Abstract

The expression of an enzyme, GnT-V, that catalyzes a specific posttranslational modification of a family of glycoproteins, namely a branched N-glycan, is transcriptionally up-regulated during breast carcinoma oncogenesis. To determine the molecular basis of how early events in breast carcinoma formation are regulated by GnT-V, we studied both the early stages of mammary tumor formation by using 3D cell culture and a her-2 transgenic mouse mammary tumor model. Overexpression of GnT-V in MCF-10A mammary epithelial cells in 3D culture disrupted acinar morphogenesis with impaired hollow lumen formation, an early characteristic of mammary neoplastic transformation. The disrupted acinar morphogenesis of mammary tumor cells in 3D culture caused by her-2 expression was reversed in tumors that lacked GnT-V expression. Moreover, her-2-induced mammary tumor onset was significantly delayed in the GnT-V null tumors, evidence that the lack of the posttranslational modification catalyzed by GnT-V attenuated tumor formation. Inhibited activation of both PKB and ERK signaling pathways was observed in GnT-V null tumor cells. The proportion of tumor-initiating cells (TICs) in the mammary tumors from GnT-V null mice was significantly reduced compared with controls, and GnT-V null TICs displayed a reduced ability to form secondary tumors in NOD/SCID mice. These results demonstrate that GnT-V expression and its branched glycan products effectively modulate her-2-mediated signaling pathways that, in turn, regulate the relative proportion of tumor initiating cells and the latency of her-2-driven tumor onset.

Keywords: breast cancer, oncogene, N-glycosylation, morphogenesis, tumor initiating cells

The amplification and overexpression of her-2/erbB2, a member of the epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor family, play a pivotal role in the development of several different types of cancers, including breast carcinoma (1, 2). Oncogenesis observed in mouse mammary epithelia induced by her-2 expression shares similarities with that of human breast carcinoma (3). Her-2 signaling is activated through its interactions with other EGF family receptors after they bind ligands, including epidermal growth factor (EGF) and neuregulin (NRG) (4). Ligand-induced phosphorylation of this family of receptors recruits various docking proteins and signaling molecules that convey proliferative and survival signals via MAPK and PI3K/PKB pathways (5). In a reconstituted basement membrane culture system (3D culture), activation or overexpression of the her-2 receptor in a nontransformed mammary epithelial cell line (MCF-10A) elicits a multiacinar phenotype characterized by excessive cell proliferation and filling of the acinar luminal space that results from inhibited apoptosis and altered apicobasal polarization (6, 7). These in vitro alterations caused by her-2 overexpression are linked to the phenotypes observed for human breast ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) with erbB2 amplification (8). Recent studies have shown that her-2 regulates the mammary epithelial stem/progenitor cell population that drives tumorigenesis and progression (9, 10), and these tumor-initiating cells (TICs), also referred to as cancer stem cells, have been isolated and characterized from her-2-induced mouse mammary tumors (11, 12).

Changes in branched N-glycan structures on specific growth factor and adhesion receptors are associated with abnormal receptor-mediated signaling and resulting phenotypes (13, 14). A family of glycans whose expression is controlled by the ras-ets signaling pathway and is often up-regulated during malignant transformation is synthesized by the glycosyltransferase, N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase V (GnT-V, EC 2.4.1.155) (15, 16). Studies have implicated GnT-V in regulating tumorigenesis and invasiveness via modulation of the function of matriptase and several cell surface receptors, as well as in the progression of polyoma middle-T–induced mouse mammary carcinoma (17–23). Moreover, increased expression of the glycan products of GnT-V in human breast carcinoma is associated with poor prognosis (24).

The her-2 receptor is a glycoprotein with seven N-linked glycan sequons, and its function is likely to be affected by the action of GnT-V, as is EGFR (erbB1) function (22, 23). To determine whether GnT-V expression levels can regulate her-2–induced tumorigenesis, we studied both a her-2 transgenic mouse model of mammary carcinoma formation in a GnT-V null background and a mammary acinar formation observed during 3D culture of mammary epithelial and mammary carcinoma cells. The results demonstrate that GnT-V expression levels regulated the N-glycosylation of her-2 and her-2–induced signaling pathways, leading to a significantly altered proportion of TICs in the mammary tumors. As a result, the major effects of eliminating GnT-V expression on early stages of mammary tumorigenesis were the reversal of the disrupted mammary acinar formation caused by her-2 induction and significantly delayed onset of mammary carcinoma formation induced by her-2 expression.

Results

Overexpression of GnT-V Increased Cell Proliferation and Disrupted Mammary Acinar Morphogenesis.

