Abstract

Methods:

We retrospectively analyzed 657 patients with advanced gastric cancer who received first-line chemotherapy. Baseline patient characteristics and treatment results were compared between Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status (PS) 0–1 and PS 2 patients.

Results:

Prior to beginning first-line chemotherapy, 513, 112, and 32 patients were PS 0–1, PS 2, and PS 3–4, respectively. Patients with massive ascites (42% vs. 3%; P < .001) or inability to eat (39% vs. 4%; P < .001) were more likely to be PS 2 than PS 0–1. Significantly fewer PS 2 patients received first-line chemotherapy regimens containing oral agents (40% vs. 77%; P < .001) or combination chemotherapy (19% vs. 40%; P < .001) compared to PS 0–1 patients. Median survival time was significantly shorter in PS 2 patients (5.8 vs. 13.9 months; P < .001). Multivariate survival analysis revealed that use of oral agents was associated with a better prognosis in PS 0–1 patients (hazard ratio [HR] 0.76, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.59–0.97, P = .03), while it was associated with poorer survival in PS 2 patients (HR 1.52, 95% CI 1.0–2.3, P = .046).

Conclusion:

Advanced gastric cancer patients with PS 2 not only had a poorer prognosis but also differed in several baseline characteristics compared to PS 0–1 patients. These results indicate that additional clinical trials that specifically target gastric cancer patients with PS 2 may be required to evaluate optimal treatment regimens for this patient population.

Performance status (PS) is an independent prognostic factor for survival in patients with advanced gastric cancer.1,2 As a result of disease progression, patients with gastric cancer are subject to several debilitating complications, including anorexia, fatigue, and abdominal distension, that can lead to deterioration of general patient status. Overall, inclusion criteria for the majority of clinical trials have specified an Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) PS ≤ 2. According to multivariate survival analysis of three phase-III studies conducted between 1992 and 2001, PS 2 patients represented 22.8% of the patient population, and these patients experienced significantly poorer survival compared to patients with a more favorable PS.2 However, because recent pivotal phase-III studies performed in Japan3–5 and Western countries6–8 included very few PS 2 patients (2% in three Japanese trials and 0%–10% in Western trials), standard treatment of PS 2 patients has not yet clearly been established. Furthermore, the characteristics of advanced gastric cancer patients with PS 2 have not yet been reported in detail.

To address this issue, we conducted a retrospective analysis comparing baseline characteristics and treatment results in advanced gastric cancer patients with PS 0–1 vs. PS 2.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This study was a retrospective analysis of patients with advanced or recurrent gastric cancer who received chemotherapy. Principal inclusion criteria were the presence of histologically or cytologically proven, inoperable gastric cancer. Written informed consent was obtained from all patients prior to chemotherapy. Performance status was evaluated prior to initiation of first-line chemotherapy according to ECOG criteria.9

Between April 2001 and June 2008, 657 patients with gastric cancer underwent first-line chemotherapy at Aichi Cancer Center and Misawa City Hospital. Baseline characteristics and treatment results were compared between patients with PS 0–1 and PS 2. Patients with PS 3 or 4 were excluded from this analysis. The following baseline characteristics were assessed: age (<65 years or ≥65 years), gender, disease status (advanced or recurrent), previous gastrectomy (yes or no), previous adjuvant chemotherapy (yes or no), pathologic classification (diffuse or intestinal), metastasis to peritoneum (yes or no), metastasis to liver (yes or no), presence of massive ascites (yes or no), number of metastatic sites (one or multiple), and inability to eat (yes or no).

“Multiple metastatic sites” was defined as the presence of metastases in more than one organ. “Massive ascites” was defined as the presence of ascites from the pelvic cavity to the liver surface or upper abdominal cavity, or ascites that required drainage. “Inability to eat” was defined as requirement for daily intravenous fluids or hyperalimentation. Chemotherapeutic regimens were selected individually by physicians or within the context of a clinical trial. Dosing and scheduling of most chemotherapy regimens were performed as reported in the literature.3–5,10–15

First-line chemotherapeutic regimens were directly compared, with particular attention focused on oral vs. infusional drugs and monotherapy vs. combination chemotherapy regimens. Toxicities grade ≥ 3, according to the National Cancer Institute Common Toxicity Criteria version 3.0, were also compared between PS 0–1 and PS 2 patients.

