Abstract

Borrelia burgdorferi surface lipoproteins are essential to the pathogenesis of Lyme borreliosis, but the mechanisms responsible for their localization are only beginning to emerge. We have previously demonstrated the critical nature of the amino-terminal ‘tether’ domain of the mature lipoprotein for sorting a fluorescent reporter to the Borrelia cell surface. Here, we show that individual deletion of four contiguous residues within the tether of major surface lipoprotein OspA results in its inefficient translocation across the Borrelia outer membrane. Intriguingly, C-terminal epitope tags of these N-terminal deletion mutants were selectively surface-exposed. Fold-destabilizing C-terminal point mutations and deletions did not block OspA secretion, but rather restored one of the otherwise periplasmic tether mutants to the bacterial surface. Together, these data indicate that disturbance of a confined tether feature leads to premature folding of OspA in the periplasm and thereby prevents secretion through the outer membrane. Furthermore, they suggest that OspA emerges tail-first on the bacterial surface, yet independent of a specific C-terminal targeting peptide sequence.

Keywords: Lyme borreliosis, spirochete, virulence factor, lipoprotein, secretion

Introduction

Bacterial lipoproteins are a ubiquitous subclass of membrane proteins characterized by peripheral association via a covalent N-terminal acyl modification (Hantke and Braun, 1973). Precursors are synthesized in the cytoplasm with a signal II peptide containing a ‘lipobox’ lipidation motif ending in an absolutely conserved Cys (von Heijne, 1989). In diderm (Gupta, 1998), e.g. Gram-negative bacteria, cleavage of the signal peptide and Cys lipidation occurs on the periplasmic side of the inner membrane (IM) after Sec-dependent translocation (Economou et al., 2006; Sankaran and Wu, 1994). Subsequent sorting of lipoproteins within the periplasmic space is carried out by the multi-component Lol system (Narita et al., 2004) based on rules first derived in E. coli (Yamaguchi et al., 1988). Established pathways of lipoprotein translocation through the outer membrane (OM) involve either a Type II or Type V/“autotransporter” secretion system (Pugsley, 1993; Francetic and Pugsley, 2005; Sauvonnet and Pugsley, 1996; van Ulsen et al., 2003)

In Borrelia burgdorferi, the spirochetal agent of Lyme borreliosis, numerous major outer surface lipoproteins contribute to the host-pathogen interface and are therefore critical to the pathogenicity of the organism (Fraser et al., 1997; Casjens et al., 2000; Haake, 2000). In a prior study, we began to characterize the localization requirements of OspA, a major B. burgdorferi surface lipoprotein (Bergström et al., 1989), tick colonization factor (Pal et al., 2004) and target of a first-generation Lyme disease vaccine (Steere et al., 1998). The first five residues (lipo-Cys17 through Val21) of the 12-amino acid tether domain of mature OspA were sufficient for proper lipidation and transport of a monomeric fluorescent protein (mRFP1) reporter to the Borrelia cell surface (Schulze and Zückert, 2006). Acidic residues functioned as IM retention signals in a particular N-terminal context different from the established ‘+2/+3/+4’ rules. Otherwise, empirical mutagenesis of the entire OspA tether (lipo-Cys17 through Asn28) failed to hinder surface localization. This led to our initial conclusion that, in the absence of a retention signal, Borrelia lipoproteins are transported to the cell surface by default, likely using an incomplete set of borrelial Lol homologs (Schulze and Zückert, 2006). In the present study, we narrowed the tether region crucial for translocation of OspA across the OM to four contiguous central residues. Further modification of these mislocalized tether mutants by C-terminal epitope tagging, truncation and point mutation revealed both structural requirements and potential directionality of OspA translocation through the borrelial OM.

Results

Individual deletion of a subset of central tether residues disrupts OM translocation

We previously identified a single-amino acid tether deletion mutant of OspA, OspAΔL24, that had an OM translocation defect: it was largely resistant to in situ surface proteolysis by proteinase K and localized to the inner leaflet of the OM (shown as control in Figs. 1A & 2B; (Schulze and Zückert, 2006). Translocation of OspAΔL24 could be completely restored by the insertion of an Ala residue at an alternative location within the tether (OspAΔL24ΩA27; Figs. 1A & 2B). This suggested that the identity of the missing Leu residue itself was not the critical determinant of surface localization. Indeed, the previously described removal of Leu24 from a full-length OspA tether fusion to mRFP1 (OspA28ΔL24:mRFP1; shown as control in Figs. 1A & 2A) had no detrimental effect on secretion to the cell surface (Schulze and Zückert, 2006). Because of the different contexts of ΔLeu24 in wild-type OspA and OspA28:mRFP1, we surmised that other factors were contributing to the surface localization of OspA28ΔL24:mRFP1.

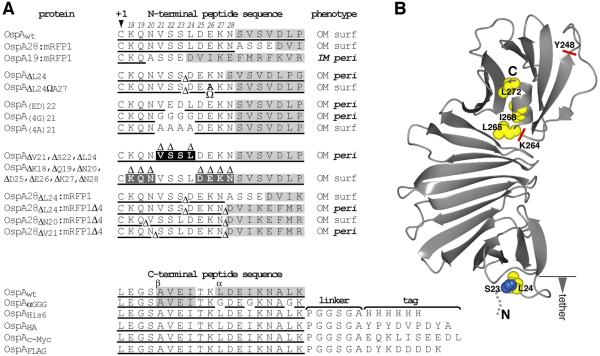

Figure 1. N- and C-terminal sequences of OspA lipoprotein mutants.

(A) Deletions (Δ) and insertions (Ω) mutations are labelled with respect to the sequence of wild type (wt) OspA. Δ symbols within the sequence mark the deletion, and Δ symbols above the sequence indicate the deleted amino acid below. Please note that removal of either the Ser22 or Ser23 codon in the OspA tether yields identical peptides. Therefore, only the ΔSer22 mutant was generated. Gray shading indicates the structurally confined portion of the protein. Underlined sequence indicates the portion of the construct derived from wild type OspA. N-terminal mutant protein phenotypes are summarized by membrane (inner membrane, IM; outer membrane, OM), surface (surf) or periplasmic (peri) localization. (B) A ribbon representation of the OspA tertiary structure (PDB ID 1OSP, (Li et al., 1997) was generated using the CCP4 software for Macintosh (version 1.130.0; (Potterton et al., 2002). Mutated residues are highlighted as blue (Ser) or yellow (Leu or Ile) spheres representing the Cα and side chain atoms. Red lines indicate the sites of C-terminal truncations.

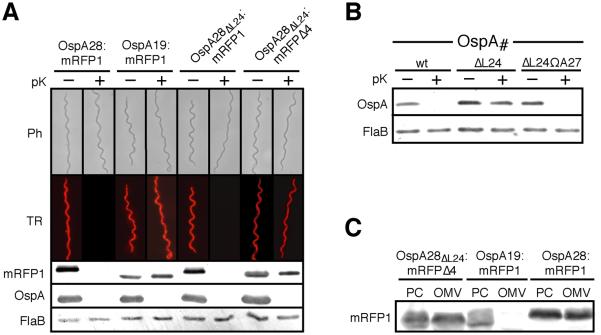

Figure 2. Role for OspA Leu24 in OM translocation.

