Abstract

We construct demographic models of retirement and death in office of U.S. Supreme Court justices, a group that has gained demographic notice, evaded demographic analysis, and is said to diverge from expected retirement patterns. Models build on prior multistate labor force status studies, and data permit an unusually clear distinction between voluntary and “induced” retirement. Using data on every justice from 1789 through 2006, with robust, cluster-corrected, discrete-time, censored, event-history methods, we (1) estimate retirement effects of pension eligibility, age, health, and tenure on the timing of justices’ retirements and deaths in office, (2) resolve decades of debate over the politicized departure hypothesis that justices tend to alter the timing of their retirements for the political benefit or detriment of the incumbent president, (3) reconsider the nature of rationality in retirement decisions, and (4) consider the relevance of organizational conditions as well as personal circumstances to retirement decisions. Methodological issues are addressed.

This article constructs demographic models of retirement and death in office of U.S. Supreme Court justices from 1789 through 2006. We use these models to exploit unique features of Supreme Court appointments and data for three purposes. First, we examine determinants of labor force exit by mortality and retirement in this “small but extremely important social group” (Preston 1977:171) that has escaped prior demographic analysis, even as its retirement and mortality patterns have captured demographic notice and popular attention (e.g., Garrow 1998; Greenhouse 2007; Toobin 2007; USA Today 2007; Woodward and Armstrong 1979). Others have argued that justices tend to delay retirement from the Court in purposeful disregard for their old age, “decrepit” health (Garrow 2000), and superannuated tenure (Epstein et al. 2006; Yoon 2006; also see Table 1 and discussion below), in spite of generous pension benefits. To assess these claims, we estimate the effects of age, vitality, job tenure, and pension benefit eligibility on Supreme Court justice retirement. Second, we reconsider the inconsistent findings of more than 70 years of rancorous debate in historical, legal, and political research concerning the politicized departure hypothesis, the assertion that Supreme Court justices tend to alter the timing of their retirements (and thereby indirectly alter their probabilities of death in office) for the benefit of the political parties of the presidents who appointed them (see Table 1 and discussion below). And third, we use the politicized departure hypothesis to reexamine the adequacy of “economic rationality” as the sole basis for understanding retirement decisions, and we consider the relevance of “value rationality” to understanding retirement decisions.

Table 1.

Selected Research on U.S. Supreme Court Departures

| Author | Main Method | Unit of Analysis | Relevant Conclusions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wallis (1936) | Goodness of fit | Supreme Court departures per year 1837–1932 | Number of departures per year follows Poisson distribution. |

| Fairman (1938) | Tabulation and narrative history | Justices 1789–1937 | Age and infirmity effects on retirement vary. Political influences rarely mentioned. Age limits proposed. |

| Goff (1960) | Narrative history | Justices 1789–1959 | Age and infirmity effects on retirement vary. Political influences sometimes mentioned. |

| Schmidhauser (1962) | Narrative history | Justices 1789–1961 | Age effects on retirement are weaker for judicial activists than for nonactivists. |

| Callen and Leidecker (1971) | Goodness of fit | Supreme Court departures per year 1837–1970 | Number of departures per year follows Poisson distribution. |

| Ulmer (1982) | Goodness of fit | Supreme Court departures per year 1790–1980 | Number of departures per year follows Poisson distribution. No effect of Court size. “Minimal” interdependence of departures. |

| King (1987) | Poisson regression | Supreme Court departures per year 1790–1984 | New appointments to Court temporarily lower rate of departures from Court; congressional turnover and major wars temporarily raise rate of departure. |

| Squire (1988) | Discrete-time event-history (with probit) | Justices 1789–1980 | Infirmity, pension eligibility, and low volume of written opinions raise individual retirement hazard. No effects of justice’s prior election to public office or congruence of current president’s party with party of president who appointed justice. |

| Hagle (1993) | Poisson regression | Supreme Court departures per year 1790–1991 | Fewer departures when more justices are former elected officials and when majority of justices are same party as Senate majority. More departures early in second presidential terms. |

| Van Tassel (1993) | Tabulation and narrative history | 190 federal judges retired not for age or health 1789–1993 | Describes and tabulates reasons for resignation or retirement (excluding age, health, and senior status). Describes political reasons (e.g., investigations and outside pressures). |

| Box-Steffensmeier and Zorn (1998) | Weibull and Cox failure time analyses | Justices 1789–1993 | No effect of partisan agreement between justice and president who appointed. Some findings that retirement hazard lower for justices who were Republicans or “critical nominations.” |

| Abraham (1999) | Narrative history | Justices 1789–1998 | Describes effects of infirmity and politics on retirement. |

| Atkinson (1999) | Narrative history | Justices 1789–1998 | Recent justices all left Court before becoming mentally decrepit. |

| Brenner (1999) | Tabulation and narrative history | Justices 1937–1991 | At most, 2 of 33 justices timed retirement for political reasons. |

| Yalof (1999) | Narrative history | Justices 1789–1998 | Describes political factors in the appointment process, especially departing justice’s characteristics and time of departure. |

| Garrow (2000) | Narrative history | Justices 1789–1999 | Finds evidence of mental decrepitude before retirement, especially in the twentieth century. Age limit proposed. |

| Zorn and Van Winkle (2000) | Weibull and Cox failure time analyses | Justices 1789–1992 | Frequency of opinion writing negatively associated with retirement and death hazards. Age, pension eligibility, and president’s second term raise retirement hazard. In Cox models only, death-in-office hazard is lower when justice’s party is same as party of president or Senate majority. |

| Ward (2004) | Narrative history | Justices 1789–2003 | Describes effects of politics and infirmity on retirement. |

| Yoon (2006) | Discrete-time event history (with probit) | Federal judges 1869–2002 | For Supreme Court, no effects for pension eligibility and judicial tenure. Seven of eight political variables not significant. When justice, president, and Senate all share the same party, a justice is less likely to retire, controlling for other party combinations. |

| Calabresi and Lindgren (2006b) | Odds ratios, polynomial regression | Justices 1789–2006 | Find higher relative odds of retiring versus dying in office based on whether the current and appointing presidents are of the same party. Graph trends in age and service. Increases in judicial tenure over time fitted by cubic regression. |

| Epstein et al. (2006) | Tabulation | Justices 1789–2006 | Describes retirement reasons. |

Our models of retirement and death in office build on previous multistate labor force status studies that directed attention concurrently to both death and retirement as modes of labor force exit (e.g., Land, Guralnik, and Blazer 1994; Schoen and Woodrow 1980). Our focus on Supreme Court justices (rather than a broader social group) builds on analyses that found occupational differences in both longevity (Fletcher 1983, 1988; Guralnik 1962; Johnson, Sorlie, and Backlund 1999; Kitagawa and Hauser 1973) and labor force exit by retirement and by death (Hayward and Hardy 1985; Hayward et al. 1989). Further, our concentration on Supreme Court justices extends a body of mortality research and labor force exit studies of very small social groups that are defined by their members’ high levels of achievement, influence, and power (e.g., Abel and Kruger 2005; Gavrilov and Gavrilova 2001; Hollander 1972; McCann 1972; Quint and Cody 1970; Redelmeier and Singh 2001a, 2001b; Treas 1977; Waterbor et al. 1988).1

Our focus on Supreme Court justices also helps to address three current methodological issues in retirement studies by applying the venerable demographic strategy of exploiting unusual data from special populations. First, general population survey respondents have a known tendency to misreport involuntary unemployment as voluntary retirement, thereby confounding these labor force statuses (Gustman, Mitchell, and Steinmeier 1995:S63; Stolzenberg 1989). However, this problem is obviated in Supreme Court analyses because justices are constitutionally protected from involuntary job termination.2

Second, because general population retirement data focus primarily on worker characteristics, especially health and finance (Hayward et al. 1989; Lumsdaine 1995; Lumsdaine, Stock, and Wise 1994; Moen, Kim, and Hofmeister 2001), analyses of general population data are precluded from investigating the effects on retirement of characteristics and organizational conditions of the employer organizations from which workers retire. The relevance of organizational conditions to retirement is hypothesized in organizational demography (Lawrence 1997; Stewman 1986) and is suggested indirectly by research on employer organization effects on other aspects of employment (Baron and Pfeffer 1994; Fujiwara-Greve and Greve 2000; Haveman 2000; Stewman 1986; Stolzenberg 1978). Because the president appoints justices to the Court, presidential political circumstances are part of the Court’s organizational environment, and changes in the political party of the incumbent president constitute important, directly observable changes in the Court’s organizational environment. We measure the effect of these environmental conditions on retirement patterns.