Human mammary epithelial MCF-10A cells recapitulate several aspects of mammary epithelium organogenesis when grown in a reconstituted matrix (3D) culture, including the formation of polarized, acinar-like spheroids with hollow lumens and the basal deposition of basement components (collagen IV and Laminin V) (25). To determine the effects of altering GnT-V activity on early stages of tumor formation, we overexpressed GnT-V in MCF-10A cells by retroviral infection and observed greatly increased GnT-V activity and cell staining by L-PHA, which binds specifically its products, as expected (Fig. S1). Compared with control cells, GnT-V overexpressing cells showed increased cell proliferation in 2D culture (Fig. 1A), accompanied by increased phosphorylation of PKB and ERK (Fig. 1B). When grown in 3D culture (Fig. 1C), the control cells developed into small, regular acini, often with hollow lumens formation after 10–12 d; these lumens became more evident by day 15, as reported (6, 7). By contrast, the GnT-V–expressing cells developed into larger, asymmetric aggregates (multiacini), very often with cells filling the luminal space, a characteristic of the early neoplastic transformation of breast epithelium. Lumen formation by MCF-10A cells in 3D culture is mainly associated with the selective apoptosis of centrally located cells (7). Control cells showed apoptotic clearance of acinar lumens from day 8 to day 12 of 3D culture, detected by caspase-3 activation (cleaved caspase-3), whereas the activation of caspase-3, however, was significantly inhibited after expression of GnT-V (Fig. 2A and Fig. S2A). GnT-V expression also caused increased expression of Ki-67, a marker of proliferation, on both day 8 and day 11 (Fig. 2B and Fig. S2B), consistent with decreased apoptosis of luminal cells in 3D culture. In addition, control cells showed a delineated outer rim of Laminin V (LN-V) staining, indicating a well-organized acinar structure with apical/basal polarity (7), whereas GnT-V cells displayed stronger antibody staining for LN-V, not only in the outer layer, but even within the acinar structure, indicating increased deposition of LN-V and disrupted polarity (Fig. 2B). The structural changes in mammary acinar morphogenesis caused by GnT-V overexpression are similar to those of MCF-10A cells that express activated her-2 (erbB2) (6, 25) and, therefore, likely reflect early stages of mammary tumorigenesis.

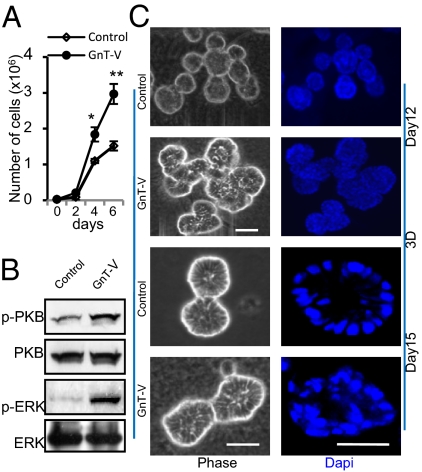

Fig. 1.

Increased expression of GnT-V stimulated cell proliferation and disrupted mammary acinar morphogenesis of MCF-10A cells in 3D culture. (A) Cells were grown on six-well plates and counted at each indicated time point and expressed as the mean ± SD of triplicate samples. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.001. (B) Cells were collected for detection of indicated proteins by immunoblot. (C) Cells were grown in 3D culture for 12 or 15 d. Nuclei (DNA) were stained with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole) and visualized by confocal microscopy. Images are representative of three independent experiments. (Scale bars: 25 μm.)

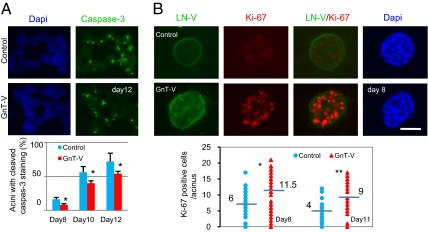

Fig. 2.

GnT-V overexpression increased proliferation and reduced sensitivity to anoikis during acinar morphogenesis of MCF-10A cells. (A) Cells were grown in 3D culture for the indicated times and stained for cleaved caspase-3. Graph shows percentages of acini with cleaved caspase-3 staining, which were calculated by counting the number of acini with or without cleaved caspase-3 staining in five different fields and expressed as the mean ± SD. (B) Cells were grown in 3D culture for 8 d and stained for LN-V (green), Ki-67 (red), and DAPI (blue). Graph shows number of Ki-67 positive cells per acinus on day 8 and day 11; 50–100 acini were scored in each group. -, median value; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.001. (Scale bar: 25 μm.)

