Abstract

The low level of oxygenation within tumors is a major cause of radiation treatment failures. We theorized that anaerobic bacteria that can selectively destroy the hypoxic regions of tumors would enhance the effects of radiation. To test this hypothesis, we used spores of Clostridium novyi-NT to treat transplanted tumors in mice. The bacteria were found to markedly improve the efficacy of radiotherapy in several of the mouse models tested. Enhancement was noted with external beam radiation derived from a Cs-137 source, systemic radioimmunotherapy with an I-131-conjugated monoclonal antibody, and a previously undescribed form of experimental brachytherapy using plaques loaded with I-125 seeds. C. novyi-NT spores added little toxicity to the radiotherapeutic regimens, and the combination resulted in long-term remissions in a significant fraction of animals.

More than 25% of adults in developed countries will develop a malignant tumor, and nearly half of these patients are likely to be treated with some form of radiation therapy (1). Radiation was the first effective adjuvant treatment for cancer, and numerous improvements over the past several decades have made it a mainstay of oncology. However, the effects of radiation are often transient, stimulating intensive searches for agents that can synergize with it (2–4).

It is well known that the efficient killing of cells by radiation requires oxygen (1). Experimental studies have shown that hypoxic cells are up to three times more resistant to ionizing radiation than normoxic cells (4, 5). Accordingly, the existence of hypoxic regions in tumors is a major cause of treatment failures. Studies in patients with cervical cancer have demonstrated that intratumoral oxygen tension is the most important prognostic factor in predicting overall as well as disease-free survival after radiation treatment (6). These observations have spurred attempts to increase intratumoral oxygenation and to combine radiation with radiosensitizing agents. Although some of these approaches appear promising, locoregional recurrences have remained a major problem, limiting gains in overall survival (7).

Anaerobic bacteria are capable of targeting and destroying the hypoxic regions of experimental tumors when systemically injected into mice (8). This suggests that such bacteria might enhance the therapeutic effects of radiation by killing those regions of tumors that are resistant to radiation therapy due to their low oxygen content. In the current study, we tested this hypothesis in mice by using Clostridium novyi-NT, an anaerobic bacteria devoid of its major toxin gene (9). These bacteria were used in conjunction with each of the three major modes of radiation therapy: external beam, brachytherapy, and radioimmunotherapy (RAIT). We found that the bacteria markedly enhanced the efficacy of all three forms of radiotherapy.

Materials and Methods

Cell Lines. HCT116 (CCL-247), HT-29 (HTB-38), Calu-3 (HTB-55), LS174T (CL-188), B16 (CRL-6322), and CT26 (CRL-2638) were purchased from American Type Culture Collection. HuCC-T1 was the kind gift of Anirban Maitra and Ralph Hruban (10), and VX2 was provided by J. A. Hilton (all at Johns Hopkins Medical Institutions, Baltimore). All cell lines were grown in McCoy's 5A Medium (Invitrogen) supplemented with 5% FBS (HyClone) at 37°C with 5% CO2.

Tumor Inoculation and Spore Administration. All animal experiments were overseen and approved by the Animal Welfare Committee of the Johns Hopkins University and were in compliance with university standards. Six- to 8-wk-old mice, purchased from Harlan Breeders (Indianapolis), were used for tumor implantation studies. C57BL/6 mice were used to establish B16 tumors, BALB/C mice were used to establish CT26 tumors, and athymic nu/nu mice were used for human xenografts. A minimum of six mice were used for each experimental arm. Five million cells were injected s.c. into the right flank of each mouse. Tumor volume was calculated as length × width2 × 0.5. For all experiments, mice were randomized into various treatment arms after tumors reached an average volume of ≈400 mm3. C. novyi-NT spores were prepared as described (9). Mice were injected with 300 million spores suspended in 500 μlofPBS (10010-023, Invitrogen) via the tail vein.

External Beam Radiation. Mice were immobilized by using a shielded restrainer, which allowed the tumors to be exposed while sparing the areas surrounding the tumor. A Shephard irradiator (JL Shephard, Glendale, CA) with a Cs-137 source that delivers 0.1 Gy per second was used for external beam experiments. The aperture of the source was opened to the minimal level required to expose the entire tumor.

