Abstract

An approach to study bimolecular interactions in model lipid bilayers and biological membranes is introduced, exploiting the influence of membrane-associated electron spin resonance labels on the triplet state kinetics of membrane-bound fluorophores. Singlet-triplet state transitions within the dye Lissamine Rhodamine B (LRB) were studied, when free in aqueous solutions, with LRB bound to a lipid in a liposome, and in the presence of different local concentrations of the electron spin resonance label TEMPO. By monitoring the triplet state kinetics via variations in the fluorescence signal, in this study using fluorescence correlation spectroscopy, a strong fluorescence signal can be combined with the ability to monitor low-frequency molecular interactions, at timescales much longer than the fluorescence lifetimes. Both in solution and in membranes, the measured relative changes in the singlet-triplet transitions rates were found to well reflect the expected collisional frequencies between the LRB and TEMPO molecules. These collisional rates could also be monitored at local TEMPO concentrations where practically no quenching of the excited state of the fluorophores can be detected. The proposed strategy is broadly applicable, in terms of possible read-out means, types of molecular interactions that can be followed, and in what environments these interactions can be measured.

Introduction

Many cellular processes are based on bimolecular, diffusion-mediated reactions occurring in biological membranes (1). To study diffusion behavior in model bilayers or in biological membranes several techniques can be used, such as NMR, fluorescence correlation spectroscopy (FCS), fluorescence recovery after photobleaching, and single-particle tracking (see (2–4) for recent reviews). However, many of these methods primarily address self-diffusion and are less suited to directly monitor molecular encounters in membranes (5). Spin exchange detected in electron-spin resonance (ESR) experiments can provide this information. However, the detection sensitivity is relatively low. Membrane dynamics studies by ESR thus require high concentrations of spin-labels for reaching sufficient signal levels. This increases the risk of perturbation of the bilayer, and can reduce the applicability. Bimolecular reactions in membranes have therefore to a large part been studied by quenching of luminescence from electronically excited probe molecules, labeled to one or several of the interaction partners.

Using fluorescence emission as readout in such quenching studies yields an excellent detection sensitivity. On the other hand, the excited state lifetimes of fluorescent probes are often too short (nanoseconds) to allow enough time for diffusion and collisional encounters of quenchers to significantly affect the emission of the fluorophores. A large fraction of the bimolecular diffusion-mediated processes between components in biological membranes take place in a time range of microseconds to milliseconds. Fluorescent probes emitting in this relatively long timescale are rare, especially if one also adds as criteria that they should have a high fluorescence brightness and be efficiently quenched by contact (6).

In contrast to fluorescence emission, photoexcited triplet state probes are much more long-lived and thus open for membrane dynamic studies at considerably longer timescales (microseconds to milliseconds). Diffusion-mediated triplet-triplet annihilation in membranes has been successfully monitored by transient state absorption spectroscopy (7,8). However, the instrumentation is relatively complicated and offers a limited sensitivity. Alternatively, the extent of triplet state quenching can be followed via the phosphorescence signal of triplet state probes. Phosphorescence labels are far more long-lived than fluorophores, and in this respect more suitable for bimolecular reaction studies in membranes. On the other hand, coupled to the long-lived emission is also the susceptibility of the triplet state to dynamic quenching by oxygen and trace impurities, which can be circumvented only after elaborate and careful sample preparation, or by creating oxygen diffusion barrier shields around the phosphorescent probes (9). This quenching not only shortens the triplet state lifetime but also makes the luminescence practically undetectable. Molecular encounter studies in membranes by this readout is thus largely restricted to deoxygenated, carefully prepared samples, or to larger, shielded, and therefore less environment sensitive probes, which restricts the applicability.

In this work, we introduce an approach to study bimolecular interactions in model lipid bilayers and biological membranes, which exploits the influence of membrane-associated ESR labels on the fluorescence signal of a likewise membrane-bound fluorophore marker. It is well established that some molecular species with electron spin multiplicities >0 are good quenchers of excited electronic states of a wide range of fluorescent molecules (10–12). Quenching of luminescence from fluorescent and phosphorescent probes by nitroxide spin-labels, based on a long-range electron transfer mechanism, has also been demonstrated as a tool to monitor association/clustering of cell surface proteins (13). However, direct measurements of collisional encounters in membranes with sufficient sensitivity have in general proven to be difficult, and are associated with the same drawbacks of fluorescence and phosphorescence quenching as mentioned above.

To overcome these drawbacks, we introduce a strategy that measures the quenching of triplet states of fluorophores by nitroxide labels, via their fluorescence signal, rather than via their several-orders-of-magnitude weaker luminescence emission. Thereby, a high detection sensitivity can be maintained, without sacrificing the benefit of the long lifetime and environmental sensitivity of the triplet state. In particular, we demonstrate the approach using fluorescence fluctuations recorded by FCS as a readout. In FCS, a sparse average number of molecules passing through a focused laser beam in a confocal arrangement give rise to fluctuations in the fluorescence signal (14–16). Transitions to and from a long-lived, dark state of the fluorescent molecules generate fluorescence fluctuations, superimposed on those due to their translational diffusion into and out of the detection volume. From these superimposed fluctuations the population and the population kinetics of the transient state can be determined, and the environmental sensitivity following from their long lifetimes can be united with the signal strength of the fluorescence signal. FCS measurements have proven useful for monitoring several different photoinduced transient states, including triplet states (17), isomerized states (18), and states generated by photoinduced charge transfer (19).

As a proof-of-principle system, we monitored the quenching of the long-lived first excited triplet state of a fluorophore marker (Lissamine Rhodamine B, LRB) by a nitroxide ESR label (TEMPO), recorded via FCS and the strong fluorescence signal of the same fluorophore. The quenching mechanisms were first investigated in aqueous solution. Then the TEMPO-induced quenching of LRB was analyzed in unilamellar liposomes, with the labels covalently linked to lipid headgroups. A two-dimensional model for diffusion-controlled, bimolecular quenching, based on Berg and Purcell (20), was established and found to well predict the diffusion behavior and the collisional encounter frequencies between the LRB- and TEMPO-labeled lipids. The proposed approach can monitor molecular encounters at frequencies where they yield practically no quenching of the fluorescence signal, and can be applied to a wide range of molecular interaction studies in biological membranes.

