Abstract

According to sociometer theory, self-esteem serves as a barometer of the extent to which individuals are socially included or excluded by others. We hypothesized that trait self-esteem would be related to social pain responsiveness, and we used functional magnetic resonance imaging to experimentally investigate this potential relationship. Participants (n = 26) performed a cyberball task, a computerized game of catch during which the participants were excluded from the game. Participants then rated the degree of social pain experienced during both inclusion in and exclusion from the game. Individuals with lower trait self-esteem reported increased social pain relative to individuals with higher trait self-esteem, and such individuals also demonstrated a greater degree of dorsal anterior cingulate cortex activation. A psychophysiological interaction analysis revealed a positive connectivity between the dorsal anterior cingulate and prefrontal cortices for the lower trait self-esteem group, and a corresponding negative connectivity for the higher trait self-esteem group. Heightened dorsal anterior cortex activity and a corresponding connection with the prefrontal cortex might be one possible explanation for the greater levels of social pain observed experienced by individuals with low trait self-esteem.

Keywords: self-esteem, social pain, anterior cingulate cortex, fMRI

People’s thoughts and feelings about themselves in part reflect how they believe they are perceived and evaluated by others (Shraugher and Schoeneman, 1979). This is presumably true both in the moment (as others’ perceived reactions have an immediate effect on self-relevant feelings or state self-esteem) and over time (in the form of a cumulative history of evaluation related to self-concept or trait self-esteem). Leary and colleagues proposed a model of self-esteem that directly accounts for the link between this concept and interpersonal appraisals (Leary et al., 1995; Leary and Baumeister, 2000). According to sociometer theory, others’ reactions exert a strong effect on self-esteem because the self-esteem system itself serves as a subjective monitor or gauge of the degree to which the individual is being included and accepted versus excluded or rejected by other people. Because social inclusion and relationships are essential for good physical and psychological heath, human beings presumably evolved a fundamental motive to maintain some degree of connectedness with other people (Ainsworth, 1989; Leary et al., 1995; Eisenberger and Lieberman, 2004; Macdonald and Leary, 2005). At the same time, successful maintenance of one’s interpersonal relationships would require a mechanism whereby the quality of one’s relationships vis-à-vis inclusion and exclusion could be monitored. Such a system would monitor the social environment for cues that connote exclusion, rejection, and ostracism, alerting the individual to potential threat by means of lowered state self-esteem when such cues are detected.

According to this proposal, people should feel worse about themselves on days when they feel excluded from others relative to days when they feel included. These fluctuations have been shown to occur within a context of relatively stable baseline levels of trait self-esteem that differ across people. According to Leary and Baumeister (2000), this trait self-esteem is related to past experiences of being rejected or included, and is also associated with people’s potential for social inclusion according to their standing on various socially desirable traits, including physical attractiveness and intelligence (Anthony et al., 2007). In an online diary study that employed cross-lagged analysis, people who reported lower quality relationships with family members, friends and romantic partners had lower levels of trait self-esteem (Denissen et al., 2008). This evidence supports the sociometer theory notion that trait self-esteem is dependent upon an individual’s history of acceptance and rejection, which is itself reflected in the overall quality of their social relationships.

Some studies suggest that trait self-esteem is related to the nature of an individual’s cognitions in social situations. Leary et al. (1995) reported that trait self-esteem is negatively correlated with perceived exclusionary status, suggesting that people with low trait self-esteem may be more likely to perceive others’ reactions as indicative of rejection, relative to people with higher trait self-esteem. In another study (Leary, 2002), participants were asked to write an essay about being rejected by someone they cared about. Participants with low trait self-esteem experienced more anxiety during this task than did those with higher trait self-esteem. This result suggests that individuals with lower trait self-esteem show stronger affective responses to social exclusion than those with higher trait self-esteem, even when the nature of the social exclusion situation is held constant.

