Abstract

Epididymal function depends on androgen signaling through the androgen receptor (AR), although most of the direct AR target genes in epididymis remain unknown. Here we globally mapped the AR binding regions in mouse caput epididymis in which AR is highly expressed. Chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing indicated that AR bound selectively to 19,377 DNA regions, the majority of which were intergenic and intronic. Motif analysis showed that 94% of the AR binding regions harbored consensus androgen response elements enriched with multiple binding motifs that included nuclear factor 1 and activator protein 2 sites consistent with combinatorial regulation. Unexpectedly, AR binding regions showed limited conservation across species, regardless of whether the metric for conservation was based on local sequence similarity or the presence of consensus androgen response elements. Further analysis suggested the AR target genes are involved in diverse biological themes that include lipid metabolism and sperm maturation. Potential novel mechanisms of AR regulation were revealed at individual genes such as cysteine-rich secretory protein 1. The composite studies provide new insights into AR regulation under physiological conditions and a global resource of AR binding sites in a normal androgen-responsive tissue.

The identification of genome-wide androgen receptor binding sites in mouse caput epididymis, suggest novel patterns of transcriptional regulation mediated by androgen receptor.

Androgens regulate male phenotype development during embryogenesis and male sexual maturation at puberty, and maintain male reproductive function and behavior in the adult. The effects of androgen are mediated through the androgen receptor (AR), a ligand-inducible nuclear receptor that regulates the expression of target genes by binding to androgen response element (ARE) DNA (1,2,3).

Microarray expression analysis has identified androgen-dependent genes in target tissues and prostate cancer cells (4,5,6,7). However, this approach does not distinguish direct and indirect actions of AR. More recently techniques to identify genomic binding sites of transcription factors have been developed that include chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) followed by hybridization of the immunoprecipitated DNA pool to a tiling array or end sequencing of immunoprecipitated DNA fragments (ChIP-seq) (8). These methods have identified genome-wide AR binding sites in prostate cancer cell lines and primary human skeletal muscle myoblasts (9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17); however thus far, in vivo global mapping of AR binding sites was not reported in normal androgen target tissues.

The epididymis is an androgen-responsive organ responsible for sperm maturation and storage (18). The epididymis expresses high levels of AR (www.nursa.org/10.1621/datasets.02001) (19), and essentially all physiological aspects of epididymal function are androgen regulated. This includes epididymis growth and differentiation, ion and small molecule transport, and the synthesis and secretion of proteins required for sperm maturation (20). Morphological and histological criteria subdivide the epididymis into the initial segment, caput, corpus, and cauda (Fig. 1A). The proximal epididymis that includes the initial segment and caput expresses high levels of AR (21) and proteins required for sperm maturation (22,23). The initial segment is more dependent on testicular factors than the caput epididymis. Restoration of circulating testosterone levels reverses castration-induced regressive changes in caput epididymis but not in the initial segment (20). Testicular factors other than androgens contribute to initial segment-enriched gene expression, whereas caput-enriched genes are more completely regulated by androgen (23). Based on the abundance and functional importance of AR in caput epididymis, genome-wide binding site mapping of AR was performed using ChIP-seq.

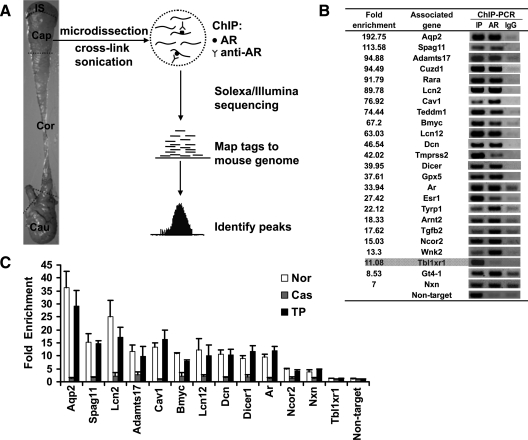

Figure 1.

Overview of the ChIP-seq approach and validation of AR-binding sites identified by ChIP-seq. A, Tissue dissection boundaries are indicated for adult mouse epididymis. IS, Initial segment; Cap, caput; Cor, corpus; Cau, cauda. Caput (Cap) epididymides were pooled from six mice and ChIP-seq was performed using an AR antibody. Tags that uniquely aligned to the reference mouse genome were used to define the peaks. B, Input sample (IP) and ChIP samples of anti-AR antibody (AR) or normal IgG (IgG) were analyzed by PCR to confirm ChIP-seq results at many of the target loci. A subset indicated by fold enrichment and gene name is shown. All peaks were enriched except the peak associated with the Tbl1xr1 gene. Enrichment is not observed at the nontarget region, i.e. the ligand dependent nuclear receptor corepressor-like (Lcorl) intronic region. All primers are listed in Supplemental Table 8. C, Androgen dependence of AR binding to ChIP-seq peaks. ChIP samples were prepared from epididymides of normal mice (Nor), mice castrated for 3 d (Cas), and mice castrated for 3 d but supplemented with testosterone propionate (TP) for an additional 2 d. ChIPed DNA was measured by quantitative PCR using primers spanning various potential AR-binding regions. The Lcorl gene intronic region was used as a nontarget control. Fold enrichment was calculated using IgG enrichment as a control. The data are presented as the mean ± sd of two replicates.

We report whole-genome identification of AR binding sites under physiological conditions in intact chromatin of mouse caput epididymis. The studies reveal novel AR binding sites and insights into AR-mediated gene regulation in vivo.

Results

Genome-wide identification of AR-binding regions in mouse caput epididymis

ChIP was performed on caput epididymis from adult male mice (Fig. 1A). After evaluating ChIP efficiency by ChIP-quantitative PCR (qPCR) (Supplemental Fig. 1), ChIPed DNA was submitted for Illumina sequencing (Illumina, San Diego, CA) (Fig. 1A). Global analysis of ChIP-seq data identified 19377 peaks with a P ≤ 1e−19.56 [corresponding to false discovery rate (FDR) ≤0.01%] (Supplemental Table 1). To validate the ChIP-seq results, randomly selected peaks with various fold enrichment were confirmed by individual ChIP combined with conventional PCR (ChIP-PCR) or qPCR (ChIP-qPCR). A total of 94.7% of peaks was validated in caput epididymis (Fig. 1B and Supplemental Table 2). Given that AR recruitment to target DNA is androgen dependent, we assessed the androgen dependence of AR binding to ChIP-seq peaks. AR binding was abolished after castration and recovered following androgen supplementation (Fig. 1C) that indicated AR occupancy was androgen dependent. AR binding regions were associated with histone H3 K9/K14 acetylation, a marker of functional regulatory elements that includes enhancers and promoters (12,24), and exhibited androgen-dependent transcriptional activity (Supplemental Fig. 2). The results suggested the ChIP-seq data are reliable and the deduced peaks represent bona fide in vivo AR targets.

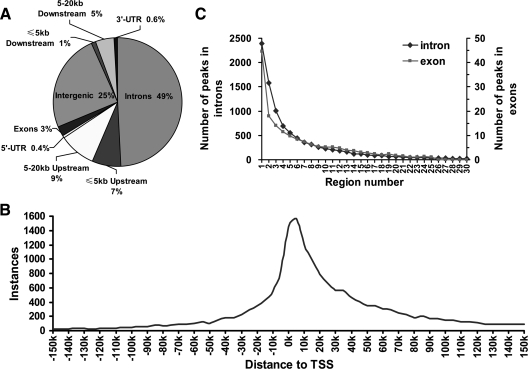

Correlation of high-confidence AR binding regions with the University of California, Santa Cruz (UCSC) mm9-annotated genes indicated 25% of the AR binding sites were located within intergenic regions greater than 20 kb from an annotated gene, with 75% of the AR binding sites positioned within 20 kb upstream of the transcription start site (TSS) and 20 kb downstream of the 3′-end of the gene (Fig. 2A). Of the identified peaks, 1% overlapped with the 5′-untranslated region (UTR) or 3′-UTR, 3% were in exon regions, 16% were within 20 kb upstream of the TSS, 6% within 20 kb downstream of the 3′-end, and 49% within introns (Fig. 2A).

Figure 2.

