Abstract

Racial and ethnic inequality in homeownership remains stubbornly wide, even net of differences across groups in household-level sociodemographic characteristics. This article investigates the role of contextual forces in structuring disparate access to homeownership among minorities. Specifically, I combine household- and metropolitan-level census data to assess the impact of metropolitan housing stock, minority composition, and residential segregation on black and Hispanic housing tenure. The measure of minority composition combines both the size and rate of growth of the coethnic population to assess the impact on homeownership inequality of recent trends in population redistribution, particularly the increase in black migration to the South and dramatic dispersal of Hispanics outside traditional areas of settlement. Results indicate remarkable similarity between blacks and Hispanics with respect to the spatial and contextual influences on homeownership. For both groups, homeownership is higher and inequality with whites is smaller in metropolitan areas with an established coethnic base and in areas in which their group is less residentially segregated. Implications of recent trends in population redistribution for the future of minority homeownership are discussed.

In spite of increased minority suburbanization and the favorable lending and regulatory environment that bolstered minority homeownership during the 1990s (Bostic and Surette 2001; Freeman 2005; Freeman and Hamilton 2004), racial and ethnic inequality in home-ownership remained stubbornly high.1 There is also ample reason to expect that inequality has widened with the recent U.S. housing crisis, as minorities were disproportionately represented among subprime mortgages. This persistent inequality is troublesome because homeownership is a central dimension of well-being and the centerpiece of wealth, representing the single largest asset for most households. Owning a home provides important financial and nonfinancial benefits. It constitutes an important form of forced savings and confers numerous tax benefits, inflation protection, and the opportunity for asset appreciation. At the same time, homeownership is positively associated with neighborhood amenities, including school quality, public services, and health and physical safety (Yinger 1995). Thus, understanding the factors limiting minority access to homeownership is central to racial and ethnic stratification because it both reflects and contributes to inequality in a wide array of socioeconomic arenas (Conley 1999).

Efforts to explain ethno-racial disparities in homeownership and housing wealth based on household- and individual-level factors have proven to be only partially successful (Oliver and Shapiro 1995). Even after differences in socioeconomic, human capital, and family structure characteristics across groups have been accounted for, minority members remain less likely to own a home, wait longer to transition into homeownership, and need higher income than whites to do so (Bianchi, Farley, and Spain 1982; Charles and Hurst 2002; Dawkins 2005; Flippen 2001a; Gyourko and Linneman 1997; Henretta 1979; Horton 1992; Jackman and Jackman 1980; Krivo 1986; Long and Caudill 1992; Megbolugbe and Cho 1996; Myers and Chan 1995; Parcel 1982; Rosenbaum 1996; Sykes 2003; Wachter and Megbolugbe 1992). In response, researchers have increasingly turned their attention to the ways in which social context structures minority homeownership attainment. For instance, metropolitan housing stock characteristics, racial segregation, and minority composition have been found to structure access to homeownership above and beyond personal and household-level factors (Alba and Logan 1992; Borjas 2002; Deng, Ross, and Watcher 2002; Flippen 2001b; Freeman 2005; Krivo 1995; Lee and Myers 2003; Myers et al. 2005; Toussaint-Comeau and Rhine 2000).

However, although a number of studies address the issue, the tendency to focus on different aspects of metropolitan context in research on blacks and Hispanics results in a lack of theoretical integration. Much of the research on blacks focuses on the impact of residential segregation, and an understanding of the effect of segregation on Hispanics is incomplete. Conversely, much of the research on minority composition and homeownership stemmed from interest in Hispanics and immigrant adaptation. Although some of these studies also included black samples, they did not simultaneously consider the impact of segregation and minority composition. As a result, the comparability of the findings is undermined, and the question of whether macro-level processes similarly affect the two groups remains unclear.

Separating the net effects of diverse metropolitan characteristics on minority home-ownership is growing in importance because of dramatic changes in internal migration patterns. Specifically, the 1990s witnessed a major increase in the movement of blacks to the South, which has been dubbed the “new” great migration (Frey 2004). In fact, during the 1990s, the South registered a net gain in black migration from all three other regions in the United States, a major reversal of a 35-year-old trend. In addition, the 1990s witnessed tremendous dispersal of the Hispanic population outside traditional receiving areas, with numerous metro and nonmetro areas across the Midwest and South experiencing exponential growth in their Hispanic populations (Suro and Singer 2002). Because these changes are relatively recent, their implications for minority well-being—including homeownership—remain unclear.

Accordingly, this article combines household- and metropolitan-level data from the 2000 census to analyze the spatial dynamics of racial and ethnic homeownership inequality. The theoretical framework integrates the diverse mechanisms through which metropolitan context shapes ethno-racial homeownership inequality—namely, housing stock, residential segregation, and minority composition—into a single framework to disentangle their unique effects. In addition, I explore what recent population redistribution portends for minority homeownership by incorporating internal migration patterns into the dimension of minority composition. Finally, I explicitly compare the impact of context on black and Hispanic homeownership, addressing an important deficit in the literature on Hispanics, now the largest U.S. minority group, and providing an important point of comparison for the more familiar case of black-white inequality.

THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK

A long history of sociological research has addressed the impact of context on racial and ethnic inequality. A central tenet of this work is that contextual forces structure socioeconomic opportunities for minorities above and beyond individual- and family-level characteristics and that disadvantaged geographic location can be a powerful impediment to social mobility (Massey and Denton 1993; Wilson 1996). The mechanisms connecting context and homeownership, however, are diverse and have yet to be incorporated into an integrated approach. Building on previous research on housing quality, residential segregation, and tenure, I argue that metropolitan context affects minority homeownership through three distinct mechanisms: housing stock, residential segregation, and minority composition.

Housing Stock

Variation in housing stock is an important mechanism through which metropolitan context affects homeownership. Metro areas vary widely in relative housing values, the share of housing that is single family and owner occupied, and the physical age and condition of housing stock. These dimensions capture infrastructural and housing market characteristics that bound the opportunities for homeownership.

Average home prices and their position relative to average rents are directly connected to homeownership (Lee and Myers 2003; Myers et al. 2005). However, the effects are not always uniform across racial and ethnic groups. Although higher housing values discourage homeownership across the board, the negative association is stronger among minorities (Flippen 2001b), likely attributable to their more limited access to credit relative to whites.

Likewise, the share of all housing that is single family or owner occupied has also been found to affect homeownership. Markets with a greater share of owner-occupied and single-family housing appear to represent more favorable supply conditions and are more conducive to homeownership (Dawkins 2005; Flippen 2001b; Lee and Myers 2003). The same applies to the share of housing that is relatively new (Clark, Deurloo, and Dieleman 1994), although it is not clear whether this signals a greater supply of housing relative to population or lower barriers to entry. There is evidence that new construction may help foster minority homeownership in particular, by stimulating a “filtering down” of housing stock; as upper-income groups move into new units, they create opportunities for previously excluded groups. Discriminatory treatment may also be lower in newer than more-established areas (Farley and Frey 1994; Logan, Stults, and Farley 2004; White, Fong, and Cai 2002) because they are less likely to have a well-defined ethnic identity that encourages racial steering and other segregation-enhancing practices.

Residential Segregation

Another contextual factor argued to impact minority homeownership is residential segregation. A vast literature documents the deleterious effects of racial segregation on minorities along a wide array of outcomes, including housing. First, the residential segregation of minority groups coincides with the spatial concentration of disadvantage, including poverty, housing deterioration, and inferior public services, particularly education. Segregated minority neighborhoods also exhibit above-average rates of crime, unemployment, single parenthood, and dependence on public assistance (Krivo et al. 1998). The overlap between minority concentration and social disadvantage reduces the attractiveness of segregated neighborhoods, undermining housing values (Flippen 2004; Harris 2001; Kim 2000) and acting as a disincentive to housing investments. Second, residential segregation restricts the supply of housing available to minorities. Housing discrimination tends to confine minorities to a subset of neighborhoods comprising a relatively small share of the urban environment. Because housing in minority submarkets tends to be disproportionately older, more dilapidated, and more multi-unit, opportunities for homeownership are diminished (Flippen 2001b; Kain and Quigley 1972).

