Abstract

We report a novel affinity-based purification method for proteins expressed in Escherichia coli that uses the coordination of a heme tag to an l-histidine-immobilized sepharose (HIS) resin. This approach provides an affinity purification tag visible to the eye, facilitating tracking of the protein. We show that azurin and maltose binding protein are readily purified from cell lysate using the heme tag and HIS resin. Mild conditions are used; heme-tagged proteins are bound to the HIS resin in phosphate buffer, pH 7.0, and eluted by adding 200–500 mM imidazole or binding buffer at pH 5 or 8. The HIS resin exhibits a low level of nonspecific binding of untagged cellular proteins for the systems studied here. An additional advantage of the heme tag-HIS method for purification is that the heme tag can be used for protein quantification by using the pyridine hemochrome absorbance method for heme concentration determination.

Keywords: affinity tag, color tag, protein purification, protein quantification, heme c

Introduction

The addition of peptide and protein fusion tags to recombinant proteins is widely used in biochemical studies.1,2 Fusion tags exist for a variety of applications, including affinity purification, solubility enhancement, and protein detection.1–5 Affinity purification methods are popular because they can dramatically reduce purification time, often require few purification steps, and can be used to obtain greater than 90% purity with high yields.1,3,5 However, affinity-tagged proteins are purified using conditions (buffer, additives, etc.) specific to the fusion tag and not the protein of interest.2 Thus, no single affinity procedure can be used to purify every protein, resulting in the need for a wide variety of fusion tags and the continuing development of novel affinity purification methods.2 Recently, fusion tags detectable by the naked eye have been developed for continuous tracking of protein expression and purification.2 For instance, protein fusions based on the yellow human flavin mononucleotide-binding domain and the red mosquito cytochrome b5 have been developed.6 In addition, the Cherry™Express (Delphi Genetics) kit for fusing an 11-kDa heme protein that also allows for protein quantification is commercially available. These colored tags aid in visualization and quantification, but for affinity purification, additional tags are required.

In this study, we report a peptide fusion system based on the heme tag developed by Thöny-Meyer and coworkers7 that can be used for affinity purification, visual tracking of expressed protein throughout purification, protein quantification using absorption spectroscopy, and estimation of the protein's extinction coefficient at 280 nm ( ). The heme tag is a small peptide fusion tag that binds heme covalently to a protein on expression in Escherichia coli and has been used for visual tracking of protein expression and purification.7 This tagging strategy takes advantage of the bacterial cytochrome c (cyt c) maturation (ccm) apparatus in E. coli,8 which covalently adds the cysteines of a conserved Cys-X-X-Cys-His (CXXCH) motif to the two heme vinyl groups.9 The ccm system is composed of eight integral membrane proteins (ccmABCDEFGH) that face the periplasmic side of the cytoplasmic membrane.8 Thus, proteins carrying the peptide fusion must contain an amino-terminal signal sequence for translocation to the periplasmic space for covalent heme attachment.7 A complete understanding of the mechanism by which the cofactor is attached to the CXXCH motif by the ccm system is an active area of research.8 However, it has been shown that recognition for heme attachment depends on the presence of a CXXCH motif.9

). The heme tag is a small peptide fusion tag that binds heme covalently to a protein on expression in Escherichia coli and has been used for visual tracking of protein expression and purification.7 This tagging strategy takes advantage of the bacterial cytochrome c (cyt c) maturation (ccm) apparatus in E. coli,8 which covalently adds the cysteines of a conserved Cys-X-X-Cys-His (CXXCH) motif to the two heme vinyl groups.9 The ccm system is composed of eight integral membrane proteins (ccmABCDEFGH) that face the periplasmic side of the cytoplasmic membrane.8 Thus, proteins carrying the peptide fusion must contain an amino-terminal signal sequence for translocation to the periplasmic space for covalent heme attachment.7 A complete understanding of the mechanism by which the cofactor is attached to the CXXCH motif by the ccm system is an active area of research.8 However, it has been shown that recognition for heme attachment depends on the presence of a CXXCH motif.9

In this study, we make use of heme coordination chemistry and demonstrate that proteins tagged with five-coordinate heme will reversibly bind l-histidine immobilized to a sepharose framework, resulting in a highly pure protein sample after elution. Furthermore, we quantify expressed protein and estimate the  using standard heme quantification procedures without the need for proteolytically removing the tag.

using standard heme quantification procedures without the need for proteolytically removing the tag.

Results

Heme tag design, fusion plasmid construction, and protein expression

Previously, it was shown that heme tags could be constructed having both six- and five-coordination at the heme iron.7 The porphyrin provides four coordinating atoms through its pyrrole nitrogens, and the heme-binding CXXCH sequence supplies the His that occupies the fifth site. Tags that have a polyhistidine sequence (His-tag) after the CXXCH motif yield a six-coordinate heme iron with one of the His residues occupying the axial binding site to heme. The absence of the His-tag allows for a five-coordinate heme with an open site at iron available to bind exogenous ligands.

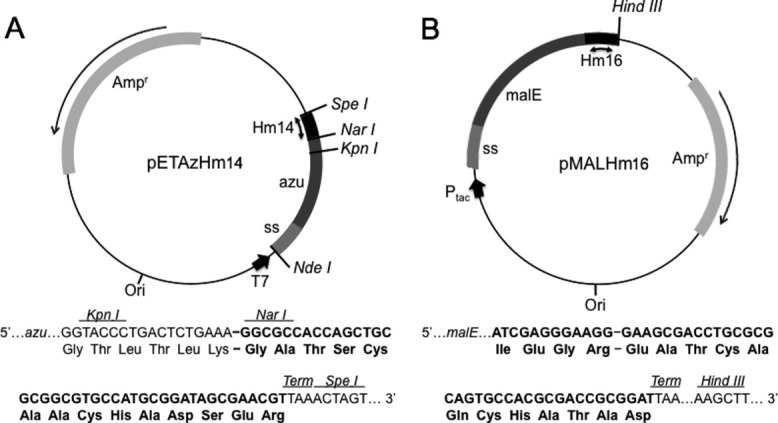

The model proteins used in this study are the blue copper protein Pseudomonas aeruginosa azurin (Az) and E. coli maltose binding protein (MBP). Table I lists the heme-tagged Az and MBP variants prepared in this study with their corresponding peptide fusion tag sequences and expected heme coordination. Expression vectors were constructed to express each variant with a carboxyl-terminal heme tag (Fig. 1). The commercial MBP construct used includes a carboxyl-terminal 12-amino acid spacer to which the amino terminus of the Hm16 tag was connected. The heme tags of the Az variants are directly attached to the protein carboxyl terminus. The five-coordinate heme tags of Az-Hm14 and MBP-Hm16 are first reported herein, while that of Az-MP301 was previously described.7 The expression vectors and the pEC8610 plasmid carrying the ccm gene array were cotransformed in E. coli for protein overexpression. For our five-coordinate heme tag designs (Hm14 and Hm16), polar amino acids were included to enhance water solubility. A six-coordinate His-tagged variant of Az-Hm14 (Az-Hm20) with seven histidines was prepared for comparison (Supporting Information Fig. 1). The bacterial pellets containing Az-Hm14, MBP-Hm16, and Az-MP301 were dark brown in color, and pellets containing Az-Hm20 exhibited a red color, consistent with overexpression of five- and six-coordinate heme proteins, respectively (Supporting Information Fig. 2).

