Abstract

An attractive strategy for bone tissue engineering is the use of extracellular matrix (ECM) analogous biomaterials capable of governing biological response based on synthetic cell-ECM interactions. In this study, peptide amphiphiles (PAs) were investigated as an ECM-mimicking biomaterial to provide an instructive microenvironment for human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) in an effort to guide osteogenic differentiation. PAs were biologically functionalized with ECM isolated ligand sequences (i.e. RGDS, DGEA), and the osteoinductive potential was studied with or without conditioned media, containing the supplemental factors of dexamethasone, β-glycerol phosphate, and ascorbic acid. It was hypothesized that the ligand-functionalized PAs would synergistically enhance osteogenic differentiation in combination with conditioned media. Concurrently, comparative evaluations independent of osteogenic supplements investigated the differentiating potential of the functionalized PA scaffolds as promoted exclusively by the inscribed ligand signals, thus offering the potential for therapeutic effectiveness under physiological conditions. Osteoinductivity was assessed by histochemical staining for alkaline phosphatase (ALP) and quantitative real-time PCR analysis of key osteogenic markers. Both of the ligand-functionalized PAs were found to synergistically enhance the level of visualized ALP activity and osteogenic gene expression compared to the control surfaces lacking biofunctionality. Guided osteoinduction was also observed without supplemental aid on the PA scaffolds, but at a delayed response and not to the same phenotypic levels. Thus, the biomimetic PAs foster a symbiotic enhancement of osteogenic differentiation, demonstrating the potential of ligand functionalized biomaterials for future bone tissue repair.

1. Introduction

It is critical that synthetic biomaterials developed for therapeutic tissue engineering applications provide an instructive microenvironment that enables the requisite cellular interactions for tissue formation and regeneration. To achieve this conducive setting, biomaterials frequently take on a biomimetic character that artificially replicates the architecture and molecular signaling of native tissues. In particular, recent investigations have taken advantage of the extracellular matrix (ECM) as a template for eliciting specific biological responses within biomimetic scaffolds. The ECM is a complex network of structural and functional macromolecules that provides cellular support and biochemical cues for regulating physiology and phenotype [1, 2]. ECM is comprised mainly of collagens, proteoglycans, and glycoproteins, which vary in amount and type to account for tissue and temporal specificity [3]. Specific ligand moieties can be isolated as small oligopeptide sequences from these tissue-specific ECM molecules and incorporated into various biomaterials to direct cellular behavior via synthetic cell-ECM interactions [4]. Of particular interest to this study is the ability of ligand-functionalized biomaterials to guide the osteogenic differentiation of progenitor cells for potential use in bone tissue repair.

Research efforts into these types of ECM analogs for bone tissue regeneration encompass a diverse range of biomaterials, such as synthetic polymers, denatured collagen, ceramics, hydrogels, and self-assembling peptides [5-11]. To provide an ECM-mimicking quality, the biomaterial is typically functionalized with an isolated ligand sequence or decellularized extracellular component and subsequently evaluated for it osteogenic potential with seeded progenitor cells. However, for almost all of these type of in vitro osteogenesis studies, conditioned media containing osteogenic supplements, which classically includes dexamethasone, β-glycerol phosphate, and ascorbic acid, are utilized in combination with the inscribed ligand sequences to drive the osteogenic differentiation process [12-15]. This confounds assessment of the differentiating potential of the scaffold as directed by the synthetic cell-ligand interactions and raises questions about the true mediator of the promoted osteogenesis. Primarily, concerns arise about the osteoinductivity of the functionalized biomaterials in the absence of the exogenous factors provided by the conditioned media, especially since this does not reflect the physiological conditions that will be available in vivo. While these supplements are effective, it would ultimately be more beneficial to develop biomaterials for bone tissue regenerative purposes capable of guiding osteogenic differentiation based only on the presented ligands, irrespective of conditioned media.

An attractive ECM-mimicking biomaterial for creating tissue-specific microenvironments facilitated through synthetic cell-ligand interactions is the peptide amphiphile (PA). PAs are a broad class of molecules that self-assemble into nanofibrous supramolecular formations, emulating the native ECM architecture. These molecules consist of a peptide sequence covalently linked to a hydrophobic alkyl chain [16, 17]. The amphiphilic nature drives the self-assembly of PAs into higher ordered nanostructures, resulting in the formation of cylindrical nanofibers due to molecular shape and entropic interactions [17-19]. In this entropically favorable assembly, the hydrophobic alkyl segments are shielded within the surrounding peptide domains, thereby exposing the functional ligand motifs to the outside for biological signaling [20, 21]. Based on our previous work, we have adapted the internal peptide structure within the PA molecule for a variety of tissue engineering purposes, demonstrating its versatility for osteogenic, cardiovascular, dual scaffold functionality, and drug delivery applications [22-26].

In regards to this current investigation, we have previously shown that PAs have the capacity for guided osteogenic differentiation based only on synthetic cell-ligand interactions [22]. In this previous study, four different PAs were synthesized and evaluated for osteoinductivity based only on the inscribed ligands present. The general structure for each consisted of an alkyl tail for amphiphilicity linked to a hydrophilic peptide segment composed of an ECM isolated ligand sequence and enzyme-degradable site sensitive to matrix metalloproteinase. The ligand moieties included the isolated ECM sequences of RGDS (Arg-Gly-Asp-Ser), DGEA (Asp-Gly-Glu-Ala), and KRSR (Lys-Arg-Ser-Arg), along with a biologically-inert (serine residue) placeholder as a negative control. It was found that without the aid of stimulatory factors, PAs biologically functionalized with the RGDS ligand promoted significantly greater levels of phenotypic expression compared to all other ligand-modified scaffolds. From the same study, the DGEA functionalized PA was the only other scaffold to demonstrate some potential for ligand-mediated osteoinduction compared to the other coating conditions, which included a KRSR ligand-containing PA functionalized with a proteoglycan motif and the biologically-inert negative control. Thus, to provide a more comprehensive evaluation, this present study intends to further investigate the osteoinductivity of PA-RGDS and PA-DGEA by including gene expression analyses and adding conditioned media for comparison, thereby looking into potential synergistic effects on osteoinduction. This would offer a better overall perspective on the osteoinductivity of the biomimetic PA scaffolds and its potential for therapeutic effectiveness.

