Abstract

Purpose

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is second leading cause of cancer-associated deaths, suggesting that more efforts are needed to prevent/control CRC. Herein, for the first time, we investigated in vivo silibinin efficacy against azoxymethane (AOM)-induced colon tumorigenesis in A/J mice.

Experimental Design

Five-week old male mice were gavaged with vehicle or silibinin (250 and 750 mg/kg) for 25 weeks starting 2 weeks before initiation with AOM (pre-treatment regime) or for 16 weeks starting 2 weeks after last AOM injection (post-treatment regime). Mice were then sacrificed and colon tissues were examined for tumor multiplicity and size, and molecular markers for proliferation, apoptosis, inflammation and angiogenesis.

Results

Silibinin feeding showed a dose-dependent decrease in AOM-induced colon tumorigenesis with stronger efficacy in pre- versus post-treatment regimen. Mechanistic studies in tissue samples showed that silibinin inhibits cell proliferation as evident by a decrease (P<0.001) in PCNA and cyclin D1, and increased Cip1/p21 levels. Silibinin also decreased (P<0.001) the levels of iNOS, COX-2 and VEGF suggesting its anti-inflammatory and anti-angiogenic potential in this model. Further, silibinin increased cleaved caspase-3 and PARP levels, indicating its apoptotic effect. In other studies, colonic mucosa and tumors expressed high levels of β-catenin, IGF-1Rβ, pGSK-3β and pAkt proteins in AOM-treated mice which were strongly lowered (P<0.001) by silibinin treatment. Also, AOM reduced IGFBP-3 protein level which was enhanced by silibinin.

Conclusions

Silibinin targets β-catenin and IGF-1Rβ pathways for its chemopreventive efficacy against AOM-induced colon carcinogenesis in A/J mice. Overall, these results support translational potential of silibinin in CRC chemoprevention.

Keywords: colorectal cancer, silibinin, inflammation, angiogenesis, apoptosis

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the second most common cause of cancer-related deaths, and third most common cause of cancer with 146,970 new cases and 49,920 deaths predicted in the United States for 2009 (1). Despite the availability of chemotherapy, surgery and radiation which is limited for advanced stages of CRC, there is a high recurrence rate with an overall 5 years survival of about 55% (2). Colon carcinogenesis offers a huge window period of 10-15 years which could be coupled with various screening procedures for the identification of the preneoplastic lesions, making this malignancy suitable for implementation of chemoprevention strategies (3). The azoxymethane (AOM)-induced colon carcinogenesis is the most-frequently employed animal model for an agent’ efficacy study against colon cancer (4). After metabolic activation, AOM is converted to ultimate carcinogen methylazoxymethanol (MAM) which binds to DNA causing mutations, including K-ras and CTNNB1 that codes for β-catenin (5, 6). The advantages of using AOM model for chemoprevention studies include the distinction of promotional and protective effects of experimental diets on tumor growth, similarity to humans in progression of ACF to polyps and ultimately to carcinomas, and K-ras mutation in human CRC which is present in nearly 60% of AOM-induced colon tumors (6). Most solid tumors including colorectal tumors are characterized by increased cell proliferation, ablation of apoptosis, enhanced inflammation and tumor angiogenesis which lead to poor prognosis (7-9). APC and β-catenin genes are considered critical in CRC development as alterations in these genes aid in the process of carcinogenesis in both humans and preclinical models (10). Colonic adenomas and adenocarcinomas harbor high expression of β-catenin in the cytoplasm and nucleus (11). Colonic tumors also express high levels of IGF-1Rβ, pGSK-3β and low level of IGFBP-3 which lead to malignant potential of tumor cells (12). Taken together, above discussion suggests that the agents, such as silibinin, which target critical molecular pathways involving β-catenin and IGF-1Rβ and associated proliferation, apoptosis, inflammation and angiogenesis, could be effective chemopreventive agents against colon tumorigenesis.

Various epidemiological studies and animal experiments have indicated that polyphenolic compounds present in vegetables, fruits and their constituents have profound beneficial effects in controlling CRC (13, 14). One of the chemopreventive agents extensively investigated in recent years is silibinin, a flavanolignan isolated from Silybum marianum. Silibinin has shown potent anticancer activity against various epithelial cancers both in vivo and in vitro (15-19). The pharmacological significance of silibinin includes its non-toxicity even at higher doses and human acceptance with known hepatoprotective activity (20). Previous studies do suggest an anticancer potential of silibinin (21, 22); however, the in vivo colon cancer chemopreventive efficacy and associated molecular alterations by long-term silibinin administration in AOM-A/J mouse model are not known. Accordingly, here we examined in vivo efficacy of long-term feeding of silibinin against AOM-induced colon tumorigenesis in A/J mouse model and associated molecular changes. Our results clearly show the chemopreventive efficacy of silibinin against colon tumorigenesis and its effect on proliferation (PCNA, Cyclin D1 and Cip1/p21), apoptosis (cleaved caspase-3 and PARP), inflammation (iNOS and COX-2), angiogenesis (VEGF), and IGF-1Rβ, IGFBP-3, β-Catenin, pGSK-3β and pAkt.

Materials and Methods

Animals and treatments

Male A/J mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME), and experiments were done with an approved protocol by IACUC. Silibinin, carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) and AOM were from Sigma (St Louis, MO). Silibinin was suspended in 0.5% (w/v) CMC (vehicle) and was gavaged orally, and AOM was dissolved in saline. Animals, maintained under standard conditions with free access to water and food (AIN-76 diet), were divided in to 7 groups, and as shown in Fig. 1A, treated as: (1) control group (n=15), 0.5% (w/v) CMC (vehicle); (2) positive group (n=25), injected with 5 mg/kg dose of AOM i.p. once a week for 6 weeks, (3) SB-250 (n=25), 250 mg/kg/d dose of silibinin in CMC initiated 2 weeks prior to AOM and continued for 25 weeks; (4) SB-750 (n=25), 750 mg/kg/d dose of silibinin in CMC initiated 2 weeks prior to AOM and continued for 25 weeks; (5) SB-250 (n=25), 250 mg/kg/d dose of silibinin in CMC initiated 2 weeks after last AOM and continued till 30 weeks of age; (6) SB-750 (n=25), 750 mg/kg/d dose of silibinin in CMC initiated 2 weeks after last AOM and continued till 30 weeks of age; (7) SB-750 (n=15), 750 mg/kg/d dose of silibinin in CMC till 30 weeks of age. All silibinin treatments were 5 days/week throughout experiment. Body weight and diet consumption were recorded weekly. At 30 weeks of age, mice were sacrificed, entire colon excised starting from ileocecal junction to anal verge and cut open longitudinally along main axis and gently flushed with ice-cold PBS, divided in to three equal sections (proximal, middle and distal), tumors counted, tumor diameters measured with digital calipers under dissecting microscope and fixed flat in formalin, and embedded in paraffin for immunohistochemical (IHC) studies or frozen in liquid nitrogen.

