Abstract

Mood disorders such as bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder are common, chronic, and recurrent conditions affecting millions of individuals worldwide. Existing antidepressants and mood stabilizers used to treat these disorders are insufficient for many. Patients continue to have low remission rates, delayed onset of action, residual subsyndromal symptoms, and relapses. New therapeutic agents able to exert faster and sustained antidepressant or mood-stabilizing effects are urgently needed to treat these disorders. In this context, the glutamatergic system has been implicated in the pathophysiology of mood disorders in unique clinical and neurobiological ways. In addition to evidence confirming the role of the glutamatergic modulators riluzole and ketamine as proof-of-concept agents in this system, trials with diverse glutamatergic modulators are under way. Overall, this system holds considerable promise for developing the next generation of novel therapeutics for the treatment of bipolar disorder and major depressive disorder.

Keywords: AMPA, antidepressant, bipolar disorder, depression, glutamate, mania, NMDA

INTRODUCTION

Mood disorders such as bipolar disorder (BPD) and major depressive disorder (MDD) are chronic, disabling psychiatric disorders generally associated with unfavorable outcome and impairment in diverse areas.1 Indeed, the World Health Organization's (WHO) Global Burden of Disease projects that mood disorders will be the leading cause of disability worldwide within the next decade.2 Furthermore, available therapeutic options for the treatment of mood disorders are often insufficient for effectively managing the acute episodes, relapses, and recurrences that are the hallmarks of these disorders, or for restoring premorbid functioning.3,4 Consequently, increased rates of recurrences and persistent subsyndromal depressive symptoms, functional impairment, cognitive deficits, and disability are commonly present.5–7 It is estimated that less than one-third of patients with MDD achieve remission with an adequate trial of a standard antidepressant after 10–14 weeks of treatment.6,8 The situation is similarly sobering for BPD, where a sizable proportion of patients fail to respond to or tolerate currently available therapeutics, especially for the treatment and maintenance of bipolar depression.6,9 The presence of unpleasant side effects may also limit adherence in subjects with mood disorders.10

There is consequently a critical, unmet need to both identify and test novel drug targets for mood disorders in order to develop more effective treatments. It is a critical public health concern that the next generation of treatments for mood disorders be more effective, better tolerated, and more rapidly acting than currently available medications, which have predominantly targeted the monoaminergic system.4 This article reviews the diverse findings implicating the glutamatergic system in the pathophysiology of mood disorders, and examines that system's promise for developing the next generation of novel therapeutics.

THE FUNCTIONAL AND DYSFUNCTIONAL GLUTAMATERGIC SYSTEM IN MOOD DISORDERS

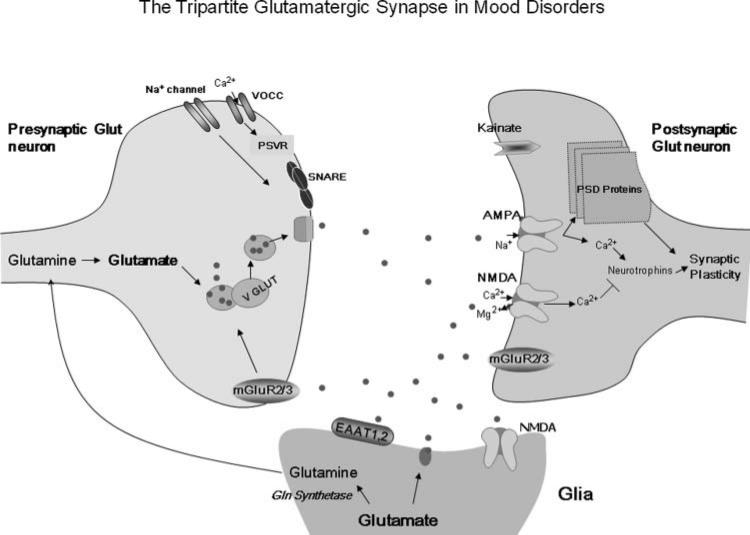

Glutamate is the most abundant excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain. It acts on three different cell compartments—presynaptic neurons, postsynaptic neurons, and glia—that characterize the “tripartite glutamatergic synapse”11 (see Figure 1). This integrated, neuronal-glial synapse is complex and directly involves the release, up-take, and inactivation of glutamate by different glutamate receptors (see text box) and other targets with potential clinical relevance, such as voltage-dependent ion channels and amino acid transporters.

Figure 1.

The tripartite glutamatergic synapse in mood disorders. The glutamate-glutamine cycle plays a key role in the regulation of pre- and postsynaptic ionic and metabotropic glutamate receptors that have been implicated in the pathophysiology of mood disorders. Glutamate is transformed into glutamine in glial cells and returns to the presynaptic neuron, where it is reconverted to glutamate. There, it induces several biological effects, mostly by activating ionic channels (especially calcium and sodium) and metabotropic mGluR2/3. In the postsynaptic glutamate neuron, AMPA receptor insertion and trafficking directly regulate plasticity and neurotransmission. Similarly, kainate receptors have been shown to critically regulate neuromodulation. Group II mGluRs are present in the pre- and postsynaptic neuron, interacting with glial cells. These receptors decrease NMDA receptor activity and the risk of cellular excitotoxicity. Also potentially relevant to the pathophysiology and therapeutics of mood disorders are the vesicular Glu transporters, voltage-dependent ionic channels, and SNARE proteins that directly control both glutamate levels in the synaptic cleft and the activation of glutamatergic receptors. Moreover, high-affinity, excitatory amino acid transporters, present mainly in glial cells, control synaptic levels of glutamate and the activation of ionotropic receptors, which regulate the activity of PSD proteins. AMPA, -amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionic acid; EAATs, excitatory amino acid transporters; mGluRs, metabotropic Glu receptors; NMDA, N-methyl-D-aspartate; PSD, postsynaptic density; PSVR, presynaptic voltage-operated release; SNARE, soluble N-ethylmaleimide–sensitive factor attachment receptor; VGLUT, vesicular glutamate transporter; VOCC, voltage-operated/dependent calcium channel.