Distribution of AR-binding sites across the mouse genome. A, Pie diagram showing the percentage of AR-binding sites relative to intron, intergenic, upstream, downstream, and UTRs. The majority of AR-binding sites were in introns (49%) or intergenic regions greater than 20 kb from the TSS (25%) with 7% in the 5-kb upstream proximal promoter regions. B, Frequency of AR-binding sites by position from the nearest TSSs. Peak summits were used to calculate distance. C, AR-binding events in gene introns or exons. The graph displays the total number of AR-binding sites (y-axis) located within intron and exon regions of genes (x-axis). The UCSC known genes were used as reference (A–C). Note the sharp decline in AR-binding sites with distance from the TSS.

Further analysis of the relative distribution of AR binding sites resulted in a sharp peak at the TSS with a large percentage of binding sites within 20 kb of the TSS (Fig. 2B). Most of the intron AR binding sites were closer to the target gene TSS, with 2391 binding regions within the first intron (Fig. 2C). Exonic AR binding regions typically occurred at the beginning of the coding region (Fig. 2C).

A total of 8190 reference sequence genes (National Center for Biotechnology Information reference sequences; Bethesda, MD) were defined as peak-associated genes in which the AR peak was within 20 kb upstream of TSS to 20 kb downstream of transcriptional end site. These encoded a diverse group of proteins that included transcription factors, cytoskeletal components, epididymal secretory proteins, epigenetic modifiers, and signaling molecules (Supplemental Fig. 3). Some peak-associated genes showed androgen-dependent expression in mouse caput epididymis (Supplemental Fig. 4). Sixty-three microRNAs were associated with AR binding regions that included Mmu-mir-21 and Mmu-mir-26b (Supplemental Fig. 3).

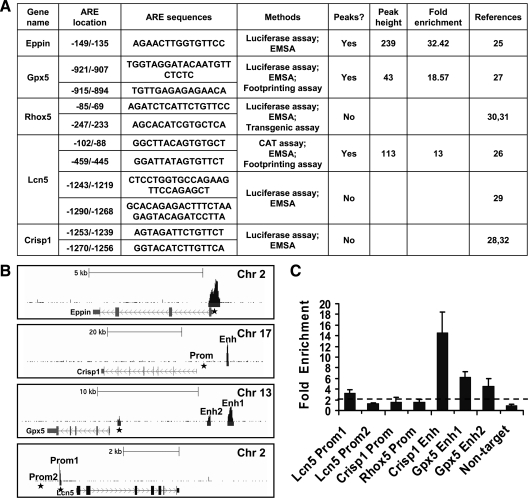

Peaks were associated with known AR-target genes and binding sites

Several AR-binding sites located within the promoter regions of genes regulated by androgen in epididymis have been reported (25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32). All of these binding events were demonstrated using in vitro assays that included EMSAs, deoxyribonuclease I footprinting and luciferase assays. Previous studies focused on the proximal promoter region of target genes with less emphasis on other regions. Our ChIP-seq analysis allowed for the verification of reported AR-binding sites and the identification of novel AR binding sites associated with AR target genes.

A group of 11 known AREs at six genomic loci was compiled from the literature and correlated with the AR-binding sites identified by ChIP-seq (Fig. 3A). The AR-binding peaks overlapped in three of six loci that included the promoter regions for epididymal protease inhibitor Eppin (25), Lcn5 (retinoic acid binding protein) (26), and Gpx5 (27) (Fig. 3B). The sites associated with Gpx5 and Eppin were used as quality controls for ChIP experiments before solexa sequencing, as shown in Supplemental Fig. 1. The Lcn5 proximal promoter site was enriched about 3-fold, consistent with its weak peak signal (Fig. 3C). The distal promoter site of Lcn5 (29), the promoter site of cysteine-rich secretory protein 1(Crisp1) (28,30,32), and the promoter site of Rhox5 (Pem) (30,31) did not contain AR-binding peaks (Fig. 3B).

Figure 3.

Characterization of AR-binding sites associated with known AR target genes. A, Table of 11 previously characterized AREs in five target genes showing peak presence or absence, peak height, and fold enrichment. B, Screen shots of the UCSC genome browser mm9 showing ChIP peaks around AR target genes Eppin, Crisp1, Gpx5, and Lcn5. The figure was generated by uploading to the UCSC genome browser two files containing unique ChIP-seq tags in the WIG format and peak coordinates in the BED format. The upper black track shows the tag density, and the gray bars below the track represent enriched peaks. The AR target genes are shown at the bottom and the black arrow indicates the gene orientation. Sequence positions and other generic UCSC annotations were removed for clarity. *, Locations of previously identified AR-binding sites. Prom, Promoter; Enh, enhancer. C, Validation of known and novel AR-binding sites associated with AR target genes Lcn5, Crisp1, Rhox5, and Gpx5 by ChIP-qPCR using anti-AR antibody. Enrichment folds were calculated using IgG enrichment as a control. The data are presented as the mean ± sd of three replicates. Primers are listed in Supplemental Table 8.

To exclude the possibility that peaks overlapping the binding sites may have been missed by ChIP-seq, we performed independent ChIP-qPCR. As shown in Fig. 3C, none of these previously identified AR binding regions were enriched, indicating little or no AR binding. This suggested that some AR-binding sites previously identified in vitro were not bound by AR in the adult mouse caput epididymis in vivo. In contrast, some previously uncharacterized binding sites associated with these AR target genes were identified in the ChIP-seq data set. These included two sites located −9.8 and −12 kb upstream of GPX5 TSS and a site −8.4 kb upstream of Crisp1 TSS (Fig. 3B). AR occupancy of the three sites was verified by ChIP-qPCR (Fig. 3C).

A comparison of 4175 recently identified AR target genes in human PC3-AR cells (13) with mouse epididymis targets in the present study identified 1440 genes in common. The peak profiles of some of these common AR target genes not characterized previously in epididymis are shown in Supplemental Fig. 5. Androgen stimulation of Greb1, a critical factor that affects prostate cell proliferation, is mediated by AR binding to a promoter ARE (33). Greb1 was also stimulated by androgen in mouse epididymis (Supplemental Fig. 4) with nine AR-binding sites identified, one in the promoter and eight in introns (Supplemental Fig. 5). Ndrg1 is an intracellular cell growth inhibitor that has four distal peaks upstream of the TSS (Supplemental Fig. 5). Ndrg1was reported to be up-regulated by androgen in human LNCaP cells (34), whereas its ortholog was down-regulated in mouse epididymis (Supplemental Fig. 4), suggesting species- and/or tissue-specific regulation by androgen.

Identification of AREs

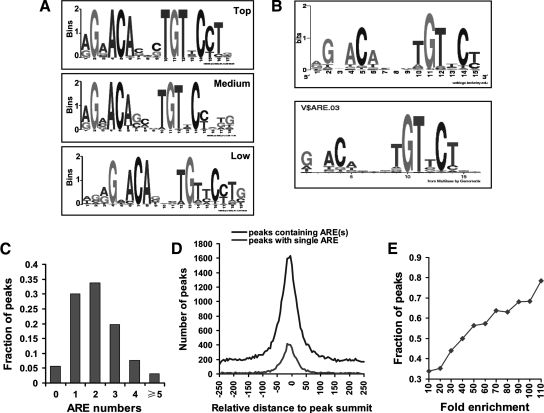

We assessed whether AR-binding regions were enriched in consensus AREs.

MEME (multiple expectation maximization for motif elicitation, http://meme.sdsc.edu/meme4_3_0/cgi-bin/meme.cgi) was applied initially to search the 250 enriched AR-binding regions. The ARE motif (A/G)GAACANNNTGTTC(T/C), similar to the established consensus canonical ARE (35), was most represented, regardless of the enrichment levels for the input peaks (Fig. 4A).

Figure 4.

Consensus AREs within AR-binding regions. A, De novo search for enriched motifs within the AR-binding peaks using MEME software demonstrated the presence of consensus AREs. Two hundred fifty peaks with top (>50-fold), medium (20- to 50-fold) and low (<20-fold) enrichment were analyzed. B, Scanning approach using RegionMiner analysis identified consensus AREs overrepresented within all AR-binding peaks. The identified ARE (top panel) was similar to the ARE presented in the MatBase database (bottom panel). C, Number of consensus AREs within 500-bp region centered on peak summit. D, Distance in base pairs from ARE midpoint to peak summit in AR binding peaks. The upper black curve represents peaks containing one or more AREs, and the lower gray curve for peaks with a single ARE. E, Fraction of peaks with at least one ARE within 50 bp of the summit at different enrichment folds.

