Abstract

Laminins are large heterotrimeric glycoproteins found in basement membranes where they play an essential role in cell-matrix adhesion, migration, growth, and differentiation of various cell types. Previous work reported that a genetic variant located within the intron 1 of LAMA5 (rs659822) was associated with anthropometric traits and HDL-cholesterol levels in a cohort of premenopausal women. The present study aimed to investigate the effect of LAMA5 rs659822 on anthropometric traits, lipid profile, and fasting glucose levels in an Italian cohort of 667 healthy elderly subjects (aged 64–107 years). We also tested for association between these traits and the single nucleotide polymorphism (SNP) rs13043313, which was previously shown to control variation in LAMA5 transcript abundance in the liver of Caucasians. In age- and gender-adjusted linear regression analyses, we did not find association of rs13043313 with any of the traits. However, under an additive model, the minor C-allele of LAMA5 rs659822 was associated with shorter stature (p =0.007) and higher fasting glucose levels (p = 0.02). Moreover, subjects homozygous for the C-allele showed on average 6% and 10% lower total cholesterol (p = 0.034) and LDL-cholesterol (p = 0.016) levels, respectively, than those carrying at least one T allele, assuming a recessive model. Finally, in analyses stratified by age groups (age range 64–89 and 90–107 years), we found that the C-allele was additively associated with increased body weight (p = 0.018) in the age group 64–89 years, whereas no association was found in the age group 90–107 years. In conclusion, this study provides evidence that LAMA5 rs659822 regulates anthropometric and metabolic traits in elderly people. Future studies are warranted to replicate these findings in independent and larger populations and to investigate whether rs659822 is the causal variant responsible for the observed associations.

Keywords: Basement membrane, laminin α5 chain, elderly people, genetic polymorphism, anthropometric traits, lipid profile

1. Introduction

Basement membranes (BM) are sheets of specialized extracellular matrix (ECM) that surrounds epithelial, endothelial, muscle, fat, and Schwann cells. The major components of the basement membranes are laminins, a family of heterotrimeric glycoproteins consisting of three different chains (α, β, and γ) (Durbeej, 2010). In mammals, different combinations of five α, four β, and three γ chains can assemble into 18 diverse laminins that have a tissue-specific distribution (Durbeej, 2010). For example, the only laminin isoform present in the basement membrane of the human pancreatic islet cells is laminin-511 (composed of α5, β1 and γ1 chains) (Otonkoski et al., 2008). Through direct interaction with other extracellular matrix proteins and cell surface receptors, laminins mediate cell-matrix adhesion and therefore regulate migration, growth, proliferation, and differentiation of various cell types (Colognato and Yurchenco, 2000). Mutation analyses of the laminin genes in humans and functional studies in laminin mouse models have demonstrated that they have an essential role in mammalian embryonic development and organogenesis ([Miner, 2008] and [Durbeej, 2010]).

The laminin α5 chain, which is found in laminin-511 and laminin-521 (α5, β2, and γ1 chains), is encoded by the LAMA5 gene that maps on chromosome 20q13.2-q13.3 (Durkin et al., 1997), within a region linked to inter-individual differences in body fat (Lembertas et al., 1997), serum lipid profile ([Soro et al., 2002] and [Li et al., 2005]), and susceptibility to type-2 diabetes (T2DM) (Lillioja and Wilton, 2009). By performing quantitative genetic studies in the fruit fly Drosophila melanogaster and a population-based study in a human cohort, De Luca et al. (De Luca et al., 2008) recently identified LAMA5 as a potential candidate gene influencing body composition traits. They showed that Caucasian premenopausal women who were homozygous for the less frequent C-allele of the LAMA5 rs659822 polymorphism had shorter stature and lower body weight, total fat mass, and lean tissue mass than those carrying at least one T allele (De Luca et al., 2008). The association of rs659822 with body weight and lean tissue mass was also observed in African-American women from the same population (De Luca et al., 2008); however, the effect of rs659822 on these traits in the African-American women had opposite direction, which suggests its context dependence with respect to other genes and/or environmental factors. In the same study, LAMA5 rs659822 was also associated with HDL-cholesterol (HDL-C) levels in the Caucasian women (De Luca et al., 2008).

