Abstract

CatSper family proteins are putative ion channels expressed exclusively in membranes of the sperm flagellum and required for male fertility. Here, we show that mouse CatSper1 is essential for depolarization-evoked Ca2+ entry and for hyperactivated movement, a key flagellar function. CatSper1 is not needed for other developmental landmarks, including regional distributions of CaV1.2, CaV2.2, and CaV2.3 ion channel proteins, the cAMP-mediated activation of motility by  , and the protein phosphorylation cascade of sperm capacitation. We propose that CatSper1 functions as a voltage-gated Ca2+ channel that controls Ca2+ entry to mediate the hyperactivated motility needed late in the preparation of sperm for fertilization.

, and the protein phosphorylation cascade of sperm capacitation. We propose that CatSper1 functions as a voltage-gated Ca2+ channel that controls Ca2+ entry to mediate the hyperactivated motility needed late in the preparation of sperm for fertilization.

Judged by the criterion of widespread use, the 9 + 2 axoneme is a highly successful design, driving the cilia and flagella of algae, protozoa, and our own airway epithelia and spermatozoa. Past work agrees that Ca2+ controls the swimming behavior of sperm and of other single, motile cells that use this marvelous axonemal engine (1–4). There, consensus stops abruptly. Decades of study have not revealed how Ca2+ targets axonemal components to alter ciliary and flagellar waveform and thus produce responses to external stimuli (5). For sperm, the uncertain identity of the ion channels used to create instructive Ca2+ signals is another particularly challenging unanswered question (6). Although the list of candidate channels is long, only CatSper1 (7) and CatSper2 (8, 9) are known to be required for male fertility. Discovery that CatSper1 and CatSper2 are novel, sperm-specific putative ion channels presents an opportunity for fresh approaches to the unanswered questions of how Ca2+ signals are generated in the sperm flagellum and of the roles of these signals in control of flagellar function.

Mammalian sperm are stored in a quiescent state in the epididymis and become active only after release into the female reproductive tract. This begins a process, termed “capacitation,” that prepares them for fertilization. Thus, sperm become nearly inaccessible to experimentation during the period when they are physiologically most active and interesting. Fortunately, several of the important components of capacitation can be studied by using epididymal sperm examined under conditions intended to produce capacitation in vitro. These components include three Ca2+-dependent events: an initial activation, later hyperactivation of motility (10), and the delayed engagement of a protein kinase cascade (11). We have examined the involvement of CatSper1 in each of these events, and find that only hyperactivation requires CatSper1. The Ca2+ dependence of bicarbonate-mediated activation of motility, documented here, apparently involves another route for entry of Ca2+.

Materials and Methods

Sperm Preparation and Incubation Conditions. A colony of mice was established from founders carrying the Catsper1 null mutation in a 129/SvJ + C57BL/6J genetic background (7) by backcrossing for three to four generations into the C57BL/6J strain. The experiments here used F1 and F2 animals from this colony. One series of experiments (those of Fig. 4A) used Swiss–Webster “retired breeder” male mice obtained from a commercial source. As in prior work (12, 13), cauda epididymal sperm were prepared from male mice killed by CO2 asphyxiation. Briefly, the cleaned, excised epididymides were rinsed with medium Na7.4 (in mM): 135 NaCl, 5 KCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 MgSO4, 20 Hepes, 5 glucose, 10 lactic acid, 1 pyruvic acid, adjusted to pH 7.4 with NaOH. The tissue was transferred to a “swimout/capacitation medium” that comprised medium Na7.4 with BSA (5 mg/ml) and NaHCO3 (15 mM). Semen was allowed to exude (15 min at 37°C, 5% CO2) from 5–10 small incisions. All subsequent operations were at room temperature (22–25°) in medium Na7.4, unless otherwise noted. Sperm were washed twice and then dispersed and stored at 1–2 × 107 cells per ml. Potassium-evoked responses were produced with medium K8.6 (in mM): 135 KCl, 5 NaCl, 2 CaCl2, 1 Mg SO4, 30 TAPS [N-tris(hydroxymethyl)-methyl-3-aminopropanesulfonic acid], 10 glucose, 10 lactic acid, 1 pyruvic acid, adjusted to pH 8.6 with NaOH. For incubation under capacitating conditions, stored sperm were sedimented and resuspended in the original volume of warmed swimout/capacitation medium. After 90 min at 37°C with 5% CO2, cells were again sedimented and returned to medium Na7.4 with or without added 15 mM NaHCO3.