Hence, the two most promising PAs for inducing osteogenic differentiation have been selected for further investigation. PA scaffolds individually functionalized with either a RGDS or DGEA isolated ligand sequence, along with the biologically-inert negative control, have been synthesized with the same general structure and enzyme degradable functionality as before [22]. The RGDS ligand is prevalent in many ECM molecules, including fibronectin, laminin, and osteopontin, and has been well-documented to increase general cell adhesion [27, 28]. Recent studies have also shown that inclusion of the RGDS ligand can potentially increase osteogenic differentiation [22, 29-31]. DGEA is a collagen type I adhesive motif previously demonstrated to be an important signaling ligand for osteoblast differentiation [32-34]. The enzyme degradation sequence (Gly-Thr-Ala-Gly-Leu-Ile-Gly-Gln) was ubiquitous to all the designed PAs, and its inclusions allows for cell migration and ECM remodeling [19]. Finally, human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) were used for all biological evaluations of the nanofibrous PA scaffolds, providing a multipotent cell source capable of propagating along an osteogenic lineage [35].

In this work, we investigated the osteogenic differentiating potential of biomimetic PA scaffolds designed to recapitulate the biochemical and structural functionality of native ECM. By modifying the PAs with ECM-mimicking ligand sequences, it was hypothesized that the osteogenic differentiation of hMSCs would be synergistically enhanced when combined with conditioned media or directed exclusively by ligand-mediated signaling, thereby developing a potentially advantageous tissue engineering model based only on physiological conditions. To address this hypothesis, scaffold coatings of different functionalized PAs were prepared and cultured with hMSCs for up to four weeks in both the presence and absence of conditioned media. The osteoinductivity and potential synergistic effects were evaluated by cellularity, histochemical staining, and gene expression of phenotypic markers.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Preparation of peptide amphiphiles

Three different PA sequences were prepared, as listed in Table 1, using previously described methods [19, 22, 25]. Briefly, after synthesizing the peptide sequences using standard solid phase chemistry on an Advanced Chemtech Apex 396 peptide synthesizer (AAPPTec, Louisville, KY), the N-termini peptide segments were alkylated by adding palmitic acid contained in a solution of o-benzotriazole-N,N,N′,N′-tetramethyluroniumhexafluorophosphate (HBTU), diisopropylethylamine (DiEA), and dimethylformamide (DMF). A mixture of trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), deionized (DI) water, triisopropylsilane, and anisole (40:1:1:1) was next added to cleave the PAs from the resins, along with deprotecting the side groups. PA samples were then rotoevaporated to remove excess TFA, followed by precipitation in cold diethyl ether and lyophilization for 2 days. The final PA products were characterized by matrix assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight (MALDI-TOF) mass spectrometry to confirm correct syntheses.

Table 1.

Peptide Amphiphile Sequences

| Name | Chemical Sequence | MWobsb | MWcalcc |

|---|---|---|---|

| PA-RGDS | CH3(CH2)14CONH – GTAGLIGQ – RGDS | 1369.96 | 1369.97 |

| PA-DGEA | CH3(CH2)14CONH – GTAGLIGQ – DGEA | 1326.83 | 1326.92 |

| PA-Sa | CH3(CH2)14CONH – GTAGLIGQ – S | 1041.90 | 1041.82 |

PA synthesized as a negative control

Observed single ion peak for molecular weight

Calculated single ion peak for molecular weight

2.2. Cell culture on self-assembled peptide amphiphile coatings

Human mesenchymal stem cells (hMSCs) (Lonza, Walkersville, MD) isolated from bone marrow were used for all cell culturing. Cells were cultured in normal growth media (GM), consisting of Dulbecco's Modified Eagle's Medium (DMEM) (Mediatech, Manassas, VA), 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Atlanta Biologicals, Lawrenceville, GA), 1% Amphotericin B, 1% penicillin, and 1% streptomycin (Mediatech). Within a passage number of 3-6, subconfluent hMSCs were detached using 0.05% trypsin EDTA and resuspended at 225,000 cells/mL in normal GM. Four different coating conditions were seeded upon, including the bioactive sequences of PA-RGDS and PA-DGEA and negative controls of the biologically-inert PA-S and tissue culture plastic (TCP). All PAs were self-assembled as nanofibrous coatings onto TCP surfaces of 48-well tissue culture plates (BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA) using similarly described methods [22, 25]. After UV sterilization for 4 hr, each well was seeded with 100 μL (30,000 cells/cm2) from the cell suspension. Cell cultures for all of the coatings were maintained in conditioned media containing osteogenic supplements, except for PA-RGDS, which was cultured in both GM and conditioned media. (All samples cultured in conditioned media are indicated by GM + Osteogenic Supplements for all experiments, while PA-RGDS+GM denotes the only sample condition grown in normal GM.) The osteogenic supplemental factors combined with normal GM consisted of 100 nM dexamethasone, 10 mM β-glycerol phosphate, and 0.05 mg/mL ascorbic acid (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO), which are well-documented formulations for inducing osteogenic differentiation of hMSCs [36, 37]. Samples for all experiments were cultured (37° C, 95% relative humidity, 5% CO2) for up to 28 days with media changes every 3-4 days. For each assay, the samples were collected and stored at −80° C to ensure that all were analyzed together.

2.3. Measurement of cellularity

Cellularity for all samples was determined using the PicoGreen assay (Molecular Probes, Eugene, OR) to measure the amount of double-stranded DNA content according to the manufacturer's instructions. The samples were harvested after 7, 14, and 28 days using similarly described methods and stored at −80° C as described above [22]. After removing from storage, the collected samples were subjected to a thaw/freeze cycle (30 mins thawing at room temperature, 15 mins sonication, freezing at −80° C for 1 hr) to lyse the cells. PicoGreen dye was then added for fluorometric quantification of DNA content, as the concentration of double-stranded DNA was measured on a fluorescent microplate reader (Synergy HT, BIO-TEK Instruments, Winooski, VT) filtered at 485/528 (EX/EM). The amount of DNA was correlated to 7.88 × 10−6 μg DNA/cell to determine the cellularity for all samples.

2.4. Alkaline phosphatase staining

For alkaline phosphatase (ALP) staining, the cells were washed twice with phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and fixed with 70% ethanol (EtOH) for 15 mins at room temperature. After aspirating the EtOH, the cells were stained for 30 mins at room temperature with 330 μg/ml of p-nitro blue tetrazolium chloride (NBT) and 165 μg/ml of 5-bromo-4-chloro-3-indolyl phosphate (BCIP) (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA) mixed together in a buffer solution of 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 9.5 (Teknova, Hollister, CA), 100 mM NaCl, and 50 mM MgCl2 (Sigma Aldrich). Upon formation of purple-blue precipitates, the reactions were stopped by rinsing with DI water, and all samples were imaged on an Epson Perfection 4490 Photo flatbed scanner (Epson, Long Beach, CA).

