Abstract

The activity of G protein-coupled receptors is regulated via hyper-phosphorylation following agonist stimulation. Despite the universal nature of this regulatory process, the physiological impact of receptor phosphorylation remains poorly studied. To address this question, we have generated a knock-in mouse strain that expresses a phosphorylation-deficient mutant of the M3-muscarinic receptor, a prototypical Gq/11-coupled receptor. This mutant mouse strain was used here to investigate the role of M3-muscarinic receptor phosphorylation in the regulation of insulin secretion from pancreatic islets. Importantly, the phosphorylation deficient receptor coupled to Gq/11-signaling pathways but was uncoupled from phosphorylation-dependent processes, such as receptor internalization and β-arrestin recruitment. The knock-in mice showed impaired glucose tolerance and insulin secretion, indicating that M3-muscarinic receptors expressed on pancreatic islets regulate glucose homeostasis via receptor phosphorylation-/arrestin-dependent signaling. The mechanism centers on the activation of protein kinase D1, which operates downstream of the recruitment of β-arrestin to the phosphorylated M3-muscarinic receptor. In conclusion, our findings support the unique concept that M3-muscarinic receptor-mediated augmentation of sustained insulin release is largely independent of G protein-coupling but involves phosphorylation-/arrestin-dependent coupling of the receptor to protein kinase D1.

Keywords: G-protein coupled receptor, ligand bias

The vast majority of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) respond to agonist occupation by becoming rapidly hyper-phosphorylated within intracellular domains (1–3). This process not only leads to the uncoupling of the receptor from its cognate G proteins, but also allows for the activation of G protein-independent signaling, a process that is driven largely by the recruitment of β-arrestin adaptor proteins (4–7). As a consequence, GPCRs regulate an extensive array of signaling pathways and biological responses (3). G protein-independent signaling pathways have mostly been studied in recombinant systems. However, the current challenge is to understand to what extent these processes are involved in the regulation of key physiological responses.

In the present study, we examined the in vivo role of GPCR phosphorylation by generating a knock-in mouse strain expressing a phosphorylation-deficient GPCR. Specifically, we used the M3-muscarinic acetylcholine receptor, a prototypic Gq/11-coupled GPCR, as a model system (8, 9). We and others have previously demonstrated that the M3-muscarinic receptor is rapidly phosphorylated on agonist occupation by a range of protein kinases that include members of the GPCR kinase (GRK) family, as well as casein kinase 1α and protein kinase CK2 (10–13). To define the potential physiological role of M3-muscarinic receptor phosphorylation, we generated a mouse strain where the wild-type M3-muscarinic receptor gene had been replaced by a phosphorylation-deficient mutant form of the receptor. Using this mouse model, we have recently demonstrated an important role for receptor phosphorylation and β-arrestin signaling in muscarinic receptor-mediated hippocampal memory and learning (14). In the present study we focus on the role of M3-muscarinic receptor phosphorylation in the regulation of glucose-dependent insulin release from pancreatic islets, a response that is known to be augmented by parasympathetic pathways acting on M3-muscarinic receptors expressed on pancreatic β-cells (15–17). Our results demonstrate that the M3-muscarinic receptor-stimulated increase in insulin release is mediated, at least in part, by receptor phosphorylation/arrestin signaling. This mechanism is independent of heterotrimeric G proteins and, rather, is mediated by β-arrestin activation of protein kinase D1 (PKD1).

Results

Characterization of a Phosphorylation-Deficient Mutant M3-Muscarinic Receptor.