Since the initial identification of glutamate as a neuro-transmitter in 1959, many studies have provided important insights into the role of the glutamatergic system in the pathophysiology and therapeutics of psychiatric disorders. The involvement of the glutamatergic system in mood disorders was first proposed based on preclinical data with N-methyl-d-aspartate (NMDA) antagonists.12 Early studies showed altered glutamate levels in serum and cerebrospinal fluid from patients with mood disorders (reviewed in Machado-Vieira R et al.).13

In the last decade, accumulating evidence from diverse studies suggests that the glutamatergic system plays a critical role in both MDD and BPD. Postmortem studies describe altered glutamate levels in diverse brain areas in individuals with mood disorders.14,15 In addition, elevated glutamate levels in the occipital cortex and decreased levels in the anterior cingulate cortex appear to be the most consistent findings in nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy studies of individuals with mood disorders.16–18 It is important to note that dysfunctions in glutamate levels and regulation are more complex than the simplistic view of either increased or decreased levels associated with mood disorders; indeed, both higher and lower levels have been described in different brain areas by imaging studies.16,17 Recently, magnetic resonance spectroscopy data evaluating gluta-mate/glutamine levels—which indirectly assess activity of the neuronal-glial cycle—have also provided important new insights into its dynamic regulation in mood disorders. Notably, the glutamate-glutamine cycle plays a critical role in the regulation of synaptic plasticity, learning, and memory.19

Broadly, synaptic plasticity refers to the cellular process that results in lasting changes in the efficacy of neuro-transmission. More specifically, it refers to the variability of the strength of a signal transmitted through a synapse.20 Neuroplasticity is a broader term that includes changes in intracellular signaling cascades and gene regulation,21 modifications of synaptic number and strength, variations in neurotransmitter release, modeling of axonal and dendritic architecture, and, in some areas of the central nervous system, the generation of new neurons. In recent years, research has linked mood disorders with structural and functional impairments related to neuroplasticity in various regions of the central nervous system.22 Thus, agents capable of increasing cellular resilience within the complex and interconnected dynamics between glutamate release and uptake in the tripartite glutamatergic synapse, while concomitantly targeting downstream signaling pathways involved in neuroplasticity, are promising novel therapeutics for the treatment of mood disorders. Here, we describe recent findings regarding glutamatergic-based novel therapeutics for mood disorders; these treatments target glutamate receptors, ionic channels, transporters, and postsynaptic proteins that regulate intra- and intercellular glutamate dynamics (Figure 1).

Excitatory Amino Acid Transporters and Vesicular Glutamate Transporters

Glutamate clearance from the extracellular space takes place mostly through the high-affinity excitatory amino acid transporters (EAATs). Decreased expression of diverse EAATs has been observed in postmortem studies of subjects with mood disorders (Figure 1),23,24 and increased expression of these transporters (e.g., as induced by ß-lactam antibiotics) has been found to induce antidepressant-like effects.25–27 Mood stabilizers such as valproate and lamotrigine also similarly upregulate EAAT activity,28,29 albeit through a potentially different mechanism. In contrast, EAAT antagonism induced depressive effects and altered circadian activity in preclinical models.26,30

Regarding the role of vesicular glutamate transporters (VGLUTs) in mood disorders, a recent postmortem study noted significantly decreased VGLUT1 mRNA expression in both MDD and BPD patients.31 Similarly, reduced VGLUT1 expression has been associated with increased anxiety, depressive-like behaviors, and impaired long-term memory.32 Preclinical studies have found that diverse antidepressants increase VGLUT expression in the limbic system,32,33 and a similar effect was observed after lithium treatment34—a mechanism that may be involved in lithium's protective effects against glutamate-induced excitotoxicity.35 Diverse compounds that target VGLUTs are now in development.36 This novel class of compounds is expected to induce therapeutic effects by buffering increased glutamatergic release.

Ionotropic Glutamate Receptors

Several studies have shown that ionotropic glutamate receptors play an important role in mood regulation. The NMDA receptors (NMDARs) have a slower and more prolonged postsynaptic current than the α-amino-3-hydroxyl-5-methyl-4-isoxazole-propionate (AMPA)/kainate receptors, but all ionotropic glutamate receptors exhibit fast receptor deactivation and dissociation of glutamate. These cellular effects may underlie the specific therapeutic profile of AMPA and NMDA modulators, mostly characterized by their rapid antidepressant effects.4 It has recently been proposed that both NMDA antagonism and AMPA receptor (AMPAR) activation are involved in ketamine's rapid antidepressant effects (see below for a more detailed discussion). Given the ability of AMPARs to induce a more rapid dissociation of glutamate, the proper balance in this dynamic and complex turnover may account for ketamine's unique therapeutic effects.

With regard to dysregulation of AMPARs, decreased levels of AMPAR subunits (glutamate receptor [GluR] 1, GluR2, and GluR3; see text box) have been reported in the prefrontal cortex and striatum of subjects with mood disorders.14,15,37,38 Also, abnormal metabotropic (m) GluR3 expression has been reported in suicidal subjects with BPD—a finding that was not replicated in a subsequent study.39,40 In line with these results, transgenic animals with lower GluR1 expression exhibit increased depressive-like behaviors.41

Therapeutically, AMPAR potentiators have been tested in various neuropsychiatric disorders and are a promising new class of agents for the treatment of mood disorders.42 AMPAR potentiators include benzothiazides (e.g., cyclothiazide), benzoylpiperidines (e.g., CX-516), and birylpropylsulfonamides (e.g., LY392098).43,44 These agents play a key role in modulating activity-dependent synaptic strength and behavioral plasticity.45 Furthermore, several preclinical studies found that the antidepressant-like effects of some AMPAR potentiators were also associated with improved cognitive functioning (reviewed in Miu et al.,43 Black,46 Lynch,47 and O'Neill et al.).48 In contrast to the antidepressant-like properties seen with AMPAR potentiators, AMPAR antagonists (e.g., the anticonvulsant talam-panel) are believed to have antimanic properties. To date, no placebo-controlled clinical trials with AMPAR potentiators for the treatment of depression or AMPA antagonists for the treatment of mania have been published.

Regarding the role of NMDARs in mood disorders, a series of elegant studies conducted over a decade ago used tricyclic antidepressants to demonstrate that NMDARs may represent a final common pathway of antidepressant action, one that is particularly associated with faster onset.49,50 Building on these findings, studies have described altered NMDAR binding and expression in individuals with MDD and BPD.23,24,37,51–53 Also, polymorphisms of GRIN1, GRIN2A, and GRIN2B (see text box) have been shown to confer susceptibility to BPD,54–56 further supporting a role for these targets in the pathophysiology of this disorder.

Diverse preclinical and clinical studies have found that NMDA antagonists produce rapid antidepressant effects.57–61 For instance, one preclinical study observed antidepressant-like effects with a selective NMDAR-2B antagonist,57 and other brain-penetrant NMDAR-2B antagonists are currently in development.62,63 These pre-clinical findings are supported by a recent, double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial evaluating the NMDAR-2B subunit−selective antagonist CP-101,606, which induced significant and relatively rapid antidepressant effects (by day 5) in patients with treatment-resistant MDD, but with evidence of psychomimetic properties.64 Additional clinical studies with NMDR-2A and -2B antagonists in MDD are under way.

It is important to mention that while dramatic clinical therapeutic effects were observed with the high-affinity NMDA antagonist ketamine in MDD (see below), a placebo-controlled study of the low-to-moderate affinity, noncompetitive NMDA antagonist memantine (oral dosing) found no antidepressant effects.65 These findings suggest that high affinity and IV administration may be key factors for achieving rapid antidepressant effects with this class of agents.

