Abstract

Background and study aim

The establishment of precise and valid diagnostic criteria is the first step towards understanding the pathogenesis of Barrett’s esophagus in Asia. The present study determined the interobserver reliability in the endoscopic diagnosis and grading of Barrett’s esophagus among Asian endoscopists.

Patients and methods

Video clips of endoscopy in 21 patients with and without Barrett’s esophagus were used for training (n=3) and standardized diagnosis and grading (n=18) of Barrett’s esophagus by endoscopists from seven hospitals in different Asian regions/countries. Barrett’s esophagus, where present, was graded using the Prague C & M Criteria whereby the circumferential extent of Barrett’s segment (C value), maximum extent of Barrett’s segment (M value), location of the gastroesophageal junction, and location of the diaphragmatic hiatus were scored. The intraclass correlation coefficients (ICC) were calculated as a measure of interobserver reliability.

Results

A total of 34 endoscopists participated. The ICC values for the scores of C value, M value, location of the gastroesophageal junction, and location of the diaphragmatic hiatus were 0.92 (95% CI, 0.88–0.97), 0.94 (0.90–0.98), 0.86 (0.78–0.94), and 0.81 (0.71–0.92), respectively, indicating excellent interobserver reliability. The differences in region/country, experience of endoscopists, volume of participating center, or the primary practice type did not have significant effect on the reliability. The ICC values for recognition of Barrett’s esophagus with an extent ≥1 cm were 0.90 (0.80–1.00) and 0.92 (0.87–0.98) for the C and M values, respectively, whereas the corresponding ICC values for Barrett’s segment <1 cm were 0.18 (0.03–0.32) and 0.21 (0.00–0.51), respectively.

Conclusions

Despite the relatively uncommon occurrence of Barrett’s esophagus in Asia, endoscopists in our study exhibited excellent consistency in the endoscopic diagnosis and grading of Barrett’s esophagus using the Prague C & M Criteria. In view of the low interobserver reliability in recognizing Barrett’s esophagus segments of <1 cm, future studies in Asia should take this into account in their selection strategies as to recruit as homogeneous a population for study as possible.

INTRODUCTION

The prevalence of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and Barrett’s esophagus has been increasing in Western countries, resulting in considerable burden in the prevention, surveillance, and management of this disease and its sequelae [1–3]. Although the prevalence of both reflux symptoms and erosive esophagitis has also been increasing in Asia [4], the incidence of Barrett’s esophagus and esophageal adenocarcinoma remains low in the region [5–11]. This potentially represents a delay in the transition from low-grade to high-grade disease which may provide a window of opportunity for etiologic and preventative studies [12–15].

In 2008, the U.S. National Cancer Institute organized an Asian Barrett’s workshop, which was attended by an international group of experts in the field of upper gastrointestinal malignancies [16]. The workshop provided the impetus to form an Asian Barrett’s Consortium (ABC) among attendees. The main purpose of the consortium was to provide a forum for sharing ideas and resources that would enable these experts to develop collaborative strategies to identify etiologic determinants of Barrett’s esophagus and its ensuing malignant transformation in Asia. In order to eliminate potential variation in interpretation of disease burden arising from diagnostic heterogeneity at the individual or country level, the establishment of precise diagnostic criteria was one of the consortium’s first priorities. Endoscopy is the investigative tool of choice for diagnosing erosive GERD and Barrett’s esophagus, and standardized criteria have been developed to ensure acceptable interobserver agreement in the diagnosis of these conditions [17,18]. The Los Angeles classification has been confirmed reliable in the description of the extent and length of mucosal breaks in esophagitis [19,20]. Although the use of Prague C & M Criteria has been found useful for the screening of Barrett’s esophagus in Asian populations [21–23], the reliability of its use remains unclear. This is a particular concern in Asia, where the incidence of esophageal adenocarcinoma is low, but the availability of endoscopy is high. There are conflicting reports regarding the prevalence rates of Barrett’s esophagus in Asia [21,24–31], suggesting the possibility of a substantial variation in the interpretation of short-segment disease, which is the predominant type of Barrett’s esophagus in the region [32,33].

The primary aim of this multinational study was to determine whether the use of the Prague C & M Criteria can facilitate the achievement of satisfactory interobserver reliability in the endoscopic recognition and grading of Barrett’s esophagus among a group of geographically diverse endoscopists in Asia. Our secondary objective was to identify any source of variation in diagnostic interpretation, the finding of which may provide guidance towards better consistency in diagnosing this premalignant lesion.