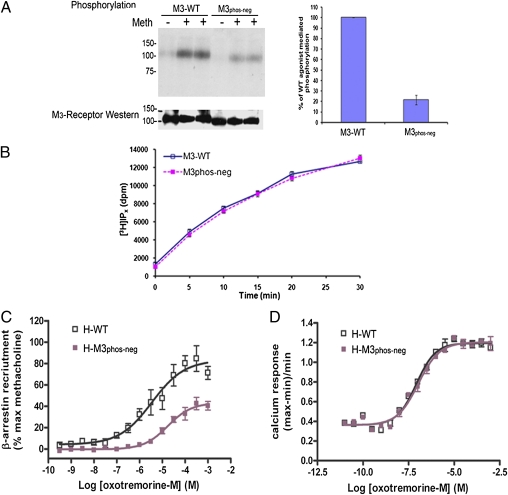

Our previous studies on the human M3-muscarinic receptor have established that the receptor is phosphorylated on multiple serines within the third intracellular loop (10, 12). In the present study, mutation of 15 of these serine residues to alanine in the mouse M3-muscarinic receptor resulted in a receptor (termed M3phos-neg) (Fig. S1A), showing an ∼80% reduction in agonist-mediated phosphorylation in transfected CHO cells, as compared with the wild-type receptor (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Characterization of a phosphorylation-deficient M3-muscarinic receptor mutant (M3phos-neg). (A) CHO cells were stably transfected with the wild-type mouse M3-muscarinic receptor (M3-WT) or with the phosphorylation-deficient receptor mutant M3phos-neg. Cells were metabolically labeled with [32P]orthophosphate and exposed to the agonist methacholine (Meth, 100 μM) for 5 min. Cells were then solubilized and the M3-muscarinic receptor immunoprecipitated and resolved by SDS/PAGE. The gel was transferred to nitrocelluose and an autoradiograph obtained. The nitrocellulose membrane was then subjected to Western blotting with an M3-receptor antibody to determine equal receptor loading. The bar diagram summarizes the data from three experiments (mean ± SE). (B) Transfected CHO cells were metabolically labeled with [3H]inositol and stimulated for the indicated times with methacholine (100 μM). The accumulation of [3H]inositol phosphates was then determined as described in SI Materials and Methods. (C and D) PathHunter CHO-K1 cells expressing either the wild-type human M3-muscarinic receptor (H-WT) or the phosphorylation-deficient human M3-muscarinic receptor (H-M3phos-neg) were used to generate concentration response curves to the full muscarinic receptor agonist oxotremorine-M in the (C) PathHunter β-arrestin recruitment assay and (D) calcium mobilization assays. The graphical data presented are means ± SE of at least three independent experiments. The autoradiographs are representative of at least three independent experiments.

Importantly, the M3phos-neg receptor was trafficked to the cell surface normally, as determined in radioligand binding studies using the hydrophyllic muscarinic receptor ligand [3H]-n-methyl scopolamine ([3H]-NMS) [Bmax for wild-type = 294 ± 24 fmoles/mg protein and for M3phos-neg Bmax = 293 ± 28 fmoles/mg protein (mean ± SE, n = 4)]. Immunoprecipitation of biotin-labeled cell-surface M3-muscarinic receptors further confirmed the cell-surface localization of the M3phos-neg (Fig. S1B).

The M3phos-neg receptor was also functionally coupled to the phospholipase C pathway in a manner similar to the wild-type receptor, as determined in phosphoinositide (PI) hydolysis assays (Fig. 1B).

Our recent studies established that removal of the phosphorylation sites on the M3-muscarinic receptor resulted in a deficit in the recruitment of β-arrestin (14). This result was confirmed here using the PathHunter β-arrestin recruitment assay and the human M3-muscarinic receptor containing comparable phospho-acceptor site mutations to that of the mouse receptor. The phosphorylation-deficient receptor showed a rightward shift in the concentration response curve to the full muscarinic receptor agonist oxotremorine-M, and a reduction in maximal β-arrestin recruitment (Fig. 1C) [EC50 for β-arrestin recruitment to the wild-type receptor = −5.22 ± 0.29 M(log10) and to the phosphorylation-deficient receptor = −4.35 ± 0.37 M(log10)]. Consistent with the studies described above, calcium assays demonstrated that the phosphorylation-deficient mutant receptor coupled with the same efficacy and potency as the wild-type receptor to Gq/11-mediated calcium mobilization (Fig. 1D).

Generation and Characterization of a Knock-In Mouse Strain Expressing the Phosphorylation-Deficient M3-Muscarinic Receptor.

To test the physiological role of M3-muscarinic receptor phosphorylation, we generated a knock-in mouse strain via homologous recombination that replaced the coding sequence of the wild-type M3-muscarinic receptor with that of the phosphorylation-deficient, M3phos-neg receptor (14). We have previously reported that homozygous mice for this gene-targeting event (designated M3R-KI) displayed no gross physiological defects and showed normal Mendelian breeding (14). Furthermore, the weight and food consumption of the M3R-KI mice was not significantly different from wild-type animals (Fig. S2).

Ligand binding analysis of peripheral tissues known to express predominantly the M3-muscarinic receptor (salivary submandibular glands and pancreatic islets) demonstrated that muscarinic receptor expression was at comparable levels in the wild-type and homozygous M3R-KI animals (Fig. S3 A and B). Furthermore, immunoprecipitation of the M3-muscarinic receptor from pancreatic extracts with an in-house rabbit polyclonal receptor antibody followed by Western blot analysis with a receptor-specific mouse monoclonal antibody revealed that the M3R-KI receptor was expressed at normal levels in the pancreas (Fig. S3C).

The phosphorylation status of the M3-muscarinic receptor was determined in cerebellar granule neurons derived from wild-type and M3R-KI animals. These experiments established that the mutated receptor was expressed at normal levels in cerebellar granule neurons (Fig. S3D) but was reduced in its ability to be phosphorylated in response to agonist-occupation by 67.9 ± 5.8% when compared with wild-type control neurons (Fig. S3D).