Social pain is a specific negative emotional reaction to the perception that one is being excluded from desired relationships or is being devalued by desired relationship partners or groups (Macdonald and Leary, 2005). Exclusion may be the result of any number of factors, including rejection, death of a loved one or forced separation. Neuroscience studies have used various tasks to induce social pain. The task most frequently used is dubbed the ‘cyberball’ task, which is a virtual game of catch played on a computer (although participants may believe that they are playing with other people over a network) (Williams and Jarvis, 2006). Recently, Eisenberger and her colleagues (2003) used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to determine which brain regions are active when participants are socially excluded during a cyberball task. A significant increase in dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC) activation was observed during social exclusion, and degree of self-reported social distress was significantly correlated with this increase in dACC activity. This result suggests that the dACC plays an important role in the perception of social pain. Physical and social pain may share a neurobiological basis (Eisenberger and Lieberman, 2004; Macdonald and Leary, 2005), as the dACC also appears to be involved in the experience of physical pain (Price, 2000; Rainville, 2002; Rainville et al., 1997). Furthermore, perceptions of daily social support are related to the degree of dACC activity that is observed during social exclusion (Eisenberger et al., 2007). Individuals in a cyberball task study who interacted regularly with supportive individuals over a 10-day period showed diminished dACC activity during social exclusion, relative to individuals who reported lower levels of daily social support. This finding suggests that degree of daily social inclusion has an effect on subsequent responsiveness to any instances of social exclusion that may occur. Because the quality of one’s social relationships affects trait self-esteem (Denissen et al., 2008), trait self-esteem may itself serve to moderate the experience of social pain.

Our previous research has found dACC activity to be positively correlated with the degree of self-reported social distress experienced during a game of cyberball (Onoda et al., 2009). The cyberball task is thought to reflect a milder form of exclusion than that which might be experienced while interacting with real people, although one study reported that participants who were excluded during a computer-based task felt a degree of social pain that was comparable to that felt by participants who were excluded by actual people (Zadro et al., 2004). In human society, exclusion can lead to various difficulties, including loss of contact with important others or loss of other resources (Macdonald and Leary, 2005). Zadaro et al. (2004) interpreted their result as strong evidence for a primitive and automatic adaptive sensitivity to even the slightest hint of social exclusion.

According to sociometer theory (Leary et al., 1995; Leary, 2002), people with lower trait self-esteem should show higher levels of social pain and corresponding dACC activity during social exclusion, as compared to people with higher trait self-esteem. This possibility has yet to be tested. We examined the relationship between trait self-esteem and the effects of social exclusion on both self-reported social pain and underlying brain mechanisms. Furthermore, we used psychophysiological interaction analysis to perform an exploratory investigation of the functional connectivities between the dACC and other brain regions during social exclusion.

METHODS

The current study involved an analysis of the same data set as that collected and analyzed in our previous fMRI study (Onoda et al., 2009). Therefore, the experimental procedures were of course identical, although the aim of the present study and the analyses described here are independent of and unrelated to this previous work.

Participants

Twenty-six healthy students (11 males, 15 females; mean age = 21.7 ± 1.3 years; range = 20–25 years; all right-handed) participated in the experiment. They were paid 2000 yen (∼17 USD) each for their participation.

Questionnaire session

All participants completed some questionnaires before the fMRI session began. The Rosenberg self-esteem scale (Rosenberg, 1965; Yamamoto et al., 1982) asks respondents to indicate (on a 5-point scale) how much they agree with each of 10 statements that pertain to their general feelings about themselves, over the last few months (1: strongly disagree, 5: strong agree; trait self-esteem score range = 10–50 points). Trait self-esteem scores were then used to divide the participants into two groups. Based on a median split (median = 39), the upper 50% of the participants were defined as the high trait self-esteem group, with the lower 50% being assigned to the low trait self-esteem group. Other questionnaires administered included the Temperament and Character Inventory and Beck Depression Inventory, although these scores were not examined for the purposes of the present study.

fMRI session

Participants were initially told that the experimenters were interested in the neural mechanisms that underlie random decision-making, and that they would be playing a virtual ball-tossing game with computer players. Participants saw a ball, two virtual computer players on the left and right sides of the screen, an arm representing the participant on the lower center portion of the screen, and a message at the top of the screen. The computer players automatically threw the ball to each other or to the participant, waiting 1.0–2.0 s between throws. The participant could return the ball to one of the computer players by pressing one of two keys on a button box.

The fMRI task consisted of nine blocks (duration of ∼50 s per block and 20 s rest periods between each block). The first three blocks comprised the social inclusion condition, during which participants received six or seven throws per block. The next three blocks comprised the social exclusion condition, during which participants received just one or two throws. In the social inclusion and exclusion conditions, the messages provided to participants consisted of experimental instructions. The last three blocks constituted the emotional support condition. These blocks were used to examine another research question and were not relevant for present purposes (refer to Onoda et al., 2009 for more information). Upon completion of the virtual game, participants completed questionnaires to assess social pain (Williams et al., 2000). Each questionnaire retrospectively assessed participants’ subjective experiences during each condition of the cyberball task (‘I felt liked.’, ‘I felt rejected.’, ‘I felt invisible.’, ‘I felt powerful.’).

