Abstract

Protein ubiquitination has been implicated in the regulation of axonal growth and synaptic plasticity as well as in the pathogenesis of neurodegenerative diseases. Here we show that depolarization-dependent Ca2+ influx into synaptosomes produces a global, rapid (range of seconds), and reversible decrease of the ubiquitinated state of proteins, which correlates with the Ca2+-dependent dephosphorylation of several synaptic proteins. A similar general decrease in protein ubiquitination was observed in nonneuronal cells on Ca2+ entry induced by ionomycin. Both in synaptosomes and in nonneuronal cells, this decrease was blocked by FK506 (a calcineurin antagonist). Proteins whose ubiquitinated state was decreased include epsin 1, a substrate for the deubiquitinating enzyme fat facets/FAM, which we show here to be concentrated at synapses. These results reveal a fast regulated turnover of protein ubiquitination. In nerve terminals, protein ubiquitination may play a role both in the regulation of synaptic function, including vesicle traffic, and in the coordination of protein turnover with synaptic use.

Covalent conjugation of ubiquitin to proteins represents an important mechanism to regulate their turnover, subcellular distribution, or function. A well established role of protein polyubiquitination is to target cytosolic proteins for degradation in proteasomes (1–3). Conversely, mono- or oligoubiquitination of membrane proteins targets them to multivesicular bodies and eventually to degradation in lyososomes (4). In addition, reversible mono- and oligoubiquitination of proteins are important regulatory mechanisms in a variety of cellular processes (5, 6).

Several synaptic proteins undergo ubiquitination (7–11), and this modification has been implicated in the regulation of both pre- and postsynaptic plasticity (11–14). Furthermore, axon guidance defects or aberrant synaptic morphology and function have been associated with abnormal protein ubiquitination or proteasomal degradation (15–19). Malfunction of protein ubiquitination has been implicated in Parkinson's disease (20), and neuronal cytoplasmic inclusions characteristic of neurodegenerative diseases contain ubiquitinated proteins (9, 21, 22), underscoring the importance of normal ubiquitination metabolism in the nervous system.

Despite evidence for the occurrence of protein ubiquitination in the presynapse, little is known about its regulation. The great distance of nerve terminals from the cell body poses a special problem for the control of protein turnover. The arrival of new material via axonal transport must continuously be balanced by either active retrograde axonal flow or local degradation. Membranous organelles and a variety of membrane-associated proteins are transported bidirectionally by “fast” axonal transport (23). However, pools of cytosolic proteins, which travel by the so-called “slow” axonal transport, move only anterogradally (24). The speed of slow transport is in the range of, at most, a few millimeters per day (24), so that proteins traveling by this mechanism may take weeks or even months to reach axon endings. Clearly, the degradation of these proteins must be blocked “en route” but then permitted in nerve terminals. Thus, proteolysis, including ubiquitin-dependent proteolyisis, must be finely regulated in axon endings.

If protein ubiquitination plays an important role in presynaptic function, this process is likely to be regulated by synaptic stimulation. Here, we have investigated whether depolarization-dependent Ca2+ entry affect the ubiquitinated state of synaptic proteins.

Methods

Antibodies, cDNAs, and Drugs. Antibodies directed against epsin 1, Eps15, amphiphysin 1, synapsin 1, and synaptophysin were generated in our labs and previously described (25, 26). Rabbit antibodies directed against amino acids 1476–1918 of mouse FAM were a kind gift of Kozo Kaibuchi (Nagoya University, Nagoya, Japan). Mouse monoclonal antiubiquitin antibodies were from Covance (Richmond, CA) and from Affinity, Nottingham, U.K. (FK2). Mouse monoclonal antibodies against the hemagglutinin (HA) epitope and β-tubulin were from Roche Applied Science (Indianapolis) and Sigma, respectively. Polyclonal antibodies directed against phosphosynapsin (phosphorylation site 3) were a gift from Andy Czernik, Angus Nairn, and Paul Greengard (The Rockefeller University, New York). Ionomycin, FK506, cyclosporin A and YU101 were purchased from Calbiochem. FAM cDNA was a kind gift from Stephen Wood (University of Adelaide, Adelaide, Australia).

Cell Culture. Cells were transfected with epsin 1 and HA–ubiquitin cDNAs in a pcDNA vector by using Lipofectamine (Invitrogen). Ionomycin (Calbiochem) was used at the concentration of either 1 μM in serum-free DMEM supplemented with 1 mM CaCl2 (final Ca2+ = 2.3 mM) (DMEM*) or of 6 μM in DMEM* containing bovine serum (10%). Cells were lysed either in 50 mM Tris, pH 7.5/150 mM NaCl/1 mM MgCl2/5mM EGTA/10 mM Na3VO4/5 mM N-ethylmaleimide/protease inhibitor mixture (for liposome sedimentation experiments) or in the same buffer plus Triton X-100 (for the GST pulldowns of Fig. 5B) or in buffered 1% SDS also containing 1 mM Na3VO4 and immediately boiled for 10 min. The latter material was then used for SDS/PAGE and Western blotting or further processed for immunoprecipitation or GST pulldowns (Fig. 5C). To this aim, SDS solubilized extracts were diluted with 9 volumes of 20 mM Hepes, pH 7.4/50 mM NaCl/50 mM Na3PO4/50 mM NaF/5 mM EDTA/5 mM EGTA/5 mM N-ethylmaleimide/1.1% Triton X-100 to scavenge SDS with excess Triton X-100. The resulting material was clarified by centrifugation at 14,000 rpm (20,000 × g) for 10 min at 4°C, and the supernatants were used for immunoprecipitations or GST pulldowns.