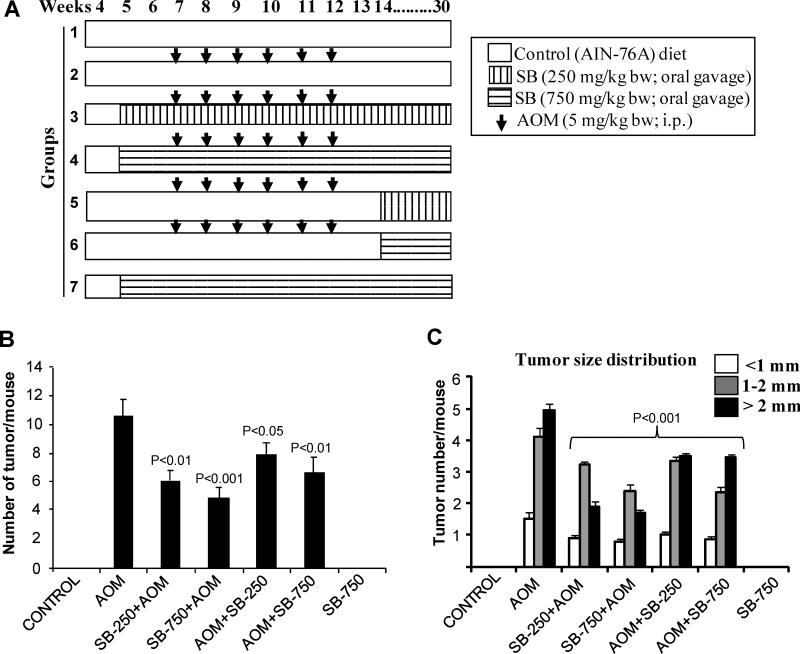

Figure 1.

Silibinin prevents AOM-induced colon tumorigenesis in A/J mice. (A) Experimental design for AOM-induced colon tumorigenesis in male A/J mice and efficacy studies with silibinin, as detailed in Methods. (B) Number of colonic tumors per mouse and (C) tumor size distribution in each group at the end of the study. Bars shown in each case are mean ± SEM.

IHC analyses

Paraffin-embedded sections (5 μm) were subjected to antigen retrieval and blocking of endogenous peroxidase activity (21). Sections were incubated with mouse monoclonal anti-PCNA (1:250 dilutions; Dako), rabbit polyclonal anti-cyclin D1 (1:100 dilutions; Neomarkers), rabbit polyclonal anti-Cip1/p21 (1:100 dilutions; Santa Cruz), rabbit polyclonal anti-VEGF (1:100 dilutions; Neomarkers), rabbit polyclonal anti-iNOS (1:100 dilutions; Abcam), goat polyclonal anti-COX-2 (1:50 dilutions; Santa Cruz), rabbit polyclonal anti-IGF-1Rβ (1:100 dilutions; Cell Signaling), rabbit polyclonal anti-IGFBP-3 (1:100 dilutions; Santa Cruz), rabbit polyclonal anti-p-GSK-3β (1:100 dilutions; Cell Signaling), rabbit polyclonal anti-β-catenin (1:100 dilutions; Santa Cruz), rabbit polyclonal anti phospho-Akt (1:100 dilutions; Cell Signaling), or rabbit polyclonal anti-cleaved caspase-3 (1:75 dilutions; Cell Signaling) antibody. In all IHC, negative staining controls were used where sections were incubated with N-Universal Negative Control mouse or rabbit antibody (DAKO) under identical conditions. Sections were then incubated with biotinylated appropriate secondary antibody for 1 hr at room temperature followed by 30 min incubation with conjugated horseradish peroxidase (HRP)-streptavidin (Invitrogen) and then incubated with DAB (Vector Laboratories, Inc.) working solution at room temperature followed by counterstaining with diluted Harris hematoxylin (Sigma) and mounted. Microscopic IHC analyses were performed using Zeiss Axioscop 2 microscope (Carl Zeiss); photomicrographs captured by Carl Zeiss AxioCam MrC5 camera with Axiovision Rel 4.5 software. Positive cells for various IHC stained molecules were quantified by counting brown-stained cells among total number of cells at 5 randomly selected fields at x400 magnification. In other cases, immunoreactivity (represented by intensity of brown staining) was scored as 0 (no staining), +1 (very weak), +2 (weak), +3 (moderate) and +4 (strong). Representative images of IHC staining (x400) of colonic adenoma region are shown in each case and quantification data shown includes both colonic mucosa and tumor IHC staining.

Western blot analysis

Tissue lysates of colonic mucosa (scrapped with tumors) from AOM alone- and silibinin + AOM-treated mice in pre-treatment regime were analyzed by immunoblotting as previously described (23, 24 ). Anti-IGF-1Rβ, anti-pIGF-1Rβ (Tyr1316), anti-Akt, anti-GSK-3β and anti-cleaved-PARP antibodies were from Cell Signaling; anti-β-actin was from Sigma, and other antibodies were those used in IHC studies as mentioned above. Densitometry analyses of bands were adjusted with β-actin as loading control.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using Sigma Stat software version 2.03 (Jandel Scientific) for statistical significance of difference between different groups. Significance was determined by one-way analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA) followed by Tukey test for multiple comparisons. P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Silibinin prevents AOM-induced colon tumorigenesis in mice

A well established long-term protocol was used to determine silibinin efficacy in inhibiting AOM-induced colon tumor formation. Mice in all groups were regularly monitored for any silibinin-associated adverse effects. In terms of body weight gain profiles over the course of study, silibinin did not show any considerable changes among various groups (data not shown). During necropsy, no pathological alterations were found in any organs including liver, lung and kidney, by gross observation in A/J mice in various groups. Regarding colon tumorigenesis, AOM-treated group showed 11 ± 1.1 colonic tumors/mouse which was reduced to 6 ± 0.8 and 5 ± 0.7 tumors by 250 and 750 mg/kg doses of silibinin started before AOM (Fig. 1B), accounting for 46% (P<0.01) and 55% (P<0.001) decrease in tumor multiplicity, respectively. Lower and higher doses of silibinin treatments in post-AOM protocol showed similar trend in decreasing number of colonic tumors which were 8 ± 0.9 (P<0.05) and 7 ± 1 (P<0.01) per mouse, respectively (Fig. 1B). Also, in terms of tumor size distribution, silibinin pre-treatment showed much stronger efficacy accounting for 42-50%, 21-42% and 62-66% decrease in number of <1, 1-2 and >2 mm size colon tumors, respectively, compared to AOM-alone controls (Fig. 1C). Mice in control or only silibinin-treated group did not show any colonic tumors. Together, these results show the preventive effect of silibinin on AOM-induced colonic tumor multiplicity with strongest efficacy in reducing the number of biggest size tumors (>2 mm) in A/J mice without any apparent toxicity, and suggest that silibinin efficacy is associated with its treatment protocols as well as the duration of treatment with respect to AOM treatment.