fMRI data acquisition

A Siemens AG 1.5 T scanner was used to acquire imaging data. A time-course series of 168 volumes per participant was acquired with echo planar imaging sequences [repetition time (TR) = 4000 ms, echo time (TE) = 48 ms, field of view (FOV) = 256 mm, matrix size = 128 × 128, 38 slices, thick = 4 mm, flip angle = 90)]. Functional scans lasted 10 min and 50 s, including a pre-baseline interval (20 s). After functional scanning, structural scans were acquired using T1-weighted gradient echo pulse sequences (TR = 12 ms, TE = 4.5 ms, FOV = 256 mm, flip angle = 20).

fMRI data analysis

Imaging data were analyzed using SPM5 software (Wellcome Department of Cognitive Neurology, London, UK). The first three volumes of each fMRI run were discarded because the MRI signal was unsteady. Slice timing correction was performed for each set of functional volumes. Each set was realigned to the first volume, spatially normalized to a standard template based upon the Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) reference brain, and smoothed using an 8-mm full width at half maximum Gaussian kernel. A mixed design was modeled, with the regressors of (block-designed) social inclusion vs exclusion, and (event-related designed) response movement (deciding which character to throw the ball toward). The durations of the social inclusion and exclusion instars were set at ∼50 s. Because number of responses differed across the two conditions, the activation related to the response movements was separated independently.

Random effects analyses of group were conducted using the contrast images generated for each participant. First, a comparison of high and low trait self-esteem groups was performed via whole-brain two-sampled t-tests (contrast between social exclusion and inclusion). The statistical threshold for these t-tests was set at an uncorrected P < .005 and a cluster level of P < .05. All coordinates are reported in MNI coordinate space.

Psychophysiological interaction (PPI) analysis (Friston et al., 1997) captures correlations between brain regions in relation to the experimental paradigm. The seed region was a 6 mm sphere in the dACC, which was the peak area of activation identified in a preceding comparison of brain activity between high and low trait self-esteem groups (see Results section). The first eigenvariate time series for the seed region was extracted for each participant. The individual PPI images obtained during the social exclusion condition were used to perform a random effect analysis using whole-brain two sampled t-test. The estimated connectivity was represented as a t-value, with a positive t-value representing a positive correlation between the seed region and the other region of interest. In the present study, PPI analysis was used to reveal differences in terms of the condition-specific contribution of one area to another during social exclusion. The threshold of the PPI analysis was set at an uncorrected P < .005 and a voxel size of >10.

RESULTS

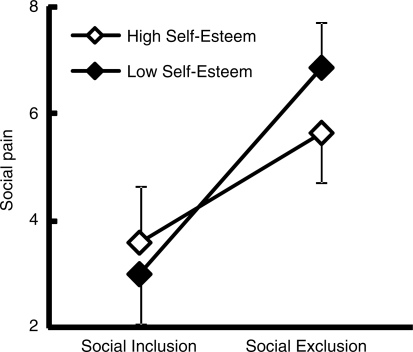

We next divided the participants into two groups according trait self-esteem scores. Mean scores on the trait self-esteem scale were 42.5 ± 2.5 and 34.9 ± 3.0 for the high and low trait self-esteem groups, respectively. There were no differences between the two groups in terms of age (high: 21.7 ± 1.4, low: 21.6 ± 1.2) or gender ratio (high: male/female = 5/8, low: 6/7). Figure 1 shows changes in social pain scores for each trait self-esteem group. A mixed analysis of variance (ANOVA) with trait self-esteem (high versus low) as a between-group factor and experimental condition (social inclusion vs exclusion) as a within-group factor was performed on self-reported social pain. There was a significant main effect of condition, F(1,24) = 114.8, P < 0.0001, and the two-way interaction between condition and trait self-esteem was also significant, F(1,24) = 10.8, P < 0.05. Bonferroni-corrected post hoc tests revealed that social pain scores were larger in the social exclusion condition than in the inclusion condition for both groups (P’s < 0.001), and that social pain scores in the social exclusion condition were larger in the low trait self-esteem group than in the high trait self-esteem group (P < 0.01).

Fig. 1.

Social pain during inclusion and exclusion in high and low self-esteem groups.

