Abstract

I use hazard regression methods to examine how the age difference between spouses affects their survival. In many countries, the age difference between spouses at marriage has remained relatively stable for several decades. In Denmark, men are, on average, about three years older than the women they marry. Previous studies of the age gap between spouses with respect to mortality found that having a younger spouse is beneficial, while having an older spouse is detrimental for one’s own survival. Most of the observed effects could not be explained satisfactorily until now, mainly because of methodological drawbacks and insufficiency of the data. The most common explanations refer to selection effects, caregiving in later life, and some positive psychological and sociological effects of having a younger spouse. The present study extends earlier work by using longitudinal Danish register data that include the entire history of key demographic events of the whole population from 1990 onward. Controlling for confounding factors such as education and wealth, results suggest that having a younger spouse is beneficial for men but detrimental for women, while having an older spouse is detrimental for both sexes.

In recent years, the search for a single determinant of lifespan, such as a single gene or the decline of a key body system, has been superseded by a new view (Weinert and Timiras 2003). Lifespan is now seen as an outcome of complex processes with causes and consequences in all areas of life, in which different factors affect the individual lifespan simultaneously. Today’s standard of knowledge is that about 25% of the variation of the human lifespan can be attributed to genetic factors and about 75% can be attributed to nongenetic factors (Herskind et al. 1996). Research focusing on nongenetic determinants of lifespan has suggested that socioeconomic status, education, and smoking and drinking behavior have a major impact on individual survival (e.g., Christensen and Vaupel 1996). Mortality of individuals is also affected by characteristics of their partnerships. Partnership, as a basic principle of human society, represents one of the closest relationships individuals experience during their lifetimes. Regarding predictors of their mortality, partners usually share many characteristics, such as household size, financial situation, number of children, and quality of the relationship, but several factors might affect partners differently—for example, education and social status. A factor that might influence partners in different ways is the age gap between them.

BACKGROUND

To describe age dissimilarities between spouses, three different theoretical concepts have evolved over recent decades. The most common concept is homogamy or assortative mating, which presumes that people, predisposed through cultural conditioning, seek out and marry others like themselves. One assumption is that a greater age gap is associated with a higher marital instability. A further prominent concept is marriage squeeze, which states that the supply and demand of partners forces the individuals to broaden or narrow the age range of acceptable partners. A third and less common concept is the double standard of aging, which assumes that men are generally less penalized for aging than women. This assumption is supported by a greater frequency of partnerships of older men with younger women and much more variability in men’s age at marriage than in women’s (Berardo, Appel, and Berardo 1993).

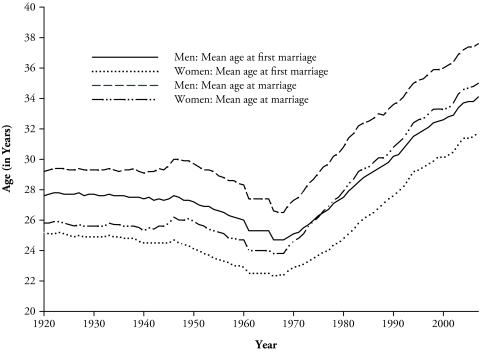

The age difference between spouses at marriage has remained relatively stable for several decades in many countries, a fact that was described by Klein (1996) as an almost historical pattern. An example for such a stable pattern is shown in Figure 1. It shows that, considering all marriages, Danish men are, on average, three years older at the time of their marriage than women. If only first marriages are considered, the gap between the sexes is a little smaller. While the mean age at marriage increased by about six years during the twentieth century, especially since the end of the 1960s, the age difference between the sexes increased only slowly in the first 50 years of the twentieth century and started to decrease again in the second half of the century. Today, the difference between the mean age at marriage of Danish men and women is only slightly smaller than it was at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Figure 1.

Mean Age at Marriage in Denmark, 1920–2007

Source: Compiled by author from data in Statbank Denmark (2007).

At the same time, marriage behavior in Denmark changed dramatically in nearly all other aspects, especially because cohabitation without marriage and divorce became more widespread. In 1901, the Danish Statistical Office counted 376 divorces. From then on, the number of divorces increased steadily and reached its peak in 2004 with 15,774 registered divorces. This increase in the number of divorces as an alternative to end a marriage is important because it reflects dramatic changes in the way marriages are dissolved. Until the early 1920s, more than 90% of all marriages in Denmark were dissolved by the death of one of the spouses. This proportion decreased with time. Today, only about 55% of all marriages are dissolved by the death of a spouse, and about 45% end in divorce.

