Abstract

Toxoplasma IgG and IgA, but not IgM, antibody titers were significantly higher in immunocompetent mice with cerebral proliferation of tachyzoites during the chronic stage of infection than those treated with sulfadiazine to inhibit the parasite growth. Their IgG and IgA antibody titers correlated significantly with the amounts of tachyzoite-specific SAG1 mRNA in their brains. In contrast, neither IgG, IgA, nor IgM antibody titers increased following two different doses of challenge infection in chronically infected mice. Increased antibody titers in IgG and IgA but not IgM may be a useful indicator suggesting an occurrence of cerebral tachyzoite growth in immunocompetent individuals chronically infected with T. gondii.

Keywords: Toxoplasma gondii, IgG, IgA, IgM, Cerebral toxoplasmosis, Schizophrenia, Epilepsy

1. Introduction

After proliferation of tachyzoites in a variety of cells throughout the body during the acute stage of infection with Toxoplasma gondii, the parasite establishes chronic infection by forming tissue cysts primarily in the brain. It is estimated that 500 million to 2 billion people worldwide are chronically infected with this parasite [1, 2]. Despite the fact that such a large number of people are infected and most likely harbor T. gondii cysts in their brains [3], clinical importance of this chronic infection remains largely unexplored and therefore unappreciated.

Recent studies demonstrated increased Toxoplamsa IgG, but not IgM, antibody levels in sera of patients with the early onset of schizophrenia [4, 5]. These schizophrenia patients do not appear to be in the acute stage of acquired infection with T. gondii since both IgM and IgG antibody titers increase during this stage of infection [6]. Therefore, the patients appear to be in a specific condition of chronic infection that causes an increase only in IgG antibody titers. A correlation between chronic T. gondii infection and cryptogenic epilepsy has also been reported [7], and Toxoplasma IgG antibody levels were greater in the patients than controls in this case as well [7].

One possible condition that causes an increase of only IgG antibody titers would be an occurrence of proliferation of tachyzoites during the chronic stage of infection. Another possible condition that causes an increase of only IgG antibody titers would be an occurrence of reinfection in chronically infected individuals. In order to examine whether either of these conditions causes an increase in IgG antibody titers but not in IgM antibody titers, we used murine models that represent each of these conditions and measured both Toxoplasma IgG and IgM antibody titers in their sera. One model was CBA/J mice that are susceptible to chronic infection with type II parasite and represent active proliferation of tachyzoites in their brains during the later stage of infection. Re-infection model was BALB/c mice that are resistant to the infection and establish a latent, chronic infection without detectable levels of tachyzoites in their brains. With the use of this strain of mice, we can focus on the effects of re-infection on antibody responses to the parasite. We measured the IgA antibody titers, in addition to IgG and IgM antibody titers, because the oral route is the natural route of infection with T. gondii, and IgA antibody is associated with the immune responses on mucosal surfaces including that of the intestine.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Mice

Female CBA/J and BALB/c mice were from the Jackson Laboratories (Bar Harbor, ME). Female Swiss-Webster mice were from Taconics (Germantown, NY). Mice were housed in a specific pathogen-free condition and 2-3 months old when used. Uninfected and acutely infected mice were older than 2-3 months when used, in order to be approximately age-matched with chronically infected animals. There were 5-12 mice in each experimental group.

2.2. Animal model of tachyzoite proliferation in the brain during the chronic stage of infection

CBA/J mice were infected with 10 cysts of the ME49 strain (type II strain) orally by gavage [8]. Cysts were obtained from the brains of chronically infected Swiss-Webster mice [9]. CBA/J is one of strains susceptible to chronic infection with type II parasite and represents active proliferation of tachyzoites in their brains during the later stage of infection [10, 11]. Acute inflammatory changes are noted in the brain but not in the lungs, livers, spleens or kidneys of susceptible mice during the chronic stage of infection (two months after infection) [12]. One group of animals (n=8) received sulfadiazine (400 mg/L) in drinking water beginning at 3 weeks after infection for the entire period of the experiment to prevent proliferation of tachyzoites during the chronic stage of infection. Another group of mice (n=12) did not receive the treatment. Sera were obtained from the sulfadiazine-treated and untreated mice at two months (8-9 weeks) after infection.

