Abstract

Biliary tract cancers (BTC) are relatively rare tumors, and the prognosis is extremely poor. There has been no standard chemotherapy for advanced BTC. However, recently, gemcitabine (GEM) have been used against BTC as the most active agent, and promising response rates and overall survival times with tolerable drug toxicities have been observed. In this article, two cases of advanced intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma and unresectable metastatic gallbladder (GB) cancer are reported. They were treated with hepatic arterial infusion (HAI) chemotherapy using a combination of GEM and cisplatin, along with the systemic administration of GEM. As a consequence, multiple liver tumors, the GB cancer and metastatic lymph nodes regressed without severe drug toxicities, and favorable results (the overall survival times were 16 and 14 mo, respectively) were achieved. In conclusion, HAI therapy using GEM combined with cisplatin may be a useful and well-tolerated option for advanced BTC, especially in cases where multiple liver metastases are detected.

Keywords: Hepatic arterial infusion, Gemcitabine, Cisplatin, Intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma, Gallbladder cancer

INTRODUCTION

Biliary tract cancers (BTC) are relatively rare tumors, and their prognosis is extremely poor. The median survival period of gallbladder (GB) cancer is 6 mo, and cholangiocarcinoma (CC) also has an unfavorable prognosis, with a median survival time of 3-9 mo. In particular, intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma (ICC) generally presents at a more advanced stage than extrahepatic CC. Therefore, its prognosis is even worse. In the past, the efficacy of conventional systemic chemotherapy in advanced, unresectable BTC was negligible. However, after the use of gemcitabine (GEM), a novel nucleoside analog, encouraging results for tumor control rates and survival time have been recently reported for BTC[1-4]. Furthermore, a chemotherapeutic regimen using GEM combined with cisplatin has been demonstrated to be superior to GEM alone and/or a combination of fluoropyrimidines and cisplatin[5-9]. Chemotherapy using hepatic arterial infusion (HAI) is a promising option for advanced and multiple hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) and unresectable metastatic liver tumors of various origins, and this therapeutic modality has resulted in superior tumor control rates compared to systemic chemotherapy[10-13]. However, there have been few reports on HAI therapy using GEM together with cisplatin for advanced BTC.

In this article, two cases of advanced ICC and unresectable GB cancer are reported, which showed favorable outcomes when treated with HAI therapy using a combination of GEM and cisplatin.

