Abstract

Objective: This is the second phase of a study aimed at determining the cultural characteristics, psychiatric needs, acculturative stressors, and management approaches of immigrant Somali children's experience in the United States. Methods: A 10-year demographics review of the Minnesota Departments of Human Services, and Children, Families, and Learning was completed. Data was obtained through unstructured interviews with educational staff, healthcare providers, and Somali children and their families in three communities, regarding cultural characteristics, barriers to care, perceptions of medical/psychiatric needs, and issues of acculturation. Health professionals/psychiatrists at a tertiary care center were also surveyed. Results: Identified acculturation issues of adolescent Somali immigrants included acculturative stress, racial discrimination, khat use, legal difficulties, language barriers, school opportunities, changes in family dynamics and developmental issues, clinical vulnerabilities, unique experiences of adolescent females, and development of new public/social behavior patterns. Conclusion: Immigrant Somali adolescents are at high risk for mental health problems due to the unique challenges they face as they attempt to assimilate two very polar cultures into one self-identity during a phase of development characterized by physical, cognitive, and emotional upheaval. Current management experiences warrant recommendations that include integration of community services, schools, and the medical system to provide education in cultural diversity, multicultural school and community publications, team sports, individual education plans, support groups, and Somali representation in school staff that has established trust with families and acceptance of mental health issues and care.

Introduction

This is the second phase of a study exploring the cultural characteristics of immigrant Somali families who have settled in Minnesota, with a specific focus on the acculturation issues encountered by the children and adolescents in these families. In the first phase of this project, the authors examined the cultural dynamics that influence the psychiatric care of adult immigrant Somalis in three Minnesota communities.1 They identified a variety of acculturation-related stressors and perceived barriers to psychiatric and medical care, and they recommended solutions to promote cultural reciprocity for both the Somali community and healthcare providers. With immigration to the United States, issues such as conceptualization and management patterns of psychiatric illnesses not previously recognized in this culture and the emergence of a possible new Somali/American “culture-bound syndrome” have become critical in the overall acculturative experience of Somali immigrants into the US.

Somalia: Country and Culture

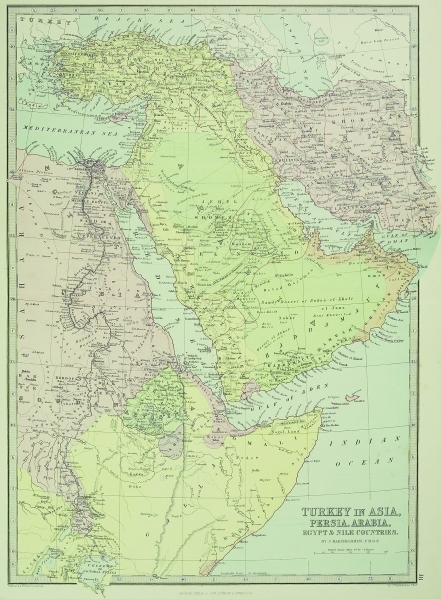

Somalia occupies the tip of a region commonly referred to as the Horn of Africa, east of Ethiopia. Approximately 70 percent of the population are nomads, traveling with their herds; 30 percent are urban residents. It is composed of a single, homogeneous ethnic group that shares language (two dialects), religion (99% are Sunni Muslim), and culture. The Somali people view strong clan consciousness as an integral part of their lives. The clans provide political power and protection, but also represent a dilemmatic aspect of life for Somalis. They pride themselves on independence and on an unwillingness to submit to unrecognized authority, which has resulted in ongoing conflict throughout their history. This is also reflected in the communication style of many Somali individuals, which more often than not, is very intense. At times, the interpersonal intensity and passionate style have been misinterpreted by teachers, employers, and peers as overly assertive and emotionally charged when compared to more culturally acceptable communication styles. This perception may lead, unfortunately, to indiscriminate and unfair stereotyping.

The patriarchal family system represents the traditional Somali values of legal marriage, honesty, good behavior, respect for elders, and group responsibility. It is the source of identity and security that is reflected in the greeting “Whom are you from?” rather than “Where are you from?” Somalis trace their heritage to a common ancestor. Men are the authority figures, and the oldest male makes decisions for the family. The oldest son holds an important position, as the expectation is that female children will obey their brothers. In many Somali immigrant families, the father is separated from the family or may even be deceased, leaving the oldest son as the head of the family. When this oldest son is not of an age to make family decisions, and with no other male to assume this role, many unprepared women find themselves in a position of authority. Women are responsible for raising children and caring for their homes. As Islam is the state religion of Somalia, and families follow the guidance of the Koran in their lives, they believe that what happens to them is “God's will,” and should not be questioned.

The country has been involved in a long political conflict dating back to 1969 and is still presently dealing with civil war and struggles to establish a cohesive government. Many Somali families were forced to flee and settle in refugee camps. The terror of witnessing war, violence, and death made life a continuous traumatic experience. There was often a shortage of food, water, firewood, constant threat of fires, and inadequate medical and hygienic supplies. Women were frequently sexually and physically assaulted by warring clan members. There were no schools for the children to attend.2–4 The harsh life in these camps was made even more desperate by the rampant use of drugs, such as khat, a readily available amphetamine-like compound, and homemade alcohol. Endemic diseases, such as tuberculosis, malaria, and tropical parasitic infections, were widespread.

