Abstract

A microfluidic device was developed to produce temporal concentration gradients of multiple analytes. Four on-chip pumps delivered pulses of three analytes and buffer to a 14 cm channel where the pulses were mixed to homogeneity. The final concentration of each analyte was dependent on the temporal density of the pulses from each pump. The concentration of each analyte was varied by changing the number of pump cycles from each reservoir while maintaining the total number of pump cycles per unit time to ensure a constant total flow rate in the device. To gauge the independent nature of each pump, sinusoidal waves of fluorescein concentration were produced from each pump with independent frequencies and amplitudes. The resulting fluorescence intensity was compared to a theoretical summation of the waves and the experimental data matched the theoretical waves within 1%, indicating that the pumps were operating independently and outputting the correct frequency and amplitude. The device was used to demonstrate the role of ATP-sensitive K+ channels in glucose-stimulated increases in intracellular [Ca2+] in islets of Langerhans. Perfusion of single islets of Langerhans with combinations of glucose, diazoxide, and K+ resulted in intracellular Ca2+ patterns similar to what has been observed using conventional perfusion devices. The system will be useful in other studies with islets of Langerhans, as well as other assays that require the modulation of multiple analytes in time.

Keywords: microfluidic, gradient, pumping, perfusion, multi-analyte

1. Introduction

Microfluidic devices are popular for controlling and modulating concentration gradients due to the ease of automation and the variety of gradients that can be obtained [1–11]. In applications such as high-speed chromatography [12], sample preparation [13], or determining the frequency response of metabolic gene networks [1], temporal concentration gradients of analyte(s) are required. Regardless of the applications, generation of concentration waveforms in a rapid manner on a microfluidic device allows for increased automation, and decreased time, reagents, and cost spent during these analytical steps.

By far, the majority of microfluidic devices that have been described for production of temporal concentration gradients have generated gradients of a single analyte [1–3, 8–10]. Increased numbers of analytes could in principle be added, but at the cost of increasing device complexity. Since simple microfluidic devices lessen the burden of channel clogging and increase the probability of having non-specialists perform experiments with the system [14,15], a simple device is needed to produce simultaneous gradients of multiple analytes.

One example of a device that has been developed to produce both spatial and temporal gradients of multiple analytes was recently reported [16]. In this device, diffusion from each of the three inputs was used to generate a spatial and temporal gradient in a large static chamber. However, since the gradient was produced using diffusion, it took several minutes to reach its steady state and required care to maintain the gradient. And while diffusion can easily create overlapped concentration gradients at multiple locations, it is not a convenient method to control the concentration of each sample at a given point in the gradient chamber.

In another example of a system to produce multi-analyte gradients, 16 different inputs were connected to an output channel [17]. This device used a microfluidic multiplexer to choose up to 81 different combinations of the 16 inputs. Pulse code modulation (PCM) is another method to produce temporal concentration gradients [2,3]. In PCM, analyte and buffer are delivered as pulses to a microfluidic channel which acts as a low-pass filter where dispersion smoothes the pulses, producing a final concentration of analyte that is proportional to the temporal density of the analyte pulses. In all of the above examples, off-chip methods were used to drive solution flow through the devices. In two recent reports, a method has been described using on-chip pumps to deliver pulses of analyte and buffer to a mixing channel and simultaneously drive the solution flow though the system [18, 19]. This method was used to produce glucose concentration gradients to stimulate islets of Langerhans while intracellular [Ca2+] ([Ca2+]i) was monitored. However, as only concentration gradients of a single analyte, glucose, could be output, this limitation may render the method insufficient for other assays where multi-analyte concentration gradients are required.