Kainate receptors activate postsynaptic inhibitory neurotransmission. These effects play a crucial role in calcium metabolism, synaptic strength, and oxidative stress, all of which are associated with the pathophysiology of MDD and BPD.11,66 A recent, large, family-based association study evaluating the kainate GRIK3 gene described linkage disequilibrium in MDD.67 Likewise, elevated GRIK3 DNA-copy number was observed in individuals with BPD;68 relatedly, a common variant in the 3'UTR GRIK4 gene was found to protect against BPD.69 Interestingly, the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR*D) and Munich Antidepressant Response Signature (MARS) projects described an association between treatment-emergent suicidal ideation and the glutamate system via the involvement of the GRIA3 and GRIK2 genes.70,71 A recent study also found that individuals with MDD who had a GRIK4 gene polymorphism (rs1954787) were more likely to respond to treatment with the antidepressant citalopram.72 In preclinical studies, GluR6 knockout mice displayed increased risk-taking and aggressive behaviors, as well as hyperactivity, in response to amphetamine—manic-like behaviors that decreased after chronic lithium treatment.73 These promising findings have led to increased interest in developing kainite receptor modulators, but, to date, no such compounds have been evaluated in the treatment of mood disorders.

Metabotropic Glutamate Receptors

Genetically-induced decreases in expression of mGluRs and agents that target mGluRs—especially Group II and III mGluR modulators—have consistently been found to induce anxiolytic, antidepressant, and neuroprotective effects in preclinical models.74–80 In particular, Group I and II mGluR antagonists such as MPEP (2-methyl-6-[phenylethynyl]-pyridine) and MGS-0039 had antidepressant-like and neuroprotective effects in animal models.81–84 Similar effects were observed with selective Group III mGluR agonists.77,79,85 Several compounds that modulate mGluRs are currently under development for treating MDD.

Postsynaptic Density Proteins

Other potentially relevant targets involving the glutamatergic synapse include the postsynaptic density (PSD) proteins. These proteins (PSD95, SAP102, and others), which interact with ionotropic glutamate receptors at the synaptic membrane, modulate receptor activity and signal transduction. For instance, NMDAR activation interacts directly with PSD95, thereby playing a critical role in the regulation of membrane trafficking, clustering, and downstream signaling events. In mood disorders, decreased PSD95 levels were observed in the dentate gyrus of individuals with BPD.53 In individuals with MDD, PSD95 levels were found to be significantly increased in the limbic system.86 SAP102, which interacts primarily with the NMDAR-2B subunit, has been shown to decrease NMDAR-2B subunit expression in individuals with mood disorders, a finding that was correlated with decreased expression of NMDAR subunits in the limbic system.24,87,88 While these findings suggest that PSD proteins may interact with NMDARs in the pathophysiology of mood disorders, currently no compounds specifically targeting PSD proteins have been developed.

RILUZOLE AND KETAMINE: PROTOTYPES FOR NEW, IMPROVED GLUTAMATERGIC MODULATORS FOR TREATING MOOD DISORDERS

Riluzole

The glutamatergic modulator riluzole is currently approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for treating amyotrophic lateral sclerosis. It has both neuroprotective and anticonvulsant properties due to its ability to inhibit glutamate release and enhance both glutamate reuptake and AMPA trafficking.89 Studies have also shown that it protects glial cells against glutamate excitotoxicity.90

Riluzole's antidepressant effects have been investigated in open-label studies. In the first study, 19 patients (68%) with treatment-resistant MDD completed the trial, and all showed significant improvement at week 6.91 In the second study, 14 patients with bipolar depression received riluzole adjunctively with lithium; they experienced a 60% overall decrease in Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale scores across the eight weeks of treatment and a significant improvement on that scale by week 5.92 In another study, riluzole (50mg/twice daily) was tested as add-on therapy in individuals with MDD; significant antidepressant effects were noted after one week of treatment, with a considerable decrease (36%) in Hamilton Depression Rating Scale scores observed among completers.93 Open-label trials also suggest that riluzole may be effective in treating generalized anxiety disorder and obsessive-compulsive disorder.94,95 Double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trials are necessary to confirm the promising findings of these open-label studies.

In addition to the clinical evidence, animal studies have shown that long-term use of riluzole induces antidepressant- and antimanic-like behaviors in rodents.96,97 It is important to note, however, that despite its efficacy, no evidence suggests that riluzole acts more rapidly than existing antidepressants, though it may be a reasonable therapeutic option in treatment-resistant cases.

Ketamine

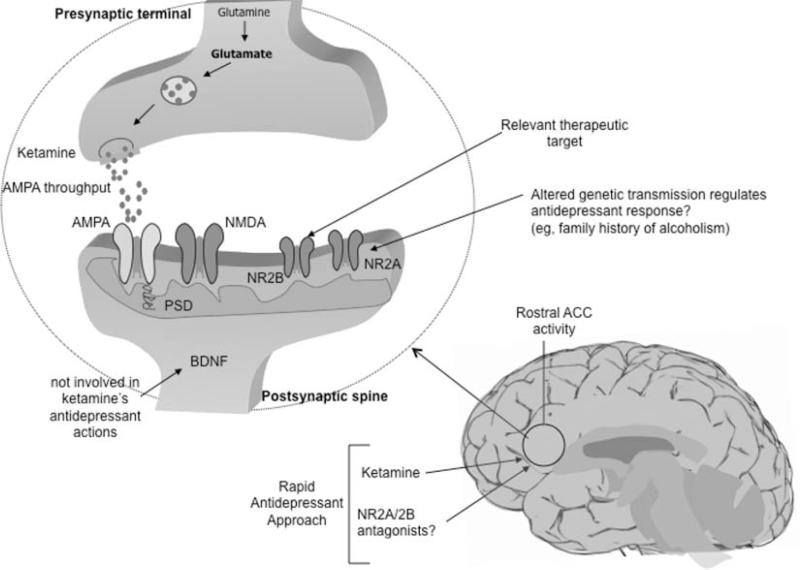

The noncompetitive, high-affinity NMDA antagonist ketamine is a phencyclidine derivative that prevents excess calcium influx and cellular damage by antagonizing NMDARs. In vitro, ketamine increases the firing rate of glutamatergic neurons and the presynaptic release of glutamate.98 Some of these properties are believed to be involved in the compound's antidepressant effects. AMPAR activation has also been shown to mediate ketamine's antidepressant-like effects.57 See Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Biological correlates of ketamine's antidepressant effects. BDNF does not appear to be involved in ketamine's rapid antidepressant effects; however, AMPA relative to NMDA throughput and its potential effects targeting at the PSD may represent a relevant mechanism by which ketamine induces these therapeutic effects. In particular, NR2A and NR2B receptors are believed to mediate these rapid antidepressant effects. Rostral anterior cingulate cortex activity has been implicated in rapid antidepressant response to ketamine infusion. Family history of alcohol dependence in MDD subjects was associated with better short-term outcome after ketamine infusion. ACC, anterior cingulate cortex; AMPA, α-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazolepropionic acid; BDNF, brain-derived neurotrophic factor; MDD, major depressive disorder; NMDA, N-methyl-D-aspartate; NR, NMDA receptor; PSD, postsynaptic density.