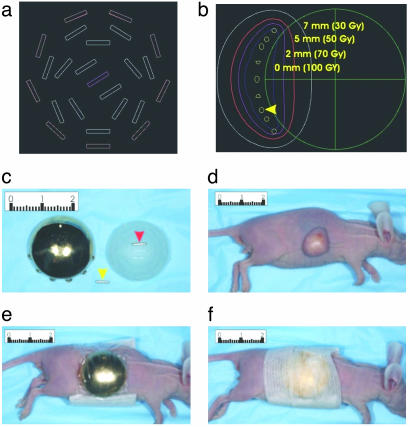

Brachytherapy. Twenty-millimeter gold shields (no. 1080.3) and 20-mm seed carriers (no. 1080.2) were purchased from Trachsel (Rochester, MN). OncoSeeds I-125 (model no. 6711), with initial activity of 0.789 mCi/seed, were purchased from Amersham Pharmacia. The initial activity was selected to deliver 10 Gy/day at 5-mm depth below the surface of the skin by using a dosage-simulating computer program developed in-house (see Fig. 7 a and b). The mice were anesthetized with a s.c. injection of ketamine (10–15 μl at 100 mg/ml). The plaques were applied to the tumors by using SorbaView 2000 (3M Co., no. SV40XT) and reinforced with Steri-Strip (Centurion, Howell, MI, no. R1547), as illustrated in Fig. 7 c–f.

Fig. 7.

Eye plaques for brachytherapy of experimental tumors in mice. (a) Schematic of eye plaque showing each of the 24 grooves where the I-125 OncoSeeds are placed. (b) Computer-generated schematic of a sagittal section through the center of an eye plaque overlying a xenograft. The isodose curves represent the dose prescribed (over 5 days) along the curve at a particular depth below the plaque. Note that 50 Gy is delivered to 5-mm depth and the rapid decrease in dose moving away from the I-125 OncoSeeds (yellow arrowhead). (c) An I-125 OncoSeed (yellow arrowhead), an eye plaque containing a single I-125 OncoSeed (red arrowhead) that fits into the grooves on the eye plaque, and a gold shield capping an eye plaque. The eye plaques actually used to deliver the dose contained 24 OncoSeeds. (d) A mouse bearing an HCT116 xenograft before brachytherapy. (e) The same mouse after the gold shield-encased eye plaque was placed on the tumor and wrapped with SorbaView 2000 (Tri-State Hospital Supply, Howell, MI). (f) The same mouse after wrapping with Steri-Strip. Numbers on rulers indicate centimeters.

RAIT. A myeloma clone secreting anticarcinoembryonic antigen (anti-CEA) mAb T84.66 was purchased from American Type Culture Collection. One hundred micrograms of purified antibodies in 100 μl of PBS was added to an iodogen-coated tube (Pierce). Fifteen microcuries of I-125 iodide (Perkin–Elmer) or 30 mCi of I-131 iodide (Amersham Pharmacia), dissolved in 100 μl of PBS, was then added and incubated at room temperature for 10 min. Bound radioiodine was separated from free iodide by using a PD-10 column (Pharmacia Fine Chemicals, Piscataway, NJ). Percent radioiodine binding, determined by trichloroacetic acid precipitation, was >95%. The specific activity of I-125- and I-131-labeled antibodies was 88 and 210 μCi per microgram protein, respectively.

For biodistribution studies, 2 μCi of I-125-labeled T84.66 was injected through the tail vein into mice bearing s.c. LS174T colon cancer xenografts. Twenty-four and 96 h later, mice were euthanized by CO2 narcosis, and tissues were harvested and assayed with a γ counter. For the RAIT study, tumor-bearing mice were injected via the tail vein with 500 μCi of I-131-labeled T84.66 mAb. This dose was chosen after pilot studies determined that 600 μCi resulted in the deaths of two of five treated mice.

Light Microscopy. Hematoxylin/eosin (H&E) and Gram staining were performed as described (9). Immunofluorescence was performed on 6-μm-thick paraffin sections. After deparaffinization and rehydration of the sections, antigen retrieval was accomplished by incubating slides for 30 min in Citrate Buffer Solution (no. 00-500, Zymed) in a bath at 95°C. After removal from the bath, the slides were left to cool at room temperature for 30 min. All subsequent steps were performed at room temperature. Nonspecific immunoreactivity was blocked for 60 min with CTE (1% casein in 100 mM Tris·HCl, pH 7.5/150 mM NaCl). The primary antibody was a polyclonal antiserum derived from a New Zealand White rabbit immunized with vegetative C. novyi-NT. This antibody was applied for 30 min at a dilution of 1:50 in CTE. After three washes of 3 min each with TBST (50 mM Tris·HCl/300 mM NaCl/0.1% Tween 20, pH 7.6), the sections were incubated for 30 min with a biotinylated goat anti-rabbit antibody (Pierce, no. 31822), diluted 1:100 in CTE. After washing as above, the sections were incubated for 30 min with rhodamine-conjugated streptavidin (Pierce, no. 21724) diluted 1:500 in CTE.