2.5. Quantitative real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted after 7, 14, and 28 days using the TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen) and following the manufacturer's protocol. After drying the RNA pellets, the extracted samples were resuspended in nuclease-free water, and any residual genomic DNA contamination was digested by DNAse treatment (TURBO DNAse, Ambion, Austin, TX). RNA concentrations were measured on a ND-1000 UV spectrophotometer (Nanodrop, Wilmington, DE), and 1 μg per sample was used for all cDNA syntheses, as reversed-transcribed by the iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) per manufacturer's instructions. Real-time PCR assays were then performed using iQ SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad) on an iCycler iQ Real-Time PCR machine (Bio-Rad). PCR amplification was achieved under the following parameters: 95° C for 3 mins, followed by 40 cycles of 95° C for 20 secs, 55° C for 20 secs, and 72° C for 20 secs. Specific primer sequences for Runx2, ALP, osteocalcin (OCN), and glyceraldehydes 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) were used to evaluate gene expression, as shown in Table 2. Negative control samples without the cDNA template were run in parallel to check for genomic DNA contamination, and melt-curve analyses were performed at the end of all PCR runs to ensure primer specificity. For this study, gene expression data were analyzed by the 2−ΔΔCt method, as described previously [38]. Briefly, the gene expression data was normalized to GAPDH and expressed as the fold ratio relative to the PA-S control group.

Table 2.

Primer Sequences for Real-Time PCR

| Primer | Sequence (5′–3′) | GenBank identification |

|---|---|---|

| Glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase (GAPDH) |

NM_002046 | |

| Sense | AAC AGC GAC ACC CAC TCC TC | |

| Antisense | CAT ACC AGG AAA TGA GCT TGA CAA | |

| Runx2 | NM_004348 | |

| Sense | AGA TGA TGA CAC TGC CAC CTC TG | |

| Antisense | GGG ATG AAA TGC TTG GGA ACT | |

| Alkaline phosphatase (ALP) | NM_000478 | |

| Sense | ACC ATT CCC ACG TCT TCA CAT TT | |

| Antisense | AGA CAT TCT CTC GTT CAC CGC C | |

| Osteocalcin (OCN) | NM_199173 | |

| Sense | CAA AGG TGC AGC CTT TGT GTC | |

| Antisense | TCA CAG TCC GGA TTG AGC TCA |

2.6. Statistical analysis

All experiments were performed in quadruplicate data sets. The values for cellularity and gene expression are reported as means ± standard deviation. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) and Tukey's multiple comparison tests were performed to determine possible significant differences using SPSS software (Chicago, IL). For all statistical analyses, p < 0.05 was considered significant.

3. Results

3.1. Analysis of cellularity

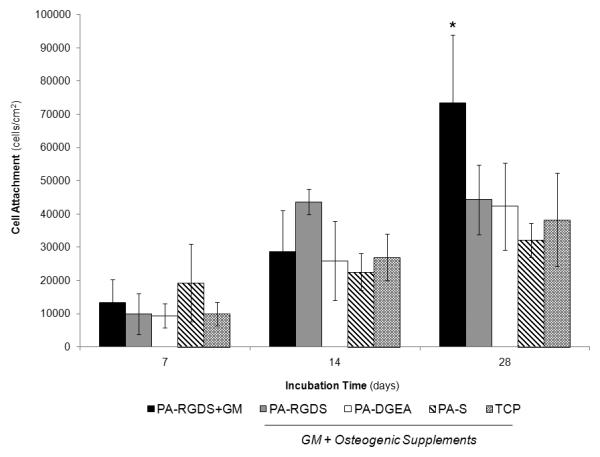

As progenitor cells begin to differentiate along an osteogenic lineage, they transition from a state of proliferation to a differentiated phenotype that is defined by matrix maturation and subsequent mineralization [39]. Applying this rationale, cell attachment over time is an important first indicator of osteogenic differentiation because the level of proliferation will begin to plateau as this phenotypic shift occurs. As shown in Figure 1, hMSCs were grown in conditioned media for 28 days on four different coating surfaces, except for PA-RGDS, which was additionally cultured in normal GM. For both days 7 and 14, no significant differences in cell attachment were observed for all surfaces, regardless of the type of cell culture media used. While there was a general 2-3 fold increase between days 7 and 14, the cell proliferation held steady over the final two weeks for all samples grown in conditioned media. The only exception was the cell attachment for PA-RGDS+GM (73,414.8 ± 20,415), which exhibited significantly more attachment after 28 days compared to the other coatings. This indicates that the conditioned media had an inhibitory effect on cell proliferation over time, as no samples exceeded 45,000 cells/cm2 after 28 days, and hints that the cells had shifted to a differentiated osteogenic state. Conversely, the hMSCs cultured on PA-RGDS in normal GM became over confluent during the course of the incubation, which is more likely to lead to delayed osteogenic differentiation as mediated by ligand signaling alone.

Figure 1.

Cell proliferation of hMSCs over 28 days. All samples were cultured in conditioned media (GM + Osteogenic Supplements) with the exception of PA-RGDS+GM, which used normal GM only. *PA-RGDS+GM promoted significantly greater cell attachment than PA-DGEA, PA-S, and TCP after 28 days (p < 0.05).

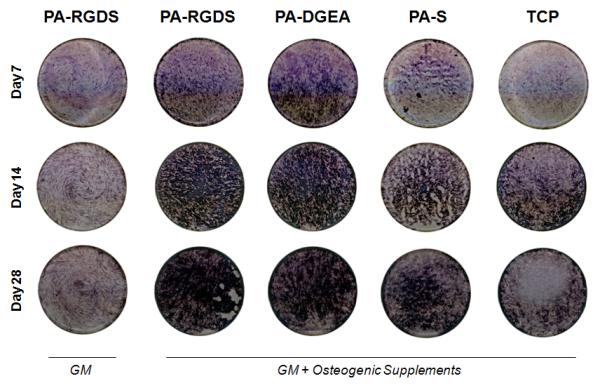

3.2. ALP histochemical staining

To first assess the induced level of osteogenic differentiation, ALP activity was qualitatively evaluated using histochemical staining. ALP is a widely used osteogenic marker, and its enzymatic activity can be visualized as purple-blue precipitates via histochemical staining. For this study, the ALP activity was evaluated over 28 days with and without conditioned media. The staining procedure was performed on all the coating conditions, and representative images for each time point are shown in Figure 2. Two prevalent themes emerged from the staining results: (1) greater ALP activity directly correlated to the inclusion of conditioned media and (2) the incorporated bioactive ligands greatly enhanced the visualized level of activity. Specifically, both the PA-RGDS and PA-DGEA coatings grown in conditioned media exhibited significantly more ALP activity than the non-functionalized control surfaces of PA-S and TCP for all time points, despite the prevailing presence of stimulatory factors. At the same time, the ALP activity for both PA-RGDS and PA-DGEA progressively increased throughout the incubation, displaying the most precipitation by day 28 to indicate continuous ligand-mediated synergistic enhancement. Furthermore, even when the osteogenic supplements were removed, the PA-RGDS coating was still able to induce a visible level of ALP activity. The level of activity was comparable to the PA-S and TCP control surfaces in conditioned media after 7 days, but over time, the effect of the supplements on the osteogenic differentiation process became too dominant for the unaided PA-RGDS to keep pace.

