Abstract

Background

Chronic maltreatment has been associated with the poorest developmental outcomes, but its effects may depend on the age when the maltreatment began, or be confounded by co-occurring psychosocial risk factors.

Method

We used data from the National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being (NSCAW) to identify four groups of children who varied in the timing, extent, and continuity of their maltreatment from birth to 9 years. Internalizing and externalizing problems, prosocial behavior, and IQ were assessed 21 months, on average, following the most recent maltreatment report.

Results

Children maltreated in multiple developmental periods had more externalizing and internalizing problems and lower IQ scores than children maltreated in only one developmental period. Chronically maltreated children had significantly more family risk factors than children maltreated in one developmental period and these accounted for maltreatment chronicity effects on externalizing and internalizing problems, but not IQ. The timing of maltreatment did not have a unique effect on cognitive or behavioral outcomes, although it did moderate the effect of maltreatment chronicity on prosocial behavior.

Conclusion

There is a need for early intervention to prevent maltreatment from emerging and to provide more mental health and substance use services to caregivers involved with child welfare services.

Keywords: NSCAW, maltreatment, abuse, neglect

Approximately 905,000 children in the United States were substantiated victims of abuse or neglect in 2006 (U.S.Department of Health and Human Services, 2008). Childhood maltreatment is associated with poor cognitive outcomes and school adaptation problems, behavioral problems and peer relationship difficulties, maladaptive development of self-concept, and diagnoses of most Axis I disorders (as reviewed by Cicchetti & Valentino, 2006). Many of these adverse sequelae persist into adulthood (Arnow, 2004).

Depending on the length of follow-up, anywhere from a third to a half of children who are reported for maltreatment are reported on multiple occasions (Thompson & Wiley, 2009). Compared with non-maltreated children, those who experience chronic maltreatment are characterized by increased levels of peer problems (Bolger, Patterson, & Kupersmidt, 1998), aggressive and delinquent behavior (Manly, Cicchetti, & Barnett, 1994; Manly, Kim, Rogosch, & Cicchetti, 2001; Stewart, Livingston, & Dennison, 2008; Thornberry, Ireland, & Smith, 2001), internalizing symptoms and withdrawn behavior (Éthier, Lemelin, & Lacharité, 2004; Manly et al., 2001), and decreased prosocial behavior (Manly et al., 2001).

Chronically maltreated children also have more problems compared with children experiencing more transitory maltreatment. Manly et al. (2001) showed that children who experienced chronic maltreatment originating in the preschool period had more externalizing problems and lower levels of ego resilience than other maltreated children. Other studies have shown that chronically maltreated children have higher rates of juvenile offending (Stewart et al., 2008), poorer peer relations (particularly among those who were physically abused) (Bolger et al., 1998), increasing levels of anxious and depressed behaviors over time (Éthier et al., 2004) more behavior problems overall (Éthier et al., 2004), increased levels of aggressive behavior, depression and post-traumatic stress symptoms, and decreased levels of interpersonal and coping skills (English, Graham, Litrownik, Everson, & Bangdiwala, 2005) in comparison with children who experienced transitory maltreatment. In summary, the literature suggests that chronically maltreated children not only have more problem behaviors (including problems with peers) compared with non-maltreated children, but also compared with other maltreated children. To our knowledge, no studies have tested whether chronically maltreated children have cognitive deficits compared with other maltreated children. However, we might expect to see such differences considering that maltreated children tend to have poorer cognitive abilities and school performance compared with non-maltreated children (Trickett & McBride-Change, 1995).

Only a few studies (Bolger et al., 1998; Manly et al., 1994; Manly et al., 2001) have tested whether the effects of chronicity depend on other features of the maltreatment (such as when in the child's development it first occurred). Organizational developmental theory would support the hypothesis that maltreatment would be the most detrimental for children when it originated in infancy and extended to later developmental periods. This theory proposes that children encounter challenges in biological, cognitive, and affective domains at every stage of development. Successful resolution of these issues engenders successful adaptation at later stages (Sroufe & Rutter, 1984). Thus, maltreatment beginning in infancy and extending into later developmental periods would undermine the mastery of early developmental tasks and decrease the probability that children would encounter subsequent opportunities and supports that would deflect them from a maladaptive trajectory (Cicchetti & Toth, 1995). In contrast, children whose maltreatment was limited to the infancy period or who first experienced maltreatment at later stages of development might have the opportunity to either recover functioning or fall back on skills that consolidated before the maltreatment began.

There is very little data on whether chronicity effects vary depending on the age of onset of maltreatment. Contrary to theoretical predictions, Manly et al. (2001) showed that chronic maltreatment originating in the preschool period rather than the infancy period was associated with elevated externalizing problems relative to maltreatment that was restricted to one developmental period. Bolger et al. (1998) did not find that chronicity effects on measures of peer relationships and self-esteem varied as a function of age-of-onset of maltreatment. More data are needed to determine whether there are particular developmental periods when it is especially important to prevent maltreatment recurrence.

Determining the unique effects of chronic maltreatment on children's development is made more challenging by the fact that chronically maltreated children often come from families characterized by high levels of other psychosocial risk factors. For example, compared to those with a single referral, children who are re-referred to child welfare services tend to come from families with low socioeconomic status, low social support, and relatively high rates of caregiver mental health, drug, and alcohol problems (Hindley, Ramchandani, & Jones, 2006; Thompson et al., 2009). Thus, the observed effects of chronicity could reflect the influence of these other risk factors for children's development. At least one study controlled for an extensive array of family and neighborhood covariates and still found unique effects of chronic maltreatment on child outcome (Thornberry et al., 2001). Others have primarily controlled for family demographic characteristics, either by matching non-maltreated and maltreated groups on variables like family income or welfare receipt (Bolger et al., 1998; Manly et al., 2001) or by statistically controlling for them (Éthier et al., 2004). Thus, it is not possible in these studies to determine how much of the chronicity effect is accounted for by correlated risk factors. Still others have not controlled for any family or neighborhood covariates (English et al., 2005; Stewart et al., 2008). None to our knowledge have simultaneously estimated the effects of parental depression, criminality and substance use problems. To the extent that these could reflect familial risk for problem behaviors that parents transmit to children, it would be particularly important to determine whether they confound the relationship between maltreatment chronicity and child problem behaviors. Indeed, controlling for parental psychopathology tends to reduce substantially the adverse effect of maltreatment on child behavior, even if the effect remains significant (Jaffee, Caspi, Moffitt, & Taylor, 2004).