In this report, multi-analyte concentration profiles were achieved via PCM by using on-chip pumps to deliver pulses from three analyte reservoirs and one buffer reservoir to a mixing channel. Similar to our previous report [18], the total number of pulses from these four reservoirs was kept constant at 100 pulses per minute. However, to ensure that each analyte could be pumped independently, the maximum number of pulses that could be delivered to the mixing channel from a single analyte pump (PS) was given by:

| (1) |

where Pt is the total number of pulses and N is the number of analyte pumps. As three analyte pumps were used (N = 3), a maximum of 33 pulses of analyte per minute could be delivered to the mixing channel from each analyte pump. This number of pulses resulted in a more limited concentration range of each analyte in this system as compared to our previous reports [18, 19], which used only a single analyte pump. Nevertheless, we have produced independent gradients of three analytes while maintaining a constant flow rate by adhering to the limits set forth by equation 1. To demonstrate the independent pumping of each analyte, a fluorescein concentration gradient was created by combining three sine waves produced from the analyte pumps. As an application of this device, the role of the ATP-sensitive K+ channel (K+ATP) in generating increases in [Ca2+]i was demonstrated by perfusing single islets of Langerhans with combinations of glucose, diazoxide, and K+. This microfluidic system described should be suitable for a large number of applications where temporal changes in multiple analytes are required.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1 Chemicals and Reagents

HNO3, CaCl2, NaOH, and NaCl were purchased from EMD Chemicals, Inc. (Gibbstown, NJ). MgCl2 and HF were from Fisher Scientific (Pittsburgh, PA). Diazoxide, KCl, fluorescein, dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO), collagenase, Pluronic F-127, and tricine were from Sigma (St. Louis, MO). Fluo-4 acetoxymethyl ester (AM), gentamicin, and antibiotic-antimycotic were from Invitrogen (Carlsbad, CA). RPMI 1640 cell culture media was from Mediatech Inc. (Manassas, VA). Fetal bovine serum was from HyClone (Franklin, MA).

All solutions used in the microfluidic device were made with a buffer composed of 2.4 mM CaCl2, 125 mM NaCl, 1.2 mM MgCl2, 5.9 mM KCl, 3mM glucose, 25 mM tricine and made to pH 7.4 with NaOH. All solutions were made with Milli-Q (Millipore, Bedford, MA) 18 MΩ·cm deionized water. For the mixing calibration experiments, three reservoirs contained 100 μM fluorescein and the fourth reservoir contained buffer. For the sinusoidal wave generation, three reservoirs contained 150 μM fluorescein and the fourth contained buffer. For the islet experiments, three reservoirs contained 60 mM glucose, 830 μM diazoxide and 85 mM KCl, and the fourth reservoir contained buffer.

2.2 Chip Design and Pumping Program

The device was fabricated in the same manner as in our previous work [18] with the following modifications. Three sets of pumps, each composed of three valves, were used to control the flow from four reservoirs. On the valve layer, the first two valve seats of each pump were 1.115 mm × 0.615 mm × 56 μm (length × width × depth) while the third, closest to the junction, was 1.035 mm × 0.535 mm × 17 μm (length × width × depth). On the fluid layer, the mixing channel was 140 mm × 256 μm × 112 μm (length × width × depth), which produced a mixing volume of 3.3 μL. All channel dimensions were measured with a profilometer (P-15, KLA-Tencor, Milpitas, CA).

Similar to the previous report [18], the first 4 steps of the valving sequence used for pumping took 120, 120, 150, and 210 ms, respectively. Since the sum of these four steps was 600 ms, 100 total pump cycles could be performed in one minute. The distributions of these 100 pump cycles to the four pumps dictated the final concentration of each analyte. To distribute the pump cycles, and therefore the output concentration, a 5th step in the valving sequence was added where all valves were closed. The timing of the 5th step was variable and is described more in Section 3.1. A program written in LabView (National Instruments, Austin, TX) was used to calculate the time of the 5th step and used to actuate computer-controlled solenoid valves (Model A00SC232P, Parker Hannifin Corp., Cleveland, OH) via a PCI-6220 data acquisition card (National Instruments) to perform the pumping.

