Abstract

Estrogenic endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) constitute a diverse group of man-made chemicals and natural compounds derived from plants and microbial metabolism. Estrogen-like actions are mediated via the nuclear hormone receptor activity of estrogen receptor (ER)α and ERβ and rapid regulation of intracellular signaling cascades. Previous study defined cerebellar granule cell neurons as estrogen responsive and that granule cell precursor viability was developmentally sensitive to estrogens. In this study experiments using Western blot analysis and pharmacological approaches have characterized the receptor and signaling modes of action of selective and nonselective estrogen ligands in developing cerebellar granule cells. Estrogen treatments were found to briefly increase ERK1/2-phosphorylation and then cause prolonged depression of ERK1/2 activity. The sensitivity of granule cell precursors to estrogen-induced cell death was found to require the integrated activation of membrane and intracellular ER signaling pathways. The sensitivity of granule cells to selective and nonselective ER agonists and a variety of estrogenic and nonestrogenic EDCs was also examined. The ERβ selective agonist DPN, but not the ERα selective agonist 4,4′,4′-(4-propyl-[1H]-pyrazole-1,3,5-triyl) trisphenol or other ERα-specific ligands, stimulated cell death. Only EDCs with selective or nonselective ERβ activities like daidzein, equol, diethylstilbestrol, and bisphenol A were observed to induce E2-like neurotoxicity supporting the conclusion that estrogen sensitivity in granule cells is mediated via ERβ. The presented results also demonstrate the utility of estrogen sensitive developing granule cells as an in vitro assay for elucidating rapid estrogen-signaling mechanisms and to detect EDCs that act at ERβ to rapidly regulate intracellular signaling.

In estrogen-responsive granule cell neurons, only endocrine active compounds with estrogen receptor-β activity induced estradiol-like neurotoxicity, supporting the idea that the response of these cells to estradiol is mediated by estrogen receptor-β.

Estrogen-like endocrine disrupting chemicals (EDCs) are structurally diverse compounds that can be grouped into man-made chemicals (xenoestrogens) and natural compounds derived from plants (phytoestrogens) and microbial metabolism. Considering the numerous reports of EDC-mediated effects on estrogen sensitive systems, the impact of human exposure to environmental estrogens continues to be an area of major concern (1). The potential for harmful human health effects resulting from environmental estrogen EDC exposures is now supported by results from an epidemiologic study that shows association between higher urine BPA concentrations and diabetes, obesity, and cardiovascular disease (2). Resulting in much controversy, reproductive and chronic toxicological studies in some strains of rodents have failed to identify significant effects (3,4,5). Such conflicting evidence reinforces the critical need to understand the various mechanisms and modes of EDC action that estrogens have on various sensitive cell types, tissues, organs, and animal models.

Xenoestrogens are a varied group of synthetic compounds that include phenols, pesticides, polychlorinated biphenyls, phthalates, organic solvents, and pharmaceuticals. In exposed populations of wildlife some of these environmental chemical pollutants alter reproductive development. In some cases, these effects have caused decreased fertility and fecundity due to modification of secondary sex characteristics and sexual behaviors, improper gonad development, and altered ovulation and spermatogenesis (6,7,8).

Phytoestrogens are a similarly diverse group of compounds that possess estrogen-like properties. They are produced in plants or arise from the action of bacterial or fungal metabolism on plant precursor compounds. The three main classes of plant-derived phytoestrogens are the isoflavones, coumestans, and lignans. The soy isoflavones genistein and daidzein are found in soybeans and are regularly consumed in soy-containing food products including some infant formula. Potential harmful health effects resulting from elevated serum levels of genistein and daidzein in infants has been an area of concern for some time (9). Phytoestrogens are also consumed in dietary supplements as a natural form of estrogen replacement therapy to relieve undesirable symptoms during menopause and for their presumed protective actions against cardiovascular disease and osteoporosis (10). Coumestans are present in the sprouts of soy-beans, clover, and alfalfa, while lignans are found in flax seeds. Natural compounds with estrogen-like activity are also produced by molds. Mycoestrogens such as zearalenone are metabolic products of molds belonging to the genus Fusarium. Zearalenone is found in a number of cereal crops including maize, barley, oats, wheat, rice, and sorghum. Because it is heat-stable, zearalenone is present in bread and other baked goods (11). Many studies have demonstrated that phytoestrogens impact the growth of hormone-responsive cancer cells and can impact estrogen’s effects on reproductive function (12,13,14,15).

Estrogens mediate many of their effects through binding at estrogen receptors (ERs), members of the steroid/thyroid superfamily of nuclear receptors, and act to regulate the expression of estrogen responsive genes. However, the molecular mechanisms by which endogenous estrogens and especially EDCs act are not fully understood. Along with regulating estrogen-responsive gene expression, estrogens can rapidly affect a variety of signal transduction pathways. Little is known about the physiological impact and the signaling mechanisms of EDCs on rapid estrogen-induced signaling. Evidence from many different tissues and cell types including neurons suggests that there are multiple mechanisms through which estradiol acts to stimulate rapid intracellular signaling (16,17,18). Previous analysis of estrogen’s actions in developing and mature cerebellar granule cell neurons has delineated developing and mature granule cell neurons as estrogen responsive via rapid signaling and classical mechanisms with important differences in the physiological consequences of rapid E2-induced ERK signaling between immature and mature cerebellar neurons (19,20). In these sensitive neuronal precursors the rapid signaling actions of 17β-estradiol induce an ER-mediated oncotic mechanism of cell death (aka necrosis) resulting in the release of the intracellular enzyme lactate dehydrogenase (LDH). These actions of 17β-estradiol are specific and dependent on rapid activation of an intracellular signaling mechanism that requires plasmalemmal activation of extracellular-signal regulated kinase (ERK) signaling and the intracellular activation of protein phosphatase 2A (PP2A) activity which results in calpain activation and oncotic necrosis (19,20). We have previously used LDH release as a specific physiological marker in granule cell precursors to demonstrate the estrogen-like bioactivity of BPA that is released into the water samples from polycarbonate water bottles (21).

