Abstract

Serine hydrolases (SHs) are one of the largest and most diverse enzyme classes in mammals. They play fundamental roles in virtually all physiological processes and are targeted by drugs to treat diseases such as diabetes, obesity, and neurodegenerative disorders. Despite this, we lack biological understanding for most of the 110+ predicted mammalian metabolic SHs, in large part because of a dearth of assays to assess their biochemical activities and a lack of selective inhibitors to probe their function in living systems. We show here that the vast majority (> 80%) of mammalian metabolic SHs can be labeled in proteomes by a single, active site-directed fluorophosphonate probe. We exploit this universal activity-based assay in a library-versus-library format to screen 70+ SHs against 140+ structurally diverse carbamates. Lead inhibitors were discovered for ∼40% of the screened enzymes, including many poorly characterized SHs. Global profiles identified carbamate inhibitors that discriminate among highly sequence-related SHs and, conversely, enzymes that share inhibitor sensitivity profiles despite lacking sequence homology. These findings indicate that sequence relatedness is not a strong predictor of shared pharmacology within the SH superfamily. Finally, we show that lead carbamate inhibitors can be optimized into pharmacological probes that inactivate individual SHs with high specificity in vivo.

Keywords: enzymology, mass spectrometry, profiling, proteomics

A major challenge facing biological researchers in the 21st century is the functional characterization of the large number of unannotated gene products identified by genome sequencing efforts (1). Many proteins partly or completely uncharacterized with respect to their biochemical activities belong to expansive, sequence-related families (2). Although such membership can inform on the general mechanistic class to which a protein belongs (e.g., enzyme, receptor, or channel), it is insufficient to predict specific biochemical and physiological functions, which require knowledge of substrates, ligands, and interacting biomolecules. On the contrary, membership within a large protein family can even present a barrier to achieving these goals by frustrating the implementation of standard genetic and pharmacological methods to probe protein function. For example, targeted gene disruption of one member of a protein superfamily may result in cellular compensation from other family members.

Problems are also encountered when attempting to develop specific inhibitors and/or ligands for uncharacterized members of large protein families, where at least two major experimental issues must be addressed. First, there is an intrinsic difficulty facing ligand discovery for uncharacterized proteins, which often lack the functional information required to develop high-quality assays for compound screening. Creative solutions to this problem have emerged for specific protein classes, such as G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs) (3) and kinases (4, 5), where generic assays have been developed that exploit conserved functional and/or structural features displayed by members of each protein family (e.g., G-protein coupling for GPCRs; ATP-binding sites for kinases). Whether such “universal” assay parameters exist for other protein superfamilies is unclear. Second, even with a general screening assay in hand, achieving ligand selectivity for one member of a large protein family presents a major challenge. Methods are particularly needed to assess selectivity in native biological systems, where proteins are regulated by posttranslational mechanisms that may alter their activity and ligand affinity (6, 7).

Activity-based protein profiling (ABPP) (8) is a chemical proteomic technology that addresses some of the aforementioned challenges. ABPP employs active site-directed chemical probes that covalently label large numbers of mechanistically related enzymes in native biological systems. ABPP probes have so far been developed for more than a dozen enzyme families, including hydrolases (9–14), kinases (15), histone deacetylases (16), and oxidoreductases (17, 18). When performed in a competitive format, where compounds are assayed for their ability to block probe labeling (10, 12, 19), ABPP offers a powerful means to discover small-molecule inhibitors of enzymes that is independent of their degree of functional annotation. A key advantage of competitive ABPP is that it permits simultaneous optimization of the potency and selectivity of inhibitors against numerous related enzymes directly in their native cellular environment. This strategy has led to the identification of selective inhibitors for many enzymes (12, 19–25), including several uncharacterized proteins (22–24).

Despite these advantages, competitive ABPP has not yet been demonstrated to be feasible for screening the large majority of enzymes from an expansive family against a small-molecule library. Here, we address this problem by evaluating the performance of ABPP against the mammalian serine hydrolase (SH) superfamily. We show that > 80% of the 110+ predicted metabolic SHs in mammals are targeted by a single fluorophosphonate (FP) activity-based probe. We employ this FP probe to perform a library-versus-library competitive ABPP screen, wherein 72 SHs are assayed against a collection of ∼140 carbamate small molecules. From this screen, lead inhibitors were discovered for more than 30 SHs, including several uncharacterized enzymes. Importantly, we show that competitive ABPP can be used to identify inhibitors that discriminate among highly sequence-related hydrolases and direct the rapid optimization of these inhibitors into pharmacological probes that selectively inactivate individual SHs in living animals.

Results

Global Cell and Tissue Profiling with a FP Activity-Based Probe.