2.3 Detection

In the chip characterization experiments, fluorescence was monitored from a 110 μm × 220 μm (length × width) section at the end of the mixing channel. For islet measurements, the islet was placed in a 200 nL chamber directly after the mixing channel. The mixing channel and the islet chamber were heated to 37°C before sample loading and maintained at this temperature throughout the experiments by a thermofoil and thermocouple (Omega Engineering, Inc., Stamford, CT). All measurements were made using a Nikon TS100F microscope. For both chip characterization and [Ca2+]i measurements, light from a Xenon arc lamp (Intracellular Imaging, Inc., Cincinnati, OH) was made incident on a dichroic cube (XF93, Omega Optical, Brattleboro, VT). The 488 nm excitation light was focused on the device through a 40X, 0.6 NA objective and the emitted fluorescence was collected by the same objective, passed through the dichroic cube, and focused through a spatial filter into a photometer (Photon Technology International, Inc., Birmingham, NJ) containing a photomultiplier tube (PMT). A bandpass filter (520DF40, Omega Optical) was used in front of the PMT.

2.4 Islet procurement

Male CD-1 mice were sacrificed by cervical dislocation followed by ductal injection of the pancreas with 0.6mg/mL collagenase. The pancreas was dissected and incubated in 5 mL of collagenase at 37 °C for 7 min. Islets were picked under a stereomicroscope into RPMI 1640 cell culture media supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum, 1% antibiotic-antimycotic, 0.1% gentamicin, and incubated at 37 °C, 5% CO2. Islets were used within 72 hours following isolation.

For [Ca2+]i monitoring, 1.5 μL of 4.56 mM fluo-4 AM in DMSO and 1.5 μL Pluronic F-127 in DMSO were combined and transferred into 2 mL RPMI to produce a final fluo-4 AM concentration of 3.4 μM. An islet was placed in this solution and allowed to incubate at 37 °C, 5% CO2 for 30 min. After incubation, the islet was washed in buffer and transferred to the cell chamber under a stereomicroscope.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

As mentioned earlier, the ability to control the temporal concentration of multiple analytes would be useful in many types of assays. As the use of on-chip pumps greatly simplifies the microfluidic setup, we built upon our previous work [18, 19] that utilized diaphragm pumps [20] to drive the solution through the device and produce on-line dilutions using PCM. In this report, we demonstrate how the system could be applied to generate gradients of multiple analytes independently while maintaining a relatively simple device.

3.1 Principle of operation

The chip design for the quantitative control of multiple analytes is shown in Fig. 1a where pumps 1–3 were used to control flow from 3 analyte reservoirs and pump 4 was used to control the flow from a buffer reservoir. During a pump cycle, the pumps delivered a pulse of each of these analytes to the mixing channel where dispersion mixed the pulses producing the final concentration. Fig. 1b shows a zoomed in view of the junction of the channels from the four reservoirs.

Fig. 1. Microfluidic system for multi-analyte gradient generation.

a. The microfluidic device used to produce multi-analyte gradients is shown. The valves that compose the pumps are too small to be seen at this scale, but are represented as the open circles. The device was composed of pumps 1–4, which delivered three analytes and a buffer to the mixing channel. The area enclosed by the red circle is shown in detail in Fig. 1b. b. A photograph of the junction of the four pumping channels after pumping red, blue, green and orange color dyes from each reservoir. c. The spikes in these traces represent the times at which each pump delivered a pulse of its reagent to the mixing channel. The blue, green, red, and black traces correspond to pumps 1, 2, 3, and 4, respectively. The dilution percentages of each analyte are shown above the traces. At 30 s, shown by the black vertical line, the dilution percentages for each analyte were changed.