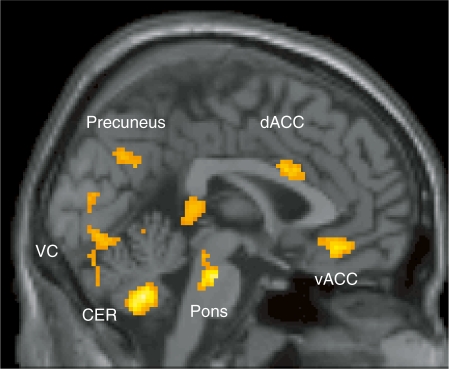

Table 1 summarizes activation differences between the high and low trait self-esteem groups, for the contrast of social exclusion minus inclusion. The low trait self-esteem group showed more activation in the dACC, ventral anterior cingulate cortex (vACC), ventral medial prefrontal cortex (MPFC), right insula, left premotor cortex, left inferior parietal lobule, bilateral occipitotemporal cortex, precuneus, visual cortex, right hippocampus, bilateral parahippocampal gyrus, left thalamus, cerebellum and pons, relative to the high trait self-esteem group. Figure 2 shows the midline sagittal plane for the contrast of the low minus high trait self-esteem group. No brain region showed greater activation in the high trait self-esteem group relative to the low trait self-esteem group.

Table 1.

Comparison of brain activation during social exclusion between high and low self-esteem groups (statistical criteria: uncorrected P < 0.005 and cluster level P < 0.05)

| Brain region | x | y | z | Size | t |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High > Low trait self-esteem | |||||

| No regions | |||||

| Low > High trait self-esteem | |||||

| dACC (24/33) | 0 | 12 | 26 | 122 | 3.8 |

| vACC(32)/vMPFC (11) | 6 | 40 | −16 | 306 | 4.6 |

| Right insula (13) | 32 | 6 | 18 | 200 | 5.3 |

| Left premotor cortex (6) | −22 | −8 | 68 | 356 | 4.4 |

| Left IPL (40) | −56 | −32 | 34 | 131 | 4.6 |

| Left OTC (19/39) | −44 | −76 | 10 | 250 | 4.7 |

| Right OTC (19/39) | 44 | −80 | 26 | 604 | 5.5 |

| Precuneus (7/31) | −6 | −68 | 30 | 514 | 4.2 |

| Right visual cortex (19) | 14 | −82 | 28 | 153 | 4.1 |

| Right hippocampus | 34 | −30 | −12 | 5780 | 4.9 |

| Right PHG (35/36) | 34 | −26 | −24 | – | 4.8 |

| Left PHG (35/36) | −34 | −34 | −22 | – | 4.3 |

| Left thalamus | −10 | −28 | 6 | – | 6.1 |

| Cerebellum | 6 | −56 | −38 | – | 5.1 |

| Pons | 2 | −24 | −26 | 238 | 5.2 |

vMPFC, ventral medial prefrontal cortex; IPL, inferior parietal lobule; OTC, occipitotemporal cortex; PHG, parahippocampal gryrus.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of brain activation between high and low self-esteem groups in contrast to social exclusion versus inclusion. The threshold for the whole brain two-sampled t-tests was set at uncorrected P < 0.005, and at voxel and cluster levels of P < 0.05. dACC, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex; vACC, ventral anterior cingulate cortex; VC, visual cortex; CER, cerebellum.