Materials and Methods

The LRB fluorophore and the spin-label TEMPO choline were purchased from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). LRB was dissolved from powder into dimethyl sulfoxide and then further diluted to nanomolar concentrations by adding ultra pure water.

Liposome preparation

Small unilamellar vesicles (SUVs) were prepared by mixing 385 μL of a 10 mg/mL chloroform solution of the 18:1 (Δ9-Cis) PC lipid, DOPC (1,2-di-(9Z-octadecenoyl)-sn-glycero-3-phosphocholine; Avanti Polar Lipids, Alabaster, AL) with 7.1 μL of a 10 μg/mL chloroform solution of 14:0 LRB PE (1,2-dimyristoyl-sn-glycero-3-phosphoethanolamine-N-(Lissamine Rhodamine B sulfonyl) (ammonium salt); Avanti Polar Lipids). Similarly, 18:1 TEMPO PC (1,2-dioleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho(tempo)choline; Avanti Polar Lipids) in concentrations ranging from 0% to 8% of the total lipid content were mixed into the same chloroform solution. After evaporation under nitrogen flow for 1 h, the lipids were dissolved in a solution containing 4 mL of 0.15 M NaCl and 4 μL of 0.3 M NaOH solution.

The lipid mixture was shaken for 30 min, using a vortex mixer, to form multilamellar liposomes, and then sonicated, using a tip sonicator, until the solution became transparent (∼1 h). The liposome solution was then centrifuged for 30 min (10,000g) to remove residual multilamellar liposomes and metal particles from the sonicator tip. The sonicated liposomes were calculated to have a hydrodynamic radius of 20 ± 4 nm, based on the determined diffusion coefficients from the FCS measurements (performed under nonsaturating excitation intensities). A radius of 20 nm corresponds to ∼7000 lipids per monolayer, if the area per lipid is 72.2 Å2 (21). The ratio of LRB PE to nonfluorescent lipids was 1:120,000 to ensure that each liposome contained, at the most, one fluorophore.

FCS measurements

FCS measurements were performed on a home-built confocal setup, largely arranged as described in Widengren et al. (17). In brief, a 568-nm laser beam from a linearly polarized Kr/Ar-ion laser (model No. 643-RYB-A02; Melles Griot, Carlsbad, CA) was focused by a 63×, NA 1.2 objective (160-mm tube length Plan-Neofluar; Carl Zeiss, Jena, Germany), down to a 1/e2 radius of ∼0.6 μm. Emitted fluorescence was collected by the same objective, passed through a dichroic mirror (model No. FF 576/661; Semrock, Rochester, NY) focused onto a 30-μm diameter pinhole in the image plane, split by a 50/50 nonpolarizing beam-splitter cube (model No. BS010; Thorlabs, Newton, NJ), and detected via a band-pass filter (model No. HQ610/75; Chroma Technology, Rockingham, VT) by two avalanche photodiodes (APDs) (model No. SPCMAQR-14/16; Perkin-Elmer Optoelectronics, Wellesley, MA). By use of two APDs, and by cross-correlating their signals, the influence of the dead-time of the detectors could be eliminated in the correlation analysis (22). The detection volume was assumed to be a three-dimensional Gaussian with an axial 1/e2-extension ∼5 times the transverse 1/e2-radius. The APD signals were processed by a correlator (model No. ALV-5000-E; ALV, Langen, Germany, with an ALV 5000/FAST Tau Extension board). The excitation power of the laser was varied between 0.1 and 1 mW, corresponding to mean irradiances between 25 and 250 kW/cm2 in the focal plane of the detection volume. The solution measurements were performed in ultrapure water (Easypure; Wilhelm Werner, Leverkusen, Germany). The liposome measurements were performed in 150 mM NaCl, with the pH set between 7 and 9 by addition of NaOH. Each correlation curve was recorded for 60 s.

Deoxygenation was obtained by placing the samples in a sealed chamber. Argon or nitrogen gas was bubbled through a water chamber and flushed through the sample chamber for at least 40 min before measurements.

Fluorescence lifetime measurements

Time-correlated single photon counting (TCSPC) measurements were performed on a spectrofluorometer with a TCSPC option (FluoroMax3; Horiba Jobin Yvon, Longjumeau, France). To avoid reabsorption and reemission effects, the fluorophore concentrations were kept strictly below 1 μM. In the TCSPC measurements the samples were excited by a NanoLED source emitting at 495 nm with a repetition rate of 1 MHz and pulse duration of 1.4 ns. Typically 10,000 photon counts were collected in the maximum channel using 2048 channels. The decay parameters were determined by least-squares deconvolution using a monoexponential model, and their quality was judged by the reduced χ2 values and the randomness of the weighted residuals.

Theory

Electronic state model

The electronic states of LRB involved in the processes of fluorescence at 568-nm excitation wavelength can be modeled as shown in Fig. 1, lower part. In the model, S0 denotes the ground singlet state, S1 is the excited singlet state, and T1 is the lowest triplet state. The values k01, k10, kISC, and kT are the rate constants for excitation to S1, relaxation of S1 to S0, intersystem crossing from S1 to T1, and relaxation of T1 back to S0, respectively. The value k01 can be written as σ01Iexc, where σ01 is the excitation cross section for transitions from S0 to S1, and Iexc is the excitation intensity. As reasonable approximations for the triplet state population kinetics of LRB in water at 568 nm excitation, effects of excitation to higher singlet and triplet states can be neglected, excitation and emission dipole moments can be considered isotropic, and the triplet state completely nonluminescent. Typically, k10 and kISC are ∼109 s−1 and 106 s−1, respectively. Hence, transition to the triplet state only takes place in ∼1/1000 excitation-emission cycles. However, once populated, the triplet state is quite long-lived (μs-ms), with kT in the order of 103–106 s−1. As a consequence, the steady-state triplet-state population can accumulate strongly, in particular at excitation intensities, at which k01 is comparable to k10 and in the absence of triplet state quenchers, such as molecular oxygen, yielding very low kT rates.