Deletion of GnT-V Resulted in Both Inhibition of Mammary Tumor Onset Induced by her-2 and Reversal of Disrupted Acinar Morphogenesis.

To determine whether the dysregulation of acinar morphogenesis by GnT-V overexpression was mediated by erbB2 signaling, her-2 transgenic mice in which her-2 is expressed under the control of the mouse mammary tumor virus (MMTV) promoter (3) were bred with GnT-V null (KO) mice. Her-2 mice with wild-type (WT) GnT-V expression showed mammary tumor formation in 50% of the 24 mice by 58 wk (Fig. 3A). Her-2–induced tumor onset was significantly retarded, however, in GnT-V null mice, with 50% of these mice developing tumors by 68 wk (Fig. 3A). The median week of tumor onset was also remarkably increased after GnT-V deletion from 48 to 62 wk (Fig. 3B). Tumors from GnT-V KO mice showed a reduced tumor histological grade and reduced mitotic index compared with GnT-V WT mice (Fig. S3 A and B). Consistent with these results, immunochemical staining also showed reduced Ki-67 expression, increased cleaved caspase-3 staining of tumors with GnT-V deletion, and elimination of L-PHA binding, as expected, because of deletion of GnT-V, indicating inhibition of proliferation and induction of apoptosis in GnT-V KO tumors (Fig. S3C). The expression levels of her-2 in tumor tissues of both GnT-V WT and KO background were similar (Fig. S3D), indicating that the inhibition of tumor onset and tumor progression observed for the her-2/GnT-V KO mice was not due to suppression of total her-2 levels.

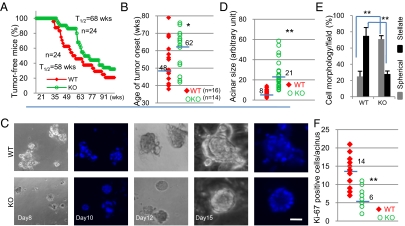

Fig. 3.

Tumor onset was inhibited and the disrupted acinar formation was reversed in her-2/GnT-V KO cells. (A) Kaplan–Meier curves were used to display the latency of her-2–induced mammary tumors in GnT-V WT and KO mice (P < 0.05). T1/2 represents the time point at which 50% of mice in that group developed tumors. (B) Median number of weeks for tumor onset for an individual mouse was calculated from each group of mice under 78 wk of age. (C) Cells were grown in 3D culture for indicated days and stained with DAPI. (D–F) Cells were grown in 3D culture for 10 d, individual acinar size was measured (D), cell morphology observed in five different fields was scored (E), and the Ki-67 positive cells per acinus were counted (F). Fifty to 100 acini were scored in each group. -, median value; *P < 0.05; **P < 0.001. (Scale bar: 25 μm.)

Primary mammary tumor cell lines were derived from her-2 tumors, and both growth factor-dependent (cultured with serum) and -independent (cultured without serum) cell growth were reduced in GnT-V KO cells detected by both a cell proliferation assay (Fig. S4A) and by cell cycle analysis (Table S1). Other her-2–induced phenotypes were also reduced in GnT-V KO tumor cells, including increased contact-inhibition and cell-cell adhesion (Fig. S4 B and C). When grown in 3D culture, the majority of GnT-V WT cells formed large multiacinar or stellate structures with filled lumens (Fig. 3 C–E), a typical morphology observed for her-2–expressing mammary epithelial cells (6). The majority of GnT-V KO cells, however, developed into much smaller spherical structures, some of which showed hollow lumen formation after day 15 of culture that was to some degree similar to the acinar formation of native MCF-10A cells grown in 3D culture (Fig. 1C). Consistent with reversed disruption of acinar structures, GnT-V KO cells showed decreased staining of Ki-67 in luminal spaces after day 10, compared with WT cells (Fig. 3F), indicating a suppression of cell proliferation during lumen formation. These results indicated that deletion of GnT-V inhibited cell proliferation and partially reversed her-2–induced disruption of acinar formation in 3D culture, which may both contribute to the delayed tumor onset observed in GnT-V null mice.

Tumors with GnT-V Deletion Showed a Reduced Proportion of TICs.