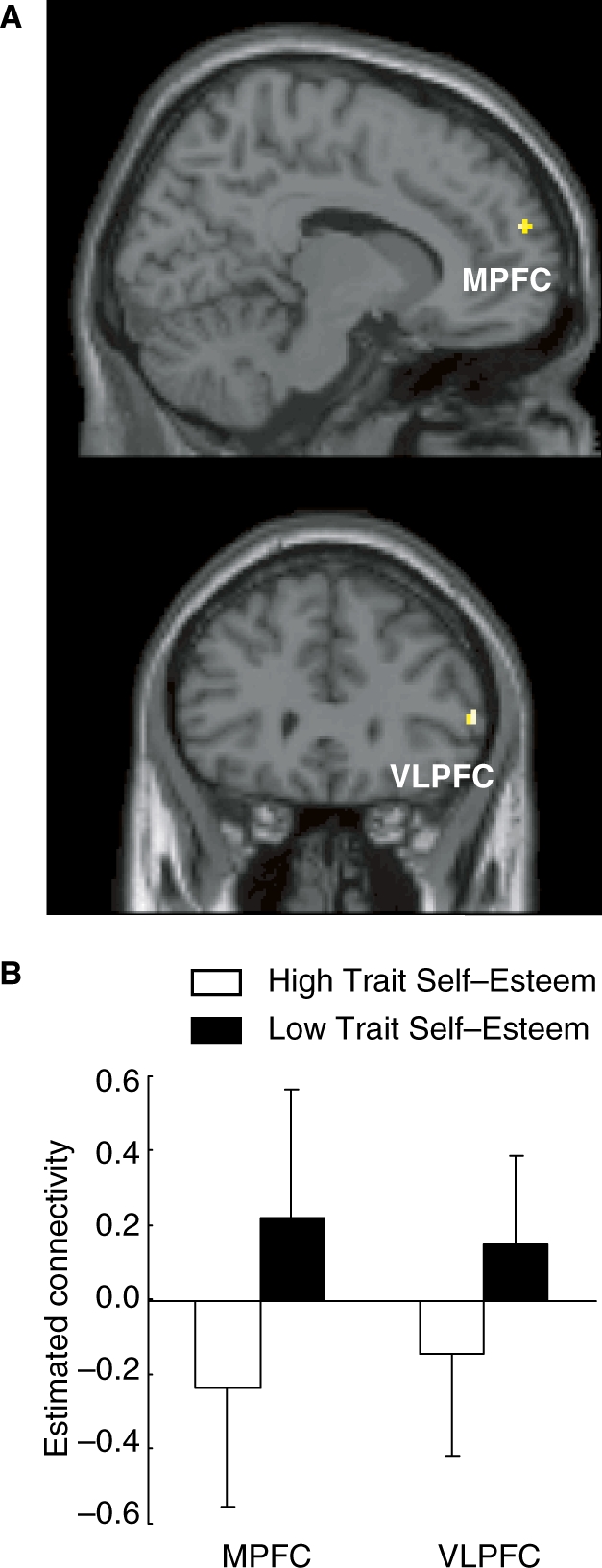

To evaluate functional connectivity differences between the high and low trait self-esteem groups, we performed a PPI analysis of brain activation during the social exclusion condition. The seed region for this analysis was the dACC. Table 2 summarizes the results of the PPI analysis. The right parahippocampal gyrus and left cerebellum showed relatively greater positive connectivities to the dACC for the high trait self-esteem group as compared to the low trait self-esteem group. Conversely, the right ventrolateral prefrontal cortex (VLPFC), right MPFC (Figure 3), left primary motor cortex, and right superior parietal lobule showed relatively greater positive connectivities for the low trait self-esteem group as compared to the high trait self-esteem group. To clarify whether the connectivity between the seed region and prefrontal cortex was positive or negative, the value of connectivity at the peak coordinate was statistically compared with zero. In the low trait self-esteem group, the connectivity between the dACC and MPFC and that between the dACC and right VLPFC were both significantly positive [t’s(12) > 2.34, P’s < .05]. Conversely, the connectivity between the dACC and MPFC in the high trait self-esteem group was significantly negative [t(12) = 2.89, P < .05].

Table 2.

Functional connectivity differences between high and low trait self-esteem groups during social exclusion (statistical criteria: uncorrected P < 0.005 and voxels >10)

| Brain region | x | y | z | Size | t |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High > Low trait self-esteem | |||||

| Right PHG (35) | 24 | −22 | 24 | 48 | 4.5 |

| Left cerebellum | −14 | −32 | −32 | 38 | 3.5 |

| Low > High trait self-esteem | |||||

| Right VLPFC (45) | 58 | 30 | 8 | 16 | 3.8 |

| Right MPFC (10) | 12 | 58 | 22 | 15 | 3.5 |

| Left PMC (6) | −36 | −4 | 44 | 25 | 3.5 |

| Right SPL (7) | 24 | −52 | 66 | 81 | 4.1 |

PMC, primary motor cortex; SPL, superior parietal lobule.

Fig. 3.

Comparison of functional connectivity with dorsal anterior cingulate cortex (dACC) between high and low self-esteem groups during social exclusion. (A) The threshold for the whole-brain two-sampled t-tests was set at uncorrected P < 0.005, and at voxel level and voxels >10. MPFC, medial prefrontal cortex; VLPFC, ventrolateral prefrontal cortex. (B) Estimated connectivity of MPFC and VLPFC with dACC.

DISCUSSION

The present study examined the relationship between trait self-esteem and the effects of exposure to social exclusion on social pain and dACC activity. We hypothesized that individuals with lower trait self-esteem would be more responsive to ostracism, relative to those individuals with higher trait self-esteem. As a consequence, self-reported social pain and dACC activity should both be higher for individuals with low trait self-esteem. This pattern is exactly what we found. Furthermore, we found significant connections between the dACC and a network that includes the PFC in the low trait self-esteem group. Low trait self-esteem appears to be related in the experience of social pain, and a connection between the dACC and PFC may underlie this relationship.

The current study employed a cyberball task to expose the participants to social inclusion and exclusion conditions. Our participants experienced social pain during exclusion, despite the knowledge that their partners during the virtual tossing game were not real persons. As discussed earlier, computer-based tasks can induce genuine feelings of exclusion (Zadaro et al., 2004). Human beings appear to have the ability to detect even fairly low levels of social exclusion.