Generally, most marriages that are dissolved by the death of one of the spouses end by the death of the husband. This is a universal pattern because men are not only older at the time of marriage but also die younger as compared with women (Luy 2002). At the beginning of the twentieth century, about 58% of all Danish marriages dissolved by death ended due to the death of the husband, and about 42% ended by the death of the wife. In the course of the twentieth century, Danish life expectancy increased for both sexes but rose more quickly for women. While the difference in life expectancy between the sexes at age 18 was about 2.5 years in 1900, it was about 4.3 years in 2005 (Human Mortality Database 2008). This increase led to an increase of about 10% in the proportion of marriages that were dissolved by the death of the husband. Today, about two-thirds of all marriages that are dissolved by death end due to the death of the husband, and only one-third end by the death of the wife.

Studies considering the impact of age differences between the partners on their mortality are rare and relatively dated. Rose and Benjamin (1971) made one of the first attempts to quantify the influence of a spousal age gap on men’s longevity. The authors found a correlation between longevity and having a younger wife, which was the 13th highest among all 69 variables they studied in their analysis.

The first study that considered the impact of an age gap on both sexes was conducted by Fox, Bulusu, and Kinlen (1979). The authors concluded that “conformity to the social norm, of the man being older than his wife, is associated with relatively lower mortality for both parties,” while differences from this norm, especially if they are extreme, lead to higher mortality (p. 126). They speculated that this pattern might be driven by the different characteristics of those who form these unusual partnerships.

In the 1980s, two studies provided further insights into this topic. Foster, Klinger-Vartabedian, and Wispé (1984) studied the effect of age differences on male mortality, and Klinger-Vartabedian and Wispé (1989) focused on females. Both studies used the same data and generally supported earlier findings. They conceded that results regarding larger age gaps should be interpreted with caution, mainly due to insufficient data. Because the direction of the observed effects were about the same, Foster et al. (1984) and Klinger-Vartabedian and Wispé (1989) drew similar conclusions. The first possible explanation, that healthier or more active individuals are selected by younger men or women, was already mentioned by Fox et al. (1979). Such individuals would have lived longer whomever they married because physical vitality and health usually coincides with an increased longevity. Another possible outcome of selection is that physical needs are better taken care of in later life for persons married to younger spouses. The second possible explanation refers to spousal interaction. It is speculated that there might be something psychologically, sociologically, or physiologically beneficial about a relationship with a younger spouse. Furthermore, it could be that intimate involvement with a younger spouse enlivens anybody’s chances for a longer life. This explanation directly refers to psychological determinants of mortality such as social and interpersonal influences, happiness, self-concept, and social status.

The major drawbacks of all these studies are that their data were limited to five-year age groups, that the authors did not include any information about additional variables (such as duration of the marriage), and that they were limited to married couples. The missing information on the duration of the marriage could lead to a selection bias because it is uncertain whether the marriages in the samples were of sufficient duration to allow for any effects on mortality. Foster et al. (1984) stated that an unobserved significant relationship between marriage duration and age of the spouse could question the generality of the observed mortality differentials.

In two more-recent publications, historical data were used to identify a mortality pattern by the age of a spouse. Williams and Durm (1998) basically replicated the results of the studies mentioned earlier, but their study also faced the same limitations. Kemkes-Grottenthaler (2004) used a set of 2,371 family-related entries dating from 1688 to 1921 from two neighboring parishes in Germany. She showed that the mortality differentials were not only determined by the age gap itself but were also affected by several covariates, such as socioeconomic status and reproductive output. Regarding socioeconomic status, she found that age heterogamy was much more prevalent in upper classes. In contrast, the reviews of Berardo et al. (1993) and Atkinson and Glass (1985) concluded that age heterogamy was more common among lower classes and not more common among the more highly educated. However, although findings are mixed, research indicates that confounding factors like socioeconomic status are of critical importance for the analysis of the mortality differentials attributable to the age gap between spouses.