METHODS

To evaluate interobserver reliability in endoscopic diagnosis and grading of Barrett’s esophagus, video clips containing the endoscopic images from 11 cases with endoscopically suspected Barrett’s extents <3 centimeter (cm) and 10 with extents ≥3 cm were prepared under the guidance of one of the coauthors (PS). Four cases were considered to show concomitant erosive esophagitis. All videos were recorded using high resolution endoscopes from the different endoscope manufacturers (Olympus, Fujinon, or Pentax) and provided by the International Working Group for the Classification of Oesophagitis (IWGCO) [34]. The details of video preparation have been described previously [18]. The endoscope insertion depth in cm was displayed on the left-hand corner of the video image. Similar training video and guidance are available from the IWGCO Web Site.

Seven participating centers provided a total of 34 experienced endoscopists (minimum 5 years experience in endoscopy and had performed at least 1,000 endoscopic procedures) to undertake this study. This generalized criterion was set up according to the volume of each center to ensure the level of competence of participants to be representative for the population of practicing endoscopists across the seven Asian regions/countries. Their experience, primary practice type, and volume of endoscopies performed at their respective affiliated institution in the preceding year (2008) were recorded in a self-reported questionnaire.

Before the assessment, each center nominated a team leader responsible for organizing the local training and testing sessions. During the second meeting held in Chicago, June 2009, a senior investigator (PS), who was involved in the development of the Prague C & M Criteria, introduced its principle to the team leaders. Three educational video clips were shown to facilitate their understanding. This expert panel had a thorough discussion of defining the esophagogastric junction based on the both the top of gastric folds and the distal end of the palisade blood vessels. Because of the superiority in recognizability and the fact that the videos were not prepared to study the palisade blood vessels, the top of gastric folds was selected through a voting procedure. During the third meeting held in New Orleans, May 2010, an evaluation of test videos by the team leaders also confirmed that distal end of the palisade blood vessels could be identified only in 48% of ratings.

Next, a set of standard study materials, which included three educational and 18 test videos, were sent to each participating center. Using the three educational videos, the team leaders were able to familiarize his/her local participating assessors with the use of the Prague C & M Criteria by group sessions. Once the assessors felt confident about using this rating system and all their questions had been answered, the formal reliability testing with the 18 test videos began and the results were recorded on a standard scoring sheet.

