Abstract

It is often difficult to evaluate the grade of malignancy and choose an appropriate treatment for colorectal carcinoids in clinical settings. Although tumor size and depth of invasion are evidently not enough to stratify the risk of this rare tumor, the present guidelines or staging systems do not mention other clinicopathological variables. Recent studies, however, have shed light on the impact of lymphovascular invasion on the outcome of colorectal carcinoids. It has been revealed that the presence of lymphovascular invasion was among the strongest risk factors for metastasis along with tumor size and depth of invasion. Furthermore, tumors smaller than 1 cm, within submucosal invasion and without lymphovascular invasion, carry minimal risk for metastasis with 100% 5-year survival in the studies from Japan as well as from the USA. This would suggest that these tumors could be curatively treated by endoscopic resection or transanal local excision. On the other hand, colorectal carcinoids with either lymphovascular invasion or tumor size larger than 1 cm carry the risk for metastasis equivalent to adenocarcinomas. Therefore, it should be emphasized that histological examination of lymphovascular invasion is mandatory in the specimens obtained by endoscopic resection or transanal local excision, as this would provide useful information for determining the need for additional radical surgery with regional lymph node dissection. Although the present guidelines or TNM staging system do not mention the impact of lymphovascular invasion, this would be among the next promising targets in order to establish better guidelines and staging systems, particularly in early-stage colorectal carcinoids.

Keywords: Lymphovascular invasion, Neuroendocrine tumor, Carcinoid, Colorectal cancer

ISSUES IN GRADING THE MALIGNANCY OF COLORECTAL CARCIOIDS

Carcinoid is synonymous with the term “well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumor” in the gastrointestinal tract (GI)[1,2]. According to the classification of the World Health Organization (WHO), carcinoids of the colon and rectum are grouped together and are distinguished from those of the appendix or ileum[3].

The biological behavior of colorectal carcinoids differs among tumors[1,2,4-9]. The WHO classification defines colorectal carcinoids as benign if they are confined within submucosa, measure no larger than 20 mm and are without angioinvasion[1,3]. However, there have been many reports critical of this definition. Soga[10] examined 777 cases of rectal carcinoids with submucosal invasion, and found that metastatic rates of the tumors not larger than 5 mm and 5.1-10 mm were 3.7% and 13.2%, respectively. Heah et al[11] and Seow-Cheoen et al[12] reported that even a 1-mm rectal carcinoid caused regional lymph node metastasis. In light of oncogenic development of carcinoids, intraglandular hyperplastic proliferation of argyrophil cells in the mucosal layer develops extraglandular budding and then invades to penetrate the muscularis mucosae, forming precursors of carcinoids (microcarcinoids) in the submucosal layer[13,14]. Accordingly, GI carcinoids with submucosal invasion should be malignant if there is a submucosal invasion from a mucosal lesion.

Thus, it is often difficult to evaluate the grade of malignancy and choose appropriate treatment for this rare tumor in clinical settings. Numerous studies have reported various factors influencing survival and prognosis of colorectal carcinoids, including tumor size larger than 10 or 20 mm, invasion to the muscularis propria, older age, male gender, tumor site, histologic growth pattern and DNA ploidy[2,5,15-23].

Among them, recent articles, including our study in 2007, have shed light on the importance of lymphovascular invasion in colorectal carcinoids[6,15]. Although the prognostic importance of lymphovascular invasion has been well established in colorectal carcinomas, it has been scarcely investigated in a large series of colorectal carcinoids. This review highlights on the recent advance in grading the malignancy of colorectal carcinoids, particularly focusing on the importance of lymphovascular invasion.

GUIDELINES AND TNM STAGING IN COLORECTAL CARCINOIDS

Tumor size is the most important indicator of metastasis in colorectal carcinoids[2,19]. It is generally accepted that tumors greater than 20 mm need radical resection for possible lymph node metastasis[2,12,19,22]. On the other hand, the management of those smaller than 20 mm has been controversial. Recent guidelines from UKNET work for neuroendocrine tumours suggested that colorectal carcinoids smaller than 1 cm may be considered adequately treated by complete endoscopic removal[19]. However, there has been opposition to these guidelines based on the fact that lymph node metastasis is found even in tumors smaller than 10 mm[10-12,18]. In 2006, the Consensus Conference on the European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Neuroendocrine Gastrointestinal Tumors, Part 2: Midgut and Hindgut Tumors was held in Francati (Rome Italy), and TNM staging and grading was proposed for colorectal carcinoids, based on this conference[20]. In this staging system, the T factor consists of tumor size and tumor depth. Tumors within submucosa and less than 1cm and 1-2 cm are defined as T1a and T1b, respectively, and those invading muscularis propria or size > 2 cm are defined as T2 (Table 1). Furthermore, this article proposed a grading system determined by mitotic count or Ki-67 index (Table 2). In this grading system, tumors are classified into G1, G2 and G3 according to the activity of mitosis. G3 indicates a poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinoma with high mitotic activity, so carcinoids (namely, well differentiated neuroendocrine tumors) are grouped as G1 or G2. Other studies have also confirmed the usefulness of the grading system by mitotic activity[15,16,23,24].