Statistical Methods

Overall survival (OS) was estimated starting from the date of initial chemotherapy to the date of death or last follow-up visit using the Kaplan-Meier method. Time-to-treatment failure (TTF) was measured from the date of treatment initiation to the last day of first-line treatment. OS and TTF in PS 0–1 and PS 2 patients were compared using the log-rank test. Distribution of baseline characteristics was assessed by chi-square test or Fisher exact test, as appropriate.

To evaluate the effect of types of treatment (oral vs. infusional; combination therapy vs. monotherapy) on OS in PS 0–1 vs. PS 2 patients, univariate and multivariate Cox proportional hazards modeling was applied. Therefore, a measure of association in this study was the hazard ratio (HR) along with the 95% confidence interval (95% CI). Forward and backward stepwise methods were used for model building. Threshold P values for inclusion or exclusion in the model were defined as .10 and .20, respectively. Statistical analyses were performed using STATA ver. 10 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). All tests were two-sided, and P values less than .05 were considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Among the 657 patients, PS at initiation of first-line chemotherapy was as follows: PS 0, 172 patients (26.1%); PS 1, 341 patients (51.9%); PS 2, 112 patients (17.0%); and PS 3–4, 32 patients (4.9%). The characteristics of patients with PS 0–1 or PS 2 are shown in Table 1. A larger proportion of PS 2 patients had peritoneal dissemination, massive ascites, and/or multiple metastatic sites compared to PS 0–1 patients. A larger number of PS 2 patients suffered an “inability to eat” (39% vs. 4%; P < .001), primarily due to the presence of gastrointestinal stenosis/obstruction and/or massive ascites. In contrast, liver metastasis was less common in PS 2 patients than in PS 0–1 patients.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics (PS 0–1 vs. PS 2)

| Characteristics | PS 0–1 (n=513) n (%) | PS 2 (n=112) n (%) | P value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Median age (range) | 63 (28–85) | 64 (29–81) | .8 | |

| Gender | Male Female |

353 (69) 160 (31) |

63 (56) 49 (44) |

.01 |

| Pathologic type | Intestinal Diffuse |

166 (32) 347 (68) |

15 (13) 97 (87) |

< .001 |

| Disease status | Advanced Recurrent |

340 (66) 173 (34) |

75 (67) 37 (33) |

.9 |

| Prior gastrectomy | Yes No |

283 (55) 230 (45) |

42 (38) 70 (62) |

< .001 |

| Adjuvant chemotherapy | Yes No |

77 (15) 435 (85) |

10 (9) 102 (91) |

.08 |

| Disease site | Peritoneum Ascites (massive) Liver Multiple sites |

240 (47) 17 (3) 163 (32) 228 (44) |

83 (74) 47 (42) 21 (19) 72 (64) |

< .001 < .001 .02 < .001 |

| Inability to eat | Yes | 23 (4) | 44 (39) | < .001 |

Treatment Results

Table 2 shows the results of first-line treatment in PS 0–1 and PS 2 patients. Significantly fewer PS 2 patients (n = 1, 0.9%) were registered in clinical trials compared to PS 0–1 patients (n = 148, 29%; P < .001). Overall, first-line chemotherapy containing oral agents (S-1/capecitabine) was less frequently used in PS 2 patients (n = 45, 40%) than in PS 0–1 patients (n = 394, 77%; P < .001). Furthermore, fewer PS 2 patients received combination regimens as first-line chemotherapy (n = 22, 19%) than PS 0–1 patients (n = 210, 41%; P < .001).

Table 2.