Glucose transporter 1 (Glut-1) staining was performed similarly with the following exceptions. After antigen retrieval and blocking, sections were incubated for 30 min with Peroxidase Blocking Reagent (DAKO, no. 003715). The primary antibody was a rabbit anti-human Glut-1 (DAKO, no. A3536); the secondary antibody was the same as for immunofluorescence; and the tertiary antibody was an alkaline phosphatase-conjugated rabbit antibiotin antibody (DAKO, no. D5107). For color development, the slides were incubated for 5–10 min in BCIP/NBT liquid substrate solution (Sigma, no. B-1911). The sections were counterstained with hematoxylin.

For Movies 1 and 2 (which are published as supporting information on the PNAS web site), HCT116 xenografts were treated with 300 million C. novyi-NT spores for 36 h. The bacteria were aspirated from the tumor and placed on a glass slide. Time-lapse phase microscopy was performed at ×100 and ×400.

Electron Microscopy. Bacteria were grown overnight in reinforced clostridial media (Difco). Early log-phase cells were allowed to adsorb to 300 mesh formvar/carbon-coated nickel grids for 10 min and were washed briefly in 100 mM cacodylate buffer, pH 7.4. Adhered cells (on grids) were then fixed in 2% glutaraldehyde contained in 100 mM cacodylate buffer, pH 7.4, for 10 min, washed briefly in H2O, dehydrated through a graded series of ethanol washes, and subsequently placed in 50% hexamethyldisilazane (HMD). After two brief washes in 100% HMD, grids were allowed to dry slowly, then were placed in a DV-502A high-vacuum evaporator (Denton Vacuum, Moorestown, NJ) and rotary shadowed with platinum at an angle of 20°. Grids were examined in a Philips (Eindhoven, The Netherlands) EM 410 transmission electron microscope at 100 kV, and images were recorded with a Megaview III digital camera (Soft Imaging System, Lakewood, CO).

Statistical Analysis. Progression-free survival among treatment groups was compared by using Kaplan–Meier curves. Statistical significance was assessed by using the log-rank test. Longitudinal data on tumor sizes were analyzed by performing a linear regression analysis of each animal. The P value was then determined by using Student's t test on the linear regression slope for each individual mouse. Each treatment arm was compared with the arm involving C. novyi-NT plus radiation. The fit of the animal specific regressions was generally good, with R2 values ranging from 0.99 to 0.80.

Results

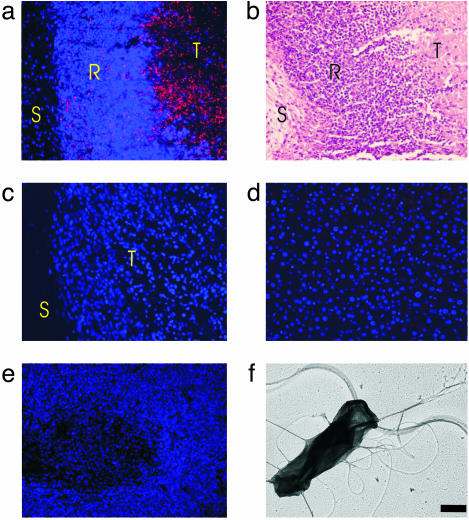

Effects of C. novyi-NT When Administered Alone. C. novyi-NT bacteria are exquisitely sensitive to oxygen, dying within a few minutes of exposure to room air. In contrast, spores of this organism are stable to oxygen as well as to heat, chemicals, and other noxious experimental conditions. As shown (9), when C. novyi-NT spores are injected i.v. into nude mice bearing human colorectal cancer xenografts (HCT116), germination occurs exclusively within the tumors. The process begins within 12 h of injection and is florid by 24 h. The presence of germinated bacteria could be demonstrated by both culture of organisms from the tumors and immunofluorescence microscopy performed with an antibody generated against the vegetative form of the bacteria (Fig. 1 a–c). No germination was evident in the liver and spleen, the major sites of spore clearance (Fig. 1 d and e). The bacteria were dispersed throughout the tumor, an effect likely due to their highly motile nature (Movies 1 and 2). The large number of peritrichous flagella distributed on the surface of the vegetative bacteria were responsible for this motility (Fig. 1f). Even so, a rim of viable tumor was almost always left after treatment with the spores (Fig. 2c), limiting the extent and duration of the therapeutic response.