To produce the desired output concentration of each analyte independently while maintaining a constant total flow rate in the mixing channel, the sum of the number of pump cycles was held constant at 100 pump cycles min−1. To vary the number of pump cycles delivered from each pump, and therefore the concentration of each analyte, all valves in the pumps were closed and left idle at the end of each pump cycle for an amount of time that was inversely proportional to the final concentration desired. For example, if a high concentration of analyte 1 was required, the number of pump cycles from this pump was high; consequently, the pump was turned off for a short amount of time between cycles. If a low concentration was required, then a relatively few number of pump cycles were needed, and the pump was turned off for a long period of time at the end of each pump cycle. Therefore, controlling the time that the pump was off allowed control over the concentration output. The time (in seconds) of the 5th step of each pump was found from the following equation:

| (2) |

where Xi was the dilution percentage of each analyte. However, as described in Section 1 and given by equation 1, to run the device with three analytes simultaneously, X1–3 could only be varied between 0 and 0.33. This initial condition put a limit on the range of output concentrations that could be produced for each analyte, but was necessary to ensure that each pump could act independently and to ensure the flow rate remained constant. Using equation 3, the percentage of buffer, X4, was calculated by the pumping program by summing the pump cycles from pumps 1–3 and ensuring the total dilution of the device was equal to 1.00:

| (3) |

X1, X2 and X3 were set by the user in a LabView program to control the output concentration.

As an example of the timing, Fig. 1c shows a series of spikes that represent the times pumps 1–4 delivered a pulse to the mixing channel. In the first 30 s, X1 = X2 = X3 = 0.30, and X4 = 0.10. As expected at this ratio, 3 pulses of each analyte were delivered to the mixing channel for every pulse of buffer. In the next 30 s, the concentration of each analyte was changed to X1 = 0.10, X2 = 0.20, X3 = 0.30, and X4 = 0.40 which can be seen as a change in the pulse density of each analyte.

3.2 Multi-analyte gradient generation

Production of the correct online dilutions depended on complete mixing of the reagents in the mixing channel. Mixing was tested as described before [18] by comparing the standard deviation of the PMT signal from online (0.07 V) and offline-prepared solutions (0.07 V). As the standard deviations were similar, the mixing of the analyte and buffer pulses was deemed complete. If mixing was incomplete, the standard deviation of online-mixed solutions would be higher than offline-prepared solutions because the unmixed pulses of fluorescein and buffer would produce a time-varying signal from the PMT.

To test the ability to produce accurate concentrations by the device, PMT values from offline-made fluorescein solutions were compared to a series of fluorescein dilutions produced online. Fluorescein solutions at 0, 30, 60, and 90 μM were prepared offline and pumped through the device from all four pumps. The average PMT readings are shown as the black, dashed horizontal lines in Fig. 2a. Calibration of online mixing was tested by placing 100 μM fluorescein in reservoirs 1–3 and buffer in reservoir 4 and producing a series of online dilutions (Fig. 2a). Pumping was started using pump 4 which resulted in a low PMT signal. After a short period of time, pump 1 began pumping at X1 = 0.30, followed by pump 2 at X2 = 0.30, and finally pump 3 at X3 = 0.30. As can be seen, the fluorescence intensity increased when each pump commenced pumping. Due to dilution, the resulting concentrations of fluorescein should have been 30, 60, and 90 μM at the detection point when pumps 1, 2, and 3 began pumping, respectively. As summarized in Fig. 2b (the average signal at 0 μM fluorescein was subtracted from all data points), these online solutions had statistically similar intensity values and standard deviations compared to the offline-mixed solutions based on a two-sample t-test. Linear regression through the data from the online solutions gave a fit of y = 0.049x + 0.491 with an r2 = 0.999.

Fig. 2. Calibration of the multi-analyte mixing system.

a. Average intensities from fluorescein solutions prepared offline were plotted as the dashed horizontal lines. Online dilutions were produced by delivering fluorescein from reservoirs 1, 2, and 3 while pump 4 delivered buffer as described in the text. Online dilutions were repeated three times and shown as the blue, red and green traces. b. Average PMT readings at each concentration of fluorescein of the three experiments shown in Fig. 2a were plotted (red points) with the PMT readings from offline-prepared solutions (black points). The average signal at 0 μM fluorescein was subtracted from all data points to remove the background signal. Error bars represent + 1 standard deviation.

