Abstract

It is well known that impacted biliary stones are difficult to remove endoscopically. Among the many factors associated with failure of endoscopic therapy for removal of bile duct stones, impaction ranks high. One of the reasons behind failure of endoscopic therapy in such cases is that the impacted stone often does not allow passage of a guidewire. Recent introduction of a novel single-operator cholangioscopy system has made it possible for a single endoscopist to use cholangioscopy for evaluation and treatment of a wide variety of biliary disorders. This cholangioscopy system was used for placement of a guidewire in the cystic duct remnant with subsequent removal of an impacted stone which had prevented passage of a guidewire by conventional means.

Keywords: Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography, Cholangioscopy, Guidewire, Choledocholithiasis, Cystic duct, Cystic duct remnant

INTRODUCTION

Choledocholithiasis is a common condition[1-5]. Most bile duct stones can be effectively removed by endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP)[6]. In the vast majority of cases, this is achieved after placement of a guidewire which is then used to guide instruments such as lithotripsy baskets or extraction balloons. Occasionally, when a stone is impacted, placement of a guidewire in the desired location cannot be accomplished, and more invasive procedures such as transhepatic access or surgery may become necessary. In this report, we describe a new technique for successful guidewire placement for subsequent treatment and removal of impacted stones after failed placement by conventional means.

CASE REPORT

A 64 year-old-man with a remote history of cholecystectomy was referred for ERCP for treatment of choledocholithiasis. The cholangiogram showed stones in the common hepatic duct and the cystic duct remnant (Figure 1). The common hepatic duct stones were easily removed after placement of a guidewire in the common hepatic duct followed by biliary sphincterotomy and balloon extraction. Removal of the stones in the cystic duct, however, proved to be much more challenging. One of the cystic duct stones was impacted at the insertion of the cystic duct to the common bile duct, preventing passage of a guidewire (Jagwire, Boston Scientific, Natick, MA; Figure 1). An extraction balloon which was already in place was inflated and the insertion point of the cystic duct was probed with the guidewire while changing the orientation and the degree of inflation of the balloon. The guidewire still would not pass. The balloon was then positioned close to the stone, inflated and slightly pulled down towards the ampulla to straighten and stretch the bile duct while probing with the guidewire was continued[7]. However, this technique also failed to provide access to the cystic duct. The balloon was then exchanged with a rotatable sphincterotome (Autotome Rx, Boston Scientific, Natick, MA). This sphincterotome has a rotating handle which is designed to change the tip orientation to facilitate cannulation. Probing with the guidewire through the sphincterotome at different tip orientations also failed. The guidewire was then exchanged for an angled tip hydrophilic guidewire (Hydra Jagwire, Boston Scientific, Natick, MA) and the sequence described above was repeated without success. After failing to traverse the stone by conventional means, a cholangioscope (SpyGlass Direct Visualization System, Boston Scientific, Natick, MA) was introduced into the bile duct. Through the accessory channel of the cholangioscope, under direct visualization and using low volume saline irrigation, a hydrophilic guidewire was manipulated past the impacted stone and placed in the cystic duct remnant (Figure 2). The cholangioscope was then removed and the stones were extracted using a basket passed over the guidewire (Figure 3).

Figure 1.

Fluoroscopic image obtained during ERCP showing filling defects (stones) in the common hepatic duct and cystic duct remnant.

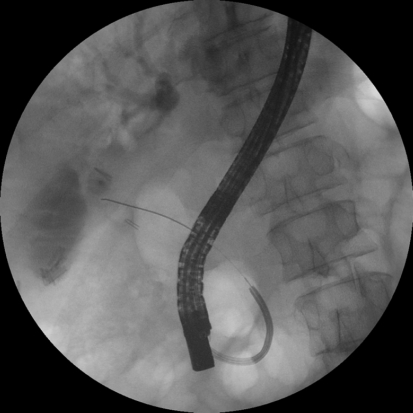

Figure 2.

A guidewire is placed in the cystic duct remnant under direct cholangioscopic guidance.

Figure 3.

A guidewire is coiled in the cystic duct remnant. A basket passed over the guidewire is holding a large radiolucent (cholesterol) stone for removal.

DISCUSSION

Gallstone disease or cholelithiasis continues to be a major health problem throughout the world, affecting approximately 10%-20% of the Caucasian population[8]. In addition, 15%-20% of patients with gallstone disease also have stones in their biliary ductal system (choledocholithiasis)[5]. Stones in the biliary ductal system have to be removed because of their potential to cause cholangitis and pancreatitis[6,9,10]. ERCP with biliary sphincterotomy and stone extraction are well-established therapeutic procedures for the treatment of gallstones. Appropriate guidewire placement is a requirement in most ERCP procedures that are performed for gallstone extraction. In most cases, guidewire placement is accomplished easily. In some cases, however, it can represent a time-consuming challenge. Multiple instruments have been developed and several techniques have been described to help with guidewire placement during ERCP. Despite use of different equipment and innovative techniques, a guidewire sometimes can not be placed in the desired location and a more invasive procedure may become necessary.