Table I.

Heme-tagged Fusion Proteins with Corresponding Tag Amino Acid Sequences and Heme Iron Coordination

| Protein fusionsa | Heme-tag peptide sequenceb | Heme iron coordination |

|---|---|---|

| Az-Hm14 | GATSCAACHADSER | Five |

| Az-Hm20 | GATSCAACHADSE HHHHHHH | Six |

| MBP-Hm16c | IEGREATCAQCHATAD | Five |

| Az-MP301d | NSRYPAACLACHAIG | Five |

The heme tags developed in this study are abbreviated as Hm followed by the number of amino acids in the peptide. The MP301 tag was previously described.7

The heme attchement motifs are underlined.

MBP contains a 12 amino acid spacer that connects the carboxyl-terminus to the Hm16 tag.

Reported in Ref. 7.

Figure 1.

Expression of Az-Hm14 and MBP-Hm16. (A) pETAzHm14 expression vector carrying the azurin expression gene made up of the Az structural gene (azu) and native signal sequence (ss). The Hm14 sequence is shown in black between the NarI and SpeI restriction sites. (B) pMALHm16 plasmid carrying the MBP expression gene sequence made up of the MBP structral gene (malE) and native signal sequence (ss). The Hm16 sequence is shown in black.

Affinity purification of Az-Hm14 and MBP-Hm16

The ability of five-coordinate heme to reversibly bind exogenous ligands suggests that the heme tag could be exploited for affinity-based purification. Therefore, we prepared a sepharose resin that contains the amino acid l-histidine covalently coupled by a 14-atom spacer to immobilize the heme-tagged proteins. Histidine was chosen because it is a common heme ligand and is not expected to bind or react with most other biological molecules to any appreciable extent. Partially clarified brown-colored cellular extract containing Az-Hm14 loaded on the l-histidine-immobilized sepharose (HIS) resin resulted in a red band at the top of the medium when washed with 50 mM sodium phosphate (NaPi) pH 7.0 (Fig. 2C). The red color suggests coordination of histidine to heme iron. A distinct green band separated from the red and eluted with approximately 1–1.3 column volumes (CV) of binding buffer. The green color of the band is likely due to the presence of degraded heme from activity of E. coli heme oxygenases.11 The effect of pH was investigated with 50 mM NaPi (binding buffer) at pH values of 6.5–7.5, identified to be optimal for binding. Binding buffer containing 200–500 mM imidazole, at pH 5 or 8 was found to elute Az-Hm14 from the HIS resin (Fig. 2C). Binding buffer at pH 5 results in the histidines of the resin being protonated and unavailable to coordinate heme iron, while at pH 8 we propose that hydroxide ions compete as ligands to heme iron. Crude periplasmic extract containing MBP-Hm16 behaved similarly when loaded on the HIS resin using the same binding buffer as described for Az-Hm14. MBP-Hm16 was eluted using binding buffer supplemented with imidazole as described for Az-Hm14. Clarified cellular extract containing Az-MP301 (prepared as described for Az-Hm14) remained brown in color with the addition of binding buffer when loaded on the HIS resin. The brown band eluted with approximately 1.0 CV of binding buffer, indicating that the protein did not bind the HIS resin.

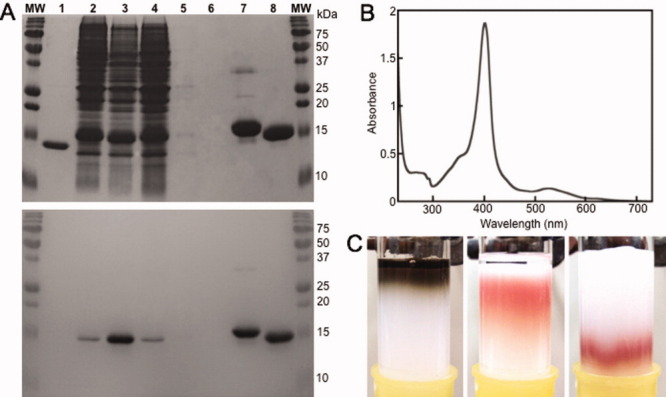

Figure 2.

Purification of Az-Hm14 using the HIS resin. (A) 15% SDS-PAGE analysis of Az-Hm14 and Az-Hm20 after purification, developed in Coomassie (top) and heme stain (bottom). The samples loaded into both gels were derived from the same purification experiment and the gels were processed and stained in parallel. Lane MW: molecular weight marker, 1: purified Az, 2: crude cellular extract from Az-Hm14 expression, 3: partially clarified cellular extract from Az-Hm14 expression, 4: fraction taken from HIS column after loading extract followed by 0.9 CV of binding buffer (50 mM NaPi, pH 7.0), 5: fraction taken after 2.0 CV, 6: blank, 7: Az-Hm20 purified using Ni(II) IMAC procedure, 8: Az-Hm14 purified using HIS column. (B) Absorption spectrum of Az-Hm14 in 25 mM NaPi pH 7.0 purified using the HIS resin. (C) Loading partially clarified lysate containing Az-Hm14 on the HIS resin (left), Az-Hm14 binding to the HIS resin after the addition of 2 CV of binding buffer (middle), and after 1.5 CV of binding buffer containing 300 mM imidazole (right).