Signaling Properties of the Phosphorylation-Deficient M3-Muscarinic Receptor in Pancreatic Islets.

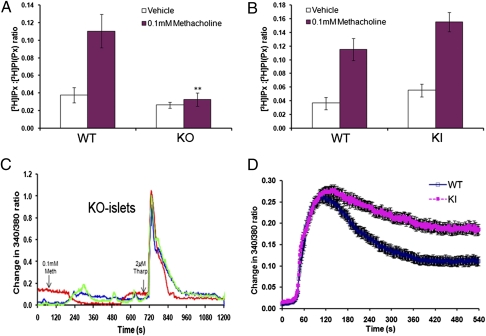

The M3-muscarinic receptor is coupled via Gq/11-proteins to the phosphoinositide/calcium mobilization pathway (8). To examine receptor coupling to this pathway in isolated pancreatic islets, we carried out a series of PI hydrolysis assays. The observed methacholine-stimulated production of [3H]inositol phosphates in islets from wild-type mice was completely absent in islets from whole-body M3-muscarinic receptor knock-out animals (Fig. 2A), indicating that this response is exclusively mediated by M3-muscarinic receptors. Methacholine stimulation of islets from M3R-KI mice gave a PI response similar to that observed with wild-type islets (Fig. 2B), demonstrating that the mutant receptor couples normally to Gq/11 in pancreatic islets.

Fig. 2.

Analysis of the muscarinic signaling properties of pancreatic islets from wild-type and M3R-KI mice. (A and B) Pancreatic islets isolated from wild type (WT), M3R-KI (KI), or M3-muscarinic receptor knockout (KO) mice were labeled with myo-[3H]inositol and stimulated with methacholine (100 μM) in Krebs-Ringer bicarbonate (KRB) containing 16.7 mM glucose. Islets were then lysed and [3H]inositol phosphate (IPx) production was determined. The data are expressed as IPx production normalized to glycerophosphoinositol phosphate ([3H]PI(Px)) levels. (C) Three representative traces (shown in blue, red, and green) of free intracellular Ca2+ in pancreatic islets from M3-muscarinic receptor knockout mice loaded with FURA2-AM (in KRB containing 16.7 mM glucose) and stimulated with methacholine (100 μM), as indicated. Thapsigargin (2 μM) was added as an internal control to ensure that the islets contained a releasable intracellular calcium store. (D) Methacholine (100 μM)-induced changes in intracellular Ca2+ in pancreatic islets from wild-type (blue line) and M3R-KI (pink line) mice. Data are expressed as change in the 340/380 ratio following addition of methacholine at 30 s (WT, n = 69; KI, n = 95). The graphical data are the means ± SE of at least five experiments. **, P < 0.01 compared with wild-type stimulated levels (t test).

Furthermore, methacholine treatment of wild-type islets resulted in a robust calcium response, which was absent in islets derived from M3-receptor knock-out mice (Fig. 2C), indicating that the M3-muscarinic receptor was responsible for this activity. The peak calcium response of islets isolated from M3R-KI animals did not appear to be significantly different from that of wild-type islets (Fig. 2D); however, the M3R-KI islets did show an elevated plateau phase (Fig. 2D), which is consistent with a reduction in receptor desensitization, a phenomenon that would be anticipated in a phosphorylation-deficient GPCR (2).

M3-Muscarinic Receptor Phosphorylation Regulates Insulin Release from Isolated Pancreatic Islets.

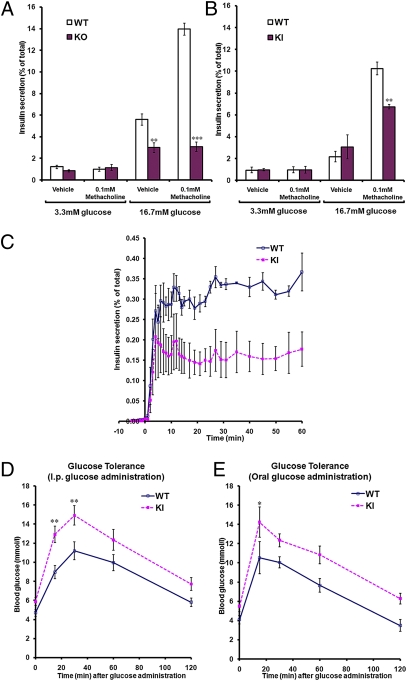

Previous studies have demonstrated that activation of the M3-muscarinic receptor in pancreatic islets induced a significant augmentation of glucose-dependent insulin release (17, 18). In agreement with these findings, we initially demonstrated that insulin release from wild-type islets in response to a high glucose concentration (16.7 mM) was enhanced by the muscarinic receptor agonist methacholine (Fig. 3A). This methacholine effect was absent in islets isolated from M3-muscarinic receptor knock-out animals (Fig. 3A), confirming that this response was mediated by the M3-muscarinic receptor. Interestingly, methacholine-mediated facilitation of insulin release (at 16.7 mM glucose) was significantly reduced in islets expressing the phosphorylation-deficient M3-muscarinic receptor. Muscarinic augmentation of insulin release from wild-type islets was ∼4.7-fold over basal, compared with ∼2.2-fold over basal in islets from M3R-KI mice (Fig. 3B).