From these calibrations, lag and response times were calculated. Lag times were defined as the time that was required to deliver a new solution from the pumps to the detection point. These times were found by measuring the difference in time from when the concentration was changed in the program to the point at which the fluorescence intensity increased by 10% above the previous signal. The average lag time over all concentrations tested was 165.0 + 15.0 s. The average volumetric flow rate was calculated using the average lag time and the channel volume. The average flow rate in the mixing channel was 1.2 + 0.1 μL/min. Response times were defined as the time needed to change the signal from 10% to 90% of the final signal. The average response time over all concentrations tested was 15.0 + 1.2 s.

In this system and others [18, 19], a finite amount of time is required to fully mix the pulses from the pumps, but the mixing time needs to be minimized to reduce the response time. We have recently described a method to reduce the amount of lag time and subsequent dispersion of a single analyte system to produce rapid changes in concentration [19]. Briefly, the mixing channel length can be decreased, or the flow rate increased to reduce either the lag or response time, but these reductions may occur at the expense of reduced mixing of the pulses from the pumps. It may be possible to use either an active or passive mixer in the mixing channel to decrease mixing time. As will be shown in Sections 3.3 and 3.4, the lag and response times produced in this report did not hinder the experiments we performed in this report.

3.3 Multi-analyte waveforms

After demonstrating the production of accurate online dilutions, the ability to pump independently from each reservoir was tested by outputting waveforms of fluorescein concentration from each pump. Similar to our previous report [18], waveforms were produced by changing the concentration of analyte through a certain range at a given frequency. In this experiment, 150 μM fluorescein was used in reservoirs 1, 2, and 3 and sine waves with a median value of 22.5 μM were produced.

Since fluorescein was being output from pumps 1–3, the PMT reading measured at the end of the mixing channel was due to the average of the intensities from the three fluorescein waves generated. An attempt was made to take advantage of the “interference” pattern that would be produced if all three pumps were working independently and producing the waveforms at the proper amplitude and frequency. The resultant wave was synthesized by outputting three sine waves at frequencies of 0.0015, 0.0045, and 0.0075 Hz using amplitudes of 22.5, 7.5, and 4.5 μM for pumps 1, 2, and 3, respectively. As can be seen in Fig. 3, the fluorescence intensity detected by the PMT (red line) matched a theoretical summation of three sine waves at these frequencies (black line). This test was a good demonstration of the independent nature of the operation of multiple pumps. According to simulations (data not shown), if the pumps were producing frequencies and/or amplitudes that had 1% deviations from the intended frequencies and/or amplitudes, the pattern produced would result in an obvious shift of the shape of the final wave. Since the experimental matched the theoretical wave, we were confident that each pump was outputting the correct waves in an independent fashion.

Fig. 3. Multi-analyte waveform generation.

Three sine waves with different amplitudes and frequencies as described in the text were generated by pump 1, 2 and 3 simultaneously. The resultant PMT reading was plotted as the red line and the theoretical summation of these three waves was plotted as the black line. Due to the high correlation between the experimental and theoretical curves, the gradients produced by the four pumps were believed to be correct.

3.4 Demonstration of the K+ATP-dependent pathway in islets of Langerhans

After determining that the device produced accurate online dilutions and each pump could be controlled independently, the device was used to stimulate a signal transduction pathway in islets of Langerhans. Islets of Langerhans are the endocrine portion of the pancreas that secretes the hormones responsible for blood glucose homeostasis. Defects in the regulation of glucose levels results in metabolic disorders, such as type II diabetes. The conventional hypothesis of insulin secretion is that within the β-cells of the islets of Langerhans (the majority of the cells in an islet), glucose metabolism increases the ratio of adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to adenosine diphosphate (ADP). This increase in ATP:ADP ratio results in closure of the K+ATP channels in the plasma membrane, depolarizing the cell membrane, and opening voltage-gated Ca2+ channels. The influx of extracellular Ca2+ then leads to release of insulin. As the K+ATP channels link the metabolic and ionic effects within the β-cells, the role of these channels in this pathway is essential [21].

