Abstract

To identify potential mechanisms underlying prostate cancer chemotherapy response and resistance, we compared the gene expression profiles in high-risk human prostate cancer specimens before and after neoadjuvant chemotherapy & radical prostatectomy. Among the molecular signatures associated with the chemotherapy, transcripts encoding Inhibitor of DNA Binding 1 (ID1) were significantly upregulated. The patient biochemical relapse status was monitored in a long-term followup. Patients with the ID1 upregulation were found to be associated with longer relapse-free survival than patients without the ID1 increase. This in vivo clinical association was mechanistically investigated. The chemotherapy-induced ID1 upregulation was recapitulated in the prostate cancer cell line LNCaP. Docetaxel dose-dependently induced ID1 transcription, which was mediated by ID1 promoter E-box chromatin modification and c-Myc binding. Stable ID1 overexpression in LNCaP increased cell proliferation, promoted G1 cell cycle progression, and enhanced docetaxel-induced cytotoxicity. These changes were accompanied by a decrease in cellular mitochondria content, an increase in BCL2 phosphorylation at serine 70, caspase-3 activation and PARP cleavage. In contrast, ID1 siRNA in the LNCaP and C42B cell line reduced cell proliferation, and decreased docetaxel-induced cytotoxicity by inhibiting cell death. The ID1-mediated chemosensitivity enhancement was in part due to the ID1-suppression of p21. Overexpression of p21 in LNCaP-ID1 overexpressing cells restored the p21 level and reversed ID1-enhanced chemosensitivity. These molecular data provide a mechanistic rationale for the observed in vivo clinical association between ID1 upregulation and relapse-free survival. Taken together, it demonstrates that ID1 expression has a novel therapeutic role in prostate cancer chemotherapy and prognosis.

Keywords: prostate cancer, chemotherapy sensitivity, ID1, p21

INTRODUCTION

In the treatment of advanced, castration resistant prostate cancer (CRPC), docetaxel-based chemotherapy is empirically deployed as no markers are available to select patients who do and do not benefit from treatment 1-3. When used preoperatively in the treatment of high-risk and localized disease, docetaxel-based chemotherapy can reduce serum PSA, but has not resulted in complete pathological responses, and the long-term benefit is a subject of ongoing randomized clinical trials 4-6. These results emphasize the importance of understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying the prostate cancer chemotherapy response and resistance.

ID1 is a negative regulator of basic helix-loop-helix (bHLH) transcription factors 7. It has been implicated in regulating a variety of cellular processes including growth, senescence, differentiation, apoptosis, angiogenesis and neoplastic transformation 8. In various mammalian cell culture models, cellular differentiation is associated with the down-regulation of ID1, while ID1 overexpression inhibits the ability to differentiate 9. The inhibition of differentiation can also be accompanied by cell proliferation 10. Several lines of evidence have suggested that the ID1 transcriptionally inhibits the expression of cyclin dependent kinase inhibitors p16, p21, and p27 11-13. Cells that overexpress ID1 progress through the G1-S cell cycle transition much faster than those without 7, 14. ID1 has been shown to promote apoptosis in a variety of settings 7. Transgenic mice engineered to overexpress ID1 in T cells show massive apoptosis in thymocytes 15. ID1 overexpression has also been reported to induce apoptosis in dense mammary epithelial cells, and cardiac myocytes via a redox mechanism 16, 17.

The role of ID1 in cancer development has also been intensely investigated. ID1 knockout mice exhibit an impaired angiogenic response to tumor xenografts due to the reduced endothelial cell differentiation, mobilization and recruitment 18, but are also more susceptible to tumor formation in a chemical-induced skin carcinogenesis model 19. In human breast cancer, overexpression of ID1 is associated with lung metastasis 20, 21. In prostate cancer cell lines, ID1 is linked with increased androgen independence 22, oncogenic signaling 23, 24, and resistance to cytotoxic therapy 25-28. While ID1 protein overexpression was initially reported in many tumor types, more recent recognition of the nonspecific nature of the antibodies used, have brought into question the validity of these observations including those made in clinical samples of prostate cancer 29. Recently, we observed that ID1 mRNA transcripts were significantly down-regulated in patient-matched human prostate cancer epithelium compared to its adjacent benign epithelium derived from laser-capture microdissection (LCM) of frozen needle biopsy samples 30. Overall, the role of ID1 has been well defined in the endothelial compartment and tumor angiogenesis, but not in epithelial cancer cells. The impact of cancer therapies on ID1 expression is not well understood.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines

The human prostate cell line LNCaP and human embryonic kidney cell line 293T/17 (HEK293T/17) were purchased from the American Type Culture Collection, Manassas, VA. Prostate cancer C42B cell line was a gift from Dr. John Isaacs at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine. Cells were cultured as previously described 31.

Plasmid construction and transfection

Lentiviral - ID1 expressing plasmid was kindly provided by Dr. Rhoda Alani (Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine). Lenti virus vector iDuet 101 and packing plasmids pCMVΔ8.92 and pMD.G were kind gifts of Dr. Linzhao Cheng, (Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine). Full-length p21 was amplified by PCR from cDNA of LNCaP cell line and inserted to a lentiviral vector iDuet 101.

ID1 siRNA

An oligo-based ID1 siRNA cocktail (SMARTpoll siRNA) and transfection reagent Dharmafect 3 were purchased from Thermo Scientific Dharmacon (Lafayette, CO). The transfection was based on the manufacture's protocol as previously described 32.

CHIP

LNCaP cells were treated with either solvent or 10 nM DTX for 24 hours. The chromatin immunoprecipitation (CHIP) assay was performed as previously described 33 using antibodies specific for c-Myc (Santa Cruz Biotechnology), acetyl-histone 3 lysine 9 (Ace-H3K9) (Millipore Inc), or isotype rabbit IgG control. DNA recovered from CHIP or input controls were subject to real-time quantitative PCR using primers flanking the E-box in ID1 promoter region (forward: 5’-TGGAAGATTGC ACTGTGGGCA-3’, and reverse: 5’- CACTGTTCTCGTCCAGAGTGTTCT - 3’). The promoter occupancy was calculated based on the ratio of CHIP / input control.