2.3. Animal model of re-infection

BALB/c mice were infected orally with 10 cysts of the ME49 strain. BALB/c mice are genetically resistant to T. gondii infection and establish a latent, chronic infection [10, 11]. There are few inflammatory changes in their brains and tachyzoites are undetectable in this organ during the chronic stage of infection [10, 11]. No inflammatory changes are observed in the lungs, livers, spleens, and kidneys of these chronically infected mice [12]. With the use of this strain of mice, we can focus on the effects of re-infection on antibody responses to the parasite. Three months after the initial infection, the animals were divided into three groups. One group was challenged orally with 10 cysts of the same strain of the parasite, and another group was challenged with 50 cysts. The other group did not receive any challenge infection. Sera were obtained from each of these three groups weekly for 4 weeks after the challenge infection. At each time point, the blood was collected from the retro-orbital site under deep anesthesia with Isoflurane. After bleeding, the animals were euthanized by CO2 narcosis and their brains were obtained for confirming the absence of tachyzoites. The volume of serum obtained from each mouse was usually 0.2-0.3 ml. There were 4 or 5 mice in the group without challenge infection and 6-8 mice in each of the groups with challenge infection at each time point.

2.4. Enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) for detection of Toxoplasma IgG, IgM and IgA antibodies

Each well of microtiter plates (Nunc, Rochester, NY) was coated with 100 μl of tachyzoite lysate antigens of the ME49 strain [13] diluted in 0.05 M carbonate buffer (pH 9.6) at 10 μg/ml. After incubation at 4 °C overnight, the plates were washed three times with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS; pH7.2) containing 0.05% Tween 20 (PBS-T) and postcoated with 3% bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Sigma, St. Louis, MO) in PBS at 37 °C for 2 hr. The plates were then washed, and 100 μl of two-fold serial dilution of serum diluted 1: 100 in 1% BSA in PBS-T (BSA-PBS-T) was applied to each well. After incubation at 37 °C for 1 hr and washes, an appropriate dilution of peroxidase-labeled goat anti-mouse IgG, IgA or IgM antibodies (Invitrogen, Camarillo, CA) diluted in BSA-PBS-T were added and the plates were incubated at 37 °C for 1 hr. After washes and incubation with 100 μl of TMB solution (KPL, Gaithersburg, MD) at room temperature for 10 min, reaction was stopped by 100 μl of 2N H2SO4 solution and the OD450 values were measured. Antibody titer of each serum was determined by taking the highest dilution that provided a positive reading higher than the cut-off value. The cut-off value was determined by the mean value plus 2 SD of the reading with uninfected mouse sera (n=5) at a dilution of either 1:100 (IgG and IgA) or 1:400 (IgM).

2.5. Quantification of mRNA for tachyzoite-specific SAG1 in the brain

At 2 months after infection, RNA was isolated from brains of CBA/J mice with and without sulfadiazine treatment [8], and cDNA was synthesized using 1 μg of RNA after pre-treatment with DNase I (Invitrogen, Carlshad, CA) to remove genomic DNA contaminating the RNA preparations [14]. RNA was also isolated from the brains of BALB/c mice weekly for 4 weeks after challenge infection and applied for cDNA synthesis in the same manner. The amount of the RNA for the cDNA synthesis was determined by the value of OD260 of each RNA preparation. For quantifying tachyzoites in their brains, cDNA were applied for real-time PCR to measure the amounts of mRNA for tachyzoite-specific SAG1 using StepOne Plus thermalcycler (Applied Biosystems, Foster City, CA) and AmpliTaq Gold PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) using 40 cycles of 95°C for 15 sec and 60°C for 60 sec after denaturing at 95°C for 10 min. The sequences of the primers and probe were: GTT TCC GAA GGC AGT GAG AC (forward), AAG AGT GGG AGG CTC TGT GA (reverse), and 6FAM-AGT TGT CAC CTG CCC-MGB-NFQ (probe). In addition to the use of the specific probe, the size of PCR products from some of the reactions was verified to be of the expected size (226 bp). The quantification of mRNA was normalized to the β-actin level, which was measured using a commercial kit (Applied Biosystems).