CASE REPORT

Case 1

A 71-year-old man was admitted to our hospital with multiple hepatic tumors. A palpable liver was found in the right upper abdominal quadrant during physical examination, whereas no other relevant pathological findings were evident. The laboratory findings showed liver dysfunction. Among the serum tumor markers, α-fetoprotein (AFP) and carbohydrate antigen (CA) 19-9 were elevated (124.3 ng/mL, normal < 10; and 62 U/mL, normal < 37, respectively), but the level of carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) was normal. Contrast- enhanced (CE) computed tomography (CT) of the abdomen revealed a huge liver tumor measuring 11 cm in diameter in the medial segment, and multiple small-sized tumors mainly located in the anterior and medial segment of the liver, which presented with ring enhancement in the arterial phase and central necrosis (Figure 1A and B). Multiple swollen lymph nodes (LNs) were noted in liver hilus and para- aorta, accompanied by ascites. No other tumors presented as primary foci in any other tissue outside the liver. Biopsied specimens from one of the hepatic tumors revealed a moderately-differentiated adenocarcinoma with widespread necrosis, which was not accompanied by hepatic cell components (Figure 2A). Additional histological examinations disclosed positive immunostaining for cytokeratin 7, and immuno-positive AFP in the adenocarcinoma cells (Figure 2B and C), suggesting that the hepatic tumors were AFP-producing cholangiocellular carcinomas. Under the diagnosis that the current case was an ICC of UICC TMN stage III C with an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS) of 0, intensive chemotherapy was implemented, using both HAI and intravenous (i.v.) administration. Following informed consent was given concerning the side effects of the therapy including interventional procedures and chemotherapeutic agents, 600 mg/m2 of GEM on d 1 and 8, and 10 mg/body of cisplatin on d 1 to 3 and 8 to 10 were infused via a subcutaneously implanted port which was connected to a catheter placed in the proper hepatic artery. Concurrently, 400 mg/m2 of GEM was administered intravenously on d 1 and 8, every 3 wk. The patient received 9 cycles of chemotherapy for 26 wk. Following completion of 2 cycles of chemotherapy, the huge tumor in the medial segment showed a reduction in diameter, and the ascitic fluid disappeared completely. However, an abnormal uptake on FDG-PET CT was observed in the hepatic tumors in both lobes, as well as the LNs in the liver hilus and para-aorta (Figure 3). After completion of 7 cycles of chemotherapy, almost all of the hepatic tumors had shrunk in size, and the swollen LNs were almost absent upon a CE-CT of the abdomen (Figure 4A). Meanwhile, a PET-CT revealed abnormal uptake only in the tumors in the medial segment, and no uptake in tumors in the right lobe and LNs (Figure 4B), suggesting that the tumor response was a partial response (PR), according to the Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) criteria. The elevated serum levels of CA19-9 and AFP were also decreased to almost the normal range after 8 cycles of chemotherapy (Figure 5). Following 9 cycles of chemotherapy, hematological toxicities such as severe thrombocytopenia (NCI-CTC, grade 3) and leukopenia (grade 2) were observed. Therefore, a modified chemotherapeutic regimen (80% of the initial dose of GEM on d 1, and 10 mg cisplatin on d 1 and 2) was carried out biweekly thereafter. Although a greater reduction of the abnormal uptake from the tumor in the medial segment was revealed on the PET-CT after the end of 11 cycles of chemotherapy, new abnormal uptake was found in the LN in the liver hilus. Therefore, the present case was diagnosed as a progressive disease (PD). A new chemotherapy regimen using GEM (480 mg/m2 for HAI and 320 mg/m2 for i.v. administration on d 2) and oral S-1 (80 mg/body for 7 to 14 d, consecutively) every 3 wk was started. Following the end of 4 cycles of the new regimen, the liver tumors and metastatic LNs became larger. An ECF regimen using epirubicin 40 mg/m2 and cisplatin 48 mg/m2 for HAI on d 1, and 5-FU 160 mg/m2 for i.v. administration for 4 consecutive days, was then carried out every 3 wk. However, systemic metastases (peritoneum, bone and lung) and massive ascites were soon observed. At 16 mo after the diagnosis, the patient died of multiple organ failure.

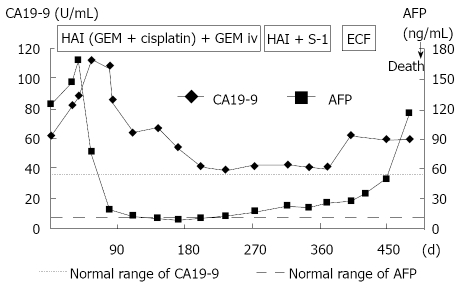

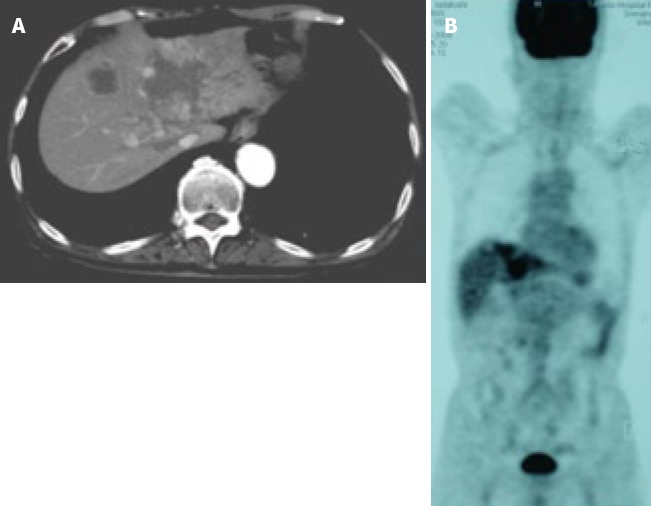

Figure 1.

Contrast-enhanced (CE) computed tomography of the abdomen revealed a huge tumor, measuring 11 cm in diameter, which presented with ring enhancement in the arterial phase and central necrosis. A: In the medial segment; B: Multiple small-sized tumors mainly located in the anterior and medial segments of the liver.