Fig. 1.

Effects of C. novyi-NT on HCT116 xenografts. (a) Immunofluorescence of tumor 24 h after i.v. injection of C. novyi-NT spores. Extensive germination (red dots and rods) is evident within the body of the tumor (T), whereas remaining bacteria are trapped by inflammatory cells at the rim (R). No bacteria penetrate through the rim to the stroma (S) between the tumor and overlying skin. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33528 in a and c–e. (b) An adjacent section of tumor was stained with H&E. (c) Immunofluorescence in another xenograft in a mouse not treated with spores. No bacteria are observed. (d and e) Immunofluorescence of liver and spleen, respectively, from a mouse treated with C. novyi-NT spores. Bacteria are not observed. (f) Electron micrograph of vegetative C. novyi-NT, showing numerous peritrichous flagella. (Bar = 0.5 μm.)

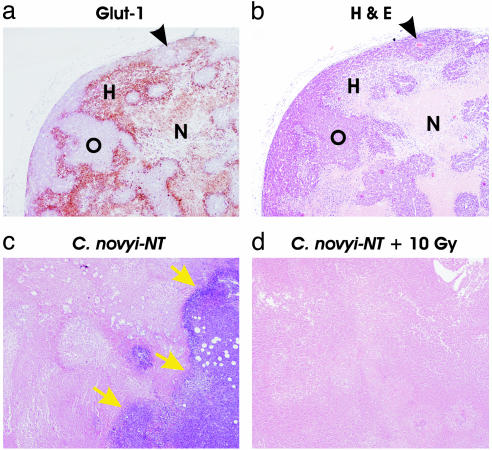

Fig. 2.

Histologic examination of HCT116 xenografts before and after treatment. (a) Glut-1 staining of untreated HCT116 xenograft revealing islands of well oxygenated cells (O) interspersed within regions of hypoxia (H). In some cases, blood vessels could be observed in the middle of the islands (arrowheads in a and b). Necrotic regions (N) are poorly stained for Glut-1. (b) H&E stain of a serial section of xenograft shown in a.(c) H&E stain of HCT116 tumor xenograft 96 h after i.v. injection of spores, showing extensive central necrosis and remaining viable tumor rim (arrows). (d) H&E stain of HCT116 tumor xenograft 96 h after i.v. injection of spores when given in combination with external beam radiation. No viable tumor cells could be observed on several sections throughout the tumor. (Original magnification, ×40.)

Effects of C. novyi-NT When Given in Combination with External Beam Radiation. Human tumor xenografts, like the cancers from which they are derived, display a heterogeneous pattern of oxygenation. This can be demonstrated by staining with an antibody directed against Glut-1, a protein induced by hypoxia (Fig. 2 a and b) (11). The islands of well-vascularized (nonstaining) cells were often observed to contain blood vessels at their center. To determine whether C. novyi-NT plus irradiation could together eliminate both the well vascularized and poorly vascularized regions of these tumors, we initially performed studies to find the optimum timing for treatment with these two agents. Mice bearing dorsal s.c. HCT116 xenografts were irradiated with an external beam (Cs-137) after shielding the animals posterior and anterior to the tumor. The maximum total dose of external beam radiation that could be delivered without causing significant morbidity was ≈10 Gy. Several fractionation procedures were evaluated, with spores given before the first fraction, after the last fraction, or between intermediate fractions. Although the spores significantly enhanced the effect of radiation in most of these tests, optimum results were obtained with a protocol using five daily doses of 2 Gy each, with spores administered between the third and fourth doses.

This combination therapy produced remarkable tumor shrinkage in mice bearing HCT116 tumors (Fig. 3a). This shrinkage was evident on gross inspection (Fig. 4), and microscopic sections stained with H&E revealed complete or nearly complete lysis of all tumor cells (Fig. 2d). There was no evident dependence on tumor size; tumors ranging from 50 to 1,000 mm3 responded similarly to the combination treatment.