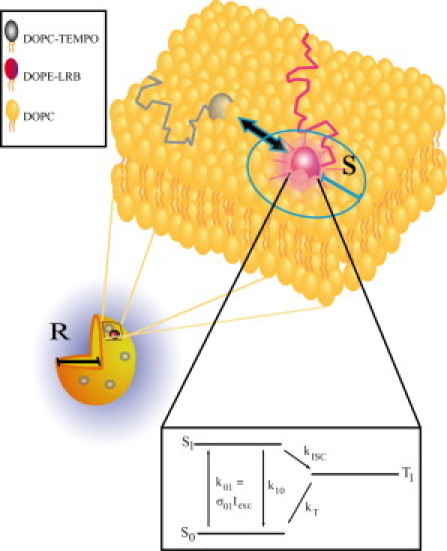

Figure 1.

Schematic view of the diffusion-mediated interaction between the fluorophore LRB and the triplet quencher TEMPO in a lipid vesicle. Both the intersystem crossing, kISC, and the triplet decay, kT, rates of LRB are enhanced by the presence of the ESR probe TEMPO, as described by Eq. 8. R denotes the radius of the vesicles and s is the reaction distance between the LRB and TEMPO molecules. (Bottom part) Three-state electronic model of LRB and for organic fluorophores in general (see text for details).

Presence of paramagnetic compounds like oxygen or TEMPO can strongly influence the rates of singlet-triplet transitions. Molecular oxygen 3O2 is in its ground state in a triplet state, which makes it to an efficient quencher of triplet state fluorophores by triplet-triplet energy transfer. Due to the paramagnetic properties of molecular oxygen, significant changes in both kT and kISC can be observed in solutions upon variation of the oxygen concentration (17,23).

Similarly, TEMPO has been observed to affect the triplet state of Rhodamine dyes (23). In comparison to oxygen, however, the triplet state quenching constant was reported to be ∼10 times lower. Given that the quenching mechanism is collision controlled, this difference is likely to be attributed to the difference in the molecular dimensions and diffusion coefficients between oxygen and TEMPO molecules. As paramagnetic compounds, both 3O2 and TEMPO are known also to affect the kISC rate of the fluorophores.

Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy

In FCS, fluorescent molecules in a confocal detection volume are excited by a focused laser beam. The fluorescence intensity fluctuations from the molecules are exploited to monitor their dynamic processes. The fluctuations are analyzed in terms of a normalized autocovariance function, G(τ). For molecules undergoing electronic state transitions between their two lowest singlet states (S0, S1) and a dark triplet state (T1), as well as diffusion into and out of the FCS detection volume, G(τ) can be expressed as (17)

| (1) |

Here, N is the average number of fluorescent molecules in the detection volume. The values ω0 and ωz denote the distances from the center of the detection volume, in the radial and axial directions, respectively, at which the detection efficiency has dropped by a factor e2, compared to the peak value in the center. The expression GD(τ) represents the diffusion dependent part of G(τ) normalized to unity amplitude. GD(τ) decays with a time τD, corresponding to the average dwell times of the fluorescent molecules in the detection volume. The value denotes the average steady-state probability for the fluorescent molecules within the detection volume to be in their triplet states. The triplet relaxation time τT represents the equilibration time between the two singlet states and the triplet state. In an air-equilibrated aqueous solution, this equilibration typically occurs in the microsecond time range. For a fluorescent molecule, with electronic states as depicted in Fig. 1, located at and experiencing an excitation intensity, ,

| (2) |

| (3) |

Experimentally, by fitting Eq. 1 to the recorded FCS curves, the parameters and τT represent average values within the detection volume, and can be estimated as described in Widengren et al. (17).

A simple relation between and can be expressed if is extracted from Eq. 3, i.e.,

| (4) |

and substituted into Eq. 2,

| (5) |

Diffusion-controlled reactions

In bimolecular, diffusion-controlled reactions the reaction radii and concentrations of the two substrates have been derived for two (20,24) or three (25) dimensions. Razi Naqvi (24) and Smoluchowski (25) assume that the reactions take place in an infinite area or volume, respectively, while Berg and Purcell (20) handle reactions taking place on a limited surface. In three dimensions, the number of reactions per second between molecules, X (analogous to the TEMPO molecules in our study), and a single molecule, Y (analogous to LRB), is given by Smoluchowski (25):

| (6) |

Here, DX and DY are the diffusion coefficients of the molecules X and Y, respectively, and P is the probability of a reaction to occur when the reaction partners are within the reaction distance, s, from each other. Equation 6 is based on the assumption that the concentration of X, denoted [X], is constant in time at an infinite distance from Y.

When the reactions take place in a spherical shell (here: for reactions in a liposome membrane), the number of reactions per second between X-molecules (here: TEMPO-labeled lipid molecules) and a single molecule Y (here: a LRB-labeled lipid molecule) is approximately (20)

| (7) |

This expression is based on the understanding that the reaction distance, s, is much smaller than the shell radius, R (see Fig. 1). Furthermore, analogous to Eq. 6, a probability, P, has been introduced accounting for the fact that not all encounters between molecules X and Y lead to a reaction. In the special case when all molecules occupy the same average area, A, then the reaction rate ϕ, may be written as

| (8) |

Here, L is the fraction of X-molecules relative to the total number of molecules in the membrane.

Results and Discussion

Solution measurements

Time-correlated single photon counting (TCSPC) measurements of LRB in aqueous solution revealed that upon addition of TEMPO in 0.1–10 mM concentrations a small decrease in the fluorescence lifetime of LRB can be observed. The enhancement of k10 by the addition of TEMPO (given in M) follows, to a first approximation, a linear relationship

The presence of 1 mM TEMPO thus yields a relative change of k10 of LRB of ∼1–2%. A similar relative change in the fluorescence intensity can be expected, when recorded under conventional excitation conditions (nonsaturating excitation intensities). Given the paramagnetic properties of TEMPO, a considerably stronger relative effect can be expected on the transition rates to and from the triplet state of LRB.