Cell Proliferation and Viability

As previously described 34, cancer cells were seeded at a density of 5 × 104 cells per well in 24-well or 12-well culture plates. 24 hours after seeding, the attached cells were treated. Viable cells at specific time points were counted by a hemocytometer based on the trypan blue exclusion principal.

Florescence Assisted Cell Sorting (FACS) Cell Cycle Analysis

Flow cytometry analysis was carried out in BD FACS Calibur® analyzer as previously described 31. Results were analyzed by software for cells at sub-G1 (dead cells), G1, S and G2 phases.

Real-Time PCR

Real-time PCR was performed on ABI PRISM 7500 Fast instrument using the SYBR Green PCR Universal Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). B-actin was used as an internal control. Primer sequences are available on request. Delta-Delta Ct method was employed to represent mRNA fold change.

Statistical Analysis

Differences between the means of unpaired samples were evaluated by the Student's t test and ANOVA using the SigmaPlot and SigmaStats program. P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All statistical tests were two sided. Progression-free survival was calculated using the Kaplan-Meier method and Chi-Square test.

RESULTS

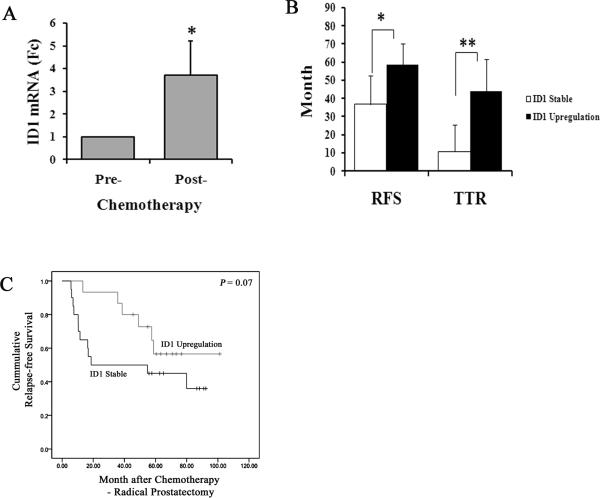

In prostate cancer cells microdissected from patients, ID1 mRNA was upregulated by chemotherapy and associated with longer relapse-free survival

To identify the molecular signatures associated with chemotherapy, we compared the gene expression patterns of patients with high-risk localized prostate cancer before and after chemotherapy with docetaxel and mitoxantrone 35. To avoid possible bias due to different stages of cellular differentiation, we used laser capture microdissection (LCM) to specifically isolate tumor epithelium with the same Gleason grade from both pre- and post- treatment tissues 35. We performed cDNA microarray analyses using a head-to-head comparison of specimens from the same patients before and after treatment. We then subtracted gene expression alterations that could be attributed to surgical procedures and different methods of tissue acquisition 30, 35, 36. We found that the gene encoding Inhibitor of DNA Binding 1 (ID1) was significantly upregulated in the post-chemotherapy specimens (S1). Subsequently, we confirmed the upregulation using qRT-PCR in 35 patient samples (Figure 1A). In pre- and post- treatment matched LCM-cancer cells with the same Gleason score, we found ID1 was significantly upregulated by at least 1 fold in 15 out of 35 patients (S2). After chemotherapy and radical prostatectomy surgery, all patients were followed by quarterly blood prostate specific antigen (PSA) test. Patients with confirmed PSA values higher than 0.4 were considered to have a PSA biochemical relapse (BCR). After a median of 56 months of post chemotherapy - radical prostatectomy followup, we found that 60% (12/20) of ID1 stable and 40% (6/15) of ID1 upregulation patients developed BCR. The median relapse-free survival (RFS) was 36.7 months for ID1 stable group and 58.7 months for ID1 upregulation (Figure 1B). The median time to develop BCR (TTR) was 10.9 months for the ID1 stable group, but 43.8 months for ID1 upregulation group, which were significantly different (Figure 1B). The relapse-free survival analysis stratified by the change of ID1 suggested that the chemotherapy-induced ID1 upregulation was associated with the delay of BCR (Figure 1C). Importantly, Fisher's exact test analysis demonstrated that the frequencies of relapse were significantly lower in the ID1 upregulation group compared to the ID1 stable group 3 years after the chemotherapy - radical prostatectomy treatment. Specifically, the relapse frequencies for ID1 upregulation vs. stable groups were 0% vs. 35% after 12 months (P = 0.012), 6.7% vs. 50% after 24 months (P = 0.009), and 13.7% vs. 50% after 36 months (P = 0.034). These data suggested to us that ID1 upregulation possibly plays a role in mediating the chemotherapy efficacy or disease behavior and delaying the onset of biochemical relapse.

1.

Chemotherapy-induced ID1 upregulation is associated with a significant delay in developing biochemical relapse. (A) ID1 upregulation in post-treatment cancer epithelium was confirmed by qRT-PCR. The cDNA of 35 patients from post-treatment radical prostatectomy samples and pre-treatment needle biopsy samples were used. For each patient, ID1 transcript level was measured by qRT-PCR and quantified using the comparative delta-delta Ct method (post – pre) with actin as an internal control. Mean and standard deviation (SD), * P < 0.01, paired t-test. (B) The time of relapse-free survival (RSF) and the time to relapse (TTR) according to the post chemotherapy change in ID1 mRNA level (upregulation vs. stable) in patients. Median with 95% confidence interval. * P = 0.05, ** P = 0.02, t-test. (C) The Kaplan-Meier analysis stratified by the change of ID1 status.

