Abstract

Advances in genomic science create both opportunities and challenges for future generations. Both adolescents and adults may benefit or be harmed by decisions they make in response to this new science. Using a qualitative descriptive design, we interviewed 22 adolescents (11 who were aged 14-17 years and 11 who were 18-21 years) and 11 parents to determine levels of knowledge and approaches to decision making. We found that younger adolescents and their parents have very limited knowledge about genetics and genetic testing. Older adolescents have more complete information and consider a broader range of points in making decisions about hypothetical situations involving genetic testing. Adolescents and parents need much more information to enhance their ability to make decisions about using genetic services. These findings have implications for developing interventions and public health policy highlighted by the need for improved education about the benefits and harms of genetic testing.

Keywords: community, qualitative, adolescence, genetics/genomics, parenting/families

When scientists completed mapping the sequence of the human genome, they opened the way for a new discipline: genomics. Genomics, which is the study of the evolution, structure, and function of the set of genes carried by an individual, now makes it feasible to diagnose some heritable disorders prior to birth (Cummings, 2006). It also makes it possible to test an individual’s entire genome, or set of genes, to determine if they carry a mutation for a specific disease or are predisposed to specific disorders later in life (Cummings). For adults, predictive genetic tests are currently available for many health conditions, including many for which there is no known method of prevention or treatment (e.g. Huntington disease [HD]). The American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Bioethics (2001), however, recommends that such testing not be done before the age of majority.

The field of genomics and advances in genomic technology have developed rapidly as a result of the Human Genome Project (HGP), a combined effort of the National Institutes of Health and the U.S. Department of Energy. The primary goals of the HGP were to identify all of the genes and determine the sequence of base pairs in human DNA, and develop tools for genomic analysis (Human Genome Project, 2009). While advances are being made daily in ways to improve the lives of human beings, particularly with regard to health, these advances come at a price, and often pose ethical dilemmas. Adolescents may be at a particular advantage in benefiting from the many advances in genomic science. The value of personalized information obtained through genetic testing may be highest in late adolescence and early adulthood. But today’s adolescents may also be the first generation to suffer from negative consequences of this burgeoning branch of science. Developing adolescents are more likely to take risks and make decisions based on limited information, with little understanding of long-term implications. The potential risks and benefits of their decisions may both be highest when their ability to use information in making reasoned decisions is lowest (Byrnes, 2002). Because adolescents have greater potential longevity than adults, they may benefit from making long-lasting health behavior changes based on results from genetic testing. They also have longer to live with potential harmful outcomes of testing such as anxiety and regret. There is ample evidence that although adolescents have access to large amounts of information about the relative dangers of behaviors such as smoking, they do not tend to use this information consistently in making decisions about engaging in these health-risk behaviors (Rodham, Brewer, Mistral, & Stallard, 2006; Wiltshire, Amos, Haw, & McNeill, 2005).

Recent studies suggest that genetic testing of adolescents is particularly salient to help them change health-risk behaviors early in life (Segal, Polansky, & Sankar, 2007). For example, substantial evidence now links genetics to smoking initiation and persistence (Sullivan & Kendler, 1999), alcohol dependence (Treutlein, Cichon, Ridinger, Wodarz, Soyka, Zill, et al, 2009), cannabis use and dependence (Agrawal & Lynskey, 2006), and obesity (Segal, Sankar, & Reed, 2004). Researchers have shown that adolescents are interested in genetic testing for susceptibility to heritable disorders such as cancer and hypercholesterolemia (Harel, Abuelo, & Kazura, 2003). Parents have also expressed interest in having their children tested for carrier status for autosomal recessive disorders prior to age 18 (Fanos & Gatti, 1999; James, Holtzman, & Hadley, 2003). Genetic testing of adolescents was viewed as essential for reproductive decision-making (James, et al.).

Decision-making ability in adolescence is widely debated and closely related to stages of emotional and cognitive development (Berkowitz, 2005; Santelli et al., 2003). Studies have shown that adolescents are strongly influenced by peers when making decisions, particularly when the decision involves taking risks (Gardner & Steinberg, 2005). It is little surprise that adolescents and their parents may hold different positions about whether or not an adolescent can decide to have genetic testing (Bradbury, et al., 2008). Although decision-making about genetic testing has been studied in adults (Klitzman, Thorne, Williamson, Chung, & Marder, 2007), only two published studies with adolescent samples were found (Duncan, Gillam, Savulescu, Williamson, Rogers, & Delatycki, 2007; 2008). These studies focused on very small clinical samples and were conducted in Australia.