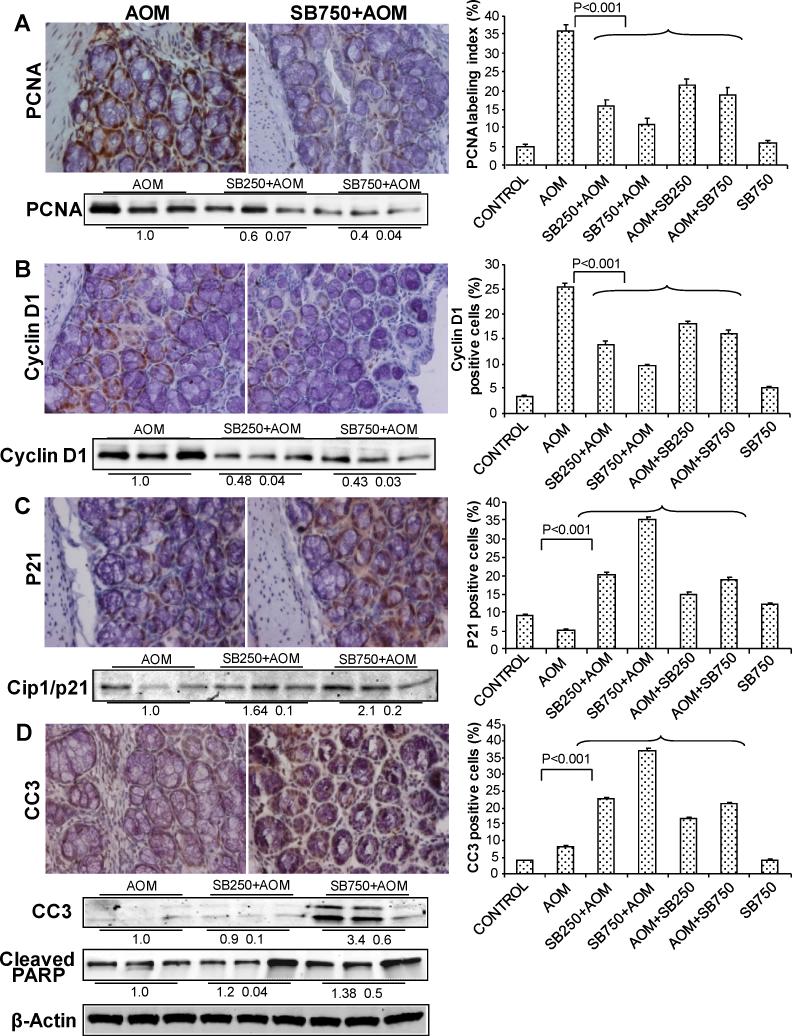

Silibinin inhibits cell proliferation and induces apoptosis

In vivo anti-proliferative and apoptosis inducing effects of silibinin were examined on AOM-induced colonic mucosa and tumors by analyzing the levels of molecular markers including PCNA, cyclin D1 and Cip1/p21 to relate with tumor cell proliferation and cleaved caspase-3 and PARP for apoptosis by IHC and/or immunoblotting. Quantification of PCNA-positive cells showed that 250 and 750 mg/kg/d doses of silibinin started before AOM result in 56% and 69% (P<0.001) decrease in proliferation index compared to AOM alone; a similar trend in silibinin inhibitory effect on cell proliferation was also observed in post-treatment regimes (Fig. 2A). Cyclin D1 overexpression is correlated with enhanced cell proliferation (21) and therefore was also studied by us. Similar to PCNA, silibinin pre-treatments at 250 and 750 mg/kg/d doses reduced cyclin D1-positive cells by 46% and 63% (P<0.001), respectively, and also showed a similar but comparatively lesser effect in post-treatment regimen (Fig. 2B). Cip1/p21 plays a significant role in cell cycle arrest by binding with and inhibiting PCNA activity (25). Quantification of Cip1/p21-positive cells showed 5±0.3% cells in AOM group versus 35±0.7% cells (7-fold increase, P<0.001) in 750 mg/kg/d dose of silibinin-treated group and a similar trend in Cip1/p21 induction by silibinin in other treatment protocols (Fig. 2C). IHC results shown in Fig. 2A-C were further supported by immunoblot analysis of three randomly selected samples from three individual mice in AOM and pre-silibinin plus AOM groups, which showed similar silibinin efficacy patterns. IHC analysis for apoptotic cells showed an increase in number of cleaved caspase-3-positive cells in silibinin-treated groups as compared to AOM group. Quantification of cleaved caspase-3-positive cells showed an increase in apoptotic index by up to ~4.6-fold (P<0.001) at higher dose of silibinin (Fig. 2D). In vivo apoptotic activity of silibinin was also supported by strong levels of cleaved caspase 3 and PARP in silibinin-fed versus AOM alone samples in immunoblot analyses (Fig. 2D). Together, these results indicate both antiproliferative and proapoptotic effects and associated molecular alterations by silibinin, and their possible involvement in overall preventive efficacy of silibinin against colon tumorigenesis.

Figure 2.

Silibinin inhibits cell proliferation and induces apoptosis in its chemopreventive efficacy against AOM-induced colon tumorigenesis in A/J mice. At study end, colon samples were collected and subjected to IHC analysis and quantification as described in Methods. Representative images of IHC staining (x400) of colonic adenoma region are shown in each case and quantification data shown includes both colonic mucosa and tumor IHC staining for (A) PCNA, (B) Cyclin D1, (C) Cip1/p21 and (D) cleaved caspase (CC)-3 positive cells. Bars shown in each case are mean ± SEM. Colonic mucosa with tumor/s from indicated groups were also analyzed by immunoblotting for (A) PCNA, (B) Cyclin D1, (C) Cip1/p21 and (D) CC3 and cleaved–PARP levels. Densitometry values shown for each group are mean ± SEM (n=3) after adjustment with β-actin as loading control. Sb, silibinin.

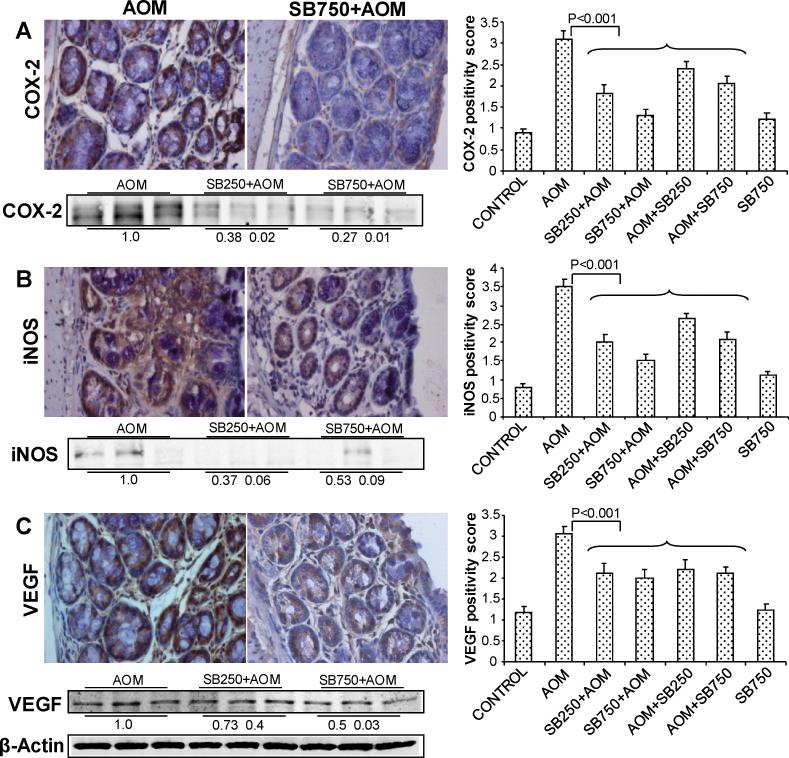

Silibinin decreases the levels of inflammatory and angiogenic molecules

The roles of COX-2 and iNOS as inflammatory molecules are well documented in both colon inflammation and carcinogenesis; both molecules are modulated by chemopreventive and anti-inflammatory agents (26, 27). Accordingly, silibinin effect on COX-2 expression was next examined by IHC where AOM-group samples showed marked expression for COX-2 that decreased substantially by silibinin treatments (Fig. 3A). Quantification of COX-2 staining based on intensity of immunoreactivity (0-4 scale) showed 3.1±0.04 positivity score in AOM-group versus 1.8±0.04 and 1.3±0.03 in low and high doses silibinin-pretreated groups accounting for 42 and 58% (p<0.001) decrease compared to AOM group, respectively (Fig. 3A). Silibinin post-treatments also showed significant decrease (23-39%, P<0.001) in COX 2-positivity (Fig. 3A). We also observed strong immunoreactivity for iNOS in AOM-induced mice, which decreased strongly in silibinin-treated groups (Fig 3B). Quantification of iNOS immunostaining showed a positivity score of 3.5±0.05 in AOM alone versus 1.8±0.05 and 1.3±0.04 in low and high doses silibinin-pretreated groups accounting for 48 and 63% (P<0.001) decrease, respectively (Fig. 3B). Silibinin post-treatment showed similar decrease in iNOS positivity scores but to lesser extent.