(A) Epifluorescence micrographs of B. burgdorferi expressing various red fluorescent protein fusions before and after treatment with proteinase K (pK). Ph, phase contrast; TR, Texas Red filter. Supporting Western immunoblots for mRFP1, using surface-exposed OspA and periplasmic FlaB as controls are shown below. (B) Proteinase K accessibility of OspA tether mutants compared to OspAwt. FlaB is used as a periplasmic, protease-resistant control. (C) Membrane fractionation immunoblots of OspAΔL24:mRFPΔ4 compared to surface-localized OspA28:mRFP1 and IM-localized OspA19:mRFP1 controls (Schulze and Zückert, 2006). OM, outer membrane vesicle fraction; PC, protoplasmic cylinder fraction (also containing intact cells; (Schulze and Zückert, 2006).

mRFP1 is a monomeric derivative of dsRed, a tetrameric red fluorescent coral protein (Campbell et al., 2002). The first five amino-terminal residues of dsRed do not appear in its crystal structure (PDB entry IG7K; (Yarbrough et al., 2001) due to the absence of electron density, which is indicative of flexibility of this region. Our original OspA:mRFP1 fusions omitted only the N-terminal fMet of mRFP1. Based on the structure of dsRed, our original fusion constructs likely contained an additional flexible linker between the OspA tether sequence and the structurally confined region of mRFP1. To determine whether this four residue linker of mRFP1 (Ala2-Ser3-Ser4-Glu5) contributed to the observed discrepancy between the localization of OspAΔL24 and OspA28ΔL24:mRFP1, we removed it to yield the truncated reporter protein mRFPΔ4. An OspA28:mRFPΔ4 fusion was transported as effectively to the surface of Borrelia as the original fusion to full-length mRFP1 OspA28:mRFP1 (Figs. 1A, 2A & 3C). Removal of Leu24 from this new fusion resulted in a phenotype that behaved in all respects like the OspAΔL24 mutant. OspA28ΔL24:mRFPΔ4 was resistant to proteinase K digestion (Fig. 2A) and also localized to the OM with the same efficiency as surface-exposed OspA28:mRFP1 (Fig. 2C). The ΔLeu24 mutation thus resulted in a lipoprotein with a true defect in translocation across the OM, which could be overcome in cis by the presence of an extra Ala residue or an N-terminal mRFP1 tetrapeptide in the membrane-distal portion of the tether.

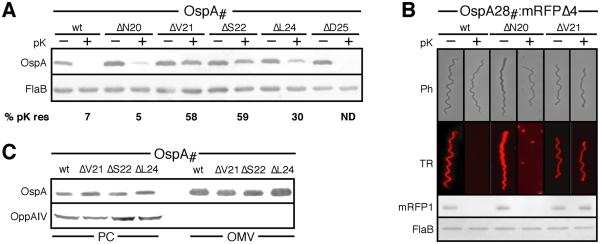

Figure 3. Localization of single-residue deletion OspA tether mutants.

(A) Proteinase K (pK) accessibility assays for individual residue deletions from the OspA tether. Quantitative chemiluminescent immunoblot images were acquired using a Fuji LAS-4000 Luminescent Image Analyzer. The mean percentage of proteinase K resistance (% pK res) of OspA mutants was calculated from densitometry data from three independent in situ proteolysis assays with normalization to the FlaB signal. (B) Epifluorescence micrographs of B. burgdorferi B313 expressing various OspA tether-mRFPΔ4 fusions before and after treatment with proteinase K (pK). Ph, phase contrast; TR, Texas Red filter. Supporting Western immunoblots for mRFP1, using surface-exposed OspA and periplasmic FlaB as controls are shown below. (C) Membrane fractionation immunoblots of single-residue OspA deletions mutants compared to OspAwt. OppAIV served as IM control. OM, outer membrane vesicle fraction; PC, protoplasmic cylinder fraction (also containing intact cells; (Schulze and Zückert, 2006).

To determine whether the deletion of any single residue within the tether of OspA resulted in a general defect in transport of lipoproteins across the OM, we chose a second residue, Asn20, and removed it from the tether of both wild-type OspA and OspA28:mRFPΔ4, creating OspAΔN20 and OspA28ΔN20:mRFPΔ4, respectively (Fig. 1A). In both instances, this mutation had no effect on the transport of the respective lipoproteins to the cell surface (Figs. 3A & 3C). Broadening our search, we next removed each of the remaining residues individually from the OspA tether (Fig. 1A). Please note that removal of either the Ser22 or Ser23 codon yields identical peptides. Therefore, only the ΔSer22 mutant was generated. Individual deletion of residues 18 to 20 and 25 to 28, including ΔAsn20 and ΔAsp25, had no impact on cell surface localization of OspA (Fig. 3A; not shown). In contrast, removal of Val21 or Ser22 led to a sorting-defective phenotype similar to the ΔLeu24 mutant. OspAΔV21, OspAΔS22 and OspAΔL24 mutants were released to the OM with OspAwt-like efficiency (Fig. 3D) and were significantly protected from proteinase K treatment (Fig. 3A). However, the resistance to protease was approximately two-fold higher for the ΔVal21 and ΔSer22 mutants versus the ΔLeu24 mutant (Fig. 3B). This indicated a clear hierarchy of importance for residues within the OspA tether for OM translocation.

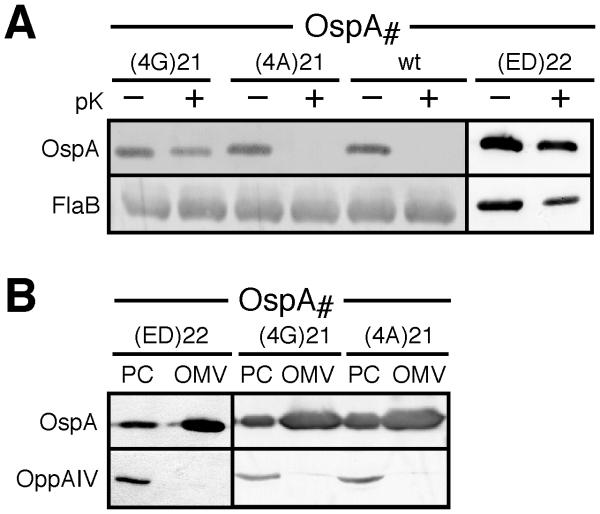

A previous Ala scanning mutagenesis of the OspA28:mRFP1 tether had found no effect on surface localization (Schulze and Zückert, 2006). Extending these studies to full-length OspA, we changed the Val21-Ser22-Ser23-Leu24 sequence examined above to an Ala tetrapeptide. The resulting OspA(4A)21 mutant still successfully translocated to the cell exterior (Fig 4A). Changing the sequence to a Gly tetrapeptide, however, resulted in a significant sorting defect: the OspA(4G)21 mutant was as protease-resistant as OspAΔV21 and OspAΔS22 (Fig. 4A) and still localized to the OM (Fig 4B). Further analysis of OspA(ED)22, a Ser22-Ser23 to Glu-Asp mutant previously deemed toxic due to a low transformation efficiency (Schulze and Zückert, 2006), showed the same OM mislocalization phenotype (Figs. 4A & 4B). Together, these findings further supported our earlier conclusions (Schulze and Zückert, 2006) that overall tether length does not play an exclusive role in the OM translocation process. Rather, maintenance of a defined central tether region appeared to be critical for proper lipoprotein localization.

Figure 4. Localization of quadruple and double OspA tether substitution mutants.

(A) Immunoblots of proteinase K (pK) accessibility assays for Val-Ser-Ser-Leu OspA tetrapeptide and Asp-Glu substitution OspA tether mutants. FlaB was used as a periplasmic, protease-resistant control. (B) Membrane fractionation immunoblots of the VSSL mutants compared to wild type OspA tether substitution mutants. OppAIV (Bono et al., 1998; Schulze and Zückert, 2006) served as IM control. OM, outer membrane vesicle fraction; PC, protoplasmic cylinder fraction (also containing intact cells; (Schulze and Zückert, 2006).

C-terminal epitope tagging of tether mutants reveals a potential tail-first mechanism for OspA surface exposure

Having identified the residues critical to OM translocation of OspA, we next sought to clarify their specific contributions to this process. We engineered a hexa-His (His6) epitope tag with a Pro-Gly-Gly-Ser-Gly-Ala linker onto the C-termini of OspA, OspAΔS22, and OspAΔL24 (Fig. 1A). Western blotting using an antibody to OspA showed that addition of this C-terminal tag did not affect the surface phenotype of the proteins. Like their untagged counterparts, OspAΔS22-His6 and OspAΔL24-His6 were largely protected from proteinase K (Fig 5A). Western blots using a monoclonal antibody against the His6 tag, however, showed that the extreme C-terminus for all three proteins was accessible to the protease (Fig. 5A). Accordingly, the apparent molecular weight of the OspA-His protein bands, unlike their untagged equivalents, decreased by an estimated 1-2 kDa following proteolytic treatment with as little as 6.25μg/ml proteinase K (Figs. 5A). This decrease in size was consistent with the removal of the 1.3 kDa linker-His6-tag peptide. Probing with a monoclonal antibody recognizing the C-terminal α-helix (Fig. 5A) indicated that only the epitope tag is accessible for proteolytic attack on the bacterial surface while OspA remains sequestered in the periplasm or in the OM. Proteinase K assays of whole-cell sonicates demonstrated that the C-terminal His6 tag was not inherently more sensitive to proteinase K than OspA (data not shown). None of the mutants had a discernible growth defect in culture medium (data not shown), nor were other lipoproteins blocked from reaching the bacterial surface (e.g. OspA in the OspA28ΔL24:mRFPΔ4-expressing strain in Fig. 2A).