Genomatix RegionMiner release 3.2 (http://www.genomatix.de/index.html) was used to map potential AR-binding sites among the 170 vertebrate transcription factor matrix families represented in the MatBase matrix library. As expected, the ARE motif (A/G)GAACANNNTGTTC(T/C), similar to the established ARE in the MatBase database (Fig. 4B), ranked highest in fold enrichment and Z-score. Ninety-four percent (18,298 of 19,377) of the AR-binding peaks contained AREs. Of these, 30% contained one ARE and 64% contained two or more AREs (Fig. 4C). It was not clear whether the tags mapped to such loci corresponded to one or more binding events. The presence of multiple AREs within a short region is likely a strategy to enhance AR function in caput epididymis. Motif analysis of AR binding peaks without AREs using MEME showed noncanonical or half-site-like AREs enriched in 38.3% (413 of 1,079) of peaks (Supplemental Fig. 6).

To localize AREs within the inferred binding regions, the frequency distribution of the distance was plotted between the middle of the ARE and the peak summit. As shown in Fig. 4D, AREs were preferentially associated with the peak in a Gaussian-like distribution. For all peaks containing ARE(s), 75% of the AREs were within 100 bp of the peak summit. When only those binding regions containing a single ARE were considered, the resolution increased to 75% of the AREs within 50 bp of the peak summit. A positive correlation was observed between the fold enrichment and fraction of the peaks containing at least one ARE within 50 bp of the summit (Fig. 4E). This suggested that AR bound most strongly to sites encompassing consensus AREs. A greater proportion of AREs within 50 bp of the peak summit demonstrated the superior spatial resolution of the ChIP-seq data that facilitated downstream functional analysis.

Other transcription factor-binding sites associated with AREs

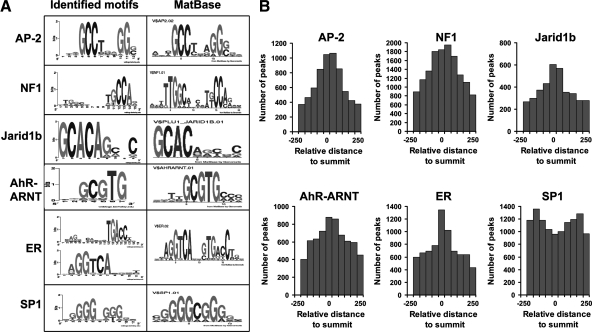

To analyze the network of transcription factors that modulate AR function in caput epididymis, all AR-binding regions identified by ChIP-seq were analyzed for transcription factor DNA-binding sites using RegionMiner. In addition to AREs, 12 potential transcription factor-binding motifs were highly overrepresented within the top 1000 AR binding peaks (Supplemental Table 3). These motifs closely resembled motifs represented in the MatBase database (Fig. 5A). Calculation of the relative positional distribution of enriched motifs within the AR-binding region indicated most of the motifs that included activator protein 2 (AP-2), nuclear factor 1 (NF1), aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR)-aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator (ARNT), Jarid1b, and estrogen receptor (ER) were near the summit region of the peaks. In contrast, the trans-acting transcription factor 1 (SP1) binding sites were less biased toward the peak and were more evenly distributed (Fig. 5B). The cooccurrence of AR and other transcription factor-binding motifs is consistent with cotranscriptional AR target gene regulation.

Figure 5.

Other transcription factor-binding motifs are enriched in the AR-binding regions. A, RegionMiner was used to search for enriched transcription factor-binding motifs in AR-binding regions as described in Materials and Methods. Motif logos were generated by Weblogo (http://weblogo.berkeley.edu/) and shown for AP-2, NF1, Jarid1b, AhR-ARNT, ER, and SP1-binding sites (left panel). The most similar motif from the MatBase database is included (right panel). A complete list of enriched motifs is provided in Supplemental Table 3. B, Distribution of AP-2, NF1, Jarid1b, AhR-ARNT, ER, and SP1 motifs within AR-binding peaks relative to the peak summit (represented as 0).

Among the most common motifs, AP-2 (3.3-fold, Z-score of 25.26) and NF1 (2.0-fold, Z-score of 19.32) (Supplemental Table 3) DNA binding sites were associated with 24 and 45% of the AREs, respectively. To further validate combinatorial interactions between AR, AP-2 and NF1, overrepresentation analysis on modules, i.e. pairs of transcription factor binding sites within 10–50 bp (middle to middle) was performed using RegionMiner in which the AR was the designated partner. As expected, ARE-ARE (7.5-fold, Z-score of 295.03), ARE-AP-2 (9.5-fold, Z-score of 177.6), and ARE-NF1 (5.4-fold, Z-score of 175.65) motif combinations were enriched.

We next sought to establish which of the transcription factors that potentially bind the motifs function in mouse epididymis and focused initially on transcription factors abundant in mouse caput epididymis. Gene expression profiles of mouse epididymis showed that two members of the AP-2 family, AP-2α and AP-2β, and all members of the NF1 family (Nfia, Nfib, Nfic, and Nfix) are relatively highly expressed in mouse caput epididymis (18). To determine which of these transcription factors is recruited to the AR-binding regions, ChIP-qPCR was performed using antibodies for AP-2α, AP-2β, and NF1 isoforms. Primers were selected to amplify the 15 validated AR-binding regions. As shown in Supplemental Fig. 7, AP-2α, AP-2β, and NF1 were 2-fold or greater associated with 73% (11 of 15), 73% (11 of 15), and 67% (10 of 15) of the detected AR-binding sites, respectively, providing evidence that AP-2 and NF1 act together with AR in androgen-dependent gene regulation.

Evolutionary conservation of AR-binding regions

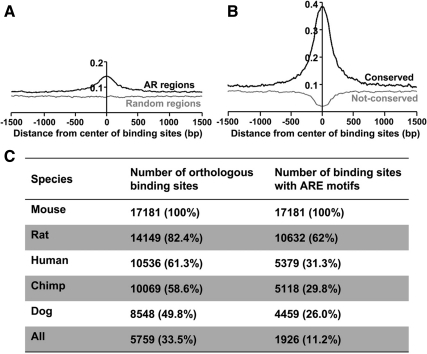

Regulatory sites might be expected to be conserved in orthologous regions across species. Wang et al. (11) identified 90 AR-binding sites on chromosomes 21 and 22 in LNCaP cells and performed a comparative analysis between the genomes of eight vertebrate species (human, chimp, dog, mouse, rat, chicken, fugu, and zebrafish). The results showed a conservation at the center of the AR-binding sites (supplement in Ref. 11). Recently Wyce et al. (15) identified AR-binding sites in primary human muscle cells, and they performed sequence conservation analysis across species. The results showed a high level of conservation within the binding regions but not in surrounding regions. We assessed the evolutionary conservation of the AR-binding sites in mouse epididymis across species. Overall conservation was measured by the cis-regulatory element annotation system (CEAS; http://ceas.cbi.pku.edu.cn/) using the base-by-base conservation score (phastCons score) that ranges from 0 (nonconserved) to 1 (highly conserved). As shown in Fig. 6A, a conservation signal of the ChIP regions was evident compared with the genomic background.

Figure 6.

Evolutionary conservation of AR-binding sites. Conservation profiles of AR-binding sites were analyzed by CEAS. CEAS uses phastCons conservation scores from UCSC Genome Bioinformatics based on multiz alignment of human, chimpanzee, mouse, rat, dog, chicken, fugu, and zebrafish genomic DNA. The center of the AR-binding regions was designated as 0 and the distance from the center in base pairs. The y-axes represent the conservation scores. A, Conservation profile of total AR-binding sites is depicted by the black line. The gray line denotes randomly selected genomic regions. B, The black line depicts the extent of conservation in 33.7% (6,521 of 19,377) of the AR-binding regions bearing conserved elements. The gray line shows the extent of conservation of the remaining 66.3% (12,856 of 19,377) of AR-binding regions without conserved elements. The results show that most of the conservation signal is driven by a minority of the binding sites. C, Conservation of ARE sequences among mammalian species. The 200-bp AR binding regions (around peak summits) containing AREs were analyzed to search orthologous regions and conserved ARE motifs in genomes of different mammalian species using RegionMiner. The results showed that most AREs are not conserved among mammals.