The goal of this study was to use data from a large, longitudinal study of children who were referred to child welfare services to test whether chronic maltreatment was associated with the poorest outcomes, whether the effects of chronicity depended on when maltreatment was first reported to occur, whether children who experienced chronic maltreatment were characterized by high levels of other family and neighborhood risk factors, and whether these additional risks accounted for any relationship between maltreatment chronicity and children's outcomes. Chronicity was defined as having occurred across multiple periods of psychosocial development from infancy through the early school years. Such developmental definitions of chronicity have been shown to be optimally sensitive to variation in child outcome (English et al., 2005). We hypothesized that (a) chronic maltreatment would be associated with poorer outcomes than maltreatment occurring in only one developmental period; (b) the effects of chronicity would be exacerbated if children first experienced maltreatment starting in infancy; and (c) chronic maltreatment would be associated with additional family and neighborhood risks, and (d) these correlated risks would partially account for observed associations with child outcome. We focused on children's IQ and externalizing, internalizing, and prosocial behaviors because all four were measured repeatedly and from early in the child's life in NSCAW and because the latter three are associated with chronic versus more transitory maltreatment; our inclusion of IQ was more exploratory.

Method

The National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being (NSCAW) is a nationally-representative sample of children in the United States who have had contact with Child Protective Services (CPS; Dowd et al., 2004). The full cohort includes 5,501 children (50% female), less than 1 year to 16 years of age when sampled, who were subjects of abuse or neglect investigations conducted by child welfare services from October 1999-December 2000. Additional details about sample selection and composition are available from Dowd and colleagues (2004).

Children, current caregivers, teachers, and caseworkers were interviewed at 5 points: 2-6 months (wave 1), 12 months (wave 2), 18 months (wave 3), 36 months (wave 4), and 59-96 months (wave 5) following the close of the child's investigation. With one exception, we did not use the wave 2 data, as the interview protocol differed from that of other waves. Wave 5 was fielded by age cohort, with the result that wave 5 data are only available for children who were 48 months or younger at wave 1. Retention rates ranged from 80% to 87% across waves. Informed consent was obtained from caregivers and written assent was obtained from children 7 years and older. Current caregivers were paid $50 for their participation at each wave and children were given gift certificates worth $10-$20.

The subsample for the current study comprises 1,777 children (46% female) who ranged in age from 1 to 107 months at wave 1 (M=35.74, SD=31.86) and had no prior documented history of maltreatment before being sampled for NSCAW. Thirty-one percent were Black-Non-Hispanic, 43% were White-Non-Hispanic, 18% were Hispanic, and 7% were from other racial/ethnic groups. The sample was restricted to children younger than nine years at baseline because including older children resulted in empty cells of the research design.

Because the NSCAW weights are highly variant whole sample weights, they are not appropriate for use with small subsamples (Dowd et al., 2004), and were not used in these analyses.

Measures

Maltreatment chronicity and developmental period

Consistent with English et al. (2005) we derived a measure of chronicity that reflected the extent and continuity of maltreatment across developmental periods. Four developmental periods were identified consistent with Erikson's stages of psychosocial development (Erikson, 1963): infancy (0-18 months), toddlerhood (18 months to 3 years), preschool (3-6 years), and early school years (6-9 years). Data on the child's age at wave 1 (which was 2-6 months following the close of the investigation that made them eligible for participation in NSCAW) and caseworker and caregiver reports of maltreatment at subsequent waves were used to determine the developmental periods in which children experienced maltreatment. Because children were selected to have no prior history of CPS reports before their recruitment to NSCAW, the child's age at wave 1 was used to identify the developmental period in which maltreatment first occurred: before 18 months (46%), 18 months to 3 years (14%), 3 to 6 years (20%), and 6 to 9 years (20%).

From wave 2 onwards, caseworkers reported the dates of any new abuse or neglect reports since the previous report date. Caseworker data were available for a subset of children at waves 2-5 (children and families who were currently receiving services or had been receiving services since the previous wave of data collection; from 51% at wave 2 to 10% at wave 5). Of those with caseworker data, the proportion of children with new reports of maltreatment after wave 1 ranged from 18% at wave 2 to 53% at wave 5. We did not differentiate between substantiated and unsubstantiated new reports because many unsubstantiated cases involve some form of maltreatment or need for CPS intervention (Drake, 1996), studies show that substantiation status is a relatively poor predictor of re-referral to CPS in NSCAW (Kohl, Johnson-Reid, & Drake, 2009) as well as other samples (Drake, Jonson-Reid, Way, & Chung, 2003; English, Marshall, Coghlan, Brummel, & Orme, 2002; but see Fuller & Nieto, 2009 for an exception), and children with and without substantiated referrals have equally high levels of problem behaviors (Hussey et al., 2005; Jaffee & Gallop, 2007), though this may depend on the type of maltreatment or the child outcome (Maikovich, Koenen, & Jaffee, 2009).

Caregiver reports of maltreatment were available at waves 3, 4, and 5 for all children who were living with permanent caregivers (82% at wave 3 to 96% at wave 5). Caregivers used an audio computer assisted self interview (ACASI) to answer questions from the Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scale (CTS-PC) (Straus, Hamby, Finkelhor, Moore, & Runyan, 1998) regarding how many times in the past 12 months children experienced normative and non-normative forms of discipline. Of interest were caregiver reports of maltreatment including severe and very severe physical assault as well as sexual violence and neglect (minor physical assault was excluded because it captured more normative forms of corporal punishment). The proportions of caregivers reporting any of these types of maltreatment were 25% (wave 3), 26% (wave 4), and 27% (wave 5). Agreement between caseworker and caregiver reports of maltreatment was not calculated because few children had information from both sources, and caregivers and caseworkers were not always reporting over identical time-frames.

To derive a measure of maltreatment extent, we counted the number of developmental periods in which children experienced maltreatment as reported by caseworkers or caregivers, with maltreatment in one developmental period being defined as situational (57%), in two developmental periods as limited (31%), and in three or four developmental periods as extensive (12%). To derive a measure of maltreatment continuity, we determined whether children were maltreated in adjacent developmental periods. Maltreatment chronicity was thus defined by crossing information about extent and continuity, yielding four groups: situational maltreatment (occurring in one developmental period, 57%), limited/discontinuous maltreatment (occurring in two non-adjacent developmental periods, 15%), limited/continuous maltreatment (occurring in two adjacent developmental periods, 16%), and extensive/continuous maltreatment (occurring across 3 or 4 adjacent developmental periods, 12%). No child had extensive/discontinous maltreatment.