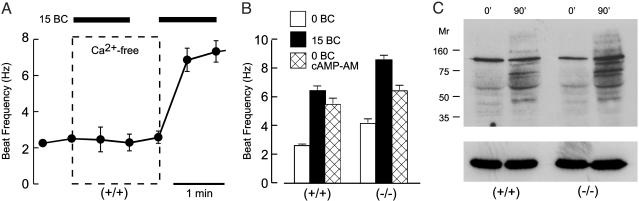

Fig. 4.

CatSper1 is not required for the Ca2+-dependent activation of the flagellar beat or protein tyrosine phosphorylation. (A) Waveform analysis monitored flagellar beat frequency during sequential perfusion of wild-type (+/+) sperm (n = 3). Bar indicates supplementation of media with 15 mM NaHCO3 (15 BC). Dashed box encloses the interval when media were nominally free of Ca2+. (B) Parallel experiments with wild-type (+/+) and CatSper1 null (–/–) sperm randomly sampled after 1–10 min incubation in media lacking or containing 15 mM NaHCO3 to stimulate production of cAMP. Alternatively, cAMP was generated by incubating sperm for 30 min with the membrane-permeant acetoxymethyl ester cAMP-AM (60 μM; n = 16–28 cells in four independent experiments). Error bars indicate SEM. (C) Wild-type (+/+) and CatSper1 null (–/–) sperm were incubated in capacitating conditions for 0 and 90 min. Samples of 106 cells were processed for SDS/PAGE immunoblotting with an anti-phosphotyrosine antibody. The same blot was stripped and reprobed with an anti-tubulin antibody as a control for equal sample loading (Lower).

Immunocytochemistry and Immunoblots. Sperm were probed with the affinity-purified antibodies anti-CNB1, anti-CNC1, or anti-CNE2 by using methods for confocal immunomicroscopy as described (12, 13). For anti-phosphotyrosine Western blot analysis, 1 × 106 cells were sedimented, resuspended in 1 ml PBS with 1 mM sodium vanadate, and again sedimented. Total sperm proteins were extracted in an equal volume of a 2× Laemmli buffer, heated 5 min at 100°C, and then clarified by centrifugation at 10,000 × g for 5 min and adjusted to 5% mercaptoethanol. Proteins were separated on a 4–12% gradient SDS/PAGE gel and transferred onto nitrocellulose membranes. Before incubation with antibodies, nonspecific binding was blocked with PBS containing 5% IgG-free BSA for 1 h. Blots were incubated with a 1:1,000 dilution of the anti-phosphotyrosine primary antibody (PY-Plus mouse anti-phosphotyrosine mixture, Zymed) for 1 h and then washed with 0.1% Tween in TBS (four times for 5 min). Under the same conditions, blots were then incubated with horseradish peroxidase-labeled secondary antibody (donkey anti-mouse IgG; Jackson ImmunoResearch) diluted 1:50,000 in PBS. Finally, blots were washed with 0.1% Tween in TBS (four times for 5 min) and treated with enhanced chemiluminescence detection reagents for 5 min.

Dye Loading and Photometry. Indo-1 acetoxymethyl ester (AM) was dispensed from 2 mM stocks in DMSO, dispersed in 10–15% Pluronic 127, diluted to 20 μM in 0.25 ml medium Na7.4, and then immediately mixed with an equal volume of the sperm suspension. After 15–20 min, cells were diluted in 1 ml of medium Na7.4, sedimented, and then resuspended in fresh medium and incubated for 1–5 h before use.

Cells (10 μl) were applied and allowed to settle for ≈5 min on ≈5-mm-square no. 00 coverslips. A local perfusion device with an estimated exchange time of <0.5 s applied various test solutions. Photometric measurements were made as described (13, 14) and analyzed in Igor (Wavemetrics, Lake Oswego, OR). Statistical analyses were performed in excel (Microsoft, Redmond, WA). All results are presented as mean ± SEM except as noted.