Third, unlike other retirement data, Supreme Court data permit examination of rationality in retirement decisions. Although our models follow the contemporary analytic focus on personal “economic rationality” of labor force participants as the basis for their retirement decisions (Lumsdaine 1995; Moen et al. 2001), the politicized departure hypothesis asserts that justices also tend to delay or accelerate their retirement without discernible personal health benefit or financial gain, for political benefit of the party of the president who appointed them to the Court. Although such behavior would not be “ economically” or “instrumentally” rational for individual justices (see, e.g., Vriend 1996), it would be consistent with the Weberian concept of value rationality (Kalberg 1980; Swidler 1973), that is, rational action in service to the actor’s values (see also Posner 1993).3 The concept of value rationality is not mentioned in previous research on Supreme Court retirement and death in office, but it is consistent with the politicized departure hypothesis.

Although this article is not undertaken to address specific policy questions concerning the Supreme Court, our findings bear on general questions about the political behavior of U.S. judges and debates about term limits for Supreme Court justices. Because Supreme Court decisions have such widespread effects, these controversies have extensive legal, political, and public policy implications that affect virtually every person, government, and organization in the United States, and many elsewhere.

The next section explains the politicized departure hypothesis, states it in testable form, and describes previous research on it. The sections that follow consider methods and measurement, report analyses, and discuss findings and their implications for the issues that motivate this research.

HYPOTHESIS AND PRIOR RESEARCH

By law, Supreme Court appointment is explicitly political, involving nomination and appointment by the president “with the Advice and Consent of the Senate” (U.S. Constitution, art. 2, sec. 2). But law dictates no role for presidents, politics, or public scrutiny in selecting the times at which justices vacate the Court: except in cases of treason, bribery, or other serious crimes, justices leave office only by death, or when they themselves, alone and individually, resign. Nonetheless, some observers have long asserted—and others have long denied—that the timing of justices’ resignations from the Court, and even the probability that they die in office, reflect a highly politicized process that, like their nominations, revolves around political compatibility between the individual jurist and the incumbent president of the United States (Biskupic 2004; Calabresi and Lindgren 2006a, 2006b; Caldeira et al. 1999; Neumann 2003; Ward 2003; Zorn and Van Winkle 2000) as well as personal circumstances of justices, such as vitality (i.e., health, wellness), age, personal finances, and job tenure (i.e., length of service on the Court; see, e.g., French 2005). We call this assertion the politicized departure hypothesis.

The politicized departure hypothesis is based on (1) the observation that a justice’s retirement—particularly if it occurs early in a president’s term of office—allows the incumbent president to nominate the replacement for that justice, (2) the belief that justices tend to be loyal to the party of the president who appointed them to the Court, and (3) the conjecture that justices tend to display this loyalty by timing their resignations to give a president of that party the opportunity to appoint their judicial successor (see Calabresi and Lindgren 2006a; Walker et al. 1996:368).4 Thus, the politicized departure hypothesis is as follows: (1) Other things equal, if the incumbent president is of the same party as the president who nominated the justice to the Court, and if the incumbent president is in the first two years of a four-year presidential term, then the justice is more likely to resign from the Court than at times when these two conditions are not met.

By removing live justices from office, accelerated departure reduces their opportunity to die in office. Retarded departure does the opposite. Thus, the hypothesis implies a corollary: (2) Other things equal, if the incumbent president is of the same party as the president who nominated the justice to the Court, then the justice is less likely to die in office than at times when this condition is not met.

Informal versions of the politicized departure hypothesis have generated much speculation in popular news media about the timing and determinants of future Supreme Court departures and opportunities for U.S. presidents to appoint new justices (e.g., Greenhouse 2007; USA Today 2007). In academic research, politicized departure is vigorously debated in more than 70 years of historical and quantitative literature (described below and in Table 1) that made virtually no connection to broader retirement and labor force exit research. After Fairman (1938), narrative studies have tended to focus selectively on specific justices whose Court departures appeared politically timed. For example, Goff (1960:96) argued that a senile Justice William Cushing remained in office until death in 1810 solely to prevent an appointment by a Democratic-Republican president. Van Tassel (1993), Atkinson (1999), Garrow (2000), and Ward (2003) provided historical evidence of politicized departure by particular justices. Farnsworth (2005:448) reported that Justices William Rehnquist and Sandra Day O’Connor (2005) stated preferences that their replacements be nominated by a president of the same party as the president who appointed them. Hutchinson (1998) reported similar statements by Justice Byron White. Justices Hugo Black, William Douglas, John Marshall, and William Brennan were reported to have delayed departure in unsuccessful attempts to give a Democratic president the opportunity to name their successors (Oliver 1986:806–808; Woodward and Armstrong 1979:161).

Although some narrative historical studies provided evidence that several justices acted as predicted by the politicized departure hypothesis, they leave three concerns. First, some narrative studies directly contradicted the politicized departure hypothesis (e.g., Brenner 1999; but see Ward 2004). Others cite Justice Earl Warren as evidence that political philosophy, rather than party identification per se, affects the timing of some resignations; Warren was appointed by Republican President Dwight D. Eisenhower but reportedly tried unsuccessfully to time his resignation so that a Democrat could nominate his successor (Oliver 1986:805–806, citing White 1982:306–308; Schwartz 1983:680–83, 720–25). Second, most of these narrative accounts relied on justices’ recollections of thoughts and emotions, explanations of their past behavior, and even predictions of their future behavior. The validity of such reports is dubious (Cannell, Miller, and Oksenberg 1981; Eisenhower, Mathiowetz, and Morganstein 1991; Fazio 1986; Fishbein and Ajzen 1975; Kalton and Schuman 1982; Sudman and Bradburn 1982). Third, and perhaps most important, existing historical narrative studies focused disproportionately or exclusively on justices who are believed to have acted as predicted by the politicized departure hypothesis. Selective historical studies provide nuanced understanding of specific cases, and they are a useful basis for formulating hypotheses, but highly selected samples are ill-suited to hypothesis testing (Winship and Mare 1992).

Unlike narrative historical research, extant statistical studies considered hypotheses that observable political circumstances have, on average, affected the timing of all departures from the Court. Statistical analyses of Supreme Court departures varied widely in substantive conclusions and methodology (see below). For example, Brenner (1999), Squire (1988), and Yoon (2006) found no evidence of a pattern of politicized departure of justices, but Hagle (1993) and King (1987) found political effects on annual numbers of departures from the Supreme Court, and Box-Steffensmeier and Zorn (1998) and Zorn and Van Winkle (2000) reported some analyses that are consistent and some that are not consistent with the politicized departure hypothesis. In related analyses, Barrow, Gryski, and Zuk (1996), Barrow and Zuk (1990), Nixon and Haskin (2000), Spriggs and Wahlbeck (1995), and others examined departures from federal district and appellate courts. In short, there is much research on the politicized departure hypothesis, and it is inconclusive.

METHODS

We describe key methodological issues, focusing first on matters that have sparked debate in previous Supreme Court departure studies.

Lumping

King (1987) and Yoon (2006) lumped retirements and deaths in office into un differentiated departures from the Court.5 Hagle (1993), Nixon and Haskin (2000:462), and Spriggs and Wahlbeck (1995:575) complained that lumping confuses interpretation. Further, we observe that lumping retirements and deaths in office conflates opposite behaviors: retirement occurs when a live justice resigns from the court, but death in office can occur only if a justice does not resign. (Suicide appears to be unprecedented among Supreme Court justices.) In statistics, lumping is well known as sometimes disastrous, sometimes benign, and best avoided (Cotterman and Peracchi 1992; Ledoux, Rubino, and Sericola 1994). So we distinguish retirements from deaths in office.

Aggregation

Some studies aggregate retirements and deaths in office of individual justices into annual frequencies of these events for the entire Court (Callen and Leidecker 1971; Hagle 1993; King 1987; Ulmer 1982; Wallis 1936). Using annual frequencies to test hypotheses about individual behavior exemplifies the “ecological fallacy” (see King 1997; Robinson 1950). Therefore, we examine individual-level data.

Vitality and Health Measurement

It is a commonplace of retirement studies that as workers’ health (i.e., vitality) declines, their probability of retirement increases (Bound 1991; Dwyer and Mitchell 1999; French 2005; Parsons 1982). Virtually all previous historical narrative studies of Supreme Court departures considered the retirement effects of vitality or its sensational opposite, “ decrepitude” (Garrow 2000). In quantitative analyses, Squire (1988) included a measure of justices’ poor health, but Hagle (1993:35) and Zorn and Van Winkle (2000:162) criticized Squire’s measure. Citing Greenhouse (1984), Hagle (1993:46) asserted that Supreme Court justices fib flagrantly about their health. Zorn and Van Winkle (2000) used justices’ written opinion production to measure health, but productivity obviously differs from health and is plausibly subject to a wide range of additional causes, including (but not limited to) psychological factors, the productivity of other justices, and Court group dynamics (see Green and Baker 1991). No subsequent quantitative analysis of Supreme Court departures (e.g., Yoon 2006) appears to have included a vitality measure.