Human SHs can be divided into two near-equal-sized subfamilies—the trypsin/chymotrypsin class of serine proteases (∼125 human members) and the metabolic SHs (∼115 human members) (26). The latter set of enzymes includes a wide range of structurally diverse peptidases, lipases, esterases, thioesterases, and amidases. Although FP probes (SI Appendix, Fig. S1) have been shown to label both serine proteases and metabolic SHs (10, 27, 28), we elected to focus our analysis on metabolic SHs, because serine proteases are often produced as inactive precursors (zymogens) and therefore are difficult to assay in heterologous expression systems.

As has been recently reviewed (26), metabolic SHs play key roles in diverse (patho)physiological processes, and several of these enzymes are targeted by clinically approved drugs, including acetylcholinesterase (AChE) for Alzheimer’s disease (29), pancreatic lipases for obesity (30), and dipeptidylpeptidase IV for diabetes (31). Despite the importance of metabolic SHs in mammalian physiology, nearly half of these enzymes remain without any assigned biochemical activity or substrate (26). Selective inhibitors are also lacking for the vast majority (> 80%) of mammalian metabolic SHs, further complicating their functional characterization. Previous studies have showcased the value of FP probes for ABPP of SHs in proteomes (27, 28, 32) and for the discovery of inhibitors for members of this enzyme family (19, 22, 23, 25). Whether competitive ABPP can serve as a universal assay for SH inhibitor discovery depends, however, on the fraction of mammalian SHs that can be profiled by FP probes.

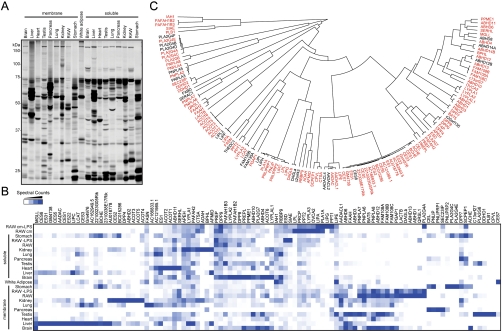

We set out to determine the full complement of mammalian metabolic SHs targeted by FP probes by using a panel of mouse cell and tissue proteomes that showed diverse labeling patterns with a fluorescent FP (FP-rhodamine) as judged by 1D-SDS-PAGE (Fig. 1A and SI Appendix, Fig. S2). We identified the SH targets of FP probes in these tissues by using the MS platform ABPP-MudPIT (28). Briefly, proteomes were incubated with a biotinylated FP probe [FP-biotin (9)], and FP-labeled enzymes were enriched with avidin beads, digested with trypsin, and analyzed by multidimensional liquid chromatography (LC)-MS/MS. Probe-labeled SHs were defined as those that showed (i) an average of ≥5 spectral counts in FP-treated proteomes and (ii) > 5-fold more spectral counts in probe-treated versus “no probe” control samples. In total, 101 FP-labeled SHs were identified in mouse cells and tissues (SI Appendix, Table S1), and this number was further increased to 105 by evaluating FP labeling for recombinantly expressed versions of SHs that show low signals in tissues (1 < average spectral counts < 5). Several SHs showed tissue-restricted patterns of probe labeling consistent with their known expression profiles and functions [e.g., pancreatic lipases (PNLIP, PNLIPRP1, and PNLIPRP2) were found exclusively in the pancreas; hepatic lipase (LIPC) was most strongly labeled in the liver] (Fig. 1B). The 105 FP-labeled SHs number accounts for 82% of the 128 predicted metabolic SHs in mice (Fig. 1C). We conclude from these data that a FP activity-based probe can serve as a near-universal assay to characterize mammalian SHs in proteomes. We next sought to adapt this assay for screening a library of small-molecule inhibitors against the SH superfamily.

Fig. 1.

Determining the full complement of mammalian metabolic SHs targeted by FP activity-based probes. (A) A panel of mouse tissue proteomes (1 mg of protein per mL) was labeled with FP-rhodamine (2 μM, 45 min) and proteomes analyzed by 1D-SDS-PAGE and in-gel fluorescence scanning. Representative fluorescent gel of FP-rhodamine-labeling events shown in gray scale. (B) Hierarchical cluster analysis of SH activity signals identified in mouse tissues by ABPP-MudPIT. Data are presented as the average spectral counts from three independent experiments normalized for each SH to the tissue containing the most spectral counts for that enzyme. (C) A dendrogram showing all 128 members of the mouse metabolic SH family with branch length depicting sequence relatedness. This analysis includes two additional human SHs, FAAH2 and PNPLA4, that lack mouse orthologues. SHs that were labeled by FP activity-based probes are shown in red (105 enzymes or 82% of the metabolic SH family). cm, conditioned media; LPS, cells treated with 10 μg/mL lipopolysaccharide for 24 h; RAW, RAW264.7 mouse macrophage cell line.

A Library-Versus-Library Format for Competitive ABPP.