Recent studies have shown that only a relatively small percentage of primary tumor cells, called TICs, can efficiently form secondary tumors (26, 27). These cells show high activity of aldehyde dehydrogenase 1 (ALDH1), detected by the Aldefluor assay, and is widely used as a marker of many types of stem cells (9, 28, 29). The Aldefluor-positive cell population was remarkably reduced in primary tumors from GnT-V KO mice (0.87%) compared with GnT-V WT tumors (2.54%; Fig. 4A); similar results were observed for secondary tumors formed from GnT-V KO primary tumor cells (4.55%) compared with GnT-V WT cells (8.37%; Fig. S5A), indicating a significantly reduced TIC population in the absence of GnT-V expression. A reduced TIC population in GnT-V KO cells was further confirmed by an assay for TICs based on their ability to exclude a vital dye, Hoechst 33342 (28). Using this assay, the GnT-V KO tumors showed a significantly reduced population of 0.62% (Fig. S5B) compared with WT (5.64%). Moreover, after prior depletion of lineage-positive (Lin+) cells, the Lin−/GnT-V KO tumor cells displayed a reduced Scal−/CD24+ population (9.05%) compared with Lin−/GnT-V WT tumor cells (68.7%; Fig. 4B). The TICs mainly arise from this Scal−/CD24+ population, which represent transformed luminal precursor cells, and show the highest ability to initiate secondary tumors when injected into NOD/SCID hosts (11). A reduction in this cell population is consistent with the delayed her-2–induced tumor onset observed in the GnT-V KO mice. If GnT-V expression levels regulated the TIC population size in her-2–induced mammary tumors, then GnT-V levels would likely also have an effect on the nontransformed mammary gland stem cell population. Analysis of the MCF-10A cells with GnT-V overexpression revealed a significantly increased proportion of TICs (0.83%) compared with control cells (0.12%; Fig. S5C), supporting the ability of GnT-V levels to regulate the size of the TIC compartment.

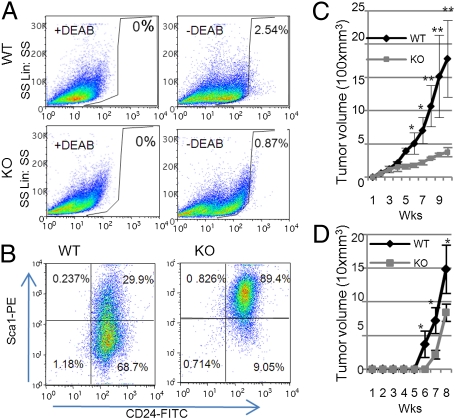

Fig. 4.

Her-2–induced GnT-V KO tumors displayed a reduced population of TICs and decreased secondary tumor formation in NOD/SCID mice. (A) Aldefluor assays were performed by using tumor cells isolated from primary tumors, and the percentage of Aldefluor-positive cells was determined under similar gating criteria. Data are representative of two independent experiments. (B) Lin− epithelial cells purified from either WT or KO tumor cells were analyzed by flow cytometry with labeled Sca1 and CD24 antibodies to identify Sca1−/CD24+ populations. Data are representative of two independent experiments. (C) Primary tumor cells (1 × 106) were injected into No. 4 mammary fat pads of NOD/SCID mice (n = 5), and secondary tumor growth was observed up to 10 wk. Tumor volume was measured and expressed as the mean ± SD. (D) Aldefluor-positive cells (103) were sorted from secondary tumor tissues formed by implantation of either WT or KO cells and were then injected into No. 4 mammary fat pads of NOD/SCID mice (n = 3). Tumor formation was observed for 8 wk. *P < 0.05; **P < 0.005.

Consistent with a reduced cell population of TICs in GnT-V KO cells, secondary tumor growth in NOD/SCID mice was significantly slower for the GnT-V KO cells (Fig. 4C). The secondary tumors formed by injection of GnT-V WT cells invaded beyond the boundaries of the mammary fat pad into skeletal muscle; by contrast, the GnT-V KO cells showed little invasion (Fig. S6). To compare the tumor forming ability of TICs from GnT-V KO and GnT-V WT tumors, the same number of TICs (103 cells) were sorted from tumors and injected into mammary fat pads of NOD/SCID mice. Tumor formation was significantly delayed in those mice that received GnT-V null TICs (Fig. 4D), suggesting that GnT-V deletion resulted in defects in self-renewal of TICs or their proliferative ability (28).

Deletion of GnT-V Inhibited her-2–Induced Oncogenic Signaling Pathways.