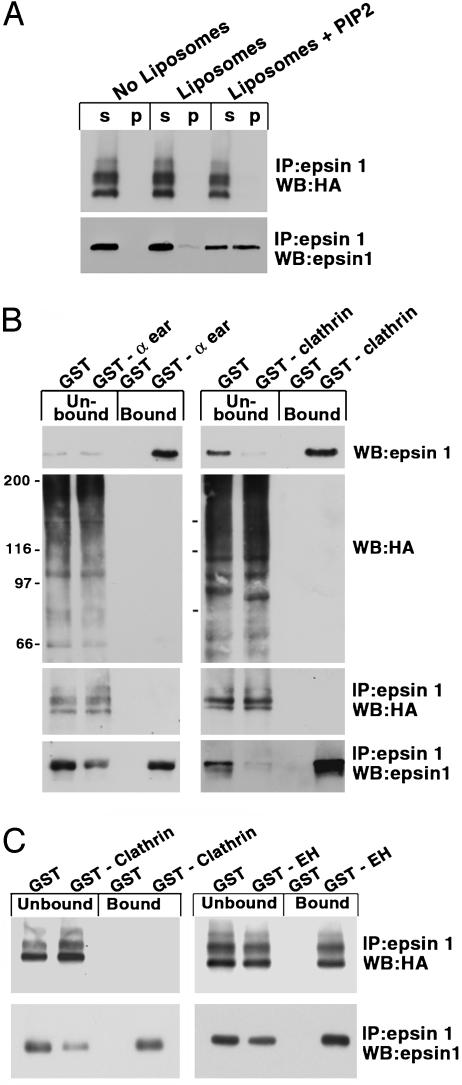

Fig. 5.

Ubiquitination of epsin 1 in cells overexpressing HA-ubiquitin inhibits its interaction with liposomes, clathrin, and AP-2, but not Eps15. CHO cells were cotransfected with HA-ubiquitin and epsin 1. (A) A cytosolic fraction (prepared by centrifugation of cell extracts not containing Triton X-100) was incubated with liposomes for 30 min at 37°C, and liposome-bound material was recovered by sedimentation. Supernatants (s) and pellets (p) were then subjected to immunoprecipitation and Western blotting to reveal HA-ubiquitin and epsin 1. (B and C) Triton X-100 solubilized cell extracts (B) or cell extracts obtained by SDS solubilization followed by Triton treatment (C) were affinity-purified on glutathione-immobilized GST or GST fusions of the ear domain of AP-2 of the NH2-terminal region of clathrin heavy chain and of the Eps15 homology domain region of Eps15. The presence of HA-ubiquitin and epsin 1 in the unbound and bound material was then revealed by Western blotting either without further processing or after anti-epsin 1 immunoprecipitation, as indicated.

Small Interfering RNA (siRNA)-Mediated Suppression of FAM. Two pairs of oligonucleotides comprising mouse FAM sequences 182–200 (AAGATGAGGAACCTGCATTTC) and 3432–3452 (AAGGGGTGCCTACCTCAATGC) (which are 100% conserved in human FAM) were generated (W.M. Keck Facility, Yale University, New Haven, CT). The oligonucleotides were deprotected by using tetrabutylammonium fluoride (Sigma) followed by desalting and annealing as described. HeLa cells were transfected with 50 nM each of the two oligonucleotide pairs or 50 nM of one pair of vimentin-specific oligonucleotides (a kind gift of Daiming Li, Yale University) by using Oligofectamine (Invitrogen) according to manufacturer's instructions and incubated for 3 days. Cells were then transfected with epsin 1 cDNA (25) in a pcDNA vector by using Lipofectamine and processed for immmunoprecipitations and Western blotting.

Synaptosome Experiments and Miscellaneous Procedures. Synaptosome preparation and stimulation were performed as described (26). In all cases, synaptosomes were used after a 10-min preincubation at 37°C to restore the metabolic state of living nerve terminals. Liposome sedimentation experiments were carried out as described (27). SDS/PAGE, Western blotting, immunoprecipitation, GST pulldowns, cell transfection, and immunofluorescence were performed according to standard procedures.

Results

To investigate protein ubiquitination in axon endings, we have used synaptosomes (pinched-off nerve terminals with attached fragments of postsynaptic elements), a model system commonly used for the study of neurosecretion and its regulation. Like intact synapses, synaptosomes can be stimulated by depolarization in high K+ in the presence of Ca2+. This treatment also results in an increased state of phosphorylation of a variety of nerve terminal proteins, including synapsin 1 (28–30), and in the dephosphorylation of other proteins (26, 29, 31–34).

Antiubiquitin Western blotting of control synaptosomes revealed primarily the “smeary” pattern typical of polyubiquitinated proteins (Fig. 1A). Stimulation by depolarization in 50 mM K+ for 30 sec, i.e., a condition that results in massive evoked exocytic release of neurotransmitter (35, 36), induced a strong decrease in the overall levels of ubiquitinated proteins. This change required extracellular Ca2+ and correlated with the stimulation-dependent downward mobility shift of amphiphysin 1 (Fig. 1 A), a clathrin accessory factor concentrated in nerve terminals. Like several other endocytic proteins, amphiphysin 1 is phosphorylated in resting nerve terminals and undergoes dephosphorylation on stimulation, with resulting increased mobility (26, 37).