Permeant Ester Loading of cAMP. The cAMP-AM was dispensed from a 20 mM stock in DMSO, dispersed in 10–15% Pluronic 127, diluted to 120 μM in 0.25 ml of medium Na7.4, and then immediately mixed with an equal volume of a sperm suspension that had or had not received preliminary loading with indo-1 AM. After 30 min, an aliquot (5–10 μl) was added to the sample chamber for imaging. Cells were examined with protocols that minimized the duration of perfusion to thereby reduce washout of the membrane-permeant ester (15).

Waveform Analysis. Images for waveform analysis were collected as described (14). Briefly, cells were examined with a ×40, 0.65 numerical aperture objective on an inverted microscope (Nikon Diaphot). Brief flashes (1–2 ms) of illuminating light, produced by a custom-built stroboscopic power supply, were triggered once-per-frame by a synchronization signal from the controller module of the frame-transfer cooled charge-coupled device camera (TCP512; Roper Scientific, Trenton, NJ). Images were collected at 30 Hz from a 128 × 128-pixel region of the camera chip, under the direction of metamorph (Universal Imaging, Downington, PA) and stored in TIFF format. Subsequent analysis used software routines written in igor (Wavemetrics, Lake Oswego, OR) that provided flagellar beat frequency and amplitude, and evaluated the angular deviation (tangent angle) at 0.5-μm intervals along the length of the traced flagellum (arc length). The time-averaged tangent angle vs. length-along-the-flagellum data (shear curves) provides a measure of flagellar beat asymmetry (2); for a general discussion of polymer mechanics and its analysis, see ref. 16.

Results

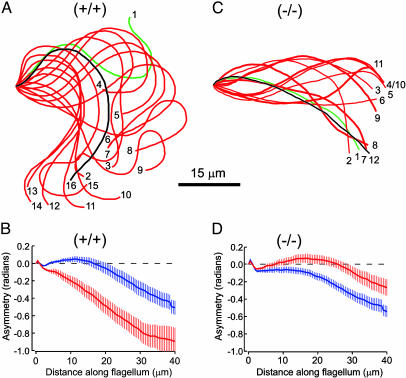

Hyperactivation Requires CatSper1. Sperm observed within the oviduct at the site and near the time of fertilization have a striking hyperactivated motility characterized by a high-amplitude, asymmetric waveform (17, 18). These properties are retained by sperm retrieved from the oviduct (19) and are reproduced by capacitation in vitro (10). Fig. 1A illustrates the hyperactivated waveform observed for a wild-type mouse sperm tethered to a glass surface and examined by the waveform analysis system developed in this lab. The aligned and numbered flagellar traces are from successive stop-motion video frames taken at 33-ms intervals. They capture one beat cycle. The “whiplash” character and slowed frequency of hyperactivated movement (26) is most apparent in Movies 1 and 2, which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site. Although simple visual inspection confirms the asymmetric nature of the hyperactivated waveform, the time-averaged distribution of flagellar bending (2, 14, 16) provides a quantitative measure (Fig. 1B). For sperm examined before capacitating incubations, this asymmetry parameter deviated only slightly from zero in the proximal 20 μm of the flagellum. At 40 μm, asymmetry reached –0.4 radian. After incubation under capacitating conditions, the asymmetry parameter deviated by >0.5 radian at 20 μm and reached nearly –1 radian at 40 μm along the flagellum.

Fig. 1.

CatSper1 is required for Ca2+-mediated hyperactivation. (A and C) Aligned flagellar waveform traces for a wild-type sperm (+/+) and CatSper1 null sperm (–/–) examined after 1.5-h incubation under capacitating conditions to produce hyperactivation. For the wild-type sperm, one full beat cycle occupied 16 video frames (528 ms). The low frequency and high amplitude of the flagellar beat are hallmarks of hyperactivated motility. The CatSper1 null sperm completed two beat cycles in 12 video frames (396 ms). The high frequency and low amplitude of the beat are hallmarks of the activated motility produced by  . (B and D) Flagellar asymmetry reported by time-averaged tangent angles for wild-type (+/+) and null (–/–) sperm, examined before (blue) and after (red) capacitating incubations (n = 11). Error bars indicate SEM.