Ironically, a standard health measure exists for all deceased Supreme Court justices but has not been used previously. This measure is the justice’s future longevity—the number of remaining years of life, measured in each year while still alive. Future longevity is widely used in health and retirement research (e.g., Baker, Stabile, and Deri 2004; Bound 1991; French 2005; Idler and Kasl 1991; Kaplan 1987; Mossey and Shapiro 1982; Parsons 1982). Further, future longevity is used as a health indicator for establishing the criterion validity of self-reported, subjective health measures (Davies and Ware 1981; Mossey and Shapiro 1982; Ross and Wu 1995). Han et al. (2005:216) found significant association between change in mortality and change in subjective feelings of vitality, thereby providing evidence that future longevity can serve as an indicator of subjective as well as objective health. As we write in April 2008, all former justices except Justice O’Connor are dead, permitting calculation of years of remaining life for all but one former justice, in every year of their service on the Court.

Time and Units of Analysis

Justices customarily resign at the end of the Court’s annual term, the Court organizes its activities into annual sessions, presidents are elected to four-year terms, and Court pension eligibility rules are based on completed years of service and whole years of age. Consequently, dates and times for Supreme Court careers tend to be rounded to whole years, multiple resignations in the same year tend to occur simultaneously, and relevant time-varying political circumstances tend to exist for whole years, rather than for shorter intervals. Date rounding, co-occurrence of events, and time-varying independent variables are easily accommodated by discrete-time event-history methods (Yamaguchi 1991), but not as easily by continuous time methods. So we use discrete-time methods here. In our models, the unit of analysis is the justice-year; variable values for each observation indicate the retirement, mortality, and other characteristics and behaviors of one particular incumbent justice in one specific calendar year. Our statistical analyses estimate the effects, in each year, of independent variables on probabilities that each incumbent justice retires, dies in office or remains in office at the end of that year. Probabilities are unobservable, so we estimate them statistically from observations of whether each justice retires, dies in office, or does neither, in each year in which the justice serves at least some time on the Court. We test hypotheses with statistical estimates of independent variable effects on these probabilities.

Discrete-Time Probability Models

Although 44.5% of all justices have died in office and 47.3% have retired from office, death in office occurs in 2.6% of justice-years, and retirement occurs in 2.8% of justice-years. These proportions of justice-years are small enough to require nonlinear probability models to avoid possible nonsensical predictions of negative probabilities of retirement and death in office for some justice-years. Therefore, most of our analyses use logistic regression (logit) analysis, which constrains probability estimates to the interval (0,1). We also use multinomial probit (MNP) analysis to permit comparisons with previous MNP analyses. Our analyses are estimated over a complete enumeration of each and every year served on the Supreme Court by each and every justice appointed to the Court, from 1789 through 2006.

Nonlinear Time Effects

Age, job tenure (years on the Court), and calendar year are known to sometimes show nonlinear effects on mortality and retirement hazards. These nonlinearities are variously described as compression of morbidity; the uneven advance of historical change; decreasing (or increasing) marginal effects; or, in failure-time analysis, the U-shaped “bathtub” distribution. Because many mathematical functions virtually duplicate the same values over a fixed range, it is sufficient to use log-fractional polynomial transformations of these variables to permit but not require time variables to have nonlinear effects. Log-fractional polynomial transformations are a simple but rich generalization of common polynomial regression (Gilmour and Trinca 2005; Royston and Altman 1994). For skeptics, we also present analyses with only linear-time terms.

Right Censoring

Although probabilities of resignation and death in office are positively correlated (both increase over time), actual resignation and actual death are mutually exclusive. Thus, death in office right censors subsequent data on retirement, and retirement right censors later data on death in office (Allison 1995). Right censoring is easily accommodated in discrete-time survival and event-history analysis: we include in our analyses the justice-years of each and every justice for each and every year in which that justice served any time on the Supreme Court. This method makes full use of all available information on retirement and death in office, avoids bias, and produces consistent estimates of model parameters (Allison 1995).

Competing Risks

Zorn and Van Winkle (2000) treated retirement, death in office, and continued work as “competing risks” for justices. This treatment neglects the constitutionally mandated, voluntary nature of retirement from the Supreme Court. Justices can choose to retire if they have not already died in that year, but they can die in office only if they have not already retired. Thus, for Supreme Court justices, retirement and death in office are sequential risks, rather than the synchronous alternatives imagined by the competing risks formulation, and they are well accommodated by the allowances made for right censoring. (Further, and more substantively, when applied to the Supreme Court, the competing risks formulation gives dubious equivalent treatment to an involuntary biological event, death, and a voluntary rational social action, job resignation.) Nonetheless, for comparison and completeness only, we apply the competing risks model and report its results.

Correlated Errors

Stable, unobserved characteristics of justices (e.g., tastes for work, family circumstances) may affect their retirement and death probabilities. Thus, observations pertaining to a particular justice constitute a cluster of correlated observations. To accommodate clustering, we calculate robust standard errors and significance tests, adjusted for sample clustering (Wooldridge 2001:57).

Political Climate Measures

We test hypotheses with statistical estimates of independent variable effects on justices’ annual probabilities of retirement and death in office. For each justice in each year of service, effects of political climate variables are measured by (1) SameParty, a dummy indicator (0,1) of whether or not the incumbent U.S. president is of the same political party as the president who appointed the justice; (2) Year12, a dummy indicator (0,1) of whether or not the incumbent U.S. president is in the first two years of his term; and (3) the product of SameParty and Year12. In some models, the following alternative parameterization of political circumstances simplifies interpretation. With no loss of information, we define NoSameParty as (1 – SameParty), and Year34 as (1 – Year12), and we parameterize political circumstances with the variables SameParty × Year12, SameParty × Year34, and NoSameParty × Year12.6 Together, the three variables SameParty × Year12, SameParty × Year34, and NoSameParty × Year12 indicate all combinations of values of SameParty and Year12. Republicans, Whigs, and Federalists are coded as members of the same party. Democrats and Democratic Republicans also are treated as members of the same party.

DATA

We examine data on all justices of the U.S. Supreme Court from 1789 through 2006.7 Table 2 contains summary statistics. Variables are as follows.

Table 2.

Descriptive Statistics for Independent Variables in Event-History Analyses, for Justice-Years

| Variable Name and Brief Description | Statistic | All Justices | Died in Office | Retired or Still in Office |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n for All Variables Except Future Longevity | n | 1,895 | 866 | 1,029 |

| Year (calendar year) | Mean | 1903.8 | 1867.2 | 1934.7 |

| SD | 60.49 | 48.63 | 51.65 | |

| Min. | 1789 | 1789 | 1789 | |

| Max. | 2006 | 2005 | 2006 | |

| Age (justice’s age in years) | Mean | 62.81 | 60.92 | 64.40 |

| SD | 9.566 | 9.455 | 9.371 | |

| Min. | 33 | 33 | 41 | |

| Max. | 91 | 87 | 91 | |

| Tenure (justice’s years of service on the Supreme Court) | Mean | 10.83 | 11.02 | 10.68 |

| SD | 8.329 | 8.460 | 8.218 | |

| Min. | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Max. | 36 | 34 | 36 | |

| Pension Eligible (justice qualified for pension; dummy variable) | Mean | 0.2248 | 0.1074 | 0.3236 |

| SD | 0.4176 | 0.3098 | 0.4681 | |

| Future Longevity (years between current year and year of justice’s death; not applicable for current justices; available for all but one former justice) | n | 1,734 | 866 | 868 |

| Mean | 14.13 | 11.02 | 17.24 | |

| SD | 9.389 | 8.460 | 9.243 | |

| Min. | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Max. | 42 | 34 | 42 | |

| SameParty × Year12 (president and justice same party and presidential term year 1 or 2; dummy variable) | Mean | 0.3055 | 0.2910 | 0.3178 |

| SD | 0.4608 | 0.4545 | 0.4658 | |

| SameParty × Year34 (president and justice same party and presidential term year 3 or 4; dummy variable) | Mean | 0.3198 | 0.3187 | 0.3207 |

| SD | 0.4665 | 0.4662 | 0.4670 | |

| NoSameParty × Year12 (president and justice not same party and presidential term year 1 or 2; dummy variable) | Mean | 0.2016 | 0.2113 | 0.1934 |

| SD | 0.4013 | 0.4085 | 0.3951 | |

| NoSameParty × Year34 (president and justice not same party and presidential term year 3 or 4; dummy variable) | Mean | 0.1731 | 0.1790 | 0.1681 |

| SD | 0.3784 | 0.3836 | 0.3742 |

Retire (or retirement) is a dummy variable (0,1) equal to 0 for a justice-year unless the corresponding justice retired, resigned, or accepted “senior status” during that year or before starting service the next year.