Behavioral measures

Caregivers reported on past 6-month internalizing and externalizing behaviors at each wave using the Preschool Behavior Checklist (PBC) for 2- to 4-year-olds and the Child Behavior Checklist (CBCL) for children 4 years or older (Achenbach, 1991). Responses were scored from 0 “not true” to 2 “very true or often true.” The internal consistency reliabilities of the PBC and CBCL externalizing scale and internalizing scales were acceptable (all .80 or higher). Standardized T scores were used in all analyses (externalizing: M = 53.42, SD = 11.20; internalizing: M = 51.66, SD = 10.62). T scores greater than or equal to 64 reflect clinically significant internalizing or externalizing problems (Achenbach & Rescorla, 2001).

Prosocial behavior was measured at each wave with the Social Skills Rating System (SSRS; Gresham & Elliot, 1990), which asks caregivers how often children engage in behaviors that demonstrate cooperation, responsibility, assertion, and self-control. Responses were scored from 1 “never” to 3 “often.” Age-appropriate forms were available for children aged 3-5 and 6-10 years; internal consistency reliability was acceptable in both groups (α = .90). The SSRS produces standardized T scores; scores greater than 84 are indicative of moderate to high social competence (M = 92.29, SD = 16.07).

IQ was estimated at each wave for children 4 years and older with the Kaufman Brief Intelligence Test (K-BIT), which assesses verbal intelligence with the Vocabulary subscale and nonverbal intelligence with the Matrices subscale. Standardized Vocabulary and Matrices subscale scores were summed to create composite IQ scores (M = 93.76, SD = 15.06). Internal consistency reliability (α = .84) was acceptable for the composite K-BIT score. The K-BIT is normed to have a mean of 100 and a standard deviation of 15. IQ scores that fall one or more standard deviations below the mean are considered clinically significant.

Maltreatment characteristics were coded by caseworkers at wave 1. Based on their reading of the child's file, caseworkers indicated the most serious type of maltreatment the child experienced (physical abuse 24%, sexual abuse 8%, emotional abuse 5%, neglect 53%, other abuse 10%), the number of types of maltreatment (range = 1-8; M = 1.34, SD = .65), the harm to the child caused by the maltreatment (1=none to 4=severe; M = 2.26, SD = 1.06), the level of risk (1=none to 4=severe; M = 2.51, SD = 1.06), the sufficiency of evidence for the case (0=no evidence of maltreatment to 5=clearly sufficient; M = 3.54, SD = 1.65), and whether the abuse was substantiated (58% substantiated).

Family and neighborhood characteristics were reported by permanent caregivers at wave 1. Diagnoses of major depressive disorder (28% with diagnosis), alcohol dependence (3% with diagnosis) and drug dependence (4% with diagnosis) were based on the Composite International Diagnostic Interview-Short Form (Kessler, Andrews, Mroczek, Ustun, & Wittchen, 1998), which asked about Diagnostic and Statistical Manual IV (American Psychiatric Association, 1994) symptoms of these disorders in the past 12 months. Permanent caregivers were also asked if they had ever been arrested (27% with arrests). Caregivers reported violent domestic assault using the Revised Conflict Tactics Scale 2 (Straus, Hamby, Boney-McCoy, & Sugarman, 1996), which asked respondents how many times their partners engaged in 9 physically violent behaviors one or more times in the past 12 months. Responses were recoded to indicate whether caregivers had been the victims of any domestic violence in the past year (31% were victims). Information about caregiver mental health, domestic violence, and arrests was gathered using ACASI technology. Community environment was assessed with 9 items related to neighborhood problems (1 “not at all a problem” to 3 “a very big problem”) and neighborhood quality as compared to other neighborhoods (e.g., 1 “safer” to 3 “not as safe as most”). Responses were summed to generate a total community environment score (M = 13.56, SD = 4.01). Caregivers reported pre-tax income in the past year. Income was grouped into 11 bands from 1 (< $5,000 per year) to 11 (> $50,000 per year) (M = 5.31, SD = 3.22). Caregivers reported their highest educational qualification. Responses were recoded into 5 groups: 0 “no degree”, 1 “high school degree”, 2 “some tertiary qualifications”, 3 “tertiary qualifications”, 4 “post-graduate qualifications” (M = 1.00, SD = .85).

Social services

A dichotomous variable indicated whether children or their families were receiving services paid for by CPS at the time of data file compilation, based on caseworker report (30% receiving services). Conclusions about rates of service utilization cannot be drawn from this study because children receiving services were over-sampled. Furthermore, information on children's non-CPS service receipt and receipt of services over the entire time span of the study was not available.

Analytic approach

The goal was to assess cognitive and behavioral outcomes as close in time as possible to the most recent report of maltreatment. The lag between the child's age at outcome and age at most recent report depended on (a) how close in time to a data collection wave the report was made to CPS and (b) the child's age when the most recent report was made. For example, children who were younger than two years when the most recent report was made had a longer lag than older children before outcome was assessed because none of the behavioral or IQ measures were administered to children under 2 years. Thus, although outcomes were assessed 21.11 months (SD = 18.44), on average, following the most recent maltreatment episode, there was substantial variability around this mean. Time elapsed from the child's age in months at the most recent maltreatment report to age at outcome was included as a covariate in analyses.

Because outcome was assessed as close in time as possible to the most recent report date there was also substantial variability in youth age at outcome, ranging from 24 months to 16 years. Effects of age differences were minimized by the use of standardized scores on cognitive and behavioral measures, but age at outcome was also included as a covariate in analyses of externalizing and prosocial behavior because it was significantly correlated with chronicity and children who were older when these behaviors were measured had higher scores. We note that the correlations between age at outcome and externalizing and prosocial behavior were small (r = .12 and .10, respectively).

We first conducted ordinary least squares (OLS) regression analyses in which the behavioral and IQ measures were regressed (in separate models) on maltreatment chronicity (making situational maltreatment the reference category) and the developmental period in which maltreatment first occurred (before 18 months, 18 to 36 months, 3 to 6 years, 6 to 9 years). We next tested whether developmental period moderated chronicity effects. We then tested whether chronic maltreatment was associated with characteristics of the child's abuse, family, or neighborhood. Finally, we conducted hierarchical OLS regression models to test whether abuse, family, or neighborhood characteristics accounted for the association between chronicity and outcome.

Results

Are Chronicity and Developmental Period Related to Later Behavior and IQ?