First-line treatment in PS 0–1 vs. PS 2 patients

| PS 0–1 (n=513) n (%) | PS 2 (n=112) n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| First-line regimens | 5-FU*–based† | 277 (54) | 66 (59) |

| 5-FU* + cisplatin | 130 (25) | 12 (12) | |

| 5-FU* + taxane | 22 (4) | 5 (6) | |

| 5-FU* + irinotecan | 14 (3) | 0 (0) | |

| Irinotecan ± cisplatin | 33 (6) | 2 (2) | |

| Taxane ± cisplatin | 37 (7) | 21 (20) | |

| First-line agents | 5-FU | 444 (86) | 83 (78) |

| Cisplatin | 171 (34) | 17 (16) | |

| Taxane | 59 (11) | 26 (23) | |

| Irinotecan | 47 (9) | 2 (2) |

Including S-1 or capecitabine.

Including 5-FU plus methotrexate.

Abbreviations: 5-FU = 5-fluorouracil

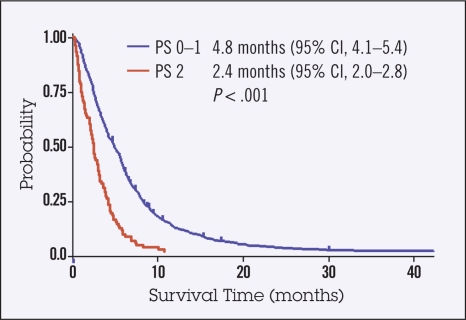

With respect to chemotherapeutic agents, taxanes (paclitaxel or docetaxel) were more frequently used in PS 2 patients than in PS 0–1 patients. In contrast, cisplatin and irinotecan were less frequently given to PS 2 patients compared to PS 0–1 patients, with reduced doses used in most PS 2 patients. Median TTF for first-line chemotherapy was significantly shorter in PS 2 patients compared to PS 0–1 patients (2.4 months vs. 4.8 months; P < .001; Figure 1). Significantly fewer PS 2 patients received second-line chemotherapy (n = 56, 50%) compared to PS 0–1 patients (n = 400, 78%; P < .001). In addition, significantly fewer PS 2 patients received third-line chemotherapy (n = 16, 14%) compared to PS 0–1 patients (n = 210, 41%; P < .001).

Figure 1.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves of time to treatment failure (TTF). Median TTF for first-line chemotherapy was significantly shorter in PS 2 patients compared to PS 0–1 patients (2.4 months vs. 4.8 months; P < .001).

Toxicity

Grade 3/4 hematologic toxicity was more frequently observed in PS 2 patients compared to PS 0–1 patients (Table 3). Febrile neutropenia also occurred significantly more frequently in PS 2 patients (6.3% vs. 1.2%). The incidence of chemotherapy-related grade 3/4 diarrhea and stomatitis did not significantly differ between PS 0–1 and PS 2 patients. Anorexia and nausea/vomiting were more frequently observed in PS 2 patients, though in some cases it was difficult to determine whether anorexia and nausea/vomiting were related to treatment, as the majority of PS 2 patients experienced these symptoms prior to chemotherapy. The frequency of treatment withdrawal due to toxicity or treatment-related death did not significantly differ between PS 0–1 and PS 2 patients (Table 3).

Table 3.

Toxicity during first-line treatment in PS 0–1 vs. PS 2 patients

| Adverse event (≥ grade 3) | PS 0–1 (%) (n = 513) | PS 2 (%) (n = 112) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Leukopenia | 5.7 | 17.8 | < .001 |