In sum, previous research found that having a younger spouse is beneficial, while having an older spouse is detrimental for the survival chances of the target person. Most of the observed effects could not be explained satisfactorily until now, mainly because of methodological drawbacks and insufficiency of the data. The most common explanations refer to health selection effects, caregiving in later life, and some positive psychological and sociological effects.

RESEARCH QUESTIONS AND HYPOTHESES

In this section, I develop some hypotheses about the relationship between the spousal age gap and the risk of dying. In my model, exposure to risk of mortality depends on the individual’s own resources, those of their spouse, and their gender. Previous limitations are addressed by using detailed Danish register data in a time-dependent framework using hazard regression.

For men, the findings regarding the age gap to the spouse are relatively consistent: namely, that male mortality increases when the wife is older and decreases when the wife is younger. Previous research also indicated that mortality by the age gap to the spouse differs between the sexes, but none of the authors proposed reasons for this effect (Kemkes-Grottenthaler 2004; Williams and Durm 1998). The most common explanations of mortality differences by age gap to the spouse—health selection, caregiving in later life, and positive psychological effects of having a younger spouse—do not suggest large differences between the sexes. Thus, I hypothesize a similar pattern for women: namely, that the chance of dying increases when the husband is older and decreases when the husband is younger.

I also hypothesize that the duration of marriage has an impact on the mortality differentials by the age gap to the spouse. Previous studies speculated that marriages should be of sufficient duration to allow for any effects on mortality. This reasoning suggests that the mortality advantage of individuals who are younger than their spouses should not be observable in marriages of short duration.

In addition, I analyze the impact of socioeconomic status. Previous research (e.g., Kemkes-Grottenthaler 2004) indicated that the frequency of age heterogamy differs by social class. Generally, more highly educated persons and individuals with greater wealth are known to experience lower mortality, but no study has analyzed whether these socioeconomic variables might have an impact on the survival differentials by the age gap to the spouse. If the frequency of age heterogamy differs by social class, it could partially explain these survival differentials. Thus, I hypothesize that the socioeconomic characteristics of the target person and his or her spouse will change the effect of the age gap to the spouse on the target person’s mortality.

Previous research has argued that social norms and cultural background can explain the mortality differentials. Although Denmark is known to be a very homogeneous country, it is likely that social norms may differ between Danish and non-Danish as well as between rural and urban areas. Thus, I hypothesize that mortality by age gap to the spouse might differ by place of residence and by citizenship of the target person.

DATA AND METHODS

Data

Denmark is among the countries with the most sophisticated administration systems worldwide (Eurostat 1995). All persons living in Denmark have a personal identification number that is assigned at birth or at the time of immigration. This personal identification was a crucial part of the 1968 Population Registration Act, which introduced a computerized Central Population Register. This register serves as the source register for almost all major administrative systems in Denmark, which means that most registers can be linked by using the personal identification number. Today, many different authorities maintain about 2,800 public personal registers on almost all aspects of life. While the majority of these registers are administrative, a small proportion can be used for statistical or research purposes. Generally, the Danish registers are considered a source of detailed and exact information with a very low percentage of missing data. For this study, individual-level data from five different registers are linked with one another through the personal identification number. An overview of registers that are used for this analysis is shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Registers and Variables That Are Used in This Analysis

| Name of Register | Variables |

|---|---|

| Family Register | Sex, date of birth, marital status, personal identification number of the partner, citizenship, municipality of residence |

| Register of Deaths | Date of death |

| Migration Register | Date of migration, type of migration |

| Education Register | Highest achieved educational degree |

| Income Register | Wealth |

The register extract I use here covers the period between 1990 and 2005. The information from the Register of Deaths and the Migration Register are given on a daily basis, meaning that the exact day of the event is known. The information from the Family Register, the Education Register and the Income Register is only updated annually, which means that the data are based on the individual’s status at January 1 of each year during the observation period.

The variables personal identification number of the partner, wealth, municipality of residence, and citizenship were coded as time-varying covariates. The covariate age gap to the spouse is also time-varying but was computed from existing variables. The variable sex is a time-constant covariate by nature, while education was assumed to be time-constant despite its inherently time-varying nature. My data set includes only people aged 50 and over. At these advanced ages, education is unlikely to change, so this approach should give approximately the same results. The remaining variables, marital status, date of migration, and type of migration, as well as date of birth and date of death, were used to define the time periods under risk.

