Abstract

Dopaminergic D1/D5-receptor-mediated processes are important for certain forms of memory as well as for a cellular model of memory, hippocampal long-term potentiation (LTP) in the CA1 region of the hippocampus. D1/D5-receptor function is required for the induction of the protein synthesis-dependent maintenance of CA1-LTP (L-LTP) through activation of the cAMP/PKA-pathway. In earlier studies we had reported a synergistic interaction of D1/D5-receptor function and N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA)-receptors for L-LTP. Furthermore, we have found the requirement of the atypical protein kinase C isoform, protein kinase Mζ (PKMζ) for conventional electrically induced L-LTP, in which PKMζ has been identified as a LTP-specific plasticity-related protein (PRP) in apical CA1-dendrites. Here, we investigated whether the dopaminergic pathway activates PKMζ. We found that application of dopamine (DA) evokes a protein synthesis-dependent LTP that requires synergistic NMDA-receptor activation and protein synthesis in apical CA1-dendrites. We identified PKMζ as a DA-induced PRP, which exerted its action at activated synaptic inputs by processes of synaptic tagging.

Neuromodulatory systems influence functional plasticity and memory formation (Izquierdo and Medina 1997; Izquierdo and McGaugh 2000; Frey and Frey 2008). Beside the role of other neuromodulators, dopamine (DA) plays a major role in learning and synaptic plasticity, especially in the hippocampal CA1 region (Frey et al. 1990; Frey and Morris 1998a; Lisman and Otmakhova 2001; Jay 2003; Wise 2004; Bethus et al. 2010), where it can be considered as a required cofactor for prolonged changes rather than just a neuromodulator. The mesolimbic system as well as the hippocampus are important brain structures for the formation of distinct memory (Lisman and Grace 2005). Long-term potentiation (LTP), the proposed cellular basis of memory formation, in the hippocampal CA1 can be separated by the use of either protein synthesis inhibitors or dopaminergic receptor blockers into a transient E-LTP and a prolonged long-lasting L-LTP (beyond 4 h, requiring associative heterosynaptic induction and protein synthesis; (Frey et al. 1988, 1990, 1991b, 1993; Huang and Kandel 1995; Frey and Morris 1998a; Frey 2001). The dopaminergic receptors activate—via a synergistic interaction with NMDA-receptor activation—the cAMP/PKA pathway, which, in turn, is a necessary step for L-LTP induction (Frey et al. 1993; Frey 1996, 2001; Abel et al. 1997; Frey and Morris 1998a; Swanson-Park et al. 1999; Navakkode et al. 2007). Huang and Kandel (1995) showed that the application of D1/D5-receptor agonists can induce LTP of field excitatory postsynaptic potentials (Field-EPSP) in the CA1, which occluded a potentiation induced by cAMP agonists. These data were verified by our own work (Frey 1996; Sajikumar and Frey 2004; Navakkode et al. 2007). Moreover, DA D1/D5-receptor agonists have been shown to facilitate the induction of CA1- (Otmakhova and Lisman 1996; Lemon and Manahan-Vaughan 2006) and dentate gyrus-LTP (Kusuki et al. 1997), whereas D1/D5-receptor antagonists prevented the maintenance of CA1-LTP (Frey et al. 1991b; Lemon and Manahan-Vaughan 2006). However, in a recent study Mockett et al. (2004) were unable to replicate the pharmacological induction of LTP by the application of D1/D5-receptor agonists, although D1/D5-receptor activation synergistically increased cAMP production in CA1. They suggested that D1/D5-receptor activation in CA1 initiates intracellular second messenger accumulation that was insufficient by itself to induce an activity-independent L-LTP. The investigators conclude that the principal role of dopamine in the hippocampus is to modulate rather than to initiate long-lasting synaptic plasticity, and that this can occur, in part, through a synergistic action with NMDA receptor activation, a result recently confirmed in our laboratory (Navakkode et al. 2007).

Because of the importance of DA function in learning and functional plasticity, here we searched for the postsynaptic target of DA activation with respect to its mechanism of potentiation and the critical regulation of this mechanism in apical dendrites of the CA1 region. We found that application of DA initiates an activity-dependent potentiation that is mediated by PKMζ.