Fig. 1.

Depolarization- and Ca2+-dependent change in protein ubiquitination at synapses. Rat-brain synaptosomes were preincubated for 10 min at 37°C in control physiological buffer, then further incubated at 37°C for 30 sec (except for B and D) under the conditions indicated. High K+ = 50 mM K+ with a corresponding decrease in Na+. For the zero Ca2+ condition of field A, CaCl2 was omitted and EGTA (1.2 mM final) was added. Incubations were stopped by SDS, and synaptosomal proteins were separated by SDS/PAGE and reacted by immunoblotting with antibodies to ubiquitin, amphiphysin, phosphosynapsin (antiphospho-site 3) (60), and, as a control for gel loading, synaptophysin, and tubulin. In D, the 30-sec depolarization was followed by an additional 10 min in control buffer and finally by a second 30-sec depolarization. Molecular weight standards are indicated in A and simply as dashes in B–E. Sphysin, synaptophysin; p-syn, phosphosynapsin.

The effect of stimulation on the state of protein ubiquitination (and on amphiphysin 1 dephosphorylation) was already nearly maximal at 15 sec (Fig. 1B), the earliest time point tested. At 15 sec, an increase in the phosphorylation state of synapsin 1 (30), as demonstrated by Western blotting with an antiphosphosynapsin antibody (RU19) (Fig. 1B), was also observed, confirming the viability of synaptosomes and ATP availability under our experimental conditions. As in the case of the dephosphorylation of amphiphysin (26, 37) and other endocytic proteins (38), the decrease in protein ubiquitination was blocked by 0.5 μM FK506 (Fig. 1C) or by 0.5 μM cyclosporin A (not shown), two antagonists of the Ca2+-dependent phosphatase calcineurin (31, 39), and was reversed by the incubation of synaptosomes in control buffer for an additional 10 min (Fig. 1D). A further 30-sec incubation in high K+, after the 10-min rest, triggered a new cycle of amphiphysin dephosphorylation and loss of protein ubiquitination (Fig. 1D). Loss of ubiquitination could in principle be explained, at least in part, by proteosomal degradation of polyubiquitinated proteins. However, a 30-min pretreatment of synaptosomes with the proteosomal inhibitor YU101 (20 μM) did not inhibit the loss of ubiquitin immunoreactivity induced by high K+ (Fig. 1E). Thus, these changes must reflect either generalized deubiquitination or, most likely (see Discussion), impaired ubiquitination in the context of a very rapid ubiquitination–deubiquitination cycle.

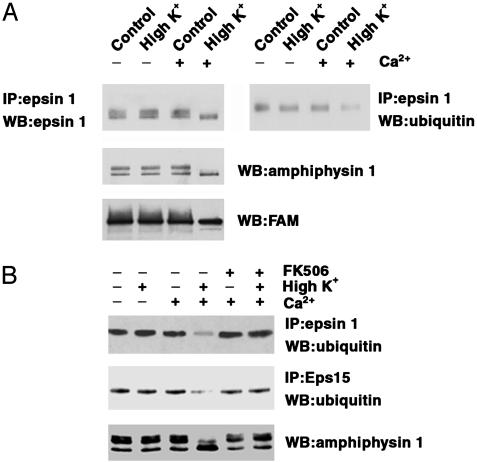

The decrease in antiubiquitin immunoreactivity observed in stimulated synaptosomes affected both the “smear,” thought to reflect polyubiquitination ladders, and the discrete bands. Because these bands may include monoubiquitinated proteins, we examined the ubiquitinated state of epsin 1 (25), a well characterized target of monoubiquitination (6, 40). Epsin 1, which also binds ubiquitin via ubiquitin-interacting motif (UIM) domains (40), functions as an adaptor in clathrin coat assembly and may have additional roles in growth factor receptor signaling, actin regulation, and control of transcription (41–43). Like amphiphysin, epsin 1 undergoes Ca2+-dependent dephosphorylation in rat-brain synaptosomes (33), and this change is reflected in a downward mobility shift in SDS/PAGE (33). Antiubiquitin immunoblotting of antiepsin 1 immunoprecipitates revealed a pool of ubiquitinated epsin 1 in control synaptosomes and a Ca2+-dependent decrease of this pool in the stimulated samples (Fig. 2). Ubiquitinated epsin 1 migrated slightly slower than the bulk of epsin 1, did not undergo the lower mobility shift with stimulation, and was below detection in the antiepsin 1 immunoblot. Thus, ubiquitination is likely to involve only a very small fraction of total epsin 1. A major binding partner of epsin, Eps15 (25, 40), also undergoes monoubiquitination. As revealed by Western blotting of anti-Eps15 immunoprecipitates, a decrease in the state of ubiquitination occurred for this protein as well in stimulated synaptosomes (Fig. 2B). FK506 not only blocked the dephosphorylation of amphiphysin 1 (ref. 26 and Fig. 2B), epsin 1 (33), and Eps15 (33), but also inhibited the decrease of ubiquitinated epsin 1 and Eps15 (Fig. 2B).

Fig. 2.

