Abstract

In this article, we describe the development and preliminary results of our new designed C2-symmetric bis-hydroxamic acid (BHA) ligands and the application of the new ligands for vanadium-catalyzed asymmetric epoxidation of allylic alcohols as well as homoallylic alcohols. From this success we demonstrate the versatile nature of BHA in the molybdenum catalyzed asymmetric oxidation of unfunctionalized olefins and sulfides.

1. Introduction

Today, the rapidly developing small molecule, chiral technology industry is witnessing a flurry of activity. While traditional methods of chiral production such as resolution and chiral pool chemistry are firmly established, emerging asymmetric catalyses are generating strong interest and are the focus of intensive research. Among these, asymmetric oxidation is one of the most important processes for drug synthesis.

Enantiomerically enriched epoxides, which are versatile building blocks for the synthesis of natural products and biologically active substances, could be provided by many efficient protocols,1 especially by the Sharpless asymmetric epoxidation that applied the chiral titanium-tartarate complex as the catalyst.2 Our studies began with the intention that it would be more practical of this type of protocol if the following conditions could be fulfilled: 1) ligand design to achieve high enantioselectivities for wide scope of allylic and homoallylic alcohols, 2) low catalyst loading (such as 1 mol%), 3) mild reaction conditions at 0°C to RT for fewer hours, 4) application of commercial available aqueous TBHP (tert-butyl hydroperoxide) or CHP (cumene hydroperoxide) as an achiral oxidant instead of anhydrous TBHP, and 5) easy work-up procedure for obtaining small epoxy alcohols with high purity.3–6

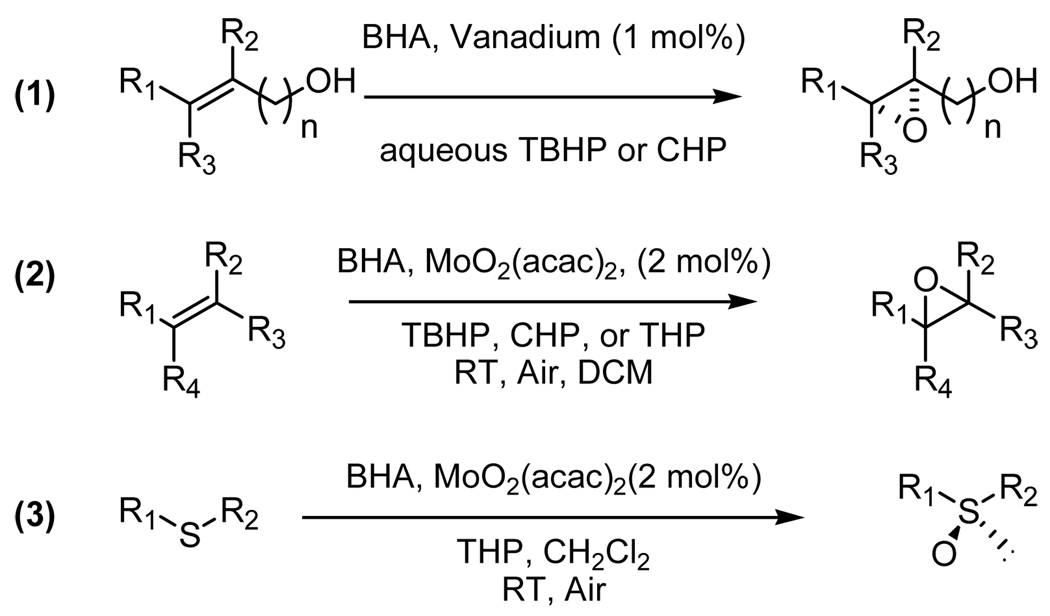

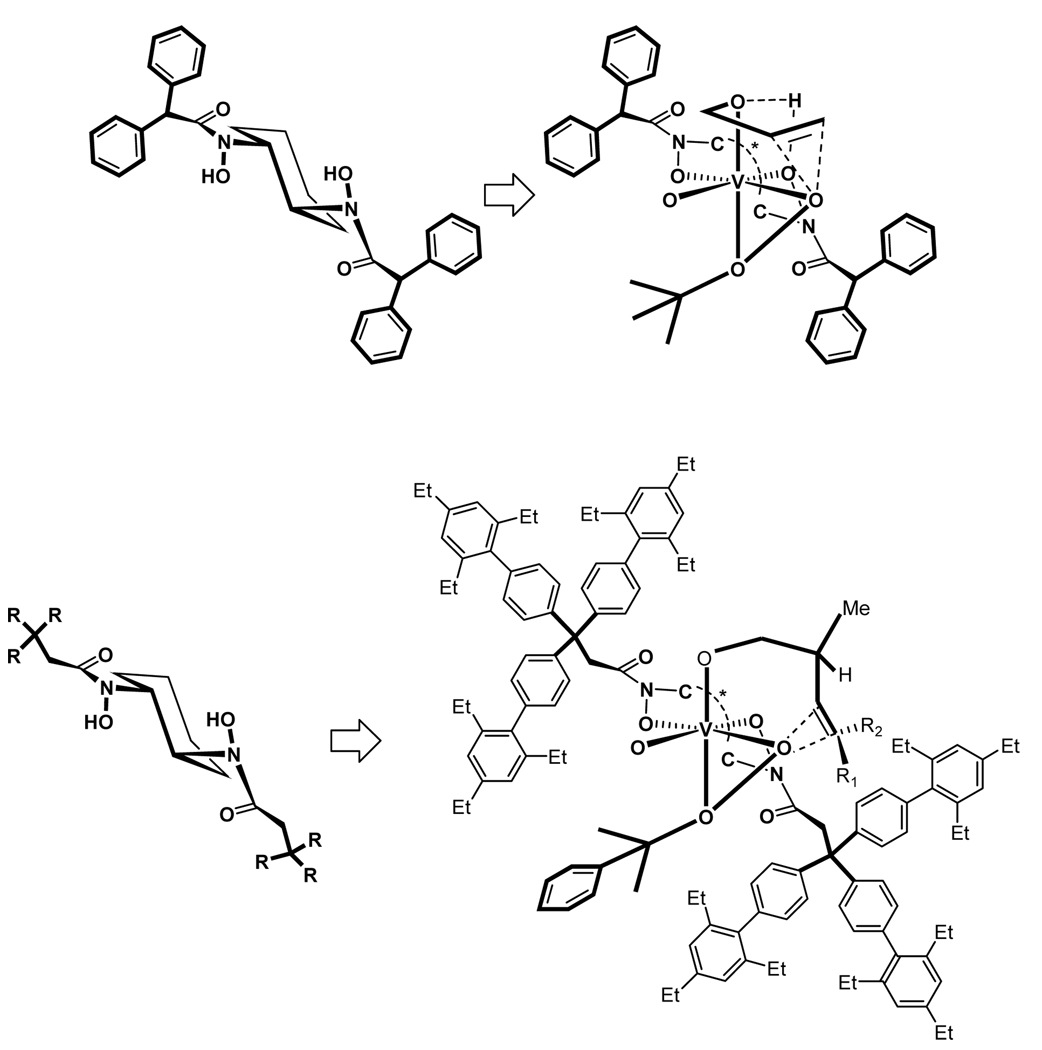

Recently, a series of chiral hydroxamic acid ligands have been developed by our group. These ligands were demonstrated to be effective for the vanadium-catalyzed asymmetric epoxidation of allylic alcohols. The success of the catalyst design comes from the design of C2-symmetric bis-hydroxamic acid (BHA) ligand. The new BHA design has accomplished the asymmetric oxidation of allylic alcohols,7 homoallylic alcohols,8 unfunctionalized olefins,9 and sulfides10 (Scheme 1). BHA metal complexes can serve as a new and versatile tool for asymmetric oxidation in modern organic synthesis. In this article we describe the development and preliminary results of the BHA leading to the versatile nature of the BHA.

Scheme 1.

BHA metal complexes asymmetric oxidation reactions.

2. Results and discussion

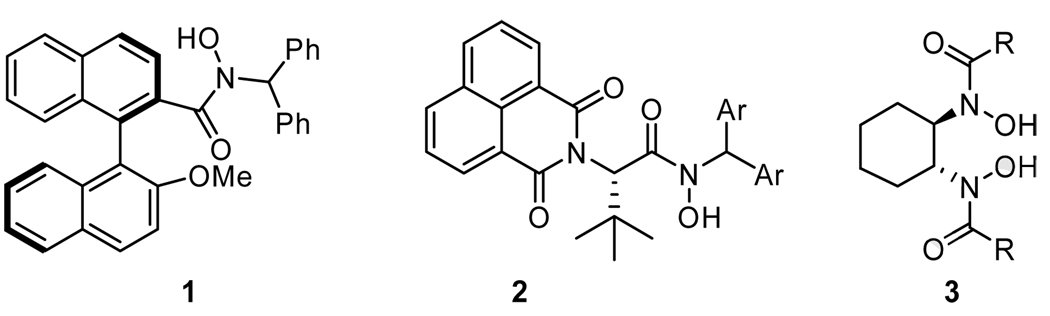

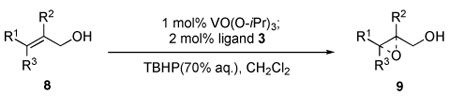

Recently, a series of chiral hydroxamic acid ligands have been developed by our group.11–13 These ligands were demonstrated to be effective for the vanadium-catalyzed asymmetric epoxidation of allylic and homoallylic alcohols (Scheme 2). These results suggested that several structural features of the hydroxamic acid were very suitable to generate reactive complex with vanadium and the complex significantly enhanced the enantioselectivities of the epoxy alcohols. However, the ligand deceleration effect was still observed in these cases.11,12,14 To exclude this effect, we planned to design a new C2-symmetric BHA incorporating several features: 1) with an additional binding site, 3 is capable of chelating as an bi-dentate ligand to the metal center to complete the generation of chiral vanadium-ligand complex more efficiently than monohydroxamic acid 1 and 2; 2) when the R group of amide in 3 is sufficiently large, it will direct the amide carbonyl oxygen towards the cyclohexane ring to minimize steric interaction and restrict its coordination with the metal. A second aspect is that the attachment of additional ligands to vanadium will also be restricted for steric reasons. Thus, doubly or triply coordinated species, which are believed to be inactive, should not be generated with this bis-hydroxamic acid ligand, and consequently the ligand deceleration effect with the vanadium-3 catalyst system should not be problematic.

Scheme 2.

Hydroxamic acid ligands.

