Summary

A child with homozygous partial deletion of the DOCK8 gene showed characteristic clinical findings of autosomal recessive hyper-IgE syndrome and full donor chimerism early after matched sibling bone marrow transplantation.

Keywords: Immunodeficiency, Hyper-IgE, Bone Marrow Transplantation, Hypereosinophilia

To the Editor:

The Hyper IgE syndromes (HIES) are rare combined immune deficiencies associated with marked elevations in plasma IgE levels and eosinophilia. An autosomal dominant form of HIES due to mutations in STAT3 is characterized by elevated IgE, eosinophilia, eczema, recurrent skin and pulmonary infections, and skeletal abnormalities1. Recently, an autosomal recessive form of HIES due to mutations in the dedicator of cytokinesis (DOCK)-8 gene has been identified and is characterized by elevated IgE levels, eosinophilia, atopic dermatitis, asthma, food allergies, recurrent upper and lower respiratory tract infections, and unusual susceptibility to infections with herpesvirus family members (herpes simplex virus (HSV), human papilloma virus (HPV)) and molluscum contagiosum 2, 3. Cutaneous infections with HPV have progressed to squamous cell carcinomas in some cases. Immunological evaluation of DOCK8 deficient patients has revealed T cell lymphopenia with impaired proliferative responses of both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells, as well as impaired differentiation of TH17 T cells2–4.