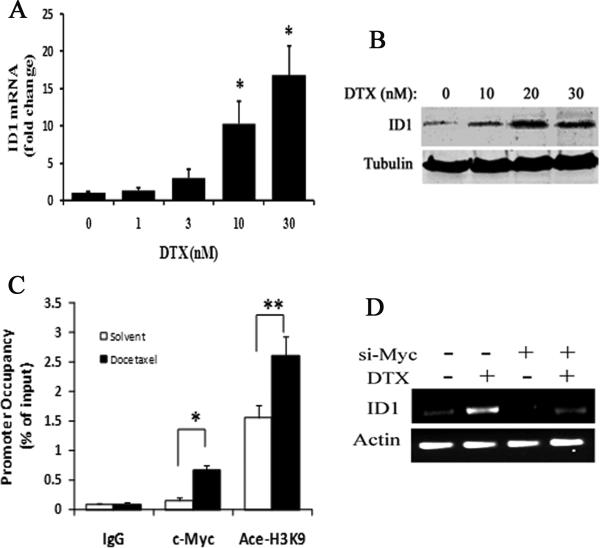

Docetaxel upregulates ID1 expression via c-Myc in prostate cancer cells

We confirmed that ID1 can be upregulated by chemotherapy. We treated the LNCaP prostate cancer cell line with increasing doses of either docetaxel or mitoxantrone, and measured the mRNA and protein levels by qRT-PCR and Western blots, respectively. Docetaxel, but not mitoxantrone (data not shown), was able to induce ID1 mRNA and protein expression at concentrations of 10 nM and higher (Figure 2A & 2B). In breast cancer cells, ID1 expression has been associated with c-Myc regulation 37. In B-cell lymphoma, global chromatin immunoprecipitation (CHIP) analysis revealed an E-box c-Myc binding site in the ID1 promoter 38. To investigate the molecular pathways involved in docetaxel-induced ID1 expression, we measured both c-Myc occupancy and local chromatin structure modifications surrounding the ID1 promoter E-box by quantitative CHIP (qCHIP) in LNCaP cells. We found that c-Myc protein levels were not significantly altered following docetaxel (10 nM) treatment (S3) and ID1 overexpression (S4). However, c-Myc occupancy in the ID1 promoter E-box was significantly higher in docetaxel-treated cells than solvent controls (Figure 2C). This increase was accompanied by the increase of histone acetylation that is commonly associated with transcriptionally active chromatin (Figure 2C). Further, transient siRNA inhibiting c-Myc reduced both the basal and docetaxel-induced ID1 mRNA levels in LNCaP (Figure 2D).

2.

Docetaxel induced ID1 expression via c-Myc in LNCaP cells. (A) LNCaP cells were exposed to the indicated dose docetaxel (DTX) for 24 hours. RNA was isolated, the ID1 transcript levels were measured by qRT-PCR, and the fold change was calculated by delta-delta Ct method relative to samples of 0 nM DTX. * P < 0.01 vs. 0, 1, 3 nM DTX samples, ANOVA. (B) Representative western blot result. LNCaP cells were treated with the indicated doses of DTX for 24 hours. Whole cell lysates were used for ID1 and tubulin protein measurements. (C) LNCaP cells were treated with either solvent or 10 nM DTX for 24 hours. CHIP assay was done using antibodies specific for c-Myc, acetyl-histone 3 lysine 9 (Ace-H3K9), or isotype rabbit IgG control. DNA recovered from CHIP or input controls were subject to real-time quantitative PCR using primers flanking the E-box in ID1 promoter region. The promoter occupancy was calculated based on the ratio of CHIP / input control. * P < 0.001, ** P < 0.01, t-test. (D) A representative RT-PCR result. LNCaP cells were treated with siRNA oligo against c-Myc or none-targeting control for 48 hours. Then cells were treated with 10 nM DTX or solvent control for another 24 hours. ID1 and actin mRNA transcript levels were measured by RT-PCR, and PCR products were resolved on agarose gels. All results are mean and SD of 3 independent experiments.

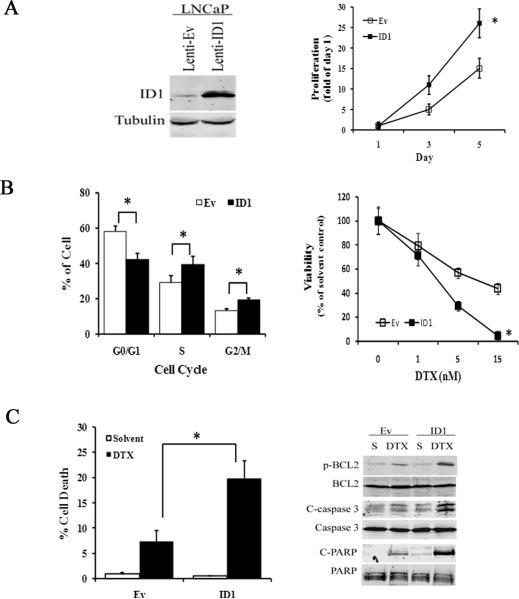

Stable ID1 expression enhances docetaxel cytotoxicity in LNCaP cells

We employed the LNCaP cell line with low basal ID1 levels to investigate whether ID1 overexpression mediates prostate cancer cell response to docetaxel chemotherapy. We transduced LNCaP cells with pseudo-lentivirus carrying an ID1 expression cassette. The transduced cell line (LNCaP-ID1) had stable and robust ID1 expression compared to the empty-vector control cell line (LNCaP-Ev) (Figure 3A, left). Using the cell proliferation assay, we observed that LNCaP-ID1 cells grew much faster than the -Ev controls (Figure 3A, right). This increase in proliferation was accompanied by a decrease in G1 phase, and an increase in S and G2/M phase cell populations measured by flow cytometry (FACS) (Figure 3B, left), while no significant change in viability or cell death was observed (data not shown).

3.