Figure 2.

ALP histochemical staining to qualitatively evaluate osteogenic differentiation. hMSCs were cultured on all coating conditions for up to 28 days in both normal GM and conditioned media (GM + Osteogenic Supplements). Representative images depicting the ALP activity for all samples in the tissue culture plate wells are shown.

3.3. Osteogenic gene expression using quantitative real-time PCR

The gene expressions of several key markers were quantified for all of the coating conditions over 28 days to determine the promoted levels of osteogenic differentiation. Three different target genes were analyzed, including Runx2, ALP, and OCN. Runx2 is an important transcription factor for osteogenic differentiation because it regulates the downstream expression of many phenotypic markers [40]. Two of these downstream markers include ALP and OCN. Sequentially, ALP precedes OCN in the differentiation process, as ALP helps to prepare the ECM for deposition before the onset of mineralization that coincides with OCN expression [34, 41]. Thus, the gene expressions were evaluated for markers prominent during different stages of the osteogenic differentiation process.

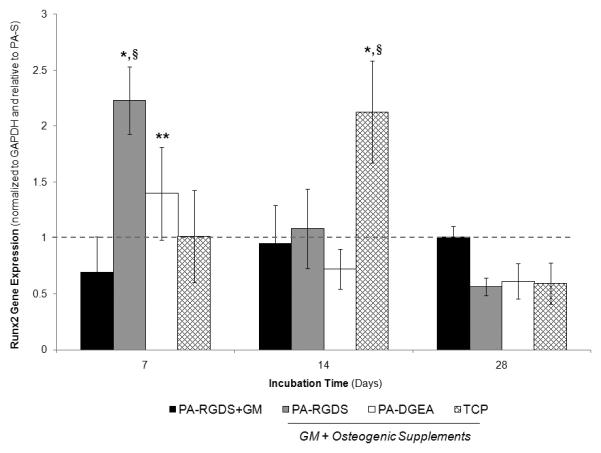

Runx2 gene expression was first quantified, as shown in Figure 3. The results for this early osteogenic marker indicated significantly more expression on day 7 for PA-RGDS cultured in the conditioned media compared to all of the other surface coatings. PA-DGEA followed with greater expression than PA-RGDS+GM over the same time period. Indicative of the osteogenic maturation process, the expression levels for PA-RGDS and PA-DGEA were downregulated by day 14 after previously peaking the week before, while the negative control TCP surface caught up and exhibited increased expression. Thus, the addition of the bioactive ligands to the PA coatings resulted in enhanced Runx2 expression at earlier time points when synergistically combined with osteogenic supplements. Meanwhile, the gene expression for PA-RGDS-GM was only able to reach the same expression levels as the stimulated control surfaces after 28 days, signifying a prolonged delay in osteoinduction.

Figure 3.

Gene expression profile for Runx2 over 28 days. All samples were cultured in conditioned media (GM + Osteogenic Supplements) with the exception of PA-RGDS+GM, which used normal GM only. Values are expressed as a mean ± standard deviation relative to PA-S (dashed line) for all incubation periods. For each time point, *PA-RGDS promoted significantly more expression than all other coating conditions, **PA-DGEA expressed more than PA-RGDS+GM, and §indicates samples greater than the normalization control of PA-S (p < 0.05).

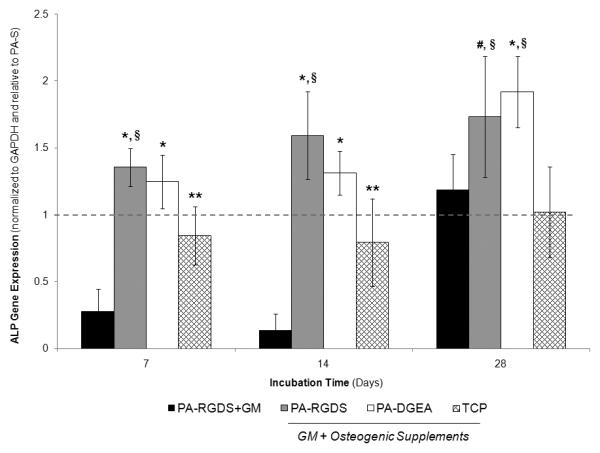

ALP gene expression was next analyzed, as depicted in Figure 4. Again, an enhanced synergistic effect on gene expression was observed for the biologically functionalized PA coatings combined with conditioned media. At every time point, PA-RGDS expressed significantly greater ALP levels than both the PA-S and TCP control surfaces. Similarly, PA-DGEA exhibited increased ALP expression throughout the experiment in comparison to the same control surfaces, only lagging slightly behind PA-RGDS until day 28. Concurrently, the ALP gene expression for PA-RGDS+GM trended the same as previously shown for Runx2, displaying delayed levels of ALP expression before peaking at day 28.

Figure 4.

Gene expression profile for ALP over 28 days. All samples were cultured in conditioned media (GM + Osteogenic Supplements) with the exception of PA-RGDS+GM, which used normal GM only. Values are expressed as a mean ± standard deviation relative to PA-S (dashed line) for all incubation periods. For each time point, significantly more expression was observed in comparison to *PA-RGDS+GM and TCP, **PA-RGDS+GM only, #TCP only, and §indicates samples greater than the normalization control of PA-S (p < 0.05).