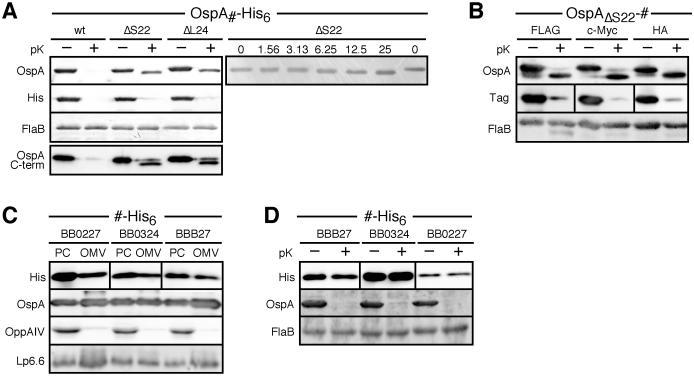

Figure 5. Localization of a C-terminal epitope tags in OspA tether deletion mutants.

(A) Immunoblots of His6-tagged OspA subsurface mutants before and after proteinase K (pK) treatment. FlaB was used as a periplasmic, protease-resistant control. Note the slight downward shift of OspAΔS22-His6 and OspAΔL24-His6 anti-OspA-reacting bands and the concurrent loss of the His6 epitope upon in situ proteolytic treatment (left panel). To determine the amount necessary for cleavage of the His6 tag, OspAΔS22-His6 was subjected to shorter treatment with lower concentrations of protease (15 min vs. 1 h incubation with 1.56 to 50 μg/ml vs. the standard 200 μg/ml; right panel). (B) Immunoblots of OspA subsurface mutants with FLAG, c-Myc and HA C-terminal tags before and after proteinase K (pK) treatment. FlaB was used as a periplasmic, protease-resistant control. Note the tag accessibility phenotypes identical to the His6-tagged OspAΔS22 in panel A.

(C) Membrane fractionation and (D) proteinase K (pK) accessibility immunoblots for C-terminally His6-tagged BB0227, BB0324, and BBB27 lipoproteins. OM, outer membrane vesicle fraction; PC, protoplasmic cylinder fraction (also containing intact cells; (Schulze and Zückert, 2006). Lipoproteins OppAIV (Bono et al., 1998; Schulze and Zückert, 2006) and Lp6.6 (Katona et al., 1992; Lahdenne et al., 1997) are included as IM and periplasmic OM controls, respectively. FlaB was used as periplasmic, protease-resistant control.

We performed two sets of experiments to exclude a tag-dependent localization artifact. First, we replaced the His6 tag peptide in OspAΔS22-His with FLAG, c-Myc and hemagglutinin (HA) tag peptides, respectively (Fig. 1A). All three tag variants displayed protease accessibility phenotypes identical to OspAΔS22-His: the C-terminal tags were accessible, while the remainder of OspA was not (Fig. 5B). Second, we checked for protease accessibility of the His6 C-terminal tag fused to three periplasmic OM lipoproteins encoded by open reading frames BBB27 (Jewett et al., 2007), BB0227 and BB0324 (Fig. 5B). None of the three proteins displayed their C-terminal tags on the bacterial surface (Fig. 5C). Proteinase K treatment of whole-cell sonicates demonstrated that these proteins were not inherently resistant to proteolysis (data not shown). The phenotype of the mislocalized OspA tether mutants is thus clearly distinguishable from that of wild type lipoproteins innately targeted to the inner leaflet of the OM. Together, these data indicated that the ΔSer22 and ΔLeu24 mutations did not interfere with proper periplasmic translocation to the OM, but rather led to an aborted translocation of OspA through the borrelial OM.

Fold-disrupting C-terminal mutations indicate that OM translocation requires an unfolded OspA substrate

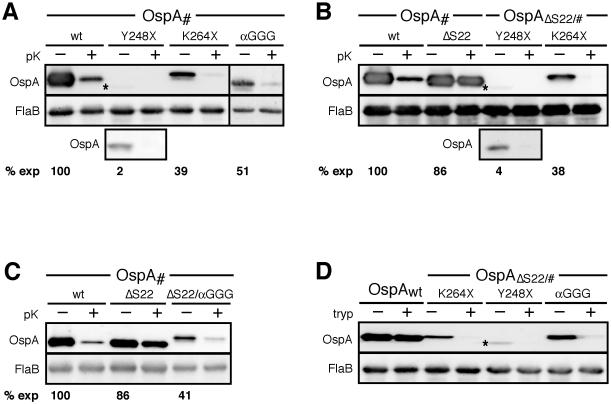

Since the C-terminal epitope tag sequences are predicted to assume a disordered conformation, we hypothesized that this property contributed to their selective surface exposure. We therefore designed a set of mutations disrupting C-terminal structural elements in both OspAwt and OspAΔS22: (i) two stop codons replacing Tyr248 and Lys264 (Fig. 1B) truncated the protein after the penultimate β-strand (OspAY248X) and before the C-terminal α-helix (OspAK264X), respectively, and (ii) a triple Gly mutant (OspAαGGG) replaced Leu265, Ile268 and Leu272 in the C-terminal α-helix (Fig. 1). All mutant proteins were detected at decreased levels compared to the wild type OspA protein (Figs. 6A, B and C). Based on densitometry, the truncation at Tyr248 was most severe, leading to an approximately 50-fold reduction in protein level in both OspAwt and OspAΔS22 backgrounds. The triple Gly substitution within the C-terminal α-helix or its removal led to an approximately 3-fold reduction (Fig. 6C). This indicated that all C-terminal mutants were indeed destabilized, i.e. targeted for degradation due to compromised folding. Deletion of the C-termini did not affect surface exposure of otherwise wild type OspA (Fig. 6A). We therefore concluded that the OspA C-terminal peptide sequence is not required for OM translocation. However, introduction of all three C-terminal mutations into the OspAΔS22 mutant led to surface localization (Figs. 6 B and C). In contrast to the trypsin-resistant OspAwt (Barbour et al., 1984; Bunikis and Barbour, 1999), the surface-displayed N- and C-terminal OspA mutants became susceptible to trypsin (Fig. 6D), confirming the fold-destabilizing effect of the C-terminal mutations. Together, these data were in accordance with the C-terminal epitope tag mutant dataset and further supported our conclusion that a C-terminally unfolded OspA peptide can serve as the initial substrate for secretion through the OM.

Figure 6. Localization of C-terminal fold-disrupting OspA mutants.

(A) Immunoblots of proteinase K (pK) accessibility assays of C-terminal truncations and point mutants in otherwise wild type OspA. An asterisk labels the barely visible band for the OspAY248X mutant. To better demonstrate surface exposure, an immunoblot of a 5-fold concentrated sample is shown in the third row of the blot. Densitometry data of two independent in situ proteolysis assays yielded the mutants' mean expression level compared to OspAwt (% exp). (B) Proteinase K accessibility of C-terminal truncations in combination with an OspA tether ΔSer22 deletion. Surface accessibility of the OspAΔS22/Y248X mutant is shown as in panel A. (C) Protease accessibility of the C-terminal triple Gly substitution mutants. Protein stability data were obtained as in panel A. (D) Trypsin (tryp) susceptibility of surface-localized N- and C-terminal double mutants compared to wild type OspA. FlaB was used as periplasmic control in all panels.