Table 1.

TNM classification for endocrine tumors of colon and rectum[20]

| TNM | |

| T-primary tumor1 | |

| TX | Primary tumor cannot be assessed |

| T0 | No evidence of primary tumor |

| T1 | Tumor invades mucosa or submucosa |

| T1a size < 1 cm | |

| T1b size 1-2 cm | |

| T2 | Tumor invades muscularis propria or size > 2 cm |

| T3 | Tumor invades subserosa/pericolic/perirectal fat |

| T4 | Tumor directly invades other organs/structures and/or perforates visceral peritoneum |

| N-regional lymph nodes | |

| NX | Regional lymph node status cannot be assessed |

| N0 | No regional lymph node metastasis |

| N1 | Regional lymph node metastasis |

| M-distant metastases | |

| MX | Distant metastasis cannot be assessed |

| M0 | No distant metastases |

| M1 | Distant metastasis |

1For any T add (m) for multiple tumors.

Table 2.

Grading proposal for neuroendocrine tumors of colon and rectum[20]

| Grade | Mitotic count (10HPF)1 | Ki-67 index (%)2 |

| G1 | < 2 | ≤ 2 |

| G2 | 2-20 | 3-20 |

| G3 | > 20 | > 20 |

110 HPF (High Power Field) = 2 mm2, at least 40 fields (at 40 × magnification) evaluated in areas of highest mitotic density; 2MIB1 antibody; % of 2000 tumor cells in areas of highest nuclear labeling.

IMPACT OF LYMPHOVASCULAR INVASION IN COLORECTAL CARCINOIDS

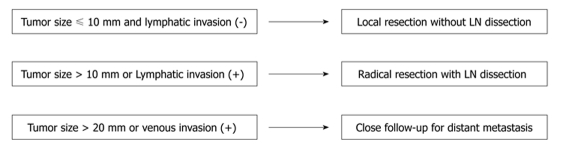

The impact of lymphovascular invasion on oncological outcomes has been scarcely investigated in colorectal carcinoids. However, recent studies have elucidated the importance of lymphovascular invasion. Konishi et al[6] have analyzed 247 colorectal carcinoids undergoing surgery among a total of 90 057 colorectal cancers registered in the Japanese nationwide registry between 1984 to 1998. Multivariate analysis revealed that lymphatic invasion and tumor size over 10 mm were the two independent predictive factors for lymph node metastasis, while venous invasion and tumor size over 20 mm were the two independent predictive factors for distant metastasis. The present data indicated that lymphovascular invasion was more predictive of metastasis than the other evaluated variables in multivariate analysis, such as age, gender and muscular invasion. Furthermore, tumors without either of the two identified risk factors had no lymph node or distant metastasis, and this patient group had a 100% 5-year disease specific survival. Accordingly, Konishi et al[6] proposed a treatment strategy as follows (Figure 1): Tumors not larger than 10 mm and without lymphatic invasion carry no risk for lymph node metastasis, and could be curatively treated by endoscopic resection or transanal local excision. Importantly, the resected specimen should undergo pathological assessment for lymphovascular invasion. If the tumors are larger than 10 mm or diagnosed as having lymphatic invasion, radical surgery should be considered for dissection of regional lymph nodes. Furthermore, tumors larger than 20 mm or with venous invasion carry a high risk for distant metastasis, and need close follow-up. Risk stratification with these risk factors could be simple and useful in determining the therapeutic approach for this rare tumors.

Figure 1.

Treatment strategy of colorectal carcinoids[7].

Another important finding in the present study was that the metastatic potential of colorectal carcinoids was not lower than well- and moderately-differentiated adenocarcinomas registered in the same period, if the tumors had either of the two identified risk factors for metastasis. Furthermore, colorectal carcinoids carry even higher risk for metastasis than adenocarcinomas if the tumors had both of the two risk factors. Our data was compatible with Soga’s report, in which the metastatic rates of early-stage rectal carcinoids were higher than carcinomas if the tumors were larger than 10 mm[10].