To determine the actual proportion of conserved binding regions, we examined the presence of phastCons-conserved elements in AR-binding regions. Surprisingly, only 33.7% (6,521 of 19,377) of all AR-binding regions overlapped with conserved elements and were responsible for most of the conservation signal. When equally sized random regions were analyzed, only 17.3% overlapped with conserved elements. When the conservation value was plotted by CEAS, a sharp peak in the binding site was observed for conserved regions (33.7%) and the conservation score was up to about 0.4, whereas the value for nonconserved regions (66.3%) was less than background (Fig. 6B).

We retrieved the data of Wang et al. (11) and performed the conservation analysis using the same analytical approaches. As predicted, only 42.2% (38 of 90) of the binding regions were conserved and responsible for the conservation signal observed (Supplemental Fig. 8A). We also analyzed further the data of Wyce et al. (15) and found that only 30% of binding regions were conserved. To further verify our findings, the same analysis was performed on the AR ChIP-seq data in PC3-AR cells (13). In this case, only 25.4% (1681 of 6629) of the binding regions were highly conserved and contributed to the global conservation signal (Supplemental Fig. 8B).

Conservation analysis was also performed on AR binding regions and ARE motifs between mammals that are evolutionarily close. Only 33.5% (5,759 of 17,181) of AR-binding regions that harbored ARE motifs were conserved across multiple mammalian species (rat, human, chimpanzee, and dog) (Fig. 6C). Moreover, only 11.2% of regions had conserved ARE motifs across mammalian species (Fig. 6C). Taken together, the sequence and motif conservation results indicated that the majority of AR-binding sites identified in this study were poorly conserved across multiple mammalian species.

Peak-associated genes potentially modulate diverse biological processes and pathways

To analyze further the biological themes potentially regulated by AR, peak-associated genes were retrieved for Gene Ontology (GO) analysis using the GSEABase. These genes were mainly involved in metabolism, signal transduction, biological regulation, localization, development, transport, biopolymer modification, and cell adhesion (Supplemental Fig. 9, A and B). Among these, metabolism was the largest group, suggesting AR-mediated gene regulation is central to biological function in the adult epididymis.

Pathway analysis on peak-associated genes was performed using the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG). Nine enriched KEGG pathways associated with cell junction and signal transduction are presented in Supplemental Fig. 9C. Two representative pathways, the tight junction and MAPK pathway, were shown in Supplemental Figs. 10 and 11, respectively.

Correlation of global gene expression with global AR DNA binding

To correlate further AR binding with androgen-dependent gene regulation, gene expression profiles in mouse caput epididymis were determined in response to dihydrotestosterone from data reported earlier (5). To avoid bias toward a small number of differentially expressed gene transcripts regulated 2-fold or greater by dihydrotestosterone, transcripts differentially expressed by at least 1.5-fold were included. We found 352 transcripts positively regulated by androgen and 437 transcripts negatively regulated by androgen. When combined with AR ChIP-seq data within 20 kb of binding peaks, 199 positively and 191 negatively regulated genes were associated with 481 (2.5%) and 411 (2.1%) AR-binding peaks, respectively. Other genes that changed expression but were not bound by AR may be indirect AR target genes or regulated via long-range regulation (binding outside our defined window). More than 90% of the AR binding sites were associated with genes not significantly regulated by androgen.

GO analysis was also performed on AR target genes regulated by androgen. Up-regulated genes were mostly enriched for lipid metabolic processes such as lipid metabolism (GO 0044255), lipid biosynthesis (GO 0008610), and sterol metabolism (GO 0016125), whereas down-regulated genes were mainly involved in development and cell regulation (Supplemental Table 4).

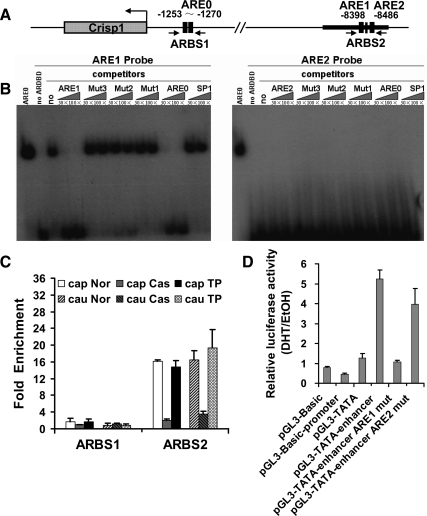

Characterization of AR-binding sites for Crisp1

Crisp1 is a well-studied cysteine-rich secretory protein regulated by androgen in epididymis (36). As shown in Fig. 3, a previously reported AR-binding site (ARBS)-1 contained two tandem AREs (32) that were not occupied by AR in our study. However, we identified a novel binding site designated ARBS2. In ARBS2, two potential AREs, ARE1 and ARE2, were predicted by RegionMiner (Fig. 7A). Only ARE1, which was closer to the peak summit, was bound by AR as demonstrated in the EMSA (Fig. 7B) and accounted for AR occupancy in the region in vivo. Crisp1 was more highly expressed in cauda than caput epididymis (18), and AR binding was also observed in the cauda epididymis. Additionally, AR binding was androgen dependent in the caput and cauda epididymis (Fig. 7C). Luciferase assays showed the Crisp1 promoter region lacked transcriptional enhancer activity, whereas the novel ARBS2 was strongly active. To confirm the enhancer characteristic of ARBS2 required the ARE, we mutated the two AREs and performed luciferase assays. Mutation of ARE1 abolished enhancer activity, whereas mutation of ARE2 had no effect (Fig. 7D).

Figure 7.

Characterization of a novel AR-binding region in Crisp1 gene. A, Schematic representation of potential AR-binding regions and AREs in the Crisp1 gene. Previously identified AREs (ARE0) and two newly identified AREs (ARE1 and ARE2) are shown. Primers were selected to amplify the potential ARBS. ARBS1 spans the ARE0, and ARBS2 spans ARE1 and ARE2. Primers are listed in Supplemental Table 8. B, AR-bound ARE1 but not ARE2 demonstrated by EMSAs. ARE0 served as a positive control. Control incubation performed in the absence of protein is presented in lane 2. Competitors are indicated above and amounts of competitors used are given in molar excess. Competitors include unlabeled AREs, mutant AREs, and a consensus DNA-binding site for SP1. Oligonucleotide sequences of probes and competitors are listed in Supplemental Table 9. C, Androgen-dependent AR binding to Crisp1 ARBS2 in caput and cauda epididymis. ChIP samples of epididymis from normal mice (Nor), mice castrated for 3 d (Cas) and mice castrated for 3 d but supplemented with testosterone propionate (TP) for an additional 2 d were analyzed by qPCR using primers spanning ARBS1 and ARBS2. Fold enrichment was calculated using IgG enrichment as a control. The data are presented as the mean ± sd of two replicates. D, ARBS2 identified by ChIP-seq functions as an enhancer. Crisp1 promoter region (−2117 to −66) was subcloned into the pGL3-basic plasmid and the novel 500-bp ARBS2 (enhancer) or the corresponding mutants that contain mutated ARE1 (enhancer ARE1 mut) or ARE2 (enhancer ARE2 mut) were subcloned into pGL3-TATA plasmids. Plasmids were cotransfected with pcDNA3.1-AR into Hela cells, and luciferase activities were measured after treatment with ethanol or 100 nm dihydrotestosterone. The data are presented as the mean ± sd of three replicates. Primers are listed in Supplemental Table 10.

Discussion

Comprehensive identification of transcription factor binding sites across the genome provides a foundation for understanding gene regulatory dynamics. Here we present genome-wide ChIP-seq profiling of AR-binding sites in mature mouse caput epididymis. To our knowledge, this is the first study that approaches a genome-wide identification of AR-binding sites in a normal androgen target tissue. Compared with the previous genome-wide studies on AR-binding sites in prostate cancer cells and primary human muscle cells (10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17), our study showed some similarities in the distribution of binding sites relative to associated genes and also showed some novel features including: 1) a high incidence of consensus AREs in the AR-binding regions, 2) identification of novel enriched motifs such as AP-2 near AREs, 3) limited conservation of AR binding sites, and 4) epididymis-specific patterns of transcriptional regulation mediated by AR.