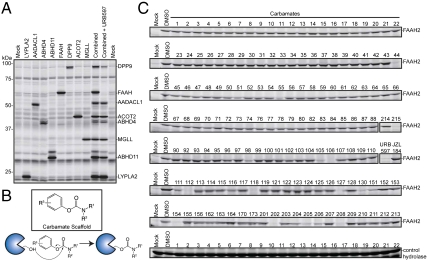

A typical format for competitive ABPP involves incubation of a proteome with a small molecule, followed by labeling of the sample with a fluorescent activity-based probe, separating proteins by SDS-PAGE, and quantifying the fluorescence intensity of protein band(s) on the gel relative to a control (DMSO-treated) proteome (19, 23). Although this type of competitive ABPP experiment can be performed in native cell and tissue proteomes, the large differences in endogenous expression levels of SHs, combined with their tendency to cluster in certain mass ranges (25–35 and 55–65 kDa), means that only a fraction of SHs can be resolved by 1D-SDS-PAGE in native proteomes. Complementary MS-based platforms, such as ABPP-MudPIT, have been introduced to address these problems (23, 25); however, such LC-MS methods are too time consuming to permit screening of a library of compounds. We therefore adopted a different strategy wherein each mammalian SH is recombinantly expressed (e.g., by transient transfection in eukaryotic cells) and then mass-resolvable subsets of these enzymes are combined into groups of up to eight enzymes to create a multiplexed SH library for inhibitor screening by 1D-SDS-PAGE. Importantly, this library-versus-inhibitor library format for competitive ABPP enabled, with only a handful of exceptions, screening of enzymes directly in crude cell proteomes (i.e., without requiring any enzyme purification).

We selected a total of 72 SHs for analysis, 66 of which were assayed as recombinant proteins and six of which were more conveniently obtained from endogenous sources (e.g., secreted SHs that could be accessed from the conditioned media of cell lines) (SI Appendix, Table S2). These enzymes were selected to cover most branches of the metabolic SH family (SI Appendix, Fig. S3). Only six enzymes required an additional, single purification step in order to visualize a band by FP-rhodamine labeling. Labeling with FP-rhodamine confirmed the activity of recombinant SHs and maintenance of their gel-resolved signals in multiplexed groups (Fig. 2A). We estimated that this assay format would permit the screening of more than 100 compounds against the entire 72-enzyme panel within the time frame of 4–6 wk. Given this level of throughput, we elected to screen a targeted library of candidate inhibitors on the basis of the carbamate group, which covalently reacts with the conserved serine nucleophile of SHs to form hydrolytically stable enzyme adducts (Fig. 2B). Carbamates have been developed that show excellent selectivity for individual SHs and have proven valuable as research tools (22, 23, 25, 33) and therapeutic drugs (29).

Fig. 2.

A library-versus-library format for competitive ABPP. (A) SHs were expressed individually and assayed for activity in crude cell lysates by treatment with FP-Rh and analysis by gel-based ABPP. Gel-resolvable SHs were combined and screened for inhibition by the carbamate library; a representative example is shown for the carbamate URB597, which is a known inhibitor of FAAH (33). (B) General structure of a carbamate library and mechanism of SH inactivation by carbamates. (C) Representative example of the primary competitive ABPP screening data for the enzyme FAAH2 expressed by transient transfection in 293T cells. A mock-transfected proteome and FP-rhodamine signals from an endogenously expressed SH are shown for comparison. Unless otherwise indicated, each number on the horizontal axis refers to a carbamate (lacking the WWL prefix to conserve space). From this analysis, several hits were identified, including WWL44, which selectively inhibited FAAH2 relative to other SHs with an IC50 value of 1.7 μM (Table 1). See SI Appendix, Fig. S4 for a complete set primary competitive ABPP data from our library-versus-library screen.