Figure 3.

Silibinin decreases the levels of inflammatory and angiogenic molecules in its chemopreventive efficacy against AOM-induced colon tumorigenesis in A/J mice. At study end, colon samples were collected and subjected to IHC analysis and quantification as described in Methods. Representative images of IHC staining (x400) of colonic adenoma region are shown in each case and quantification data shown includes both colonic mucosa and tumor IHC staining for (A) COX-2, (B) iNOS and (C) VEGF positivity scores. Bars shown in each case are mean ± SEM. Colonic mucosa with tumor/s from indicated groups were also analyzed by immunoblotting for (A) COX-2, (B) iNOS and (C) VEGF levels. Densitometry values shown for each group are mean ± SEM (n=3) after adjustment with β-actin as loading control. Sb, silibinin.

The role of VEGF in angiogenesis is well documented in literature (28). Based on our results showing that silibinin treatment reduces the number of biggest size tumors most strongly, we next assessed whether VEGF levels are decreased in silibinin-treated groups compared to AOM alone to support its anti-angiogenic activity. Immunostaining for VEGF showed lower immunoreactivity in silibinin-treated groups of mice (Fig. 3C), and quantification of VEGF positivity scores showed ~33% (P<0.001) decrease in high-dose silibinin pretreated-group compared to AOM alone (Fig. 3C). Comparable silibinin effect was observed in all other treatments in decreasing VEGF positivity scores compared to AOM alone (Fig. 3C). IHC results shown in Fig. 3A-C for COX-2, iNOS and VEGF were further supported by immunoblot analysis of three randomly selected samples from three individual mice in AOM and pre-silibinin plus AOM groups, which showed similar silibinin efficacy patterns. Together, these results show the effect of silibinin on two key events of colon carcinogenesis, namely inflammation and angiogenesis, and their possible role in overall chemopreventive efficacy of silibinin against colon tumorigenesis.

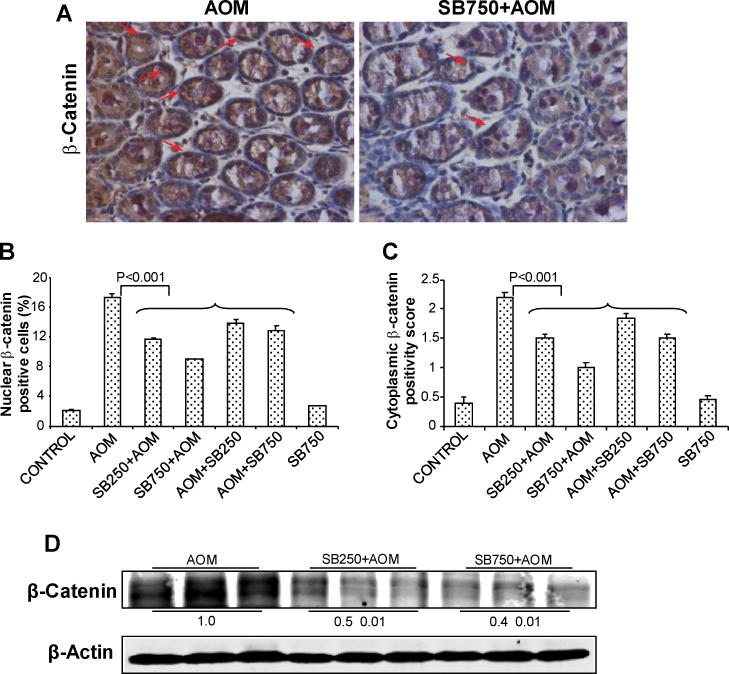

Silibinin decreases the levels of both nuclear and cytoplasmic β-catenin

Alterations in β-catenin pathway due to loss of APC function are implicated in CRC initiation and progression (10, 11). We therefore next assessed silibinin effect on β-catenin levels by both IHC and immunoblotting. AOM alone group exhibited significant expression of β-catenin in both nucleus and cytoplasm; silibinin treatments, however, caused a decrease in β-catenin positive cells (Fig. 4A). Quantification of staining showed that silibinin decreases nuclear β-catenin positive cells by 34-49% (P<0.001) and 21-26% (P<0.001) in pre- and post-AOM protocols compared to AOM alone, respectively (Fig. 4B). Cytoplasmic β-catenin immunoreactivity was scored as an overall intensity of brown staining, and its quantification showed a positivity score of 2.2±0.03 in AOM alone versus 1.0±0.01 in higher silibinin-pretreated group, accounting for 55% reduction (P<0.001); other silibinin treatments also showed a decrease ranging from 18-30% (P<0.001) (Fig. 4C). These IHC results were further supported by immunoblot analysis of three randomly selected samples from three individual mice in AOM and both doses of pre-silibinin plus AOM groups, which showed that silibinin treatment decreases total β-catenin levels by 50-60% (Fig. 4D). Together, these results indicate that β-catenin could be a potential molecular target for the chemopreventive effects of silibinin against colon tumorigenesis.

Figure 4.

Silibinin decreases the levels of both nuclear and cytoplasmic β-catenin in its chemopreventive efficacy against AOM-induced colon tumorigenesis in A/J mice. At study end, colon samples were collected and subjected to IHC analysis and quantification as described in Methods. (A) Representative images of IHC staining (x400) of colonic adenoma region are shown in each case, and quantification data shown includes both colonic mucosa and tumor IHC staining for (B) nuclear β-catenin positive cells and (C) cytoplasmic β-catenin positivity scores. Bars shown in each case are mean ± SEM. (D) Colonic mucosa with tumor/s from indicated groups were also analyzed by immunoblotting for total β-catenin levels. Densitometry values shown for each group are mean ± SEM (n=3) after adjustment with β-actin as loading control. Sb, silibinin.