The base population of my analysis is all married people aged 50 years and older living in Denmark between January 1, 1990, and December 31, 2005. There are three ways for individuals to enter the study: (1) being married and 50 years old or older on January 1, 1990; (2) being married and becoming 50 years old between January 2, 1990, and December 31, 2005; and (3) immigrating to Denmark between January 1, 1990, and December 31, 2005, and being married, and being 50 years or older.

There are five possible ways to exit the study: (1) dying between January 1, 1990, and December 31, 2005; (2) divorcing between January 1, 1990, and December 31, 2005; (3) becoming widowed between January 1, 1990, and December 31, 2005; (4) being alive on December 31, 2005; and (5) emigrating from Denmark between January 1, 1990, and December 31, 2005.

Methods

I apply hazard regression models to examine the influence of the age gap to the spouse on the individual’s mortality. Hazard regression, also called event-history analysis or survival analysis, represents the most suitable analytical framework for studying the time-to-failure distribution of events of individuals over their life course. The general proportional hazards regression model is expressed by

| (1) |

where h(t | X1,…,Xk) is the hazard rate for individuals with characteristics X1,…,Xk at time t, h0(t) the baseline hazard at time t, and βj, j = 1,…,k, are the estimated coefficients of the model.

Since the failure event in our analysis is the death of the individual, the baseline hazard of our model h0(t) is age, measured as time since the 50th birthday. It is assumed to follow a Gompertz distribution, defined as

| (2) |

where γ and β0 are ancillary parameters that control the shape of the baseline hazard. The Gompertz distribution, proposed by Benjamin Gompertz in 1825, has been widely used by demographers to model human mortality data. The exponentially increasing hazard of the Gompertz distribution is a useful approximation for ages between 30 and 95. For younger ages, mortality tends to differ from the exponential curve due to infant and accident mortality. For advanced ages, the increase in the risk of death tends to decelerate so that the Gompertz model overestimates mortality at these ages (Thatcher, Kannisto, and Vaupel 1998). I assume that the impact of this deceleration on my results is negligible because the number of married people over age 95 is extremely low.

The research plan was to test whether the age difference between the spouses affected both sexes in the same way. Therefore, all regression models were calculated for females and males separately. It should be noted that the male and female models do not necessarily include the same individuals. If both spouses are aged 50 or older, a couple is included in all models. If only the husband is 50 years or older, a couple is included only in the male models. Correspondingly, a couple is only included in the female models if the wife is 50 years or older and the husband is 49 years or younger.

RESULTS

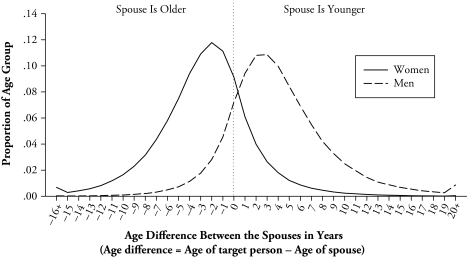

In total, 1,845,956 married individuals aged 50 and older are included in the data set; 958,997 of them are male, 886,959 female. The distribution of all persons in the data set by age gap to the spouse is presented in Figure 2. It shows that most men are between two and three years older than their wives, while most women are two years younger than their husbands.

Figure 2.

Distribution of Age Gap to the Spouse

Source: Compiled by author with data from Statistics Denmark (2007).

Approximately 75% of all married men aged 50 and over are married to women who are more than one year younger than themselves; only 10% of all men are at least one year younger than their wives. In contrast, the majority of married women (65%) aged 50 years and over are married to men who are older than themselves, and only 15% have a spouse who is more than one year younger.

Table 2 gives descriptive information on all covariates. It shows the distribution of time at risk measured in days for men and women. In total, I observed 3,271 million person-days for men and 2,907 million person-days for women. The proportion of missing information is highest for duration of marriage. This is because the date of marriage is unknown for all couples who married before January 1, 1990. These couples were assigned to the category unknown for 1,000 days when entering the study population and to the category ≥ 1,000 days thereafter. A large number of missing values is also found for the variables highest achieved education and highest achieved education of the spouse, with the proportion missing data increasing for older cohorts. I find no indication that this effect influenced the outcome of the regression models.

Table 2.