ID1 overexpression induces proliferation and enhances chemosensitivity. (A) Left: A representative western blot of LNCaP cells transduced by pseudo-lentivirus containing empty vector (Lenti-Ev) or ID1 overexpressing vector (Lenti-ID1). Right: Equal numbers of lenti-Ev and lenti-ID1 cells were seeded in 12 well plates for 24 hours. Viable cells were counted by a hemocytometer based on trypan blue exclusion at day 1, 3, and 5 after seeding. The proliferation was calculated by dividing the number of viable cells at day 1, 3 and 5 by those of at day 1. * P < 0.01, ANOVA. (B) Left: Cell cycle distribution of lenti-Ev and lenti-ID1 cells at day 3 of the culture via flow cytometry analysis. * P < 0.05, t-test. Right: Equal numbers of lenti-Ev and lenti-ID1 cells were treated with docetaxel (DTX) at the indicated doses for 48 hours. Viable cells were counted and adjusted to those of 0 nM solvent control. * P < 0.01. (C) Left: Cells were treated with solvent or 10 nM docetaxel (DTX) for 48 hours. Flow cytometry was performed. The % of sub-G1 cells in each cell line was plotted as cell death. * P < 0.01, t-test. Right: Representative western blots of cells treated by solvent or 10 nM docetaxel for 48 hours. All results are mean and SD of 4 independent experiments.

Next, we tested the sensitivity of LNCaP-Ev and -ID1 cell lines to chemotherapy. We treated cells with 0, 1, 5 and 15 nM of docetaxel for 48 hours. By counting viable cells based on trypan blue exclusion, we observed that LNCaP-ID1 cells were significantly less viable than empty-vector cells at both 5 and 15 nM compared to their respective solvent-treated controls (Figure 3B, right). FACS analysis confirmed the enhanced sensitivity. Docetaxel decreased cell cycle progression and increased cell death in both cell lines. Compared to LNCaP-Ev cells, ID1 expressing cells had a significantly larger decrease in the G1 phase (S5) and a larger increase in sub-G1 (dead cell) population after docetaxel treatment (Figure 3C, left). The increased cytotoxic effect was also observed using Western blot analysis of proteins involved in the apoptotic pathway associated with docetaxel. BCL2 phosphorylation at serine 70, which inactivates BCL2 and mediates taxane-based apoptosis 39, was more robust in ID1 expressing cells than in -Ev controls after docetaxel treatment. The activation (cleavage) of caspase-3 and PARP, processes associated with apoptosis, were more active in docetaxel-treated LNCaP-ID1 than LNCaP-Ev (Figure 3C, right). In addition, ID1 overexpression in LNCaP-ID1 cell line caused reductions in mitochondrial DNA and mitochondrial mass (S6). Therefore, we speculate that ID1 overexpression can cause the mitochondrial damage which in turn sensitizes cells to docetaxel-induced cytotoxicity.

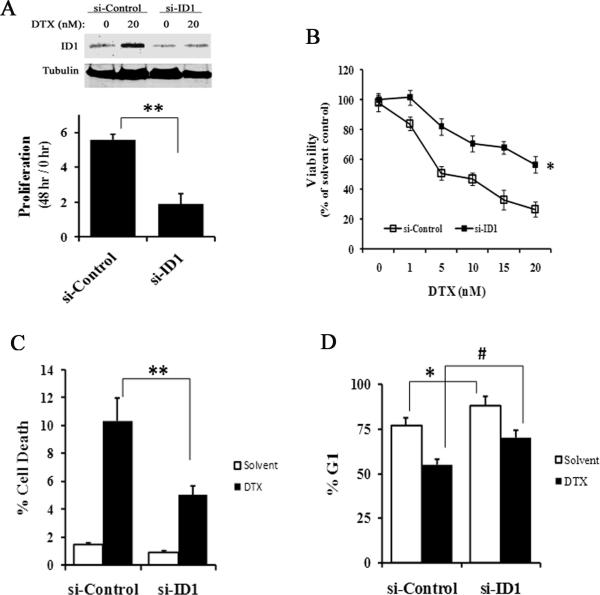

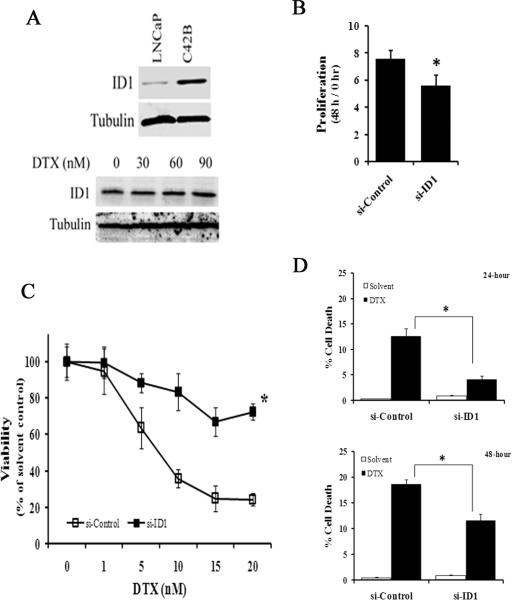

ID1 siRNA reduces docetaxel cytotoxicity in prostate cancer cells

We next evaluated ID1 loss-of-function to further elucidate the role of ID1 in mediating chemotherapy. In the LNCaP cell line, siRNA against ID1 (si-ID1) reduced docetaxel-induced ID1 expression (Figure 4A, top). Cells treated with ID1 siRNA grew significantly slower than the non-targeting siRNA controls (si-Control) (Figure 4A, bottom). 48 hours after transfection of the siRNA oligos, cells were treated with increasing concentrations of docetaxel for 2 days. The cells transfected with si-ID1 were less sensitive to docetaxel than cells transfected with si-Control (Figure 4B), which was associated with reduced cell death (Figure 4C) and increased numbers of cell arrested in G1 (the # of Figure 4D). We also tested the effect of ID1 siRNA in the C42B prostate cancer cell line that expresses a robust amount of endogenous ID1 protein (Figure 5A, top). Unlike in LNCaP, docetaxel did not further induce ID1 expression in C42B (Figure 5A, bottom). Transient siRNA consistently reduced ID1 protein levels in C42B cells over a period of 2 to 5 days (S7). Consistent with the proliferative effect of ID1 seen in LNCaP, ID1 siRNA slightly but significantly reduced the proliferation of C42B cells (Figure 5B), while the cell death remained trivial (data not shown). ID1 siRNA significantly reduced docetaxel efficacy (Figure 5C). Time course experiments indicated that the reduced chemosensitivity was accompanied by a significant reduction of docetaxel-induced cell death in si-ID1 cells compared to the si-Controls (Figure 5D).