Results

DA application and its effect at apical CA1-dendrites

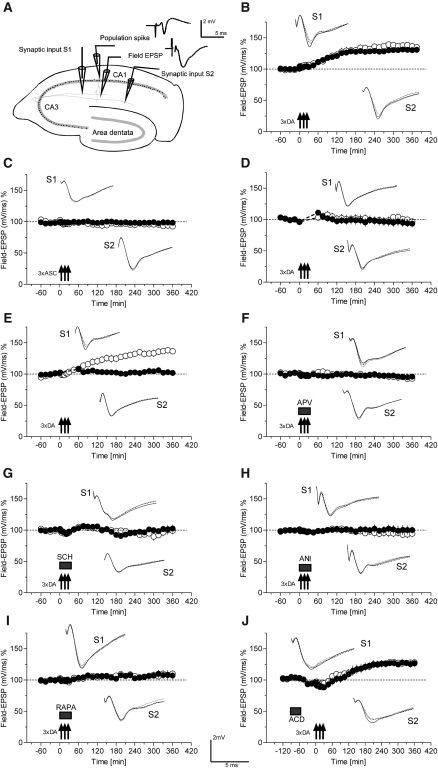

After recording a stable baseline for 1 h, DA was applied for three short time periods to the slice (5 min per application). As seen in Figure 1B, this application paradigm caused a slow onset, but stable L-LTP in S1 (filled circles) as well as in S2 (open circles). The potentials in S1 and S2 were significantly different from 45 min onward when compared with its own baseline before drug application (Wilcoxon-test; P < 0.05). Figure 1C represents the effect of the antioxidant ascorbic acid as used in all DA-application experiments on baseline recordings. In contrast to Figure 1B, there was no effect seen in synaptic inputs S1 and S2. Baseline values remained stable throughout the time period of recording of 6 h (Wilcoxon-test; P > 0.05). Next, we investigated whether control stimulation is required to observe the DA-induced delayed-onset potentiation presented in Figure 1B. DA was applied to the bath medium (Fig. 1D), but in both synaptic inputs S1 and S2, the baseline recordings were suspended for the time of DA application and for a subsequent 1 h (broken line in Fig. 1B). In both synaptic inputs S1 and S2, potentials remained stable at baseline levels, and there was no significant potentiation compared with its own baseline values before drug application (Wilcoxon-test; P > 0.05). In Figure 1E, DA was applied to the bath medium, but (open circles) test pulses were applied only in S1 for the subsequent hour, whereas test stimulation to S2 (filled circles) was suspended for that hour. DA induced a slow-onset and stable L-LTP in S1 (which received also glutamatergic input-specific stimulation) that was significantly different from 45 min onward, compared with its own baseline (Wilcoxon-test; P < 0.05), and S1 was statistically different from S2 starting from 105 min after drug application until the end of the experiment (U-test; P < 0.05). Thus, glutamatergic test stimulation was required for the delayed-onset potentiation to occur.

Figure 1.

DA-induced long-lasting potentiation and its properties. (A) Illustration of a transverse hippocampal slice with the location of the electrodes. Two stimulation electrodes of independent synaptic inputs S1 and S2 to the same neuronal population and the recording sites for the population spike amplitude and the Field-EPSP as well as representative recording traces are shown. For clarity, only the time course of the Field-EPSP is shown. Open circles always represent synaptic input S1, whereas filled circles represent input S2. (B) Threefold application of 50 µM DA produces synaptic potentiation (arrows always indicate the application of DA-ascorbic acid pulses; n = 10). DA was applied for 5 min at 10-min intervals together with ascorbic acid, as an antioxidant, at a concentration of 1 mM. (C) Control experiments with the application of 1 mM ascorbic acid alone show no effect (three pulses for 5 min at 10-min intervals; n = 8). (D) DA-mediated potentiation requires afferent stimulation. After recording a stable baseline of 1 h, DA (always with ascorbic acid) was applied in three pulses (n = 8). However, in both synaptic inputs S1 (open circle) and S2 (filled circle), the baseline recordings were suspended from the time of DA application for a subsequent 1 h (broken line). (E) Similar to D: After recording a stable baseline for 1 h, DA was applied in three pulses (n = 6). In S1 (open circle), baseline recordings were continued also during and after DA application; however, in S2 (filled circle), recordings were suspended from the time of DA application for 1 h. (F) DA and ascorbic acid were co-applied with 50 µM APV in three pulses for 5 min at 10-min intervals (n = 8). No differences from baseline values were detected in S1 or S2 (Wilcoxon-test; P > 0.05). (G) DA and ascorbic acid were co-applied with 0.1 µM SCH23390 in three pulses for 5 min at 10-min intervals (n = 7). (H) DA and ascorbic acid were co-applied with 25 µM anisomycin (ANI) in three pulses for 5 min at 10-min intervals (n = 8). (I) As in H, but instead of anisomycin, rapamycin was co-applied (0.1 µM; n = 6). (J) After recording a stable baseline for 30 min, actinomycin D (25 µM) was applied for 30 min (i.e., from –90 to –60 min) and then after a washout of 1 h, DA and ascorbic acid were applied in three pulses for 5 min at 10-min intervals (n = 7). Open circles always indicate synaptic input S1, and filled circles synaptic input S2. Arrows indicate the application of DA+ascorbic acid. The boxes represent the time points of drug application (APV–D-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid; SCH–SCH23390; ANI–anisomycin; RAPA–rapamycin; ACD–actinomycin D). Analog traces represent typical potentials 30 min before pulsed drug application (dotted line), 60 min after pulsed drug application (perforated line), and 6 h after pulsed drug application (closed line).