Remodeling of the biochemical composition of ECM plays an important role in aging processes ([Labat-Robert, 2003] and [Candiello et al., 2010]). This observation led us to investigate the genetic effect of LAMA5 rs659822 on anthropometric traits, serum lipids, and fasting glucose in an Italian cohort of healthy elderly subjects. We also tested for association between these traits and SNP rs13043313, which lies 16 kb upstream of the transcription start site of the LAMA5 gene (http://uswest.ensembl.org). Previously, Schadt and collaborators (Schadt et al., 2008) reported a significant association between rs13043313 and variation in LAMA5 transcript abundance in the liver of Caucasian subjects (P = 2.61×10−15), we therefore reasoned that rs13043313 might be a causal variant.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Study subjects

The study was carried out in a cohort of 667 (358 women and 309 men) unrelated subjects (aged 64–107 years) who were enrolled during a recruitment campaign that started January 2002 in Calabria. Details of the recruitment process were reported in (Bellizzi et al., 2005). All subjects included in the present study were in fairly good health and did not manifest any major age-related pathology (e.g. cancer, T2DM, and cardiovascular diseases). Study participants, their parents, and grandparents were all born in Calabria as ascertained from population registers. A written informed consent was obtained from all participants before enrolling in the study.

2.2. Phenotypic measurements and genotyping

Height and weight were measured while subjects were dressed in light indoor clothes and without shoes. Blood samples were withdrawn after 12-h overnight fast and biochemical measurements were performed at the Italian National Research Centre on Ageing (Cosenza) using standard protocols as described elsewhere (Garasto et al., 2003).

The genotypes of rs659822 and rs13043313 were determined by TaqMan Real-Time allelic discrimination method (SNP Genotyping kit, Applied Biosystems). Random re-genotyping of the samples was conducted to confirm the results. Unclear genotype calls were not included in the analysis.

2.3. Statistical analysis

Hardy-Weinberg equilibrium (HWE), allelic frequencies, and D’ linkage disequilibrium coefficients were assessed using Haploview v3.2 (Barrett et al., 2005). Linear regression models were used to test the association of each SNP with trait variation adjusted for age, gender, and appropriate potential confounding variables (see Table 1), assuming additive, dominant and recessive models (Lettre et al., 2007). The age variable was dichotomized, dividing the subjects in two age groups, based on survival curves previously constructed using Italian demographic mortality data (Passarino et al., 2006). The coding of this variable was dependent on gender. Specifically, men were indicated as being in the older group when they were above the age of 88, while women were only indicated as being in the older group if they were above 91 (Passarino et al., 2006). Analyses were performed using SAS 9.1 software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). Haplotype analyses were performed using program haplo.glm from the package HAPLO.STATS version 1.2.1 (Schaid et al. 2002) in R programming language (http://cran.r-project.org/bin/windows/base/).

Table 1.

Anthropometric and metabolic characteristics of the entire study cohort stratified according to rs659822 or rs13043313 genotypes

| rs659822 | C/C | C/T | T/T | pe |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n Male/Female | 24/21 | 115/146 | 170/191 | |

| Age (y) | 86.2±0.6 | 86.2±0.7 | 86.7±1.7 | |

| logBMI (kg/m2) | 3.23±0.02 | 3.22±0.01 | 3.21±0.01 | 0.311 |

| Height (cm)a | 154.9±0.7 | 156.1±0.3 | 157.3±0.4 | 0.007 |

| Weight (kg)b | 63.9±1.0 | 62.9±0.5 | 61.9±0.5 | 0.108 |

| logFasting glucose (mg/dl)c | 4.68±0.03 | 4.64±0.01 | 4.60±0.01 | 0.020 |

| logTriglycerides (mg/dl)c | 4.72±0.04 | 4.72±0.02 | 4.72±0.02 | 0.955 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl)d | 193.8±3.8 | 197.2±1.9 | 200.6±1.9 | 0.150, 0.034f |