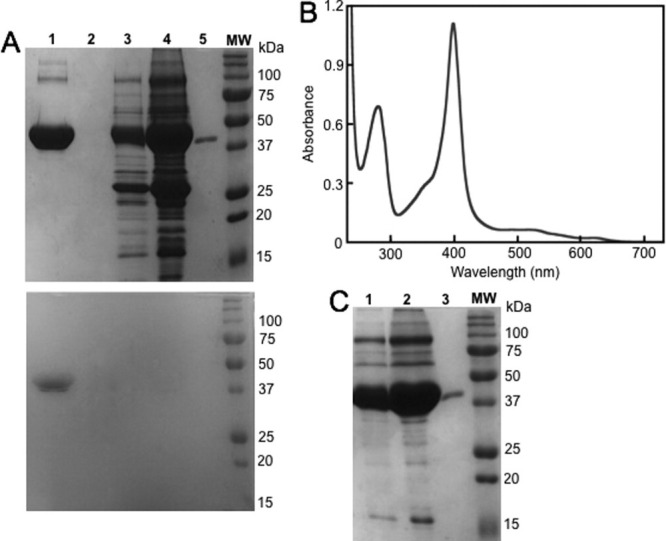

Purity of the Az-Hm14 and MBP-Hm16 samples was assessed by SDS-PAGE of fractions taken during the purification process. The red fraction eluted using imidazole yielded a single band at molecular weight ∼15 kDa for Az-Hm14 (lane 8, Fig 2A) and a single band at ∼45 kDa for MBP-Hm16 (lane 1, Fig. 3A) visualized using both Coomassie and heme stain. A comparison of the crude cellular lysate containing Az-Hm14 before and after partial clarification is shown in lanes 2 and 3 of Figure 2A, showing little purity difference. Lane 4 of Figure 3A is the crude periplasmic extract containing MBP-Hm16. The results of elution of binding buffer after loading heme-tagged proteins are shown in lanes 4 and 5 of Figure 2A for Az-Hm14 purification and lane 3 of Figure 3A for MBP-Hm16 purification. The proteins that elute at 0.9 CV of binding buffer are visualized in lane 4 (Fig. 2A) for Az-Hm14 purification and lane 3 (Fig. 3A) for MBP-Hm16 purification. The ultraviolet–visible (UV–vis) spectra of Az-Hm14 (Fig. 2B) and MBP-Hm16 (Fig. 3B) in 50 mM NaPi, pH 7.0 purified using the HIS resin show a Soret band at 401 and 398 nm, respectively, values consistent with five-coordinate microperoxidases.12 Purified Az-Hm14 and MBP-Hm16 yields of 7 and 0.8 mg/L culture, respectively, were obtained using the HIS column method. MBP-Hm16 yield was lower than that of Az-Hm14 due to the difference in expression vector and a higher level of degradation of the heme cofactor.

Figure 3.

Purification of MBP-Hm16 using the HIS resin. (A) 10% SDS-PAGE analysis of MBP-Hm16 purification, developed in Coomassie (top) and heme stain (bottom). The samples loaded into both gels were derived from the same purification experiment, and the gels were processed and stained in parallel. Lane MW: molecular weight marker, 1: MBP-Hm16 purified using the HIS column, 2: blank, 3: fraction taken from HIS column after loading extract followed by 0.9 CV of binding buffer, 4: crude periplasmic extract including MBP-Hm16, 5: purified MBP (New England BioLabs). (B) Absorption spectrum of MBP-Hm16 in 25 mM NaPi pH 7.0 purified using the HIS resin. (C) 10% SDS-PAGE analysis of MBP-Hm16 purified using the amylose method. 1: Fraction taken from HIS column after loading amylose-purified MBP-Hm16 (lane 2) followed by 0.9 CV of binding buffer, 2: MBP-Hm16 purified using the amylose method. The full-length gel is shown in shown in Supporting Information Figure 4.

Az-Hm14 and MBP-Hm16 were further characterized after purification by exploiting their abilities to bind native ligands/metals. Az is a copper-binding protein that exhibits a distinct blue color due to a Cys(S)-to-Cu(II) charge-transfer band at 625 nm on coordinating Cu(II).13 MBP is widely used as an affinity fusion tag that binds immobilized amylose resins and maltose.14 Pure Az-Hm14 was shown to bind Cu(II) after the addition of CuSO4 by monitoring the appearance of the charge-transfer band at 625 nm (Supporting Information Fig. 3). As expected, the solution containing Az-Hm14 exhibited a color change from red to brown due to the blue color exhibited by Cu(II)Az. To test the ligand-binding properties of MBP-Hm16, crude periplasmic extract containing MBP-Hm16 was loaded on amylose resin. MBP-Hm16 formed a band at the top of the column and eluted after the addition of maltose, confirming that the protein retained the ability to bind amylose and maltose (Supporting Information Fig. 4). After elution from the amylose resin, MBP-Hm16 was loaded onto the HIS medium and a red band formed at the top of the column, confirming that the MBP-Hm16 has affinity for both types of media (Supporting Information Fig. 4).

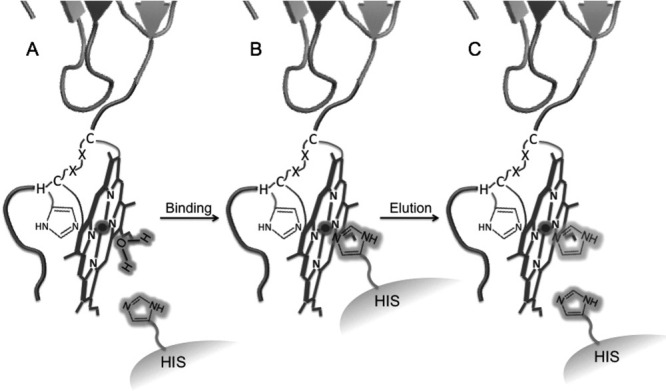

To verify the mode of HIS medium binding, pure Cu(II)-Az, Az-Hm20, horse heart myoglobin, and horse heart cyt c were each loaded on the HIS column in 50 mM NaPi, pH 7.0. Each of the four proteins eluted within 1 CV of binding buffer, indicating no appreciable affinity for the HIS resin. The lack of Cu(II)Az binding verifies that Az-Hm14 affinity for the column is specific to the heme tag and not the Az protein structure. Heme burial in the hydrophobic interior of myoglobin, a five-coordinate b-type heme protein, and the saturated coordination shell of cyt c and Az-Hm20 heme presumably prevent binding to the HIS column. These control experiments indicate that a five-coordinate, solvent-exposed heme is required for binding the HIS column. To test this requirement, microperoxidase-8 (MP8), a small five-coordinate heme peptide,15 was loaded on the HIS resin in 50 mM NaPi, pH 7.0. MP8 bound to the top of the column and was eluted using the same procedures as for the heme-tagged proteins, verifying heme iron–histidine coordination as the mechanism of binding (Fig. 4).

Figure 4.