Measuring the impact of segregation on minority homeownership is complex, however, and recent empirical analyses have found mixed results. In particular, there is disagreement about whether segregation has a direct effect on minority homeownership or whether it is housing stock conditions associated with highly segregated areas that account for the effect. On the side of a direct effect, Flippen (2001b) found that black residents of more highly segregated metropolitan areas averaged lower homeownership than their peers in less-segregated areas across a wide variety of measures of segregation, even after some elements of housing stock are accounted for. Freeman (2005) likewise found that black renters in metro areas with medium and high levels of dissimilarity were less likely to transition into homeownership, although those in metro areas with the highest levels of isolation were more likely to become owners.

Dawkins (2005), on the other hand, examined the association between neighborhood characteristics and transition into first homeownership. He argued that it is not segregation per se that undermines black homeownership, but rather its association with lower housing values, a smaller share of owner-occupied units, central city location, and concentration of older housing units. Likewise, in an analysis of Philadelphia, Deng and colleagues (2002) found that more-segregated neighborhoods had higher equity risk and concentrated poverty, which undermined minority homeownership. However, the lower average price of homes in segregated neighborhoods facilitated homeownership, resulting in a weak but positive association between neighborhood segregation and black homeownership.

Research on the impact of segregation on Hispanic well-being is far more limited. The literature on Hispanics tends to focus on enclaves and minority composition rather than on segregation per se. The few studies available that specifically examine the impact of segregation on Hispanic homeownership show more mixed effects than have been found for blacks. For instance, elsewhere (Flippen 2001b) I found that like blacks, segregation in some instances depresses Hispanic homeownership. However, measures of segregation that are more closely related to minority composition and enclave economies—namely, evenness, isolation, and clustering—were actually positively associated with Hispanic homeownership, a pattern not found among blacks.

Minority Composition

The final contextual factor argued to impact minority homeownership is the minority composition of the local area, or size of the coethnic community. From a theoretical standpoint, one could posit both protective and harmful effects of living in areas of high coethnic representation on minority homeownership. On the positive side, higher minority representation could foster the creation of an “institutional ghetto,” or enclave economy, whereby a parallel real estate industry develops to serve the excluded group, potentially facilitating access to homeownership by buffering against discrimination in the wider market. A large coethnic community could also facilitate homeownership by enhancing the diffusion of information and lowering the fixed costs of targeting services to minorities, such as providing services in a foreign language (McConnell and Marcelli 2007). This could be particularly important for immigrants, whose limited English fluency and lack of knowledge about U.S. lending and real estate markets pose a significant barrier to homeownership. And finally, the presence of other coethnics with similar preferences and attitudes could act as an amenity that makes homeownership more attractive in areas with larger coethnic populations.

At the same time, several factors suggest the deleterious impact of a large coethnic community on homeownership. As minority groups become larger, they could generate increased perception of threat by the majority group, stimulating discriminatory treatment. For immigrants, enclaves could hinder assimilation by reducing incentives to learn the local culture and language (Borjas 2002). Indeed, there is intense debate over whether immigrants fare better or worse in ethnic economies (Cutler, Glaeser, and Vigdor 2007). High minority representation could also result in saturation effects if coethnics tend to have similar educational and employment credentials and similar demand for housing.

Empirical examinations of the impact of minority composition on homeownership generally find either positive or benign effects. For instance, Alba and Logan (1992) reported that the size of the coethnic population at the metropolitan level was positively associated with homeownership for Mexicans and Cubans and had no effect on blacks; the effect was negative, however, for Puerto Ricans and Asians. Gabriel and Painter (2003) reported that among movers in Los Angeles, black homeownership was positively associated with the percentage of blacks in the target area. Myers and colleagues (2005) found that homeownership gains for both blacks and Hispanics between 1980 and 1990 were greatest in metro areas where the size of their group was larger. Likewise, Borjas (2002) reported that in 1980 and 2000 there was a significant positive relationship between the probability of Hispanic immigrant homeownership and the relative size of the metro ethnic enclave.

Recent trends in population redistribution present an original opportunity for a more nuanced understanding of the link between minority context and homeownership. Black migration to the South and increased Hispanic dispersion has widened variation in minority metropolitan contexts; new areas of minority concentration have emerged as well as rapid growth of minorities in already established areas of settlement. As a result, it is possible to take a more dynamic view of the role of the ethnic community and elaborate on both the effect of size and change in minority composition on homeownership. Although most previous studies have concentrated on the former, it is unclear what rapid minority growth portends for homeownership or how size of the ethnic community and growth combine in affecting minority outcomes.

For example, Borjas (2002) found that Hispanic immigrant homeownership was enhanced not only by the size of the coethnic community in 1980 but also by its rate of growth between 1980 and 2000. One could hypothesize that rapid minority growth increases the incentive to target services. Alternatively, the relationship between minority growth and homeownership could be spurious, resulting from other metro characteristics that are both attracting new residents and facilitating homeownership, such as relatively low housing prices or an ample supply of owner-occupied housing.

Understanding this connection is increasingly relevant given the continuing dispersion of minority groups. Moreover, the fact that patterns of settlement and growth differ considerably among blacks and Hispanics suggests that residence in a particular metropolitan area could have vastly different implications across groups.

DATA AND METHODS

I combined household level information from the 5% sample of the 2000 Census of Population and Housing with metropolitan-level2 data on housing context, residential segregation, and minority composition to test my integrated framework for understanding minority housing tenure. The household-level information was restricted to household heads aged 25 to 40,3 the most pertinent group for the transition into homeownership. Metropolitan-level information was constructed by aggregating information from the 5% sample of the 2000 census by metropolitan area as well as obtaining estimates of residential segregation, population size, and minority composition directly from the Census Bureau’s calculations based on 100% counts.

Given my focus on racial and ethnic composition, I restrict the sample to metropolitan areas with at least 10,000 black or Hispanic residents in 2000 because smaller populations may not render meaningful segregation scores and contextual indicators. This restriction resulted in a total of 217 and 195 metropolitan areas for the analysis of blacks and Hispanics, respectively.4

Model Specification

The dependent variable in the analysis is housing tenure in 2000. Predictors include both household and metropolitan characteristics, resulting in a two-level model of homeownership in which households are nested within particular metropolitan areas. Individual household characteristics follow those from the classical microeconomic model of consumer choice, which posits that households make decisions regarding consumption, including housing, according to their needs and preferences, subject to their financial resources. I therefore control for age, marriage, childbearing, education, occupation, employment status, self-employment, and disability status. (See Appendix Table A1 for more precise definitions.) I also consider immigrant characteristics: nativity; duration of U.S. residence (for immigrants);5 and for Hispanics, national origin and race.

My main emphasis is on the metropolitan-level factors that shape homeownership. As described earlier, I include three aspects of metropolitan housing stock central to homeownership: the average cost of ownership is captured by median metropolitan housing values; the percentage of housing that is owner occupied captures variation in the relative availability of housing for purchase; and the proportion of owner-occupied units built within the 10 years prior to the census assesses the potential for new construction to facilitate homeownership. I also control for the overall size of the housing market by including a measure of the total metro population. All variables are calculated based on the metropolitan area and are not race-specific.

Segregation is a multidimensional concept that can be measured in numerous ways. Massey and Denton (1989) identified five dimensions of segregation: evenness (the differential distribution of groups across a metropolitan area), exposure (the degree of potential interaction between groups), clustering (the extent to which areas inhabited by a group adjoin one another), centralization (the degree to which a group is located near the center of an urban area), and concentration (the relative amount of physical space available to minority members).

Although closely associated and interrelated, the dimensions of segregation reflect conceptually distinct ways through which segregation affects life chances for minorities (Wilkes and Iceland 2004). For analyses of homeownership, residential concentration is arguably the dimension of most theoretical significance. Other aspects of segregation such as evenness, exposure, and clustering reflect to a certain extent the degree of contact between groups and potentially confound the effect of minority composition with that of segregation. More importantly, concentration directly affects housing opportunities because higher levels of concentration reflect restrictions on the physical space and share of the overall housing market available to minorities. Centralization also captures physical restrictions associated with residing in urban areas. However, the supply restrictions imposed by centralization are more relevant in older industrial cities than in rapidly growing and newly emerging areas of destination. In addition, concentration is arguably the dimension of segregation most directly linked to the concentration of poverty that undermines homeownership via its negative impact on housing appreciation.