Endoscopic Rating Using the Prague C & M Criteria

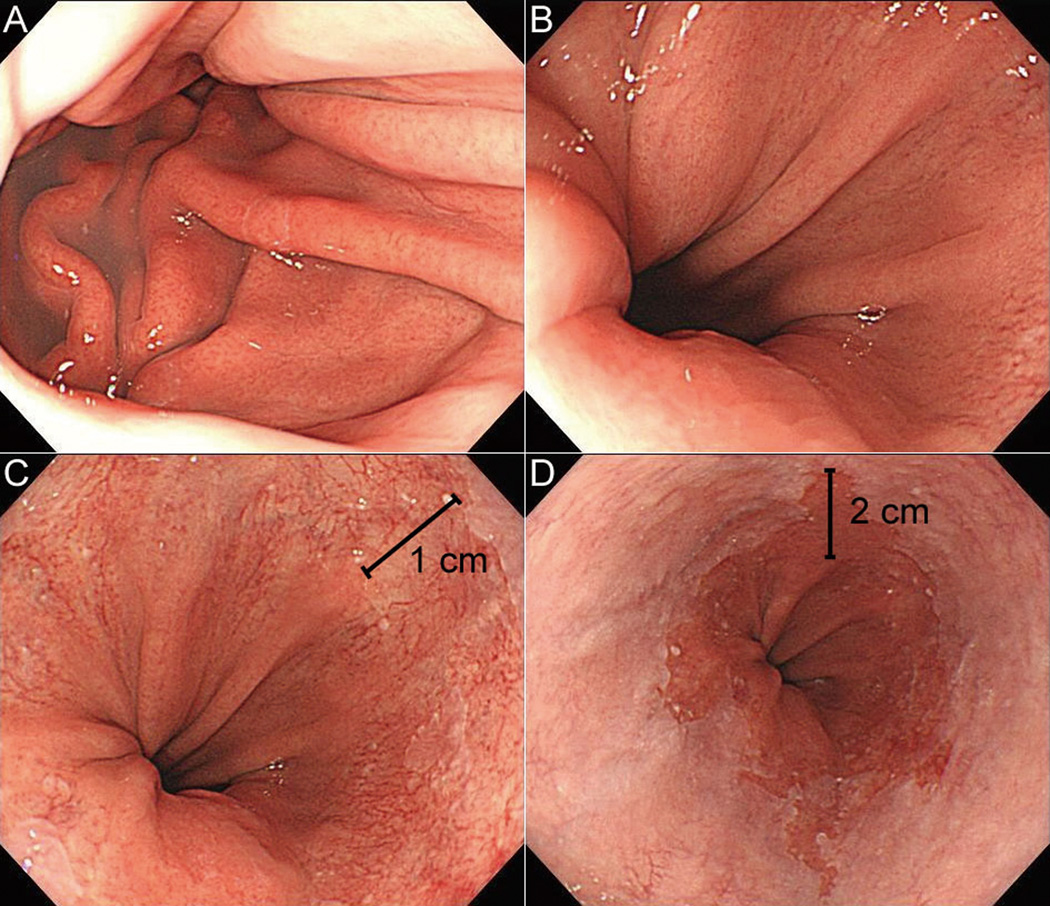

Assessors were asked to identify the location of key landmarks in each video clip and record their respective locations in cm. This is the point just before the observed feature comes into full-view on withdrawal of the endoscope. The C value is the difference in the distance between the position recorded for the gastroesophageal junction and the proximal margin of the circumferential Barrett’s epithelium. The M value represents the difference in the distance between the position recorded for the gastroesophageal junction and the proximal margin of the longest tongue like segment of the Barrett’s epithelium. The representative images are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Images of a short-segment Barrett’s esophagus showing the landmarks for endoscopic rating, including the diaphragmatic hiatus (A, 40 cm in depth), proximal end of gastric folds (B, 39 cm), extent of circumferential metaplasia (C, 38 cm), and maximal extent of the metaplasia (D, 37 cm). This lesion is therefore interpreted as C1M2 based on the Prague C & M Criteria.

The study flow is briefly described as follows: (i) record the location of diaphragmatic hiatus; (ii) record the location of gastroesophageal junction (defined as proximal end of the gastric folds); (iii) identify the presence of circumferential “ring” or “pinch” near the proximal end of the gastric folds; (iv) identify the circumferential or tongue-like segment of columnar epithelia above the gastroesophageal junction and record their respective extents as the “C value” and “M value”; (v) identify the presence and evaluate the severity of mucosal breaks; and (vi) evaluate the technical adequacy of each video clip.

Statistical Analysis

Interobserver reliability in determining the length of C & M and other parameters were expressed as a reliability coefficient, the Intraclass Correlation Coefficient (ICC). ICC is a measure of consistency for a data set rated by multiple assessors and is approximately the mean of all pairwise weighted κ values [35]. Mathematically, it is defined as the ratio of the variance between raters over the total variance. A perfect interobserver reliability is denoted by an ICC value of 1, while values >0.8 denote excellent reliability, 0.8-0.6 denote good reliability, 0.6-0.4 denote fair reliability, and <0.4 denote poor reliability. ICC values and their respective 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were computed using the Stata software package (Release 10, StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

To ensure our sample size was adequate for estimation, we included at least three assessors from each of the seven centers. We set a minimally acceptable level of reliability (ρ0) at 0.6, and expected a rho value (ρ1) of ≥0.8 for a 1 cm difference in observations between assessors. Following the methods proposed by Walter et al. [36], the number of videos required to detect this difference at α =0.05 and β =0.2 was approximately 15.

Source of Variation in Rating

Variations in rating may arise from the variations in assessment. To reach the secondary goal of the study, we stratified the data according to characteristics of the endoscopists and videos, and tested whether interobserver reliability was sensitive to each specific parameter. Endoscopist characteristics included the number of years as an endoscopist, number of procedures performed in their career, number of procedures performed in the participating center in 2008, primary practice type, and region/country of practice. Given that the short-segment Barrett’s esophagus is more prevalent in Asian countries compared with Western Europe and North America, the videos were stratified according to their average C and M values as reported by the raters to simulate the regional patient characteristics. We stratified the 18 test videos with the cut-off values of <1 cm, ≤ 1 cm– <3 cm, and ≥3 cm for their C and M scores and examined at which point the stratification would result in a clear discontinuity in the values of the reliability coefficients.

RESULTS

Interobserver Reliability Based on the Prague C & M Criteria

A total of 34 endoscopists participated in this study, including five from China (Qilu Hospital, Shandong University, Shandong Province), three from Hong Kong SAR (Prince of Wales Hospital, the Chinese University of Hong Kong), six from India (Seth GS Medical College and KEM Hospital, Mumbai), three from Japan (Nagoya University Graduate School of Medicine, Nagoya), five from Korea (Sungkyunkwan University School of Medicine, Samsung Medical Center, Seoul), five from Singapore (National University Hospital), and seven from Taiwan (National Taiwan University Hospital, Taipei). The overall reliability coefficients are shown in Table 1. The ICCs for four assessed key parameters, the C score, M score, location of the gastroesophageal junction, and location of the diaphragmatic hiatus were 0.92 (95% CI, 0.88–0.97), 0.94 (95% CI, 0.90–0.98), 0.86 (95% CI, 0.78–0.94), and 0.81 (95% CI, 0.71–0.92), respectively; all indicated excellent levels of reliability.

Table 1.