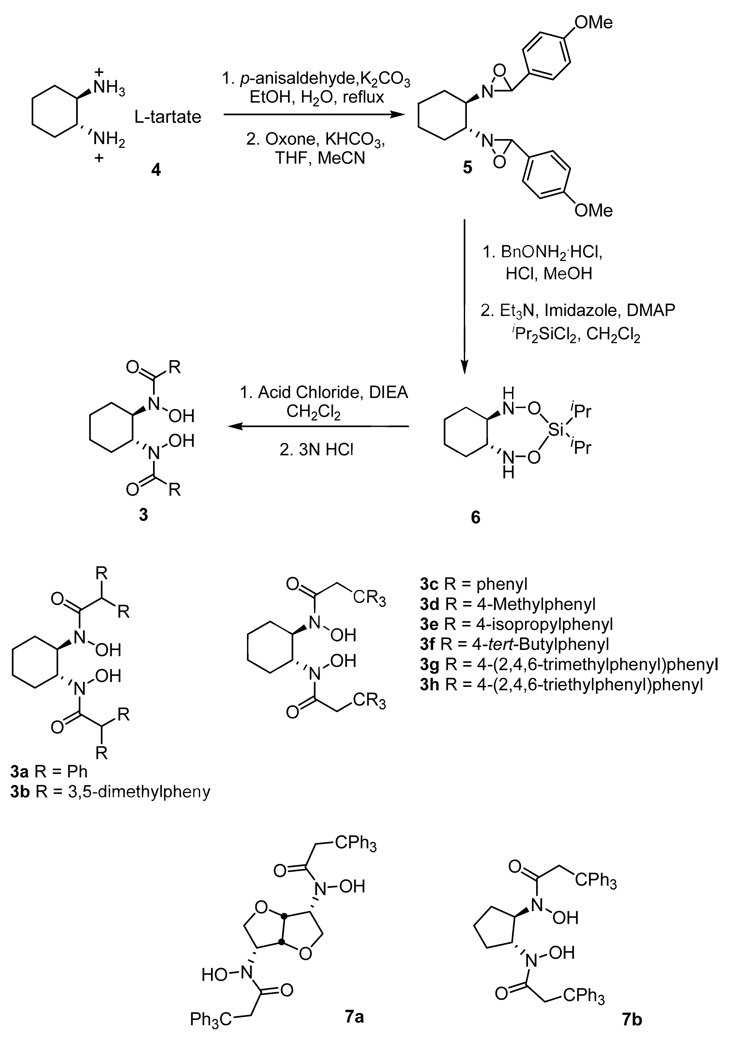

2.1. Synthesis of BHA ligands

To prove the veracity of our hypothesis, we devised a synthetic protocol for C2-symmetric BHA 3 from readily available chiral diamine tartrate salt (Scheme 3). These reaction sequences can be conducted with satisfactory yield for every step to provide 6, which is used to react with different acid chlorides to provide our designed ligands. Based on this protocol, we have prepared a wide array of diverse ligands 3 and several of them have been demonstrated to be highly efficient to the vanadium catalyzed asymmetric epoxidation reaction (Scheme 3).7,8

Scheme 3.

Preparation of BHA ligands.

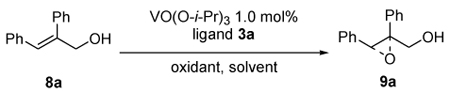

2.2. Asymmetric epoxidation of allylic alcohol

Our first ligand 3a was tested for the vanadium catalyzed asymmetric epoxidation of allylic alcohol 8a (Table 1). The complex, which was generated with different ratio of ligand 3a to VO(O-iPr)3, was applied as the catalyst to perform the epoxidation in toluene in the presence of aqueous TBHP. Similar yields and ee values were provided even if the ratio of ligand to vanadium was increased to 3:1, which have shown us that the negative effect of dynamic ligand exchange was not observed in the vanadium-bis-hydroxamic acid catalyst system (entry 1–6).11,12,14 We then performed the reaction with 1mol% of vanadium reagent and 2mol% of ligand 3a in different solvent and CH2Cl2 was the best one for both high yield and enantioselectivity (entry 7–10). Use of anhydrous TBHP increased neither yield nor ee value (entry 12) and slow reactivity was surmounted by performing the epoxidation at 0�C or room temperature without significant loss of enantioselectivity (entry 7,14). When catalyst loading was decreased to 0.2 mol%, both reactivity and enantioselectivity were kept, which confirmed the high efficiency of our chiral catalyst.

Table 1.

Modification of conditions for asymmetric epoxidation of allylic alcohols

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry[a] | ratio[b] | solvent | temp, time | (%)yield[c] | (%)ee[d], | config.[e] |

| 1 | 1:1 | toluene | rt, 6h | 96 | 90, | (2R, 3R) |

| 2 | 2:1 | toluene | rt, 6h | 96 | 92, | (2R, 3R) |

| 3 | 3:1 | toluene | rt, 6h | 95 | 93, | (2R, 3R) |

| 4 | 1:1 | toluene | 0°C, 15h | 90 | 93, | (2R, 3R) |

| 5 | 2:1 | toluene | 0°C, 15h | 87 | 94, | (2R, 3R) |

| 6 | 3:1 | toluene | 0°C, 15h | 84 | 93, | (2R, 3R) |

| 7 | 2:1 | CH2Cl2 | 0°C, 12h | 93 | 94, | (2R, 3R) |

| 8 | 2:1 | CHCl3 | 0°C, 12h | 95 | 83, | (2R, 3R) |

| 9 | 2:1 | acetone | 0°C, 12h | 48 | 85, | (2R, 3R) |

| 10 | 2:1 | ethyl acetat | 0°C, 12h | 93 | 92, | (2R, 3R) |

| 11[f] | 2:1 | CH2Cl2 | 0°C, ~rt | 95 | 93, | (2R, 3R) |

| 12[g] | 2:1 | CH2Cl2 | 0°C, 12h | 91 | 94, | (2R, 3R) |

| 13[h] | 2:1 | CH2Cl2 | 0°C, 12h | 90 | 95, | (2R, 3R) |

| 14 | 2:1 | CH2Cl2 | −20°C, 48h | 91 | 97, | (2R, 3R) |

All reactions were carried out in the presence of 1.5 equiv of tert-butylhydroperoxide (TBHP) (70% aqueous solution) unless otherwise indicated.

Ratio was the mol ratio of ligand 3a to the VO(O-i-Pr)3 when VO(O-i-Pr)3 was 1.0 mol% of substrate in the reaction

Isolated yield after chromatographic purification.

Ee values were determined by either chiral HPLC or chiral GC and the detailed information was provided in our published paper. 7

Determined by comparison of reported optical rotation.

0.2 mol% VO(O-i-Pr)3 and 0.4 mol% ligand was used, reaction was performed at 0 °C for 6 h and then warmed to rt to complete the conversion.

3.5 M TBHP in dichloromethane was used.

VO(acac)2 was used.

With the modified reaction conditions and several designed ligands in hand; we then performed the epoxidation of a wide scope of allylic alcohols in CH2Cl2 with 1mol% of vanadium reagent and 2mol% of 3. As expected, the complex of vanadium with 3 provided epoxy alcohols with both high enantioselectivities and good yields (Table 2). The catalyst derived from vanadium and 3a invariably induced excellent enantioselectivity during the epoxidation of trans-disubstituted and trisubstituted allylic alcohols. The most gratifying aspect of this catalyst system was the excellent enantioselectivity during epoxidation of cis-substituted allylic alcohols with catalyst derived from vanadium and 3b. Reactions were performed under air at 0°C to −20°C with aqueous solution of TBHP to obtain all the above results.7

Table 2.

Asymmetric epoxidation of allylic alcohols

| |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry[a] | epoxy alcohol | ligand | temp, time | yield[b] (%) |

ee[c] (%), |

config[d]. | |||

| 1 | 9b | 3a | −20°C, 48h | 84 | 97, | (2R, 3R) | |||

| 2 | 9c | 3a | −20°C, 60h | 53 | 97, | (2R, 3R) | |||

| 3 | 9d | 3a | −20°C, 72h | 56 | 95, | (2R, 3R) | |||

| 4 | 9e | 3a | −20°C, 72h | 51 | 95, | (2R, 3R) | |||

| 5 | 9f | 3a | 0°C, 12h | 73 | 95, | (R) | |||

| 6 | 9g | 3a | −20°C, 48h | 79 | 95, | (2R, 3R) | |||

| 7 | 9h | 3c | 0°C, 72h | 60 | 95, | (2R, 3S) | |||

| 8 | 9i | 3c | −20°C, 5d | 24 | 97, | (2R, 3S) | |||

| 9 | 9j | 3c | −20°C, 48h | 64 | 96, | (2R, 3R) | |||

| 10 | 9k | 3c | −20°C, 48h | 62 | 95, | (2R, 3S) | |||

| 11 | 9l | 3b | −20°C, 48h | 68 | 95, | (2R, 3R) | |||

All reactions were carried out in dichloromethane in the presence of 1.5 equiv of tert-butylhydroperoxide (TBHP) (70% aqueous solution) unless otherwise indicated.

Isolated yield after chromatographic purification.

Ee values were determined by either chiral HPLC or GC and the detailed information was provided in our published paper.7

Determined by comparison of reported optical rotation.

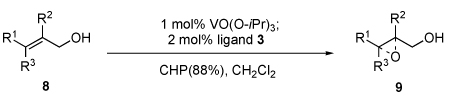

2.3. Asymmetric epoxidation of small Allylic alcohol

Our vanadium-bis-hydroxamic acid ligand system was next applied to asymmetric synthesis of small epoxy alcohols, a long-standing problem for asymmetric oxidation.2 Since our vanadium-3 complex was very difficult to be decomposed by water and very soluble in organic solvent, the product was extracted with water to give the enantiopure epoxy alcohols after the reaction (Table 3).15

Table 3.

Asymmetric epoxidation of small allylic alcohols

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry[a] | epoxy alcohol | ligand | temp, time | yield[b] (%) |

ee [c], (%) |

config.[d] | |

| 1[e] | 9n | 3b | 0°C, 12h ~rt, 12h |

78 | 97, | (R) | |

| 2[e, f] | 3b | 0°C, 24h ~rt, 24h |

70 | 96, | (R) | ||

| 3 | 9n | 3a | 0°C, 12h ~rt, 12h |

50 | 93, | (2R, 3R) | |

| 4 | 9o | 3c | 0°C, 12h ~rt, 12h |

71 | 92, | (2R, 3S) | |

| 5 | 9p | 3a | 0°C, 12h ~rt, 12h |

68 | 95, | (2R, 3R) | |

| 6[e] | 9q | 3b | 0°C, 12h ~rt, 12h |

73 | 94, | (S) | |

All reactions were carried out in dichloromethane in the presence of 1.5 equiv of cumene hydroperoxide (CHP) (88%) unless otherwise indicated.