Death in office is a dummy variable (0,1) equal to 0 for a justice-year unless the corresponding justice served on the Court that year but died without retiring before service the subsequent year.

Year1788 is the calendar year – 1788.8 ln(Year1788) is the natural logarithm of Year1788; the logarithmic transformation improves the fit of some models. We include the calendar year to hold constant trends in the probabilities of retirement and death in office.

Age is the age of the justice in years at the start of the justice-year. Probabilities of death and retirement increase with age. In some analyses, we add Age squared and Age cubed to the analysis, to fit nonlinear age effects.

Tenure is years of service on the Court. The annual probability of job quitting in the working population is known to first decline as tenure increases and then increase with additional tenure (Stolzenberg 1989). Tenure cubed and Tenure cubed × ln(Tenure) prove useful transformations of tenure.

Pension eligible is a dummy variable equal to 0 unless the justice is eligible for a federal judicial pension in the relevant year.

In each justice-year, Future longevity indicates remaining years of life. Future longevity for each justice-year is the difference between the calendar year of the justice-year and the calendar year in which the justice ultimately dies. Future longevity squared proves to be a useful transformation of future longevity.

RESULTS

Historical Trends

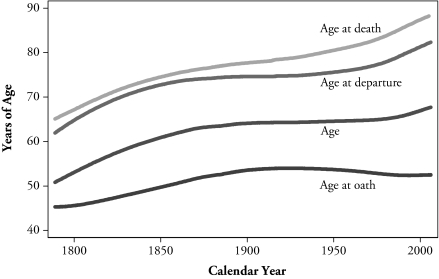

For incumbent justices, Figure 1 shows trends in mean age, mean age when swearing oath of office, mean age when eventually leaving the Court, and mean age at death. In each year, the gap between mean age at oath and mean age of justices indicates justices’ average tenure on the Court. At each year, the gap between mean age and mean age at retirement indicates the mean future years of Court service of justices serving in that year.

Figure 1.

Means of Sitting Justices’ Age at Oath, Age, Eventual Age at Departure From Court, and Eventual Age at Death (in order listed) Versus Calendar Year

Note: Lines are fitted and smoothed by Cleveland’s locally weighted regression (LOWESS) (Cleveland and Devlin 1988).

Retirement Analyses

Table 3 presents logit analyses of retirement. Analyses 1, 2, 4, and 5 parameterize the president’s political party and term year with SameParty × Year12, SameParty × Year34, and NoSameParty × Year12. Coefficients of these variables indicate effects of combinations of values of SameParty and Year12, relative to the condition that both SameParty and Year12 equal 0. Analysis 3 parameterizes presidential party and term year with dummy variables SameParty, Year12, and SameParty × Year12. To dispel doubts that nonlinear transformations of year and tenure artifactually increase political circumstances variable effects, Analysis 1 includes only linear forms of independent variables.9

Table 3.

Coefficients and Absolute Values of Z Statistics, From Logistic Regression Analyses of Annual Probability of Retirement (versus nonretirement) From U.S. Supreme Court, 1789–2006

| Independent Variable | Analysis Number |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | |

| Calendar Year | |||||

| Year1788 (calendar year – 1788) | –0.0064* (1.85) | ||||

| ln(Year1788) | –0.6887*** (3.25) | –0.6887*** (3.25) | –0.4951** (2.31) | –0.6110*** (2.68) | |

| Justice’s Years of Age | |||||

| Age | 0.0470* (1.89) | 0.0655*** (2.50) | 0.0655*** (2.50) | 0.0548* (1.76) | 0.0583** (2.15) |

| Justice’s Years of Supreme Court Tenure | |||||

| Tenure | –0.0260 (1.19) | ||||

| Tenure, cubed | –0.0012*** (3.16) | –0.0012*** (3.16) | –0.0013*** (3.5) | –0.0012*** (3.22) | |

| Tenure, cubed × ln(Tenure) (x 1,000) | 0.3347*** (3.23) | 0.3347*** (3.23) | 0.3754*** (3.54) | 0.3463*** (3.28) | |

| Justice’s Pension Eligibility Indicator | |||||

| Pension eligible | 2.0904*** (4.37) | 2.3423*** (5.06) | 2.3423*** (5.06) | 2.3722*** (4.92) | 2.4514*** (5.06) |

| Justice’s Remaining Years of Life | |||||

| Future longevity, squared | –0.0172*** (2.66) | ||||

| Future longevity, squared × ln(Future longevity) | 0.0048*** (2.72) | ||||

| Political Circumstances Indicators | |||||

| SameParty × Year12a | 0.9850** (2.09) | 0.9555** (2.08) | –0.3495 (0.56) | 0.9706** (2.07) | 0.9563** (2.06) |

| SameParty × Year34 | 0.5789 (1.16) | 0.5651 (1.18) | 0.6120 (1.24) | 0.5804 (1.2) | |

| NoSameParty × Year12 | 0.7087 (1.46) | 0.7399 (1.51) | 0.7419 (1.50) | 0.7423 (1.50) | |

| Year12a | 0.7399 (1.51) | ||||

| SamePartya | 0.5651 (1.18) | ||||

| Constant | –7.0901*** (4.28) | –5.8837*** (3.71) | –5.8837*** (3.71) | –5.3241*** (2.75) | –5.7000*** (3.56) |

| Estimation Details | |||||

| Number of justice-years | 1,895 | 1,895 | 1,895 | 1,734 | 1,734 |

| Number of justices (4) | 110 | 110 | 110 | 100 | 100 |

| Pseudo–log likelihood | –214.579 | –206.572 | –206.570 | –196.070 | –199.200 |

| Pseudo-R2 | 0.1254 | 0.1581 | 0.1581 | 0.1728 | 0.1596 |

Notes: Robust Z statistics, corrected for clustering, are in parentheses. The unit of analysis for results reported here is one Supreme Court justice in one year (one justice-year). See the text for a discussion of the equivalence of the analyses reported in columns 2 and 3. The number of justices is presented for interest only: 110 individuals who were appointed a total of 112 times to the Supreme Court.

In the analysis reported in column 3, the sum of coefficients for SameParty × Year12, Year12, and SameParty is 0.9555, with a standard error of 0.4602 and a z statistic of 2.08. Note the correspondence of that result to column 2 for SameParty × Year12, and the correspondence column 3 for Year12 and SameParty to column 2 for Year12 and SameParty × Year34, respectively.

p < .10;

p < .05;

p < .01;

p < .001

Retirement and political circumstances. In column 1, row 10 of Table 3, the coefficient of SameParty × Year12 is 0.9850 (significant, α ≤ .02, one-tailed). Thus, other things equal, retirement odds increase by 168% (= e0.9850 – 1) when the incumbent president is from the same political party as the president who nominated the justice and the presidential administration is in its first or second year (compared with the odds when the incumbent president is from a different political party and a presidential administration is in the third or fourth year of its four-year term).

To express the coefficient of SameParty × Year12 as a probability effect, suppose a hypothetical justice had a retirement probability of 1%, the incumbent president was of a party different from the party of the president who nominated the justice, and the president was in the second half of his four-year term (i.e., SameParty = 0 and Year12 = 0). Changing both SameParty and Year12 to 1 would increase the expected retirement probability by a multiple of more than 2.6, from 1% to 2.6%. If, in this same example, the justice’s initial retirement probability were 10%, then the expected probability after the change of presidents would increase by a multiple of about 2.3, to 22.9%.

In Analysis 2 of Table 3, we add log fractional polynomial transformations of calendar year and tenure. (We find no curvilinear effects of age, net of calendar year, and tenure.) We replace Year1788 with ln(Year1788) and we replace Tenure with Tenure cubed and the product of Tenure cubed and ln(Tenure), raising the pseudo-R2 from .1254 to .1581. But effects of political circumstance variables are virtually the same in Analyses 1 and 2.

Analysis 3 reparameterizes presidential party and term year, using SameParty, Year12, and SameParty × Year12. The effect of SameParty = 1 and Year12 = 1 is the sum of the coefficients for all three dummy variables, or 0.955, which is identical to the coefficient for SameParty × Year12 in Analysis 2. All other results for Analysis 3 are identical to those for Analysis 2.