. (B and D) Flagellar asymmetry reported by time-averaged tangent angles for wild-type (+/+) and null (–/–) sperm, examined before (blue) and after (red) capacitating incubations (n = 11). Error bars indicate SEM.

Sperm from CatSper1 null mice did not develop the large-amplitude, asymmetric waveform found for hyperactivated wild-type sperm (Fig. 1C). Before capacitating incubations, the asymmetry for CatSper1 null sperm (Fig. 1D) was similar to that of wild-type sperm, deviating <0.4 radian in the proximal 40 μm of the flagellum. After capacitating incubation, asymmetry actually decreased (deviating <0.2 radian along the proximal flagellum) and displayed a small positive bias.

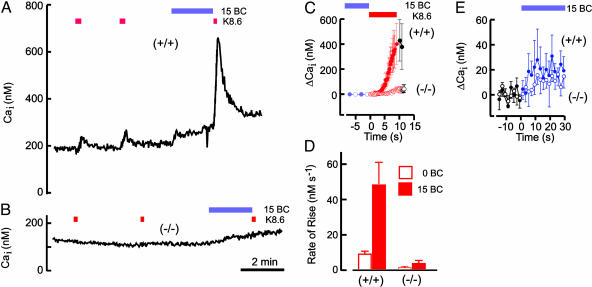

Evoked Ca2+ Entry also Requires CatSper1. In the early stages of the capacitation sequence, several events require the  anion in pathways that involve cAMP and protein kinase A (20, 21). One of these initial events is a rapid facilitation of sperm voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (13, 14). In Fig. 2A, sperm of a wild-type mouse received two brief applications of the depolarizing medium K8.6, which opens voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, causing intracellular [Ca2+] to increase slightly. After recovery and a brief conditioning exposure to 15 mM NaHCO3, a third stimulus evoked a much faster and larger Ca2+ increase. In sharp contrast, sperm of a CatSper1 null mouse (Fig. 2B) showed little or no depolarization-evoked Ca2+ increase, either before or after conditioning with

anion in pathways that involve cAMP and protein kinase A (20, 21). One of these initial events is a rapid facilitation of sperm voltage-gated Ca2+ channels (13, 14). In Fig. 2A, sperm of a wild-type mouse received two brief applications of the depolarizing medium K8.6, which opens voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, causing intracellular [Ca2+] to increase slightly. After recovery and a brief conditioning exposure to 15 mM NaHCO3, a third stimulus evoked a much faster and larger Ca2+ increase. In sharp contrast, sperm of a CatSper1 null mouse (Fig. 2B) showed little or no depolarization-evoked Ca2+ increase, either before or after conditioning with  . Aligned and averaged traces from four separate experiments, each using paired wild-type and null animals, show the consistent nature of this dramatic difference (Fig. 2C). Because sperm recover very slowly from imposed Ca2+ loads (time constant 45–60 s; refs. 13 and 22), the rate of Ca2+ rise calculated during the 10-s depolarizing stimulus is a good measure of the relative number of open Ca2+ channels. For wild-type sperm,

. Aligned and averaged traces from four separate experiments, each using paired wild-type and null animals, show the consistent nature of this dramatic difference (Fig. 2C). Because sperm recover very slowly from imposed Ca2+ loads (time constant 45–60 s; refs. 13 and 22), the rate of Ca2+ rise calculated during the 10-s depolarizing stimulus is a good measure of the relative number of open Ca2+ channels. For wild-type sperm,  increased the K+-evoked rate of rise from 10 ± 2to50 ± 8 nM·s–1, a 5-fold facilitation of ion channel function. CatSper1 null sperm had barely measurable averaged rates of rise of 2 ± 1 and 5 ± 2 nM·s–1 under these conditions (Fig. 2D).

increased the K+-evoked rate of rise from 10 ± 2to50 ± 8 nM·s–1, a 5-fold facilitation of ion channel function. CatSper1 null sperm had barely measurable averaged rates of rise of 2 ± 1 and 5 ± 2 nM·s–1 under these conditions (Fig. 2D).  alone produced barely detectable increases in Ca2+ in either wild-type or mutant sperm (Fig. 2E).

alone produced barely detectable increases in Ca2+ in either wild-type or mutant sperm (Fig. 2E).