In the first study (Duncan et al., 2007), eight people who were under the age of 24 years when tested for HD, were interviewed to explore the experience of genetic testing. Two of the participants had tested gene-positive and the other six were gene-negative. One of their “most notable” findings was that five of the eight participants engaged in multiple risk behaviors such as drug use prior to testing because they believed they were gene-positive (p. 1987). In the second study (Duncan et al., 2008), eight participants had been tested for HD and 10 for familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP). Findings were described in terms of harms and benefits of having gene-positive or gene-negative test results. Those who had tested gene-positive (two for HD and five for FAP) asserted that harms included knowing of their future illness, seeing distress in their parents, and having a range of negative emotions (e.g., anger, anxiety, regret). Those who had tested gene-negative (six for HD, five for FAP) asserted that harms included feeling guilty, worrying about siblings, and feeling disconnected from family. In both of these studies, participants experienced the benefits of relief of uncertainty and being able to make plans for the future (Duncan et al., 2007; 2008).

While genetic screening has become commonplace in settings such as hospitals, clinics, and offices of physicians who serve pregnant women and newborns, genetic testing is more often done within the context of services offered to individuals and families who are at risk for specific heritable disorders such as breast cancer, cystic fibrosis, or sickle cell disease (Lashley, 2007). To make a decision about either genetic screening or testing, individuals and families need information. Not surprisingly, given that 70% of Americans are online and that 80% of those have used the Internet for health information, an ethnographic study of mothers whose children either had a genetic disorder or were at-risk for one found that the Internet was a major source of health information contributing to their final decision about treatment options and management (Schaffer, Kuczynski, & Skinner, 2008). Indeed, experts in adolescent development have asserted that the Internet provides not only a mechanism for peer interaction (Williams & Merten, 2008), but also much of the health information that adolescents want and need (Gray, 2005; 2008; Gray, Klein, Noyce, Sesselberg, & Cantrill, 2005).

All these factors – advances in genomic science, the unique situation facing adolescents regarding genetic testing, the availability of information on the Internet – together create an important and pressing situation. In the coming years, adolescents will have the opportunity to engage in genetic testing, whether suggested by a medical professional or through direct-to-consumer (DTC) advertising of genomic services on the Internet. Genetic testing may be life-changing, in negative as well as positive ways as Duncan and colleagues (2007; 2008) have shown. It is crucial to learn more about what adolescents and their parents know about genetic testing, as well as how both adolescents and their parents will go about making decisions regarding genetic testing.

Purpose

The purpose of this study was to determine the level of general knowledge and the methods of decision-making about genetic testing of adolescents and their parents. We addressed the following research questions:

What do adolescents and parents know about the Human Genome Project and genetic testing?

What is the difference between what younger adolescents (ages 14-17 years), their parents, and older adolescents (ages 18-21 years) know about genetic testing?

What points would adolescents and parents consider when making a decision about genetic testing?

What sources would adolescents and parents consult to assist them in making a decision about genetic testing and what additional information would they seek?

Method

Design

A qualitative descriptive study was conducted (Sandelowski, 2000), a design selected because currently there is very little published literature about genetic testing and related decision making among adolescents and parents of adolescents. This is particularly so for more generalizable samples not drawn from specialized medical clinics and patient populations (Authors, 2009).

Setting and Sample

The setting for this study was a large metropolitan area in the south central Unites States. A sample of convenience was recruited beginning with adolescents personally known to at least one of the investigators. Inclusion criteria included adolescents aged 14-21 years and parents residing with their adolescent child (14-17 year-olds only). Persons of any race or ethnicity who were able to speak English were included. Older adolescents’ parents were not interviewed because they did not live together and adolescents were of an age that they could give their own consent to use genetic services such as testing. At the end of each interview, the participant was asked to suggest one or more acquaintances that they thought might be interested in participating. This snowball technique was followed until the final multi-ethnic sample of 33 (N=33) was enrolled.

Procedure

After obtaining approval from the university’s institutional review board, two graduate research assistants were trained by the first author to recruit participants and conduct the interviews. All interviews were done by either one of these assistants or by the first author. After explaining the purpose, risks, and benefits of the study, written parental consent and adolescent assent were obtained for all participants under the age of 18. Written consent was obtained from all participants 18 years of age and older. All consents and assents included permission to audio-tape the interview. Individual interviews were conducted in a private room in the participant’s home, the interviewer’s home (on one occasion this was done for the convenience and at the request of the participant), or a public building with private space. Interviews lasted from 20-50 minutes (M = 30 minutes); older adolescents’ interviews were generally shorter owing to their class and work schedules (M = 28 minutes). Following the interview, each participant received a $20 gift card. All audio recordings were transcribed verbatim following each interview by trained transcriptionists.