The importance of these channels can be demonstrated through the use of pharmacological agents. Application of stimulatory concentrations of glucose to islets will increase the [Ca2+]i via the pathway described above. Addition of diazoxide to the perfusion media will clamp the K+ATP channels open, which inhibits closure of the K+ATP channels, resulting in a diminished [Ca2+]i. However, application of a high [K+] restores membrane depolarization, opening the voltage-gated Ca2+ channels, and increasing [Ca2+]i. While this is a well-known signal transduction mechanism, it provides a good example of a system that can be investigated with a multi-analyte perfusion system.

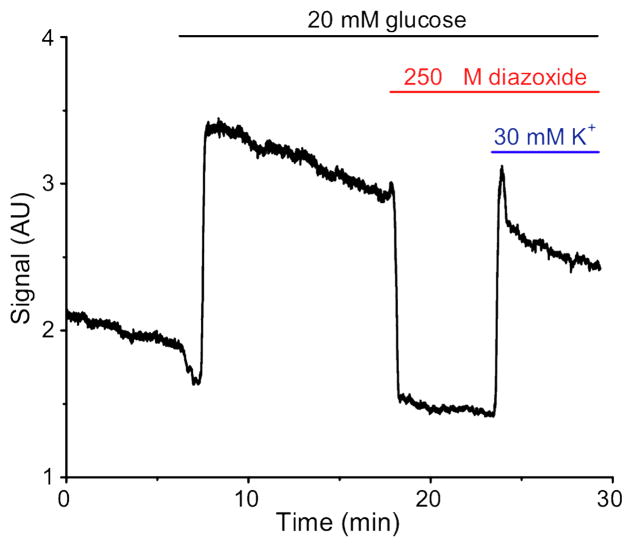

A single islet was loaded with the Ca2+-sensitive fluorophore, fluo-4, and placed at the end of the mixing channel in a 200 nL chamber. Buffer containing 3 mM glucose was perfused over the islet. After obtaining a basal [Ca2+]i reading, the glucose concentration was increased to a constant 20 mM by pumping from reservoir 1. This increase in extracellular glucose concentration induced an increase in [Ca2+]i as expected. 250 μM diazoxide was then introduced to the islet by pumping from reservoir 2 while maintaining perfusion with 20 mM glucose. As seen in Fig. 4, application of diazoxide quickly resulted in a decrease in fluo-4 fluorescence indicating that [Ca2+]i returned to basal levels since the K+ATP channels were opened and the voltage dependent Ca2+ channels closed. Finally, [Ca2+]i was increased by pumping from reservoir 4 which increased the [K+] concentration from 6 mM to 30 mM. This experiment was repeated with 3 islets and all responded in a similar manner. The fluo-4 response observed using the microfluidic perfusion system was similar to those obtained with a conventional perfusion system [22], indicating that the system developed will be suitable for future studies on islets of Langerhans or other cell types.

Fig. 4. Glucose stimulation with multiple reagents.

Fluo-4 fluorescence from a single islet was measured as a function of time in response to changes in glucose, diazoxide and potassium, respectively. The black, red and blue bars above the figure indicate when 20 mM glucose, 250 μM diazoxide, and 30 mM K+, respectively, reached the cell culture chamber.