Fig. 3.

Analysis of insulin secretion from pancreatic islets of wild type and M3R-KI mice. (A and B) Pancreatic islets isolated from wild-type, M3R-KI (KI), or M3-muscarinic receptor knockout (KO) mice were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C in KRB solution containing the indicated glucose concentrations in the presence or absence of methacholine (100 μM). The amount of insulin released into the medium was determined and normalized to the total insulin content of each well (islets plus medium). (C) Dynamic insulin secretion from perfused pancreatic islets isolated from wild-type or M3R-KI mice. Islets were perfused with KRB solution (1 mL/min) containing 3.3 mM glucose for over 30 min before being challenged with 100 μM methacholine and 16.7 mM glucose (starting from time-point 0). Perfusates were collected every minute up till 15 min and at indicated time points thereafter. In vivo analysis of glucose and insulin homeostasis in wild-type and M3R-KI mice. (D and E) Wild-type or M3R-KI mice were fasted overnight (10–16 h), and blood-glucose levels were measured at the indicated times after administration of a bolus dose of glucose (2 mg/g of body weight) by either intraperitoneal injection (D) (n = 17 for WT, n = 19 for KI) or oral gavage (E) (n = 6 for both WT and KI). Data shown are expressed as mean ± SE. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001 compared with the corresponding wild-type value (ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test).

To establish the dynamic nature of insulin release, isolated islets were placed in a perfusion chamber and insulin release monitored over a 60-min period. Whereas the initial peak of insulin release over the first 3 to 5 min of treatment with high glucose plus methacholine was similar between the wild-type and M3R-KI islets, the sustained phase of insulin release was significantly reduced in M3R-KI islets (Fig. 3C).

Importantly, the total insulin content of the islets from M3R-KI and wild-type animals were not significantly different [total insulin content per 10 islets: WT= 355.5 ± 14.4 μg/mL; M3R-KI = 397.1 ± 163 μg/mL; mean ± SE (n = 24)] nor were the mean size of the islets from M3R-KI mice significantly different from wild-type (Fig. S4). These data provided evidence that the deficit observed in M3-muscarinic receptor-mediated insulin release from M3R-KI islets was specific. This finding was further supported by the fact that the insulin release in response to other secretagogues, namely GLP-1 and L-arginine, was not significantly different in islets isolated from wild-type and M3R-KI mice (Fig. S5).

M3-Muscarinic Receptor Phosphorylation Regulates Serum Insulin and Glucose Levels.

To determine whether the reduction in insulin release observed in isolated islets from M3R-KI mice was physiologically relevant in vivo, we carried out glucose tolerance tests. We found that M3R-KI mice showed a significant impairment in glucose tolerance to glucose administered to fasted animals either intraperitoneally or orally (Fig. 3 D and E). The elevated plasma glucose concentrations observed with the M3R-KI mice correlated well with reduced plasma insulin levels (Fig. S6A).

To exclude the possibility that M3R-KI mice were insulin-intolerant, we carried out an insulin-sensitivity test. The M3R-KI mice showed higher absolute blood-glucose levels throughout compared with their wild-type controls (basal plasma-glucose concentrations: WT = 4.23 ± 0.37 mmol/L and M3R-KI = 8.85 ± 0.83 mmol/L), which correlated with the lower basal levels of serum insulin observed in Fig. 3F. However, the percentage reduction in blood-glucose levels following an intraperitoneal dose of insulin was not significantly different in the wild-type and M3R-KI mice (Fig. S6B), indicating that M3R-KI mice showed normal insulin-sensitivity.

Disrupted Coupling of the M3-Muscarinic Receptor to PKD1 Underlies the Deficiency in Insulin Release in M3R-KI Mice.