Retirement and pension benefit eligibility. Coefficients of the pension benefit eligibility indicator range from 2.0904 in Analysis 1 to 2.4514 in Analysis 5. The smallest estimate indicates that, other things equal, pension benefit eligibility increases the retirement odds in a justice-year by a multiple of 8.09 (= e2.0904). In Models 2 and 3, which allow for nonlinearities in tenure and calendar year, the eligibility for pension benefits increases retirement hazard by a multiple of 10.4 (= e2.34232). In Model 4, the increase is a factor of 10.7 (= e2.37218). Expressed as a probability, if a justice without pension benefit eligibility had a retirement probability of 1%, then the addition of pension benefits would increase the expected probability to 7.6% according to Model 1, 9.5% in Models 2 and 3, and 9.8% in Model 4. If that justice had a 5% probability of retirement before receiving benefits, adding pension benefits eligibility would increase the probability to 29.9% in Model 1, 35.4% in Models 2 and 3, and 36.1% in Model 4. Effects this large are remarkable in the social sciences.

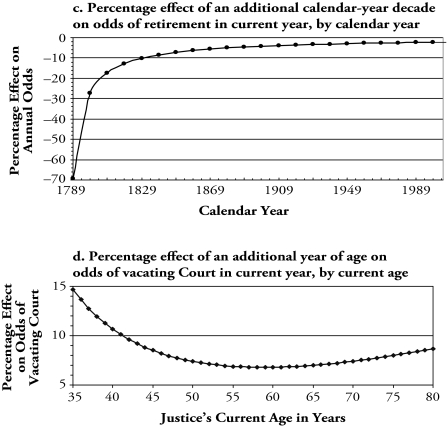

Retirement and tenure. To interpret coefficients of Tenure cubed and Tenure cubed × ln(Tenure), we use them to calculate the effect of an additional year of Supreme Court tenure on expected retirement odds. These effects are stated as proportional changes in odds, calculated from Analysis 4 and graphed in Figure 2, panel a. This panel shows that for those with one year of service on the Supreme Court, the effect of an additional year of tenure on odds of retiring is negative but nearly zero. The effect of an additional year of tenure becomes increasingly negative through the 15th year on the Court, when an additional year of tenure decreases expected retirement odds by 12.5%. Thereafter, the negative effect of an added year of tenure weakens annually, until it becomes positive at 25 years. At 28 years of tenure, an additional year increases expected retirement odds by 11.2%. At 29 years, the increase is 15.8%.

Figure 2.

Curvilinear Effects of Time Variables

Retirement and age. In Analysis 4 of Table 3, the coefficient of Age is 0.0548 (significant, α ≤ .05, one-tailed). Thus, an additional year of age is associated with a 5.5% increase in expected retirement odds. In Analyses 2 and 3, which do not hold constant Future longevity, expected odds increase a rate of about 6.5% per additional year of age.

Retirement and future longevity. Analysis 4 of Table 3 adds Future longevity squared and Future longevity squared × ln(Future longevity). Each future longevity term is statistically significant (each α ≤ .01, two-tailed); both terms are jointly significant (χ2(2 df) = 7.88, α ≤ .02, two-tailed). The coefficient of SameParty × Year12 in Analysis 4 is 0.9706, which trivially higher than in Analysis 2, trivially lower than the estimate in Analysis 1, and not significantly different from either at any meaningful α level. Thus, controlling for Future longevity does not substantially modify the estimated effect of SameParty × Year12 on the probability of retirement.

Because future longevity is unknown for justices who still live as we write, Analysis 4 excludes 161 justice-years pertaining to nine living justices and one living former justice. To consider the hypothesis that results in Analysis 4 are substantially affected by loss of these 161 justice-years, we reestimate as Analysis 5 the same model that we estimated as Analysis 2, after excluding the same 161 justice-years excluded from Analysis 4. Analysis 5 coefficients lead to the same conclusions as Analysis 2; coefficients and z statistics of political circumstances indicators are virtually identical in both analyses.

As time passes, future longevity diminishes. To interpret effects of these reductions in future longevity in Analysis 4, we calculate proportional effects of a one-year decrease in Future longevity on expected retirement odds. Panel b of Figure 2 shows that for justices with 22 or fewer years of remaining life, expected retirement odds increase as time left to live diminishes. At nine years left to live, the retirement effects of diminishing life reach their maximum of about 8% per year.

Retirement and calendar year. Analysis 4 reports a coefficient of −0.4951 for ln(Year1788). Thus, expected annual retirement odds of Supreme Court justices change at an elasticity of about one-half percentage point decrease in retirement odds per percentage point increase in the number of calendar years since 1788. Panel c of Figure 2 depicts the impact of 10-year increases in the calendar year. An additional decade would lower expected annual retirement odds by 69.5% in 1789, 5.0% in 1879, and 2.2% in 2005.

Death-in-Office Analyses

Because death in office occurs when a justice both chooses not to retire and dies, we expect negative effects on the probability of death in office from independent variables that promote retirement, and positive effects from those that mark increased mortality risk. If an independent variable increases the probabilities of both retirement and mortality, then its negative effects (via retirement) and its positive effects (via mortality) would offset each other to some degree, depending on the strength of each effect and the association between the probabilities of retirement and mortality.

Table 4 presents two logit analyses of the hazard of death in office, analogous to retirement analyses in Table 3, with two differences. First, we find no nonlinear transformations of time variables that improve their fit to the hazard of death in office. Second, Future longevity is unavailable as a control variable in analyses of Death in office because death occurs in the current year if and only if Future longevity is 0. Consequently, models of death in office are computationally intractable when Future longevity is an independent variable.

Table 4.

Coefficients and Absolute Values of Z Statistics, From Logistic Regression Analyses of Annual Probability of Death While Serving on the U.S. Supreme Court (versus continued service or retirement), 1789–2006

| Independent Variable | Analysis Number |

|

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | |

| Calendar Year | ||

| Year1788 (calendar year – 1788) | –0.0117*** (3.29) | –0.0117*** (3.29) |

| Justice’s Years of Age | ||

| Age | 0.0646*** (3.18) | 0.0646*** (3.18) |

| Justice’s Years of Supreme Court Tenure | ||

| Tenure | 0.0306 (1.44) | 0.0306 (1.44) |

| Justice’s Pension Eligibility Indicator | ||

| Pension eligible | 0.0948 (0.21) | 0.0948 (0.21) |

| Political Circumstances Indicators | ||

| SameParty × Year12 | –0.4229 (1.03) | 0.6797 (1.43) |

| SameParty × Year34 | –1.1026** (2.30) | |

| NoSameParty × Year12 | –0.0202 (0.05) | 1.0824*** (2.35) |

| NoSameParty × Year34 | 1.1025** (2.30) | |

| Constant | –6.725*** (5.47) | –7.828*** (6.17) |

| Estimation Details | ||

| Number of justice-years | 1,895 | 1,895 |

| Number of justices (3) | 110 | 110 |

| Pseudo–log likelihood | –202.477 | –202.477 |

| Pseudo-R2 | 0.1098 | 0.1098 |

Notes: Robust Z statistics, corrected for clustering, are in parentheses. The unit of analysis for results reported here is one Supreme Court justice in one year (one justice-year). The number of justices is presented for interest only: 110 individuals who were appointed a total of 112 times to the Supreme Court.

Political circumstances and death in office. In Table 4, Analysis 1 follows the parameterization of political circumstances used in most of the Table 3 retirement analyses. The coefficient of SameParty × Year34 is −1.1026 (significant, z = 2.30, α < .025, one-tailed). Thus, a change in value of SameParty × Year34 from 0 to 1 is associated with a reduction by about two-thirds (2/3 ≈ 1 – e–1.1026) of the odds of dying in office (compared with the odds if NoSameParty × Year34 = 1). Other results are less clear in this parameterization: the coefficient of SameParty × Year12 is not significantly different from zero (z = 1.03), but it is also not significantly different from the coefficient of SameParty × Year34 (α ≤ .05, two-tailed).10

Analysis 2 clarifies political circumstances effects by reparameterizing. In Analysis 2, the reference category is changed to SameParty × Year34 = 1.11 In Analysis 2, the death-in-office odds are about three times higher when the incumbent president is not of the same party as the president who appointed the justice (compared with when the incumbent president is of the same party),12 but there is no statistically significant effect of presidential term year on death in office. Stated as probability effects, if a hypothetical justice had a 1% probability of dying in office in a given year, then a change of NoSameParty × Year12 from 0 to 1 would increase that expected probability to 2.9%. If the hypothetical justice had a 10% probability of dying in office, then a change of NoSameParty × Year12 from 0 to 1 would increase that expected probability to 24.7%. Effects would be nearly identical for changes in NoSameParty × Year34.

