Abstract

Theory suggests that the field of study may be at least as consequential for fertility behavior as the duration and level of education. Yet, this qualitative dimension of educational achievement has been largely neglected in demographic studies. This article analyzes the mechanisms relating the field of study with the postponement of motherhood by European college-graduate women aged 20–40. The second round of the European Social Survey is used to assess the impact of four features of study disciplines that are identified as key to reproductive decision making: the expected starting wage, the steepness of the earning profile, attitudes toward gendered family roles, and gender composition. The results indicate that the postponement of motherhood is relatively limited among graduates from study disciplines in which stereotypical attitudes about family roles prevail and in which a large share of the graduates are female. Both the level of the starting wage and the steepness of the earning profile are found to be associated with greater postponement. These results are robust to controlling for the partnership situation and the age at entry into the labor market.

In recent decades, women’s levels of educational attainment have markedly increased throughout Europe. Their participation in higher education has grown even to the extent that women now form the majority of those enrolled for university degrees (Eurostat 2007). To a varying extent in different regions of Europe, this catching up in education has also been translated into growing levels of participation in the paid labor market. A major demographic consequence has been the increasing postponement of first births (Sobotka 2004).

Yet women are still heavily underrepresented in the more lucrative and powerful jobs. Although welfare states have been successful in furthering women’s labor market participation, they have failed to achieve gender equity with respect to wage levels or occupational standing. In fact, nations that have been the most successful in fostering female labor force participation are the very ones that tend to exhibit high concentrations of women in female-typed occupations and low female presence in the most lucrative and powerful positions. This can be explained by the fact that highly developed welfare states tend to host sheltered segments in the labor market with many opportunities for part-time work and parental leave but relatively flat career prospects. Jobs in these segments are typically held predominantly by women and can be combined relatively easily with childcare and housework (Mandel and Semyonov 2006).

The concentration of women’s jobs in poorly paid sectors like public administration, nursing, and teaching corresponds to a large degree with the concentration of women and girls within particular disciplines at colleges and schools. European women have a higher tendency than men to seek degrees in health or personal care, to be trained as teachers, or to graduate in the humanities. Women pursuing a technical or technological diploma are a minority even though wages in these sectors tend to be higher (Brown and Corcoran 1997; Jurajda 2003; Machin and Puhani 2003).

One reason why women are overrepresented in particular fields of education may be that they expect these kinds of studies to lead to jobs that can be combined relatively easily with motherhood. Maybe teenage women choose their discipline as a function of their attitudes about women’s roles. Predominantly female branches of study may better fit with stereotypically gendered family norms. Those norms are likely to be connected to preferences about motherhood (Hakim 2000; Lappegård and Rønsen 2005).

A case can be made, therefore, that the field of study is just as relevant for entry into parenthood as the level of education. Yet this qualitative dimension of educational achievement has been largely neglected by demographers. A large body of literature explores the connection between the level of education and first births (Billari and Philipov 2004; Blossfeld 1995; Blossfeld and Huinink 1991; Gustafsson 2005; Gustafsson and Worku 2005; Hoe m 1986; Kravdal 1994; Lappegård 2002; Liefbroer and Corijn 1999; Marini 1984; Martin 2000; Rindfuss, Morgan, and Offutt 1996; Rindfuss, Morgan, and Swicegood 1988). However, just a few studies have been published about the relationship between study discipline and entry into motherhood, and those studies concentrate on the population of just one nation state. Their results suggest that the study discipline has an independent effect that cannot be explained by, and is more decisive than, the level of educational attainment or the duration of enrollment (Hoem, Neyer, and Andersson 2006a, 2006b; Kalmijn 1996; Lappegård 2002; Lappegård and Rønsen 2005; Martín-García and Baizán 2006; Neyer and Hoem 2008). The mechanisms behind this effect remain unclear, although the literature mentions several plausible explanations (Hoem et al. 2006a; Lappegård and Rønsen 2005; Neyer and Hoem 2008).

The aim of this article is to see how the field of study (i.e., the subject of graduation) is related to the postponement of motherhood across 21 European countries. To this end, I use data on women from the second round of the European Social Survey (Jowell and the Central Co-ordinating Team 2005), hereafter referred to as ESS2, who are no longer enrolled in full-time education.

The field of study is fixed after graduation, in contrast to personal attitudes and values, and it does not change as a consequence of childbirth. Because the choice of field of study has temporal priority over actual entry into motherhood, the former cannot be caused by the latter. Therefore, it makes sense to use the cross-sectional ESS2 to study the effect of education on fertility.

Still, any association between the field of study and the rate of entry into motherhood may result from two processes. First, field of study may causally affect family attitudes and career prospects, and these attitudes and prospects may affect the timing of childbearing later on in the life course. Second, it may just as well be that an antecedent set of characteristics, including personality traits and family attitudes originating from primary socialization, causally affects both the choice of study discipline and the rate of entry into parenthood. This second process need not involve any causal effect of study discipline on entry into parenthood. Rather, it implies that women who are prone to make the transition to motherhood are selected into particular study disciplines. The first and the second processes may both apply at the same time, and they may be mutually reinforcing. With the cross-sectional data for Europe at hand, one cannot distinguish between the two processes and separate out selection effects from causation.

With these two causal pathways in mind, I investigate the association between field of study and the postponement of motherhood across Europe by means of multilevel logistic regression, with women cross-classified by country and field of study at the macro level. The concept of postponement is not used here to denote the historical process of increasing proportions of the population having their first child at a later age. Rather, postponement here denotes the individual-level process of deferring first childbearing, as it is witnessed in Europe today. Empirically, postponement is evidenced in cross-sectional data by the condition of not having had a first child. I leave aside whether postponement eventually results in childlessness, because the distinction between the postponement and the forgoing of childbearing can be made only at the end of the fecund life span. Thus, postponement in this article should be interpreted as determined both by the probability and by the timing of childbearing.

In order to shed light on the underlying mechanisms behind the link between study discipline and first birth timing, key characteristics of fields of education are entered into the equation. More specifically, I look at the effects of the expected wage profile, norms about gender roles, gender composition, and the mediating role of marriage and cohabitation.

EDUCATION AND ENTRY INTO MOTHERHOOD

Three dimensions of education have been shown to be related to fertility and fertility postponement (Lappegård and Rønsen 2005): the duration of educational activity, the level of educational attainment, and educational field (e.g., humanities, engineering, or health care). First, ample evidence suggests that women’s enrollment in schools and colleges delays their transition to parenthood (e.g., Blossfeld 1995; Blossfeld and Huinink 1991; Hank 2002; Kravdal 1994; Lappegård and Rønsen 2005; Liefbroer and Corijn 1999; Skirbekk, Kohler, and Prskawetz 2004). This effect conforms to the sequencing norm that women who are still studying are not yet prepared to give birth and raise children: in most Western countries, finishing full-time education counts as one of the key prerequisites for parenthood (Blossfeld and Huinink 1991; Rindfuss et al. 1988; Skirbekk et al. 2004).