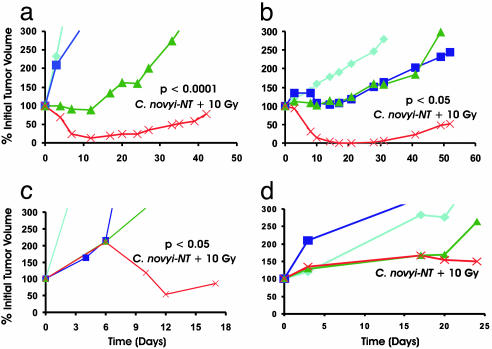

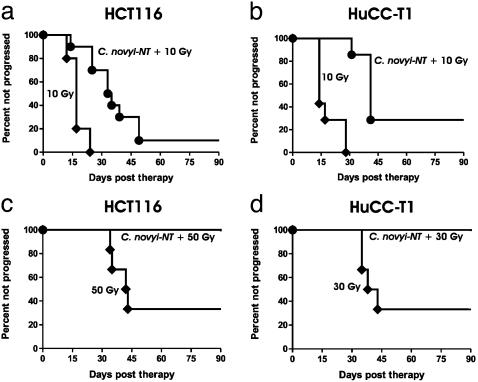

Fig. 3.

Effect of C. novyi-NT plus external beam radiation on various transplanted tumor models after the indicated treatments. a, HCT116; b, HuCC-T1; c, B16; d, HT29. Irradiated mice received 2 Gy/day for 5 days. Spores were administered after the third dose of radiation. Tumor growth curves are color-coded: light blue, untreated control; purple, C. novyi-NT spores alone; green, radiation (10 Gy) alone; red, radiation (10 Gy) plus C. novyi-NT spores. Each group contained at least six mice. Student's t test was performed by using the linear regression slope for each individual mouse. Each arm was compared with the combination of C. novyi-NT plus 10 Gy, and all were statistically significant in a–c. The P values for comparison between irradiation alone and irradiation plus C. novyi-NT were as follows: a, P < 0.0001; b, P < 0.05; and c, P < 0.05.

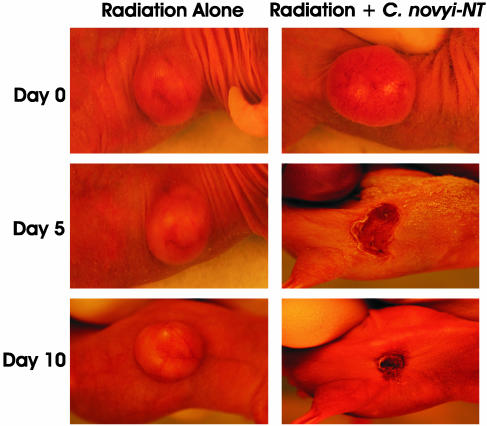

Fig. 4.

Photographs of mice with HCT116 xenografts receiving external beam irradiation with or without C. novyi-NT spores. (Left) A mouse that received 2 Gy external beam radiation per day for 5 days beginning on day 0. (Right) A mouse that received the same dose of radiation but additionally received i.v. C. novyi-NT spores after the third dose of radiation.

We next tested several other tumor models to determine whether C. novyi-NT could enhance the effects of radiation administered by external beam (see examples in Fig. 3 b–d and Fig. 5). C. novyi-NT spores significantly enhanced the effects of radiation in the human biliary cancer HuCC-T1, the mouse melanoma B16, and the rabbit squamous cell carcinoma VX2 (data not shown). However, the human colorectal cancer cell line HT-29 and the human lung cancer Calu-3 (data not shown) were found to be unresponsive to C. novyi-NT spores when used alone, and the spores did not enhance the effects of radiation. Conversely, mouse colon cancer CT26 was unresponsive to 10 Gy of irradiation when used alone, and this dose of radiation did not enhance the effects of C. novyi-NT spores (data not shown).

Fig. 5.

Photographs of mice with HuCC-T1 xenografts receiving external beam irradiation with or without C. novyi-NT spores. (Left) A mouse that received 2-Gy external beam radiation per day for 5 days beginning on day 0. (Right) A mouse that received the same dose of radiation but additionally received i.v. C. novyi-NT spores after the third dose of radiation.

Effects of C. novyi-NT When Given in Combination with Brachytherapy. The results recorded in Figs. 2, 3, 4, 5 showed that C. novyi-NT could substantially improve the effects of external beam irradiation. However, the small number of residual tumor cells eventually proliferated, causing tumor recurrence even in those models that were most sensitive to the combination therapy, such as HCT116 and HuCC-T1 (Fig. 6 a and b, respectively). We suspected that higher doses of radiation would be able to result in more cures, but we could not deliver higher doses of radiation with external beam because of the toxicity to internal organs. This toxicity was observed even when repeated attempts were made to shield the areas surrounding the tumors during the radiotherapy sessions. We also attempted to irradiate tumors placed s.c. on the thighs of mice, but found that this resulted in significant morbidity when the tumors were relatively large, interfering with normal ambulation and causing problems with eating and drinking. The inability to deliver higher doses of external beam radiation without toxicity is a problem caused by the crude collimation of small animal irradiators and the small size of the mice, preventing proper protection of underlying organs. The toxicity was observed when radiation alone was administered and therefore could not be attributed to the effects of C. novyi-NT.