Recently, a new single-operator cholangioscopy system became available (SpyGlass Direct Visualization System, Boston Scientific, Natick, MA, USA)[11,12]. This system, which consists of re-useable and single use components, allows direct visualization of the biliary tree by a single endoscopist. Its other advantages are a 4-way tip deflection, which allows better access and maneuverability, and 2 dedicated irrigation channels allowing better visualization of intraductal pathology. I and my colleagues have previously reported our experience with this system in the treatment of difficult to remove biliary stones[13], evaluation of indeterminate biliary strictures[14], investigation of “idiopathic” recurrent acute pancreatitis[15] and treatment of anastomotic strictures in liver transplant patients[16]. This study reports the experience of using this device for removal of impacted stones in the cystic duct remnant. Most symptomatic patients with calculi in the cystic duct remnant undergo laparoscopic re-operation for stone management[17-19]. In this case, this peroral cholangioscopy system was used to place a guidewire in the cystic duct remnant under direct visualization after a failed attempt during ERCP, with subsequent removal of an impacted calculus. This innovative technique allows surgery to be avoided in selected cases.

Footnotes

Peer reviewers: Dr. Jean L Frossard, Division of Gastroenterology, Geneva University Hospital, Rue Micheli du Crest, 1211 Geneva 14, Switzerland; Beata Jolanta Jablońska, MD, PhD, Department of Digestive Tract Surgery, University Hospital of the Medical University of Silesia, Medyków 14 St. 40-752 Katowice, Poland

S- Editor Li LF L- Editor Cant MR E- Editor Lin YP

References

- 1.Everhart JE, Khare M, Hill M, Maurer KR. Prevalence and ethnic differences in gallbladder disease in the United States. Gastroenterology. 1999;117:632–639. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(99)70456-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Everhart JE, Yeh F, Lee ET, Hill MC, Fabsitz R, Howard BV, Welty TK. Prevalence of gallbladder disease in American Indian populations: findings from the Strong Heart Study. Hepatology. 2002;35:1507–1512. doi: 10.1053/jhep.2002.33336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aerts R, Penninckx F. The burden of gallstone disease in Europe. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2003;18 Suppl 3:49–53. doi: 10.1046/j.0953-0673.2003.01721.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Festi D, Dormi A, Capodicasa S, Staniscia T, Attili AF, Loria P, Pazzi P, Mazzella G, Sama C, Roda E, et al. Incidence of gallstone disease in Italy: results from a multicenter, population-based Italian study (the MICOL project) World J Gastroenterol. 2008;14:5282–5289. doi: 10.3748/wjg.14.5282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tazuma S. Gallstone disease: Epidemiology, pathogenesis, and classification of biliary stones (common bile duct and intrahepatic) Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;20:1075–1083. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2006.05.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caddy GR, Tham TC. Gallstone disease: Symptoms, diagnosis and endoscopic management of common bile duct stones. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2006;20:1085–1101. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2006.03.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ersoz G, Tekin F, Ozutemiz O, Tekesin O. A novel technique for biliary strictures that cannot be passed with a guide wire. Endoscopy. 2007;39 Suppl 1:E332. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-966559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Steiner CA, Bass EB, Talamini MA, Pitt HA, Steinberg EP. Surgical rates and operative mortality for open and laparoscopic cholecystectomy in Maryland. N Engl J Med. 1994;330:403–408. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199402103300607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Forsmark CE, Baillie J. AGA Institute technical review on acute pancreatitis. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:2022–2044. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.03.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moreau JA, Zinsmeister AR, Melton LJ 3rd, DiMagno EP. Gallstone pancreatitis and the effect of cholecystectomy: a population-based cohort study. Mayo Clin Proc. 1988;63:466–473. doi: 10.1016/s0025-6196(12)65644-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen YK, Pleskow DK. SpyGlass single-operator peroral cholangiopancreatoscopy system for the diagnosis and therapy of bile-duct disorders: a clinical feasibility study (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:832–841. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2007.01.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chen YK, Parsi MA, Binmoeller KF, Hawes RH, Pleskow D, Slivka A, Haluszka O, Petersen BT, Sherman S, Deviere J, et al. Peroral cholangioscopy (PO) using a disposable steerable single operator catheter for biliary stone therapy and assessment of indeterminate strictures - A multicenter experience using Spyglass. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:AB103. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Parsi MA, Neuhaus H, Pleskow D, Binmoeller KF, Hawes RH, Petersen BT, Sherman S, Stevens PD, Deviere J, Haluszka O, et al. Peroral Cholangioscopy Guided Stone Therapy - Report of an International Multicenter Registry. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:AB102. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pleskow D, Parsi MA, Chen YK, Neuhaus H, Slivka A, Haluszka O, Petersen BT, Deviere J, Sherman S, Meisner S, et al. Biopsy of indeterminate biliary strictures - does direct visualization help? - A multicener experience. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:AB103. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parsi MA, Sanaka MR, Dumot JA. Iatrogenic recurrent pancreatitis. Pancreatology. 2007;7:539. doi: 10.1159/000108972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Parsi MA, Guardino J, Vargo JJ. Peroral cholangioscopy-guided stricture therapy in living donor liver transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2009;15:263–265. doi: 10.1002/lt.21584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tantia O, Jain M, Khanna S, Sen B. Post cholecystectomy syndrome: Role of cystic duct stump and re-intervention by laparoscopic surgery. J Minim Access Surg. 2008;4:71–75. doi: 10.4103/0972-9941.43090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Palanivelu C, Rangarajan M, Jategaonkar PA, Madankumar MV, Anand NV. Laparoscopic management of remnant cystic duct calculi: a retrospective study. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2009;91:25–29. doi: 10.1308/003588409X358980. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lum YW, House MG, Hayanga AJ, Schweitzer M. Postcholecystectomy syndrome in the laparoscopic era. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2006;16:482–485. doi: 10.1089/lap.2006.16.482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]