Under these desolating circumstances, it is not surprising that many Somalis looked to migration as a desperate and paradoxically fantasized way to seek a new life. The US was, for many, such a destination. Unfortunately, the lives of these immigrants have been fractured by the realities of acculturation, resulting in another stressful layer to a severe traumatic experience. The end result of this chain of events is increasing psychiatric needs in a population that does not recognize mental illness or suicide. In fact, many believe that mental illness is a punishment or curse by Satan for something done wrong. If the family system cannot “absorb” the problem of one of its members, traditional medicine is often used to exorcise the waddado or evil spirit. As a result of past and present stressors, many Somalis report experiencing a symptom triad of depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which they have labeled “puffis,” a multifaceted and polysymptomatic abnormality that may represent a new culture-bound-syndrome.5 Suicide, which has been virtually unheard of in this population, has become more common despite strong religious beliefs that deny or condemn such behavior.3 Although we know that immigrant populations are more vulnerable to develop anxiety and depressive disorders, and clinically it appears that this is also evident in the Somali population, further study is warranted to test this hypothesis.

Somalia occupies the tip of a region commonly referred to as the Horn of Africa, east of Ethiopia.

In the first phase of this project, the authors completed a 10-year demographic review of the Minnesota Departments of Human Services, and Children, Families, and Learning. They identified Somali culture's views about health, illness, intrafamily relationships, coping styles, religious beliefs, perceived psychopathology, utilization of mental healthcare, as well as barriers to care and possible solutions to the encountered difficulties through individual interviews with immigrants, employers, community care providers, teachers, school counselors, and mental health professionals. The severe “acculturative stress”6 in the form of ongoing difficulties with language/communication, social isolation, financial pressures, different concept of time, deterioration of the traditional supportive family system, parenting issues, and emergence of domestic violence have been added to the traumatic experiences of war, torture, famine, and uprootedness.5,7 As in any other social or community system, these difficulties impact dramatically on the social and academic functioning of children and adolescents in these families, placing them at high risk for developing mental health problems. This article examines the realities of the adolescent Somali immigrants' life in the US as they struggle to adjust to their new social milieu.

Somali Adolescents in the United States

The first stop in the immigration process into the US is the Bureau of Citizenship and Immigration Services (BCIS), an immigration center in Clarkston, Georgia. Somalis have adopted a traditional practice called sahan (sending scouts to find rain in their home country) for the exploration of friendly settlement areas where other Somali immigrants are living. As a result of this process, Minnesota has become a major resettlement area for Somali immigrants since their first arrival in 1993. There are now more Somalis living in Minnesota than anywhere outside East Africa. This population, likely underestimated, reaches approximately 40,000.8 In addition to employment opportunities, financial resources, and public resources, many Somali families feel that Minnesota is an ideal place to raise children. In the 2001–2002 school year, there were at least 5,123 Minnesota students who reported speaking Somali as a primary language in their home.9

Acculturative stress. A key factor in understanding psychosocial distress among immigrant children is to place these issues in the context of acculturative stress.10 This condition is a result of problems children encounter when they are working to adapt their own culture and family system style into a new sociocultural structure.10 Although this is a relatively global phenomenon for all immigrant children, demonstrated by struggles with language problems, perceived and real discrimination, perceived cultural incompatibilities, and conflicts between adults and children, Somali children encounter very complex resettlement difficulties due to the unique nature of their culture and the painful experiences they have endured.

The Rochester Somali community, along with other communities and school systems in the state, has identified several key areas of struggle confronting Somali adolescents.

Aggressive behavior. The first area of struggle identified focuses on perceived behaviors of aggression reflecting what, throughout Somali history, has been an essential source of power and protection from warring clan factions. Since tribal violence and clan mentality remain an integral part of the Somali culture, this behavior is not viewed as a pathological entity and has become the basis for adolescent gangs striving for social stature in the immigrant communities. For many, especially male adolescents, this behavior has been further ingrained by conditions experienced in refugee camps. Many of these behaviors are viewed by Somali adolescents as “gaining status with the clan and appearing strong and powerful.” Obviously, non-Somali students and school staff interpret such behavior as verbal and physical aggression.

Racial discrimination. For many Somalis, the process of assimilation to American life is complicated by a first exposure to racial discrimination. With their intense pride in their own culture and language, this is a concept that is very difficult for Somalis to understand and is reported as a frequent reason of clashes between Somali and African-American students.11 Fist fights and verbal taunts are not uncommon between Somali and American students. In a February, 2004 NBC report, Natalie Walston described escalating tensions in Ohio schools over the last five years.12 Similar reports have come from Wisconsin and Minnesota schools. Although less frequently, there have also been incidents between Somali and Native American students. School officials and the African American and Somali community leaders have called for a task force to look at providing cultural education in the schools in the hopes of promoting peaceful solutions to ongoing disagreements.12

Other initiatives include, for instance, the We Win Institute, which helps African American children excel, and has also tried to build a bridge between Somali and African American students by encouraging newsletters and communication to promote better understanding of cultural differences. In Wisconsin schools, students have been encouraged to attend roundtable discussions on what initiated the conflicts and what would solve the issues. A Diversity Council to promote cultural education has been established, and a multicultural soccer team, stressing the concept of cooperation, has met with tremendous athletic and social success.13 Many referrals to child and adolescent psychiatry are due to these “behaviors of aggression” that have come to the attention of the legal system.