In this study we define the pharmacological profile of the signaling mechanisms that induce cell death in estrogen-sensitive granule cell precursors. The pharmacological profile of granule cell precursor cell death was found to be ERβ-driven and identical to previously characterized estrogen-mediated rapid signaling mechanisms in granule cell precursors. Further, the sensitivity of granule cell precursors to the toxic activities of selective and nonselective ER agonists and the endocrine disruptive profile of a broad representation of estrogenic and nonestrogenic endocrine disrupting chemicals was examined. Along with confirming the estrogen-like specificity of granule cell death and defining the mechanism of estrogen-like EDC activity in these immature neurons, the presented results demonstrate the usefulness of this model system for analysis of ERβ-mediated rapid signaling mechanisms, and that this model can be used as a screening tool for identifying EDCs with activities mediated through ERβ-specific mechanisms of action.

Materials and Methods

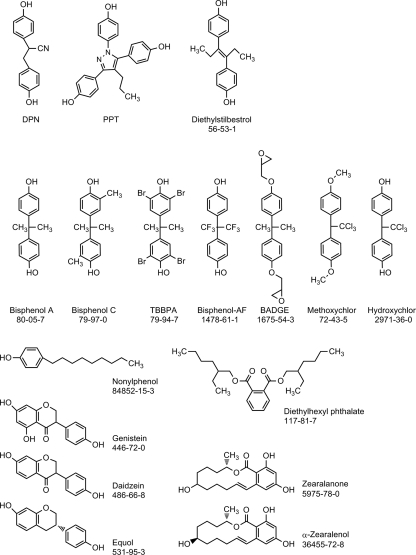

Reagents and solvents of the highest purity available were used. Chemicals purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO) included the following : bisphenol A (BPA), CAS 80-05-7, >99%, 23,965-8, lot Cl03105ES; 3,3′,5,5′ tetrabromo bisphenol A (TBBPA), CAS 79-94-7, 99.2%, 330396, lot 01510DE; 2,2′-bis(4-hydroxy-3-methylphenyl)propane (Bisphenol C), CAS 79-97-0, 99.9%, 423300, lot 00826LN; 4,4′-(hexafluoro-isopropylidene)diphenol (bisphenol-AF), CAS 1478-61-1, 99.2%, 257591, lot 09828LO; bisphenol A diglycidyl ether (BADGE), CAS 1675-54-3, 98%, D3415, lot 066k0053; diethylstilbestrol (DES), CAS 56-53-1, >99%, d-4628; nonylphenol, CAS 84852-15-3, 29085-8, lot 200030PI; diethylhexyl phthalate (DEHP), CAS 117-81-7, 99.5%, D201154, lot 066K0053; 2,2 bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-1,1,1-trichloroethane (hydroxychlor, HPTE), CAS 2971-36-0, 99.9%, 557145; 1,1,1-trichloroethane-2,2-bis(p-methoxyphenyl)ethane (methoxychlor), CAS 72-43-5, >95%, M-1501; (1,3,5 (10)-estratriene-3,17α-diol (17α-estradiol, 17α-E2), CAS 57-91-0; 4′7-dihydroxyisoflavone (daidzein), CAS 486-66-8, >99%, d-7802, lot 110k4096; 4′,5,7-trihydroxyisoflavone (genistein), CAS 44-7-0, >98%, G-6776, lot 41k4015; 2,4-dihydroxy-6-(10-hydroxy-6-oxoundecyl)benzoic acid (zearalenone), CAS 5975-78-0, Z-0167, lot 41k4058; α-zearalenol, CAS 36455-72–8; Z-0166, lot 120k4086; dimethyl sulfoxide, (≤99.7%, batch no. 00451HE). Steroids were purchased from Steraloids Newport RI: 1,3,5 (10)-estratriene-3,17β-diol (17β-estradiol, 17β-E2), cat E0959, batch B0356; 1,3,5 (10)-estratriene-3,17β-diol 17-hemisuccinate:BSA conjugate (17β-E2-BSA), E-8750, lot 111k4083 (molecular ratio of E2 to BSA was 35 with final concentrations based conjugate E2); 4-androsten-17β-ol-3-one (testosterone), lot# A6950, batch H508; 7, 4′-dihydroxyisoflavan [(+/−) equol], lot# 0306 was from Indofine (Hillsborough, NJ). 4,4′,4′-(4-propyl-[1H]-pyrazole-1,3,5-triyl) trisphenol (PPT), 2,3-bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-propionitrile diarylpropionitrile (DPN), tyrphostin AG 1478, okadaic acid, PP2, and LY294002 were from Tocris Cookson (Ellisville, MO). U0126 and H89 were from Promega (Madison, WI) and Calbiochem (San Diego, CA), respectively. The chemical structures of the selective ER ligands and EDC test compounds are shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1.

The chemical structures, trivial names, and CAS number of the selective ER ligands and endocrine disruptors analyzed.

Preparation of primary cerebellar neurons

Primary cerebellar cultures were prepared from neonatal female Sprague Dawley rats (Harlan, Indianapolis, IN; 16–17 grams) without enzymatic-treatment (19,22). All animal procedures were done in accordance with protocols approved by the University of Cincinnati Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee and followed National Institutes of Health guidelines. The resulting primary cerebellar cultures of maturing granule cell neurons were maintained free of serum and exogenous steroid hormones as previously described (19,22). Dissociated cerebellar cells were serially diluted in an appropriate volume of culture media and seeded at 2 × 105 granule cells per cm2 in 100 μl of media in 96-well culture plates (well area 0.31 cm2; TPP, Basel, Switzerland) that were coated with poly-L-lysine (100 μg/ml; Sigma, St. Louis, MO). Cultures were incubated in 5% CO2 at 37 C for 2–3 h before experimental exposures to allow granule cell attachment.

Treatments, pharmacological exposures, and cytotoxicity assay

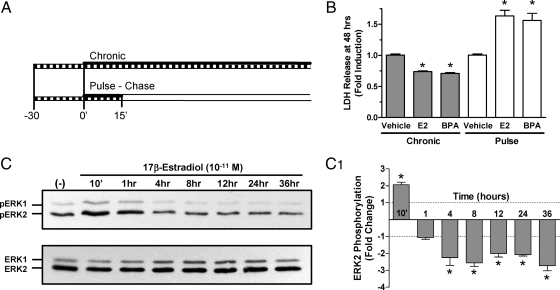

The two treatment protocols used were shown graphically in Fig. 2A. For continuous exposure (chronic) experiments, cultures were exposed to vehicle, 10−10 m E2, or 10−10 m BPA for 24 or 48 h with conditioned media collected at the end of each treatment. For the pulse-chase protocol, cultures were treated with compound containing culture media for 15 min, washed twice with compound free medium, and then incubated for 24 or 48 h in fresh compound-free culture medium (Fig. 2A). This 15-min pulsed exposure was previously shown to mimic rapid ERK-dependent non-transcriptional estrogenic mechanisms in developing granule cells treated with 17β-estradiol (19). During and after all treatments, cultures were maintained in 5% CO2 at 37 C in a humidified incubator.