Schematic of heme-tagged protein purifcation using the HIS resin. (A) Five-coordinate heme-tagged protein loaded onto to the HIS resin coordinating water or weakly coordinating another exogenous ligand. (B) Heme-tag binding to HIS column through coordination of immobilized histidine of the medium (HIS) and the iron of the heme tag. (C) Competitive elution of the protein by addition of free imidazole. Elution by low (pH 5) or alkaline (pH 8) buffer was also successfully used to elute the protein from the HIS resin.

To compare the HIS purification method with commercial affinity purification procedures, Az-Hm20 was purified using the His-tag-immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) method and MBP-Hm16 was purified using the MBP-amylose method. Both purification methods were carried out according to the manufacturer's protocol. As shown in Figure 2A, contaminants are visible for the Az-Hm20 purification using the IMAC procedure (lane 7), whereas Az-Hm14 purified on the HIS column appears to be contaminant-free (lane 8). We observed significantly greater contamination by E. coli proteins after purification of MBP-Hm16 using the amylose purification method (lane 2, Fig. 3C) than with the HIS method (lane 1, Fig. 3A). Additionally, a second round of purification of MBP-Hm16 using the HIS resin (after purification on amylose resin) removed some of these contaminating proteins (lane 1, Fig. 3C) and resulted in a final purity similar to that using the HIS method alone (compare lane 1, Fig. 3A and Supporting Information Fig. 4).

Quantification of heme-tagged proteins

We examined the possibility of using the absorption properties of the heme tag to quantify the protein and to determine  for nontagged Az and MBP. The concentrations of heme present in the sample can be determined using the pyridine hemochrome absorbance (PHA) method, which relies on the known extinction coefficient for c-type heme in the presence of excess sodium hydroxide and pyridine (ɛPHA).16 This value can be used to calculate the concentration of proteins carrying c-type heme, as it has been shown to be independent of the polypeptide chain.16

for nontagged Az and MBP. The concentrations of heme present in the sample can be determined using the pyridine hemochrome absorbance (PHA) method, which relies on the known extinction coefficient for c-type heme in the presence of excess sodium hydroxide and pyridine (ɛPHA).16 This value can be used to calculate the concentration of proteins carrying c-type heme, as it has been shown to be independent of the polypeptide chain.16

Az-Hm14 and MBP-Hm16 Fe(II) PHA spectra gave the characteristic 550- and 521-nm bands in the visible region, indicating proper incorporation of c-type heme to the tag (Supporting Information Fig. 5). To obtain  using the heme tag, the contribution of heme to ɛ280 (

using the heme tag, the contribution of heme to ɛ280 ( ) must be subtracted from that of the heme-tagged proteins (

) must be subtracted from that of the heme-tagged proteins ( ). The value of

). The value of  was determined (9.82 mM−1 cm−1) using MP8 as a model system for heme-only absorbance at 280 nm. MP8 is a heme peptide from horse cyt c corresponding to residues 14–21 with heme bound covalently. It does not contain aromatic residues or disulfide bonds and has a five-coordinate heme structure, making it a suitable model system.15 To prevent dimer formation and to reduce the effects of buffer and pH on results, absorption measurements were taken in the presence of excess sodium cyanide that strongly binds the open coordination site of the heme iron. Using the concentrations of heme-tagged proteins and MP8 determined from ɛPHA,

was determined (9.82 mM−1 cm−1) using MP8 as a model system for heme-only absorbance at 280 nm. MP8 is a heme peptide from horse cyt c corresponding to residues 14–21 with heme bound covalently. It does not contain aromatic residues or disulfide bonds and has a five-coordinate heme structure, making it a suitable model system.15 To prevent dimer formation and to reduce the effects of buffer and pH on results, absorption measurements were taken in the presence of excess sodium cyanide that strongly binds the open coordination site of the heme iron. Using the concentrations of heme-tagged proteins and MP8 determined from ɛPHA,  for Az-Hm14, MBP-Hm16, and MP8 in the presence of CN− were determined from the corresponding absorbance values in NaPi, pH 7.0. To determine

for Az-Hm14, MBP-Hm16, and MP8 in the presence of CN− were determined from the corresponding absorbance values in NaPi, pH 7.0. To determine  for Az and MBP,

for Az and MBP,  was subtracted from

was subtracted from  for the corresponding heme-tagged proteins. Table II shows the results of these calculations compared with a range of reported literature values of

for the corresponding heme-tagged proteins. Table II shows the results of these calculations compared with a range of reported literature values of  for Az17–19 and MBP.20–22

for Az17–19 and MBP.20–22

Table II.

Values for  for Az and MBP Determined Using the Heme Tag Variants Az-Hm14-CN and MBP-Hm16-CN

for Az and MBP Determined Using the Heme Tag Variants Az-Hm14-CN and MBP-Hm16-CN

Discussion

We have demonstrated that the heme tags Hm14 and Hm16 can simultaneously serve as affinity tags for protein purification (Fig. 4), for visual tracking of the protein fusion throughout expression and purification, and for protein quantification and estimation of  . As an affinity purification tag, the heme tag gives highly favorable results. Nonspecific adsorption of cellular proteins to affinity resins is reported with many commonly used purification procedures.1,3,4 We have shown that the HIS resin exhibits a low degree of nonspecific binding, circumventing the need for supplementing the binding buffer with high concentrations of salts or eluting agents, thus simplifying the purification procedure and allowing for mild column loading conditions. This is exemplified by comparing the purification of Az-Hm14 using the HIS column with that of Az-Hm20 by the IMAC method. Az-Hm20 was purified by IMAC using an optimized binding buffer of 25 mM NaPi pH 7.8 in addition to 1M NaCl and 60 mM imidazole to minimize nonspecific binding of cellular proteins to the affinity matrix. The concentrations of both NaCl and imidazole in the binding buffer necessary for obtaining pure protein can vary for the IMAC method1,23 and must be optimized. Even after optimization, some undesired binding of nontagged E. coli proteins to the IMAC column was observed. The poor purity obtained when using MBP as an affinity tag with the amylose resin has been documented, and recently His-tagged MBP fusions were introduced to gain a higher degree of purity by using affinity purification by IMAC while exploiting the solubility enhancing properties of MBP.24 The low nonspecific binding of proteins to the HIS resin suggests that this method could also find wide application in combination with other existing fusion tags that enhance solubility and increase overall yield.