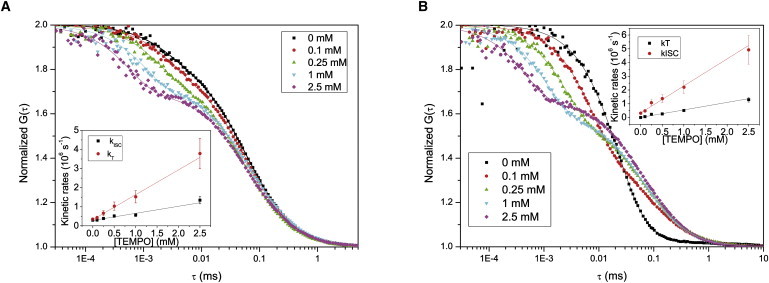

To investigate the quenching properties of TEMPO on the triplet states of LRB, a series of FCS measurements were performed in aqueous solution, both under air-saturated and deoxygenated conditions. Under air-saturated conditions, FCS curves were recorded from LRB sample solutions with varying concentrations of TEMPO (0–2.5 mM), and for each TEMPO concentration, the excitation power was varied from 100 to 1000 μW (corresponding to average excitation irradiances in the detection volume of 25–250 kW/cm2). Upon addition of TEMPO, an increase in the triplet amplitude, , and a drastic shortening of the triplet relaxation time, τT, could be observed in the correlation curves (Fig. 2 A). The correlation curves could be well fitted to Eq. 1. At TEMPO concentrations higher than 10 mM, the triplet relaxation times become so fast that the full relaxation process cannot be adequately analyzed within the time resolution accessible by our correlator (first time channel is 12.5 ns). By plotting the space-averaged parameters τT versus , as recorded from the FCS measurements, the triplet deactivation rate, kT, was directly determined by a linear fit according to the τT versus dependence of Eq. 5. For each concentration of TEMPO, the intersystem crossing rate, kISC, could then be obtained as a global fitting parameter from the excitation irradiance dependence of τT and using Eq. 2 and Eq. 3. Here, the determined kT values were used as fixed parameters. Also, σ01 was fixed to 3.1 × 10−16 cm2 (26) and the Gaussian-Lorentzian distribution of excitation irradiances experienced in the detection volume were taken into consideration (see (17) for details). The term k10 was fixed to a value given by the TCSPC experiments, taking also the minor relative quenching of k10 by TEMPO (see above) into account. The resulting kT and kISC are plotted versus TEMPO concentration in the inset of Fig. 2 A. It can be noted that both kT and kISC are influenced by the concentration of added TEMPO, [TEMPO], displaying a close to linear dependence. Considering the influence of TEMPO on kT and kISC to be a bimolecular reaction, it can be described by the equations

| (9) |

| (10) |

Fitting Eqs. 9 and 10 to the data in the inset of Fig. 2 A then yields the molar quenching rate coefficients kQISC = 1.30 × 109 M−1 s−1 and kQT = 0.37 × 109 M−1 s−1, respectively. In the inset of Fig. 2 A, error bars indicate the random errors of the determined kT and kISC parameter values. They were estimated from the dependencies of these rates on the experimental parameters as stated in Eqs. 2–5 and the corresponding relative errors of these parameters. The relative errors of the determined kT and kISC parameters in this study were thereby estimated to 14% and 21%, respectively.

Figure 2.

Set of FCS curves of LRB, with different concentrations of TEMPO added (0–2.5 mM). Fits and residuals are obtained according to Eq. 1. (A) FCS curves measured in an air-saturated aqueous solution. Excitation irradiance 100 kW/cm2. The amplitudes of the triplet relaxation term and the triplet relaxation time τT for the different curves were determined to be 0.15:3.0 μs (0 mM), 0.19:2.6 μs (0.1 mM), 0.23:1.8 μs (0.25 mM), 0.29:1.1 μs (1 mM), and 0.30:0.57 μs (2.5 mM). The characteristic diffusion time, τD, was for this set of curves determined to be 59 μs ± 10%. (Inset) The [TEMPO] dependence of kISC and kT, as obtained from the FCS parameters Teq and τT (Eqs. 2 and 3), measured at different excitation irradiances (25–250 kW/cm2). Lines represent linear regression fits to Eqs. 9 and 10, yielding the following intrinsic and quenching rates: kISC = 3.3 × 105 s−1 and kQISC = 1.3 × 109 M−1 s−1 for the intersystem crossing to T1, and kT = 2.8 × 105 s−1 and kQT = 3.7 × 108 M−1 s−1 for the T1 deactivation. (B) Set of FCS curves measured in a deoxygenated aqueous solution. Excitation irradiance 100 kW/cm2. The amplitudes of the triplet relaxation term and the triplet relaxation time τT for the different curves were determined to be 0.83:34 μs (0 mM), 0.53:7.7 μs (0.1 mM), 0.43:2.6 μs (0.25 mM), 0.40:1.1 μs (1 mM), and 0.34:0.46 μs (2.5 mM). The characteristic diffusion time τD = 67 microseconds ± 10%. The longer τD compared to that obtained in panel A, can be attributed to saturation broadening of the fluorescence emission profile in the detection volume due to a higher triplet state build-up. (Inset) The [TEMPO] dependence of kISC and kT, as obtained from the FCS parameters Teq and τT (Eqs. 2 and 3), measured at different excitation irradiances (25–250 kW/cm2). Lines represent linear regression fits to Eqs. 9 and 10, yielding: kISC = 3.3 × 105 s−1 and kQISC = 2.0 × 109 M−1 s−1 for the intersystem crossing to T1, and kT = 5.4 × 103 s−1 and kQT = 5.5 × 108 M−1 s−1 for the T1 deactivation.