We then applied DA together with test stimulation, but in the presence of the NMDA-receptor blocker APV (Fig. 1F). There was no statistically significant change from baseline levels in either S1 or S2 (Wilcoxon-test; P > 0.05). Furthermore, if the D1/D5-receptor blocker SCH23390 was applied together with DA, the developing potentiation was also prevented (Fig. 1G). These results suggest that a synergistic activation of NMDA- and dopaminergic D1/D5-receptors are required for the DA-induced delayed-onset potentiation to occur. If the DA-induced potentiation resembles a protein synthesis-dependent L-LTP (Frey and Frey 2008), it should be dependent on new protein synthesis. Therefore, we co-applied the reversible protein synthesis inhibitor anisomycin with DA. As seen in Figure 1H, no potentiation occurred—again, no changes from baseline levels in S1 or S2 could be detected (Wilcoxon-test; P > 0.05). We then investigated whether PRP-synthesis is restricted to dendrites using the mTOR-pathway inhibitor rapamycin. Application of rapamycin also prevented the DA-induced potentiation. As seen in Figure 1I, the values of S1 and S2 remained stable at baseline levels throughout the time period of recording when compared with its own baseline (Wilcoxon-test; P > 0.05). The maintenance of LTP in rats can be partially prevented by mRNA-synthesis inhibition during the first 8 h under distinct conditions (Otani et al. 1989; Frey et al. 1996; Frey and Frey 2008) if the irreversible drugs were applied before or shortly after tetanization (Frey et al. 1996; Frey and Frey 2008). In some studies the drugs were applied during LTP induction by tetani or pharmacological activation of the cAMP/PKA-pathway and left in the bath medium for a prolonged time (Nguyen et al. 1994; Ahmed and Frey 2003), which resulted in a faster decay of LTP. These studies, however, cannot fully rule out nonspecific effects of the irreversible drugs on LTP induction as well as on its maintenance (for review, see Frey and Frey 2008). To avoid the latter, we have therefore investigated whether the irreversible mRNA-synthesis blocker actinomycin D would have an effect on the DA-induced potentiation if it was applied 1 h before DA application. As seen in Figure 1J, no effect was observed. Irrespective of the mRNA-synthesis blockade, a statistically significant potentiation in both S1 and S2 was detected (S1, from 150 min onward, compared with its baseline prior to drug application, and S2, from 165 min onward, compared with its baseline prior to drug application [Wilcoxon-test; P < 0.05]). Although any difference was statistically nonsignificant, application of actinomycin D followed by DA may have slightly affected the onset of the DA-induced delayed-onset potentiation by about 1 h, as compared with the time course presented in Figure 1B. It remains unclear whether this apparent slight depression/delay might be due to a nonspecific effect of actinomycin D. A direct effect of mRNA-synthesis causing a minimal depression is unlikely because of the short period of time in which the delay was observed. Future experiments should investigate whether time points beyond 6 h after DA application can be affected by mRNA-synthesis inhibition.

DA-induced long-lasting potentiation: Induction and requirement of PKMζ synthesis

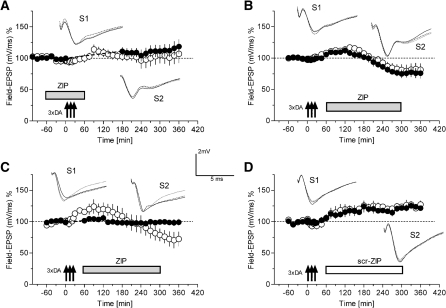

Conventional, electrically induced NMDA-receptor-dependent L-LTP requires the synthesis of the LTP-specific PRP PKMζ (Sajikumar et al. 2005b; Yao et al. 2008). We therefore examined whether the protein synthesis-dependent, DA-induced potentiation is also dependent on PKMζ. Figure 2A represents the time course if the inhibitory ζ pseudosubstrate peptide ZIP was present when DA was applied. In this series, synaptic input S1 (open circles) was continuously recorded, whereas input S2 was suspended for 3 h starting at the time point of DA application (filled circles and dashed line). No slow-onset potentiation was detected in S1 or in S2; as well, no statistical significant changes of the potentials in S1 and S2 were observed when compared with pre-drug levels, suggesting that PKMζ is required for the DA-induced delayed-onset potentiation. If PKMζ was indeed a DA-induced, delayed-onset potentiation-mediating PRP, the maintenance of that potentiation should also be reversed if ZIP was applied during its maintenance phase (for comparison, see Sajikumar et al. 2005b). Therefore, in the next series of experiments DA was applied three times, followed by the application of the inhibitory peptide ZIP 1 h later (Fig. 2B). After DA application a transient and weak form of a delayed-onset potentiation was seen (statistically different at 90 min), which was maintained up to 120 min after DA and 60 min after ZIP application. Thereafter, potentiation of both inputs returned first to baseline levels with a subsequent lasting depression 270 min after DA application when compared with their own control level before DA application (Wilcoxon-test, P < 0.05). We now wanted to study whether suspension of test stimulation could affect that result (Fig. 2C). Therefore, we applied ZIP 1 h after DA application until the 5-h time point. In S1 (open circles) baseline recordings were made as normal, whereas in S2 (filled circles) recordings were suspended for 1 h from the time point of DA application. DA induced a transient slow-onset potentiation that was significantly different from its own baseline from 45 to 120 min after DA application before it came back to baseline with a subsequent development of a lasting depression, which was statistically significant 300 min after DA application (Wilcoxon-test; P < 0.05). Potentials in the suspended input S2 remained stable at baseline levels throughout the entire experiment. Finally, we repeated the series of experiments shown in Figure 2B; however, instead of ZIP, a scrambled control-peptide, scr-ZIP, was applied. The DA-induced delayed-onset potentiation was not affected by scr-ZIP; it was significantly different from pre-drug application levels from the 135-min time point onward in both inputs S1 and S2 (Wilcoxon-test; P < 0.05).

Figure 2.