There is more discussion about the effect of the second dimension of education, the level of educational attainment. On the one hand, economic theories argue that a higher level of education represents a higher level of investment in human capital. The accumulated human capital, in turn, paves the way for the better jobs. As a consequence, the opportunity costs of motherhood increase because childbirth implies an interruption of activity in the labor market at least for some time. Therefore, more highly educated women should be more inclined to postpone or forgo children than less-educated women (Gustafsson 2001, 2005; Kravdal 1994, 2004). Better-educated women are expected to enter motherhood at a later stage in their employment careers, when they consider themselves to be more established in their jobs and when taking a break may be perceived as less damaging to their careers. On the other hand, if the wage profile of highly educated women is relatively steep, it may be less costly to have children early in the career than later (Lappegård and Rønsen 2005). In addition, college-educated women are older when they graduate than women with just a high school diploma. Therefore, the biological and social clocks that set limits to the ages at childbearing may stimulate the highly educated to “catch up” by starting childbearing soon after graduation and to space their children closely. In that case, there would be no effect of the level of education on fertility postponement after controlling for graduation and the number of years spent in education (Blossfeld and Huinink 1991; Lappegård and Rønsen 2005).

Empirical research has found that the influence of the level of educational attainment on the timing of first births varies by country: in some countries, highly educated women postpone motherhood significantly more (i.e., they are more likely to postpone, and they postpone longer), even after controlling for the duration-of-enrollment effect; in other countries, there is no effect or only a small effect of educational attainment. This heterogeneity may be attributed to differences between countries with respect to the opportunity costs of having children: in some countries, paid labor can be relatively easily combined with mothering young children, thanks to the availability of childcare, for example. In those countries, the opportunity costs will be relatively low. Norway may be a case in point: Lappegård and Rønsen (2005) found that highly educated women in that country catch up rapidly after graduation. In contrast, the opportunity costs of the transition to motherhood will be high in countries with strong conflicts between paid work and motherhood, like in Germany (Blossfeld 1995; Rindfuss, Guzzo, and Morgan 2003).

Diverging wage profiles and opportunity costs may also be related to the third dimension of education, the study discipline. Indeed, different fields of education lead to different economic sectors associated with working conditions that may facilitate or hamper the combination of work and family life (Hoem et al. 2006a; Kravdal 1994). Lappegård and Rønsen (2005) argued that the effect of the level of education may operate chiefly through prolonged participation in education; but as they stated, “Having completed education, however, differences in opportunity costs may first and foremost be reflected through different fields of education that lead to different occupations and employment sectors” (p. 34).

Beyond the economic implications of particular qualifications, there are at least two other reasons why study discipline may affect fertility postponement. First, the choice of a subject of study may reflect a person’s values and related preferences. At the same time, these values and preferences may be molded by enrollment in a particular discipline with its associated subculture. These cultural elements may influence the timing of entry into motherhood. Second, the field of study affects the social environment during the student’s formative years (Hoem et al. 2006a). In particular, this includes the extent of sex segregation in the chosen study area, which may bear on the orientation toward family formation.

Only a handful of empirical studies have been published about the effect of study discipline on fertility in Europe, and all these concentrate on one nation state. A Dutch study found that women with a degree in the social and cultural sciences had higher first motherhood rates than otherwise comparable women with a business- or technology-oriented degree (Kalmijn 1996). Lappegård (2002) concluded from an analysis of Norwegian register data that the field of study has a more decisive influence of women’s fertility than the level of education. She found that women who graduated in female-dominated disciplines are less likely to remain childless and, after becoming mothers, tend to have more births. Apart from that, women with a high career orientation who are educated to work in health care (like doctors and dentists) appeared to have high fertility as well. Hoem et al. (2006a, 2006b) concluded that fertility seems to depend more on the field than on the level of education in Sweden as well. They found that among a cohort of Swedish women who had completed their reproductive years, those educated for jobs in teaching and health care have much lower permanent childlessness than in any other major grouping. Women educated in arts and the humanities have high proportions permanently childless. A replication study in Austria yielded basically the same result (Neyer and Hoem 2008). Among Swedish women who did become mothers, Hoem et al. (2006b) found that the study discipline mattered for final parity as well. Again, mothers who were trained to become teachers or health care professionals have higher fertility than others.

In a detailed hazard analysis with longitudinal Norwegian data, Lappegård and Rønsen (2005) found that women with a degree in the humanities and the social sciences have relatively low first-birth rates. Women with a degree in engineering or in administration and economics have low first-birth rates as well. The authors speculated that low motherhood rates for the first group may be due to a relatively unfavorable labor market position, while the second group may be less family oriented and more work oriented at the outset. High first-birth rates were found among teachers and health care professionals. Lappegård and Rønsen (2005) concluded that there is no clear-cut relationship between high costs of labor market withdrawal and postponed motherhood, and that heterogeneity in terms of a family versus a work orientation also matters.

Just like in the Swedish case, however, the register data do not contain information about family values that can be used to explore their role in connecting the choice of study discipline with family formation. In the current study, I use ESS2 to shed light on this. More specifically, I assess the effects of three key features of study disciplines that the literature identifies as relevant: earning profiles, family attitudes, and gender composition.

DATA AND METHODS

For the analysis in this article, I use data from ESS2. This is a cross-sectional survey that is rigorously concerned with maximizing data quality, response rates, and cross-national equivalence (Jowell et al. 2005; Jowell et al. 2007).

Selection of Cases and Weights

The analysis is restricted to women aged 20–40 who are no longer enrolled in full-time education (hereafter referred to as graduated women). For reasons to be explained below, I also use information about family values of students who are still enrolled in full-time education and about monthly wages earned by men as well as women with a full-time job.

As indicated earlier, school or college enrollment has been consistently found to postpone motherhood. In fact, in some regions, the sequencing norm that people should postpone family formation until they have finished their education is so strong that childbirth during educational activity is very rare. Hence, even when enrollment in education is included in a regression equation, estimates for other covariates of entry into parenthood will be biased because the process leading to the first childbirth for women still enrolled in education is likely to be very different than that for graduated women (Marini 1984; Skirbekk et al. 2004). Therefore, the subsequent analysis is limited to women who are no longer enrolled in full-time education. They will be called graduated women even if some of them will not have obtained their degree.

The integrated file of ESS2 edition 2.0 contains survey data for 24 countries. Data for France had to be dropped because they do not include information on the field of study. The national categories of level of education could not be recoded into the international standard format for the United Kingdom, and the U.K. data were therefore omitted from the international file. Finally, data on Iceland were dropped because of a lack of sufficient cases. The following analyses are therefore based on ESS2 data for 21 countries (from north to south): Norway, Sweden, Finland, Estonia, Ireland, Denmark, Germany, Poland, the Netherlands, Belgium, Luxemburg, Czech Republic, Slovakia, Ukraine, Switzerland, Austria, Hungary, Slovenia, Portugal, Spain, and Greece. Table 1 gives the number of graduated women aged 20–40 available for the analysis of the postponement of parenthood in these 21 countries.