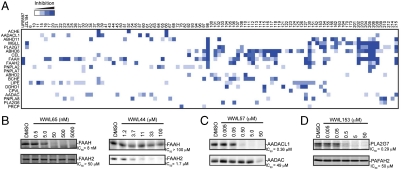

We synthesized a structurally diverse set of ∼140 carbamates (see SI Appendix for details) and screened these compounds at 50 μM against the 72-member SH panel. A compound was scored as active against a given SH if it blocked > 75% of FP-rhodamine labeling. A representative profile for the SH FAAH2 is shown in Fig. 2C. Primary competitive ABPP data for the other 71 SHs are shown in SI Appendix, Fig. S4, and a summary of the full library-versus-library dataset can be accessed at the Web site: http://www.scripps.edu/cgi-bin/cravatt/BachovchinJiLi2010. Carbamate hits were identified for 33 SHs (SI Appendix, Table S3), corresponding to ∼46% of the screened enzymes. Certain SHs, such as the carboxylesterases (CESs), showed broad reactivity with the carbamate library (SI Appendix, Fig. S4). This finding is consistent with previous studies designating CESs as common targets for a wide range of SH-directed inhibitors (19, 34, 35), which likely reflects the role that these enzymes play in xenobiotic metabolism (see SI Appendix for details). We also identified carbamate inhibitors for a substantial fraction (36%) of non-CES SHs (Fig. 3A and SI Appendix, Table S3). Notably, several of these carbamates were found to selectively inactivate a single (non-CES) SH (Fig. 3A and Table 1). We used competitive ABPP to calculate IC50 values for a representative set of these inhibitors, which ranged from 0.008 to 5.3 μM (Table 1, and SI Appendix, Fig. S5). Other carbamates showed slightly broader reactivity with the SH family, inhibiting a handful of enzymes (three to six) by > 75% at 50 μM (Fig. 3A). These results indicate that reasonably potent (nanomolar to low micromolar) and selective lead inhibitors can be obtained for many SHs from a modest-sized collection of carbamate small molecules.

Fig. 3.

Identification and characterization of lead inhibitors for SHs (A) Hierarchical cluster analysis of carbamate inhibition profiles for a representative subset of SHs. From this analysis, compounds that inactivate several SHs (e.g., WWL98 and WWL202) can be readily discriminated from those that show high selectivity for individual SHs (listed in Table 1 and B–D). (B–D) Concentration-dependent inhibition profiles for carbamates that show high selectivity for one member of a pair of sequence-related enzymes. (B) FAAH-1 versus FAAH-2, (C) AADAC versus AADACL1, and (D) PLA2G7 versus PAFAH2. See SI Appendix, Fig. S5 for more expanded concentration-dependent inhibition curves used to generate the reported IC50 values.

Table 1.

Selective lead inhibitors (and their SH targets) identified by library-versus-library competitive ABPP (see SI Appendix, Fig. S5 for concentration-dependent inhibition curves used to generate reported IC50 values)

| Hydrolase | Compound | Structure | IC50, μM |

| AADACL1 | WWL57 |  |

0.36 |

| ACHE | WWL52 |  |

3.5 |

| ABHD6 | WWL123 |  |

0.43 |

| ABHD11 | WWL151 |  |

5.3 |

| CEL | WWL92 |  |

4.1 |

| FAAH | WWL65 |  |

0.008 |

| FAAH2 | WWL44 |  |

1.7 |

| PLA2G7 | WWL153 |  |

0.29 |

| PNPLA8 | WWL210 |  |

2.9 |

Several sequence-related clades of enzymes exist within the SH family (Fig. 1C), and we wondered whether these enzymes would show equivalent inhibitor sensitivity profiles or, alternatively, if carbamates could discriminate among homologous enzymes. Our data strongly support the latter conclusion, because several carbamates were identified that selectively inactivate one member of a pair of nearest-sequence neighbor enzymes, including FAAH-1/FAAH-2, AADACL1/AADAC, and PLA2G7/PAFAH2 (Fig. 3 B–D). Interestingly, we also found cases where the most potent “off target” activity was not a homologous, but rather a very distantly related SH. For instance, WWL38 inhibited AADACL1 and ACHE with IC50 values of 4.8 and 13.3 μM, respectively, while showing no activity (IC50 > 100 μM) against AADAC (the nearest-sequence neighbor to AADACL1) (SI Appendix, Fig. S5). Such data indicate that sequence homology is not a particularly strong predictor of shared inhibitor sensitivity profiles among SHs, thus underscoring the importance of proteomic methods like ABPP that can uncover unanticipated pharmacological crosspoints within enzyme superfamilies.

Optimization of Carbamate Hits to Create in Vivo Pharmacological Probes.

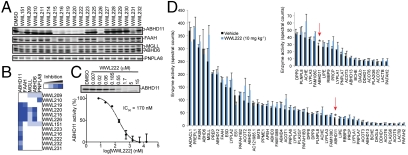

Although some highly potent inhibitors were identified directly from the carbamate library (e.g., WWL65, which was a sub-10-nM inhibitor of FAAH), most of the carbamate hits exhibited inhibitory activities in the range of high-nanomolar to low-micromolar. We therefore asked whether these moderate-potency leads could be efficiently optimized into selective and efficacious inhibitors for in vivo pharmacological studies. To address this question, we selected WWL151 as a case study, which selectively inhibited the uncharacterized SH ABHD11 with an IC50 value of 5.3 μM (Table 1). The most unusual feature of WWL151 compared to other members of the carbamate library was the seven-membered azepane ring, which appeared to grant this compound high selectivity for ABHD11 [compared, for example, to the six-membered piperidine ring analogue WWL215 (Table 2), which inhibited several additional SHs, including FAAH-1, FAAH-2, and PLA2G7 (Fig. 4A and SI Appendix, Fig. S4)]. Because only a limited number of azepane analogues are commercially available, we postulated that exchanging this ring system with a monosubstituted piperidine ring might offer a more facile medicinal-chemistry strategy for improving potency, while, at the same time, preserving selectivity for ABHD11. From this effort, we identified the 2-methyl substituted piperidyl carbamate WWL219 (Table 2), which showed markedly improved activity against ABHD11 (IC50 = 160 nM) but still inhibited the SH FAAH (Fig. 4 A and B). Extension of this 2-substitution to an ethyl group to give WWL222 (Table 2) maintained potency against ABHD11 (IC50 = 170 nM) (Fig. 4C) while eliminating activity against other SHs (Fig. 4 A and B).