See experimental procedure.

Ee values were determined by chiral GC and the detailed information was provided in our published paper.7

Determined by comparison of reported optical rotation.

Toluene was used as solvent.

0.5 mol% VO(O-i-Pr)3 and 0.6 mol% ligand was used.

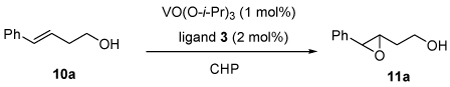

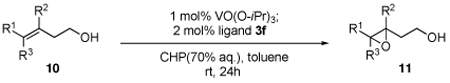

2.4. Asymmetric epoxidation of Homoallylic alcohol

We broadened our study to the asymmetric epoxidation of homoallylic alcohols, which was more challenging than allylic alcohols.2,6,13 Compared with the catalyst system of allylic alcohols, several different modified conditions were: 1) CHP was better than TBHP to facilitate and complete the transformation; and 2) toluene was used as solvent to inhibit cyclization of the produced epoxide to the corresponding tetrahydrofuran by-product. Based on modified conditions, all the three ligands that applied to epoxidation of allylic alcohols (3a, 3b and 3c) were tested for homoallylic alcohol 10a. Ligand 3c was demonstrated to be highly effective. With this promising result in hand, we then modified ligands based on 3c. Ligand 3f was synthesized and its vanadium complex increased the enantioselectivity dramatically. Finally, 3h, which was introduced with a more hindered substituted phenyl group, was found to be excellent for the reaction; 96% ee was obtained on 10a while the rate of the reaction was also facilitated. (Table 4.)

Table 4.

Ligand screening for asymmetric epoxidation of homoallylic alcohols

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry[a] | ligand | solvent | temp, time | (%)yield[c] | (%)ee[b] |

| 1 | 3a | toluene | rt, 12h | 23 | 10 |

| 2 | 3b | toluene | rt, 12h | 48 | 53 |

| 3 | 3c | toluene | rt, 12h | 52 | 71 |

| 4 | 3f | toluene | rt, 12h | 56 | 90 |

| 5 | 3g | toluene | rt, 12h | 60 | 92 |

| 6 | 3h | toluene | rt, 12h | 61 | 96 |

All reactions were carried out in toluene in the presence of 1.5 equiv. of cumene hydroperoxide (CHP) (88%) unless otherwise indicated.

Isolated yield after chromatographic purification.

Ee values were determined by either chiral HPLC (AD-H) or GC and the detailed information was provided in our published paper.8

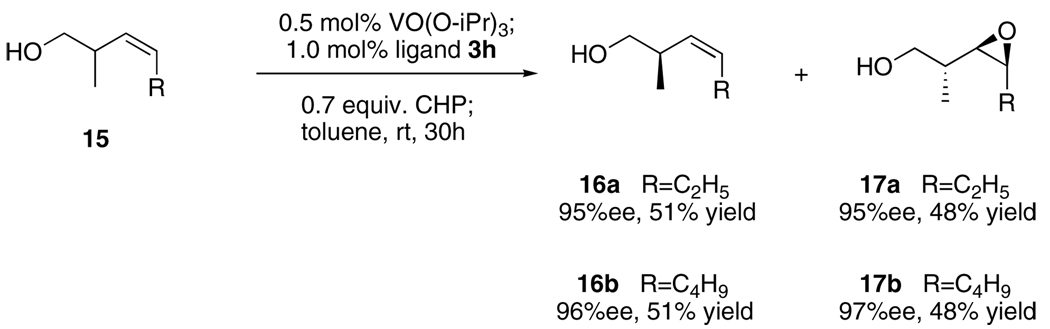

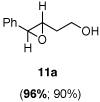

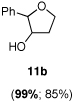

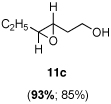

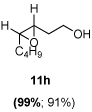

The scope of the reaction was investigated with 3h under the modified conditions. Gratifyingly, both trans- and cis-substituted epoxides were achieved with virtually complete enantioselectivities and satisfactory yields (Table 5).8,15

Table 5.

Asymmetric epoxidation of homoallylic alcohols

| ||

|---|---|---|

| (ee; yield) | ||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

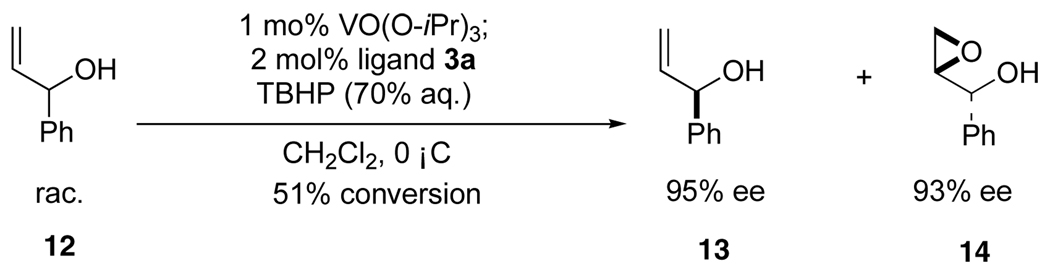

2.5. Kinetic resolution of allylic and homoallylic alcohols

With the successful results of the asymmetric epoxidation of allylic and homoallylic alcohols, this catalyst system was applied to the kinetic resolution of these alcohols with outstanding selectivities (Scheme 4, 5). Both the starting alcohols and epoxy alcohols were obtained with satisfactory enantiopurity. For the case of homoallylic alcohols, it should also be noted that this kinetic resolution gave us an opportunity to generate asymmetric carbon in a completely new scheme.7,8,15

Scheme 4.

Kinetic resolution of allylic alcohol.

2.6. Proposed transition state

To explain the enantioselectivity, we propose the following possible intermediate during epoxidation (Scheme 6). From the structural features of chiral cyclohexyl diamine, the second and fourth quadrants are more crowded than the first and third quadrants. The transition state assembly of the ligand, allylic alcohol (or homoallylic alcohol) and TBHP (or CHP) is governed by the following factors: a) steric repulsion of the carboxylate side chain and cyclohexane ring to direct the carbonyl inside the ring; b) trans approach of the allylic alcohol (or homoallylic alcohol) and TBHP (or CHP) to minimize the steric hindrance c) spiro overlap of olefin and oxygen. For the case of allylic alcohol, the steric bulk at the alpha position of the carboxylate plays an important role, which is greater in case 3a, and suitable for trans-substituted allylic alcohols. On the other hand, the additional flexibility of ligand 3c allows the cis- substituted allylic alcohols enough space to fit in the chiral pocket resulting in high selectivity.

Scheme 6.

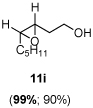

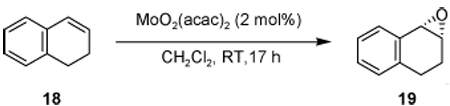

2.7. Asymmetric epoxidation of olefin

In a previous survey of metal BHA complexes to perform oxidations of allylic alcohols, an interesting reaction was observed. During the epoxidation of geraniol with molybdenum-3c in the presence of TBHP, it was noticed that the reaction provided a 1:1 mixture of 2,3-epoxygeraniol and 6,7-epoxygeraniol.7,16 These results suggested that a MoVI complex of BHA in the presence of an organic hydroperoxide is a stronger oxidizing agent than VV complex and that the former does not require substrate metal coordination during the catalytic cycle.17 This prompted us to explore enantioselective oxidation of olefins with Mo-BHA catalyst.

Industrial use of molybdenum-peroxo complex for epoxidation of alkenes has been extensively explored over the last 40 years beginning with homogeneous MoVI catalysts in the Halcon and Arco processes.18 Consequently, considerable effort has been directed towards the development of enantioselective epoxidation with chiral molybdenum catalysts.19,20 However, due to weak coordination of ligands with the molybdenum, very little success has been achieved. The Mo-BHA complex successfully performed the catalyzed asymmetric oxidation of mono, di-, and tri-substituted olefins under mild conditions in air at room temperature to give epoxides in high yields and up to excellent selectivity.9

In early experiments of the epoxidation of olefin 18, we found that ligand 3c provided a higher selectivity over ligand 3a in the presence of aqueous TBHP (Table 6, entries 1-2). Changing the oxidant to CHP or tritylhydroperoxide (THP) did improve the selectivity, but reactivity was slower when bulkier THP was utilized. Furthermore, oxidation of 18a with bulkier ligands (3c–f) or a bulkier oxidant provided good to excellent selectivity (entries 4-6). However, we found that there is a ligand-oxidant relationship, whereas a ligand that is too bulky 3g will decrease selectivity (entry 7) Additionally, we investigate the use of different BHA backbones such as 7a and 7b, but the selectivities realized were either slightly less or decreased, respectively (entries 8,9).

Table 6.

Effect of achiral oxidant and ligand[a]

| |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | oxidant | ligand | % yield[b] | % ee[c] | |

| 1 | TBHP(aq) | 3a | 20 | 28 | |

| 2 | TBHP(aq) | 3c | 15 | 42 | |

| 3 | CHP | 3c | 72 | 66 | |

| 4 | CHP | 3c | 27 | 96 | |

| 5 | CHP | 3e | 92 | 80 | |

| 6 | CHP | 3f | 82 | 87 | |

| 7 | TBHP | 3g | 91 | 58 | |

| 8 | THP | 7a | 17 | 91 | |

| 9 | THP | 7b | 13 | 42 | |

All reactions were carried out in CH2Cl2 in the presence of 1.5 equiv. of oxidant and 2 mol % of molybdenum catalyst at RT in air unless otherwise indicated.

Isolated yield after chromatographic purification.