4.

ID1 siRNA reduces docetaxel cytotoxicity in the LNCaP cell line. (A) Top: Representative western blot of ID1 expression in LNCaP cells treated with siRNA non-targeting control (si-Control) or siRNA ID1 (si-ID1) for 2 days, followed by 20 nM of DTX or solvent for 2 more days. Bottom: LNCaP cells were treated with si-Control or si-ID1, and cell proliferations were measured over a period of 48 hours based on viable cell numbers. ** P < 0.01, t-test. (B) Cells were transfected with siRNA oligos for 48 hours, and treated with docetaxel at the indicated doses for another 48 hours. The viability was calculated based on viable cell numbers at each dose adjusted to the solvent (0 nM) controls. * P < 0.01, ANOVA. (C-D) Cells were treated with siRNA and docetaxel (20 nM) for 48 hours as in (B), and flow cytometry was used to measure the % of cell death (C) and at G1 (D). ** P < 0.01, *, # P < 0.05, t-test. All results are mean and SD of 4 independent experiments.

5.

ID1 siRNA reduces docetaxel sensitivity in the prostate cancer C42B cell line. (A) Representative western blots of ID1 in LNCaP and C42B cell lines (top) and after C42B cells were treated by DTX at the indicated doses for 48 hours (bottom). (B) C42B cells were treated with si-Control or si-ID1, and cell proliferations were measured over a period of another 48 hours based on viable cell numbers. * P < 0.05, t-test. (C) Cells were first transfected with siRNA oligos for 48 hours, and then treated with docetaxel at the indicated doses for 24 hours. The viability was calculated based on viable cell numbers at each dose adjusted to the solvent (0 nM) controls. * P < 0.01, t-test. (D) Cells were treated with siRNA and docetaxel (10 nM) for either 24 or 48 hours as in (C), and flow cytometry was used to measure the % of cell death * P < 0.01, t-test. All results are mean and SD of 4 independent experiments.

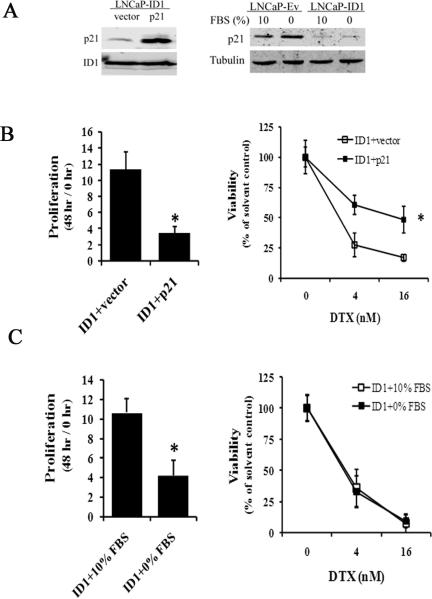

ID1 sensitizes LNCaP cells to docetaxel via p21 inhibition

To elucidate the potential mechanisms that are responsible for ID1-enhanced docetaxel sensitivity in LNCaP cells, we compared gene and/or protein expression of genes involved in androgen signaling, cytotoxic responses, and cell cycle / cell death regulation in the LNCaP-Ev and LNCaP-ID1 cell lines. There was no significant change in androgen receptor, p16, p27, Bad, Bax, BCL2 and BCL-xl gene expression (S8). On the other hand, AKT and JNK signaling in LNCaPID1 cells were higher than LNCaP-Ev in solvent treated conditions (S9). Consistent with a previous report 22, PSA expression was significantly upregulated (S8). However, under both androgen stimulated (1 nM R1881) and depleted (charcoal - striped serum) conditions, ID1 overexpression equally enhanced the docetaxel sensitivity (S10). Thus the investigated - ID1 pathway appears to be independent of androgen / AR pathway. Consistent with the function in repressing cyclin dependent kinase inhibitors, ID1 overexpression repressed p21 expression in LNCaP-ID1 cells (S9). Because p21 has been shown to attenuate chemotherapy cytotoxicity by inducing cell cycle arrest but not cell death 40-42, we hypothesized that the ID1-initiated reduction of p21 was one of the causes for the enhanced docetaxel sensitivity in LNCaP-ID1 cell line. Indeed, the LNCaP-ID1 cells compensated with stable lentiviral p21 overexpression had higher p21 protein levels (Figure 6A, left), grew significantly slower (Figure 6B, left), and were significantly less sensitive to docetaxel compared to the LNCaP-ID1 cells transduced with a vector control (Figure 6B, right). Since the rate of cell cycle can also play a role in chemosensitivity 43 and the LNCaP-ID1cells grew much faster than LNCaP-Ev (Figure 3A, left), we wanted to determine if the loss of docetaxel sensitivity can be recapitulated by merely inhibiting the cell cycle and proliferation without compensating for p21. We cultured LNCaP-ID1 cells under fetal bovine serum (FBS)-depleted condition for 48 hours. Western blot analyses revealed that p21 levels were not significantly changed (Figure 6A, right). Cell proliferation experiments showed significant growth retardation due to FBS depletion (Figure 6C, left). However, docetaxel induced similar levels of cytotoxicity in both fast-proliferating and slow-proliferating LNCaP-ID1 cells (Figure 6C, right). These data indicate that elevated cell proliferation rates do not account for enhanced chemosensitivity to docetaxel. On the other hand, the ID1-initiated p21 inhibition does contribute to both enhanced cell proliferation and docetaxel sensitivity.

6.