| HDL-C (mg/dl)d | 4.02±0.02 | 4.02±0.01 | 4.03±0.01 | 0.724 |

| LDL-C (mg/dl)d | 113.0±3.4 | 116.0±1.7 | 119.0±1.7 | 0.156, 0.016f |

| rs13043313 | C/C | C/T | T/T | |

| n Male/Female | 17/24 | 137/148 | 154/182 | |

| Age (y) | 87.4±1.8 | 86.3±0.7 | 86.3±0.6 | |

| logBMI (kg/m2) | 3.23±0.02 | 3.22±0.01 | 3.21±0.01 | 0.497 |

| Height (cm)a | 156.0±0.7 | 156.5±0.3 | 157.0±0.4 | 0.271 |

| Weight (kg)b | 63.2±1.0 | 62.7±0.5 | 62.2±0.5 | 0.439 |

| logFasting glucose (mg/dl)c | 4.67±0.02 | 4.64±0.01 | 4.61±0.01 | 0.084 |

| logTriglycerides (mg/dl)c | 4.72±0.04 | 4.72±0.02 | 4.73±0.02 | 0.935 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl)d | 195.2±3.8 | 197.7±1.8 | 200.1±2.0 | 0.309 |

| HDL-C (mg/dl)d | 4.02±0.02 | 4.03±0.01 | 4.03±0.01 | 0.945 |

| LDL-C (mg/dl)d | 114.0±3.4 | 116.4±1.6 | 119.0±1.8 | 0.242 |

Data represent means ± SE. BMI: body mass index. HDL-C: HDL-cholesterol. LDL-C: LDL-cholesterol. BMI, fasting glucose, and triglyceride levels were log10 transformed to fulfill the assumption of normality.

Adjusted for gender and age.

Adjusted for gender, age, and height.

Adjusted for gender, age, and logBMI.

Adjusted for gender, age, logBMI, and logTriglycerides.

p values represent the significance of the comparison among genotypes. p values without superscript were calculated assuming additive models.

p values with superscript (f) were calculated assuming a recessive model.

3. Results

The minor C-allele frequencies of rs659822 and rs13043313 in our cohort were 0.263 and 0.277, respectively. All genotype groups were in HWE (P > 0.05) and the genotyping efficiencies were 99.9% for rs659822 and 99.3% for rs13043313. Our analysis showed that LAMA5 rs659822 is in LD with rs13043313 (D’ = 0.69), which is consistent with data from the HapMap Project in the CEU population (http://hapmap.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). The estimated frequencies of the TT, TC, CT, and CC haplotypes were 0.665, 0.072, 0.054, and 0.204, respectively.

The means (and standard errors) of the anthropometric and metabolic variables of the study subjects stratified according to rs659822 or rs13043313 genotypes are shown in Table 1. Contrary to our prediction, there was no association of SNP rs13043313 with any of the phenotypic traits in the analysis pooled across age and gender (Table 1). However, we found a significant association between LAMA5 rs659822 and height assuming a model of additive effect (Table 1). Each copy of the minor C-allele reduced height by 1.18 cm (95% confidence interval (CI) 0.32–2.04) in our cohort of elderly subjects, which is an effect size similar to the one previously seen in Caucasian premenopausal women (~2.3cm difference; p = 0.02) (De Luca et al., 2008). Assuming the additive model, we also observed an association between LAMA5 rs659822 and fasting glucose levels (Table 1), with each copy of the minor C-allele increasing the log of fasting glucose levels by 3.89% (95% CI 0.61%–7.28%). Finally, when a recessive model of inheritance was applied, we found that individuals homozygous for the C-allele had on average 6% and 10% less total cholesterol (CC: 187.4 ± standard error (SE) 5.58 mg/dl; TC + TT: 199.6 ± 1.99 mg/dl) and LDL-C (CC: 105.8 ± 5.0 mg/dl; TC + TT: 118.2 ± 1.36 mg/dl), respectively, than those carrying at least one T allele (Table 1). Pairwise haplotype-based association analyses between rs659822 and rs13043313 did not increase the power of these associations (Table 2).