Figure 2.

A, Schematic diagram of the experimental protocols used to analyze cell death in immature cerebellar granule cell cultures. Treatments are indicated with a solid black horizontal bar. Inhibitor exposures were initiated 30 min before drug treatment and were removed along with drug for the pulse-treated cultures as indicated with a hatched bar. The chronic treatment protocol is shown at the top, for those studies cultures were exposed to either compound or vehicle for the duration of the indicated exposure time. For the pulse-chase protocol the exposure to drug or vehicle was limited to 15 min as indicated by the solid black bar. Compound free media is indicated with an open bar. B, Comparative LDH release in response to chronic or pulsed treatment with E2 or BPA. Primary cerebellar cultures were chronically exposed to vehicle, 10−10 m E2, or 10−10 m BPA for 48 h or a 15-min pulsed treatment. At the 48 h time point conditioned media were collected and levels of LDH released into the media determined. Absorbance data are expressed as mean (±sem, n = 4). The level of significance for each treatment group was assessed with a one-way ANOVA with significance between values from vehicle and each treatment group indicated by * (P < 0.05). C, Western blot analysis of ERK1/2 phosphorylation in primary cultures of cerebellar granule cells exposed to 10−11 m E2 for up to 36 h. Shown are representative Western blots with exposure times indicated above each lane. The top panel illustrates the phosphorylation levels of ERK1/2, while the bottom panel shows total ERK1/2 levels. C1, Densitometric analyses of ERK-phosphorylation in response to extended exposure to E2. Results are expressed as the mean (±sem) fold change from three independent experiments. Fold change is defined as the value of pERK-IR normalized to total ERK-IR divided the value of vehicle treated control. The level of significance for each treatment group was assessed with a one-way ANOVA with significance (P < 0.05) as indicated by *.

Estrogen-induced LDH released into the media was determined as previously described (19,21,22). Briefly, the CytoTox 96 Non-Radioactive Cytotoxicity Assay (Promega; Madison, WI) was used to quantify LDH release. Visible wavelength absorbance data (492 nm) were collected using a microplate reader (Tecan SpectraFluor Plus; San Jose, CA) within one hour after stopping the colorimetric reactions. The absorbance values from experimental groups were normalized to absorbance values from vehicle control samples. Concentration effect curves for LDH release were determined from pulsed exposures to each compound over a typical concentration range from 10−12 to 10−6 m. Intermediate concentrations were one order of magnitude apart. Matching vehicle and media blank controls were included with each experiment. The selective signaling pathways inhibitors, their targets and treatment conditions are listed in Table 1. Cultures were exposed to the inhibitors 30 min before and during exposures (19,20).

Table 1.

Signaling cascade inhibitors

| Inhibitor (CAS RN) | Target | Conc. | Pretreatment period |

|---|---|---|---|

| U0126 (109511-58-2) | MEK1 (MAPKK) | 10 μm | 30 min |

| PP2 (172889-27-9) | Src-family kinase | 10 μm | 30 min |

| H89 (130964-39-5) | PKA | 10 μm | 30 min |

| AG1478 (175178-82-2) | EGFR kinase | 1 μm | 30 min |

| LY294002 (154447-36-6) | PI3K | 10 μm | 30 min |

| Okadaic acid (78111-17-8) | PP2A | 1 μm | 30 min |

Conc., Concentration.

Western blot analysis of ERK phosphorylation

All aspects of ERK-phosphorylation analysis including treatment of cultures, generation cerebellar cell lysates, SDS-PAGE, Western blotting, and densitometric analysis were done using standard protocols as previously described (19,20). Primary antibodies specific for phospho-(thr202/tyr204) p44/42 and MAPK (pERK1/2; #9101) were purchased from Cell Signaling Technology. (Beverly, MA) and used at 1:1000 dilutions.

Statistical analysis

Unless noted otherwise, all data presented are representative of at least three experiments or quantitative determinations and are reported as mean values ± sem. Statistical analysis was conducted using one-way ANOVA with post-test comparison between treatment groups using Tukey-Kramer multiple comparison test. A minimal level of statistical significance for differences in values was considered to be P < 0.05 and is indicated with an *. Data were analyzed with Excel (Microsoft) and GraphPad Prism version 5.0 (GraphPad Software Inc.).

Results

Initial experiments were performed to demonstrate that modification of the culturing and analysis systems to facilitate rapid analysis did not alter results (19,20). The two different treatment protocols used to assess the mechanism of estrogen action on sensitive granule cell precursors are shown graphically in Fig. 2A. Similar to previous studies, long-duration (chronic) exposures to 10−10 m E2 or BPA protected cerebellar granule cell precursors against cell death as indicated by a significant decrease in LDH release compared with vehicle controls at 48 h after treatment (19,20). In contrast, a 15-min pulsed-treatment with 10−10 m E2 or BPA followed by a chase treatment period with compound-free media resulted in a significant 1.77-fold increase in LDH release (Fig. 2B). This level of E2-induced LDH release was equivalent to 30% of the maximal response defined by LDH released from cultures treated with 0.2% Triton X-100 (not shown). These findings are comparable with previous results and support the conclusion that brief exposures to E2 induce specific rapid signaling mechanisms that result in an oncotic form of cell death in estrogen-sensitive granule cell precursors (19).

To understand more fully the impact of estrogens on the intracellular ERK-signaling cascade, the lowest concentration of E2 producing maximal effects (10−11 m) was used to investigate the long-term E2-mediated effects on ERK1/2 phosphorylation (Fig. 2C). Western blot analysis revealed that E2 stimulation of ERK1/2 was rapid and transient as previously defined with significant induction of ERK1/2 activation peaking 10 min after treatment initiation. However, phospho-ERK1/2 levels returned to baseline by 60 min of E2 exposure and were then observed to be significantly reduced below baseline at later times (Fig. 2C1). These results indicate that in response to low concentrations of E2 a rapid initial stimulation of ERK1/2 is followed by prolonged depressions in ERK1/2 activity that could govern the physiological responses observed at these later times.