Data Collection and Analysis

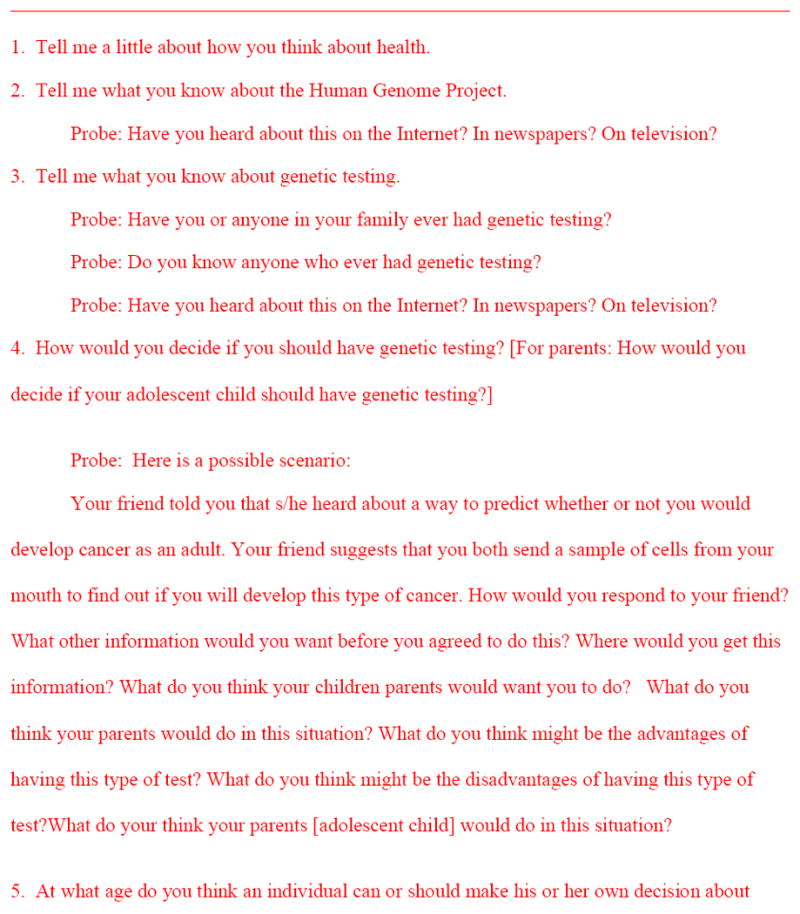

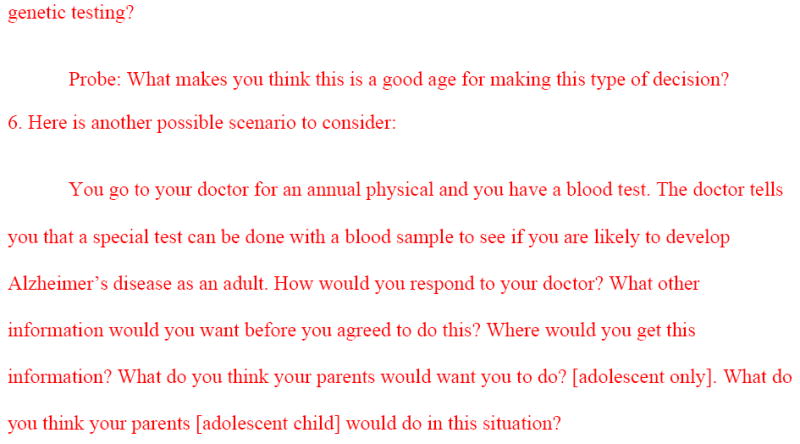

A demographic form designed for the study was used to collect characteristics of the sample, including age, gender, race/ethnicity, marital status, and known heritable disorders of the participant and immediate family members (i.e., breast, colon, or ovarian cancer, cystic fibrosis, diabetes, phenylketonuria [PKU], Duchenne muscular dystrophy, cleft lip/palate, sickle cell disease, Tay-Sachs, other). Two semi-structured interview forms (see Figure 1), one for adolescents and one for parents, were also developed by the principal investigator and included open-ended questions, probes, and hypothetical scenarios to elicit knowledge, points to consider in making a decision, and additional information the participant would want prior to making a decision.

Figure 1.

Semi-Structured Interview Questions to Identify Adolescents’ and Parents’ Understandings of Human Genome Project and Approaches to Genetic Testing

The first author listened to all audio-tapes while reading the transcriptions to check for accuracy. Transcribed interviews were then read by each of the three authors and open coding was done independently for all interviews. These codes were then compared based on a priori categories congruent with the research questions and interview schedule. All three authors reached consensus on themes that reflected both manifest and latent content. Analyses confirmed that saturation of findings was reached within eight interviews for each group.