Table 1.

Countries Included in the Analysis, Country Codes and (unweighted) Number of Graduated Women Aged 20–40 in the Sample

| Country | Code | N | Country | Code | N | Country | Code | N |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Austria | AT | 329 | Greece | GR | 390 | Portugal | PT | 323 |

| Belgium | BE | 270 | Hungary | HU | 240 | Slovakia | SK | 11 |

| Czech Republic | CZ | 431 | Ireland | IE | 377 | Slovenia | SI | 170 |

| Denmark | DK | 203 | Luxemburg | LU | 230 | Spain | ES | 255 |

| Estonia | EE | 222 | Netherlands, the | NL | 305 | Sweden | SE | 244 |

| Finland | FI | 267 | Norway | NO | 261 | Switzerland | CH | 374 |

| Germany | DE | 372 | Poland | PL | 285 | Ukraine | UA | 314 |

In all empirical analyses, cases were weighted by the ESS2 design weights. These weights take care of differences between countries in sampling design while estimating point estimates and standard errors of model parameters (Häder and Lynn 2007). I did not apply population weights for two reasons. From a technical point of view, population weights would distort the estimates of the standard errors: standard errors should reflect sampling design rather than population size. From a substantive point of view, the interest lies more in differences between European countries than in estimating some overall European average.

Modeling the Postponement of Parenthood

ESS2 is a general-purpose social survey that has not been designed for demographic analysis. Yet the high quality of the data and the exceptional care given to the comparability of the questionnaires across Europe are two decisive reasons to use this body of data. A drawback is that no complete fertility histories are recorded; only the number of surviving children at the time of the survey is available. Therefore, any children who died are missing. This bias is considered to be minor and is neglected in the subsequent analysis. Fortunately, both children living with the survey respondent and children living in another household are counted.

The postponement of parenthood will be modeled in this article as the probability that a respondent does not have any children alive, not even stepchildren or adopted children. This probability will be modeled as a function of the woman’s current age, some of her own characteristics, the country she lives in, and characteristics of the field of study within that country. Put another way, I will be modeling the multilevel conditional probability that a woman’s age at first birth is past her current age:

| (1) |

where aijk is the current age of a woman i who graduated in subject j in country k, Aijk is her (virtual) age at first childbearing, xijk is a vector of individual characteristics, and fjk is a vector of features of study field j in country k. Finally, ck is included to capture the effect of living in country k. This definition of the probability of postponement is equivalent to the definition of the survivor function in event-history analysis (Courgeau and Lelièvre 1992). Particular to this case is that all observations are censored at the time of the survey. Clearly, this censoring is noninformative (Singer and Willett 2003) because respondents are selected to participate in the survey irrespective of their fertility history.

The multilevel conditional probabilities of postponement will be modeled using logistic regression with random effects on two levels (Agresti 2002): one on the level of study discipline within country, and another on the country level. So the basic structure of the models to be estimated is as follows:

| (2) |

The parameters to be estimated are the overall intercept γ00, the slopes ϕ1 and ϕ2 for current age and age squared (in order to allow for a nonmonotonic effect), a vector of fixed effects β of the characteristics of individual women, and fixed effects γ01 of characteristics of fields of education within countries. In addition, I estimate the variance of ujk, that is, the random effect of field of study; and I estimate the variance of ck, that is, the random effect of country on the level of postponement. Both random effects are assumed to be independently normally distributed. Model parameters were estimated using R’s lmer function, applying the Laplace approximation method (Bates and Sarkar 2006; R Development Core Team 2006).

The vector of individual-level covariates xijk includes indicators only for the educational careers of women because these are fixed at the time of graduation. Individual-level indicators for current family values, current activity in the labor market, or current wage are not included in the model because they are known to be endogenous to the transition to motherhood. For example, earlier panel studies have found that family values and attitudes do affect entry into parenthood, but also that they tend to become more traditional after entry into parenthood (Jansen and Kalmijn 2000; Moors 1997; Morgan and Waite 1987).

Education

ESS2 asked respondents about the subject of their highest qualification and offered 14 response alternatives. Because the number of cases in some fields was too small, I regrouped these ESS2 categories into nine categories. They are listed in the first column of Table 2, along with the original ESS2-classification and the unweighted number of female graduates in the sample.

Table 2.

Fields of Education

| Code | Categories in This Study | Original ESS2 Categories | N |

|---|---|---|---|

| TEA | Teaching, training or education | Teacher training or education | 401 |

| ART | Arts and humanities | Art: fine or applied | |

| Humanities | 392 | ||

| TEC | Science and technology | Technical and engineering, including architecture and planning, industry, craft, building trades, etc. | 533 |

| Science, mathematics, computing, etc. | |||

| HEA | Health care | Medical, health services, nursing, etc. | 720 |

| ADM | Private and public administration | Commerce, business administration, accounting, etc. | 1,486 |

| Public administration, media, culture, sport and leisure studies, social and behavioral studies, etc. | |||

| LAW | Law and legal services | Law and legal services | 94 |

| PER | Personal care services | Personal care services: catering, domestic science, hairdressing, etc. | 702 |

| GEN | General or no specific field | General or no specific field | 1,370 |

| OTH | Other | Agriculture and forestry | 175 |

| Public order and safety: police, army, fire services, etc. Transportation and telecommunications |

Some comments about these categories are in order. First, the category of women trained as teachers is not as clear-cut as I would like. For example, those who chose linguistics instead of education as their major discipline cannot be differentiated in terms of those who obtained additional qualifications to be a teacher and those who did not. As a result, the group of teachers in this study is not as unambiguous as that in the study by Hoem et al. (2006a, 2006b), and there will be many teachers among those who declared that their major study area was the hard sciences or the humanities, for example. Second, earlier work suggests that women with a law degree stand apart in terms of their earning potential, possibly affecting fertility behavior through high opportunity costs (Kalmijn 1996; Lappegård and Rønsen 2005). Therefore, I created a separate category for this group even though the number of cases is relatively low. Third, the category “personal care services” includes vocational training leading to jobs as diverse as cooks, hairdressers, salespersons, or tailors. As a result, heterogeneity within this category is likely to be very large.

Apart from the field of study, all models include both the level and the duration of education. To construct an internationally equivalent and robust classification for the level of the highest degree obtained, I reduced the number of categories to three: low (lower secondary schooling or less), medium (upper- or postsecondary schooling completed), and high (first or second stage of tertiary schooling; that is, college, polytechnic, and university). The number of years enrolled in education is measured in full-time equivalents, including compulsory schooling but excluding kindergarten years. Basic descriptive statistics for all covariates used in the models are in Table 3.

Table 3.