As shown in Table 1, OLS regression revealed that children who experienced any chronic maltreatment had significantly more externalizing problems than children who experienced situational maltreatment. Most chronically maltreated groups also had more internalizing problems and lower IQ scores than children who experienced situational maltreatment. There were no effects of chronicity on prosocial behavior, and no effects of developmental period on any of the outcome measures. Effect sizes for statistically significant group differences were small to moderate, ranging from d = .13 to d = .40.

Table 1.

OLS Regression of IQ and Behavioral Outcomes on Chronicity and Developmental Period

| Externalizing | Internalizing | Prosocial | IQ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| b (SE) | β | b (SE) | β | b (SE) | β | b (SE) | β | |

| Chronic | ||||||||

| Situational | – | – | – | – | ||||

| Lim/Discont | 3.42 (1.71) | .11* | .58 (.81) | .02 | 2.44 (2.54) | .06 | -3.67 (1.39) | -.09** |

| Lim/Cont | 2.32 (1.01) | .07* | 1.91 (.76) | .07* | -1.74 (1.45) | -.04 | -2.18 (1.13) | -.05 |

| Ext/Cont | 3.83 (1.82) | .11* | 2.01 (.89) | .06* | 2.13 (2.70) | .04 | -6.81 (1.46) | -.16*** |

| Dev Period | .54 (.75) | .06 | -.09 (.22) | -.01 | 1.91 (1.09) | .14 | .26 (.40) | .02 |

| Recency | -.04 (.03) | -.06 | -.06 (.02) | .10** | .11 (.04) | .12* | -.06 (.02) | -.11** |

| Constant | 52.31 (.67) | 52.25 (.63) | 87.56 (1.13) | 97.19 (1.41) | ||||

p < .05;

p<.01;

p<.001

We estimated the remaining pairwise comparisons among chronicity groups. Significant group differences on externalizing and internalizing scores were restricted to comparisons with the situationally maltreated group. Children who experienced limited/discontinuous maltreatment had higher prosocial behavior scores than children who experienced limited/continuous maltreatment (b = 4.18, SE = 2.03, p < .05), but no other differences were significant. For IQ, there was some evidence of a dose-response relationship such that children who experienced limited maltreatment (regardless of continuity) had significantly higher IQ scores than children who experienced extensive maltreatment (limited/discontinuous: b = 3.14, SE = 1.42, p < .05; limited/continuous: b = 4.63, SE = 1.63, p < .05).

Do Chronicity Effects Depend on the Developmental Period When Maltreatment Began?

OLS regression analyses were conducted to test whether developmental period moderated chronicity effects. Given that chronicity effects largely involved comparisons with the situationally maltreated group, the chronicity variable was dichotomized to reflect situational versus non-situational maltreatment.

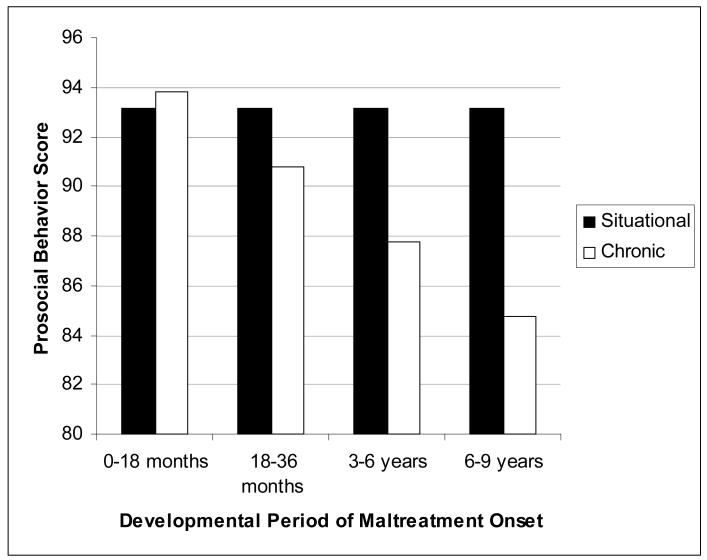

The chronicity × developmental period interaction was not significant for externalizing or internalizing behavior or IQ (externalizing: b = .13, SE = .50, p = .79; internalizing: b = .56, SE = .45, p = .21; IQ: b = -.60, SE = .72, p = .40), but it was significant for prosocial behavior (b = -3.03, SE = .75, p < .001). As shown in Figure 1, the biggest differences between chronically versus situationally maltreated children occurred when maltreatment first occurred at early school age (i.e., 6 to 9 years).

Figure 1.

The effect of maltreatment chronicity on prosocial behavior is moderated by the developmental period when maltreatment first occurred.

Is Maltreatment Chronicity Associated with Maltreatment or Family Characteristics or Social Services Receipt?

Ordinary least squares (OLS) and logistic regression analyses were conducted to determine whether maltreatment chronicity was associated with other characteristics of the child's first maltreatment experience, family characteristics at wave 1, and social services receipt (Table 2). Because children who experienced situational maltreatment tended to have the best behavioral and cognitive outcomes, they were made the reference category.

Table 2.

Differences in Abuse, Family, and Neighborhood Characteristics between Chronically versus Situationally Maltreated Children

| Situational (0) | Chronic (1) | 1 vs. 0 | |

|---|---|---|---|

| M (SD) or % (n) | M (SD) or % (n) | b (SE) β or OR (95% confidence interval) | |

| Number of Types of Maltreatment | 1.36 (.68) | 1.31 (.61) | -.05 (.03) -.04 |

| Most Serious Type of Maltreatment | |||

| Physical | 24% (242) | 23% (176) | .93 (.75 to 1.16) |

| Sexual | 8% (80) | 8% (60) | .98 (.69 to 1.38) |

| Emotional | 5% (48) | 6% (45) | 1.24 (.81 to 1.88) |

| Neglect | 52% (517) | 54% (409) | 1.07 (.88 to 1.29) |

| Other | 10% (102) | 9% (69) | .87 (.63 to 1.20) |

| Level of harm to child | 2.29 (1.08) | 2.23 (1.02) | -.06 (.05) -.03 |

| Level of risk to child | 2.55 (1.08) | 2.45 (1.02) | -.10 (.05) -.05 |

| Level of evidence | 3.52 (1.66) | 3.58 (1.64) | .06 (.08) .02 |

| Substantiated | 57% (571) | 59% (453) | 1.02 (.86 to 1.20) |

| Caregiver depression diagnosis | 24% (183) | 32% (206) | 1.51 (1.19 to 1.91)** |

| Caregiver alcohol dependence diagnosis | 2% (12) | 4% (26) | 2.65 (1.33 to 5.30)** |