2.6. Statistical analysis

Levels of significance for antibody titers between experimental groups were determined by Wilcoxon Rank Sum test. Levels of significance in correlation of antibody titers and the amounts of SAG1 mRNA in the brain were determined using Pearson correlation. Differences which provided P<0.05 were considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Toxoplasma antibody profile associated with proliferation of tachyzoites in the brain during the later stage of infection

3.1.1 IgG antibody

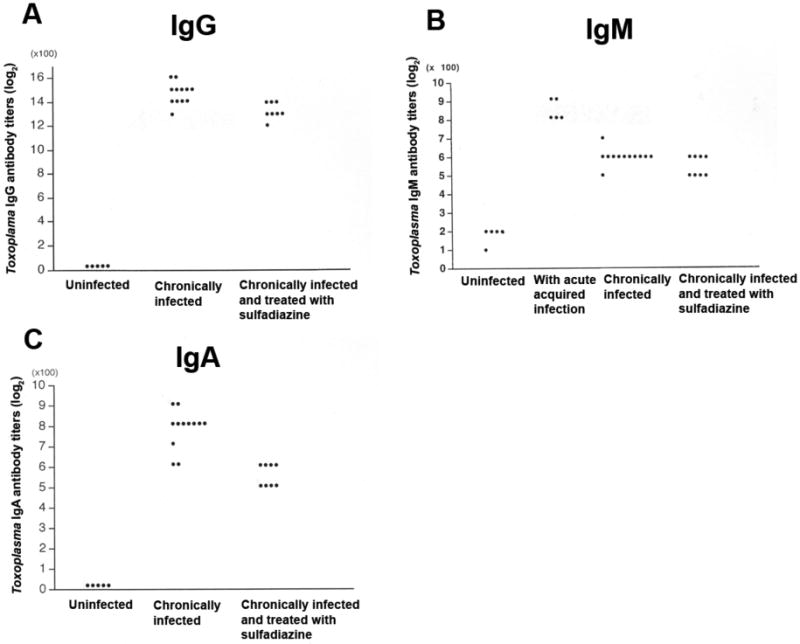

Two groups of CBA/J mice were infected and one group was treated with sulfadiazine beginning at 3 weeks after infection to inhibit proliferation of tachyzoites during the later stage of infection. Sera were obtained from the sulfadiazine-treated and -untreated mice at two months after infection. Significantly higher IgG antibody titers were detected in sera of the untreated group than in sera of the sulfadiazine-treated group (log2 antibody titers [×100]: 14.7 ± 0.89 [n=12] vs. 13.3 ± 0.71 [n=8]; P<0.01) (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Toxoplasma serological profile of mice that have proliferation of tachyzoites in the brain during the chronic stage of infection. CBA/J mice were infected with 10 cysts of the ME49 strain orally. One group of animals (n=8) received sulfadiazine beginning at 3 weeks after infection for the entire period of the experiment to inhibit proliferation of tachyzoites during the chronic stage of infection. Another group of mice (n=12) did not receive the treatment. Sera were obtained from the sulfadiazine-treated and untreated mice at two months after infection. Toxoplasma IgG, IgM, and IgA antibody titers in their sera were measured by ELISA (see the Materials and Methods). Each dot in the panel indicates an antibody titer of each individual mouse in the experimental group.