Table 2.

P-values for haplotype effects.

| Trait | CC | CT | TC |

|---|---|---|---|

| logBMI (kg/m2) | 0.3677 | 0.6454 | 0.9841 |

| Height (cm)a | 0.0603 | 0.0453 | 0.6975 |

| Weight (kg)b | 0.1988 | 0.4076 | 0.7021 |

| logFasting glucose (mg/dl)c | 0.0927 | 0.0136 | 0.1139 |

| logTriglycerides (mg/dl)c | 0.9484 | 0.7452 | 0.8480 |

| Total cholesterol (mg/dl)d | 0.3023 | 0.1721 | 0.5352 |

| HDL-C (mg/dl)d | 0.8889 | 0.6182 | 0.9968 |

| LDL-C (mg/dl)d | 0.2308 | 0.3421 | 0.5974 |

P-values in this table are for the test of the effect of the given haplotype compared to the reference haplotype (TT). HDL-C: HDL-cholesterol. LDL-C: LDL-cholesterol. BMI, fasting glucose, and triglyceride levels were log10 transformed to fulfill the assumption of normality.

Adjusted for gender and age.

Adjusted for gender, age, and height.

Adjusted for gender, age, and logBMI.

Adjusted for gender, age, logBMI, and logTriglycerides.

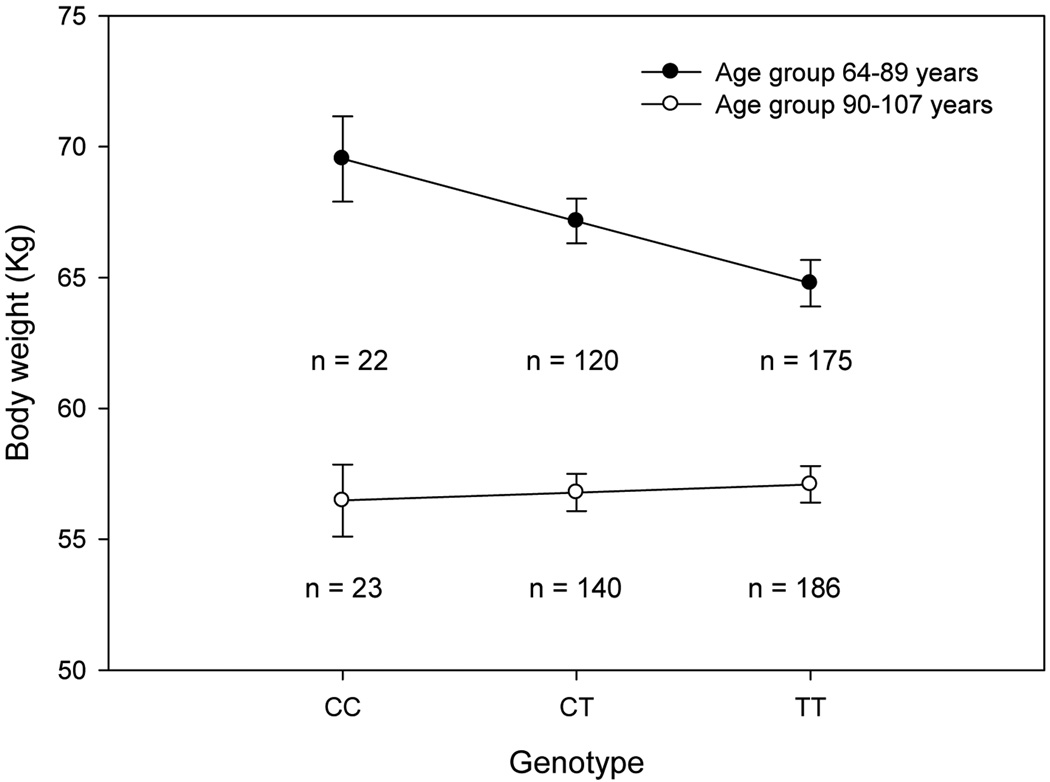

Previous work has suggested that the effect of a given allele may change in the cell microenvironment of long-lived people ([Conboy and Rando, 2005] and [Passarino et al., 2006]). Because our cohort included nonagenarians and centenarians, we next included into the models an interaction term between rs659822 and age group. Our results showed a significant rs659822-by-age group interaction term for body weight under the additive (interaction p = 0.052) and dominant (interaction p = 0.042) models, suggesting that the effect of SNP rs659822 on these traits was not homogeneous across the two age groups. Thus, we decided to analyze the data separately for the age range 64-89 and 90–107 years. While no difference was observed in the group of people aged 90-107 years, we found that the C-allele was additively associated with increased body weight in the age group 64–89 years (Figure 1), with each C-allele increasing body weight by 2.38 kg (95% CI 0.42–4.34). The lack of association in the very old people is not due to differences in genotype frequencies since no statistical differences were observed between the two age groups (χ2 = 0.617, p =0.735).

Figure 1.

Body weight by rs659822 genotype in two groups aged 64–89 and 90–107 years. Data represent means ± SE. In the age group 64–89 years, there was a significant difference among rs659822 genotypes in body weight (p = 0.018; adjusted for height and gender). In the age group 90–107 years, there was no difference (p = 0.706). n = number of subjects within each genotype.

4. Discussion