Fahy et al[15,16] also emphasized the impact of lymphovascular invasion in rectal carcinoids. The authors investigated the association between various clinicopathological variables and poor oncological outcomes in 70 rectal carcinoids that underwent surgical resection in a single institution. Their analysis revealed that the presence of lymphovascular invasion was strongly associated with metastasis, poor relapse free survival and disease specific survival. According to the results of their analysis, the authors proposed a novel scoring system called “carcinoid of the rectum risk stratification” (Table 3). In this simple scoring system, the total risk score was calculated by adding points assigned to the four variables identified as important in determining the behavior of rectal carcinoids: size, depth of invasion, lymphovascular invasion and mitotic rate. The risk was stratified into low, intermediate and high risk according to the total score. Survival analysis revealed that patients with low risk score exhibited a significantly higher 5-year relapse free survival than patients with either intermediate or high risk scores. Importantly, their results showed that patients in the low risk group, which was defined as tumor size smaller than 1cm, depth of invasion within submucosa, no lymphovascular invasion and less than 2/50 HPF mitotic rates, had essentially no risk of recurrence and a 100% 5-year disease specific survival. This result was completely compatible with the study by Konishi et al[6] which also reported a 100% 5-year disease specific survival in the risk-free group. Regarding the methods for evaluation of lymphovascular invasion, there is no definite evidence at this point to conclude whether immunohistochemistry is better than HE stain to predict metastasis or prognosis in colorectal carcinoids. Future standardization is needed in the guidelines for better understanding of this rare disease.

Table 3.

| Points | Size (cm) | Depth | Lymphovascular invasion | Mitotic rate (HPF) |

| 0 | < 1 | Mucosa/submucosa | No | < 2/50 |

| 1 | 1–1.9 | Muscularis or deeper | Yes | ≥ 2/50 |

| 2 | ≥ 2 |

CaRRS is obtained by adding points associated with each clinicopathological feature; Low risk: 0 points; Intermediate risk: 1-2 points; High risk: ≥ 3 points.

Thus, the absense of lymphovascular invasion should be the key for confirming a good outcome of colorectal carcinoids. It should again be emphasized that histological examination of lymphovascular invasion is mandatory in the specimens obtained by endoscopic resection or transanal local excision, as this would provide useful information for determining the need for additional radical surgery with regional lymph node dissection. Although the size and depth of invasion are evidently not enough to stratify the risk of this rare tumor, the present guidelines or TNM staging system do not mention the impact of lymphovascular invasion. Lymphovascular invasion would be among the next promising targets to consider in order to establish better guidelines or staging systems, particularly in early-stage colorectal carcinoids.

Footnotes

Peer reviewer: Akira Tsunoda, MD, PhD, Professor, Department of Surgery, Kameda Medical Center, 929 Higashi-cho, Kamogawa City, Chiba 296-8602, Japan