The FCS measurements were repeated on the same samples and with the same excitation powers (100–1000 μW) under deoxygenated conditions (Fig. 2 B). Similar to the observation in air-saturated measurements, the triplet relaxation times were found to decrease upon addition of TEMPO. However, in contrast to the air-saturated measurements, the triplet state amplitudes, , decreased with increasing [TEMPO]. In air-saturated aqueous solutions, most of the deactivation of T1 is due to quenching by molecular oxygen. In the absence of oxygen, kT is reduced by several orders of magnitude, down to 103 s−1. The value kISC, on the other hand, is only reduced by approximately a factor of two. Addition of TEMPO in a deoxygenized environment then leads to a much stronger relative increase of kT than of kISC, and a stronger relative increase of kT than would be generated in an air-saturated solution. From Eq. 3 it can be noted that at excitation intensities approaching saturation (σ01Iexc > k10),

i.e., the relation between kISC and kT determines . The decrease of with increasing [TEMPO] found in deoxygenated solutions thus reflects the same absolute influence of TEMPO on the kT and kISC rates of LRB, but a different relative influence, as compared to the effects found under air-saturated conditions. For the deoxygenated measurements, the kinetic rates were determined in the same manner as for the air-saturated measurements, using Eqs. 2, 3, and 5. The determined rate parameters are plotted versus TEMPO concentration in the inset of Fig. 2 B. By a linear fit, according to Eqs. 9 and 10, the molar quenching rate coefficients were determined to be kQISC = 2.0 × 109 M−1 s−1 and kQT = 0.55 × 109 M−1 s−1. These values are slightly higher than the corresponding quenching rates determined in the air-saturated measurements (Fig. 2 A, inset). A possible explanation to this small difference is that TEMPO may react with molecular oxygen. Annihilation between TEMPO and 3O2, which both are in their triplet states, and which both can enhance kISC and kT, could be present in the air-saturated measurements but will be negligible in the deoxygenated measurements.

The expected collision frequency between a single LRB molecule and TEMPO molecules was calculated from Eq. 6 to be 8 × 109 M−1 s−1. In these calculations, the diffusion coefficients of LRB and TEMPO were specified to be 4 × 10−10 m2/s (27) and 6 × 10−10 m2/s (28), respectively. From the diffusion coefficients, their corresponding hydrodynamic radii were determined from the Stokes-Einstein relationship to 0.4 and 0.6 nm, respectively. From the sum of the hydrodynamic radii, we then estimate s = 0.4 nm + 0.6 nm = 1.0 nm. Based on the determined kQISC and kQT and by use of Eqs. 9 and 10, the probability, P, that a collision results in a reaction affecting kT or kISC, was then determined to be 4.6% and 16% () for the air-saturated measurements and 6.9% and 25% () for the deoxygenated measurements, respectively. The quenching of T1 accounted for by kQT is presumably mediated by triplet-triplet annihilation. For this quenching mechanism, and according to the spin statistical factor (29), only every ninth collision should affect the kT rate. From that perspective, the 5–7% probability is reasonably close to that limit. On the other hand, the quenching of S1 into T1, accounted for by kQISC, is likely to be caused by spin-orbit coupling, which does not have a similar limitation by a spin-statistical factor. For the kISC, we note that only every fourth or fifth collision results in a reaction affecting this rate.

From the quenching coefficients one can note that the effect of TEMPO is approximately three-to-four-times stronger on the kISC rate, than on the kT, which results in the observed increase of the triplet state fraction under air-saturated conditions. The opposite effect was observed in a previous study (30), where the effect of TEMPO on the triplet state parameters of Rhodamine 6G (Rh6G) was investigated. However, Rh6G has a lower maximum absorption wavelength than LRB, i.e., a higher lying first excited singlet state. Because the energy levels of S1 and T1 are typically closely related, the T1 state of Rh6G, also, can be expected to lie higher in energy than that of LRB. Because of this, charge transfer reactions to the ground triplet state of TEMPO are more likely to occur from the T1 state of Rh6G than from the T1 state of LRB. This additional deactivation channel of the T1 state should then be reflected in the FCS measurements as a decreased steady-state triplet population and a shortening of the triplet relaxation time. Indeed, FCS measurements on Rh6G and TEMPO showed not only a decrease of the triplet state fraction (in agreement with results reported in Heupel (30)), but also the presence of a second relaxation component in the correlation curves. This additional term can be attributed to formation of Rh6G radicals via their T1 states (31). However, for LRB the FCS measurements give no evidence of a strong charge-transfer-mediated quenching of T1. This effect was therefore not included in the analysis, and the effects of TEMPO on other fluorophores fall outside the scope of this investigation and were not further investigated in this work.

Liposome measurements

As for the solution studies, TCSPC measurements were performed on LRB-labeled lipids in liposomes freely diffusing in an aqueous solution. Upon addition of TEMPO-labeled lipids into the liposomes, a small decrease in the fluorescence lifetime of LRB could be observed. In contrast to the quenching in solution, this enhancement of k10 follows to a first approximation an exponential relationship

Here, L denotes the fraction of TEMPO-labeled lipids in the liposomes. The presence of 5% of TEMPO-labeled lipids yields a relative change of k10 of LRB of ∼5%.

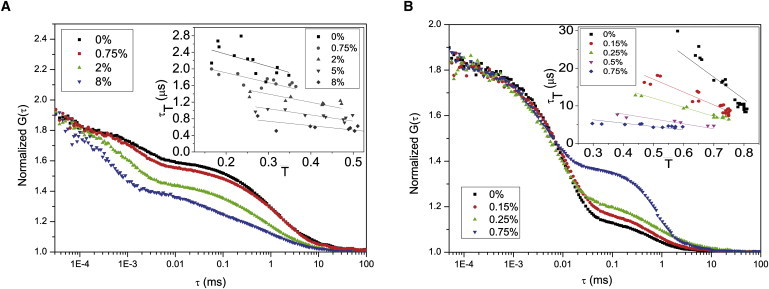

To investigate the corresponding influence of adding TEMPO-labeled lipids onto the kT and kISC rates, FCS measurements were performed on LRB-labeled liposomes in aqueous solution, with varying fractions of TEMPO-labeled lipids, both under air-saturated and deoxygenated conditions. For the air-saturated measurements, the fraction of TEMPO-labeled lipids in the liposomes, L, was varied from 0 to 8%. For each fraction, FCS curves were recorded at different excitation irradiancies, from 25 kW/cm2 up to 175 kW/cm2. In Fig. 3 A, a series of correlation curves are shown, recorded at the same excitation irradiance, but where the SUVs contained different fractions of TEMPO-labeled lipids. Apart from a distinct decay in the microsecond range, which can be attributed to singlet-triplet transitions and described by Eq. 1, a second exponentially decaying process was observed in the correlation curves. This process had a typical relaxation time of ∼60 ns, an approximate relative amplitude of 0.2, and was independent of both L and the applied excitation irradiance. We therefore assume that this process is not photophysical in its origin, but likely to be generated by rotational diffusion of the fluorophores attached to the SUVs. When increasing L, a strong increase in the triplet amplitude, , and a shortening of the triplet relaxation time, τT, could be observed in the correlation curves (Fig. 3 A).