The present study provides evidence that the minor C-allele of LAMA5 rs659822 is associated with reduced adult height in Caucasian elderly people as previously observed in a cohort of premenopausal women (De Luca et al., 2008). Whether rs659822, which is located within the intron 1 of LAMA5, is the causal variant and the mechanism behind its effect on height remain to be elucidated. Studies in mice have previously shown that embryos of animals deficient in the laminin α5 chain exhibit several developmental abnormalities, including dysmorphogenesis of the placental labyrinth (Miner 2008), which is necessary for gas exchange and the transfer of nutrition between the maternal and fetal circulation (Cross et al., 2002), and die late in embryogenesis (Miner, 2008). These studies have also revealed that laminin α5 plays an important role in kidney development by controlling glomerulogenesis (Miner, 2008). Furthermore, three-week old mice homozygous for a hypomorphic mutation in the Lama5 gene have been reported to display loss of renal function and smaller size than controls (Miner, 2008). In humans, body size at birth, which is influenced by both the genetically predisposed fetus and intrauterine environmental factors, is positively correlated with adult height ([Sorensen et al. 1999] and [Tuvemo et al., 1999]). Thus, it is possible that genetic variation in LAMA5 may affect fetal growth and organ development, and ultimately influence organ functions and body size in adult life, by modulating placental development and function. This hypothesis deserves further investigation considering that fetal and placental size and the consequent infant size at birth have been shown to be important predictors for the development of obesity, hypertension, T2DM, and cardiovascular disease later in life (Barker, 1990). Consistently, short stature has been associated with increased risk of coronary heart disease, T2DM, and glucose intolerance ([Paajanen et al., 2010] and [Lawlor et al., 2002]). Our study cohort was composed of healthy elderly subjects, but our finding of a significant association of rs659822 C-allele with fasting hyperglycemia in the entire cohort and body weight in the subjects aged 64-89 years is consistent with the hypothesis of a potential role of LAMA5 in fetal programming. A study examining the effect of LAMA5 rs659822 on anthropometric traits in pre-pubertal children is currently underway to provide additional evidence. Nevertheless, given the crucial role that ECM remodeling plays in skeletal development (Ortega et al., 2004) as well as in white adipose tissue development and growth (Mariman and Wang, 2010), we cannot exclude the possibility that other mechanisms, not necessarily exclusive, may underlie our findings.