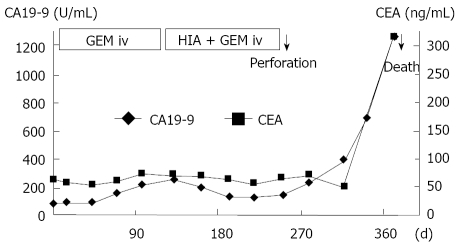

Figure 2.

Biopsied specimens from one of the hepatic tumors. A: A moderately-differentiated adenocarcinoma with wide-spread necrosis, which were not accompanied by hepatic cell components (HE × 200); B: Positive immunostaining for cytokeratin 7 (× 200) in the adenocarcinoma cells; C: Immuno-positive AFP (× 200) in the adenocarcinoma cells.

Figure 3.

FDG-PET CT after the end of 2 cycles of chemotherapy revealed abnormal uptake in the hepatic tumors in both lobes and the LNs in the liver hilus and para-aorta.

Figure 4.

Images after the end of 7 cycles of chemotherapy. A: CE-CT showed a reduction in the size of a huge tumor seen in the medial segment; B: PET-CT revealed abnormal uptake only in the tumors in the medial segment, and no uptake was observed in tumors from the right lobe and the LNs in the liver hilus and para-aorta.

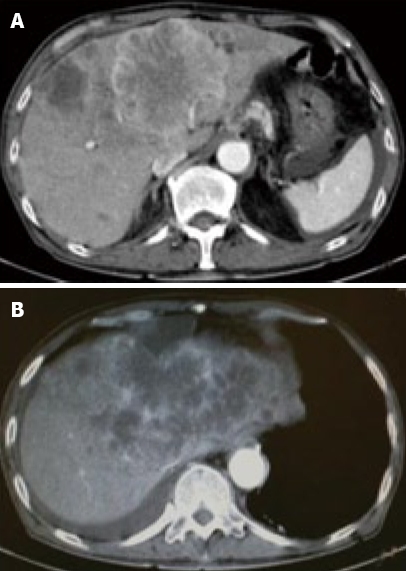

Figure 5.

Clinical course and changes in the serum levels of CA19-9 and AFP.

Case 2

An 83-year-old woman presented to our hospital with abdominal discomfort and appetite loss. Physical examination revealed a swollen gallbladder but no other pathological findings. The laboratory data demonstrated liver dysfunction and an elevation in the serum levels of CA 19-9 and CEA (82.0 U/mL, normal < 37; 61.3 ng/mL, normal < 5, respectively). Ultrasonography and CE-CT of the abdomen revealed gall stones and a GB tumor, which invaded the adjacent liver directly. Multiple liver tumors and swollen LNs in the liver hilus were also observed. The patient’s PS was 1 and, based on the diagnosis that the current case was an advanced GB carcinoma (UICC TNM stage IV), chemotherapy using a 4 wk cycle of i.v. administration of 1000 mg/m2 of GEM on d 1, 8, 15 was started. After completion of 4 cycles of chemotherapy, the tumor increased in size in the GB, liver and LNs in the liver hilus (Figure 6A and B), and ascitic fluid appeared on CE-CT (RECIST, PD). The serum levels of CA 19-9 and CEA elevated gradually (Figure 7). Furthermore, metastasis in the lumbar vertebra was detected. Immediately thereafter, radiation therapy to the lumbar vertebrae was started. After informed consent was given, a heparin-coated catheter was placed in the common hepatic artery to supply all of the tumor vessels, including the GB and liver. Thereafter, the catheter was connected to the injection port. The gastroduodenal artery was occluded by steel coils to prevent gastroduodenal injury from anticancer drugs. Next, a new chemotherapeutic regimen comprising HAI (600 mg/m2 of GEM on d 1 and 8, and 10 mg/body of cisplatin on d 1 to 3 and 8 to 10) and the i.v. administration of GEM (400 mg/m2, d 1 and 8), was carried out every 3 wk for 3 cycles. After hematological toxicity (grade 2) occurred at the end of 3 cycles of chemotherapy, a modified regimen in which cisplatin administration was shortened to 2 d was instigated for 2 cycles. At the end of 3 cycles of chemotherapy with HAI, the tumors in the GB and liver decreased in size (Figure 8A and B), and the swollen LNs in the liver hilus regressed on the abdominal CT (RECIST, PR). However, following the 2 cycles of modified HAI chemotherapy, a perforation in the duodenum which was invaded directly by the GB cancer occurred. The chemotherapy was then discontinued, and 14 mo after the initial diagnosis, the patient was died of multiple organ failure.

