Abstract

Patients with hepatitis C who live in rural and low socioeconomic communities often lack access to specialty care. Over the past 7 years, we have provided telemedicine consultations at the Peach Tree Clinic, located in rural northern California. We performed a retrospective analysis of our experience. During this time period we provided consultations for 103 patients with hepatitis C; 37% had cirrhosis, and 64% had never undergone therapy with interferon and ribavirin. Twenty-three percent of the patients were candidates for therapy. The most common contraindication to therapy was the severity of their disease and the risk of decompensation. Fifteen patients were evaluated for liver transplant; 2 were listed but none survived long enough to receive a liver transplant. Our data suggest that there is a large number of patients with hepatitis C and advanced liver disease living in rural communities, some of whom may need treatment or liver transplant. Telemedicine is an effective tool for identifying and treating patients with hepatitis C who live in rural communities.

Key words: telemedicine, hepatitis C, rural, access to care, liver cirrhosis, interferon, ribavirin

Introduction

Chronic hepatitis C (HCV) is an important health problem in both urban and rural communities. It is estimated that approximately 3.5 million people in the United States are infected with HCV and 85% are chronically infected.1 Given the high prevalence of this disease and lack of specialty care in many rural communities, primary healthcare providers are increasingly being called upon to diagnose and treat patients with HCV. Unfortunately, many primary care healthcare providers are unprepared to evaluate and manage patients with HCV and practice patterns are variable.2 One potential tool that has not been well studied or utilized to bridge the gaps of primary care physician's screening, diagnosis, and treatment of patients with HCV is telemedicine. Telemedicine in this case is the use of high-speed, wide bandwidth transmission of digitized signals in conjunction with computers to provide an audiovisual interaction in real-time between a patient and physician who are physically separated. We hypothesize that a hepatology telemedicine clinic will increase access to specialty care especially among those with advanced disease living in an underserved community.

Methods

In 2000, we established a telemedicine linkage site at the Peach Tree Clinic in Marysville, California, which serves patients from both Marysville and adjoining Yuba City. Marysville has a population of 12,268, 15% of whom live below the federal poverty line. Yuba City has a population of 36,758, and 14.5% of the population lives below the poverty level.3 Over the past 7 years we have seen a total of 103 patients through telemedicine consultations with the patient and their primary care provider present during the consultation. We performed a retrospective study of these patients and recorded information in regards to age, race, gender, weight, reason for consultation, stage of liver disease, genotype, treatment status, type of medical insurance, and the number referred for liver transplantation.

Results

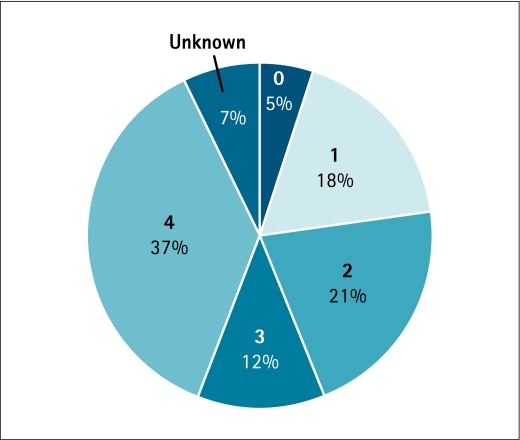

Between 2000 and 2007, we evaluated 103 patients with hepatitis C via telemedicine at the Peach Tree Clinic. The patient characteristics are shown in Table 1 and the stage of their disease on initial telemedicine evaluation in Figure 1. Among the 41 patients with cirrhosis, 15 patients (37%) were referred for liver transplant and 2 were listed but died prior to liver transplant. Sixty-five patients (63%) were treatment naïve, and of those who underwent prior treatment (n = 33), 51% were nonresponders and 21% relapsers and 27% had an unknown response. Treatment with long-acting interferon and ribavirin was recommended to 19 patients, and 14 were initiated on therapy. Of the 14 patients who were treated with interferon and ribavirin therapy, 5 achieved sustained viralogic response (SVR), 3 are still on therapy and 4 did not respond. The two most common reasons for not recommending treatment were risk for decompensation (19%) and medical noncompliance (19%). Other reasons for not recommending treatment included medical comorbidities (10%), and active substance abuse (7%).

Table 1.

Characteristics of Patients with Hepatitis C Who Were Evaluated via Telemedicine

| Male |

47% |

| Female |

53% |

| Weight (mean) |

88.46 kg |

| Age (mean) |

49 years |

| Patient Insurance | |

| No Insurance |

6% |

| County |

25% |

| Medi-CAL |

61% |

| Medicare |

6% |

| Private Insurance |

2% |

| Viral genotype | |

| 1 |

71% |

| 2 |

11% |

| 3 |

15% |

| 4 |

2% |

| 6 |

1% |

| Viral Load > 450,000 IU |

37% |

| Cirrhosis |

37% |

| MELD > 12 |

19% |

| Treatment-naïve |

64% |

| Treatment Recommended | 23% |

Fig. 1.

Stage of patients with hepatitis C virus (HCV) evaluated by telemedicine. (0 = stage 0 fibrosis, 1 = stage 1 fibrosis, 2 = stage 2 fibrosis, 3 = stage 3 fibrosis, 4 = stage 4 fibrosis, according to the Knodell score).