Khat use and legal difficulties. Many Somalis believe that they are being targeted by the legal system for their use of khat. Khat, Catha edulis, is a shrub whose stimulating leaves have been chewed and brewed in tea by Muslim cultures for centuries. Its availability and use in the US have increased with the growth of the Somali population. Khat has a bitter taste and must be consumed fresh. The leaves are often wrapped in banana leaves to preserve potency of the Cathinone, which is chemically similar to amphetamine. Khat contains the active ingredient norpseudoephedrine, similar to ephedrine, which is a precursor to methamphetamine production, found also in cold remedies and diet pills. Described as a “social lubricant” that increases self-confidence, promotes clear thought, and alleviates fatigue, Khat is chewed much like tobacco to remove the juice and then is spit out. It is used socially by 80 percent of adults in some parts of East Africa and is a common drug used by Somali immigrants in Minnesota and other resettlement areas when they congregate in social and cultural gatherings, weddings, during work breaks, and as a spiritual experience.

Somalis are very emphatic in asserting that the use of this agent is essential to maintain their cultural identity. As Somali males are considered to be adults at very young ages by Western standards, many men report beginning to use Khat as young as nine years of age. It is also known as qat, mirra, tohai, and Abyssinian tea. Since by Muslim tradition, Somalis are not allowed to drink alcohol, use of Khat is equated to American use of alcohol or coffee.14–16 For many young Somali immigrants, khat use began during the long premigration waits in refugee camps—young men would share khat-chewing sessions during which they would relate success stories and dreams of overcoming their difficult life conditions. Khat was used to create “dream travel” as a substitution for real travel. When used for prolonged periods of time, many youths have been described as losing contact with reality, getting lost in their dreams, and eventually sliding into “dream madness.”17 Although Somalis deny addictive properties to this drug, it is considered a Schedule IV substance and Cathinone, found only in fresh-picked leaves within 48 hours of harvest, is classified as a Schedule I drug. Khat generates euphoric mood and sometimes causes hallucinations.

As with other drugs of abuse, Khat does create significant social problems in the Somali culture. Women, in particular, feel that khat is harmful to family life, and many couples have divorced because the husband is using khat. Men do not chew in their homes; they go somewhere else, leaving the women in charge of the house and children. Paychecks are used to sustain the habit, and sellers have multiplied in the community. Sequelae of violence is an ever-present threat, and there have been reports of suicidal depression similar to cases of methamphetamine addiction. Khat is illegal in much of the world, including the US, Canada, UK, and most of Africa. The United Nations has called for the worldwide ban of khat.14–16 An estimated 20 percent of young immigrant Somalis use khat. Many worry that stressors of preimmigration and immigration will cause further increases in the use of this “culturally acceptable” drug.15

School opportunities. Many Somali children have not had an opportunity to attend school in Somalia or in the refuge camps in which they have lived. When they arrive in the US, they are placed in the school grade level based on their chronological age. These deficiencies in education leave many children and adolescents unprepared for the magnitude of academic achievement required for the grade level in which they are placed. Frustration and a sense of failure can lead to feelings of low self-esteem and hopelessness for many of these students, especially when they see their peers achieving academic success.

Language barriers. Although the school system provides specific English language teaching to immigrant children, learning a new language is a very stressful experience. Even into adulthood, many immigrants continue to report intense and stressful memories associated with their exposure to a new language during childhood. In 1982, Marcos, et al., reported striking similarities in the way immigrant children from different parts of the world cope with new language acquisition.18 These authors described four stages in this process. The first 3 to 6 months represent a “withdrawal stage,” with children experiencing intense fears of abandonment and insecurity. Even older children may display inappropriate clinging type of behaviors, protectiveness, and possessiveness toward their family or other members of their cultural network. The next 6 to 9 months have been described as a “despondency stage.” This stage is particularly important in that children experience a deep sense of inadequacy, inferiority, and low self-esteem. They will often describe themselves as feeling stupid, dejected, and alienated. This is often compensated for by aggressive behavior both at home and at school. Despite moving on to learn English more fluently, many children can become emotionally “stuck” in this stage, particularly those who are dealing with other traumatic experiences in their life. Between 12 and 16 months following immigration, children progress to the “adaptation phase” and view themselves as comfortable with the new language, more able to communicate, and as one with the group. Many children actually refuse to speak their original language at this stage, which is upsetting for parents who try to maintain some cultural continuity. Within the next 2 to 3 years, children commonly integrate the new language into their personal identity. It is important to realize that, despite the intellectual acquisition of a new language as with other developmental milestones, the emotions related to the child's self-identity may continue to move forward and backward through their developmental stages.18