I therefore focus on concentration as my measure of residential segregation. Massey and Denton (1989) identified three indices of concentration: Delta (DEL), Absolute Concentration (ACO), and Relative Concentration (RCO). DEL is a variation of the dissimilarity index and thus does not precisely capture the separate role of spatial concentration. ACO is an absolute measure that computes the total area inhabited by a group and compares this with the minimum and maximum areas that could accommodate a group of that size at observed densities. As a relative measure, the RCO is computed similarly to ACO but takes into account the distribution of the majority group as well. This measure generally varies from −1.0 to 1.0, where a score of 0 means that the minority and majority groups are equally concentrated, +1.0 means that minority concentration exceeds that of the majority to the maximum extent, and an index of −1.0 is the converse. Because RCO computes the area occupied by minority groups relative to the majority, it accounts for metro differences in the extent to which minorities are more physically constrained than whites and is thus more appropriate for my purposes. Estimates of RCO were obtained from the Census Bureau’s calculations computed with data from 100% sample and using census tracts as the level of the areal unit.6

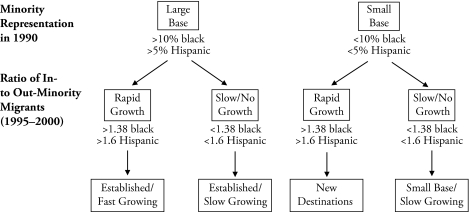

Finally, a central focus of the analysis is the connection between minority composition, population redistribution, and minority homeownership. I capture that connection by constructing a typology of minority context that combines two factors: minority representation in 1990, and the ratio of in- to out-minority migrants between 1995 and 2000. To construct the typology, I first distinguish between metropolitan areas with and without an established coethnic base. Using the median percentage coethnic as a dividing point, metro areas that are at least 10% black or 5% Hispanic in 1990 are designated as having an established coethnic base, and all others as having small initial minority representation. Second, within each group, I distinguish between rapidly and more slowly growing coeth-nic populations. Using the individual-level data on residential location in 1995 and 2000 for individuals aged 25 to 65 (weighted to represent the total population), I computed the ratio of black and Hispanic domestic in- to out-migrants across metropolitan areas. This measure is preferable to simpler measures of change in the proportion minority because the latter is also influenced by changes in the size of other groups. Again using the median values as a dividing line, areas with in- to out-migration rates higher than 1.38 and 1.60 for blacks and Hispanics, respectively, are considered rapid growth areas, and others are considered slow-growing areas.

These distinctions result in four mutually exclusive categories, depicted in Figure 1: areas with an established and rapidly growing coethnic population; areas with an established and slow-growing coethnic population; new destinations (i.e., areas with a small coethnic population in 1990 that grew rapidly over the decade); and metro areas with a small and slow-growing coethnic population.

Figure 1.

Definition of Minority Composition Typology for Metropolitan Areas

Note: Cutoff points are set at the median values for percentage black and Hispanic in 1990 and migration ratio.

The strategy of comparing across metropolitan areas to identify the effect of population trajectories on socioeconomic outcomes has been extensively applied in analyses of the impact of immigration on native workers’ wages (Borjas 2003; Card 2005). As applied to housing tenure, this typology is a useful heuristic tool, allowing for connections to other scholarship on recent trends in minority dispersion that refer to concepts such as new versus established areas of destination. It also allows me to visualize patterns of minority concentration and growth and to group similar metro areas, giving a more intuitive sense for the findings. The downside of a typology is that it reduces the variation present in a continuous specification. To ensure that study findings are not an artifact of how the typology was created, I also ran all models with continuous specifications of the percentage minority and migration ratio. Findings are remarkably similar across specifications, strengthening confidence in the utility of the typology for understanding the impact of context of homeownership across groups.

Analytic Strategy

Because the clustering of households within metropolitan areas violates the independence assumption in standard regression, I formulate a hierarchical logit model, with predictors working at two levels (Raudenbush et al. 2004). I conduct two separate but interrelated analyses. First, I model the impact of metropolitan characteristics on within-group housing tenure separately for blacks and Hispanics. Second, I model the effect of metro characteristics on ethno-racial homeownership disparities with whites. This model allows me to ascertain not only whether minority members are more likely to own in certain contexts than in others but also whether context is related to the degree of inequality with whites. This also helps assess the role of unmeasured aspects of metropolitan context in structuring observed relationships. For instance, if residential segregation were negatively associated with minority housing tenure, it could indicate that segregation undermines minority homeownership or rather that some other unmeasured aspect of highly segregated cities was detrimental to homeownership for all groups.

For the first analysis of within-group differences in housing tenure, the two-level logit model takes the following form:

Level 1: log[P / (1 − P)]ij = β0j + βqjXqij

Level 2: β0j = γ00 + γ0sYsj + μ0j

where Pij is the probability of homeownership for household i in metropolitan area j; β0j is an intercept term; and Xqij are household-level covariates q for household i in metropolitan area j associated with βqj parameters to be estimated. The Level 1 intercept (β0j) is modeled at Level 2, where γ00 is an intercept, Ysj are metropolitan-level covariates s for metropolitan area j associated with γ0s coefficients, and μ0j is a random effect that is normally distributed with mean of 0 and variance τ00. In substantive terms, by estimating the intercept in Level 2, this model captures metropolitan variation in homeownership propensities and its covariates (i.e., what contextual factors contribute to differential rates of homeownership across cities). The model is estimated separately for blacks and Hispanics.

The second analysis extends this specification to understand racial and ethnic disparities as follows:

Level 1: log[P / (1 − P)]ij = β0j + β1j(B / H)1ij + βqjXqij

-

Level 2: β0j = γ00 + γ0sYsj + μ0j

β1j = γ10 + γ1sYsj + μ1j

where B / H is a dummy variable indicating whether the household head is black or Hispanic, and β1j is the associated coefficient. In addition to the Level 1 intercept (β0j) at Level 2, I also model the black/Hispanic coefficient (β1j), where γ10 is an intercept; Ysj are metropolitan-level covariates s for metropolitan area j associated with γ1s coefficients; and μ1j is a random effect that is normally distributed with mean of 0 and variance τ11. Substantively, this specification allows us to assess whether the effect of metropolitan characteristics on homeownership is different for whites and minorities (for instance, whether residential segregation also influences white housing tenure). The model is estimated separately by pooling the data for blacks and whites and for Hispanics and whites.

DESCRIPTIVE ANALYSIS

Geographic Distribution of Metro Typology

Maps of the metro typology across the country (Figures S1 and S2 available on Demography’s website: http://www.populationassociation.org/publications/demography) clearly show that for blacks, the vast majority of established black areas are in the South, Midwest, and lower Northeast. (Table S1, also on Demography’s website, provides a complete list of the metro areas in each category.) The established and fast-growing areas are overwhelmingly in the South, including Houston, TX; Atlanta, GA; Dallas, TX; and Fort Lauderdale, FL; but also include some midwestern areas such as Indianapolis, IN; Columbus, OH; and Milwaukee, WI. Established and slow-growing metro areas for blacks are somewhat more spread out and northern, including New York, NY; Chicago, IL; Philadelphia, PA; and Detroit, MI; but also several metropolitan areas in California, such as Los Angeles and Oakland.

New destinations for blacks are concentrated in the West, including Riverside, CA; Phoenix, AZ; Portland, OR; Las Vegas, NV; and Austin, TX. There are also a number of new destinations in the Midwest, such as Minneapolis, MN, and Grand Rapids, MI. Finally, metro areas with a small base and slow growth for blacks are more widespread but are somewhat concentrated in the Northeast, in cities such as Boston, MA; Nassau, NY; and Pittsburgh, PA. They also include a number of western metro areas, such as San Diego, CA; Seattle, WA; Denver, CO; and San Francisco, CA.

The Hispanic typology (listed in Table S2 on Demography’s website) is distributed quite differently, and in many ways, opposite to the black pattern. First, and not surprisingly, established areas are concentrated in the West, South Florida, and a relatively small part of the Northeast. Established and fast-growing Hispanic areas include Dallas, TX; Riverside, CA; Phoenix, AZ; Denver, CO; Las Vegas, NV; and Fort Lauderdale, FL. Established and slower-growing metro areas include many of the traditional gateway cities, including Los Angeles, CA; New York, NY; Chicago, IL; Houston, TX; San Diego, CA; Oakland, CA; and Miami, FL.

New destinations for Hispanics are concentrated in areas that for blacks are established and growing, mostly in the South and Midwest. These include southern metro areas such as Atlanta, GA; Charlotte, NC; Nashville, TN; and Raleigh-Durham, NC; and midwestern areas, such as Detroit, MI; Minneapolis, MN; Indianapolis, IN; Columbus, OH; and Milwaukee, WI. Finally, metro areas with a small and slow-growing Hispanic base are scattered through the Northeast, the Midwest, and to a lesser extent the South. These include metro areas such as Philadelphia, PA; Boston, MA; St. Louis, MO; Baltimore, MD; Cleveland, OH; and Norfolk, VA.