Similar to other NMDAR antagonists,99 ketamine induced antidepressant and anxiolytic effects in diverse pre-clinical studies.57,100–103 An initial clinical study found that seven subjects with treatment-resistant MDD had improved depressive symptoms within 72 hours of ketamine infusion.104 Subsequently, a double-blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study showed a fast (first two hours after infusion) and relatively sustained antidepressant effect (one to two weeks) after a single ketamine infusion in treatment-resistant patients with MDD.61 More than 70% of patients responded within 24 hours after infusion, and 35% maintained a sustained response at the end of week 1. Notably, the response rates obtained with ketamine after 24 hours (71%) were similar to those described after six to eight weeks of treatment with traditional monoaminergic-based antidepressants (65%).105,106 These findings were subsequently replicated in a different cohort of 26 subjects with treatment-resistant MDD.107

A recent study found that ketamine was also associated with robust and rapid antisuicidal effects.108 Thirty-three subjects with treatment-resistant MDD received a single open-label infusion of ketamine (0.5 mg/kg). Patients were rated at baseline, 40, 80, 120, and 230 minutes post-infusion using the Scale for Suicide Ideation. Scores significantly decreased within 40 minutes of ketamine infusion and remained improved for up to four hours post-infusion. In another study, early antisuicidal effects (within one day) were found with ketamine, and these effects remained significant for several weeks.109 Due to the public health implications of this finding, future studies evaluating ketamine's effect on suicidal ideation are warranted. Interestingly, ketamine infusion has also been associated with rapid antidepressant effects during pre- and postoperative states110,111 in patients with depression comorbid with pain syndrome or alcohol dependence,112,113 as well as during a course of electroconvulsive therapy.114 Despite these intriguing findings, its sedative and psychotomimetic side effects may limit its clinical use.115 Although misuse and abuse of therapeutically relevant agents in psychiatry are not new phenomena (e.g., as has occurred with benzodiazepines, anticholinergic drugs, and stimulants), an additional limitation of ketamine as a therapeutic agent is that it is one of several abusable “club drugs.”

Alcohol dependence increases NMDAR expression and induces cross-tolerance with NMDAR antagonists. Previous clinical studies found that, compared to healthy controls, subjects with alcohol dependence had fewer perceptual alterations and decreased dysphoric mood during ketamine infusion.116 This attenuation of ketamine-induced perceptual alterations was also observed in healthy individuals with a positive family history of alcohol dependence.117 In line with these findings, a recent study from our laboratory found that patients with MDD who had a family history of alcohol dependence had a better short-term outcome (greater and faster improvement in depressive symptoms) after ketamine infusion than subjects with no family history of alcohol dependence.107 It is also interesting to note that a recent study found that genetic variations in the NMDAR-2A gene are directly associated with alcohol dependence.118 Thus, the potential mechanisms underlying this different antidepressant response to ketamine in individuals with alcoholism may involve genetic differences in NMDA subunits, particularly NMDAR-2A binding, which is affected by chronic ethanol exposure.119,120

Other predictors of ketamine response have also been assessed. One recent study tested the hypothesis that magnetoencephalography recordings could provide a neurophysiological biomarker associated with ketamine's rapid antidepressant effects. Indeed, increased pretreatment rostral anterior cingulate cortex activity was found to be positively correlated with rapid antidepressant response to ketamine infusion in 11 MDD patients versus healthy controls.121 Other studies have shown that anterior cingulate cortex activation predicts improved antidepressant response to electroconvulsive therapy, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, deep brain stimulation, and sleep deprivation.122–126 Another study investigating the putative link between brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and ketamine found no association between ketamine's rapid antidepressant effects and plasma BDNF levels, which showed no change from baseline to 230 minutes post-infusion, a time point when antidepressant response is usually present.127

Finally, at the cellular level, ketamine's antidepressant-like effects were found to be selectively abolished using an AMPA antagonist (NBQX) prior to infusion—an effect not observed with imipramine.57 Thus, in humans, it is possible that ketamine's antidepressant effects are mediated via AMPAR activation and not critically through NMDAR antagonism. In contrast, the delayed effects induced by standard monoaminergic antidepressants occur via intracellular signaling changes,45 which might explain their differing time of onset.

FINAL REMARKS

Because monoaminergic antidepressants take weeks to achieve their full effect, patients receiving these medications remain vulnerable to impaired global functioning and are at high risk of self-harm. This long, risky period of latency in MDD, as well as the persistent residual symptoms, low rates of remission, and frequent relapses associated with currently available therapeutics, is a challenge that needs to be better addressed by the next generation of medications to treat this disorder. Available therapeutics for BPD are similarly not always well tolerated or effective—particularly in the treatment of bipolar depression.

While glutamatergic system abnormalities have been associated with mood disorders, the magnitude and extent of these abnormalities require further clarification. An improved understanding of the function, anatomy, and localization of different glutamatergic receptors in the brain would help to develop the subunit-selective agents necessary for producing improved therapeutics. Studies assessing the impact of novel glutamatergic treatments for mood disorders are under way; at least some of these agents are expected to work more quickly, and to be more effective and better tolerated, than current medications. An increasing number of proof-of-principle studies have also attempted to identify relevant therapeutic targets; riluzole and ketamine, for instance, are both being used in such research.

Despite the recent advances in our knowledge, future studies investigating the efficacy, safety, and potential mechanisms involved in the faster and potentially sustained antidepressant actions of new glutamatergic modulators are necessary. The development of such new, safe, and effective agents for the treatment of mood disorders would have an enormous and significant impact on public health worldwide.

| Glutamate Receptors and Genes |

|---|

| Ionotropic Glutamate Receptors |

| AMPA: GluR1, GluR2, GluR3, GluR4 (GRIA1, GRIA2, GRIA3, GRIA4) |

| NMDA: NR1, NR2 A-D, NR3 A-B (GRIN1, GRIN2A, GRIN2B, GRIN2C, GRIN2D, GRIN3A) |

| Kainate: GluR5, GluR6, GluR7, KA1, KA2 (GRIK1, GRIK2, GRIK3, GRIK4, GRIK5) |

| Metabotropic Glutamate Receptors |

| Group I (excitatory G-protein coupled) |

| mGluR1 (A-D) (GRM1) |

| mGluR5 (A-B) (GRM5) |

| Groups II and III (inhibitory G-protein coupled) |

| mGluR2 (GRM2) |

| mGluR3 (GRM3) |

| mGluR4 (A-B) (GRM4) |

| mGluR6 (GRM6) |

| mGluR7 (A-B) (GRM7) |

| mGluR8 (A-B) (GRM8) |

AMPA, -amino-3-hydroxy-5-methyl-4-isoxazole propionic acid; Glu, glutamate; NMDA, N-methyl-D-aspartate; m, metabotropic; GluRn, glutamate receptor no. n; KA, kainate.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interest: Dr. Zarate is listed as a coinventor on a patent for the use of ketamine in major depression. He has assigned his patient rights on katamine to the U.S. government.