| Caregiver drug dependence diagnosis | 3% (24) | 6% (36) | 1.83 (1.08 to 3.10)* |

| Caregiver ever arrested | 23% (175) | 31% (201) | 1.53 (1.21 to 1.94)*** |

| Domestic violent assault | 25% (182) | 39% (234) | 1.86 (1.47 to 2.36)*** |

| Caregiver highest education | 1.06 (.88) | .93 (.81) | -.13 (.04) -.08** |

| Annual income | 5.54 (3.25) | 5.02 (3.16) | -.52 (.16) -.08** |

| Dangerous community environment | 13.08 (3.79) | 14.19 (4.20) | 1.10 (.19) .14*** |

| Services Received? | 32% (320) | 29% (221) | 1.07 (.89 to 1.27) |

p < .001;

p<.01;

p<.05

Note: Other maltreatment included abandonment, legal/moral maltreatment, educational maltreatment, exploitation, and “other.” Annual income of 5 corresponds to $20,000-$24,999. Educational qualification of 1 corresponds to a high school degree.

As shown in Table 2, groups mainly differed with respect to family characteristics. Compared with children who experienced situational maltreatment, those who experienced chronic maltreatment were more likely to have a caregiver with a diagnosis of depression, alcohol or drug dependence, an arrest record, or who reported domestic violent assault. The caregivers of chronically maltreated children had lower levels of education, their families had lower incomes, and they lived in more dangerous neighborhoods compared with situationally maltreated children.

Do Maltreatment or Family Characteristics or Social Services Receipt Confound the Relationship between Chronicity and Cognitive or Behavioral Outcomes?

Using OLS regression analysis, we tested whether the effect of chronic versus situational maltreatment remained significant, controlling for maltreatment characteristics, family characteristics, or social services receipt, age at maltreatment onset, and time elapsed from the most recent maltreatment report to age at outcome (Appendix Table 1). Consistent with findings reported above, chronic maltreatment was associated with IQ (b = -4.06, SE = 1.25, p < .01), but not prosocial behavior (b = -.97, SE = 1.94, ns). However, the effect of chronic maltreatment on externalizing (b = 1.96, SE = 1.36, ns) and internalizing problems (b = 1.31, SE = .75, ns) was no longer significant, with the covariates accounting for 13% to 14% of the variance in outcome. Caregiver depression, arrest record, and living in a dangerous neighborhood predicted children's externalizing problems and caregiver depression and low levels of education predicted children's internalizing problems, suggesting that these factors potentially accounted for chronicity effects on problem behaviors.

Discussion

Using data from a large, national sample of children involved with CPS, we tested a series of hypotheses about the effects of maltreatment chronicity and age-at-onset on children's behavior and IQ scores. To our knowledge, this is the first study to test whether familial transmission of risk for problem behaviors and low IQ accounted for chronicity effects on children's outcomes.

Consistent with our first hypothesis, chronically maltreated children had more externalizing and internalizing problems and lower IQ scores than situationally maltreated children, although group differences were small. For externalizing problems, the proportion of situationally versus chronically maltreated children who exceeded clinical cut-offs were 13% and 25%, respectively. For internalizing problems, the percentages were 12% versus 18% and for IQ the percentages were 21% versus 27%. Differences between children who experienced situational maltreatment versus extensive/continuous maltreatment were greater, with 20% to 34% of the latter group exceeding clinical cut-offs. These statistics establish that chronically maltreated children were at risk for clinically-significant problems in both a relative sense (compared with published norms) as well as an absolute sense (i.e., a significant minority of chronically maltreated children scored within the clinical risk range). Although NSCAW lacks a non-maltreated comparison group, other well-designed studies have firmly established that maltreated children have poorer outcomes compared with demographically matched controls (e.g., Bolger et al., 1998; Manly et al., 2001; Widom, 1989) and NSCAW would be unlikely to show anything different.

In general, we were unable to distinguish among chronically maltreated children who varied in the extent and continuity of their maltreatment and we ultimately pooled these groups in comparisons with situationally-maltreated children. Failure to detect differences among chronically maltreated children could have resulted from misclassification error in our attempts to time maltreatment recurrence in NSCAW. The only other study to define chronicity in terms of continuity and extent (English et al., 2005) did not explicitly compare chronically maltreated groups, but rather treated chronicity as a continuous variable, with situational maltreatment reflecting low levels of chronicity and extensive/continuous maltreatment reflecting high levels of chronicity. Thus, it remains an open question whether identifying subgroups of chronically maltreated children on the basis of extent and continuity will account for significant variation in child outcome.

Contrary to our second hypothesis, maltreatment chronicity was not more strongly associated with child outcomes if maltreatment began in infancy versus later in development. We detected only one interaction between chronicity and developmental period and it revealed that differences between chronically versus situationally maltreated children in prosocial behavior became more – not less – pronounced as the age at which children were first maltreated increased. It is possible that prosocial behavior is worst affected if maltreatment begins as children transition to school and peer relations take on increasing importance, but the finding requires replication. We note, however, that at least one other group also observed that chronicity effects (on externalizing problems) were greater when maltreatment originated in the preschool rather than the infancy period (Manly et al., 2001). We also note that power to detect interactions may have been low. However, alternative approaches, involving estimation of chronicity effects on outcome in each developmental period, also failed to support our second hypothesis. That is, there was no evidence for any outcome that effects of maltreatment chronicity on outcome were greater in the infancy period than at later developmental periods.

We found partial support for our third hypothesis: chronically maltreated children came from more disadvantaged environments than situationally maltreated children, but the groups did not differ with respect to characteristics of their maltreatment nor with respect to whether they were receiving services. We also found partial support for our fourth hypothesis: differences between chronically and situationally maltreated children on externalizing and internalizing problems were reduced to non-significance by the inclusion of family and neighborhood characteristics in our models. Specifically, caregiver depression, arrest history, educational qualifications, and neighborhood danger were associated with both chronicity and children's problem behaviors. The findings suggest that chronically maltreated children may have elevated externalizing and internalizing problems because there is intergenerational transmission of risk for these problems which may be mediated genetically or via the family environment. To our knowledge, no other studies of maltreatment chronicity have data on caregiver mental health, substance use, and antisocial behavior and ours is the first to identify this alternative explanation for chronicity effects on children's problem behaviors.