Using ChIP-seq, about 20,000 in vivo AR-binding sites were identified in adult mouse caput epididymis, the majority of which (75%) were distal to the promoter in intergenic and intronic regions consistent with studies on AR in prostate cancer cells and primary human muscle cells (9,10,11,15). Selected remote AR binding regions displayed histone H3 K9/K14 acetylation and transcriptional enhancer activity. They may interact with receptive promoters through looping to regulate gene expression, as suggested for the androgen-dependent genes TMPRSS2 (11) and prostate-specific antigen (PSA) (37). The correlation between AR-binding sites and androgen-dependent gene expression (5) suggested that a small minority of AR-associated genes are regulated by androgen. This result is in accordance with previous findings on AR (12,14) and other transcription factors (38).

The striking discordance between binding and androgen-regulated expression indicate that AR binding alone is not sufficient to drive altered expression of most of the genes. Other factors such as promoter accessibility, chromatin remodeling, epigenetic modification, and the assistance of cooperating factors may be necessary for transcriptional regulation to occur. However, different time courses of androgen withdrawal and replacement might reveal androgen regulation of a larger number of AR associated genes in normal epididymis through the programmed expression of rate limiting factors involved in chromatin modification or transcription factor complex assembly.

Nonbiased motif scanning of in vivo AR-binding sites using RegionMiner identified a consensus ARE in 94% of the binding regions, with 64% containing two or more AREs. In contrast, the ChIP-seq data of Lin et al. (13) indicated 2.9% of AR binding sites contained a canonical ARE in prostate PC3-AR cells. Another AR ChIP-on-chip study in LNCaP cells showed 27% of AR promoter-binding regions contained consensus 15-bp AREs (14). Recently Wyce et al. (13) reported the genome-wide AR-binding sites in primary human muscle cells and found that 64% of binding sites contained AREs. We used the same analytical methods described in the publications Lin et al. (13) and Wyce et al. (13) to analyze our ChIP-seq data and found that 55 and 94% of binding sites contained AREs, respectively. To better compare these results, we extracted the above-mentioned data (binding regions of Lin et al. were resized to 500 bp) and searched for ARE motifs using RegionMiner. Our results showed that 50, 55, and 61% of AR binding regions contained consensus AREs, respectively. Recently Yu et al. used RegionMiner to search for AREs within AR-binding sites identified by ChIP-seq in LNCaP and VCaP cells and found that only 40% of AR-binding sites contained AREs (17). Although different methods and settings will cause the difference of ARE content, we conclude that ARE occurrences in AR-binding sites are much higher in this work than in previous studies in prostate cancer cells and primary human muscle cells.

This discordance may be attributed to many factors including: 1) tissue and/or species differences (mouse epididymis/human prostate cancer cells/primary human muscle cells), 2) antibody (monoclonal vs. polyclonal; epitopes; specificity), 3) in vivo physiological conditions vs. androgen treatment during in vitro cell culture (androgen concentration; the length of treatment), 4) the technical platforms (ChIP on chip vs. ChIP-seq; ChIP-seq sequencing depth), and 5) softwares/algorithms for peak calling. The detailed comparative information is shown in Supplemental Table 5.

Previous genome-wide studies have shown that AR binding regions identified in prostate cancer cells are enriched in binding motifs for multiple specific transcription factors. These include Forkhead box A1, octamer transcription factor-1, GATA2, v-ets erythroblastosis virus E26 oncogene homolog 1, NF1, and CCAAT/enhancer-binding proteinβ (11,12,14) and suggest cooperative interactions with AR. To extend our knowledge of transcription factors that collaborate with AR in mouse epididymis, we identified transcription factor DNA motifs associated with AR-binding regions identified by ChIP-seq. These included NF1 sites and several additional enriched motifs that were not identified in previous studies, including motifs for AP-2, ER, SP1, Jarid1b, and AhR-ARNT. To validate our results, we also performed motif analysis on AR-binding regions using CEAS which finds enriched TRANSFAC and JASPAR motifs in the ChIP regions. As expected, most of the enriched motifs identified by RegionMiner were confirmed by CEAS (Supplemental Table 6), supporting the reliability of our results.

Previous work has shown a coregulatory role for ER (39), SP1 (40), Jarid1b (41), and AhR-ARNT (42) in the transcription of individual AR target genes, but the unbiased identification of these binding motifs within AR-binding sites suggests a more general role for these transcription factors in AR transcription. Up to the current date, little is known about the role of AP-2 in AR-mediated transcription. Clues to the importance of AP-2 in AR regulation come from early work that demonstrated a weak interaction between AR and AP-2 in a high-throughput in vitro transcription factor interaction array screen (43). A prior study revealed synergistic interactions between AP-2 and activated glucocorticoid receptor in stimulating the Pnmt promoter activity (44). Our ChIP-qPCR results showed that AP-2 cooccupied some AR binding regions associated with activated or repressed AR-associated genes. All these results implied a potential role for AP-2 in modifying AR transcriptional activity in adult epididymis.

Conservation analysis showed that the majority of AR-binding regions were not conserved across species based on local sequence similarity or the presence of ARE motifs in the metric for conservation (Fig. 6 and Supplemental Fig. 7). Lin et al. (45) observed a similar lack of conservation profiles of ERα-binding regions identified by ChIP-on-chip or ChIP-PET, in support of species specificity of nuclear receptor binding. More recently, Schmidt et al. (46) identified species-specific, genome-wide binding sites of CCAAT/enhancer-binding protein α and hepatocyte nuclear factor 4α in liver among five vertebrate species using ChIP-seq. Our results are in line with these findings and suggest that AR functions in a species-specific manner. In support of this, the Crisp1 gene is important in rodent fertilization, but neither the AR-binding region nor gene is conserved between mouse and human.

Sperm maturation is androgen dependent, and in the androgen-deprived state, spermatozoa are immotile, lose their fertilizing capacity, and die (7). Our results indicate that many epididymis genes involved in sperm maturation are direct AR targets. For examples, Gpx5 is an antioxidant scavenger in the luminal compartment of mouse cauda epididymis that protected spermatozoa from oxidative injuries (47). Three AR-binding sites in the Gpx5 gene were identified by ChIP-seq, including one known promoter site and two novel distal binding sites located upstream of the TSS. Spag11, a caput epididymis-specific β-defensin, contains an AR-binding site in the proximal promoter (Supplemental Fig. 3E) and is up-regulated by androgen (Supplemental Fig. 4). Previous studies showed Spag11 is an initiation factor involved in sperm motility (48). Crisp1 is an androgen-regulated gene expressed in mouse epididymis, secreted into the lumen, and deposited on the epididymal sperm surface to influence capacitation and sperm-egg fusion (49). Our results suggested that a novel distal enhancer ARE, not the previously identified promoter ARE, mediates its androgenic regulation in epididymis in vivo. The Crisp1 promoter ARE showed stronger binding of AR in EMSAs (Fig. 7B), in which the latter indicated AR binds the ARE under certain in vitro conditions but not necessarily in vivo. AR occupancy of AREs in vivo showed specificity and selectivity among similar AREs in the genome possibly influenced by chromatin conformation, coregulator recruitment, and the cellular environment.

In conclusion, the present study provides a high-resolution map of global AR-binding sites that suggests a novel pattern of transcriptional regulation mediated by AR in epididymis in vivo. Our results contribute a perspective of AR action under physiological conditions in a normal androgen-dependent tissue and provide a step toward understanding temporal events in AR regulation of gene transcription. Our ChIP-seq data extend previous genome-wide data on AR-mediated gene regulation in prostate cancer cells and primary human muscle cells.

Materials and Methods

Animals

Male C57BL/6J mice were purchased from the Animal Center of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (Shanghai, China). Experiments were conducted according to a protocol approved by the Institute Animal Care Committee. The protocol conforms to internationally accepted guidelines for the humane care and use of laboratory animals.

Castration and androgen replacement

Adult 10-wk-old male C57BL/6J mice were castrated bilaterally under sodium pentobarbital anesthesia. The mice were divided into three groups (six mice/group), killed at different times after castration (0 and 3 d) or 2 d after two injections of testosterone propionate (2.5 mg/d) applied to the 3-d castrated mice. Caput epididymis from each group was pooled for ChIP or real-time RT-PCR. Testosterone content of pooled serum samples was measured by RIA.