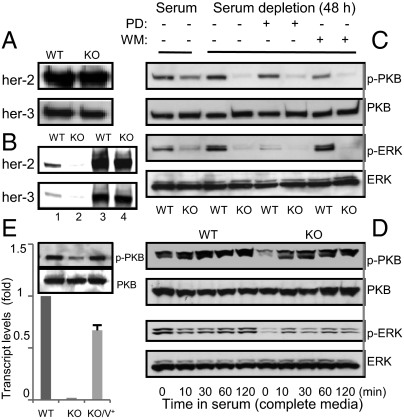

To determine the mechanisms whereby deletion of GnT-V led to the reduced proportion of TICs, the expression and glycosylation of her-2 and its downstream signaling pathways were investigated. Recent studies have implicated her-2 signaling pathways in the regulation of TICs (9, 10). The levels of her-2 were not significantly affected by deletion of GnT-V in both primary tumor cells (Fig. 5A) and Aldefluor-positive TICs (Fig. S7A). The expression levels of the glycans synthesized by GnT-V on her-2, however, were eliminated in GnT-V KO cells (Fig. 5B, lane 1 and 2), detected by L-PHA precipitation, as expected, indicating that N-glycosylation of her-2 was clearly affected by deletion of GnT-V. When grown in complete culture media, GnT-V WT tumor cells showed higher levels of both p-PKB and p-ERK compared with GnT-V KO cells (Fig. 5C). Depletion of serum for 48 h had no effect on the levels of both p-PKB and p-ERK in WT cells, consistent with her-2–induced growth factor-independent cell proliferation (Table S1), but depletion significantly lowered levels of p-PKB and p-ERK in the GnT-V KO cells. When treated with either PD98059 or wortmannin, inhibitors of MAPK and PI3K/PKB signaling pathways, respectively, increased phosphorylation of ERK and PKB observed in the GnT-V WT cells was significantly reduced. Inhibited activation of both PKB and ERK caused by elimination of GnT-V was further confirmed by stimulating cells, grown in serum-free media, with serum (Fig. 5D) or growth factors, including EGF and neuregulins (NRG) (Fig. S7 B and C). When GnT-V cDNA was transiently reintroduced into GnT-V KO cells, the levels of p-PKB inhibited relative to control cells were significantly rescued (Fig. 5E), strengthening the conclusion that the inhibition of her-2–induced signaling pathways in the GnT-V KO tumor cells was due to the lack of GnT-V expression. It is likely that aberrant glycosylation of her-2, and likely other erbB family receptors, inhibited her-2–mediated signaling pathways, leading to a reduced proportion of TICs and, therefore, a delay in the onset of her-2–induced tumor formation.

Fig. 5.

Deletion of GnT-V inhibited her-2–mediated downstream signaling pathways. (A) Cell surface proteins were labeled with NHS-LC-biotin, followed by streptavidin immunoprecipitation (IP). Precipitated proteins were subjected to detection of indicated proteins by immunoblot. (B) Cells were lysed for L-PHA IP, and both precipitated L-PHA bound proteins (lane 1 and 2) and cell lysates (used as control, lane 3 and 4) were subjected to detection of indicated proteins by immunoblot. (C) Cells grown either in serum-containing or serum-free media for 2 d with or without PD98059 (PD, 20 μM) or wortmannin (WM, 200 nM) were collected for detection of indicated proteins by immunoblot. (D) Cells grown in serum-free media for 2 d were stimulated with complete growth media for indicated times and collected for detection of indicated proteins by immunoblot. (E) GnT-V KO cells transiently transfected with GnT-V cDNA (KO/V+) were collected for determination of GnT-V transcripts by qRT-PCR (Lower) and immunoblot for detection of indicated proteins (Upper).

Discussion

Our results document that the expression levels of GnT-V–regulated acinar luminal formation, which is linked to early neoplastic transformation of mammary epithelium, and affected her-2–induced tumor onset via modulating the population of TICs. We found that overexpression of GnT-V in MCF-10A cells increased cell proliferation and cell survival by inhibiting anoikis of luminal cells, which led to the disruption of mammary acinar morphogenesis with impaired (filled) lumen formation, as well as enhanced LN-V deposition around and within the acini. These results link an alteration of enzyme expression and activity, which often occurs during oncogenic transformation and mammary tumorigenesis, directly to a morphological alteration (filled acinar lumens). Activated PKB and ERK signaling and aberrant mammary acinar morphogenesis of MCF-10A cells caused by GnT-V overexpression were similar, to a large extent, to that observed for MCF-10A cells with erbB2 activation (6), suggesting that dysregulation of acinar morphogenesis caused by GnT-V overexpression likely results from regulating the signaling of the erbB2 receptor. To test this hypothesis, the her-2 mouse mammary tumor model was used and revealed that elimination of GnT-V expression significantly delayed her-2–induced tumor onset. Our results are consistent with an earlier study using mice expressing the polyoma middle-T antigen in mammary epithelia, which showed a delay of tumor formation after deletion of GnT-V (17).