Family dynamics. Language acquisition in the Somali immigrant community has also resulted in a dramatic change in the dynamics of families that have already been compromised by separation or death of loved ones due to the war and the immigration process itself. It is known that adolescents become acculturated more quickly than their parents (language being a definite marker), with boys acculturating even more quickly than girls.10 In the Somali community, children have become the family's communicators with the world. This has resulted in a shift of control, i.e. parental dependence on children for paying bills, answering the telephone, making financial decisions, and interpreting for the parent when interacting with the community. Many children have learned to manipulate their parents through “screening” of outside information, such as calls from the school or the legal system. In addition, parents are not sure how to discipline their children in the US. Physical punishment, which is the expected manner of discipline in Somalia, is not acceptable in this country. Many children have learned to threaten parents with reported abuse charges if not allowed to do as they please, taking away the parents' ability to set limits and maintain the safety of their children. In many families, Somali women find themselves as the only parent struggling with adolescent male children who culturally do not recognize a female as an authority figure. Many Somalis feel that this loss of family control has resulted in a large number of Somali adolescents, particularly males, becoming involved in gang types of activities and eventually with the legal system.

Developmental issues. These issues related to the different developmental tasks children need to attain at different ages. Developmental issues significantly influence the nature and expression of distress experienced by immigrant children. Acculturative stresses appear more likely to emerge as behavioral problems in childhood and identity problems in adolescence. The difficulties of choosing to embrace a new culture or cling to the culture of origin are confusing and frightening. The Somali child is facing family values, interaction styles, and social roles that many times are at very polar ends with those of the host culture. In fact, many adolescents have spent most of their life in refugee camps where much of their culture has already been buried under the basic need to survive. Recognition of this dilemma of cultural identity, frequently dramatized in the school as well as the home environment, has led to the concept of “being without culture.” W.E.B. Dubois, in his 1903 seminal work “The Souls of Black Folk,” summarizes this dilemma well.19 Immigrant adolescents are both more vulnerable and more resilient to the challenges they face with acculturation to a new host country. Their flexibility allows them to adapt much more quickly than the adults in their lives, but it also places them in a conflictual position between the original and the new. This developmental stage encompasses extensive physical, cognitive, and emotional changes. It is an overwhelming challenge for many of these adolescents to attempt to merge such polar cultures and still allow comfort with individual identity during a time of expected adolescent internal conflict and individuation. This is further complicated by exposure to the American “egocentric” focus or pragmatic individualism,10 the desire for and achievement of independence from family, and “sharing” with peers in order to be accepted as a part of the group. The Somali strive toward a “sociocentric” identity where self is identified in relation to family and other social connections, and lineage.

Clinical vulnerabilities. This struggle to achieve and maintain self-identity, in the midst of the emotional and physical upheaval that characterizes adolescent developmental changes, complicated by living in a fluctuating cultural environment, places Somali adolescents at a significant risk of developing mental illness. In school-age and adolescent immigrants, exposure to experiences of war and violence in their country of origin is predictive of a higher rate of PTSD symptoms. This is different than preschool children whose psychological well being appears to be related more to the functioning and performance of their caregiver than to the intensity of any external trauma or stress. In this population, the ongoing stressors of the immigration process itself, along with the acculturation issues encountered, tend to be more predictive of higher rates of depression and anxiety.20 Although preschool children appear to have a lower rate of PTSD than adolescents exposed to preimmigration war trauma, it is important to remember that not all children are visibly symptomatic, and many present their distress through somatic complaints. Preschool is also an age period very vulnerable to the pathologies of attachment disorders, especially when war trauma has prevented the development of a stable caregiver bond during the formative years. Both adults and adolescents report that a supportive and available ethnic community is much more helpful than support from members of the host community in dealing with acculturation issues, and provides an important buffer against the stresses of the relocation process.20

For many Somali adolescents, particularly males, there is a pervasive sense of hopelessness regarding achievement of success in their lifetime. In Somalia, male success is based on leadership and power established through traditional clan consciousness and unity. Not only has this clan social structure been severely fractured by immigration to the US, but many accepted methods leading to attainment of clan power, used throughout Somali history, are viewed as behaviors of aggression in American culture.

Adolescent women's experiences. For young women, the traditional role of wife and mother is still available and encouraged in the Somali community but, after exposure to expanded life opportunities available to females in the US, many Somali females are no longer content to accept such traditional lifestyles. Girls are taking advantage of the opportunity to obtain an education in the US. Somali adolescent girls usually work harder than boys in achieving educational success and striving to explore new paths of self-realization.21 The attractiveness and acceptability of nontraditional career choices for Somali females has been further strengthened by changes in culturally sanctioned gender roles, as more women are required to assume increasing responsibility for financial needs in many immigrant Somali families. By taking on work to provide for the family, these women have assumed gender roles traditionally held by men. Many Somali males view this “behavior” as immodest and aggressive, resulting in marital conflict and often alienation of these women in the family and the Somali community. This power shift in the dyadic relationship is a very threatening change for Somali men and has very likely contributed to the observed increase in domestic violence and substance abuse among Somali families.