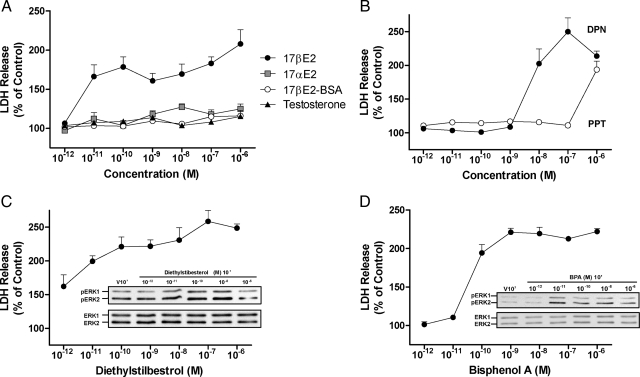

The concentration-response characteristics of different ER agonists and steroids were characterized and compared with the actions of E2. Using the pulse-chase protocol outlined in Fig. 1A, cultures of cerebellar granule cell precursors were treated with each concentration of agent and the amount of LDH released into the media was determined 24 h after treatment. The concentration response relationship for E2-induced LDH release was similar to the concentration response relationship for ERK-signaling (19). Likewise, exposure to 17α-estradiol, testosterone, and E2-BSA failed to elicit a detectable response over the same concentration range, suggesting that the LDH release response is specific to ER agonists and requires an intracellular-initiated mechanism (Fig. 3A).

Figure 3.

Dose-response analysis of cerebellar granule cell death for estrogens, testosterone, selective agonists, and the nonsteroidal xenoestrogens DES and BPA. A, Dose response analysis of LDH-release for cultures treated with different concentrations of 17β-estradiol, 17α-estradiol, membrane-impermeable 17β-estradiol-BSA, or testosterone ranging from 10−12 to 10−6 m. B, Dose response analysis of LDH-release for the ERα selective agonist PPT and the ERβ selective agonist DPN. C, Dose response analysis of LDH-release and Western analysis of rapid ERK phosphorylation for DES. D, Dose response analysis of LDH-release and rapid ERK phosphorylation for BPA. Levels of LDH release were determined 24 h after drug treatment using a colorimetric LDH assay and absorbance detection at 492 nm. At each concentration LDH release is reported as the mean percent of LDH-release relative to matched vehicle control cultures (±sem, n = 4).

To assess the roles of ERα and ERβ, concentration response experiments using the ERα selective agonist PPT and the ERβ selective agonist DPN were performed. Treatment with 10−8 to 10−6 m DPN increased LDH levels from 2 to 2.5-fold (Fig. 3B). By contrast PPT only induced a response at a high concentration (1 μm) where receptor selectivity is lost. These findings reveal that ER-induced LDH release is mediated by ERβ-dependent mechanisms.

The high affinity ligand of ERα and ERβ, diethylstilbestrol (Fig. 3C), and the lower affinity ER ligand BPA (Fig. 3D) were highly efficacious and potent stimulators of LDH release. Increased LDH release was significantly induced by all concentrations of DES examined including the lowest concentration (1 pm). Exposure to BPA significantly increased LDH release (2-fold) at all concentrations examined from 10−10 to 10−6 m. Both DES and BPA were more efficacious with regard to LDH release than E2. For DES and BPA, detectable increases in pERK signaling were also observed within similar concentration ranges (inset Fig. 3, C and D).

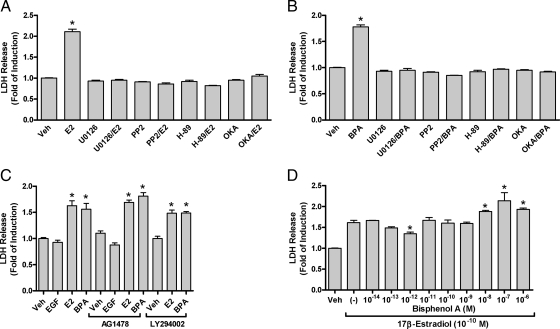

The intracellular signaling cascade(s) responsible for induction of oncotic necrosis in granule cell precursors was investigated by pulse-treatment with vehicle, 10−10 m E2, or 10−10 m BPA in the presence or absence of specific pharmacological inhibitors that target components of multiple intracellular signaling pathways. In one set of experiments, analysis of LDH release 24 h after pulsed-treatments revealed that E2 and BPA each significantly increased LDH levels to 212% and 180% relative to control, respectively (Fig. 4, A and B). Similar to what was observed for ERK-signaling (16), in the presence of the MEK1 inhibitor U0126, the src-family kinase inhibitor PP2, or the PKA inhibitor H89 a complete blockade of LDH release was observed in response to E2 or BPA (Fig. 4, A and B).

Figure 4.

Pharmacological characterization of LDH-release induced by E2 and BPA. Granule cell cultures were exposed to (A) 10−10 m E2, (B) 10−10 m BPA, or vehicle as a 15-min pulsed treatment in the presence or absence of inhibitors of MEK (U0126, 10 μm), Src-family of nontyrosine kinases (PP2, 10 μm), PKA (H89, 10 μm), or PP2A (okadaic acid, 1 μm). At 24 h after drug treatment conditioned media was collected and analyzed for LDH released. C, Impact on estrogen-induced LDH release by the activation or blockade of EGF, or inhibition of the PI3K signaling pathway. D, Concentration response analysis of BPA affects on LDH release when coadministered with a fixed efficacious concentration of 17β-estradiol (10−10 m). For all experiments LDH releases is expressed as mean (±sem, n = 4) percent of control. The level of significance for each treatment group was assessed with a one-way ANOVA with significance between vehicle and treatment groups indicated by * (P < 0.05).

Along with rapidly activating ERK1/2 signaling, E2 was previously shown to rapidly increase okadaic acid sensitive PP2A phosphatase activity (20). Inhibition of PP2A with okadaic acid (OKA) also blocked the E2- and BPA-mediated LDH release observed in control treatments revealing a requirement for both rapid ERK and PP2A activation in the release of LDH from sensitive granule cell precursors (Fig. 4, A and B). Similar to E2-induced ERK1/2 activation, neither E2- nor BPA-mediated LDH release was influenced by EGFR signaling or by inhibition of phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K) signaling (Fig. 4C). In control cultures plus or minus AG1478, EGF alone did not impact LDH release. In those control cultures, treatment with E2 or BPA elevated LDH to 173% and 179% of control levels, respectively. In the presence of AG1478 LDH release was unchanged by E2 or BPA treatment (178% and 183% of control, respectively). In the presence of LY294002 the amounts of LDH-released following E2 or BPA treatment were also not significantly different than control lacking inhibitor.