The current study strongly suggests that responsiveness to social exclusion may be more predominant in people with lower trait self-esteem. Leary et al. (1995) reported a negative correlation between perceived exclusionary status and trait self-esteem. Furthermore, they found that participants with low trait self-esteem experienced more anxiety when they were asked to write an essay about being excluded (Leary, 2002). These findings are indicative of a significant relationship between trait self-esteem and the experience of social pain. The present study provides further evidence that supports a proposed relationship between trait self-esteem and social pain perception.

Sociometer theory (Leary et al., 1995; Leary and Baumeister, 2000) has two primary implications for understanding the interface between one’s self-esteem and one’s social world. First, the theory maintains that self-esteem is responsive to one’s social experiences. Specific instances of acceptance or rejection cause acute changes in the ‘state’ of one’s self-esteem (Leary et al., 1995). Second, the effects of acceptance or rejection likely accumulate over time, causing one to have chronically high or low ‘trait’ self-esteem. In an online diary study, people who described higher quality relationships with family, friends and romantic partners had higher levels of trait self-esteem (Denissen et al., 2008). Our findings and those of previous studies (Leary et al., 1995; Leary, 2002) support sociometer theory and suggest that the relationship between self-esteem and social experiences can be described as a loop.

We observed that people with lower trait self-esteem showed more dACC activity than did people with higher trait self-esteem. Previous work has shown that the dACC is activated in response to an episode of social rejection, and that the magnitude of dACC activity is correlated with the magnitude of self-reported social pain following exclusion (Eisenberger et al., 2003). In addition, social support appears to diminish neural reactivity associated with social distress, such that greater levels of social support are associated with diminished levels of dACC activity (Eisenberger et al., 2007). It therefore seems likely that daily social support may predict responsiveness to ostracism, as well as contributing to the formation of healthy levels of trait self-esteem. Considering sociometer theory and our results, the relationship between daily social support and degree of dACC activity may itself be moderated by trait self-esteem.

PPI analysis revealed that during social exclusion, the dACC has a positive functional connectivity with the MPFC in those individuals who have low trait self-esteem. MPFC activity has been noted in many studies of self-referential processing (Fossati et al., 2003; Moran et al., 2006; Yoshimura et al., 2009) and theory of mind (Gallagher et al., 2000; Gallagher et al., 2002; McCabe et al., 2001). The increased connectivity between the MPFC and dACC observed here may be involved in such intra- and inter-individual cognitive functioning.

It must also be noted that we found a functional connectivity between the right VLPFC and dACC in our low trait self-esteem group. According to one influential brain model of hemispheric asymmetry in emotional processing, negative emotions appear to be lateralized in the right prefrontal cortex, as demonstrated by functional brain imaging studies (Canli et al., 1998). Furthermore, the right VLPFC has been implicated in the regulation or inhibition of pain-related distress and negative affect (Hariri et al., 2000; Small et al., 2001; Petrovic et al., 2002; Eisenberger et al., 2003;). The primate homolog of the VLPFC has efferent connections to the region of the ACC associated with pain distress (Cavada et al., 2000), suggesting that the VLPFC may partially regulate the ACC. In the study of Eisenberger et al. (2003), VLPFC activity was negatively correlated with self-reported distress, and dACC changes mediated the VLPFC-distress correlation, suggesting that the VLPFC regulates the distress produced during social exclusion by disrupting dACC activity. The positive connectivity between the dACC and right VLPFC observed in the low trait self-esteem group studied here may suggest a failure on the part of the VLPFC to suppress dACC functioning.

Another important consideration is that vACC activity also differed between our high and low trait self-esteem groups, showing essentially the same pattern as the dACC. The vACC is responsive to social exclusion during adolescence (Masten et al., 2009) and to one’s perceptions of emotional support (Coan et al., 2006; Onoda et al., 2009). Furthermore, it should be noted that clinical research has identified greater levels of vACC activity in depression (Chen et al., 2007; Keedwell et al., 2009; Yoshimura et al., in press). The vACC may also therefore play an important role in the experience of social exclusion. However, previous studies have shown that the vACC is involved in more positive affective processes, including social acceptance (Somerville et al., 2006), lower sensitivities to facial rejection (Burklund, et al., 2007) and optimism (Sharot et al., 2007). The vACC seems to be involved in emotional processing regardless of the specific valence of the experienced emotion.