REFERENCES

- 1.Kessler RC, Akiskal HS, Ames M, et al. Prevalence and effects of mood disorders on work performance in a nationally representative sample of U.S. workers. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:1561–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.9.1561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Murray CJ, Lopez AD. Evidence-based health policy—lessons from the Global Burden of Disease Study. Science. 1996;274:740–3. doi: 10.1126/science.274.5288.740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Insel TR, Scolnick EM. Cure therapeutics and strategic prevention: raising the bar for mental health research. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11:11–7. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Machado-Vieira R, Salvadore G, Luckenbaugh DA, Manji HK, Zarate CA., Jr Rapid onset of antidepressant action: a new paradigm in the research and treatment of major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychiatry. 2008;69:946–58. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v69n0610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fagiolini A, Kupfer DJ, Masalehdan A, Scott JA, Houck PR, Frank E. Functional impairment in the remission phase of bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2005;7:281–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2005.00207.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Judd LL, Akiskal HS, Schettler PJ, et al. The long-term natural history of the weekly symptomatic status of bipolar I disorder. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2002;59:530–7. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.59.6.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tohen M, Hennen J, Zarate CM, Jr, et al. Two-year syndromal and functional recovery in 219 cases of first-episode major affective disorder with psychotic features. Am J Psychiatry. 2000;157:220–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.157.2.220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Trivedi MH, Rush AJ, Wisniewski SR, et al. Evaluation of outcomes with citalopram for depression using measurement-based care in STAR*D: implications for clinical practice. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:28–40. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.28. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gitlin M. Treatment-resistant bipolar disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11:227–40. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001793. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baldessarini RJ, Perry R, Pike J. Factors associated with treatment nonadherence among US bipolar disorder patients. Hum Psychopharmacol. 2008;23:95–105. doi: 10.1002/hup.908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Machado-Vieira R, Manji HK, Zarate CA. The role of the tripartite glutamatergic synapse in the pathophysiology and therapeutics of mood disorders. Neuroscientist. 2009;15:525–39. doi: 10.1177/1073858409336093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Skolnick P, Legutko B, Li X, Bymaster FP. Current perspectives on the development of non-biogenic amine-based antidepressants. Pharmacol Res. 2001;43:411–23. doi: 10.1006/phrs.2000.0806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Machado-Vieira R, Salvadore G, Ibrahim I, Diaz-Granados N, Zarate CA. Targeting glutamatergic signaling for the development of novel therapeutics for mood disorders. Curr Pharm Des. 2009;15:1595–611. doi: 10.2174/138161209788168010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hashimoto K, Sawa A, Iyo M. Increased levels of glutamate in brains from patients with mood disorders. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;62:1310–6. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.03.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Scarr E, Pavey G, Sundram S, MacKinnon A, Dean B. Decreased hippocampal NMDA, but not kainate or AMPA receptors in bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2003;5:257–64. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-5618.2003.00024.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hasler G, Van Der Veen JW, Tumonis T, Meyers N, Shen J, Drevets WC. Reduced prefrontal glutamate/glutamine and gamma-aminobutyric acid levels in major depression determined using proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2007;64:193–200. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.64.2.193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanacora G, Gueorguieva R, Epperson CN, et al. Subtype-specific alterations of gamma-aminobutyric acid and glutamate in patients with major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2004;61:705–13. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.61.7.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yildiz-Yesiloglu A, Ankerst DP. Neurochemical alterations of the brain in bipolar disorder and their implications for pathophysiology: a systematic review of the in vivo proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy findings. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2006;30:969–95. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Collingridge GL, Bliss TV. Memories of NMDA receptors and LTP. Trends Neurosci. 1995;18:54–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schloesser RJ, Huang J, Klein PS, Manji HK. Cellular plasticity cascades in the pathophysiology and treatment of bipolar disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:110–3. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McClung CA, Nestler EJ. Neuroplasticity mediated by altered gene expression. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33:3–17. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301544. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Manji HK, Duman RS. Impairments of neuroplasticity and cellular resilience in severe mood disorders: implications for the development of novel therapeutics. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2001;35:5–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choudary PV, Molnar M, Evans SJ, et al. Altered cortical glutamatergic and GABAergic signal transmission with glial involvement in depression. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2005;102:15653–8. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0507901102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.McCullumsmith RE, Kristiansen LV, Beneyto M, Scarr E, Dean B, Meador-Woodruff JH. Decreased NR1, NR2A, and SAP102 transcript expression in the hippocampus in bipolar disorder. Brain Res. 2007;1127:108–18. doi: 10.1016/j.brainres.2006.09.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Miller TM, Cleveland DW. Medicine. Treating neurodegenerative diseases with antibiotics. Science. 2005;307:361–2. doi: 10.1126/science.1109027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mineur YS, Picciotto MR, Sanacora G. Antidepressant-like effects of ceftriaxone in male C57BL/6J mice. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:250–2. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Rothstein JD, Patel S, Regan MR, et al. Beta-lactam antibiotics offer neuroprotection by increasing glutamate transporter expression. Nature. 2005;433:73–7. doi: 10.1038/nature03180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hassel B, Iversen EG, Gjerstad L, Tauboll E. Up-regulation of hippocampal glutamate transport during chronic treatment with sodium valproate. J Neurochem. 2001;77:1285–92. doi: 10.1046/j.1471-4159.2001.00349.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ueda Y, Willmore LJ. Molecular regulation of glutamate and GABA transporter proteins by valproic acid in rat hippocampus during epileptogenesis. Exp Brain Res. 2000;133:334–9. doi: 10.1007/s002210000443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lee Y, Gaskins D, Anand A, Shekhar A. Glia mechanisms in mood regulation: a novel model of mood disorders. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;191:55–65. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0652-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Uezato A, Meador-Woodruff JH, McCullumsmith RE. Vesicular glutamate transporter mRNA expression in the medial temporal lobe in major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia. Bipolar Disord. 2009;11:711–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1399-5618.2009.00752.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tordera RM, Pei Q, Sharp T. Evidence for increased expression of the vesicular glutamate transporter, VGLUT1, by a course of antidepressant treatment. J Neurochem. 2005;94:875–83. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2005.03192.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tordera RM, Totterdell S, Wojcik SM, et al. Enhanced anxiety, depressive-like behaviour and impaired recognition memory in mice with reduced expression of the vesicular glutamate transporter 1 (VGLUT1). Eur J Neurosci. 2007;25:281–90. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2006.05259.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moutsimilli L, Farley S, Dumas S, El Mestikawy S, Giros B, Tzavara ET. Selective cortical VGLUT1 increase as a marker for antidepressant activity. Neuropharmacology. 