. As an affinity purification tag, the heme tag gives highly favorable results. Nonspecific adsorption of cellular proteins to affinity resins is reported with many commonly used purification procedures.1,3,4 We have shown that the HIS resin exhibits a low degree of nonspecific binding, circumventing the need for supplementing the binding buffer with high concentrations of salts or eluting agents, thus simplifying the purification procedure and allowing for mild column loading conditions. This is exemplified by comparing the purification of Az-Hm14 using the HIS column with that of Az-Hm20 by the IMAC method. Az-Hm20 was purified by IMAC using an optimized binding buffer of 25 mM NaPi pH 7.8 in addition to 1M NaCl and 60 mM imidazole to minimize nonspecific binding of cellular proteins to the affinity matrix. The concentrations of both NaCl and imidazole in the binding buffer necessary for obtaining pure protein can vary for the IMAC method1,23 and must be optimized. Even after optimization, some undesired binding of nontagged E. coli proteins to the IMAC column was observed. The poor purity obtained when using MBP as an affinity tag with the amylose resin has been documented, and recently His-tagged MBP fusions were introduced to gain a higher degree of purity by using affinity purification by IMAC while exploiting the solubility enhancing properties of MBP.24 The low nonspecific binding of proteins to the HIS resin suggests that this method could also find wide application in combination with other existing fusion tags that enhance solubility and increase overall yield.

The lack of binding to the HIS resin by the Az-MP301 variant suggests that the amino acid composition of the heme tag plays a role in determining the efficiency of binding. The MP301 heme tag contains a proline residue in the linker, and Braun et al.7 suggest that this residue may aid in the recognition of the heme attachment motif by the ccm apparatus. Proline residues in proteins have the most restricted rotational freedom of any other amino acid,25 making it possible that the MP301 tag is locked into an unfavorable orientation for binding the HIS resin. Conversely, our tag designs include glycine in the linker, an amino acid that can access the widest range of rotational space available when compared with the other amino acids.25 Thus, choosing glycine in combination with polar amino acids for the heme tag linker may be necessary for proper binding to the HIS resin. The tags presented here were all appended to the carboxyl terminus of the proteins. It is reasonable to expect that amino-terminal tags could be constructed in a similar manner.

Purification yields obtained for Az-Hm14 using the method in this study are similar to or higher than those reported for several of the commonly used affinity purification methods. For example, typical yields reported for glutathione-S-transferase, intein–chitin binding domain, and the biotin carboxyl carrier protein affinity methods are 10, 0.5–5, and 1–5 mg/L of bacterial culture, respectively.26 Although MBP-Hm16 yields (0.8 mg/L) are lower than Az-Hm14 (7 mg/L), they fall within this range. The yields we report for AzHm-14 are similar to those of several cyts c overexpressed in E. coli, with the latter having a range of 1–12 mg/L.27–29 The extent of heme attachment to the CXXCH motif has been shown not to depend on the amount of apoprotein having a heme binding motif in the periplasm.30 To explain this observation, it has been suggested that the availability of free heme transported to the periplasm by an unknown mechanism may determine the yield of protein modified with heme.30 Thus, it is expected that the maximum yield of pure protein obtainable using the heme tag-HIS method will be similar to that of the cyts c currently reported, which we demonstrate with Az-Hm14. This suggests that the yield of high-expression proteins (higher than the availability of heme) will be lowered when heme tagged. However, in this study, the yields we obtain for heme-tagged proteins and those obtained for cyts c reported in the literature are sufficient for extensive biophysical characterization.

Protein concentration determination is frequently used during the purification process. Many procedures exist for protein quantification, with all having their specific advantages and limitations.31,32 Colorimetric protein quantification assays, including the Bradford and Lowry methods, are frequently used due to their sensitivity and quick procedures.31,33 However, accuracy of colorimetric methods depends on the protein and these methods require standards for obtaining actual concentration values.31,32 The PHA method is a colorimetric technique for quantifying proteins containing intrinsic heme and is the most used method for this purpose.34 We have shown here that the purification of proteins using the heme-tag-HIS method offers the additional advantage in that the proteins can be easily quantified using the PHA. Unlike other colorimetric techniques, the PHA method does not require standardization and depends only on the presence of heme, thus lending the PHA methods to use any protein containing a heme tag. In addition, we have estimated  for Az and MBP using the concentration determined from the PHA without removing the heme tag from Az-Hm14 and MBP-Hm16. The results of this pilot study show that

for Az and MBP using the concentration determined from the PHA without removing the heme tag from Az-Hm14 and MBP-Hm16. The results of this pilot study show that  we measure for Az and MBP are comparable with the higher values in the literature for Az and MBP, and thus represent a method useful for estimating

we measure for Az and MBP are comparable with the higher values in the literature for Az and MBP, and thus represent a method useful for estimating  for Az and MBP.

for Az and MBP.

Although using the heme tag for protein purification and quantification has many advantages over other methods, it also has some limitations. Because the HIS method for purification requires ligand–metal coordination to bind the protein to the chromatography matrix, additives that interfere with metal–imidazole binding should be avoided. Note that this limitation applies also to the His-tag-IMAC method. In addition, the appearance of a green band that did not bind the HIS resin suggests that some degradation of the heme tag by E. coli heme oxygenases occurs, which can lower the yield of purified heme-tagged proteins. The lower yields of MBP-Hm16 (and higher degree of green product) compared with that of Az-Hm14 may be explained by the additional 12-amino acid linker present on the MBP construct that may increase accessibility of the heme to heme oxygenases. Strategies to avoid heme degradation are to limit the amount of oxygenation of the culture and to supplement the growth with metalloporphyrins known to inhibit heme oxygenase activity.35,36 The amount of degraded heme observed in this study differed between the tags used, suggesting that further optimization could diminish or eliminate this issue. Another disadvantage is the requirement of two plasmids and two antibiotics for selection when expressing heme-tagged protein. The main limitations of the PHA method for protein quantification are that the samples cannot be recovered, and that a sensitive spectrophotometer is required.34

In summary, we have developed a novel and facile affinity purification and quantitation method for proteins that can be expressed in E. coli. In addition, we have shown that a metal-containing affinity tag that uses coordination to a ligand-immobilized chromatography resin can be used for protein purification. Unlike the His-tag-IMAC and MBP-amylose methods, we have shown that nonspecific binding of untagged proteins does not present a significant problem for our heme tag-HIS method for the proteins used in this pilot study. Additionally, the heme tag's strong visible absorbance allows for continuous tracking, detecting, and quantifying of any recombinant protein expressed in E. coli.