In contrast, although the caregivers of chronically versus situationally maltreated children had lower levels of education and low levels of caregiver education were associated with low child IQ scores, chronic maltreatment had a unique effect on children's IQ scores. The existing literature provides several reasons why chronic maltreatment may be associated with poor cognitive outcomes, including the effects of chronic stress on brain development (Lupien, McEwen, Gunnar, & Heim, 2009), sub-nutrition associated with neglect (Sonuga-Barke et al., 2008), and inadequate language exchanges between maltreating caregivers and children (Cicchetti & Valentino, 2006).

Implications for Practice and Policy

Our findings are consistent with the literature showing that children who are chronically maltreated come from families characterized by parent substance use problems, domestic violence, and family socioeconomic disadvantage (as reviewed by Fluke, Shusterman, Hollinshead, & Yuan, 2008), characteristics which are also associated with failure to engage with interventions (Littell & Tajima, 2000). Combined with the fact that there is little evidence regarding the efficacy of programs to prevent maltreatment recurrence (MacMillan et al., 2009), children may benefit more from programs designed to prevent maltreatment onset. There is modest success in identifying effective programs to prevent maltreatment, child injury, and health problems such as the Nurse Family Partnership, Early Start, and Early Head Start (Howard & Brooks-Gunn, 2009; MacMillan et al., 2009) and some evidence that intervention effects are strongest among first-time parents who are at the highest risk based on poverty, depression, and lack of resources (Howard & Brooks-Gunn, 2009).

Moreover, the findings with respect to child problem behaviors highlight the importance of providing mental health services to caregivers of maltreated children and reducing caregiver involvement in antisocial behavior. There is evidence that the effects of these characteristics on children are environmentally as well as genetically mediated (Jaffee, Moffitt, Caspi, & Taylor, 2003; Kim-Cohen, Caspi, Rutter, Polo Tomas, & Moffitt, 2006) and that treatment of parental mental health problems is associated with reductions in symptoms of child psychopathology (Weissman et al., 2006). However, anywhere from a third to nearly three-quarters of caregivers involved with child welfare services do not receive the alcohol, drug, or mental health services they need (Libby et al., 2006; Staudt & Cherry, 2009).

Limitations

First, although there were no documented reports of maltreatment prior to wave 1, some children might have experienced earlier unreported abuse or neglect. Similarly, some of the children classified as having experienced situational maltreatment may have experienced subsequent maltreatment that was not detected by caseworkers or reported by caregivers. Indeed, although the CTS-PC has good specificity (i.e., fails to classify non-maltreaters as maltreaters) it has low sensitivity (i.e., will fail to pick up many people with histories of maltreatment) (Bennett, Sullivan, & Lewis, 2006). Moreover, ACASI technology has not been shown to increase reporting of sensitive information (Tourangeau & Yan, 2007), so caregivers may have under-reported abusive or neglectful care of children. Finally, consistent with English et al. (2005), we identified children as having been maltreated in a given developmental period if they experienced any maltreatment in that period. This means that children who were maltreated in the infancy period, for example, could have varied in terms of how many instances of maltreatment they experienced, but the data did not allow us to account for this within-period variability. These kinds of classification errors and within-group heterogeneity should have exerted a conservative effect on the findings by making it more difficult to detect differences between groups

Second, the sample included children with substantiated and unsubstantiated reports of maltreatment. Although this makes the sample more representative of maltreated children in the population, many of whom do not come to the attention of CPS, we cannot be certain that all children experienced maltreatment.

Third, although the full NSCAW sample is a national probability sample, our focus on children 9 years or younger at baseline limits the generalizability of our findings because it was not appropriate to apply sampling weights to this sub-group.

Fourth, caregiver reports of child behavior could have been biased, particularly if caregivers were implicated in the child's maltreatment. Supplemental analyses of children who had both parent and teacher reports of behavior showed that, on average, teachers identified more externalizing problems than parents, but equal numbers of internalizing problems and more prosocial behaviors so it is not clear what the direction of bias could have been.

Fifth, at least two additional factors could have accounted for chronicity effects on child outcome. One is that chronically maltreated children were more likely to be removed from the care of biological parents and that multiple transitions in foster care partly explained their relatively poor outcomes (Rubin, O'Reilly, Luan, & Localio, 2007). Another was that, even though situationally and chronically maltreated children were equally likely to receive services, chronically maltreated children may have received fewer services than they actually needed.

The study also possessed a number of strengths, including the large sample size, the ability to measure age-of-maltreatment-onset in a prospective design, statistical controls for maltreatment recency effects, and rich data on caregiver characteristics that allowed us to test whether chronic maltreatment is simply a marker for familial risk for problem behaviors and low IQ. Our findings point to the need for evidenced-based, multi-systemic interventions to reduce rates of maltreatment recurrence.

Key Points.

Chronically maltreated children have more cognitive and behavioral problems than children whose maltreatment is restricted to a single developmental period.

Maltreatment chronicity is associated with poor child outcome regardless of the child's age when the maltreatment began.

The adverse effects of chronic maltreatment are partly due to the fact that chronically maltreated children are likely to have caregivers who are depressed and involved in antisocial behavior.

More mental health and substance use services are needed for caregivers involved with child welfare services.

Acknowledgments

Our thanks to Michael Rutter and Barbara Maughan for comments on this manuscript. This work was supported by HD050691 from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. This document includes data from the National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being, which was developed under contract with the Administration on Children, Youth, and Families, US Department of Health and Human Services (ACYF/DHHS). The data have been provided by the National Data Archive on Child Abuse and Neglect. The information and opinions expressed herein reflect solely the position of the authors. Nothing herein should be construed to indicate the support or endorsement of its content by ACYF/DHHS.

Appendix Table 1.

Effect of Chronic Maltreatment Controlling for Abuse, Family, and Neighborhood Characteristics

| Externalizing | Internalizing | Prosocial | IQ | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 1 | Model 2 | |

|

b (SE) β |

b (SE) β |

b (SE) β |

b (SE) β |

b (SE) β |

b (SE) β |

b (SE) β |

b (SE) β |

|

| Chronic | 2.28 (1.01) | 1.96 (1.36) | 1.51 (.56) | 1.31 (.75) | -1.89 (1.45) | -.97 (1.94) | -3.45 (.94) | -4.06 (1.25) |

| .10* | .09 | .07** | .06 | -.06 | -.09 | -.11*** | -.13** | |

| Developmental Period |

.04 (.56) | .41 (.75) | -.06 (.22) | .04 (.31) | .34 (.78) | .21 (1.05) | .51 (.38) | .47 (.51) |

| .00 | .04 | -.01 | .00 | .03 | .02 | .04 | .04 | |

| Recency | -.07 (.02) | -.04 (.03) | -.06 (.02) | -.06 (.02) | .04 (.03) | .03 (.04) | -.04 (.02) | -.04 (.03) |