Determined by chiral HPLC or GC

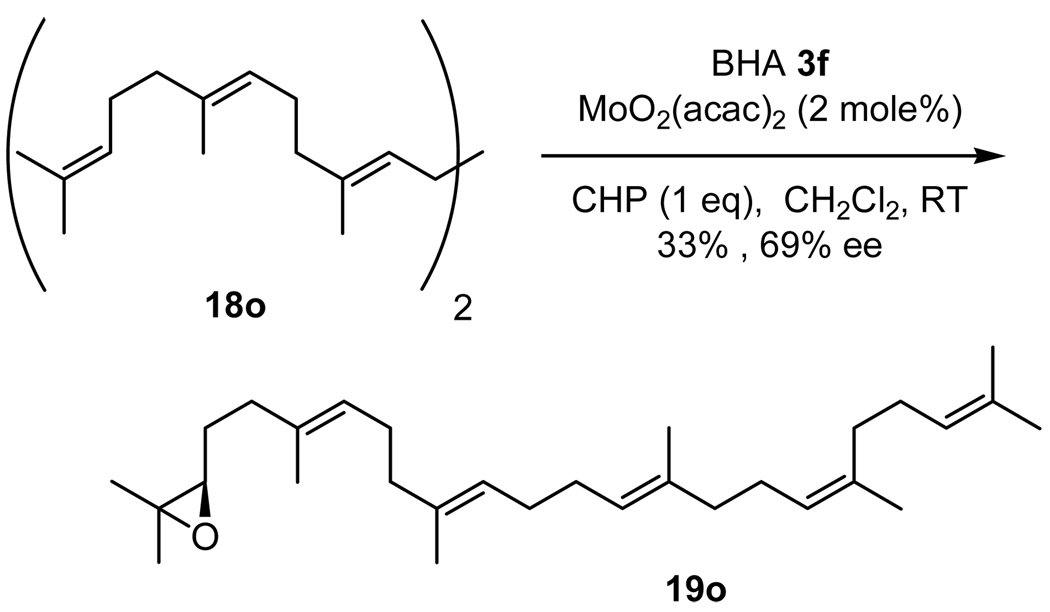

Under optimized conditions, we examined the scope of the reaction which proceeded in air at room temperature; Table 7 shows our preliminary results in olefin oxidation. More notably, the size of ligands and the number of alkene substituents play a crucial role in determining the rate of the oxidation. As illustrated in Table 7, all cis-substituted olefins gave excellent selectivity during oxidation (entries 1–4). It is noteworthy that the epoxidation of 18c realizes only cis product; no trans product is detected (entry 3). Tri-substituted and terminal alkenes also provided good selectivity (entries 6–8,10,11). Another important aspect of this Mo-BHA catalyst is that it selectively oxidizes the most electron rich alkene in the presence of multiple double bonds (entries 12–13). Encouraged by the selectivity observed during myrcene (18m) oxidation, squalene (18o), an important biogenetic precursor of steroids and polycyclic terpenoids, was subjected to similar reaction conditions (Scheme 7).21 To our delight, Mo-3f complex in the presence of 1 equiv. of CHP selectively provided 2,3-epoxysqualene with good enantioselectivity (69% ee). It is noteworthy that the synthesis 18o often requires multiple steps.

Table 7.

Oxidation of olefins with different substitution patterns [a]

| |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Entry | epoxide | ligand | oxidant | time (h) | yield [b] (%) |

ee (%),[c] config[d] |

|

| 1 | 19a | 3d | THP | 18 h | 81 | 96(S,R) | |

| 2 | 19b | 3c | THP | 19h | 87 | 91(S,R) | |

| 3 | 19c | 3d | THP | 20h | 19 | 90(S,R) | |

| 4 | 19d | 3e | TBHP | 20h | 13 | 93(S,R) | |

| 5 | 19e | 3f | CHP | 22h | 77 | 64(R,S) | |

| 6 |  |

19f | 3c | THP | 36h | 7 | 70(R) |

| 7 |  |

19g | 3f | TBHP | 36h | 29 | 72(R) |

| 8 |  |

19h | 3e | CHP | 23h | 70 | 60(R) |

| 9 | 19i | 3f | TBHP | 40h | 77 | 43(R) | |

| 10 |  |

19j | 3f | CHP | 36h | 89 | 50(R,S) |

| 11 | 19k | 3f | TBHP | 36h | 41 | 81(S,S) | |

| 12 | 19l | 3f | TBHP | 46h | 47 | 33 de trans/ cis |

|

| 13 | 19m | 3f | CHP | 44h | 91 | 75(R) | |

| 14 |  |

19n | 3f | TBHP | 17h | 13 | 43 |

All reactions were carried out in CH2Cl2 the presence of 1.5 equiv of oxidant and 2 mol % of molybdenum catalyst at RT unless otherwise indicated.

Isolated yield after chromatographic purification.

Determined by chiral HPLC or GC.

Configurations determined by comparison of specific rotation to literature.

Scheme 7.

Regio- and enantioselective oxidation of squalene.

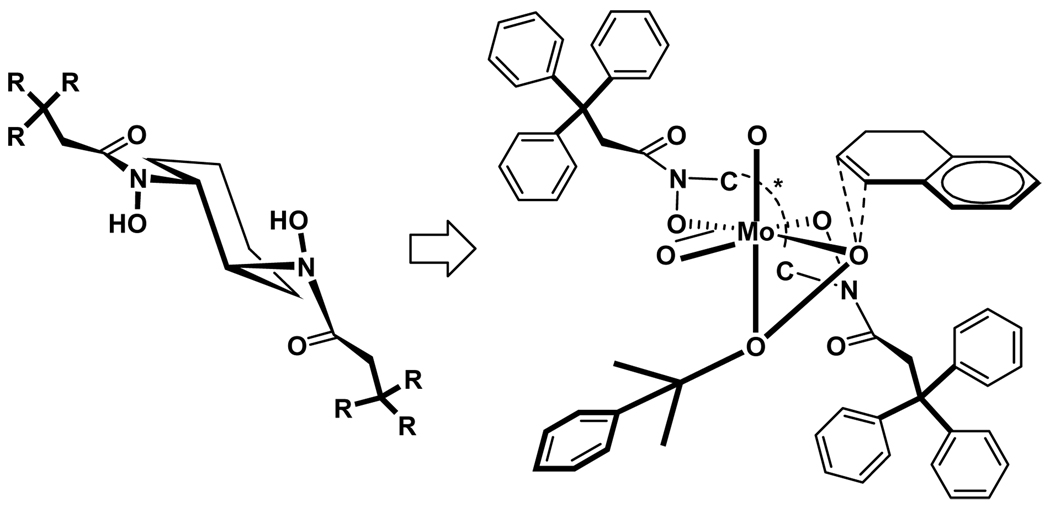

2.8. Proposed transition state for Mo-BHA

We believe that the mechanism follows the concerted metal alkyl peroxide mechanism supported by Sharpless.22 The BHA-Mo complex combines with the achiral oxidant to oxidize the olefin in a concerted fashion by transfer of oxygen from the metal peroxide to the olefin. To explain the enantioselectivity, we propose the following possible intermediate during epoxidation, noting the importance of the bulky achiral oxidant (Scheme 8). From the structural features of chiral cyclohexyl diamine, the second and fourth quadrants are more crowded than the first and third quadrants, similar to the V-BHA proposed earlier.

Scheme 8.

Proposed transition state for Mo-BHA.

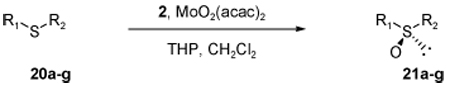

2.9. Asymmetric oxidation of sulfides and disulfides

To demonstrate further the versatility of the BHA, we proceeded to investigate its utility in the oxidation of sulfides. Metal catalyzed asymmetric oxidation of sulfides, a powerful strategy for the rapid preparation of enantiopure sulfoxides, has garnered extensive attention from the synthetic community.23–27 However, to date, application of molybdenum as a catalyst for the asymmetric oxidation of sulfide remains under-explored.29 Here, we report the first successful catalytic asymmetric oxidation of sulfides and disulfides utilizing a catalytic amount of a chiral molybdenum complex in the presence of an achiral oxidant under mild conditions.10

To evaluate the general applicability of BHA as a ligand for asymmetric oxidation of various sulfides, phenyl methyl sulfide 20a was explored with our early results in Table 8.10 At this stage, an array of ligands, reaction conditions and oxidants were surveyed. We found that 2 mole% molybdenum catalyst in the presence of THP is optimal for the high enantioselectivity (entry 3). CHP also provided good enantioselectivity (entry 2) under similar reaction conditions. Highest enantioselectivity was obtained when bulkier BHA 3e was utilized. It is important to note here that, isopropyl phenyl sulfide (20e), which usually provides relatively low enantionselectivity,23a,24e also provided good selectivity (entry 12).

Table 8.

Asymmetric oxidation of sulfides

| ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| entry | sulfide | ligand | time (h) | yield b (%) |

ee (%), c config d |

|

| 1 | 3ce | 17 h | 77 | 54 (S) | ||

| 2 | 20a | 3c f | 26 h | 89 | 65 (S) | |

| 3 | 3c | 20 h | 83 | 68 (S) | ||

| 4 | 3d | 18 h | 60 | 79 (S) | ||

| 5 | 3e | 16 h | 81 | 79 (S) | ||

| 6 | 20b | 3d | 17 h | 99 | 65 (S) | |

| 7 | 3e | 20 h | 75 | 81 (S) | ||

| 8 | 20c | 3d | 17 h | 76 | 66 (S) | |

| 9 | 3e | 19 h | 76 | 75 (S) | ||

| 10 | 20d | 3d | 18 h | 99 | 68 (S) | |

| 11 | 3e | 18 h | 81 | 82 (S) | ||

| 12 | 20e | 3e | 24 h | 66 | 62 (R) | |

| 13 |  |

20f | 3e | 17 h | 82 | 86 (S) |

| 14 | 3ef | 21 h | 71 | 82 (S) | ||

| 15 | 20g | 3e | 19 h | 83 | 72 (S) | |

All reactions were carried out in CH2Cl2 the presence of 1.0 equiv of THP and 2 mol % of molybdenum catalyst at 0 °C unless otherwise indicated.

Isolated yield after chromatographic purification.

ee values were determined by chiral HPLC.

configurations determined by comparison of optical rotation to literature.

1.0 equiv TBHP.

1.0 equiv CHP.

High enantioselectivity during sulfide oxidation is often due to kinetic resolution of the newly formed sulfoxides by generating a significant amount of sulfones.24–28 We found that the oxidation of phenyl methyl sulfoxide (20a) was slow, but molybdenum-3d complex selectively oxidized one of the enantiomers. We were pleased to find that the R isomer of 21a, which the minor isomer produced during oxidation of 20a, was oxidized in a faster rate.

The results of this study are listed in Table 9. Both oxidants CHP and THP provided excellent selectivity during the process (ee 87–99%).

Table 9.