Previous results investigating rapid ERK-signaling effects in cerebellar granule cells in vivo revealed an interaction between BPA and E2 that resulted in complex concentration responses (23). Here the ability of BPA to influence E2-induced LDH release was tested by cotreatment of cultures with 10−10 m E2 and increasing concentrations of BPA. This dose response analysis revealed that 10−12 m BPA significantly decreased LDH-released in response to 10−10 m E2, which is suggestive of a partial agonist action (Fig. 4D). This inhibition is similar to the inhibitory effects observed when 10−12 m BPA was able to block ∼50% of the pERK-stimulating activity of 10−10 m E2 (23). Beginning at concentrations two orders of magnitude more than E2 (10−8–10−6) BPA significantly increased LDH release in response to 10−10 m E2, revealing additive agonist actions at these higher concentration.

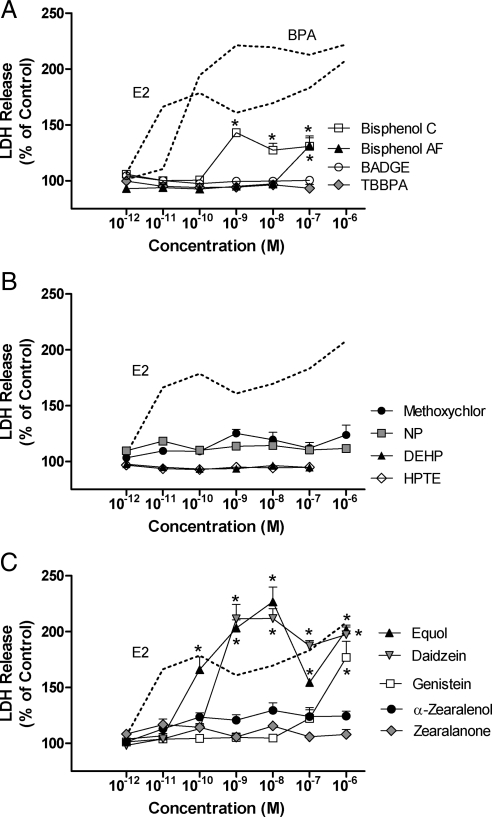

Comparative dose response analysis was done to determine the estrogen-like actions of bisphenol derivatives previously characterized to possess endocrine disruptive activities (Fig. 5). Treatment with 10−9 m of the methylated BPA derivative 2, 2′-bis (4-hydroxy-3-methylphenyl) propane (bisphenol C) resulted in a level of LDH-release that was comparable to that induced by the same concentration of E2. At higher concentrations bisphenol C also stimulated significant increases in LDH-release but with reduced efficacy. At 10−7 m the fluorinated BPA derivative 4,4′-(hexafluoro-isopropylidene) diphenol (bisphenol AF) also stimulated significant LDH-release. Neither the halogenated bisphenol A derivative 3,3′,5,5′ tetrabromo bisphenol A (TBBPA), thyroid hormone EDC, nor the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ activator bisphenol A diglycidyl ether (BADGE), induced an estrogen-like response across the concentration range examined (Fig. 5A).

Figure 5.

Dose-response analysis of cerebellar granule cell death for prototypic endocrine disruptors. A, Dose response analysis of LDH-release for cultures treated with different concentrations of Bisphenol C, Bisphenol AF, bisphenol A diglycidyl ether (BADGE), or tetrabromobisphenol A (TBBPA) ranging from 10−12 to 10−6 m. The dose response curves for E2 and/or BPA are plotted with a broken line for comparative purposes. B, Dose response analysis of LDH-release for methoxychlor, nonylphenol (NP), diethylhexyl phthalate (DEHP), hydroxychlor (HPTE). C, Dose response analysis of LDH-release for the phytoestrogens equol, daidizein, genistein, and the fungal compounds zearalanone and α-zearalenol. Levels of LDH release were determined 24 h after drug treatment using a colorimetric LDH assay and absorbance detection at 492 nm. At each concentration LDH release is reported as the mean percent of LDH-release relative to matched vehicle control cultures (±sem, n = 4).

The possibility of estrogen-like effects was also assessed for the methoxylated isomer of DDT methoxychlor, its biologically active metabolite 2,2 bis(4-hydroxyphenyl)-1,1,1-trichloroethane (HPTE), and the alkylphenol nonylphenol (NP) and Bis(2-ethylhexyl)phthalate diethylhexyl phthalate (DEHP). Small increases in LDH release were observed for methoxychlor and NP. From 10−9 m these modest effects were reproducible and significant for each compound. In contrast, DEHP and HPTE were without effect (Fig. 5B).

The dose-response relationships for phytoestrogens and mycoestrogens were also determined and compared with the E2 dose-response curve. The soy isoflavone daidzein induced maximal levels of LDH release at 10−9 m and 10−8 m. A modest reduction in efficacy, similar to that observed for E2, was observed between 10−7–10−6 m (Fig. 5C). The daidzein metabolite, equol, also induced significant increases in LDH levels between the concentrations of 10−10 m and 10−6 m. The equol dose-response curve, however, did not show sustained maximal responses with increasing concentration. The response to 10−7 m equol was significantly less than that of 10−8 m and 10−6 m (Fig. 5C). The response to genistein was only modest and limited to micro-molar concentrations (Fig. 5C). The fungal compounds zearalenone and α-zearalenol did not induce LDH release to any appreciable levels (Fig. 5C).

Discussion

The primary objective of the studies presented here was to evaluate and compare the commonality of the signaling cascades involved in rapid estrogen activation of ERK-signaling and the signaling cascades that result in estrogen toxicity in an immature population of cerebellar granule cells. Previous results have described important differences in the physiological consequences of rapid E2-induced ERK-signaling between immature and mature cerebellar neurons (19,24). Additionally, depending on duration of exposure, E2 can impose contrasting effects upon mitogenesis and viability in immature granule cells. Constant exposures to E2 induce neuroprotective mechanisms, whereas brief E2 exposures increase calpain-dependent cell death in sensitive subpopulations of immature granule cells (19). The protective or toxic effects resulting from long duration or pulsate estrogen exposures differ in ERK1/2 dependency. The protective effects of chronic E2 exposure are dependent on classical ER-mediated transactivation and independent of ERK1/2 signaling. By contrast, decreased granule cell viability resulting from pulsed E2 treatment is mediated by membrane receptor–initiated ERK1/2 signaling (19,20).