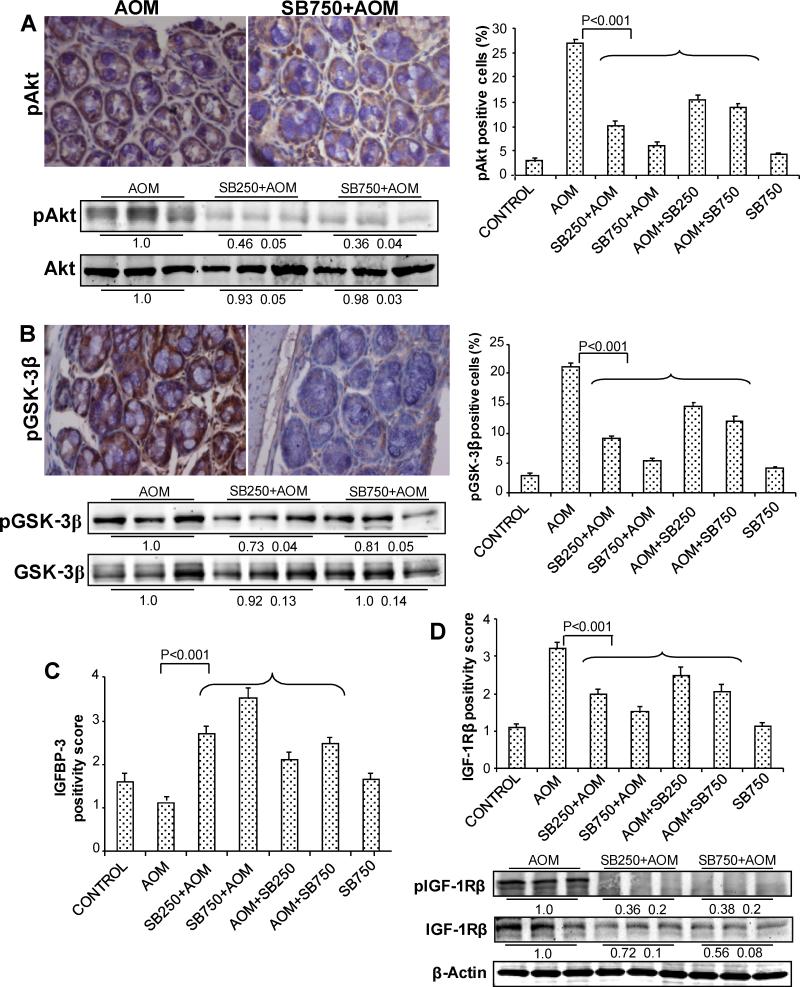

Silibinin decreases the levels of key molecules on IGF1 axis

IGF1-IGF-1R axis plays a critical role in CRC development including its role in proliferation, cell survival and angiogenesis as well as regulation of β-catenin levels (12, 29). Based on our above discussed findings about silibinin efficacy in preventing AOM-induced colon tumorigenesis together with in vivo decrease in proliferation, inflammation and angiogenesis but increased apoptosis and alteration in associated molecular regulators including decreased β-catenin levels in tumor tissues, we also analyzed silibinin effect on pAkt, pGSK-3β, IGFBP-3 and IGF-1Rβ levels. In IHC analysis, AOM-group samples showed very high levels of both pAkt and pGSK-3β which decreased strongly by silibinin treatments (Fig. 5A and 5B). Quantification of pAkt in AOM-group showed 27±0.25% pAkt-positive cells versus 10±0.28 and 6±0.17% in low and high doses silibinin-pretreated groups accounting for 63 and 78% (P<0.001) decrease compared to AOM group, respectively (Fig. 5A). Silibinin post-treatments also showed significant decrease (42-49%, P<0.001) in pAkt-positive cells (Fig. 5A). We also observed strong immunoreactivity for pGSK-3β in AOM alone group, which decreased strongly in silibinin-treated samples (Fig. 5B). Quantification of pGSK-3β-positive cells showed 57 and 74% (P<0.001) decrease in low and high doses silibinin-pretreated groups compared to AOM alone, respectively (Fig. 5B); post-treatment of silibinin showed similar decrease in pGSK-3β-positive cells but to lesser extent (Fig. 5B). IHC results shown in Fig. 5A and 5B for pAkt and pGSK-3β were further supported by immunoblot analysis of three randomly selected samples from three individual mice in AOM and pre-silibinin plus AOM groups, which showed similar silibinin efficacy patterns, without any effect on total Akt and GSK-3β levels. In other studies, IHC staining for IGFBP-3 positivity score showed lower levels in AOM-alone group which increased strongly (~2.5-3.2-fold, P<0.001) at least in silibinin-pretreated groups (Fig. 5C). Conversely, IGF-1Rβ-positivity score showed high levels in AOM alone group that decreased dose-dependently (by 37-52% and 22-38%, P<0.001) in both pre- and post-silibinin treatment groups, respectively (Fig. 5D). This was further confirmed by the immunoblot analysis, in which AOM alone group showed high levels of both phospho- as well as total IGF-1Rβ. These AOM-induced levels of phospho- and total IGF-1Rβ were strongly decreased by silibinin treatments (Fig. 5D). Together, these results show strong inhibitory effects of silibinin on IGF1 axis in AOM-induced mouse colon tumorigenesis, and its possible role in overall chemopreventive efficacy of silibinin.

Figure 5.

Silibinin decreases the levels of key molecules on IGF1 axis in its chemopreventive efficacy against AOM-induced colon tumorigenesis in A/J mice. At study end, colon samples were collected and subjected to IHC analysis and quantification as described in Methods. Representative images of IHC staining (x400) of colonic adenoma region are shown in each case and quantification data shown includes both colonic mucosa and tumor IHC staining for (A) pAkt, (B) pGSK-3β, (C) IGFBP-3 and (D) IGF-1Rβ positive cells or positivity scores. Bars shown in each case are mean ± SEM. Colonic mucosa with tumor/s from indicated groups were also analyzed by immunoblotting for (A) pAkt and total Akt, (B) pGSK-3β and total GSK-3β and (D) phospho-IGF-1Rβ (Tyr1316) and total IGF-1Rβ levels. Densitometry values shown for each group are mean ± SEM (n=3) after adjustment with β-actin as loading control. Sb, silibinin.

Discussion

Present study, for the first time, provides the scientific evidence for the preventive effects of long-term silibinin treatment on AOM-induced colon tumorigenesis in A/J mice. This is an excellent and well-studied pre-clinical model for CRC chemoprevention efficacy studies and also known in literature for its relevance with respect to clinical, histopathological and molecular features of human CRC (30, 31). Administration of silibinin significantly prevented colon tumorigenesis by decreasing total tumor numbers in colon in both pre- and post-AOM regimes with pretreatment groups showing much prominent effect, which included longer duration of silibinin treatment. Most strikingly, silibinin pretreatments exerted strongest effect in reducing the number of biggest size tumors (>2 mm in diameter), possibly by its anti-angiogenic activity. Silibinin treatments did not show any considerable effects on body weight gain and food consumption profiles throughout the experiment, which is consistent with previous studies where administration of silibinin to various laboratory animals has not shown any adverse effects (32, 33). The higher dose of silibinin (750 mg/kg/d) used in present study was based upon and corresponds to 1% (w/w) dietary-silibinin used in other recent animal studies, without any apparent toxicity (34).

The pathogenesis of CRC involves a step-wise progression from inflamed and hyperplastic cryptal cells through flat dysplasia to finally adenocarcinoma (35). CRC growth and progression to advanced stages involve aberrant cell proliferation, evasion of apoptosis and initiation of angiogenesis, and are mediated by aberrant Wnt signaling, β-catenin accumulation and alterations in IGF signaling (8). Several studies in recent years have convincingly argued that targeting a single event alone is not sufficient to halt cancer growth, and accordingly, the agents that could target multiple tumorigenic events and associated mechanisms could be more effective in suppressing CRC growth and progression (36). Consistent with this concept, in our studies, silibinin showed strong chemopreventive efficacy against AOM-induced colon tumorigenesis, by targeting various molecular pathways associated with proliferation, apoptosis, inflammation and angiogenesis.