Overall, blacks are more widely dispersed and less concentrated than Hispanics. No metro area was more than 52% black in 2000, but 10 were more than 50% Hispanic. A small number of metro areas exhibited extremely high proportions of Hispanic residents, a prime example being Laredo, TX, where 94% of the population was Hispanic. At the same time, more than 100 metro areas were at least 12% black (the national average), while only 70 were 12% or more Hispanic, in spite of the roughly comparable size of the two populations nationally. There is also more overlap in the residential location of blacks and whites than is the case for Hispanics and whites. This is because blacks and whites are both part of the increased migration from Rust Belt to Sun Belt areas. Hispanics participate in this trend as well but also continue to move to traditional gateway metro areas, such as New York and Los Angeles, that are experiencing declines in their white and black populations.

Homeownership by Race and Metro Typology

Before presenting data from the regression models, it is instructive to examine the bivariate relationship between homeownership and minority composition. Table 1 shows that homeownership rates rose from 1990 to 2000 for blacks in all metro types, but the growth was most pronounced in established and growing metro areas, which also began the period with markedly higher homeownership than other areas. A somewhat different pattern holds for Hispanics. Similar to blacks, the highest rates of homeownership among Hispanics were registered in established and growing metro areas. However, rather than seeing rising homeownership across all metro categories, metro areas with a small base and slowly growing Hispanic population show stagnant homeownership rates during the period. In new destinations, rates actually fell precipitously, most likely because newcomers are less likely than others to own and also because of the increase in the share of foreign-born over the decade.

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics for Black and Hispanic Minority Composition Typology

| Variable | Established and Growing | Established and Slow/Not Growing | New Destinations (small base) fast growing) | Small and Slow/Not Growing |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Homeowner, 1990 | ||||

| Black typology | 43.8 | 40.4 | 40.3 | 38.2 |

| Hispanic typology | 49.6 | 40.1 | 46.8 | 40.4 |

| % Homeowner, 2000 | ||||

| Black typology | 47.7 | 42.7 | 41.8 | 40.6 |

| Hispanic typology | 51.7 | 42.7 | 40.7 | 40.5 |

| % Black/Hispanic, 2000 | ||||

| Black typology | 24.0 | 20.7 | 7.6 | 6.9 |

| Hispanic typology | 18.6 | 29.1 | 5.1 | 4.2 |

| Total Population | ||||

| Black typology | 789,340 | 1,387,061 | 782,442 | 836,742 |

| Hispanic typology | 924,419 | 1,255,195 | 878,103 | 995,765 |

| Median Housing Values | ||||

| Black typology | 99,795 | 115,576 | 117,062 | 136,289 |

| Hispanic typology | 130,902 | 157,336 | 110,738 | 113,243 |

| Percentage Owner-Occupied | ||||

| Black typology | 65.8 | 63.0 | 66.4 | 65.4 |

| Hispanic typology | 64.1 | 59.6 | 67.3 | 65.9 |

| Percentage New Construction | ||||

| Black typology | 27.9 | 21.3 | 23.1 | 18.7 |

| Hispanic typology | 22.7 | 20.5 | 24.2 | 19.5 |

| Relative Concentration | ||||

| Black typology | 0.48 | 0.62 | 0.64 | 0.65 |

| Hispanic typology | 0.37 | 0.42 | 0.45 | 0.46 |

| N | ||||

| Black typology | 61 | 52 | 40 | 64 |

| Hispanic typology | 36 | 61 | 61 | 37 |

These patterns are not conclusive, however, because the metro types vary on a number of dimensions relevant to homeownership, also described in Table 1. Variation in racial composition across metro types follows how they were defined. Among blacks, established areas averaged between 20% and 24% black and small-base metro areas were 7% to 8% black in 2000. For Hispanics, established areas were more diverse, averaging 19% and 29% Hispanic, and small-base metro areas averaged 4% to 5% Hispanic in 2000. For both the black and Hispanic typologies, established and slow-growing areas averaged the largest and new destinations the smallest overall population sizes.

Housing stock conditions also vary across metro types. In the black typology, median housing values are lowest in established and growing areas, and highest in the places with small and slow-growing black populations. For Hispanics, places with an established base, particularly slow-growing areas, average higher housing costs, but small-base metro areas are considerably less expensive overall. Although the share of all housing that is owner occupied does not vary tremendously across the black typology, among Hispanics, the figure is somewhat lower in established and slow-growing metro areas. Not surprisingly, for both black and Hispanic typologies, there is more new housing in faster- than in slower-growing areas. Finally, in both typologies, residential concentration is lowest in established and growing areas and is markedly higher in all other metro types, particularly those with a small coethnic base.

MULTIVARIATE RESULTS

Metropolitan Influences on Within-Group Variation in Homeownership

Table 2 presents results from the random intercept logit model that estimates the impact of metropolitan characteristics on the overall likelihood of black (top panel) and Hispanic (bottom panel) homeownership. Because household-level predictors of homeownership are well established in the literature and are not the primary focus of the current analysis, they are presented in Appendix Table A1 and not described in detail. For both blacks and Hispanics, factors related to housing demand—such as age, marital status, and childbearing—all predict homeownership in the expected direction, as do indicators of households’ financial position, such as education, household income, occupation, and employment status. Factors relating to immigration, such as nativity and time in the United States among immigrants, also behave in accordance with findings of previous studies.

Table 2.

Hierarchical Logit Analysis of Metropolitan Effects on Black and Hispanic Homeownership (standard errors in parentheses)

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blacksa | ||||

| Minority composition typology (ref. = established, slow growing) | ||||

| Established, growing | 0.205* (0.073) | 0.158* (0.069) | 0.015 (0.046) | 0.002 (0.046) |

| New destinations | −0.151† (0.087) | −0.115 (0.082) | −0.262* (0.056) | −0.252* (0.056) |

| Small base, slow growing | −0.452* (0.076) | −0.381* (0.073) | −0.463* (0.048) | −0.468* (0.048) |

| Housing stock | ||||

| Population size (log) | −0.010 (0.029) | −0.008 (0.019) | 0.012 (0.019) | |

| Median housing value (log) | −0.453* (0.086) | −0.211* (0.059) | −0.239* (0.059) | |

| % owner-occupied | 0.033* (0.003) | 0.034* (0.003) | ||

| % new | 0.008* (0.002) | 0.004† (0.002) | ||

| Residential segregation | ||||

| Relative concentration | −0.300* (0.066) | |||

| Variance between cities | 0.131 | 0.113 | 0.034 | 0.034 |

| Hispanicsa | ||||

| Minority composition typology (ref. = established, slow growing) | ||||

| Established, growing | 0.278* (0.110) | 0.239* (0.079) | 0.021 (0.064) | 0.027 (0.062) |

| New destinations | 0.109 (0.098) | −0.055 (0.074) | −0.326* (0.063) | −0.311* (0.061) |

| Small base, slow growing | 0.045 (0.115) | −0.108 (0.088) | −0.288* (0.073) | −0.283* (0.071) |

| Housing stock | ||||

| Population size (log) | 0.004 (0.030) | 0.017 (0.023) | 0.026 (0.023) | |

| Median housing value (log) | −0.776* (0.075) | −0.585* (0.061) | −0.585* (0.059) | |

| % owner-occupied | 0.035* (0.003) | 0.034* (0.003) | ||

| % new | 0.009* (0.003) | 0.007* (0.003) | ||

| Residential segregation | ||||

| Relative concentration | −0.173* (0.075) | |||

| Variance between cities | 0.249 | 0.120 | 0.061 | 0.055 |

Individual- and household-level coefficients from Model 1 are presented in the first column of Appendix Table A1 for blacks and the second column of Appendix Table A1 for Hispanics.

p < .10;

p < .05

Results from Model 1 in the top panel of Table 2 show that net of individual and household characteristics, the likelihood of homeownership among blacks varies considerably across metro types. Compared with their counterparts living in established and slow-growing metro areas, blacks living in established and fast-growing metro areas are 23% (exp(0.205)) more likely to own a home. At the same time, those living in new destinations or metro areas with small and slow-growing black populations are 14% (1 − exp(−0.151)) and 36% (1 − exp(−0.452)) less likely to own than their peers in established and slow-growing metro areas, respectively. These effects remain when I control for metro population size and housing prices in Model 2. However, when I include additional controls for housing stock, the positive effect of residence in an established and fast-growing metro area falls to insignificance (Model 3). This suggests that the beneficial effects of residence in established and fast-growing metro areas is partly a reflection of the newer and more owner-occupied housing available in these contexts. The negative effects of residence in metro areas with a small black base—either new destinations or slow-growing areas—remain through the final model, underscoring the importance of minority composition to black homeownership above and beyond its association with housing stock and residential segregation.