Distribution of Time at Risk for Men and Women

| Covariate | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|

| Duration of Marriage | ||

| Unknown | 15.92 | 15.76 |

| < 1,000 days | 1.55 | 1.16 |

| ≥ 1,000 days | 82.53 | 83.08 |

| All | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Period | ||

| 1990–1994 | 29.37 | 29.09 |

| 1995–1999 | 31.19 | 31.10 |

| 2000–2005 | 39.44 | 39.81 |

| All | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Highest Achieved Education | ||

| Low | 32.42 | 48.12 |

| Medium | 37.31 | 28.55 |

| High | 16.80 | 13.28 |

| Unknown | 13.47 | 10.05 |

| All | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Wealth in Danish Krones | ||

| < 0 | 17.57 | 18.12 |

| > 0 and ≤ 100,000 | 17.53 | 44.09 |

| > 100,000 | 64.47 | 30.81 |

| 0 or Unknown | 0.43 | 6.98 |

| All | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Highest Achieved Education of the Spouse | ||

| Low | 47.15 | 32.21 |

| Medium | 29.57 | 35.98 |

| High | 14.17 | 16.10 |

| Unknown | 9.12 | 15.71 |

| All | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Residential Area | ||

| Copenhagen | 84.81 | 84.47 |

| Remaining Denmark | 15.19 | 15.53 |

| All | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Citizenship | ||

| Danish | 98.40 | 98.41 |

| Non-Danish | 1.60 | 1.59 |

| All | 100.00 | 100.00 |

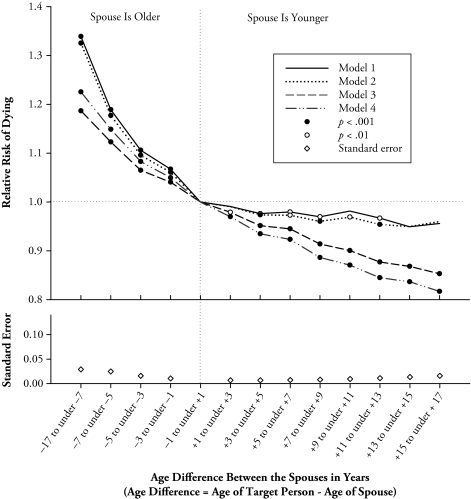

In the following paragraphs, I present the results of four estimated hazard regression models. For men, the relative risk of dying by the age gap to the spouse and the standard errors of the fourth model are shown in Figure 3. The corresponding results for women are shown in Figure 4. Both figures consist of four separate curves showing the relative risk of dying by age gap to the spouse. The reference category, represented by a dotted vertical line, includes all persons who are less than one year younger or older than their spouses. The part of each curve to the left of the reference category relates to individuals with older spouses, the right part relates to individuals with younger spouses. I show only the standard errors of the fourth model because they were virtually the same for all four models. For both sexes, the results of the additional covariates are presented in Table 3.

Figure 3.

Relative Risk of Dying for Men, by Age Gap to the Spouse

Source: Compiled by author with data from Statistics Denmark (2007).

Figure 4.

Relative Risk of Dying for Women, by Age Gap to the Spouse

Source: Compiled by author with data from Statistics Denmark (2007).

Table 3.

Effect of the Additional Covariates on the Hazard of Mortality

| Covariate | Men |

Women |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 | |

| Duration of Marriage | ||||||

| Unknown | 0.78*** (0.018) | 0.78*** (0.018) | 0.76*** (0.018) | 0.79*** (0.029) | 0.74*** (0.028) | 0.75*** (0.028) |

| < 1,000 days | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| ≥ 1,000 days | 0.77*** (0.017) | 0.89*** (0.020) | 0.87*** (0.020) | 0.80*** (0.029) | 0.79*** (0.028) | 0.80*** (0.029) |

| Period | ||||||

| 1990–1994 | 1.09*** (0.007) | 1.07*** (0.007) | 1.07*** (0.007) | 1.07*** (0.010) | 1.00 (0.010) | 1.00 (0.010) |

| 1995–1999 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| 2000–2005 | 0.85*** (0.004) | 0.86*** (0.005) | 0.86*** (0.005) | 0.87*** (0.006) | 0.95*** (0.007) | 0.95*** (0.007) |

| Highest Achieved Education | ||||||

| Low | 1.07*** (0.007) | 1.04*** (0.007) | 1.13*** (0.010) | 1.12*** (0.011) | ||