Table 2.

Structures of a carbamate sublibrary targeting ABHD11, including the optimized inhibitor WWL222

| |||

| Compound | n | R1 | R2 |

| WWL151 | 3 | H | 4-NO2-Ph |

| WWL209 | 3 | H | Ph |

| WWL210 | 3 | H | 2-Cl-Ph |

| WWL211 | 3 | H | 2-OMe, 4-NO2-Ph |

| WWL214 | 3 | H | |

| WWL215 | 2 | H | 4-NO2-Ph |

| WWL216 | 1 | H | 4-NO2-Ph |

| WWL219 | 2 | 2-Me | 4-NO2-Ph |

| WWL220 | 2 | 4-Me | 4-NO2-Ph |

| WWL222 | 2 | 2-Et | 4-NO2-Ph |

| WWL223 | 2 | 2,6-(Me)2 | 4-NO2-Ph |

| WWL225 | 2 |  |

4-NO2-Ph |

| WWL226 | 2 | 3-Me | 4-NO2-Ph |

| WWL227 | 2 | 2-CH2OH | 4-NO2-Ph |

| WWL228 | 2 | 4-NO2-Ph | |

| WWL229 | 2 | 4-NO2-Ph | |

| WWL230 | 2 |  |

4-NO2-Ph |

| WWL231 | 2 | 4-NO2-Ph | |

| WWL232 | 2 | 4-NO2-Ph | |

Fig. 4.

Development of a selective and in vivo-active inhibitor of ABHD11. (A) Competitive ABPP signals for WWL151 and structural analogues (5 μM) against ABHD11 and the common off-targets for this compound scaffold—FAAH, MGLL, ABHD6, and PNPLA8. (B) Cluster analysis of the competitive ABPP data shown in A, designating WWL222 as a potent and selective ABHD11 inhibitor. (C) Concentration-dependent inhibition curve for WWL222 against ABHD11. From this curve, an IC50 value of 170 nM was calculated. Data are presented as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM); n = 3/group. (D) ABPP-MudPIT analysis of SHs from the brain proteomes of mice treated with vehicle or WWL222 (10 mg kg-1, i.p., 4 h); Among the ∼50 SHs detected in this analysis, only ABHD11 was inhibited by WWL222 (*p < 0.02). Data are presented as means ± SEM; n = 3/group.

An attractive feature of carbamates is that these agents typically show excellent pharmacological activity in vivo, including the ability to penetrate the nervous system (25, 33, 36), where their SH targets may play important roles in regulating neurochemical signaling pathways (37, 38). Consistent with this precedent, we found that administration of WWL222 to mice (10 mg/kg, i.p., 4 h) completely inactivated brain ABHD11 as judged by competitive ABPP-MudPIT (Fig. 4D). Remarkably, none of the other ∼50 brain SHs detected in this proteomic analysis were inhibited by WWL222. These data demonstrate that WWL222 acts as a selective and efficacious inhibitor of ABHD11 in vivo. To confirm that other carbamate hits also showed in vivo activity, we treated mice with the ABHD6 inhibitor WWL123 (Table 1; 5–20 mg/kg, i.p., 4 h). Competitive ABPP profiles of brain tissue from WWL123-treated animals revealed selective inactivation of ABHD6 (SI Appendix, Fig. S6).

Discussion

Complete genome sequences promise to radically change the field of molecular pharmacology. Systematic efforts to subclone and express the full complement of protein-coding sequences from mouse and human genomes are underway and should provide straightforward access to “expression-ready” constructs for these proteins (39, 40). The principal remaining challenge is then to develop general functional assays for mammalian proteins, a problem that is compounded by the fact that many of these proteins are uncharacterized with respect to biochemical and cellular activity. Here, we have shown that competitive ABPP offers a near-universal assay platform for the SH superfamily, which represents one of the largest and most diverse enzyme classes in mammals. We determined that more than 80% of the predicted metabolic SHs in mice can be profiled in cell and tissue proteomes with a single FP activity-based probe. SHs that were not detected by ABPP in this study could represent enzymes that show highly restricted tissue distributions [e.g., searches of the BioGPS database (http://biogps.gnf.org/) suggest that AADACL2 and AADACL4 are exclusively expressed in mouse skin and retina, respectively, two tissues that were not profiled in this study] or an inability to recognize and react with the FP probe. We also cannot exclude the possibility that some of the predicted SH genes are in fact pseudogenes that do not produce a functional protein product. These factors, taken together, suggest that more extensive tissue profiling, perhaps with structural analogues of the prototype FP probe (10), should further enhance ABPP coverage of the metabolic SH superfamily.