Concentration response analysis of rapid estrogen-like activation of ERK1/2 signaling in primary cerebellar granule cells confirmed that 10−11–10−10 m E2 and BPA were effective at activating the ERK1/2 signaling pathway in cultured granule cells (19,20). At those physiological concentrations the rapid effects of those estrogens were identified as being mediated via the ERK1/2 signaling cascade through a G protein–dependent mechanism that involved a PKA-dependent and PTX-sensitive Gαi/o or Gβγ-dependent mechanism (20). Those studies also revealed that coincident with increased ERK activity, estrogens also induce a rapid increase in PP2A activity (19,20). This increase in phosphatase activity was proposed to play a role in the physiological actions resulting from rapid estrogen signaling in granule cell neurons. Rapid E2-induced ERK signaling and PP2A activation, while temporally linked, are mediated through different signaling mechanisms involving unique membrane associated and intracellular E2 receptor systems, respectively. Based on those findings we hypothesized that after estrogen exposure, long-term down-regulation of ERK-activity would follow the well-characterized rapid and transient activation of ERK1/2. Long-term decreases in ERK-activity were confirmed by the observation of suppressed basal ERK-phosphorylation lasting up to 36 h post treatment (Fig. 2C1). That finding supports a role for decreased ERK-signaling in the physiological consequence of rapid E2-signaling and raises the possibility that rapidly increased PP2A activity and decreased ERK signaling may have important influences on the neuroprotective actions of estradiol. That hypothesis was further supported by the observation that okadaic acid fully blocked LDH release in response to E2 or BPA (Fig. 4, A and B).

In the cerebellum, where only ERβ is expressed at any appreciable level, the rapid effects of E2 on ERK phosphorylation were proposed to be mediated via ERβ (23,25). Previous in vivo results support the hypothesis that ERβ mediates rapid E2 actions in the cerebellum because of the close correlation between the ontogeny of ERβ expression in responsive cell types and the onset of detectable rapid actions of E2 on pERK-IR was observed (23). Here concentration response analysis using the ERα selective agonist PPT and the ERβ selective agonist DPN was performed to pharmacologically define the nature of the ER-like receptor responsible for initiating rapid signaling. The ability of DPN, but not PPT, to selectively induce estrogen-like affects strongly supports the notion that rapid signaling effects of estrogens are initiated through ERβ-like receptor systems.

The synthetic estrogen DES and the EDC BPA, similar to E2, induce ERK1/2 activation at low nanomolar concentrations in cerebellar granule cells. In contrast to neuroprotective effects from chronic treatments, pulsed treatments with BPA induces an E2-like neurotoxic response (20). Pharmacological dissection of the signaling mechanisms for E2- and BPA-induced cell death revealed an identical correlation with the mechanisms of E2-mediated ERK1/2 activation, as demonstrated by dependency on PKA, c-Src, and ERK signaling but not EGFR signaling (Fig 4, A–C). In addition, PP2A activity was also shown to be required for estrogenic induction of granule cell death. Estradiol-induced PP2A activation was previously shown insensitive to PTX and not responsive to E2-BSA suggesting a mechanism that was independent of the ER-ERK pathway. Similarly, the cell-impermeable nonselective ligand E2-BSA did not stimulate E2-like cell death across a concentration range that spans six orders of magnitude (Fig. 3A). Together with our previous results, these findings reveal that ER-induced LDH release is mediated by a plasma membrane-associated ERβ-like mechanism and intracellular activation of PP2A. The signaling cascades involved in E2-mediated ERK and PP2A signaling are integral components of the mechanisms responsible for E2- and BPA-mediated cell death. Thus, estrogen-mediated oncotic cell death in cerebellar granule cells appears to represent an integration of membrane associated and intracellular-initiated signaling pathways that are mediated via ERβ.

As a second objective, studies were included to assess the estrogen specificity and sensitivity of immature granule cells to a battery of estrogenic and nonestrogenic EDCs. Using known ER-affinity data and characterized estrogenic and nonestrogenic endocrine disrupting activities as an initial guide, test compounds were selected to further investigate the ability of this assay to selectively discriminate EDCs that impact ERβ-mediated estrogen signaling. Comparative dose-response analysis was performed for 17β-estradiol, its physiological inactive stereo-isomer 17α-estradiol, the ERα-selective agonist PPT, the ERβ-selective agonist DPN, and testosterone to assess steroidal specificity of the response. As discussed above, the results of that analysis demonstrate a highly selective estrogenic response mediated via an ERβ-like receptor system.

The estrogenic actions of the prototypical isoflavone phytoestrogens and the daidzein metabolite equol were also analyzed. Both genistein and daidzein preferentially bind ERβ (26,27). Human bacterial flora in the intestine produces the active enantiomer s-equol which is a potent and highly selective ligand of ERβ (28). The dose-response relationships of isoflavones and mycoestrogens were compared with the E2 dose-response curve. Daidzein from 10−9 to 10−6 m induced LDH release to levels similar to those resulting from E2 exposure. The daidzein metabolite equol also induced significant increases in LDH levels between the concentrations of 10−10 and 10−6 m. The response to genistein was only modest and limited to micromolar concentrations. Interestingly, genistein was the only EDC tested that preferentially binds ERβ that did not produce a strong estrogen-like response. However, genistein had previously been shown to inhibit ERK activity in human aortic smooth muscle cells (29) and thus would not be expected to serve as a good selective agonist for the ERK-dependent end point being assayed. The mycoestrogens α-zearalenol and zearalenone bind ERα with relative binding affinities of about half and a tenth that of E2, respectively (30). Neither α-zearalenol nor zearalenone induced LDH release to an appreciable level, suggesting little or no activity via the rapid ERβ signaling mechanism active in granule cells.

Diethylstilbestrol is a high affinity ligand of both ERα and ERβ, while the binding affinity of BPA at ERβ is 6.6-fold higher than at ERα (31). Strikingly, it was found that DES induced LDH release to 150 percent of control at concentrations as low as 10−12 m with efficacy increasing to 250 percent of control as the concentrations increased to 10−6 m. Bisphenol A was also highly efficacious inducing a 2-fold increase in LDH release in the 10−10 to 10−6 m concentration range.