Materials and Methods

Plasmid construction

The pET-9a plasmid (Novagen) carrying the P. aeruginosa Az structural gene (azu) with preceding signal sequence for translocation to the periplasm was provided by Prof. Yi Lu as a gift. The complete signal sequence and azu, minus the last four codons, were excised from pET-9a by digestion with NdeI and KpnI and cloned into pET-17b, resulting in the pET-17b(azu) vector. The 78-bp Hm14 sequence (5′-ATGAAAGGTACCCTGACTCTGAAAGGCGCCACCA GCTGCGCGGCGTGCCATGCGGATAGCGAACATTA AACTAGT-3′) was synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies and amplified by PCR using the primers Hm14 Fwd (5′-ATGAAAGGTACCCTGACTCT GAAAGGCGCC-3′) and Hm14 Bwd (5′-ATCAGTT TAATGTTCGCTATGCGCATGCG-3′). The fragment, which includes the last four codons of azu followed by the heme tag sequence, was inserted into pET-17b(azu) using the KpnI and SpeI restriction sites, resulting in the complete Az-Hm14 fusion in pET-17b, pETAzHm14. Our initial Hm14 tag design included a His residue as the last amino acid of the tag, which was intended to provide the sixth axial ligand to the heme iron. However, this variant had five-coordinate heme according to UV–vis analysis, and thus a heme tag with a carboxyl-terminal polyhistidine sequence was used to achieve six-coordinate heme (see below). In the final Hm14 construct used in this work, the His in the original tag design was mutated to an arginine residue to ensure an unobstructed coordination site for ligand binding using the mutagenic primers H14*RP1 (5′-GCCATGCGGATAGCGAACGTTAAACTAGTAACGG CCGC-3′) and H14*RP2 (5′CGCGCCGTTACTAGTT TAACGTTCGCTATCCGCATGGC-3′) using QuikChange (Stratagene) methods. The resulting plasmid is referred to as pETASAHm14 and the tag sequence as Hm14.

The pETAzHm20 vector coding for the Az-Hm20 variant was constructed as described for pETAzHm14 vector except that the Hm20 sequence was used instead of Hm14. The 93-bp Hm20 sequence (5′-ATGAAAGGTACCCTGACTCTGAAAGG CGCCACCAGCTGCGCGGCGTGCCATGCGGATAGC GAACATCATCATCATCATCATCATTAAACTAGT-3′) was synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies and amplified by PCR using the primers Hm20 Fwd (5′-ATGAAAGGTACCCTGACTCTGAAAGGCGCC-3′) and Hm20 Bwd (5′-ACTAGTTTAATGATGATGAT GATGATGATGTTCGCTATCCGC-3′). The pMALHm 16 vector coding for MBP-Hm16 is derived from the pMALHm35 vector constructed earlier in our laboratory (described below).

The pETAzHm-MP301 vector coding for the Az-MP301 variant (incorporating the heme tag sequence reported by Thöny-Meyer and coworkers)7 used in this study was constructed as described for the pETAzHm14 vector except that the MP301 sequence was used instead of Hm14. The 78-bp MP301 sequence (5′-ATGAAAGGTACCCTGACTGT GAAAAACAGCCGTTATCCGGCGGCGTGCCTGGCG TGCCATGCGATTGGCTAAACTAGT-3′) was synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies and amplified by PCR using the primers MP301 Fwd (5′-ATGAAA GGTACCCTGACTCTGAAAAACAGCCG-3′) and MP301 Bwd (5′-ACTAGTTTAGCCAATCGCATGGCACGCCA GG-3′).

To prepare pMALHm35, the 108-bp Hm31 tag sequence carrying three heme attachment motifs (5′-GAAGCGACCTGCGCGCAGTGCCACGCGACCGCG GATGCGTGCGCGCAGTGCCACGCGACCGCGGAT GCGTGCGCGCAGTGCCACACCGCGGAATAAAAG CTTATATAT-3′) was synthesized by Integrated DNA Technologies and amplified by PCR using the primers Hm31 Fwd (5′-GAAGCGACCTGCGCGCAGTG CCACGCGACC-3′) and Hm31 Bwd (5′-ATATATAAG CTTTTATTCCGCGGTGTGGCACTGCGCGC-3′). The Hm31 fragment was inserted into pMALp4x (New England BioLabs) using the XmnI and HindIII restriction sites as recommended by the manufacturer, resulting in the pMALHm35 plasmid. The parent pMALp4x vector is composed of the MBP structural gene (malE) and native signal sequence with a carboxyl-terminal 12 amino acid spacer terminating with a factor Xa (fXa) protease site sequence. The fXa sequence codes for four amino acids (IEGR), which we include as part of the overall tag design, resulting in a 35-amino acid peptide tag (Hm35) when Hm31 is fused with MBP. pMALHm35 was constructed for a related project. For this study, an ochre stop codon was introduced at position 17 of the Hm35 sequence in pMALHm35 using the mutagenic primers MBPstp1 (5′-CACGCGACCGCGGAT TAATGCGCGGAGTGCCACG-3′) and MBPstp2 (5′-C GTGGCACTGCGCGCATTAATCCGCGGTCGCGTG-3′) using QuikChange (Stratagene) methods, resulting in the pMALHm16 plasmid. The final construct resulted in the malE gene fused with a 16-amino acid peptide tag with one heme attachment motif. Expression plasmids for heme-tagged proteins are available on request.

Protein overexpression and partial clarification

The expression vectors carrying the heme-tagged Az variants used in this study were individually transformed along with pEC86 (carrying ccmABCDEFGH)10 into BL21* (DE3) E. coli (Invitrogen) and grown with shaking (160–170 rpm) at 25–28°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium containing 50 mg/L of ampicillin (Amp) and chloramphenicol (CM). pEC86 was provided by Linda Thöny-Meyer as a gift. The cells were grown for 16 h and harvested by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm 4–5 h after induction with 0.4 mM isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG). The cell pellets were stored at −20°C until further use. The cellular extracts containing each heme-tagged Az variant used in this study were prepared using the same procedure. Briefly, the extracts containing the heme-tagged Azs and other cellular proteins were extracted by suspending the cell paste in 50 mM Tris-HCl, 4 mg/mL lysozyme, and 1.5 units/mL DNAase I (Sigma), pH 8.0. The lysis suspension was incubated for 1 h at 30°C followed by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm for 20 min to separate the extract from the cellular components. The supernatant pH was increased to 8.8–9.0 using 1M NaOH and loaded on a diethylaminoethyl (DEAE) sepharose (GE Healthcare) pre-equilibrated with 20 mM Tris, pH 8.8. The column was washed with 10 CV of the same buffer and eluted with 20 mM Tris, pH 8.8, 200 mM NaCl buffer. Alternatively, the protein was eluted from the column using a gradient of 10–50% 20 mM Tris–HCl, 200 mM NaCl, pH 8.8. The eluted extract was concentrated in an Amicon® (Millipore) to 4–10 mL and exchanged in 50 mM sodium phosphate buffer, pH 7.0 using a PD-10 desalting column (GE Healthcare) before purification using the HIS or IMAC resins. The same transformation procedure and E. coli strain used for the expression of heme-tagged Az constructs were used for expressing MBP-Hm16 transcribed from the pMALHm16 vector. The bacterial cells were grown with shaking (150 rpm) at 37°C in LB medium containing 50 mg/L Amp, 50 mg/L CM, and 2 g/L d(+)-glucose (which represses an E. coli amylase responsible for degrading the amylose resin) for 7–8 h and harvested 17 h after induction with 0.4 mM IPTG at 37°C by centrifugation at 10,000 rpm. The cell pellets were stored at −20°C until further use. The periplasmic extract was isolated using a cold osmotic shock protocol followed as described by Riggs.37 The periplasm was concentrated and exchanged into the appropriate binding buffer as described for the heme-tagged Az variants.