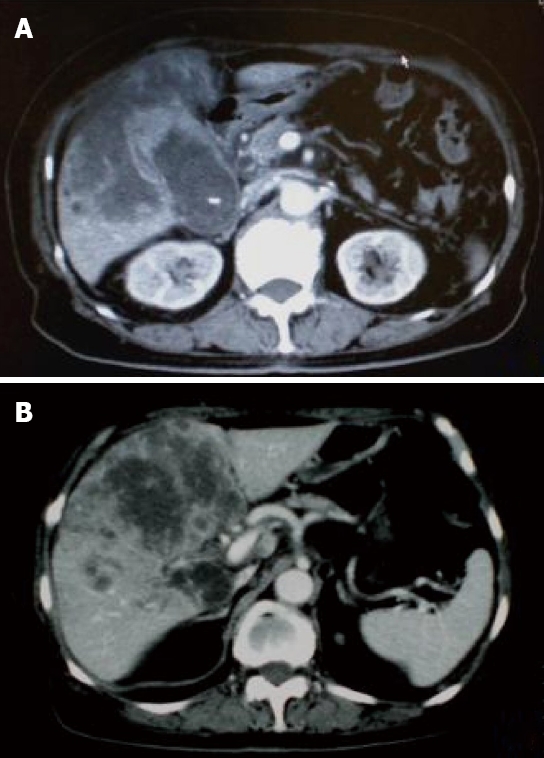

Figure 6.

CE-CT after the end of 4 cycles of i.v. administration chemotherapy showed that the tumor increased in size. A: The GB tumor; B: Liver tumor.

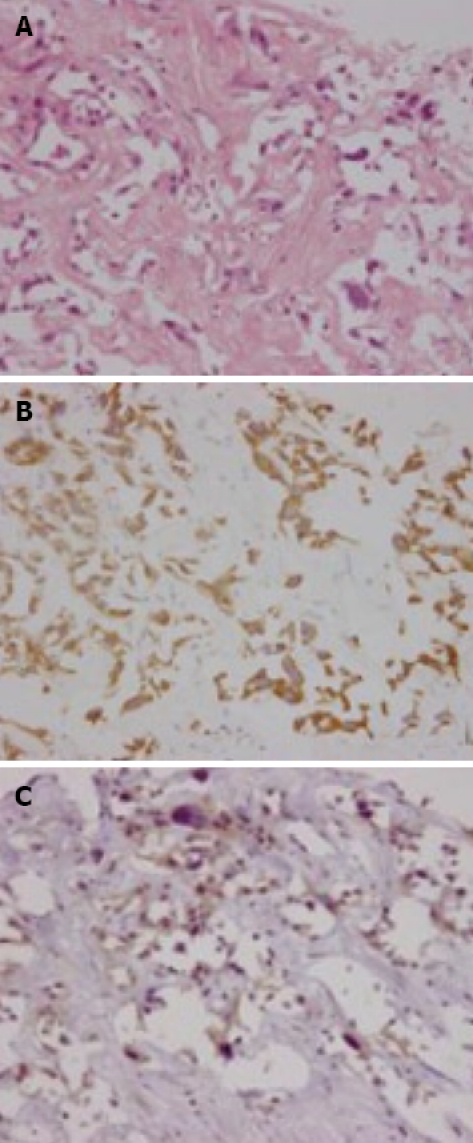

Figure 7.

Clinical course and changes in the serum levels of CA19-9 and CEA.

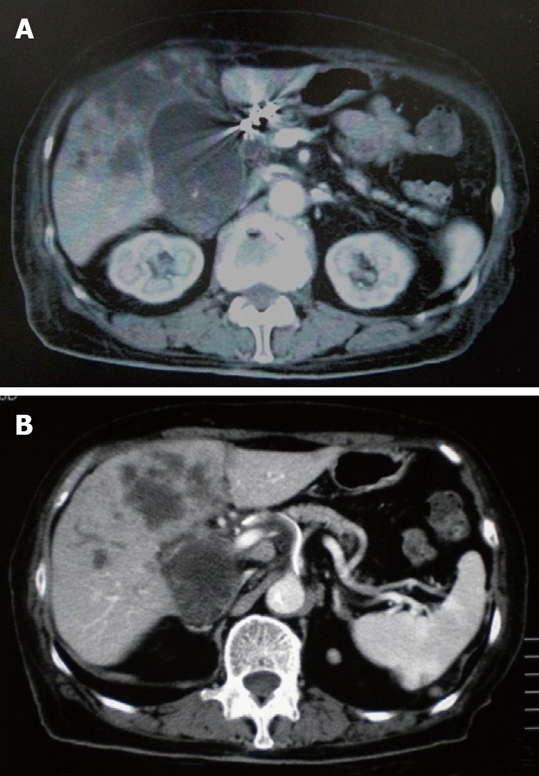

Figure 8.