Depolarization- and Ca2+-dependent decrease in the ubiquitinated state of epsin 1 and Eps15 at synapses. Rat-brain synaptosomes were preincubated for 10 min at 37°C in control buffer, then further incubated for 30 sec at the same temperature in either control or high K+ buffer and in the presence or absence of Ca2+ and of FK506 (0.5 μM) and finally solubilized in SDS. This material was directly processed for SDS/PAGE and Western blotting (WB) for amphiphysin 1 and FAM, or reacted with excess Triton X-100 (to remove free SDS) and subjected to antiepsin 1 and anti-Eps15 immunoprecipitation (IP). Immunoprecipitates were then analyzed by SDS/PAGE and immunoblotting for epsin 1, Eps15, and ubiquitin. The two blots at A Top are from the same gel and are precisely aligned to show slight differences in migration between the bulk of epsin 1 immunoreactivity (Left) and ubiquitinated epsin 1 (Right).

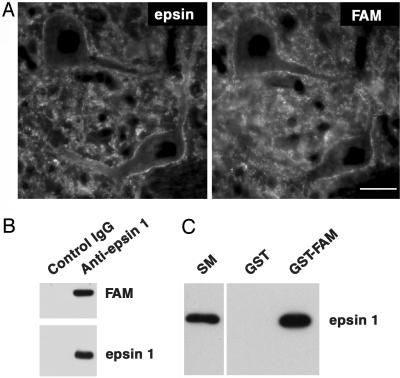

In Drosophila, epsin binds to, and is a physiological substrate for, the deubiquitinating enzyme fat facets and is a critical mediator of the function of this enzyme in development (44, 45). Overexpression of fat facets in neurons affects synaptic morphology (18). Whether fat facets is normally present at synapses is not known. We have now found (i) that antibodies directed against epsin 1 and FAM, the mammalian homologue of fat facets (46), produce an overlapping immunostaining of synapses in frozen sections of rat brain (Fig. 3A); (ii) that FAM coprecipitates with anti-epsin 1 immunoprecipitates (Fig. 3B); and (iii) that epsin 1 is specifically retained by an immobilized fusion protein of the catalytic domain of FAM (Fig. 3C). Western blotting of purified synaptosomes with anti-FAM antibodies revealed a prominent broad band that became sharper after stimulation, possibly reflecting Ca2+-dependent changes (Fig. 2 A) such as dephosphorylation. Accordingly, preliminary evidence suggests that the interaction between epsin 1 and FAM may be negatively regulated by phosphorylation (not shown).

Fig. 3.

Colocalization and interaction of epsin 1 with FAM in brain. (A) Double immunofluorescence of rat-brain frozen sections. (Bar = 30 μm.) (B) Control or anti-epsin 1 immunoprecipitates generated from rat-brain cytosol were immunoblotted for either FAM or epsin 1, thus revealing coprecipitation of the two proteins. (C) Anti-epsin 1 immunoblot of material affinity-purified from brain (SM, starting material) by GST or a GST fusion protein of the catalytic domain of mouse FAM (amino acids 1554–1953).

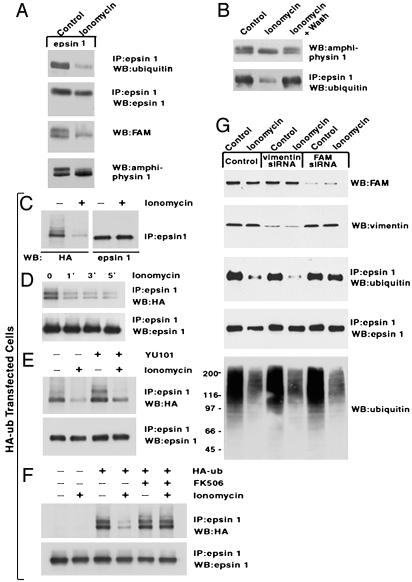

We further investigated the role of FAM in the deubiquitination of epsin 1 by using nonneuronal cells [Chinese hamster ovary (CHO) and HeLa cells], where FAM expression could be suppressed by siRNA. We first characterized the ubiquitination of epsin 1 in these cells. Cells were transfected with epsin 1 and in some case also with HA-tagged ubiquitin, thus allowing the analysis of the ubiquitinated state of epsin 1 by using anti-HA antibodies, a very sensitive detection method. Although only one ubiquitinated epsin 1 band was observed after transfection of epsin 1 alone (Fig. 4 A and B), multiple ubiquitinated epsin 1 species were observed in HA-ubiquitin transfected cells (Fig. 4 C–F), possibly reflecting multimonoubiquitination (47) due to ubiquitin overexpression. The ubiquitinated pool of epsin was detected only by antibodies that recognize ubiquitin (anti-HA antibodies) and not by antiepsin antibodies (Fig. 4C). Thus, as observed at synapses, ubiquitination involves only a very small pool of the protein, although a contribution to this result of epitope masking by multiple ubiquitination cannot be excluded.

Fig. 4.