The library-versus-library format for competitive ABPP presented herein offers a technically straightforward and reasonably rapid way to screen the SH superfamily against hundreds of inhibitors. Although this platform is not compatible with screening of thousands of compounds, we should emphasize that the output is comparable to such higher-throughput screens in terms of aggregate data points (> 11,000 for our library-versus-library analysis) and information content. Because competitive ABPP tests each compound against numerous (70+) SHs in parallel, a family-wide portrait of pharmacological activity is generated for each inhibitor that immediately informs on its potency and selectivity. We used this combined information to identify useful lead carbamate inhibitors for several SHs, including enzymes, such as ABHD11, CEL, and PNPLA8, for which no other selective inhibitors have yet been described. In the case of ABHD11, we furthermore showed how structure-activity relationship data from the initial competitive ABPP screen could guide the rapid optimization of a low-micromolar hit into a selective and efficacious inhibitor, WWL222, that is suitable for in vivo pharmacological studies. Like many other SH inhibitors, our carbamate hits showed some cross-reactivity with members of the CES subfamily. This cross-reactivity should not, however, hinder the use of carbamates to characterize SHs in a wide range of biological systems, because CESs are mostly restricted in their expression to the liver (see Fig. 1B and discussion in the SI Appendix).

ABHD11 is a poorly characterized SH that exhibits a broad tissue distribution, including high expression in the brain and heart (Fig. 1B). Proteomic studies have identified ABHD11 as a mitochondrial protein (41), although its actual biochemical function, including its endogenous substrates and products, remains unknown. The ABHD11 gene is located in a region of chromosome 7 (7q11.23) that is hemizygously deleted in Williams–Beuren syndrome, a rare genetic disease with symptoms that include vascular stenosis, mental retardation, and excessive sociability (42). Whether ABHD11 plays a role in Williams–Beuren syndrome remains unclear. The inhibitor WWL222 should assist future investigations of ABHD11’s relevance to symptoms observed in Williams–Beuren syndrome, as well as to elucidate the enzyme’s endogenous biochemical and cellular functions.

Projecting forward, it is worthwhile to consider the grand question—how long might it take to generate selective and in vivo-active inhibitors for every member of the SH family by using a near-universal, proteomic assay like competitive ABPP? Although our discovery of lead inhibitors for ∼46% of the screened SHs (∼36% of the non-CES enzymes) is encouraging, we also note that several of these leads are not yet selective enough for use as pharmacological probes. It is possible that such multitarget carbamates can serve as medicinal-chemistry starting points for generating selective inhibitors of individual SHs [as has been accomplished for multitarget kinase inhibitors (7) and as we have previously shown for WWL98, which led to the development of the selective monoacylglycerol lipase (MGLL) inhibitor JZL184 (25)]. We also anticipate that some multitarget carbamates may show greater selectivity for individual SHs when tested at lower concentrations. As an initial assessment of this postulate, we measured IC50 values of 0.05, 1.57, and 2.75 μM for WWL110 versus BCHE, ABHD2, and CEL, respectively (SI Appendix, Fig. S5), indicating that this agent is a relatively selective inhibitor of BCHE but also potent enough to act as a lead for inhibitors of ABHD2 and CEL. Beyond this line of future research, achieving complete pharmacological coverage of the SH family will likely require screening either a much-expanded carbamate library or additional structural classes of compounds. Carbamates are quite straightforward from a synthetic perspective, and it is certainly possible to consider producing a larger (1,000+-member) library of these agents. One could also create additional small-molecule libraries on the basis of other chemotypes that mechanistically inhibit SHs, such as phosphonates (43), electrophilic ketones (19), and lactones (30) or lactams (44). As these compound libraries grow in size, they will eventually exceed the capacity of gel-based competitive ABPP. We have recently introduced one potential solution to this problem, a fluorescence polarization platform for ABPP that is compatible with ultrahigh-throughput screening (24).

Finally, we anticipate that the knowledge gained from our competitive ABPP studies with SHs can apply to genome-wide pharmacological studies of other enzyme families for which activity-based probes have been developed, including kinases (15), oxidoreductases (17, 18), and additional classes of hydrolases (12–14). In this way, future medicinal-chemistry pursuits may take on a decidedly proteomic flavor, such that projects focused on a single enzyme give way to more target-agnostic, family-wide investigations of small molecule–protein interactions. The resulting pharmacopeia should greatly enhance our understanding of protein function in mammalian physiology and disease.