| Medium | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | ||

| High | 0.83*** (0.007) | 0.87*** (0.008) | 0.86*** (0.013) | 0.89*** (0.014) | ||

| Wealth | ||||||

| Low | 1.39*** (0.010) | 1.39*** (0.010) | 1.18*** (0.012) | 1.18*** (0.012) | ||

| Medium | 1 | 1 | ||||

| High | 0.58*** (0.003) | 0.57*** (0.003) | 0.64*** (0.005) | 0.64*** (0.005) | ||

| Highest Achieved Education of the Spouse | ||||||

| Low | 1.08*** (0.007) | 1.05*** (0.010) | ||||

| Medium | 1 | 1 | ||||

| High | 0.88*** (0.009) | 0.91*** (0.012) | ||||

| Residential Area | ||||||

| Copenhagen | 0.97*** (0.005) | 1.12*** (0.009) | ||||

| Remaining Denmark | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Citizenship | ||||||

| Danish | 1.29*** (0.028) | 1.19*** (0.038) | ||||

| Non-Danish | 1 | 1 | ||||

| Constant | –16.34 | –16.52 | –16.79 | –16.56 | –16.52 | –16.70 |

| Gamma | 0.00028 | 0.00029 | 0.00030 | 0.00027 | 0.00027 | 0.00027 |

Notes: Numbers in parentheses are standard errors. Models also include missing categories. Full results are available from the author.

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

As a first step, I estimated a model (Model 1) that allowed me to replicate the results of previous studies by including age gap to the spouse as sole covariate. Thus, this model controls only for the age of the target person and age gap to the spouse.

Figure 3 shows that the risk of dying in men decreases as the age gap increases. The younger the wife is compared with her spouse, the lower the mortality of the husband; the older the wife is compared with her spouse, the higher the mortality of the husband. Compared with the reference category, an excess mortality of more than 30% can be found in married men who are more than 7 years but less than 17 years younger than their wives. Married men who are more than 15 years but less than 17 years older have a chance of dying that is 4% lower.

Figure 4 shows that, similar to that of men, female mortality is higher if the wife is younger than her husband. Women who are more than 7 years but less than 17 years younger have an excess mortality of about 10%. In contrast to the pattern for men, women also have an elevated risk of dying when they are older than their spouses. Compared with the reference category, an excess mortality of 40% is observed in women who are more than 15 years but less than 17 years older than their spouses. The lowest risk of dying is found in women who are about the same age as their husbands, which is the reference category.

These first results provide strong evidence that the age difference between the spouses affects individual survival chances. It also shows that the effects are substantially different between the sexes. Next, in Models 2, 3, and 4, I examine the impact of the age gap to the spouse in the presence of additional covariates.

Previous research had no information on the duration of marriage, which could lead to a possible selection bias. Model 2, which includes duration of marriage, allows me to test for the confounding effect of duration of marriage. A comparison of the coefficient for the age gap to the spouse in Model 1 and Model 2 shows that including the measure of marriage duration does not change the coefficients for the age gap to the spouse, suggesting that duration of marriage does not account for the mortality differences of age-discrepant marriages. In results not shown here, I tested an additional model that included an interaction between age gap to the spouse and duration of marriage. None of the combinations between the two variables were statistically significant (at the .01 level).

In Model 3 of Table 3, I test the hypothesis that socioeconomic status affects the mortality differentials by the age gap to the spouse. This model includes measures of the target person’s highest educational degree and wealth as well as the variables already included in Model 2. The results show that both socioeconomic variables are important predictors of survival differences. Individuals with low education or low wealth face higher mortality rates. Comparing the relative risk by age gap to the spouse in Model 3 with the relative risk by age gap to the spouse in Model 2 reveals that holding the socioeconomic variables constant changes the effects for both sexes. For men, adding these measures to the model reduces the relative risk of dying when they are younger than their wives, but it increases the survival advantage when they are older than their wives. For women, adding measures of socioeconomic status has virtually no impact when they are younger than their husbands but slightly increases the chance of dying when they are older than their husbands. In results not shown here, I tested another model that included an interaction between the socioeconomic variables and the age gap to the spouse. One of the combinations was statistically significant (at the .01 level): men with high wealth and who are older than their wives experienced a significantly elevated risk of dying of about 5%. All remaining combinations between the variables were not statistically significant (at the .01 level).