Reliability coefficients of the Prague C & M criteria in rating Barrett’s esophagus stratified by countries

| Parameters | China | Hong Kong | India | Japan | Korea | Singapore | Taiwan | All |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 5) | (n = 3) | (n = 6) | (n = 3) | (n = 5) | (n = 5) | (n = 7) | (n = 34) | |

| C value | 0.99 (0.98–1.00) |

0.89 (0.80–0.97) |

0.86 (0.78–0.95) |

0.98 (0.96–1.00) |

0.94 (0.90–0.98) |

0.91 (0.84–0.97) |

0.94 (0.90–0.98) |

0.92 (0.88–0.97) |

| M value | 0.99 (0.98–1.00) |

0.90 (0.82–0.98) |

0.86 (0.77–0.95) |

0.98 (0.96–1.00) |

0.98 (0.97–1.00) |

0.94 (0.89–0.98) |

0.98 (0.96–0.99) |

0.94 (0.90–0.98) |

| Gastroesophageal junction | 0.98 (0.96–0.99) |

0.78 (0.62–0.93) |

0.73 (0.58–0.88) |

0.93 (0.88–0.99) |

0.92 (0.86–0.98) |

0.91 (0.84–0.97) |

0.95 (0.91–0.98) |

0.86 (0.78–0.94) |

| Diaphragmatic hiatus | 0.51 (0.11–0.92) |

0.77 (0.60–0.94) |

0.87 (0.79–0.96) |

0.96 (0.92–0.99) |

0.88 (0.80–0.96) |

0.81 (0.69–0.93) |

0.86 (0.78–0.95) |

0.81 (0.71–0.92) |

Data are presented as ICC (95% confidence interval).

Interobserver reliability in the endoscopic identification of the few secondary parameters assessed was not satisfactory, however. ICC values for the length of hiatus hernia and the evaluation of the proportion (using 50% as the cut-point) of the esophageal circumference occupied by the tongue-like projections were 0.49 (95% CI, 0.32–0.67) and 0.25 (95% CI, 0.10–0.41), respectively. In the evaluation of erosive esophagitis, endoscopists identified presence of erosive esophagitis in 17.5% of the ratings, of which 10% had grade A, 4.1% had grade B, 2.8% had grade C, and 0.6% had grade D diseases [19]. Interobserver reliability was poor for rating of both the presence (ICC, 0.16; 95% CI, 0.05–0.26) and severity (ICC, 0.24; 95% CI, 0.01–0.47) of erosive esophagitis. Of 612 assessments of video quality, 9% were considered excellent, 39% were good, 39% were fair, and 13% were inadequate. In the 87% of ratings considered excellent to fair in quality, they showed Barrett’s segments with mean C and M values of 2.2 cm and 3.6 cm, respectively. However, the other 13% of the ratings which showed Barrett’s segments with mean C and M values of 0.8 cm and 1.8 cm, respectively, were considered technically inadequate for rating.

Endoscopic Landmark of Esophagogastric Junction

The proximal extent of the gastric folds could be identified in virtually all video clips. However, ring or pinch near the proximal end of the gastric folds and the distal end of palisade blood vessels could be recognized in only 50% and 48% of ratings, respectively; their corresponding ICC values were 0.25 (95% CI, 0.00–0.60) and 0.78 (95% CI, 0.61–0.95). When present, their locations differed from the top of gastric folds at most by 1 cm in 97% and 84% and differed at most by 2 cm in 99% and 93%, respectively.

Source of Variation in Rating

We performed analyses stratified by characteristics of the endoscopists and patients. At the region/country level, the ICC values ranged from 0.86 to 0.99 for the C value, 0.86 to 0.99 for the M value, 0.73 to 0.98 for the location of gastroesophageal junction, and 0.51 to 0.96 for the location of diaphragmatic hiatus (Table 1). Interobserver reliability for recognition and grading of these parameters ranged from good to excellent, except for the determination of the location of the diaphragmatic hiatus. Interobserver reliability was not dependent on the individual endoscopist’s experience, primary practice type or affiliated hospital’s volume of endoscopy procedures (details available upon request).

ICC values were related to the length of Barrett’s esophagus. As shown in Table 2 and Table 3, there were stepwise increases in the levels of the reliability coefficients when the cut-off values moved from <1 cm, ≤1 cm– <3 cm, and ≥3 cm, with the corresponding ICC values of 0.18 and 0.21, 0.46 and 0.44, and 0.86 and 0.90 for the C and M values, respectively. For Barrett’s esophagus ≥1 cm, the ICC values dramatically increased to 0.90 (95% CI, 0.80–1.00) and 0.92 (95% CI, 0.87–0.98) for the C and M values, respectively. These observations indicated that the interobserver reliability is optimal when Barrett’s esophagus segments of ≥1 cm are present.

Table 2.