Ca2+-dependent deubiquitination of epsin in nonneuronal cells and role of FAM in this reaction. Cells were subjected to various treatments, then homogenized and either subjected to immunoprecipitation (IP) followed by SDS/PAGE and Western blotting (WB) (in the case of epsin 1) or directly processed by SDS/PAGE and Western blotting (in the case of other proteins). (A and B) CHO cells were cotransfected with amphiphysin 1 and epsin 1. Transfected cells were incubated in DMEM* (total Ca2+ = 2.3 mM, see Methods) and 10% FBS in the absence or presence of ionomycin (6 μM) for 15 min (A) or 5 min (B). In the case of B, a sample of ionomycin-treated cells was then returned to ionomycin-free medium for 10 min (right lane). (C) CHO cells cotransfected with HA-ubiquitin and epsin 1 were incubated for 5 min in DMEM* in the presence or absence of ionomycin (1 μM). Bands that most likely reflect mono-, di-, and triubiquitinated epsin (Left) migrate slightly above the bulk of epsin immunoreactivity (Right). (D) CHO cells cotransfected with HA-ubiquitin and epsin 1 were incubated for the time indicated in DMEM*. (E) CHO cells cotransfected with HA-ubiquitin and epsin 1 were incubated for 3 h in DMEM* plus the proteasome inhibitor YU101 and then incubated for an additional 5 min in DMEM* in the absence or presence of ionomycin (1 μM). Although the level of ubiquitinated epsin 1 is increased by inhibition of the proteasome, the effect of ionomycin is not inhibited. (F) CHO cells transfected with epsin 1 or cotransfected with both epsin 1 and HA-ubiquitin were incubated for 5 min with and without ionomycin (1 μM) and with or without FK506 (0.5 μM), as indicated. (G) HeLa cells were incubated for 3 days in control conditions with two pairs of FAM-specific siRNAs or one pair of vimentin-specific siRNAs as an additional control. They were then transfected with epsin 1 in the continued presence of the siRNAs. Twenty-four hours after transfection, cells were exposed to ionomycin stimulation as in C, then analyzed by immunoprecipitation and Western blotting.

Ca2+ influx into nonneuronal cells was induced by the Ca2+ ionophore ionomycin in the presence of 2.3 mM extracellular Ca2+. As a control for the occurrence of Ca2+-stimulated reactions, the electrophoretic mobility of cotransfected amphiphysin 1 was monitored, because even in nonneuronal cells, this protein undergoes dephosphorylation in response to Ca2+ influx (S. Floyd and P.D.C., unpublished observations and Fig. 4A). FAM, which in well resolved gels migrated as a doublet, collapsed into a single lower band in ionomycin-treated CHO cells (Fig. 4A), possibly reflecting Ca2+-dependent dephosphorylation. Ionomycin also produced a decrease in the global ubiquitinated state of proteins in both CHO and HeLa cells (not shown and Fig. 4G) as well as a decrease of either endogenous (Fig. 4 A and B) or HA-tagged ubiquitin (Fig. 4C) associated with wild-type epsin 1, as detected by Western blots of antiepsin 1 immunoprecipitates (Fig. 4 A and C). These changes could already be observed 1 min after the addition of 1 μM ionomycin (Fig. 4D) and were reversed by removal of ionomycin and further incubation with control medium for 10 min (Fig. 4B). The ionomycin-induced effect in HA-ubiquitin transfected cells was not inhibited by pretreatment of cells for3hwiththe proteasome inhibitor YU101 (Fig. 4E) but was blocked by FK506 (Fig. 4F), consistent with a change in the ubiquitinated state, rather than with an effect of protein degradation. As in the case of synaptosomes, inhibition of an upstream step in the ubiquitination cascade appears as the more likely explanation for ionomycin effect.

siRNA experiments were performed in HeLa cells. A 3-d incubation with siRNAs specific for FAM or for the control protein vimentin strongly inhibited endogenous FAM or vimentin expression, respectively (Fig. 4G). In both sets of cells, the general decrease of protein ubiquitination induced by ionomycin-mediated Ca2+ influx was still observed, but in the FAM–siRNA-treated samples, the loss of ubiquitin from epsin 1 was selectively inhibited (Fig. 4G). These findings demonstrate a role of FAM in epsin 1 deubiquitination, in agreement with studies of the Drosophila homologues of these two proteins (45), but not in the global decrease in the ubiquitination state of proteins. This global decrease is likely to include a large variety of deubiquitinating enzymes with different substrate specificities.

Epsin acts as a multifunctional adaptor in endocytic traffic via its interaction with phosphatidylinositol 4,5-bisphosphate [PI(4,5)P2], clathrin, the clathrin adaptor AP-2, Eps15, and possibly ubiquitinated membrane proteins (42, 43). It was of interest to determine whether the ubiquitination of epsin affects its binding properties. Due to the lability of ubiquitination in tissue and cell extracts, we could not reliably analyze the interaction of epsin from brain tissue or untransfected cells. We used extracts of cells cotransfected with HA-ubiquitin and epsin 1, where a greater pool of epsin is in the ubiquitinated form and where the HA epitope facilitates ubiquitin detection. To test the interaction with lipids, a cell lysate was incubated with synthetic liposomes comprising 70% phosphatidylcholine, 20% phosphatidylserine (PS), and either 10% PI(4,5)P2 or an additional 10% PS. Liposome-bound epsin 1 was recovered by centrifugation, followed by solubilization of the pellet in SDS, addition of Triton X-100 to titrate out SDS, antiepsin immunoprecipitation, and finally Western blotting for either epsin 1 or ubiquitin. Epsin 1 was efficiently recovered on PI(4,5)P2-containing liposomes, with a corresponding decrease in the supernatant. However, ubiquitinated epsin was not enriched on liposomes, irrespective of the presence of PI(4,5)P2 (Fig. 5A). Likewise, pulldown assays with GST fusion proteins of the ear domain of the clathrin adaptor AP-2 and of the NH2-terminal domain of clathrin, i.e., the epsin interacting regions of these two coat proteins (48, 49), revealed a very prominent affinity purification of epsin 1 (with a partial depletion from the unbound material) but not of HA-ubiquitin-tagged epsin 1 (Fig. 5 B and C) or other HA-tagged proteins (Fig. 5B). In contrast, a GST fusion protein of the Eps15 homology domain-containing region of Eps15 pulled down ubiquitinated epsin 1 (Fig. 5C).