Discussion

Ever since the discovery that lipoproteins are directed to different E. coli membranes by the identity of their ‘+2’ N-terminal amino acid (Yamaguchi et al., 1988), sorting studies have focused on the N-terminal primary sequences. A growing number of lipoprotein mutants expressed in different experimental systems now provides mounting evidence that the original ‘+2 rule’ is far from universal. Exceptions are common even in E. coli, where the +3 position can also affect localization (Wu et al., 2006; Lewenza et al., 2006; Masuda et al., 2002; Seydel et al., 1999; Terada et al., 2001; Seiffer et al., 1993). Furthermore, lipoprotein sorting in other Gram-negative pathogens such as Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Narita and Tokuda, 2007) and Yersinia pestis (Silva-Herzog et al., 2008) appears to rely on N-terminal signals at positions +3/+4 and beyond.

Our previous work demonstrated that these established sorting rules do not apply to Borrelia lipoproteins, but that Asp and Glu in a particular tether context can lead to an IM release defect (Schulze and Zückert, 2006). In this study, the individual deletion of four N-terminal residues, Val21-Ser22-Ser23-Leu24, led to a significant OM translocation defect of the major surface lipoprotein OspA, which could be rescued by introduction of additional C-terminal, fold-destabilizing mutations. Collectively, these findings indicate that IM release and OM translocation of B. burgdorferi lipoproteins are two separate steps governed by separate N-terminal attributes.

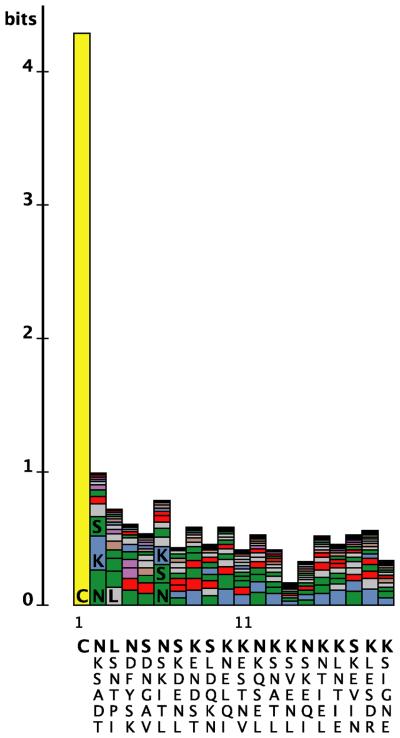

The mechanistic underpinnings of lipoprotein secretion in B. burgdorferi and the contribution of individual tether residues to this process await further investigation. Based on our current data, it is clear that Val-Ser-Ser-Leu itself does not represent a canonical motif required for lipoprotein OM translocation: (i) the four residues can be replaced by an Ala stretch without compromising OspA surface localization; (ii) OspA tether peptides from different B. burgdorferi sensu lato isolates diverge, ranging from single Ser23Gly or Ser23Thr substitutions (e.g. GenBank accession numbers CAB64766 or CAA44492) to significant alterations (e.g. GenBank accession number ABR22628) (data not shown); and (iii) N-termini of B. burgdorferi lipoprotein tether sequences beyond the N-terminal Cys are degenerate (Fig. 7). Yet, these regions are well populated by residues unlikely to be conducive to the formation of extensive secondary structure. In fact, nearly all crystal structures of lipoproteins deposited in the PDB are missing large N-terminal segments (Table 1). Either the N-termini had to be removed to obtain structurally confined protein crystals (e.g. for Borrelia turicatae Vsp1, refs. (Lawson et al., 2006; Zückert et al., 2001)), or the polypeptide chains did not resolve (e.g. for E. coli LolB; (Takeda et al., 2003). Lys, Asn, Ser, Asp and Glu, which are especially common in regions of short disorder (Peng et al., 2006), are the most common residues within the first fifteen positions of the 127 known or predicted B. burgdorferi lipoproteins. In accordance, the crystal structure of strain B31 OspA showed defined electron densities starting at Ser23 (Li et al., 1997), and NMR studies of OspA in solution revealed that Val21 and Ser22 had greater main-chain rotational freedom than other residues in the peptide (Pham and Koide, 1998). Together, this suggests that disorder is not a pervasive, but rather localized tether feature providing a defined degree of peptide backbone flexibility. This might explain why the tetrapeptide's substitution with four alanines was tolerated, but substitution with four glycines was detrimental. In contrast to Ala residues, Gly residues are not restricted in their backbone rotational freedom (Chakrabartty et al., 1991). A Gly tetrapepide therefore might introduce excessive entropy, which has been shown to affect both protein folding and protein-protein interactions (Brady and Sharp, 1997). It is particularly tempting to speculate on a specific role for the common Ser tether residues, as the mRFP1-derived Ala-Ser-Ser-Glu peptide provided a dominant surface phenotype to otherwise subsurface OspA tether deletion mutants.

Figure 7. Sequence complexity of B. burgdorferi lipoprotein tethers.

A LogoBar (Perez-Bercoff et al., 2006) representation of the N-terminal sequence of known or predicted mature B. burgdorferi lipoproteins (Setubal et al., 2006) illustrates the complexity of the tether. The height of each column, measured in bits, is proportional to the lack of complexity at a given position. The columns are stacked from the bottom starting with the most frequently occurring residue at that position and continuing upward. Below each column are the six most frequently occurring residues at each position, in order of frequency from top (bold) to bottom. Colors represent residues with similar characteristics.

Table 1.

Examples of N-terminal tether regions of bacterial lipoproteins.

| Organism | Protein | N-terminal Sequence of Mature Lipoprotein | Lengthδ | Reference | PDB-ID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Escherichia coli | LolB | CSVTTPKGPGKSPD | 14 | (Takeda et al., 2003) | 1IWN |

| Escherichia coli | AcrA | CDDKQAQQGGQQMPAVGVVTVKTEPLQITT | 30 | (Mikolosko et al., 2006) | 2F1M |

| Shigella flexneri | MxiM | CALKSSSNSE | 9 | (Lario et al., 2005) | 1Y9L |

| Pseudomonas aeruginosa | MexA | CGKSEAPPPAQTPEVGIVTLEAQTVTLN | 28 | (Higgins et al., 2004) | 1T5E |

| Neisseria meningitidis | PilP |

CSQGSEDLNEWMAQTRREAKAEIIPFQAPTLPVAPVYSPPQL TGPNAFDFRRMETDKKGENAPDTKRIK |

65 | (Golovanov et al., 2006) | 2IVW |

| Borrelia burgdorferi | OspA | CKQNVSSLDEKN | 12 | (Li et al., 1997) | 1OSP |

| OspC | CNNSGKDGNTSANSADESVKGP | 22 | (Kumaran et al., 2001) | 1GGQ | |

| BbCRASP-1 |

CAPFSKIDPKANANTKPKKITNPGENTQNFEDKSGDLSASDE KIME |

46 | (Cordes et al., 2005) | 1W33 | |

| Borrelia turicatae | Vsp1 | CNNSGTSPKDGQAAKSDGTVI | 21 | (Lawson et al., 2006) | 2GA0 |

| Leptospira interrogans | Lp49 | CKSGDFSLLSSPINREKNG | 19 | (Giuseppe et al., 2008) | 3BWS |

| Treponema pallidum | PnrA | CSKSDRPQMGNAGGAEGGDF | 20 | (Deka et al., 2006) | 2FQW |

| Mycobacterium tuberculosis | LppX | CSSPKPDAEEQGVPVSPTA | 19 | (Sulzenbacher et al., 2006) | 2BYO |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | PsaA | CASGKKDAASGQK | 13 | (Lawrence et al., 1998) | 1PSZ |

Length is defined as the number of N-terminal residues devoid of electron density in the associated crystal structure plus those up to but not part of the first secondary structural element (i.e. α-helix, β-sheet).