ChIP

Adult male mice were killed and caput epididymis (Fig. 1A) excised and finely minced in PBS. After washing twice with PBS to remove epididymal lumen fluid and sperm, tissue was cross-linked in 1% formaldehyde at room temperature for 10 min. Tissue was pelleted, washed, and resuspended in PBS containing protease inhibitors and disaggregated on ice using 50 strokes of a glass homogenizer. Nuclei were collected and sonicated to yield 100–300 bp DNA fragments. Lysates were precleared with Protein A beads (sc-2001, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) at 4 C for 2 h before an overnight incubation with specific antibody or normal rabbit IgG. After a short incubation with Protein A beads, chromatin-antibody-bead complexes were washed twice with low salt buffer containing 0.1% sodium dodecyl sulfate, 1% Triton X-100, 2 mm EDTA, 20 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.1), and 0.15 m NaCl, twice with the same buffer except containing 0.5 m NaCl, twice with lithium chloride buffer containing 0.25 m LiCl, 1% Nonidet P-40, 1% deoxycholate, 1 mm EDTA, 10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.1), and three times with 1 mm EDTA and 10 mm Tris-HCl (pH 8.1). Chromatin was eluted with elution buffer containing 1% sodium dodecyl sulfate and 0.1 m NaHCO3 before reversal of the cross-links with Proteinase K (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) at 65 C for 4 h. DNA was purified using two rounds of phenol-chloroform extraction and ethanol precipitation and resolved in optimal volume of double-distilled H2O. The following Santa Cruz antibodies (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Santa Cruz, CA) were used for ChIP: anti-AR (H-280, sc-13062), anti-AP-2α (C-18, sc-184), anti-AP-2β (H-87, sc-8976), anti-NF1 (H-300, sc-5567), normal rabbit IgG (sc-2027), and anti-histone H3 acetylation-K9/K14 (06-599; Millipore, Bedford, MA).

ChIP-seq

ChIPs were performed with anti-AR and normal rabbit IgG as described above. Three ChIPs, corresponding to one batch of chromatin from caput epididymis of six normal adult mice, were pooled for a single Solexa sequencing, respectively. Anti-AR and IgG ChIPed DNA were separated by gel electrophoresis. DNA fragments in the 200- to 300-bp range were extracted, and a single adenosine was added using Klenow exo- (3′ and 5′ exo minus; Illumina). Illumina adaptors were added and DNA was subjected to 20 cycles of PCR according to the manufacturer’s instructions. We then purified DNA and performed cluster generation, and 35 cycles of sequencing were performed on the Illumina Genome Analyzer II following the manufacturer’s instructions. Sequencing data were processed through Genome Analyzer Pipeline Software (Illumina). Sequenced tags were aligned to the mouse genome using the Illumina Eland program with at most two mismatches. Eland multifiles were used in peak finding.

Peak finding

Solexa tags from AR ChIP and IgG control were coanalyzed to identify AR binding peaks with a relevant overrepresentation of tags in the AR ChIP sample compared with IgG control sample using MACS (model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq, http://liulab.dfci.harvard.edu/macs/) (50) with default parameters. To assess statistical significance, MACS estimates an FDR by swapping the AR and IgG data sets and repeating the peak calling process. We chose peaks with FDR of 0.01% or less (corresponding to a P value cutoff of 1e−19.56) for analysis. A total of 724 peaks with FDR = 0.02% but a P value ≤ 1e−19.56 were also included in our analysis. The InfoSnorkel Blue Elephant Definition file containing the peak chromosome coordinates could be viewed as a custom track in the UCSC genome browser. Peak regions identified by MACS were listed in Supplemental Table 7.

ChIP-PCR and ChIP-qPCR

ChIP assays were performed on mouse caput epididymis (n =3) as described above. Primers were designed to amplify a 90- to 150-bp region around the peak summit (binding location with highest tags pileup). DNA samples from ChIP preparations were analyzed by PCR (ChIP-PCR) or quantitative PCR (ChIP-qPCR) using SYBR Green master mix (TOYOBO, Osaka, Japan). Primers are listed in Supplemental Table 8.

Motif search

For the de novo motif search, peak-associated sequences that comprised the set of 200-bp sequences surrounding each peak summit were extracted. MEME (51) was applied using default parameters to identify statistically overrepresented motifs. The top, medium, and low 250 peaks were selected for MEME analysis.

The top 1000 enriched AR ChIP peaks were uniformly resized to 500 bp centered on the peak summit. These sequences were scanned for transcription factor motifs using 170 well-defined matrix families containing 727 weight matrices that represent binding site descriptions of 5747 transcription factors from MatBase Matrix Library 8.1 with RegionMiner subtask: overrepresented transcription factor binding sites or modules (Genomatix Software GmbH, http://www.genomatix.de/). The task searches for all relevant transcription factor binding sites (TFBSs) within the input sequences and generates statistics on TFBSs and modules (pairs of TFBSs within 10 to 50 bp distance) together with overrepresentation values and Z-scores. Overrepresentation values were based on the background of occurrences of the TFBS within the whole genomic sequence. A Z-score below −2 or above 2 was considered statistically significant and corresponded to a P value of about 0.05. Only matrix families with overrepresentation values of greater than 1.5 and a Z-score greater than 10 were considered. Sequence logos for specific transcription factor families were constructed using Weblogo (http://weblogo.berkeley.edu/).

All 500-bp AR-binding sites centered on the peak summits were applied to search AREs using RegionMiner. Those binding sites without AREs were reanalyzed by MEME to identify potential noncanonical AREs. The motif width was specified as 6–20.

Conservation analysis

The 200-bp AR-binding regions centered on the peak summit were used for conservation analyses. Conservation analyses were carried out as follows:

1. The conservation profile of all AR-binding regions was analyzed by CEAS. The genome coordinates of all 200-bp AR-binding regions were converted from the National Center for Biotechnology Information mm9 genome build to the mm8 genome build using the UCSC’s web lift-over tool. In the conversion, 26 peaks (<0.15% of the 19,377 peaks) were lost. The conservation profile of 19,351 AR-binding regions was analyzed using CEAS. CEAS uses phastCons conservation scores from UCSC Genome Bioinformatics, which is based on multiz alignment of human, chimp, mouse, rat, dog, chicken, fugu, and zebrafish genomic DNA. Multiz is a program developed for large-scale comparison of multiple sequences and it can be used to align highly rearranged or incompletely sequenced genomes. Background equally sized regions were selected randomly from the mouse genome and analyzed identically.

2. The proportion of binding sites associated with phastCons-conserved elements was calculated. PhastCons-conserved elements identify regions of the genome with high conservation scores. The most conserved track in the table phastConsElements30way was obtained through the UCSC Genome Browser. A binding region was considered to be sequence conserved if it overlapped with the phastConsElement. Conserved regions and the remaining unconserved regions were reanalyzed by CEAS.

3. ARE motif conservation was examined further across the mammalian species. All AR-binding regions were searched for consensus ARE motifs using RegionMiner subtask: overrepresented transcription factor binding sites or modules. Corresponding orthologous regions for binding regions with ARE motifs were identified in rat, human, chimpanzee, and dog using the RegionMiner subtask: search for orthologous regions in other species (Genomatix Software GmbH, http://www.genomatix.de/). Sequences for these orthologous regions were extracted and searched for consensus ARE motifs as described above.

GO and pathway analysis

The Refseq genes contained at least one peak within gene regions of −20 kb upstream of TSS to +20 kb downstream of the end of the gene were retrieved for GO and pathway analysis. GO analysis was performed by GSEABase package of BioConductor (http://www.bioconductor.org/) on the basis of biological process and molecular function. P values were computed using the hypergeometric distribution. Expression Analysis Systematic Explorer (EASE) (53) was used to analyze KEGG pathways. The EASE score, which is a modification of the Fisher exact test used with DAVID 2007 (Laboratory of Immunopathogenesis and Bioinformatics, Frederick, MD), was used to determine pathway significance. Only pathways with P ≤ 0.005 and gene count of 20 or greater were considered to be enriched.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

The GST-AR DNA-binding domain (DBD) fusion protein (GST-ARDBD) encoding human AR amino acids 520–644 that contains a DNA binding region identical to mouse AR (54) was expressed in Escherichia. coli and purified. EMSAs were performed as previously described (28). Briefly, 0.5 μg GST-ARDBD protein and γ-32P-labeled double-stranded oligonucleotides (2 × 105 cpm) were incubated for 25 min at 25 C in binding buffer (20 mm HEPES, pH 7.3; 0.2 mm EDTA; 1 mm dithiothreitol; 1 mm MgCl2; 50 mm NaCl; 0.5 g/liter Nonidet P-40; 10% glycerol). The DNA/protein complexes were separated on a prerun 6% nondenaturing polyacrylamide gel, followed by autoradiography. For competition experiments, GST-ARDBD fusion protein were incubated with unlabeled or mutant oligonucleotides for 20 min at 25 C before the addition of γ-32P-labeled oligonucleotide probes. The oligonucleotide sequences of probes and competitors are listed in Supplemental Table 9.