ID1mediates docetaxel sensitivity via down regulating p21. (A) Left: A representative western blot shows the p21 levels in LNCaP-ID1 cells stably transduced with lentivirus containing either vector or p21. Right: A representative western blot shows the p21 level in LNCaP-Ev and LNCaP-ID1 cultured in media containing 10% FBS or 0% FBS. (B) Left: Cell proliferation was measured in LNCaP-ID1 cells stably transfected with vector or p21 overexpression over a 48 hour period. Right: LNCaP-ID1 cells containing stable p21 overexpression (ID1+p21) or vector (ID1+vector) were treated with the docetaxel at the indicated doses for 48 hours. The viability was calculated based on viable cell numbers at each dose adjusted to the solvent (0 nM) controls. * P < 0.01, t-test. (C) Left: The proliferation was measured in LNCaP-ID1 cells cultured in media containing either 10% or 0% FBS over a 48 hour period. * P < 0.01, t-test. Right: LNCaP-ID1 cells cultured in either 10% or 0% FBS were treated with the docetaxel at the indicated doses for 48 hours. The viability was calculated based on viable cell numbers at each dose adjusted to the solvent (0 nM) controls. All results are mean and SD of 3 independent experiments.

DISCUSSION

In the current study, we identified ID1 as a molecular enhancer of docetaxel cytotoxicity. Prostate cancer cells with stable overexpression of ID1 exhibited higher sensitivity to docetaxel than empty vector controls. This enhanced sensitivity was accompanied by increases in BCL2 phosphorylation, caspase-3 activation, PARP cleavage, and ultimately cell death. Being an important transcriptional regulator of cell differentiation, ID1 was expected to affect multiple pathways, which may in turn influence chemosensitivity. One of these pathways was investigated here. Consistent with previous reports, stable ID1 overexpression significantly decreased the expression of the cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 in the LNCaP cell line. This led to increased cell proliferation and cell cycle progression, but also enhanced cytotoxicity to docetaxel. We used serum starvation to slow down the LNCaP-ID1 cell cycle progression and proliferation, and found that the slow-proliferating cells were equally sensitive to docetaxel as the fast-proliferating ones. However, stable p21 overexpression reversed the enhanced cytotoxicity. This suggests that ID1-modulation of chemosensitivity is proliferation independent, but p21 dependent.

The casual relationship of ID1-p21 pathway and chemosensitivity enhancement is consistent with the observations made more than a decade ago, in which the p53 and / or p21 negative cancer cell lines were prone to apoptosis in response to cytotoxic chemotherapy 40-42. Numerous studies have shown that p21 is capable of blocking caspase activation induced by both intrinsic and extrinsic cell death signals. The cell cycle regulatory property of p21 was recently separated from its anti-apoptotic function, in which investigators observed that a small deletion of the p21 protein disrupted its ability to inactivate the ASK1/Jun N-terminal protein kinase (JNK) pathway, but not the ability to initiate cell cycle arrest 44. The JNK pathway has been shown to mediate the cytotoxicity of docetaxel. We speculate that one way for ID1 to chemosensitize cells is to down regulate p21, which may lead to longer and / or more robust activation of JNK signaling as seen in S8 45, 46. In addition, we showed that docetaxel-induced ID1 expression was associated with the increased c-Myc binding at the ID1 promoter E-box. While c-Myc is usually associated with cancer cell proliferation, Myc can also induce synthetic lethality within specific p53 positive cellular contexts 47, 48. The LNCaP cell line has wild-type p53, and our current observation is consistent with a pathway that docetaxel induces ID1 expression via c-Myc. ID1 can subsequently inhibit p21, which promotes cell cycle progression, but also commits cells to death pathways in response to treatment. Additional mechanisms leading to ID1 chemosensitization may also exist due to the pleiotropic effect of ID1. In our study, most of the patients with ID1 upregulation also had ID3 upregulation after chemotherapy (S1).

The results of current study both confirm and argue against some of the existing knowledge regarding the status and function of ID1 in prostate cancer. Previously, ID1 protein overexpression has been observed in human prostate cancer specimens 49, 50. However, using matched benign and cancerous prostate epithelium obtained via LCM, we observed significantly higher ID1 mRNA expression in benign cells 30, and the tumor ID1 mRNA levels were higher in patients who were BCR-free (S11). ONCOMINE analysis also revealed that ID1 expression decreased as the disease progressed (S12). Using a more specific anti-ID1 antibody, we did not detect ID1 protein expression in localized prostate cancer tissues (data not shown), which confirmed a recently published histological study using the same antibodies 29. These data suggest to us that ID1 overexpression is not associated with the development of localized prostate cancer. Previous in vitro experiments have shown that ID1 overexpression enhances cell proliferation, activates several oncogenic signaling cascades, and promotes resistance to paclitaxel. In our study, we confirmed some of the proliferative and oncogenic properties of ID1. Further, using more detailed cellular and biochemical analysis, we showed that expression of ID1 increased prostate cancer cell line responses to docetaxel in contrast to the published reports. Part of the discrepancies between our data and prior studies may be due to differences in cell lines. Based on our observation that clinical prostate cancers had low ID1 expression levels, we chose LNCaP as the primary in vitro model because it has the lowest ID1 mRNA and protein level among all the prostate cancer cell lines tested. In other studies, investigators primarily used DU-145 and PC-3, which have measurable levels of ID1 protein and a loss of wild-type p53 function.

These in vitro and in vivo results suggest a potentially important clinical role for ID1 in cancer therapy. Currently, docetaxel-based chemotherapy is widely used in treating cancer, however, the therapeutic efficacy has been hard to predict. Based on the current results, ID1 mRNA expression may prove useful as a molecular predictor for docetaxel efficacy in cancer patients after chemotherapy or as a pre-treatment marker to select cancer patients who may be more responsive to specific cytotoxic agents. Further study using larger independent patient sets would be necessary to confirm this hypothesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Supported in part by grant GIA US #16080 from Aventis Pharmaceuticals, grant #031.G0008 from Serono, Inc., and NIH grants 3M01RR00334-33S2, 1 R01 CA119125-01, U54CA126540, and the PNW Prostate SPORE CA97186.