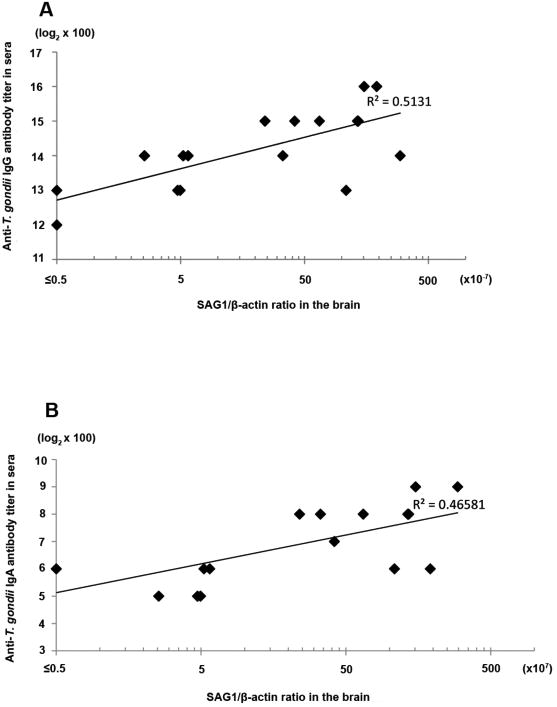

Markedly greater amounts of mRNA for tachyzoite-specific SAG1 were detected in untreated mice than in sulfadiazine-treated animals (SAG1/β-actin ratios [× 10-6]: 17.71 ±21.16 vs. 0.32 ± 0.25, P<0.0005). As a negative control SAG1 mRNA was not detectable in the brains of uninfected animals (n=4, data not shown). There was a significant correlation between the IgG antibody titers and the amounts of SAG1 mRNA in the brains of infected animals when excluding one untreated mouse that had an exceptionally high amount of SAG1 mRNA (6.5 times greater than the average of all other mice in the same group) (P<0.005) (Fig. 2A). A stronger correlation was observed with the use of log scale in SAG1 mRNA than with linear scale (R2=0.5131, P<0.005 for log scale vs. R2=0.23671, P<0.05 for linear scale), suggesting that IgG antibody levels efficiently increase with a small increase in tachyzoite number in the brain when the total tachyzoite numbers are low.

Fig. 2.

Correlation of Toxoplasma IgG (A) or IgA (B) antibody titers in sera and the amounts of mRNA for tachyzoite-specific SAG1 in the brain of chronically infected CBA/J mice with and without treatment with sulfadiazine.

3.1.2. IgM antibody

In contrast to IgG antibodies, the IgM antibody titers of infected and untreated mice did not differ from those of infected and sulfadiazine-treated animals (log2 antibody titers [×100]: 6.00 ± 0.43 [n=12] vs. 5.50 ± 0.53 [n=8]) (Fig. 1B). We included sera obtained from mice during the acute acquired stage of infection (2 weeks after infection) as a control in which increased IgM antibody titers should be detected. These acute sera showed significantly higher IgM antibody titers (8.40 ± 0.55 [n=5]) than either of the chronically infected groups (Fig. 2; P< 0.005).

3.1.3. IgA antibody

Toxoplasma IgA antibody titers were significantly higher in sera of infected and untreated mice than in sera of infected and sulfadiazine-treated animals (log2 antibody titers [×100]: 7.75 ± 0.97 [n=12] vs. 5.50 ± 0.53 [n=8]; P<0.005) (Fig. 1C). Of interest, the differences in the IgA antibody titers between these two groups were greater when compared to the differences in the IgG antibody titers in the same groups (P<0.05). There was a significant correlation between the IgA antibody titers and the amounts of SAG1 mRNA in the brain of animals (P<0.005) (Fig. 2B).

3.2. Toxoplasma antibody profile associated with re-infection with the parasite during the chronic stage of infection

3.2.1. IgG antibody

Three months after infection of BALB/c mice, the animals were divided into three groups. One group was challenged orally with 10 cysts and another group was challenged with 50 cysts. The other group did not receive any challenge infection. Sera were obtained from each of these three groups weekly for 4 weeks after the challenge infection. The IgG antibody titers did not differ among the groups of mice at any time point examined regardless of the presence or absence of challenge infection or the doses of challenge infection (Table 1).

Table 1.