| Neutropenia | 14.3 | 26.7 | < .001 |

| Febrile neutropenia | 1.2 | 6.3 | < .001 |

| Anemia | 5.8 | 25.0 | < .001 |

| Thrombocytopenia | 0.4 | 4.5 | < .001 |

| Increased transaminases | 2.3 | 7.1 | < .001 |

| Increased creatinine | 0.4 | 1.8 | NS |

| Anorexia | 9.4 | 17.8 | < .001 |

| Nausea/vomiting | 5.6 | 11.6 | .02 |

| Diarrhea | 3.9 | 4.5 | NS |

| Stomatitis | 2.1 | 4.5 | NS |

| Treatment withdrawal due to toxicity | 5.6 | 6.3 | NS |

| Treatment-related death | 1.0 | 1.8 | NS |

Abbreviations: NS = not significant

Survival

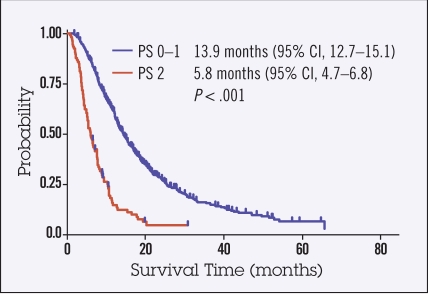

At a median follow-up time of 38 months, OS of PS 0–1 patients was 13.9 months (95% CI 12.7–15.3) and that of PS 2 patients was 5.8 months (range 4.7–6.9 months; HR for death 3.5, 95% CI 2.7–4.5, P < .001; Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves of overall survival (OS). Median OS for first-line chemotherapy was significantly shorter in PS 2 patients compared to PS 0–1 patients (5.8 months vs. 13.9 months; P < .001).

Use of Oral Agents and Combination Chemotherapy in PS 0–1 and PS 2 Patients

Table 4 shows the results of univariate and multivariate analyses comparing types of treatment (use of oral vs. infusional agents; combination therapy vs. monotherapy) and survival in PS 0–1 and PS 2 patients. In PS 0–1 patients, use of oral agents was significantly associated with better prognosis (HR 0.76, 95% CI 0.59–0.97, P = .03), while it was associated with poorer survival in PS 2 patients (HR 1.52, 95% CI 1.0–2.3, P = .046) after adjustment of other baseline characteristics. The interaction between PS and oral agents was statistically significant (P = .02). Combination chemotherapy tended to be associated with a better prognosis in PS 0–1 patients, though this difference was not statistically significant.

Table 4.

Use of oral agents and combination chemotherapy in PS 0–1 vs. PS 2 patients

| Treatment | Univariate analysis | Multivariate analysis | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | P value | HR | 95% CI | P value | ||

| PS 0–1 (n=513) | Oral agents: Yes (n=394) vs. No (n=119) Combination CTx: Yes (n=210) vs. No (n=303) |

0.75 1 |

0.59–0.94 0.82–1.2 |

.014 .92 |

0.76 0.85 |

0.59–0.97 0.70–1.07 |

.03 .19 |

| PS 2 (n=112) | Oral agents: Yes (n=45) vs. No (n=67) Combination CTx: Yes (n=22) vs. No (n=90) |

1.51 0.97 |

0.99–2.2 0.60–1.5 |

.051 .91 |

1.52 1 |

1.0–2.3 0.62–1.7 |

.046 .94 |

Adjusted by age, gender, pathologic type, disease status, prior gastrectomy, adjuvant chemotherapy, peritoneal metastasis, liver metastasis, massive ascites, multiple metastatic sites, and inability to eat. P for interaction between PS and oral agents = .02.

Abbreviations: HR = hazard ratio; 95% CI = 95% confidence interval; CTx = chemotherapy

DISCUSSION

In this study, we retrospectively compared several baseline characteristics and treatment results of PS 0–1 and PS 2 patients with advanced gastric cancer who underwent chemotherapy. To our knowledge, this is the first report to show several differences between PS 0–1 and PS 2 patients with gastric cancer in Japan. Our results demonstrate that PS 2 patients not only have a poorer prognosis compared with PS 0–1 patients but they also differ in several baseline characteristics.

Although the cause and type of PS deterioration may differ between individual advanced gastric cancer patients, the results of our study clearly showed that patients with a poor PS more frequently suffered inability to eat and massive ascites. These complications may specifically reflect the characteristics of Japanese gastric cancer patients, among whom pathologically diffuse-type disease and peritoneal metastasis are more common than in gastric cancer patients in Western countries.2,6,7 As a result of these complications, administration of oral agents is difficult in many PS 2 patients and is therefore less commonly used. Recent clinical trials3–5 have frequently excluded patients with inability to eat or massive ascites due to the increasing use of oral agents such as S-1 and capecitabine; this may explain the relatively low entry rate of PS 2 patients into clinical trials conducted at our institutions.