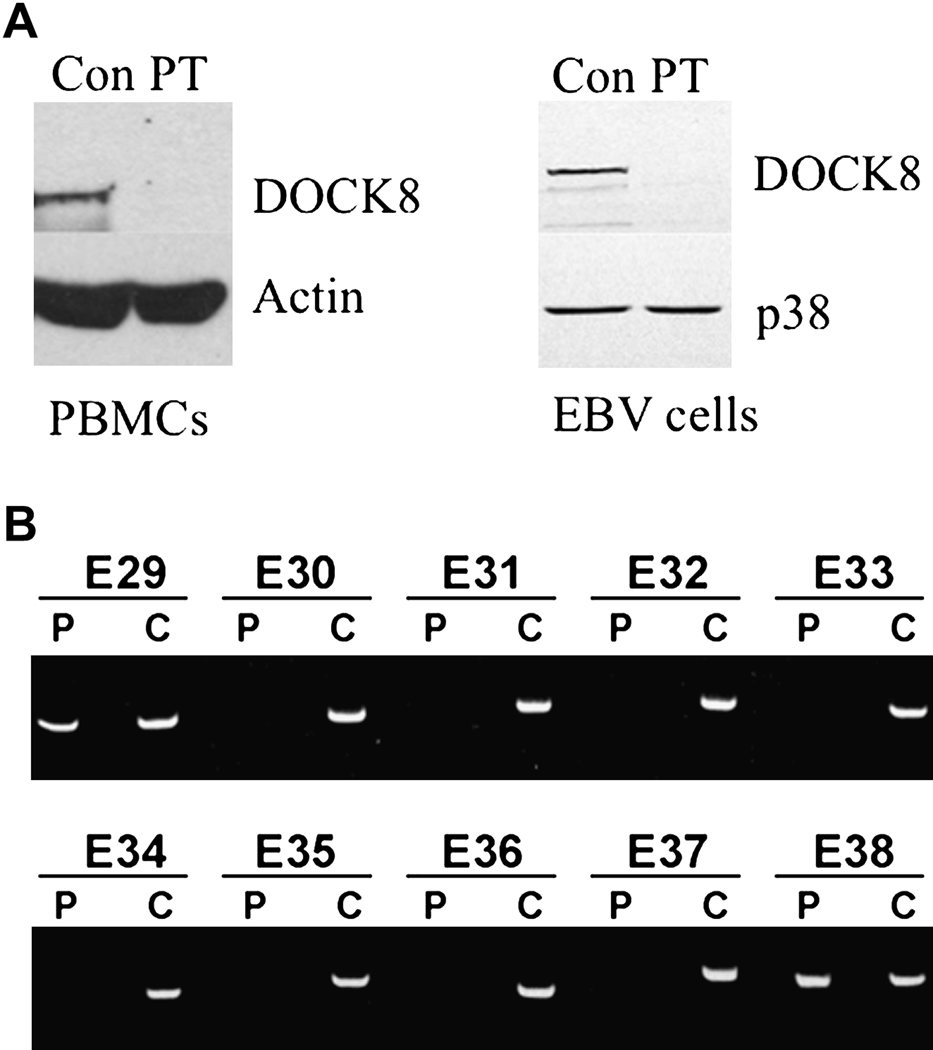

We report a case of an eight-year old girl, born to first-degree cousins, who initially presented with pneumococcal meningitis at eleven months of age, complicated by chorda tendinae rupture and flail mitral valve. Isolated asplenia was noted during imaging. She later began to suffer from recurrent episodes of upper and lower tract respiratory infections, pneumococcal bacteremia, giardiasis and cutaneous infections with HSV and S. aureus. She also developed flat warts thought to be due to HPV infection. Complete blood count revealed hypereosinophilia that ranged from 11,020 to 49,700 cells/µl (Table 1) for which she was treated with corticosteroids due to concerns of possible cardiac involvement. Bone marrow examination ruled out a leukemic process. The patient developed moderate persistent asthma and mild eczema. She had multiple food allergies, elevated total IgE (Table 1), and positive specific IgE to milk, egg, fish, peanuts, and tree nuts. The patient had received immunization with tetanus toxoid (TT) and 23-valent pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine (Pneumovax) and had protective antibody titers to TT and to 6/14 pneumococcal serotypes tested. However, titers waned by age 5 years 6 months and she failed to respond to Pneumovax booster given at age 6 years (Supplemental Table 1). Her T cell numbers decreased over time, while her B cell numbers were elevated (Supplementary Table 2). T cell proliferation to mitogens and antigens was mildly diminished (Supplemental Table 3). Serum IgG levels fell over time and the patient was started on intravenous immunoglobulin replacement therapy at age 7 years. Her clinical presentation prompted an evaluation for DOCK8 deficiency. Western blot of lysates from peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC) and an Epstein-Barr virus immortalized B cell line (EBV-B cells) revealed absence of DOCK8 protein (Figure 1A). Polymerase chain reaction amplifying genomic DNA revealed a deletion of exons 28 to 35 of the DOCK8 gene (Figure 1B).

Table 1.

Eosinophil counts and IgE levels

| Age | Absolute eosinophil count (cells/µL) |

IgE (units/ml) |

|---|---|---|

| 10 months | 1,020 | |

| 2 years 7 months | 49,700 | |

| 3 years 8 months | 22,390 | |

| 4 years | 21,710 | 930 |

| 6 years 8 months | 22,450 | 1,340 |

| 7 years 1 month | 13,340 | 574 |

| 7 years 10 months | 20,730 | 1,287 |

Figure 1.