The ubiquitinated state of epsin 1 produced by overexpression of HA-ubiquitin may not reflect its normal ubiquitinated state. Thus, it remains to be determined whether loss of the interactions with liposomes, clathrin, and AP-2 revealed by these experiments are physiologically relevant. Furthermore, ubiquitinated epsin 1 may also be phosphorylated, and phosphorylation may contribute to the loss of some interactions. However, the nearly complete lack of HA-ubiquitin immunoreactivity on the material bound to clathrin and AP-2 contrasts with the much less pronounced inhibition of binding observed for phosphorylated epsin 1 (33). An interesting possibility is that the ubiquitin covalently bound to epsin 1 may interact with epsin's ubiquitin-interacting motif domain, thus forming an intramolecular interaction that occludes the binding sites for PI(4,5)P2, clathrin, and AP-2 but not the binding sites for Eps15 homology domains, which are localized in the COOH-terminal region of the protein.

Discussion

We report here that depolarization-dependent Ca2+ influx induces a very rapid and general decrease of the ubiquitinated state of synaptic proteins, including monoubiquitinated proteins. The fast kinetics of this change and its insensitivity to a proteasome inhibitor suggest deubiquitination rather than proteosomal degradation. Results from nonneuronal cells, where similar effects were produced by ionomycin-induced Ca2+ entry, demonstrate that disruption of a single deubiquitinating enzyme, FAM (46), blocks the deubiquitination of epsin 1 but not global deubiquitination.

In principle, Ca2+ could produce a general stimulation of deubiquitinating enzymes. However, given the multiplicity of deubiquitinating enzymes, a general stimulation of deubiquitination reactions seems unlikely. Deubiquitinating enzymes are known to be very active. Thus, an alternative possibility is that rapid deubiquitination (including deubiquitination mediated by FAM) occurs constitutively and that Ca2+ inhibits some upstream step(s) in the chain of reactions leading to protein ubiquitination. In fact, rapid loss of protein-associated ubiquitin was observed under conditions that deplete synaptosomal ATP (incubation with the mitochondrial uncoupler FCCP and deoxyglucose (50, 51)] (unpublished observations), in agreement with the ATP dependence of protein ubiquitination. The high K+ stimulation protocol used, however, did not produce a drop of ATP levels (52) (unpublished observations), and the stimulation-dependent deubiquitination occurred concomitantly to the phosphorylation of synapsin 1. Furthermore, the conditions shown here to induce global deubiquitination are the same as those known to stimulate exocytic release of neurotransmitter, an ATP-dependent reaction (35, 36). Thus, if the effects observed are, at least in part, due to inhibition of ubiquitination, they are likely to result from the Ca2+-dependent inhibition of specific biochemical reactions. Irrespective of the mechanisms responsible for the observed changes, our results demonstrate a remarkably rapid turnover of ubiquitin in synaptosomes.

The stimulated decrease in protein ubiquitination occurs in parallel to the dephosphorylation of a variety of synaptic proteins, primarily endocytic proteins including dynamin, amphiphysin, epsin 1, and Eps15 (26, 31–33). Both processes are blocked by FK506 and cyclosporin A, two inhibitors of the Ca2+-dependent phosphatase calcineurin (39), suggesting an involvement of this enzyme. Calcineurin was shown to have proapoptotic effects (53, 54), yet the events described here are too fast to be accounted for by this action and are rapidly reversible. One must also consider the possibility that not all of the effects of FK506 and cyclosporin A are mediated by calcineurin antagonism via their interactions with FKBP12 and cyclophillin, respectively (39, 55). However, rapamycin that forms a complex with FKBP12 that does not inhibit calcineurin (39) did not inhibit Ca2+-dependent deubiquitination (not shown).

The precise physiological significance of the “global” regulation of ubiquitination revealed by our study remains to be determined. As discussed in the Introduction, protein-mediated degradation must be finely tuned in axon terminals. A Ca2+-dependent decrease in the steady-state level of protein ubiquitination may provide a feedback mechanism between synaptic activity and the rate of protein degradation, thus leading to the stabilization of active nerve terminals. Proteasome inhibitors were shown to enhance neurite outgrowth and synaptic strength (13, 56, 57). It will be of interest to determine the interplay of Ca2+-regulated ubiquitin-dependent proteasomal degradation with the Ca2+/calpain-dependent breakdown (58) of a variety of synaptic proteins.