We thank Dr. Rhoda Alani for lentiviral-ID1 overexpression vector, Dr. Linzhao Cheng for lentiviral control and packaging vectors, Drs. Fan Pan and Sushant Kachhap for technical assistance and discussion. All these investigators are at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine. We thank Celestia Higano at University of Washington for contributing to the design and sample collection of the clinical trial.

References

- 1.Tannock IF, de Wit R, Berry WR, et al. Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2004;351:1502–12. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa040720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Berthold DR, Pond GR, Soban F, de Wit R, Eisenberger M, Tannock IF. Docetaxel plus prednisone or mitoxantrone plus prednisone for advanced prostate cancer: updated survival in the TAX 327 study. J Clin Oncol. 2008;26:242–5. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2007.12.4008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mackler NJ, Pienta KJ. Drug insight: Use of docetaxel in prostate and urothelial cancers. Nat Clin Pract Urol. 2005;2:92–100. doi: 10.1038/ncpuro0099. quiz 1 p following 12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Febbo PG, Richie JP, George DJ, et al. Neoadjuvant docetaxel before radical prostatectomy in patients with high-risk localized prostate cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:5233–40. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Garzotto M, Myrthue A, Higano CS, Beer TM. Neoadjuvant mitoxantrone and docetaxel for high-risk localized prostate cancer. Urol Oncol. 2006;24:254–9. doi: 10.1016/j.urolonc.2005.11.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Magi-Galluzzi C, Zhou M, Reuther AM, Dreicer R, Klein EA. Neoadjuvant docetaxel treatment for locally advanced prostate cancer: a clinicopathologic study. Cancer. 2007;110:1248–54. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22897. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sikder HA, Devlin MK, Dunlap S, Ryu B, Alani RM. Id proteins in cell growth and tumorigenesis. Cancer Cell. 2003;3:525–30. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00141-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benezra R, Rafii S, Lyden D. The Id proteins and angiogenesis. Oncogene. 2001;20:8334–41. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lasorella A, Uo T, Iavarone A. Id proteins at the cross-road of development and cancer. Oncogene. 2001;20:8326–33. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1205093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Caldon CE, Swarbrick A, Lee CS, Sutherland RL, Musgrove EA. The helix-loop-helix protein Id1 requires cyclin D1 to promote the proliferation of mammary epithelial cell acini. Cancer Res. 2008;68:3026–36. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-3079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Alani RM, Young AZ, Shifflett CB. Id1 regulation of cellular senescence through transcriptional repression of p16/Ink4a. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:7812–6. doi: 10.1073/pnas.141235398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ciarrocchi A, Jankovic V, Shaked Y, et al. Id1 restrains p21 expression to control endothelial progenitor cell formation. PLoS ONE. 2007;2:e1338. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0001338. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Everly DN, Jr., Mainou BA, Raab-Traub N. Induction of Id1 and Id3 by latent membrane protein 1 of Epstein-Barr virus and regulation of p27/Kip and cyclin-dependent kinase 2 in rodent fibroblast transformation. J Virol. 2004;78:13470–8. doi: 10.1128/JVI.78.24.13470-13478.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hara E, Yamaguchi T, Nojima H, et al. Id-related genes encoding helix-loop-helix proteins are required for G1 progression and are repressed in senescent human fibroblasts. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:2139–45. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kim D, Peng XC, Sun XH. Massive apoptosis of thymocytes in T-cell-deficient Id1 transgenic mice. Mol Cell Biol. 1999;19:8240–53. doi: 10.1128/mcb.19.12.8240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parrinello S, Lin CQ, Murata K, et al. Id-1, ITF-2, and Id-2 comprise a network of helix-loop-helix proteins that regulate mammary epithelial cell proliferation, differentiation, and apoptosis. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:39213–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M104473200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tanaka K, Pracyk JB, Takeda K, et al. Expression of Id1 results in apoptosis of cardiac myocytes through a redox-dependent mechanism. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:25922–8. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.40.25922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lyden D, Hattori K, Dias S, et al. Impaired recruitment of bone-marrow-derived endothelial and hematopoietic precursor cells blocks tumor angiogenesis and growth. Nat Med. 2001;7:1194–201. doi: 10.1038/nm1101-1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sikder H, Huso DL, Zhang H, et al. Disruption of Id1 reveals major differences in angiogenesis between transplanted and autochthonous tumors. Cancer Cell. 2003;4:291–9. doi: 10.1016/s1535-6108(03)00245-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Minn AJ, Gupta GP, Siegel PM, et al. Genes that mediate breast cancer metastasis to lung. Nature. 2005;436:518–24. doi: 10.1038/nature03799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gupta GP, Perk J, Acharyya S, et al. ID genes mediate tumor reinitiation during breast cancer lung metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:19506–11. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0709185104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ling MT, Wang X, Lee DT, Tam PC, Tsao SW, Wong YC. Id-1 expression induces androgen-independent prostate cancer cell growth through activation of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGF-R). Carcinogenesis. 2004;25:517–25. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgh047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ling MT, Wang X, Ouyang XS, et al. Activation of MAPK signaling pathway is essential for Id-1 induced serum independent prostate cancer cell growth. Oncogene. 2002;21:8498–505. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ling MT, Wang X, Ouyang XS, Xu K, Tsao SW, Wong YC. Id-1 expression promotes cell survival through activation of NF-kappaB signalling pathway in prostate cancer cells. Oncogene. 2003;22:4498–508. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1206693. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lin JC, Chang SY, Hsieh DS, Lee CF, Yu DS. Modulation of mitogen-activated protein kinase cascades by differentiation-1 protein: acquired drug resistance of hormone independent prostate cancer cells. J Urol. 2005;174:2022–6. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000176476.14572.39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Di K, Ling MT, Tsao SW, Wong YC, Wang X. Id-1 modulates senescence and TGF-beta1 sensitivity in prostate epithelial cells. Biol Cell. 2006;98:523–33. doi: 10.1042/BC20060026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang X, Ling MT, Wang X, Wong YC. Inactivation of Id-1 in prostate cancer cells: A potential therapeutic target in inducing chemosensitization to taxol through activation of JNK pathway. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:2072–81. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Zhang X, Ling MT, Wang Q, et al. Identification of a novel inhibitor of differentiation-1 (ID-1) binding partner, caveolin-1, and its role in epithelial-mesenchymal transition and resistance to apoptosis in prostate cancer cells. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:33284–94. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M705089200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Perk J, Gil-Bazo I, Chin Y, et al. Reassessment of id1 protein expression in human mammary, prostate, and bladder cancers using a monospecific rabbit monoclonal anti-id1 antibody. Cancer Res. 2006;66:10870–7. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-2643. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Qian DZ, Huang CY, O'Brien CA, et al. Prostate cancer-associated gene expression alterations determined from needle biopsies. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:3135–42. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-1982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qian DZ, Wei YF, Wang X, Kato Y, Cheng L, Pili R. Antitumor activity of the histone deacetylase inhibitor MS-275 in prostate cancer models. Prostate. 2007;67:1182–93. doi: 10.1002/pros.20611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Myrthue A, Rademacher BL, Pittsenbarger J, et al. The Iroquois Homeobox Gene 5 Is Regulated by 1,25-Dihydroxyvitamin D3 in Human Prostate Cancer and Regulates Apoptosis and the Cell Cycle in LNCaP Prostate Cancer Cells. Clin Cancer Res. 2008;14:3562–70. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-4649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kim JW, Gao P, Liu YC, Semenza GL, Dang CV. Hypoxia-Inducible Factor 1 and Dysregulated c-Myc Cooperatively Induce Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor and Metabolic Switches Hexokinase 2 and Pyruvate Dehydrogenase Kinase 1. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:7381–93. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00440-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Qian DZ, Wang X, Kachhap SK, et al. The histone deacetylase inhibitor NVP-LAQ824 inhibits angiogenesis and has a greater antitumor effect in combination with the vascular endothelial growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor PTK787/ZK222584. Cancer Res. 2004;64:6626–34. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-0540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Huang CY, Beer TM, Higano CS, et al. Molecular alterations in prostate carcinomas that associate with in vivo exposure to chemotherapy: identification of a cytoprotective mechanism involving growth differentiation factor 15. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:5825–33. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-1037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lin DW, Coleman IM, Hawley S, et al. Influence of surgical manipulation on prostate gene expression: implications for molecular correlates of treatment effects and disease prognosis. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:3763–70. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2005.05.1458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Swarbrick A, Akerfeldt MC, Lee CS, et al. Regulation of cyclin expression and cell cycle progression in breast epithelial cells by the helix-loop-helix protein Id1. Oncogene. 2005;24:381–9. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1208188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zeller KI, Zhao X, Lee CW, et al. Global mapping of c-Myc binding sites and target gene networks in human B cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:17834–9. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604129103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Basu A, Haldar S. Microtubule-damaging drugs triggered bcl2 phosphorylation-requirement of phosphorylation on both serine-70 and serine-87 residues of bcl2 protein. Int J Oncol. 1998;13:659–64. doi: 10.3892/ijo.13.4.659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Waldman T, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B. p21 is necessary for the p53-mediated G1 arrest in human cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1995;55:5187–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bunz F, Dutriaux A, Lengauer C, et al. Requirement for p53 and p21 to sustain G2 arrest after DNA damage. Science. 1998;282:1497–501. doi: 10.1126/science.282.5393.1497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bunz F, Hwang PM, Torrance C, et al. Disruption of p53 in human cancer cells alters the responses to therapeutic agents. J Clin Invest. 1999;104:263–9. doi: 10.1172/JCI6863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Verheul HM, Qian DZ, Carducci MA, Pili R. Sequence-dependent antitumor effects of differentiation agents in combination with cell cycle-dependent cytotoxic drugs. Cancer Chemother Pharmacol. 2007;60:329–39. doi: 10.1007/s00280-006-0379-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zhan J, Easton JB, Huang S, et al. Negative regulation of ASK1 by p21Cip1 involves a small domain that includes Serine 98 that is phosphorylated by ASK1 in vivo. Mol Cell Biol. 2007;27:3530–41. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00086-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang TH, Wang HS, Ichijo H, et al. Microtubule-interfering agents activate c-Jun N-terminal kinase/stress-activated protein kinase through both Ras and apoptosis signal-regulating kinase pathways. J Biol Chem. 1998;273:4928–36. doi: 10.1074/jbc.273.9.4928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mhaidat NM, Zhang XD, Jiang CC, Hersey P. Docetaxel-induced apoptosis of human melanoma is mediated by activation of c-Jun NH2-terminal kinase and inhibited by the mitogen-activated protein kinase extracellular signal-regulated kinase 1/2 pathway. Clin Cancer Res. 2007;13:1308–14. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-06-2216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Seoane J, Le HV, Massague J. Myc suppression of the p21(Cip1) Cdk inhibitor influences the outcome of the p53 response to DNA damage. Nature. 2002;419:729–34. doi: 10.1038/nature01119. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Hernandez-Vargas H, Ballestar E, Carmona-Saez P, et al. Transcriptional profiling of MCF7 breast cancer cells in response to 5-Fluorouracil: relationship with cell cycle changes and apoptosis, and identification of novel targets of p53. Int J Cancer. 2006;119:1164–75. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ouyang XS, Wang X, Lee DT, Tsao SW, Wong YC. Over expression of ID-1 in prostate cancer. J Urol. 2002;167:2598–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Coppe JP, Itahana Y, Moore DH, Bennington JL, Desprez PY. Id-1 and Id-2 proteins as molecular markers for human prostate cancer progression. Clin Cancer Res. 2004;10:2044–51. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.ccr-03-0933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.