The practice of female circumcision is likely one of the most complex and emotionally charged issues that promotes great discord, both within and outside the Somali community. This is not a religious practice, and is challenged by other Muslims, such as the Kurds. In the US, this is largely viewed as child abuse and has become the center of debates about potentially harmful traditional cultural practices, their health repercussions, and their legal status.22–24 Many Somali women view circumcision as normal, expected, desirable, and a path to cleanliness. Girls who have not undergone circumcision are often ridiculed and made to feel dirty and ashamed.23 In Somalia, the clitoris is associated with masculinity, and is seen as competing with men's genitalia. The ritual of circumcision actually “differentiates” between male and female, and determines the gender identity of women. After circumcision, a woman becomes a virgin and no longer possesses the ugliness of the female genitalia. Many believe that body orifices are entrances for evil spirits and therefore closure of the opening through circumcision allows a woman to protect herself and her offspring from harm. Others believe that circumcision is a method to control the insatiable and irresponsible sex drive all women possess.24

On the other hand, other Somali women feel that circumcision is a “terrible practice” leading to serious heath problems throughout the rest of the woman's life. An estimated 98 percent of Somali girls undergo circumcision. This is known as infibulation or Type III classification,22,24–26 and consists of removal of the clitoris, the adjacent labia (majora and minora), followed by the pulling of the scraped sides of the vulva across the vagina. The sides are usually secured with thorns or sewn with catgut or thread. A small opening to allow passage of urine and menstrual fluid is left. In Somalia, the procedure is usually performed by female family members and is also available in some hospitals. Concerns arise when young girls are circumcised at home with no anesthesia, using unsanitary knives, razors, or shards of glass resulting in pain and blood loss commonly leading to shock, infections, and not uncommonly, death.23,24 Despite these risks, circumcision remains a practice that is considered by many as a rite of passage into adulthood. In a culture that places a high premium on women's chastity, circumcision (not absence of sexual intercourse) guarantees a girl's virginity and insures the bride's family of receiving the marriage dowry.22

In Somalia, both men and women are circumcised between the age of 5 and 10. This is a procedure considered necessary for marriage as uncircumcised people are viewed as unclean.27 Understandably, female immigrant Somali adolescents now living in a society in which circumcision is not practiced are forced to deal with opposing norms and attitudes between their traditional culture and Western culture, which is a source of deep conflict. On the one hand, there is the desire to please family by conforming to “normal” and “healthy” cultural values, which allows the girl to be accepted by her peer group; however, the peer group now includes those from the host country who view this practice as mutilation, abuse, and a violation of women's rights to preserve the integrity of their bodies. Many Somali women feel this psychological struggle is further complicated by the “normal” expected fears of pain, suffering, and terror of hearing other children's screams while being held down by force for the procedure.22–24 Undoubtedly, more research is needed to understand the complex psychological, sexual, and physical consequences of this practice.

Public and social behaviors. Traditional Somali gender relationship patterns have also been fractured through exposure to American dressing styles, and male/female interpersonal behaviors. Islam requires women to dress modestly covering every part of their bodies except their faces, hands, and feet. Pants are considered too revealing. After puberty, contact between unrelated men and women is forbidden and physical touch, even a handshake is considered inappropriate. The public should be a man's domain, and women should not attend restaurants because this is considered immodest. Dating in the Western sense is prohibited, and marriages are traditionally arranged by families. These traditions can make attending high school a difficult challenge for a Somali adolescent female, and have been a source of discord and conflict within many Somali families. The latter expect the females to carry on the culture and maintain the family honor, so while Somali boys can blend in with their classmates who wear the same jeans and T-shirts, young women stand out in their Somali clothes. This makes participating in something as simple as gym class very difficult. Sons may visit restaurants or hang out at the basketball court, but daughters are expected to stay home, out of public view, protecting their modesty.21

America, with its equal rights and openness toward youthfulness and sexuality, beckons Somali teenagers to identify themselves with their American peers in school, who are viewed as having much more freedom and autonomy. Therein lies the dilemma: How to live by American rules at school without upsetting the Somali people and their culture. One girl described this as living like a turtle: “you have to learn to live on both the land and the water—at home and at school."21 Much of the tension between Somalis and other kids stems from misunderstanding the Muslim religion and Somali culture. Many kids do not understand Somali customs, such as washing hands and feet in the school bathrooms before praying. A common scene at the school cafeteria bears witness to the cultural apartheid, with Somali girls gathered on one side of the room, apart from the Somali boys, the Asian kids, the Caucasians, and the African Americans. One Somali girl describes being misunderstood when they do not shake hands or touch boys—a Somali cultural and religious practice. Sometimes, non-Somali boys become offended by this and think this is a gesture of dislike. Most Somali girls are not allowed to date, which also causes hard feelings among classmates.

Many Somali boys report difficulties interpreting sexual behaviors of their peers in school; for instance, when a female displays parts of her body such as legs, arms, or chest, this is interpreted as a sexually welcoming gesture. Recognition and exploration of sexuality is an important developmental task of adolescence and expression of sexuality between American teens is certainly much more relaxed than allowed in Somali culture. Based on their cultural views, however, many Somali males felt that American or Somali girls in American dress were sending a message of sexual welcome Many of these girls, in turn, interpret the male's behavior as sexually inappropriate or even offensive. These situations can quickly erupt into highly charged conflictual situations, not only between the two adolescents involved, but between entire groups of students in the school. School counselors and social workers have expressed concern regarding an increasing number of situations involving adolescent Somali males' inappropriate sexual behaviors.