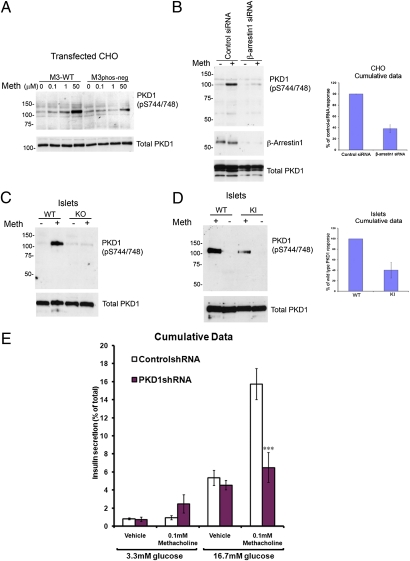

The protein kinase C-like serine/threonine kinase, PKD1, plays an important role in insulin secretion from pancreatic islets (19). This protein kinase is also known to be regulated by a number of GPCRs (20, 21). We found that M3-muscarinic receptor stimulation led to an increase in the overall phosphorylation state of PKD1 (Fig. S7A). More specifically, we showed that M3-muscarinic receptor stimulation increased the activating phosphorylation of PKD1 (22) at serine S744/748 and that the phosphorylation-deficient M3-muscarinic receptor expressed in CHO cells showed a reduction in the ability to activate PKD1 (Fig. 4A). These data indicated that M3-muscarinic receptor signaling to PKD1 was mediated not via Gq/11-coupling but rather via receptor phosphorylation and β-arrestin signaling. Consistent with this was the fact that pretreatment of CHO cells stably expressing the wild-type M3-muscarinic receptor with either PLC inhibitor (U-73122, 1 μM); PKC inhibitor (Ro-318220, 1 μM), or Ca2+-chelator (BAPTA, 10 μM) had no significant affect on methacholine-induced PKD1 phosphorylation (Fig. S7B). On the other hand, disruption of β-arrestin–mediated signaling by transfection of siRNA against β-arrestin 1 and 2 (Fig. S7C) or β-arrestin 1 alone (Fig. 4B) significantly impaired M3-muscarinic receptor activation of PKD1.

Fig. 4.

M3-muscarinic receptor-mediated augmentation of insulin release is dependent on PKD1, which in turn is activated by M3-muscarinic receptor phosphorylation and β-arrestin signaling. (A) CHO cells stably transfected with the wild-type M3-muscarinic receptor (M3-WT) or the phosphorylation-deficient mutant receptor (M3phos-neg) were stimulated with methacholine (Meth) at the indicated concentrations for 5 min and then solubilized. Lysates were probed for phosphorylated PKD1 at S744/748. The blot was then stripped and reprobed for total PKD1 as a loading control. (B) CHO cells stably expressing with the wild type M3-muscarinic receptor were transfected with control scrambled siRNA or siRNA that targets β-arrestin 1. Approximately 48 h after transfection, cells were stimulated with methacholine (Meth, 100 μM) for 5 min and then lysed and probed in Western blots for phosphorylated PKD1 at S744/748. The blot was then stripped and reprobed for β-arrestin 1 and total PKD1. The experiment shown is representative of four independent experiments. The graph shows the quantification of these results (mean ± SEM, n = 4). (C) Pancreatic islets isolated from wild-type (WT) or M3-muscarinic receptor knockout (KO) mice were stimulated with methacholine (Meth, 100 μM) for 5 min. Lysates were prepared and probed for PKD1 S744/748 phosphorylation. The blot was then stripped and probed for total PKD1. (D) As in C, except that islets from wild-type (WT) or M3R-KI (KI) mice were used. The graph shows quantification of these results. For all of the above, autoradiographs are representative of at least three independent experiments. (E) Pancreatic islets isolated from wild-type mice were infected with either control lentivirus containing scrambled shRNA or lentivirus containing shRNA that targeted PKD1. After 24 h, islets were incubated for 1 h at 37 °C in KRB solution containing the indicated glucose concentrations in the presence or absence of methacholine (100 μM). The amount of insulin released into the medium was determined and normalized to the total insulin content of each tube (islets plus medium). Shown here is the cumulative data from five independent experiments expressed as mean ± SE. ***, P < 0.001 compared with the corresponding wild-type value (ANOVA with Bonferroni post hoc test).

Interestingly, the small methacholine-induced activation of PKD1 observed in the CHO cells expressing the phosphorylation-deficient receptor mutant, M3phos-neg (Fig. 4A), was not completely removed by siRNA knockdown of β-arrestin 1 and 2 (Fig. S7D), suggesting that there is a small component of the activation of PKD1 that is receptor phosphorylation/arrestin independent.

In pancreatic islets, the activation of PKD1 via muscarinic agonists was mediated entirely via the M3-muscarinic receptor, because no activation was observed in islets lacking the M3-muscarinic receptor (Fig. 4C). Consistent with the recombinant cell data, muscarinic-activation of PKD1 in pancreatic islets derived from M3R-KI mice was reduced to 40.2 ± 14% of the wild-type response (Fig. 4D). Thus, in both recombinant cells and pancreatic islets, M3-muscarinic receptor activation of PKD1 was regulated by the phosphorylation status of the M3-muscarinic receptor.