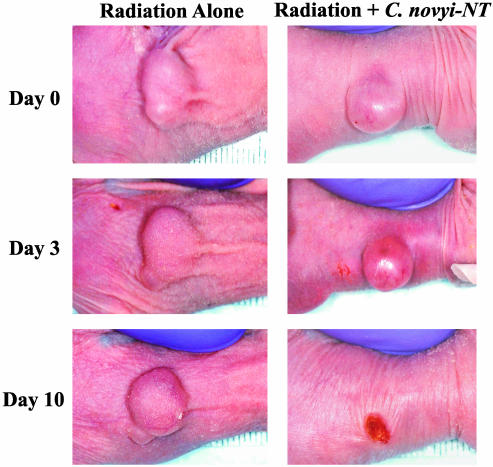

Fig. 6.

Kaplan–Meier plots of irradiated mice. (a and b) Mice treated with external beam radiation with or without C. novyi-NT spores. (c and d) Mice treated with brachytherapy with or without C. novyi-NT spores. The total doses each mouse received are indicated. The times to progression (first day that the tumor increased in size over the previous measurement) were recorded for each mouse. There were no regressions after tumor progression was recorded, and the tumors always increased in size thereafter. (a and c) HCT116 xenografts. (b and d) HuCC-T1 xenografts. Each group contained at least six mice. The differences between radiation alone and radiation plus C. novyi-NT were statistically significant in each case: a, P < 0.0001; b, P < 0.001; c, P < 0.05; and d, P < 0.05 (log-rank test).

We therefore turned to a brachytherapy approach in which higher doses of radiation could be administered in a more specific and less toxic fashion. To accomplish this in nude mice, we modified a clinical procedure used for the radiotherapy of uveal melanomas that uses plaques implanted with I-125 seeds. Iodine-125 was chosen because it produces low-energy photons (0.036 MeV) that can be designed to spare normal tissue, in contrast to the high-energy photons (0.663 MeV) produced by the Cs-137 irradiator that readily penetrate and induce organ damage. Computer simulations were generated to optimize uniformity of irradiation to the tumor bed while minimizing radiation to underlying internal organs (Fig. 7 a and b). Plaques were loaded with seeds in a pattern predicted to be optimal from the simulation, then taped onto the animals as shown in Fig. 7 c–f. This caused little discomfort to the mice and allowed delivery of at least 50 Gy to the tumor bed at a depth of 5 mm below the skin (the base of the tumor) without serious morbidity or death. In contrast, external beam irradiation applied to tumors in the same anatomical location resulted in death in five of five mice when only 15 Gy was administered.

Because treatment with C. novyi-NT spores frequently caused ulceration at the tumor site, mice were injected i.v. after removal of the plaques, which would have interfered with drainage from the ulcers. As shown in Fig. 6 c and d, this combination could eradicate tumors: six of six mice with HCT116 tumors and six of six mice with HuCC-T1 tumors were apparently cured (i.e., followed for at least 3 mo without evidence of disease). Brachytherapy alone, without spores, significantly delayed tumor progression but resulted in relatively few cures (Fig. 6 c and d).

Effects of C. novyi-NT When Given in Combination with RAIT. Although external beam irradiation and brachytherapy can be used to treat local disease, systemic administration of radioactively labeled biologicals is required to treat systemic disease. Such systemic radiotherapy is compromised not only by the oxygen dependence of radiation-induced cell death but also by the fact that radiolabeled compounds are not effectively delivered to poorly vascularized components of tumors (12). Because both these problems could potentially be overcome through the concurrent administration of anaerobic bacteria, we tested whether C. novyi-NT could enhance the effects of RAIT.