Descriptive Statistics of the Dependent and Independent Variables Used in the Regression Analyses

| Variable | Mean | SD | Minimum | Maximum | N | % |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Individual-Level Variables | ||||||

| Dependent variable: Still childless | ||||||

| 0 = no | 3,503 | 62.7 | ||||

| 1 = yes | 2,081 | 37.3 | ||||

| Age | 31.6 | 5.5 | 20 | 40 | 5,584 | |

| Level of education | ||||||

| Low | 1,228 | 22.0 | ||||

| Medium | 2,882 | 50.5 | ||||

| High | 1,534 | 27.5 | ||||

| Years enrolled in full-time education | 13.3 | 3.4 | 0 | 32 | 5,584 | |

| Years since first cohabiting with current partner | 6.6 | 6.5 | 0 | 27 | 5,502 | |

| Married | ||||||

| 0 = no | 2,551 | 45.7 | ||||

| 1 = yes | 3,033 | 54.3 | ||||

| Ever had steady job (six months, 20 hours/week) | ||||||

| 0 = no | 307 | 5.5 | ||||

| 1 = yes | 5,275 | 94.5 | ||||

| If yes, age at entry | 19.9 | 3.6 | 3 | 37 | 5,275 | |

| Characteristics of Study Fields | ||||||

| Stereotypical attitude toward gendered family roles | −0.41 | 0.45 | −1.60 | 0.87 | 151 | |

| Proportion of women among graduates | 0.59 | 0.23 | 0.07 | 1.00 | 151 | |

| Starting wage relative to country’s median, in 100 euros | 0.19 | 4.67 | −19.78 | 15.44 | 151 | |

| Steepness of the earning profile (slope) | 1.03 | 0.03 | 0.92 | 1.17 | 151 |

Attitudes Toward Gendered Family Roles

Respondents were asked to indicate whether they agreed strongly, agreed, neither agreed nor disagreed, disagreed, or disagreed strongly with the following five statements: (1) A woman should be prepared to cut down on her paid work for the sake of her family; (2) Men should take as much responsibility as women for the home and children; (3) When jobs are scarce, men should have more right to a job than women; (4) When there are children in the home, parents should stay together even if they don’t get along; (5) A person’s family ought to be his or her main priority in life. These items were used to construct an index of stereotypical attitudes (alternatively called traditional or conservative attitudes) toward family norms. This index was constructed with the complete ESS2 sample of men and women of all ages (ranging from 15 to 102 years). Exploratory factor analysis yielded two factors with eigenvalues above unity. Item analysis showed that Item 2 correlates only weakly with both factors and that it is unable to discriminate between respondents because just about everyone agreed with it, probably because “taking responsibility” can mean many things, including playing the breadwinner role. Item 5 stands apart as an item that hardly correlates with the others; less than 6% of respondents disagreed with it. I therefore dropped Items 2 and 5 from the scale. Confirmatory factor analysis indeed showed that inclusion of these two items results in a poor fit of both a one- and a two-factor model (as judged by the RMSEA index; see Kline 2005).

Thus, three items remain in the scale of stereotypical family attitudes: Items 1, 3, and 4. The confirmatory factor loadings from the exactly identified measurement model with one factor and three indicators are, respectively, .60, .80, and .49; these values are not great but are reasonable. The same holds for the reliability of the scale, as indicated by a Cronbach’s alpha of .62.

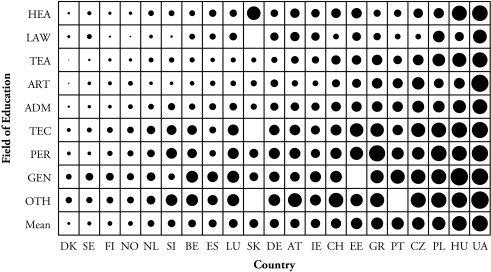

Next, standardized factor scores were calculated for ESS2 respondents of all ages and both sexes using regression (Kline 2005). Finally, these factor scores were averaged per country and field of study. Figure 1 displays these averages in a dot plot: for each combination of country and field of study, the more stereotypical the attitude toward family roles, the bigger the dot. The bottom row gives the overall averages per country. Clearly, the factor scores confirm the well-known tendency for Scandinavian countries to be more progressive and southern and eastern European countries to be more conservative. Spain, Slovakia, and Slovenia, however, appear in the middle part of the distribution.

Figure 1.

Mean Factor Scores for Stereotypical Attitude Toward Gendered Family Roles, Complete ESS2 Sample, by Country and Field of Study

Note: See Table 1 for a list of country codes, and see Table 2 for field-of-education codes.

The country gradient is crossed by a study discipline gradient. People trained to work in health care, in legal services, or in education, or those with a degree in arts and the humanities tend to have less stereotypical family attitudes than people with a degree in engineering or the natural sciences, people trained to work in personal care services, or people who obtained a general or “other” degree. The rank order of study fields is not exactly the same in every country. For example, in Sweden and Denmark, teachers have the most progressive attitudes; in Belgium, the Netherlands, or Austria, people trained in arts and the humanities are at the bottom of the distribution. Also note that the field of study is not independent of the level of the degree obtained. Therefore, family attitudes also reflect, to some extent, the level of educational attainment. In most countries, people with no degree or a general degree have the most stereotypical attitudes. These tend to be degrees that require less schooling. On the other side of the scale, most people with a degree in law and legal services are university graduates. These people typically have a more progressive family attitude.

Family attitudes tend to become more conservative after parenthood (Jansen and Kalmijn 2000; Moors 1997; Morgan and Waite 1987). Therefore, in order to maximize the exogeneity of this covariate, the models presented below include average factor scores for students only—that is, only people who were still enrolled in full-time education were included in the calculation of the averages for the study disciplines (N = 4,292, mean age of 20.2, with standard deviation equal to 6.6). One downside of this approach is that the averages are biased in favor of attitudes held by people enrolled in longer educational programs; people with lower educational levels will be underrepresented in the averages because they are more likely to have already finished their studies by the time of the survey. Another downside is that the averages are less robust because they are based on a more limited number of cases. Therefore, because noise in the independent variables undermines the power to identify their actual effects, the estimates of the slope for family attitudes are conservative. Including graduates as well as students, however, yields similar results.

Earning Profiles

I determined earning profiles for study disciplines by running a series of ordinary least squares (OLS) regressions of the log of monthly gross wages on seniority in the work force—that is, the total number of years respondents had been engaged in paid work. The intercepts of the regressions represent the starting salaries. The slopes represent the steepness of the earning profiles. Earning potential is a function of both the intercept and the slope. Separate regressions were run for each discipline within each country, but only for the respondents who indicated that they were engaged in full-time paid work at least 35 hours per week. The oldest cohorts who had worked for more than 20 years were excluded because their profiles might no longer be relevant for our study population. In the multilevel models of postponement of motherhood, both the intercepts and the slopes were introduced in exponentiated format in order to restore the natural scale of earnings in euros. The expected starting wages are expressed as deviations from each country’s median in order to neutralize the high diversity in wage levels between countries and in order to focus on the diversity between study disciplines.

After 10 years of seniority in the labor market, the expected earnings tend to be highest for people who studied law or health care. They tend to be lowest for people with a general or “other” diploma, or for people who were trained to work in personal care services. However, the diversity between countries in the rank order of the earning potential of study disciplines is high. Bear in mind that these differences also reflect sampling error.