The tetrapeptide region may function as a hinge (Gerstein et al., 1994) that is required for OspA's hand-off from a periplasmic chaperone to an OM lipoprotein translocation complex. As observed in kinetic studies of enzymes with hinged lids (Kempf et al., 2007), changes in hinge flexibility may in this case lower the kinetics and efficacy of transfer and allow for premature folding, leading to a translocation defect. Alternatively, alteration of this tether region may block its interaction with a periplasmic “holding” chaperone, thereby preventing conformational re-organization and maintenance of a translocation-competent state. A similar, although cytoplasmic mechanism has been described in Yersinia pseudotuberculosis, where a disorder-to-order transition in the N-terminus of the secreted effector YopE induced by its chaperone SycE is required for the effector's transport from the bacterial cytoplasm through the Type III needle apparatus (Rodgers et al., 2008). Based on our current data, such a tether-chaperone interaction would be insufficient to prevent degradation of the C-terminally mutated OspA molecules. Due to the limited coding capacity of the B. burgdorferi genome (Fraser et al., 1997; Casjens et al., 2000), a lipoprotein holding chaperone would also likely be promiscuous, i.e. recognize its substrates independent of sequence similar to cytoplasmic SecB (Randall and Hardy, 2002). Interestingly, the periplasmic Skp protein has been proposed to play such a role for integral outer membrane proteins (Bos et al., 2007). In synteny with other bacteria, the B. burgdorferi Skp homolog ORF BB0796 is found immediately downstream of the BamA homolog ORF BB0795 (Zückert and Bergström, 2010). Depletion of BB0795 indeed affects OM protein content (Lenhart and Akins, 2009). The biological role of BB0796 remains to be determined.

While the requirement for a translocation-competent, at least partially unfolded state of substrate has been observed in OM passage of ‘autotransporter’/Type V passenger domains (Jong et al., 2007), the potential initiation of OspA secretion at its C-terminus is intriguing, but also presents two conundrums. First, it would require that substrate recognition by the translocation machinery occur independently of a targeting primary peptide sequence: four different C-terminal epitope tags produced identical phenotypes, the C-terminal OspA peptides were dispensable for surface localization and, as previously demonstrated (Schulze and Zückert, 2006), could be replaced by an unrelated mRFP1 sequence. Secondly, a C to N terminus process would entail that translocation initiate at the free, untethered end of the molecule, which poses a challenge for substrate delivery to the translocation machinery. The preserved targeting of the OM translocation-defective OspA mutants to the inner leaflet of the OM may provide sufficient proximity of the protein's C-terminus to the translocation machinery. For wild type OspA, a C- to N-terminus directionality might be assisted by the lower thermodynamic stability of the lipoprotein's C-terminal globular domain (Nakagawa et al., 2002). Alternatively, the exposed epitope tag residues may structurally mimic other domains of OspA that are presented to the OM translocation machinery when complexed with the above stipulated holding chaperone.

Our finding that the C-terminal epitope tags did not lead to an observable growth defect indicates that the lipoprotein OM translocation machinery is either (i) non-essential, (ii) not saturated by the accumulating levels of mislocalized OspA, or (iii) prevented from being clogged with mutant OspA proteins irreversibly locked in an OM transition state. Given the abundance of surface lipoproteins and their importance for OM function, the first two interpretations are unlikely to prevail. The last hypothesis would imply the presence of a transport quality control mechanism at the OM, which would here lead to abortion of OspA mutant translocation and “backsliding” of the C-terminal epitope tags into the periplasm.

We therefore envision a borrelial lipoprotein secretion mechanism, in which the N-terminal lipid anchor of the substrate is transiently inserted into the periplasmic leaflet of the OM, while the unfolded peptide begins to be threaded through an OM pore. In the absence of ATP and proton-motive force, vectorial translocation most likely would be driven by progressive extracellular folding and assembly, as proposed for other surface protein translocation processes (Schiebel et al., 1989; Clantin et al., 2004; Junker et al., 2006). Ultimately, the N-terminal lipid anchor would be flipped from the periplasmic to the outer surface leaflet of the OM lipid bilayer, similar to the ‘card reader’ mechanism proposed for lipid flippases (Pomorski and Menon, 2006). To test this working model, our future experiments will focus on the generation of reversible lipoprotein translocation intermediates and conditional secretion pathway mutants, using a recently described tetracycline-responsive hybrid B. burgdorferi promoter (Whetstine et al., 2009). At the same time, an extension of our studies to the structurally distinct, dimeric Borrelia OspC/Vsp lipoproteins (Eicken et al., 2001; Kumaran et al., 2001; Lawson et al., 2006) will begin to define canonical or lipoprotein-specific requirements for secretion.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial strains and growth conditions

B. burgdorferi strains B31-e2 or B313, both clones of type strain B31 (ATCC 35210), were used for expression of OspA-mRFP or OspA mutants, respectively (Table 1). B31-e2 (Babb et al., 2004) expresses endogenous OspA, but B313 lacks the lp54 plasmid encoding ospA (Sadziene et al., 1993; Zückert et al., 2004; Zückert et al., 1999). B. burgdorferi were cultured in liquid or solid BSK-II medium at 34°C under 5% CO2 (Barbour, 1984; Zückert, 2007). E. coli strains TOP10 (Invitrogen) and XL10-Gold (Stratagene) were used for recombinant plasmid construction and propagation and grown in Luria Bertani (LB) broth or on LB agar (Difco).

Lipoprotein Fusion and Point Mutants

Expression of all lipoprotein constructs is driven by the constitutive B. burgdorferi flagellin flaB promoter (PflaB) from pBSV2 (Stewart et al., 2001) shuttle vector derivatives (Table S1). Mutations were introduced using the QuikChange-II XL site-directed mutagenesis kit (Stratagene) or mutagenic PCR with Pfx (Invitrogen) or Phusion (NEB/Finnzymes) high-fidelity DNA polymerases. Custom oligonucleotides (IDT DNA) are listed in Table S2.

The OspA C-terminal linker-His6-tag (Fig. 1A) was added in two steps via a linker-less intermediate. First, a PCR amplicon obtained with KpnPflaB-fwd and OspAhisXba-rev on a pRJS0998 template was digested with KpnI and XbaI and ligated with a KpnI-XbaI-cut pBSV2, resulting in pSC0998. Then, a 6-amino acid linker between OspA and the His6 epitope was introduced through a QuikChange reaction, resulting in pSC0999. Due to a cloning artefact, pSC0999 lacked the pBSV2 MCS BamHI and XmaI sites. His6-tags were introduced into OspA tether mutant plasmids by ligating a pSC0999-derived HindIII fragment containing the 3′ end of the OspA-His into HindIII-cut plasmid backbones. OspAΔS22 was tagged with C-terminal c-Myc, HA and FLAG epitopes using PCR: amplicons obtained with PflaBNdeospA-fwd and tag-specific reverse primers on a pRJS1140 template were digested with ScaI and XbaI and ligated into an identically cut pRJS1140 plasmid backbone. Epitope-tagging of B. burgdorferi lipoproteins was facilitated by modification of pSC0999: a silent XmaI site was introduced into the six amino-acid linker preceding the His6 tag (Fig. 1), and an NdeI site in the Kanr gene cassette was removed, yielding pSC1000. Lipoprotein genes were amplified from B. burgdorferi clone B31-A3 (Elias et al., 2002) genomic DNA using gene-specific primers, the amplicons were digested with NdeI and XmaI and ligated into pSC1000. All plasmids were verified by DNA sequencing (Center for Genetic Medicine, Genomics Core Facility, Northwestern University Medical Center, Chicago, IL, and ACGT, Inc., Wheeling, IL).

B. burgdorferi cells were transformed with 1-40 μg of plasmid DNA by electroporation using established protocols (Stewart et al., 2001; Samuels, 1995). Transformants were selected in solid BSK-II containing 200 μg/ml kanamycin, with three independent clones expanded in selective liquid BSK-II. Plasmid profiles were determined by PCR using plasmid-specific oligonucleotide primers (Purser and Norris, 2000; Labandeira-Rey and Skare, 2001).