Many Somali adolescent males also struggle with teachers and other females in positions of authority within the school setting. Since the patriarchal family system stresses male authority figures and role models, submitting to a female authority figure is viewed as very demeaning, a sign of “weak masculinity.”

Discussion

Recognizing the struggles encountered by Somali adolescents in the school setting has been a very positive beginning toward implementing helpful intervention measures. Integration of both the community and school resources has met with a measure of success. In Rochester, Minnesota, public school personnel report that involvement of Somali students in Conflict Mediation Facilitation has provided an acceptable avenue for “attainment of power and group stature” through leadership activities by allowing Somali students to feel that their values are important and visible. The Conflict Mediation Facilitation approach has also helped Somali students to identify stressors that are unique to their acculturation process and begin to address these issues in a healthy, socially acceptable manner. The students are not only involved in problem-solving, but they are required to teach conflict management skills that they have learned to other high school, middle school, and elementary school students. This provides them with options for appropriate behavior and language responses to difficult situations, as well as with an outlet of anger that does not result in negative consequences. Most importantly, these issues are addressed by a “validated source” of a Somali peer. This is also a resource for students to explore and identify nonverbal and verbal misperceptions in communication, since English is a second language to most Somalis. All involved benefit from improved self-esteem. The Intercultural Mutual Assistance Association, a multicultural community group has also become involved in this mediation to help facilitate, guide, and support the community and the school in promoting communication, drug and crime prevention, and life skills education in a manner that recognizes both American and Somali values.

As in other schools that have initiated round table discussions and multicultural publications, education classes and retreats have been used to highlight cultural diversity and counter prejudice against different life styles. Adolescents learn about mutual respect in relation to personal space, dress, and gender relationships. This has allowed many Somali adolescents to function in a more comfortable, positive manner in school. Education has addressed the importance of teachers, male and female, as positive role models for students, along with the need for school authorities to maintain safety and the organization requirements of a conducive learning environment. Introduction of adolescent support groups has provided an opportunity for Somali students to share unique concerns, experiences of change associated with immigration, and struggles with acculturation issues. It allows students to share family conflict experiences that frequently have common themes, providing peer empathy, emotional support, and exploration of solutions to family disagreements. This promotes the family style of problem solving that has been utilized by generations of Somali families. Of note, these groups have been accepted by female adolescents much more readily than males. Male adolescents are much more receptive to the supportive atmosphere of school team sports, such as the implementation of the multicultural soccer team (successful in Wisconsin), and the informal intramural sports teams established in many schools in Minnesota. Team sports provide a healthy manner for adolescent Somali and non-Somali males to attain “status and power” through the challenge of winning, thus allowing a positive, culturally acceptable outlet for assertiveness. To be productive or win, team sports motivate all individuals to identify themselves as a member of a group no longer fractured by differences in cultural values. This is a concept readily embraced by American culture's historical emphasis on the value of cohesiveness as a people, as well as Somali culture's historical emphasis on the value of lineage and unity based on clan consciousness. Both of these views readily illustrate the necessity for all cultural groups to strive for power as a source of protection for their members. In addition, many Somali girls are finding participation in athletics and sports to be an enjoyable new experience, in spite of persistent debates about perceived immodesty in behavior and dress.

Individual assessments for special education, individual education plans (IEP), and alternative teaching programs are very important for Somali students who have not had an opportunity to attend school in the past. Providing individualized programs promotes a feeling of success and accomplishment, which is many times reflected in a positive attitude toward continued achievements and hopefulness about the future.

The schools have become much more aware of the idioms of distress and emotional pain of the young immigrants, which allows earlier intervention to children in need. The addition of Somali staff, counselors, and teachers has provided cultural perspectives in the education of both Somali and non-Somali students. Somali school staff members have eased tensions between teachers and Somali students by addressing issues of respect for male and female authority figures in the school setting. They have also improved school communications with families who may not speak English, as well as their children, encouraging parents to be more involved with the education of their children. This has helped families to learn about the American educational system, and the importance placed on being on time, completion of schoolwork, and consistent attendance. As with other students, teachers have found that Somali children achieve much higher academic success in school when their parents are involved in their education. Finally, the presence of Somali school staff has provided an avenue for establishment of trust with the school system, and allowed Somali families to be more receptive to identified psychiatric needs of their children, along with the mental health care that is recommended. Most importantly, Somali staff in the school has allowed Somali students and families to feel that they are an important and acknowledged presence in the American school system.

Effectiveness of Interventions

All school personnel interviewed felt that the key to providing effective interventions involved improved communication and education. Although we have no specific objective statistics regarding the effectiveness of these interventions, subjective reports from teachers and counselors indicate that there may be as much as a 50-percent decrease in school conflict particularly between African American and Somali students. They did not feel, however, that there has been as significant a decrease in clan conflict between various Somali groups. All school personnel felt that encouragement of continuing education after high school completion as standard practice for future planning increases the likelihood of students attending higher education programs, but they have also noted that Somali parents (especially mothers) now have expectations of their daughters and sons to pursue a career and complete a college education and view this as a normal pathway to financial stability in America.