Toxoplasma IgG antibody profile of chronically infected mice following re-infection with two different doses of the parasite

| Challenged witha | Toxoplasma IgG antibody titers in sera at weeks after challenge infection (log2 × 100) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 week | 2 weeks | 3 weeks | 4 weeks | |

| None | 11, 11, 11, 11, 11 | 10, 11, 11, 11, 11 | 9, 10, 11, 11, 12 | 11, 11, 11, 12, 13 |

| 10 cysts | 11, 11, 11, 11, 11, 11, 11, 11 | 10, 10, 11, 11, 11, 11, 11, 12 | 10, 10, 10, 10, 11, 11, 11, 11 | 11, 11, 11, 11, 11, 12, 12, 12 |

| 50 cysts | 11, 11, 11, 11, 11, 11, 11, 12 | 10, 10, 10, 11, 11, 11, 11, 12 | 10, 10, 10, 10, 10, 10, 11, 11 | 11, 11, 11, 11, 11, 11, 12, 12 |

BALB/c mice were infected with 10 cysts of the ME49 strain, and three months later, the animals were challenged with either 10 cysts or 50 cysts of the same strain. Another group did not receive any challenge infection. Sera were obtained from each of these three groups weekly for 4 weeks after the challenge infection. In each time point, there were 5 mice in the group without challenge infection and 8 mice in each of two groups with challenge infection.

3.2.2. IgM antibody

IgM antibody titers did not differ among groups of mice with and without challenge infection at each of 4 time points after challenge infection. For example, the antibody titers (log2 antibody titers [×100]) at 1 week after challenge infection were 5.80 ± 0.45 in animals without the challenge infection, 5.88 ± 0.64 in those with challenge infection with 10 cysts, and 5.75 ± 0.46 in those with challenge infection with 50 cysts.

3.2.3. IgA antibody

The IgA antibody titers also did not differ among groups of mice with and without challenge infection at each of 4 time points after challenge infection. For example, the antibody titers (log2 antibody titers [×100]) at 1 week after challenge infection were 6.60 ± 1.14 in animals without the challenge infection, 6.00 ± 0.76 in those with challenge infection with 10 cysts, and 6.12 ± 0.36 in those with challenge infection with 50 cysts.

3.2.4. Tachyzoite-specific SAG1 mRNA levels in the brain

To examine whether tachyzoites did not proliferate in the brains of mice after challenge infection, mRNA levels for tachyzoite–specific SAG1 were measured in the mice challenged with 50 cysts, the higher dose we used. SAG1 mRNA was not detected in any of these animals tested at each of 4 time points after challenge infection (n=4 in each time point).

4. Discussion

The present study demonstrated that increased Toxoplasma IgG and IgA, but not IgM, antibody titers are detectable in sera of mice in association with increases in number of tachyzoites (measured by amounts of mRNA for tachyzoite-specific SAG1) in the brain during the later stage of infection. In contrast, no increase in the antibody titers in either of the immunoglobulin classes was detected following re-infection. As mentioned earlier, increased Toxoplasma IgG antibody levels, but not IgM levels, have been observed in sera of patients with the first onset of schizophrenia [4, 5]. Therefore, Toxoplasma antibody profile observed in mice that have proliferation of tachyzoites in their brains during the chronic stage of infection is consistent with that observed in patients with first-onset of schizophrenia. Increased Toxoplasma IgG antibody levels have also been observed in sera of cryptogenic epilepsy patients [7]. Therefore, proliferation of tachyzoites in the brain during the chronic stage of infection may be involved in the etiology of schizophrenia and cryptogenic epilepsy. This possibility is supported in schizophrenia patients by the evidence of increased Toxoplasma IgG antibody levels in cerebral spinal fluids in addition to sera in recent onset disease [5].

Individuals who are congenitally infected with T. gondii but did not have clinical symptoms of infection at birth often develop ocular toxoplasmosis due to reactivation of infection (proliferation of tachyzoites) later in life [15]. Onset of the disease in these patients is most frequent during ages of 20-30 years [15]. Of interest, age of onset of ocular toxoplasmosis correlates well with that of schizophrenia [16]. In the individuals congenitally infected with T. gondii, it may be possible that reactivation of infection occurs in the brain in a portion of these patients and this reactivated T. gondii infection may be involved in the etiology of schizophrenia. In relation to this, Brown et al [17] recently reported that high maternal Toxoplasma IgG antibody titers are associated with development of schizophrenia in adult offspring. Mortensen et al [18] also reported an association between high Toxoplasma IgG antibody titers at birth and schizophrenia risk.