CE-CT after the end of 3 cycles of HAI chemotherapy showed a decrease in the size of tumor. A: The GB tumor; B: Liver tumor.

DISCUSSION

In the past, there was no standard chemotherapy for advanced BTC i.e. GB cancer and CC. However, GEM has recently been used against BTC as the most active agent, and promising response rates and overall survival times with tolerable drug toxicities were demonstrated[1-4]. GEM has a synergistic and cytotoxic effect in vivo and in vitro, in combination with cisplatin[14,15] and capecitabine[16]. More recently, the superiority of combination chemotherapy using GEM plus cisplatin, as well as the combination of GEM with capecitabine or oxaliplatin, has been demonstrated among the GEM-only, GEM-based and 5-FU-based chemotherapeutic regimens for BTC[4,5,8,9,17-19]. The intra-arterial (i.a.) administration of GEM was used for the treatment of advanced pancreatic carcinoma by Shamseddine et. al. in 2005[20]. They reported that GEM in i.a. administration could be safely escalated to 1400 mg/m2 within a tolerable toxicity. On the other hand, in low dose FP (5-FU and cisplatin) therapy for advanced and multiple HCCs, cisplatin is administered intra-arterially at a dose of 10 mg/body for 5 consecutive days[13]. Based on the previous reports mentioned above and our judgment that the control of multiple liver tumors might decide the patient’s survival time, HAI therapy using GEM combined with cisplatin was performed. Following consideration of treatment efficacy against distant metastases (LNs and bone), the systemic administration of GEM was used together with HAI in both cases. In case 1, after the end of 7 cycles of chemotherapy, the liver tumors had regressed, and the swollen LNs and ascitic fluid disappeared completely. In case 2, because of the PD after 4 cycles of the i.v. administration of GEM, HAI therapy was started again, and consequently favorable tumor responses were achieved. The survival times of the current two cases were also similar.

A chemotherapeutic regimen using the i.a. administration of GEM together with hepatic embolization has been performed against advanced BTC, and respectable results were achieved[21,22]; the survival time for the group treated by GEM with microspheres was 20.2 mo, whereas that of the TACE group using a combination of GEM plus cisplatin was 13.8 mo. Arterial administration can deliver anti-cancer agents at high concentrations into liver tumors, and has a longer lasting cytotoxic effect. A previous report demonstrated that the peak plasma concentration of GEM after i.a. administration was reduced to ~1/7th of that observed using the systemic i.v. route, and that no grade 3 or 4 toxicity was documented after i.a. administration of up to 1400 mg/m2 of GEM[20]. Vogl et al[21] noted that the use of GEM doses (~1800 mg/m2) higher than the recommended 1000 mg/m2 was well tolerated if microspheres were used. Moreover, Gusani et al[22] showed that the median survival in unresectable CC treated with GEM-based TACE was not significantly different in patients with liver disease only, as compared to those with extra-hepatic disease. In 2008, HAI therapy using a combination of GEM and mitomycin against advanced CC revealed a poor tumor control rate, as compared to that against metastatic breast cancer and colorectal carcinoma[12]. Therefore, HAI therapy using GEM combined with cisplatin may be a useful and well- tolerated option for advanced BTC, especially in which multiple liver metastases are detected.

In recent years, targeted therapy has been carried out for advanced BTC as a second-line chemotherapy[23] and in phase II trials[24]. Chemotherapeutic regimens using cetuximab or bevacizumab combined with GEM and oxaliplatin have also been used against advanced BTC and, at present, passable tumor- responses have been achieved[23,24]. In conclusion, HAI therapy with GEM plus cisplatin might be an effective and well-tolerated option in advanced BTC, and in the future we recommend that clinical trials of HAI therapy using GEM-based platinum or capecitabine, with or without targeted agents, should be performed for advanced BTC.