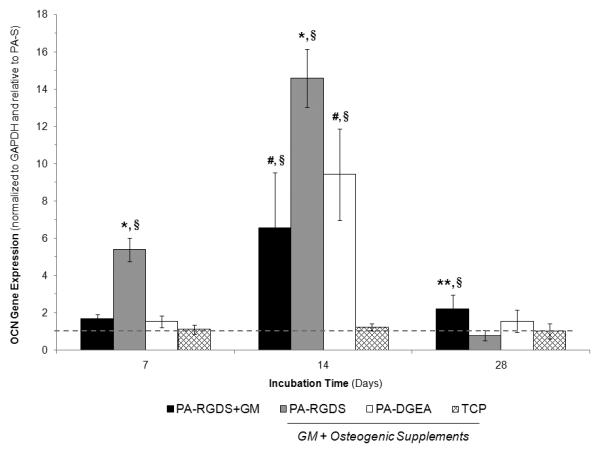

The gene expression results for the OCN marker are shown in Figure 5. The OCN expression profile compared favorably to those observed in Runx2 and ALP, as the synergistic combination of bioactive PA coatings and conditioned media again promoted increased levels of gene expression. This was particularly evident for PA-RGDS, which produced significantly greater OCN levels than all other coatings at days 7 and 14. OCN expression was also significantly higher for PA-DGEA compared to both PA-S and TCP after 14 days. Interestingly, PA-RGDS+GM promoted increased OCN expression in comparison to the control surfaces after 14 and 28 days. Thus, the ligand-functionalized PA coating was able to induce a significant level of OCN expression without any stimulatory factors.

Figure 5.

Gene expression profile for OCN over 28 days. All samples were cultured in conditioned media (GM + Osteogenic Supplements) with the exception of PA-RGDS+GM, which used normal GM only. Values are expressed as a mean ± standard deviation relative to PA-S (dashed line) for all incubation periods. For each time point, significantly greater expression was found compared to *all other coating conditions, **both PA-RGDS and TCP, #TCP only, and §indicates samples greater than the normalization control of PA-S (p < 0.05).

4. Discussion

In this study, ECM analogous biomaterials were investigated for osteoinductive potential in a continuing effort to advance bone tissue engineering solutions and follow-up our previous research findings. Emphasizing a biomimetic strategy, PAs were employed to provide specific biological signaling inscribed within a nanofibrous scaffold structurally similar to native ECM. Different ligand sequences were isolated for incorporation into the PAs, and the ability of these functionalized biomaterials to promote the osteogenic differentiation of hMSCs individually or in combination with conditioned media was studied. Based on our past studies, it was believed that the bioactive ligands within the PAs would foster a symbiotic relationship with the conditioned media, leading to synergistically enhanced osteogenic differentiation. Additionally, removal of the conditioned media was investigated, as it would be more physiologically relevant to control osteogenic differentiation based on the biomimetic scaffold alone.

Previous literature investigating the osteoinductivity of biomaterials is very prevalent and far-reaching. Numerous studies have demonstrated the effectiveness of conditioned media containing the aforementioned supplements of dexamethasone, β-glycerol phosphate, and ascorbic acid for promoting the osteogenic differentiation of progenitor cells seeded on biologically-inert materials [8, 36, 42]. More recently, efforts have shifted toward investigating ECM-mimicking functionalizations of osteogenic biomaterials to guide the differentiation process; although, they have almost all been exclusively conducted with conditioned media. Nevertheless, these studies demonstrated the potential for synergistic enhancement of osteogenic differentiation by combining bioactive ligands with supplemental factors [31, 43-47]. While this provides insightful information, comparative studies also investigating the removal of exogenous factors are very lacking. The potential for unaided ligand-mediated osteogenic differentiation as promoted by ECM analogous biomaterials does exist, evidenced by past studies with and without conditioned media [29, 30, 48], including findings from our previous research with PAs [22]. However, more comprehensive investigations into the effectiveness of osteogenic differentiation as promoted by ligand-modified biomaterials in the absence or presence of conditioned media hold great promise. Specifically, it was important to conduct new studies examining enhanced osteogenic differentiation resulting from synergistic effects between isolated bioactive ligands and supplemental factors compared to the potential of the ligand signals to exclusively promote osteogenesis to the same phenotypic levels as conditioned media.

To assess osteoinductivity in this study, cellularity, histochemical ALP staining, and quantitative real-time PCR gene analysis were performed. From these experiments, the biologically functionalized PA coatings of PA-RGDS and PA-DGEA were found to synergistically enhance osteogenic differentiation when combined with conditioned media compared to the PA-S and TCP control surfaces. Based on the initial cell attachment results, the differences observed in the osteogenic differentiation evaluations cannot be attributed to contrasting cellularities between the surfaces and are most likely due to the specific bioactive ligands because the cell densities remained constant for all sample conditions, except those not containing conditioned media. These findings were validated by the ALP staining and real-time PCR gene expression results. Of note for the PCR experiments, gene expression values were normalized as a relative fold increase compared to PA-S instead of TCP because this ensured unbiased comparison between the different PA coatings, eliminating concerns over inconsistencies in charge and conformation between the compared scaffolds. Thus, the ECM-mimicking PA scaffolds can robustly improve osteoinductivity in combination with conditioned media. Furthermore, functionalization with the RGDS ligand proved to be slightly more effective than the DGEA ligand, as the gene expression data for all markers were consistently greater for this specific cell-ligand interaction.

The reasoning behind the observed osteoinductive responses elicited by the different PAs is still not fully understood, but the most likely mediator is the specific integrin bindings presented by the bioactive ligands. Both the RGDS and DGEA ligands promote integrin-mediated interactions capable of influencing intracellular signaling cascades; the RGDS ligand exhibits an affinity for alpha5-beta1 (α5β1) cell-integrin interactions [49], while DGEA maintains a predominant specificity for the alpha2-beta1 (α2β1) integrin [32]. Additionally, it has been well established that ECM signaling via integrin binding can promote osteogenic differentiation through the FAK/ERK 1/2-MAPKs intracellular pathway [40]. Consequently, it is believed that the enhanced osteogenic induction promoted by the bioactive PAs is due to the specific cell-ligand interactions. This supports previous literature by Kundu et al., which found α5β1 and α2β1 integrin-mediated signaling to be preferential for inducing the osteogenic differentiation of hMSCs via the FAK/ERK 1/2-MAPKs intracellular pathway [50]. Other evidence has recently emerged further demonstrating the importance of α5β1 and α2β1 integrin-mediated signaling for promoting osteogenesis, thereby justifying the observed results and underlying signaling mechanisms of this study [51-55]. It is possible, however, that other factors, such as mechanical properties or nanostructure, played a role in the osteoinductive response, but these are unlikely to account for the observed differences in this study. Specifically, as demonstrated previously in our work, all of the PAs display the same structural formation of multilayered nanofibers approximately 8-10 nm in diameter and are able to maintain scaffold integrity for up to a month, even with the presence of an enzyme degradable sequence [19, 22]. Therefore, the specific ligand functionality of the PAs provides promising osteoinductive signaling that can potentially be exploited for in vivo bone tissue applications.