The effect of housing stock characteristics is consistent with findings from previous studies, and results do not differ considerably across models. Concentrating on Model 4, results show that higher median housing prices decrease the likelihood of black home-ownership (−0.239). At the same time, residence in metro areas with higher percentage of owner-occupied and new housing facilitates homeownership. Result show that a 1% increase in the proportion of owner-occupied and new housing increases the odds of home-ownership by 3% (exp(0.034)) and 0.5% (exp(0.004)), respectively.

Finally, results for Model 4 support my expectation of a unique detrimental effect of residential segregation on black homeownership beyond its association with housing stock and minority composition. Specifically, a 1-point increase in RCO reduced the odds of black homeownership by 26% (1 − exp(−0.300)).

The bottom panel of Table 2 presents results from the same models for Hispanics. Overall, there is striking similarity with the black models. Results from Model 1 show that established and growing Hispanic metro areas average 32% higher rates of homeownership than slower-growing established areas (exp(0.278)); however, as is the case for blacks, this effect disappears in Model 3 when I account for the share of units that are owner occupied and new. This result highlights the importance of housing stock for understanding the advantage that minorities have in established and growing destinations.

Places with a small Hispanic base—both new destinations and slower-growing areas—at first do not appear to differ from established slow-growing areas. However, as shown in Table 1, small Hispanic places are more affordable and owner occupied, on average, than other areas. When I account for these characteristics in subsequent models, residing in a small-base metro area becomes clearly negatively associated with Hispanic home-ownership. In Model 4, the odds of Hispanic homeownership are 27% (1 − exp(−0.311)) and 25% (1 − exp(−0.283)) lower in new-destination and small-base, slow-growth metro areas relative to established, slow-growth cities, respectively.

It is worth pointing out that although the effect of minority composition trajectories is similar for both groups, in most cases, the metro designations do not overlap for blacks and Hispanics. Atlanta, for example, is a new destination for Hispanics but an established and growing metro area for blacks. The reverse is true of Phoenix. So the fact that the same negative effect of a small coethnic base is evident for both blacks and Hispanics suggests that this is not a place effect, but instead is capturing the effect of the presence or absence of a coethnic community on minority homeownership.

The impact of housing stock on Hispanic housing tenure is also remarkably similar to the black case. Estimates from Model 4 show that higher median housing values are negatively associated with homeownership propensities, while percentage owner-occupied and new housing facilitate ownership. As was the case for blacks, Hispanics living in metro areas with high levels of concentration relative to whites are significantly less likely to own a home than their counterparts in less-segregated metro areas. Estimates from Model 4 show that a 1-point increase in RCO decreases the likelihood of Hispanic homeownership by 16% (1 − exp(−0.173)).

Metropolitan Influences on Homeownership Disparities With Whites

I next turn to an analysis of how metro characteristics affect ethno-racial disparities with whites. Table 3 presents results from pooled models that estimate not only the effect of metro characteristics on the intercept but also on the slope for being black. The interpretation for the effect on the slope is similar to that of an interaction term in standard regression. For instance, Model 1 estimates the effect of metro characteristics only on the intercept (β0j) and can be interpreted as the effect of these characteristics on the likelihood of homeownership for both blacks and whites. When I add predictors of the black coefficient (β1j) in subsequent models, the effects on the intercept can be interpreted as the effect on whites and the effects on the coefficient as the difference in the effect between whites and blacks. Therefore, the sum of the effect on the intercept plus the effect on the coefficient is the total effect on blacks.

Table 3.

Hierarchical Logit Analysis of Metropolitan Effects on Black-White Homeownership Disparities (standard errors in parentheses)

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept Modela | |||||

| Minority composition/typology (ref. = established, slow growing) | |||||

| Established, growing | 0.000 (0.034) | −0.023 (0.042) | −0.025 (0.042) | −0.010 (0.040) | −0.008 (0.037) |

| New destinations | −0.173* (0.038) | −0.117* (0.045) | −0.113* (0.045) | −0.115* (0.042) | −0.118* (0.039) |

| Small base, slow growing | −0.291* (0.033) | −0.191* (0.039) | −0.184* (0.039) | −0.196* (0.036) | −0.190* (0.034) |

| Demographic and economic characteristics | |||||

| Population size (log) | 0.005 (0.013) | 0.009 (0.013) | 0.018 (0.016) | 0.016 (0.015) | 0.005 (0.014) |

| Median housing value (log) | −0.268* (0.040) | −0.271* (0.039) | −0.314* (0.047) | −0.296* (0.044) | −0.275* (0.041) |

| Housing market characteristics | |||||

| % owner-occupied | 0.039* (0.002) | 0.039* (0.002) | 0.039* (0.002) | 0.043* (0.002) | 0.043* (0.002) |

| % new | 0.004* (0.002) | 0.004* (0.002) | 0.004* (0.002) | 0.002 (0.002) | 0.004* (0.002) |

| Segregation | |||||

| Relative concentration | 0.026 (0.047) | 0.033 (0.046) | 0.027 (0.046) | 0.044 (0.046) | 0.218* (0.050) |

| Variance between cities | 0.026 | 0.023 | 0.023 | 0.017 | 0.014 |

| Black Slope Model | |||||

| Minority composition/typology (ref. = established, slow growing) | |||||

| Established, growing | 0.056 (0.063) | 0.061 (0.061) | 0.028 (0.057) | 0.013 (0.054) | |

| New destinations | −0.150* (0.075) | −0.159* (0.072) | −0.156* (0.066) | −0.146* (0.063) | |

| Small base, slow growing | −0.296* (0.066) | −0.315* (0.064) | −0.273* (0.057) | −0.287* (0.054) | |

| Demographic and economic characteristics | |||||

| Population size (log) | −0.029 (0.026) | −0.022 (0.023) | 0.012 (0.022) | ||

| Median housing value (log) | 0.128† (0.075) | 0.088 (0.069) | 0.034 (0.066) | ||

| Housing market characteristics | |||||

| % owner-occupied | −0.011* (0.003) | −0.009* (0.003) | |||

| % new | 0.007* (0.003) | 0.000 (0.003) | |||

| Segregation | |||||

| Relative concentration | −0.498* (0.075) | ||||

| Variance between cities | 0.083 | 0.072 | 0.063 | 0.040 | 0.033 |

Individual-and household-level coefficients from Model 1 are presented in the third column of Appendix Table A1.

p < .10;

p < .05

Beginning with Model 1, results show that on average there is no advantage to being in an established and growing black metro area relative to an established and slow-growing metro area. At the same time, new destinations and small-base, slow-growth cities average lower rates of homeownership overall [(exp(−0.173) = 0.841 and exp(−0.291) = 0.748, respectively)]. This suggests that my typology captures some general conditions in these cities that are less conducive to homeownership for both blacks and whites.

However, when I add the metro typology as a predictor of the black coefficient in Model 2, these effects differ for blacks and whites. Specifically, the negative effect of residing in metro areas with a small black base—either new destinations or small-base and slow-growing areas—is significantly stronger among blacks. Results show that for whites, the likelihood of owning a home is 11% (1 − exp(−0.117)) and 17% (1 − exp(−0.191)) lower in new destinations and small-base, slow-growth metro areas, respectively, relative to established and slow-growing cities. Among blacks, the odds are 23% (1 − exp(−0.117–0.150)) and 63% (1 − exp(−0.191–0.296)) lower, respectively. So not only is black homeownership lower in small-base metro areas relative to blacks in other areas, but inequality with whites is also larger in those cities. These effects remain even after I account for metro variation in housing stock and segregation.