| -.09** | -.06 | -.09** | -.09** | .05 | .03 | -.06 | -.06 | |

| Number of Types of Maltreatment |

.45 (.71) | .48 (.68) | .88 (1.03) | 1.22 (1.01) | ||||

| .02 | .02 | .03 | .04 | |||||

| Most Serious Type of Maltreatment |

||||||||

| Physical | – | – | – | – | ||||

| Sexual | -2.10 (1.47) | -.09 (1.41) | -.08 (2.15) | 1.17 (2.10) | ||||

| -.05 | .00 | .00 | .02 | |||||

| Emotional | -1.60 (1.80) | .33 (1.72) | -4.03 (2.61) | 1.63 (2.58) | ||||

| -.03 | .01 | -.06 | .02 | |||||

| Neglect | -1.27 (.93) | -.84 (.89) | -.95 (1.36) | .10 (1.33) | ||||

| -.06 | -.04 | -.03 | .00 | |||||

| Other | -4.21 (1.56) | -2.93 (1.49) | -.23 (2.28) | -.17 (2.29) | ||||

| -.10** | -.07 | .00 | .00 | |||||

| Level of harm to child |

-.07 (.54) | .36 (.52) | -.02 (.79) | -.32 (.78) | ||||

| -.01 | .03 | .00 | -.02 | |||||

| Level of risk to child |

1.06 (.56) | 1.02 (.54) | -1.56 (.82) | -1.15 (.82) | ||||

| .09 | .09 | -.10 | -.07 | |||||

| Level of evidence | -.48 (.37) | -.81 (.35) | .39 (.53) | .16 (.52) | ||||

| -.07 | -.13* | .04 | .02 | |||||

| Substantiated | -.29 (1.14) | 1.28 (1.08) | -.58 (1.66) | 2.09 (1.62) | ||||

| -.01 | .06 | -.02 | .07 | |||||

| Caregiver depression diagnosis |

3.13 (.85) | 2.94 (.82) | -1.12 (1.25) | 1.45 (1.22) | ||||

| .13*** | .12*** | -.03 | .04 | |||||

| Caregiver alcohol dependence |

3.17 (2.46) | 2.94 (2.35) | -5.17 (3.57) | 2.99 (3.46) | ||||

| .05 | .05 | -.05 | .03 | |||||

| Caregiver drug dependence diagnosis |

-4.20 (1.90) | -3.77 (1.81) | 4.65 (2.75) | .93 (2.77) | ||||

| -.08* | -.08* | .06 | .01 | |||||

| Caregiver ever arrested |

2.06 (.86) | .40 (.82) | 2.41 (1.25) | 1.71 (1.23) | ||||

| .08* | .02 | .07 | .05 | |||||

| Domestic violent assault |

.03 (.85) | .02 (.82) | .49 (1.24) | .72 (1.23) | ||||

| .00 | .00 | .01 | .02 | |||||

| Caregiver education | -.78 (.50) | -1.59 (.47) | 1.63 (.72) | 2.53 (.71) | ||||

| -.05 | -.12** | .08* | .13*** | |||||

| Annual income | .23 (.13) | .24 (.13) | .15 (.19) | .62 (.19) | ||||

| .06 | .06 | .03 | .12** | |||||

| Dangerous community environment |

.29 (.09) | .12 (.09) | -.28 (.13) | -.20 (.13) | ||||

| .11** | .05 | -.10** | -.05 | |||||

| Services Received? | -.67 (.83) | .22 (.79) | .33 (1.21) | 1.37 (1.19) | ||||

| -.03 | .01 | .01 | .04 | |||||

| R2 | 3.5% | 8.3% | 1.6% | 7.5% | 1.9% | 5.8% | 1.4% | 8.4% |

p < .001;

p<.01;

p<.05

Contributor Information

Sara R. Jaffee, Institute of Psychiatry, King's College London.

Andrea Kohn Maikovich-Fong, University of Pennsylvania.

Reference List

- Achenbach TM. Manual for the Child Behavior Checklist/4-18 and 1991 profile. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Department of Psychiatry; 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Achenbach TM, Rescorla LA. Manual for the ASEBA School-Age Forms & Profiles. Burlington, VT: University of Vermont Research Center for Children, Youth, and Families; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual. 4th. Washington DC: Authors; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Arnow BA. Relationships between childhood maltreatment, adult health and psychiatric outcome, and medical utilization. Journal of Clinical Psychiatry. 2004;65:10–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett DS, Sullivan MW, Lewis M. Relations of parental report and observation of parenting to maltreatment history. Child Maltreatment. 2006;11:63–75. doi: 10.1177/1077559505283589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolger KE, Patterson CJ, Kupersmidt JB. Peer relationships and self-esteem among children who have been maltreated. Child Development. 1998;69:1171–1197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Valentino K. An ecological-transactional perspective on child maltreatment. In: Cicchetti D, Cohen DJ, editors. Developmental psychopathology (2nd edition): Vol 3 Risk, disorder, and adaptation. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons, Inc.; 2006. pp. 129–201. [Google Scholar]

- Cicchetti D, Toth SL. A developmental psychopathology perspective on child abuse and neglect. Journal of the American Academy of Child Psychiatry. 1995;34:541–565. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199505000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowd K, Kinsey S, Wheeless S, Thissen R, Richardson J, Suresh R, et al. National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being (NSCAW): Combined Waves 1-4 Data User's Manual. Durham, NC: Research Triangle Institute; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Drake B. Unraveling “unsubstantiated”. Child Maltreatment. 1996;1:261–271. [Google Scholar]

- Drake B, Jonson-Reid M, Way I, Chung S. Substantiation and recidivism. Child Maltreatment. 2003;8:248–260. doi: 10.1177/1077559503258930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- English DJ, Marshall DB, Coghlan L, Brummel S, Orme M. Causes and consequences of the substantiation decision in Washington state child protective services. Children and Youth Services Review. 2002;24:817–851. [Google Scholar]

- English DJ, Graham JC, Litrownik AJ, Everson M, Bangdiwala SI. Defining maltreatment chronicity: Are there differences in child outcomes? Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29:575–595. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.08.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erikson E. Childhood and Society. 2nd. New York: Norton; 1963. [Google Scholar]