Consistent with delayed tumorigenesis, her-2 tumor cells isolated from tumor tissues of GnT-V KO mice showed reduced malignancy-related phenotypes. Significantly, when these tumor cells were grown in 3D culture, her-2–induced dysregulation of mammary acinar morphology was partially reversed in GnT-V KO cells. These results corroborate those obtained from MCF-10A cells with GnT-V overexpression and strongly suggest that GnT-V levels can regulate mammary acinar morphogenesis via her-2 signaling pathway by either stimulating or attenuating signaling. Inhibition of her-2–driven tumor onset in the GnT-V KO mice may result, at least in part, from reversal of disrupted acinar morphogensis caused by overexpression of her-2 oncoprotein.

Recent studies have highlighted the importance of stem cell-like TICs in regulating mammary tumorigenesis and progression (12, 29, 30). We found that the population of TICs was significantly decreased in both GnT-V null primary and secondary tumor cells. Supporting this finding, the proportion of TICs was significantly increased in MCF-10A cells with overexpression of GnT-V, indicating the regulation of the proportion of TICs by GnT-V expression levels, and the involvement of the reduced proportion of TICs in increasing the time of onset of her-2–induced tumor formation. Coincident with these results, secondary tumor formation in NOD/SCID mice injected with GnT-V KO cells was significantly suppressed, confirming the hypothesis that the reduced proportion of TICs is a primary cause of the GnT-V–dependent inhibition of mammary tumor formation. The inhibition of secondary tumor formation in NOD/SCID mice injected with TICs isolated from GnT-V KO tumors indicated that self-renewal and proliferation of TICs may likely be affected by deletion of GnT-V. Studies have demonstrated that mammary stem cells can form mammary acini in 3D culture and mammospheres in suspension culture (9, 31), whereas differentiated mammary epithelial cells undergo apoptosis (anoikis), similar to those located in acinar lumens in 3D culture. TICs have, therefore, the ability to survive and proliferate in an anchorage-independent way through mammosphere formation, probably contributing to the disrupted mammary acinar morphology with filled lumens observed in her-2–induced mammary tumor. Deletion of GnT-V resulted in a reduced TIC population, therefore lessening the disruption of acinar morphology by her-2 expression. However, changes in the proportion of mammary TICs during tumor formation affect the mammary bipotent progenitor population that expresses both luminal and basal epithelial markers, changing the differentiation status of mammary tumors (29). The reduced TIC population observed in GnT-V null tumors may, therefore, result in defective bipotent progenitor cells, leading to reduced malignant phenotypes (Fig. 4 C and D).

Several signaling pathways regulate stem cell self-renewal, including activation of her-2 (9, 10, 32, 33). Our findings suggest that deletion of GnT-V expression contributed to suppression of her-2–induced tumorigenesis by impairing the two her-2–mediated signaling pathways, PI3K/PKB and MAPK (5). Most importantly, aberrant signaling pathways could be corrected by reintroduction of GnT-V cDNA into GnT-V KO cells, demonstrating a direct involvement of GnT-V expression levels in regulating her-2–mediated signaling pathways. The reduced population of TICs in GnT-V KO tumors, therefore, most likely resulted from attenuated her-2–mediated signaling, thereby affecting her-2–mediated acinar morphogenesis and tumor development. However, the involvement of other signaling pathways in regulating the TIC population in GnT-V KO cells cannot be ruled out because of the ability of GnT-V glycan products to modify the function of multiple glycoproteins. We found that deletion of GnT-V had no significant effect on expression levels of her-2 but did cause the suppression of the expression of N-linked β(1,6) branching on the her-2 oncoprotein. The attenuation of her-2–mediated signaling pathways observed in GnT-V KO tumor cells is likely to be the result of the aberrant N-glycosylation of her-2 and/or the erbB family of receptors, which can lead to altered ligand (EGF and NRG) binding, regulation of the endocytosis of signaling complexes, and/or inhibition of dimer and multimer formation among members of this family (22, 23, 34).

Increased GnT-V expression and aberrantly glycosylated glycoproteins in human breast carcinomas is associated with poor prognosis (24), which is a likely consequence of decreased tumor cell-cell and cell-matrix adhesion driven by increased growth factor receptor signaling. In the light of our results showing that GnT-V can regulate the proportion of TICs in mammary carcinomas, the association of lower survival rates for patients with breast tumors that show high GnT-V expression may also be due to increased levels of TICs in these tumors.