Findings

Adolescents ranged in age from 14-21 years. The mean age of younger adolescents (ages 14-17 years) was 14.45 (mode = 14 years), five were females and six were males. Their parents were 31-61 years of age (M = 42.4 years). Eight were females and three were males. Five younger adolescents and their parents were non-Hispanic White, three were Hispanic, two were African American, and one was Asian American. Older adolescents (ages 18-21 years) were an average of 20.73 (mode 21 years), five were females and six were males. Six were non-Hispanic White, two were Hispanic, and three were Asian American.

Only one African American (male, age 14) identified himself, a parent, and a sibling as having been diagnosed with sickle cell disease, and a parent and sibling as having breast cancer. A 16 year-old non-Hispanic White female identified a sibling as having diabetes and a 16 year-old non-Hispanic White male identified a parent as having diabetes. Three parents (all females, two non-Hispanic White and one Hispanic, ages 44, 46, and 48) identified a parent as having diabetes, and one of these also wrote in Alzheimer. A 61 year-old male non-Hispanic White parent noted that his mother had had ovarian cancer. A 21 year-old non-Hispanic White male checked that his sibling had cleft lip/palate. None were currently being treated for an inherited disorder.

The following four themes were identified to answer the research questions: Knowledge, Sources of Additional Information, Points to Consider in Making Decision, and Age to Decide. The first three themes were further divided into sub-themes and/or categories. Sources of Additional Information contained eight categories: Internet, Doctors, Books or Articles, Testing Sites, Parents, Friends, Teachers, and Professional Organizations. Points to Consider in Making Decision contained seven sub-themes, each with two or more categories.

Theme: Knowledge

Knowledge contained two categories: knowledge of the HGP and knowledge of genetic testing. Only one of the younger adolescents had ever heard of the HGP; however, this 14 year-old non-Hispanic white male didn’t have a clear understanding of what it was. His response was, “Well there’s chromosomes, like X and Y, for male and female, and … I mean like explain the process, well … and I guess some genetics from your mom and dad come together to form a baby.” Similarly, only three of the parents had ever heard of the HGP and their understanding was not comprehensive. For example, a 61-year old non-Hispanic white father stated, “I understand that there’s been an ongoing activity to decode the genome. I mean, you know, I understand that there’s different genetic components of that and hopefully can figure out from all that, that mapping, what leads to what.” Another non-Hispanic white father said, “I’ve heard about it obviously before and my understanding is that it is a project to try and map human DNA.” In contrast to these responses, a 48 year-old non-Hispanic white mother stated, “I’ve heard of it. Probably when you push me about this, I honestly don’t know anything about it.”

The majority (n=7) of the older adolescents had heard of the HGP. Although their responses varied in detail, those who had heard of it had accurate knowledge. A 21 year-old non-Hispanic male said, “Oh, the human genome project is the project that they partially completed, right? Like mapping out what each gene in your body does and where it comes from and what it affects.” A 21-year-old non-Hispanic white female demonstrated a more thorough knowledge of the HGP, stating, “There started out with two companies. One was a private investigation the other one was in it for the government, I believe. They eventually collaborated and it became the Human Genome Project. It was meant to map the human genetic sequence. I think it was completed beginning of 2000ish – somewhere around there.”

Most respondents in all three groups had heard of genetic testing; however, the younger adolescents did not have accurate knowledge. Parents’ knowledge was somewhat more complete and older adolescents’ knowledge was the most accurate. A 31-year-old African American mother who said she had heard of genetic testing, however, had inaccurate information: “Like couples if they want to have babies, they can get their, you know, basically make a baby, put that in quotes. They can pull what they want to pull out of their genetics and make a human.” Other examples from each of the three groups of respondents are in Table 1.

Table 1.

Examples of Participants’ Knowledge of Genetic Testing

| Younger Adolescents |

| 14 year-old African-American female: “ I know, I think it’s where you prick your finger. Does that have something to do with DNA or something?” |

| 14 year-old Asian male: “Uh..maybe just that you test different things and see if your parents are alike or that’s my best guess.” |

| 14 year-old African-American female: I mean, I’m seeing like on TV where they find out who’s the father of the baby or something like that.” |

| Parents of Middle Adolescents |

| 48 year-old non-Hispanic white mother: “Well, for example, it’s being used to identify certain diseases, like, I think sickle cell anemia, to help families decide what their risk is in determining, say, a couple that is deciding to have children needs to know if they have the markers for or wants to know if they have the markers for particular diseases that are related to genetic markers. Then they know if their risks of having a child of that is significant or not.” |

| 41 year-old non-Hispanic white father: “… testing, using DNA samples to test parentage for instance umm…or if you know if some likely using paternal tests and stuff like that. I would imagine that it would also have to do with things like testing for particular genes that would make people prone to getting certain kinds of diseases that might be passed on from one generation to the next.” |