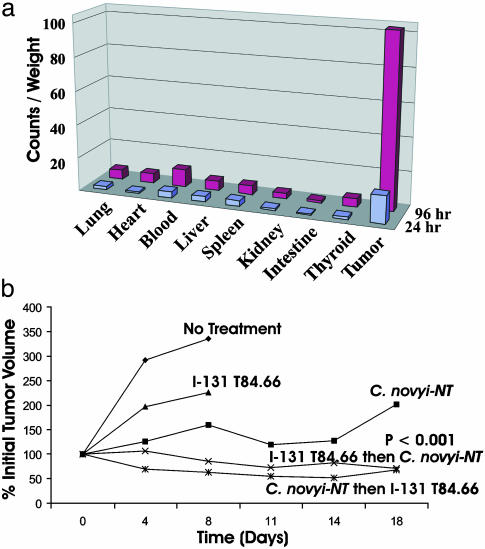

CEA is commonly expressed on the cell surface of colorectal and other cancers, and RAIT directed to CEA-expressing colorectal cancer metastases has been shown to be clinically useful (13). Previous studies have shown that xenografts of the colorectal cancer cell line LS174T can be treated with an I-131-labeled anti-CEA antibody (14). We confirmed these results in two ways. First, we found that an I-125-labeled anti-CEA antibody (T84.66) localized to tumors in vivo, with a tumor/blood ratio of >10:1 after 96 h (Fig. 8a). Second, we found that I-131-labeled T84.66, when administered alone, slowed tumor growth (Fig. 8b). These effects were considerably enhanced by treatment with C. novyi-NT spores (Fig. 8b). The combination therapy was effective whether the spores were administered before or after injection of the labeled antibody. In the experiment shown in Fig. 8b, two of 14 mice treated with both RAIT and spores were cured after a followup of 6 mo, whereas all mice treated with RAIT alone were euthanized after <2 mo due to excessive tumor growth.

Fig. 8.

RAIT in combination with C. novyi-NT in mice harboring LS174T xenografts. (a) Biodistribution of I-125-labeled T84.66 antibody in mice. Organs were harvested 24 or 96 h postinjection. Relative counts per minute (cpm) normalized to tissue weights were graphed. Each bar represents the average of four mice. The differences between tumor and blood at 24 and 96 h were statistically significant with P < 0.05 and P < 0.002, respectively (Student's t test). (b) Effect of C. novyi-NT plus I-131-labeled T84.66 antibody on LS174T. Spores were administered either 24 h before or 24 h after the labeled antibody. Each group contained at least six mice. Student's t test was performed by using the linear regression slope for each individual mouse. The difference between RAIT alone and RAIT plus C. novyi-NT arms was statistically significant at P < 0.001, as shown in b. The difference between C. novyi-NT alone and RAIT plus C. novyi-NT arms was significant at P < 0.05.

Discussion

Radiation therapy is one of the most broadly used therapies for cancer, acting on a wide array of tumor types (1). The results described above show that C. novyi-NT can significantly improve the results of radiotherapy in experimental settings. This improvement was observed with all forms of radiation treatment in common use. When used in combination with brachytherapy, a single dose of C. novyi-NT was able to cure 100% of mice bearing HCT116 and HuCC-T1 xenografts. Although fewer cures were observed when C. novyi-NT was combined with external beam radiation, the responses were impressive in light of the modest radiation dose (10 Gy) used in these experiments, five to 10× lower than the doses commonly used in clinical settings. Comparable responses were not observed when radiation was used alone (Figs. 3, 4, 5, 6). The data suggest that C. novyi-NT could enable therapy at sites in which more conventional doses of radiation are toxic, such as liver (15). Such an option is particularly important for cancers such as biliary adenocarcinomas (represented by HuCC-T1 in our study), for which few therapies other than radiation are available (16).

Likewise, the improved results obtained when C. novyi-NT was combined with RAIT (Fig. 8b) suggest this combination could allow patients to be treated with lower doses of radiolabeled antibodies, thereby minimizing toxicity to normal tissues such as the bone marrow. It is important to point out that C. novyi-NT is not a radiosensitizing agent in the classical sense. Radiosensitizing agents work by rendering individual neoplastic cells more sensitive to a given dose of radiation (1). In contrast, C. novyi-NT does not alter the intrinsic sensitivity of neoplastic cells to radiation and is more properly termed a radioenhancing agent. The mechanism through which these bacteria enhance the therapeutic effect is conceptually straightforward: C. novyi-NT targets those components of tumors that are least sensitive to radiation, because they are poorly oxygenated. Additionally, recent experiments have suggested that damage to microvascular endothelial cells is an important component of radiation effects (17). Such microvascular damage would increase the niche for C. novyi-NT growth by creating more hypoxic areas within tumors, thereby exacerbating bacteriolysis. Because the mechanisms through which radiation sensitizers and C. novyi-NT function are distinct, it is possible that radiation therapy could be further improved by combining C. novyi-NT with one of the several radiosensitizing agents now undergoing clinical or preclinical testing.