Finally, I investigate the effect of the remaining variables residential area, citizenship, and highest achieved education of the spouse, which are introduced into the analysis in Model 4 of Table 3. In this model, I wanted to test the assumption that cultural differences and social norms—represented by the two variables residential area and citizenship—account for some of the differences in the hazard of mortality by the age gap to the spouse. Again, comparing the relative risk by age gap to the spouse in Model 4 with the relative risk by age gap to the spouse in Model 3 reveals differences by sex. For men, the hazard of mortality increases when they are younger than their wives and decreases further when they are older than their wives. In contrast, the hazard of mortality for women does not change for women who are younger than their husbands but decreases considerably for women who are older than their husbands.

DISCUSSION

The present study addresses an underdeveloped research area. Using Danish population data, I used hazard regression methods to exploit 15 years of age-specific data to investigate the effect of the age difference between the spouses on the individual’s survival. I showed for the first time that survival differences by age gap to the partner are not limited to extreme cases but are statistically significant for small age differences. Individuals who are about one to three years older than their spouses have a significantly different survival rate than individuals who are up to one year older or younger than their spouses.

My hypothesis that the effect would be the same in men and women receives no support from these analyses. My results suggest that having a younger spouse is beneficial for men but detrimental for women. It also shows that controlling for additional covariates affects the pattern for men substantially, while it has very little effect for women. The first possible reason for sex differences could be differences in health selection. The selection hypothesis argues that healthier individuals are able to attract younger partners. Therefore, married people who are older than their spouses should experience a lower mortality. It was also proposed in the literature that a younger spouse is somehow beneficial in terms of health care support as well as in some positive psychological and sociological ways. Both arguments should hold for both sexes similarly. The sex differences could indicate that health selection is weaker in women. Women are much less likely to marry a younger husband, which suggests that exceptionally healthy women are less able than their male counterparts to attract a younger partner. However, future analysis should include health indicators to investigate the pathway of a possible health selection in more detail.

A second reason for sex differences by age differences to the spouse is related to social support. A large body of research has found that women have generally more social contacts than men. This suggests that women are probably less dependent on the health support and social support of a younger spouse than are men, which means that a younger spouse would be less beneficial for women’s survival than for the survival of men.

In most marriages, men are older than their wives. Given my results, this composition favors men. Thus, the age gap between the spouses may in part explain why marriage is more beneficial for men than for women. My results also suggest that the possible selection bias caused by an insufficient length of partnership is of no importance in explaining the effects of the survival differences by the age gap to the spouse.

Previous research has suggested that selection and discrepancy from the social norm cause the mortality difference by the age gap to the spouse. This explanation was proposed in the 1970s, when social norms for mating behavior in general and especially for the age difference between partners were probably much stronger than today. My investigation supports this explanation for men but not for women. If social norms for the age gap to the spouse were the driving force of the observed mortality differentials, female mortality could be assumed to be lowest at ages where women are a few years younger than their spouses. Here, I find that mortality in women is lowest when a woman is the same age as her husband and increases with increasing age discrepancy.

I extend previous research of this area in several aspects. First, I apply a longitudinal approach. By using the Danish registers, it is possible to track all individuals from the date of their marriage until their date of death and to incorporate all life events—such as the death of the spouse, a divorce, or a remarriage—into the analysis of events within the observed period. The longitudinal approach avoids some of the drawbacks of earlier studies.

Another limitation of previous research that I overcame in this study is the age grouping into five-year age groups. Because of the age grouping in earlier studies, each of the spouse-age-difference intervals covered an eight-year period. Spouses who were stated as being in the same age group could differ plus or minus four years, while the difference for an individual who is married to a spouse in the neighboring age group varies from one to nine years. Thus, the age groups are not only wide but also overlapping. In my data set, the exact date of birth is known for every individual; thus, age and the age gap to the spouse are measured in days.

A further extension of previous research is also related to the data set. My study uses population data/register data, not samples as were used in previous research, to test these hypotheses. I was thus able to avoid many problems related to sampling methods while substantially increasing the statistical power.