Figure 3.

Set of FCS curves of LRB-labeled liposomes (maximum one LRB-labeled lipid per liposome). Fits and residuals obtained according to Eq. 1. (A) FCS curves measured under air-saturated conditions. The fraction, L, of the lipids labeled with TEMPO varied from 0 to 8%. Excitation irradiance 100 kW/cm2. The amplitudes of the triplet relaxation term and the triplet relaxation time τT for the different curves were determined to be 0.26/2.2 μs (0%), 0.30:1.8 μs (0.75%), 0.43:1.1 μs (2%), and 0.50:0.5 μs (8%). The characteristic diffusion time, τD, was for the curves determined to be 1.45 ms ± 10%. (Inset) Relaxation times, τT, and amplitudes, , obtained by fitting FCS curves as represented in panel A to Eq. 1. For each L, a series of FCS curves were recorded at different excitation intensities (from 25 kW/cm2 to 175 kW/cm2), yielding the different τT and values in the graph. (Solid lines) Fittings of the measured τT versus parameters for each L, according to Eq. 5. From these fits, the following kT values were obtained (given in 106 s−1): 0.34 (0%), 0.42 (0.75%), 0.50 (2%), 0.67 (5%), and 0.95 (8%). (B) Set of FCS curves, measured in a deoxygenated aqueous solution. TEMPO-labeled lipid fraction, L, varied from 0 to 0.75%. Excitation irradiance 100 kW/cm2. Obtained and τT for the different curves: 0.63:10.4 μs (0%), 0.57:10.1 μs (0.15%), 0.52:6.9 μs (0.25%), and 0.41:4.3 μs (0.75%). The characteristic diffusion time, τD, was for the curves determined to 0.5 ms ± 27% (the high uncertainty attributed to the high triplet state build-up and the corresponding saturation of the fluorescence emission profile in the detection volume). (Inset) Relaxation times, τT, and amplitudes, , from data recorded as in panel B fitted to Eq. 1. Fractions, L, of TEMPO-labeled lipids as indicated. For each L, FCS curves were recorded at different excitation intensities (from 25 kW/cm2 to 175 kW/cm2). (Solid lines) Fittings of the measured τT versus parameters for each L, according to Eq. 5, yielding the following kT values (in 106 s−1): 0.017 (0%), 0.029 (0.15%), 0.042 (0.25%), 0.077 (0.5%), and 0.11 (0.75%).

Analogous to the solution measurements, the measured parameters were plotted τT versus (Fig. 3 A, inset), and the triplet deactivation rate, kT, for each local concentration of TEMPO-labeled lipids, L, could be directly determined from a linear fit according to Eq. 5. From the obtained kT rates, the corresponding intersystem crossing rates for each L were then determined from Eqs. 2 and 3.

Additional FCS measurements on SUVs were performed under deoxygenated conditions, with L varying from 0 to 2%. For each L, FCS measurements were performed under excitation irradiances ranging from 25 kW/cm2 to 175 kW/cm2. With increasing L, the triplet state parameters showed the same principal behavior as found for [TEMPO] in the deoxygenated solution measurements (Fig. 3 B). Higher concentrations of TEMPO-labeled lipids in the SUVs lead to reduced triplet relaxation times and, in contrast to the air-saturated SUV measurements but in correspondence with the deoxygenated solution measurements, decreased triplet state amplitudes. The measured parameters were plotted, τT versus (Fig. 3 B, inset), and the kT rates for each L were obtained by fitting the τT versus-T plot to Eq. 5. The corresponding kISC rates were then determined for each L from the excitation intensity dependence of τT and and by use of Eqs. 2 and 3, in the same manner as for the previous FCS measurement series.

The kT and kISC rate parameters, determined for the different fractions, L, were then fitted to

| (11) |

| (12) |

Here, the molecular encounter flow rates, ϕT(L) and ϕISC(L), are given by Eq. 8, for triplet deactivation from T1 and intersystem crossing to T1, respectively.

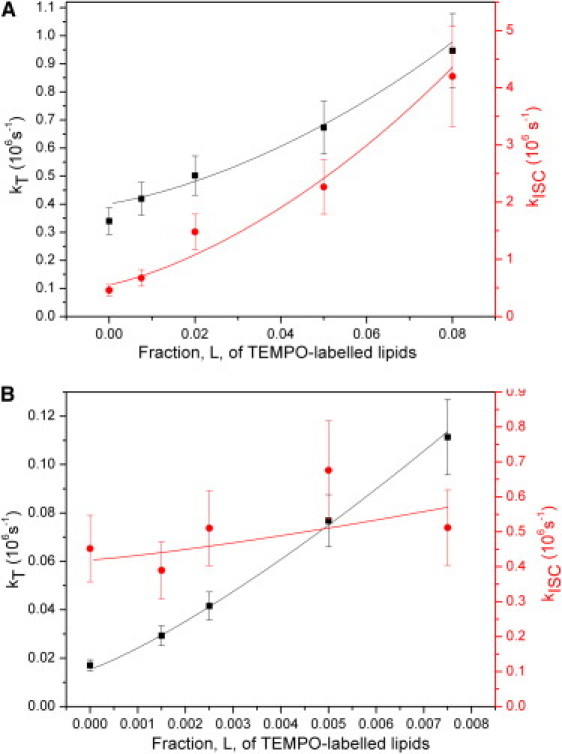

The kT and kISC rates, determined under air-saturated and deoxygenated conditions, together with the corresponding fitted curves according to Eqs. 11 and 12, are shown in Fig. 4, A and B. In this fitting procedure of the kISC and kT rates, the typical lipid area, A, was specified to be 72.2 Å2 (21), the diffusion coefficient of the DOPC lipids specified to 9 μm2/s (32), and the zero fraction (L = 0) rates were allowed to vary freely. At high quencher concentrations, the fits depended significantly on the reaction distance, s. In the air-saturated measurements, a reaction radius of 0.4 nm described the experimental data more satisfyingly than a reaction radius of 1 nm, and s was therefore set to 0.4 nm in the further analysis. The reaction probabilities, P, were for the deoxygenated liposome measurements determined to be 17 ± 10% for a reaction affecting kT. The reaction probability for kISC was determined to 28%, however, with a large uncertainty. For the air-saturated measurements, the corresponding probabilities were determined to 6 ± 5% and 28 ± 20%, respectively. It can be noted that these reaction probabilities are slightly different from those determined in the solution measurements.