Reliability coefficients stratified by the circumferential extents of the Barrett’s esophagus

| Average C value | Number of video clips | Reliability coefficients |

|---|---|---|

| <1 cm | 11 | 0.18 (0.03–0.32) |

| ≤ 1 cm– <3 cm | 3 | 0.46 (0.00–0.96) |

| ≥3 cm | 4 | 0.86 (0.66–1.00) |

| All | 18 | 0.92 (0.88–0.97) |

Data are presented as ICC (95% confidence interval).

The C values were dichotomized based on the mean values reported by the raters.

Table 3.

Reliability coefficients stratified by the maximum extents of the Barrett’s esophagus

| Average M value | Number of video clips | Reliability coefficients |

|---|---|---|

| <1 cm | 4 | 0.21 (0.00–0.51) |

| ≤ 1 cm– <3 cm | 7 | 0.44 (0.14–0.73) |

| ≥3 cm | 7 | 0.90 (0.80–1.00) |

| All | 18 | 0.94 (0.90–0.98) |

Data are presented as ICC (95% confidence interval).

The M values were dichotomized based on the mean values reported by the raters.

DISCUSSION

In this Asian multinational study, we have demonstrated excellent interobserver reliability in endoscopic grading of suspected Barrett’s esophagus using the Prague C & M Criteria. However, we found unacceptably low interobserver reliability for very short segment disease (<1 cm). Our results are consistent with that of a study which assessed the use of the Prague C & M Criteria for the endoscopic diagnosis and grading of Barrett’s esophagus. That study, which was conducted in Western countries, showed excellent interobserver reliability coefficients of 0.94, 0.93, 0.88, and 0.85 for the C value, M value, proximal end of the gastric folds, and diaphragmatic hiatus, respectively [18]. Moreover, as in that study, we similarly identified an abrupt drop in reliability coefficients when assessing videos with average C and M values of <1 cm. The consistency of this finding from both Western and Eastern countries suggests that the short segments of columnar epithelium are difficult to consistently diagnose [37–39].

Modification of pre-existing criteria is often required to fit the characteristics of the source population and the specific aim of a study. Thus, although Barrett’s esophagus has been traditionally stratified into long-segment and short-segment types with the cut-off value of 3 cm, this dichotomy can be challenged for its weakness in risk prediction [40,41] and its limited ability to provide consistency in interpretation, as our study showed. We therefore suggest that columnar epithelium <1 cm, which may have accounted for 70% of Asian patients with previously diagnosed Barrett’s esophagus [21], will prove challenging to study and should be excluded from studies which wish to ascertain as homogenous population as possible. The difficulties in reliably diagnosing columnar epithelium <1 cm also might have contributed to the diverse Barrett’s esophagus incidence trends reported in Asia [27–31].

Although we have confirmed the robustness of the landmarks used in the Prague C and M scoring system, some items are fraught with variability in interpretation. Firstly, the pinch or ring above the proximal end of the gastric folds is poorly identifiable, and should be excluded from the definition of esophagogastric junction, similar to the case of the distal end of the palisade blood vessels [42]. Our video clips were, however, recorded from Western patients with Barrett’s esophagus receiving routine medical care, in which the patient characteristics may not reflect the prevalence of different lengths of Barrett’s esophagus in the Asian populations. In our videos, long-segment disease and hiatus hernia are common, which may impair the identification of palisade blood vessels. In contrast, top of gastric folds may be attenuated in cases with Helicobacter pylori-related gastric atrophy, which is a prevalent feature in Asia [43,44]. Our endoscopic videos were not prepared with the idea of studying the palisade vessels, which are typically visualized by having the patients inhale and hold their breath while the endoscopist holds the endoscope at a single depth and examines distal esophagus for the distal extent of the palisade vessels. Because these videos were not prepared in such a way, this study was unable to validly compare the two methods for identification of the gastroesophageal junction. Further multinational prevalence studies based on recordings from Asian patients with Barrett’s esophagus are needed to elucidate this issue. Secondly, a substantial proportion of our videos probably showed a therapeutic effect related to acid suppressants, and this might have contributed to the poor reliability in the assessment of erosive changes in patients with mainly low-grade erosive disease. The result was in keeping with previous reliability studies based on either static images or video clips [20,45,46]. This may be a particular concern for studies conducted in Asia, since low-grade erosive disease is more common than high-grade erosive disease among Asians [47].