Being considered competent and maintaining pride are qualities that each Somali strives for. The acculturative transition of Somali immigrants to America has frequently been accompanied by pain and humiliation. Many types of psychiatric syndromes reflect the shattering of dreams, the sounds of a poetry that no longer rhymes in the heart and soul of these immigrants. Many Somalis, and especially those of the older generation, have had enormous difficulties learning English. Being unable to communicate adequately causes dependence and social isolation. Much of the difficulty with learning English stems from the fact that many of the language teachers are not fluent enough in the various Somali dialects and language uses. It is thought that promoting a more bilingual approach to teaching English would be a very helpful first step to improve communication and prevent emotional discomfort.

Somalis have many cultural values and practices that can be effectively utilized to promote compliance and improve medical and mental health care. The patriarchal family system, often described as controlling and perceived as dictorial, can enhance a strong family cohesiveness and need for family pride and respect; therefore, a family approach to the psychiatric care of any Somali patient could be useful.28 Family education and involvement can go a long way to improving compliance. Cultural values of honesty and a sincere desire to help are valued by Somalis, and if recognized and competently used, would promote a trusting relationship between patient and doctor. Emphasis on the Somali values of cooperation and mutual help stimulates group support and active participation in therapeutic endeavors. Yet, a major concern of healthcare providers is the lack of community resources available for Somali families, and the subsequent absence of financial assistance needed to establish these services.

Many Somalis spoke of the importance of becoming educated regarding how things are done in the United States.8 Every Somali interviewed was receptive to learning the American practices of limit-setting for their children, but did not know who to turn to, since this subject has become laden with fear of arrest by the police and control issues with children. There is also a need for learning how to deal with marital concerns to decrease domestic violence and abuse. Somalis need to learn about the American concept of time, more structured and less flexible in this country as compared to Somalia. This understanding would allow improved school and work performance, more job security, and more active participation in therapeutic and preventive efforts.

There is also a need to learn appropriate and expected behaviors regarding everyday paperwork, bill paying, and government and private bureaucratic requirements. These are activities with which many Somalis, especially those women who have now been placed in a position of authority in their families due to loss of husbands and fathers, are unfamiliar. Having paperwork done and bills paid on time is confusing and different. In short, counseling and social skills education of both children and parents would turn uncertain acculturation outcomes into a rather positive experience.1

Conclusion

Although adolescent Somali immigrants are faced with many issues common to all immigrant adolescent populations, they also encounter unique acculturation issues due to preimmigration exposure to the trauma of war and refugee camps, as well as ongoing stressors they face after arriving in the US. Although they appear to acculturate much more quickly than their parents, adolescents are forced to deal with radical lifestyle changes, and a loss of a fragile equilibrium in the perception of their cultural identity during a developmental period characterized by tremendous emotional, physical, and cognitive upheaval. It is an overwhelming developmental task to attempt to merge these very polar cultural values into a comfortable identity of self as a whole person. This process places these adolescents at a high risk for developing aberrant behaviors and mental illness. Emergence of a triad of PTSD, depression, and anxiety, labeled “puffis” by Somalis, is now becoming more evident in the adolescent population. Idioms of distress are visible in the struggles of these children, as they attempt to adjust to new school, family, and social systems in the US. In addition to learning a new language, many Somali adolescents are encountering the concept of racism and cultural misunderstanding for the first time, which has resulted in violent physical and verbal conflict with non-Somali students. With children commonly acquiring fluency in English more quickly than their parents, there has been a tremendous shift in family dynamics. Threats to report parents for child abuse have limited normal parenting methods in many Somali families and have placed children in a position of control. It is felt that this has contributed to increased involvement of adolescents in gangs and conflicts with the legal system.

The loss of normal avenues of life success through the clan environment has caused many Somali adolescents, particularly males, to express hopelessness for the future and has been described by school personnel as “being without a culture.” On the other hand, significant changes in traditional male-female gender roles have resulted in more women becoming financial contributors to the family's everyday life by working outside the home; however, this change in gender role may also be contributing to an increase in domestic violence among Somali families. Furthermore, the collision of traditional Somali values (clear roles for men and women and a sociocentric identity) with American values of equal rights, obsession with sex and youth, and an egocentric identity with the perception of increased independence and freedom of American teens, is an issue confronting both male and female Somali adolescents. Young Somali women, in particular, fight a daily war to fit in as they have to deal with the clash between their American peers' lifestyle and the expectation that they adhere to the traditional Somali female behaviors, dress, and cultural practices, such as circumcision.

School personnel working with the community have found that educational approaches aimed at promoting acceptance of cultural diversity have eased some of the acculturative stressors and provided enrichment of self-worth in all students. Somali school staff has provided a further source of mutual trust, a link between the school and Somali families, with a concomitant sense of importance and presence for Somalis in the school system. Establishment of multicultural publications, round table discussions, involvement in conflict mediation facilitation, participation in multicultural team sports, support groups, education regarding mutual respect and appropriate avenues for expression of anger, and involvement of community organizations are some of the interventions that have proven to be successful and well accepted in the school and community.