DA-induced long-lasting potentiation: requirement of PKMζ for induction and maintenance. The time courses of Field-EPSPs of two separate synaptic inputs S1 (open circles) and S2 (filled circles) are shown. (A) In this experiment (n = 10), the PKMζ-inhibitor, ZIP (2.5 µM) was applied 60 min before threefold application of 50 µM DA and 1 mM ascorbic acid (in the following, referred to as DA application). ZIP was washed out 60 min after DA application. Input S1 (open circles) was recorded continuously, whereas input S2 was suspended for 3 h starting at the time point of DA application (filled circles; dashed line). (B) DA was applied after recording a baseline for 1 h in S1 and S2. Sixty minutes later, ZIP was applied for up to 300 min after DA application (n = 7). (C) After recording a stable baseline of 1 h, DA was applied (n = 7). ZIP was applied 60 min after DA application until the 300-min time point. In S1, baseline recordings were made as normal, whereas in S2, recordings were suspended for 1 h from the time point of DA application (broken line). (D) DA application followed by myristoylated-scrambled-ZIP application 60–300 min after DA (n = 5). Open circles always indicate synaptic input S1 and filled circles synaptic input S2. Arrows indicate the application of DA+ascorbic acid. The boxes represent the time points of drug application (gray boxes: myristolated-ZIP [ZIP]; open box: scrambled-ZIP [scr-ZIP]). Analog traces represent typical potentials 30 min before pulsed drug application (dotted line), 60 min after pulsed drug application (perforated line), and 6 h after pulsed drug application (closed line).

DA-induced long-lasting potentiation: Spaced-associative interaction with other synaptic inputs by processes of “synaptic tagging”

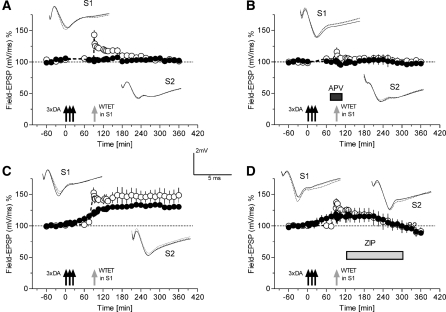

Our data suggest that DA-application together with NMDA-receptor function results in a delayed-onset potentiation in apical CA1-dendrites that shows characteristic features of the late phase of LTP: i.e., it requires new protein synthesis and depends for its maintenance on the LTP-specific PRP, PKM. If so, then it might be possible to study whether processes of synaptic tagging can be seen. Separate synaptic inputs should be able to benefit from the availability of PKMζ induced by the synergistic interaction of synapse-specific glutamatergic activation and nonsynapse-specific DA-application (“DA-induced LTP”) if at those separated synapses a synaptic tag is set, i.e., by the application of a weak tetanization (WTET) (Frey and Morris 1998b). It is well established that E-LTP requires NMDA-receptor activation. Thus, Figure 3A represents the first series of experiments undertaken to verify synaptic tagging processes and DA-induced-LTP. We first applied DA, but suspended control stimulation for 1 h in both S1 and S2, preventing the synergistic NMDA-receptor function necessary for the induction of the late event. Then, 90 min after DA application, we applied a WTET to S1 (open circles). Just a transient E-LTP was observed in S1 for the first 180 min after WTET to S1, before the potentials returned to baseline levels as compared with its own pretetanus baseline (Wilcoxon-test; P > 0.05). S2 (filled circles), which received DA with suspended stimulation, and no tetanus, remained stable at baseline levels. Figure 3B represents a similar experiment as in Figure 3A, but now, during the time of WTET to S1, the NMDA-receptor blocker APV was applied. No E-LTP in S1 or significant changes in baseline levels of either input was detected. After these control experiments, we then applied DA to S1 and S2 (Fig. 3C); however, in S1 (open circles) we suspended the control stimulation for 1 h (broken line in S1, open circles, Fig. 3C). DA application resulted in its long-lasting delayed-onset potentiation in input S2 (filled circles; significantly different from the 45 min time point onward, when compared with its own baseline; Wilcoxon-test; P < 0.05). Input S1 (open circles), however, remained shortly after the recording suspension still at baseline levels. Then, 90 min after DA application and 30 min after the end of recording suspension, a WTET was now applied to S1 that normally only induced an E-LTP (see A). But now, after the development of the DA-induced late-onset potentiation in input S2 (filled circles), the E-LTP in S1 (open circles) was transformed into L-LTP. The question arises as to whether this prolongation of E-LTP was just a result of the parallel development of the DA-induced potentiation or whether it was indeed a result of capturing the PRP PKMζ. We therefore repeated the experiment shown in Figure 3C, but applied the PKMζ-inhibitor peptide, ZIP, 30 min after WTET to S1. The time course of both inputs was similar as that described in Figure 2B. The maintenance of the delayed-onset potentiation in S2 (Fig. 3D, filled circles) was reversed after about 180 min and—most interestingly—E-LTP in S1 was not transformed into L-LTP, supporting our hypothesis that the WTET to S1 (Fig. 3D, open circles) set a tag, but that the action of the LTP-specific PRP, PKMζ, to maintain potentiation, provided by the DA application and the NMDA-receptor activation of the S2 pathway, was prevented by the inhibitory ZIP. Thus, the persistent potentiation in both pathways was blocked.

Figure 3.