Although colon carcinogenesis is a multistage process, enhanced cell proliferation and ablation of apoptosis are early events in the progression of this cancer (37). An increase in cell turnover accompanied by epithelial cell damage can increase mitotic aberrations and induce changes both at genetic and epigenetic levels that favor cancer promotion (35). Cell proliferation and apoptosis biomarkers are generally used to test the efficacy of any chemopreventive agent (38). Increased proliferation is well correlated with PCNA expression (34) and in the present study, silibinin decreased PCNA levels dose-dependently. Our previous studies have suggested the inhibitory role of silibinin against tumor cell proliferation in AOM-exposed Fisher 344 rats (24). Further, we observed silibinin-caused down-regulation of cyclin D1, a marker for proliferation and cell cycle progression as well as an important downstream molecule of β-catenin pathway, unraveling the role of silibinin in exerting its anti-proliferative effect possibly by inhibiting cell cycle progression. The dynamic equilibrium established between proliferating and apoptotic cells in normal tissues appears to be lost in cancerous tissues (39). In cancer, apoptotic cells are decreased and out numbered by proliferating cells. Expression of Cip1/p21, an inhibitor of cyclin-dependent kinases, is down-regulated upon AOM administration in colon tumor development (40). Although, a controversy regarding Cip1/p21 role do exist regarding whether it is pro- or anti-apoptotic, nevertheless, it is well cited that in its absence, apoptosis evasion is witnessed in AOM models (25). In our studies, silibinin enhanced Cip1/p21 levels supporting both anti-proliferative and pro-apoptotic activities.

During different stages of colon carcinogenesis, pro-inflammatory mediators like COX-2 and iNOS are elevated (41). iNOS generates mutagenic concentration of nitric oxide which plays an important role in carcinogenesis, tumor progression and angiogenesis, and it is overexpressed in CRC (42). PGE2, a product of COX-2, increases pGSK-3β and accumulates β-catenin, and resulting β-catenin/ T-cell factor (Tcf)-dependent transcription aids in the production of cyclin D1 (12). Our results showed that silibinin decreases the levels of COX-2 and iNOS significantly, suggesting the possibility that silibinin down regulates β-catenin/Tcf signaling which in turn reduces COX-2 expression, as it is one of the downstream targets of β-catenin pathway (43). The antiangiogenic potential of silibinin has been demonstrated in HT29 xenograft and in cell culture studies (21). Angiogenesis characterized by proliferation, migration and capillary formation by endothelial cells is a prerequisite factor for solid tumor growth and metastasis (44). VEGF is one of the biomarkers for angiogenesis, and our results showed a dose-dependent decrease in VEGF levels by silibinin. β-catenin, a pleiotropic molecule, is associated with E-cadherin for cell-cell adhesion and Wnt-APC mediated signal transduction (43). Maintenance of normal levels β-catenin in membrane, cytoplasm and nuclear pools is crucial for signaling and cell adhesion functions. In normal colon, β-catenin is localized in cell to cell junction in conjunction with E-cadherin, and its cytoplasmic and nuclear levels are low. Aberrant Wnt signaling or mutant β-catenin, APC or axin results in the accumulation of β-catenin in cytoplasm which in turn translocates it to the nucleus where it forms a complex with Tcf-4/LEF resulting in the transcription of proliferative genes (29). In the present study, AOM-induced colon tumors exhibited substantial increase in β-catenin expression and this increase was accompanied by its redistribution in both cytoplasm and nucleus. In contrast, silibinin caused a significant reduction in the accumulation of β-catenin in both cytoplasm and nucleus.

Colonic mucosa and tumors of AOM-treated animals expressed high levels of IGF-1Rβ, pAkt and pGSK-3β, and low level of IGFBP-3. IGF-1R is a membrane-associated receptor tyrosine kinase. The role of IGF-1-IGF-1R in CRC is well documented; specifically, IGFBP-3 level is decreased resulting in an increased level of IGF-1, and these molecules are potential targets for CRC chemoprevention (45). The results of the present study show the reduced levels of activated as well as total IGF-1Rβ by silibinin. On the other hand, silibinin increases the level of IGFBP-3 which can sequester IGF-1 and thereby reducing its free level available to interact with IGF-1Rβ. Thus, via both these effects, silibinin could down-regulate IGF-1Rβ signaling. Further, silibinin-induced level of IGFBP-3 could exert its antineoplastic effect through IGF-1-dependent and/or -independent mechanisms, which remains to be investigated. These effects of silibinin are also supported by the similar observations reported in prostate cancer (18). Akt, upstream of β-catenin, has its importance in cell cycle regulation, and its sustained activity is implicated in growth factor-mediated transition through G1 as well as in apoptosis evasion (46). GSK-3β plays a key role in CRC development and is phosphorylated by PI-3 kinase/Akt via IGF, and its inactivation (phosphorylation) leads to dissociation of APC/axin/ β-catenin complex. Several studies have supported the role of GSK-3β as a tumor suppressor which down regulates neoplastic transformation and tumorigenesis (47). One of the prominent substrates for GSK-3β is β-catenin and it serves as a regulator of Wnt/β-catenin pathway. Our results show that GSK-3β is phosphorylated at Ser9 (inactive form) and accumulated in AOM group, and accompanied by dysregulation of β-catenin pathway. Silibinin down-regulated the inactive (phosphorylated) form of GSK-3β level and therefore could have controlled the β-catenin pathway.

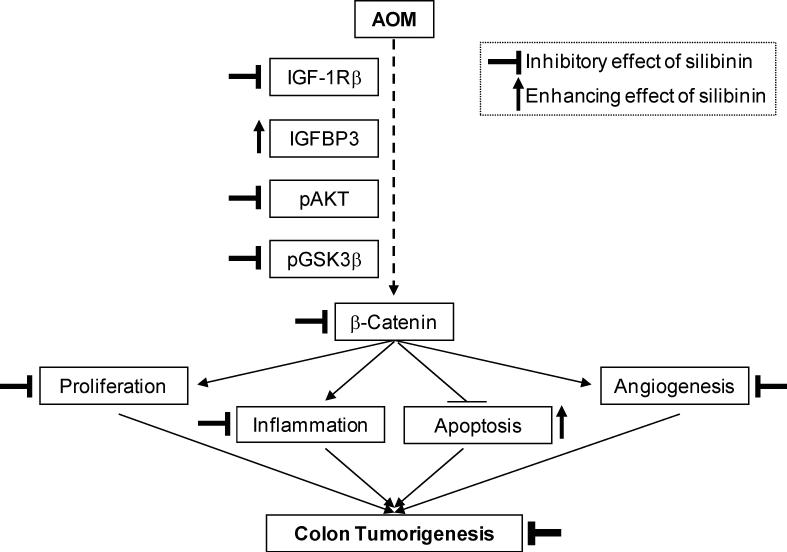

Silibinin inhibited AOM-induced colonic cell proliferation, inflammation, angiogenesis and cell survival. Since molecular markers studied for these biological events are regulated by IGF-1R as well as β-catenin signaling, it is logical to conclude that silibinin targets IGF-1R-β-catenin pathway for suppressing AOM-induced colon tumorigenesis (Fig. 6). Based on this assumption, we also speculate that silibinin possibly modulates glucose, insulin and IGFBP-3 in plasma/serum towards inhibition of IGF-1R signaling. Nevertheless, further experiments involving pharmacological agents or genetic approaches for inhibition and/or induction of selected targets (such as IGF-1R, Akt, GSK-3β and β-catenin) are needed to define the phenotypic events as well as their sequence which are regulated by IGF-1R signaling in response to silibinin. At molecular level, it is not known whether silibinin targets extracellular domain of the receptor, interferes with the ligand-receptor interaction, changes the membrane dynamics of lipid raft, or interferes with intracellular kinase domain of the IGF-1R receptor. Therefore, further studies are also needed to explore these possible mechanisms of IGF-1R inhibition by silibinin. Nevertheless, our data suggest that silibinin increases IGFBP-3 level that could sequester IGFs, and that it decreases both activated as well as total IGF-1Rβ level, as two potential mechanisms to suppress IGF-1R signaling.