Additionally, our multivariate survival analysis revealed that use of oral agents was associated with poorer prognosis only in PS 2 patients (HR 0.76), while it is associated with better survival in PS 0–1 patients (HR 1.52). Although the cause of unfavorable results with oral agents in PS 2 patients is not known, it may be due in part to decreased absorption or motility in the gastrointestinal tract in patients with gastrointestinal stenosis or massive ascites, which is frequently observed in PS 2 patients in this analysis. Recent combined analysis of phase-III studies (REAL-2 and ML17032) showed that capecitabine tended to be associated with better survival than infusional 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) in PS 2 patients.16 However, less than 20% of patients had peritoneal metastasis,16,17 which is quite different from patients in this analysis (peritoneal carcinomatosis, 74%; massive ascites, 42%). Jeung et al reported the feasibility of S-1 monotherapy in patients with advanced gastric cancer with a poor PS.18 However, their study also included a relatively small proportion of patients with peritoneal carcinomatosis (29%). It would seem, therefore, that a study that specifically targets patients with peritoneal metastases might be warranted.

The results of a phase-III study in Japan, which compared 5-FU vs. methotrexate plus 5-FU in patients with advanced gastric cancer with peritoneal metastasis, were recently reported (JCOG0106).19 However few PS 2 patients (3.3%) were included in this study, because patients with massive ascites or gastrointestinal obstruction were excluded; thus, data in PS 2 patients are limited. Therefore, additional studies may be required to identify optimal regimens in PS 2 gastric cancer patients.

Since the chemotherapeutic regimens used for PS 2 patients in this analysis varied considerably, the optimal regimen for this patient population remains unclear. The incidence of treatment discontinuation due to toxicity or treatment-related death did not differ significantly between PS 0–1 and PS 2 patients, which indicates that systemic chemotherapy could be feasible and indeed warranted in PS 2 patients. Hematologic toxicity such as neutropenia, however, was significantly more common in PS 2 patients, despite a low rate of combination chemotherapy administration, suggesting that caution should be used when giving combination chemotherapy to PS 2 patients. Since current clinical trials frequently use combination chemotherapy regimens, including those containing standard doses of platinum agents, it might be necessary to exclude PS 2 patients from future trials that employ more toxic combination chemotherapy regimens.

Our study has several limitations. First, PS is not an absolute criterion for evaluating the general status of gastric cancer patients. However, no alternative criteria for classifying general status are currently available. Second, comorbidities and age were not considered. Both comorbidities and advanced age can contribute to PS deterioration and should be considered as a matter of course in the clinical decision-making process. We should develop more comprehensive criteria—including general status, nutrition status, age, and comorbidity — to make better informed decisions in the best interest of our patients. However, it should be noted that none of the patients in our analysis had poor PS due only to age or comorbidity.

In conclusion, advanced gastric cancer patients with PS 2 not only had a poorer prognosis but also differed in several baseline characteristics, including frequency of ascites and eating status, compared to PS 0–1 patients. These results suggest that clinical trials that specifically target gastric cancer patients with PS 2 may be required to evaluate optimal chemotherapeutic regimens for this patient population.

Footnotes

Disclosures of Potential Conflicts of Interest

The authors indicated no potential conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Buonadonna A, Lombardi D, De Paoli A, et al. Adenocarcinoma of the stomach: univariate and multivariate analyses of factors associated with survival. Tumori. 2003;2:S31–S34. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chau I, Norman AR, Cunningham D, et al. Multivariate prognostic factor analysis in locally advanced and metastatic esophago-gastric cancer pooled analysis from three multicenter, randomized, controlled trials using individual patient data. J Clin Oncol. 2004;22:2395–2403. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2004.08.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boku N, Yamamoto S, Shirao K, et al. Randomized phase III study of 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) alone versus combination of irinotecan and cisplatin (CP) versus S-1 alone in advanced gastric cancer (JCOG9912) J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:18s. (supple; abstr LBA4513) [Google Scholar]

- 4.Koizumi W, Narahara H, Hara T, et al. S-1 plus cisplatin versus S-1 alone for first-line treatment of advanced gastric cancer (SPIRITS trial): a phase III trial. Lancet Oncol. 2008;9:215–221. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(08)70035-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chin K, Ishi H, Imamura H, et al. Irinotecan plus S-1 (IRIS) versus S-1 alone as first-line treatment for advanced gastric cancer: Preliminary results of a randomized phase III study (GC0301/TOP-002) J Clin Oncol. 2007;25:18s. (supple; abstr 4525) [Google Scholar]