One important result of the present study is that despite the genetic predisposition to gain weight conferred by the C-allele of LAMA5 rs659822 seen in subjects 64–89 years of age, individuals homozygous for this allele who have reached 90 or more years did not show any significant difference in body weight compared to those with at least one T allele (Figure 1). Because data on body composition measurements were not available, we cannot say at this point whether the effect of rs659822 C-allele on body weight is driven by increased fat mass and/or reduced lean mass. Whatever the tissue, one possible explanation for our results is that the effect of the LAMA5 rs659822 allele on body weight may be influenced by the remodeling of the physiological function that occurs with aging ([Barbieri et al., 2009] and [Capri et al., 2008]). Furthermore, since energy intake rate has been shown to alter the expression of extracellular matrix genes in mice adipose tissue (Higami et al., 2006), the effect of the allele could also be modulated by differences in dietary patterns between the two age groups. Our finding might have important implications for previous work by Paolisso and collaborators (Paolisso et al., 1995) who reported that healthy centenarians are less prone to the changes in body composition associated with aging and future studies are warranted to further investigate this matter.

In this study we did not replicate the association between LAMA5 rs659822 and HDL-C previously observed in pre-menopausal women (De Luca et al., 2008). The failure to replicate the association in a population with distinct genetic background and different age might reflect the complexity of the genetic processes that determine variation in this trait, including potential epistatic interactions between genetic variation in LAMA5 and other gene polymorphisms (Greene et al., 2009). On the other hand, we found that subjects homozygous for the C-allele had lower total cholesterol and LDL-C than those with at least one T allele, further suggesting that LAMA5 plays a role in cholesterol metabolism. In this regard, it is noteworthy to mention that Idaghdour et al. (Idaghdour et al., 2010) have recently provided evidence of a regulatory relationship at the transcriptional level between LAMA5 and OSBPL2 genes. OSBPL2 encodes the oxysterol binding protein-like 2 (ORP2) which belongs to a family of intracellular lipid receptors (Fairn and McMaster, 2008). Previous work reported that ORP2 regulates cholesterol homeostasis by controlling cholesterol trafficking and the endocytic pathway involved in the transport of LDL-derived cholesterol into the cell (Hynynen et al., 2005). Hence, it is possible that OSBPL2 represents the molecular link between LAMA5 and cholesterol metabolism.

In conclusion, our data provides evidence of a role of LAMA5 in regulating anthropometric and metabolic traits in elderly people. It also shows that the effect of LAMA5 rs659822 on body weight seen in subjects aged 65–89 years is blunted in the group of people who have reached 90 or more years. These findings motivate future work to investigate whether LAMA5 rs659822 is the casual variant and the mechanisms behind the observed genetic associations.