Materials and Methods

Three-Dimensional Cell Culture (3D Culture).

Three-dimensional culture was performed as described (25) using growth factor-reduced matrigel (BD Biosciences). Cells were grown to confluence, trypsinized, and resuspended in assay medium [DMEM/F12 supplemented with horse serum (2%), hydrocortisone (0.5 μg/mL), cholera toxin (100 ng/ml), insulin (10 μg/mL), EGF (5 ng/mL), matrigel (2%), and Pen/Strep] at 2.5 × 104 cells per mL. Cells were embedded into matrigel-coated chamber-slides and grown for 8–15 d with replacement of fresh assay medium every 4 d.

Mouse Breeding.

GnT-V null mice (C57) have been described (17). MMTV-her-2 transgenic mice (FVB) were purchased from The Jackson Laboratory. Her-2(+/−)/GnT-V(+/−) mice in a FVB/C57 background were generated by breeding her-2(+/+) mice with GnT-V(−/−) mice; differences in mammary tumor formation between FVB/C57 and FVB backgrounds have been noted (3). Her-2/GnT-V(+/+) and her-2/GnT-V(−/−) mice were produced by mating male her-2(+/−)/GnT-V(+/−) mice and female her-2(+/−)/GnT-V(+/−) mice. All mice were genotyped by tail PCR as described (3, 20).