Gender Composition

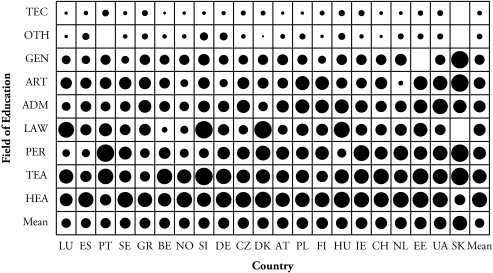

Lappegård (2002) found that Norwegian women who graduated in female-dominated disciplines are less likely to remain childless and, after becoming mothers, tend to have more births. In order to test whether a similar effect exists across Europe, I calculated the proportion of women among ESS2 respondents aged 20–24 who obtained a degree in each of the nine study disciplines and 21 countries. Again, these calculations were carried out separately by country. Figure 2 displays these proportions in a dot plot.

Figure 2.

Proportion of Women Among 20- to 40-Year-Olds in ESS2 by Field of Study and Country

Note: See Table 1 for a list of country codes, and see Table 2 for field-of-education codes.

The gradient is dominated by study field rather than country: the means per country across disciplines do not vary greatly, but the means per study field across countries do. Teaching and health care are the two most strongly female-typed study disciplines. Third are studies in personal care services. Among graduates in the natural sciences and technology-oriented disciplines, women are a minority. The residual category of “other” disciplines is male-dominated as well.

RESULTS

Model 1 describes the probability of postponement of first births as a function of the number of years enrolled in full-time education and the level of the degree obtained. Model estimates are displayed in Table 4. As expected, on average across Europe, the more years enrolled in school and the higher the level of the degree obtained, the higher the probability that a woman has not yet become a mother at a given age.

Table 4.

Multilevel Logistic Regression Models of the Postponement of First Births Among European Women Aged 20–40

| Variable | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept | 0.793*** (0.228) | 0.862*** (0.235) | −6.336*** (1.909) | −6.211** (2.149) | −6.519** (2.231) |

| Individual Covariates | |||||

| (Age – 20) | −0.411*** (0.027) | −0.413*** (0.027) | −0.388*** (0.026) | −0.192*** (0.031) | −0.222***(0.032) |

| (Age – 20), squared | 0.009*** (0.001) | 0.009*** (0.001) | 0.008*** (0.001) | 0.001 (0.001) | 0.002 (0.001) |

| Level of education (ref. = low) | |||||

| Medium | 0.492*** (0.107) | 0.485*** (0.109) | 0.288** (0.102) | 0.421*** (0.116) | 0.400*** (0.120) |

| High | 0.780*** (0.135) | 0.783*** (0.139) | 0.530*** (0.133) | 0.731*** (0.155) | 0.595*** (0.161) |

| Years enrolled in full-time education | 0.100*** (0.013) | 0.096*** (0.014) | 0.086*** (0.013) | 0.065*** (0.016) | 0.056*** (0.016) |

| Years since first cohabiting with current partner | −0.331*** (0.025) | −0.329*** (0.025) | |||

| Years since first cohabiting with current partner, squared | 0.012*** (0.001) | 0.012*** (0.001) | |||

| Married (1 = yes, 0 = no) | −1.008*** (0.104) | −1.061*** (0.107) | |||

| Ever had steady job | −0.559† (0.308) | ||||

| Age at entry | 0.050*** (0.013) | ||||

| Characteristics of Study Fields | |||||

| Stereotypical gendered family roles attitude | −0.464*** (0.114) | −0.310* (0.127) | −0.329* (0.131) | ||

| Proportion of women among graduates | −0.585** (0.211) | −0.530* (0.237) | −0.406† (0.242) | ||

| Starting wage relative to country’s median, in 100 euros | 0.045*** (0.012) | 0.054*** (0.014) | 0.051*** (0.014) | ||

| Steepness of the earning profile (slope) | 7.378*** (1.858) | 7.786*** (2.093) | 7.904*** (2.168) | ||

| Standard Deviations of Random Components | |||||

| Country level | 0.498 | 0.497 | 0.100 | 0.101 | 0.103 |

| Field of study, by country | 0.223 | 0.269 | 0.271 | 0.276 | |

| Deviance | 5,590 | 5,585 | 5,618 | 4,323 | 4,130 |

| N (women) | 5,584 | 5,584 | 5,584 | 5,502 | 5,286 |

Note: Standard errors are in parentheses.

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

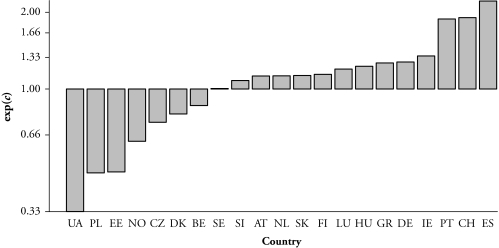

By including a random intercept at the country level, Model 1 explicitly allows the extent of postponement to vary by country. Figure 3 shows the country-level variation in postponement. Net of the effect of differences in the composition of these countries in terms of duration and level of education, women postpone childbearing the most in Spain, Switzerland, and Portugal. The least likely to postpone motherhood are women in Ukraine, Poland, and Estonia.

Figure 3.

Empirical Bayes Estimates of Country-Level Random Effects in Model 1a

aLabels on the vertical axis are exponentiated values that can be interpreted as factor effects.

Model 2 introduces random intercepts at the level of field of education within countries. The estimated standard deviation of these random intercepts (ujk in Eq. (2)) is 0.22 on the logit scale. The standard deviation of the random intercepts at the country level (ck in Eq. (2)) remains the same as in Model 1, at about 0.50 on the logit scale. The one extra parameter estimated in Model 2 yields a decrease in the deviance statistic of 5.173, which is statistically significant (according to a chi-square test with 1 degree of freedom, p < .05).

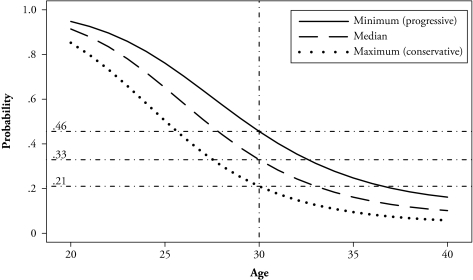

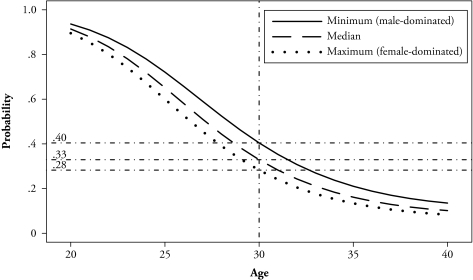

Model 3 introduces four characteristics of study disciplines within each country: prevailing attitudes toward gendered family norms, the proportion of women among graduates, expected earnings for starters in the labor market, and the steepness of the earning profile. First, women who graduated in a study discipline in which stereotypical attitudes toward gendered family roles prevail are less likely to postpone their first births. Figure 4 illustrates the effect across the range of family attitudes observed among students in different countries and fields of education. The expected percentage of women still childless at age 30 is 33% for women with a medium level of education who graduated and who chose a discipline in which family attitudes are at their median value. In the country-discipline combination with the most stereotypical attitudes (i.e., teachers in the Czech Republic), the expected proportion still childless at age 30 is only 21%. On the progressive extreme of the range (i.e., among law students in Norway), the expected proportion is 46% at age 30. Thus, family attitudes prevailing in study disciplines make a difference of at most 25 percentage points.