The strong decrease of the ubiquitinated state of synaptic proteins after depolarization-dependent Ca2+ entry contrasts with the enhanced rate of protein ubiquitination and degradation observed by Ehlers (11) in neuronal cultures chronically stimulated by the block of inhibitory neurotransmission. One difference between the two studies is that Ehlers focused selectively on postsynaptic proteins, whereas our synaptosomes studies are likely to favor the detection of changes in the presynaptic compartment. A more important difference between the two studies, however, is represented by the two modes of stimulation, acute in our case and chronic in the case of Ehlers. There are other examples of opposite actions produced by an acute Ca2+ influx vs. prolonged and modulatory stimuli. For instance, phosphorylation of Eps15 and epsin is enhanced by growth factor receptor signals (59) (unpublished results), whereas an acute rise of cytosolic Ca2+ induces dephosphorylation of both proteins (33). Moreover, both Eps15 and epsin 1 undergo an increase in their ubiquitinated state in response to growth factors (40), in contrast to the rapid Ca2+-dependent deubiquitination reported here.

Nerve terminal stimulation activates the synaptic vesicle cycle and therefore endocytosis. Because mono- and oligoubiquination were shown to regulate components of the endocytic pathway (5, 6), changes in the steady-state level of protein ubiquitination may also be linked to changes in membrane traffic. In the case of epsin 1, evidence obtained from cells overexpressing ubiquitin and epsin 1 (but it remains to be seen whether this observation also applies to epsin ubiquitinated under more physiological conditions) suggests that ubiquitination impairs its clathrin adaptor functions. Thus, a stimulation-dependent deubiquitination of epsin 1 would be consistent with an enhanced rate of endocytosis. However, only an extremely small pool of epsin appears to be involved in ubiquitination–deubiquitination reactions at any given time in synaptosomes, speaking against the possibility that ubiquitination may have a major role in keeping epsin 1 in a nonassembled state in resting nerve terminals. Furthermore, ubiquitination is thought to correlate with activation of the endocytic pathway (4–6) rather than with its resting state. Ubiquitinated epsin may represent a very transient intermediate, possibly involved in generating a specific conformation of this protein, via intramolecular interactions between ubiquitin and the ubiquitin-interacting motif domain.

In conclusion, synaptic stimulation has dramatic effects on protein ubiquitination. Genetic evidence demonstrates that abnormal protein ubiquitination may play a role in diseases of the nervous system (9, 19, 21, 22). The further elucidation of mechanisms in protein ubiquitination at the synapse is expected to provide new information of significant interest in synaptic physiology, general cell biology, and medicine.

Acknowledgments

We thank Huaqing Cai for help in some of the initial siRNA experiments; Scott Floyd for discussing preliminary results; and Hemmo Meyer, Graham Warren, and Mark Hochstrasser for discussion. This work was supported in part by a Human Frontiers Science Program grant (to P.D.C. and P.P.D.F.), and by grants from the National Institutes of Health (to P.D.C.), and from Associazione Italiana Ricerca sul Cancro, the Telethon Foundation, and the European Community (to P.P.D.F.).

Abbreviations: HA, hemagglutinin; DMEM*, serum-free DMEM supplemented with 1 mM CaCl2; siRNA, small interfering RNA; CHO, Chinese hamster ovary.