Fig. 2.

CatSper1 is required for evoked entry of Ca2+. (A) Indo-1 photometry monitored free internal Ca2+ concentration (Cai) during perfusion of wild-type (+/+) sperm. Bars indicate supplementation of control medium with 15 mM NaHCO3 (15 BC) or replacement with alkaline high-K+ medium K8.6. (B) Parallel experiment with CatSper1 null (–/–) sperm. (C) Aligned and averaged responses to depolarizing stimuli (red) applied after conditioning medium (blue). (D) Averaged rates of rise evoked by depolarization applied before (0 BC) and after (15 BC) conditioning with bicarbonate. (E) Responses during application of the conditioning medium containing 15 mM NaHCO3. For C–E, n = 12 in four independent experiments. Error bars indicate SEM.

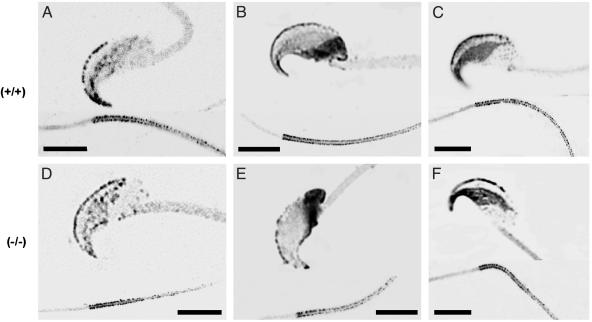

Regional Distributions of CaV Channels Unaffected in CatSper1 Mutants. Although Fig. 2 demonstrates a requirement for CatSper1 in evoked entry of Ca2+, it still offers only indirect evidence that CatSper1 functions as the Ca2+ entry channel. Various of the conventional CaV voltage-gated Ca2+ channels also are present and presumably function in sperm (12, 13, 23) with roles determined in part by their distinct subcellular distributions. The characteristic patterns of CaV1.2, CaV2.2, and CaV2.3 immunoreactivity in the head of wild-type sperm (Fig. 3 A–C) follow regional boundaries, which define the exocytotic acrosome and the equatorial segment, where fusion with the egg initiates. In a shared pattern, CaV1.2, CaV2.2, and CaV2.3 immunoreactive puncta are somewhat irregularly distributed along the principal piece of the flagellum. The patterns of immunoreactivity are unaltered in CatSper1 null sperm (Fig. 3 D–F). Thus, we can exclude the possibility that loss of evoked Ca2+ entry results from disruption of the regional distributions of CaV channel proteins that are established during spermiogenesis.

Fig. 3.

CatSper1 is not needed for regional distribution of CaV ion channel proteins. Confocal immunofluorescence images shown in reverse contrast for wild-type (+/+) and CatSper1 null (–/–) sperm treated with antibodies directed to the CaV1.2 (A and D); CaV2.2 (B and E); and CaV2.3 (C and F) channel proteins. Each panel contains representative images of central optical sections from the head (above) and the proximal flagellum (below). (Scale bars = 5 μm.)

Accelerating Action of Bicarbonate Unaffected in CatSper1 Mutants. An activation of sperm motility, initiated by the  anion present in reproductive fluids, is a very early component of sperm capacitation. A severalfold acceleration of the flagellar beat is produced within seconds of exposing sperm to

anion present in reproductive fluids, is a very early component of sperm capacitation. A severalfold acceleration of the flagellar beat is produced within seconds of exposing sperm to  (14). As with the facilitating action of

(14). As with the facilitating action of  on evoked Ca2+ entry, this response follows stimulation of the atypical sperm adenylyl cyclase (24, 25) and requires cAMP-mediated protein phosphorylation by protein kinase A (14).‡‡

on evoked Ca2+ entry, this response follows stimulation of the atypical sperm adenylyl cyclase (24, 25) and requires cAMP-mediated protein phosphorylation by protein kinase A (14).‡‡

We now find that this normal action of  on the flagellar beat also requires extracellular Ca2+ (Fig. 4A). For “resting” wild-type sperm, examined before exposure to

on the flagellar beat also requires extracellular Ca2+ (Fig. 4A). For “resting” wild-type sperm, examined before exposure to  , the flagellar beat frequency is 2–3 Hz. The beat is unaffected when