Although experience with DOCK8 deficiency is limited, its long-term prognosis is poor. Many DOCK8 deficient patients suffer from disfiguring molluscum or HPV infections, or die from fatal infections, squamous cell cancers, or lymphoma2. Therefore, the decision was made to perform allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT) for definitive correction of her combined immune deficiency. The patient was conditioned with 16 doses of busulfan intravenously adjusted to achieve levels of 800–1200 micromole-min on days -9 to -6, and 4 doses of cyclophosphamide 50 mg/kg intravenously on days -4 to -1 without incident. She received unmanipulated bone marrow containing 10 × 106/kg of CD34+ cells from her fully matched unaffected younger brother. Cyclosporine A and short course methotrexate were given for graft versus host disease (GVHD) prophylaxis and she received standard antiviral and antifungal prophylaxis. Neutrophil engraftment occurred on day +16 followed by a rapid rise in lymphocyte count to 4,490 cells/µl on day +21. She was febrile and tachypneic with evidence of pulmonary edema with no organisms recovered from nasal secretions or sputum. Cell type specific chimerism studies on day +21 post-HCT revealed that 100% of CD3+ cells (3,536 cells/µl) and 100% of CD15+ cells (6,210 cells/µl) were of donor origin. Elevated numbers of lymphocytes were attributed to the response of normal donor cells to occult infection present prior to the transplant. Fevers and tachypnea resolved, and she was discharged on day +35 post-HCT on cyclosporine with no signs of acute GVHD. Repeat analysis of T and B lymphocyte subsets on Day +37 post-HCT revealed continued T cell engraftment and evidence of emerging naïve CD4+ and CD8+ T cells (Table 2). T cell proliferation was not evaluated because the patient continued to receive immune suppression with cyclosporine. She had neither bacterial nor viral skin infections post-HCT. She presented day +58 post-HCT to the emergency room of her local hospital with high fever and blood cultures were taken. She was started on antibiotics of appropriate coverage, and referred to our institution where she was found to have septic shock. She unfortunately died 6 hrs later of overwhelming Klebsiella pneumoniae bacteremia. Congenital asplenia may have contributed to the patient’s susceptibility to Klebsiella, as has been previously reported5.

Table 2.

Post transplant T and B cell subsets

| Post Transplant Day | Day +37 |

|---|---|

| CD3+ absolute | 706 |

| CD3+/CD4+ absolute | 520 |

| CD3+/CD8+ absolute | 142 |

| CD56+absolute | 175 |

| CD19+absolute | 2 |

| CD3+/CD4+/CD45RA+ % | 4.4 |

| CD3+/CD4+/CD45RO+ % | 95.6 |

| CD3+/CD8+/CD45RA+ % | 29.9 |

| CD3+/CD8+/CD45RO+ % | 70.1 |

In summary, we report a child with DOCK8 deficiency who underwent allogeneic HCT following myeloablative conditioning and demonstrated full donor chimerism early after transplant. These results suggest that HCT may be a viable option to treat DOCK8 deficiency. Unfortunately, the demise of the patient precluded further follow up of immune function and clinical status.

This experience demonstrates that HCT with conventional myeloablative conditioning may be potentially curative in DOCK8 deficiency, although more experience is clearly required to assess clinical outcomes. Furthermore, early diagnosis of this newly discovered immune deficiency prior to repeated infectious injury will likely optimize clinical outcomes following HCT. Because DOCK8 is expressed in both hematopoietic and non-hematopoietic tissues, further experience and long-term follow-up will be needed to determine whether correction of the hematopoietic compartment is sufficient to protect DOCK8 deficient patients from infection and cancer.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Supported by National Institutes of Health grants AI76625 (DRM), 1R21AI083907 (SYP), AI065617 and AI087627 (TC), and P01AI035714 (RSG), and Children’s Hospital Boston Translational Investigator Service Award (SYP). The authors thank Ms. Katrin Eurich for technical assistance.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Freeman AF, Holland SM. The hyper-IgE syndromes. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2008;28:277–291. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2008.01.005. viii. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhang Q, Davis JC, Lamborn IT, Freeman AF, Jing H, Favreau AJ, et al. Combined immunodeficiency associated with DOCK8 mutations. N Engl J Med. 2009;361:2046–2055. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa0905506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Engelhardt KR, McGhee S, Winkler S, Sassi A, Woellner C, Lopez-Herrera G, et al. Large deletions and point mutations involving the dedicator of cytokinesis 8 DOCK8) in the autosomal-recessive form of hyper-IgE syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:1289–1302. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.10.038. e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Al Khatib S, Keles S, Garcia-Lloret M, Karakoc-Aydiner E, Reisli I, Artac H, et al. Defects along the T(H)17 differentiation pathway underlie genetically distinct forms of the hyper IgE syndrome. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2009;124:342–348. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2009.05.004. 8 e1-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Waldman JD, Rosenthal A, Smith AL, Shurin S, Nadas AS. Sepsis and congenital aplenia. J. Pediatr. 1977;90:555–559. doi: 10.1016/s0022-3476(77)80365-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.