DA-induced long-lasting potentiation: Spaced-associative interaction with other synaptic inputs by processes of “synaptic tagging.” The time courses of Field-EPSPs of two separate synaptic inputs S1 (open circles) and S2 (filled circles) are shown. (A) After recording a stable baseline of 1 h, DA and ascorbic acid was applied (n = 7). In both inputs S1 and S2, the baseline recordings were then suspended from the time point of DA application for 1 h (broken line). After that, baseline was recorded for another 30 min in both inputs. Potentials remained stable as compared with their own baselines prior to drug application (Wilcoxon-test; P > 0.05). In S1, but not in S2, a WTET was then induced 90 min after DA application (i.e., 30 min after resuming the baseline recordings). (B) Similar to A; however, APV was applied 30 min before WTET to S1 and washed out 30 min after WTET (n = 6). (C) DA was applied to S1 and S2, and recording was suspended in S1 for 1 h after DA application, but not suspended for S2 (n = 9). Thirty min after restarting recording in S1, a WTET was applied. (D) Similar to C but ZIP was applied 120 min after DA application and washed out at the 300-min time point after DA application (n = 4). Open circles always indicate synaptic input S1 and filled circles synaptic input S2. Analog traces represent typical field EPSPs 30 min before (dotted line) and 60 min (dashed line) and 270 min (solid line) after weak tetanization of input S1. Arrows indicate the time point of tetanization of the corresponding synaptic input. Symbols as in Figures 1 and 2; gray arrows represent the time point of the application of WTET in S1.

Discussion

Short-term concomitant activation of DA and NMDA receptors can induce a prolonged, delayed-onset synaptic potentiation in hippocampal apical CA1-dendrites that requires newly synthesized proteins for 6 h and possibly newly synthesized mRNA for later time points. It has been shown that the degree of actinomycin D binding to DNA in chromatin is dependent upon the state of repression of chromatin (Berlowitz et al. 1969). Since we do not yet know the basal accessibility in vivo of genomic loci relevant for LTP or the conformational changes triggered by LTP induction, the repression of transcription achieved by application of actinomycin D at different time points before, during, or after LTP induction might be different. Different application procedures of mRNA-synthesis blockers will be used in future studies to investigate the latter in more detail. However, our data are consistent with previous reports describing a D1/D5- and NMDA-receptor-dependent LTP in the CA1 of hippocampal slices in vitro that is also dependent on new protein synthesis (Huang and Kandel 1995; Navakkode et al. 2007). Thus, D1/D5-LTP as well as the DA-induced LTP here seem to resemble the late phase of a conventional electrically induced LTP in CA1.

However, these data appear to contradict another study (Mockett et al. 2004), which suggested that dopaminergic function in hippocampal CA1 modulates synaptic responses (Swanson-Park et al. 1999) rather than participating in the machinery required to induce protein synthesis-dependent L-LTP. Although the difference in activation of dopaminergic inputs by a single pulse (Mockett et al. 2004) vs. repeated pulses here could explain the difference, we suggest that differences in slice handling could also result in distinct functional states that might have contributed to the different findings. Thus, the synergistic effect of NMDA- and D1/D5-receptor function could be affected by “preactivated” NMDA-receptor function, which occludes the induction of the D1/D5-LTP. In an earlier study we showed that this indeed seems to be the case (Navakkode et al. 2007). Shorter periods of slice preincubation resulted in different functional outcomes. Huang and Kandel (1995) also only allowed hippocampal slices to rest for 2 h after preparation. This, in addition to the young age of the animals used and the lower temperature of slice incubation, could explain their findings of only a partial, but NMDA-receptor dependence of D1/D5-LTP, i.e., NMDA-receptor function was still ongoing during the relatively short preincubation time (for review, see Sajikumar et al. 2005a).

In search of possible effector mechanisms that are responsible for maintaining a DA-induced L-LTP in hippocampal apical CA1-dendrites, there is now strong evidence that synergistic, associative interactions of dopaminergic with glutamatergic NMDA-receptors are not just required, but determine these processes within a specific functional dendritic compartment (see below). Here, we have identified PKMζ that can be synthesized and regulated via a synergistic, associative interaction and activation of dopaminergic and NMDA receptors, similar to its role as one LTP-specific PRP required for L-LTP in apical CA1-dendrites (Sajikumar et al. 2005b, 2007a). As we had shown previously, D1/D5- together with NMDA-receptor activation stimulates protein kinase A (PKA) via cAMP-formation. PKA is known to be required for L-LTP induction (Frey et al. 1993; Huang and Kandel 1994; Nguyen et al. 1994; Abel et al. 1997). Interestingly, it has been shown that PKA also regulates the synthesis of PKMζ (Kelly et al. 2007), thus supporting our assumption that the D1/D5-NMDA-receptor-induced pathway can result in the persistent PKMζ phosphorylation necessary for maintaining LTP (Ling et al. 2002; Serrano et al. 2005). It remains open as to whether local PKMζ-mRNA is also regulated via such processes, which could explain the compartment-restricted regulation of synaptic events. A specific dendritic area is characterized by distinct innervation patterns of glutamatergic as well as neuromodulatory inputs, and PKMζ is thought to be locally active and regulated (Muslimov et al. 2004; Cracco et al. 2005). Therefore, such processes could be responsible for the determination of a functional dendritic compartment or cluster of synaptic late plasticity (Frey 2001; Govindarajan et al. 2006; Sajikumar et al. 2007a; Frey and Frey 2008). This can be a long-lasting and continuing process, because the persistently active PKMζ can maintain potentiation for hours to days (Serrano et al. 2005; Madronal et al. 2010). Once this process is initiated, the enhanced synaptic efficacy after LTP induction via conventional stimulation or by the synergistic activation of dopaminergic and glutamatergic inputs to apical CA-dendrites could be explained by the increased number of functional surface AMPA receptors at synapses. Artificial disruption of the ongoing PKMζ-induced cycling processes at the membrane by the application of the ZIP could explain the slight depression of the potentials by a shift of the AMPA-receptor cycling to extrasynaptic sites (Fig. 2B,C). This phenomenon, however, may depend on the induction strength of the plasticity event, because it is not always observed (Serrano et al. 2005). Furthermore, if control stimulation (Fig. 2C, filled circles) is suspended for 1 h after DA-application, ZIP application did not result in this depression, demonstrating that this effect of ZIP is specific to potentiated synapses. Taken together, our data strongly suggest that in apical CA1-dendrites the associative activation of dopaminergic and glutamatergic inputs can result in the activation of PKMζ, which, in turn, regulates through interaction with other enzymes the AMPA-receptor cycling process in favor of an increased expression of these receptors at synapses, thus expressing and maintaining LTP.