- Éthier LS, Lemelin JP, Lacharité C. A longitudinal study of the effects of chronic maltreatment on children's behavioral and emotional problems. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2004;28:1265–1278. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fluke JD, Shusterman GR, Hollinshead DM, Yuan YYT. Longitudinal analysis of repeated child abuse reporting and victimization: Multistate analysis of associated factors. Child Maltreatment. 2008;13:88. doi: 10.1177/1077559507311517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fuller T, Nieto M. Substantiation and maltreatment rereporting: A propensity score analysis. Child Maltreatment. 2009;14:27–37. doi: 10.1177/1077559508326925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gresham FM, Elliot SN. SSRS: Social Skills Rating System. Circle Pines, MN: AGS; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Hindley N, Ramchandani PG, Jones DPH. Risk factors for recurrence of maltreatment: A systematic review. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 2006;91:744–752. doi: 10.1136/adc.2005.085639. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard KS, Brooks-Gunn J. The role of home-visiting programs in preventing child abuse and neglect. Future of Children. 2009;19:119–146. doi: 10.1353/foc.0.0032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussey JM, Marshall JM, English DJ, Knight ED, Lau AS, Dubowitz H, et al. Defining maltreatment according to substantiation: Distinction without a difference? Child Abuse & Neglect. 2005;29:479–492. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2003.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffee SR, Caspi A, Moffitt TE, Taylor A. Physical maltreatment victim to antisocial child: Evidence of an environmentally mediated process. Journal of Abnormal Psychology. 2004;113:44–55. doi: 10.1037/0021-843X.113.1.44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffee SR, Gallop R. Social, emotional, and academic competence among children who have had contact with Child Protective Services: Prevalence and stability estimates. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46:757–765. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e318040b247. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaffee SR, Moffitt TE, Caspi A, Taylor A. Life with (and without) father: The benefits of living with two biological parents depend on the father's antisocial behavior. Child Development. 2003;74:109–126. doi: 10.1111/1467-8624.t01-1-00524. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler RC, Andrews G, Mroczek D, Ustun TB, Wittchen HU. The World Health Organization Composite International Diagnostic Interview Short Form (CIDI-SF) International Journal of Methods in Psychiatric Research. 1998;7:171–185. doi: 10.1002/mpr.168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim-Cohen J, Caspi A, Rutter M, Polo Tomas M, Moffitt TE. The caregiving environments provided to children by depressed mothers with or without an antisocial history. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2006;163:1009–1018. doi: 10.1176/ajp.2006.163.6.1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kohl PL, Johnson-Reid M, Drake B. Time to leave substantiation behind: Findings from a national probability study. Child Maltreatment. 2009;14:17–26. doi: 10.1177/1077559508326030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libby AM, Orton HD, Barth RP, Webb MB, Bruce BJ, Wood P, et al. Alcohol, drug, and mental health specialty treatment services and race/ethnicity: A national study of children and families involved with child welfare. American Journal of Public Health. 2006;96:628–631. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.059436. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Littell JH, Tajima EA. A multilevel model of client participation in intensive family preservation services. Social Service Review. 2000;74:405–435. [Google Scholar]

- Lupien SJ, McEwen BS, Gunnar MR, Heim C. Effects of stress across the lifespan on the brain, behaviour and cognition. Nature Review Neuroscience. 2009;10:434–445. doi: 10.1038/nrn2639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacMillan HL, Wathen CN, Barlow J, Fergusson DM, Leventhal JM, Taussig HN. Interventions to prevent child maltreatment and associated impairment. Lancet. 2009;373:250–266. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61708-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maikovich AK, Koenen KC, Jaffee SR. Posttraumatic stress symptoms and trajectories in child sexual abuse victims: An analysis of sex differences using the National Survey of Child and Adolescent Well-Being. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2009;37:727–737. doi: 10.1007/s10802-009-9300-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manly JT, Cicchetti D, Barnett D. The impact of subtype, frequency, severity, and chronicity of child maltreatment on social competence and behavior problems. Development and Psychopathology. 1994;6:121–143. [Google Scholar]

- Manly JT, Kim JE, Rogosch FA, Cicchetti D. Dimensions of child maltreatment and children's adjustment: Contributions of developmental timing and subtype. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:759–782. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubin DM, O'Reilly A, Luan X, Localio AR. The impact of placement stability on behavioral well-being for children in foster care. Pediatrics. 2007;119:336–344. doi: 10.1542/peds.2006-1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sonuga-Barke EJS, Beckett C, Kreppner J, Castle J, Colvert E, Stevens S, et al. Is sub-nutrition necessary for a poor outcome following early institutional deprivation? Developmental Medicine and Child Neurology. 2008;50:664–671. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8749.2008.03065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sroufe LA, Rutter M. The domain of developmental psychopathology. Child Development. 1984;55:17–29. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staudt M, Cherry D. Mental health and substance use problems of parents of involved with child welfare: Are services offered and provided? Psychiatric Services. 2009;60:56–60. doi: 10.1176/ps.2009.60.1.156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart A, Livingston M, Dennison S. Transitions and turning points: Examining the links between child maltreatment and juvenile offending. Child Abuse & Neglect. 2008;32:66. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2007.04.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby S, Finkelhor D, Moore D, Runyan D. Identification of child maltreatment with the Parent-Child Conflict Tactics Scales: Development and psychometric data for a national sample of American parents. Child Abuse & Neglect. 1998;22:249–270. doi: 10.1016/s0145-2134(97)00174-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Straus MA, Hamby SL, Boney-McCoy S, Sugarman DB. The Revised Conflict Tactics Scales (CTS2): Development and preliminary psychometric data. Journal of Family Issues. 1996;17:283–316. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson R, Wiley TR. Predictors of re-referral to child protective services: A longitudinal follow-up of an urban cohort maltreated as infants. Child Maltreatment. 2009;14:89–99. doi: 10.1177/1077559508325317. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thornberry TP, Ireland TO, Smith CA. The importance of timing: The varying impact of childhood and adolescent maltreatment on multiple problem outcomes. Development and Psychopathology. 2001;13:957–979. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tourangeau R, Yan T. Sensitive questions in surveys. Psychological Bulletin. 2007;133:859–883. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.133.5.859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trickett PK, McBride-Change C. The developmental impact of different forms of child abuse and neglect. Developmental Review. 1995;15:311–337. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, A.C. Y. F. Child Maltreatment 2006. Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Weissman MM, Pilowsky DJ, Wickramaratne PJ, Talati A, Wisniewski SR, Fava M, et al. Remissions in maternal depression and child psychopathology: A STAR*D-Child Report. JAMA. 2006;295:1389–1398. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.12.1389. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Widom CS. The cycle of violence. Science. 1989;244:160–166. doi: 10.1126/science.2704995. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]