Asymmetric Oxidation with Kinetic Resolution

| entry | Sulfide | Oxidant | Sulfoxide:Sulfone | yield b (%) |

ee (%), c config |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 20a | THP g | 81:19 | 68 | 92 (S) |

| THP d | 81:19 | 66 | 92 (S) | ||

| CHP e | 49:51 | 43 | 96 (S) | ||

| 2 | 20b | THP g | 82:18 | 74 | 87 (S) |

| THP | 74:26 | 55 | 94 (S) | ||

| CHP e | 46:54 | 37 | 95 (S) | ||

| 3 | 20d | THP g | 80:20 | 69 | 91 (S) |

| THP | 72:68 | 51 | 96 (S) | ||

| CHP f | 32:68 | 31 | 97 (S) | ||

| 4 | 20g | THP | 76:24 | 50 | 93 (S) |

| CHP e | 50:50 | 47 | 99 (S) |

All reactions were carried out in CH2Cl2 the presence of 1.5 equiv of THP and 2 mol % of molybdenum-3d catalyst at −40 °C, 19 h then 0 °C, 24 h unless otherwise indicated

Isolated yield after chromatographic purification.

ee values were determined by chiral HPLC

−40 °C, 44 h then 0 °C, 47 h

1.55 eq. CHP.

1.75 eq. CHP.

2 mol % of molybdenum-3e

3. Conclusion

In conclusion, we have designed a series of new C2-symmetric bis-hydroxamic acid ligands and developed a new catalyst system for the asymmetric oxidation of allylic alcohols, homoallylic alcohols, unfunctionalized olefins, and sulfides. In addition, kinetic resolution of allylic alcohols, homoallyic alcohols, and sulfides enhances its versatility as an asymmetric catalyst. Mechanistic understanding and study of further applications of bis-hydroxamic acid ligands in asymmetric reactions are on going.

4. Experimental

4.1. General Methods

Infrared (IR) spectra were recorded on a Nicolet 20 SXB FTIR. 1H NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance 400 (400 MHz) or Bruker Avance 500 (500 MHz) spectrometer. Chemical shift values (δ) are expressed in ppm downfield relative to internal standard (tetramethylsilane at 0 ppm). Multiplicities are indicated as s (singlet), d (doublet), t (triplet), q (quartet), m (multiplet) and br (broad). 13C NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker Avance 400 (100 MHz), a Bruker Avance 500 (125 MHz) spectrometer and are expressed in ppm using solvent as the internal standard (CDCl3 at 77.23 ppm). High-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) was performed on a Varian ProStar Series equipped with a variable wavelength detector using chiral stationary columns (Chiracel, AD, AS, OB, OB-H, OD, or OD-H, 0.46 cm × 25 cm) from Daicel. Optical rotations were measured on a JASCO DIP-1000 digital polarimeter. Analytical gas-liquid chromatography (GLC) was performed on a Shimadzu GC-17A instrument equipped with flame ionization detector and a capillary column using chiral columns G-TA (0.25mm × 25m) or BDP (0.25mm × 25m) using nitrogen as carrier gas. All reactions were carried out in oven-dried glassware with magnetic stirring unless otherwise noted. Analytical thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was performed on Merck pre-coated TLC plates (silica gel 60 GF254, 0.25mm). Flash chromatography was performed on silica gel E. Merck 9385 or silica gel 60 extra pure (for all the bis-hydroxamic acids). Dichloromethane (CH2Cl2) and toluene (PhCH3) were purchased from Acros as anhydrous solvents. N,N-diisopropylethylamine and triethylamine were stored over KOH pellets. Substrates were purchased from commercial vendors or have been previously prepared by reported procedures and characterized. Olefins and products in Table 7 have been previously isolated and characterized. Sulfides and products in Table 8 have been previously isolated and characterized. References can be found elsewhere and within this paper. Anhydrous trityl hydroperoxide (THP) was prepared according to the literature procedure. All other reagents and starting materials, unless otherwise noted, were purchased from commercial vendors and used without further purification. High-resolution electro spray ionization (HRMS-ESI) mass spectra were obtained on a Micromass Q-T of -2, Quadruple Time of Flight mass spectrometer at the University of Illinois Research Resources Center in positive mode.

4.2. Preparation of ligands

4.2.1. Preparation of (R,R)-N,N'-Bis-(4-methoxybenzylidene)-cyclohexane-1,2-diimine

A mixture of diammonium salt (4) (26.4 g, 100 mmol), K2CO3 (27.6 g, 200 mmol), and de-ionized water (130 mL) was stirred until dissolution was achieved, and then ethanol (420 mL) was added. The resulting cloudy mixture was heated to reflux, and a solution of p-anisaldehyde (27.5 g, 200 mmol) in ethanol (40 mL) was added in a steady stream over 30 min. The yellow slurry was stirred at reflux for 5 h before heating was discontinued. The reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature, and the water phase was separated and discarded. The organic phase was concentrated and dissolved in dichloromethane. It was then removed any trace of water, dried over Na2SO4 and filtered. The filtrate was removed solvent to provide crude diimine as light yellow solid, which was purified by recrystalization from dichloromethane and hexanes as white solid (31.5 g, 90% yield). FTIR (film)vmax 2929, 2855, 1643, 1606, 1579, 1512, 1463, 1303, 1250, 1165, 1032, 831 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.12 (s, 2 H), 7.52 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 4 H), 6.82 (d, J = 8.8 Hz, 4 H), 3.78 (s, 6 H), 3.37-3.32 (m, 2 H), 1.87-1.77 (m, 6 H), 1.49-1.46 (m, 2 H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 161.5 (C), 160.5 (CH), 129.7 (CH), 114.0 (CH), 74.0 (CH3), 55.5 (CH), 33.3 (CH2), 24.8 (CH2); HRMS-ESI calcd for C22H27O6N2 [M+H]+ 351.2073, found 351.2076.

4.2.2. Preparation of Dioxaziridine 5

To a stirred solution of diimine (10.5 g, 30.0 mmol) in MeCN (180 mL) and THF (360 mL), at room temperature, was added an aqueous solution (300 mL) of KHCO3 (50.5 g, 504 mmol) followed by an aqueous solution (300 mL) of Oxone (44 g, 72 mmol). After stirring for 3 h, the reaction mixture was diluted with CH2Cl2 (600 mL). The biphasic mixture was separated and the aqueous portion was extracted with CH2Cl2 (2 × 100 mL) and the combined organic extracts was dried over Na2SO4 and filtered. The filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure to provide crude dioxaziridine 5 (10.3 g, 90% yield) as light yellow solid, which was used in the following step without further purification. Pure product, which was applied to determine the structure, was obtained by recrystalization from dichloromethane and hexane as white solid: FTIR (film) vmax 2935, 1615, 1517, 1309, 1456, 1437, 1310, 1252, 1171, 1031, 821 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 6.81-6.78 (m, 4 H), 6.58-6.54 (m, 4 H), 4.37 (s, 2 H), 3.78 (s, 6 H), 2.39-2.37(m, 2 H), 2.21-2.18 (m, 2 H), 1.83-1.80 (m, 2 H), 1.58-1.51 (m, 2 H), 1.31-1.27 (m, 2 H). 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 160.7 (C), 129.0 (CH), 126.5 (C), 113.8 (CH), 81.6 (CH), 72.4 (CH3/CH), 55.4 (CH3/CH), 30.3 (CH2), 24.1 (CH2); HRMS-ESI calcd for C22H26O4N2Na [M+Na]+ 405.1788, found 405.1790.

4.2.3. Preparation of Dihydroxylamine dihydrochloride

To a mixture of the unpurified product 5 (10.3 g) obtained from the previous oxidation reaction and benzyloxyhydroxyl amine hydrochloride (8.80 g, 55.1 mmol) was treated with anhydrous methanol (250 mL), and then 1 M HCl in MeOH (94 mL, 94 mmol) was added immediately. The resulting mixture was stirred for 20 minutes. The reaction mixture was then concentrated under reduced pressure to dryness. Et2O (200 mL) and de-ionized water (100 mL) was added. The bi-layer was separated and the organic part was extracted with de-ionized water (20 mL). Combined aqueous portion was washed with Et2O (2 × 100 mL). The aqueous portion was concentrated to 60–75 mL and the resulting white solid (BnONH2.HCl) was filtered off, then filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure to provide bis-hydroxylamine dihydrochloride (6.10 g, 90% yield) as an oily solid, which contained 5–10% of BnONH2.HCl. This material was utilized in the next step without any purification: 1H NMR (400 MHz, D2O) δ 3.66-3.62 (m, 2 H), 2.02-1.98 (m, 2 H), 1.69-1.66 (m, 2 H), 1.41-1.37 (m, 4 H), 1.20-1.15 (m, 2 H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, D2O) δ 58.6 (CH), 25.1 (CH2), 22.1 (CH2).

4.2.4. Preparation of O-protected Dihydroxylamine 6

To a stirred suspension of unpurified bis-hydroxylamine dihydrochloride (6.10 g) obtained from the previous reaction in CH2Cl2 (100 mL) under nitrogen at room temperature was added Et3N (11.1 mL, 76.8 mmol). After 1 h, to the resulting cloudy white suspension, DMAP (180 mg, 1.47 mmol), imidazole (2.00 g, 29.4 mmol) followed by dichlorodiisopropylsilane (5.00 mL, 27.7 mmol) were added and stirring was continued 2 h, and then poured into an aqueous solution of NaHCO3 (5.16 g, 61.4 mmol) and extracted with EtOAc (2 × 100 mL). The combined organic extracts was dried over Na2SO4, filtered and concentrated under reduced pressure. The residue was dissolved in a small amount of dichloromethane and filtered through a small plug of silica gel by washing with the mixture of EtOAc/hexanes (5:95) to provide 6 (3.85 g, 61% yield), which was used in the following step without further purification: 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 5.17 (br, 2 H), 2.83-2.77 (m, 2 H), 1.76-1.74 (m, 2 H), 1.54-1.50 (m, 2 H), 1.30-1.26 (m, 2H), 1.12-1.03 (m, 16 H).

4.2.5. General procedure for preparation of Bis-hydroxamic acids

To a stirred solution of 6 (570 mg, ~2.0 mmol) obtained from the previous reaction and DIEA (1.04 mL, 6.00 mmol) in CH2Cl2 (20 mL) was added acid chloride (6.00 mmol, dissolved in 10 mL CH2Cl2) under nitrogen. After 72 h, the reaction mixture was treated with 3N HCl (or 1M HCl/MeOH). After stirring for 30 min the reaction mixture was extracted with CH2Cl2, washed with brine, dried over Na2SO4 and filtered. The filtrate was concentrated under reduced pressure and the residue was purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel to provide the bis-hydroxamic acid.