Purification of Az-Hm14 and MBP-Hm16 using the HIS resin

The HIS resin was prepared by reacting 25 mL of NHS-activated Sepharose 4 Fast Flow (GE Healthcare) resin with a histidine coupling buffer [10 mg/mL l-histidine (Sigma), 20 mM NaHCO3, 0.5M NaCl, pH 8.3]. After coupling, the HIS resin was loaded into a 2.5 × 10 cm2 glass column (BioRad). Alternatively, a prepacked 5-mL HiTrap™ NHS-activated HP column (GE Healthcare) was coupled with histidine using the histidine coupling buffer. The coupling reaction and subsequent cleanup used for both column types were performed as recommended by the manufacturer. A flow rate of ∼0.5 mL/min was used when operating both columns containing the HIS resin. Partially clarified lysate concentrated between 3 and 5 mL and containing Az-Hm14 was loaded onto 25 mL of HIS resin for each purification run followed by 2–3 CV of 50 mM NaPi pH 7.0 (binding buffer) before eluting with binding buffer containing 200, 300, or 500 mM imidazole, binding buffer with a pH adjusted to 5.0, or 8.0. The procedure for purifying Az-Hm14 using the 5-mL prepacked HIS resin was followed as described for using the 25-mL column, except that 0.5–1 mL of clarified lysate was added. After elution, the imidazole was readily removed from the protein using a PD-10 desalting column equilibrated in binding buffer at pH 4.5. The purification of MBP-Hm16 using the 25-mL HIS resin was followed as described for Az-Hm16. MBP-Hm16 was eluted from the HIS resin using binding buffer containing 300 mM imidazole.

Absorption spectroscopy and pyridine hemochrome assay

UV–vis absorption spectra were taken on a Shimadzu UV-2401PC spectrophotometer at room temperature. The pyridine hemochrome samples were prepared as follows: 80 μL stock protein solution (dissolved in 50 mM NaPi, pH 7.0), 910 μL pyridine solution (100 mM NaOH, 20% v/v pyridine, 50 mM NaPi), 10 μL of freshly prepared saturated dithionite solution (>1.0M sodium dithionite, 50 mM NaPi). Each sample was prepared in triplicate and the spectra were taken immediately after addition of the dithionite solution. The concentration of protein was calculated using the extinction coefficient for c-type heme in pyridine buffer of 30.27 mM−1 cm−1 at 550 nm as reported by Berry and Trumpower.16 The average concentration of the reduced PHA samples was used to calculate extinction coefficients at different wavelengths for the spectra of the oxidized samples. Oxidized samples without exogenous ligand to heme were prepared as described above for the PHA samples, except that 920 μL of 50 mM NaPi, pH 7.0 was used instead of the pyridine and dithionite solutions. Cyanide-ligated derivatives of the samples were prepared by adding 60–70 mM NaCN to the oxidized samples, with the pH adjusted to 7.1 using 1M HCl. The stock protein solutions were oxidized with excess K3[Fe(CN)6] and exchanged in 50 mM NaPi, pH 7.0 using a PD-10 desalting column (GE-Healthcare) before any samples were prepared.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank E. DeCoste (University of Rochester) for the MP8 samples and the pMALHm35 plasmid, M. McLaughlin (University of Rochester) for supplying the pure Cu(II)-Az, L. Thöny-Meyer (Institut für Mikrobiologie, ETH Hönggerberg) for the pEC86 vector, and Y. Lu (University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign) for the plasmid encoding Az.