Time, pension eligibility, and death in office. Death-in-office odds decline at a rate of 1.17% per calendar year, on average, other things being equal. Over a decade’s time, annual reductions cumulate to an 11% reduction in death-in-office odds. In contrast to retirement results, nonlinear transformations of Year1788 do not improve its fit to death-in-office data. Thus, secular decline in these odds continues unabated. Each additional year of Age increases expected death-in-office odds by about 6.5% (the coefficient is 0.0646; significant, α < .001, one-tailed test), on average and other things being equal. However, effects of Tenure and Pension eligible are not significant (α < .05, one-tailed test).

Retirement and death in office. Above, we argue that hazards of Death in office and Retirement are positively correlated, but they and the processes that produce them are dissimilar. Our empirical findings are consistent with those arguments in several ways. First, we find that the effects of political circumstances, Pension eligible, Tenure, and Year 1788 on retirement hazard are substantially different from effects of those variables on hazard of death in office.13 These differences indicate dissimilarity between the etiology of retirement and death in office.

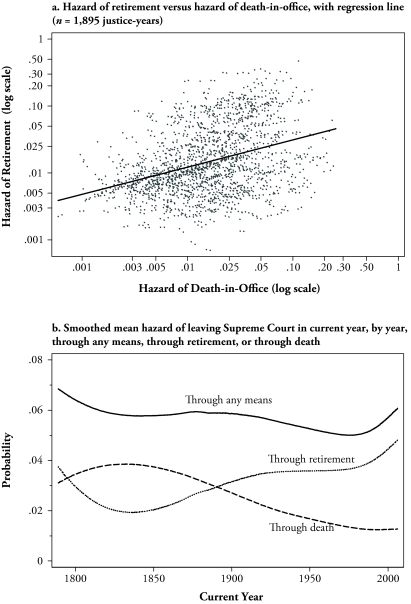

Second, our analyses indicate that the hazard of retirement is empirically distinct from the hazard of death in office. For each justice-year, we use Analyses 3 and 4 from Table 3 to calculate the estimated the hazard of retirement,14 and we use Analysis 1 from Table 4 to calculate the estimated the hazard of Death in office. Panel a of Figure 3 plots the logarithms of these hazards against each other and shows the regression of ln(retirement hazard) on ln(death-in-office hazard): ln(retirement hazard) = 2.7441 + 0.3405 ln(death-in-office hazard) (R2 = .14). The standardized coefficient of ln(death-in-office hazard) is 0.37 (statistically significant, α < .001, robust t = 7.70, corrected for clustering, two-tailed). For comparison, in status attainment models, the standardized effect of father’s occupational socioeconomic status (SEI) on son’s occupational SEI is about 0.3, and the standardized effect of son’s schooling on his occupational SEI is about 0.4 (Blau and Duncan 1967). Thus, the hazards of retirement and death in office are substantially related, as expected, but they are no more related than father’s and son’s SEI, or son’s education and son’s SEI.

Figure 3.

Estimated Hazards of Court Departure Through Death and Retirement

Third, historical trends in the distribution of retirement hazard differ from trends in the distribution of death-in-office hazard.15 Panel b of Figure 3 shows the time trend in the means of these hazards for incumbent justices, smoothed by Cleveland’s (Cleveland and Devlin 1988) method of locally weighted regression (LOWESS). Mean hazards of retirement and death in office tend to move in opposite directions. Standard deviations of these distributions also move in opposite directions. In brief, trends in the distributions of retirement and death-in-office hazards seem well differentiated.

Analyses of Departure by Any Means

Notwithstanding our stated objections to lumping retirement with death in office, we seek to compare our analyses of retirement and Death in office to analyses of departure by any means. Analyses in Table 5 examine the determinants of Departure by any means with methods, procedures, data, and independent variables that are comparable to those applied in our analyses of Retire and Death in office. As in Table 4 analyses, Future longevity is not included, as it is confounded with death in office, a component of Departure by any means.

Table 5.

Coefficients and Absolute Values of Z Statistics, From Logistic Regression Analyses of Annual Probability of Vacating the U.S. Supreme Court by Death or Retirement (versus not vacating), 1789–2006

| Independent Variable | Analysis Number |

|

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | |

| Calendar Year | ||

| Year1788 (calendar year – 1788) / 100 | –1.020*** (4.09) | –1.020*** (4.09) |

| Justice’s Years of Age | ||

| 1 / (Age, squared) | –2,749 (1.11) | –2,749 (1.11) |

| Age, cubed / 1,000,000 | 3.738** (2.00) | 3.738** (2.00) |

| Justice’s Years of Tenure to Date on Supreme Court | ||

| Tenure | –0.1164** (2.60) | –0.1164*** (2.60) |

| Tenure, squared / 1,000 | 3.505*** (2.99) | 3.505*** (2.99) |

| Justice’s Pension Eligibility Indicator | ||

| Pension eligible | 1.197*** (3.60) | 1.197*** (3.60) |

| Political Circumstances Indicators | ||

| SameParty × Year12 | –0.165 (0.60) | |

| SameParty × Year34 | –0.2906 (–0.67) | –0.714*** (2.44) |

| NoSameParty × Year34 | –0.259 (0.82) | |

| SameParty | –0.1649 (–0.60) | |

| Year34 | –0.259 (–0.82) | |

| Constant | –1.935 (1.58) | –1.6759 (–1.39) |

| Estimation Details | ||

| Number of justice-years | 1,895 | 1,895 |

| Number of justices | 110 | 110 |

| Pseudo–log likelihood | –354.311 | –354.311 |

| Pseudo-R2 | 0.1145 | 0.1145 |

Notes: Robust Z statistics, corrected for clustering, are in parentheses. The unit of analysis for results reported here is one Supreme Court justice in one year (one justice-year). In Analysis 1, the sum of coefficients for SameParty, Year34, and SameParty × Year34 is −0.714 with a Z statistic of 2.44. This sum (and Z statistic) is identical to the coefficient for SameParty × Year34 in Analysis 2. The condition that would make the values of SameParty, Year34, and SameParty × Year34 all equal to 1 are exactly the conditions that would make the value of SameParty × Year34 equal to 1.

Political circumstances and departure. If the incumbent president is of the same party as the president who appointed a justice, then the politicized departure hypothesis predicts both increased probability of departure by retirement in presidential term years 1 and 2, and consequent decreased probability of departure by death in office in term years 3 and 4.

In Analysis 1, coefficients for SameParty, Year34, and SameParty × Year34 are all negative, but none is by itself statistically significant. However, if the political party of the current U.S. president were the same as the political party of the president who appointed the justice, and if the current president were in his third or fourth year of a presidential term, then each of these dummy variables would equal 1, and their combined effect would be the sum of their coefficients, −0.7142, which is statistically significant (Z = 2.44, α ≤ .01, one-tailed) and indicates a 51% reduction in annual odds of vacating office. Although parameterized differently, Analysis 2 yields identical but more directly visible results: the coefficient for SameParty × Year34 is −0.7142 (Z = 2.44). In Analysis 2, the coefficient for SameParty × Year12 is −0.165, but a 95% confidence band around this estimate includes larger negative values, zero, and positive values. In sum, both parameterizations of political circumstances show results consistent with part of the politicized departure hypothesis, not inconsistent with the rest of it, and reflective of the ambiguity that comes from lumping retirement and death in office.

Table 5 shows effects of three time-related variables: First, the coefficient of Year1788 is −0.01020, indicating that odds of vacating decline by about 1% with each additional calendar year. Second, Tenure shows nonlinear effects. For justices with one year of Tenure on the Supreme Court, an additional year of Tenure reduces by 10.0% the odds of Departure by any means. Thereafter, the effect of additional Tenure grows less negative. After 17 years, the effect of additional Tenure becomes positive, and after 35 years, an additional year of Tenure increases odds of Departure by any means by 14.2%. Third, effects of a justice’s Age are nonlinear and fitted with 1/Age squared and Age cubed. Panel d of Figure 2 shows that the effect of an additional year of Age on odds of Departure by any means is highest at the youngest ages (14.7% at age 35), declines to its minimum of 6.8% at age 59, and rises thereafter to 8.7% at age 80.

Competing Risks Analyses

Having stated above some limitations of the competing risks approach to Court departures, we apply it nonetheless to permit comparison to our own results in Tables 3 and 4. We follow Box-Steffensmeier and Jones’s (1997:1450) preference for the MNP rather than MNL. Table 6 presents results of a multinomial probit analysis of the probability that in a given year a justice dies in office, remains in office, or retires from the Supreme Court. Again, the unit of analysis is the justice-year. The multinomial probit yields two equations: one estimating the probit of the hazard of Death in office, the other estimating the probit of the hazard of Retire. The omitted reference category is Continuation in office. MNP requires the same independent variables in equations for all outcomes, so we must omit Future longevity to avoid tautological prediction of death in office. We also add nonlinear transformations of control variables.

Table 6.