Footnotes

Peer reviewers: Hiroshi Yoshida, MD, PhD, Department of Surgery, Nippon Medical School, 1-1-5 Sendagi, Bunkyo-ku, Tokyo, 113-8603, Japan; Ruben Ciria, PhD, Uniersity Hospital Reina Sofia, Departmento De Cirugia Hepatobiliar Y Trasplante HEPÁTICO (Department of Hepatobiliary Surgery and Liver Transplantation), Avennida Menendez PidalI s/n, Cordoba 14004, Spain

S- Editor Zhang HN L- Editor Hughes D E- Editor Liu N

References

- 1.Knox JJ, Hedley D, Oza A, Siu LL, Pond GR, Moore MJ. Gemcitabine concurrent with continuous infusional 5-fluorouracil in advanced biliary cancers: a review of the Princess Margaret Hospital experience. Ann Oncol. 2004;15:770–774. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdh172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Alberts SR, Al-Khatib H, Mahoney MR, Burgart L, Cera PJ, Flynn PJ, Finch TR, Levitt R, Windschitl HE, Knost JA, et al. Gemcitabine, 5-fluorouracil, and leucovorin in advanced biliary tract and gallbladder carcinoma: a North Central Cancer Treatment Group phase II trial. Cancer. 2005;103:111–118. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Park JS, Oh SY, Kim SH, Kwon HC, Kim JS, J-Kim H, Kim YH. Single-agent gemcitabine in the treatment of advanced biliary tract cancers: a phase II study. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2005;35:68–73. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyi021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Yonemoto N, Furuse J, Okusaka T, Yamao K, Funakoshi A, Ohkawa S, Boku N, Tanaka K, Nagase M, Saisho H, et al. A multi-center retrospective analysis of survival benefits of chemotherapy for unresectable biliary tract cancer. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2007;37:843–851. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hym116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eckel F, Schmid RM. Chemotherapy in advanced biliary tract carcinoma: a pooled analysis of clinical trials. Br J Cancer. 2007;96:896–902. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Valle JW, Wasan H, Johnson P, Bridgewater J, Maraveyas A, Jones E, Tunney V, Swindell R, on behalf of the ABC-01 study group. Gemcitabine, alone or in combination with cisplatin, in patients with advanced or metastatic cholangiocarcinoma (CC) and other biliary tract tumors: A multicenter, randomized, phase II (the UK ABC-01) study. Am Soc Clin Oncol. 2006:A98. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lee MA, Woo IS, Kang JH, Hong YS, Lee KS. Gemcitabine and cisplatin combination chemotherapy in intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma as second-line treatment: report of four cases. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2004;34:547–550. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyh099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Thongprasert S, Napapan S, Charoentum C, Moonprakan S. Phase II study of gemcitabine and cisplatin as first-line chemotherapy in inoperable biliary tract carcinoma. Ann Oncol. 2005;16:279–281. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdi046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Meyerhardt JA, Zhu AX, Stuart K, Ryan DP, Blaszkowsky L, Lehman N, Earle CC, Kulke MH, Bhargava P, Fuchs CS. Phase-II study of gemcitabine and cisplatin in patients with metastatic biliary and gallbladder cancer. Dig Dis Sci. 2008;53:564–570. doi: 10.1007/s10620-007-9885-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tanaka N, Yamakado K, Nakatsuka A, Fujii A, Matsumura K, Takeda K. Arterial chemoinfusion therapy through an implanted port system for patients with unresectable intrahepatic cholangiocarcinoma – initial experience. Eur J Radiol. 2002;41:42–48. doi: 10.1016/s0720-048x(01)00414-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cantore M, Mambrini A, Fiorentini G, Rabbi C, Zamagni D, Caudana R, Pennucci C, Sanguinetti F, Lombardi M, Nicoli N. Phase II study of hepatic intraarterial epirubicin and cisplatin, with systemic 5-fluorouracil in patients with unresectable biliary tract tumors. Cancer. 2005;103:1402–1407. doi: 10.1002/cncr.20964. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Vogl TJ, Zangos S, Eichler K, Selby JB, Bauer RW. Palliative hepatic intraarterial chemotherapy (HIC) using a novel combination of gemcitabine and mitomycin C: results in hepatic metastases. Eur Radiol. 