, the flagellar beat frequency is 2–3 Hz. The beat is unaffected when  is applied in the absence of Ca2+ but increases to >7 Hz when Ca2+ is restored. These results strongly suggest that an entry of Ca2+ is required for the accelerating action of

is applied in the absence of Ca2+ but increases to >7 Hz when Ca2+ is restored. These results strongly suggest that an entry of Ca2+ is required for the accelerating action of  , consistent with early work showing a Ca2+ requirement for

, consistent with early work showing a Ca2+ requirement for  accumulation of cAMP in sperm (27) and with recent demonstrations of synergistic effects of Ca2+ and

accumulation of cAMP in sperm (27) and with recent demonstrations of synergistic effects of Ca2+ and  on the recombinant atypical adenylyl cyclase of sperm (28). Our new findings might suggest that the loss in evoked Ca2+ entry for CatSper1-deficient sperm (Fig. 2) should prevent the accelerating action of

on the recombinant atypical adenylyl cyclase of sperm (28). Our new findings might suggest that the loss in evoked Ca2+ entry for CatSper1-deficient sperm (Fig. 2) should prevent the accelerating action of  . However, Fig. 4B clearly shows that CatSper1 is not required for the action of

. However, Fig. 4B clearly shows that CatSper1 is not required for the action of  . These experiments also show that CatSper1 is not required for the action of cAMP generated experimentally from its membrane-permeant AM, providing additional assurance that CatSper1 is not required for events downstream of cAMP production.

. These experiments also show that CatSper1 is not required for the action of cAMP generated experimentally from its membrane-permeant AM, providing additional assurance that CatSper1 is not required for events downstream of cAMP production.

The original description of the CatSper1 null mice found that the male infertility phenotype correlated with decreased sperm swimming speeds (7). Therefore we expected waveform analysis to report decreased flagellar beat frequencies for CatSper1 null sperm. To the contrary, we find greater beat frequencies for resting sperm of mutant than for wild-type mice (Fig. 4B). However, the animals used here had been backcrossed with another strain for several generations (see Materials and Methods). Thus, changes in the genetic background of the animals may explain the improved basal motility of the sperm used here compared with those used in the original study.

Protein Tyrosine Phosphorylation Unaffected in CatSper1 Mutants. Another potential role for CatSper1 is in the protein phosphorylation cascade of capacitation. Past work (11) shows that a delayed increase in protein tyrosine phosphorylation occurs during capacitation in vitro. The pathway also involves activation of cAMP-dependent protein kinase. It requires  and Ca2+ and additional components of the capacitating medium. For Fig. 4C, Western immunoblots of sperm extracts were prepared from wild-type and CatSper1 null sperm before and after capacitating incubations. Before capacitation, the predominant phosphotyrosine immunoreactive band migrated at ≈115 kDa, characteristic of the constitutively phosphorylated hexokinase of sperm (29). After capacitation, phosphotyrosine immunoreactivity of both wild-type and CatSper1 sperm increased to a similar extent and with a similar band pattern. Thus, CatSper1 is not required for the signaling cascade that produces the delayed increase in protein tyrosine phosphorylation essential for subsequent acrosomal exocytosis and fertilization.

and Ca2+ and additional components of the capacitating medium. For Fig. 4C, Western immunoblots of sperm extracts were prepared from wild-type and CatSper1 null sperm before and after capacitating incubations. Before capacitation, the predominant phosphotyrosine immunoreactive band migrated at ≈115 kDa, characteristic of the constitutively phosphorylated hexokinase of sperm (29). After capacitation, phosphotyrosine immunoreactivity of both wild-type and CatSper1 sperm increased to a similar extent and with a similar band pattern. Thus, CatSper1 is not required for the signaling cascade that produces the delayed increase in protein tyrosine phosphorylation essential for subsequent acrosomal exocytosis and fertilization.

Discussion

Taken together, the work here provides insights into Ca2+ signaling in the sperm flagellum. Foremost, we see that CatSper1 has an unexpectedly prominent role. The requirement of CatSper1 for depolarization-evoked entry of Ca2+ supports the hypothesis that CatSper1 forms functional voltage-gated Ca2+ entry channels in the membrane of the flagellum, alone or with unidentified partners that perhaps include CatSper2 or other CatSper family proteins (8, 9, 30).