Lastly, the diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus requires histologic confirmation, a process which is also known to be affected by interobserver variability; the yield of intestinal metaplasia in endoscopically suspected Barrett’s esophagus is subject to the length of the columnar epithelium, number of biopsies, and the use of imaging enhanced endoscopy [41,48]. In the case of the C0Mx Barrett’s esophagus [21,23], a lesion which is thought to be much more prevalent in Asia compared with the West, inter-operator variation in histologic sampling may occur. Such speculation is supported by the finding of poor reliability in deciding the proportion of esophageal circumference occupied by the tongue-like projections in our study. Inter-observer variability in histological analysis, even among experienced pathologists, is another challenge in the final diagnosis of Barrett’s esophagus [49,50]. The Asian Barrett’s Consortium (ABC) is currently forming a workgroup to study reliability in the histologic diagnosis among its participating pathologists. In addition, further studies with the use of modern endoscopic technologies, such as chromoendoscopy, imaging enhanced endoscopy, endoscopic magnification, and confocal laser endomicroscopy, may realize accurate interpretation of the pit and vascular patterns of metaplasia <1 cm in extent, which may improve our reliability in recognition [51–53].

In conclusion, despite differences in endoscopic experience, volume of endoscopies performed at the respective affiliated institute, primary practice type, and residing country, endoscopists in our study can achieve a high/excellent level of interobserver reliability in endoscopically grading suspected Barrett’s esophagus following a well-structured, video-based training. Self-directed learning from the educational website is therefore encouraged for Asian endoscopists. In view of the low interobserver reliability in recognizing Barrett’s segment <1 cm, future definitions of disease for use in epidemiologic studies may have to take this into account.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the following collaborators: Chang-Qing Li, Tao Yu, Tao Zhou, Xiu-Li Zuo, Derek Jah-Yuen Luo, Larry Hin Lai, Akash Shukla, Nageshwar Reddy, Philip Abraham, Rupa Banerjee, Uday Chand Ghoshal, Kakunori Banno, Ryoji Miyahara, Takafumi Ando, Byung-Hoon Min, Hee-Jung Son, Jee-Eun Kim, Jun Haeng Lee, Andrea Rajnakova, Christopher Khor-Jen Lock, Jimmy So-Bok Yan, Khay-Guan Yeoh, Chien-Chuan Chen, Chi-Ming Tai, Ching-Tai Lee, Chi-Yang Chang, Ping-Huei Tseng, Wen-Lun Wang. The authors also thank the IWGCO for allowing use of the video clips.

Footnotes

Competing Interests: There is no conflict of interest.

The preliminary results were presented as an abstract (Journal of Gastroenterology and Hepatology 2009; 24 Suppl 4: A126) at the Asian Pacific Digestive Week Conference held from September 27 through September 30, 2009 in Taipei, Taiwan.

Specific Author Contributions: Yi-Chia Lee, Jennie Yiik-Yieng Wong, and Khek-Yu Ho were responsible for data collection, interpretation of the data, and drafting of the manuscript. Michael B. Cook was involved in the design and operation of the study and conducted the statistical analyses. The contributions of Shobna Bhatia, Hidemi Goto, Jaw-Town Lin, Yang-Qing Li, Poong-Lyul Rhee, Joseph Jao-Yiu Sung, and Justin Che-Yuen Wu involved the design and operation of the study, and interpretation of the data. Wong-Ho Chow, Emad M. El-Omar and Prateek Sharma contributed to conception and set-up of the Asian Barrett’s Consortium. All authors have critically revised the article and approved its submission.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sandler RS, Everhart JE, Donowitz M, et al. The burden of selected digestive diseases in the United States. Gastroenterology. 2002;122:1500–1511. doi: 10.1053/gast.2002.32978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Botterweck AA, Schouten LJ, Volovics A, Dorant E, van Den Brandt PA. Trends in incidence of adenocarcinoma of the oesophagus and gastric cardia in ten European countries. Int J Epidemiol. 2000;29:645–654. doi: 10.1093/ije/29.4.645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fléjou JF. Barrett's oesophagus: from metaplasia to dysplasia and cancer. Gut. 2005;54 Suppl 1:i6–i12. doi: 10.1136/gut.2004.041525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ho KY. Gastroesophageal reflux disease in Asia: a condition in evolution. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:716–722. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05380.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fernandes ML, Seow A, Chan YH, Ho KY. Opposing trends in incidence of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma in a multi-ethnic Asian country. Am J Gastroenterol. 2006;101:1430–1436. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.2006.00570.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yee YK, Cheung TK, Chan AO, Yuen MF, Wong BC. Decreasing trend of esophageal adenocarcinoma in Hong Kong. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2007;16:2637–2640. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-07-0421. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kusano C, Gotoda T, Khor CJ, et al. Changing trends in the proportion of adenocarcinoma of the esophagogastric junction in a large tertiary referral center in Japan. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;23:1662–1665. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2008.05572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Goh KL, Wong HT, Lim CH, Rosaida MS. Time trends in peptic ulcer, erosive reflux oesophagitis, gastric and oesophageal cancers in a multiracial Asian population. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2009;29:774–780. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2009.03930.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chung JW, Lee GH, Choi KS, et al. Unchanging trend of esophagogastric junction adenocarcinoma in Korea: experience at a single institution based on Siewert's classification. Dis Esophagus. 2009;22:676–681. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2009.00946.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen MJ, Lee YC, Chiu HM, Wu MS, Wang HP, Lin JT. Time trends of endoscopic and pathological diagnoses related to gastroesophageal reflux disease in a Chinese population: eight years single institution experience. Dis Esophagus. 2009 Sep 24; doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2009.01012.x. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lu CL, Lang HC, Luo JC, et al. Increasing trend of the incidence of esophageal squamous cell carcinoma, but not adenocarcinoma, in Taiwan. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21:269–274. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9458-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wu JC, Mui LM, Cheung CM, Chan Y, Sung JJ. Obesity is associated with increased transient lower esophageal sphincter relaxation. Gastroenterology. 2007;132:883–889. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.12.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moki F, Kusano M, Mizuide M, et al. Association between reflux oesophagitis and features of the metabolic syndrome in Japan. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2007;26:1069–1075. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2036.2007.03454.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chung SJ, Kim D, Park MJ, et al. Metabolic syndrome and visceral obesity as risk factors for reflux oesophagitis: a cross-sectional case-control study of 7078 Koreans undergoing health check-ups. Gut. 2008;57:1360–1365. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.147090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lee YC, Yen AM, Tai JJ, et al. The effect of metabolic risk factors on the natural course of gastro-oesophageal reflux disease. Gut. 2009;58:174–181. doi: 10.1136/gut.2008.162305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Asian Barrett’s Consortium Web Site. Asian Barrett’s Consortium’s statement concerning its research objectives and plans. [Cited Oct 5, 2009]; Available from URL: https://portals.dceg.cancer.gov/asianbarrett.