Discussion

Telemedicine has been used as an effective tool to improve access to care in many different specialties, but is ideally suited for the evaluation of patients with hepatitis C in rural areas. The evaluation and treatment of hepatitis C is largely based on the combination of history, laboratory, and histopathologic data and has been done using electronic medical records and telemedicine.4–6 Residents of rural communities face higher poverty rates, have fewer doctors, hospitals, and other health resources, and experience increased difficulty getting to health services.7 Those who suffer from hepatitis C in these communities are often of low socioeconomic status; even if a specialist is available in their community, they often cannot be seen or their care is markedly delayed due to their lack of financial resources. This is suggested by our cohort of patients of whom over 30% had cirrhosis at the time of their initial visit, most of whom had MediCal (Medicaid) insurance, which reimburses physicians relatively less compared to private insurance.

Patients who lack access to a specialist are less likely to be treated. Although this may be a reflection of referral bias, a hepatology specialist (or gastroenterologist) is more likely to treat patients with HCV compared to primary care physicians.8 In our cohort there were 65 patients who were never treated with interferon or ribavirin, yet only 14 were referred for treatment via telemedicine. The most common reason for not initiating therapy was risk of decompensation of their already severe disease. Our data suggest that had these patients been evaluated earlier, they may have been treatment candidates.

Telemedicine consultations with a hepatologist may also increase identification of patients who are candidates for liver transplantation. In our cohort we identified 15 patients who were evaluated for liver transplant and 2 who were acceptable for listing.

Despite this being a retrospective and single-center experience, our data suggest that telemedicine is an effective outreach tool for patients with hepatitis C and government funded medical insurance living in rural areas. Among this patient population, there appears to be a high percentage of advanced liver disease, some of whom may be appropriate for treatment with interferon and ribavirin or referral.

Acknowledgment

We would like to thank Dr. Joseph Coulter and his staff at Peach Tree Clinic in Marysville, California, for pioneering the concept of using telemedicine to manage hepatitis C patients in the primary care setting of a rural area in California. We finally acknowledge the work of Stacey L. Cole from the Center for Health and Technology at the University of California Davis for assisting with the data collection.

Disclosure Statement

This publication was made possible by Grant Number RR 024146 from the National Center for Research Resources (NCRR), a component of the National Institutes of Health (NIH), and NIH Roadmap for Medical Research. Its contents are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official view of NCRR or NIH. Information on NCRR is available at http://www.ncrr.nih.gov/. Information on Re-engineering the Clinical Research Enterprise can be obtained from http://nihroadmap.nih.gov/clinicalresearch/overview-translational.asp.

Christopher Aoki is supported by P01 CA109091-01A1S (Liver Cancer Control Interventions for Asian Americans) funded by the National Cancer Institute's Center to Reduce Cancer Health Disparities and by the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities. However, the views presented in this paper do not necessarily represent the views of the funding agencies.

Lorenzo Rossaro receives consulting fees and advisory board fees from Roche Laboratories and Schering Corporation. He also receives lecture fees from speaking at the invitation of Roche Laboratory, Schering Corporation, and Three Rivers Pharmaceuticals. He also receives grant support from Roche Laboratory, Schering Plough Research Institute, Vertex, and Novartis.

All other authors have no competing financial interests.

References

- 1.Alter MJ. Kruszon-Moran D. Nainan OV. McQuillan GM. Gao F. Moyer LA. Kaslow RA. Margolis HS. The prevalence of hepatitis C virus infection in the United States, 1988 through 1994. N Engl J Med. 1999;341:556–562. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199908193410802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yawn BP. Wollan P. Gazzuola L. Kim WR. Diagnosis and 10-year follow-up of a community-based hepatitis C cohort. JFam Pract. 2002;51:135–140. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.U.S. Census Bureau, Census 2000: Yuba City, CA and Marysville, CA, Demographic Profile Highlights. http://factfinder.census.gov. [Nov 11;2008 ]. http://factfinder.census.gov

- 4.Rossaro L. Tran TP. Ransibrahmanakul K. Rainwater JA. Csik G. Cole SL. Prosser CC. Nesbitt TS. Hepatitis C videoconferencing: The impact on continuing medical education for rural healthcare providers. TelemedJEHealth. 2007;13:269–277. doi: 10.1089/tmj.2006.0050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Arora S. Thornton K. Jenkusky SM. Parish B. Scaletti JV. Project ECHO: Linking university specialists with rural and prison-based clinicians to improve care for people with chronic hepatitis C in New Mexico. Public Health Rep. 2007;122(Suppl 2):74–77. doi: 10.1177/00333549071220S214. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Arora S. Geppert CM. Kalishman S. Dion D. Pullara F. Bjeletich B. Simpson G. Alverson DC. Moore LB. Kuhl D. Scaletti JV. Academic health center management of chronic diseases through knowledge networks: Project ECHO. Acad Med. 2007;82:154–160. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e31802d8f68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Improving Health Care for Rural Populations. Research in Action Fact Sheet. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research; Rockville, MD: [Nov 11;2008 ]. AHCPR Publication No. 96-P040, March 1996. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rocca LG. Yawn BP. Wollan P. Kim WR. Management of patients with hepatitis C in a community population: Diagnosis, discussions, and decisions to treat. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2:116–124. doi: 10.1370/afm.62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]