2008;18:468–476. doi: 10.1007/s00330-007-0781-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Okuda K, Tanaka M, Shibata J, Ando E, Ogata T, Kinoshita H, Eriguchi N, Aoyagi S, Tanikawa K. Hepatic arterial infusion chemotherapy with continuous low dose administration of cisplatin and 5-fluorouracil for multiple recurrence of hepatocellular carcinoma after surgical treatment. Oncol Rep. 1999;6:587–591. doi: 10.3892/or.6.3.587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Peters GJ, Bergman AM, Ruiz van Haperen VW, Veerman G, Kuiper CM, Braakhuis BJ. Interaction between cisplatin and gemcitabine in vitro and in vivo. Semin Oncol. 1995;22:72–79. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moufarij MA, Phillips DR, Cullinane C. Gemcitabine potentiates cisplatin cytotoxicity and inhibits repair of cisplatin-DNA damage in ovarian cancer cell lines. Mol Pharmacol. 2003;63:862–869. doi: 10.1124/mol.63.4.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sawada N, Fujimoto-Ouchi K, Ishikawa T, Tanaka Y, Ishitsuka H. Antitumor activity of combination therapy with capecitabine plus vinorelbine, and capecitabine plus gemcitabine in human tumor xenograft models. Proc Am Assoc Cancer Res. 2002:A5388. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Iyer RV, Gibbs J, Kuvshinoff B, Fakih M, Kepner J, Soehnlein N, Lawrence D, Javle MM. A phase II study of gemcitabine and capecitabine in advanced cholangiocarcinoma and carcinoma of the gallbladder: a single-institution prospective study. Ann Surg Oncol. 2007;14:3202–3209. doi: 10.1245/s10434-007-9539-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kim MJ, Oh DY, Lee SH, Kim DW, Im SA, Kim TY, Heo DS, Bang YJ. Gemcitabine-based versus fluoropyrimidine-based chemotherapy with or without platinum in unresectable biliary tract cancer: a retrospective study. BMC Cancer. 2008;8:374. doi: 10.1186/1471-2407-8-374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gebbia N, Verderame F, Di Leo R, Santangelo D, Cicero G, Valerio M, Arcara C, Badalamenti G, Fulfaro F, Carreca I. A phase II study of oxaliplatin (O) and gemcitabine (G) first line chemotherapy in patients with advanced biliary tract cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23 suppl 16:A4132. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shamseddine A, Khalifeh MJ, Mourad FH, Chehal AA, Al-Kutoubi A, Abbas J, Habbal MZ, Malaeb LA, Bikhazi AB. Comparative pharmacokinetics and metabolic pathway of gemcitabine during intravenous and intra-arterial delivery in unresectable pancreatic cancer patients. Clin Pharmacokinet. 2005;44:957–967. doi: 10.2165/00003088-200544090-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vogl TJ, Schwarz W, Eichler K, Hochmuth K, Hammerstingl R, Jacob U, Scheller A, Zangos S, Heller M. Hepatic intraarterial chemotherapy with gemcitabine in patients with unresectable cholangiocarcinomas and liver metastases of pancreatic cancer: a clinical study on maximum tolerable dose and treatment efficacy. J Cancer Res Clin Oncol. 2006;132:745–755. doi: 10.1007/s00432-006-0138-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gusani NJ, Balaa FK, Steel JL, Geller DA, Marsh JW, Zajko AB, Carr BI, Gamblin TC. Treatment of unresectable cholangiocarcinoma with gemcitabine-based transcatheter arterial chemoembolization (TACE): a single-institution experience. J Gastrointest Surg. 2008;12:129–37. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0312-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Paule B, Herelle MO, Rage E, Ducreux M, Adam R, Guettier C, Bralet MP. Cetuximab plus gemcitabine-oxaliplatin (GEMOX) in patients with refractory advanced intrahepatic cholangiocarcinomas. Oncology. 2007;72:105–110. doi: 10.1159/000111117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Clark JW, Meyerhardt JA, Sahani DV, Namasivayam S, Abrams TA, Stuart K, Bhargava P, Blaszkowsky LS, Jain SR, Zhu AX. Phase II study of gemcitabine, oxaliplatin in combination with bevacizumab (GEMOX-B) in patients with unresectable or metastatic biliary tract and gallbladder cancers. J Clin Oncol. 2007;25 suppl 18S:A4625. [Google Scholar]