- 17.Armstrong D, Bennett JR, Blum AL, et al. The endoscopic assessment of esophagitis: a progress report on observer agreement. Gastroenterology. 1996;111:85–92. doi: 10.1053/gast.1996.v111.pm8698230. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharma P, Dent J, Armstrong D, et al. The development and validation of an endoscopic grading system for Barrett's esophagus: the Prague C & M criteria. Gastroenterology. 2006;131:1392–1399. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2006.08.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lundell LR, Dent J, Bennett JR, et al. Endoscopic assessment of oesophagitis: clinical and functional correlates and further validation of the Los Angeles classification. Gut. 1999;45:172–180. doi: 10.1136/gut.45.2.172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee YC, Lin JT, Chiu HM, et al. Intraobserver and interobserver consistency for grading esophagitis with narrow-band imaging. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;66:230–236. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.10.056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chang CY, Lee YC, Lee CT, et al. The application of Prague C and M Criteria in the diagnosis of Barrett's esophagus in an ethnic Chinese population. Am J Gastroenterol. 2009;104:13–20. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2008.43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akiyama T, Inamori M, Akimoto K, et al. Risk factors for the progression of endoscopic Barrett's epithelium in Japan: a multivariate analysis based on the Prague C & M Criteria. Dig Dis Sci. 2009;54:1702–1707. doi: 10.1007/s10620-008-0537-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hwang JK, Hong SG, Joo MK, et al. Application of Prague C & M Criteria to endoscopic description of CLE in Korea. Korean J Neurogastroenterol Motil. 2008;14 suppl 1:P10. [Article in Korean] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wong WM, Lam SK, Hui WM, et al. Long-term prospective follow-up of endoscopic oesophagitis in southern Chinese--prevalence and spectrum of the disease. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2002;16:2037–2042. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.2002.01373.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rosaida MS, Goh KL. Gastro-oesophageal reflux disease, reflux oesophagitis and non-erosive reflux disease in a multiracial Asian population: a prospective, endoscopy based study. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2004;16:495–501. doi: 10.1097/00042737-200405000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Sollano JD, Wong SN, Andal-Gamutan T, et al. Erosive esophagitis in the Philippines: a comparison between two time periods. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;22:1650–1655. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1746.2006.04355.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tseng PH, Lee YC, Chiu HM, et al. Prevalence and clinical characteristics of Barrett's esophagus in a Chinese general population. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2008;42:1074–1079. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e31809e7126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Okita K, Amano Y, Takahashi Y, et al. Barrett's esophagus in Japanese patients: its prevalence, form, and elongation. J Gastroenterol. 2008;43:928–934. doi: 10.1007/s00535-008-2261-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen X, Zhu LR, Hou KH. The characteristics of Barrett's esophagus: an analysis of 4120 cases in China. Dis Esophagus. 2009;22:348–353. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2008.00924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park JJ, Kim JW, Kim HJ, et al. H. pylori and GERD Study Group of Korean College of Helicobacter and Upper Gastrointestinal Research. The prevalence of and risk factors for Barrett's esophagus in a Korean population: A nationwide multicenter prospective study. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2009;43:907–914. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0b013e318196bd11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lee IS, Choi SC, Shim KN, et al. Prevalence of Barrett's esophagus remains low in the Korean population: nationwide cross-sectional prospective multicenter study. Dig Dis Sci. 2009 Oct 3; doi: 10.1007/s10620-009-0984-0. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Amano A, Kinoshita Y. Barrett esophagus: perspectives on its diagnosis and management in Asian populations. Gastroenterology & Hepatology. 2008;4:45–53. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Paris workshop on columnar metaplasia in the esophagus and the esophagogastric junction, Paris, France, December 11–12, 2004. Endoscopy. 2005;37:879–920. doi: 10.1055/s-2005-870305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.International Working Group for the Classification of Oesophagitis (IWGCO) Web Site. Interactive Prague Barrett's C&M Criteria. [Cited April 27, 2010]; Available from URL: http://iwgco.com/