In conclusion, the current study revealed that trait self-esteem predicts responsiveness to ostracism and corresponding dACC activity, such that people with lower trait self-esteem show increased social pain and dACC activity relative to people with higher trait self-esteem. The observed dACC activity was itself associated with MPFC and VLPFC activity, and these brain connectivities underlie the social pain differences between groups. On the other hand, neuroticism (Boyes and French, 2009), social anxiety (Zadro et al., 2006), social status and gender (Bozin and Yoder, 2008) are also related to perceptions of social pain. It is necessary to examine the relationships between trait self-esteem and these variables.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by a grant-in-aid for scientific research (A) 19203030 and for young scientists (B) 20790843 from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science.

REFERENCES

- Ainsworth MD. Attachments beyond infancy. American Psychology. 1989;44:709–16. doi: 10.1037//0003-066x.44.4.709. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anthony DB, Holmes JG, Wood JV. Social acceptance and self-esteem: tuning the sociometer to interpersonal value. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2007;92:1024–39. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.92.6.1024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyes ME, French DJ. Having a cyberball: using a ball-throwing game as an experimental social stressor to examine the relationship between neuroticism and coping. Personality and Individual Differences. 2009;47:396–401. [Google Scholar]

- Bozin MA, Yoder JD. Social status, not gender alone, is implicated in different reactions by women and men to social ostracism. Sex Roles. 2008;58:713–720. [Google Scholar]

- Burklund LJ, Eisenberger NI, Lieberman MD. The face of rejection: rejection sensitivity moderates dorsal anterior cingulate activity to disapproving facial expressions. Social Neuroscience. 2007;2:238–53. doi: 10.1080/17470910701391711. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canli T, Desmond JE, Zhao Z, Glover G, Gabrieli JD. Hemispheric asymmetry for emotional stimuli detected with fMRI. Neuroreport. 1998;9:3233–9. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199810050-00019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavada C, Company T, Tejedor J, Cruz-Rizzolo RJ, Reinoso-Suarez F. The anatomical connections of the macaque monkey orbitofrontal cortex. A review. Cereb Cortex. 2000;10:220–42. doi: 10.1093/cercor/10.3.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen CH, Ridler K, Suckling J, et al. Brain imaging correlates of depressive symptom severity and predictors of symptom improvement after antidepressant treatment. Biological Psychiatry. 2007;62:407–14. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.09.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cloninger CR. A systematic method for clinical description and classification of personality variants. A proposal. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1987;44:573–88. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1987.01800180093014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coan JA, Schaefer HS, Davidson RJ. Lending a hand: social regulation of the neural response to threat. Psychological Science. 2006;17:1032–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9280.2006.01832.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Denissen JJ, Penke L, Schmitt DP, van Aken MA. Self-esteem reactions to social interactions: evidence for sociometer mechanisms across days, people, and nations. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2008;95:181–96. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.95.1.181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger NI, Lieberman MD. Why rejection hurts: a common neural alarm system for physical and social pain. Trends in Cognitive Sciences. 2004;8:294–300. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2004.05.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger NI, Lieberman MD, Williams KD. Does rejection hurt? An FMRI study of social exclusion. Science. 2003;302:290–2. doi: 10.1126/science.1089134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberger NI, Taylor SE, Gable SL, Hilmert CJ, Lieberman MD. Neural pathways link social support to attenuated neuroendocrine stress responses. Neuroimage. 2007;35:1601–12. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.01.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fossati P, Hevenor SJ, Graham SJ, et al. In search of the emotional self: an FMRI study using positive and negative emotional words. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2003;160:1938–45. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.160.11.1938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher HL, Happe F, Brunswick N, Fletcher PC, Frith U, Frith CD. Reading the mind in cartoons and stories: an fMRI study of 'theory of mind' in verbal and nonverbal tasks. Neuropsychologia. 2000;38:11–21. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(99)00053-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallagher HL, Jack AI, Roepstorff A, Frith CD. Imaging the intentional stance in a competitive game. Neuroimage. 2002;16:814–21. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hariri AR, Bookheimer SY, Mazziotta JC. Modulating emotional responses: effects of a neocortical network on the limbic system. Neuroreport. 2000;11:43–8. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200001170-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keedwell P, Drapier D, Surguladze S, Giampietro V, Brammer M, Phillips M. Neural markers of symptomatic improvement during antidepressant therapy in severe depression: subgenual cingulate and visual cortical responses to sad, but not happy, facial stimuli are correlated with changes in symptom score. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2009;23:775–88. doi: 10.1177/0269881108093589. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leary MR. The interpersonal basis of self-esteem: death, devaluation, or deference? In: Forgas JP, Williams KD, editors. The Social Self: Vonitive, Interpersonal, and Intergroup Perspective. New York: Psychology Press; 2002. pp. 143–59. [Google Scholar]