Materials and Methods

Global Mouse Cell and Tissue Profiling with FP Probes.

See the SI Appendix for details.

Expression of SH Library.

See the SI Appendix for details.

Synthesis of Carbamate Library.

See the SI Appendix for details.

Primary Screening of Carbamate Library by Gel-Based ABPP.

Typically, ∼3–6 gel-resolvable SHs were combined into a single sample (25 μL) and incubated with DMSO or a carbamate (50 μM) for 45 min at 25 °C. FP-rhodamine (2 μM) was then added for an additional 45 min at 25 °C. The reactions were quenched, separated by SDS-PAGE, and visualized by in-gel fluorescence scanning. IC50 values for select compounds were determined as described in the SI Appendix.

ABPP-MudPIT Analysis of SHs Inhibited by Carbamates in Vivo.

See the SI Appendix for details.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS.

We thank David Milliken, Brent Martin, Sarah Tully, and Andrea Zuhl for technical assistance. This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health (DA025285, GM090294, DA026161), the Deutscher Akademischer Austausch Dienst (Postdoctoral Fellowship to A.A.), the National Science Foundation (Predoctoral Fellowship to D.A.B.), Activx Biosciences, and The Skaggs Institute for Chemical Biology

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1011663107/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Galperin MY, Koonin EV. ‘Conserved hypothetical’ proteins: Prioritization of targets for experimental study. Nucleic Acids Res. 2004;32:5452–5463. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkh885. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gerlt JA, Babbitt PC. Divergent evolution of enzymatic function: Mechanistically diverse superfamilies and functionally distinct suprafamilies. Annu Rev Biochem. 2001;70:209–246. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.70.1.209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Xiao SH, et al. High throughput screening for orphan and liganded GPCRs. Comb Chem High Throughput Screening. 2008;11(3):195–215. doi: 10.2174/138620708783877762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fabian MA, et al. A small molecule-kinase interaction map for clinical kinase inhibitors. Nat Biotechnol. 2005;23(3):329–336. doi: 10.1038/nbt1068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bishop AC, et al. A chemical switch for inhibitor-sensitive alleles of any protein kinase. Nature. 2000;407:395–401. doi: 10.1038/35030148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kobe B, Kemp BE. Active site-directed protein regulation. Nature. 1999;402:373–376. doi: 10.1038/46478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang J, Yang PL, Gray NS. Targeting cancer with small molecule kinase inhibitors. Nat Rev Cancer. 2009;9(1):28–39. doi: 10.1038/nrc2559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cravatt BF, Wright AT, Kozarich JW. Activity-based protein profiling: From enzyme chemistry to proteomic chemistry. Annu Rev Biochem. 2008;77:383–414. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.75.101304.124125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liu Y, Patricelli MP, Cravatt BF. Activity-based protein profiling: The serine hydrolases. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1999;96:14694–14699. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.26.14694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kidd D, Liu Y, Cravatt BF. Profiling serine hydrolase activities in complex proteomes. Biochemistry. 2001;40:4005–4015. doi: 10.1021/bi002579j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patricelli MP, Giang DK, Stamp LM, Burbaum JJ. Direct visualization of serine hydrolase activities in complex proteome using fluorescent active site-directed probes. Proteomics. 2001;1:1067–1071. doi: 10.1002/1615-9861(200109)1:9<1067::AID-PROT1067>3.0.CO;2-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Greenbaum D, et al. Chemical approaches for functionally probing the proteome. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2002;1:60–68. doi: 10.1074/mcp.t100003-mcp200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kato D, et al. Activity-based probes that target diverse cysteine protease families. Nat Chem Biol. 2005;1:33–38. doi: 10.1038/nchembio707. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sieber SA, Niessen S, Hoover HS, Cravatt BF. Proteomic profiling of metalloprotease activities with cocktails of active-site probes. Nat Chem Biol. 2006;2:274–281. doi: 10.1038/nchembio781. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patricelli MP, et al. Functional interrogation of the kinome using nucleotide acyl phosphates. Biochemistry. 2007;46(2):350–358. doi: 10.1021/bi062142x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Salisbury CM, Cravatt BF. Activity-based probes for proteomic profiling of histone deacetylase complexes. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:1171–1176. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608659104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Adam GC, Sorensen EJ, Cravatt BF. Proteomic profiling of mechanistically distinct enzyme classes using a common chemotype. Nat Biotechnol. 2002;20:805–809. doi: 10.1038/nbt714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Speers AE, Cravatt BF. A tandem orthogonal proteolysis strategy for high-content chemical proteomics. J Am Chem Soc. 2005;127:10018–10019. doi: 10.1021/ja0532842. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leung D, Hardouin C, Boger DL, Cravatt BF. Discovering potent and selective reversible inhibitors of enzymes in complex proteomes. Nat Biotechnol. 2003;21:687–691. doi: 10.1038/nbt826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Greenbaum DC, et al. A role for the protease falcipain 1 in host cell invasion by the human malaria parasite. Science. 