4. CONCLUSION

Building on our previous microfluidic perfusion system, a new design was used to achieve multi-analyte concentration gradients. The mechanism for producing these multiple gradients is relatively simple by substituting buffer pulses with analyte pulses. In the future, additional reservoirs could be added to increase the number of analytes that can be used, although with increasing numbers of reagents, the concentration range that can be produced becomes more limited. As an application of the device, the role of the K+ATP channels in glucose-stimulated [Ca2+]i increases in islets of Langerhans was demonstrated. The results indicated that the system could be used for other biochemical assays with other cell types.

Future improvements may be aimed at increasing the total number of pump cycles to allow a larger range of concentrations to be delivered from each pump. Also, if the number of solenoid valves and air connections becomes too cumbersome, other methods using large-scale integration [17] would be a better method to introduce more analytes.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded in part from grants by the National Institutes of Health (R01 DK080714) and the American Heart Association Greater Southeast affiliate.

References

- 1.Bennett MR, Pang WL, Ostroff NA, Baumgartner BL, Nayak S, Tsimring LS, Hasty J. Nature. 2008;454:1119–1122. doi: 10.1038/nature07211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Azizi F, Mastrangelo CH. Lab Chip. 2008;8:907–912. doi: 10.1039/b716634f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ainla A, Gozen I, Orwar O, Jesorka A. Anal Chem. 2009;81:5549–5556. doi: 10.1021/ac9010028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kang T, Han J, Lee KS. Lab Chip. 2008;8:1220–1222. doi: 10.1039/b800859k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Coleman JT, McKechnie J, Sinton D. Lab Chip. 2006;6:1033–1039. doi: 10.1039/b602085b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Irimia D, Geba DA, Toner M. Anal Chem. 2006;78:3472–3477. doi: 10.1021/ac0518710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dertinger SK, Chiu DT, Jeon NL, Whitesides GM. Anal Chem. 2001;73:1240–1246. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Olofsson J, Pihl J, Sinclair J, Sahlin E, Karlsson M, Orwar O. Anal Chem. 2004;76:4968–4976. doi: 10.1021/ac035527j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sinclair J, Pihl J, Olofsson J, Karlsson M, Jardemark K, Chiu DT, Orwar O. Anal Chem. 2002;74:6133–6138. doi: 10.1021/ac026133f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Olofsson J, Bridle H, Sinclair J, Granfeldt D, Sahlin E, Orwar O. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2005;102:8097–8102. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0500230102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee PJ, Gaige TA, Hung PJ. Lab Chip. 2009;9:164–166. doi: 10.1039/b807682k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stoll DR, Carr PW. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:5034–5035. doi: 10.1021/ja050145b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Legendre LA, Bienvenue JM, Roper MG, Ferrance JP, Landers JP. Anal Chem. 2006;78:1444–1451. doi: 10.1021/ac0516988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martinez AW, Phillips ST, Carrilho E, Thomas SW, III, Sindi H, Whitesides GM. Anal Chem. 2008;80:3699–3707. doi: 10.1021/ac800112r. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mabey D, Peeling RW, Ustianowski A, Perkins MD. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2004;2:231–240. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Atencia J, Morrow J, Locascio LE. Lab Chip. 2009;9:2707–2714. doi: 10.1039/b902113b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cooksey GA, Sip CG, Folch A. Lab Chip. 2009;9:417–426. doi: 10.1039/b806803h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zhang XY, Roper MG. Anal Chem. 2009;81:1162–1168. doi: 10.1021/ac802579z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Zhang XY, Grimley A, Bertram R, Roper MG. Anal Chem. 2010;82:6704–6711. doi: 10.1021/ac101461x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grover WH, Skelley AM, Liu CN, Lagally ET, Mathies RA. Sens Actuators B. 2003;89:315–323. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Henquin J. Diabetes. 2000;49:1751–1760. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.49.11.1751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Westerlund J, Ortsater H, Palm F, Sundsten T, Bergsten P. Eur J Endocrinol. 2001;144:667–675. doi: 10.1530/eje.0.1440667. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]