4.2.5.1. Ligand 3a

Yield, 55%; white solid: Rf 0.5 (EtOAc/hexanes, 3:7); FTIR (film) vmax 3195, 3062, 3029, 2961, 2940, 2862, 1750, 1687, 1658, 1620, 1600, 1495, 1451, 1401, 1309, 1251, 1166, 1079, 1032, 909, 733, 699 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 9.04 (s, 2 H), 7.32-7.04 (m, 20 H), 5.50 (s, 2 H), 4.56-4.55 (m 2 H), 1.78 (m, 6 H), 1.24 (m, 2 H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 175.2 (C=O), 139.4 (C), 139.2 (C), 129.5 (CH), 128.9 (CH), 128.8 (CH), 128.7 (CH), 127.3 (CH), 127.1 (CH), 56.7 (CH), 53.4 (CH), 27.9 (CH2), 24.6 (CH2). HRMS-ESI calcd for C34H34O4N2Na [M+Na]+ 557.2416, found 557.2438; [α]D28.4 +93.47 (c 1.0, CHCl3). Melting Point 229–231°C.

4.2.5.2. Ligand 3b

Yield, 20%: Rf 0.5 (EtOAc/hexane, 1:4); FTIR (film) vmax 3172, 3007, 2919, 2861, 1621, 1602, 1452, 1404, 1309, 1264, 1233, 1166, 1132, 1037, 958, 897, 851, 823, 790, 770, 736, 710, 688, 660 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.42 (s, 2 H), 6.87-6.72 (m, 12 H), 5.35 (s, 2 H), 4.52-4.50 (m 2 H), 2.27 (s, 12 H), 2.14 (s, 12 H), 1.89-1.77 (m, 6 H), 1.26 (m, 2 H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 175.0 (C=O), 139.2 (C), 139.0 (C), 137.9 (C), 137.5 (C), 128.6 (CH), 128.5 (CH), 126.8 (CH), 126.4 (CH), 56.5 (CH), 53.0 (CH), 27.7 (CH2), 24.5, (CH2), 21.4 (CH3), 21.3 (CH3); HRMS-ESI calcd for C42H50O4N2Na [M+Na]+ 669.3668, found 669.3668.

4.2.5.3. Ligand 3c

Yield, 72%; white solid: Rf 0.63 (EtOAc/hexanes, 1:3); FTIR (film) vmax 3150, 2938, 2859, 1616, 1493, 1446, 1419, 1170, 769, 700 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.26 (s, 2 H), 7.28-7.17(m, 30 H), 4.19 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 2 H), 3.94-3.92 (m, 2 H), 3.55 (d, J = 16.1 Hz, 2 H), 1.68-1.65 (m, 2 H), 1.50-1.38 (m, 4 H), 1.12-1.07 (m, 2 H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 173.6 (C=O), 147.2 (C), 129.6 (CH), 127.8 (CH), 126.3 (CH), 56.2 (C), 55.2 (CH), 42.5 (CH2), 27.5 (CH2), 24.6 (CH2); HRMS-ESI calcd for C48H46O4N2Na [M+Na]+ 737.3355, found 737.3379; [α]D28.4 +22.12 (c 1.0, CHCl3). Melting Point 235–237°C.

4.2.5.4. Ligand 3d

Yield, 72%; white solid; (EtOAc/hexanes, 1:3); FTIR (film) vmax 3166, 2921, 2861, 2360, 2339, 1616, 58 1456, 1418, 1239, 1172, 1021, 910, 811, 732, 570 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.75 (s, 2 H), 7.11 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 12 H), 7.03 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 12 H), 4.14 (br d, J = 14.5 Hz, 2 H), 3.98 (br m, 2 H), 3.56 (br d, J = 14.5 Hz, 2 H), 2.3 (s, 18 H), 1.97 (m, 2 H), 1.69 (m, 2 H), 1.55-1.47 (m, 4 H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 174.0, 144.5, 135.6, 129.2, 128.5, 55.1, 54.8, 42.8, 27.5, 24.5, 21.0. Melting Point 232–233°C; High Resolution Mass Spec: M+H 799.447 observed, 799.44693 expected.

4.2.5.5. Ligand 3e

Yield, 72%; white solid; Rf 0.62 (EtOAc/hexanes, 1:3); FTIR (film) vmax 3126, 2958, 2870, 1616, 1507, 1457, 1418, 1240, 1173, 1057, 1019, 910, 828, 734, 584 cm−1; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.40 (s, 2 H), 7.14 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 12 H), 6.97 (d, J = 7.5 Hz, 12 H), 4.07 (br d, J = 14.5 Hz, 2 H), 3.80-3.78 (br m, 2 H), 3.59 (br d, J = 14.5 Hz, 2 H), 2.85-2.79 (m, 6 H), 1.54-1.50 (m, 2 H), 1.29-1.15 (m, 40 H), 0.95-0.91 (m, 2 H); 13C NMR (125 MHz, CDCl3) δ 173.6, 146.3, 144.9, 129.6, 125.7, 55.8, 55.0 42.2, 33.7, 27.4, 24.5, 24.3, 24.1. Melting Point 193–195°C; High Resolution Mass Spec: M+H 967.6357 observed, 967.63474 expected.

4.2.5.6. Ligand 3f

Yield, 45%; white solid: Rf 0.50 (EtOAc/hexanes, 1:6); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 8.08 (br, 2 H), 7.23-7.21 (m, 12 H), 7.16-7.14 (m, 12 H), 4.23-4.20 (m, 2 H), 4.13-4.11 (m, 2 H), 3.67-3.64 (m, 2 H), 1.60-1.00 (m, 8 H), 1.27 (s, 54 H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 173.5 (C=O), 148.3 (C), 144.2 (C), 129.0 (CH), 124.4 (CH), 55.0 (C), 54.9 (CH), 42.3 (CH2), 34.3 (C), 31.4 (CH3), 27.4 (CH2), 24.3 (CH2). HRMS-ESI calcd for C72H95O4N2 [M+H]+ 1051.7286, found 1051.7267. Melting Point 225–227°C.

4.2.5.7. Ligand 3g

Yield, 40%; white solid: Rf 0.35 (EtOAc/hexanes, 1:6); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.56 (s, 2 H), 7.30-7.28 (m, 12 H), 7.00-6.98 (m, 12 H), 6.89 (s, 12H), 4.52 (d, J = 16.4 Hz, 2 H), 4.11-4.10 (m, 2 H), 3.70 (d, J = 16.4 Hz, 2 H), 2.28 (s, 18H), 1.97(s, 36H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 174.6 (C=O), 145.6 (C), 138.8 (C), 138.6 (C), 136.4 (C), 136.0 (C), 129.6 (CH), 128.8 (CH), 128.3 (CH), 55.8 (C), 55.0 (CH), 43.7 (CH2), 27.6 (CH2), 24.4 (CH2), 21.0 (CH3), 20.8 (CH3). Melting Point 212–213°C; High Resolution Mass Spec: M+H 1423.82057 observed, 1423.82254 expected.

4.2.5.8. Ligand 3h

Yield, 40%; white solid: Rf 0.45 (EtOAc/hexanes, 1:6); 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) δ 7.39 (s, 2 H), 7.29-7.27 (m, 12 H), 7.04-7.01 (m, 12 H), 6.93 (s, 12H), 4.51 (d, J = 16.4 Hz, 2 H), 4.11-4.10 (m, 2 H), 3.73 (d, J = 16.4 Hz, 2 H), 2.65 (q, J = 7.6 Hz, 12 H), 2.32 (q, J = 7.5 Hz, 24 H), 1.78-1.74 (m, 6 H), 1.28 (q, J = 7.6 Hz, 18 H), 1.22-1.20 (m, 2 H), 0.99 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 36 H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 174.7 (C=O), 145.6 (C), 143.1 (C), 142.1 (C), 138.2 (C), 137.8 (C), 129.2 (CH), 128.9 (CH), 125.1 (CH), 55.7 (C), 54.8 (CH), 43.7 (CH2), 28.6 (CH2), 27.6 (CH2), 26.9 (CH2), 24.4 (CH2), 15.5 (CH3), 15.4 (CH3); HRMS-ESI calcd for C120H143O4N2 [M+H]+ 1676.1042, found 1676.1040.

4.2.5.9. Ligand 7a

Yield, 34%, 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ7.22 (30H, m), δ 5.28 (2H, dd), 4.06 (2H, d), 3.85 (2H, m), 2.18 (2H, m), 1.95 (2H, m), 1.72 (2H, m). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 169.80 (C=O), 136.4 (C), 129.24 (CH), 127.68 (CH), 123.4 (CH), 70.57 (CH), 54.1 (CH2), 43.66 (CH), 37.62 (CH2), 36.67 (C); FTIR (film) vmax 3431, 2916, 2848, 2338, 2112, 1642, 1492, 1472, 1446, 1416, 1265, 1186, 1034, 910, 700, 576 cm−1; Melting Point 139–142°C; High Resolution Mass Spec: M+H 745.3274 observed, 745.32721 expected.

4.2.5.10. Ligand 7b

Yield, 90%, 1H NMR (500 MHz, CDCl3) δ.18 (24H, m), 7.12 (6H, m), 6.36 (2H, brs), 4.88 (2H, m), 4.31 (2H, d), 3.92 (4H, s), 3.79 (2H, t), 3.72 (2H, m). 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) δ 168.4 (C=O), 143.0 (C), 129.6 (CH), 127.8 (CH), 126.3 (CH), 56.2 (C), 43.1 (CH), 27.5 (CH2), 24.6 (CH2); FTIR (film) vmax 3436, 3057, 2939, 2860, 2361, 2336, 1617, 1493, 1421, 1241, 1170, 1029, 737, 561 cm−1;

4.3. General procedure for asymmetric epoxidation of allylic alcohols in the presence of VO(OPri)3 and ligand 3

To a solution of 3 (0.0210 mmol) in dichloromethane or toluene (1 mL) was added VO(OPri)3 (0.0025 mL, 0.0104 mmol), and the mixture was stirred for 1 h at room temperature. The resulting solution was cooled to 0 °C, and then 70% aqueous tert-butylhydroperoxide (TBHP) (0.22 mL, 1.59 mmol) and allylic alcohol 8 (1.05 mmol) were added and stirring was continued at the same temperature for several hours. The process of epoxidation was monitored by TLC. Saturated aqueous Na2SO3 was added, and the mixture was stirred for 1 h at 0 °C. The mixture was then allowed to warm to room temperature, extracted with Et2O, dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure. The remaining residue was purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel to provide epoxy alcohol 9.