2002;298:2002–2006. doi: 10.1126/science.1077426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ahn K, et al. Discovery and characterization of a highly selective FAAH inhibitor that reduces inflammatory pain. Chem Biol. 2009;16:411–420. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chiang KP, Niessen S, Saghatelian A, Cravatt BF. An enzyme that regulates ether lipid signaling pathways in cancer annotated by multidimensional profiling. Chem Biol. 2006;13:1041–1050. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Li W, Blankman JL, Cravatt BF. A functional proteomic strategy to discover inhibitors for uncharacterized hydrolases. J Am Chem Soc. 2007;129:9594–9595. doi: 10.1021/ja073650c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bachovchin DA, Brown SJ, Rosen H, Cravatt BF. Substrate-free high-throughput screening identifies selective inhibitors for uncharacterized enzymes. Nat Biotechnol. 2009;27:387–394. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Long JZ, et al. Selective blockade of 2-arachidonoylglycerol hydrolysis produces cannabinoid behavioral effects. Nat Chem Biol. 2009;5(1):37–44. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Simon GM, Cravatt BF. Activity-based proteomics of enzyme superfamilies: Serine hydrolases as a case study. J Biol Chem. 2010;285:11051–11055. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R109.097600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jessani N, Liu Y, Humphrey M, Cravatt BF. Enzyme activity profiles of the secreted and membrane proteome that depict cancer invasiveness. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:10335–10340. doi: 10.1073/pnas.162187599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jessani N, et al. A streamlined platform for high-content functional proteomics of primary human specimens. Nat Methods. 2005;2:691–697. doi: 10.1038/nmeth778. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Birks J, Grimley Evans J, Iakovidou V, Tsolaki M, Holt FE. Rivastigmine for Alzheimer's disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2009;2:CD001191. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD001191.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Henness S, Perry CM. Orlistat: A review of its use in the management of obesity. Drugs. 2006;66:1625–1656. doi: 10.2165/00003495-200666120-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dhillon S. Sitagliptin: A review of its use in the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus. Drugs. 2010;70(4):489–512. doi: 10.2165/11203790-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nomura DK, et al. Monoacylglycerol lipase regulates a fatty acid network that promotes cancer pathogenesis. Cell. 2010;140:49–61. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kathuria S, et al. Modulation of anxiety through blockade of anandamide hydrolysis. Nat Med. 2003;9(1):76–81. doi: 10.1038/nm803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang D, et al. Fatty acid amide hydrolase inhibitors display broad selectivity and inhibit multiple carboxylesterases as off-targets. Neuropharmacology. 2007;52:1095–1105. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2006.11.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Alexander JP, Cravatt BF. Mechanism of carbamate inactivation of FAAH: Implications for the design of covalent inhibitors and in vivo functional probes for enzymes. Chem Biol. 2005;12:1179–1187. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2005.08.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Long JZ, et al. Dual blockade of FAAH and MAGL identifies behavioral processes regulated by endocannabinoid crosstalk in vivo. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2009;106:20270–20275. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0909411106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ahn K, McKinney MK, Cravatt BF. Enzymatic pathways that regulate endocannabinoid signaling in the nervous system. Chem Rev. 2008;108:1687–1707. doi: 10.1021/cr0782067. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Racchi M, Mazzucchelli M, Porrello E, Lanni C, Govoni S. Acetylcholinesterase inhibitors: Novel activities of old molecules. Pharmacol Res. 2004;50(4):441–451. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2003.12.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Carpenter AE, Sabatini DM. Systematic genome-wide screens of gene function. Nat Rev Genet. 2004;5(1):11–22. doi: 10.1038/nrg1248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ramachandran N, et al. Next-generation high-density self-assembling functional protein arrays. Nat Methods. 2008;5:535–538. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.1210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Forner F, Foster LJ, Campanaro S, Valle G, Mann M. Quantitative proteomic comparison of rat mitochondria from muscle, heart, and liver. Mol Cell Proteomics. 2006;5:608–619. doi: 10.1074/mcp.M500298-MCP200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schubert C. The genomic basis of the Williams-Beuren syndrome. Cell Mol Life Sci. 2009;66:1178–1197. doi: 10.1007/s00018-008-8401-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miled N, et al. Inhibition of dog and human gastric lipases by enantiomeric phosphonate inhibitors: a structure-activity study. Biochemistry. 2003;42:11587–11593. doi: 10.1021/bi034964p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Veinberg G, Vorona M, Shestakova I, Kanepe I, Lukevics E. Design of beta-lactams with mechanism based nonantibacterial activities. Curr Med Chem. 2003;10:1741–1757. doi: 10.2174/0929867033457089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.