These data would suggest that at least one mechanism for the reduction in insulin secretion observed in M3R-KI mice would be the loss of coupling to PKD1. To verify this hypothesis, we investigated if insulin secretion could be affected by a reduction in PKD1 activity. Hence, we used lentiviral infection of short-hairpin constructs that would generate siRNAs targeting PKD1. In these experiments we found these siRNAs resulted in either an efficient knock-down of PKD1 expression (Fig. S8A) or a partial knock-down in PKD1 levels (Fig. S7B). This variation was likely a result of the differential penetrance of the virus in different islet preparations. It did, however, provide an opportunity to observe the outcome of differential levels of PKD1 knock-down on the muscarinic augmentation of insulin release. In experiments where there was an efficient PKD1 knock-down, we observed a complete loss of muscarinic-augmentation of insulin release (Fig. S8A). In experiments where there was a partial knock-down of PKD1 protein levels, we observed a partial reduction in muscarinic receptor-augmentation of insulin release (Fig. S8B). The cumulative data demonstrated that there was a significant decrease in muscarinic receptor-mediated insulin release following siRNA knock-down of PKD1 in isolated islets (Fig. 4E).

Furthermore, we assessed the role of β-arrestin in the muscarinic response in isolated islets by knock-down of β-arrestin1 using lentiviral infection of shRNA that targeted β-arrestin 1. In these experiments we observed a small but significant inhibition of insulin release from pancreatic islets following treatment with siRNA against β-arrestin 1 (Fig. S9).

Hence, these experiments established a clear link between the activity of PKD1 and muscarinic facilitation of insulin release, further supporting the hypothesis that M3-muscarinic receptor-augmentation of insulin secretion requires PKD1 activity and that this activity is regulated by the phosphorylation status of the M3-muscarinic receptor (Fig. 5).

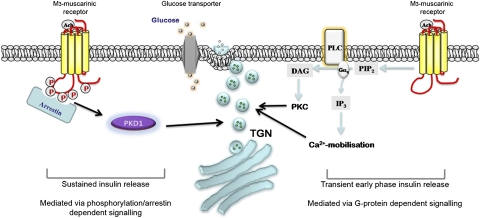

Fig. 5.

Schematic illustrating the mechanisms involved in M3-muscarinic receptor-mediated facilitation of insulin release. Previous studies have provided evidence that the early-phase insulin release is augmented by M3-muscarinic receptors via G protein-signaling that results in the increase in intracellular calcium and activation of protein kinase C (24, 25). We provide evidence in the present study that sustained glucose-dependent insulin release is enhanced by M3-muscarinic receptor stimulation in a G protein-independent manner. This latter mechanism requires receptor phosphorylation/arrestin-dependent signaling to PKD1. The activity of PKD1 augments insulin release possibly by promoting trafficking of secretory vesicles to the plasma membrane.

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that phosphorylation of the M3-muscarinic receptor plays an important mechanistic role in facilitating insulin release from pancreatic islets. Using a knock-in mouse strain that expresses a phosphorylation-deficient M3- muscarinic receptor mutant, we establish that this process is critical for maintaining glucose homeostasis in vivo. We show here that the M3-muscarinic receptor is able to activate PKD1 in pancreatic islets and that this activity is essential for muscarinic receptor-augmentation of insulin release from islets. The phosphorylation-deficient M3-muscarinic receptor showed reduced coupling to PKD1, which correlated with the inability of the receptor mutant to regulate insulin release and glucose homeostasis. Hence, our study supports the unique concept that augmentation of insulin release via the M3-muscarinic receptor is dependent on receptor coupling to PKD1, and that this in turn is regulated by the phosphorylation status of the receptor.

Importantly, the phosphorylation-deficient M3-muscarinic receptor mutant was processed to the plasma membrane normally and was expressed in tissues of the mouse in a comparable manner to the wild-type receptor. The mutant receptor was also coupled efficiently to the Gq/11/calcium signaling. The phosphorylation-deficient receptor mutant was, however, uncoupled from phosphorylation-dependent signaling, such as receptor internalization and the recruitment of β-arrestin. In this way the receptor showed features of G-protein bias: namely, that the signaling of the mutant receptor was biased toward heterotrimeric G protein-signaling rather than phosphorylation-/arrestin-dependent signaling (23). This finding has a significant impact when considering the mechanism of action of the M3-muscarinic receptor on glucose homeostasis. The fact that a deficiency in insulin release and glucose homeostasis was observed for the G protein-biased mutant receptor demonstrates that mechanisms other than G protein-dependent signaling play an important role in mediating muscarinic-receptor augmentation of insulin release. This finding is set in the context of earlier studies that have pointed to a role of G protein-signaling in the action of the M3-muscarinic receptor in insulin release (24) and, in particular, the possibility that calcium mobilization and activation of PKC can be important (24, 25). Whereas our studies do not rule out a role for heterotrimeric G protein-signaling in the action of M3-muscarinic receptors in the pancreas, our results demonstrate an additional, G protein-independent, signaling pathway that involves PKD1.