In addition to the xenoestrogen BPA, the estrogen-like actions of specific BPA derivatives, bisphenol C, bisphenol AF, tetrabromobisphenol A, and bisphenol A diglycidyl ether (BADGE) were analyzed. These BPA derivatives had previously been characterized as having effects on specific endocrine systems. Bisphenol C was shown to be estrogenic and to stimulate thyroid hormonal activity in rat pituitary cell line GH3, while bisphenol AF is a potent and highly efficacious estrogen in an MCF7 ERE-luciferase assay and also antagonizes androgenic activity of 5α-dihydrotestosterone in mouse fibroblast cell line NIH3T3 (32,33). As an EDC tetrabromobisphenol A can impact thyroid hormone activity and also act as an inhibitor of ERα ERE-transcription in MCF-7 cells (33,34), whereas BADGE is an activator of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ) (35). Concentration response analyses of these BPA-related compounds showed that bisphenol C and bisphenol AF exhibited modest estrogen-like responses while tetrabromobisphenol A and BADGE did not induce a response across the concentration range examined. The findings from the comparative concentration response analysis of these BPA derivatives was consistent with the endocrine disrupting activities previously characterized in other ER-expressing systems, supporting further the notion that the observed neurotoxicity actions on granule cells is an estrogen-like response.

The organochlorine EDC methoxychlor is used as a pesticide which shows low binding affinities and low transactivational activities for both ERα and ERβ (27). Using an estrogen responsive luciferase assay in HepG2 cells, the metabolite of methoxychlor HPTE was shown to be a potent agonist of human ERα (EC50 5 nm) and rat ERα (EC50 1 nm), yet has little activity at the human or rat ERβ (36,37). Diethylhexyl phthalate is used as a plasticizer that is released from polyvinyl chloride with weak ERα binding properties (38), and nonylphenol is an efficacious but very low potency estrogenic alkylphenolic compound. In agreement with the lack of ERβ-specific activities for these estrogenic EDCs, none of these ERα binding compounds was able to significantly impact cell death in cerebellar granule cells. Thus it appears that only EDCs with ERβ activities like daidzein, equol, diethylstilbestrol, and bisphenol A were observed to induce E2-like neurotoxicity. The responsiveness of granule cells to the well-characterized ERβ selective agonist DPN, and the lack of response for PPT and other ERα selective ligands, suggests that oncotic cell death in these immature granule cells is mediated by ERβ-like receptor systems. The highly sensitive and specific responsiveness of developing primary cultured granule cells to estrogenic compounds acting via ERβ demonstrated here reveal the usefulness for both mechanistic analysis and as an in vitro screening assay to detect rapid estrogen-signaling and to identify EDCs that act at ERβ to rapidly regulate intracellular signaling.

Footnotes

This work was supported by National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences Grant RC2-ES-018765 and R01-ES015145 and the University of Cincinnati Center for Environmental Genetics (P30-ES06096).

Disclosure Summary: The authors have nothing to declare.

First Published Online October 6, 2010

Abbreviations: EDC, Estrogen-like endocrine disrupting chemical; ER, estrogen receptor; ERK, extracellular-signal regulated kinase; LDH, lactate dehydrogenase; OKA, okadaic acid; PI3K, phosphoinositide 3-kinase; PP2A, protein phosphatase 2A; PPT, 4,4′,4′-(4-propyl-[1H]-pyrazole-1,3,5-triyl) trisphenol.