An examination of the overall effect of metro housing stock characteristics (Model 1) reveals the same pattern as in the previous models: homeownership is negatively associated with median housing values and positively associated with the share of owner-occupied and new housing. Once again, though, there are significant differences by race (Model 5). Results show that the positive association between percentage owner occupied and homeownership is significantly weaker for blacks than for whites. Estimates indicate that although among whites, a one-unit change in the percentage homeowners increases the likelihood of homeownership by 4% (exp(0.043)), the effect is positive but significantly lower among blacks: 3% (exp(0.043–0.009)). Results from Model 4 show that blacks receive a significantly greater benefit from the share of housing that is new relative to whites but only because metro areas with more new housing tend to be less segregated. When I control for segregation in the final model, whites and blacks receive the same net benefit from new construction.

Finally, results for the effect of residential segregation differ across groups. In the general model (Model 1), black residential concentration has no overall effect on homeownership. However, after I separate the effect on blacks and whites, the effect works in opposite directions. Model 5 shows that although a one-unit increase in the relative concentration of blacks raises the likelihood of homeownership among whites by 24% (exp(0.218)), it decreases it by 24% (1 − exp(0.218–0.498)) among blacks.7

Table 4 presents results from the same set of analyses for Hispanics. As before, Model 1 estimates the overall effect of metropolitan characteristics on white and Hispanic homeownership. Contrary to the black case, though, the typology does not reflect overall differences in homeownership propensities applicable to both whites and Hispanics. It is only when the Hispanic coefficient is modeled (Model 2) that significant differences across groups emerge. For Hispanics, as is the case for blacks, areas with a small Hispanic base—both new destinations and small-base, slow-growth metro areas—average significantly lower homeownership than established slow-growing areas, and this effect remains even after adding housing stock and segregation measures in subsequent models. Specifically, Hispanics residing in new destinations or small-base, slow-growth areas are 25% (1 − exp(0.134–0.427)) and 23% (1 − exp(0.155–0.419)) less likely to own a home than their counterparts residing in established and slow-growing areas.

Table 4.

Hierarchical Logit Analysis of Metropolitan Effects on Hispanic-White Homeownership Disparities (standard errors in parentheses)

| Variable | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept Modela | |||||

| Minority composition/typology (ref. = established, slow growing) | |||||

| Established, growing | 0.042 (0.039) | 0.038 (0.046) | 0.078† (0.045) | 0.093* (0.047) | 0.090* (0.046) |

| New destinations | −0.038 (0.036) | 0.087* (0.041) | 0.141* (0.041) | 0.144* (0.042) | 0.134* (0.042) |

| Small base, slow growing | −0.002 (0.039) | 0.120* (0.044) | 0.167* (0.043) | 0.157* (0.045) | 0.155* (0.044) |

| Demographic and economic characteristics | |||||

| Population size (log) | 0.035* (0.013) | 0.040* (0.013) | 0.051* (0.015) | 0.051* (0.015) | 0.044* (0.015) |

| Median housing value (log) | −0.434* (0.036) | −0.419* (0.035) | −0.298* (0.041) | −0.303* (0.042) | −0.301* (0.042) |

| Housing market characteristics | |||||

| % owner-occupied | 0.038* (0.002) | 0.038* (0.002) | 0.038* (0.002) | 0.040* (0.002) | 0.040* (0.002) |

| % new | 0.005* (0.002) | 0.005* (0.002) | 0.005* (0.002) | 0.002 (0.002) | 0.004* (0.002) |

| Segregation | |||||

| Relative concentration | 0.057 (0.045) | 0.069 (0.044) | 0.080† (0.043) | 0.078† (0.043) | 0.196* (0.052) |

| Variance between cities | 0.022 | 0.018 | 0.016 | 0.017 | 0.016 |

| Hispanic Slope Model | |||||

| Minority composition/typology (ref. = established, slow growing) | |||||

| Established, growing | 0.027 (0.068) | −0.025 (0.073) | −0.062 (0.082) | −0.051 (0.079) | |

| New destinations | −0.374* (0.063) | −0.466* (0.069) | −0.458* (0.079) | −0.427* (0.076) | |

| Small base, slow growing | −0.390* (0.076) | −0.472* (0.082) | −0.429* (0.089) | −0.419* (0.085) | |

| Demographic and economic characteristics | |||||

| Population size (log) | −0.036 (0.028) | −0.034 (0.029) | −0.015 (0.028) | ||

| Median housing value (log) | −0.324* (0.070) | −0.294* (0.077) | −0.298* (0.074) | ||

| Housing market characteristics | |||||

| % owner-occupied | −0.005 (0.004) | −0.005 (0.004) | |||

| % new | 0.008* (0.003) | 0.003 (0.003) | |||

| Segregation | |||||

| Relative concentration | −0.365* (0.093) | ||||

| Variance between cities | 0.074 | 0.065 | 0.078 | 0.087 | 0.076 |

Individual-and household-level coefficients are from Model 1 presented in the fourth column of Appendix Table A1.

p < .10;

p < .05

For whites, on the other hand, places with a small Hispanic base average higher home-ownership rates than established and slow-growing areas (exp(0.134) and exp(0.155) in Model 5). This result is different from the white-black case and reflects the disparate geographic distribution of blacks and Hispanics. In the black case, new destinations and small-base, slow-growth areas are disproportionately located in the West in housing markets that negatively affect all groups, including whites. For Hispanics, though, new destinations and small-base, slow-growth areas tend to be located in the South in housing markets that are beneficial for homeownership for whites and blacks.

The effects of metro housing stock characteristics are once again in line with expectations. Overall, Model 1 shows that homeownership is positively associated with metro size and the share of all housing that is owner occupied and new, and negatively associated with average housing values. Once again, the effects differ significantly for whites and Hispanics. The negative effect of housing values on homeownership is significantly stronger for Hispanics than for whites. Model 5 shows that although a one-unit increase in median housing values decreases the likelihood of homeownership among whites by 26% (1 − exp(−0.301)), it decreases it by 45% (1 − exp(−0.301–0.298)) among Hispanics.

Also, the positive association between percentage new and homeownership is significantly stronger for Hispanics than for whites; in fact, it is significant only for Hispanics and not for whites overall. However, this is in part due to the lower residential segregation in those areas, and the effect is reduced to nonsignificance when concentration is accounted for in Model 5.

Finally, although Hispanic residential segregation appears to have no overall effect on homeownership (Model 1), as in the black case, segregation affects whites and Hispanics in opposite directions. A one-unit increase in the value of Hispanic RCO increases whites’ likelihood of homeownership by 21% (exp(0.196)) but decreases Hispanics’ by 16% (1 − exp(0.196–0.365).8

Simulated Minority Homeownership Rates by Different Metro Characteristics

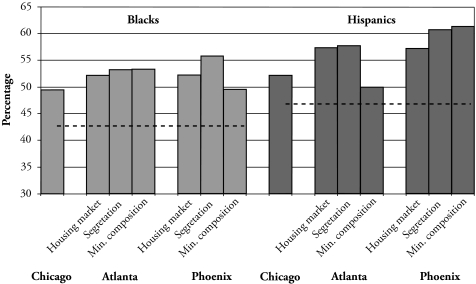

To provide a better intuitive sense for the differential impact of these patterns across metro areas, I next simulate how the average black or Hispanic household’s homeownership probability would change under different contextual circumstances. So as not to confound metro variation in individual- and household-level characteristics with metro variation in housing context, I use the national median to obtain values for the “average” black and Hispanic households. I begin with Chicago, a city that represents a fairly unfavorable housing stock (it is expensive and has a relatively smaller share of new and owner-occupied housing), a high level of segregation, and an established slow-growth base for blacks and Hispanics. I next simulate how homeownership probabilities would change if Chicago had the same housing stock, segregation, and minority composition as Atlanta and Phoenix. Atlanta represents a more affordable and owner-occupied housing market than Chicago, an intermediate level of segregation for both blacks and Hispanics, and is an established growing metro area for blacks and a new destination for Hispanics. Phoenix also has a relatively favorable housing market, but it is characterized by a low level of segregation for both blacks and Hispanics and is a new destination for blacks and an established and growing area for Hispanics.

Figure 2 shows that for the average black household, the probability of homeownership in Chicago is 49%. Applying to Chicago the same housing stock characteristics as Atlanta raises predicted homeownership probability by nearly 4 percentage points to just over 52%. Holding housing prices and all else constant, if Chicago had a more moderate level of segregation like Atlanta, the predicted homeownership probability of the average black household would rise further still to roughly 54%. If Chicago were also experiencing more rapid growth in its black population, like Atlanta, the homeownership probability would not change appreciably.