Figure 6.

Proposed molecular mechanism of chemopreventive efficacy of silibinin against AOM-induced colon tumorigenesis in A/J mice. AOM induces colon tumor development through proliferation, ablated-apoptosis, inflammation and angiogenesis via action of key molecules on IGF1 axis followed by β-catenin dependent molecular mechanisms. Silibinin down regulates these oncogenic pathways leading to inhibition of proliferation, inflammation and angiogenesis but enhancement of apoptosis resulting in chemoprevention of AOM-induced colon tumorigenesis.

Overall, AOM can enhance the expression and thereby activity of IGF-1Rβ and reduce IGFBP-3 levels leading to activation of IGF-1Rβ signaling cascades involving Akt, GSK-3β and ultimately activating the β-catenin pathway. After translocating to nucleus, β-catenin stimulates proliferation, ablation of apoptosis, inflammation and angiogenesis (Fig. 6). More importantly, these AOM-caused molecular changes are brought closer to normalcy by silibinin treatment causing in vivo antiproliferative, apoptotic, anti-inflammatory and antiangiogenic effects in its overall chemopreventive efficacy against AOM-induced colon tumorigenesis (Fig. 6).

Taken together, our findings suggest that silibinin could be a potent chemopreventive agent against human CRC, and therefore warrants further studies for broadening the scope of its application to CRC patients. Importantly, silibinin is physiologically achievable upto 165 μM in plasma at 2g/kg oral dose without any toxicity in mice (34). Regarding humans, a recently completed phase I study in prostate cancer patients with silibinin (as silybin-phytosome) has shown up to 100 μM of silibinin in plasma with a half life of up to 5 hr, and its subsequent conjugation and excretion in urine (48). Another clinical study has also reported the absorption and oral bioavailability of silibinin given in different formulations (49). Also, a pilot study with silibinin in human CRC patients has reported its bioavailability and non-toxicity, and suggested its further exploration (50). Thus, silibinin has promise and potential to be developed as a chemopreventive agent against CRC.

Statement of Clinical Relevance.

Colon tumorigenesis offers a large window of 10-15 years and thus makes it suitable for chemopreventive intervention. The azoxymethane (AOM)-induced colon carcinogenesis in mice has similarity to humans in progression of ACF to polyps, adenoma and carcinomas, and underlying molecular changes. This study reports significant inhibition of AOM-caused colonic cell proliferation (PCNA, cyclin D1), inflammation (iNOS, COX-2), angiogenesis (VEGF) and cell survival, accompanied with reduced number as well as size of colonic tumors by silibinin, suggesting its strong chemopreventive efficacy against colon tumorigenesis. Silibinin also modulated β-catenin, IGF-1Rβ, pGSK-3β, pAkt, IGFBP-3 protein levels towards inhibition of colon tumorigenesis. Together, these findings suggest the multi-targeting effects of silibinin with mechanistic insight and support its translational potential in colorectal cancer chemoprevention.

Grant support

This work was supported by NCI RO1 CA112304.