Figure 4.

Triplet kinetic rates versus fractions of TEMPO-labeled lipids. Quenching reactions leading to intersystem crossing from S1 to T1 (red circles) or deactivation of the T1 state (black squares) of LRB. (A) Liposomes in an air-saturated solution. Fitting the average times versus L dependence to Eqs. 11 and 12, yielded P = 6% for kT and P = 28% for kISC. Parameter values used in the fit: s = 0.4 nm, Alipid = 72.2 Å2, and Dlipid = 9 μm2/s. (B) Liposomes in a deoxygenated solution. The average times versus L dependence was fitted to Eqs. 11 and 12, yielding a reaction probability per molecular encounter P = 17% for kT and P = 28% for kISC. Parameter values used in the fit: s = 0.4 nm, Alipid = 72.2 Å2, and Dlipid = 9 μm2/s.

One contributing reason to this difference can be that the LRB and TEMPO molecules may be constrained in their mutual orientation with respect to each other when bound to lipids in a membrane, which may change the probability for a reaction to take place upon a collisional encounter. Additionally, the environmental conditions experienced by LRB and TEMPO are likely to differ between the liposome measurements and those in aqueous solution. The reaction probabilities determined for the air-saturated liposome measurements were found to be lower than those determined under deoxygenated conditions, in particular for T1 deactivation. This is in analogy to the solution measurements, where higher quenching rates kQT and kQISC were found in the absence of oxygen. Similar to the solution measurements, we expect TEMPO and molecular oxygen to react with each other, leading to lower reaction probabilities in the air-saturated liposome measurements. From the liposome measurements under deoxygenated conditions, Fig. 4 B, it can be noted that ϕT(L) can be much more precisely determined than ϕISC(L).

In general, in our measurements, the kT parameters could be determined directly from the versus τT plots (Fig. 3, A and B, insets) by use of Eq. 5, without the need to include assumptions about the excitation irradiances applied. Moreover, for the deoxygenated measurements, it should be noted that for triplet state measurements by FCS, the intersystem crossing rates are more difficult to determine when the relative difference between the kISC and kT rates is large (17). This circumstance is likely to make the determination of the reaction times for kISC enhancement more precise when performed under air-saturated (Fig. 4 A) than under deoxygenated conditions (Fig. 4 B). However, taken together it can also be noted that the combination of the determined and τT parameters, as plotted in Fig. 3, A and B (insets), well reflects quite small differences in molecular encounter frequencies/local TEMPO concentrations in the investigated lipid vesicles.

Concluding Remarks

Fluorescence quenching studies are widely used to monitor molecular interactions, accessibilities, and microenvironments. In this work, it is shown how the detection sensitivity of the fluorescence signal in such studies can be exploited without losing the ability to follow low-frequency molecular interactions, taking place far beyond the timescale of the fluorescence lifetimes. By FCS, transitions to and from long-lived transient states can be monitored via the fluctuations they generate in the fluorescence signal. Similarly, we show that presence of the electron spin-label TEMPO leads to an increase of the transition rates to and from the lowest triplet state of LRB, both in aqueous solution, as well as in lipid membranes. The triplet state transition rates were sensitive to molecular encounter frequencies between TEMPO and LRB considerably lower than those recordable by traditional fluorescence readouts, such as fluorescence intensity or fluorescence lifetime measurements. In the absence of oxygen, the triplet state lifetimes get significantly longer and even slower molecular interaction frequencies can be followed. The highest sensitivity will therefore be achieved under deoxygenized conditions.

In lipid membrane studies, the concentrations of both fluorophore and quencher molecules can be kept quite low, which minimizes the risk to influence the membrane by high label concentrations. The approach can be extended to other fluorophores, electron spin labels, and even other triplet state quenchers/promoters than those used in this study. Studies of molecular interactions in membranes of individual immobilized cells by the presented approach will be challenged by photobleaching and fluorophore depletion (33). However, like the lipid-lipid interactions in the membranes of the freely diffusing liposomes studied here, molecular interactions in cells that move with respect to the laser excitation, or vice versa, should strongly reduce such complications. Similar interaction studies as shown here for lipids can also be performed on, e.g., membrane proteins, which can be readily labeled with both fluorescence and electron spin resonance probes. FCS is not the only method that provides the possibility to follow the influence of an electron-spin label on the triplet state rate parameters of a fluorophore, via a strong fluorescence signal. Recently, it was shown that by use of modulated excitation, triplet state population, and kinetics of fluorophores can be monitored in a highly parallel fashion, with relatively minor instrumental and sample constraints (34). The presented principal approach, by allowing low-frequency interactions to be monitored with a bright fluorescence signal, thus offers a broad applicability, in terms of read-out means, types of molecular interactions that can be followed, and in what environment these interactions can be measured.

Acknowledgments

The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Community's Seventh Framework Program (grant No. 201-837), the Swedish Research Council, and the Knut and Alice Wallenberg Foundation.

Footnotes

August Andersson's present address is Department of Applied Environmental Science, Stockholm University, SE-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden.