Coefficients and Absolute Values of Z Statistics, From Multinomial Probit Analysis of Death in Office Versus Retirement From Office Versus Remaining in Office by U.S. Supreme Court Justices, 1789–2006

| Independent Variable | Outcome |

|

|---|---|---|

| Death in Office | Retirement | |

| Calendar Year | ||

| Year1788 (calendar year – 1788) | –0.0083*** (4.03) | –0.0051*** (2.47) |

| Justice’s Years of Age | ||

| Age | 0.0478*** (3.51) | 0.0349** (2.22) |

| Justice’s Years of Tenure to Date on Supreme Court | ||

| Tenure | 0.0877* (1.73) | –0.0176 (0.33) |

| Tenure, cubed / 100 | –0.12892 (2.61) | –0.0751 (1.50) |

| Tenure, cubed x ln(Tenure) / 1,000 | 0.3546 (2.7) | 0.2189 (1.67) |

| Justice’s Pension Eligibility Indicator | ||

| Pension eligible | 0.2588 (0.92) | 1.487*** (4.87) |

| Political Circumstances Indicators | ||

| SameParty × Year12 | –0.1606 (0.62) | 0.5383* (1.90) |

| SameParty × Year34 | –0.6053** (2.14) | 0.2545 (0.86) |

| NoSameParty × Year12 | 0.0659 (0.26) | 0.4642 (1.55) |

| Constant | –5.167*** (6.44) | –4.811*** (5.02) |

| Estimation Details | ||

| Number of justice-years | 1,895 | |

| Number of justices | 110 | |

| Pseudo–log likelihood | –405.472 | |

Notes: Robust Z statistics, corrected for clustering, are in parentheses. The unit of analysis for results reported here is one Supreme Court justice in one year (one justice-year). Pseudo-R2 statistics are not available.

Results of the competing risks model (Table 6) are similar to the single-equation results reported in Tables 3 and 4. Table 6 shows a positive, statistically significant probit coefficient of 0.5383 (significant, α ≤ .03, one-tailed) for SameParty × Year12. To compare this probit coefficient with the logit coefficient for the same variable in Table 3, we evaluate both as probability effects: suppose a hypothetical justice had a 5% probability of retirement, and the president was in the last two years of his term (Year12 = 0) and of a different party than the president who appointed the justice (SameParty = 0). If Year12 and SameParty were both changed to 1, then the expected retirement probability would rise from 5% to 13.4%. In the logit analysis of Retire in Column 2 of Table 3, the same hypothetical scenario indicates a probability increase to 12.0%. Thus, the two retirement analyses estimate political climate effects that are both statistically significant, of identical direction, and similar magnitude.

MNP analyses of Death in office yield much the same conclusion: in Table 6, the probit coefficient of SameParty × Year34 is –.6053 (significant, α ≤ .03, one-tailed). If a hypothetical justice has a 5% probability of Death in office in the current year, and SameParty = 0 and Year34 = 0, then changing SameParty to 1 and Year34 to 1 would reduce the expected probability of Death in office from 5% to 1.22%. In Analysis 1 of Table 4, the same hypothetical scenario would reduce the expected probability of dying in office to 1.72%. Again, despite our objections to the competing risks approach, it yields similar conclusions about political climate as separate censored logit analyses of retirement and death in office.

DISCUSSION

Supreme Court justices constitute an “elderly leadership group” (Preston 1977) that has escaped previous demographic analysis, even as it has gained demographic notice for its enormous power, distinctive age distribution, unusual retirement patterns, and high frequency of death in office. Political commentators and historical, legal, and political researchers have argued that justices cling to office with apparent disregard for their own antiquity, physical infirmity, employment immobility, and pension-based economic security (equal to their full salary). However, even if justices are unusually long-lived and long-worked, our analyses suggest that, on average, retirement decisions of Supreme Court justices are responsive to age, health, tenure, and pension benefits, all in a manner generally consistent with contemporary demographic, sociological, and economic views of rational retirement decision-making. In particular,

Pension eligibility raises the annual odds of retirement by an order of magnitude—a huge effect by social science and employment research standards.

Retirement hazard rises sharply as health (measured by years left to live) fades. Contrary to prior speculation and argument, inclusion of a generally accepted health measure does not substantially alter other findings.

Tenure effects on retirement follow the “bathtub distribution” typical of orderly failure time processes. Justices start their service with elevated risk that removes individuals unsuited for the position (called “manufacturing defects” in failure-time studies), followed by a long period of low retirement rates (“regular service”), after which failure rates rise sharply (“end of service life”). Other things being equal, the average service period for justices is about 25 years.

Age raises expected annual odds of retirement about 6% per additional year, other things being equal.

Although age, health, tenure, and pension-related findings are consistent with current conceptions of rational retirement decisions, we also find that political climate effects on retirement are consistent with the politicized departure hypothesis. If the incumbent president is of the same party as the president who nominated the justice to the Court, and if the incumbent president is in the first two years of a four-year presidential term, then the justice has odds of resignation that are about 2.6 times higher than when these two conditions are not met.

In addition, political climate effects on death in office are consistent with the politicized departure hypothesis. When the incumbent president is of a different party than the president who appointed the justice, then the justice’s death-in-office odds are about tripled, compared with when the appointing president and the incumbent president are members of the same party.

Previous Supreme Court retirement analyses are methodologically disputatious. We reconsider a broad range of disputes. Conceptually, we conclude that multinomial (competing-risks) methods are inappropriate for testing politicized departure, as is lumping retirements and deaths in office into departures by any means. Empirically, we find that hazards of retirement and death in office are empirically distinct and therefore inappropriate for lumping together. Nonetheless, we perform multinomial and lumped analyses for comparison purposes, and results are consistent with our findings based on more defensible methods.

Although departure from the Supreme Court is important in its own right, our analyses shed light on three aspects of more general retirement processes. First, unlike nearly every other source of data on retirement, Supreme Court data permit us to distinguish between job departure by willful resignation and job departure by firing or induced retirement. Justices cannot be fired, nor can they receive financial inducements or pressure to leave office because their retirement benefits and pay are fixed by law, working conditions are not subject to employer manipulation, and strong ethical rules prevent their receipt of gifts or payments in exchange for departure from the Court. Thus, there is no chance that our analyses reify as workers’ own retirement decisions their employers’ decisions to fire them or induce them to quit. In these unusually unambiguous data, our findings are consistent with the general predictions of contemporary social science thinking about the effects of age, tenure, health, and personal finances on retirement decisions.

Second, our analyses suggest the relevance of employer organizational environment conditions to individual retirement behavior, even when those conditions do not affect the pay, pension, benefits, and working conditions of workers. Because the Supreme Court is a political institution whose members are appointed by the president, the president’s political party affiliation is an important part of the organizational environment of the Court. Thus, the politicized departure hypothesis is an assertion that organizational conditions influence the individual retirement decisions of employees, even as those decisions are the constitutionally protected, sole domain of the individual employee. As Sørensen and Sørenson (2007) recently demonstrated in a different context, organization environments can indeed affect individuals’ employment outcomes and have been observed to do so since the heyday of the so-called New Structuralism in employment research (Bibb and Form 1977; Hodson and Kaufman 1982; Stolzenberg 1975). Our findings are, we think, the first unambiguous demonstration of those effects on retirement decisions. We think there is considerable promise in further consideration of employer environment effects on retirement and voluntary job termination.

Third, our analyses suggest an expanded conception of rationality in retirement decisions. In contemporary economics, behavior is considered economically rational if it is intended to produce instrumental benefit for the actor (Vriend 1996:264). Retirement effects of age, health, tenure, and pension eligibility are usually understood to be instrumentally (i.e., economically) rational responses to the exigencies of time and treasure (Hayward et al. 1989; Lumsdaine 1995; Moen et al. 2001). However, we know of no assertion anywhere that politicized departure offers any instrumental benefit to justices. Indeed, politicized departure is a tendency toward continued service by justices who otherwise would tend to resign from the Court, or accelerated departure by justices who otherwise would tend to remain on the Court. The rational basis for politicized departure appears to be service to a value, perhaps the norm of reciprocity (Blau 1986; O’Hara 1993). In short, politicized departure is an example of Weberian value rationality, rather than instrumental rationality. We suspect that value rationality may be commonplace. For example, Mace’s (1986) consideration of corporate boards of directors describes behavior much like that predicted by the politicized departure hypothesis. We think there is considerable promise in further consideration of value rationality effects on retirement and voluntary job termination.

Acknowledgments

We thank Albert Yoon for making available to us some of the data analyzed herein. We thank Gary Becker, Aimee Dechter, Lee Epstein, Michel Guillot, Ryon Lancaster, William Landes, John A. Logan, and Richard Posner for helpful advice. We retain responsibility for any remaining errors or omissions.