References

- 1.Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Hao Y, Xu J, Thun MJ. Cancer statistics, 2009. CA Cancer J Clin. 2009;59:225–49. doi: 10.3322/caac.20006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kirman I, Poltoratskaia N, Sylla P, Whelan RL. Insulin-like growth factor-binding protein 3 inhibits growth of experimental colocarcinoma. Surgery. 2004;136:205–9. doi: 10.1016/j.surg.2004.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fields AP, Calcagno SR, Krishna M, Rak S, Leitges M, Murray NR. Protein kinase Cbeta is an effective target for chemoprevention of colon cancer. Cancer Res. 2009;69:1643–50. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Takahashi M, Wakabayashi K. Gene mutations and altered gene expression in azoxymethane-induced colon carcinogenesis in rodents. Cancer Sci. 2004;95:475–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2004.tb03235.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen J, Huang XF. The signal pathways in azoxymethane-induced colon cancer and preventive implications. Cancer Biol Ther. 2009;8:1313–7. doi: 10.4161/cbt.8.14.8983. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bissonnette M, Khare S, von Lintig FC, et al. Mutational and nonmutational activation of p21ras in rat colonic azoxymethane-induced tumors: effects on mitogen-activated protein kinase, cyclooxygenase-2, and cyclin D1. Cancer Res. 2000;60:4602–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Carmeliet P, Jain RK. Angiogenesis in cancer and other diseases. Nature. 2000;407:249–57. doi: 10.1038/35025220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Igney FH, Krammer PH. Death and anti-death: tumour resistance to apoptosis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:277–88. doi: 10.1038/nrc776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sebolt-Leopold JS, Dudley DT, Herrera R, et al. Blockade of the MAP kinase pathway suppresses growth of colon tumors in vivo. Nat Med. 1999;5:810–6. doi: 10.1038/10533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamada Y, Oyama T, Hirose Y, et al. beta-Catenin mutation is selected during malignant transformation in colon carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2003;24:91–7. doi: 10.1093/carcin/24.1.91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kohno H, Suzuki R, Sugie S, Tanaka T. Beta-Catenin mutations in a mouse model of inflammation-related colon carcinogenesis induced by 1,2-dimethylhydrazine and dextran sodium sulfate. Cancer Sci. 2005;96:69–76. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2005.00020.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shimizu M, Shirakami Y, Sakai H, et al. (-)-Epigallocatechin gallate suppresses azoxymethane-induced colonic premalignant lesions in male C57BL/KsJ-db/db mice. Cancer Prev Res (Phila Pa) 2008;1:298–304. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0045. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lynch PM. Chemoprevention with special reference to inherited colorectal cancer. Fam Cancer. 2008;7:59–64. doi: 10.1007/s10689-007-9158-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nomoto H, Iigo M, Hamada H, Kojima S, Tsuda H. Chemoprevention of colorectal cancer by grape seed proanthocyanidin is accompanied by a decrease in proliferation and increase in apoptosis. Nutr Cancer. 2004;49:81–8. doi: 10.1207/s15327914nc4901_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singh RP, Deep G, Chittezhath M, et al. Effect of silibinin on the growth and progression of primary lung tumors in mice. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2006;98:846–55. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djj231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gu M, Singh RP, Dhanalakshmi S, Agarwal C, Agarwal R. Silibinin inhibits inflammatory and angiogenic attributes in photocarcinogenesis in SKH-1 hairless mice. Cancer Res. 2007;67:3483–91. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Singh RP, Deep G, Blouin MJ, Pollak MN, Agarwal R. Silibinin suppresses in vivo growth of human prostate carcinoma PC-3 tumor xenograft. Carcinogenesis. 2007;28:2567–74. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgm218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Raina K, Blouin MJ, Singh RP, et al. Dietary feeding of silibinin inhibits prostate tumor growth and progression in transgenic adenocarcinoma of the mouse prostate model. Cancer Res. 2007;67:11083–91. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-2222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tyagi A, Raina K, Singh RP, et al. Chemopreventive effects of silymarin and silibinin on N-butyl-N-(4-hydroxybutyl) nitrosamine induced urinary bladder carcinogenesis in male ICR mice. Mol Cancer Ther. 2007;6:3248–55. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-07-2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Singh RP, Agarwal R. Tumor angiogenesis: a potential target in cancer control by phytochemicals. Curr Cancer Drug Targets. 2003;3:205–17. doi: 10.2174/1568009033481985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singh RP, Gu M, Agarwal R. Silibinin inhibits colorectal cancer growth by inhibiting tumor cell proliferation and angiogenesis. Cancer Res. 2008;68:2043–50. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-6247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kohno H, Tanaka T, Kawabata K, et al. Silymarin, a naturally occurring polyphenolic antioxidant flavonoid, inhibits azoxymethane-induced colon carcinogenesis in male F344 rats. Int J Cancer. 2002;101:461–8. doi: 10.1002/ijc.10625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gu M, Roy S, Raina K, Agarwal C, Agarwal R. Inositol hexaphosphate suppresses growth and induces apoptosis in prostate carcinoma cells in culture and nude mouse xenograft: PI3KAkt pathway as potential target. Cancer Res. 2009;69:9465–72. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2805. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Velmurugan B, Singh RP, Tyagi A, Agarwal R. Inhibition of azoxymethane-induced colonic aberrant crypt foci formation by silibinin in male Fisher 344 rats. Cancer Prev Res (Phila Pa) 2008;1:376–84. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-08-0059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Poole AJ, Heap D, Carroll RE, Tyner AL. Tumor suppressor functions for the Cdk inhibitor Cip1/p21 in the mouse colon. Oncogene. 2004;23:8128–34. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207994. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Niho N, Kitamura T, Takahashi M, et al. Suppression of azoxymethane-induced colon cancer development in rats by a cyclooxygenase-1 selective inhibitor, mofezolac. Cancer Sci. 2006;97:1011–4. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2006.00275.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Watanabe K, Kawamori T, Nakatsugi S, Wakabayashi K. COX-2 and iNOS, good targets for chemoprevention of colon cancer. Biofactors. 2000;12:129–33. doi: 10.1002/biof.5520120120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lin SS, Lai KC, Hsu SC, et al. Curcumin inhibits the migration and invasion of human A549 lung cancer cells through the inhibition of matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9 and Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF). Cancer Lett. 2009;285:127–33. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2009.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shimizu M, Shirakami Y, Iwasa J, et al. Supplementation with Branched-chain Amino Acids Inhibits Azoxymethane-induced Colonic Preneoplastic Lesions in Male C57BL/KsJ-db/db Mice. Clin Cancer Res. 2009;15:3068–75. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-08-2093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Papanikolaou A, Wang QS, Papanikolaou D, Whiteley HE, Rosenberg DW. Sequential and morphological analyses of aberrant crypt foci formation in mice of differing susceptibility to azoxymethane-induced colon carcinogenesis. Carcinogenesis. 2000;21:1567–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tammali R, Reddy AB, Ramana KV, Petrash JM, Srivastava SK. Aldose reductase deficiency in mice prevents azoxymethane-induced colonic preneoplastic aberrant crypt foci formation. Carcinogenesis. 2009;30:799–807. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Raina K, Agarwal R. Combinatorial strategies for cancer eradication by silibinin and cytotoxic agents: efficacy and mechanisms. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2007;28:1466–75. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-7254.2007.00691.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mereish KA, Bunner DL, Ragland DR, Creasia DA. Protection against microcystin-LR-induced hepatotoxicity by Silymarin: biochemistry, histopathology, and lethality. Pharm Res. 1991;8:273–7. doi: 10.1023/a:1015868809990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Singh RP, Agarwal R. Prostate cancer chemoprevention by silibinin: bench to bedside. Mol Carcinog. 2006;45:436–42. doi: 10.1002/mc.20223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kohno H, Suzuki R, Curini M, et al. Dietary administration with prenyloxycoumarins, auraptene and collinin, inhibits colitis-related colon carcinogenesis in mice. Int J Cancer. 2006;118:2936–42. doi: 10.1002/ijc.21719. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Misra S, Toole BP, Ghatak S. Hyaluronan constitutively regulates activation of multiple receptor tyrosine kinases in epithelial and carcinoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:34936–41. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C600138200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Patel BB, Yu Y, Du J, et al. Schlafen 3, a novel gene, regulates colonic mucosal growth during aging. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2009;296:G955–62. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.90726.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Naumov GN, Akslen LA, Folkman J. Role of angiogenesis in human tumor dormancy: animal models of the angiogenic switch. Cell Cycle. 2006;5:1779–87. doi: 10.4161/cc.5.16.3018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun BC, Zhao XL, Zhang SW, Liu YX, Wang L, Wang X. Sulindac induces apoptosis and protects against colon carcinoma in mice. World J Gastroenterol. 2005;11:2822–6. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v11.i18.2822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Crim KC, Sanders LM, Hong MY, et al. Upregulation of Cip1/p21Waf1/Cip1 expression in vivo by butyrate administration can be chemoprotective or chemopromotive depending on the lipid component of the diet. Carcinogenesis. 2008;29:1415–20. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgn144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Warren CA, Paulhill KJ, Davidson LA, et al. Quercetin may suppress rat aberrant crypt foci formation by suppressing inflammatory mediators that influence proliferation and apoptosis. J Nutr. 2009;139:101–5. doi: 10.3945/jn.108.096271. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen CN, Lin JJ, Lee H, et al. Association between color doppler vascularity index, angiogenesis-related molecules, and clinical outcomes in gastric cancer. J Surg Oncol. 2009;99:402–8. doi: 10.1002/jso.21193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Fuchs SY, Ougolkov AV, Spiegelman VS, Minamoto T. Oncogenic beta-catenin signaling networks in colorectal cancer. Cell Cycle. 2005;4:1522–39. doi: 10.4161/cc.4.11.2129. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yeh CL, Pai MH, Li CC, Tsai YL, Yeh SL. Effect of arginine on angiogenesis induced by human colon cancer: in vitro and in vivo studies. J Nutr Biochem. 2010;21:538–43. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2009.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sridhar SS, Goodwin PJ. Insulin-insulin-like growth factor axis and colon cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:165–7. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2008.19.8937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kaneda A, Wang CJ, Cheong R, et al. Enhanced sensitivity to IGF-II signaling links loss of imprinting of IGF2 to increased cell proliferation and tumor risk. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:20926–31. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710359105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Luo J. Glycogen synthase kinase 3beta (GSK3beta) in tumorigenesis and cancer chemotherapy. Cancer Lett. 2009;273:194–200. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.05.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Flaig TW, Gustafson DL, Su LJ, et al. A phase I and pharmacokinetic study of silybin-phytosome in prostate cancer patients. Invest New Drugs. 2007;25:139–46. doi: 10.1007/s10637-006-9019-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kim YC, Kim EJ, Lee ED, et al. Comparative bioavailability of silibinin in healthy male volunteers. Int J Clin Pharmacol Ther. 2003;41:593–6. doi: 10.5414/cpp41593. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hoh C, Boocock D, Marczylo T, et al. Pilot study of oral silibinin, a putative chemopreventive agent, in colorectal cancer patients: silibinin levels in plasma, colorectum, and liver and their pharmacodynamic consequences. Clin Cancer Res. 2006;12:2944–50. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-05-2724. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]