Members of the β-arrestin family are well-established adaptor proteins that interact with GPCRs in a phosphorylation-dependent manner (6, 7). In this adaptor role, β-arrestins are able to associate with a large number of signaling molecules (26), thus stimulating many G protein-independent pathways (6, 7) including, for example, signaling through the GLP-1 receptor to insulin release (27). We demonstrated that mutating the phosphorylation sites in the M3-muscarinic receptor resulted in a deficit in β-arrestin recruitment to the receptor. This deficit correlated with reduced coupling of the receptor to PKD1. Furthermore, siRNA knockdown of β-arrestin resulted in a significant reduction of the coupling of the M3-muscarinic receptor to PKD1. Thus, it is likely that phosphorylation-dependent recruitment of β-arrestin to the M3-muscarinic receptor is involved in the mechanism of activation of PKD1 and the subsequent augmentation of insulin release (Fig. 5).

PKD1 is generally considered to be a diacylglycerol sensor, which is activated by membrane translocation through the interaction of diacylglycerol with the C1A domain of the kinase together with activating phosphorylations mediated by conventional and atypical PKCs (20, 21). Previous studies on pancreatic islets have defined a role for phospholipase C and the mitogen-activated protein kinase, p38δ, in the activation of PKD1 (19). In contrast, our data point to the coupling of the M3-muscarinic receptor to PKD1 in a β-arrestin–dependent, Gq/11- independent manner. We have reached this conclusion primarily because of the fact that our phosphorylation-deficient mutant receptor shows a bias to Gq/11-signaling but is still deficient in coupling to PKD1. Furthermore, arrestin siRNA disrupted the coupling of the M3-muscarinic receptor from PKD1. Interestingly, a recent study on the Angiotensin 1 receptor demonstrated that the key signaling molecule activated by a biased ligand to the Angiotensin 1 receptor, which directed signaling in a β-arrestin–dependent and Gq/11-independent manner, was PKD1 (28). Thus, these studies on the Angiotensin 1 receptor, in common with ours on the M3-muscarinic receptor, demonstrated that PKD1 can be activated downstream of receptor phosphorylation/arrestin signaling.

Physiologically, there are two phases of insulin release associated with ingestion of food: a transient and sustained phase. The transient phase is associated with the preabsorbtive or cephalic phase of ingestion and is mediated by acetylcholine-parasympathetic fibers that innervate the pancreas (15, 24). The ability of muscarinic receptors to mediate this early phase of insulin release is thought to be via Gq/11-coupling to calcium and PKC pathways (24, 25). Our data, however, refer to the sustained enteric phase of digestion where prolonged insulin release is augmented by M3-muscarinic receptors acting in a manner independent of G protein-signaling, but dependent on receptor-phosphorylation/arrestin signaling acting upstream of PKD1 (Fig. 5).

In conclusion, our study presents evidence for a unique mechanism of muscarinic-mediated insulin release and glucose homeostasis. This mechanism involves M3-muscarinic receptor coupling to PKD1 via a phosphorylation-/arrestin-dependent pathway and is likely to be a mechanism that contributes to sustained muscarinic-mediated insulin release.

Materials and Methods

Generation of the Phosphorylation-Deficient M3phos-neg Receptor and Transgenic M3R-KI Mice.

Generation of the mice has been described in detail previously (14) and is further described here in SI Materials and Methods.

In Vitro Insulin Secretion Assays.

Isolation of islets and in vitro insulin secretion assay has been previously reported (18, 29) and described in detail here in SI Materials and Methods.