APPENDIX. EFFECT MEASURES FOR LOGISTIC REGRESSION

Effects of variables follow from the logistic regression model. For brevity, we state that model for retirement only. Let Yij equal 1 if the ith justice retires in the jth year, and let Yij = 0 if he or she does not retire in that year. Let Pij equal the probability that Yij = 1. Let Oij = Pij / (1 – Pij) be the odds that Yij equals 1. Let Xij be a vector of independent variables, Xij = (xij1, xij2, …, xijK), measuring hypothesized causes and control variables for the ith justice in the jth year. ɛij is the error. ^ indicates an estimate. The logistic regression model is:

| (A1) |

Exponentiating Eq. (A1) transforms the left side from the logit to the odds, ôij, which has greater intuitive appeal:

| (A2) |

For more intuitive appeal, we solve (A2) for the probability, as follows:

| (A3) |

The effect of Xk on p̂ij, is the difference in the probability that Y = 1 that is associated with some convenient difference in Xk, on average and other things being equal. If convenient differences in Xk are minutely small, and the effect is expressed as a rate of change in probability per unit change Xk, then the effect measure is the partial derivative of the probability with respect to Xk ∂ p̂ij / ∂Xk. These partial derivatives (or marginal effects) obtain as follows: differentiating (A3) with respect to Xk indicates that the marginal effect of any particular Xk on the odds is a constant proportion of the odds:

| (A4) |

And dividing both sides of (5) by ôij yields:

| (A5) |

Differentiating (A4) yields the marginal effect of any particular x.k on the probability that Yij = 1:

| (A6) |

If a “convenient difference” in Xk is not minutely small, then it is necessary to calculate the change in Pij associated with that difference in Xk.

Footnotes

See also Preston’s (1977:171) call for demographic analysis of labor force exit by death by Supreme Court justices and other “elderly leadership groups.”

Although justices can be removed from office for treason, bribery, or other serious crimes, none have been so removed.

Modern economic writing often embraces value rationality as well as instrumental rationality.

Political party identification is a meaningful but crude dimension of political orientation. Obviously, justices and political parties may change their political orientations over time. Further, political views vary among supporters of the same political party. Nonetheless, political party identification as described here is a meaningful indicator of political orientation to researchers who have investigated the politicized departure hypothesis, beginning at least with Fairman (1938) and continuing as recently as Yoon (2006).

A discussant objected to the apparent novelty of the term lumpability. In fact, the term has been in regular use in probability and statistics for half a century, appearing in Kemeny and Snell’s (1960) well-known textbook and continuing through to the present (Cobb and Chen 2003).

We started with database kindly supplied by Albert Yoon, based on information he obtained from the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts, Federal Judicial Center. We checked some of those data against various sources including the Congressional Record, corrected errors, and added more data obtained in 2006 from the Federal Judicial Center (n.d.) and the U.S. Supreme Court (2006) for the 1789–1868 and the 2003–2006 periods.

Subtracting 1788 from calendar year preserves all information and avoids rounding problems that occurred in initial analyses with STATA version 8 that used calendar year.

A reader suggested that we “treat the event of retirement as the primary event of interest, which [is] censored by death in office, and to model selection on death-in-office.” In preliminary analyses, we did as suggested, but the results required rejection of that approach. That is, we estimated a maximum likelihood endogenous switching probit model (with robust standard errors corrected for clustering), in which retirement is observable only if death, a stochastic event, does not occur; this analysis failed to reject the null hypothesis that the selection and retirement equation errors are independent ( , not significant, α ≤ .05). That result notwithstanding, the endogenous switching probit model finds coefficient point estimates that are consistent with the politicized departure hypothesis but not statistically significant (α ≤ .05, one- or two-tailed test). The lack of significance is consistent with previous findings concerning the inefficiency of the selection correction estimator (Stolzenberg and Relles 1990, 1997).

Because we examine data on the entire universe of Supreme Court justices, it is at least arguable that significance tests can be ignored in these analyses. If coefficients are interpreted without significance tests, then Analysis 1 leads to the following conclusion: other things equal, the coefficient of −0.4229 for SameParty × Year12 indicates that death-in-office odds for a justice in a year are reduced by about one-third (0.34 = 1 – e0.4229) if the incumbent president is of the same party as the president who first nominated the justice to the Court, and the incumbent president is in the first two years of his term. The coefficient of −1.1026 for SameParty × Year34 indicates that if the incumbent president is instead in the third or fourth year of his term, then this reduction in death-in-office odds doubles. But, by itself, the number of years left in the incumbent president’s term has virtually no effect on the probability of death in office.

The coefficient of NoSameParty × Year12 is 1.0824 (significant, α < .01, one-tailed). The coefficient for NoSameParty × Year34 is 1.1025, significant (α < .015, one-tailed), almost identical to the coefficient of NoSameParty × Year12, and not significantly different from it (at any meaningful significance level, χ2 < .01, 1 df). We must reject the null hypothesis that both of these coefficients are 0 (χ2 = 6.57, 2 df, α ≤ .05, two-tailed).

Change in value of either NoSameParty × Year12 or NoSameParty × Year34 from 0 to 1 approximately triples the odds of dying in office (3 ≈ 2.95 = e1.0824; 3 ≈ 3.01 = e1.1025), other things being equal.

First, SameParty reduces the hazard of Death in office but increases the hazard of retirement. SameParty shows interaction effects with the effects of the president’s year in office but, again, differently for retirement and death in office: if Year12 = 1, then the absolute size of the effect of SameParty on Retirement hazard increases; if Year12 = 0 (that is, Year34 = 1), then the absolute size of the effect of SameParty on the death-in-office hazard increases. Second, Pension eligibility greatly increases expected retirement hazard, but its effect on death-in-office hazard is not statistically significant. Third, other things being equal, calendar year effects would cause death-in-office hazards to decline steadily since 1789 and would cause retirement hazards to decline very rapidly in the eighteenth century, taper off quickly, and now recede at a small annual rate. And, fourth, Tenure shows no effect on expected odds of death in office, but Tenure shows negative effects on expected retirement odds for justices with less than 25 years of experience on the Court, and increasing positive effects thereafter.

Because retirement and death in office are disjoint events, the hazard that a justice retires or dies in office is the sum of the hazards of death in office and retirement. To some extent, these differences in predicted hazards are a consequence of the different coefficients just discussed. However, those coefficients are not sufficiently identified to permit comparisons between different equations. However, probabilities and odds that are estimated from different equations are identified and can be compared. Finally, comparisons of individual coefficients leave open the possibility that the effect of one independent variable offsets the effect of another; unless otherwise indicated, the estimated probabilities and odds reported here include effects of all independent variables at once.

| Hazard of Retirement | Hazard of Death in Office | Hazard of Either | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 0.0303 | 0.0259 | 0.0562 |

| SD | 0.0468 | 0.0306 | 0.0615 |

| Minimum | 0.0007 | 0.0006 | 0.0028 |

| Maximum | 0.4743 | 0.2553 | 0.5873 |

| n (justice-years) | 1,895 | 1,895 | 1,895 |

REFERENCES

- Abel E, Kruger M. “The Longevity of Baseball Hall of Famers Compared to Other Players”. Death Studies. 2005;29:959–63. doi: 10.1080/07481180500299493. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abraham HJ. Justices and Presidents and Senators: A History of the US Supreme Court Appointments From Washington to Clinton. Revised ed. New York: Oxford University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Allison PD. Survival Analysis Using the SAS System: A Practical Guide. Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc; 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Atkinson DN. Leaving the Bench: Supreme Court Justices at the End. Lawrence, KS: Kansas University Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Baker M, Stabile M, Deri C. “What Do Self-Reported, Objective, Measures of Health Measure?”. Journal of Human Resources. 2004;39:1067–93. [Google Scholar]

- Baron JN, Pfeffer J. “The Social Psychology of Organizations and Inequality”. Social Psychology Quarterly. 1994;57:190–209. [Google Scholar]

- Barrow DJ, Gryski GS, Zuk G. The Federal Judiciary and Institutional Change. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press; 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Barrow DJ, Zuk G. “An Institutional Analysis of Turnover in the Lower Federal Courts, 1900–1987”. Journal of Politics. 1990;52:457–76. [Google Scholar]

- Bibb R, Form W. “The Effects of Industrial, Occupational, and Gender Stratification on Wages in Blue Collar Labor Markets”. Social Forces. 1977;55:974–96. [Google Scholar]

- Biskupic J. “The Next President Could Tip High Court.”. USA Today. 2004 Sep 29; [Google Scholar]

- Blau P. Exchange and Power in Social Life. New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Books; 1986. [Google Scholar]