References

- Diamanti-Kandarakis E, Bourguignon JP, Giudice LC, Hauser R, Prins GS, Soto AM, Zoeller RT, Gore AC 2009 Endocrine-disrupting chemicals: an Endocrine Society scientific statement. Endocr Rev 30:293–342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang IA, Galloway TS, Scarlett A, Henley WE, Depledge M, Wallace RB, Melzer D 2008 Association of urinary bisphenol a concentration with medical disorders and laboratory abnormalities in adults. JAMA 300:1303–1310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyl RW, Myers CB, Marr MC, Sloan CS, Castillo NP, Veselica MM, Seely JC, Dimond SS, Van Miller JP, Shiotsuka RN, Beyer D, Hentges SG, Waechter Jr JM 2008 Two-generation reproductive toxicity study of dietary bisphenol A in CD-1 (Swiss) Mice. Toxicol Sci 104:362–384 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howdeshell KL, Furr J, Lambright CR, Wilson VS, Ryan BC, Gray Jr LE 2008 Gestational and lactational exposure to ethinyl estradiol, but not bisphenol A, decreases androgen-dependent reproductive organ weights and epididymal sperm abundance in the male long evans hooded rat. Toxicol Sci 102:371–382 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryan BC, Hotchkiss AK, Crofton KM, Gray Jr LE 2010 In utero and lactational exposure to bisphenol A, in contrast to ethinyl estradiol, does not alter sexually dimorphic behavior, puberty, fertility, and anatomy of female LE rats. Toxicol Sci 114:133–148 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tyler CR, Jobling S, Sumpter JP 1998 Endocrine disruption in wildlife: a critical review of the evidence. Crit Rev Toxicol 28:319–361 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosselli M, Reinhart K, Imthurn B, Keller PJ, Dubey RK 2000 Cellular and biochemical mechanisms by which environmental oestrogens influence reproductive function. Hum Reprod Update 6:332–350 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crain DA, Eriksen M, Iguchi T, Jobling S, Laufer H, LeBlanc GA, Guillette Jr LJ 2007 An ecological assessment of bisphenol-A: evidence from comparative biology. Reprod Toxicol 24:225–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setchell KD, Zimmer-Nechemias L, Cai J, Heubi JE 1998 Isoflavone content of infant formulas and the metabolic fate of these phytoestrogens in early life. Am J Clin Nutr 68:1453S–1461S [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bingham SA, Atkinson C, Liggins J, Bluck L, Coward A 1998 Phyto-oestrogens: where are we now? Br J Nutr 79:393–406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zinedine A, Soriano JM, Moltó JC, Mañes J 2007 Review on the toxicity, occurrence, metabolism, detoxification, regulations and intake of zearalenone: An oestrogenic mycotoxin. Food Chem Toxicol 45:1–18 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farmakalidis E, Murphy PA 1984 Oestrogenic response of the CD-1 mouse to the soya-bean isoflavones genistein, genistin and daidzin. Food Chem Toxicol 22:237–239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willard ST, Frawley LS 1998 Phytoestrogens have agonistic and combinatorial effects on estrogen-responsive gene expression in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells. Endocrine 8:117–121 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rozman KK, Bhatia J, Calafat AM, Chambers C, Culty M, Etzel RA, Flaws JA, Hansen DK, Hoyer PB, Jeffery EH, Kesner JS, Marty S, Thomas JA, Umbach D 2006 NTP-CERHR expert panel report on the reproductive and developmental toxicity of genistein. Birth Defects Res B Dev Reprod Toxicol 77:485–638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zava DT, Blen M, Duwe G 1997 Estrogenic activity of natural and synthetic estrogens in human breast cancer cells in culture. Environ Health Perspect 105 (Suppl 3):637–645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belcher SM, Zsarnovszky A 2001 Estrogenic actions in the brain: estrogen, phytoestrogens, and rapid intracellular signaling mechanisms. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 299:408–414 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Falkenstein E, Tillmann HC, Christ M, Feuring M, Wehling M 2000 Multiple actions of steroid hormones-A focus on rapid, nongenomic effects. Pharmacol Rev 52:513–556 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farach-Carson MC, Davis PJ 2003 Steroid hormone interactions with target cells: cross talk between membrane and nuclear pathways. J Pharmacol Exp Ther 307:839–845 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong JK, Le HH, Zsarnovszky A, Belcher SM 2003 estrogens and ICI182,780 (Faslodex) modulate mitosis and cell death in immature cerebellar neurons via rapid activation of p44/p42 mitogen-activated protein kinase. J Neurosci 23:4984–4995 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belcher SM, Le HH, Spurling L, Wong JK 2005 Rapid estrogenic regulation of extracellular signal- regulated kinase 1/2 signaling in cerebellar granule cells involves a G protein- and protein kinase A-dependent mechanism and intracellular activation of protein phosphatase 2A. Endocrinology 146:5397–5406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le HH, Carlson EM, Chua JP, Belcher SM 2008 Bisphenol A is released from polycarbonate drinking bottles and mimics the neurotoxic actions of estrogen in developing cerebellar neurons. Toxicol Lett 176:149–156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wong JK, Kennedy PR, Belcher SM 2001 Simplified serum- and steroid-free culture conditions for the high-throughput viability analysis of primary cultures of cerebellar neurons. J Neurosci Methods 110:45–55 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zsarnovszky A, Le HH, Wang HS, Belcher SM 2005 Ontogeny of rapid estrogen-mediated ERK1/2 signaling in the rat cerebellar cortex in vivo: potent non-genomic agonist and endocrine disrupting activity of the xenoestrogen bisphenol A. Endocrinology 146:5388–5396 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Belcher SM 2008 Rapid signaling mechanisms of estrogens in the developing cerebellum. Brain Res Rev 57:481–492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jakab RL, Wong JK, Belcher SM 2001 Estrogen receptor-α immunoreactivity in differentiating cells of the developing rat cerebellum. J Comp Neurol 430:396–409 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuiper GG, Carlsson B, Grandien K, Enmark E, Haggblad J, Nilsson S, Gustafsson JA 1997 Comparison of the ligand binding specificity and transcript tissue distribution of estrogen receptors α and β. Endocrinology 138:863–870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuiper GG, Lemmen JG, Carlsson B, Corton JC, Safe SH, van der Saag PT, van der Burg B, Gustafsson JA 1998 Interaction of estrogenic chemicals and phytoestrogens with estrogen receptor β. Endocrinology 139:4252–4263 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Setchell KD, Clerici C, Lephart ED, Cole SJ, Heenan C, Castellani D, Wolfe BE, Nechemias-Zimmer L, Brown NM, Lund TD, Handa RJ, Heubi JE 2005 S-Equol, a potent ligand for estrogen receptor {beta}, is the exclusive enantiomeric form of the soy isoflavone metabolite produced by human intestinal bacterial flora. Am J Clin Nutr 81:1072–1079 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dubey RK, Gillespie DG, Mi Z, Rosselli M, Keller PJ, Jackson EK 2000 Estradiol inhibits smooth muscle cell growth in part by activating the cAMP-adenosine pathway. Hypertension 35:262–266 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews J, Celius T, Halgren R, Zacharewski T 2000 Differential estrogen receptor binding of estrogenic substances: a species comparison. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol 74:223–234 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuiper GG, Carlsson B, Grandien K, Enmark E, Häggblad J, Nilsson S, Gustafsson JA 1997 Comparison of the ligand binding specificity and transcript tissue distribution of estrogen receptors alpha and beta. Endocrinology 138:863–870 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perez P, Pulgar R, Olea-Serrano F, Villalobos M, Rivas A, Metzler M, Pedraza V, Olea N 1998 The estrogenicity of bisphenol A-related diphenylalkanes with various substituents at the central carbon and the hydroxy groups. Environ Health Perspect 106:167–174 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitamura S, Suzuki T, Sanoh S, Kohta R, Jinno N, Sugihara K, Yoshihara S, Fujimoto N, Watanabe H, Ohta S 2005 Comparative study of the endocrine-disrupting activity of bisphenol A and 19 related compounds. Toxicol Sci 84:249–259 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Darnerud PO 2003 Toxic effects of brominated flame retardants in man and in wildlife. Environ Int 29:841–853 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright HM, Clish CB, Mikami T, Hauser S, Yanagi K, Hiramatsu R, Serhan CN, Spiegelman BM 2000 A synthetic antagonist for the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma inhibits adipocyte differentiation. J Biol Chem 275:1873–1877 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaido KW, Leonard LS, Maness SC, Hall JM, McDonnell DP, Saville B, Safe S 1999 Differential interaction of the methoxychlor metabolite 2,2-bis-(p-hydroxyphenyl)-1,1,1-trichloroethane with estrogen receptors alpha and beta. Endocrinology 140:5746–5753 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaido KW, Maness SC, McDonnell DP, Dehal SS, Kupfer D, Safe S 2000 Interaction of methoxychlor and related compounds with estrogen receptor alpha and beta, and androgen receptor: structure-activity studies. Mol Pharmacol 58:852–858 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ohashi A, Kotera H, Hori H, Hibiya M, Watanabe K, Murakami K, Hasegawa M, Tomita M, Hiki Y, Sugiyama S 2005 Evaluation of endocrine disrupting activity of plasticizers in polyvinyl chloride tubes by estrogen receptor alpha binding assay. J Artif Organs 8:252–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]