- 35.Fleiss JL, Cohen J. The equivalence of weighted kappa and the intraclass correlation coefficient as measures of reliability. Educational and Psychological Measurement. 1973;33:613–619. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walter SD, Eliasziw M, Donner A. Sample size and optimal designs for reliability studies. Stat Med. 1998;17:101–110. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1097-0258(19980115)17:1<101::aid-sim727>3.0.co;2-e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Spechler SJ. Short and ultrashort Barrett's esophagus--what does it mean? Semin Gastrointest Dis. 1997;8:59–67. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Derakhshan MH, Malekzadeh R, Watabe H, et al. Combination of gastric atrophy, reflux symptoms and histological subtype indicates two distinct aetiologies of gastric cardia cancer. Gut. 2008;57:298–305. doi: 10.1136/gut.2007.137364. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shimoda T, Kushima R, Takizawa H. Pathological feature of esophagogastric adenocarcinoma. Stomach and Intestine (Tokyo) 2009;44:1083–1094. [Article in Japanese] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Sharma P, Morales TG, Sampliner RE. Short segment Barrett's segment: the need for standardization of the definition and of endoscopic criteria. Am J Gastroenterol. 1998;93:1033–1036. doi: 10.1111/j.1572-0241.1998.00324.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fujiyama Y, Ishizuka I, Koyama S. Histochemical diagnosis of short segment Barrett's esophagus. Nippon Rinsho. 2005;63:1420–1426. [Article in Japanese] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Amano Y, Ishimura N, Furuta K, et al. Which landmark results in a more consistent diagnosis of Barrett's esophagus, the gastric folds or the palisade vessels? Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:206–211. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kusano C, Kaltenbach T, Shimazu T, Soetikno R, Gotoda T. Can Western endoscopists identify the end of the lower esophageal palisade vessels as a landmark of esophagogastric junction? J Gastroenterol. 2009;44:842–846. doi: 10.1007/s00535-009-0083-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Amano Y, Ishimura N, Koshino K, et al. Endoscopic diagnosis of the esophagogastric junction. Stomach and Intestine (Tokyo) 2009;44:1065–1074. [Article in Japanese] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Amano Y, Ishimura N, Furuta K, et al. Interobserver agreement on classifying endoscopic diagnoses of nonerosive esophagitis. Endoscopy. 2006;38:1032–1035. doi: 10.1055/s-2006-944778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Miwa H, Yokoyama T, Hori K, et al. Interobserver agreement in endoscopic evaluation of reflux esophagitis using a modified Los Angeles classification incorporating grades N and M: a validation study in a cohort of Japanese endoscopists. Dis Esophagus. 2008;21:355–363. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2050.2007.00788.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hongo M. Minimal changes in reflux esophagitis: red ones and white ones. J Gastroenterol. 2006;41:95–99. doi: 10.1007/s00535-006-1775-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wani S, Sharma P. Endoscopic surface imaging of Barrett's esophagus: an optimistic view. Gastroenterology. 2007;133:11–13. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2007.05.062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Corley DA, Kubo A, DeBoer J, Rumore GJ. Diagnosing Barrett's esophagus: reliability of clinical and pathologic diagnoses. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:1004–1010. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.07.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Rubenstein JH. It takes two to tango: dance steps for diagnosing Barrett's esophagus. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:1011–1013. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Goda K, Tajiri H, Ikegami M, Urashima M, Nakayoshi T, Kaise M. Usefulness of magnifying endoscopy with narrow band imaging for the detection of specialized intestinal metaplasia in columnar-lined esophagus and Barrett's adenocarcinoma. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:36–46. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2006.03.938. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yoshida T, Shimizu Y, Kato M, et al. Advances in endoscopic diagnosis for Barrett's esophagus and adenocarcinoma: overview. Endoscopia Digestiva. 2009;21:1185–1198. [Article in Japanese] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chey WD, Sharma P. AGA Institute; 2010. Emerging imaging modalities to diagnose Barrett’s esophagus. Expert insights in IBS, constipation and acid-related disorders. [Google Scholar]