Detailed descriptions of additional methods are provided in SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the National Cancer Institute and Dr. Joan Brugge, Harvard Medical School, for providing H.-B.G. the opportunity to learn 3D culture techniques, as well as the MCF-10A cells and the pBabe retroviral plasmid. We also thank Julie Nelson and Xiaoping Yin for assistance with flow cytometry and statistical analysis, respectively, and Drs. Bing Zhang, Jin-Kyu Lee, and Karen Abbott for informative discussions. This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health Grants CA64462, CA128454, and RR018502 to M.P.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1013405107/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Carlsson J, et al. HER2 expression in breast cancer primary tumours and corresponding metastases. Original data and literature review. Br J Cancer. 2004;90:2344–2348. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6601881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ménard S, et al. HER2 overexpression in various tumor types, focussing on its relationship to the development of invasive breast cancer. Ann Oncol. 2001;12(Suppl 1):S15–S19. doi: 10.1093/annonc/12.suppl_1.s15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guy CT, et al. Expression of the neu protooncogene in the mammary epithelium of transgenic mice induces metastatic disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1992;89:10578–10582. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.22.10578. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sorkin A, Goh LK. Endocytosis and intracellular trafficking of ErbBs. Exp Cell Res. 2009;315:683–696. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2008.07.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Holbro T, Civenni G, Hynes NE. The ErbB receptors and their role in cancer progression. Exp Cell Res. 2003;284:99–110. doi: 10.1016/s0014-4827(02)00099-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Muthuswamy SK, Li D, Lelievre S, Bissell MJ, Brugge JS. ErbB2, but not ErbB1, reinitiates proliferation and induces luminal repopulation in epithelial acini. Nat Cell Biol. 2001;3:785–792. doi: 10.1038/ncb0901-785. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Debnath J, et al. The role of apoptosis in creating and maintaining luminal space within normal and oncogene-expressing mammary acini. Cell. 2002;111:29–40. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)01001-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hynes NE, Stern DF. The biology of erbB-2/neu/HER-2 and its role in cancer. Biochim Biophys Acta. 1994;1198:165–184. doi: 10.1016/0304-419x(94)90012-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Korkaya H, Paulson A, Iovino F, Wicha MS. HER2 regulates the mammary stem/progenitor cell population driving tumorigenesis and invasion. Oncogene. 2008;27:6120–6130. doi: 10.1038/onc.2008.207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Nakanishi T, et al. Side-population cells in luminal-type breast cancer have tumour-initiating cell properties, and are regulated by HER2 expression and signalling. Br J Cancer. 2010;102:815–826. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605553. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Liu JC, Deng T, Lehal RS, Kim J, Zacksenhaus E. Identification of tumorsphere- and tumor-initiating cells in HER2/Neu-induced mammary tumors. Cancer Res. 2007;67:8671–8681. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-07-1486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cao Y, Luo JL, Karin M. IkappaB kinase alpha kinase activity is required for self-renewal of ErbB2/Her2-transformed mammary tumor-initiating cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:15852–15857. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706728104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hakomori S. Carbohydrate-to-carbohydrate interaction in basic cell biology: A brief overview. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2004;426:173–181. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.02.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhao YY, et al. Functional roles of N-glycans in cell signaling and cell adhesion in cancer. Cancer Sci. 2008;99:1304–1310. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.2008.00839.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Brockhausen I, Carver JP, Schachter H. Control of glycoprotein synthesis. The use of oligosaccharide substrates and HPLC to study the sequential pathway for N-acetylglucosaminyltransferases I, II, III, IV, V, and VI in the biosynthesis of highly branched N-glycans by hen oviduct membranes. Biochem Cell Biol. 1988;66:1134–1151. doi: 10.1139/o88-131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hakomori S. Glycosylation defining cancer malignancy: New wine in an old bottle. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:10231–10233. doi: 10.1073/pnas.172380699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Granovsky M, et al. Suppression of tumor growth and metastasis in Mgat5-deficient mice. Nat Med. 2000;6:306–312. doi: 10.1038/73163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ihara S, et al. Prometastatic effect of N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase V is due to modification and stabilization of active matriptase by adding beta 1-6 GlcNAc branching. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:16960–16967. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M200673200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo HB, Lee I, Kamar M, Akiyama SK, Pierce M. Aberrant N-glycosylation of beta1 integrin causes reduced alpha5beta1 integrin clustering and stimulates cell migration. Cancer Res. 2002;62:6837–6845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo HB, Lee I, Kamar M, Pierce M. N-acetylglucosaminyltransferase V expression levels regulate cadherin-associated homotypic cell-cell adhesion and intracellular signaling pathways. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:52412–52424. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M308837200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Vagin O, Tokhtaeva E, Yakubov I, Shevchenko E, Sachs G. Inverse correlation between the extent of N-glycan branching and intercellular adhesion in epithelia. Contribution of the Na,K-ATPase beta1 subunit. J Biol Chem. 2008;283:2192–2202. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704713200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Partridge EA, et al. Regulation of cytokine receptors by Golgi N-glycan processing and endocytosis. Science. 2004;306:120–124. doi: 10.1126/science.1102109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Guo HB, Johnson H, Randolph M, Lee I, Pierce M. Knockdown of GnT-Va expression inhibits ligand-induced downregulation of the epidermal growth factor receptor and intracellular signaling by inhibiting receptor endocytosis. Glycobiology. 2009;19:547–559. doi: 10.1093/glycob/cwp023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Handerson T, Camp R, Harigopal M, Rimm D, Pawelek J. Beta1,6-branched oligosaccharides are increased in lymph node metastases and predict poor outcome in breast carcinoma. Clin Cancer Res. 2005;11:2969–2973. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-04-2211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Debnath J, Muthuswamy SK, Brugge JS. Morphogenesis and oncogenesis of MCF-10A mammary epithelial acini grown in three-dimensional basement membrane cultures. Methods. 2003;30:256–268. doi: 10.1016/s1046-2023(03)00032-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Al-Hajj M, Clarke MF. Self-renewal and solid tumor stem cells. Oncogene. 2004;23:7274–7282. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ponti D, Zaffaroni N, Capelli C, Daidone MG. Breast cancer stem cells: An overview. Eur J Cancer. 2006;42:1219–1224. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2006.01.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Charafe-Jauffret E, et al. Cancer stem cells in breast: Current opinion and future challenges. Pathobiology. 2008;75:75–84. doi: 10.1159/000123845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Luo M, et al. Mammary epithelial-specific ablation of the focal adhesion kinase suppresses mammary tumorigenesis by affecting mammary cancer stem/progenitor cells. Cancer Res. 2009;69:466–474. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-3078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Al-Hajj M, Wicha MS, Benito-Hernandez A, Morrison SJ, Clarke MF. Prospective identification of tumorigenic breast cancer cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:3983–3988. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0530291100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dontu G, et al. In vitro propagation and transcriptional profiling of human mammary stem/progenitor cells. Genes Dev. 2003;17:1253–1270. doi: 10.1101/gad.1061803. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dontu G, et al. Role of Notch signaling in cell-fate determination of human mammary stem/progenitor cells. Breast Cancer Res. 2004;6:R605–R615. doi: 10.1186/bcr920. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Liu S, et al. Hedgehog signaling and Bmi-1 regulate self-renewal of normal and malignant human mammary stem cells. Cancer Res. 2006;66:6063–6071. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-0054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Yokoe S, et al. The Asn418-linked N-glycan of ErbB3 plays a crucial role in preventing spontaneous heterodimerization and tumor promotion. Cancer Res. 2007;67:1935–1942. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-3023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.