S- Editor Li LF L- Editor Lutze M E- Editor Yang C

References

- 1.Klöppel G, Perren A, Heitz PU. The gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine cell system and its tumors: the WHO classification. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2004;1014:13–27. doi: 10.1196/annals.1294.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Modlin IM, Kidd M, Latich I, Zikusoka MN, Shapiro MD. Current status of gastrointestinal carcinoids. Gastroenterology. 2005;128:1717–1751. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.03.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Solcia E, Capella C, Kloppel G, Heitz PU, Sobin LH, Rosai J. Histologic typing of endocrine tumours. WHO international histological classification of tumours. 2nd edn. Berlin: Springer; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hemminki K, Li X. Incidence trends and risk factors of carcinoid tumors: a nationwide epidemiologic study from Sweden. Cancer. 2001;92:2204–2210. doi: 10.1002/1097-0142(20011015)92:8<2204::aid-cncr1564>3.0.co;2-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Klöppel G, Anlauf M. Epidemiology, tumour biology and histopathological classification of neuroendocrine tumours of the gastrointestinal tract. Best Pract Res Clin Gastroenterol. 2005;19:507–517. doi: 10.1016/j.bpg.2005.02.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Konishi T, Watanabe T, Kishimoto J, Kotake K, Muto T, Nagawa H. Prognosis and risk factors of metastasis in colorectal carcinoids: results of a nationwide registry over 15 years. Gut. 2007;56:863–868. doi: 10.1136/gut.2006.109157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Konishi T, Watanabe T, Muto T, Kotake K, Nagawa H. Site distribution of gastrointestinal carcinoids differs between races. Gut. 2006;55:1051–1052. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Maggard MA, O'Connell JB, Ko CY. Updated population-based review of carcinoid tumors. Ann Surg. 2004;240:117–122. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000129342.67174.67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Modlin IM, Lye KD, Kidd M. A 5-decade analysis of 13,715 carcinoid tumors. Cancer. 2003;97:934–959. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Soga J. Early-stage carcinoids of the gastrointestinal tract: an analysis of 1914 reported cases. Cancer. 2005;103:1587–1595. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20939. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Heah SM, Eu KW, Ooi BS, Ho YH, Seow-Choen F. Tumor size is irrelevant in predicting malignant potential of carcinoid tumors of the rectum. Tech Coloproctol. 2001;5:73–77. doi: 10.1007/s101510170002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seow-Cheoen F, Ho J. Tiny carcinoids may be malignant. Dis Colon Rectum. 1993;36:309–310. doi: 10.1007/BF02053521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Soga J. Carcinoids and their variant endocrinomas. An analysis of 11842 reported cases. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2003;22:517–530. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Soga J. Endocrinocarcinomas (carcinoids and their variants) of the duodenum. An evaluation of 927 cases. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2003;22:349–363. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fahy BN, Tang LH, Klimstra D, Wong WD, Guillem JG, Paty PB, Temple LK, Shia J, Weiser MR. Carcinoid of the rectum risk stratification (CaRRS): a strategy for preoperative outcome assessment. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:396–404. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9197-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fahy BN, Tang LH, Klimstra D, Wong WD, Guillem JG, Paty PB, Temple LK, Shia J, Weiser MR. Carcinoid of the rectum risk stratification (CaRRs): a strategy for preoperative outcome assessment. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:1735–1743. doi: 10.1245/s10434-006-9311-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McGory ML, Maggard MA, Kang H, O'Connell JB, Ko CY. Malignancies of the appendix: beyond case series reports. Dis Colon Rectum. 2005;48:2264–2271. doi: 10.1007/s10350-005-0196-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Naunheim KS, Zeitels J, Kaplan EL, Sugimoto J, Shen KL, Lee CH, Straus FH 2nd. Rectal carcinoid tumors--treatment and prognosis. Surgery. 1983;94:670–676. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramage JK, Davies AH, Ardill J, Bax N, Caplin M, Grossman A, Hawkins R, McNicol AM, Reed N, Sutton R, et al. Guidelines for the management of gastroenteropancreatic neuroendocrine (including carcinoid) tumours. Gut. 2005;54 Suppl 4:iv1–i16. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.053314. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Rindi G, Klöppel G, Couvelard A, Komminoth P, Körner M, Lopes JM, McNicol AM, Nilsson O, Perren A, Scarpa A, et al. TNM staging of midgut and hindgut (neuro) endocrine tumors: a consensus proposal including a grading system. Virchows Arch. 2007;451:757–762. doi: 10.1007/s00428-007-0452-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rossi G, Valli R, Bertolini F, Sighinolfi P, Losi L, Cavazza A, Rivasi F, Luppi G. Does mesoappendix infiltration predict a worse prognosis in incidental neuroendocrine tumors of the appendix? A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study of 15 cases. Am J Clin Pathol. 2003;120:706–711. doi: 10.1309/199V-D990-LVHP-TQUM. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shebani KO, Souba WW, Finkelstein DM, Stark PC, Elgadi KM, Tanabe KK, Ott MJ. Prognosis and survival in patients with gastrointestinal tract carcinoid tumors. Ann Surg. 1999;229:815–821; discussion 822-823. doi: 10.1097/00000658-199906000-00008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tomassetti P, Campana D, Piscitelli L, Casadei R, Nori F, Brocchi E, Santini D, Pezzilli R, Corinaldesi R. Endocrine tumors of the ileum: factors correlated with survival. Neuroendocrinology. 2006;83:380–386. doi: 10.1159/000096053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Eeden S, Quaedvlieg PF, Taal BG, Offerhaus GJ, Lamers CB, Van Velthuysen ML. Classification of low-grade neuroendocrine tumors of midgut and unknown origin. Hum Pathol. 2002;33:1126–1132. doi: 10.1053/hupa.2002.129204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]