Further experimental procedures can be found in SI Materials and Methods.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Wellcome Trust (Grant 047600) and the Intramural Research Program, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, National Institutes of Health, US Department of Health and Human Services.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1011651107/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Pierce KL, Premont RT, Lefkowitz RJ. Seven-transmembrane receptors. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2002;3:639–650. doi: 10.1038/nrm908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Premont RT, Gainetdinov RR. Physiological roles of G protein-coupled receptor kinases and arrestins. Annu Rev Physiol. 2007;69:511–534. doi: 10.1146/annurev.physiol.69.022405.154731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tobin AB, Butcher AJ, Kong KC. Location, location, location… Site-specific GPCR phosphorylation offers a mechanism for cell-type-specific signalling. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2008;29:413–420. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bockaert J, et al. GPCR-interacting proteins (GIPs): Nature and functions. Biochem Soc Trans. 2004;32:851–855. doi: 10.1042/BST0320851. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kreienkamp HJ. Organisation of G-protein-coupled receptor signalling complexes by scaffolding proteins. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2002;2:581–586. doi: 10.1016/s1471-4892(02)00203-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lefkowitz RJ, Rajagopal K, Whalen EJ. New roles for beta-arrestins in cell signaling: Not just for seven-transmembrane receptors. Mol Cell. 2006;24:643–652. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Reiter E, Lefkowitz RJ. GRKs and beta-arrestins: Roles in receptor silencing, trafficking and signaling. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2006;17(4):159–165. doi: 10.1016/j.tem.2006.03.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Caulfield MP. Muscarinic receptors—Characterization, coupling and function. Pharmacol Ther. 1993;58:319–379. doi: 10.1016/0163-7258(93)90027-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wess J, Eglen RM, Gautam D. Muscarinic acetylcholine receptors: Mutant mice provide new insights for drug development. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2007;6:721–733. doi: 10.1038/nrd2379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Budd DC, McDonald JE, Tobin AB. Phosphorylation and regulation of a Gq/11-coupled receptor by casein kinase 1alpha. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:19667–19675. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M000492200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luo J, Busillo JM, Benovic JL. M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor-mediated signaling is regulated by distinct mechanisms. Mol Pharmacol. 2008;74:338–347. doi: 10.1124/mol.107.044750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Torrecilla I, et al. Phosphorylation and regulation of a G protein-coupled receptor by protein kinase CK2. J Cell Biol. 2007;177(1):127–137. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200610018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Willets JM, Challiss RA, Nahorski SR. Endogenous G protein-coupled receptor kinase 6 Regulates M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor phosphorylation and desensitization in human SH-SY5Y neuroblastoma cells. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:15523–15529. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111217200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Poulin B, et al. The M3-muscarinic receptor regulates learning and memory in a receptor phosphorylation/arrestin-dependent manner. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2010;107:9440–9445. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0914801107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ahrén B. Autonomic regulation of islet hormone secretion—Implications for health and disease. Diabetologia. 2000;43:393–410. doi: 10.1007/s001250051322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gautam D, et al. Role of the M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor in beta-cell function and glucose homeostasis. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2007;9(Suppl 2):158–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1463-1326.2007.00781.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gautam D, et al. A critical role for beta cell M3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptors in regulating insulin release and blood glucose homeostasis in vivo. Cell Metab. 2006;3:449–461. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.04.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Duttaroy A, et al. Muscarinic stimulation of pancreatic insulin and glucagon release is abolished in m3 muscarinic acetylcholine receptor-deficient mice. Diabetes. 2004;53:1714–1720. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.53.7.1714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sumara G, et al. Regulation of PKD by the MAPK p38delta in insulin secretion and glucose homeostasis. Cell. 2009;136:235–248. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Oancea E, Bezzerides VJ, Greka A, Clapham DE. Mechanism of persistent protein kinase D1 translocation and activation. Dev Cell. 2003;4:561–574. doi: 10.1016/s1534-5807(03)00087-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wang QJ. PKD at the crossroads of DAG and PKC signaling. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2006;27:317–323. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2006.04.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rybin VO, Guo J, Steinberg SF. Protein kinase D1 autophosphorylation via distinct mechanisms at Ser744/Ser748 and Ser916. J Biol Chem. 2009;284:2332–2343. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M806381200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Violin JD, Lefkowitz RJ. Beta-arrestin-biased ligands at seven-transmembrane receptors. Trends Pharmacol Sci. 2007;28:416–422. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2007.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gilon P, Henquin JC. Mechanisms and physiological significance of the cholinergic control of pancreatic beta-cell function. Endocr Rev. 2001;22:565–604. doi: 10.1210/edrv.22.5.0440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gromada J, Hughes TE. Ringing the dinner bell for insulin: Muscarinic M3 receptor activity in the control of pancreatic beta cell function. Cell Metab. 2006;3:390–392. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiao K, et al. Functional specialization of beta-arrestin interactions revealed by proteomic analysis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:12011–12016. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704849104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sonoda N, et al. Beta-Arrestin-1 mediates glucagon-like peptide-1 signaling to insulin secretion in cultured pancreatic beta cells. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:6614–6619. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710402105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Christensen GL, et al. Quantitative phosphoproteomics dissection of seven-transmembrane receptor signaling using full and biased agonists. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2010;9:1540–1553. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M900550-MCP200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Davalli AM, et al. Function, mass, and replication of porcine and rat islets transplanted into diabetic nude mice. Diabetes. 1995;44(1):104–111. doi: 10.2337/diab.44.1.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.