Figure 4.

Expected Postponement Probabilities by Age and Stereotypical Attitudes Toward Gendered Family Norms Prevailing in Study Disciplinesa

aExpected probabilities for women with a medium level of education who were enrolled in education for 12 years. All other covariates are set at their median values.

The effect of the proportion of women among graduates is also statistically significant: the more female-dominated the study field, the less inclined graduates are to postpone motherhood. Figure 5 plots the survival curves across the range of values observed for this covariate. At the minimum proportion of women of 7% (“other” disciplines in Denmark), the expected proportion still childless at age 30 is 40%. At the other extreme—that is, among teachers in Slovenia, where all 20- to 40-year-old graduates in the sample are women—the expected proportion childless at age 30 is only 28%. Thus, in this sample, the gender composition makes at most a 12 percentage point difference in terms of postponement.

Figure 5.

Expected Postponement Probabilities by Age and the Proportion Female Among Graduates From Study Disciplinesa

aExpected probabilities for women with a medium level of education who were enrolled in education for 12 years. All other covariates are set at their median values.

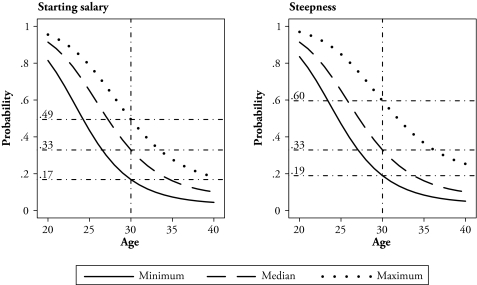

Finally, as to the earning profile, both the starting wage and the steepness of the earning profile make a statistically significant difference. Recall that the earnings for starters who have no seniority in the labor market are expressed as deviations from the median for their country. Overall, disciplines with a high earning potential are associated with greater postponement. Both the starting wage and the steepness of the profile work in that direction. The left panel of Figure 6 shows that the probability of postponement is estimated at 17% for 30-year-old women with a medium level of education and a starting wage at the lowest level observed in this sample. For their peers who earned the maximum wage at the start of their paid work, postponement at that age is modeled to be 49%, which makes a difference of 32 percentage points. In isolation, however, the starting wage is a bad indicator for the relative earning potential because study disciplines with a relatively low starting wage may have a sharply rising earnings profile. An extreme case is law graduates in Switzerland, who have the lowest relative starting salary in this sample but who also have the highest slope for seniority. In contrast, law graduates in Norway have the highest relative starting salary of all country-discipline combinations, but they have a less than average slope for seniority. The right panel of Figure 6 suggests that the slope may have a greater effect on postponement than does the starting wage. The difference in expected proportions childless at age 30 for the steepest versus the flattest earning profile is 41 percentage points (60% – 19%).

Figure 6.

Expected Postponement Probabilities by Age and Expected Earnings for Starters in the Labor Market (left) and by Steepness of the Earning Profile (right)a

aExpected probabilities for women with a medium level of education who were enrolled in education for 12 years. All other covariates are set at their median values.

Are characteristics of study fields related to entry into motherhood only indirectly through the rate of partnership formation and marriage, or do the estimated effects remain significant after controlling for partnership situation? To address this issue, Model 4 includes the number of years since first cohabiting with the current partner, if any (otherwise, this covariate is set to zero), and a dummy variable indicating whether the respondent is married or not. The models presented so far did not include individual-level covariates on partnership because cohabitation and marriage may be strongly endogenous to entry into parenthood (Baizán, Aassve, and Billari 2003; Brien, Lillard, and Waite 1999; Lillard 1993). The strong and significant slopes for partnership in Model 4 therefore do not represent unidirectional causal effects on the postponement of first births.

Cohabitation with a partner is negatively associated with the postponement of motherhood. Yet, as found in earlier work (Lillard and Waite 1993), duration of cohabitation has a curvilinear rather than a linear effect on childlessness. During the first years of cohabitation, the likelihood of remaining childless declines. The significant second-order polynomial term indicates that couples who are still childless after a number of years are subsequently increasingly more likely to remain childless. After this polynomial is included, the second-order polynomial term for current age is no longer significantly different from zero. Formal marriage is clearly associated with a higher rate of entry into parenthood. All effects of the characteristics of study disciplines remain significant after partnership status is controlled for. The effects of family attitudes and gender composition weaken somewhat but remain significant. The estimated effects of the earning profiles, if anything, become slightly stronger.

Finally, activity in the labor market may affect the timing of the first birth and may be affected by actual or intended parenthood. Again, because of endogeneity, activity status was left out of the previous models. However, it may be argued that the earning profiles of fields of education affect the postponement of first births mainly through the timing of entry in the labor market. To check whether this is the case, Model 5 adds the age at which women started to work in their first jobs. Respondents in the survey were instructed to count only jobs at which they worked at least 20 hours per week for at least six months. This variable is included in the model through a product term: women who never had such a job were coded with zeros for the “ever had a steady job” dummy variable. For women who reported ever having had such a job, the dummy variable was multiplied with the age at entry. Obviously, the “ever had a steady job” and the “age at entry” variables should never be interpreted in isolation. The slope for age at entry describes how the effect of work experience changes per unit increase of age at entry. For a woman who entered her first job at age 20, the effect of work experience on the logit is estimated as −0.559 + 0.050 × 20 = 0.441. For a woman who entered at age 25, the effect is −0.559 + 0.050 × 25 = 0.691. For any age at first job above age 11, the effect of activity in the labor market on postponement is positive. The higher the age at taking the first job, the greater the expected postponement.

The effects of the earning profiles of study disciplines within countries hardly change after inclusion of entry into the labor market. Both the starting wage and the steepness continue to work in the same direction and with similar strength as before. It can be concluded that there is a direct effect of expected earnings on the postponement of first births. Not surprisingly, inclusion of entry into the labor market weakens somewhat the effect of a high level of educational attainment, as well as the effect of the duration of enrollment. This suggests that the effect of the level and duration of education to some extent operates indirectly through the age at entry into the labor market. The effect of family attitudes on the level of study disciplines, if anything, regains some strength. The effect of the sex composition of fields of education weakens and remains significant only at the alpha level of .10. The power to detect effects in Model 5, however, is somewhat weakened due to a reduction in the sample size (which is, in turn, due to nonresponse for the items about first job experience).

CONCLUSION

In recent decades, women have been catching up with men in terms of higher enrollment in education and higher educational attainment such that they now are the majority of those enrolled for university degrees in most European Union countries. Yet women are still underrepresented in the more lucrative and powerful jobs. Women tend to work predominantly in segments of the labor market characterized by relatively low and flat earning profiles. Typically, jobs in these segments can be relatively easily combined with mothering young children.