Protein Gel Electrophoresis and Immunoblot analysis

Proteins were separated by SDS-PAGE and visualized by Coomassie blue staining. For immunoblots, proteins were electrophoretically transferred to nitrocellulose membranes (Immobilon-NC, Millipore) using a Transblot-SD Semi-Dry Transfer Cell (Bio-Rad) as described (Schulze and Zückert, 2006). Membranes were blocked and incubated with antibodies in 5% dry milk, 20 mM Tris-500 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20. Antibodies used were anti-mRFP1 rabbit polyclonal antiserum (1:1,000 dilution), anti-OppAIV rabbit polyclonal antiserum (1:100; (Bono et al., 1998), or mouse monoclonal antibodies against Lp7.5/6.6 (1:500, MAb240.7; (Katona et al., 1992), OspA (1:25 dilution, H5332; (Barbour et al., 1983), the OspA C-terminus (1:1000, 336.1, (Huang et al., 1998), FlaB (1:25, H9724; (Barbour et al., 1986), His6 (1:3000, HIS-1, H1029, Sigma), c-Myc (1:1000, 9E10, M4439, Sigma), FLAG (1:10000, M2, F3165, Sigma), and HA (1:1000, HA-7, H9658, Sigma). Secondary antibodies were alkaline phosphatase-conjugated goat-anti-rabbit IgG (H+L) or goat-anti-mouse IgG (H+L) (Sigma). Alkaline phosphatase substrates were 1-Step NBT/NCIB (Pierce) for colorimetric and CDP-Star (Amersham Biosciences) for chemiluminescent detection.

Protease and Antibody Accessibility Assays

To assess protein surface exposure by protease accessibility, intact B. burgdorferi cells were harvested, washed and treated in situ with concentrations of proteinase K (Invitrogen) ranging from 1.56μg/ml to 200 μg/ml, or 200 μg/ml trypsin (Sigma) as described (Bunikis and Barbour, 1999). Protease-treated cells were analyzed by epifluorescence microscopy using a Nikon Eclipse E600 microscope fitted with a Texas Red HYQ filter block. Digital images were acquired with a QImaging Micropublisher Digital CCD color camera (epifluorescence micrographs), Epson Perfection 2450 Photo scanner or Fuji LAS-4000 Luminescent Image Analyzer (immunoblots) and processed using Adobe Photoshop CS for Macintosh. Densitometry on Western blots or Coomassie-stained gels was done using ImageJ version 1.33u for Macintosh (NIH). Measurements were normalized to a FlaB loading control.

Membrane and Protein Fractionations

Membrane fractionation of Borrelia was performed as described (Skare et al., 1995; Schulze and Zückert, 2006). Briefly, early exponential phase B. burgdorferi cells were washed in 1x PBS containing 0.1% BSA, resuspended and incubated under vigorous shaking for 2 hrs in 25 mM citrate buffer, pH 3.2, containing 0.1% BSA. Outer membrane vesicles (OMVs) and protoplasmic cylinder (PCs) were fractionated by ultracentrifugation in a discontinuous gradient of 56, 42, and 25 % (wt/wt) sucrose in citrate buffer using a Beckman L8-80M centrifuge, SW28 rotor and 25x89 mm Ultra-Clear ultracentrifuge tubes. Fractions were washed and resuspended in 1x PBS containing 1mM PMSF.

Lipoprotein Sequence Analysis

Peptide sequences of 127 B. burgdorferi B31 lipoproteins (Setubal et al., 2006) were used for sequence comparisons. LogoBar (Perez-Bercoff et al., 2006) was used to graph consensus peptide sequences.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIH grant R01 AI063261 to W.R.Z. and a KUMC Biomedical Research Training grant to R.J.S. The authors are grateful to Joe Lutkenhaus, Kee-Jun Kim, Bill Picking, Mark Fisher, Cathy Lawson, Todd Holyoak and the members of the Zückert laboratory for inspiring discussions. We also thank Kee-Jun Kim, Patrick Viollier, Alan Barbour, Patricia Rosa, Laura Katona and Ben Luft for reagents.