| 44 year-old Hispanic mother: “what I’ve heard is that it’s important because you can uh, pre-know or that if you are going to be you know carrying a faulty gene or whatever you call them and see if you can do something to prevent that disease or that malfunction or whatever in your body to not to be triggered or something …” |

| Older Adolescents |

| 21 year-old white male: “I don’t know that much. I know it’s just now starting right, pretty much. Like, now that they’ve finished the genome mapping. They get so kind of shaky in some areas ‘cause they can’t pinpoint every disease to exactly the cause.” |

| 21 year-old Hispanic female: “ think that the genetic testing can tell us a lot about what – how we want to treat our bodies so that our next generation can be at a better state.” |

| 21 year-old white female: “A lot of parents come in early on in pregnancy and try to do genetic testing to find things like Down’s syndrome, genetic abnormalities, things that would influence a pregnancy for - could make or break a birth basically.” |

Theme: Sources of Additional Information

Participants reported a variety of sources of additional information they would seek when making a decision about engaging in genetic testing. Eight categories of additional information sources were identified, six by younger adolescents, six by parents, and five by older adolescents. The Internet and Doctors were each identified by the majority of participants (i.e., six middle adolescents, six parents, and eight older adolescents). Five younger adolescents identified parents and three identified books or articles and the testing site as sources of additional information. Only one identified teachers, and none identified friends. Two parents each identified books or articles and the testing site. Only one parent identified professional organizations and another parent identified parents as sources. Three older adolescents identified books or articles, three identified the testing site, and one identified friends as sources of additional information. None of the older adolescents identified teachers, parents, or professional organizations.

Theme: Points to Consider in Making Decision

Seven sub-themes were developed about points to consider in making a decision about genetic testing. Table 2, which summarizes these points of consideration, indicates the number of responses for each sub-theme and category by adolescent and parent groups.

Table 2.

Points to Consider in Making Decision About Genetic Testing.

| Sub-theme: How testing is done | 14-17 Year-Olds (n=11) |

Parents (n=11) |

18-21 Year-Olds (n=11) |

|---|---|---|---|

| How, in general | 4 | 2 | 3 |

| What happens to sample | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Who does it | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Where is it done | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| How one gets results | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| How long results last | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Sub-theme: Credibility of testing | |||

| Validity and reliability | 0 | 4 | 4 |

| Accuracy of test | 0 | 2 | 3 |

| Credibility of testing site | 0 | 1 | 3 |

| Specificity of testing | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Sub-theme: Purpose of testing | |||

| General purpose (why done) | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Personal risk for disease | 3 | 6 | 5 |

| Sub-theme: Outcomes of genetic testing | |||

| Prevent disease | 5 | 3 | 4 |

| Side effects of test | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Psychological effects | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Sub-theme: History of genetic testing | |||

| Number of people tested | 3 | 4 | 3 |

| Satisfaction with testing | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Sub-theme: Cost of genetic testing | |||

| Expense | 0 | 2 | 4 |

| Time | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Sub-theme: Meaning of test results | |||

| Ability to handle results | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Burden of knowing | 0 | 4 | 1 |

Theme: Age to Decide

The final theme was the age at which participants thought an individual can or should be able to make his or her own decision about genetic testing. Younger adolescents’ responses ranged from 12 (n=2) to 21 (n=2) years. The mean age they gave was 16.6 years (one answer was not included because the participant gave a response of “13 or 18.” All but two of the parents responded 18 (one parent did not state an age and one gave 13). The range of responses from older adolescents was 16-21 years and the mean age was 18.25 years. One participant did not answer the question, one gave a range of 18-21, and a third one said “over 18.”

Discussion

This exploratory study was intended to determine what adolescents and parents of younger adolescents know about the HGP and genetic testing, as well as what factors contribute to their decisions about undergoing genetic testing. This is an important topic given the growth of DTC genetic testing services, adolescents’ and parents’ interest in genetic testing, and the marketing of these services, particularly if the general public does not fully grasp the potential limitations and implications of the various types of testing available.

Knowledge

Our findings indicate that most of the younger adolescents and their parents do not know about the HGP and have limited understanding of genetic testing. It is worth noting that when asked how they would make decisions regarding genetic testing, almost half (45.5%) of these adolescents responded that their parents would be a source of information and advice. We were not surprised to find that more of the older adolescents had heard of the Human Genome Project than younger adolescents because the older ones would have had more exposure to science classes, including biology; however, we were surprised that more of the parents of the younger adolescents had not heard of the HGP. Older adolescents also had a more sophisticated grasp of genetic testing and its potential limitations than either the younger adolescents or their parents. Our findings suggest that more general information about this science could be made available to the general public particularly as new technologies become available making genetic testing more commonplace.