Luciferase reporter assay

Individual approximately 500-bp AR-binding regions around the peak summit were amplified and subcloned into PGL3-basic or PGL3-TATA luciferase reporter vectors. Hela cells (1.5 × 104/well) were grown in 96-well plates, cotransfected with 150 ng reporter constructs, 15 ng pRL-TK (Renilla luciferase), and 15 ng pcDNA3.1-AR expression vector coding for full-length human AR using Lipofectamine 2000 (Invitrogen). After overnight transfection, cells were treated with 100 nm dihydrotestosterone or ethanol vehicle for 24 h. Luciferase activity was measured using the dual-luciferase reporter assay (Promega, Madison, WI) and Mithras LB940 multimode microplate reader (Berthold, Bad Wildbad, Germany). Primer sequences are listed in Supplemental Table 10.

Real-time RT-PCR

Total RNA was isolated from caput epididymis of normal, castrated, and testosterone propionate-supplemented mice using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA was synthesized using 1 μg of total RNA and the first-strand cDNA synthesis kit (Toyobo) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time PCR was performed using SYBR Green master mix (Toyobo) with a Rotor-Gene 3000 machine (Corbett Research, Sydney, Australia). All real-time PCR reactions were performed in triplicate. Primer sequences can be found in Supplemental Table 11.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Yue Zhao for fruitful discussions and Dr. Piotr Mieczkowski for technical help in solexa sequencing. We are also grateful to Genminix Co. for technical assistance in Gene Ontology and pathway analysis.

Footnotes

This work was supported by grants from the National Basic Science Research and Development Project of China (2006CB504002 and 2006CB944002), the Chinese Academy of Sciences Knowledge Innovation Program (KSCX1-YW-R-54), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (30930053, 30770815, and 30730026), and National Institutes of Health Fogarty International Center of the United State4s (2 D43 TW000627-11 and -12, CFDA Grant 93,989).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to disclose.

First Published Online October 13, 2010

Abbreviations: AhR, Aryl hydrocarbon receptor; AP-2, activator protein 2; AR, androgen receptor; ARBS, AR-binding site; ARE, androgen response element; ARNT, aryl hydrocarbon receptor nuclear translocator; CEAS, cis-regulatory element annotation system; ChIP, chromatin immunoprecipitation; ChIP-PCR, ChIP combined with conventional PCR; ChIP-qPCR, ChIP combined with qPCR; ChIP-seq, end sequencing of chromatin immunoprecipitated DNA fragments; Crisp1, cysteine-rich secretory protein 1; DBD, DNA-binding domain; DHT, dihydrotestosterone; EASE, Expression Analysis Systematic Explorer; Eppin, epididymal protease inhibitor; ER, estrogen receptor; FDR, false discovery rate; GO, Gene Ontology; KEGG, Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes; MACS, model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq; MEME, multiple EM for motif elicitation; NF1, nuclear factor 1; phastCons score, base-by-base conservation score; qPCR, quantitative PCR; SP1, trans-acting transcription factor 1; TFBS, transcription factor-binding site; TSS, transcriptional start site; UCSC, University of California, Santa Cruz; UTR, untranslated region.

References

- Heinlein CA, Chang C 2002 Androgen receptor (AR) coregulators: an overview. Endocr Rev 23:175–200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heemers HV, Tindall DJ 2007 Androgen receptor (AR) coregulators: a diversity of functions converging on and regulating the AR transcriptional complex. Endocr Rev 28:778–808 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrão MT, Silva EJ, Avellar MC 2009 Androgens and the male reproductive tract: an overview of classical roles and current perspectives. Arq Bras Endocrinol Metab 53:934–945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dehm SM, Tindall DJ 2006 Molecular regulation of androgen action in prostate cancer. J Cell Biochem 99:333–344 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chauvin TR, Griswold MD 2004 Androgen-regulated genes in the murine epididymis. Biol Reprod 71:560–569 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang F, Wang Z 2003 Identification of androgen-responsive genes in the rat ventral prostate by complementary deoxyribonucleic acid subtraction and microarray. Endocrinology 144:1257–1265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robaire B, Seenundun S, Hamzeh M, Lamour SA 2007 Androgenic regulation of novel genes in the epididymis. Asian J Androl 9:545–553 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park PJ 2009 ChIP-seq: advantages and challenges of a maturing technology. Nat Rev 10:669–680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takayama K, Kaneshiro K, Tsutsumi S, Horie-Inoue K, Ikeda K, Urano T, Ijichi N, Ouchi Y, Shirahige K, Aburatani H, Inoue S 2007 Identification of novel androgen response genes in prostate cancer cells by coupling chromatin immunoprecipitation and genomic microarray analysis. Oncogene 26:4453–4463 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bolton EC, So AY, Chaivorapol C, Haqq CM, Li H, Yamamoto KR 2007 Cell- and gene-specific regulation of primary target genes by the androgen receptor. Genes Dev 21:2005–2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Li W, Liu XS, Carroll JS, Jänne OA, Keeton EK, Chinnaiyan AM, Pienta KJ, Brown M 2007 A hierarchical network of transcription factors governs androgen receptor-dependent prostate cancer growth. Mol Cell 27:380–392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia L, Berman BP, Jariwala U, Yan X, Cogan JP, Walters A, Chen T, Buchanan G, Frenkel B, Coetzee GA 2008 Genomic androgen receptor-occupied regions with different functions, defined by histone acetylation, coregulators and transcriptional capacity. PloS One 3:e3645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin B, Wang J, Hong X, Yan X, Hwang D, Cho JH, Yi D, Utleg AG, Fang X, Schones DE, Zhao K, Omenn GS, Hood L 2009 Integrated expression profiling and ChIP-seq analyses of the growth inhibition response program of the androgen receptor. PloS One 4:e6589 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Massie CE, Adryan B, Barbosa-Morais NL, Lynch AG, Tran MG, Neal DE, Mills IG 2007 New androgen receptor genomic targets show an interaction with the ETS1 transcription factor. EMBO Rep 8:871–878 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyce A, Bai Y, Nagpal S, Thompson CC 2010 Research resource: the androgen receptor modulates expression of genes with critical roles in muscle development and function. Mol Endocrinol 24:1665–1674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Li W, Zhang Y, Yuan X, Xu K, Yu J, Chen Z, Beroukhim R, Wang H, Lupien M, Wu T, Regan MM, Meyer CA, Carroll JS, Manrai AK, Jänne OA, Balk SP, Mehra R, Han B, Chinnaiyan AM, Rubin MA, True L, Fiorentino M, Fiore C, Loda M, Kantoff PW, Liu XS, Brown M 2009 Androgen receptor regulates a distinct transcription program in androgen-independent prostate cancer. Cell 138:245–256 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu J, Yu J, Mani RS, Cao Q, Brenner CJ, Cao X, Wang X, Wu L, Li J, Hu M, Gong Y, Cheng H, Laxman B, Vellaichamy A, Shankar S, Li Y, Dhanasekaran SM, Morey R, Barrette T, Lonigro RJ, Tomlins SA, Varambally S, Qin ZS, Chinnaiyan AM 2010 An integrated network of androgen receptor, polycomb, and TMPRSS2-ERG gene fusions in prostate cancer progression. Cancer Cell 17:443–454 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnston DS, Jelinsky SA, Bang HJ, DiCandeloro P, Wilson E, Kopf GS, Turner TT 2005 The mouse epididymal transcriptome: transcriptional profiling of segmental gene expression in the epididymis. Biol Reprod 73:404–413 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dankbar B, Brinkworth MH, Schlatt S, Weinbauer GF, Nieschlag E, Gromoll J 1995 Ubiquitous expression of the androgen receptor and testis-specific expression of the FSH receptor in the cynomolgus monkey (Macaca fascicularis) revealed by a ribonuclease protection assay. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 55:35–41 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ezer N, Robaire B 2002 Androgenic regulation of the structure and function of the epididymis. In: Robaire B, Hinton BT, eds. The epididymis: from molecules to clinical practice. New York: Kluwer Academic/Plenum Publishers; 297–316 [Google Scholar]