It can be concluded that the driving force of the observed mortality differences by the age gap to the spouse remain unclear. Further research is necessary using models that test for additional multiplicative effects as well as for unobserved heterogeneity. A short coming of this study is that it does not include any behavioral or psychological aspects of the married couple because the data came from administrative registers. Future research should point in this direction as it is assumed to be of importance to account better for social values and norms as well as certain behavioral aspects.

Further research directions are of possible interest. In general, the age gap to the partner should affect the survival chances of members in all kinds of longtime partnerships between two individuals. Due to data limitations, studies, including the present one, have had to focus on married couples exclusively. In a next step, it might be of interest to know whether the effects of the age gap to the partner can also be observed in longtime cohabiting couples or other kinds of partnerships, especially in same-sex couples. The Danish data that are now available permit such analyses.

Acknowledgments

This work was conducted at the Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research, Rostock. I would also like to thank the Institute of Public Health, University of Southern Denmark, Odense. I am especially grateful to James W. Vaupel for his support and guidance and Heiner Maier for his helpful comments on this manuscript. A previous version of this manuscript was presented at the 2008 annual meeting of the Population Association of America in New Orleans, LA.

REFERENCES

- Atkinson MP, Glass BL. “Marital Age Heterogamy and Homogamy, 1900 to 1980”. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1985;47:685–91. [Google Scholar]

- Berardo FM, Appel J, Berardo DH. “Age Dissimilar Marriages: Review and Assessment”. Journal of Aging Studies. 1993;7:93–106. [Google Scholar]

- Christensen K, Vaupel JW. “Determinants of Longevity: Genetic, Environmental and Medical Factors”. Journal of Internal Medicine. 1996;240:333–41. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.1996.d01-2853.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eurostat . Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities; 1995. Statistics on Persons in Denmark. A Register-Based Statistical System. [Google Scholar]

- Foster D, Klinger-Vartabedian L, Wispé L. “Male Longevity and Age Differences Between Spouses”. Journal of Gerontology. 1984;39:117–20. doi: 10.1093/geronj/39.1.117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox AJ, Bulusu L, Kinlen L. “Mortality and Age Differences in Marriage”. Journal of Biosocial Science. 1979;11:117–31. doi: 10.1017/s0021932000012177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herskind AM, McGue M, Holm NV, Sorensen TIA, Harvald B, Vaupel JW. “The Heritability of Human Longevity: A Population-Based Study of 2,872 Danish Twin Pairs Born 1870–1900”. Human Genetics. 1996;97:319–23. doi: 10.1007/BF02185763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Human Mortality Database 2008University of California, Berkeley (USA), and Max Planck Institute for Demographic Research (Germany)Available online at http://www.mortality.org

- Kemkes-Grottenthaler A. “‘For Better or Worse, Till Death Us Do Part’: Spousal Age Gap and Differential Longevity: Evidence From Historical Demography”. Collegium Antropologicum. 2004;28:203–19. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Klein T. “Der Altersunterschied Zwischen Ehepartnern. Ein Neues Analysemodell” [Agedifferences between marital partners A new analytic model] Zeitschrift fuer Soziologie. 1996;25:346–70. [Google Scholar]

- Klinger-Vartabedian L, Wispé L. “Age Differences in Marriage and Female Longevity”. Journal of Marriage and the Family. 1989;51:195–202. [Google Scholar]

- Luy M. “Die geschlechtsspezifischen Sterblichkeitsunterschiede—Zeit für eine Zwischenbilanz” [Sex differences in mortality—Time to take a second look] Zeitschrift für Gerontologie und Geriatrie. 2002;35:412–29. doi: 10.1007/s00391-002-0122-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rose CL, Benjamin B. Predicting Longevity. Lexington: D. C. Heath and Company; 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Statistics Denmark 2007Statbank Denmark. Statistics Denmark, Copenhagen (Denmark)Available online at http://www.statbank.dk

- Thatcher AR, Kannisto V, Vaupel JW. Monographs on Population Aging. Odense: Odense University Press; 1998. “The Force of Mortality at Ages 80 to 120”. [Google Scholar]

- Weinert BT, Timiras PS. “Theories of Aging”. Journal of Applied Physiology. 2003;95:1706–16. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00288.2003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams CL, Durm MW. “Longevity in Age-Heterogamous Marriages”. Psychological Reports. 1998;82:872–74. doi: 10.2466/pr0.1998.82.3.872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]