Equally important, we link the prominent role of CatSper1 as a flagellar Ca2+ entry channel to a specific crucial event: the control of hyperactivation, a major flagellar function that is engaged near the time and at the site of fertilization. This requirement of CatSper1 for hyperactivated motility is consistent with the known Ca2+ dependence of hyperactivation (31) and with the presence of CatSper1 in flagellar membranes (7). As noted previously (32), it is also consistent with the ability of CatSper1 null sperm to penetrate zona-free, but not zona-intact, eggs (7).

Past work (7) showed that CatSper1 resembles a single poreforming repeat from the CaV family of four-repeat, voltage-gated Ca2+ channel proteins. Nevertheless, a predicted sensitivity to depolarization, and even the ability to act as an ion channel, was not verified by exogenous expression. Instead, CatSper1 was found to be required for transient increases in Ca2+ observed during treatment of sperm with 8-bromo-cAMP (8Br-cAMP), suggesting that CatSper1 could function as a cyclic-nucleotidegated Ca2+ entry channel. We now find that treatment with  to increase cAMP production has a CatSper1-dependent facilitating action on evoked Ca2+ entry. However, we find little evidence of direct opening of a Ca2+ entry channel. These negative results suggest that the reported responses of sperm to 8-bromo-cAMP (7) or other cyclic nucleotide analogs (33) may have resulted from channel facilitation rather than from direct gating.

to increase cAMP production has a CatSper1-dependent facilitating action on evoked Ca2+ entry. However, we find little evidence of direct opening of a Ca2+ entry channel. These negative results suggest that the reported responses of sperm to 8-bromo-cAMP (7) or other cyclic nucleotide analogs (33) may have resulted from channel facilitation rather than from direct gating.

So far, we lack definitive evidence that conventional CaV channels are required for depolarization-evoked Ca2+ entry, and still lack direct evidence that CatSper1 forms voltage-gated channels. If the Ca2+ entry monitored here and in earlier work (13, 14, 22) does occur solely through CatSper1-containing channels, then past studies of the pharmacology of evoked entry (13) and of its modulation by cAMP-dependent protein kinase (14, 26) apply to those channels.

This study makes three additions to the list of events that are unaffected by targeted deletion of CatSper1 from sperm: regional distributions of CaV channel proteins, the  activation of motility, and the protein tyrosine phosphorylation of capacitation. The proposed role of CatSper1 as the route for an entry of Ca2+ that is required for hyperactivated motility thus adds to the emerging picture that the CatSper ion channel proteins are attractive targets in the development of new nonhormonal contraceptives and improved methods for screening and treatment of male infertility.

activation of motility, and the protein tyrosine phosphorylation of capacitation. The proposed role of CatSper1 as the route for an entry of Ca2+ that is required for hyperactivated motility thus adds to the emerging picture that the CatSper ion channel proteins are attractive targets in the development of new nonhormonal contraceptives and improved methods for screening and treatment of male infertility.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Drs. Joseph Beavo, William A. Catterall, and William Zagotta for critical reading of an early version of this manuscript, and Dr. William A. Catterall for antibodies to CaV channel proteins. This work was supported by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute (D.E.C., D.R., and D.L.G.); the Cecil H. and Ida Green Center for Reproductive Biology Sciences (T.Q. and D.L.G.); National Institutes of Health Grants NIGMS-NRSA-T32-GM07270 (to A.E.C.), NICHD-HD36022 (to T.Q. and D.L.G.), and NIDR-DE13531 (to R.E.W.); and through agreement U54-HD12629 of the Specialized Cooperative Centers Program in Reproduction Research, National Institute of Child Health and Human Development (to B.H. and D.F.B.).

Abbreviation: AM, acetoxymethyl ester.

Footnotes

Also see Nolan, M. A., Wennemuth, G., Burton, K. A., McKnight, G. S. & Babcock, D. F. (2002) Mol. Cell. Biol. 13, 385 (abstr.).