References

- 1.Almeida P., Vaz W. Lateral diffusion in membranes. In: Lipowsky R., Sackmann E., editors. Handbook of Biological Physics. Elsevier; Amsterdam: 1995. pp. 305–357. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lindblom G., Orädd G. Lipid lateral diffusion and membrane heterogeneity. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1788:234–244. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.08.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chiantia S., Ries J., Schwille P. Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy in membrane structure elucidation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2009;1788:225–233. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamem.2008.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jaskolski F., Henley J.M. Synaptic receptor trafficking: the lateral point of view. Neuroscience. 2009;158:19–24. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.01.075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Medvedeva N., Papper V., Likhtenshtein G.I. Study of rare encounters in a membrane using quenching of cascade reaction between triplet and photochrome probes with nitroxide radicals. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2005;7:3368–3374. doi: 10.1039/b506135k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Melo E., Martins J. Kinetics of bimolecular reactions in model bilayers and biological membranes. A critical review. Biophys. Chem. 2006;123:77–94. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2006.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Razi Naqvi K., Behr J.-P., Chapman D. Methods for probing lateral diffusion of membrane components: triplet–triplet annihilation and triplet–triplet energy transfer. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1974;26:440–444. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Baranyai P., Gangl S., Vidóczy T. Using the decay of incorporated photoexcited triplet probes to study unilamellar phospholipid bilayer membranes. Langmuir. 1999;15:7577–7584. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lebedev A.Y., Cheprakov A.V., Vinogradov S.A. Dendritic phosphorescent probes for oxygen imaging in biological systems. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 2009;1:1292–1304. doi: 10.1021/am9001698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green S.A., Simpson D.J., Blough N.V. Intramolecular quenching of excited singlet-states by stable nitroxyl radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1990;112:7337–7346. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Birks J. Wiley-Interscience; London, UK: 1970. Photophysics of Aromatic Molecules. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Matko J., Ohki K., Edidin M. Luminescence quenching by nitroxide spin labels in aqueous solution: studies on the mechanism of quenching. Biochemistry. 1992;31:703–711. doi: 10.1021/bi00118a010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Matko J., Jenei A., Edidin M. Luminescence quenching by long range electron transfer: a probe of protein clustering and conformation at the cell surface. Cytometry. 1995;19:191–200. doi: 10.1002/cyto.990190302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gösch M., Rigler R. Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy of molecular motions and kinetics. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2005;57:169–190. doi: 10.1016/j.addr.2004.07.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Widengren J., Mets Ü. Conceptual basis of fluorescence correlation spectroscopy and related techniques as tools in bioscience. In: Zander C., Enderlein J., Keller R.A., editors. Single Molecule Detection in Solution, Methods and Applications. Wiley-VCH; Weinheim, Germany: 2002. p. 69. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Haustein E., Schwille P. Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy: novel variations of an established technique. Annu. Rev. Biophys. Biomol. Struct. 2007;36:151–169. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biophys.36.040306.132612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Widengren J., Mets Ü., Rigler R. Fluorescence correlation spectroscopy of triplet states in solution—a theoretical and experimental study. J. Phys. Chem. 1995;99:13368–13379. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Widengren J., Schwille P. Characterization of photoinduced isomerization and back-isomerization of the cyanine dye Cy5 by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2000;104:6416–6428. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Widengren J., Dapprich J., Rigler R. Fast interactions between Rh6G and dGTP in water studied by fluorescence correlation spectroscopy. Chem. Phys. 1997;216:417–426. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Berg H.C., Purcell E.M. Physics of chemoreception. Biophys. J. 1977;20:193–219. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(77)85544-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Balali-Mood K., Harroun T.A., Bradshaw J.P. Molecular dynamics simulations of a mixed DOPC/DOPG bilayer. Eur. Phys. J. E. Soft Matter. 2003;12:S135–S140. doi: 10.1140/epjed/e2003-01-031-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hanbury Brown R., Twiss R.Q. Correlation between photons in two coherent beams of light. Nature. 1956;177:27–29. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stracke F., Heupel M., Thiel E. Singlet molecular oxygen photosensitized by Rhodamine dyes: correlation with photophysical properties of the sensitizers. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 1999;126:51–58. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Razi Naqvi K. Diffusion-controlled reactions in two-dimensional fluids: discussion of measurements of lateral diffusion of lipids in biological membranes. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1974;28:280–284. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smoluchowski M. Attempt on a mathematical theory for coagulation kinetics in colloidal solutions. [Versuch einer mathematischen Theorie der Koagulationskinetik kolloider Lösungen] Z. Phys. Chem. 1917;92:129. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ramachandran R., Tweten R.K., Johnson A.E. The domains of a cholesterol-dependent cytolysin undergo a major FRET-detected rearrangement during pore formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2005;102:7139–7144. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500556102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dertinger T., Pacheco V., Enderlein J. Two-focus fluorescence correlation spectroscopy: a new tool for accurate and absolute diffusion measurements. ChemPhysChem. 2007;8:433–443. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200600638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Janiszewska A.M., Grzeszczuk M. Mechanistic-kinetic scheme of oxidation/reduction of TEMPO involving hydrogen bonded dimer. RDE probe for availability of protons in reaction environment. Electroanalysis. 2004;16:1673–1681. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ishii K., Takeuchi S., Kobayashi N. A concept for controlling singlet oxygen (1δg) yields using nitroxide radicals: phthalocyaninatosilicon covalently linked to nitroxide radicals. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2004;126:2082–2088. doi: 10.1021/ja035352v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Heupel M., Gregor I., Thiel. E. Photophysical and photochemical properties of electronically excited fluorescent dyes: a new type of time-resolved laser-scanning spectroscopy. Int. J. Photoenergy. 1999;1:165–172. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Becker S., Gregor I., Thiel E. Photoreactions of rhodamine dyes in basic solvents. Chem. Phys. Lett. 1998;283:350–356. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Filippov A., Orädd G., Lindblom G. The effect of cholesterol on the lateral diffusion of phospholipids in oriented bilayers. Biophys. J. 2003;84:3079–3086. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(03)70033-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Widengren J., Thyberg P. FCS cell surface measurements—photophysical limitations and consequences on molecular ensembles with heterogenic mobilities. Cytometry A. 2005;68:101–112. doi: 10.1002/cyto.a.20193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sandén T., Persson G., Widengren J. Monitoring kinetics of highly environment sensitive states of fluorescent molecules by modulated excitation and time-averaged fluorescence intensity recording. Anal. Chem. 2007;79:3330–3341. doi: 10.1021/ac0622680. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]