References

- 1.Terpe K. Overview of tag protein fusions: from molecular and biochemical fundamentals to commercial systems. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2003;60:523–533. doi: 10.1007/s00253-002-1158-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chelur D, Unal O, Scholtyssek M, Strickler J. Fusion tags for protein expression and purification. BioPharm Int. 2008;21(6 Suppl):38–46. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Nilsson J, Stahl S, Lundeberg J, Uhlen M, Nygren PA. Affinity fusion strategies for detection, purification, and immobilization of recombinant proteins. Protein Expr Purif. 1997;11:1–16. doi: 10.1006/prep.1997.0767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arnau J, Lauritzen C, Petersen GE, Pedersen J. Current strategies for the use of affinity tags and tag removal for the purification of recombinant proteins. Protein Expr Purif. 2006;48:1–13. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2005.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lichty JJ, Malecki JL, Agnew HD, Michelson-Horowitz DJ, Tan S. Comparison of affinity tags for protein purification. Protein Expr Purif. 2005;41:98–105. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2005.01.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Finn RD, Kapelioukh L, Paine MJI. Rainbow tags: a visual tag system for recombinant protein expression and purification. Biotechniques. 2005;38:387–392. doi: 10.2144/05383ST01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Braun M, Rubio IG, Thöny-Meyer L. A heme tag for in vivo synthesis of artificial cytochromes. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2005;67:234–239. doi: 10.1007/s00253-004-1804-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kranz RG, Richard-Fogal C, Taylor JS, Frawley ER. Cytochrome c biogenesis: mechanisms for covalent modifications and trafficking of heme and for heme-iron redox control. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2009;73:510–528. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00001-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Allen JWA, Ferguson SJ. What is the substrate specificity of the system I cytochrome c biogenesis apparatus? Biochem Soc Trans. 2006;34:150–151. doi: 10.1042/BST0340150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arslan E, Schulz H, Zufferey R, Kunzler P, Thony-Meyer L. Overproduction of the Bradyrhizobium japonicum c-type cytochrome subunits of the cbb3 oxidase in Escherichia coli. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;251:744–747. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9549. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Suits MDL, Jaffer N, Jia ZC. Structure of the Escherichia coli O157:H7 heme oxygenase ChuS in complex with heme and enzymatic inactivation by mutation of the heme coordinating residue His-193. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:36776–36782. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M607684200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lombardi A, Nastri F, Pavone V. Peptide-based heme-protein models. Chem Rev. 2001;101:3165–3189. doi: 10.1021/cr000055j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mizoguchi TJ, Dibilio AJ, Gray HB, Richards JH. Blue to type-2 binding: copper(II) and cobalt(II) derivatives of a Cys112Asp mutant of Pseudomonas aeruginosa azurin. J Am Chem Soc. 1992;114:10076–10078. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Srinivasan U, Bell JA. A convenient method for affinity purification of maltose binding protein fusions. J Biotechnol. 1998;62:163–167. doi: 10.1016/s0168-1656(98)00058-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marques HM. Insights into porphyrin chemistry provided by the microperoxidases, the haempeptides derived from cytochrome c. Dalton Trans. 2007:4371–4385. doi: 10.1039/b710940g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Berry EA, Trumpower BL. Simultaneous determination of hemes-a, hemes-b, and hemes-c from pyridine hemochrome spectra. Anal Biochem. 1987;161:1–15. doi: 10.1016/0003-2697(87)90643-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vandekamp M, Hali FC, Rosato N, Agro AF, Canters GW. Purification and characterization of a nonreconstitutable azurin, obtained by heterologous expression of the Pseudomonas aeruginosa azu gene in Escherichia coli. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1990;1019:283–292. doi: 10.1016/0005-2728(90)90206-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Pozdnyakova I, Guidry J, Wittung-Stafshede P. Studies of Pseudomonas aeruginosa azurin mutants: cavities in beta-barrel do not affect refolding speed. Biophys J. 2002;82:2645–2651. doi: 10.1016/S0006-3495(02)75606-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Naro F, Tordi MG, Giacometti GM, Tomei F, Timperio AM, Zolla L. Metal binding to Pseudomonas aeruginosa azura kinetic investigation. Z Naturforsch (C) 2000;55:347–354. doi: 10.1515/znc-2000-5-609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Raghava S, Aquil S, Bhattacharyya S, Varadarajan R, Gupta MN. Strategy for purifying maltose binding protein fusion proteins by affinity precipitation. J Chromatogr A. 2008;1194:90–95. doi: 10.1016/j.chroma.2008.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gilardi G, Mei G, Rosato N, Agro AF, Cass AEG. Spectroscopic properties of an engineered maltose binding protein. Protein Eng. 1997;10:479–486. doi: 10.1093/protein/10.5.479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Medintz IL, Goldman ER, Lassman ME, Mauro JM. A fluorescence resonance energy transfer sensor based on maltose binding protein. Bioconjugate Chem. 2003;14:909–918. doi: 10.1021/bc020062+. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bornhorst JA, Falke JJ, Purification of proteins using polyhistidine affinity tags . Applications of chimeric genes and hybrid proteins, Part A. San Diego: Academic Press Inc.; 2000. pp. 245–254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nallamsetty S, Waugh DS. A generic protocol for the expression and purification of recombinant proteins in Escherichia coli using a combinatorial His6-maltose binding protein fusion tag. Nat Protoc. 2007;2:383–391. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2007.50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Branden C, Tooze J. Introduction to protein structure. 2nd ed. New York: Garland; 1999. pp. 356–357. [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kimple ME, Sondek J. Overview of affinity tags for protein purification. In: Coligan JE, Dunn BM, Speicher DW, Wingfield PT, Ploegh HL, editors. Current protocols in protein science. New York: Wiley; 2004. pp. 9.9.1–9.9.19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Russell BS, Zhong L, Bigotti MG, Cutruzzola F, Bren KL. Backbone dynamics and hydrogen exchange of Pseudomonas aeruginosa ferricytochrome c551. J Biol Inorg Chem. 2003;8:156–166. doi: 10.1007/s00775-002-0401-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kellogg JA, Bren KL. Characterization of recombinant horse cytochrome c synthesized with the assistance of Escherichia coli cytochrome c maturation factors. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2002;1601:215–221. doi: 10.1016/s1570-9639(02)00471-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fee JA, Chen Y, Todaro TR, Bren KL, Patel KM, Hill MG, Gomez-Moran E, Loehr TM, Ai JY, Thony-Meyer L, Williams PA, Stura E, Sridhar V, McRee DE. Integrity of Thermus thermophilus cytochrome c552 synthesized by Escherichia coli cells expressing the host-specific cytochrome c maturation genes, ccmABCDEFGH: biochemical, spectral, and structural characterization of the recombinant protein. Protein Sci. 2000;9:2074–2084. doi: 10.1110/ps.9.11.2074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Allen JWA, Barker PD, Ferguson SJ. A cytochrome b562 variant with a c-type cytochrome CXXCH heme-binding motif as a probe of the Escherichia coli cytochrome c maturation system. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:52075–52083. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M307196200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olson BJSC, Markwell J. Assays for determination of protein concentration. In: Coligan JE, Dunn BM, Speicher DW, Wingfield PT, Ploegh HL, editors. Current protocols in protein science. New York: Wiley; 2007. pp. 3.4.1–3.4.29. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stoscheck CM. Quantitation of proteins. Methods Enzymol. 1990;182:50–68. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(90)82008-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dunn B. Quantitative amino acid analysis. In: Coligan JE, Dunn BM, Speicher DW, Wingfield PT, Ploegh HL, editors. Current protocols in protein science. New York: Wiley; 2000. pp. 3.2.1–3.2.3. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Sinclair PR, Gorman N, Jacobs JM. Measurement of heme concentration. In: Maines M, Costa LG, Hodgson E, Lawrence DA, Reed DJ, Coruzzi G, Bus JS, Sipes IG, Sassa S, editors. Current protocols in toxicology. New York: Wiley; 1999. pp. 8.3.1–8.3.7. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vreman HJ, Cipkala DA, Stevenson DK. Characterization of porphyrin heme oxygenase inhibitors. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1996;74:278–285. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Appleton SD, Chretien ML, McLlaughlin BE, Vreman HJ, Stevenson DK, Brien JF, Nakatsu K, Maurice DH, Marks GS. Selective inhibition of heme oxygenase, without inhibition of nitric oxide synthase or soluble guanylyl cyclase, by metalloporphyrins at low concentrations. Drug Metab Dispos. 1999;27:1214–1219. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Riggs P. Expression and purification of maltose-binding protein fusions. In: Ausubel FM, Brent R, Kingston RE, Moore DD, Seidman JG, Smith JA, Struhl K, Albright LM, Borowsky ML, Coen DM, Shaw R, Smith CL, Varki A, Wildermuth MC, editors. Current protocols in molecular biology. New York: Wiley; 1994. pp. 16.16.11–16.16.14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]