mol Cancer Ther. 2008 Apr;7:829. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-0337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schultz RM, et al. Oncol Res. 1993;5:223. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hingorani SR, et al. Cancer Cell. 2005 May;7:469. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.04.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hruban RH, et al. Cancer Res. 2006 Jan 1;66:95. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-2168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cook N, Olive KP, Frese K, Tuveson DA. Methods Enzymol. 2008;439:73. doi: 10.1016/S0076-6879(07)00406-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Materials and methods are available as supporting material on Science Online.

- 14.Abbruzzese JL, et al. J Clin Oncol. 1991 Mar;9:491. doi: 10.1200/JCO.1991.9.3.491. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tredan O, Galmarini CM, Patel K, Tannock IF. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2007 Oct 3;99:1441. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djm135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Minchinton AI, Tannock IF. Nat Rev Cancer. 2006 Aug;6:583. doi: 10.1038/nrc1893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Egorin MJ, Hildebrand RC, Cimino EF, Bachur NR. Cancer Res. 1974 Sep;34:2243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yauch RL, et al. Nature. 2008 Sep 18;455:406. doi: 10.1038/nature07275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bailey JM, et al. Clin Cancer Res. 2008 Oct 1;14:5995. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-0291. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Thayer SP, et al. Nature. 2003 Oct 23;425:851. doi: 10.1038/nature02009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tian H, et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009 Feb 25; [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tremblay, et al. J Med Chem. Submitted. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nolan-Stevaux O, et al. Genes Dev. 2009 Jan 1;23:24. doi: 10.1101/gad.1753809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Johnson JI, et al. Br J Cancer. 2001 May 18;84:1424. doi: 10.1054/bjoc.2001.1796. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sofuni A, et al. J Gastroenterol. 2005 May;40:518. doi: 10.1007/s00535-005-1578-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sakamoto H, et al. Ultrasound Med Biol. 2008 Apr;34:525. doi: 10.1016/j.ultrasmedbio.2007.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Cutsem E, et al. J Clin Oncol. 2009 Mar 23; [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pola R, et al. Nat Med. 2001 Jun;7:706. doi: 10.1038/89083. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Langer SJ, Ghafoori AP, Byrd M, Leinwand L. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002 Jul 15;30:3067. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkf421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.