- Yamashita S 2004 Localization of estrogen and androgen receptors in male reproductive tissues of mice and rats. Anat Rec A Discov Mol Cell Evol Biol 279:768–778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vreeburg JT, Holland MK, Cornwall GA, Orgebin-Crist MC 1990 Secretion and transport of mouse epididymal proteins after injection of 35S-methionine. Biol Reprod 43:113–120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sipilä P, Pujianto DA, Shariatmadari R, Nikkilä J, Lehtoranta M, Huhtaniemi IT, Poutanen M 2006 Differential endocrine regulation of genes enriched in initial segment and distal caput of the mouse epididymis as revealed by genome-wide expression profiling. Biol Reprod 75:240–251 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heintzman ND, Stuart RK, Hon G, Fu Y, Ching CW, Hawkins RD, Barrera LO, Van Calcar S, Qu C, Ching KA, Wang W, Weng Z, Green RD, Crawford GE, Ren B 2007 Distinct and predictive chromatin signatures of transcriptional promoters and enhancers in the human genome. Nat Genet 39:311–318 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schauwaers K, De Gendt K, Saunders PT, Atanassova N, Haelens A, Callewaert L, Moehren U, Swinnen JV, Verhoeven G, Verrijdt G, Claessens F 2007 Loss of androgen receptor binding to selective androgen response elements causes a reproductive phenotype in a knockin mouse model. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:4961–4966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yu X, Suzuki K, Wang Y, Gupta A, Jin R, Orgebin-Crist MC, Matusik R 2006 The role of forkhead box A2 to restrict androgen-regulated gene expression of lipocalin 5 in the mouse epididymis. Mol Endocrinol 20:2418–2431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lareyre JJ, Claessens F, Rombauts W, Dufaure JP, Drevet JR 1997 Characterization of an androgen response element within the promoter of the epididymis-specific murine glutathione peroxidase 5 gene. Mol Cell Endocrinol 129:33–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haendler B, Schüttke I, Schleuning WD 2001 Androgen receptor signalling: comparative analysis of androgen response elements and implication of heat-shock protein 90 and 14-3-3eta. Mol Cell Endocrinol 173:63–73 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lareyre JJ, Reid K, Nelson C, Kasper S, Rennie PS, Orgebin-Crist MC, Matusik RJ 2000 Characterization of an androgen-specific response region within the 5` flanking region of the murine epididymal retinoic acid binding protein gene. Biol Reprod 63:1881–1892 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barbulescu K, Geserick C, Schüttke I, Schleuning WD, Haendler B 2001 New androgen response elements in the murine pem promoter mediate selective transactivation. Mol Endocrinol 15:1803–1816 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rao MK, Wayne CM, Wilkinson MF 2002 Pem homeobox gene regulatory sequences that direct androgen-dependent developmentally regulated gene expression in different subregions of the epididymis. J Biol Chem 277:48771–48778 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwidetzky U, Schleuning WD, Haendler B 1997 Isolation and characterization of the androgen-dependent mouse cysteine-rich secretory protein-1 (CRISP-1) gene. Biochem J 321:325–332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rae JM, Johnson MD, Cordero KE, Scheys JO, Larios JM, Gottardis MM, Pienta KJ, Lippman ME 2006 GREB1 is a novel androgen-regulated gene required for prostate cancer growth. Prostate 66:886–894 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ulrix W, Swinnen JV, Heyns W, Verhoeven G 1999 The differentiation-related gene 1, Drg1, is markedly upregulated by androgens in LNCaP prostatic adenocarcinoma cells. FEBS Lett 455:23–26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Claessens F, Verrijdt G, Schoenmakers E, Haelens A, Peeters B, Verhoeven G, Rombauts W 2001 Selective DNA binding by the androgen receptor as a mechanism for hormone-specific gene regulation. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 76:23–30 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haendler B, Habenicht UF, Schwidetzky U, Schüttke I, Schleuning WD 1997 Differential androgen regulation of the murine genes for cysteine-rich secretory proteins (CRISP). Eur J Biochem 250:440–446 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Q, Carroll JS, Brown M 2005 Spatial and temporal recruitment of androgen receptor and its coactivators involves chromosomal looping and polymerase tracking. Mol Cell 19:631–642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farnham PJ 2009 Insights from genomic profiling of transcription factors. Nat Rev 10:605–616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Panet-Raymond V, Gottlieb B, Beitel LK, Pinsky L, Trifiro MA 2000 Interactions between androgen and estrogen receptors and the effects on their transactivational properties. Mol Cell Endocrinol 167:139–150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu S, Jenster G, Epner DE 2000 Androgen induction of cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 gene: role of androgen receptor and transcription factor Sp1 complex. Mol Endocrinol 14:753–760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang Y, Zhu Z, Han G, Ye X, Xu B, Peng Z, Ma Y, Yu Y, Lin H, Chen AP, Chen CD 2007 JARID1B is a histone H3 lysine 4 demethylase up-regulated in prostate cancer. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 104:19226–19231 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohtake F, Baba A, Fujii-Kuriyama Y, Kato S 2008 Intrinsic AhR function underlies cross-talk of dioxins with sex hormone signalings. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 370:541–546 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mukhopadhyay NK, Ferdinand AS, Mukhopadhyay L, Cinar B, Lutchman M, Richie JP, Freeman MR, Liu BC 2006 Unraveling androgen receptor interactomes by an array-based method: discovery of proto-oncoprotein c-Rel as a negative regulator of androgen receptor. Exp Cell Res 312:3782–3795 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong DL, Siddall BJ, Ebert SN, Bell RA, Her S 1998 Phenylethanolamine N-methyltransferase gene expression: synergistic activation by Egr-1, AP-2 and the glucocorticoid receptor. Brain Res 61:154–161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin CY, Vega VB, Thomsen JS, Zhang T, Kong SL, Xie M, Chiu KP, Lipovich L, Barnett DH, Stossi F, Yeo A, George J, Kuznetsov VA, Lee YK, Charn TH, Palanisamy N, Miller LD, Cheung E, Katzenellenbogen BS, Ruan Y, Bourque G, Wei CL, Liu ET 2007 Whole-genome cartography of estrogen receptor α binding sites. PLoS Genet 3:e87 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt D, Wilson MD, Ballester B, Schwalie PC, Brown GD, Marshall A, Kutter C, Watt S, Martinez-Jimenez CP, Mackay S, Talianidis I, Flicek P, Odom DT 2010 Five-vertebrate ChIP-seq reveals the evolutionary dynamics of transcription factor binding. Science 328:1036–1040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chabory E, Damon C, Lenoir A, Kauselmann G, Kern H, Zevnik B, Garrel C, Saez F, Cadet R, Henry-Berger J, Schoor M, Gottwald U, Habenicht U, Drevet JR, Vernet P 2009 Epididymis seleno-independent glutathione peroxidase 5 maintains sperm DNA integrity in mice. J Clin Invest 119:2074–2085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou CX, Zhang YL, Xiao L, Zheng M, Leung KM, Chan MY, Lo PS, Tsang LL, Wong HY, Ho LS, Chung YW, Chan HC 2004 An epididymis-specific β-defensin is important for the initiation of sperm maturation. Nat Cell Biol 6:458–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts KP, Ensrud KM, Wooters JL, Nolan MA, Johnston DS, Hamilton DW 2006 Epididymal secreted protein Crisp-1 and sperm function. Mol Cell Endocrinol 250:122–127 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Liu T, Meyer CA, Eeckhoute J, Johnson DS, Bernstein BE, Nusbaum C, Myers RM, Brown M, Li W, Liu XS 2008 Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS). Genome Biol 9:R137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bailey TL, Williams N, Misleh C, Li WW 2006 MEME: discovering and analyzing DNA and protein sequence motifs. Nucleic Acids Res 34:W369–W373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji X, Li W, Song J, Wei L, Liu XS 2006 CEAS: cis-regulatory element annotation system. Nucleic Acids Res 34:W551–W54 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hosack DA, Dennis Jr G, Sherman BT, Lane HC, Lempicki RA 2003 Identifying biological themes within lists of genes with EASE. Genome Biol 4:R70 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charest NJ, Zhou ZX, Lubahn DB, Olsen KL, Wilson EM, French FS 1991 A frameshift mutation destabilizes androgen receptor messenger RNA in the Tfm mouse. Mol Endocrinol 5:573–581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.