References

- 1.Naitoh, Y. & Kaneko, H. (1972) Science 176, 523–524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brokaw, C. J. (1979) J. Cell Biol. 82, 401–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bessen, M., Fay, R. B. & Witman, G. B. (1980) J. Cell Biol. 86, 446–455. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lindemann, C. B. & Goltz, J. S. (1988) Cell Motil. Cytoskeleton 10, 420–431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Smith, E. F. (2002) Mol. Biol. Cell 13, 3303–3313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Publicover, S. J. & Barratt, C. L. (1999) Hum. Reprod. 14, 873–879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ren, D., Navarro, B., Perez, G., Jackson, A. C., Hsu, S., Shi, Q., Tilly, J. L. & Clapham, D. E. (2001) Nature 413, 603–609. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Quill, T. A., Ren, D., Clapham, D. E. & Garbers, D. L. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 12527–12531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Quill, T. A., Sugden, S. A., Rossi, K. L., Doolittle, L. K., Hammer, R. E. & Garbers, D. L. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 14869–14874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yanagimachi, R. (1994) in The Physiology of Reproduction, eds. Knobil, E. & Neill, J. D. (Raven, New York), pp. 189–317.

- 11.Visconti, P. E., Moore, G. D., Bailey, J. L., Leclerc, P., Connors, S. A., Pan, D., Olds-Clarke, P. & Kopf, G. S. (1995) Development 121, 1139–1150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Westenbroek, R. E. & Babcock, D. F. (1999) Dev. Biol. 207, 457–469. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wennemuth, G., Westenbroek, R. E., Xu, T., Hille, B. & Babcock, D. F. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 21210–21217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wennemuth, G., Carlson, A. E., Harper, A. J. & Babcock, D. F. (2003) Development 130, 1317–1326. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Schultz, C., Vajanaphanich, M., Genieser, H. G., Jastorff, B., Barrett, K. E. & Tsien, R. Y. (1994) Mol. Pharmacol. 46, 702–728. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Howard, J. (2001) Mechanics of Motor Proteins and the Cytoskeleton (Sinauer, Sunderland MA), pp. 99–116.

- 17.Katz, D. F. & Yanagimachi, R. (1980) Biol. Reprod. 22, 759–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Suarez, S. S. & Osman, R. A. (1987) Biol. Reprod. 36, 1191–1198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Overstreet, J. W., Katz, D. F. & Johnson, L. L. (1980) Biol. Reprod. 22, 1083–1088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Harrison, R. A. (2003) Reprod. Domest. Anim. 38, 102–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Skalhegg, B. S., Huang, Y., Su, T., Idzerda, R. L., McKnight, G. S. & Burton, K. A. (2002) Mol. Endocrinol. 16, 630–639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wennemuth, G., Babcock, D. F. & Hille, B. (2003) J. Gen. Physiol. 122, 115–128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Serrano, C. J., Trevino, C. L., Felix, R. & Darszon, A. (1999) FEBS Lett. 462, 171–176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Chen, Y., Cann, M. J., Litvin, T. N., Iourgenko, V., Sinclair, M. L., Levin, L. R. & Buck, J. (2000) Science 289, 625–628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jaiswal, B. S. & Conti, M. (2001) J. Biol. Chem. 276, 31698–31708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ishijima, S., Baba, S. A., Mohri, H. & Suarez, S. S. (2002) Mol. Reprod. Dev. 61, 376–384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Garbers, D. L., Tubb, D. J. & Hyne, R. V. (1982) J. Biol. Chem. 257, 8980–8984. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jaiswal, B. S. & Conti, M. (2003) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 100, 10676–106781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Visconti, P. E., Olds-Clarke, P., Moss, S. B., Kalab, P., Travis, A. J., de las Heras, M. & Kopf, G. S. (1996) Mol. Reprod. Dev. 43, 82–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lobley, A., Pierron, V., Reynolds, L., Allen, L. & Michalovich, D. (2003) Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 1, 53–67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yanagimachi, R. (1982) Gamete Res. 5, 323–344. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Garbers, D. L. (2001) Nature 413, 581–582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wiesner, B., Weiner, J., Middendorff, R., Hagen, V., Kaupp, U. & Weyand, I. (1998) J. Cell Biol. 142, 473–484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.