While this study demonstrated the synergistic enhancement of osteogenic differentiation by combining PAs with conditioned media, creating biomaterials independent of outside supplements for clinical effectiveness would offer a great advantage for osteogenic regenerative therapies. From this study, evidence supporting the osteoinductive potential of PA-RGDS without supplemental aid was demonstrated. Visible levels of ALP activity were produced on the PA-RGDS coating cultured only in normal growth media, and the gene expression values were very similar to the control surfaces aided by conditioned media, or in the case of OCN, even able to exceed the expressed amount. However, continued development of this potential bone tissue engineering solution is still needed to ensure promoted osteogenesis independent of exogenous stimulation, which would enable clinically relevant in vivo applications. This need is further rationalized by the physiological problems that can accompany the use of osteogenic supplements and are often difficult to overcome. Specifically, supraphysiological levels of β-glycerol phosphate can cause an overabundance of mineralization, resulting in dystrophic calcification, reduced matrix formation, and even cell death [56, 57]. For dexamethasone, its ability to promote enhanced osteogenic differentiation is unquestioned, but this often occurs at the expense of marked decreases in cell number [58, 59]. Additionally, prolonged exposure to high levels of glucocorticoids, such as dexamethasone, is associated with skeletal abnormalities and a major cause of osteoporosis [60-62]. Therefore, if similar therapeutic effectiveness can be obtained, it would be more beneficial to remove the osteogenic supplements altogether, even if some additional time is required for differentiation.

Based on this study and our previous work, the potential for ligand driven osteogenic differentiation as facilitated through the nanofibrous PA scaffold does exist, albeit at a slower rate and not to the same phenotypic level when combined with conditioned media. Hence, there is significant room for improvement to develop this biomaterial for bone tissue engineering without the need of exogenous factors for osteoinduction. However, with further investigations, the versatility of the osteoinductive PAs, especially containing the RGDS ligand, holds great promise for future bone tissue regenerative therapies. The self-assembling nature of the molecule allows for the potential use of PAs as a bioactive coating for orthopedic implants that is effective under physiological conditions. Furthermore, the biological functionality could potentially be enhanced by combining two or more bioactive ligands within the PA molecules, investigating osteogenic pathway mechanisms initiated by the supplements to be incorporated into PA signaling, or adapting binding motifs within the internal peptide structure to deliver therapeutic growth factors. It would be particularly interesting to study the effects of combining the RGDS and DGEA ligands within the same PA scaffold.