Figure 2.

Simulation of Predicted Homeownership Probabilities Across Metro Areas

Comparing Chicago with Phoenix shows that if the average black household faced the same housing stock characteristics in Chicago as in Phoenix, their predicted homeownership would rise considerably, as in the simulation for Atlanta, to 52%. If Chicago had the same low level of black concentration as Phoenix, predicted black homeownership would rise nearly 4 additional percentage points, to 56%—nearly as big an increase as resulted from imposing a more affordable housing market. However, if Chicago had the same housing stock and low level of segregation as Phoenix and the small black base of Phoenix, predicted homeownership would fall dramatically to 49%. Thus, overall, the average black household would have almost identical homeownership probabilities in Chicago and Phoenix, in spite of the fact that Phoenix is much more affordable and has less than half the level of residential segregation as Chicago.

For Hispanics, the pattern of effects is remarkably similar, though reversed. The average Hispanic household would have a predicted homeownership propensity that was 6 percentage points higher, 58% relative to 52%, in a housing market similar to that of Atlanta compared with Chicago. If Chicago also had intermediate segregation like Atlanta, the average Hispanic household would enjoy a small additional gain in predicted homeownership. However, if Chicago were a new destination for Hispanics and had a small Hispanic base, the predicted homeownership would drop precipitously to 50%. Similar to blacks in Phoenix, the average Hispanic household living in Atlanta has lower odds of homeownership than in Chicago, in spite of the more affordable housing market and lower level of segregation.

The Hispanic pattern in Phoenix follows that of blacks in Atlanta. If Chicago had Phoenix’s affordable housing, Hispanic predicted homeownership would be more than 5 percentage points higher (57%). If Chicago had Phoenix’s low level of Hispanic concentration, the predicted homeownership would rise another 4 percentage points to 61%. Finally, if Chicago were established and growing instead of established and slow growing, it would not appreciably change predicted homeownership.

CONCLUSIONS

This article contributes to the literature on the impact of context on minority well-being by formulating and testing a theoretical model of minority homeownership that integrates three metropolitan-level characteristics that have received disparate treatment in prior studies: housing stock, residential segregation, and minority composition. In addition, I investigate the implications of recent trends in minority population redistribution within the United States by formulating a measure of minority composition that takes into account the size and growth of minority groups. Finally, I explicitly compare blacks and Hispanics to investigate the extent to which metropolitan contextual forces similarly affect both groups.

Overall, results show that the three mechanisms exert independent effects on minority homeownership that are remarkably similar for blacks and Hispanics. Metropolitan housing stock conditions, such as higher property values and lower share of owner-occupied and new housing, inhibit access to homeownership among blacks and Hispanics. Moreover, models assessing racial and ethnic disparities with whites show that these detrimental effects are significantly stronger among minorities. Both blacks and Hispanics suffer greater constraints on homeownership in more expensive markets and reap fewer benefits from a greater availability of owner-occupied units than their white counterparts. Thus, while the overrepresentation of minorities in less favorable housing markets is an important contributor to homeownership disparities by race and Hispanic origin, the fact that these adverse effects are stronger among minorities supports a racial stratification perspective on homeownership inequality and is at least suggestive of differential treatment in such markets.

The previous literature was ambiguous as to whether residential segregation exerts a direct influence on minority homeownership over and above its association with housing stock and minority composition, especially among Hispanics. The results presented here show that when the different contextual forces are considered in an integrated framework, residential segregation has a clearly negative impact on minority homeownership. For both backs and Hispanics, the degree of relative residential concentration is inversely related to homeownership propensities. At the same time, models assessing the impact of relative concentration on disparities with whites show positive effects on white homeownership, indicating that lower homeownership propensities are not a general characteristic of highly segregated cities but rather that segregation affects minorities in particular. The extent to which there are economic benefits to the dominant group from constrained residential opportunities among minorities requires further examination. Similarly, the finding that residential segregation influences homeownership independent of its association with minority composition and housing conditions highlights the need to more clearly separate the three in subsequent research.

Finally, a central aim of this study was to investigate the relationship between minority composition and homeownership, especially in light of recent minority population redistribution within the United States. Positive spillover effects of a large coethnic community on socioeconomic outcomes has long been hypothesized among Hispanics, especially immigrants, but has received considerably less attention in the literature on blacks. As before, results are remarkably similar for both blacks and Hispanics. For members of both groups, residents of cities that lack a sizable coethnic base are substantially less likely than their counterparts in other areas to be homeowners. Interestingly, while initial models showed that cities with an established and growing minority base also averaged higher minority homeownership than slower-growing established areas, the effect was a function of the lower housing values, higher share of new housing, and lower segregation in those areas. Thus, the key contributor to minority homeownership is the presence of a sizeable coethnic base, and not how fast the base is expanding.

The fact that there is little overlap between the black and Hispanic typologies suggests that the association between coethnic population and homeownership is not driven by unobserved metro characteristics. New destinations for Hispanics tend to be established areas for blacks and vice versa. As a result, the effect of residing in cities like Phoenix or Atlanta on minority homeownership is dramatically different for blacks and Hispanics. Moreover, results are maintained when I assess the impact of context on housing disparities with whites, reinforcing the unique effect of contextual processes on minority homeownership.

I do find, however, that metro areas with lower than average minority representation are less amenable to homeownership for both blacks and whites and that the opposite holds for the Hispanic case. This suggests that to a certain extent the typology also captures broader contextual conditions. Nevertheless, the fact that the negative association between low black representation and homeownership is stronger for blacks than for whites supports the importance of the ethnic community even in areas generally not propitious for home-ownership. At the same time, even though areas with few Hispanics are generally more amenable to homeownership, the effect is weaker for Hispanics. When taken together, these findings bolster confidence in the importance of coethnic communities and segregation to minority homeownership.

Thus, answering the question of what recent population redistribution portends for minority homeownership demands paying close attention to the context of receiving communities. Although favorable housing conditions (particularly lower prices and a greater share of owner-occupied units) common in growing areas of the country bode well for homeownership overall, among minorities, the effects will be mediated by the size of the coethnic community. For blacks, the “new” great migration to the South, which overwhelmingly involves residence in metro areas with an established coethnic base, is likely to improve prospects for homeownership. For Hispanics, in contrast, much of the growth is in new destinations where the lack of an established coethnic community is likely to undermine homeownership. Thus, in the near term, population trends hold more promise for raising black than Hispanic homeownership.

Appendix Table A1.

Hierarchical Logit Analysis of Minority Homeownership: Individual- and Household-Level Effects (standard errors in parenthesis)

| Variable | For Table 2, Model 1 |

For Tables 3 and 4, Model 1 |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blacks | Hispanics | Blacks | Hispanics | |||||

| Intercept | −4.990 | (0.076) | −5.204 | (0.089) | −3.719 | (0.319) | −3.843 | (0.331) |

| Demographic/Family Structure Characteristics | ||||||||

| Black/Hispanic | –– | –– | −0.789 | (0.018) | −0.376 | (0.026) | ||

| Age | 0.063 | (0.000) | 0.045 | (0.001) | 0.065 | (0.000) | 0.057 | (0.000) |

| Male | 0.235 | (0.010) | 0.257 | (0.012) | 0.178 | (0.007) | 0.179 | (0.008) |

| Marital status (ref. = married) | ||||||||

| Widowed | −0.476 | (0.020) | −0.204 | (0.029) | −0.556 | (0.016) | −0.371 | (0.020) |

| Divorced | −0.906 | (0.011) | −0.765 | (0.014) | −1.047 | (0.008) | −0.981 | (0.009) |

| Single | −1.054 | (0.012) | −0.836 | (0.014) | −1.155 | (0.009) | −1.043 | (0.010) |

| Children under 18 | 0.256 | (0.009) | 0.401 | (0.011) | 0.358 | (0.007) | 0.442 | (0.007) |

| Human Capital and Socioeconomic Status Characteristics | ||||||||

| Education (ref. = 9th grade or less) | ||||||||

| 10th–12th grade | 0.382 | (0.019) | 0.221 | (0.012) | 0.418 | (0.016) | 0.306 | (0.011) |

| 12th grade or more | 0.796 | (0.020) | 0.557 | (0.014) | 0.755 | (0.016) | 0.589 | (0.011) |

| Household income (log) | 0.223 | (0.003) | 0.321 | (0.005) | 0.247 | (0.003) | 0.307 | (0.003) |