References

- 1.Hochstrasser, M. (1996) Annu. Rev. Genet. 30, 405–439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hershko, A. & Ciechanover, A. (1998) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 67, 425–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pickart, C. M. (2001) Annu. Rev. Biochem. 70, 503–533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katzmann, D. J., Odorizzi, G. & Emr, S. D. (2002) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3, 893–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hicke, L. (2001) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2, 195–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aguilar, R. C. & Wendland, B. (2003) Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 15, 184–190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wheeler, T. C., Chin, L. S., Li, Y., Roudabush, F. L. & Li, L. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 10273–10282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chin, L. S., Vavalle, J. P. & Li, L. (2002) J. Biol. Chem. 277, 35071–35079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Shimura, H., Schlossmacher, M. G., Hattori, N., Frosch, M. P., Trockenbacher, A., Schneider, R., Mizuno, Y., Kosik, K. S. & Selkoe, D. J. (2001) Science 293, 263–269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Burbea, M., Dreier, L., Dittman, J. S., Grunwald, M. E. & Kaplan, J. M. (2002) Neuron 35, 107–120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ehlers, M. D. (2003) Nat. Neurosci. 6, 231–242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hegde, A. N., Inokuchi, K., Pei, W., Casadio, A., Ghirardi, M., Chain, D. G., Martin, K. C., Kandel, E. R. & Schwartz, J. H. (1997) Cell 89, 115–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhao, Y., Hegde, A. N. & Martin, K. C. (2003) Curr. Biol. 13, 887–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Speese, S. D., Trotta, N., Rodesch, C. K., Aravamudan, B. & Broadie, K. (2003) Curr. Biol. 13, 899–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Campbell, D. S. & Holt, C. E. (2001) Neuron 32, 1013–1026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Myat, A., Henry, P., McCabe, V., Flintoft, L., Rotin, D. & Tear, G. (2002) Neuron 35, 447–459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Watts, R. J., Hoopfer, E. D. & Luo, L. (2003) Neuron 38, 871–885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.DiAntonio, A., Haghighi, A. P., Portman, S. L., Lee, J. D., Amaranto, A. M. & Goodman, C. S. (2001) Nature 412, 449–452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wilson, S. M., Bhattacharyya, B., Rachel, R. A., Coppola, V., Tessarollo, L., Householder, D. B., Fletcher, C. F., Miller, R. J., Copeland, N. G. & Jenkins, N. A. (2002) Nat. Genet. 32, 420–425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giasson, B. I. & Lee, V. M. (2003) Cell 114, 1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shimura, H., Hattori, N., Kubo, S., Mizuno, Y., Asakawa, S., Minoshima, S., Shimizu, N., Iwai, K., Chiba, T., Tanaka, K. & Suzuki, T. (2000) Nat. Genet. 25, 302–305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Taylor, J. P., Hardy, J. & Fischbeck, K. H. (2002) Science 296, 1991–1995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hirokawa, N. (1997) Curr. Opin. Neurobiol. 7, 605–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lasek, R. T. & Hoffman, P. N. (1976) in Cell Motility, eds. Goldman, R., Pollard, T. D. & Rosenbaum, J. (Cold Spring Harbor Lab. Press, Plainview, NY), Vol. 3, pp. 1021–1049. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen, H., Fre, S., Slepnev, V. I., Capua, M. R., Takei, K., Butler, M. H., Di Fiore, P. P. & De Camilli, P. (1998) Nature 394, 793–797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bauerfeind, R., Takei, K. & De Camilli, P. (1997) J. Biol. Chem. 272, 30984–30992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wenk, M. & De Camilli, P. (2003) Methods Enzymol. 372, 248–260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schulman, H. & Greengard, P. (1978) Nature 271, 478–479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wang, J. K., Walaas, S. I. & Greengard, P. (1988) J. Neurosci. 8, 281–288. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.De Camilli, P., Benfenati, F., Valtorta, F. & Greengard, P. (1990) Annu. Rev. Cell Biol. 6, 433–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Liu, J. P., Sim, A. T. & Robinson, P. J. (1994) Science 265, 970–973. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Slepnev, V. I., Ochoa, G. C., Butler, M. H., Grabs, D. & Camilli, P. D. (1998) Science 281, 821–824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Chen, H., Slepnev, V. I., Di Fiore, P. P. & De Camilli, P. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 3257–3260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cousin, M. A., Tan, T. C. & Robinson, P. J. (2001) J. Neurochem. 76, 105–116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nicholls, D. G. & Sihra, T. S. (1986) Nature 321, 772–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Marks, B. & McMahon, H. T. (1998) Curr. Biol. 8, 740–749. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Slepnev, V. I. & De Camilli, P. (2000) Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 1, 161–172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cousin, M. A. & Robinson, P. J. (2001) Trends Neurosci. 24, 659–665. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Schreiber, S. L. & Crabtree, G. R. (1992) Immunol. Today 13, 136–142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Polo, S., Sigismund, S., Faretta, M., Guidi, M., Capua, M. R., Bossi, G., Chen, H., De Camilli, P. & Di Fiore, P. P. (2002) Nature 416, 451–455. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Di Fiore, P. P., Pelicci, P. G. & Sorkin, A. (1997) Trends Biochem. Sci. 22, 411–413. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wendland, B. (2002) Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3, 971–977. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.De Camilli, P., Chen, H., Hyman, J., Panepucci, E., Bateman, A. & Brunger, A. T. (2002) FEBS Lett. 513, 11–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cadavid, A. L., Ginzel, A. & Fischer, J. A. (2000) Development (Cambridge, U.K) 127, 1727–1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen, X., Zhang, B. & Fischer, J. A. (2002) Genes Dev. 16, 289–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Taya, S., Yamamoto, T., Kanai-Azuma, M., Wood, S. A. & Kaibuchi, K. (1999) Genes Cells 4, 757–767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Haglund, K., Sigismund, S., Polo, S., Szymkiewicz, I., Di Fiore, P. P. & Dikic, I. (2003) Nat. Cell Biol. 5, 461–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rosenthal, J. A., Chen, H., Slepnev, V. I., Pellegrini, L., Salcini, A. E., Di Fiore, P. P. & De Camilli, P. (1999) J. Biol. Chem. 274, 33959–33965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Drake, M. T., Downs, M. A. & Traub, L. M. (2000) J. Biol. Chem. 275, 6479–6489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Akerman, K. E. & Nicholls, D. G. (1981) FEBS Lett. 135, 212–214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Pocock, J. M. & Nicholls, D. G. (1998) J. Neurochem. 70, 806–813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Erecinska, M., Nelson, D. & Chance, B. (1991) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 88, 7600–7604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wang, H. G., Pathan, N., Ethell, I. M., Krajewski, S., Yamaguchi, Y., Shibasaki, F., McKeon, F., Bobo, T., Franke, T. F. & Reed, J. C. (1999) Science 284, 339–343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Springer, J. E., Azbill, R. D., Nottingham, S. A. & Kennedy, S. E. (2000) J. Neurosci. 20, 7246–7251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Snyder, S. H., Lai, M. M. & Burnett, P. E. (1998) Neuron 21, 283–294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Saito, Y. & Kawashima, S. (1989) J. Biochem. (Tokyo) 106, 1035–1040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Ohtani-Kaneko, R., Takada, K., Iigo, M., Hara, M., Yokosawa, H., Kawashima, S., Ohkawa, K. & Hirata, K. (1998) Neurochem. Res. 23, 1435–1443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chan, S. L. & Mattson, M. P. (1999) J. Neurosci. Res. 58, 167–190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Fazioli, F., Minichiello, L., Matoskova, B., Wong, W. T. & Di Fiore, P. P. (1993) Mol. Cell. Biol. 13, 5814–5828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Czernik, A. J., Girault, J. A., Nairn, A. C., Chen, J., Snyder, G., Kebabian, J. & Greengard, P. (1991) Methods Enzymol. 201, 264–283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]