5. Conclusions

Biomedical therapies for bone tissue engineering are challenged to recapitulate the native osteoinductive properties of bone ECM. To overcome these limitations, PAs have been developed as an ECM analogous biomaterial to concurrently provide biochemical signaling and nanostructural assembly, thereby creating a biomimetic environment with an instructive capacity for regeneration at the cellular level. In this study, different ligand signals were inscribed into PAs, and the osteoinductivity was investigated with or without conditioned media containing osteogenic supplements. It was found that the osteogenic differentiation of hMSCs was synergistically enhanced by culturing ligand-functionalized PAs in combination with conditioned media, as greater phenotypic expression was observed for both the RGDS and DGEA ligand signals. Osteoinductive potential was also demonstrated independently of stimulatory aid on the RGDS-modified PA, albeit not to the same phenotypic levels as the supplemented scaffolds. Despite the delayed osteoinduction, biomaterials capable of guiding osteogenic differentiation mediated exclusively by synthetic cell-ligand interactions would offer a great clinical advantage under physiological conditions because exogenous factors are not available in vivo. Therefore, PAs offer a promising regenerative tool that emphasizes a biomimetic approach for the continued development of bone tissue engineering solutions.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to acknowledge the Mass Spectrometry/Proteomics Shared facility at UAB for analyzing all the PA samples. Special thanks are also extended to Dr. Ralph Sanderson for use of his real-time PCR lab facilities, along with Dr. Vishnu Ramani and Dr. Anurag Purushothaman for invaluable help and discussion for all of the PCR experiments. This work was supported by the Wallace H. Coulter Foundation and the NSF CAREER awarded to H.W.J., along with funding from NIH T32 predoctoral training grant (NIBIB #EB004312-01) and Ruth L. Kirschstein National Research Service Award Individual Fellowship (1F31DE021286-01) for J.M.A.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Rosso F, Giordano A, Barbarisi M, Barbarisi A. From cell-ECM interactions to tissue engineering. Journal of cellular physiology. 2004;199:174–80. doi: 10.1002/jcp.10471. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Streuli C. Extracellular matrix remodelling and cellular differentiation. Curr Opin Cell Biol. 1999;11:634–40. doi: 10.1016/s0955-0674(99)00026-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kleinman HK, Philp D, Hoffman MP. Role of the extracellular matrix in morphogenesis. Curr Opin Biotechnol. 2003;14:526–32. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2003.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lutolf MP, Hubbell JA. Synthetic biomaterials as instructive extracellular microenvironments for morphogenesis in tissue engineering. Nature biotechnology. 2005;23:47–55. doi: 10.1038/nbt1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bernhardt A, Lode A, Mietrach C, Hempel U, Hanke T, Gelinsky M. In vitro osteogenic potential of human bone marrow stromal cells cultivated in porous scaffolds from mineralized collagen. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2009;90:852–62. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.32144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giannoudis PV, Dinopoulos H, Tsiridis E. Bone substitutes: an update. Injury. 2005;36(Suppl 3):S20–7. doi: 10.1016/j.injury.2005.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hamada K, Hirose M, Yamashita T, Ohgushi H. Spatial distribution of mineralized bone matrix produced by marrow mesenchymal stem cells in self-assembling peptide hydrogel scaffold. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2008;84:128–36. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.31439. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Li WJ, Tuli R, Huang X, Laquerriere P, Tuan RS. Multilineage differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells in a three-dimensional nanofibrous scaffold. Biomaterials. 2005;26:5158–66. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mauney JR, Kirker-Head C, Abrahamson L, Gronowicz G, Volloch V, Kaplan DL. Matrix-mediated retention of in vitro osteogenic differentiation potential and in vivo bone-forming capacity by human adult bone marrow-derived mesenchymal stem cells during ex vivo expansion. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2006;79:464–75. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30876. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mistry AS, Mikos AG. Tissue engineering strategies for bone regeneration. Advances in biochemical engineering/biotechnology. 2005;94:1–22. doi: 10.1007/b99997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhou Y, Chen F, Ho ST, Woodruff MA, Lim TM, Hutmacher DW. Combined marrow stromal cell-sheet techniques and high-strength biodegradable composite scaffolds for engineered functional bone grafts. Biomaterials. 2007;28:814–24. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.09.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Battista S, Guarnieri D, Borselli C, Zeppetelli S, Borzacchiello A, Mayol L, et al. The effect of matrix composition of 3D constructs on embryonic stem cell differentiation. Biomaterials. 2005;26:6194–207. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Colter DC, Class R, DiGirolamo CM, Prockop DJ. Rapid expansion of recycling stem cells in cultures of plastic-adherent cells from human bone marrow. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2000;97:3213–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.070034097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Friedenstein AJ, Chailakhyan RK, Latsinik NV, Panasyuk AF, Keiliss-Borok IV. Stromal cells responsible for transferring the microenvironment of the hemopoietic tissues. Cloning in vitro and retransplantation in vivo. Transplantation. 1974;17:331–40. doi: 10.1097/00007890-197404000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pereira RF, Halford KW, O'Hara MD, Leeper DB, Sokolov BP, Pollard MD, et al. Cultured adherent cells from marrow can serve as long-lasting precursor cells for bone, cartilage, and lung in irradiated mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995;92:4857–61. doi: 10.1073/pnas.92.11.4857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hartgerink JD, Beniash E, Stupp SI. Self-assembly and mineralization of peptide-amphiphile nanofibers. Science (New York, NY. 2001;294:1684–8. doi: 10.1126/science.1063187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jun HW, Paramonov SE, Hartgerink JD. Biomimetic Self-Assembled Nanofibers. Soft Matter. 2006;2:177–81. doi: 10.1039/b516805h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hartgerink JD, Beniash E, Stupp SI. Peptide-amphiphile nanofibers: a versatile scaffold for the preparation of self-assembling materials. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:5133–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.072699999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Jun HW, Yuwono V, Paramonov SE, Hartgerink JD. Enzyme-mediated degradation of peptide-amphiphile nanofiber networks. Adv Mater. 2005;17:2612–7. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lowik DWPM, Hest JCMv. Peptide based amphiphiles. Chem Soc Rev. 2004;33:234–45. doi: 10.1039/b212638a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stendahl JC, Rao MS, Guler MO, Stupp SI. Intermolecular forces in the self-assembly of peptide amphiphile nanofibers. Adv Funct Mater. 2006;16:499–508. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Anderson JM, Kushwaha M, Tambralli A, Bellis SL, Camata RP, Jun HW. Osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells directed by extracellular matrix-mimicking ligands in a biomimetic self-assembled peptide amphiphile nanomatrix. Biomacromolecules. 2009;10:2935–44. doi: 10.1021/bm9007452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Andukuri A, Minor WP, Kushwaha M, Anderson JM, Jun HW. Effect of endothelium mimicking self-assembled nanomatrices on cell adhesion and spreading of human endothelial cells and smooth muscle cells. Nanomedicine. 2010;6:289–97. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2009.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim JK, Anderson J, Jun HW, Repka MA, Jo S. Self-assembling peptide amphiphile-based nanofiber gel for bioresponsive cisplatin delivery. Molecular pharmaceutics. 2009;6:978–85. doi: 10.1021/mp900009n. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kushwaha M, Anderson JM, Bosworth CA, Andukuri A, Minor WP, Lancaster JR, Jr., et al. A nitric oxide releasing, self assembled peptide amphiphile matrix that mimics native endothelium for coating implantable cardiovascular devices. Biomaterials. 2010;31:1502–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2009.10.051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tambralli A, Blakeney B, Anderson J, Kushwaha M, Andukuri A, Dean D, et al. A hybrid biomimetic scaffold composed of electrospun polycaprolactone nanofibers and self-assembled peptide amphiphile nanofibers. Biofabrication. 2009;1:025001. doi: 10.1088/1758-5082/1/2/025001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pierschbacher MD, Ruoslahti E. Cell attachment activity of fibronectin can be duplicated by small synthetic fragments of the molecule. Nature. 1984;309:30–3. doi: 10.1038/309030a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ruoslahti E. RGD and other recognition sequences for integrins. Annual review of cell and developmental biology. 1996;12:697–715. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.12.1.697. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hosseinkhani H, Hosseinkhani M, Tian F, Kobayashi H, Tabata Y. Osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells in self-assembled peptide-amphiphile nanofibers. Biomaterials. 2006;27:4079–86. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2006.