This article explored how study discipline is related to entry into motherhood in Europe through the attitudes toward gendered family roles that are associated with disciplines, the sex composition of graduates, and expected earnings. Maybe women tend to be overrepresented in particular study disciplines because they think that these will lead to jobs that facilitate the combination of work with parenthood. This selection will be related to attitudes about the family roles of men and women and about their respective priorities at home and in the paid labor market. More specifically, women selecting fields of education characterized by relatively stereotypical views about gendered family roles are expected to make the transition to parenthood sooner than women selecting fields in which more liberal views prevail. Fields of study leading to more lucrative jobs and a steep earning profile are typically more difficult to combine with parenthood and therefore may be associated with greater postponement of parenthood.

To test these hypotheses, I used data from the second round of the European Social Survey on college-graduate women aged 20–40 from 21 European countries. Multilevel logistic regression was used to model the probability that a woman is not yet a mother as a function of her own educational characteristics, her country, and characteristics of her study discipline. Study disciplines were treated as nested within countries; that is, characteristics of study disciplines were calculated separately by country, and the random effects of study disciplines in each country were estimated independently from the random effect of belonging to a country.

The results indicated that women who graduated in a study discipline in which stereotypical family attitudes prevail are indeed significantly less likely to postpone their first births. In line with that finding, it also appears that the more female-dominated the field of study, the less inclined graduates are to postpone motherhood. High earning potentials of study disciplines, as indicated both by the expected starting wage and by the steepness of the earning profile, appear to be associated with greater postponement. Women with a degree in a field in which full-time working graduates are expected to have relatively high earnings at the time of entry into the labor market are significantly more likely to delay their first births than women who expect to have a low income during their first working years.

The effect of the steepness of the earnings profile with seniority works in the same direction: a woman is expected to postpone motherhood more if she holds a degree in a field in which an additional year in the labor market is associated with a strong increase in monthly earnings than when her expected earnings rise to a lesser degree with seniority. Given the range of starting wages and slopes with seniority observed in this sample, it appears that the effect of the steepness of the earning profile is stronger than the effect of the starting wage. These findings are in line with economic theories suggesting a later entry into motherhood when the opportunity costs are high: women with a high earning potential are expected to enter motherhood at a later stage in their employment career, when they consider themselves more established in their jobs and when taking a break from paid work may be perceived as less damaging to their careers. The alternative hypothesis that women with a steep earning profile are inclined to have their children early in their careers, when forgone earnings would still be relatively low, is not supported by the European data presented here.

These effects of characteristics of study fields within countries are largely independent of partnership status. Cohabitation and marriage are clearly associated with faster entry into parenthood, but controlling for this hardly changes the effects of family attitudes, gender composition, and earning profile. The effect of the earning profile becomes slightly stronger. The effects of family attitudes and gender composition weaken just slightly. Inclusion of the timing of entry into the labor market in the model weakens the estimated effect of a high level of educational attainment, as well as the effect of the duration of enrollment in full-time education. The effect of family attitude, as a characteristic of field of study, becomes somewhat stronger. The estimates for earning profiles hardly change at all, while the effect of gender composition is weakened but continues to work in the same direction.

In sum, the choice of study discipline appears to be clearly related to entry into motherhood in Europe. This article has empirically identified four characteristics of fields of education that matter significantly: the expected starting wage, the steepness of the earning profile, the gender composition, and the family attitudes prevailing in study disciplines and countries. The latter variables were constructed at the macro level to avoid the problem of reverse causation.

Still, the cross-sectional nature of the ESS2 implies several limitations. First, women who have complex educational careers—for example, women who have multiple degrees—cannot be treated adequately with these data. Second, women who have children while studying or who were still enrolled in education at the time of the interview had to be omitted from the analysis. The latter selection implies that highly educated women have a lower chance of being included in this study, and countries may vary in the degree to which this selection biases the results. Third, these cross-sectional data cannot distinguish between two alternative explanations for the empirical associations. One possibility is that field of study indeed causally affects family attitudes and career prospects, and that these attitudes and prospects affect childbearing later on in the life course. Another possibility is that an antecedent set of characteristics, including personality traits and family attitudes, causally affects both the choice of study discipline and first childbearing. The first and the second process are not mutually exclusive. Rather, they may actually be mutually reinforcing. The second pathway need not involve any causal effect of study discipline on entry into parenthood. Rather, it implies that women who are prone to making the transition to motherhood are selected into particular study disciplines.

Sorting out selection from causation requires measurements of family attitudes and career expectations before or at the very start of the educational career, followed by measurements at the end of the educational process but before family formation. This would involve a long-term panel study. Unfortunately, there are no relevant panel data that cover Europe in an internationally comparable way.

Acknowledgments

The author wishes to thank the Flemish Fund for Scientific Research (FWO-Vlaanderen) for providing financial support for this research. Also many thanks to colleagues who commented on earlier papers based on this study and who inspired me to carry out the analysis presented here. In particular, I am grateful to Øystein Kravdal, Tomáš Sobotka, Francesco Billari, Jan Hoem, Gerda Neyer, the editors and four anonymous reviewers of Demography for their helpful comments.

REFERENCES

- Agresti A. Categorical Data Analysis. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Baizán P, Aassve A, Billari FC. “Cohabitation, Marriage, and First Birth: The Interrelationship of Family Formation Events in Spain”. European Journal of Population. 2003;19:147–69. [Google Scholar]

- Bates D, Sarkar D.2006Lme4: Linear Mixed-Effects Models Using S4 ClassesR Package Version 0.9952

- Billari FC, Philipov D.2004“Education and the Transition to Motherhood: A Comparative Analysis of Western Europe”European Demographic Research Papers 2004-3 Vienna Institute of Demography of the Austrian Academy of Sciences [Google Scholar]

- Blossfeld H-P. “Changes in the Process of Family Formation and Women’s Growing Economic Independence: A Comparison of Nine Countries.”. In: Blossfeld H-P, editor. The New Role of Women-Family Formation in Modern Societies. Oxford: Westview Press; 1995. pp. 3–34. [Google Scholar]

- Blossfeld H-P, Huinink J. “Human Capital Investments or Norms of Role Transition? How Women’s Schooling and Career Affect the Process of Family Formation”. American Journal of Sociology. 1991;97:143–68. [Google Scholar]

- Brien MJ, Lillard LA, Waite LJ. “Interrelated Family-Building Behaviors: Cohabitation, Marriage, and Nonmarital Conception”. Demography. 1999;36:535–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown C, Corcoran M. “Sex-Based Differences in School Content and the Male-Female Wage Gap”. Journal of Labor Economics. 1997;15:431–65. [Google Scholar]