AIDS patients with HLA-DQ3 are relatively more susceptible to development of toxoplasmic encephalitis due to reactivation of infection, whereas those with HLA-DQ1 are relatively resistant [19]. In congenital infection, the frequency of HLA-DQ3 is higher in infants with hydrocephalus than those without hydrocephalus [20]. Therefore, individuals with HLA-DQ3 appear to be susceptible to develop cerebral toxoplasmosis. It would be important to examine the frequencies of HLA-DQ3 in patients who are seropositive to T. gondii and developed schizophrenia or cryptogenic epilepsy in comparison with a seropositive healthy control population.

In addition to IgG antibody titers, we observed increased serum Toxoplasma IgA antibody titers in association with proliferation of tachyzoites in the brain in mice. Of interest, the differences in the IgA antibody titers between the mice with tachyzoite growth in their brains and those treated with sulfadiazine was greater than those observed in the IgG antibody titers in the same groups. It would be worth examining if increased Toxoplasma IgA titers can be detected in patients with the first onset of schizophrenia and those with cryptogenic epilepsy.

In the model of re-infection, we used the same (type II) strain of the parasite for both initial and challenge infections. T. gondii has three predominant genotypes (type I, II, and III). It was previously reported that challenge infection of type II-infected mice with a type III strain could result in formation of cysts of the type III strain in their brains, whereas challenge infection with the same genotype (type II) strain did not result in formation of the cysts of the second strain [21, 22]. Therefore, when chronically infected hosts become re-infected with a different genotype strain, tachyzoite proliferation of the second strain might occur in the brain before a formation of their cysts and create a similar condition to reactivation of infection. This type of re-infection might be another situation in which serum Toxoplasma IgG and IgA antibody levels increase.

Chronic infection with T. gondii in humans may not be “latent” as it has generally been regarded, and proliferation of tachyzoites in the brain of these individuals may occur more frequently than we consider. Increased Toxoplasma IgG and IgA, but not IgM, antibody titers appear to be a useful serological indicator suggesting an occurrence of cerebral tachyzoite growth in immunocompetent individuals during the chronic stage of infection, especially when clinical symptom(s) in the brain is associated.