In summary, our data strengthen the important synergistic, associative role of dopaminergic and glutamatergic receptor function in mediating processes required for the maintenance of hippocampal CA1-LTP as a cellular basis for memory formation. Noninput-specific DA application results only in the activation of PRPs in apical CA1-dendrites if input-specific glutamatergic activation is synergistically provided. Thus, DA-induced delayed-onset potentiation may resemble L-LTP, i.e., it is dependent on glutamatergic stimulation, postsynaptic NMDA-receptor function, and protein synthesis of the LTP-specific PRP PKMζ in apical CA1-dendrites.

Materials and Methods

A total of 115 transversal hippocampal slices (400 µm) were prepared from 115 7-wk-old male Wistar rats, as previously described (Frey et al. 1988; Sajikumar et al. 2005a). Rats were bred in our IfN colony (Magdeburg, Germany); before preparation rats were housed in translucent cages with free access to food and water, and in controlled room conditions (12 h light/dark cycle, temperature, and humidity) in the IfN-owned animal facility. Efforts were made to minimize the number of animals used and their suffering. Ethical approval to conduct the experiments had been obtained from the governmental animal subjects review board prior to the studies according to the German and European requirements for the use of experimental animals.

Slices were incubated within an interface chamber at a temperature of 32oC (a modified Krebs-Ringer solution containing 124 mM NaCl, 4.9 mM KCl, 1.2 mM KH2PO4, 2.0 mM MgSO4, 2.0 mM CaCl2, 24.6 mM NaHCO3, 10 mM D-glucose was used as an artificial corticospinal fluid [ACSF]; carbogen consumption: 32 l/h). In all experiments, two monopolar lacquer-coated, stainless-steel electrodes were positioned within the stratum radiatum of the CA1 region for stimulation of two separate independent synaptic inputs S1 and S2. For recording the field excitatory postsynaptic potential (Field-EPSP) and the population spike, two electrodes were placed in the CA1 dendritic and cell body layer of a single neuronal population, respectively (Fig. 1A). Slices were preincubated for at least 4 h before recording the baseline, a period that is critical for a stable long-term recording (Frey et al. 1988; Sajikumar et al. 2005a).

Following the preincubation period, the test stimulation strength was set to elicit a population spike of 40% of maximal amplitude. The population spike amplitude and the slope of the Field-EPSP were monitored online. Because the time course of the population spike followed the one of the Field-EPSP, only the latter is presented in the analyses. Baseline was recorded for a minimum of 1 h before DA application or LTP induction (four 0.2 Hz biphasic constant current pulses every 15 min, averaged online). In experiments with induction of E-LTP, a single tetanus with 21 biphasic constant current pulses was used (“weak” tetanus = 100 Hz, impulse width duration 0.2 msec per polarity, stimulus intensity for tetanization: population spike threshold). Four 0.2 Hz biphasic, constant-current pulses (0.1 msec per polarity) were used for testing 1, 3, 5, 11, 15, 21, 25, and 30 min post-tetanus, and then every 15 min.

All drug solutions were prepared freshly for every single experiment on the same day if not stated otherwise. DA was used at a concentration of 50 µM. DA was dissolved in ACSF containing the antioxidant, ascorbic acid, at 1 mM concentration. D-2-amino-5-phosphonopentanoic acid (APV; Sigma) was used at a concentration of 50 µM (dissolved in ACSF) to block the NMDA receptor. Anisomycin (Sigma), a reversible protein synthesis-inhibitor, was dissolved in dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO; Sigma) and then diluted with ACSF (Sajikumar et al. 2007b) to the final concentration of 25 µM (a concentration that blocks at least 85% of 3H-leucine incorporation into hippocampal slices [Frey et al. 1991a]; final concentration of DMSO: 0.1%). Rapamycin was used at a concentration of 0.1 µM (Tocris; dissolved in ACSF). The mRNA-synthesis inhibitor actinomycin D was used at a concentration of 25 µM (Tocris). A total of 5 mg of actinomycin D were dissolved in 161 µL of DMSO (99.5%), and 100 µL of that was subsequently dissolved in 100 mL of ACSF to a final concentration of 25 µM actinomycin D (Sajikumar et al. 2007b). This solution was freshly prepared shortly before the appropriate experiment, and the remaining solutions were discarded. This concentration blocks 73% ± 4% of total RNA synthesis in hippocampal slices in vitro, measured as the inhibition of [3H]uridine incorporation into RNA 1 h after drug application (Frey et al. 1996). This result is similar to that obtained from Nguyen et al. (1994) (71%–73%) if the drug is dissolved in DMSO. The selective dopaminergic D1/D5-receptor antagonist SCH23390 was used at a concentration of 0.1 µM (Tocris; dissolved in ACSF). The myristoylated pseudosubstrate peptide, ZIP (myr-SIYRRGARRWRKL-OH; Biosource) was prepared in distilled water as a stock solution (10 mM) and stored at –20°C. The required volume containing the final concentration of 2.5 µM (Serrano et al. 2005) was dissolved in ACSF immediately before the bath application. The scrambled control peptide (scr-ZIP; myr-RLYRKRIWRSAGR-OH; Biosource [2006]) was also used at a concentration of 2.5 µM and prepared in a manner similar to ZIP.