References

- Babb K, McAlister JD, Miller JC, Stevenson B. Molecular characterization of Borrelia burgdorferi erp promoter/operator elements. J Bacteriol. 2004;186:2745–2756. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.9.2745-2756.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbour AG. Isolation and cultivation of Lyme disease spirochetes. Yale J Biol Med. 1984;57:521–525. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbour AG, Hayes SF, Heiland RA, Schrumpf ME, Tessier SL. A Borrelia-specific monoclonal antibody binds to a flagellar epitope. Infect Immun. 1986;52:549–554. doi: 10.1128/iai.52.2.549-554.1986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbour AG, Tessier SL, Hayes SF. Variation in a major surface protein of Lyme disease spirochetes. Infect Immun. 1984;45:94–100. doi: 10.1128/iai.45.1.94-100.1984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbour AG, Tessier SL, Todd WJ. Lyme disease spirochetes and ixodid tick spirochetes share a common surface antigenic determinant defined by a monoclonal antibody. Infect Immun. 1983;41:795–804. doi: 10.1128/iai.41.2.795-804.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bergström S, Bundoc VG, Barbour AG. Molecular analysis of linear plasmid-encoded major surface proteins, OspA and OspB, of the Lyme disease spirochaete Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol Microbiol. 1989;3:479–486. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1989.tb00194.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bono JL, Tilly K, Stevenson B, Hogan D, Rosa P. Oligopeptide permease in Borrelia burgdorferi: putative peptide-binding components encoded by both chromosomal and plasmid loci. Microbiology. 1998;144:1033–1044. doi: 10.1099/00221287-144-4-1033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bos MP, Robert V, Tommassen J. Biogenesis of the gram-negative bacterial outer membrane. Annu Rev Microbiol. 2007;61:191–214. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.61.080706.093245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brady GP, Sharp KA. Entropy in protein folding and in protein-protein interactions. Curr Opin Struct Biol. 1997;7:215–221. doi: 10.1016/s0959-440x(97)80028-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bunikis J, Barbour AG. Access of antibody or trypsin to an integral outer membrane protein (P66) of Borrelia burgdorferi is hindered by Osp lipoproteins. Infect Immun. 1999;67:2874–2883. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.6.2874-2883.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell RE, Tour O, Palmer AE, Steinbach PA, Baird GS, Zacharias DA, Tsien RY. A monomeric red fluorescent protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:7877–7882. doi: 10.1073/pnas.082243699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Casjens S, Palmer N, van Vugt R, Huang WM, Stevenson B, Rosa P, Lathigra R, Sutton G, Peterson J, Dodson RJ, Haft D, Hickey E, Gwinn M, White O, Fraser CM. A bacterial genome in flux: the twelve linear and nine circular extrachromosomal DNAs in an infectious isolate of the Lyme disease spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol Microbiol. 2000;35:490–516. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2000.01698.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chakrabartty A, Schellman JA, Baldwin RL. Large differences in the helix propensities of alanine and glycine. Nature. 1991;351:586–588. doi: 10.1038/351586a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clantin B, Hodak H, Willery E, Locht C, Jacob-Dubuisson F, Villeret V. The crystal structure of filamentous hemagglutinin secretion domain and its implications for the two-partner secretion pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:6194–6199. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400291101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cordes FS, Roversi P, Kraiczy P, Simon MM, Brade V, Jahraus O, Wallis R, Skerka C, Zipfel PF, Wallich R, Lea SM. A novel fold for the factor H-binding protein BbCRASP-1 of Borrelia burgdorferi. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2005;12:276–277. doi: 10.1038/nsmb902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deka RK, Brautigam CA, Yang XF, Blevins JS, Machius M, Tomchick DR, Norgard MV. The PnrA (Tp0319; TmpC) lipoprotein represents a new family of bacterial purine nucleoside receptor encoded within an ATP-binding cassette (ABC)-like operon in Treponema pallidum. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:8072–8081. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M511405200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Economou A, Christie PJ, Fernandez RC, Palmer T, Plano GV, Pugsley AP. Secretion by numbers: Protein traffic in prokaryotes. Mol Microbiol. 2006;62:308–319. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05377.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eicken C, Sharma V, Klabunde T, Owens RT, Pikas DS, Hook M, Sacchettini JC. Crystal structure of Lyme disease antigen outer surface protein C from Borrelia burgdorferi. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:10010–10015. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M010062200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elias AF, Stewart PE, Grimm D, Caimano MJ, Eggers CH, Tilly K, Bono JL, Akins DR, Radolf JD, Schwan TG, Rosa P. Clonal polymorphism of Borrelia burgdorferi strain B31 MI: implications for mutagenesis in an infectious strain background. Infect Immun. 2002;70:2139–2150. doi: 10.1128/IAI.70.4.2139-2150.2002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francetic O, Pugsley AP. Towards the identification of type II secretion signals in a nonacylated variant of pullulanase from Klebsiella oxytoca. J Bacteriol. 2005;187:7045–7055. doi: 10.1128/JB.187.20.7045-7055.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fraser CM, Casjens S, Huang WM, Sutton GG, Clayton R, Lathigra R, White O, Ketchum KA, Dodson R, Hickey EK, Gwinn M, Dougherty B, Tomb JF, Fleischmann RD, Richardson D, Peterson J, Kerlavage AR, Quackenbush J, Salzberg S, Hanson M, van Vugt R, Palmer N, Adams MD, Gocayne J, Weidman J, Utterback T, Watthey L, McDonald L, Artiach P, Bowman C, Garland S, Fuji C, Cotton MD, Horst K, Roberts K, Hatch B, Smith HO, Venter JC. Genomic sequence of a Lyme disease spirochaete, Borrelia burgdorferi. Nature. 1997;390:580–586. doi: 10.1038/37551. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerstein M, Lesk AM, Chothia C. Structural mechanisms for domain movements in proteins. Biochemistry. 1994;33:6739–6749. doi: 10.1021/bi00188a001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Giuseppe PO, Neves FO, Nascimento AL, Guimaraes BG. The leptospiral antigen Lp49 is a two-domain protein with putative protein binding function. J Struct Biol. 2008;163:53–60. doi: 10.1016/j.jsb.2008.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Golovanov AP, Balasingham S, Tzitzilonis C, Goult BT, Lian LY, Homberset H, Tonjum T, Derrick JP. The solution structure of a domain from the Neisseria meningitidis lipoprotein PilP reveals a new beta-sandwich fold. J Mol Biol. 2006;364:186–195. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2006.08.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gupta RS. Protein phylogenies and signature sequences: A reappraisal of evolutionary relationships among archaebacteria, eubacteria, and eukaryotes. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 1998;62:1435–1491. doi: 10.1128/mmbr.62.4.1435-1491.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haake DA. Spirochaetal lipoproteins and pathogenesis. Microbiology. 2000;146:1491–1504. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-7-1491. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hantke K, Braun V. [The structure of covalent binding of lipid to protein in the murein-lipoprotein of the outer membrane of Escherichia coli (author's transl)] Hoppe Seylers Z Physiol Chem. 1973;354:813–815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins MK, Bokma E, Koronakis E, Hughes C, Koronakis V. Structure of the periplasmic component of a bacterial drug efflux pump. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:9994–9999. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0400375101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang X, Yang X, Luft BJ, Koide S. NMR identification of epitopes of Lyme disease antigen OspA to monoclonal antibodies. J Mol Biol. 1998;281:61–67. doi: 10.1006/jmbi.1998.1930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jewett MW, Byram R, Bestor A, Tilly K, Lawrence K, Burtnick MN, Gherardini F, Rosa PA. Genetic basis for retention of a critical virulence plasmid of Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol Microbiol. 2007;66:975–990. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05969.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jong WS, ten Hagen-Jongman CM, den Blaauwen T, Slotboom DJ, Tame JR, Wickstrom D, de Gier JW, Otto BR, Luirink J. Limited tolerance towards folded elements during secretion of the autotransporter Hbp. Mol Microbiol. 2007;63:1524–1536. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05605.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Junker M, Schuster CC, McDonnell AV, Sorg KA, Finn MC, Berger B, Clark PL. Pertactin beta-helix folding mechanism suggests common themes for the secretion and folding of autotransporter proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:4918–4923. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507923103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katona LI, Beck G, Habicht GS. Purification and immunological characterization of a major low-molecular-weight lipoprotein from Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 1992;60:4995–5003. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.12.4995-5003.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kempf JG, Jung JY, Ragain C, Sampson NS, Loria JP. Dynamic requirements for a functional protein hinge. J Mol Biol. 2007;368:131–149. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2007.01.074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumaran D, Eswaramoorthy S, Luft BJ, Koide S, Dunn JJ, Lawson CL, Swaminathan S. Crystal structure of outer surface protein C (OspC) from the Lyme disease spirochete, Borrelia burgdorferi. EMBO J. 2001;20:971–978. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.5.971. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Labandeira-Rey M, Skare JT. Decreased infectivity in Borrelia burgdorferi strain B31 is associated with loss of linear plasmid 25 or 28-1. Infect Immun. 2001;69:446–455. doi: 10.1128/IAI.69.1.446-455.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahdenne P, Porcella SF, Hagman KE, Akins DR, Popova TG, Cox DL, Katona LI, Radolf JD, Norgard MV. Molecular characterization of a 6.6-kilodalton Borrelia burgdorferi outer membrane-associated lipoprotein (lp6.6) which appears to be downregulated during mammalian infection. Infect Immun. 1997;65:412–421. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.2.412-421.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lario PI, Pfuetzner RA, Frey EA, Creagh L, Haynes C, Maurelli AT, Strynadka NC. Structure and biochemical analysis of a secretin pilot protein. EMBO J. 2005;24:1111–1121. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence MC, Pilling PA, Epa VC, Berry AM, Ogunniyi AD, Paton JC. The crystal structure of pneumococcal surface antigen PsaA reveals a metal-binding site and a novel structure for a putative ABC-type binding protein. Structure. 1998;6:1553–1561. doi: 10.1016/s0969-2126(98)00153-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lawson CL, Yung BH, Barbour AG, Zückert WR. Crystal structure of neurotropism-associated variable surface protein 1 (Vsp1) of Borrelia turicatae. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:4522–4530. doi: 10.1128/JB.00028-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lenhart TR, Akins DR. Borrelia burgdorferi locus BB0795 encodes a BamA orthologue required for growth and efficient localization of outer membrane proteins. Mol Microbiol. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2009.07015.