A majority of the younger adolescents thought genetic testing sounded “cool.” They also believed that it would be useful to learn about future diseases they might develop so they could take actions to prevent them (e.g., diabetes) or prepare for them in some way (e.g., Alzheimer). This finding is similar to that of Harel et al. (2003) who found that high school students would be willing to have a genetic test so they could change some of their health behaviors. This also supports the findings of Duncan and colleagues (2007) who found that adolescents at-risk for HD were able to change some of their health behaviors after having genetic testing. Potential negative impacts of genetic testing such as invasion of privacy or emotional burden did not enter into the thinking of younger adolescents in this sample about having genetic testing. Parents and older adolescents did not have the same “cool” reaction, though, and more of them were concerned about the credibility of genetic testing. Few of them mentioned concerns about the potential negative impacts of genetic testing and these responses came primarily from the older adolescent group.

Sources of Additional Information

When asked where they would go for additional information to make a decision about genetic testing, all three groups selected the Internet and doctors more than any other source. This finding supports the assertions of Gray and colleagues that the Internet is a source of health information for a large number of adolescents (Gray, 2005; 2008; Gray et al., 2005). Similarly, this finding is congruent with the findings of Schaffer et al. (2008) who also found that mothers of children with possible genetic disorders would seek additional health information from the Internet. This finding suggests that adolescents and their parents may need guidance to determine which Internet sites provide credible information to guide their decisions. This is particularly true when one considers how little most parents know about the HGP and genetic testing – many of these parents do not yet know enough to judge information quality effectively.

It was surprising that so few adolescents indicated that they would ask friends, given the substantial part that peers play in their lives. Although we didn’t ask where participants had first heard about genetic testing, some of the younger adolescents and their parents mentioned hearing about it on television, particularly with respect to determining paternity.

Adolescents and parents infrequently identified printed material in the form of books, articles, and pamphlets as sources of additional information. It may be that the Internet is seen as a more rapid way to find answers to questions than written and published materials. It is also likely that this reflects the ease with which these groups were able to access current and relevant information that they could use in making a decision. This finding supports those of Schaffer et al (2008) who found that mothers of children with genetic conditions used the Internet to assist them in making decisions about their child’s medical management.

It is clear that, in addition to the Internet, both adolescents as well as parents of younger adolescents would seek additional information from their physicians. No other human sources of additional information were cited as frequently as doctors. This finding has implications for physicians who may not yet see their role as including offering information about genetic testing (Baars, Henneman, ten Kate, 2005). With the increases in genetic testing sites on the Internet and increased consumer knowledge about genetic testing, the demand for such information will increase. Lessons learned by medical professionals in managing patients’ inquiries about prescription pharmaceutical advertisements might translate to patients learning about genetic testing through advertisements. Only younger adolescents and one parent identified parents as a source of additional information about genetic testing. These findings support those of Szybowska, Hewson, Antle, & Babul-Hirji (2007) who found that adolescents with PKU received most of the information about their genetic condition from either parents or their doctors. James et al. (2003) also found that adolescent girls who were considering genetic testing for a recessive disorder sought most information from their parents. Teachers and friends were mentioned rarely by participants. The latter is somewhat surprising because previous research has shown that adolescents spend much of their time interacting with peers (Williams & Merten, 2008) and trusting them to make decisions (Gardner & Steinberg, 2005).

Points to Consider in Making Decision

Points to consider in making a decision about genetic testing clearly included details about how the testing itself is done. Older adolescents, in contrast to younger ones, expressed greater concern about the credibility of the testing, including its validity, reliability, accuracy, and specificity. These are aspects that genetic counselors have noted as important information for clients considering genetic testing (Lashley, 2007). Only the older adolescents and one of the parents were concerned about the meaning of the results and being able to handle them. This is an important consideration when test results may point to high relative susceptibility to debilitating or life-threatening health conditions such as those that were the focus in other studies (Duncan et al., 2007; 2008).

Age to Decide

Younger adolescents clearly showed a wider range of ages at which they would consider an individual able to make a decision about genetic testing than either parents or older adolescents. This probably reflects their relative lack of maturity in making serious decisions of this nature and their inflated confidence in their own ability to make such a decision; even adolescents offering an older age (18 or older) offered reasons that reflected such immaturity (e.g., “after high school there are less things in life to worry about”). This is a new finding and has implications for policymakers that may need to regulate companies that offer DTC advertising of genetic services, as there is the potential for minors to be duped or psychologically harmed in some way by misleading advertisements (Hogarth, Javitt, & Melzer, 2008; Parrott, Volkman, Ghetian, Weiner, Raup-Krieger, & Parrott, 2008; Wade & Wilfond, 2006). Nearly all of the parents and older adolescents thought 18 was an appropriate age, which is not surprising because that is the current legal age in the state where the study was conducted. Researchers have acknowledged 18 as the age at which adolescents are eligible and can request predictive genetic testing without parental approval (Gaff, Lynch, & Spencer, 2006), but some adolescents have requested testing earlier so that they can adjust to the results while still at home, receiving support from their families (Fanos & Gatti, 1999).