- Courgeau D, Lelièvre E. Oxford: Clarendon Press; 1992. Event History Analysis in Demography. [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat . Europe in Figures. Eurostat Yearbook 2006–07. Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson S. “Optimal Age at Motherhood. Theoretical and Empirical Considerations on Postponement of Maternity in Europe”. Journal of Population Economics. 2001;14:225–47. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson S. “Having Kids Later. Economic Analyses for Industrialized Countries”. Review of Economics of the Household. 2005;3:5–16. [Google Scholar]

- Gustafsson S, Worku S. “Assortative Mating by Education and Postponement of Couple Formation and First Birth in Britain and Sweden”. Review of Economics of the Household. 2005;3:91–113. [Google Scholar]

- Häder S, Lynn P. “How Representative Can a Multi-Nation Survey Be?”. In: Jowell R, Roberts C, Fitzgerald R, Eva G, editors. Measuring Attitudes Cross-Nationally Lessons From the European Social Survey. Los Angeles: Sage; 2007. pp. 33–52. [Google Scholar]

- Hakim C. Work-Lifestyle Choices in the 21st Century: Preference Theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Hank K. “Regional Social Contexts and Individual Fertility Decisions: A Multilevel Analysis of First and Second Births in Western Germany”. European Journal of Population. 2002;18:281–99. [Google Scholar]

- Hoem J. “The Impact of Education on Modern Family-Union Initiation”. European Journal of Population. 1986;2:113–33. [Google Scholar]

- Hoem JM, Neyer G, Andersson G.2006a“Education and Childlessness. The Relationship Between Educational Field, Educational Level, and Childlessness Among Swedish Women Born in 1955–59” Demographic Research 14Article 15331–80.Available online at http://www.demographic-research.org/Volumes/Vol14/15 [Google Scholar]

- Hoem JM, Neyer G, Andersson G.2006b“Educational Attainment and Ultimate Fertility Among Swedish Women Born in 1955–59” Demographic Research 14Article 16381–404.Available online at http://www.demographic-research.org/Volumes/Vol14/16 [Google Scholar]

- Jansen M, Kalmijn M. “Emancipatiewaarden en de levensloop van jong-volwassen vrouwen: een padanalyse van wederzijdse invloeden” [Emancipatory values and the life courses of young adult women: A path analysis of mutual influences] Sociologische Gids. 2000;47:293–314. [Google Scholar]

- Jowell R, the Central Co-ordinating Team . Centre for Comparative Social Surveys; City University, London: 2005. “European Social Survey 2004/2005: Technical Report.”. [Google Scholar]

- Jowell R, Roberts C, Fitzgerald R, Eva G, editors. Los Angeles: Sage; 2007. Measuring Attitudes Cross-Nationally: Lessons From the European Social Survey. [Google Scholar]

- Jurajda S. “Gender Wage Gap and Segregation in Enterprises and the Public Sector in Late Transition Countries”. Journal of Comparative Economics. 2003;31:199–222. [Google Scholar]

- Kalmijn M. “Effecten van opleidingsniveau, duur en richting op het tijdstip waarop paren hun eerste kind krijgen” [Effects of educational level, school enrollment and type of schooling on the timing of the first birth] Bevolking en Gezin. 1996;1996:41–71. [Google Scholar]

- Kline RB. Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. 2nd ed. New York: Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Kravdal Ø. “The Importance of Economic Activity, Economic Potential and Economic Resources For the Timing of First Births in Norway”. Population Studies. 1994;48:249–67. [Google Scholar]

- Kravdal Ø.2004“An Illustration of the Problems Caused by Incomplete Education Histories in Fertility Analyses.” Demographic ResearchSpecial Collection 3, Article 6:133–54.Available online at http://www.demographic-research.org/special/3/6

- Lappegård T.2002“Educational Attainment and Fertility Patterns Among Norwegian Mothers.”Document 2002/18. Statistics Norway; Oslo [Google Scholar]

- Lappegård T, Rønsen M. “The Multifaceted Impact of Education on Entry Into Motherhood”. European Journal of Population. 2005;21:31–49. [Google Scholar]

- Liefbroer AC, Corijn M. “Who, What, Where, and When? Specifying the Impact of Educational Attainment and Labour Force Participation on Family Formation”. European Journal of Population. 1999;15:45–75. doi: 10.1023/a:1006137104191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillard LA. “Simultaneous Equations for Hazards: Marriage Durations and Fertility Timing”. Journal of Econometrics. 1993;56:198–217. doi: 10.1016/0304-4076(93)90106-f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lillard LA, Waite LJ. “A Joint Model of Marital Childbearing and Marital Disruption”. Demography. 1993;30:653–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Machin S, Puhani PA. “Subject of Degree and the Gender Wage Differential: Evidence From the UK and Germany”. Economics Letters. 2003;79:393–400. [Google Scholar]

- Mandel H, Semyonov M. “A Welfare State Paradox: State Interventions and Women’s Employment Opportunities in 22 Countries”. American Journal of Sociology. 2006;111:1910–49. [Google Scholar]

- Marini MM. “Women’s Educational Attainment and the Timing of Entry Into Parenthood”. American Sociological Review. 1984;49:491–511. [Google Scholar]

- Martin SP. “Diverging Fertility Among U.S. Women Who Delay Childbearing Past Age 30”. Demography. 2000;37:523–33. doi: 10.1353/dem.2000.0007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martín-García T, Baizán P. “The Impact of the Type of Education and of Educational Enrolment on First Births”. European Sociological Review. 2006;22:259–75. [Google Scholar]

- Moors G.1997“The Dynamics of Values-Based Selection and Values Adaptation.”Doctoral dissertation. Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB), Centrum voor Sociologie, Brussels.

- Morgan SP, Waite LJ. “Parenthood and the Attitudes of Young Adults”. American Sociological Review. 1987;52:541–47. [Google Scholar]

- Neyer G, Hoem J. “Education and Permanent Childlessness: Austria vs. Sweden. A Research Note.”. In: Surkyn J, Deboosere P, Van Bavel J, editors. Demographic Challenges for the 21st Century A State of the Art in Demography (Liber Amicorum Ron Lesthaeghe) Brussels: VUB/Academia Press; 2008. pp. 91–112. [Google Scholar]

- R Development Core Team . R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Rindfuss RR, Guzzo KB, Morgan SP. “The Changing Institutional Context of Low Fertility”. Population Research and Policy Review. 2003;22:411–38. [Google Scholar]

- Rindfuss RR, Morgan SP, Offutt K. “Education and the Changing Age Patterns of American Fertility: 1963–1989”. Demography. 1996;33:277–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rindfuss RR, Morgan SP, Swicegood G. First Births in America: Changes in the Timing of Parenthood. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press; 1988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singer JD, Willett JB. Applied Longitudinal Data Analysis Modeling Change and Event Occurrence. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Skirbekk V, Kohler H-P, Prskawetz A. “Birth Month, School Graduation, and the Timing of Births and Marriages”. Demography. 2004;41:547–68. doi: 10.1353/dem.2004.0028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobotka T. Postponement of Childbearing and Low Fertility in Europe. Groningen and Amsterdam: Rijksuniversiteit Groningen and Dutch University Press; 2004. [Google Scholar]