Acknowledgments

The work was supported by NIH grant R01DK084219 to MD and Fondi di Ateneo Unical (ex 60%) to GP and GR.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Barbieri M, Boccardi V, Papa M, Paolisso G. Metabolic journey to healthy longevity. Horm. Res. 2009;1:24–27. doi: 10.1159/000178032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barker DJ. The fetal and infant origins of adult disease. BMJ. 1990;301:1111. doi: 10.1136/bmj.301.6761.1111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barrett JC, Fry B, Maller J, Daly MJ. Haploview: analysis and visualization of LD and haplotype maps. Bioinformatics. 2005;21:263–265. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bth457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bellizzi D, Rose G, Cavalcante P, Covello G, Dato S, De Rango F, Greco V, Maggiolini M, Feraco E, Mari V, et al. A novel VNTR enhancer within the SIRT3 gene, a human homologue of SIR2, is associated with survival at oldest ages. Genomics. 2005;85:258–263. doi: 10.1016/j.ygeno.2004.11.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Candiello J, Cole GJ, Halfter W. Age-dependent changes in the structure, composition and biophysical properties of a human basement membrane. Matrix Biol. 2010;29:402–410. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2010.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capri M, Salvioli S, Monti D, Caruso C, Candore G, Vasto S, Olivieri F, Marchegiani F, Sansoni P, Baggio G, et al. Human longevity within an evolutionary perspective: The peculiar paradigm of a post-reproductive genetics. Exp. Gerontol. 2008;43:53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.exger.2007.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colognato H, Yurchenco PD. Form and function: The laminin family of heterotrimers. Developmental Dynamics. 2000;218:213–234. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(200006)218:2<213::AID-DVDY1>3.0.CO;2-R. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Conboy IM, Rando TA. Aging, stem cells and tissue regeneration: lessons from muscle. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:407–410. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.3.1518. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross JC, Hemberger M, Lu Y, Nozaki T, Whiteley K, Masutani M, Adamson SL. Trophoblast functions, angiogenesis and remodeling of the maternal vasculature in the placenta. Mol. Cell Endocrinol. 2002;187:207–212. doi: 10.1016/s0303-7207(01)00703-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Luca M, Chambers MM, Casazza K, Lok KH, Hunter GR, Gower BA, Fernandez JR. Genetic variation in a member of the laminin gene family affects variation in body composition in Drosophila and humans. BMC Genet. 2008;9:52. doi: 10.1186/1471-2156-9-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durbeej M. Laminins. Cell Tissue Res. 2010;339:259–268. doi: 10.1007/s00441-009-0838-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durkin ME, Loechel F, Mattei MG, Gilpin BJ, Albrechtsen R, Wewer UM. Tissue-specific expression of the human laminin α5-chain, and mapping of the gene to human chromosome 20q13. 2-13.3 and to distal mouse chromosome2 near the locus for the ragged (Ra) mutation. FEBS Letters. 1997;411:296–300. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(97)00686-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fairn GD, McMaster CR. Emerging roles of the oxysterol-binding protein family in metabolism, transport, and signaling. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2008;65:228–236. doi: 10.1007/s00018-007-7325-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garasto S, Rose G, De Rango F, Berardelli M, Corsonello A, Feraco E, Mari V, Maletta R, Bruni A, Franceschi C, et al. The study of APOA1, APOC3 and APOA4 variability in healthy ageing people reveals another paradox in the oldest old subjects. Ann. Hum. Genet. 2003;67:54–62. doi: 10.1046/j.1469-1809.2003.00008.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greene CS, Penrod NM, Williams SM, Moore JH. Failure to replicate a genetic association may provide important clues about genetic architecture. PLoS One. 2009;4:e5639. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0005639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higami Y, Barger JL, Page GP, Allison DB, Smith SR, Prolla TA, Weindruch R. Energy Restriction Lowers the Expression of Genes Linked to Inflammation, the Cytoskeleton, the Extracellular Matrix, and Angiogenesis in Mouse Adipose Tissue. J. Nutr. 2006;136:343–352. doi: 10.1093/jn/136.2.343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hynynen R, Laitinen S, Kakela R, Tanhuanpaa K, Lusa S, Ehnholm C, Somerharju P, Ikonen E, Olkkonen VM. Overexpression of OSBP-related protein 2 (ORP2) induces changes in cellular cholesterol metabolism and enhances endocytosis. Biochem. J. 2005;390:273–283. doi: 10.1042/BJ20042082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Idaghdour Y, Czika W, Shianna KV, Lee SH, Visscher PM, Martin HC, Miclaus K, Jadallah SJ, Goldstein DB, Wolfinger RD, et al. Geographical genomics of human leukocyte gene expression variation in southern Morocco. Nat. Genet. 