2005;49:890–900. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2005.06.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hashimoto R, Hough C, Nakazawa T, Yamamoto T, Chuang DM. Lithium protection against glutamate excitotoxicity in rat cerebral cortical neurons: involvement of NMDA receptor inhibition possibly by decreasing NR2B tyrosine phosphorylation. J Neurochem. 2002;80:589–97. doi: 10.1046/j.0022-3042.2001.00728.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thompson CM, Davis E, Carrigan CN, Cox HD, Bridges RJ, Gerdes JM. Inhibitor of the glutamate vesicular transporter (VGLUT). Curr Med Chem. 2005;12:2041–56. doi: 10.2174/0929867054637635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beneyto M, Kristiansen LV, Oni-Orisan A, McCullumsmith RE, Meador-Woodruff JH. Abnormal glutamate receptor expression in the medial temporal lobe in schizophrenia and mood disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2007;32:1888–902. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Meador-Woodruff JH, Hogg AJ, Jr, Smith RE. Striatal ionotropic glutamate receptor expression in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, and major depressive disorder. Brain Res Bull. 2001;55:631–40. doi: 10.1016/s0361-9230(01)00523-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Devon RS, Anderson S, Teague PW, et al. Identification of polymorphisms within Disrupted in Schizophrenia 1 and Disrupted in Schizophrenia 2, and an investigation of their association with schizophrenia and bipolar affective disorder. Psychiatr Genet. 2001;11:71–8. doi: 10.1097/00041444-200106000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marti SB, Cichon S, Propping P, Nothen M. Metabotropic glutamate receptor 3 (GRM3) gene variation is not associated with schizophrenia or bipolar affective disorder in the German population. Am J Med Genet. 2002;114:46–50. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Chourbaji S, Vogt MA, Fumagalli F, et al. AMPA receptor subunit 1 (GluR-A) knockout mice model the glutamate hypothesis of depression. FASEB J. 2008;22:3129–34. doi: 10.1096/fj.08-106450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Zarate CA, Manji HK. The role of AMPA receptor modulation in the treatment of neuropsychiatric diseases. Exp Neurol. 2008;211:7–10. doi: 10.1016/j.expneurol.2008.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miu P, Jarvie KR, Radhakrishnan V, et al. Novel AMPA receptor potentiators LY392098 and LY404187: effects on recombinant human AMPA receptors in vitro. Neuropharmacology. 2001;40:976–83. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3908(01)00027-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Quiroz JA, Singh J, Gould TD, Denicoff KD, Zarate CA, Manji HK. Emerging experimental therapeutics for bipolar disorder: clues from the molecular pathophysiology. Mol Psychiatry. 2004;9:756–76. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001521. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sanacora G, Zarate CA, Krystal JH, Manji HK. Targeting the glutamatergic system to develop novel, improved therapeutics for mood disorders. Nat Rev Drug Discov. 2008;7:426–37. doi: 10.1038/nrd2462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Black MD. Therapeutic potential of positive AMPA modulators and their relationship to AMPA receptor subunits. A review of preclinical data. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2005;179:154–63. doi: 10.1007/s00213-004-2065-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Lynch G. AMPA receptor modulators as cognitive enhancers. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2004;4:4–11. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2003.09.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.O'Neill MJ, Bleakman D, Zimmerman DM, Nisenbaum ES. AMPA receptor potentiators for the treatment of CNS disorders. Curr Drug Targets CNS Neurol Disord. 2004;3:181–94. doi: 10.2174/1568007043337508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Nowak G, Trullas R, Layer RT, Skolnick P, Paul IA. Adaptive changes in the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor complex after chronic treatment with imipramine and 1-aminocyclopropanecarboxylic acid. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1993;265:1380–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Paul IA, Nowak G, Layer RT, Popik P, Skolnick P. Adaptation of the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor complex following chronic antidepressant treatments. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1994;269:95–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Law AJ, Deakin JF. Asymmetrical reductions of hippocampal NMDAR1 glutamate receptor mRNA in the psychoses. Neuroreport. 2001;12:2971–4. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200109170-00043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Nudmamud-Thanoi S, Reynolds GP. The NR1 subunit of the glutamate/NMDA receptor in the superior temporal cortex in schizophrenia and affective disorders. Neurosci Lett. 2004;372:173–7. doi: 10.1016/j.neulet.2004.09.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Toro C, Deakin JF. NMDA receptor subunit NRI and postsynaptic protein PSD-95 in hippocampus and orbitofrontal cortex in schizophrenia and mood disorder. Schizophr Res. 2005;80:323–30. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Itokawa M, Yamada K, Iwayama-Shigeno Y, Ishitsuka Y, Detera-Wadleigh S, Yoshikawa T. Genetic analysis of a functional GRIN2A promoter (GT)n repeat in bipolar disorder pedigrees in humans. Neurosci Lett. 2003;345:53–6. doi: 10.1016/s0304-3940(03)00501-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Martucci L, Wong AH, De Luca V, et al. N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor NR2B subunit gene GRIN2B in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder: polymorphisms and mRNA levels. Schizophr Res. 2006;84:214–21. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2006.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mundo E, Tharmalingham S, Neves-Pereira M, et al. Evidence that the N-methyl-D-aspartate subunit 1 receptor gene (GRIN1) confers susceptibility to bipolar disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2003;8:241–5. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Maeng S, Zarate CA, Jr, Du J, et al. Cellular mechanisms underlying the antidepressant effects of ketamine: role of alpha-amino-3-hydroxy-5-methylisoxazole-4-propionic acid receptors. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:349–52. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.05.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Moryl E, Danysz W, Quack G. Potential antidepressive properties of amantadine, memantine and bifemelane. Pharmacol Toxicol. 1993;72:394–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0773.1993.tb01351.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Papp M, Moryl E. Antidepressant activity of non-competitive and competitive NMDA receptor antagonists in a chronic mild stress model of depression. Eur J Pharmacol. 1994;263:1–7. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(94)90516-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Trullas R, Skolnick P. Functional antagonists at the NMDA receptor complex exhibit antidepressant actions. Eur J Pharmacol. 1990;185:1–10. doi: 10.1016/0014-2999(90)90204-j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Zarate CA, Jr, Singh JB, Carlson PJ, et al. A randomized trial of an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist in treatment-resistant major depression. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2006;63:856–64. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.63.8.856. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Borza I, Bozo E, Barta-Szalai G, et al. Selective NR1/2B N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor antagonists among indole-2-carboxamides and benzimidazole-2-carboxamides. J Med Chem. 2007;50:901–14. doi: 10.1021/jm060420k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Suetake-Koga S, Shimazaki T, Takamori K, et al. In vitro and antinociceptive profile of HON0001, an orally active NMDA receptor NR2B subunit antagonist. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2006;84:134–41. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2006.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Preskorn SH, Baker B, Kolluri S, Menniti FS, Krams M, Landen JW. An innovative design to establish proof of concept of the antidepressant effects of the NR2B subunit selective N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist, CP-101,606, in patients with treatment-refractory major depressive disorder. J Clin Psychopharmacol. 2008;28:631–7. doi: 10.1097/JCP.0b013e31818a6cea. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Zarate CA, Singh J, Quiroz JA, et al. A double-blind, placebo-controlled study of memantine in the treatment of major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2006;163:153–5. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.163.1.153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zarate CA, Jr, Du J, Quiroz J, et al. Regulation of cellular plasticity cascades in the pathophysiology and treatment of mood disorders: role of the glutamatergic system. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;1003:273–91. doi: 10.1196/annals.1300.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Schiffer HH, Heinemann SF. Association of the human kainate receptor GluR7 gene (GRIK3) with recurrent major depressive disorder. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2007;144B:20–6. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.b.30374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Wilson GM, Flibotte S, Chopra V, Melnyk BL, Honer WG, Holt RA. DNA copy-number analysis in bipolar disorder and schizophrenia reveals aberrations in genes involved in glutamate signaling. Hum Mol Genet. 2006;15:743–9. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddi489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Pickard BS, Malloy MP, Christoforou A, et al. Cytogenetic and genetic evidence supports a role for the kainate-type glutamate receptor gene, GRIK4, in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Mol Psychiatry. 2006;11:847–57. doi: 10.1038/sj.mp.4001867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Laje G, Paddock S, Manji H, et al. Genetic markers of suicidal ideation emerging during citalopram treatment of major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1530–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06122018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Menke A, Lucae S, Kloiber S, et al. Genetic markers within glutamate receptors associated with antidepressant treatment-emergent suicidal ideation. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:917–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08020274. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Paddock S, Laje G, Charney D, et al. Association of GRIK4 with outcome of antidepressant treatment in the STAR*D cohort. Am J Psychiatry. 2007;164:1181–8. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2007.06111790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Shaltiel G, Maeng S, Malkesman O, et al. Evidence for the involvement of the kainate receptor subunit GluR6 (GRIK2) in mediating behavioral displays related to behavioral symptoms of mania. Mol Psychiatry. 2008;13:858–72. doi: 10.1038/mp.2008.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Chaki S, Hirota S, Funakoshi T, et al. Anxiolytic-like and antidepressant-like activities of MCL0129 (1-[(S)-2-(4-fluorophenyl)-2-(4-isopropylpiperadin-1-yl)ethyl]-4-[4-(2-met hoxynaphthalen-1-yl)butyl]piperazine), a novel and potent nonpeptide antagonist of the melanocortin-4 receptor. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2003;304:818–26. doi: 10.1124/jpet.102.044826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cosford ND, Tehrani L, Roppe J, et al. 3-[(2-Methyl-1,3-thiazol-4-yl)ethynyl]-pyridine: a potent and highly selective metabotropic glutamate subtype 5 receptor antagonist with anxiolytic activity. J Med Chem. 2003;46:204–6. doi: 10.1021/jm025570j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Cryan JF, Kelly PH, Neijt HC, Sansig G, Flor PJ, Van Der Putten H. Antidepressant and anxiolytic-like effects in mice lacking the group III metabotropic glutamate receptor mGluR7. Eur J Neurosci. 2003;17:2409–17. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02667.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gasparini F, Bruno V, Battaglia G, et al. (R,S)-4-phosphonophenylglycine, a potent and selective group III metabotropic glutamate receptor agonist, is anticonvulsive and neuroprotective in vivo. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1999;289:1678–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Maiese K, Vincent A, Lin SH, Shaw T. Group I and group III metabotropic glutamate receptor subtypes provide enhanced neuroprotection. J Neurosci Res. 2000;62:257–72. doi: 10.1002/1097-4547(20001015)62:2<257::AID-JNR10>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Palucha A, Tatarczynska E, Branski P, et al. Group III mGlu receptor agonists produce anxiolytic- and antidepressant-like effects after central administration in rats. Neuropharmacology. 2004;46:151–9. doi: 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2003.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Schoepp DD, Wright RA, Levine LR, Gaydos B, Potter WZ. LY354740, an mGlu2/3 receptor agonist as a novel approach to treat anxiety/stress. Stress. 2003;6:189–97. doi: 10.1080/1025389031000146773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Li X, Need AB, Baez M, Witkin JM. Metabotropic glutamate 5 receptor antagonism is associated with antidepressant-like effects in mice. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 2006;319:254–9. doi: 10.1124/jpet.106.103143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Wieronska JM, Szewczyk B, Branski P, Palucha A, Pilc A. Antidepressant-like effect of MPEP, a potent, selective and systemically active mGlu5 receptor antagonist in the olfactory bulbectomized rats. Amino Acids. 2002;23:213–6. doi: 10.1007/s00726-001-0131-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Yoshimizu T, Chaki S. Increased cell proliferation in the adult mouse hippocampus following chronic administration of group II metabotropic glutamate receptor antagonist, MGS0039. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2004;315:493–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.01.073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Yoshimizu T, Shimazaki T, Ito A, Chaki S. An mGluR2/3 antagonist, MGS0039, exerts antidepressant and anxiolytic effects in behavioral models in rats. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2006;186:587–93. doi: 10.1007/s00213-006-0390-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Palucha A, Klak K, Branski P, Van Der Putten H, Flor PJ, Pilc A. Activation of the mGlu7 receptor elicits antidepressant-like effects in mice. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;194:555–62. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0856-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Karolewicz B, Szebeni K, Gilmore T, Maciag D, Stockmeier CA, Ordway GA. Elevated levels of NR2A and PSD-95 in the lateral amygdala in depression. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2009;12:143–53. doi: 10.1017/S1461145708008985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Clinton SM, Meador-Woodruff JH. Abnormalities of the NMDA receptor and associated intracellular molecules in the thalamus in schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2004;29:1353–62. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1300451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Kristiansen LV, Meador-Woodruff JH. Abnormal striatal expression of transcripts encoding NMDA interacting PSD proteins in schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and major depression. Schizophr Res. 2005;78:87–93. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2005.06.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Frizzo ME, Dall'Onder LP, Dalcin KB, Souza DO. Riluzole enhances glutamate uptake in rat astrocyte cultures. Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2004;24:123–8. doi: 10.1023/B:CEMN.0000012717.37839.07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Dagci T, Yilmaz O, Taskiran D, Peker G. Neuroprotective agents: is effective on toxicity in glial cells? Cell Mol Neurobiol. 2007;27:171–7. doi: 10.1007/s10571-006-9082-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Zarate CA, Jr, Payne JL, Quiroz J, et al. An open-label trial of riluzole in patients with treatment-resistant major depression. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:171–4. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.1.171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zarate CA, Jr, Quiroz JA, Singh JB, et al. An open-label trial of the glutamate-modulating agent riluzole in combination with lithium for the treatment of bipolar depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;57:430–2. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2004.11.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Sanacora G, Kendell SF, Levin Y, et al. Preliminary evidence of riluzole efficacy in antidepressant-treated patients with residual depressive symptoms. Biol Psychiatry. 2007;61:822–5. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2006.08.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Coric V, Taskiran S, Pittenger C, et al. Riluzole augmentation in treatment-resistant obsessive-compulsive disorder: an open-label trial. Biol Psychiatry. 2005;58:424–8. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2005.04.043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Mathew SJ, Keegan K, Smith L. Glutamate modulators as novel interventions for mood disorders. Rev Bras Psiquiatr. 2005;27:243–8. doi: 10.1590/s1516-44462005000300016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Banasr M, Duman RS. Glial loss in the prefrontal cortex is sufficient to induce depressive-like behaviors. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;64:863–70. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Lourenco Da Silva A, Hoffmann A, Dietrich MO, Dall'Igna OP, Souza DO, Lara DR. Effect of riluzole on MK-801 and amphetamine-induced hyperlocomotion. Neuropsychobiology. 2003;48:27–30. doi: 10.1159/000071825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Moghaddam B, Adams B, Verma A, Daly D. Activation of glutamatergic neurotransmission by ketamine: a novel step in the pathway from NMDA receptor blockade to dopaminergic and cognitive disruptions associated with the prefrontal cortex. J Neurosci. 1997;17:2921–7. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.17-08-02921.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Zarate CA, Quiroz J, Payne J, Manji HK. Modulators of the glutamatergic system: implications for the development of improved therapeutics in mood disorders. Psychopharmacol Bull. 2002;36:35–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Aguado L, San Antonio A, Perez L, del Valle R, Gomez J. Effects of the NMDA receptor antagonist ketamine on flavor memory: conditioned aversion, latent inhibition, and habituation of neophobia. Behav Neural Biol. 1994;61:271–81. doi: 10.1016/s0163-1047(05)80010-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Garcia LS, Comim CM, Valvassori SS, et al. Acute administration of ketamine induces antidepressant-like effects in the forced swimming test and increases BDNF levels in the rat hippocampus. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2008;32:140–4. doi: 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2007.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mickley GA, Schaldach MA, Snyder KJ, et al. Ketamine blocks a conditioned taste aversion (CTA) in neonatal rats. Physiol Behav. 1998;64:381–90. doi: 10.1016/s0031-9384(98)00097-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Silvestre JS, Nadal R, Pallares M, Ferre N. Acute effects of ketamine in the holeboard, the elevated-plus maze, and the social interaction test in Wistar rats. Depress Anxiety. 1997;5:29–33. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Berman RM, Cappiello A, Anand A, et al. Antidepressant effects of ketamine in depressed patients. Biol Psychiatry. 2000;47:351–4. doi: 10.1016/s0006-3223(99)00230-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Entsuah AR, Huang H, Thase ME. Response and remission rates in different subpopulations with major depressive disorder administered venlafaxine, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, or placebo. J Clin Psychiatry. 2001;62:869–77. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v62n1106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Thase ME, Haight BR, Richard N, et al. Remission rates following antidepressant therapy with bupropion or selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors: a meta-analysis of original data from 7 randomized controlled trials. J Clin Psychiatry. 2005;66:974–81. doi: 10.4088/jcp.v66n0803. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Phelps LE, Brutsche NE, Moral JR, Luckenbaugh DA, Manji HK, Zarate CA. Family history of alcohol dependence and initial antidepressant response to an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:181–4. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.DiazGranados N, Ibrahim I, Brutsche NE, et al. Rapid resolution of suicidal ideation after a single infusion of ketamine in patients with treatment-resistant major depression. J Clin Psychiatry. doi: 10.4088/JCP.09m05327blu. (in press) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.aan het Rot M, Collins KA, Murrough JW, et al. Safety and efficacy of repeated-dose intravenous ketamine for treatment-resistant depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;67:139–45. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.08.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Goforth HW, Holsinger T. Rapid relief of severe major depressive disorder by use of preoperative ketamine and electroconvulsive therapy. J ECT. 2007;23:23–5. doi: 10.1097/01.yct.0000263257.44539.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Kudoh A, Takahira Y, Katagai H, Takazawa T. Small-dose ketamine improves the postoperative state of depressed patients. Anesth Analg. 2002;95:114–8. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200207000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Correll GE, Futter GE. Two case studies of patients with major depressive disorder given low-dose (subanesthetic) ketamine infusions. Pain Med. 2006;7:92–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1526-4637.2006.00101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Liebrenz M, Stohler R, Borgeat A. Repeated intravenous ketamine therapy in a patient with treatment-resistant major depression. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2007:1–4. doi: 10.1080/15622970701420481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Ostroff R, Gonzales M, Sanacora G. Antidepressant effect of ketamine during ECT. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:1385–6. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.7.1385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Perry EB, Jr, Cramer JA, Cho HS, et al. Psychiatric safety of ketamine in psychopharmacology research. Psychopharmacology (Berl) 2007;192:253–60. doi: 10.1007/s00213-007-0706-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Krystal JH, Petrakis IL, Krupitsky E, Schutz C, Trevisan L, D'Souza DC. NMDA receptor antagonism and the ethanol intoxication signal: from alcoholism risk to pharmacotherapy. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2003;1003:176–84. doi: 10.1196/annals.1300.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Petrakis IL, Limoncelli D, Gueorguieva R, et al. Altered NMDA glutamate receptor antagonist response in individuals with a family vulnerability to alcoholism. Am J Psychiatry. 2004;161:1776–82. doi: 10.1176/ajp.161.10.1776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Schumann G, Johann M, Frank J, et al. Systematic analysis of glutamatergic neurotransmission genes in alcohol dependence and adolescent risky drinking behavior. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:826–38. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.7.826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Petrenko AB, Yamakura T, Fujiwara N, Askalany AR, Baba H, Sakimura K. Reduced sensitivity to ketamine and pentobarbital in mice lacking the N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor GluRepsilon1 subunit. Anesth Analg. 2004;99:1136–40. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000131729.54986.30. table of contents. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Boyce-Rustay JM, Holmes A. Genetic inactivation of the NMDA receptor NR2A subunit has anxiolytic- and antidepressant-like effects in mice. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2006;31:2405–14. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Salvadore G, Cornwell BR, Colon-Rosario V, et al. Increased anterior cingulate cortical activity in response to fearful faces: a neurophysiological biomarker that predicts rapid antidepressant response to ketamine. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;65:289–95. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2008.08.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Langguth B, Wiegand R, Kharraz A, et al. Pre-treatment anterior cingulate activity as a predictor of antidepressant response to repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS). Neuro Endocrinol Lett. 2007;28:633–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Mayberg HS, Brannan SK, Mahurin RK, et al. Cingulate function in depression: a potential predictor of treatment response. Neuroreport. 1997;8:1057–61. doi: 10.1097/00001756-199703030-00048. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.McCormick LM, Boles Ponto LL, Pierson RK, Johnson HJ, Magnotta V, Brumm MC. Metabolic correlates of antidepressant and antipsychotic response in patients with psychotic depression undergoing electroconvulsive therapy. J ECT. 2007;23:265–73. doi: 10.1097/yct.0b013e318150d56d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Pizzagalli D, Pascual-Marqui RD, Nitschke JB, et al. Anterior cingulate activity as a predictor of degree of treatment response in major depression: evidence from brain electrical tomography analysis. Am J Psychiatry. 2001;158:405–15. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.158.3.405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Wu J, Buchsbaum MS, Gillin JC, et al. Prediction of antidepressant effects of sleep deprivation by metabolic rates in the ventral anterior cingulate and medial prefrontal cortex. Am J Psychiatry. 1999;156:1149–58. doi: 10.1176/ajp.156.8.1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Machado-Vieira R, Yuan P, Brutsche NE, et al. Brain-derived neurotrophic factor and initial antidepressant response to an N-methyl-D-aspartate antagonist. J Clin Psychiatry. 2009;70:1662–6. doi: 10.4088/JCP.08m04659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]