Another encouraging feature associated with the combination therapy studied here is that the efficacy was not a function of tumor volume. Tumor sensitivity to traditional radiation therapy is correlated to tumor sizes: large tumor volumes are associated with decreased tumor oxygen tension, providing a basis for radioresistance (4). This decrease in oxygen tension, however, allows for greater germination of C. novyi-NT. Accordingly, responses were observed in tumors of diverse sizes, with complete regressions and cures observed in tumors ranging from 50 to 1,000 mm3 in volume. Because C. novyi-NT was also effective when used in combination with radiation delivered at both a high dose rate (external beam, Fig. 3) and low dose rate (brachytherapy, Fig. 6), the data suggest that it could potentially be applied to a wide array of clinical settings. Furthermore, immunocompetent mice bearing B16 tumors responded to the combination of external beam radiation plus C. novyi-NT in a fashion similar to that of immunocompromised nude mice harboring xenografts, suggesting that immune status is not a primary determinant of efficacy.

In summary, we have shown that bacteriolytic therapy with C. novyi-NT, when combined with various forms of radiation therapy, can result in tumor regressions with relatively little toxicity in several of the mouse models tested. These results suggest that C. novyi-NT should be investigated further for its ability to potentiate the effects of standard radiation regimens and its potential for clinical use.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank L. Mezler and C. Lengauer for advice and assistance with photographic imaging and G. Parmigiani for expert statistical advice. This work was supported by the Miracle Foundation; the National Colorectal Cancer Research Alliance; the Clayton Fund; National Science Foundation Grant DBI 0099705; and National Institutes of Health Grants RR 000171, GM 07309, CA 062924, CA 43460, CA 62924, and CA 92871.

Abbreviations: CEA, carcinoembryonic antigen; RAIT, radioimmunotherapy; H&E, hematoxylin/eosin; Glut-1, glucose transporter 1.

References

- 1.Harrison, L. B., Chadha, M., Hill, R. J., Hu, K. & Shasha, D. (2002) Oncologist 7, 492-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chmura, S. J., Gupta, N., Advani, S. J., Kufe, D. W. & Weichselbaum, R. R. (2001) Semin. Radiat. Oncol. 11, 338-345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McGinn, C. J. & Lawrence, T. S. (2001) Semin. Radiat. Oncol. 11, 270-280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wachsberger, P., Burd, R. & Dicker, A. P. (2003) Clin. Cancer Res. 9, 1957-1971. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Teicher, B. A. (1995) Hematol. Oncol. Clin. N. Am. 9, 475-506. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hockel, M., Schlenger, K., Aral, B., Mitze, M., Schaffer, U. & Vaupel, P. (1996) Cancer Res. 56, 4509-4515. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Duenas-Gonzalez, A., Cetina, L., Mariscal, I. & de la Garza, J. (2003) Cancer Treat. Rev. 20, 1-11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jain, R. K. & Forbes, N. S. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 14748-14750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dang, L. H., Bettegowda, C., Huso, D. L., Kinzler, K. W. & Vogelstein, B. (2001) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 98, 15155-15160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Miyagiwa, M., Ichida, T., Tokiwa, T., Sato, J. & Sasaki, H. (1989) In Vitro Cell Dev. Biol. 25, 503-510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Airley, R., Loncaster, J., Davidson, S., Bromley, M., Roberts, S., Patterson, A., Hunter, R., Stratford, I. & West, C. (2001) Clin. Cancer Res. 7, 928-934. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Carter, P. (2001) Nat. Rev. Cancer 1, 118-129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Behr, T. M., Liersch, T., Greiner-Bechert, L., Griesinger, F., Behe, M., Markus, P. M., Gratz, S., Angerstein, C., Brittinger, G., Becker, H., et al. (2002) Cancer 94, 1373-1381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Modrak, D. E., Gold, D. V., Goldenberg, D. M. & Blumenthal, R. D. (2003) Tumour Biol. 24, 32-39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Malik, U. & Mohiuddin, M. (2002) Semin. Oncol. 29, 196-201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Crane, C. H., Macdonald, K. O., Vauthey, J. N., Yehuda, P., Brown, T., Curley, S., Wong, A., Delclos, M., Charnsangavej, C. & Janjan, N. A. (2002) Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 53, 969-974. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garcia-Barros, M., Paris, F., Cordon-Cardo, C., Lyden, D., Rafii, S., Haimovitz-Friedman, A., Fuks, Z. & Kolesnick, R. (2003) Science 300, 1155-1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.