2010;42:62–67. doi: 10.1038/ng.495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- J Labat-Robert J. Age-dependent remodeling of connective tissue: role of fibronectin and laminin. Pathol. Biol. 2003;51:563–568. doi: 10.1016/j.patbio.2003.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawlor DA, Ebrahim S, Davey SG. The association between components of adult height and Type II diabetes and insulin resistance: British Women's Heart and Health Study. Diabetologia. 2002;45:1097–1106. doi: 10.1007/s00125-002-0887-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lembertas AV, Perusse L, Chagnon YC, Fisler JS, Warden CH, Purcell-Huynh DA, Dionne FT, Gagnon J, Nadeau A, Lusis AJ, et al. Identification of an obesity quantitative trait locus on mouse chromosome 2 and evidence of linkage to body fat and insulin on the human homologous region 20q. J. Clin. Invest. 1997;100:1240–1247. doi: 10.1172/JCI119637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lettre GG, Lange C, Hirschhorn JN. Genetic model testing and statistical power in population-based association studies of quantitative traits. Genet. Epidemiol. 2007;31:358–362. doi: 10.1002/gepi.20217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li WD, Dong C, Li D, Garrigan C, Price RA. A genome scan for serum triglyceride in obese nuclear families. J. Lipid. Res. 2005;46:432–438. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M400391-JLR200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillioja S, Wilton A. Agreement among type 2 diabetes linkage studies but a poor correlation with results from genome-wide association studies. Diabetologia. 2009;52:1061–1074. doi: 10.1007/s00125-009-1324-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mariman EC, Wang P. Adipocyte extracellular matrix composition, dynamics and role in obesity. Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 2010;67:1277–1292. doi: 10.1007/s00018-010-0263-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miner JH. Laminins and their roles in mammals. Microsc. Res. Tech. 2008;71:349–356. doi: 10.1002/jemt.20563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ortega N, Behonick DJ, Werb Z. Matrix remodeling during endochondral ossification. Trends Cell. Biol. 2004;14:86–93. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2003.12.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Otonkoski T, Banerjee M, Korsgren O, Thornell LE, Virtanen I. Unique basement membrane structure of human pancreatic islets: implications for beta-cell growth and differentiation. Diabetes Obes. Metab. 2008;10 Suppl 4:119–127. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2008.00955.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paajanen TA, Oksala NK, Kuukasjarvi P, Karhunen PJ. Short stature is associated with coronary heart disease: a systematic review of the literature and a meta-analysis. Eur. Heart J. 2010;31:1802–1809. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehq155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paolisso G, Gambardella A, Balbi V, Ammendola S, D'Amore A, Varricchio M. Body composition, body fat distribution, and resting metabolic rate in healthy centenarians. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1995;62:746–750. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/62.4.746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passarino G, Montesanto A, Dato S, Giordano S, Domma F, Mari V, Feraco E, De Benedictis G. Sex and age specificity of susceptibility genes modulating survival at old age. Hum. Hered. 2006;62:213–220. doi: 10.1159/000097305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schadt EE, Molony C, Chudin E, Hao K, Yang X, Lum PY, Kasarskis A, Zhang B, Wang S, Suver C, et al. Mapping the genetic architecture of gene expression in human liver. PLoS Biol. 2008;6:e107. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaid DJ, Rowland CM, Tines DE, Jacobson RM, Poland GA. Score tests for association between traits and haplotypes when linkage phase is ambiguous. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2002;70:425–434. doi: 10.1086/338688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sorensen HT, Sabroe S, Rothman KJ, Gillman M, Steffensen FH, Fischer P, Sorensen TI. Birth weight and length as predictors for adult height. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1999;149:726–729. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soro A, Pajukanta P, Lilja HE, Ylitalo K, Hiekkalinna T, Perola M, Cantor RM, Viikari JS, Taskinen MR, Peltonen L. Genome scans provide evidence for low-HDL-C loci on chromosomes 8q23, 16q24.1-24.2, and 20q13.11 in Finnish families. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2002;70:1333–1340. doi: 10.1086/339988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tuvemo T, Cnattingius S, Jonsson B. Prediction of male adult stature using anthropometric data at birth: a nationwide population-based study. Pediatr. Res. 1999;46:491–495. doi: 10.1203/00006450-199911000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]