The average values of the population spike (mV) and slope function of the Field-EPSP (mV/ms) per time point were subjected to the Wilcoxon signed rank test when compared within one group or the Mann-Whitney-U-test, when data were compared between groups (significant difference was set at P < 0.05).

Acknowledgments

We thank Diana Koch for her excellent technical support. This work was supported by grants from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft to J.U.F. (FR1034-7 and SFB 779 TP B4—the latter together with Dr. Sabine Frey) and by National Institute of Mental Health grants R01MH53576 and MH57068 to T.C.S.

References

- Abel T, Nguyen PV, Barad M, Deuel TAS, Kandel ER 1997. Genetic demonstration of a role for PKA in the late phase of LTP and in hippocampus-based long-term memory. Cell 88: 615–626 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed T, Frey JU 2003. Expression of the specific type IV phosphodiesterase gene PDE4B3 during different phases of long-term potentiation in single hippocampal slices of rats in vitro. Neuroscience 117: 627–638 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berlowitz L, Pallotta D, Sibley CH 1969. Chromatin and histones: Binding of tritiated actinomycin D to heterochromatin in mealy bugs. Science 164: 1527–1529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bethus I, Tse D, Morris RG 2010. Dopamine and memory: Modulation of the persistence of memory for novel hippocampal NMDA receptor-dependent paired associates. J Neurosci 30: 1610–1618 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cracco JB, Serrano P, Moskowitz SI, Bergold PJ, Sacktor TC 2005. Protein synthesis-dependent LTP in isolated dendrites of CA1 pyramidal cells. Hippocampus 15: 551–556 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey U 1996. Cellular mechanisms of long-term potentiation: Late maintenance. In Neural network models of cognition: Biobehavioral foundations (ed. Donahoe JW, Dorsel VP), pp. 105–128 Elsevier Science Press, Amsterdam, The Netherlands [Google Scholar]

- Frey JU 2001. Long-lasting hippocampal plasticity: Cellular model for memory consilidation? In Cell polarity and subcellular RNA localization (ed. Richter D), pp. 27–40 Springer-Verlag, Berlin-Heidelberg, Germany: [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey S, Frey JU 2008. ‘Synaptic tagging’ and ‘cross-tagging’ and related associative reinforcement processes of functional plasticity as the cellular basis for memory formation. Prog Brain Res 169: 117–143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey U, Morris RGM 1998a. Synaptic tagging: Implications for late maintenance of hippocampal long-term potentiation. Trends Neurosci 21: 181–188 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey U, Morris RGM 1998b. Weak before strong: Dissociating synaptic tagging and plasticity-factor accounts of late-LTP. Neuropharmacology 37: 545–552 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey U, Krug M, Reymann KG, Matthies H 1988. Anisomycin, an inhibitor of protein synthesis, blocks late phases of LTP phenomena in the hippocampal CA1 region in vitro. Brain Res 452: 57–65 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey U, Schroeder H, Matthies H 1990. Dopaminergic antagonists prevent long-term maintenance of posttetanic LTP in the CA1 region of rat hippocampal slices. Brain Res 522: 69–75 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey S, Schweigert C, Krug M, Lossner B 1991a. Long-term potentiation induced changes in protein synthesis of hippocampal subfields of freely moving rats: Time-course. Biomed Biochim Acta 50: 1231–1240 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey U, Matthies H, Reymann KG 1991b. The effect of dopaminergic D1 receptor blockade during tetanization on the expression of long-term potentiation in the rat CA1 region in vitro. Neurosci Lett 129: 111–114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey U, Huang Y-Y, Kandel ER 1993. Effects of cAMP simulate a late stage of LTP in hippocampal CA1 neurons. Science 260: 1661–1664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frey U, Frey S, Schollmeier F, Krug M 1996. Influence of actinomycin D, a RNA synthesis inhibitor, on long-term potentiation in rat hippocampal neurons in vivo and in vitro. J Physiol 490: 703–711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Govindarajan A, Kelleher RJ, Tonegawa S 2006. A clustered plasticity model of long-term memory engrams. Nat Rev Neurosci 7: 575–583 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang YY, Kandel ER 1994. Recruitment of long-lasting and protein kinase A-dependent long-term potentiation in the CA1 region of hippocampus requires repeated tetanization. Learn Mem 1: 74–82 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y-Y, Kandel ER 1995. D1/D5 receptor agonists induce a protein synthesis-dependent late potentiation in the CA1 region of the hippocampus. Proc Natl Acad Sci 92: 2446–2450 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo I, McGaugh JL 2000. Behavioural pharmacology and its contribution to the molecular basis of memory consolidation. Behav Pharmacol 11: 517–534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Izquierdo I, Medina JH 1997. The biochemistry of memory formation and its regulation by hormones and neuromodulators. Psychobiology 25: 1–9 [Google Scholar]