4.4. General procedure for asymmetric epoxidation of small allylic alcohols in the presence of VO(OPri)3 and ligand 3

To a solution of 3 (0.0125 mmol) in dichloromethane or toluene (1 mL; for the case of 8q, only 0.25 mL of toluene was used as solvent) was added VO(OPri)3 (0.0025 mL, 0.0104 mmol), and the mixture was stirred for 1 h at room temperature. The resulting solution was cooled to 0 °C, and then 88% cumene hydroperoxide (CHP) (0.25 mL, 1.50 mmol) and small allylic alcohol 8 (0.086 mL, 1.00 mmol) were added and stirring was continued at the same temperature for 12 h. Reaction mixture was then allowed to warm to room temperature and stirring was continued at room temperature for another 12 h to make sure that the epoxidation was complete. It was then extracted with deionized water (3 × 0.5 mL). To the combined aqueous portion, saturated aqueous NaHCO3 (0.010 mL) was added to prevent the hydrolysis of the epoxy alcohol 9 and the mixture was extracted with toluene (3 × 1.0 mL) to remove residual cumene hydroperoxide and 2-phenyl-2-propanol. All the above extractions were performed by utilizing the vortex mixer to achieve efficient mixing and at 0 °C to prevent the hydrolysis of epoxy alcohol 9. To the aqueous portion, fresh distilled anhydrous THF (5 mL) was added and concentrated under reduced pressure with rotary evaporator at room temperature. To the concentrate (~2 mL), additional THF (5 mL) was added and solvent was removed under the same conditions. This process was repeated for 8 times and all the solvent was removed at the final time to provide the product as colourless liquid, which contained a mixture of epoxy alcohol 9 and THF (mole ratio was determined by 1H NMR). GC analysis: distribution of the product was above 97% epoxy alcohol 9.

4.5. General procedure for asymmetric epoxidation of homoallylic alcohols in the presence of VO(OPri)3 and ligand 3h

To a solution of 3h (35.2mg, 0.0210 mmol) in toluene (0.25 mL) was added VO(OPri)3 (0.0025 mL, 0.0104 mmol), and the mixture was stirred for 8 h at room temperature. 88% cumene hydroperoxide (CHP) (0.25 mL, 1.50 mmol) and homoallylic alcohol 10 (1.05 mmol) were then added and the stirring was continued at the same temperature for 24 hours. The process of epoxidation was monitored by TLC. The mixture was then allowed to be purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel to provide epoxy alcohol 11.

11a

Yield, 90%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) 7.35-7.26 (m, 5 H), 3.88-3.87 (m, 2 H), 3.74 (d, J = 2.1 Hz 1 H), 3.17-3.14 (m, 1 H), 2.14-2.09 (m, 1 H), 1.90-1.85 (m, 1 H), 1.80 (br, 1 H); 96% ee, HPLC (AD-H), Hexanes: iPropanol = 95:5, flow rate = 1 mL/min, 15.0 min (major), 17.6 min (minor).

11b

Yield, 85%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) 7.38-7.29 (m, 5 H), 4.14 (d, J = 4.2 Hz, 1 H), 3.80-3.76 (m, 2 H), 3.42-3.38 (m, 1 H), 1.61-1.51 (m, 3 H); 99% ee, HPLC (AD-H), Hexanes: iPropanol = 98:2, flow rate = 0.7 mL/min, 54.3 min (major), 57.7 min (minor).

11c

Yield, 85%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) 3.82-3.76 (m, 2 H), 2.90-2.85 (m, 1 H), 2.78-2.74 (m, 1 H), 2.00-1.90 (m, 1 H), 1.76-1.63 (m, 1 H), 1.58 (br, 1 H), 1.00 (t, J = 16.1 Hz, 3 H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) 59.8 (CH2), 56.5 (CH), 56.5 (CH), 34.3 (CH2), 25.9 (CH2), 9.8 (CH3); 93% ee, GC (γ-TA), injection 120°C, column 100°C, pressure 100Kpa, 41.8 min (major) (3R, 4R), 45.3 min (minor) (3S, 4S).

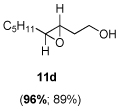

11d

Yield, 89%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) 3.80-3.79 (m, 2 H), 2.87-2.86 (m, 1 H), 2.81-2.80 (m, 1 H), 2.01-1.92 (m, 1 H), 1.91 (br, 1 H), 1.71-1.65 (m, 1 H), 1.55-1.52 (m, 2 H), 1.44-1.40 (m, 2 H), 1.34-1.30 (m, 4 H), 0.92 (t, J = 5.8 Hz, 3 H); 96% ee, GC (γ-TA), injection 120°C, column 100°C, pressure 100Kpa, 36.7 min (major), 38.0 min (minor).

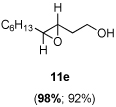

11e

Yield, 92%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) 3.80-3.79 (m, 2 H), 2.87-2.86 (m, 1 H), 2.81-2.80 (m, 1 H), 2.04-1.94 (m, 1 H), 1.90 (br, 1 H), 1.73-1.63 (m, 1 H), 1.55-1.52 (m, 2 H), 1.45-1.43 (m, 2 H), 1.36-1.30 (m, 6 H), 0.90 (t, J = 6.6 Hz, 3 H); 98% ee, GC (γ-TA), injection 120°C, column 100°C, pressure 100Kpa, 61.8 min (major), 63.0 min (minor).

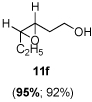

11f

Yield, 92%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) 3.84-3.81 (m, 2 H), 3.10-3.09 (m, 1 H), 2.91-2.89 (m, 1 H), 2.16 (br, 1 H), 1.85-1.83 (m, 1 H), 1.70-1.67 (m, 1 H), 1.58-1.50 (m, 2 H), 1.05 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 3 H); 95% ee, GC (γ-TA), injection 120°C, column 100°C, pressure 100Kpa, 29.6 min (minor) (3S, 4R), 36.8 min (major) (3R, 4S).

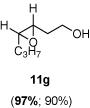

11g

Yield, 90%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) 3.90-3.84 (m, 2 H), 3.11-3.08 (m, 1 H), 2.97-2.96 (m, 1 H), 1.89-1.87 (m, 2 H), 1.72-1.70 (m, 1 H), 1.54-1.50 (m, 4 H), 1.00 (t, J = 7.6 Hz, 3 H); 97% ee, GC (γ-TA), injection 140°C, column 120°C, pressure 100Kpa, 18.4 min (minor), 19.6 min (major).

11h

Yield, 91%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) 3.90-3.85 (m, 2 H), 3.11-3.08 (m, 1 H), 2.96-2.95 (m, 1 H), 1.86-1.85 (m, 2 H), 1.70-1.67 (m, 1 H), 1.56-1.38 (m, 6 H), 0.94 (t, J = 7.5 Hz, 3 H); 99% ee, GC (γ-TA), injection 140°C, column 120°C, pressure 100Kpa, 26.1 min (minor), 28.4 min (major).

11i

Yield, 90%; 1H NMR (400 MHz, CDCl3) 3.80-3.78 (m, 2 H), 3.50 (br, 1 H), 3.10-3.07 (m, 1 H), 2.96-2.95 (m, 1 H), 1.85-1.83 (m, 1 H), 1.69-1.66 (m, 1 H), 1.54-1.52 (m, 4 H), 1.36-1.33 (m, 4 H), 0.92 (t, J = 6.9 Hz, 3 H); 13C NMR (100 MHz, CDCl3) 60.2 (CH2), 56.9 (CH), 54.9 (CH), 31.4 (CH2), 30.6 (CH2), 27.8 (CH2), 26.1 (CH2); 22.5 (CH2), 13.9 (CH3); 99% ee, GC (γ-TA), injection 140°C, column 120°C, pressure 100Kpa, 41.8 min (minor), 45.1 min (major).

4.6. Procedure for kinetic resolution of secondary allylic alcohols in the presence of VO(OPri)3 and ligand 3

To a solution of 3a (0.0420 mmol) in dichloromethane (1 mL) was added VO(OPri)3 (0.0050 mL, 0.0208 mmol), and the mixture was stirred for 1 h at room temperature. The resulting solution was cooled to 0 °C, and then 70% aqueous tert-butylhydroperoxide (TBHP) (0.44 mL, 3.18 mmol) and secondary allylic alcohol 12 (2.10 mmol) were added and stirring was continued at the same temperature for 12 d. [The process of conversion was monitored by HPLC: saturated aqueous Na2SO3 was added to a small portion of reaction mixture (0.05 mL), and the mixture was stirred for 30 min at 0 °C. The mixture was then allowed to warm to room temperature, extracted with Et2O, dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure.] Saturated aqueous Na2SO3 was added when the conversion was over 51%, and the mixture was stirred for 1 h at 0 °C. The mixture was then allowed to warm to room temperature, extracted with Et2O, dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure. The remaining residue was purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel to provide the secondary allylic alcohol 13 and the epoxy alcohol 14. Ee values of 13 and 14 were determined by chiral HPLC.7

4.7. Procedure for kinetic resolution of homoallylic alcohols in the presence of VO(OPri)3 and ligand 3h

To a solution of 3h (35.2 mg, 0.0210 mmol) in toluene (0.25 mL) was added VO(OPri)3 (0.0025 mL, 0.0104 mmol), and the mixture was stirred for 8 h at room temperature. 88% cumene hydroperoxide (CHP) (0.37 mL, 1.47 mmol) and homoallylic alcohol 15 (racemic, 2.10 mmol) were then added and stirring was continued at the same temperature for 30 h. [The process of conversion was monitored by GC.] Saturated aqueous Na2SO3 was added when the conversion reached 50%, and the mixture was stirred for 1 h at 0 °C. The mixture was then allowed to warm to room temperature, extracted with Et2O, dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure. The remaining residue was purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel to provide the homoallylic alcohols 16 and the epoxy alcohols 17, Ee values of 16 and 17 were determined by chiral GC.8

4.8. General procedure for asymmetric oxidation of olefins in the presence of MoO2(acac)2 and ligand 3

To a solution of BHA (0.022 mmol) in dichloromethane (1 mL) was added MoO2(acac)2 (5 mg, 0.02 mmol), and the mixture was stirred for 1 h at room temperature. To the resulting solution, olefin 18 (1.0 mmol), and alkyl hydroperoxide (1.5 mmol) were added and stirring was continued at the same temperature for several hours. The process of oxidation was monitored by TLC. Saturated aqueous Na2SO3 was added, and the mixture was stirred for 30 min at room temperature. The mixture was extracted with CH2Cl2, dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure. The remaining residue was purified by flash column (Ethyl Acetate:Hexanes 1:50) chromatography on silica gel to provide epoxide 19

4.9. General procedure for asymmetric oxidation of sulfides in the presence of MoO2(acac)2 and ligand 3

To a solution of BHA (0.03 mmol) in dichloromethane (3 mL) was added MoO2(acac)2 (5 mg, 0.015 mmol), and the mixture was stirred for 1 h at room temperature. The resulting solution was cooled to 0 °C, and then sulfide 20 (0.75 mmol), and THP (207 mg, 0.75 mmol) were added and stirring was continued at the same temperature for several hours. The process of oxidation was monitored by TLC. Saturated aqueous Na2SO3 was added, and the mixture was stirred for 30 min at 0 °C. The mixture was then allowed to warm to room temperature, extracted with CH2Cl2, dried over Na2SO4 and concentrated under reduced pressure. The remaining residue was purified by flash column chromatography on silica gel to provide sulfoxide 21.