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewenza S, Vidal-Ingigliardi D, Pugsley AP. Direct visualization of red fluorescent lipoproteins indicates conservation of the membrane sorting rules in the family Enterobacteriaceae. J Bacteriol. 2006;188:3516–3524. doi: 10.1128/JB.188.10.3516-3524.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H, Dunn JJ, Luft BJ, Lawson CL. Crystal structure of Lyme disease antigen outer surface protein A complexed with an Fab. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1997;94:3584–3589. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.8.3584. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masuda K, Matsuyama S, Tokuda H. Elucidation of the function of lipoprotein-sorting signals that determine membrane localization. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:7390–7395. doi: 10.1073/pnas.112085599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikolosko J, Bobyk K, Zgurskaya HI, Ghosh P. Conformational flexibility in the multidrug efflux system protein AcrA. Structure. 2006;14:577–587. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2005.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakagawa T, Shimizu H, Link K, Koide A, Koide S, Tamura A. Calorimetric dissection of thermal unfolding of OspA, a predominantly beta-sheet protein containing a single-layer beta-sheet. J Mol Biol. 2002;323:751–762. doi: 10.1016/s0022-2836(02)00974-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita S, Matsuyama S, Tokuda H. Lipoprotein trafficking in Escherichia coli. Arch Microbiol. 2004;182:1–6. doi: 10.1007/s00203-004-0682-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Narita SI, Tokuda H. Amino acids at positions 3 and 4 determine the membrane specificity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa lipoproteins. J Biol Chem. 2007 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M611839200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pal U, Li X, Wang T, Montgomery RR, Ramamoorthi N, Desilva AM, Bao F, Yang X, Pypaert M, Pradhan D, Kantor FS, Telford S, Anderson JF, Fikrig E. TROSPA, an Ixodes scapularis receptor for Borrelia burgdorferi. Cell. 2004;119:457–468. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.10.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng K, Radivojac P, Vucetic S, Dunker AK, Obradovic Z. Length-dependent prediction of protein intrinsic disorder. BMC Bioinformatics. 2006;7:208. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-7-208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez-Bercoff A, Koch J, Burglin TR. LogoBar: bar graph visualization of protein logos with gaps. Bioinformatics. 2006;22:112–114. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/bti761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pham TN, Koide S. NMR studies of Borrelia burgdorferi OspA, a 28 kDa protein containing a single-layer beta-sheet. J Biomol NMR. 1998;11:407–414. doi: 10.1023/a:1008246908142. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pomorski T, Menon AK. Lipid flippases and their biological functions. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2006;63:2908–2921. doi: 10.1007/s00018-006-6167-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Potterton E, McNicholas S, Krissinel E, Cowtan K, Noble M. The CCP4 molecular-graphics project. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr. 2002;58:1955–1957. doi: 10.1107/s0907444902015391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pugsley AP. The complete general secretory pathway in gram-negative bacteria. Microbiol Rev. 1993;57:50–108. doi: 10.1128/mr.57.1.50-108.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Purser JE, Norris SJ. Correlation between plasmid content and infectivity in Borrelia burgdorferi. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2000;97:13865–13870. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.25.13865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Randall LL, Hardy SJ. SecB, one small chaperone in the complex milieu of the cell. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2002;59:1617–1623. doi: 10.1007/PL00012488. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodgers L, Gamez A, Riek R, Ghosh P. The type III secretion chaperone SycE promotes a localized disorder-to-order transition in the natively unfolded effector YopE. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:20857–20863. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M802339200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sadziene A, Barbour AG, Rosa PA, Thomas DD. An OspB mutant of Borrelia burgdorferi has reduced invasiveness in vitro and reduced infectivity in vivo. Infect Immun. 1993;61:3590–3596. doi: 10.1128/iai.61.9.3590-3596.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuels DS. Electrotransformation of the spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. Methods Mol Biol. 1995;47:253–259. doi: 10.1385/0-89603-310-4:253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sankaran K, Wu HC. Lipid modification of bacterial prolipoprotein. Transfer of diacylglyceryl moiety from phosphatidylglycerol. J Biol Chem. 1994;269:19701–19706. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sauvonnet N, Pugsley AP. Identification of two regions of Klebsiella oxytoca pullulanase that together are capable of promoting beta-lactamase secretion by the general secretory pathway. Mol Microbiol. 1996;22:1–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.1996.tb02650.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiebel E, Schwarz H, Braun V. Subcellular location and unique secretion of the hemolysin of Serratia marcescens. J Biol Chem. 1989;264:16311–16320. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulze RJ, Zückert WR. Borrelia burgdorferi lipoproteins are secreted to the outer surface by default. Mol Microbiol. 2006;59:1473–1484. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05039.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seiffer D, Klein JR, Plapp R. EnvC, a new lipoprotein of the cytoplasmic membrane of Escherichia coli. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1993;107:175–178. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1993.tb06026.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setubal JC, Reis M, Matsunaga J, Haake DA. Lipoprotein computational prediction in spirochaetal genomes. Microbiology. 2006;152:113–121. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.28317-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seydel A, Gounon P, Pugsley AP. Testing the ‘+2 rule’ for lipoprotein sorting in the Escherichia coli cell envelope with a new genetic selection. Mol Microbiol. 1999;34:810–821. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1999.01647.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silva-Herzog E, Ferracci F, Jackson MW, Joseph SS, Plano GV. Membrane localization and topology of the Yersinia pestis YscJ lipoprotein. Microbiology. 2008;154:593–607. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.2007/013045-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Skare JT, Shang ES, Foley DM, Blanco DR, Champion CI, Mirzabekov T, Sokolov Y, Kagan BL, Miller JN, Lovett MA. Virulent strain associated outer membrane proteins of Borrelia burgdorferi. J Clin Invest. 1995;96:2380–2392. doi: 10.1172/JCI118295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Steere AC, Sikand VK, Meurice F, Parenti DL, Fikrig E, Schoen RT, Nowakowski J, Schmid CH, Laukamp S, Buscarino C, Krause DS. Vaccination against Lyme disease with recombinant Borrelia burgdorferi outer-surface lipoprotein A with adjuvant. Lyme Disease Vaccine Study Group. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:209–215. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807233390401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stewart PE, Thalken R, Bono JL, Rosa P. Isolation of a circular plasmid region sufficient for autonomous replication and transformation of infectious Borrelia burgdorferi. Mol Microbiol. 2001;39:714–721. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2001.02256.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sulzenbacher G, Canaan S, Bordat Y, Neyrolles O, Stadthagen G, Roig-Zamboni V, Rauzier J, Maurin D, Laval F, Daffe M, Cambillau C, Gicquel B, Bourne Y, Jackson M. LppX is a lipoprotein required for the translocation of phthiocerol dimycocerosates to the surface of Mycobacterium tuberculosis. EMBO J. 2006;25:1436–1444. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7601048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeda K, Miyatake H, Yokota N, Matsuyama S, Tokuda H, Miki K. Crystal structures of bacterial lipoprotein localization factors, LolA and LolB. EMBO J. 2003;22:3199–3209. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terada M, Kuroda T, Matsuyama SI, Tokuda H. Lipoprotein sorting signals evaluated as the LolA-dependent release of lipoproteins from the cytoplasmic membrane of Escherichia coli. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:47690–47694. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109307200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Ulsen P, van Alphen L, ten Hove J, Fransen F, van der Ley P, Tommassen J. A Neisserial autotransporter NalP modulating the processing of other autotransporters. Mol Microbiol. 2003;50:1017–1030. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2003.03773.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- von Heijne G. The structure of signal peptides from bacterial lipoproteins. Protein Eng. 1989;2:531–534. doi: 10.1093/protein/2.7.531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whetstine CR, Slusser JG, Zückert WR. Development of a single-plasmid-based regulatable gene expression system for Borrelia burgdorferi. Appl Environ Microbiol. 2009;75:6553–6558. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02825-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu T, McCandlish AC, Gronenberg LS, Chng SS, Silhavy TJ, Kahne D. Identification of a protein complex that assembles lipopolysaccharide in the outer membrane of Escherichia coli. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:11754–11759. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0604744103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamaguchi K, Yu F, Inouye M. A single amino acid determinant of the membrane localization of lipoproteins in E. coli. Cell. 1988;53:423–432. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(88)90162-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarbrough D, Wachter RM, Kallio K, Matz MV, Remington SJ. Refined crystal structure of DsRed, a red fluorescent protein from coral, at 2.0-Å resolution. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2001;98:462–467. doi: 10.1073/pnas.98.2.462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zückert WR. Laboratory maintenance of Borrelia burgdorferi. Curr Protoc Microbiol. 2007 doi: 10.1002/9780471729259.mc12c01s4. Chapter 12: Unit 12C.1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zückert WR, Bergström S. Structure, Function and Biogenesis of the Borrelia Cell Envelope. In: Samuels DS, Radolf JD, editors. Structure, Function and Biogenesis of the Borrelia Cell Envelope. Caister Academic Press; Norwich, UK: 2010. pp. 139–166. [Google Scholar]

- Zückert WR, Kerentseva TA, Lawson CL, Barbour AG. Structural conservation of neurotropism-associated VspA within the variable Borrelia Vsp-OspC lipoprotein family. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:457–463. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M008449200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zückert WR, Lloyd JE, Stewart PE, Rosa PA, Barbour AG. Cross-species surface display of functional spirochetal lipoproteins by recombinant Borrelia burgdorferi. Infect Immun. 2004;72:1463–1469. doi: 10.1128/IAI.72.3.1463-1469.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zückert WR, Meyer J, Barbour AG. Comparative analysis and immunological characterization of the Borrelia Bdr protein family. Infect Immun. 1999;67:3257–3266. doi: 10.1128/iai.67.7.3257-3266.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.