Limitations and Strengths

Our approach had some limitations. The study was conducted in only one geographic location in central Texas. We did not collect data about educational level or area of parent’s employment, which might be factors that influenced the interpretation of our findings. Although we reached saturation on the themes in response to our interviews, it may be that we missed some important considerations with this sample. The study was not conducted with any participants who were currently being treated for a heritable disorder or who were receiving services from a genetic clinic. While this addresses an existing gap in the literature with a more generalizable audience, broadening the scope of the sample to include these individuals might have resulted in expanded or different findings.

Despite these limitations, this study had a number of strengths. By including the parents of younger adolescents, we now have some idea how little younger adolescents and their parents know about genetic testing and the HGP. The inclusion of two different ages of adolescents pointed to the contrasts in their understanding of genetics, genetic testing, and the information they considered important in making a decision about genetic testing. Our sample is particularly unique and important in this field of research because many projects conducted to this point have been done with patients in genetic clinics (Authors, 2009).

This sample of adolescents and parents had limited knowledge about genetic testing. Generally older adolescents had much more accurate information than younger adolescents or their parents on which to base a decision about genetic testing. This group of older adolescents also considered more aspects of the process and outcome of genetic testing than either younger adolescents or their parents. These findings point to the need for more public education about the Human Genome Project and the potential benefits and risks of genetic testing, particularly as it relates to adolescents.

Acknowledgments

Funding: Center for Health Promotion and Disease Prevention for Underserved Populations, The University of Texas at Austin School of Nursing funded by the National Institute of Nursing Research/National Institutes of Health [P30-NR05051-03S2, Alexa Stuifbergen, P.I.].

References

- Agrawal A, Lynskey MT. The genetic epidemiology of cannabis use, abuse and dependence. Addiction. 2006;101:801–812. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2006.01399.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Bioethics. Ethical issues with genetic testing in pediatrics. Pediatrics. 2001;107:1451–1455. doi: 10.1542/peds.107.6.1451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baars M, Henneman L, ten Kate LP. Deficiency of knowledge of genetics and genetic tests among general practitioners, gynecologists, and pediatricians: A global problem. Genetics in Medicine. 2005;7:605–610. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000182895.28432.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkowitz CD. The need for a developmental approach to adolescent decision-making. American Journal of Bioethics. 2005;5(5):77–78. doi: 10.1080/15265160500246350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borry P, Stultiëns L, Nys H, Bierickx K. Attitudes towards predictive genetic testing in minors for familial breast cancer: A systematic review. Critical Reviews in Oncology/Hematology. 2007;64:173–181. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2007.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Byrnes JP. The development of decision-making. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2002;31:208–215. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(02)00503-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calsbeek H, Morren M, Bensing J, Rijken M. Knowledge and attitudes towards genetic testing: A two year follow-up study in patients with asthma, diabetes mellitus and cardiovascular disease. Journal of Genetic Counseling. 2007;16:493–504. doi: 10.1007/s10897-006-9085-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cummings MR. Human heredity: Principles and issues. Belmont, CA: Thompson Brookes/Cole; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan RE. Predictive genetic testing in young people: When is it appropriate? Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health. 2004;40:593–595. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2004.00481.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan RE, Gillam L, Savulescu J, Williamson R, Rogers JG, Delatycki MB. “Holding your breath”: Interviews with young people who have undergone predictive genetic testing for Huntington Disease. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part A. 2007;143A:1984–1989. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.a.31720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Duncan RE, Gillam L, Savulescu J, Williamson R, Rogers JG, Delatycki MB. “You’re one of us now”: Young people describe their experiences of predictive genetic testing for Huntington Disease and familial adenomatous polyposis (FAP) American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C. 2008;1438C:47–55. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.30158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fanos JH, Gatti RA. A mark on the arm: Myths of carrier status in sibs of individuals with ataxia-telangiectasia. American Journal of Medical Genetics. 1999;80:338–346. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1096-8628(19991008)86:4<338::aid-ajmg8>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaff CL, Lynch E, Spencer L. Predictive testing of eighteen year olds: Counseling challenges. Journal of Genetic Counseling. 2006;15:245–251. doi: 10.1007/s10897-006-9028-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gardner M, Steinberg L. Peer influence on risk taking, risk preference, and risky decision making in adolescence and adulthood: An experimental study. Developmental Psychology. 2005;41:625–635. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.41.4.625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graneheim UH, Lundman B. Qualitative content analysis in nursing research: Concepts, procedures and measures to achieve trustworthiness. Nurse Education Today. 2004;24:105–112. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2003.10.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray NJ. Health information on the Internet—A double-edged sword? Journal of Adolescent Health. 2008;42:432–433. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2008.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray NJ. Health information-seeking behaviour in adolescence: The place of the Internet. Social Science & Medicine. 2005;60:1467–1478. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2004.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gray NJ, Klein JD, Noyce PR, Sesselberg TS, Cantrill JA. The Internet: A window on adolescent health literacy. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2005;37:243.e1–243.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2004.08.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harel A, Abuelo D, Kazura A. Adolescents and genetic testing: What do they think about it? Journal of Adolescent Health. 2003;33:489–494. doi: 10.1016/s1054-139x(03)00135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hogarth S, Javitt G, Melzer D. The current landscape for direct-to-consumer genetic testing: Legal, ethical, and policy issues. Annual Review of Genomics and Human Genetics. 2008;9:161–182. doi: 10.1146/annurev.genom.9.081307.164319. Downloaded from arjournals.annualreviews.org, 2/21/09. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Human Genome Project Information. http://www.ornl.gov/sci/techresources/Human_Genome/project/about.shtml.