Scheme 5.

Kinetic resolution of homoallylic alcohols.

Acknowledgments

Support for this research was provided by SORST project of the Japan Science and Technology Agency (JST), GAANN, National Institutes of Health (NIH) GM068433-01, Merk Research Laboratories, and a starter grant from The University of Chicago.

Footnotes

This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.For recent reviews, see Katsuki T. In: Comprehensive Asymmetric Catalysis. Jacobsen EN, Pfaltz A, Yamamoto H, editors. Vol. 2. Berlin: Springer; 1999. p. 621. Katsuki T, Ojima I. Org. React. 1996;48:1. Keith JM, Larrow JF, Jacobsen EN. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2001;343:5. Adam W, Saha-Möller CR, Ganeshpure PA. Chem. Rev. 2001;101:3499. doi: 10.1021/cr000019k. Adam W, Malisch W, Roschmann KJ, Möller CR, Schenk WA. J. Organomet. Chem. 2002;661:3. Lattanzi A, Scettri A. J. Organomet. Chem. 2006;691:2072. Shi Y. Acc. Chem. Res. 2004;37:488. doi: 10.1021/ar030063x. Shi Y, Frohn M. Synthesis. 2000;14:1979.

- 2.(a) Katsuki T, Sharpless KB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1980;102:5974. [Google Scholar]; (b) Rossiter BE, Sharpless KB. J. Org. Chem. 1984;49:3707. [Google Scholar]; (c) Gao Y, Hanson RM, Klunder JM, Ko SY, Masamune H, Sharpless KB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1987;109:5765. [Google Scholar]

- 3.For recent reports on chiral vanadium catalyst for epoxidation, see Bryliakov KP, Talsi EP. Kinetics and Catalysis (Translation of Kinetika i Kataliz) 2003;44:334. Bolm C, Kuhn T. Synlett. 2000:899. Traber B, Jung YG, Park TK, Hong JI. Bull. Korean Chem. Soc. 2001;22:547. Wu HL, Uang BJ. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2002;13:2625. Bourhani Z, Malkov AV. Chem. Commun. 2005:4592. doi: 10.1039/b509436d. Lattanzi A, Piccirillo S, Scettri A. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2005:1669.

- 4.For recent reports on achiral metal catalyst and chiral oxidant see Adam W, Alsters PL, Neumann R, Saha-Möller CR, Seebach D, Beck AK, Zhang R. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:8222. doi: 10.1021/jo034923z. Adam W, Beck AK, Pichota A, Saha-Möller CR, Seebach D, Vogl N, Zhang R. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2003;14:1355. Adam W, Alsters PL, Neumann R, Saha-Möller CR, Seebach D, Zhang R. Org. Lett. 2003;5:725. doi: 10.1021/ol027498p.

- 5.For recent reviews on vanadium see, Hirao T. Chem. Rev. 1997;97:2707. doi: 10.1021/cr960014g. Bolm C. Coordination Chemistry Reviews. 2003;237:245.

- 6.For Zr catalyzed epoxidation of homoallylic alcohols, see Ikegami S, Katsuki T, Yamaguchi M. Chem. Lett. 1987:83. Okashi T, Murai N, Onaka M. Org. Lett. 2003;5:85. doi: 10.1021/ol027261t.

- 7.Zhang W, Basak A, Kosugi Y, Hoshino Y, Yamamoto H. Angew, Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:4389. doi: 10.1002/anie.200500938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang W, Yamamoto H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:286. doi: 10.1021/ja067495y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Barlan A, Bask A, Yamamoto H. Angew, Chem. Int. Ed. 2006;45:45849. doi: 10.1002/anie.200601742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Basak A, Barlan A, Yamamoto H. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2006;17:508. [Google Scholar]

- 11.a) Murase N, Hoshino Y, Oishi M, Yamamoto H. J. Org. Chem. 1999;64:338. [Google Scholar]; b) Hoshino Y, Murase N, Oishi M, Yamamoto H. Bull. Chem. Soc. Jpn. 2000;73:1653. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hoshino Y, Yamamoto H. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:10452. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Makita N, Hoshino Y, Yamamoto H. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2003;42:941. doi: 10.1002/anie.200390250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Berrisford DJ, Bolm C, Sharpless KB. Angew. Chem. 1995;107:1159. [Google Scholar]; Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1995;34:1059. [Google Scholar]

- 15.See experimental part.

- 16.Vanadium-3c complex in the presence of TBHP selectively oxidized geraniol to generate 2,3-epoxygeraniol.

- 17.Bortolini O, Campestrini S, Furia E, Modena G. J. Org. Chem. 1987;52:5093. [Google Scholar]

- 18.a) Sheng MN, Zajaczek GJ. ARCO, GB 1.136.923. 1968; b) Kolar J, Halcon US 3.350.422, US 3.351.635. 1967

- 19.a) Yamada S, Mashiko T, Tershima S. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1977;99:1988. [Google Scholar]; b) Michaelson RC, Palermo RE, Sharpless KB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1977;99:1990. [Google Scholar]; c) Kuhn F, Zhao J, Herrmann WA. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2005;16:3469. and references cited therein. [Google Scholar]

- 20.a) Ambroziak K, Peloch R, Milchert E, Dziemboska T, Rozwadowski Z. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2004;211:9. [Google Scholar]; b) Masteri-Farahani M, Farzaneh F, Ghandhi M. J. Mol. Cat A: Chem. 2003;192:103. [Google Scholar]; c) Kotov S, Kolev T, Georgrieva M. J. Mol. Cat. A: Chem. 2003;195:83. [Google Scholar]; c) Gonclaves I, Santos A, Romao C, Lopes A, Rodriguez-Borges J, Pillinger M, Ferriera P, Rocha J, Kuhn R. J. Organomet. Chem. 2001;626:1. [Google Scholar]; d) Wang X, Shi H, Sun C, Zhang Z. Tetrahedron. 2004;60:10993. [Google Scholar]; e) Fridgen J, Herrmann WA, Eickerling G, Santos A, Kuhn F. J. Organomet. Chem. 2004;689:2752. [Google Scholar]

- 21.a) Raina S, Singh V. Tetrahedron. 1995;51(8):2467. [Google Scholar]; b) Corey EJ, Noe M, Shieh W. Tetrahedron Letters. 1993;34(38):5995. [Google Scholar]

- 22.a) Deubal D, Sundermeyer J, Frenking G. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:10101. [Google Scholar]; b) Deubal D, Sundermeyer J, Frenking G. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2001:1819. [Google Scholar]; c) Yadanov I, Valentin C, Gisdakis P, Rosch N. J. Mol. Cat. A: Chem. 2000;158:189. [Google Scholar]; d) Mimoun H. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 1982;21:734. [Google Scholar]; e) Deubal D, Frenking G, Gisdakis P, Herrmann WA, Rosch N. J. Sundermeyer, Acc. Chem. Res. 2004;37:645. doi: 10.1021/ar0400140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; f) Sharpless KB, Townsend JM, Williams DR. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1972;94:295. [Google Scholar]

- 23.For recent reviews see Fernandez I, Khiar N. Chem.Rev. 2003;103:3651. doi: 10.1021/cr990372u. Volcho KP, Kurbakova SY, Korchagina DV, Suslov EV, Salakhutdinov NF, Toktarev AV, Echevskii GV, Barkhash VA. J Molr Cat. A: Chem. 2003;195:263. Jacobsen EN, Pfaltz A, Yamamoto H, editors. Comprehensive Asymmetric Catalysis I–III. Berlin: Springer; 1999. Ojima I, editor. Catalytic Asymmetric Synthesis. New York: Wiley-VCH, Inc; 2000. p. 327. Backvall J-E, editor. Modern Oxidation Methods. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 2004. Backvall J-E, editor. Weinheim: Wiley-VCH; 2004.

- 24.(a) Blum SA, Bergman RG, Ellmann J. J. A. J. Org. Chem. 2003;68:150. doi: 10.1021/jo0205560. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Vetter A, Berkessel A. Tetrahedron Letters. 1998;39:1741. [Google Scholar]; (c) Drago C, Caggiano L, Jackson RFW. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2005;44:7221. doi: 10.1002/anie.200503046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (d) Sun J, Chenjan Z, Dai Z, Yang M, Dan Y, Hu H. J. Org. Chem. 2004;69:8500. doi: 10.1021/jo040221d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (e) Bolm C, Bienewald F. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 1995;34:2640. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Palucke M, Hanson P, Jacobson EN. Tetrahedron Letters. 1992;33:7111. See references cited therein. [Google Scholar]

- 26.(a) Legros J, Bolm C. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2004;43:4225. doi: 10.1002/anie.200460236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; (b) Legros J, Bolm C. Chem. Eur. J. 2005;11:1086. doi: 10.1002/chem.200400857. See references cited therein. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Massa A, Francesca R, Siniscalchi R, Bugagtti V, Lattanzi A, Scettri A. Tetrahedron: Asymmetry. 2002;13:1277. See references cited therein. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Capozzi MAM, Cardellicchio C, Naso F, Tortorella P. J. Org. Chem. 2000;65:2843. doi: 10.1021/jo991912q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.(a) Bortolini O, Campestrini S, Furia FD, Modena G. J. Org. Chem. 1987;52:5093. [Google Scholar]; (b) Schurig V, Hinzer K, Layer A, Mark C. J. Organmet. Chem. 1989;370:81. [Google Scholar]; (c) Ambroziak K, Peloch R, Milchert E, Dziemboska T, Rozwadowski Z. J. Mol. Catal. A: Chem. 2004;211:9. [Google Scholar]; (d) Masteri-Farahani M, Farzaneh F, Ghandhi M. J. Mol. Cat A: Chem. 2003;192:103. [Google Scholar]; (e) Kotov SV, Kolev TM, Georgrieva MG. J. Mol. Cat. A: Chem. 2003;195:83. [Google Scholar]; (f) Wahl G, Sundermeyer J. Chem. Eur. J. 1999;5:3230. [Google Scholar]; (g) Winter W, Mark C, Schurig V. Inorg. Chem. 1980;19:2045. [Google Scholar]; (h) Bonchio M, Carofiglio T, Di Furia F, Fornasier R. J. Org. Chem. 1995;60:5986. [Google Scholar]; (i) Batigalhia F, zaldin-Hernandez M, Ferreira AG, Malvestiti I, Cass QB. Tetrahedron. 2001;57:9669. [Google Scholar]