Acknowledgments

We thank Marlice Vonck for her assistance in collecting sera from mice, Robert Yolken and Fuller Torrey for their helpful suggestions, and Sara Perkins for her assistance in preparing the manuscript. This work is supported by a grant (#06R-1030) from The Stanley Medical Research Institute, and grants from National Institutes of Health (AI078756, AI073576, and AI077877).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Denkers EY, Gazzinelli RT. Regulation and function of T-cell-mediated immunity during Toxoplasma gondii infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1998;11:569–588. doi: 10.1128/cmr.11.4.569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Boyer K, Marcinak J, McLeod R. Toxoplasma gondii (Toxoplasmosis) In: Long S, Pickering LK, Prober CG, editors. Principles and Practice of Pediatric Infectious Diseases. 3rd. New York: Churchill Livingstone; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pusch L, Romeike B, Deckert M, Mawrin C. Persistent toxoplasma bradyzoite cysts in the brain: incidental finding in an immunocompetent patient without evidence of a toxoplasmosis. Clin Neuropathol. 2009;28:210–212. doi: 10.5414/npp28210. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Torrey EF, Yolken RH. Toxoplasma gondii and schizophrenia, Emerg Infect Dis. 2003;9:1375–1380. doi: 10.3201/eid0911.030143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leweke FM, Gerth CW, Koethe D, Klosterkotter J, Ruslanova I, Krivogorsky B, Torrey EF, Yolken RH. Antibodies to infectious agents in individuals with recent onset schizophrenia. Eur Arch Psychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2004;254:4–8. doi: 10.1007/s00406-004-0481-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brooks RG, McCabe RE, Remington JS. Role of serology in the diagnosis of toxoplasmic lymphadenopathy. Rev Infect Dis. 1987;9:1055–1062. doi: 10.1093/clinids/9.5.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Stommel EW, Seguin R, Thadani VM, Schwartzman JD, Gilbert K, Ryan KA, Tosteson TD, Kasper LH. Cryptogenic epilepsy: an infectious etiology? Epilepsia. 2001;42:436–438. doi: 10.1046/j.1528-1157.2001.25500.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kang H, Suzuki Y. Requirement of non-T cells that produce gamma interferon for prevention of reactivation of Toxoplasma gondii infection in the brain. Infect Immun. 2001;69:2920–2927. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.5.2920-2927.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang X, Michie SA, Xu B, Suzuki Y. Importance of IFN-gamma-mediated expression of endothelial VCAM-1 on recruitment of CD8+ T cells into the brain during chronic infection with Toxoplasma gondii. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2007;27:329–338. doi: 10.1089/jir.2006.0154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Suzuki Y, Joh K, Orellana MA, Conley FK, Remington JS. A gene(s) within the H-2D region determines the development of toxoplasmic encephalitis in mice. Immunology. 1991;74:732–739. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Brown CR, Hunter CA, Estes RG, Beckmann E, Forman J, David C, Remington JS, McLeod R. Definitive identification of a gene that confers resistance against Toxoplasma cyst burden and encephalitis. Immunology. 1995;85:419–428. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Suzuki Y, Orellana MA, Wong SY, Conley FK, Remington JS. Susceptibility to chronic infection with Toxoplasma gondii does not correlate with susceptibility to acute infection in mice. Infect Immun. 1993;61:2284–2288. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.6.2284-2288.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Miller R, Wen X, Dunford B, Wang X, Suzuki Y. Cytokine Production of CD8(+) Immune T Cells but Not of CD4(+) T Cells from Toxoplasma gondii-Infected Mice Is Polarized to a Type 1 Response Following Stimulation with Tachyzoite-Infected Macrophages. J Interferon Cytokine Res. 2006;26:787–792. doi: 10.1089/jir.2006.26.787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Suzuki Y, Wang X, Jortner BS, Payne L, Ni Y, Michie SA, Xu B, Kudo T, Perkins S. Removal of Toxoplasma gondii cysts from the brain by perforin-mediated activity of CD8+ T cells. Am J Pathol. 2010;176:1607–1613. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Remington JS, McLeod R, Thulliez P, Toxoplasmosis DG. In: Infectious Diseases in the Fetus and Newborn Infants. Remington JS, Klein JO, editors. WB Saunders Co.; Philadelphia: 2001. pp. 205–346. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hafner H, Riecher-Rossler A, An Der Heiden W, Maurer K, Fatkenheuer B, Loffler W. Generating and testing a causal explanation of the gender difference in age at first onset of schizophrenia. Psychol Med. 1993;23:925–940. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700026398. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Brown AS, Schaefer CA, Quesenberry CP, Jr, Liu L, Babulas VP, Susser ES. Maternal exposure to toxoplasmosis and risk of schizophrenia in adult offspring. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:767–773. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.4.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mortensen PB, Norgaard-Pedersen B, Waltoft BL, Sorensen TL, Hougaard D, Torrey EF, Yolken RH. Toxoplasma gondii as a risk factor for early-onset schizophrenia: analysis of filter paper blood samples obtained at birth. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:688–693. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Suzuki Y, Wong SY, Grumet FC, Fessel J, Montoya JG, Zolopa AR, Portmore A, Schumacher-Perdreau F, Schrappe M, Koppen S, Ruf B, Brown BW, Remington JS. Evidence for genetic regulation of susceptibility to toxoplasmic encephalitis in AIDS patients. J Infect Dis. 1996;173:265–268. doi: 10.1093/infdis/173.1.265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mack DG, Johnson JJ, Roberts F, Roberts CW, Estes RG, David C, Grumet FC, McLeod R. HLA-class II genes modify outcome of Toxoplasma gondii infection. Int J Parasitol. 1999;29:1351–1358. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(99)00152-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Araujo F, Slifer T, Kim S. Chronic infection with Toxoplasma gondii does not prevent acute disease or colonization of the brain with tissue cysts following reinfection with different strains of the parasite. J Parasitol. 1997;83:521–522. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dao A, Fortier B, Soete M, Plenat F, Dubremetz JF. Successful reinfection of chronically infected mice by a different Toxoplasma gondii genotype. Int J Parasitol. 2001;31:63–65. doi: 10.1016/s0020-7519(00)00151-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]