- James CA, Holtzman NA, Hadley DW. Perceptions of reproductive risk and carrier testing among adolescent sisters of males with chronic granulomatous disease. American Journal of Medical Genetics Part C. 2003;119C:60–69. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.c.10007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klitzman R, Thorne D, Williamson J, Chung W, Marder K. Decision-making about reproductive choices among individuals at-risk for Huntington’s Disease. Journal of Genetic Counseling. 2007;16:347–362. doi: 10.1007/s10897-006-9080-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lashley FR. Essentials of clinical genetics in nursing practice. New York: Springer Publishing Company; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Parrott R, Volkman J, Ghetian C, Weiner J, Raup-Krieger J, Parrott J. Memorable messages about genes and health: Implications for direct-to-consumer marketing of genetic tests and therapies. Health Marketing Quarterly. 2008;25(1):8–?. doi: 10.1080/07359680802126061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richards FH. Maturity of judgement in decision making for predictive testing for nontreatable adult-onset neurogenetic conditions: A case against predictive testing of minors. Clinical Genetics. 2006;70:396–401. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-0004.2006.00696.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodham K, Brewer H, Mistral W, Stallard P. Adolescents’ perception of risk and challene: A qualitative study. Journal of Adolescence. 2006;29:261–272. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2005.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santelli JS, Rogers AS, Rosenfeld WD, DuRant RH, Dubler N, Morreale M, et al. Guidelines for adolescent health research: A position paper of the Society for Adolescent Medicine. Journal of Adolescent Health. 2003;33:396–409. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaffer R, Kuczynski K, Skinner D. Producing genetic knowledge and citizenship through the Internet: Mothers, pediatric genetics, and cybermedicine. Sociology of Health & Illness. 2008;30(1):145–159. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9566.2007.01042.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal ME, Polansky M, Sankar P. Adults’ values and attitudes about genetic testing for obesity risk in children. International Journal of Pediatric Obesity. 2007;2:11–21. doi: 10.1080/17477160601127921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Segal ME, Sankar P, Reed DR. Research issues in genetic testing of adolescents for obesity. Nutrition Reviews. 2004;62:307–320. doi: 10.1301/nr.2004.aug.307-320. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szybowska M, Hewson S, Antle BJ, Babul-Hirji R. Assessing the informational needs of adolescents with a genetic condition: What do they want to know? Journal of Genetic Counseling. 2007 doi: 10.1007/s10897-006-9060-5. online retrieved from http://www.springerlink.com/content/0513287842477282/fulltext.html on 11/14/2007. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Sullivan PF, Kendler KS. The genetic epidemiology of smoking. Nicotine & Tobacco Research. 1999;1:S51–S57. doi: 10.1080/14622299050011811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Treutlein J, Cichon S, Ridingr M, Wodarz N, Soyka M, Zill P. Genome-wide association study of alcohol dependence. Archives of General Psychiatry. 2009;66:773–784. doi: 10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2009.83. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams AL, Merten MJ. A review of online social networking profiles by adolescents: Implications for future research and intervention. Adolescence. 2008;43:253–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wiltshire S, Amos A, Haw S, McNeill A. Image, context and transition: Smoking in mid-to-late adolescence. Journal of Adolescence. 2005;28:603–617. doi: 10.1016/j.adolescence.2004.12.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]