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Shin H, Temenoff JS, Bowden GC, Zygourakis K, Farach-Carson MC, Yaszemski MJ, et al. Osteogenic differentiation of rat bone marrow stromal cells cultured on Arg-Gly-Asp modified hydrogels without dexamethasone and beta-glycerol phosphate. Biomaterials. 2005;26:3645–54. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.09.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Yang F, Williams CG, Wang DA, Lee H, Manson PN, Elisseeff J. The effect of incorporating RGD adhesive peptide in polyethylene glycol diacrylate hydrogel on osteogenesis of bone marrow stromal cells. Biomaterials. 2005;26:5991–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2005.03.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Harbers GM, Healy KE. The effect of ligand type and density on osteoblast adhesion, proliferation, and matrix mineralization. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2005;75:855–69. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30482. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mizuno M, Fujisawa R, Kuboki Y. Type I collagen-induced osteoblastic differentiation of bone-marrow cells mediated by collagen-alpha2beta1 integrin interaction. Journal of cellular physiology. 2000;184:207–13. doi: 10.1002/1097-4652(200008)184:2<207::AID-JCP8>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mizuno M, Kuboki Y. Osteoblast-related gene expression of bone marrow cells during the osteoblastic differentiation induced by type I collagen. J Biochem. 2001;129:133–8. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.jbchem.a002824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kimelman N, Pelled G, Helm GA, Huard J, Schwarz EM, Gazit D. Review: gene- and stem cell-based therapeutics for bone regeneration and repair. Tissue engineering. 2007;13:1135–50. doi: 10.1089/ten.2007.0096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jaiswal N, Haynesworth SE, Caplan AI, Bruder SP. Osteogenic differentiation of purified, culture-expanded human mesenchymal stem cells in vitro. Journal of cellular biochemistry. 1997;64:295–312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prockop DJ, Phinney DG, Bunnell BA. Mesenchymal stem cells : methods and protocols. Humana Press; Totowa, NJ: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Schmittgen TD, Livak KJ. Analyzing real-time PCR data by the comparative C(T) method. Nature protocols. 2008;3:1101–8. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2008.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kulterer B, Friedl G, Jandrositz A, Sanchez-Cabo F, Prokesch A, Paar C, et al. Gene expression profiling of human mesenchymal stem cells derived from bone marrow during expansion and osteoblast differentiation. BMC Genomics. 2007;8:70. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-70. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Satija NK, Gurudutta GU, Sharma S, Afrin F, Gupta P, Verma YK, et al. Mesenchymal stem cells: molecular targets for tissue engineering. Stem Cells Dev. 2007;16:7–23. doi: 10.1089/scd.2006.9998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stein GS, Lian JB, van Wijnen AJ, Stein JL, Montecino M, Javed A, et al. Runx2 control of organization, assembly and activity of the regulatory machinery for skeletal gene expression. Oncogene. 2004;23:4315–29. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207676. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bruder SP, Jaiswal N, Haynesworth SE. Growth kinetics, self-renewal, and the osteogenic potential of purified human mesenchymal stem cells during extensive subcultivation and following cryopreservation. Journal of cellular biochemistry. 1997;64:278–94. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-4644(199702)64:2<278::aid-jcb11>3.0.co;2-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Behravesh E, Mikos AG. Three-dimensional culture of differentiating marrow stromal osteoblasts in biomimetic poly(propylene fumarate-co-ethylene glycol)-based macroporous hydrogels. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2003;66:698–706. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Evangelista MB, Hsiong SX, Fernandes R, Sampaio P, Kong HJ, Barrias CC, et al. Upregulation of bone cell differentiation through immobilization within a synthetic extracellular matrix. Biomaterials. 2007;28:3644–55. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2007.04.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.He X, Ma J, Jabbari E. Effect of grafting RGD and BMP-2 protein-derived peptides to a hydrogel substrate on osteogenic differentiation of marrow stromal cells. Langmuir. 2008;24:12508–16. doi: 10.1021/la802447v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hu Y, Winn SR, Krajbich I, Hollinger JO. Porous polymer scaffolds surface-modified with arginine-glycine-aspartic acid enhance bone cell attachment and differentiation in vitro. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2003;64:583–90. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.10438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Shin H, Zygourakis K, Farach-Carson MC, Yaszemski MJ, Mikos AG. Modulation of differentiation and mineralization of marrow stromal cells cultured on biomimetic hydrogels modified with Arg-Gly-Asp containing peptides. J Biomed Mater Res A. 2004;69:535–43. doi: 10.1002/jbm.a.30027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Datta N, Holtorf HL, Sikavitsas VI, Jansen JA, Mikos AG. Effect of bone extracellular matrix synthesized in vitro on the osteoblastic differentiation of marrow stromal cells. Biomaterials. 2005;26:971–7. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2004.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Hersel U, Dahmen C, Kessler H. RGD modified polymers: biomaterials for stimulated cell adhesion and beyond. Biomaterials. 2003;24:4385–415. doi: 10.1016/s0142-9612(03)00343-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Kundu AK, Khatiwala CB, Putnam AJ. Extracellular matrix remodeling, integrin expression, and downstream signaling pathways influence the osteogenic differentiation of mesenchymal stem cells on poly(lactide-co-glycolide) substrates. Tissue Eng Part A. 2009;15:273–83. doi: 10.1089/ten.tea.2008.0055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hamidouche Z, Fromigue O, Ringe J, Haupl T, Vaudin P, Pages JC, et al. Priming integrin alpha5 promotes human mesenchymal stromal cell osteoblast differentiation and osteogenesis. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2009;106:18587–91. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0812334106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Mould AP, Askari JA, Humphries MJ. Molecular basis of ligand recognition by integrin alpha 5beta 1. I. Specificity of ligand binding is determined by amino acid sequences in the second and third NH2-terminal repeats of the alpha subunit. The Journal of biological chemistry. 2000;275:20324–36. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000572200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Salasznyk RM, Klees RF, Hughlock MK, Plopper GE. ERK signaling pathways regulate the osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells on collagen I and vitronectin. Cell communication & adhesion. 2004;11:137–53. doi: 10.1080/15419060500242836. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Suzawa M, Tamura Y, Fukumoto S, Miyazono K, Fujita T, Kato S, et al. Stimulation of Smad1 transcriptional activity by Ras-extracellular signal-regulated kinase pathway: a possible mechanism for collagen-dependent osteoblastic differentiation. J Bone Miner Res. 2002;17:240–8. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.2002.17.2.240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Takeuchi Y, Suzawa M, Kikuchi T, Nishida E, Fujita T, Matsumoto T. Differentiation and transforming growth factor-beta receptor down-regulation by collagen-alpha2beta1 integrin interaction is mediated by focal adhesion kinase and its downstream signals in murine osteoblastic cells. The Journal of biological chemistry. 1997;272:29309–16. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.46.29309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gronowicz G, Woodiel FN, McCarthy MB, Raisz LG. In vitro mineralization of fetal rat parietal bones in defined serum-free medium: effect of beta-glycerol phosphate. J Bone Miner Res. 1989;4:313–24. doi: 10.1002/jbmr.5650040305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Roach HI. Induction of normal and dystrophic mineralization by glycerophosphates in long-term bone organ culture. Calcified tissue international. 1992;50:553–63. doi: 10.1007/BF00582172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Chen TL. Inhibition of growth and differentiation of osteoprogenitors in mouse bone marrow stromal cell cultures by increased donor age and glucocorticoid treatment. Bone. 2004;35:83–95. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2004.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Walsh S, Jordan GR, Jefferiss C, Stewart K, Beresford JN. High concentrations of dexamethasone suppress the proliferation but not the differentiation or further maturation of human osteoblast precursors in vitro: relevance to glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. Rheumatology (Oxford, England) 2001;40:74–83. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/40.1.74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Canalis E. Clinical review 83: Mechanisms of glucocorticoid action in bone: implications to glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis. The Journal of clinical endocrinology and metabolism. 1996;81:3441–7. doi: 10.1210/jcem.81.10.8855781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Ishida Y, Heersche JN. Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis: both in vivo and in vitro concentrations of glucocorticoids higher than physiological levels attenuate osteoblast differentiation. J Bone Miner Res. 1998;13:1822–6. doi: 10.1359/jbmr.1998.13.12.1822. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tobias JH. Management of steroid-induced osteoporosis: what is the current state of play? Rheumatology (Oxford, England) 1999;38:198–201. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/38.3.198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]