- 6.Van Cutsem E, Moiseyenko EM, Tjulandin S, et al. Phase III study of docetaxel and cisplatin plus fluorouracil compared with cisplatin and fluorouracil as first-line therapy for advanced gastric cancer: a report of the V325 Study Group. J Clin Oncol. 2006;24:4991–4997. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2006.06.8429. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cunningham D, Starling N, Rao S, et al. Capecitabine and oxaliplatin for advanced esophago-gastric cancer. N Engl J Med. 2008;358:36–46. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa073149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ajani JA, Rodriguez W, Bodoky G, et al. Multicenter phase III comparison of cisplatin/S-1 (CS) with cisplatin/5-FU (CF) as first-line therapy in patients with advanced gastric cancer (FLAGS). 2009 Gastrointestinal Cancers Symposium; (abstr 8) [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oken MM, Creech RH, Tormey DC, et al. Toxicity and response criteria of the Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group. Am J Clin Oncol. 1982;5:649–655. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Futatsuki K, Wakui A, Nakao I, et al. Late phase II study of irinotecan hydrochloride (CPT-11) in advanced gastric cancer. CPT-11 Gastrointestinal Cancer Study Group. Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 1994;21:1033–1038. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Taguchi T, Sakata Y, Kanamaru R, et al. Late phase II clinical study of RP56976 (docetaxel) in patients with advanced/recurrent gastric cancer: a Japanese Cooperative Study Group trial (group A) Gan To Kagaku Ryoho. 1998;25:1915–1924. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hironaka S, Zenda S, Boku N, et al. Weekly paclitaxel as second-line chemotherapy for advanced or recurrent gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2006;9:14–18. doi: 10.1007/s10120-005-0351-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yamao T, Shimada Y, Shirao K, et al. Phase II study of sequential methotrexate and 5-fluorouracil chemotherapy against peritoneally disseminated gastric cancer with malignant ascites: a report from the Gastrointestinal Oncology Study Group of the Japan Clinical Oncology Group, JCOG 9603 Trial. Jpn J Clin Oncol. 2004;34:316–322. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyh063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yamaguchi K, Tada M, Horikoshi N, et al. Phase II study of paclitaxel with 3-h infusion in patients with advanced gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2002;5:90–95. doi: 10.1007/s101200200015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ohtsu A, Shimada Y, Shirao K, et al. Randomized phase III trial of fluorouracil alone versus fluorouracil plus cisplatin versus uracil and tegafur plus mitomycin in patients with unresectable, advanced gastric cancer: The Japan Clinical Oncology Group Study (JCOG9205) J Clin Oncol. 2003;21:54–59. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Okines AF, Norman AR, McCloud P, et al. Meta-analysis of the REAL-2 and ML17032 trials: evaluating capecitabine-based combination chemotherapy and infused 5-fluorouracil-based combination chemotherapy for the treatment of advanced oesophago-gastric cancer. Ann Oncol. 2009 May 27; doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdp047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kang YK, Kang WK, Shin DB, et al. Capecitabine/cisplatin versus 5-fluorouracil/cisplatin as first-line therapy in patients with advanced gastric cancer: a randomised phase III noninferiority trial. Ann Oncol. 2009;20:666–673. doi: 10.1093/annonc/mdn717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jeung HC, Rha SY, Shin SJ, et al. A phase II study of S-1 monotherapy administered for 2 weeks of a 3-week cycle in advanced gastric cancer patients with poor performance status. Br J Cancer. 2007;97:458–463. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6603902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shirao K, Boku N, Yamada Y, et al. Randomized phase III study of 5-fluorouracil continuous infusion (5FUci) versus methotrexate and 5-FU sequential therapy (MF) in gastric cancer with peritoneal metastasis (JCOG0106) J Clin Oncol. 2009;27:15s. doi: 10.1093/jjco/hyt114. (suppl; abstr 4545) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]