- Leary MR, Baumeister RF. The nature and function of self-esteem: sociometer theory. In: Zanna MP, editor. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology. 2000. , San Diego: Academic Press, Vol. 32, pp. 1–62. [Google Scholar]

- Leary MR, Tambor ES, Terdal SK, Downs DL. Self-esteem as an interpersonal monitor: the sociometer hypothesis. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 1995;68:518–30. [Google Scholar]

- Macdonald G, Leary MR. Why does social exclusion hurt? The relationship between social and physical pain. Psychological Bulletin. 2005;131:202–23. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.131.2.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Masten CL, Eisenberger NI, Borofsky LA, et al. Neural correlates of social exclusion during adolescence: understanding the distress of peer rejection. Social Cognitive and Affect Neuroscience. 2009;4:143–57. doi: 10.1093/scan/nsp007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCabe K, Houser D, Ryan L, Smith V, Trouard T. A functional imaging study of cooperation in two-person reciprocal exchange. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2001;98:11832–5. doi: 10.1073/pnas.211415698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran JM, Macrae CN, Heatherton TF, Wyland CL, Kelley WM. Neuroanatomical evidence for distinct cognitive and affective components of self. Journal of Cognitive Neuroscience. 2006;18:1586–94. doi: 10.1162/jocn.2006.18.9.1586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Onoda K, Okamoto Y, Nakashima K, Nittono H, Ura M, Yamawaki S. Decreased ventral anterior cingulate cortex activity is associated with reduced social pain during emotional support. Social Neuroscience. 2009;4:1–12. doi: 10.1080/17470910902955884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrovic P, Kalso E, Petersson KM, Ingvar M. Placebo and opioid analgesia—imaging a shared neuronal network. Science. 2002;295:1737–40. doi: 10.1126/science.1067176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Price DD. Psychological and neural mechanisms of the affective dimension of pain. Science. 2000;288:1769–72. doi: 10.1126/science.288.5472.1769. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainville P. Brain mechanisms of pain affect and pain modulation. Current Opinion in Neurobiology. 2002;12:195–204. doi: 10.1016/s0959-4388(02)00313-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rainville P, Duncan GH, Price DD, Carrier B, Bushnell MC. Pain affect encoded in human anterior cingulate but not somatosensory cortex. Science. 1997;277:968–71. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5328.968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg M. Society and the Adolescent Selfimage. Princeton: Princeton University Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Sharot T, Riccardi AM, Raio CM, Phelps EA. Neural mechanisms mediating optimism bias. Nature. 2007;450:102–5. doi: 10.1038/nature06280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shraugher JS, Schoeneman TJ. Symbolic interactionist view of the self-concept: through the looking glass darkly. Psychological Bulletin. 1979;86:549–73. [Google Scholar]

- Small DM, Zatorre RJ, Dagher A, Evans AC, Jones-Gotman M. Changes in brain activity related to eating chocolate: from pleasure to aversion. Brain. 2001;124:1720–33. doi: 10.1093/brain/124.9.1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Somerville LH, Heatherton TF, Kelley WM. Anterior cingulate cortex responds differentially to expectancy violation and social rejection. Nature Neuroscience. 2006;9:1007–8. doi: 10.1038/nn1728. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams KD, Cheung C.KK, Choi W. Cyberostracism: effects of being ignored over the internet. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 2000;79:748–62. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.79.5.748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams KD, Jarvis B. Cyberball: a program for use in research on interpersonal ostracism and acceptance. Behavioral Research Methods. 2006;38:174–80. doi: 10.3758/bf03192765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamoto M, Matsui Y, Yamanari Y. The structure of perceived aspects of self. Japanese Journal of Educational Psychology. 1982;30:64–8. [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura S, Okamoto Y, Onoda K, et al. Rostral anterior cingulate cortex activity mediates the relationship between the depressive symptoms and the medial prefrontal cortex activity. Journal of Affective Disorders. in press doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2009.06.017. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshimura S, Ueda K, Suzuki S, Onoda K, Okamoto Y, Yamawaki S. Self-referential processing of negative stimuli within the ventral anterior cingulate gyrus and right amygdala. Brain and Cognition. 2009;69:218–25. doi: 10.1016/j.bandc.2008.07.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zadro L, Boland C, Richardson R. How long does it last? The persistence of the effects of stracism in the socially anxious. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2006;42:692–7. [Google Scholar]

- Zadro L, Williams KD, Richardson R. How low can you go? Ostracism by a computer is sufficient to lower self-reported levels of belonging, control, self-esteem, and meaningful existence. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology. 2004;40:560–7. [Google Scholar]