- Jay TM 2003. Dopamine: A potential substrate for synaptic plasticity and memory mechanisms. Prog Neurobiol 69: 375–390 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly MT, Crary JF, Sacktor TC 2007. Regulation of protein kinase Mζ synthesis by multiple kinases in long-term potentiation. J Neurosci 27: 3439–3444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kusuki T, Imahori Y, Ueda S, Inokuchi K 1997. Dopaminergic modulation of LTP induction in the dentate gyrus of intact brain. Neuroreport 8: 2037–2040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemon N, Manahan-Vaughan D 2006. Dopamine D1/D5 receptors gate the acquisition of novel information through hippocampal long-term potentiation and long-term depression. J Neurosci 26: 7723–7729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling DS, Benardo LS, Serrano PA, Blace N, Kelly MT, Crary JF, Sacktor TC 2002. Protein kinase Mζ is necessary and sufficient for LTP maintenance. Nat Neurosci 5: 295–296 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisman JE, Grace AA 2005. The hippocampal-VTA loop: Controlling the entry of information into long-term memory. Neuron 46: 703–713 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lisman JE, Otmakhova NA 2001. Storage, recall, and novelty detection of sequences by the hippocampus: Elaborating on the SOCRATIC model to account for normal and aberrant effects of dopamine. Hippocampus 11: 551–568 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madronal N, Gruart A, Sacktor TC, Delgado-Garcia JM 2010. PKMζ inhibition reverses learning-induced increases in hippocampal synaptic strength and memory during trace eyeblink conditioning. PLos one 5: e10400 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0010400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mockett BG, Brooks WM, Tate WP, Abraham WC 2004. Dopamine D1/D5 receptor activation fails to initiate an activity-independent late-phase LTP in rat hippocampus. Brain Res 1021: 92–100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muslimov IA, Nimmrich V, Hernandez AI, Tcherepanov A, Sacktor TC, Tiedge H 2004. Dendritic transport and localization of protein kinase Mζ mRNA—Implications for molecular memory consolidation. J Biol Chem 279: 52613–52622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Navakkode S, Sajikumar S, Frey JU 2007. Synergistic requirements for the induction of dopaminergic D1/D5-receptor-mediated LTP in hippocampal slices of rat CA1 in vitro. Neuropharmacology 52: 1547–1554 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen PV, Abel T, Kandel ER 1994. Requirement of a critical period of transcription for induction of a late phase of LTP. Science 265: 1104–1107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otani S, Marshall CJ, Tate WP, Goddard GV, Abraham WC 1989. Maintenance of long-term potentiation in rat dentate gyrus requires protein synthesis but not messenger RNA synthesis immediately post-tetanization. Neuroscience 28: 519–526 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otmakhova NA, Lisman JE 1996. D1/D5 dopamine receptor activation increases the magnitude of early long-term potentiation at CA1 hippocampal synapses. J Neurosci 16: 7478–7486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sajikumar S, Frey JU 2004. Late-associativity, synaptic tagging, and the role of dopamine during LTP and LTD. Neurobiol Learn Mem 82: 12–25 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sajikumar S, Navakkode S, Frey JU 2005a. Protein synthesis-dependent long-term functional plasticity: Methods and techniques. Curr Opin Neurobiol 15: 607–613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sajikumar S, Navakkode S, Sacktor TC, Frey JU 2005b. Synaptic tagging and cross-tagging: The role of protein kinase Mzeta in maintaining long-term potentiation but not long-term depression. J Neurosci 25: 5750–5756 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sajikumar S, Navakkode S, Frey JU 2007a. Identification of compartment- and process-specific molecules required for “synaptic tagging” during long-term potentiation and long-term depression in hippocampal CA1. J Neurosci 27: 5068–5080 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sajikumar S, Navakkode S, Korz V, Frey JU 2007b. Cognitive and emotional information processing: Protein synthesis versus gene expression. J Physiol 584.2: 389–400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Serrano P, Yao Y, Sacktor TC 2005. Persistent phosphorylation by protein kinase Mζ maintains late-phase long-term potentiation. J Neurosci 25: 1979–1984 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson-Park JL, Coussens CM, Mason-Parker SE, Raymond CR, Hargreaves EL, Dragunow M, Cohen AS, Abraham WC 1999. A double dissociation within the hippocampus of dopamine D1/D5 receptor and β-adrenergic receptor contributions to the persistence of long-term potentiation. Neuroscience 92: 485–497 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wise RA 2004. Dopamine, learning and motivation. Nat Rev Neurosci 5: 483–494 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao Y, Kelly MT, Sajikumar S, Serrano P, Tian D, Bergold PJ, Frey JU, Sacktor TC 2008. PKMζ maintains late long-term potentiation by N-ethylmaleimide-sensitive factor/GluR2-dependent trafficking of postsynaptic AMPA receptors. J Neurosci 28: 7820–7827 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]