| Occupation (ref. = professional) | ||||||||

| Sales | −0.259 | (0.022) | −0.207 | (0.025) | −0.142 | (0.014) | −0.112 | (0.015) |

| Clerical | −0.366 | (0.013) | −0.289 | (0.017) | −0.327 | (0.010) | −0.273 | (0.011) |

| Operatives | −0.259 | (0.015) | −0.260 | (0.016) | −0.249 | (0.011) | −0.250 | (0.011) |

| Craft | −0.215 | (0.017) | −0.200 | (0.016) | −0.166 | (0.011) | −0.163 | (0.011) |

| Services | −0.506 | (0.013) | −0.508 | (0.016) | −0.474 | (0.010) | −0.476 | (0.011) |

| Labor | −0.648 | (0.103) | −0.694 | (0.035) | −0.558 | (0.072) | −0.640 | (0.031) |

| Not working | −0.611 | (0.015) | −0.498 | (0.017) | −0.513 | (0.011) | −0.437 | (0.012) |

| Self-employed | 0.259 | (0.020) | 0.319 | (0.017) | 0.320 | (0.012) | 0.347 | (0.012) |

| Work disability | −0.118 | (0.010) | −0.083 | (0.011) | −0.184 | (0.008) | −0.158 | (0.009) |

| Immigration Characteristics | ||||||||

| Foreign-born | −0.859 | (0.030) | −1.047 | (0.016) | −1.019 | (0.022) | −1.070 | (0.014) |

| Years in United States | 0.045 | (0.001) | 0.042 | (0.001) | 0.041 | (0.001) | 0.038 | (0.001) |

| National origin (ref. = Mexican) | ||||||||

| Puerto Rican | –– | −0.247 | (0.019) | −0.278 | (0.019) | |||

| Cuban | –– | 0.141 | (0.027) | 0.127 | (0.026) | |||

| Other | –– | −0.062 | (0.012) | −0.077 | (0.012) | |||

| Nonwhite | –– | −0.093 | (0.009) | −0.078 | (0.009) | |||

Note: All coefficients are statistically significant at p < .05.

Footnotes

Although the share of all black (Hispanic) households who owned their homes rose from roughly 44% (42%) to 47% (46%) between 1990 and 2000, the increase was even greater for whites, whose rate of homeownership rose from 68% to over 74% during the period.

See Ruggles et al. (2008) for the data source. The sample size for whites was reduced to 1% to facilitate estimation. Metropolitan areas include both free-standing metropolitan statistical areas (MSAs), which are generally surrounded by nonmetropolitan territory and therefore are not integrated with other metropolitan areas; and primary metropolitan statistical areas (PMSAs), which are the same as MSAs except that they are near, and economically linked to, other PMSAs, to form larger consolidated metropolitan statistical areas (CMSAs). For further information, see variable description at the IPUMS Project at http://usa.ipums.org.

This age range minimizes potential disjuncture between current conditions and conditions at time of home purchase. A wide range of age ranges was considered, including 18–65, 20–30, and 30–40. Models run with different age restrictions produced the same substantive findings as those presented in this article.

I also performed the analyses by using only the 155 metropolitan areas with sizeable black and Hispanic populations. Results were substantively similar to those reported in the text.

Because a dummy variable for nativity is included simultaneously with years in the United States, coefficients for length of U.S. residence indicate the effect for the foreign-born population (Krivo 1995).

For a discussion of the limitation of RCO, see Egan, Anderton, and Weber (1998) and Massey and Denton (1998). The data can be found at http://www.census.gov:80/hhes/www/housing/housing_patterns/housing_patterns.html. To assess the extent to which our findings were sensitive to the measure of segregation, I also modeled DEL, ACO, relative and absolute centralization, the index of dissimilarity, and the Gini coefficient. Overall, the effect of concentration and centralization are very similar to those reported in this article, with linear specifications of relative and absolute measures registering a significant negative effect on minority but not white homeownership. For dissimilarity and the Gini coefficient, however, a linear specification was not significantly related to black homeownership. However, when segregation was measured through a dummy variable distinguishing the 25% most segregated metro areas, segregation was negatively associated with minority homeownership, as predicted. Thus, overall results indicate robustness in the effect.

Additional calculations reveal that if we use the degree of absolute concentration of the black population, the positive effect on whites is not statistically significant. The negative effect of segregation on black home-ownership, however, remains significant.

Additional tabulations (not reported) reveal that this pattern holds true whether relative or absolute measures of residential concentration are used.

REFERENCES

- Alba R, Logan J. “Assimilation and Stratification in the Homeownership Patterns of Racial and Ethnic Groups”. International Migration Review. 1992;26:1314–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi S, Farley R, Spain D. “Racial Inequalities in Housing: An Examination of Recent Trends”. Demography. 1982;19:37–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borjas GJ. “Homeownership in the Immigration Population”. Journal of Urban Economics. 2002;52:448–76. [Google Scholar]

- Borjas GJ. “The Labor Demand Curve is Downward Sloping: Reexamining the Impact of Immigration on the Labor Market”. Quarterly Journal of Economics. 2003;118:1335–74. [Google Scholar]

- Bostic R, Surette B. “Have the Doors Opened Wider? Trends in Homeownership Rates by Race and Income”. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics. 2001;23:411–34. [Google Scholar]

- Card D. “Is the New Immigration Really So Bad?”. The Economic Journal. 2005;115:300–23. [Google Scholar]

- Charles K, Hurst E. “The Transition to Homeownership and the Black-White Wealth Gap”. Review of Economics and Statistics. 2002;84:281–97. [Google Scholar]

- Clark WA, Deurloo MC, Dieleman FM. “Tenure Changes in the Context of MicroLevel Family and Macro-Level Economic Shifts”. Urban Studies. 1994;31:137–54. [Google Scholar]

- Conley D. Being Black, Living in the Red: Race, Wealth, and Social Policy in America. Berkeley: University of California Press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Cutler DM, Glaeser EL, Vigdor J. “When are Ghettos Bad? Lessons From Immigrant Segregation in the United States” NBER Working Paper No 13082. National Bureau of Economic Research; Cambridge, MA: 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Dawkins C. “Racial Gaps in the Transition to First-Time Homeownership: The Role of Residential Location”. Journal of Urban Economics. 2005;58:537–54. [Google Scholar]

- Deng Y, Ross S, Wachter S. “Racial Differences in Homeownership: The Effect of Residential Location”. Regional Science and Urban Economics. 2002;33:517–56. [Google Scholar]

- Egan K, Anderton D, Weber E. “Relative Spatial Concentration Among Minorities: Addressing Errors in Measurement”. Social Forces. 1998;76:1115–21. [Google Scholar]

- Farley R, Frey W. “Changes in the Segregation of Whites From Blacks During the 1980s: Small Steps Toward a More Integrated Society”. American Sociological Review. 1994;59:23–45. [Google Scholar]

- Flippen CA. “Racial and Ethnic Inequality in Homeownership and Housing Equity”. The Sociological Quarterly. 2001a;42:121–49. [Google Scholar]

- Flippen CA. “Residential Segregation and Minority Homeownership”. Social Science Research. 2001b;30:337–62. [Google Scholar]

- Flippen CA. “Unequal Returns to Housing Investments? A Study of Real Housing Appreciation Among Black, White, and Hispanic Households”. Social Forces. 2004;82:1527–55. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman L. “Black Homeownership: The Role of Temporal Changes and Residential Segregation at the End of the 20th Century”. Social Science Quarterly. 2005;86:403–26. [Google Scholar]

- Freeman L, Hamilton D. “The Changing Determinants of Inter-racial Home Ownership Disparities: New York City in the 1990s”. Housing Studies. 2004;19:301–23. [Google Scholar]

- Frey W. The Brookings Institute; Washington DC: 2004. “The New Great Migration: Black Americans’ Return to the South: 1965–2000”. Living Cities Census Series. [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel S, Painter G. “Pathways to Homeownership: An Analysis of the Residential Location and Homeownership Choices of Black Households in Los Angeles”. Journal of Real Estate Finance and Economics. 2003;27:87–109. [Google Scholar]

- Gyourko J, Linneman P. “The Changing Influence of Education, Income, Family Structure, and Race on Homeownership by Age Over Time”. Journal of Housing Research. 1997;8:1–25. [Google Scholar]

- Harris D. “Why Are Whites and Blacks Averse to Black Neighbors?”. Social Science Research. 2001;30:100–16. [Google Scholar]