America, as the melting pot of the modern world, or better yet, the paradigm of a constructive pluralism, needs to facilitate the success of all her children, as they are the ingredients that will influence the future of the multifaceted, diverse, and constantly evolving American culture.

Contributor Information

Deborah L. Scuglik, Dr. Scuglik was from the Department of Psychiatry and Psychology, Mayo Clinic and Foundation, Rochester, Minnesota, at the time of this study; Dr. Scuglik is now from the Department of Psychiatry, Affinity Health Systems, Appleton, Wisconsin.

Renato D. Alarcon, Dr. Alarcon is from the Department of Psychiatry and Psychology, Mayo Clinic and Foundation, Rochester, Minnesota.

References

- 1.Scuglik D, Alarcon R, Lapeyre III A, et al. When poetry no longer rhymes: Somali immigrants in an American psychiatric clinic. Transcult Psychiatry. doi: 10.1177/1363461507083899. (submitted for publication) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rafuse J. Multicultural medicine: Dealing with a population you were not quite prepared for. Canadian Medical Association Journal. 1993;148:282–5. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lennon E. Strengthening Lives, Rebuilding Communities: Somalis Recover From War. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Center for Victims of Torture; 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kinzie D, Boehnlein J, Riley C, Sparr L. The effects of September 11 on traumatized refugees: Reactivation of posttraumatic stress disorder. J Nerv Ment Dis. 2002;190:437–41. doi: 10.1097/00005053-200207000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jimale M, Ahmed B, Hamud M, et al. Cultural Awareness: The Somali Culture. Mayo Clinic Foundation Education 2002.

- 6.Alarcón R. Reflexiones en Torno a la Psiquiatria Latinoamericana. Caracas: Asoc Psiquiat America Latina; 2003. Estres de aculturacion como probable categoria nosologica: El caso hispanico In: Los Mosaicos de la Esperanza; pp. 215–235. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Robinson V. Zumbro Valley Mental Health Center. D. Scuglik, (personal communication). Rochester, 2003.

- 8.Burke H. Immunization and the Twin Cities Somali community: Findings from a focus group assessment. Minneapolis, MN: Minnesota Department of Health Refugee Health Program; 2001. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grumney R. Somali Populations Favor Metro Areas. Minnesota Department of Children, Families, and Learning. Minneapolis Star and Tribune. March 16, 2002 ed. Minneapolis, 2002.

- 10.Guarnaccia P, Lopez S. The mental health and adjustment of immigrant and refuge children. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 1998;7:537–553. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Williams B. Not quite Africans, not quite Americans: Minnesota Public Radio, Minneapolis, 2002.

- 12.Walston N. Somali community concerned with school violence: www.nbc4i.com/education/2828729/detail.html.

- 13.Johnson M. Diversity and growing pains come to small-town Wisconsin. Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. 2004 Milwaukee, WI. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Larsen K. Cops pull khat's leash. Cannabis Culture: Hot Pot; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jones V. Cultures clash on streets over Canada's ban on khat. The Toronto Star. 2001 Friday, July 27, 2001 ed. Toronto. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Siek S. Meth-Like Khat Violates US Drug Laws. Dayton Daily News. 2002 Dayton. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Roussear C, Said T, Gagne M, et al. Between myth and madness: The premigration dream of leaving among young Somali refugees. Cult Med Psychiatry. 1998;22:385–411. doi: 10.1023/a:1005409418238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marcos L. Adults' recollection of their language deprivation as immigrant children. Am J Psychiatry. 1982;139:607–10. doi: 10.1176/ajp.139.5.607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Williams B. Somalis in Minnesota: Minnesota Public Radio, Minneapolis, 2002.

- 20.Sack W. Multiple forms of stress in refuge and immigrant children. Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 1998;7:153–167. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Thatcher M. A Primer on Traditional Somali Culture. Minneapolis Star and Tribune. [February 15, 2002]. Minneapolis, MN, June 25, 2000. Available at: www.startribune.com.

- 22.Lewis T, Hussein K, Ahmed K, et al. Somali Cultural Profile (1996) [January 6, 2005]. Seattle Ethnomed Website. Available at: ethnomed.org/ethnomed/cultures/somali.

- 23.Harvey C. Doctor of mercy. Brown Alumni Magazine. 2002 Jan–Feb;:38–45. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Transgrud K. Female Genital Mutilation: Recommendations for Education and Policy. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Toubia N. Female circumcision as a public health issue. New Engl J Med. 1994;331:712–16. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199409153311106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rasbridge L. Somalis culture health refugees immigrants: Baylor University, 2005. [January 6, 2005]. Available at: www3.baylor.edu/~charles_kemp/somali_refugees.htm.

- 27.Oliver M, Kargas E, Steen M, et al. Immigration in Minnesota: Challenges and opportunities. St. Paul, MN: League of Women Voters of Minnesota Education; 2002. pp. 1–58. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Constello A. Somalis: Their History and Culture. [February 1, 2002]. Refugee Service Center. Refugee Fact Sheet #9. Available at: www.cal.org/rsc/somali/ssoc.